Sigurd Lewerentz and the Chapel of the Resurrection

Sigurd Lewerentz (1885–1975)

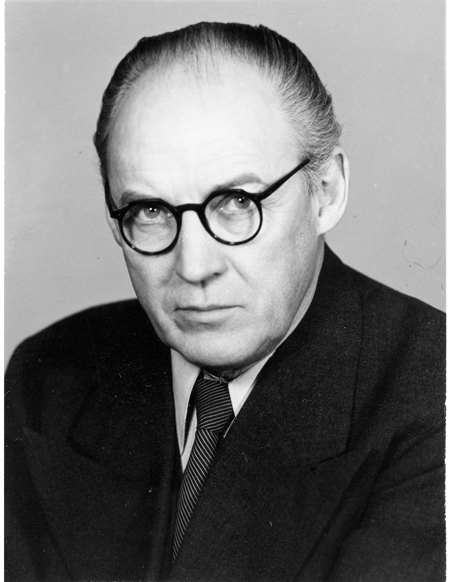

Sigurd Lewerentz is one of the most fascinating architects of the Nordic Classical Movement. Professor Sandy Wilson even goes so far as to suggest that ‘the one original contribution during this century to the classical language of architecture lay in certain austere monuments of the Nordic Classicists; and in that achievement, Lewerentz was an undisputed leader’.1 While supporters of Gunnar Asplund’s (1885–1940) claim for leadership of the movement might disagree on the final point, Lewerentz’s importance and particular contribution to the development of a new Classical architecture, which was rich in Symbolism, cannot be underestimated. Born in the same year, Lewerentz and Asplund worked together regularly throughout most of their careers, and interestingly, both later went on to make very significant contributions to the development of Modern Architecture (Figure 38).

FIGURE 38 Sigurd Lewerentz, Credit – ARKDES.

Born in 1885 in Västernorrland in northern Sweden, Lewerentz’s father was the joint owner of the Sandö Glasbruk glassworks in Kramsfors. As soon as he was old enough, Sigurd worked in the forge after school and at weekends and learned many of the practical arts of manufacturing from the craftsmen there. This early exposure to manual work and purposeful production had a profound influence on him, leading him firstly to study engineering rather than architecture and also to develop a life-long distrust of excessive theoretical speculation. Of all the leading Nordic Classicists, he wrote least, spoke rarely in public and (despite a widely held belief that his output was limited) instead produced a considerable portfolio of completed buildings by the time of his death at the age of ninety.

His education was erratic. After primary school, he attended the Sodra Latin Grammar School in Stockholm but left before taking his baccalaureate. He then enrolled in the Chalmers Institute of Technology where he studied Machine Technology, before changing course to study Civil Engineering in which he graduated in 1908. Throughout the last years of his engineering course, he had been working during his holidays in the Berlin architectural studio of Bruno Moring (1863–1929) to which he returned to work full-time on completion of his engineering degree. He worked for Moring until early1909 when he undertook the now ubiquitous architectural study tour of Italy, which concluded in the summer, when he returned to Stockholm, to finally commence an architectural education at the Royal Academy School. Less than a year later, in 1910, along with Gunnar Asplund, Osvald Almqvist (1884–1950) and three other students, he abandoned his studies once more to help create the new independent Klara Architecture School, engaging Carl Westmann (1866–1936), Ivar Tengbom (Ch 3), Carl Bergsten (1879–1935) and Ragnar Östberg (1866–1945) to teach the young dissidents in the evenings after work. Unfortunately, the Klara School lasted less than a year before closing, at which point, in 1911, a presumably confident young Lewerentz set up his own architectural practice in partnership with Torsten Stubelius (1883–1963).

Within this chaotic education (which included never actually qualifying as an architect) there were two key strands, which stand out. Firstly, his time spent working in Germany was a unique experience amongst the Nordic Classicists and had brought him into contact with a number of specific architectural influences. These included the outstanding nineteenth-century Classical buildings of Carl Freidrich Schinkel (1781–1841), the haunting romantic paintings of Caspar David Freidrich (1774–1840), the new spirit in German Architecture as expressed in the founding of the Deutscher Werkbund2 and in particular the work of one of its leading members, architect Heinrich Tessenow (1876–1950), whose elegantly restrained designs drew both on German vernacular and Classical architecture. Secondly, as with so many of his Nordic contemporaries, his trip to Italy had a profound effect on his architectural development. Fascinatingly, almost nothing is known of Lewerentz’s itinerary beyond a series of black-and-white photographs, which he took and which are now held in the archive of the National Museum of Architecture in Stockholm. Most of the photographs show only a fragment of a Classical building – some rustication, several columns, a window or some paving. It was almost as if the young Lewerentz was immersing himself in the spirit of ancient Classical architecture, rather than ticking off sites and reproducing the standard travelogue of his contemporaries.

Despite his erratic education and quiet nature, the partnership with the more outgoing Stubelius worked well, and the new practice won work and prospered. An initial fare of domestic projects including renovations, alterations and extensions was soon followed by workers housing, private villas and a new boathouse for the city rowing club in Stockholm of 1912. This is an important little building (situated just a few hundred yards upstream from where the Stockholm Exhibition would later be held in 1930) as it had a freshness and clarity of expression, which was more typical of his later Functionalist work than his early Classicism. Boarded in vertical timber, its framed structure is clearly expressed by continuous glazing at first-floor level with the staircase between its two levels drawn out as a dramatic diagonal on the riverside elevation. The villas from this period included the brick Villa Gustav M Ericsson of 1912 in Lidingö, east of Stockholm; the wooden Villa Ahxner in Djursholm of 1914; and the white rendered Villa Ramen in Helsingborg of 1914–1915.

As with every other contemporary architectural start-up, Lewerentz and Stubelius also entered numerous competitions for public buildings. These included unsuccessful entries for a primary school in Kalmar, of 1913, and the competition for an art gallery in the Djurgarden (Liljevalchs Konsthall), also of 1913, which was won by Carl Bergsten with an early Classical design. In 1914, Lewerentz and Stubelius won the competition for a new crematorium at Bergaliden in Helsingborg. Although never built, the architecture and its intense symbolism were to prove highly influential. ‘Lewerentz’s project for Bergaliden Crematorium in Helsingborg – a long, narrow, lightly coloured volume, forming a bridge over a stream, which disappeared under the building as the River Styx and emerged to fall over a cascade as the Waters of Life – suggested the means towards a new architecture that combined formal restraint with emotional resonance.’3

Crucially for Lewerentz, the model of his proposal was displayed at the Exhibition of the Baltic Nations in Malmo in 1914, where it was seen by Gunnar Asplund, Lewerentz’s former fellow student. By 1914, Asplund had also started his own practice and was establishing a growing reputation for quality of his work. The two were reacquainted and discussed jointly entering the recently announced competition for a new Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm. Lewerentz maintained his partnership with Stubelius throughout this period and, with his agreement, entered the Stockholm Cemetery competition with Asplund in 1915. Little did they know that their decision to jointly enter the cemetery competition would establish the most creative partnership of the Nordic Classical Movement, which would last throughout the next twenty years.

The site chosen for the new Woodland Cemetery was some 6 km south of the city centre, then just beyond the built-up area and conveniently near the existing cemetery of Sandsborgskyrkogården. The 50-hectare site was to the south of the existing cemetery and was almost entirely wooded with one small hill and two small gravel pits. Lewerentz and Asplund’s design, which they named ‘Tallum’ (the pine tree), was placed first amongst the fifty-three entries received (by a jury which included their former teacher Ragnar Östberg). For Lewerentz and Asplund, ‘Tallum’ symbolized a society poised between tradition and modernity, wishing to embrace the new world while maintaining its spiritual links to ancient traditions.4

Asplund and Lewerentz’s competition entry … clearly stands out in its intense romantic naturalism. The winning scheme was the only one that turned the existing, essentially untouched Nordic forest on the site into the dominant experience. While civilised and well-groomed English parks mixed with allées on axis, and informal and formal open areas were features typical of the other competitors, Asplund and Lewerentz evoked a much more primitive imagery. It is the evocation of raw Nordic wilderness that constitutes a radical departure in landscape architecture, not to speak of cemetery layout at this time. Asplund and Lewerentz’s sources were not high architecture or landscape planning, but rather mediaeval and ancient Nordic vernacular burial archetypes. Freely mixed in were elements from the Mediterranean and antiquity whose effects are again heightened by becoming isolated elements in the Nordic forest.5

While Lewerentz continued to develop the main cemetery entrance and the routes through and around the site, in 1918, the board asked the architects to design a small chapel which was to be built quickly (and relatively cheaply) in advance of the main chapel in a particularly densely wooded area where it would not detract from the main chapel on its later completion. Thus, Asplund’s celebrated Woodland Chapel was conceived, created and finally consecrated together with the cemetery in 1920 (Ch 12).

A few months after the consecration of the Woodland chapel, the board commissioned Lewerentz to design another small funeral chapel, which would become the Resurrection Chapel. Following much discussion with the Cemetery Board and further revision and development of Lewerentz’s original ideas, his design proceeded to construction and completion, becoming one of the key buildings of Nordic Classicism (the design is dealt with in detail below).

As the years passed, the very different characters of these partners became both more pronounced and more apparent to the cemetery board. While Asplund could be accommodating (or certainly more socially skilful in handling the board), Lewerentz was increasingly perceived as difficult. Work continued on the development of the overall site and in particular on the setting for the main chapel, the development of the Meditation Grove, the Via Sacra and the giant cross which was to dominate this new open landscape. Lewerentz was constantly at the heart of this effort, and while both architects worked closely on the development of the site, it is Lewerentz who deserves the major credit for this masterpiece of landscape architecture. In 1935, although both men had been working on the design of the main chapel together until that point, Asplund was appointed alone to finally execute the design (which was completed shortly before his death in 1940), and Lewerentz was dismissed by the cemetery board, thus ending their extraordinarily creative partnership.

While working on the Stockholm Cemetery design with Asplund, back in 1916, Lewerentz and Stubelius had entered and won the competition for a new Eastern Cemetery in Malmo. Like Stockholm, the development of this cemetery was to span much of the remainder of Lewerentz’s career, and like Stockholm, ‘the constant of the whole project was the need to create spaces where people could undergo a difficult experience, the ritual of separation from a loved one’.6 Here, Lewerentz organized the layout around a long ridge which divided the site, locating the chapels at either end, and having taken this natural feature as his main axis, the remainder of the cemetery is laid out parallel to it. The buildings of this competition entry are still Classical, albeit in ever-increasing simplicity. Lewerentz was beginning to use purer and purer forms – the most striking being the three truncated cones of the crematoria in the centre of the ridge.

As with Stockholm, his competition plan and the design of the chapels and crematoria went through considerable development, initially as he worked with the cemetery board and increasingly when he abandoned the Classical language which he had so mastered and moved, apparently almost overnight, to the new Functionalism. While in many ways, this transition can be seen in the increasing simplicity and restraint of his work during the 1920s, it was brought to a conclusion through his work with Asplund and others on the Stockholm Exhibition of 1930. The result was a manifesto for Scandinavian Modern architecture – an irresistible vision of a bright, new, modern, egalitarian future for this new generation of architects and their peers. Unlike other architects, such as Sirén or Tengbom, for Lewerentz, his conversion was total and there would be no further hint of Classicism in his future work.

His work at Malmo Cemetery became a history of his career – from the quiet dignity of his severely Classical colonnaded funerary chapel and waiting room completed in 1926, via the pure white forms of Functionalism in his crematorium completed in 1936, to the brick brutalism of the chapels of St Gertrud, St Knut and the Chapel of Hope completed in 1955 and so on until his final building, a flower kiosk of 1969 in rough board-marked concrete. Neither the buildings nor the landscape (which lacked the advantage of the mature woods of Stockholm) fail to maintain the extraordinarily high standards of the Woodland Cemetery.

Shortly after work commenced on the cemetery in Malmo in 1928, Lewerentz entered and won the competition for a new theatre in the city. This was in a similar style to his early work at the cemetery with a symmetrical, Classical plan of auditorium and foyer on axis within a severely restrained composition in which the only external Classical decoration was confined to a Doric entrance portico. The design did not proceed to construction, and a further competition was held in 1933, which Lewerentz also won.

By now, Lewerentz’s entry was stripped of all decoration, and the key internal spaces found external expression in four simple volumes (much in the manner of Le Corbusier’s Palace of the Soviets of 1931) with the main elevation to the foyer and square beyond a simple, expressed, glazed concrete frame (which precedes Asplund’s Woodland Crematorium (1935–1940) by several years). Despite his clear win, Lewerentz was commissioned along with the second-placed entrants Erik Lallerstedt (1864–1955) and David Helldén (1905–1990) to develop a joint design, which was finally constructed with completion achieved in 1944. As built, this is an essay in early Functionalism: the foyer – a white box in which black marble stairs climb to the first floor is cold and rather bleak, but the auditorium is more successful. Here, the symmetrical semicircular auditorium from Lewerentz’s first competition entry survives, now raking below a warm, finely crafted, maple-clad ceiling.

The other major works from this period are Lewerentz’s design of 1930 for a Social Security Administration building in Central Stockholm and his Villa Edstrand in Falsterbo of 1933–1937. His administration building is symmetrical on plan with entry and courtyard on axis. Stripped of all decoration to become a rather grim eight-storey rendered block, into which is carved a semicircular courtyard, it is symmetrical on plan with both courtyard and main entrance on axis. (Comparisons with Ivar Tengbom’s contemporary Tändstickspalatset (Ch 3) are interesting with similarities in layout, but Lewerentz’s austere functionalism for the state bureaucracy contrasts dramatically with Tengbom’s sumptuous Classicism for Ivar Kreuger – ‘The Match King’.)

The Villa Edstrand is altogether more interesting and represents Lewerentz’s struggle with the new language of Functionalism. Situated in a small coastal town on the southern coast of Sweden, this holiday home opens up to the sea and celebrates sunshine and summer living. An elongated, two-storey brick block is almost entirely eroded by balconies and terraces, which provide almost all the internal spaces with views of the sea beyond. The ground floor is almost entirely glazed, and the building’s steel frame is exposed in numerous places to support steel and glass canopies, a steel pergola, balustrades and a flagpole. An internal staircase between the first-floor accommodation and the roof terrace is particularly advanced for this period, constructed of bent sheet steel supported on rods from above. The overall effect is of a nautical practicality, which avoids the then fashionable clichés of porthole windows, white-painted metalwork and elliptical wooden handrails.

By the end of the 1930s, disillusioned by his dismissal from the Woodland Cemetery and frustrated by his treatment on the Malmo Theatre project, Lewerentz changed direction once more and completely abandoned his architectural practice. Having used his engineering skills for many years in the design of metal doors and windows on his projects, in 1940, he set up his own factory to produce them, which he ran successfully until 1956 when his son took over the day-to-day management of the business. During this period, he had occasionally undertaken minor architectural commissions, and in 1955, at the age of seventy, he entered and won the architectural competition for the new St Mark’s Church in Stockholm. And so his extraordinary story continued with this church and another – St Peter’s at Klippan, designed in 1963, becoming acknowledged internationally as two of the most important examples of Modern sacred architecture. While the quality of the internal and external spaces, which the now elderly Lewerentz had created, was amongst his best work, it was his new ‘Brutalist’ style of the detailing which took his architecture off in yet another entirely original direction.7

At first sight, these churches appear to have nothing in common with his earlier Classical work. Raw primitive brickwork – rough, twisted and often over-burned bricks (which were never cut), created from earth, fire and water – became an elemental material in Lewerentz’s hands – heavy brick walls; brick floors which swell and slope; brick vaulted ceilings, supported by rusted steel columns and beams of standard sections; glass attached with metal clips to the outside of window openings. On one level, this was the act of building, reduced to its most basic components, and on another, this was an architecture, like the earlier Resurrection Chapel, of extraordinary subtlety. Lewerentz included a small pool by the baptismal font where water drips constantly as both a symbol of the River Jordan and to provide a constant echo around the space. Side chapels are lit only by candles and the rough brickwork has mortar joints simply wiped with sackcloth. It is crude and yet also, directly connected with ancient, humble buildings and the timeless act of worship.

Despite appearances, there remained an essential, underlying consistency to these churches and the rest of his work – the importance of route and ritual, the relationship between external and internal spaces, natural light used sparingly to focus attention, every detail considered and crafted to become something timeless in his hands and most importantly of all, a profound understanding of life and the human spirit, which was reflected in all his best work.

Lewerentz was nearly eighty when St Peters was completed and nearing the end of his remarkable career. Of all the architects who moved from Classicism to Modernism in the early 1930s, perhaps it was Lewerentz who had most to lose. As Colin St John Wilson asked of his conversion from Classicism, ‘how then, could such a master come utterly to reject that language, and then go on to make equally powerful and equally mysterious buildings out of that rejection’?8 It was an extraordinary achievement.

Throughout his life, Lewerentz was a man of few words; even in the first half of the twentieth century, it was unusual for an architect to have no publications and to give no lectures, treatises or explanations of his buildings. For him, his medium was architecture, and he trusted that the care and thought which he invested in his buildings allowed him to communicate his view of life more effectively than through any other medium; he truly was a master of sacred architecture, who continues to speak to us through his work.

The Chapel of the Resurrection (1921–1925)

Up until 1921, Lewerentz’s work on the Woodland Cemetery had been focused on the overall organization of the site, including the development of the key routes and external spaces and in particular the massive entrance exedra and entrance driveway. As noted above, Asplund had created a small funeral chapel, known as the Woodland Chapel, whose completion allowed the consecration and opening of the cemetery in 1920.

A few months after opening the cemetery, the cemetery board commissioned Lewerentz to design another small chapel, known then as the South Chapel, which would become the Resurrection Chapel on its consecration. His initial brief was for a modest wooden structure, which was to be slightly larger than Asplund’s Woodland Chapel, holding up to 100 mourners, and his early sketches showed both a square and circular building. This was quite quickly developed into a rather grander and more permanent chapel which would be approached through the trees from the south by the Way of the Seven Wells with a Classical portico on axis, leading into the building, which lay directly behind the portico on a north/south axis (much in the style of Asplund’s first, rejected, design for his Little Chapel of 1918). Within, there was to be no altar but a simple, central catafalque upon which the coffin would rest, and around which, the mourners would gather.

Neither the orientation nor simplicity of the interior proved acceptable to the cemetery board. After much debate and discussion, it was agreed that, in accordance with Christian tradition and as with the completed Woodland Chapel, it should be reoriented east/west and that an altar with cross should be incorporated. Lewerentz must have fought this change in orientation hard as it meant that the chapel, instead of being the natural conclusion of the 888-m-long north/south axial avenue of the Seven Wells, would now have to be at 90o to this dramatic approach. From his drawings, it is clear that he developed a number of potential solutions before finally deciding to detach the entrance portico from the chapel and use it to address the north/south axis as originally intended but then to link it at almost 90o to an entrance at the rear of the chapel which was spun onto the east/west axis demanded by the cemetery board. Once this crucial decision was taken in 1922, he began to develop the design more fully.

FIGURE 39 Chapel of the Resurrection Plan, Credit – John Stewart. 1. Entrance Portico 2. Chapel

The sequence that forms the approach to the chapel starts at what is now the Grove of Remembrance, a paved square on a mound surrounded by elm trees. From this vantage point, the Way of the Seven Wells runs due south through the trees as a thin shaft of light parting the blackness of the forest. The path is lined with weeping birches, then ordinary birches, followed by pines and finally spruces making the route increasingly dark, as one moves north along it. Gradually, a white glimmer appears at the end of the path, and as it comes into focus, we find it is a tall Classical white limestone portico, standing out starkly in the midst of this dark Nordic wood (Figure 41). As we finally enter a simple low-walled courtyard in front of the portico, the forest releases us from its grip, but even now the columns and doorway beyond are facing due north and remain in deep shadow. Beyond the portico, we see a simple rendered building and a vast bronze doorway, through which to enter. Here we can pause, congregate and wait by the Seventh Well before entering.

FIGURE 40 Chapel of the Resurrection Section, Credit – John Stewart.

FIGURE 41 Chapel of the Resurrection Entrance Portico, Credit – John Stewart.

As we move under the portico towards the doorway, we notice for the first time a sliver of light between the portico and chapel building and realize that the chapel and portico are thus at a slight angle to each other and completely detached. The strangeness of this unusual arrangement grabs our attention and makes the portico itself now appear like some ancient Classical fragment (such as the one Lewerentz had photographed in Italy) – lost and then rediscovered, deep in the forest – adjacent to which, a plain, new, simple, rendered basilica has been erected. The contrast between the richly carved and detailed stone Corinthian portico and the plain rendered surface of the chapel itself is extreme – both heightening the emotional charge and further engaging the visitor. These contrasts, which continue within the building, evoke its ritual and purpose – a highly significant event for those involved and yet a common end for all of us; a connection with another world, yet rooted in this one; a simple rustic box, contrasting with the Classical language of the Gods.

We cross the gap into the rendered building of the chapel itself. The interior continues the theme of light within darkness, and as we move forward and turn to face the altar, we see the only window high on the south wall, directing sunlight into the centre of the space, where the coffin lies on a simple catafalque. This great south-facing window (made possible by the reorientation of the chapel) is hugely important; it provides the only view of the sky (and what lies above); it is the only source of natural light for the chapel and, being south-facing, provides both ever-changing, life-enhancing, contemplative sunlight; it lights the coffin of the deceased and provides a further focus for the ceremony; it creates deep shadows elsewhere in the space which are deeply evocative; and finally, it provides dramatic side lighting to the other focus of the space – the altar – picking out the richly carved Corinthian stone baldachino and the contrasting, simple wooden cross within it. The baldachino itself is elongated – tall and stiff and with a finality about it – though not the end of the route for the mourners; it oversees the final worldly destination of their loved one (Figure 42).

FIGURE 42 Chapel of the Resurrection Interior, Credit – Addison Godel.

Within the chapel, the strangeness and air of unreality established outside continues. This is a space which is designed to disturb – to feel as if it exists between two worlds. Mannerist tricks are deployed in dressing this plain box but are so restrained as to suggest that all decoration is simply vanity in the face of death. The pilasters around the walls protrude only an inch or so, creating the most subtle of shadows; the acanthus leaf brackets, which support the great south window surround, are massively overscaled to emphasize the window’s symbolic importance, and just as we saw daylight between the roof of the portico and the eaves of the chapel, so too the roof of the chapel itself is disengaged and appears to hover above its surrounding supporting walls. The seating, rather than being in fixed pews, is simply a few dozen wooden chairs, which are arranged facing the altar but which also continue to the left of the coffin both to balance the presence of the south window and to allow the immediate family a view of the sky above and beyond, reminding them of both a world above and a world outside to which they will return after the ceremony. It is a celebration of life and death – the everyday and the particular, the worldly and the other-worldly.

The exit door in the west gable wall of the chapel we passed without noticing, on our right on entering the great south window and the coffin on our left distracting us. It is domestic in scale, understated and completely unadorned either internally or externally; it is part of the normal world outside to which we return after the difficult moment of parting (Figure 43).

FIGURE 43 Chapel of the Resurrection West Elevation, Credit – John Stewart.

Down a simple flight of steps to a grassed sunken court, surrounded by trees and enclosed by the simple colonnade of the mortuary – a simple forest space to say farewell to fellow mourners – the journey is over. These external spaces, which Lewerentz so subtly created, are just as important as the principal space of the chapel itself. From the darkness of the forest and the north-facing entrance courtyard, via the chapel and its great south-facing window, to this sunlit forest court, we have passed through grief, parting and on to hope.

What were Lewerentz’s sources? Classical fragments and memories from Italy; traditional Swedish manor houses; the simplicity of Asplund’s Woodland Chapel; Tessenow; CF Hansen’s Vor Frue Kirke with its dressed stone portico and rendered body – all assimilated, in a subtle and masterful composition. There is a timelessness and yet a freshness here, a binding together of landscape and building, a subtlety and yet a powerful evocation of emotion and ritual delivered at a level which few architects of sacred buildings ever achieve.

Having thus so brilliantly mastered the Classical language (an achievement largely denied to most contemporary Classicists), it seems even more extraordinary, not only that he should abandon this style entirely and forever just a few years later but also that he should go on to design a number of brutally modern churches, which are themselves now regarded as amongst the greatest of the Modern Movement. To quote Colin St John Wilson once more: – ‘His classicism was more refined, more deeply felt, more original than that of any of his contemporaries; his late work was more austere than any minimalist, more uncompromising than any brutalist.’9 What spanned both these phases of his career was his sensitivity and ability to understand the human condition, focus his work on the fundamental purpose of the building, celebrate it, reinforce it, clarify and communicate it, and by so doing, increase the emotional impact of the spaces and the importance of the rituals which take place within them. A rare talent indeed!