Oiva Kallio and the Villa Oivala

Oiva Kallio (1884–1964)

Oiva Sakari Kallio, to give him his full name, was one of the leading Finnish architects of the 1920s who, despite a number of grand city planning projects, is now best remembered for his own modest summer villa on the island of Villinki near Helsinki.

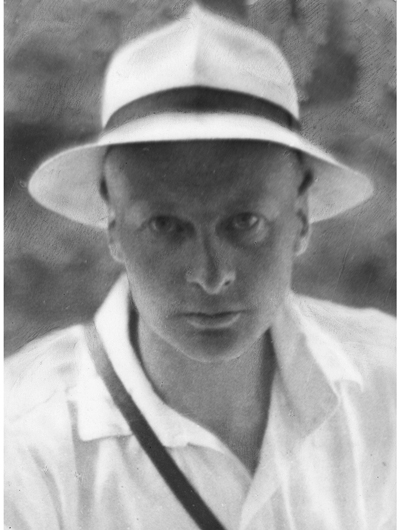

Oiva was born in 1884 in Esse in Western Finland, where his father was the county provost. He was brought up in relative comfort and, like many of his architectural contemporaries, showed great artistic promise with many of his childhood sketches and paintings having survived to this day (Figure 44). His secondary education was at the Vassa Finnish Real Lyceum from which he graduated in 1904 before entering what was then the Helsinki Technical Institute, graduating in architecture in 1908. While not an outstanding student, he was regarded as a fine draughtsman by his tutors and he showed an early interest in domestic architecture while still a student, including his entry for the Kulosaaren Villa competition of 1907 in which he finished fifth.1

FIGURE 44 Oiva Kallio, Credit – Museum of Finnish Architecture.

As we have already observed, graduation from a Nordic School of Architecture at this time generally led to a study tour for the more affluent students, who in most cases focused on Italy and its Classical architecture. Unusually, therefore, young Oiva’s post-graduation peregrination covered only Northern Europe, where he visited Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Austria and Hungary. While he would undoubtedly have taken in many of the most recently completed contemporary buildings on his travels, his one remaining sketch book suggests that he was at least as interested in the conventional, sights, cityscapes and buildings as any tourist of the time, as evidenced by his finely drawn views of Salzburg and Munich and their numerous baroque church interiors.

On his return to Helsinki, he started working for his elder architect brother, Kauno Sankari Kallio (1877–1966), who had already founded his own practice and recently won the competition for the new Tampere Civic Theatre, which was then under construction. On its completion in 1913, the theatre was an important early example of the continuing thread of Classicism in Scandinavia. Like Hack Kampmann’s Aarhus Theatre of 1900, the elder Kallio’s design provided a first-floor foyer behind a Doric portico complete with Classical pediment. In contrast to Hackman’s richly decorated facade, however, Kallio’s building was extremely restrained with plain, painted rendered columns within a rendered facade. This simplification was partly as a result of Kaunio not enjoying Kampmann’s extraordinary budget, but also represented the more Spartan spirit of Finland.2

In 1911, the brothers won the competition for a new church at Karkku, which proceeded directly to detailed design and construction, being completed in 1913. Somewhat surprisingly, after the pared-down Classicism of the Tampere Theatre, this was an essay in mainstream National Romanticism, dominated by a boulder-stone bell tower with a great clay-tiled roof, drooping low over the rough-hewn granite walls. It is interesting to speculate whether this apparent change in direction was evidence of Oiva’s influence and interest in Scandinavian vernacular architecture, or alternately, and more likely, represented an emerging view amongst some young architects of the period – that Classicism was appropriate for civic buildings while traditional Nordic for rural churches. This allocation of styles to differing building types and contexts was hardly a new phenomenon with many eclectic European architects of the nineteenth century believing that Classical architecture was appropriate for public buildings while only Gothic was untainted by pagan worship and thus suitable for Christian religious buildings.3

Before construction was completed in 1912, Oiva established his own independent practice and also a new working relationship with his elder brother, which saw them continuing to collaborate on Karkku Church until its completion, as well as later jointly entering competitions and sharing their workloads for a number of years. Oiva’s interest in domestic architecture continued, and he had his first competition success in 1913, albeit for the design of a model summer house sponsored by the Home Arts Magazine. His winning entry remained rooted in the Nordic vernacular and was heavily influenced by Carl Larsen’s visions of a rural idyll, complete with weathervanes, shutters, a water butt and even a dog kennel by the front door. Further real commissions, however, soon followed this early success, including the Gröndahlin and Durchmann Villas of 1915 and the Allinnassa and Gestrinin Villas in 1918, but further competition success eluded him until 1920 when he and his brother jointly won two competitions, for a new head office for the SOK Cooperative in Central Helsinki (1918–1921) and for a new hydroelectric power plant in Imatra (1918–1923).

The Classical design of the SOK head office in Helsinki (now the Radisson Blue Plaza Hotel) represented a return to Classicism for the brothers, whether inspired by its city-centre location or perhaps by the emergence of Nordic Classicism in Sweden and Denmark. Completed in 1921, its heavily rusticated granite base supports three floors of rendered offices below a vast, pitched tiled roof. Its most dramatic feature is the corner tower complete with granite quoins and pedimented balcony below a colonnaded attic. The interiors are simple and elegant – particularly the entrance hall with its Doric columns and heavily coffered ceiling and the top-lit main reception area.

The Imatra Power Plant is a further essay in Classicism – although this time more restrained, not least in response to the requirements of the building. Here a vast red brick turbine hall spans the river above an arched grey granite base with the double-storey high windows of the turbine hall, creating a giant Classical order. The entire complex took five years to design and construct, keeping both the brothers’ offices busy throughout the early 1920s.

In 1921, following an unsuccessful Classical entry in the competition for Iisalmi City Hall, Oiva alone won the competition for the new Aurejärvi Church (1921–1924). For an architect who appeared to be actively contributing to the development of the new Classical architecture, this appeared to be a further strangely backward step. Here we have a traditional, rural wooden Scandinavian church with a steeply pitched shingle roof above boarded timber walls. The churchyard gateway in boulder stones and tiles is once more medieval in spirit, and though the bell tower is detached – campanile style – its treatment of wooden spire over shingle-clad columns looks back more to the great Norse myths rather than forward to a European Classical future. The year 1923 brought further competition success with Oiva winning the competition for a new Civil Guard building in Varkaus in Central Finland, which was completed in 1926 and which is still in use today by the municipal council. Its white rendered walls, below a terracotta tiled roof complete with bell tower, still make a striking combination against its dense forest backdrop.

This constant oscillation between Finnish vernacular and Nordic Classicism strongly suggests that both Oiva and his brother believed it appropriate to change architectural style depending on the nature of the site and their brief, with rural locations and traditional building types such as churches, being executed in the vernacular and urban locations and contemporary building types such as power stations, being designed in the new Classical style. This approach was not unusual amongst their contemporaries, albeit in contrast to the leaders of Nordic Classicism such as Asplund and Tengbom, who by the mid-1920s were employing their new architectural style consistently in all contexts and to all building types.

At the end of 1924, Oiva finally embarked upon his pilgrimage to Italy, but unlike his earlier student contemporaries, he was now able to drive himself in his new Renault via the Netherlands and France. On his return to Finland (or perhaps during his Roman holiday), Oiva began planning a project of his own – a new summer house for his family on the beautiful wooded island of Villinki, East of Helsinki. Here, for the first time, he successfully brought together his interest in traditional Finnish building with his reinvigorated passion for Classical architecture within a single building. Architecturally, this synthesis of Ostrobothnian farmhouse and Roman villa is an entirely successful, subtle and sophisticated design and the one for which Oiva is best known today. (It is dealt with in detail below.)

The year 1925 brought Oiva his major professional breakthrough (as well as many years of work) when his competition entry for a new city plan for Central Helsinki was awarded first prize. His entry combined an effective solution to the planning of the city centre with a seductive vision of a new, civilized, orderly urban lifestyle. The plan proposed that the new (Republican) Parliament Building, for which JS Sirén had just won the competition, should act both as a termination of Mannerheimintie and as a counterpoint to the existing (Imperial) Senate Square. Linking both primary spaces and extending outwards would be new, elegant, tree-lined boulevards with fountains and columns marking intersecting axes, reflecting pools contained by blocks of apartments, over arcades of shops and offices at street level. The influence of Camillo Sitte and his theories of urban design is clear once more, as is that of the very real French and Italian cities with their long arcades and city squares, which Oiva had so recently visited.4 It was a traditional European vision of urban living, dominated by public and private pedestrian space, which would, all too soon, be supplanted by traffic management and functional zoning.

While his city plan was being developed, the practice continued to undertake new commissions, and in 1926, his Classical design for a new bank in Jyväskylä was accepted. Compared to the heavily rusticated stonework of the SOK building of five years earlier, the restrained rendered facade, crisp string courses between floors and simple architraves to the windows, below a coffered cornice, show both Oiva and Nordic Classicism’s continuing development into a lighter, more elegant language with the double-height doorway complete with Classical frieze – a knowing reference to Asplund’s Stockholm City Library, which was by then nearing completion in Stockholm from where the Movement continued to be led.

Oiva’s design for an Old Peoples Home in Kuopio of 1926, which was completed a year later, shows his continuing development and now apparent consistent commitment to Classicism. This is a modest free-standing building in the centre of the town – perhaps the scale at which Oiva produced his best work. Once again we have the now familiar, plain rendered facades above a granite base course, but on this occasion, with a subtle entry sequence of covered entrance gateway through a boundary wall, leading to an external entry court from which external colonnaded stairs lead to a first-floor entrance. It is a crisp, elegant building whose external entrance courtyard and asymmetrical main facade lift it far above the average of the period.

By 1927, Oiva’s dream of creating Helsinki as a new Classical city was struggling against both local vested interests and the legitimate need to deal with the ever-increasing, city-centre traffic congestion. In response, his original proposals were transformed into a completely new vision (drawn by his assistant Elsi Borg (1893–1958))5 of a Nordic Manhattan with his series of elegant public streets and spaces, replaced by four lanes of cars thundering through canyons of six-storey blocks of accommodation under soaring biplanes. Oiva continued to develop his ideas in conjunction with the city’s town planning department, producing one final proposal in 1932, but sadly (as with Eliel Saarinen (1873–1950) before him and Alvar Aalto (Ch 9) many years later) none of his plans were ever implemented. Despite this huge frustration, his competition win and work on the city plan had successfully raised his professional profile, and he was elected Chairman of the Finnish Association of Architects in1927 and Chairman of the State Architectural Board in 1929.

The dramatic transformation of his plan for Helsinki most clearly expressed his growing doubt about Classicism’s continuing ability to respond to the demands of the fast-changing world, which he witnessed around him, as well as his growing interest in Functionalism. Along with a number of other young Finnish architects, including Alvar Aalto (Ch 9), Erik Brygmann (1891–1955), Pauli Ernesti Blomstedt (1900–1935) and Hilding Ekelund (1893–1984), Oiva had followed the development of the new Rational architecture and seen the completion and publication of the first modern buildings in Germany and France. Having won the competition to design offices for the Pohja Insurance Company in Central Helsinki in 1928, he produced the first Functional building in Helsinki, complete with metal ribbon windows under a flat roof. It opened in 1930, to the bewilderment of the city’s residents and the critical acclaim of his architectural contemporaries. At ground-floor level, continuous double-height glazed shop windows dissolved the barrier between the interiors and the street – above – continuous bands of glazing lit each floor with no apparent structural support and at roof level – a roof garden replaced the traditional, tiled, sloping roof. The interiors were, if anything, even more dramatic with the top-lit banking hall being an impressive early example of the new stripped-down Functional design without a hint of either decoration or any superfluous detail. Oiva designed all the steel and leather furniture for use throughout the building (including a foot stool ‘Pohja’ which is still in production today). With the opening of the Pohja building in 1930, Oiva, briefly, led the development of Functionalism (or Funkis, as it was known) in Finland along with Alvar Aalto.

For many Scandinavian architects such as Asplund, Aalto and Lewerentz, this move from Classicism to Functionalism was absolute and irrevocable, but for a number of others, including Sirén, Tengbom and the Kallio brothers, there remained a lingering interest in and affinity with Classicism, with symmetrical plans, Classical details and the use of pure geometric forms continuing to crop up from time to time in their designs of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Unfortunately, this combination of Functionalist styling with lingering Classicism was rarely successful (with perhaps the notable exception of JS Sirén, who remained at heart a Classicist), and it was the group of Nordic architects, who abandoned Classicism totally and embraced the radically different approach to design which was at the heart of Modernism, who went on to successfully develop Functionalism into the more humane, technologically advanced and sophisticated Modern architecture for which Scandinavia is now well known.6

Kallio’s early contribution to Functionalism was therefore followed by a number of buildings in the 1930s, which sought to combine his new Functionalist styling with either symmetrical Classical planning or occasionally Classical elements or decoration. Unfortunately, his success in bringing Ancient Rome to a Nordic forest in his Villa Oivala was to allude him in his attempts to combine Functionalism and Classicism throughout the remainder of his career.

An early effort was the Pohjanmaan Museum in Oulu of 1931. This new library and museum building is a simple, symmetrical rendered block with three horizontal bands of completely unadorned windows, which is entered, on axis, via a pink granite Egyptian-style doorway (from Bindesbøll via Asplund). Whether this was a genuine attempt by Oiva to combine the styles or simply the response of a newly converted Functionalist architect to a more conservative client is uncertain, but this and his further essays in this idiom were to contribute little further to either the development of Scandinavian architecture or the quality of his own portfolio.

Despite this apparent stylistic confusion, his practice continued successfully until the 1950s, completing a number of apartment buildings in and around Helsinki as well as several branches of the Nordic Union Bank throughout Finland. Professionally, he continued to play a leading role in the Finnish Association of Architects and acted as a judge in a number of architectural competitions throughout this period. His final completed building was a new dormitory for lecturers at the Helsinki School of Economics – Topeliuksenkatu. Completed in 1952 when Kallio was sixty-eight, this modern, eight-storey block of apartments with recessed balconies would go unnoticed today.

Oiva Kallio died in 1964 at the age of eighty, leaving behind him a significant body of work amongst which shines most brightly, his own rustic yet subtle, cleverly resolved Villa Oivala. Since its completion in 1924, it has become hugely influential, both as one of the finest examples of Nordic Classicism and as a prototype of relaxed outdoor Nordic living. The black-and-white image of the courtyard from the 1920s –, draped in climbing plants, with hanging paper lantern, bird table, bench and the view to the chairs around the table overlooking the sea – has inspired numerous summer houses, offered a new twentieth-century domestic model and created an image of Scandinavian life, which is as powerful today as it was 100 years ago.

Villa Oivala – 1924

In 1924, Oiva and his wife returned in their car from their road trip to Italy. Inspired by the Roman villas which they had seen in Pompeii and Herculaneum, Oiva started work on an atrium villa of his own. He had purchased several acres of land on the island of Villinki, off Helsinki, where thick pinewoods ran down to a rocky shore. The site he chose for his villa was on the edge of the trees with views out to sea and access directly from the forest. Here he located his own peristyle atrium villa – 13.85 × 13.85 in plan with a courtyard of 6.45 × 6.45 – a square within a square – but there was to be much more to this Nordic summer home than an apparently simple Classical plan (Figures 45 and 46).

FIGURE 45 Villa Oivala Plan, Credit – John Stewart 1. Entrance 2. Courtyard 3. Covered Dining

FIGURE 46 Villa Oivala Section, Credit – John Stewart.

Approached from the forest, this low, timber-clad, pitched-roof structure appears to be a modest local vernacular building – more woodsman’s cottage or humble Ostrobothnian farmhouse than Roman villa – but it slowly and surprisingly reveals itself to be something much more subtle and sophisticated (Figure 47). The untreated timber walls are boarded vertically below a diagonally tiled (originally wood-shingled) roof, served by carved wooden gutters. The main entrance door is boarded in a traditional diagonal rustic pattern (as Aurejarvi Church 1921–1924) but on opening, it transpires that this is not in fact the door into the house but a set of gates through which we can glimpse a small courtyard, or atrium, apparently ringed with a pale-blue timber colonnade. Our route leads on across this courtyard by a simple path to a covered terrace on the far side. This is a true outdoor room – a small clearing of civilization and sophistication in the midst of the forest. Though the geometry is formal, the atmosphere is relaxed, softened by the rustic timber and the climbing plants, which scramble up columns and around the eaves, providing an informal and ever-changing decoration to the architecture. The space clearly derives from Roman domestic architecture – the colonnaded peristyle courtyard of the House of Pansa in Pompeii, which Oiva must have recently visited, being but one possible inspiration7 – but it is unmistakably Finnish too – set within the forest and made from the forest’s wood (Figure 48).

FIGURE 47 Villa Oivala Entrance, Credit – Martino De Rossi/Collaboratorio.

FIGURE 48 Villa Oivala Courtyard, Credit – Martino De Rossi/Collaboratorio.

Architecturally, the courtyard is a subtle affair – at roof level, the square form is clear, but below that, the arrangement is informal and responds to the needs of the family. To the left, a solid wall below the roof provides enclosure to the main living spaces, while in front of us, the wall has dissolved into a colonnade which continues around the right side of the courtyard to provide a covered access to Oiva’s study, which overlooks the lake. Ahead, while the columns support the roof, the room beyond is completely open to the courtyard. A step takes us up into this space and to internal floor level – this is not so much a covered, outdoor space as an internal room with the courtyard wall removed. From this space, three full-height glazed doors open to the view of the sea beyond, and a small timber deck (with wooden peristyle columns once more) provides a further external covered space, from which to fully enjoy the view of the rocks and water (Figure 49).

FIGURE 49 Villa Oivala Lake Elevation, Credit – Arkkitehtitoimisto Livady.

Our route has taken us from the darkness of the forest through the light of the courtyard, under the shade of the covered room and deck, and on to the view of the sparkling sea, rocks and islands beyond. This studied combination of both indoor and outdoor spaces – some covered, some open to the sky, some inward looking, others outward – celebrates the natural setting and offers a relaxed, yet sophisticated, retreat from city life, thus becoming a prototype for many of the twentieth century’s best Scandinavian summer homes.8

The Pompeian Atrium House was a constant domestic model for the Nordic Classicists, and indeed both Ragnar Östberg, in his Villa Geber of 1911, and Ivar Tengbom, in his Villa Tryggerska of 1914, had responded to the long site plots of the Diplomatic Quarter in Stockholm with houses organized around enclosed or partly enclosed entrance courtyards, in both cases with what was apparently the front door of the house leading into the courtyard. What differentiates and raises the Villa Oivala to a different level of architectural achievement however is Kallio’s perfectly balanced interplay between Classical perfection and domestic informality. As Malcolm Quantrill observed,

although the plan of this summerhouse is ostensibly classical and symmetrical, it has been freely adapted for its function, which is one of informality. Informality is certainly the theme of the villa’s atrium, which becomes more of a patio, where the space and forms are softened by vines and irregularity. Poised between the classical and the rustic, between architecture and nature, it also occupies a position (both historically and conceptually) between Eliel Saarinen and Alvar Aalto.9

Internally, the rooms are simply finished, as befits this rustic retreat. Plain timber boarded walls contrast with the white-painted masonry fireplaces. These are at once the simple fireplaces of every Nordic country cottage but are also transformed through a stepped mantelpiece to become lost Classical fragments within the woods.

As with all Oiva’s buildings, few drawings remain; it was his unusual practice to destroy his drawings on a building’s completion. In the case of Villa Oivala, one surviving sheet shows plans, sections and elevations as well as some of the timber detailing. The walls are simply double planks, nailed together, giving a total thickness of two inches, which helped to speed construction and were sufficient for summer occupation. The villa has changed little from the original design, although Oiva made a number of slight revisions in 1936 when the brick fireplace was created in the centre of the courtyard and the building was repainted with the original pink timber columns in the courtyard being changed to pale blue and the outside of the building being painted the white, which we know today.

In 1929, Oiva further developed the site with a sauna, which he placed separately from the main house on the rocks by the water. This is in traditional Finnish wooden construction with cross-jointed circular logs under a low grass roof, which cantilevers out over the entrance steps, thus providing another covered seating area from which to enjoy the views of the surrounding islands. Internally, a tall wooden clock, stone fireplace and bed in the entrance space allow it to double as a guesthouse. Again, as with the main house, Oiva’s sauna has become a prototype for many others – poised at the forest edge, on the rocks, by the water. His final intervention in the forest was a remote garden from the same period in the 1930s. Where once this boasted a pergola, pavilion and fruit trees, subsequent neglect has allowed the forest to almost subsume it once more.

The Villa Oivala is a key building of Nordic Classicism. It is one of the few domestic examples, which so effectively draws on an ancient Classical model and the local rural vernacular to achieve a building which is much more than the sum of its sources. What makes it not only important but also a particularly fine and lasting architectural achievement are the numerous contrasting themes, which Kallio has so brilliantly orchestrated in this, apparently modest, composition, restraint and yet richness, formality played against informality, containment and release, ancient and modern, sophisticated and yet rustic, humble and yet grand. The Villa Oivala has been described as a Kallio self-portrait10 – it combines the spirits of the mystical Northern forests with those of ancient Rome to produce a highly original, very sophisticated, piece of architecture, as well as the perfect setting for relaxed twentieth-century summer living.11