Edvard Thomsen and the Øregård Gymnasium

Edvard Thomsen was an important architect within the Nordic Classical Movement who like his fellow Dane, Carl Petersen, is famous principally for one building – in Thomsen’s case – the Øregård School in Copenhagen.

Its interior, in particular, stripped almost entirely of decoration, was hugely influential at the time and has more recently proved of great interest to many postmodern architects, in particular, the late twentieth-century Italian and Swiss Rationalists. It is Thomsen’s particularly Spartan approach, rather than the visual or symbolic richness of his work, that most characterizes him amongst his fellow Nordic Classicists. Born in 1884, a year before Asplund and Lewerentz, he was one of the younger generation who fought for Classicism, only to later abandon it for Functionalism.

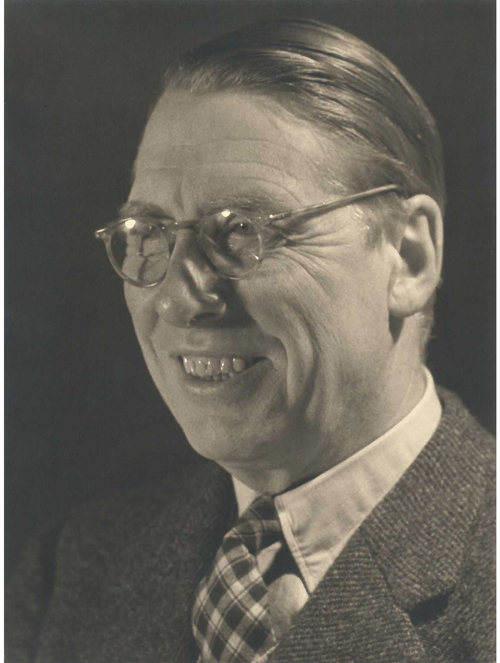

Thomsen’s father Edvard Johan Thomsen was a successful painter in Copenhagen, and for many years, it looked as if his son was going to follow the family profession. Edvard enrolled in the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts School of Painting in 1901 but while studying there, became interested in architecture, eventually transferring to the School of Architecture in1903 (Figure 56). In 1908, Hack Kampmann was appointed professor of the School of Architecture, and his teaching, in particular his focus on ancient Greek Classical architecture, was to have a profound influence on Thomsen. Encouraged by Kampmann, Thomsen spent a number of terms at the École Française in Athens, studying ancient Classical architecture at first-hand. He also travelled to Germany and France during a prolonged period of study, during which, in all likelihood, he would have seen many of the latest developments in contemporary European architecture, including both the industrial Classicism of Peter Behrens’s AEG factory (1909) and the expressed concrete frame of Auguste Perret’s apartments in Rue Franklin in Paris (1902–1904). He was also aware of the work of the highly influential Austrian/Czechoslovakian architect Adolf Loos and was present when Loos lectured in 1913 in Copenhagen on his book Ornament and Crime, which had been published five years earlier in 1908. Interestingly, despite the length of his architectural education, there is no record of Thomsen having made an Italian pilgrimage before finally graduating from the academy in 1914. He was an able student and went on to later win both the CF Hansen Medal in 1916 and the Gold Medal in 1918.1

FIGURE 56 Edvard Thomsen, Credit – Danish National Art Library.

After working briefly for Hack Kampmann, Thomsen started his own practice in 1915 with many of his early commissions being located in the growing suburb of Gentofte, north of Copenhagen. These included both private commissions, such as garages and workshops of 1916, and public commissions, such as a house for the homeless of 1917, and an old people’s home of 1918–1919 – all in a consistent, rather low-key, modest Classical style. As with most of his architectural contemporaries, these early commissions were interspersed with numerous architectural competition entries. During this period, Thomsen also joined the Free Architects Group, which had been founded by Carl Petersen (Ch 2) in 1909 of which Povl Baumann (1878–1963) and Ivar Bentsen (1876–1943) were also members. Their aim was the promotion and protection of Classical architecture, and Thomsen became secretary of the group before its eventual dissolution in 1919.

That year, Thomsen achieved his major professional breakthrough by winning the competition to redevelop the Railway Yards (Banegardsterraenet) in Central Copenhagen, for public housing, with Carl Petersen and Ivar Bentsen in second place. The competition had generated huge interest, not least because of the scale and location of the site, which, though backing onto the railway lines, stretched for almost 500 m along the bank of St George’s Lake near the centre of the city. Both the winning and second-placed proposals shared the same strategic approach, which was to build to the boundaries of the entire block and to then carve out courtyards from the mass to provide light and air to the apartments (in a similar approach to Kampmann’s Police Headquarters, which were then under construction, just a few blocks away).

Thomsen’s design was organized around a vast central hexagonal courtyard, centred on the axis of the bridge across the lake from which the space extended to the north and south, terminating in semicircular arcades at either end with giant archways cutting through the mass of the apartments to reach the courtyards within. The vast, largely unbroken, repetitive facades were conceived by Thomsen both as a calming foil to the increasingly chaotic streets around them and as a humble, understated, background building within the city against which the richer public buildings would contrast and assert themselves (no doubt inspired, like so many of his contemporaries, by the writings of the Austrian architect and city planner Camillo Sitte).2 Like Oiva Kallio’s contemporary competition-winning plan for Central Helsinki, the design was further developed over the next ten years, during which time it was transformed into a Functionalist proposal before eventually being finally abandoned. Although the project remained unbuilt, it had hugely raised Thomsen’s professional profile and led to a teaching appointment at the Royal Danish Academy the School of Architecture in 1920, a post he was to hold for the next thirty-four years.3

In 1922, an architectural competition was held for the design of a new secondary school in Hellerup, Copenhagen. Plockross School, which had been founded in 1903, had taken over Gentofte School in 1919 and now required a new building for the new combined school, which was to be named the Øregård High School (1922–1924 ) (or Gymansium, as it became known). Thomsen won the competition with a Classical design, which, having been much refined prior to construction, was to become both his greatest achievement and one of the most influential buildings of the Nordic Classical Movement. The Øregård School is dealt with in detail below.

With his professorship, the completion of the Øregård School in 1924, his ongoing work on the redevelopment of a vast tract of Central Copenhagen and with Hack Kampmann’s death in 1920, and Carl Petersen’s in 1923, Thomsen became the unofficial leader of his profession in Denmark.

In 1928, he entered and won the competition for the design of the new Søndermark Crematorium (1926–1930) with Frits Schlegel. This was his first major commission since the completion of Øregård School and built on his previous unsuccessful competition design for the Ordrup Crematorium (1927). The building was built in a dull red brick with the north-facing ground floor, decorated with four continuous rows of brick-arched recesses (like a columbarium or Mediterranean walled cemetery) from which the chapel rises as a plain brick box. The limestone moulding to the main entrance door is continued in stepped blocks up the face of the chapel wall, where it is transformed into a relief of an angel, sculpted by Einar Utzon-Frank (1888–1955).4 The building is organized around a low courtyard with double-height chapel to the west, and columbarium and small courtyard to the south. The early competition images of the main chapel show an interior rich with rustication below Classical friezes, whereas the final building is stripped of almost all decoration with only one high window to the side of the chapel, which (in contrast to Lewerentz’s use of a similar device) appears simply utilitarian. Only the low domed waiting room has any real architectural quality, and the complex as a whole is quite depressing (even when not in use). Lisbet Balslev Jørgensen commented of Thomsen and Schlegel that ‘together they overcame classicism’5 and at Søndermark, this process is clearly underway.

In 1928, they were also commissioned to undertake the design of a number of buildings for Copenhagen Zoo, with most of the buildings, such as the giraffe and monkey houses, completed in Functionalist style in the 1930s (and subsequently replaced). The year 1928 also brought a further secondary school commission for Thomsen – the Gentofte Gymnasium of 1928–1930 (which was carried out with Niels Hauberg). Here, his design is a reworking of Øregård, although this time he has returned to his, now favoured, red brick. Once more, we have a central glazed entrance, central main staircase, top-lit atrium, and with the main floor, half a storey above a semi-basement. This is an elegant solution, which has perhaps more in common with Peter Behren’s (1868–1940) German Industrial Classicism than mainstream Nordic Classicism. By now his incredibly efficient Øregård plan had been adopted as a standard for Danish secondary schools, and Thomsen continued to promote it. The year 1930 brought a further school design – this time for Husum Secondary School (1930–1932) – and once more the school is organized around a central glazed atrium within a rectangular four-storey building, this time flanked by symmetrical single-storey wings. The red brick elevations are reduced to the point of meanness, and significantly, the window proportions are now horizontal, suggesting the growing influence of Modernism on his work.

In 1930, Edvard Thomsen was commissioned by Copenhagen City Council to design a new building in Christianshavn. The Social Democratic Mayor Peder Hedebol (1874–1959) wished to address the chronic shortage of social housing within the city and to also build a new, model, social apartment block, which would include a pharmacy, bank, post office and shops at ground-floor level with forty-eight apartments above. This was to be both Thomsen’s first essay in Functionalism and first experience of the occasionally vitriolic nature of local politics.

Thomsen’s design for the apartment block confirmed his now total rejection of Classicism in favour of Functionalism. The entire building is horizontally banded, both expressing the floor levels of the concrete frame within and dividing the rendered facade into alternating cream and grey bands, which quickly earned it the nickname of Lagkagehuset – ‘the sponge cake’ (by which it is still known today). The corners of the block have wrap-around glazing and cantilevered balconies – again expressing the buildings’ concrete framed structure (in contrast to the solid, load-bearing structures of Classical architecture). Today, it fits quite happily into the street scene, but in the early 1930s, its introduction to the historic Christianshavn area of the city caused outrage.

Opposition to the apartments started almost as soon as the site was cleared to reveal a new view of the Church of Our Saviour (1695), which local residents were keen to retain. Thomsen’s design completely filled the block, screening even the tower of the church from view and resulting in a highly political battle developing within the city council. Things only deteriorated when construction started with the mayor requesting both additional accommodation, including the introduction of a public library, and costly changes, such as the replacement of the original granite to the base storeys with marble. Within months, the cost of the project had spiralled out of control, and with pressure mounting on the mayor, Thomsen became the scapegoat. It was a bruising and painful process and left Thomsen’s reputation badly damaged.

Perhaps, as a result of this experience, Thomsen began teaching more and practising less during the remainder of the 1930s. By the end of the decade, he had added little to his portfolio when his father offered to fund the development of a block of flats on Ørsted Road in Frederiksberg in 1939 (parental commissions more usually being carried out to kick-start an architect’s career, rather than to revive one). Thomsen’s design was a radical experiment in expressed reinforced concrete, which was then highly innovative for Denmark and resulted in his most successful Modern design. The influence of Le Corbusier (1887–1965) is strong, with the Salvation Army Refuge in Paris of 1933, proving to be the principal source with the clear expression of the different functional elements within the building, the angled upper storeys and the use of primary colours, glass blocks and ceramic tiles, by now familiar elements of Le Corbusier’s architectural vocabulary. Nevertheless, it is a very well resolved design, which must have impressed Thomsen’s contemporaries (if not the local residents).

The Frederiksberg flats were to become Edvard Thomsen’s last significant contribution to the development of Nordic architecture. Further commissions such as the Odense Stadium (1939–1942) and his buildings for the National School of Physical Education (1940–1941) were pared-down, steel-framed designs, which reeked of wartime austerity. Further apartments in Aarhus (1942–1945) and Copenhagen (1943–1947) with CF Muller (1898–1988) and Gunnar Krohn (1914–2005) were pedestrian affairs – four storeys of white render with recessed balconies below pitched, tiled roofs. The new reinforced concrete water tower of 1955 for Jaegersborg was his last built design. He had stopped teaching a year earlier at the age of seventy.

Edvard Thomsen could look back on a career of considerable achievement. He had been awarded Commander of the Order of Dannebrog and Dannebrogsmand, was Knight of the Legion of Honour and of the Norwegian St. Olav’s Order, an honorary member of the Architectural Association in London and of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He had been a highly regarded teacher at the leading School of Architecture in Denmark for thirty-four years and Director of the Royal Academy from 1946 until 1949. Nevertheless, like many architects of the period, the quality of his work was inconsistent. In his old age, he had the humility when viewing his successful competition entry for the Railway Yards project to comment, ‘Thank heavens it never came to anything.’6 He also recounted, looking back, that it had ‘not been easy to wriggle out of Classicism’s embrace’.7 In doing so, he had abandoned the style which had brought him his greatest lasting achievement – the Øregård School in Hellerup, Copenhagen.

Øregård School (1922–1924) (with GB Hagen)

In 1919, it was decided to amalgamate Plockross School in Hellerup and Gentofte School to create a new secondary school, which was to be called the Øregård Gymnasium. The new combined Øregård School Board initiated an architectural competition in 1922 for a new building on a site they had acquired in Hellerup in the wealthy suburbs of Copenhagen. To support the Classical educational aspirations of the school, the competing architects were invited to submit designs for a Classical building.

Thomsen had already carried out a number of projects in Gentofte and would have been particularly interested, not only in this further significant opportunity in the locale but also in the request for a Classical design. He realized, however, that despite his local knowledge and position as the new Professor of Architecture at the Royal Danish Academy, he had no educational design experience and would be competing against other architects or teams of architects with an established track record in school design.

Having reviewed his options, he approached Gustav Bartholin Hagen (1873–1941) who had recently completed the new Halskov School, a year earlier in 1921, in Classical style. Hagen was already an experienced architect, having established his practice, while Thomsen was still studying in 1907. He had visited Italy in 1910 and had completed a considerable number of projects in addition to the Halskov School, including the Headquarters for Kobenhavns Belysningsvaesen (the municipally owned gas and electricity company) in 1913 – which is an important Danish National Romantic building. The two architects therefore established a new temporary partnership, which combined local knowledge and educational design experience with a shared enthusiasm for Classical architecture, which as a result secured them first place in the competition.

FIGURE 57 Øregård School Plan, Credit – John Stewart. 1. Entrance 2. Atrium 3. Classrooms

FIGURE 58 Øregård School Section, Credit – John Stewart.

Their entry provided a refined and rather elegant solution to the school design and, in addition, organized the entire site into a Classical landscape in which their new ‘temple of learning’ was to be set. From Gersonsvej to the west of the site, they created a broad, raised courtyard between two single-storey, semi-circular exedra, thus providing an appropriate approach and setting for the main school building. This space was in turn dominated by the ionic portico of the main entrance at the top of a flight of steps, half a level above this entrance court. To the south of the entrance court, on axis, was proposed a Classical villa for the principal (with its own access from the street) and to its side, directly facing the southern elevation of the school, a scaled-down Circus Maximus, enclosed by Cyprus trees and with stepped grass banks for spectators (chariots were the only element missing from this design).8

The school building itself had a simple and well-resolved plan. It offered a long rectangular building parallel to Gersonsvej, organized around two courtyards on either side of a central staircase. The central main entrance provided a graceful transition from the street entrance court – via a half flight of steps, through a partly engaged grand ionic portico – into a long cross hallway, which repeated the semicircular exedra ends of the entrance court. From here, the double central stairs provided access up to the floor above and down to the semi-basement. The courtyards on either side of the stairs – or to be more accurate, the light wells – were raised half a floor above ground-floor level to provide two, one and a half height gymnasia at basement level, which in turn were lit from above by three roof lights in each case. Oval high-level windows within the light wells would have provided natural light to the surrounding ground-floor corridors.

Externally, the elevations were extremely restrained. Beyond the double-height ionic portico, large vertical windows light the two upper floors of teaching accommodation, while the semi-basement is lit by horizontal windows within the same vertical alignment. Above, a frieze and balustrade terminate each elevation and screen the roof. All in all, it was very much the Classical Academy to which the school had aspired.

As a design, the competition winning entry is consistent with Thomsen’s previously completed buildings, including both the house for the homeless and old peoples’ home nearby, with the ground floor raised in both cases on a semi-basement stereobate or podium, with large vertical windows to the upper floors, narrow horizontal to the semi-basements and a central entrance approached by a generous flight of steps. The principal variations are the introduction of the light wells or courtyards and the change from brick to render (which added so much to the success of the final building), which was consistent with Hagen’s previous school designs.

Despite the initial attractiveness of Thomsen and Hagen’s Classical landscape, further consideration led the board to conclude that the long rectangular plan of the school building left insufficient external recreational space for a school of this size. Nonetheless, Thomsen and Hagen were appointed and asked to revise their design to provide a more compact building. This meant that the two courtyards had to go and were effectively combined into one central courtyard, with the original central double staircase moved forward to make way. To then convert this courtyard into an internal space, which was lit from above, was but a short step, and in doing so, the architects made the most significant move towards the organization of the school as we know it today. While Thomsen receives most of the credit for the design of the Øregård Gymnasium, Hagen’s role in this crucial design decision, in particular, should not be underestimated. We only have to look at his completed design for the Halskov School to see a very similar top-lit double-height space, surrounded by columns between which span simple wrought-iron railings, to recognize that the key, brilliant central atrium space at Øregård is clearly a development of Hagan’s earlier design.

What Thomsen and Hagen achieved together was to take the idea of a top-lit, double-height Classical courtyard and develop it, not only as the principal internal space but as the core circulation space for the entire school. The atrium was thus surrounded on both floors on all four sides by a colonnade, which provided circulation for almost all the teaching spaces. This represented a dramatic move away from the double-loaded corridor plans, which were then the norm for secondary schools throughout Scandinavia and much of the rest of Europe (such as Gunnar Asplund’s Karl Johan School in Gothenburg of 1915–1924). With the atrium (or aula as it is often referred to) at its heart, the plan was then refined into a symmetrical arrangement of rectangular golden section, hall, within an almost perfectly square, overall block. The result was an incredibly efficient school plan (which became used as a model throughout Denmark until the 1940s). More than that, however, the architects had symbolically placed the school community at the very heart of the building with the atrium space now clearly the most important, both architecturally and socially.

One further step was required, however, before the architects reached their final solution, which we see today. The drawings, which were submitted to the Gentofte Municipality for approval on 15 November 1922, show the plans and elevations, which we are now familiar with, but the sections of the school show a very different treatment for the atrium. Rather than the three-dimensional frame below glazed ceiling grid, this earlier proposal shows the colonnades to the atrium as a series of two-storey arches with the first-floor slab recessed to allow the columns to be read as full height, rather than as part of a frame.9 Just as significantly, the glazed gridded ceiling has not yet been developed and the atrium, instead, has a flat ceiling with a long rectangular opening (in proportion to the ground-floor plan of the space) above which sits a glass rooflight, which is wider than the opening itself, allowing access around the opening at the level of the flat roof above. This treatment of the roof to the atrium, therefore, is still much closer to Halskov than to the final solution, and it required considerable further refinement by both architects to reach the elegant atrium space that we now know so well (Figure 59).

FIGURE 59 Øregård School Atrium, Credit – Jens Kristian Seier.

Thomsen’s previous suburban palazzos and Hagen’s school planning and rather clumsily detailed Halskov atrium had got them this far, but what other influences were brought to play in making the next leap forward? Surely Adolf Loos deserves a mention. We know Thomsen had heard him speak in Copenhagen, and his rejection of ornament, clear expression of the structural frame and use of marble, in contrast to plain white surfaces in his buildings (such as the Goldman and Balaatsch building (1910–1912) and American Bar (1907–1908) in Vienna), are key elements of the final Øregård atrium. The main hall of Otto Wagner’s (1841–1918) Postal Savings Bank in Vienna of 1904–1906, with its white frame and glazed gridded ceiling, must have also been known to both architects and is the likeliest inspiration for their final gridded glass solution. None of this detracts from Thomsen and Hagen achievements, however, as their building, far from being a collage of borrowed elements, is a superbly refined, complex three-dimensional design whose principle space – the Aula Cultus – is one of Nordic Classicism’s finest interiors.

While Halskov had been the starting point, the final design of the atrium at Øregård has a rationale, sophistication and refinement, which is of a much higher order. Here the colonnade is continuous and levelled with the adjacent spaces, and detailed with a lightness and restraint, which was entirely lacking in Hagen’s school. The proportions of the colonnade on both floors have been carefully considered with five bays to east and west and seven to north and south. Three bays across both floors create a perfect square, and the slightly elongated single bay thus created is used again and again throughout the building as the proportion for all door and window openings. This elegant structural frame has been stripped of all Classical detail and is finished in a polished stucco lustre marbleized plaster. The marbleized plaster continues through all the circulation spaces of the school, accompanied by the simplest of details: brass coat hooks; plain wooden benches; wrought-iron balustrades; several inset Classical friezes by Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844), over doorways and to the stair landings; and dramatically – on the far side of the atrium, opposite the main entrance – Thorvaldsen’s sculpture of Jason. It is hard to imagine a more appropriately Spartan setting for this Greek mythological hero. The Greek theme continues with a running key pattern (as Halskov) under the cornice below the ceiling, which is the only decoration in the space, and above that is the extraordinary gridded glass ceiling. The structure of the ceiling is unseen, allowing the shallowest of arches to be created to enclose the space, through which subtly modulated daylight floods the whole luminous atrium. The artificial lighting for the atrium is also entirely concealed above the glass ceiling so that the source of natural and artificial lighting is the same, and the purity of the space is undisturbed by modern electrical fittings. The design of the atrium is Classical architecture but striped to its bare essentials of pure geometric form and perfect proportion.10

Externally, the same purification process has taken place between the competition-winning design and the completed building (Figure 60). The central ionic portico has been replaced by three tall, diagonally glazed metal entrance doors with transom lights over, which are cut deeply into the facade. The Classical frieze above the rendered facade survived, but the balustrade of the earlier design has been replaced by a simple cornice. The windows and door openings have the simplest and yet most elegant concrete frames, which cast deep shadows, contrasting strongly with the darker render and further emphasizing these boldly recessed openings. The enclosed entrance court has gone, but the simple stairs which lead up to the entrance doors start a subtle route, nevertheless – from courtyard up a quarter of a flight to the doors, across the vestibule – up another quarter of a flight to the colonnade and then on from the darkness of the stairway to the brilliant light of the atrium. The whole building has a subtelty, consistency and precision which neither Thomsen nor Hagen was to achieve again (Figure 61).

FIGURE 60 Øregård School Entrance Elevation, Credit – Anja Wolf.

FIGURE 61 Øregård School Entrance Elevation Detail, Credit – Anja Wolf.

The one casualty of the move from the competition-winning design of the double courtyards to the final atrium design was in the semi-basement, which lost its two top-lit spaces below the courtyards to be replaced by a fully enclosed hypostyle hall of twenty-four square columns below the atrium. This space was originally surrounded by a solid wall below the columns of the atrium with circular openings punched through each bay to the surrounding corridor but, as part of a refurbishment of the building in 1977, these walls were removed and the columns of the atrium taken down through the semi-basement, thus linking the hall with the surrounding circulation space and reducing the claustrophobia somewhat. (Despite its rather oppressive nature, it remains a popular space with students.)

Most importantly of all, Øregård Gymnasium is an extremely successful school building, which continues to be used today much as it was used when it opened almost a hundred years ago. The wonderful atrium still holds assemblies, concerts, graduations and dances (although modern black-out requirements are a challenge), and in our modern social democratic age, both pupils and staff are now allowed to take shortcuts across it, whereas earlier access across the central space was reserved for adults. While there have been numerous alterations and changes made within the blocks of the plan, nothing has been done to seriously detract from the original design, and indeed the space between the street and the school has been much improved by elegant new steps by Frederiksen & Knudsen (2003), which replaced the original, rather starkly detailed, piano nobile. The basic logic of the building works as well as ever, and Thomsen and Hagen’s Spartan Aula Cultus remains much loved and highly appreciated by continuing generations of both pupils and teachers.

The design of the Øregård Gymansium is understatement brought almost to the point of abstraction and yet saved by the exquisite proportions of every element. The design of the atrium is close to architectural perfection. It has inspired generations of architects from early Functionalists to Italian Rationalists and postmodernists and constitutes one of the greatest achievements of the Nordic Classical Movement.