6 |

Capabilities-Led Transformation |

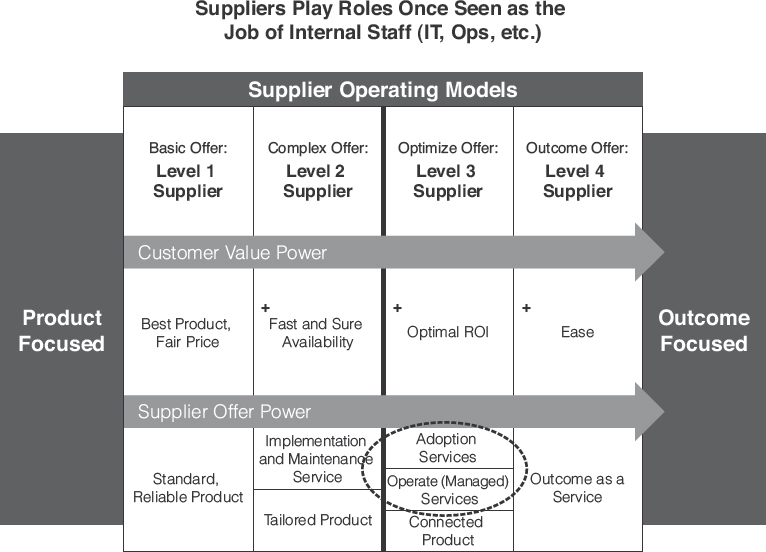

BECAUSE WE BELIEVE THE SUPPLIER’S OPERATING MODEL IS THE KEY lever in improving customer outcomes, we will start the “how” conversation from the supplier side. Let’s begin that discussion by touching on an experience familiar to many Level 1 and Level 2 suppliers. It is one that we think can be very instructional as a reference point—a reference point for both what to do and what not to do in any upcoming transformation.

Suppliers have long known that a great way to increase the market penetration and/or extend the life of a product or core technology is to segment the market and develop targeted offerings. In the world of software, this was most often accomplished through vertical market versions of the product. For example, by building in key features that the banking industry or the insurance industry needed most, suppliers could reduce the need for customers to customize their generic, cross-market product. That made the offer easier and more practical for companies in those vertical markets to purchase. In hardware or industrial equipment, the niche game was often about finding specific markets that needed specialized versions of the core technology. Sometimes it meant special housing that accommodated a rugged environment. Other times it meant developing special-purpose variants on the product for industries such as health care or process manufacturing. These techniques for increasing market adoption or extending product lives are hardly new. Manufacturers and software companies have used them successfully for decades.

Two lessons from this experience are relevant to our conversation: First, it works. Second, it has an impact on a supplier’s cost structure. As we have often said, suppliers prefer to stay close to their product. In a perfect world, it would be a standard, generic product with broad cross-market appeal. For suppliers, this is usually the optimal profit model—one that allows them to achieve maximum scale with minimal friction. The minute they start down the path of developing niche versions of their cross-market product, they have to start focusing on more than one target audience. They now need multiple iterations of that product, increasing their development and manufacturing costs. They may need new knowledge in the sales force or a different reseller channel. They may have to start unique marketing campaigns for each target niche. In short, they have to focus on the different needs of multiple sets of customers, not just one. Historically, this multi-market focus has led to some redundancy of effort, even to parallel organizations within the same supplier. In some cases, it has actually triggered huge reorganizations by suppliers: They slice up the different functions such as R&D, sales, and service into separate market-specific teams and then stitch them back together vertically into what management believes will be more nimble, market-focused business units. They are almost like companies within the company.

We fully understand why B2B suppliers often reach the conclusion that successful focus requires dedicated organizations. In traditional B2B, we support that it was often the right decision. But we question whether it is the right approach in B4B.

This is because we think the need for “focus areas” is going to increase exponentially. If every new focus area means a new organization (what we will refer to as focus = organization), suppliers’ cost structures will soon spiral out of control. In many high-tech and near-tech markets in which product prices and margins are falling, this seems like a recipe for disaster. Instead, we think suppliers need to increase the aptitude of their core organizations to be capable of multiple focus areas at once. Only then can they retain the economies of scale that will be so important to future profitability. We realize that this is a huge challenge, one that many smart companies have already tried to conquer to little avail. In fact, we think it has been a major reason why the early pioneers of operating model transformation have struggled to achieve the level of success they had hoped for.

Early Efforts to Transform

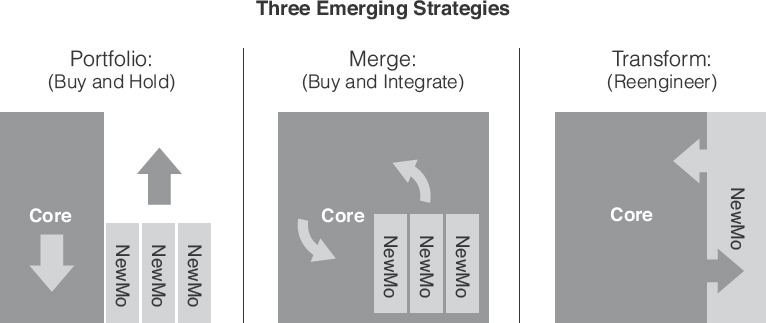

There have already been a number of interesting attempts to transform from a Level 2 supplier into something that has a similar shape and form to Level 3 and 4 of B4B. We can identify at least three approaches that companies have taken to get there, as shown in Figure 6.1. These represent different paths to managing the introduction of a new model to the large, established core operating model of a supplier.

FIGURE 6.1 Three Emerging Strategies

Let’s discuss these from left to right because, so far, most of the attempts to transform Level 2 suppliers have been made by acquiring new model (NewMo) companies.

In 2008, HP bought EDS. In HP’s press release, then-CEO Mark Hurd said, “This reinforces our commitment to help customers manage and transform their technology to achieve better results.”1 Sound familiar? It did not take long before others got into the transformation game through acquisition. Just one year later, in 2009, Xerox bought outsourcer ACS (Affiliated Computer Services) for $6.4 billion. In the Xerox press release, CEO Ursula Burns said, “By combining Xerox’s strengths in document technology with ACS’s expertise in managing and automating work processes, we’re creating a new class of solution provider.”2 Sound like a Level 2 supplier buying its way into Level 3? That same year, Dell spent $3.9 billion to acquire Perot Systems with much the same storyline (great tech products company buys great tech services company to create great new outcome-focused company).

All of these were examples of hardware companies trying to guard against commoditization at Level 2 by moving to a new model that they hoped would create differentiation, value, and profitable growth—just like it had for IBM. EDS, ACS, and Perot were often referred to as outsourcers in those days, but what they all had in common was an operating model that tied them closer to their business customers’ actual outcomes. They didn’t just sell them products. They also tried to help operate the products. They tried to help drive better outcomes. They tried to be game changers. Clearly the intent of the CEOs of HP, Xerox, and Dell (using our language) was to transform parts of the parent companies from being Level 2 complex offer suppliers into being Level 3 and Level 4 outcome suppliers.

There was also a wave of movement in software, storage, and network markets. Once SaaS established itself as a viable and disruptive business model, several large Level 2 suppliers began buying the NewMo provocateurs. Cisco bought WebEx in 2007. In 2011, traditional software giants like Oracle and SAP led an army of companies eager to gobble up interesting NewMo companies such as Taleo, RightNow, and SuccessFactors. To compete with AWS, EMC formed Pivotal from its Greenplum acquisition in 2013. It was a different cast of characters acting out the same storyline: traditionally profitable Level 2 companies furiously moving into high-growth, new model spaces.

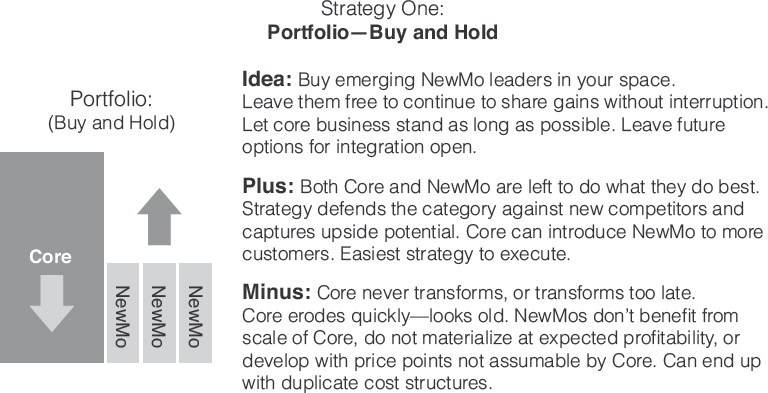

We worked with the big hardware companies before and after their 2008/2009 acquisitions. In the software wave, we had front-row seats to the action. We had worked with the big companies, we had worked with most of the pre-acquisition SaaS companies, and then we worked with the combined entities. In looking across them, two classic acquisition integration patterns can be seen. The first is the portfolio strategy, shown in Figure 6.2.

FIGURE 6.2 Strategy One: Portfolio—Buy and Hold

You might look at this as a way to place smart bets on the future. Large Level 2 suppliers took advantage of their big balance sheets and large market caps to buy upstart, NewMo companies that were either competitive or complementary. This strategy has many potential benefits. The first is defensive. They buy the right to eliminate the NewMo company as a competitor. Second, they buy growth. This strategy is both easy to understand and relatively easy to execute. In particular, if you got these companies early enough when the price was reasonable, it made a lot of sense. If you waited too long, they could become quite pricey—for example, Oracle’s buying salesforce.com today rather than in 2004.

The problem with the portfolio strategy is that it rarely transforms the core of the new parent. Since most large suppliers think that focus = organization, they leave the acquisition’s organization separate to “do its thing.” The attributes that made the NewMo successful sit ensconced in their shell. The core hopes that NewMo will grow big enough and fast enough to someday be a meaningful contributor to the core’s income statement. Large suppliers often place multiple bets by buying a number of NewMo companies that may have this potential. Perhaps one acquisition’s “thing” could even grow large enough to become the new core. But so far, that has rarely happened. EMC’s acquisition of VMware has been a great success, but it still sits mostly separate from EMC’s core. EMC seems to have organized Pivotal in a similar manner, as a separate brand and as a mostly separate organization. Fortunately for EMC, its core is still profitable and modestly growing, so it retains the option of merging the portfolio later. For other suppliers, their cores may already have begun deteriorating. They may need to move faster in their transformation efforts.

Although we have not really counted hands, we would guess the portfolio strategy is the favorite of Level 2 supplier CEOs, especially ones who believe that focus = organization. It is both defensively and offensively advantageous, and it requires “only” cash or stock, not gut-wrenching organizational transformation.

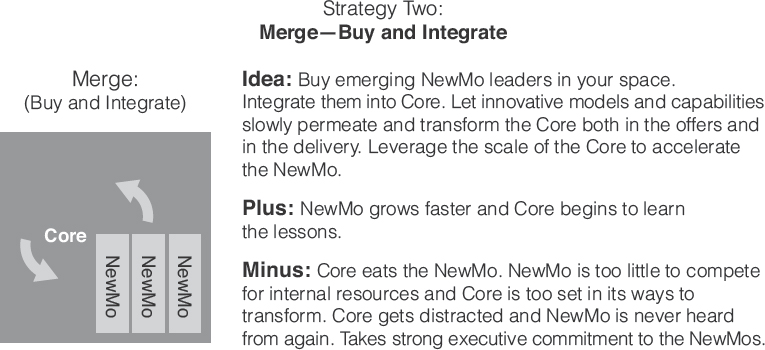

The second strategy is to merge. We think the merge strategy, so far, has the best potential and the worst results. You can see the potential for problems just by looking at Figure 6.3.

What happens is that the massive weight of the core can easily crush the innovation of the NewMo company. The crushing is not intentional. The logic is that the core is a massive, experienced giant compared to the cute, naïve upstart. The core wants to help “mature it,” to put it on the big-time Level 2 platform. Doing this misses the point. Just as the B2C companies have become the teachers, the Level 3 XaaS companies often have much to teach their new owners. But so far, they have struggled to get to the chalkboard.

FIGURE 6.3 Strategy Two: Merge—Buy and Integrate

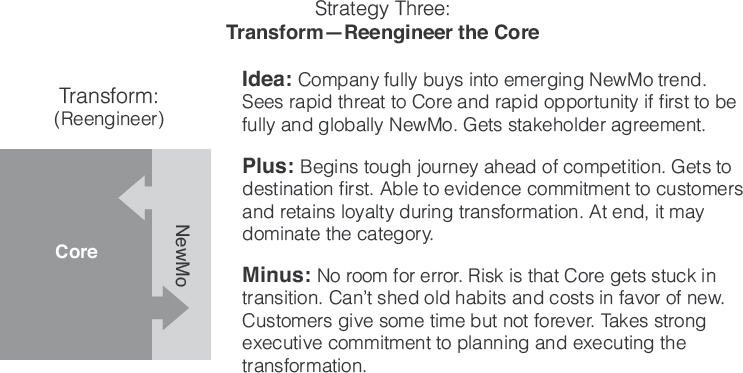

The strategy that seems the most difficult (and the least attempted) is transforming the core (see Figure 6.4).

FIGURE 6.4 Strategy Three: Transform—Reengineer the Core

We would argue that the main obstacle to transforming the core is simultaneously achieving multiple focus areas. The difficulty of teaching the old dog new tricks in the past has led many executives to conclude that a new focus area can only be successful if a separate organization is established. Let us give you a real-world example of this belief that is being played out all over the high-tech industry right now: the building of new managed services organizations.

TSIA data clearly show that the fastest growing of all hightech service lines is managed services. The cloud and connected products have enabled some suppliers to take over many system management tasks that their business customers used to do internally. Because they have better tools to automate those chores and because they can use those tools to serve many customers at a time, they can offer lower prices and sometimes better performance than the old in-house alternative. As we said in Chapter 4, it makes sense, and the market is responding positively.

Inside many large Level 2 high-tech suppliers today, there is a turf war going on over who gets to run the managed services business. The executives who run the professional services organization think they should own it. The executives who run the customer service and support organization think they should own it. Both can build a great case for why they are the best choice. Know who’s winning? Neither. In most companies today, cloud-based managed services are being established as a separate organization. So now there aren’t just four commonly distinct service organizations in high-tech; there are five. When adoption services become reality, there could be six. And if the supplier moves to Level 4, there could be seven or eight.

We don’t think this model works. This is not teaching the old dog new tricks; it is just adding more dogs. This doesn’t transform the core; it simply enlarges it, one organization on top of another on top of another.

Merging Capabilities

Of the three transformation strategies that large suppliers have been using, we like the merge, but not necessarily the way it has been done so far. We think most Level 2 suppliers have been buying organizations when what they should be buying is capabilities.

The concept of capabilities in business is certainly nothing new. In the last chapter, we provided the definition we use at TSIA: Capabilities represent the organizational ability to achieve desired results. They could be processes, skills, metrics, or technologies. We view capabilities as the building blocks of a company’s operating model—for both suppliers and customers. We think they will achieve a whole new level of significance in B4B. Quite simply, the potential to do new things, achieve new results, supplant labor, and increase reaction times today is unparalleled. There has never been “connectedness” with business customers like this before, there has never been the potential for a Tower of Power at Level 3, and there has never been the ability to let data and analytics drive organizational reactions with such precision and scale. We have actually applied this approach to our research on well-run service organizations. We have identified the specific component capabilities that support services, field services, professional services, education services, and managed services organizations need to be successful. Now that we have identified them, we are going one step further, seeking out the industry’s best practices for each of these capabilities from across our 300 member companies. It is becoming a fact-based set of building blocks for how to make a tech service business remarkable. This is why we think—in fact, we know—that suppliers can now build their core organizations to handle many focus areas simultaneously.

We were talking about this using Amazon’s consumer e-commerce business as a simple example. Amazon started by selling books. It built an e-commerce platform to do so. Then it moved into other markets such as consumer electronics, apparel, and eventually lab equipment and industrial supplies. Imagine if Amazon had taken the route of focus = organization when it came to its platform! There might not be one Amazon.com platform; there might have been 20. Instead, it focused its resources on building a single, dynamic platform with diverse capabilities. That one website keeps adding new capabilities when new product lines require them. But for any one customer who is shopping for one thing, all he or she sees is the relevant platform capabilities. When you are buying clothes, you can look at them in different colors with one click, but not when you are buying books or TVs. By taking this approach, Amazon gained the growth benefits of diversifying into many market segments without compromising scalability. They appear to be taking that same approach with Amazon Web Services. While it does appear to have built a second platform for AWS, Amazon is expanding this platform into multiple new business computing markets without creating redundancy. Although we realize that there is a big difference between giving technology platforms new capabilities and giving organizations new capabilities, we think the example is instructive.

We are promoting the same concept to the thousands of senior technology service executives who are part of the TSIA communities in IT, health care, industrial equipment, and consumer technology. Each year we study how tech companies organize their service businesses. As we’ve mentioned, there are usually between three and six separate service organizations at most high-tech and near-tech companies. These suppliers have typically organized their services according to the focus = organization model by making each service line its own organization. We also study which functions within these organizations are globally managed and which are out in the field, reporting to geo leaders.

Rather than adding new service organizations, we recommend learning new tricks. We are working with members to develop a model for converged services. The critical concept behind converged services is “organizational capabilities.” In this model, some capabilities are shared among service lines while other capabilities are unique to specific service lines. We call for more investment in shared capabilities like service engineering, practice design, technology infrastructure, and knowledge management that are globally managed across all service lines. We also see more virtual teaming across service lines to help meet a large customer’s specific needs. We call for an increase in remote and a decrease in on-site service labor—again leaning toward more global management. Not everyone is happy about our stance. It means some independent fiefdoms may be less independent. But we think that this will be the trend in the industry—one with many financial and quality advantages. You can read more about Services Convergence principles in Complexity Avalanche3 or about current best practices at TSIA. But what it goes to prove is that we are on the cusp of decoupling the notion that focus must = organization, at least in services.

Earlier we said that we think the need for “focus areas” is going to increase exponentially in B4B. The mathematical permutations are intimidating. Take almost any supplier and multiply the number of products it offers by the unique markets it serves. Many will require more than one operating model. This could result in dozens or even hundreds of focus areas. Each one simply cannot be its own organization! Not even most of them can be. We need a more flexible core, not the Byzantine Empire.

To accomplish this, we suggest that they think as a flexible discrete manufacturer would. These companies procure different manufacturing capabilities that enable them to build different kinds of discrete products. Based on what their customers need them to manufacture, they can string those capabilities together in different ways: They can build to order. All they need is a work order, a design spec, and a bill of materials (BOM). They don’t build a separate factory for each production run; they use or don’t use certain manufacturing capabilities that they have procured over time. Certain new capabilities allow them to get into new markets. When they decide to enter a new market, the factory managers identify and add any missing capability to the plant. We think this is a useful way of thinking about how tech suppliers should build new operating models. In our converged services model, we think that someday soon a single global service “manufacturing” capability would be able to produce multiple, discrete service products.

As we said in Chapter 3, many Level 2 suppliers have been struggling to articulate simply and clearly what their new model is and how they will transform their company as a result. For example, if you were a Level 2 enterprise software company readying your first SaaS offering, you would want to explain the “big picture” in a way that was easy for employees to understand. You might accomplish this with a simple internal white paper in which senior management:

•explains what a Level 3 operating model is and why it is right for SaaS.

•presents the targeted financial model for a Level 3 SaaS supplier.

•identifies which target market segments will be served using a Level 2 operating model and which will now be served via Level 3.

•draws out your Level 3 Tower of Power.

•lists the capabilities you need to fuel it. Identifies those that already exist and those that don’t.

•articulates your plans to make or buy the missing ones and to update the existing ones when necessary.

•identifies where all those capabilities must “land” within the existing organizations. (Hopefully you are not creating lots of new ones!)

•states that employees will be trained to use the capabilities so they can begin to produce the new Level 3 SaaS offer successfully.

•provides a high-level project plan and a rough timeline for key milestones.

We realize there is a lot of executional complexity underneath these eight steps, but giving employees a simple primer on what you are trying to accomplish can work wonders.

The point is simply that by using the B4B framework and the notion of capabilities, we think that the new model transformation can be made evolutionary. That seems far more achievable than do the revolutionary changes we hear being discussed with much fear and trepidation by senior supplier executives who are expected to deliver both short-term profits and long-term growth. An orderly, capabilities-led transformation seems like just the thing they are looking for.

Then, if the CEO wants to go do an acquisition, you know what capabilities you are missing and whether a particular NewMo candidate can add to the production power of the core factory. Shortly, these new capabilities can be combined with existing ones to build a new supplier operating model that your Level 3 customers will love!

The Fish in the Middle

We just mentioned the dilemma facing executives whose shareholders want both short-term profits and long-term growth. This is a good description of the pressure facing roughly 100% of Level 2 suppler executives we talk with today. So let’s discuss the financial dimension of a capabilities-led transformation.

This chapter has been focused on how to add new capabilities in a logical, orderly way. But because B4B is about and, not or, the cost of existing capabilities cannot be dropped, at least not right away. Until there are substantive reductions in product complexity (we really have to get to work on that!), high-tech and near-tech companies will still need lots of expensive sales and service people to conduct business.

As a result, any new capabilities that suppliers need to add in order to play at another supplier level are going to add to short-term costs. But that is not the worst of it. There is a second, often simultaneous problem, especially in moving to Level 3 or 4.

That second problem is a revenue problem, specifically the timing of those revenues. As we said at the end of Chapter 1, most Level 1 and 2 suppliers are used to getting paid up front. Once they deliver their technology, they are able to recognize the revenue and collect the cash. The only thing they must wait on is their extended maintenance contract revenue. But starting at Level 3, suppliers usually offer OpEx pricing models such as subscriptions or pay-for-consumption. So far, the evidence that many customers prefer that model is overwhelming. Many of the traditional software companies that made the brave move to OpEx pricing alternatives have been surprised by how many customers have switched. When they do, instead of getting a huge chunk of revenue up front, suppliers must wait and defer those revenues over an extended period of months or years. The contract amount may be the same, but the timing of the revenue recognition is not. If enough customers switch from the CapEx pricing model to the OpEx one, the supplier’s short-term revenues dip compared to previous periods.

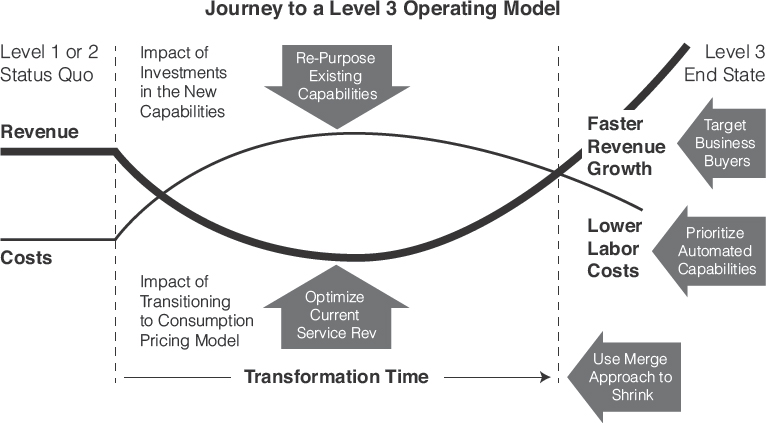

We drew these two transitions on a piece of paper using a status quo starting point. Then we drew one timeline that represents the short-term investment ramp-up period needed to create new organizational capabilities and a second timeline that represents the short-term revenue trough brought on by the shift to OpEx pricing models. Figure 6.5 shows what it looked like.

FIGURE 6.5 Journey to a Level 3 Operating Model

Yeah, OK, we know. It’s a fish. Can’t help that.

But know what? This fish must have been in a school at one time, because it turned out to be a pretty instructive creature.

On the far left, you see the status quo portrayed: fairly flat revenue with fairly stable costs. The space between those lines represents the profits of the supplier. The whole reason to embark on the journey is because of how those same two lines look on the far right (the “tail”). Revenues are now growing strongly thanks to the supplier’s new Level 3 or 4 offers. At the same time, new technology-fueled and data-driven operating models are driving down its labor cost. The far right looks a lot more fun than the far left, don’t you think?

The problem is the fish in the middle.

We don’t know of anyone who has started at Level 1 or 2 and has successfully transformed its primary supplier operating model to Level 3 or 4 without experiencing the fish. It is the fish that has most Level 1 and 2 CEOs hesitating. At the same time, they frustratingly watch as many NewMo start-ups get to found their company starting at the far right. They get the benefits of the new model without having to worry about their time as a fish.

Although we can’t completely eliminate the fish in the middle, what we have realized is that Level 1 and Level 2 suppliers can affect what type of fish they are going to be during the journey. The ones who plan poorly will be flounders: Their transformation will have a big fat body and a proportionately stubby tail. The ones who plan smartly using tactics such as those described earlier can be thought of as thresher sharks: Their transformation will have a skinny body with a very tall tail (see Figure 6.6). Threshers are fast and nimble.

If a supplier still has a healthy, growing core that does not require large revenue support from new model activities, then the portfolio strategy is fine. But for suppliers whose Level 2 core business is under pressure, we think the merge strategy has the best chance of making them a thresher and transforming the core, if they take a capabilities-led approach. They can pick up critical capabilities quickly via acquisition and pay for them by using the balance sheet rather than by using the income statement. Using some version of the eight-step approach we outlined, they can minimize the core’s transformation time and increase the size and the angle of their tail.

FIGURE 6.6 Journey to a Level 3 Operating Model

Whether you are a Fortune 100 product company or a $10 million reseller, if you are in high-tech or near-tech, we think capabilities (not organizations) are the right way to think about transformation. If you think you have plenty of margin room, then maybe you can afford to create new organizations every time you have a new product, market, or operating model. We don’t hear many of our 300 member companies describing themselves that way right now. Instead, they want to know how to be a thresher; they don’t have much choice. Flounders are not an option for them. Just know that whether you develop your fish plan in-house or with outside help, we know of plenty of tactics to accelerate the journey and increase the height of your tail.

The Grand Bargain of Customer Capabilities

We have spent the first part of this chapter talking about how capabilities-led transformations work on the supplier side. But it also applies to how customers might think about the new supplier operating models they are starting to hear about. As we have said, things will be changing for both sides of the great divide. Just like the examples we cited in Chapter 2 of how consumer behavior needed to change in order for e-commerce to become what it is today, business customers must also be prepared to undergo some behavioral changes. Allowing suppliers access to data is but one aspect of the grand bargain that customers need to make with suppliers in B4B.

You see, there is the matter of who does what.

Suppliers are going to play new roles in order to provide Level 3 and Level 4 outcomes to customers. But if they are going to be playing more of a role, that means someone may be playing less of a role. Often, that someone is an employee at the customer’s site. Thus begins the grand bargain.

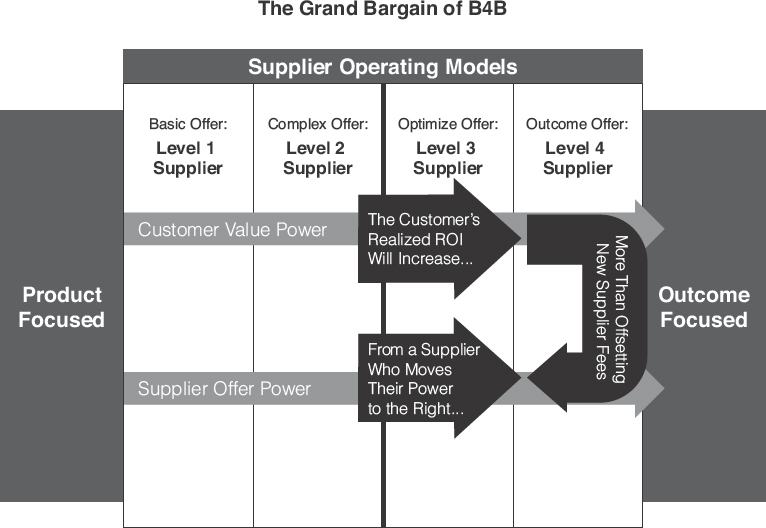

FIGURE 6.7 The Grand Bargain of B4B

The grand bargain, shown in Figure 6.7, is this: If a supplier takes a risk and makes these additional investments, and those investments lead to capabilities that improve the financial outcomes the customer receives, then the customer must be willing to return some of those benefits to the supplier in the form of new revenue. If suppliers are not compensated for these new services, it will not be sustainable, and few will make the leap. That would be a terrible loss for both sides. Thus, customers should expect to see new fees accompanying the move in Supplier Offer Power to the right. The fundamental economics of the B4B proposition are compelling: Suppliers reduce the cost of technical complexity, and in their stead, new high-value services are offered. Although these services are costly, they yield much higher overall returns to the customer. There should be new money to spread around—that is, if customers are willing to change the way they do business.

The first change, as we just mentioned, is who does what. Most business customers have staffed up to operate and optimize the technology they own. They have hired system administrators, IT specialists, and production engineers—often lots of them. Now Level 3 suppliers will be able to leverage their new operating model to deliver many of the same roles at a far lower cost. But these savings will only be realized if the business customers can free themselves from some elements of their existing cost structure (see Figure 6.8). In order for one side to dial up its capabilities, the other side has to dial down.

Those are hard decisions to make. That may mean laying off employees or reassigning them. It might mean that the size, budget, and influence of some in-house departments will shrink. It may mean replacing current suppliers with whom you have a good relationship with new suppliers who can move you to the right along the Power Lines. These are hard decisions indeed. But if customer departments such as IT, production, or operations are to be fiscally responsible and deliver on the demand to increase the ROI from the company’s technology spend, these are decisions that must be made.

FIGURE 6.8 Suppliers Play Roles Once Seen as the Job of Internal Staff

Another thing that will surely change is the supplier selection process itself. The old RFP criteria that customers used when selecting Level 1 and Level 2 suppliers are going to need a major overhaul. Throughout this book, we have discussed myriad new capabilities and roles that suppliers will offer. Most business customers will need to think quite differently about what the important attributes of a winning near-tech or high-tech supplier will look like. In addition, suppliers must start the new practice of qualifying customers. In an era of shared risk and consumption-based pricing, they need to ensure that a potential customer is actually capable of attaining the target volume outcome before they invest their resources and capabilities. This will be a whole new experience for customers, one they may not like at first. However, such a process could be massively productive in uncovering weaknesses and landmines that historically would not have been discovered until a project was on the brink of failure.

We also think customers will adopt new tactics on their journey to expensive global technology solutions. Rather than looking for a sole-source, enterprise-wide supplier at the outset, they may be inclined to try one or more pilot projects with one or more different suppliers. This notion of “land and expand” will become far more practical in the Level 3 XaaS world than it ever was in the world of on-premise, CapEx Level 2 operating models. We think this will become so common as to have a big impact on how suppliers and customers develop their partnerships.

These are just a few of the many customer implications of the ascendency of Level 3 and Level 4 suppliers over the next few years. The new bridges spanning the great divide could significantly change how suppliers and customers select and engage with each other. We are on the verge of something powerful. The changes will be worth it. But what are the first moves, and who makes them?

The Three Pivots

Earlier in the book, we talked about how the onus was on suppliers to make the first moves on the topic of data security. That is only fair. After all, they are the suppliers, not the customers. They have to earn the business, to demonstrate that they have the Tower of Power necessary to play seriously at Level 3 or 4. But we think there are three things that both suppliers and customers can start working on immediately.

Why do we call them the Three Pivots? Well, a pivot requires that something stays in place while something else moves. In a spreadsheet, a pivot table has a fixed body of data, but there are different ways to sort or add it. In the sport of basketball, when a player is not dribbling the ball, one foot must stay in place, but the other foot is free to move to a new position. This is the idea that we think both customers and suppliers must keep in mind as they begin their transformations to Level 3 and Level 4 partnerships. They can’t just run away from everything that exists today and start all over. Instead, they need to keep some things still while other things move. That is exactly what high-tech and near-tech markets need to be doing right now in order to begin their transformations.

The Three Pivots are:

•land-and-expand selling.

•adoption services.

•the data handshake.

While there are hundreds of transformational activities that suppliers and their customers could act on, the Three Pivots are probably the most important. They are activities that most NewMo suppliers have already begun working on. They are activities that, if not begun, threaten to make Level 2 suppliers look out of date. Finally, they are activities that absolutely will not succeed without the support and engagement of customers.

So, let’s get to work.