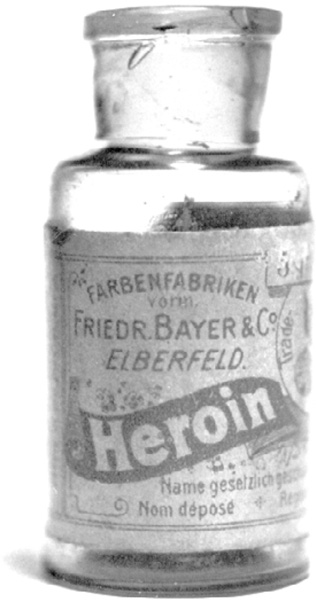

Bayer heroin, c. 1900

Thanks mostly to the joys of shooting morphine, the United States in 1900 was estimated to have around 300,000 opiate addicts out of a total population of about seventy-six million, or about four addicts per thousand people. That means that in rough terms the rate of opiate addiction in America in 1900 was about the same as it was almost a century later, in the 1990s. In the past twenty years, of course, the rate of opioid addiction has shot up considerably. But many things were similar about the epidemic then and now. Then, as now, overdoses were killing thousands every year. Then, as now, everyone knew about the dark side of opium-derived drugs; everyone was reading news reports about the suicides and overdoses, the addiction and despair. And then, as now, no one quite knew what to do.

The main difference was that in 1900 opium-and morphine-laced drugs were available without a prescription. You could buy a dose of morphine at the corner drugstore.

But in the face of an addiction epidemic, a growing number of physicians, lawmakers, and social activists demanded that something be done to control the drugs. Total prohibition was not an option. Morphine was too valuable a medicine to ban entirely. But pressure grew for some kind of regulation.

While politicians argued about the legalities, scientists searched for something that would make the legalities meaningless. They wanted to find some new form of morphine that would have all of its painkilling power with none of its addictive risks. This magic medicine became the holy grail for drug researchers. Chemists began to study and change the morphine molecule, adding a side chain here, taking an atom or two away there, continuing the quest.

Every year chemists were getting better at what they did. The decades around 1900 were a golden age for chemistry, especially the subfield organic chemistry, the science of carbon-containing molecules like proteins, sugars, and fats—the molecules of life. These wizardly chemists seemed able to make almost any variation they wanted of almost any molecule in the body. They were learning how sugars are built, how foods are digested, how enzymes (the catalysts of biochemical reactions) work. They could shape molecules the way other people shape wood or metal. They could, it seemed, do anything.

But morphine resisted them. A typical failure happened in London in 1874, when a chemist tried adding a little side chain of atoms (an acetyl group) to morphine. This British researcher was one of many looking for that magic combination, and he thought he might be on to something promising. But when he tested his new chemical on animals, he came up with nothing.

Animal testing is an imperfect art. Lab rats, dogs, mice, guinea pigs, and rabbits have different metabolic systems than one another and that of humans, and so can react differently to new drugs. Plus—and this is very important—they can’t tell researchers how they’re feeling. Without knowing that, scientists have to come up with other ways of testing the animal’s reactions, trying to gauge the effects of drugs. Sometimes that’s easy—like seeing if an infection has cleared up. Sometimes it’s hard—like trying to measure the depth of depression in a rat.

Still, testing in animals remains one of the best ways researchers have to see if a new drug is poisonous, and to get at least a rough idea of its effects.

And so the London chemist in the 1870s gave his new acetylated morphine to animals. And nothing happened. It wasn’t poisonous when given in low amounts, but neither did it seem to be doing anything. It was a dead end, like most experiments. He wrote a short journal article about his results and went on to other things.

There it sat for two decades, during which platoons of other chemists continued working with morphine and the other major alkaloids—opium, codeine, and thebaine—taking them apart and piecing them back together with new atoms, creating hundreds of variations. And the grail failed to appear. The greatest organic chemists in the world, with all their advanced techniques, were getting nowhere.

That is, until just before the turn of the century. In the late 1890s, a dye-making firm in Germany decided to branch out. The Bayer company already had a stable of chemists whose job it was to turn coal tar (a waste product from making the gas that lit the Gaslight Era) into valuable chemicals like synthetic dyes. After Queen Victoria wore a mauve dress in 1862—a new shade made in a chemist’s lab—synthetic fabric dyes became a fad. Chemists started making a dazzling rainbow of new colors out of coal tar. Everybody in the dye game made money. But by the 1890s there were a lot of dye makers in Germany. The market was getting crowded.

So Bayer turned its chemists to the task of exploring another moneymaking line of chemical products: drugs. Inspired by the success of synthetic drugs like chloral hydrate (see this page), Bayer was determined to find more laboratory chemicals that could treat more diseases. The decision to move into drug-making was somewhat risky, but the rewards were potentially huge. The basic approach was the same for dyes and drugs: start with a common, relatively cheap natural substance (like coal for dyes, or opium for drugs), then allow organic chemists to alter the molecules in it until they turned them into something much more valuable. These newly created chemicals could then be patented and sold at a huge markup.

Soon after Bayer made the move into drugs, one of the company’s young chemists, Felix Hoffmann, struck gold twice. In the summer of 1897, he, too, started attaching acetyl groups to molecules. When he did it to a substance isolated from willow bark (the bark had long been given as an herbal medicine to patients with fevers), he created a new and effective fever reducer and mild painkiller that his company named Bayer Aspirin. And when he linked the same acetyl side chain to morphine, just like the London chemist had done decades earlier, he came up with the exact same molecule that the British had already tested and discarded. But Bayer stuck with it, testing Hoffmann’s acetylated morphine on more kinds of animals and interpreting the results more positively. They even rounded up a few young volunteers from the factory to test the drug on humans.

And the results were amazing. The German workers reported feeling really good after they took Hoffmann’s new drug. No, better than good, great: They felt happy, resolute, confident, heroic.

That was enough for Bayer to give out some of the experimental drug to two Berlin physicians, with instructions to try it with any patients they thought appropriate. The results were, again, impressive. Bayer’s acetylated morphine could ease pain, like morphine, and also turned out to be great at quieting coughs and managing sore throats. Tuberculosis patients given the new drug stopped hacking up blood. It had the pleasant side effect of raising spirits and reviving a sense of hope. No serious complications or side effects were noted.

That was all Bayer needed to hear. Enthused, the company made plans to put their new wonder drug on the market. But first they had to come up with a catchy trade name. The company considered calling it Wünderlich, the wonder drug. But in the end they decided on a riff of the German word heroisch, or “heroic.” Their new drug would be called Bayer Heroin.

Their tests showed that it was up to five times stronger than morphine and far less habit-forming, ten times more effective than codeine and far less toxic. It looked to Bayer experts like Heroin had an additional, unusual ability to open up airways in the body, so they started selling it primarily for coughs and breathing disorders, and secondarily as a cure for morphine addiction. Patients happily gave up their morphine for Heroin. They loved the new drug. So did doctors. Use spread. For $1.50 users around the turn of the century could put in an order from a Sears-Roebuck catalog and receive back a syringe, two needles, and two vials of Bayer Heroin, all in a handsome carrying case. Early scientific presentations touting the success of Bayer Heroin spurred standing ovations.

Bayer heroin, c. 1900

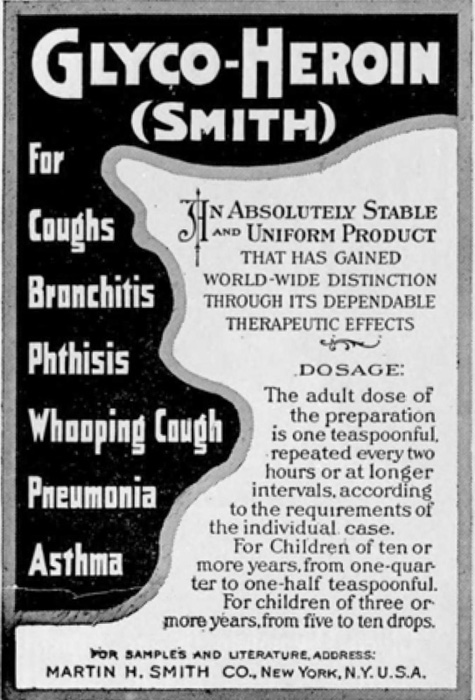

But there was a problem. Because Bayer hadn’t discovered Heroin—the molecule originally had been made by that London chemist two decades earlier—the drug’s patent protection was weak, and other drug companies soon started making it. It lost the capital H used by Bayer and entered the wider world of drug-making and drug-hawking. Heroin-laced cough lozenges sold by the millions. Elixirs containing heroin were said to be safe for all ages, even infants. The drug was added to one over-the-counter cure after another, touted as a treatment for everything from diabetes and high blood pressure to hiccups and nymphomania (the nymphomania application, at least, had some basis in reality: Heroin, as any addict can tell you, drains the sex drive). In 1906, the American Medical Association approved heroin for general use, especially as a substitute for morphine.

Advertisement from 1914 for cough medicine containing heroin

Without the ability to patent its new miracle drug, Bayer soon moved away from heroin, and the company stopped making it entirely around 1910. But by then Bayer Aspirin’s massive global success was bringing in so much money that the company redoubled its focus on drugs. Dyes were put on a back burner, and pharmaceuticals moved to the front.

As heroin spread, physicians quickly figured out a couple of not-so-great things about the new drug. The first was that Bayer’s idea about it being good for the respiratory system was wrong—the drug did nothing special to open up airways. The second was that heroin was no answer for morphine addiction, any more than morphine had been for opium addiction. Instead, the new drug was found to be very, very addictive. It was the story of morphine all over again: Physicians began seeing more heroin addicts in their offices, and newspapers began running more reports of overdoses. Heroin differed in some ways from morphine, but not in the important ways. Each refinement of opium, each new version, seemed only to increase strength without reducing addiction. Opium and all its children—morphine, heroin, and today’s newer synthetic opioids alike—are all bewitching drugs, very good at easing pain, good at making users feel great (at least at first), easy to start, and, after a period of habituation, extremely hard to stop.

The term “drug addict” first began showing up in medical texts around 1900, at the same time the phrase “drug fiend” began seeing wider use in newspapers. (And another note about terms: “opiates” are drugs derived directly from opium, like morphine and heroin, while “opioids” is a broader term that includes today’s synthetic painkillers as well.)

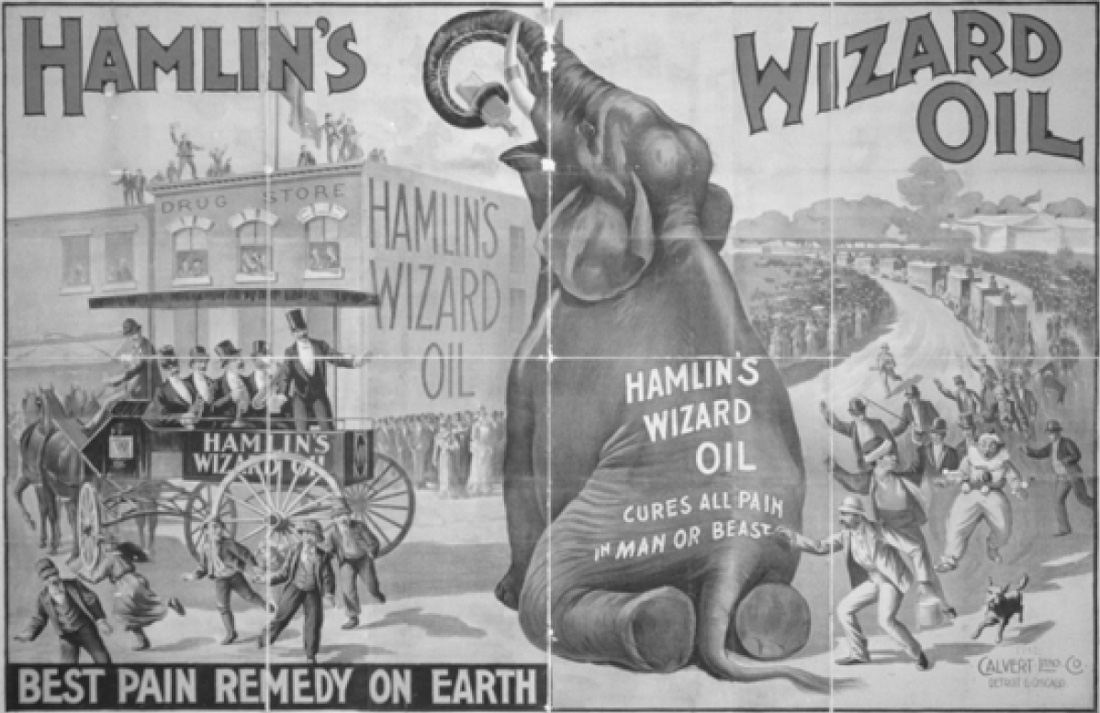

The problem went beyond opiates. There was also legal cocaine (used widely in hospitals and dentists’ offices and, very briefly, as a minor ingredient in Coca-Cola); legal cannabis (a not uncommon ingredient in patent medicines); and legal anesthetics like ether and nitrous oxide (laughing gas). There was chloral hydrate and Bayer’s popular new barbiturate sleeping pills, both for sleeping. Every year a new raft of drugs showed up, with extravagant claims and little regulation.

In the years just before World War I, America woke up to the fact that it had a drug problem. Muckraking journalists began exposing the dangers of drugs, from patent medicines to chemical-laced cosmetics. Drugs were tearing families apart, spurring addicted women to prostitution and addicted men to robbery, bringing down financial ruin and personal disgrace. The antidrug movement gathered up medical experts and ministers, housewives and newspaper editors, do-gooder politicians and hard-nosed police alike to form a broader social movement for drug control. Part of it grew out of the Bible-fueled temperance movement against alcohol. Part of it was rooted in the reform-minded Progressive politics of the day. A mixture of moralism and medicine with a dash of racism—Look at those Chinese opium dens, marijuana-dazed Mexicans, and drug-crazed Negroes—propelled the antidrug campaigns.

It all came to a head during the years when Theodore Roosevelt was president. TR was a Progressive, dedicated to clean government and decisive action. He, like many people, felt that patent medicine makers were bilking the public with overblown claims for secret recipes, too many of which contained opium, heroin, cocaine, or booze. His administration pushed for passage of the nation’s first federal drug-control legislation, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 (over the vigorous opposition of patent-medicine lobbyists).

A patent medicine advertisement, c. 1890. Calvert Lithographing Co. Lithographer. Hamlin’s Wizard Oil. Courtesy: Library of Congress

He got his legislation. Most of the emphasis was on ensuring untainted food, while the drug part of the act was relatively toothless, little more than a set of regulations ensuring more accurate ads for patent medicines. But TR was just getting started. He took on the China opium trade, helping initiate the first International Opium Conference in Shanghai in 1909 and strongly favoring a second in the Hague two years later. In 1909 the United States passed a federal Opium Exclusion Act, an important step in criminalizing the drug, then signed the first international drug control treaty in 1912.

It was all capped by the nation’s first significant antidrug law, the Harrison Act of 1914, which regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of narcotics. What was a narcotic? Doctors used the term to describe drugs that produced sleep and stupor. But to police and legislators, narcotics were heavy drugs, ones that caused addiction. So the Harrison Act included cocaine by name, despite the fact that it revs users up instead of putting them to sleep. Oddly, the first version did not include heroin by name (although it was added to the legislation years later). Mostly, the Harrison Act was targeted at opium and morphine. For the first time, all U.S. physicians and druggists had to register, pay a fee, and keep a record of every transaction involving opium, morphine, or cocaine. The act marked a watershed in the control of narcotics in the United States.

Patent medicine makers fought it, arguing that this was an infringement of Americans’ long-standing right to decide for themselves what medicines to take. But they couldn’t stop the regulation. After the Harrison Act passed, honest doctors, faced with having to keep records of every narcotic prescription, prescribed less. Druggists became far more cautious. Patients were more likely to think twice. Opium shipments into the United States plummeted from 42,000 tons in 1906 to 8,000 tons in 1934.

The stage was set for a question that is still being asked: Is drug addiction a moral failing or a disease? In other words, should drug addicts be treated as criminals or patients?

The Harrison Act sharpened the focus on this question, placing the government squarely on the side of criminalization. This left many physicians in a tough spot. A doctor could still prescribe and administer narcotics, but, the act read, “only in the course of his [sic] professional practice.” Treating a patient’s pain with morphine after surgery, for instance, was okay.

But what about treating a patient for morphine addiction? Was that allowable? Before the act, most doctors viewed drug addiction as a medical problem; their job was to cure it. They prescribed morphine or heroin to their addicted patients to help control the quality and lower the amount, gradually easing addicts off the drugs. But Harrison viewed narcotics addiction as a crime, not a disease, so using narcotics to treat it was not a legitimate professional practice. Therefore doctors who prescribed narcotics to addicts were themselves criminals. Bizarre but true: Within a few years of the Harrison Act, around 25,000 physicians were arraigned on narcotics charges; of those, some 3,000 were convicted and sent to jail.

Unable to get a legal dose, addicts, as always, turned to the streets. After the Harrison Act, the illicit drug market bloomed. It was the start of a long romance between crime and drugs. By 1930, about a third of all convicts serving time in U.S. prisons were there because they’d been indicted under the act.

The Harrison Act was reinterpreted in 1925 to allow some medical prescriptions for narcotics addicts, but by then the pattern had been set: Addiction to narcotics, in the eyes of the government, was a criminal activity. Opium addicts were no longer habitués, morphine addicts were no longer neighbors with a deplorable habit. Now they were junkies and hopheads driven mad by their yen for the drug (all terms that linked opium to the Chinese). The specter of Fu Manchu arose, along with a thousand other pulp images of leering Chinese men threatening innocent white women in smoky rooms. It was a cruel twist of history. British merchants pushing Indian opium had made addicts of millions of Chinese. Now the Chinese were the bad guys, while the heroes, like Fu Manchu’s archenemy Nayland Smith, were British.

Ironically, one of the biggest beneficiaries of the Harrison Act was heroin. After Bayer stopped marketing it and legal availability shrank to nothing after 1914, heroin quickly became a street drug. It was relatively easy for criminals to make from morphine, or even from raw opium. And it was easier to hide and move around than liquid morphine. Heroin was made as a powder and was so concentrated that a few bricks were worth a fortune on the street. It was so powerful that it could be cut with other drugs or inert filler and sold to users in small, easy-to-hide packets. There were reports of “sniffing parties” where young people snorted heroin. There were stories of pathetic addicts dying in the back alleys of small towns. By the time it was added by name to the Harrison Act in 1924, it was already an underground fashion among the young sheiks and flappers of the Jazz Age, especially popular in big cities like New York. And in Hollywood, where a 1920s dealer known as The Count became famous for putting heroin in peanut shells and selling it by the bag. One of his clients was Wallace Reid, famed as the world’s most perfect lover and the handsomest man in pictures. As Reid’s heroin addiction grew, his career hit the skids; he ended up dying in a sanatorium in 1923.

While the United States criminalized drugs, Great Britain took another path. In 1926 a select committee in London decided that addicts were medical patients, not criminals, an attitude that has shaped the practice of British medicine ever since. In the 1950s, for instance, dying patients in Britain could still get a Brompton cocktail, a potent mix of morphine, cocaine, cannabis, chloroform, gin, flavorings, and sweeteners. “It brings optimism where there is no hope, a certainty of recovery while death comes nearer,” wrote one physician.

You might not be able to get a Brompton cocktail anymore, but Britain remains the only nation on earth where it is legal for a physician to prescribe heroin (although this is done rarely, usually for pain control in end-of-life care). And heroin addiction rates in Britain today are a fraction of what they are in the States.

Heroin is part natural—made from morphine, one of the naturally occurring alkaloids in opium—and part synthetic, the result of tinkering with the natural molecule, adding and subtracting atoms. It’s what’s called a “semisynthetic” opiate drug.

After 1900, many labs were doing what Bayer did to create its new semisynthetic heroin. They started with the alkaloids in opium—morphine, codeine, thebaine, and others—and tried to find out what made them work. These are not easy molecules to study. Morphine, for instance, has a complicated structure with five rings of atoms tied together. Some labs tried to strip it down to its smallest active component, breaking it into fragments, looking for the heart of the molecule. They then played with those fragments, substituting different atoms and adding side chains, making them into semisynthetics.

Around World War I, chemists searching for that holy grail of a nonaddictive painkiller made and tested hundreds of semisynthetic variations, few of which reached the market. But some of them were successful. Codeine was tweaked in 1920 to make hydrocodone (which, when mixed with acetaminophen, makes today’s Vicodin). Doing something similar with morphine resulted in hydromorphone, patented in 1924 and still used today under the brand name Dilaudid. In 1916 chemists refashioned codeine to make oxycodone, a very strong semisynthetic known for being the key ingredient in Percocet (and now infamous in a potent time-release formulation under the name Oxycontin). These are all semisynthetic opiates, they’re all effective painkillers, they all can make users a little spacey, and they’re all addictive.

Others were found that were stunningly strong. In 1960, for example, a Scottish drug team was cranking out variation after variation of thebaine, another of the natural alkaloids found in opium. One day a worker in the lab used a glass rod sitting on a lab bench to stir some cups of tea. A few minutes after drinking it several scientists fell to the floor, unconscious. The rod had been contaminated with one of the new molecules they’d been working on. It turned out to be a super semisynthetic, thousands of times more powerful than morphine. Under the trade name Immobilon, it found use in darts to knockout elephants and rhinos.

The semisynthetic Oxycontin (aka oxy, cotton, kickers, beans, and hillbilly heroin) has made a lot of headlines as today’s opiate du jour. The United States consumes about 80 percent of the world’s supply. It has succeeded in moving opiate addiction from inner-city streets to middle-American small towns. It is everywhere, taken by just about every kind of citizen, but it’s especially popular among poor, white, rural Americans. Overdoses (usually when taken with alcohol or other opioids) and oxy-assisted suicides are a major reason why the average lifespan of this group is declining—a downward shift that goes against everything medicine has done for the past century.

There’s plenty of information out there about why oxy became so popular; all you have to do is read the news. But at the heart of it is the same simple fact that made China into a nation of addicts 170 years ago, made morphine a national scandal in the 1880s, and made heroin the most infamous drug of the 1950s. It’s an opiate. And every opiate, without exception, is highly addictive.

After decades of work and thousands of failures, the semisynthetic path never did lead to that magic, nonaddictive molecule. So researchers took the next step, looking for a different approach: They sought a class of medicines not based on morphine or codeine or any part of opium at all, but something completely new. Something with an entirely new structure. Something completely synthetic.

Remarkably, they found some. The most powerful of these new synthetics—drugs like fentanyl and carfentanil—are not just as good as morphine at treating pain; they can be hundreds of times better. But they are also, and without exception, highly addictive.

The story of the synthetics, so important to understanding our current epidemic of opioid abuse and overdose, is found in chapter 8 (this page).