![]()

The Bel Canto Singing Style

INTRODUCTION

Of the various national styles of singing in the Baroque era, the Italian style was the mainstream. There has been a more or less unbroken tradition of bel canto singing ever since Giulio Caccini wrote about it in his Le nuove musiche (1602). The classical bel canto style crystallized in the late seventeenth century, when musical considerations triumphed over the text-dominated style of the early part of the century. By that time Italian opera had become something of a commodity, and Italian signers were in demand throughout Europe. Unfortunately, for about the last three quarters of the century there are essentially no Italian treatises on singing. There are, to be sure, numerous treatises from German writers of this period,1 but while they were enthusiastic admirers of the Italian style, few of them had direct association with bel canto singers. Pier Francesco Tosi, a castrato singer and actor of some note, was, however, thoroughly conversant with the bel canto style. His Opinioni de’ cantori antichi, e moderni was published in 1723, chronologically beyond the limits of this guide, but by that time Tosi was well into his seventies. His ideas about singing were formed during the closing decades of the seventeenth century, when he was at the height of his career. Moreover, the title of the book clearly indicates Tosi's awareness of the “ancient”–by which he means the style of his own heyday as a singer and the “modern” styles of singing, and it is clearly the former that he prefers.

Tosi's treatise was translated into English by J. E. Galliard (1743) and into German by J. F. Agricola (1757).2 The latter's copious annotations are often quite illuminating, even for seventeenth-century practice, in spite of their late date.

Articulation

Articulation is perhaps the key element that distinguishes early Baroque from modern vocal style. The incredibly facile technique of the finest Italian singers of the era can be seen in the florid written-out divisions that survive. These singers employed a rapid glottal articulation known as the “disposition of the voice” (disposizione della voce). Rather like a high laugh or giggle, with the air striking the soft palate, this technique facilitated rapid movement of the voice, though it is frowned on in modern vocal pedagogy. Later in the Baroque, when singers had to fill large performing spaces such as opera houses, this style of articulation fell out of favor. Glottal articulation is quite effective in intimate performance venues, but it is virtually inaudible in the far reaches of a large hall.

By the late seventeenth century, according to Tosi, there were two principal manners of articulating divisions–the battuto (detached, which replaced the glottal style) and the scivolato (slurred). Regarding the former, Agricola offers an interesting explanation:

When practicing, imagine that the vocal sound of the division is gently repeated with each note; for example, one must pronounce as many a's in rapid succession as there are notes in the division–just as with a stringed instrument, where a short bow stroke belongs to each note of the division; and in the traverse flute and some other wind instruments [where] each note receives its own gentle impetus by the correct tongue stroke, whether single or double.3

For the slurred divisions Agricola suggests that the singer pronounce only one vowel, which is not rearticulated, and over which the entire division is sung.4 For Tosi the battuto style of articulation is far more common than the scivolato: he allows only a descending or ascending four-note group to be slurred.5

In addition to the two common types of articulation for divisions, Tosi discusses two other special types. The first of these is the sgagateata (lit., cackling), a pejorative term used in Italy to describe the glottal articulation.6 It was regarded as a fault because it is usually too feeble to be heard adequately. Tosi further disparages glottal technique for the reiteration of one tone. He writes,

What would he [the good teacher] say about those who have invented the astounding trick of singing like crickets? Who could ever have dreamed that it would become fashionable to take ten or twelve consecutive eighth notes and break them up by a certain shaking of the voice?…He will have even greater reason, however, to abhor the invention by which one sings in a laughing manner or sings in the manner of hens that have just laid an egg.7

Singing Instruction

The quick glottal articulation, disposizione di voce, was an important element of singing instruction in the early part of the seventeenth century. It had not entirely disappeared by the last decades of the century, though Tosi disparages it. Agility, however, was extremely important. The trill was stressed as not only the hallmark of agility, but also as the foundation of agility; the fast notes must be practiced in order to make the trill more even. This was contrasted with long notes, called fermar la voce by Tosi. Italian singing teachers probably started with long notes as their first exercise.

Tosi rebukes the many singers of his day who, in their rejection of “old-fashioned” style, neglect to practice the messa di voce, a crescendo-decrescendo over a long note. He recommends that it be used sparingly and only on a bright vowel. Messa di voce was an important aspect of singing instruction, and when Roger North suggested that one begin on the viol by playing long-held notes with a messa di voce, he probably was imitating singing instruction.

Tosi thus specifies two types of sustaining of the voice. The function of the fermar is to steady the voice on a long, sustained note without crescendo and make it capable of singing sustained notes evenly and without vibrato, whereas the messa di voce entails a crescendo-decrescendo and often the introduction of vibrato at the highest point of the crescendo.8

Tosi's observations for music students may be compared with descriptions of training regimens of the castratos in the papal schools and in Naples. Common to all are (1) emphasis on the practice of agility (ability to execute fast passages), (2) emphasis on exercises for long, sustained notes, (3) the study of composition, (4) work in front of the mirror, and (5) the study of literature and languages.

At the Papal Chapel school in Rome, students were required to devote themselves during the first hour of the morning to the practice of difficult divisions. A second hour was spent practicing the trill, and a third was devoted to developing correct and clear intonation—all this in the presence of the master and in front of a mirror, in order to watch the position of the tongue and the mouth. The morning regimen ended with two hours devoted to the study of expression, taste, and literature. In the afternoon, one half hour was devoted to the theory of sound, another half hour to simple counterpoint, and an hour to composition. The remaining time was spent practicing the keyboard and composing motets or psalms.9

Diction

Tosi has a great deal to say about diction, and much of it pertains to the singing of divisions:

Every teacher knows that the divisions sound unpleasant on the third and the fifth vowels (the i or the u).10 But not everyone knows that, in good schools, they are not permitted even on the e and o11 if these two vowels are pronounced closed….Even more ridiculous is when a singer articulates too loudly and with such forceful aspiration that, for example, when we should hear a division on the a, he seems to be saying ga ga ga. This applies also to the other vowels.12

Some earlier Italian writers, such as Camillo Maffei, said that the u vowel sounded like howling, especially since the Italian word for howling is ululando. The i was rejected because it was thought to produce the sounds made by small animals.13 Agricola is critical of basses who, when singing divisions, “put an h in front of every note, which they then aspirate with such force that, besides producing an unpleasant sound, it causes them unnecessarily to expend so much air that they are forced to breathe almost every half measure.14

ORNAMENTATION

Divisions

Tosi indicates that ornaments should be performed with proper concern for the affect of the text and that attention be paid to the preferred vowels (a and o) and to the type of articulation—slurred in the pathetic arias and detached in the lively ones. While sounding easy, the ornamentation should, in fact, really be difficult, though it should never sound studied. Dynamic colors are important, and the use of the piano in the pathetic adagio is especially effective, as is also a type of “terrace dynamics” (use of piano and forte without intermediate shadings) in the allegro. Choosing the appropriate place for an ornament is important; therefore, the singer should take care not to overcrowd it. It should never be repeated in the same theater because the connoisseurs would take notice. Tosi advises the singer to practice divisions that contain leaps after learning those that move by step.15

Tosi uses the following five adjectives to describe the “whole beauty” of divisions: perfettamente intonato, battuto, eguale, rotto, and veloce.16 The first and last adjectives, “perfectly in tune” and “fast,” need no explanation. The term battuto, discussed above under the section articulation, refers to the vocal technique involving the motion of the entire larynx that was essential to the basic agility of the voice. Eguale means that the notes within the division should be “equal” in volume. Rotto (lit., broken) means “distinct.” Simply put, battuto refers to the specific technique the singer is to use, while rotto refers to the effect perceived by the listener.

Cercar la Nota

Tosi advises the teacher to “teach his students to sing all of the leaps within the scale with perfectly pure intonation, confidently, and skillfully.”17 Agricola warns of a fault noticed in many Italian singers, whereby

with a leap, even a small one, they sing, before they get to the higher note, one or even two or three lower notes. These are indistinct and may even be sung with a sharp aspiration. They even introduce ad nauseum this cercar la nota (searching for the note) to interval leaps larger than a third—which was not common practice among the ancients.18

One of the first theorists to describe the cercar dalla nota is Giovanni Battista Bovicelli, who speaks of it as “beginning from the third or fourth below the main note depending on the harmony of the other parts.”19 Christoph Bernhard specifies that it is the “note directly below the initial note,” employed either at the beginning or during the course of a phrase and performed in a gliding manner very imperceptibly to the initial note.20 Besides its function as an ornament, the cercar della nota is also a vocal technique used in the modern era to enable the singer to reach a high note more easily.

Messa di Voce, Messa di Voce Crescente, and Strascino

We have observed that the messa di voce was a critical element of a singer's training. First seen merely as a device or ornament, the messa di voce is obviously intended by Caccini when he speaks of il crescere e scemare della voce (the crescendo and decrescendo of the voice) as one single grace, which is performed on a whole note.21 One of the first writers to use the term, Tosi defines the messa di voce as “beginning the tone very gently and softly and letting it swell little by little to the loudest forte and thereafter letting it recede with the same artistry from loud to soft.”22

A special effect that can be used instead of the appoggiatura in making an ascent is the messa di voce crescente. The adjective crescente simply means “rising.” The effect is applied to a long-held note with a swell that gradually rises by a semitone.23

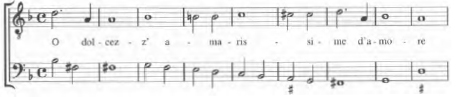

The strascino, or “drag,” was like a glissando or slide. Tosi uses the term not only to denote an extremely slurred manner of singing, but also to indicate a special ornament consisting of a slowly descending glissando scalar passage, considered especially effective in the pathetic style. He also says it involves an alternation of loud and soft, and it also seems to entail a tempo rubato over a steady bass.24 The drag is distinguished from the messa di voce crescente primarily in that the latter encompasses only the interval of a rising half step, whereas the drag can ascend or descend and may have a wider compass. It is found in the works of Claudio Monteverdi and Sigismondo d'India, where on very affective words one sometimes finds an ascent of a chromatic half step, accompanied by a slur (see Example 2.1).

Example 2.1. Sigismondo d'India, O dolcezz'amarissime d'amore (1609).

The Appoggiatura

Tosi devotes an entire chapter to the appoggiatura and recommends practicing this ornament in scalar passages, with an appoggiatura on each step of the scale. Agricola, strongly favoring on-beat execution of the appoggiatura, is careful to stress that the location of the syllable or word of the text underlay should occur on the appoggiatura itself rather than on the main note under which it is habitually written: “when a syllable falls on a main note, which itself is notated with an appoggiatura or any other ornament, then it [the syllable] must be pronounced on the appoggiatura.”25 Agricola's rule referring to the on-beat performance of the appoggiatura must be understood in the context of earlier Baroque practice, in which the phrase anticipatione della syllaba referred to a situation in which an appoggiatura or a one-note grace similar to it actually preceded the beat and bore the syllable.26

The Trill

For Tosi the “perfect” trill is eguale (lit., equal), battuto (lit., beaten),27 granito (lit., distinct), facile (lit., flexible), and moderamente veloce (lit., moderately quick). Some of these terms have already been encountered in relation to divisions. Eguale refers to the volume level of the two notes in relation to each other. When the two notes of the trill are not sounded equally, the resultant defective trill is often described as “lame.”

Battuto refers to a specific vocal technique (essential to the trill) that involves the up-and-down movement of the larynx—that “light motion of the throat” that occurs simultaneously with the “sustaining of the breath in executing the trill. When this “beating” movement of the larynx is not present or cannot be maintained, the trill of two notes collapses into a smaller interval or makes a bleating sound on one note alone; conversely, the larger the interval of the trill, the bigger the movement must be. Various Italian writers, including Tosi, use either or both of the terms caprino or cavallino to describe this sort of trill, in which the intended interval (major or minor second) cannot be maintained and which collapses unintentionally into a single pitch (or an interval smaller than a half step).28

When the interval of the trill is smaller than a half step, or when the two tones of which it consists are beaten with unequal speed and strength, or quiveringly, the trill sounds like the bleating of a goat. The precise place for production of a good trill is at the opening of the head of the windpipe (larynx). The movement can be felt from the outside when the fingers are placed there. If no movement or beating is felt, this is a sure indication that one is bleating out the trill only by means of the vibration of air on the palate.29

An insufficiently open trill might also yield the comic effect with which the following Venetian poem described the trill of Giuseppe Pistocchi, the famous castrato and voice teacher:30

Pistocco col fa un trill’ se puto equagliare

A quell rumor che’ é solito de fare

Quande se scossa un gran sacco di nose

(What sound did the trill of the great Pistocco make?

The sound of a sack of nuts when given a shake.)

Translation by Lawrence Rosenwald

Example 2.2. Tosi's trills (as realized by Agricola): (a) trillo maggiore; (b) trillo mi-nore; (c) mezzotrillo; (d) trillo raddoppiato; (e) trillo raddoppiato; (f) trillo mordente.

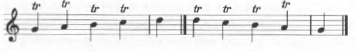

The eight types of trills that Tosi enumerates are the trillo maggiore,31 (trill of a whole step; Example. 2.2a); the trillo minore (trill of a half step; Example. 2.2b); the mezzotrillo (short and fast trill; Example. 2.2c); the trillo cresciuto and the trillo calato (trilled slow glissandi—the first ascending and the second descending); the trillo lento (slow trill); the trillo raddoppiato32 (which involves inserting a few auxiliary tones in the middle of a longer trill; Examples. 2.2d and 2.2e); and the trillo mordente (a very short and fast trill that is effective in divisions and after an appoggiatura; Example. 2.2f).33 Of these, only the trillo cresciuto, the trillo calato, and the trillo lento were obsolete in Tosi's time; the rest were prominent in current performance practice. Also popular was the chain of trills, which places a trill on each note of a scale passages (Example 2.3).

Example 2.3. Chain of trills (Johann Friedrich Agricola).

Vibrato

There are several mechanisms in the human voice for producing vibrato. One of these occurs in the same manner as the trill, that is, by the up-and-down movement of the larynx in a manner less exaggerated than the trill. Vibrato was considered an inseparable feature of the human voice in the seventeenth century. It is very difficult, for example, for a singer to execute a messa di voce or crescendo totally without vibrato. An important clue regarding this phenomenon is the vox humana stop in Spanish and Italian organs, which was always a trembling stop, as early as the 1500s. Yet this does not necessarily mean that vibrato was constant. In the twentieth century a concept of singing as a string of “beautiful pearls” developed. This is very different from the seventeenth-century aesthetic, in which the finest singers could alter their technique and their sound in order to adapt to the musical or dramatic context. Singers today modify their technique so that the placement, color, and timbre of a note matches exactly the note before and after it, the textual or dramatic context notwithstanding. There are certain situations in which a seventeenth-century singer would have sung without vibrato—perhaps on a dissonance, a leading tone, in a messa di voce crescente (a glissando within a half step), or on a particularly expressive interval such as a tritone. While consistent vibrato can homogenize the sound on all notes of the singers range, it does not allow for a demonstration of harmonic intelligence and expressivity that a seventeenth-century singer would have demanded. The disposizione della voce—the ability to sing fast notes in a glottal fashion—was a highly admired and necessary skill for the professional singer. This light, almost giggling technique, audible in the more intimate performing spaces of the seventeenth century, surely contributed to a softer volume and to a faster vibrato, since coloratura speed and vibrato speed are interrelated.

Rubato

Tosi, one of the first writers to discuss tempo rubato, mentions two types. In the first, time that is lost is later regained, while in the second, that which is gained is subsequently lost. It is difficult to accomplish, yet according to Tosi, its mastery is the mark of an outstanding performer, self-assured and expressive. He does not allow for the slowing down of a section with a subsequent return to the original tempo; the bass was generally expected to maintain a from beat. Tosi recommends the use of rubato in the varied repetition of the A section of a da capo aria and praises the virtuoso Pistocchi for his mastery of it.34 [For more on ornamentation, see Chapter 16 in this volume.]

REGISTRATION

For the Italians the two vocal registers, voce di testa (head voice) and voce di petto (chest voice), were to be united. The falsetto, which Tosi considered essential for beautiful singing, is apparently included with the former. For Tosi, the falsetto must be completely blended with the natural voice.35 In vocal music of virtually every style or era, it is essential that the singer be able to blend the two registers in the vicinity of the break—to be able to produce certain notes in either register and to move easily into the head voice as the musical line ascends. A singer who persists in using the heavier (or chest-voice) mechanics to produce his high notes will sound as though shouting—much like the “belting” of a Broadway singer. Seventeenth-century singers were encouraged to sing the high notes lightly, rather than blast them out in the chest register.

In literature on the human voice one sees a great deal of confusion even today regarding the matter of registration.36 In untrained voices a sharp “register break” can be easily identified by a change in tone quality and pitch as the voice moves up the scale, as for example in the contrast between the natural chest voice of the male and the head voice; there is a similar phenomenon in the female voice. Tosi says that one sometimes hears a female soprano singing entirely in chest voice.37

It is now commonly accepted that the vocal mechanism itself, not the head or chest, is the origin of the register.38 The terms “chest voice” and “head voice” are at best vague and metaphoric terms, coined in an age when it was thought that “the voice left the larynx and was ‘directed’ into these regions.”39 Early writers—extending as far back as Hieronymus of Moravia, and including more recent Italians such as Lodovico Zacconi, Caccini, and Tosi—distinguished the registers according to perception of sound. They made little or no mention of unifying the registers, which makes the voice sound more homogenous, corrects problems of intonation, and increases the singer's range—matters that became more and more essential with the changing styles in singing and the increased expectations of the voice. While an early seventeenth-century solo motet for soprano by Monteverdi or Luigi Rossi might have a range of an octave and a fifth (from c' to g”), contemporaries of Tosi such as Alessandro Stradella employed both higher and lower notes of the voice with some frequency. Still no mention is made of unifying the registers, although it became more and more essential in the bel canto style to blend the chest and head registers.40

The Appearance of the Singer and the Bocca Ridente

Tosi's directions regarding the singer's presence continue and refine the tradition expressed earlier in the seventeenth century by Italian writers and commentators on the subject. These include Francesco Durante, Marco da Gagliano, Girolamo Diruta, Pietro Cerone, Orazio Scaletta, Giovanni Battista Doni, and Ignazio Donati, whose caveats were directed largely against bodily and facial contortions and mannerisms that would detract from the singing.41 Tosi advocates a noble bearing (graceful posture) and an agreeable appearance; he insists on the standing position because it permits a freer use of the voice; further, he warns against bodily contortions and facial grimaces, which may be eliminated, he says, by periodic practice in front of a mirror. He recommends that if the sense of the words permit, the mouth should incline “more toward the sweetness of a smile than toward grave seriousness.”42 In short Tosi recommends the bocca ridente, which requires not only a “smiling mouth,” but also a positioning of the vocal apparatus critical to the bel canto style.

Mauro Uberti has called attention to a late fifteenth-century sculpture by Luca della Robbia in the Museo di Santa Maria del Fiore, a marble relief that depicts a group of singers whose mouths are open in such a way, he believes, as to produce an agile voice and make easy the ornamentation characteristic of early Italian singing.43 In studying the depiction of the sculpture on page 489 of Uberti's article, one can see that one of the singers has a very pleasant, relaxed, almost beatific expression on his face. The mouth, while not smiling, looks as if it is just ready to break into a smile. The heads of the others are lowered somewhat so that the smiling effect is not visible and their mouths are open wide enough but not too wide, apparently about the width of the little finger. A third, turned almost to profile, shows clearly, and even in a rather exaggerated way, the mouth position and facial expression that is common to all of the singing figures. The face is relaxed and natural looking; the lower jaw juts greatly forward. All the figures give the impression that the singing is done easily and without strain. These mouth positions are commonly found in early Italian representations of singing according to the author, who distinguishes between Italian vocal techniques prior to the early nineteenth century and Romantic techniques.

Uberti also compares the position of the larynx in the Romantic style with that of the early style:

In both the older and the more modern techniques the Adam's apple is tipped forward by muscles outside the larynx and thereby stretches the vocal cords. In the older techniques this is achieved by pulling forward the upper horns at the back of the Adam's apple…whereas in Romantic techniques the Adam's apple is pulled down…[and] the muscles attached to it from above react by tugging upward (just as they do when we yawn); the vocal cords join in the fray, as it were, and so reach that more vigorous contraction which is needed for the very powerful, stentorian high notes of modern operatic singing.44

In the bel canto technique, the mouth is opened only very moderately with the bocca ridente position. Uberti explains that the shield cartilage rocks or is tilted forward, moving on the fulcrum of its connection with the cricoid; the hyoid bone remains almost horizontal, the ligament between it and the thyroid or shield cartilage remaining flexible and relaxed; the muscle under the chin is short and relaxed; and the jaw is pressed moderately downward and somewhat forward. The singer has the sensation that “while the front wall of the throat is also drawn forward, the jaw itself remains free to move vertically.” Also, as Uberti explains,

for the less energetic mechanism of the older techniques, the forward tipping of the Adam's apple can be facilitated by using a rather forward position of the jaw in many Renaissance and Baroque depictions of singing…and to this day Neopolitans use it both in singing and in speaking.”45

CONCLUSION

For singers seeking advice on performance in the late seventeenth-century bel canto style today, there are many generalities but few specifics. We may be reasonably certain that singing then was more articulated, less loud, and had less vibrato, but we do not know, for example, precisely when bel canto singers did and did not use vibrato, nor exactly how wide its ambitus was. Theorists of the time did not have a vocabulary that could adequately describe vibrato—nor do we. Such is the limitation of treatises on musical performance in any period.

Obviously, we do not have recordings of the great singers of the late seventeenth century, but we do have recordings made in the early years of the twentieth century. Listening to singers such as Amelita Galli -Curci, Adelina Patti, and Jenny Lind (a student of Manuel García),46 one is struck by the light, facile tone production, not unlike that of early-music specialists today. And Patti's “tone sounds absolutely straight…except for occasional ornamental vibrato.”47 These early recordings postdate Tosi and Pistocchi by some two centuries, yet perhaps they offer us at least a shadow of the original bel canto style.

NOTES

1. See, for example, Bernhard, Singe-Kunst; Baumgarten, Rudimenta; Fuhrmann, Trichter; Gibelius, Bericht; Printz, Anweisung; Printz, Modulatoria; and Printz, Phrynis.

2. Galliard, Observations; Agricola, Anleitung. See also Agricola/Baird, Introduction, which contains an English translation of the latter, as well as extensive commentary. There is also a Dutch translation by J. A[lencon], Korte Aanmerkingen over de Zangkonst (Leyden, 1731).

3. Agricola, Anleitung: 124; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 151–152.

4. Agricola, Anleitung: 126; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 153.

5. Tosi, Opinioni: 31; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 153.

6. According to Agricola, Anleitung: 124; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 152–153.

7. Tosi, Opinioni: 106; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 152–153.

8. See Plank, Choral: 85 and footnote 9.

9. Bontempi, Storia, as reported in Haböck, Kastraten.

10. The vowel i as in English “beet”; u as in English “food.”

11. The vowel e as in English “hay”; o as in English “go.”

12. Tosi, Opinioni: ch. 4; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 157.

13. Maffei, Lettere, as translated in McClintock, Readings: 53.

14. Agricola, Anleitung: 126; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 157.

15. Tosi, Opinioni: 13; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 66.

16. Tosi, Opinioni: 30–31, 35. See Agricola, Anleitung: 123; (Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 151).

17. Tosi, Opinioni: 13; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 66.

18. Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 67.

19. Bovicelli, Regole: 11 (trans. Baird).

20. In Bernhard, Singe-Kunst, par. 20.

21. Hitchcock, “Vocal Ornamentation,” 394.

22. Agricola/Baird, Introduction, 84.

23. Tosi, Opinioni: 22. Tosi recommends this effect particularly where one ascends from a major to a minor semitone, in which case, he says, the appoggiatura is inappropriate. See Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 14.

24. Tosi, Opinioni: 114. See also Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 23, 86.

25. Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 93.

26. See Bernhard, Singe-Kunst.

27. If the trill were not beaten (battuto), it often resulted in the goat bleat, or caprino, described elsewhere in Tosi's chapter.

28. Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 18, 75, 126, 152. Caprino refers to the bleat of a goat, cavallino, to the whinny of a horse. They are treated as defects and are not identical with the repeated-note trillo found in the music of Monteverdi and Caccini. In describing the trillo, Christoph Bernhard specifies that “one should take great care not to change the quality of the voice in striking the trillo, lest a bleating sound result.” Bernhard, Singe-Kunst: 15.

29. Agricola, Anleitung: 105; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 18, 135.

30. Haböck, Kastraten: 335.

31. Tosi, Opinioni: ch. 8. See also Neumann, Ornamentation: 345–346. Neumann's interpretation of Tosi's description of this trill is part of his argument in favor of the domination of the main-note trill.

32. The extra notes that Agricola adds in his interpretation are at the beginning, and not in the middle as Tosi specifies. See Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 131.

33. Agricola interprets this trill as a mordent.

34. Tosi, Opinioni: 65, 82; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 193, 227.

35. Ibid.: 14; see Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 67–68.

36. For a sketch of the history of ideas regarding registration, including modern views, see Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 9–10.

37. Tosi, Opinioni: ch.1, pars. 18 and 21; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 68.

38. See New Grove: “Acoustics.”

39. Vennard, Singing: 66.

40. See Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 10.

41. See Duey, Bel Canto: 61–62.

42. Tosi, Opinioni: ch. 1, pars. 25–26; Agricola, Anleitung: 44; Agricola/Baird, Introduction: 82.

43. Uberti, Vocal: 486–487. For a digital representation, go to http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cantoria_di_luca_della_robbia_02.JPG

44. Ibid.: 487–488. In the Romantic technique, the vocal cords actively tense themselves continuously in an “isometric contraction”; they are less “nimble” than they are in the older method and thus “it takes a greater effort to negotiate passaggi” and other ornaments. Uberti (488) reminds us of the well-known fact that the tension of the vocal cords can also be manipulated in ways other than the tensing described above—for example, by lateral movement of the arytenoid cartilages, to which the vocal processes are attached. With this added adjustment, the self-contraction of the vocal cords can then be concentrated largely upon control of intonation. This adjustment, together with the earlier technique “for changing in the upper register,” causes the vocal cords generally to be increased in length and flexibility, “but they are still capable of contracting somewhat in order to colour the vocal timbre for fine nuances of expression. This technique must have been used by Renaissance camera singers, otherwise they could never have improvised the elaborate graces and passaggi prescribed in so many treatise of the day.”

45. Ibid.: 488.

46. Editor's note: sound clips of all of these singers can be found on YouTube.

47. Bernard D. Sherman in Baird, Beyond: 252n20.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Agricoloa, Anleitung; Agricola/Baird, Introduction; Baird, “Beyond”; Baumgarten, Rudimenta; Bernhard, Singe-Kunst; Bontempi, Storia; Bowman, “Castrati”; Caccini, Nuove musiche; Crüger, Kurtzer; Duey, Bel Canto; Fuhrmann, Musicalischer Trichter; Galliard, Observations; Gibelius, Kurtzer; Greenlee, Dispositione; Haböck, Gesangkunst; Haböck, Kastraten; Heriot, Castrati; McClintock, Readings; New Grove, “Acoustics”; Printz, Anweisung; Printz, Musica; Printz, Phyrnis; Reid, Bel Canto; Tosi, Opinioni; Uberti, “Vocal Techniques”; Vennard, Singing.

Suggested Listening

Musica Dolce. Julianne Baird, soprano. Dorian 90123.

Songs of Love and War: Italian Dramatic Songs of the 17th and 18th Centuries. Julianne

Baird, soprano, with Colin Tilney, harpsichord, and Myron Lutzke, violoncello. Dorian DOR 90104.