As far as we know, Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713) never set a word of text to music. A virtuoso violinist, he was the first European composer who enjoyed international recognition as a “great” exclusively on the strength of his finely wrought instrumental ensemble works. They circulated widely in print both during his lifetime and for almost a century after his death, providing countless other musicians with models for imitation. In his chosen domain of chamber and orchestral music for strings, he was the original “classic,” playing a major role in standardizing genres and practices, and setting instrumental music on an epoch-making path of ascendency. His sonatas and concertos may no longer be played much except by violin students, and yet their historical significance is tremendous, affecting European music of every sort.

Corelli’s career, based (after apprenticeship in Bologna) almost exclusively in Rome, outwardly paralleled Alessandro Scarlatti’s: service to Queen Christina and Cardinal Ottoboni, membership in the Arcadian Society, and so on. His main activities were leading orchestras, sometimes numbering one hundred musicians or more, in the richly endowed churches and cathedrals of the city, and appearing as soloist at “academies” (accademie), aristocratic house concerts.

For sacred venues Corelli perfected an existing Roman genre known as sonata da chiesa (church sonata). Such pieces could be variously scored: for solo violin and continuo, for two violins and continuo (hence “trio sonata,” albeit normally played by four instrumentalists), or amplified by a backup band known as the concerto grosso (“large ensemble”), which eventually lent its name to the genre itself. Thus when Corelli’s collected orchestral music was finally published in 1714 (a year after the composer’s death) by the Amsterdam printer Estienne Roger, the title page used the term concerto grosso in both senses at once: Concerti grossi con duoi violini e violoncello di concertino obligato e duoi altri violini, viola e basso di concerto grosso ad arbitrio, che si potranno radoppiare, opera sesta. Reissued the next year by the London house of John Walsh and John Hare, the title page was Englished thus: “Concerti grossi, being XII great concertos, or sonatas, for two violins and a violoncello: or for two violins more, a tenor, and a thorough-bass: which may be doubled at pleasure, being the sixth and last work of Arcangelo Corelli.” Church sonatas or concerti grossi were often played during Mass to accompany liturgical actions: typical placements were between the scripture readings (in place of the Gradual), at the collection (in place of the Offertory) or at Communion. At Vespers they could be played before Psalms in place of antiphons. A standardized outgrowth of the earlier canzona, the church sonata usually had four main sections in contrasting tempos (“movements”), cast in two slow–fast pairs resembling preludes and fugues such as organists were used to improvising. The more elaborate of these fugal movements was the one in the first pair; it was still occasionally labeled “canzona.”

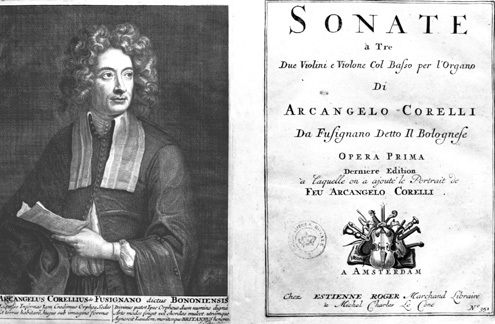

FIG. 5-1 Arcangelo Corelli, portrait by Hugh Howard, adapted as the frontispiece engraving for a late edition of Corelli’s trio sonatas, op. 1 (Amsterdam: Estienne Roger and Michel Charles Le Cène, ca. 1715).

For aristocratic salons, Corelli adopted another standard violinist’s genre, called sonata (or concerto) da camera (chamber sonata or concerto). This was essentially a dance suite, which Corelli adapted to the prevailing four-movement format (a “preludio” and three dances or connecting movements). Between 1681 and 1694 Corelli published forty-eight trio sonatas in four collections of twelve, alternating church sonatas (opp. 1 and 3) and chamber sonatas (opp. 2 and 4).

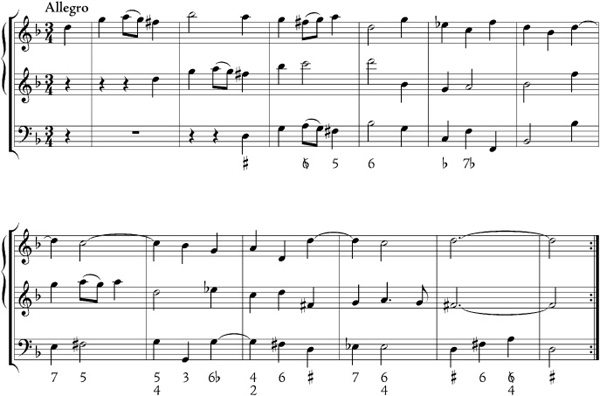

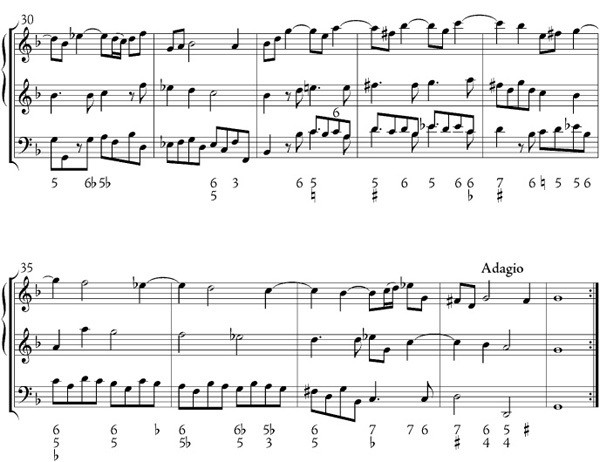

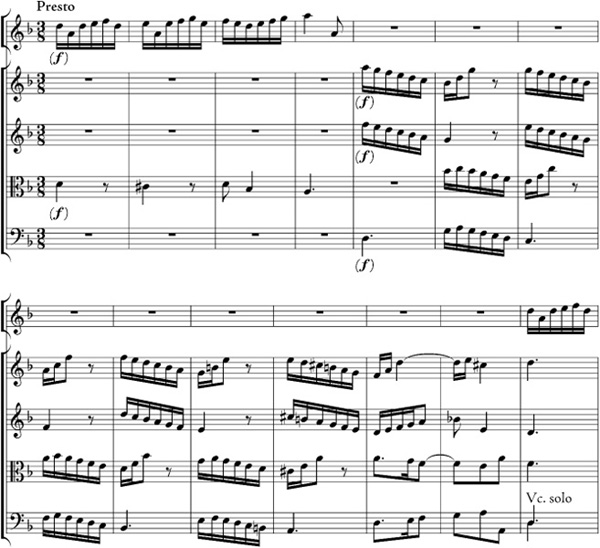

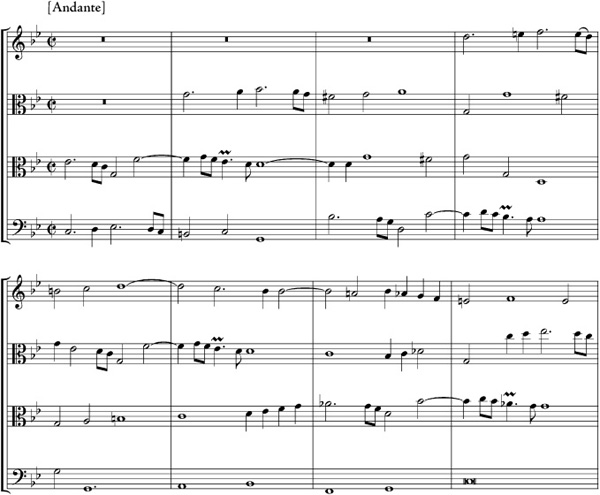

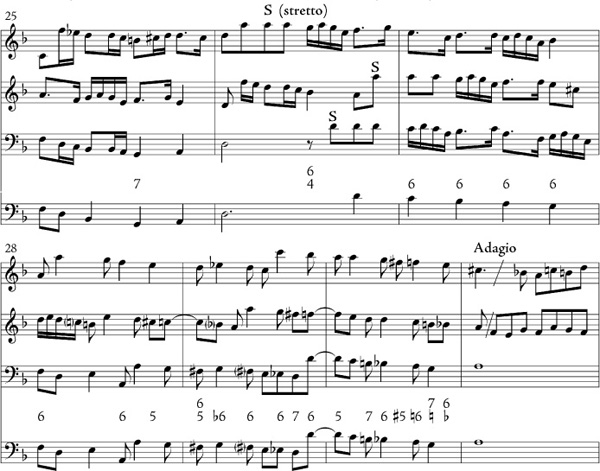

The eleventh church sonata from opus 3 (1689) and the second chamber sonata from opus 4 (1694) make an effective pair for comparison both with one another and with the works of other composers. They are both in the key of G minor, and illustrate between them virtually the full range of Corellian forms and styles. They also show the overlap in practice between the church and chamber genres. Their last movements, especially, might be interchanged (see Ex. 5-1a-b, which show their respective first halves). Although one is marked corrente (a fast triple-metered dance) and the other, untitled, is implicitly a fugal movement, they are virtually identical in form (binary), texture (imitative), and character (lively culmination). But where the second movement of the sonata da camera, the allemanda, is also a binary dance movement, the second movement of the sonata da chiesa (the “canzona” movement) is “abstract” and “through-composed” as befits its forebear. Stylistically, that “canzona” movement (presto) from op. 3, no. 11 (Ex. 5-3) may be the most revealing movement of all. A brief comparison with a work (Ex. 5-2) by one of Corelli’s Austrian contemporaries, Johann Joseph Fux (1660–1741), will indicate what was so novel about the work of the Italian composer, and so potent.

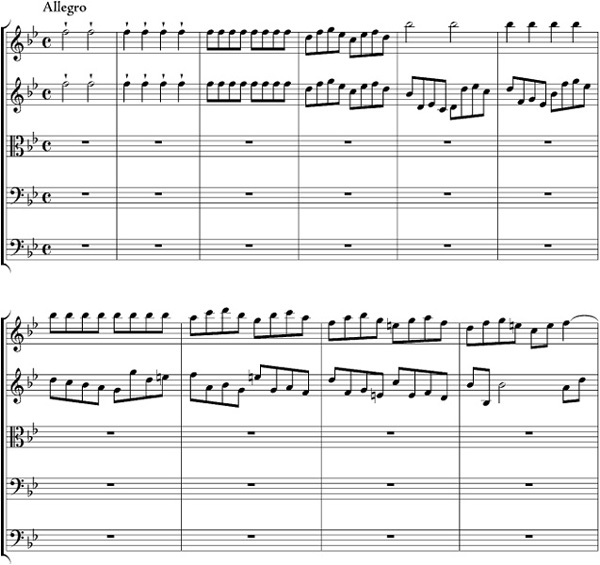

EX. 5-1A Arcangelo Corelli, Sonata da chiesa, Op. 3, no. 11, final Allegro, mm. 1–12

EX. 5-1B Arcangelo Corelli, Sonata da camera, Op. 4, no. 2, final Corrente, mm. 1–25

Fux was a conservative and academic musician. His best-known work was no musical composition but a textbook, Gradus ad Parnassum, which remained for more than a century the standard compendium of the stile antico, the mock-Palestrina style, quick frozen in the sixteenth century, that counterpoint students still learn to imitate in school, using methods that are still derived from Fux’s famous analysis of strict counterpoint into five rhythmic “species.” The stately sonata for two viols and continuo in canonic style (published in 1701), of which the opening is given in Ex. 5-2, illustrates not the stile antico itself, but rather the kind of modern contrapuntal virtuosity that immersion in the stile antico was meant to instill.

Like Corelli’s, Fux’s is a church sonata, meant to replace the Mass Gradual on a festive occasion. Its measured, allemande-like tread, over a “walking bass” whose notes coincide with the metrical pulse, lends it a noble “affect” or mood. The leisurely three-measure interval of imitation sets the standard “sentence-length” for the piece. The opening tune breaks that standard sentence into three asymmetrical, cunningly apportioned phrases, each longer than the last. The long last phrase is accompanied by a rhythmic diminution in the bass, creating a mild “drive to the cadence.”

By comparison, Corelli’s movement (Ex. 5-3) seems virtually jet-propelled, and not only by its faster tempo. Everything about the composition is pressured and intense. The opening three-note motif is identical to that of Fux’s canon. But what a contrast in the way it is handled! What was only a beginning or a headmotive for Fux is the whole thematic substance for Corelli, as if Corelli had decapitated Fux’s theme and tossed its “head” like a ball between the two violins.

EX. 5-2 Johann Joseph Fux, Canonic Sonata in G minor, I, 1–8

Meanwhile, the bass accompanies their agile game of catch with a so-called “running” pattern that moves steadily at a rate twice that of the beat value. The hocket effect between the violins is intensified after the first cadence (m. 7), their tossed motivic ball now consisting of only two notes in an iambic pattern (that is, starting with an upbeat), while the bass continues its frenetic run, made even more athletic by the use of large skips—octaves, ninths, even tenths. At the movement’s midpoint (m. 21) the original motive is tossed again, this time beginning a fourth lower than the opening—i.e., on the fifth degree of the scale. Thus the movement over all has the satisfying harmonic aspect of a binary form: a run out from I to V, and a run back from V to I.

And yet this description has so far omitted the most potent factor in the movement’s extraordinary momentum. That factor is the harmony—the “tonal” harmony, as we now call it. The standardizing of harmonic functions, something going on in all music at the time but particularly foregrounded and made an “issue” in the Italian string music of which Corelli was the foremost exponent, was his most transforming and enduring legacy.

EX. 5-3 Arcangelo Corelli, Sonata da chiesa, Op. 3, no. 11, second movement (Presto)

The opening exchange between the violins describes a preliminary alternation of tonic (I) and dominant (V), that establishes on the smallest level the motion “out” and “back” that will give coherence to the whole. It necessitates a small adjustment in the intervallic structure of the “head motive.” When describing the motion “out” from tonic to dominant, the motive consists of a rising fourth and a falling semitone; but when describing the motion “back” from dominant to tonic, the second interval is altered to a falling third. This kind of adjustment between the motive and its imitation is now called “tonal answer,” because it arises in response to the exigencies of the tonal functions that are driving the music so forcefully.

When the movement “back” from dominant to tonic has been completed, the bass continues to move in the same harmonic direction, passing “Go” (as one says when playing Monopoly) and moving by half-measures through the tonic to the fourth degree or subdominant (C), the seventh degree (F), and the third or mediant (B ), for a total of four moves along an exhaustive cycle that we now call the “circle of fifths.” It was precisely in Corelli’s time, the late seventeenth century, that the circle of fifths was being “theorized” as the main propeller of harmonic motion, and it was Corelli more than any other one composer who put that new idea into telling practice.

), for a total of four moves along an exhaustive cycle that we now call the “circle of fifths.” It was precisely in Corelli’s time, the late seventeenth century, that the circle of fifths was being “theorized” as the main propeller of harmonic motion, and it was Corelli more than any other one composer who put that new idea into telling practice.

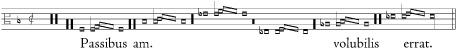

As a sort of harmonic curiosity, the circle of fifths and its modulatory properties had been recognized as early as the mid-sixteenth century. There is, for example, a curious motet by a German humanist musician named Matthias Greiter called Passibus ambiguis (“By sneaky steps”). Published in 1553, its text concerns the vagaries of Fortune, and its cantus firmus consists entirely of the six-note incipit of a famous old song called Fortuna desperata (“Desperate Fortune”), somewhat shakily attributed to the fifteenth-century Burgundian court composer Antoine Busnoys. The little snatch, consisting of the syllables fa–fa–sol–la–sol–fa, is repeated over and over, and is transposed up a perfect fourth (or down a perfect fifth) seven times, so that its tonic pitch proceeds in a perpetual “flatward” progression from F to F , thus: F-B

, thus: F-B -E

-E -A

-A -D

-D -G

-G -C

-C -F

-F . (Meanwhile, the other parts have to scramble for their notes by applying the rules of musica ficta, chromatic alteration at sight, as practiced since the fourteenth century, in unheard-of profusion.) It is an amusing allegory for a serious idea. The circle of fifths symbolizes the fabled “wheel of Fortune,” and by ending on a note that looks like F but sounds like E (and even looks like E on a keyboard or a fretted fingerboard), the composer has transformed the “happiest” final (Lydian fa) into the “saddest” one (Phrygian mi), illustrating the precariousness of luck and the transience of earthly joys (Fig. 5-2).

. (Meanwhile, the other parts have to scramble for their notes by applying the rules of musica ficta, chromatic alteration at sight, as practiced since the fourteenth century, in unheard-of profusion.) It is an amusing allegory for a serious idea. The circle of fifths symbolizes the fabled “wheel of Fortune,” and by ending on a note that looks like F but sounds like E (and even looks like E on a keyboard or a fretted fingerboard), the composer has transformed the “happiest” final (Lydian fa) into the “saddest” one (Phrygian mi), illustrating the precariousness of luck and the transience of earthly joys (Fig. 5-2).

What was merely a curiosity to sixteenth-century musicians was bread and butter to their seventeenth-century successors. The circle of fifths was represented for the first time in a theoretical treatise composed in Polish by a Ukrainian cleric and singing teacher named Nikolai Diletsky (or Dilecki), who lived at the time in the city of Vilnius (see Fig. 5-3). (It was first printed in 1679, in Moscow of all places, in Russian translation.)

FIG. 5-2 Tenor (based on Fortuna desperata) from Matthias Greiter’s Passibus ambiguis, in Gregorius Faber, Musices practicae erotematum libri II (Basel, 1553).

FIG. 5-3 Early diagram of the circle of fifths, from Nikolai Diletsky, Ideya grammatiki musikiyskoy (Moscow, 1679).

This earliest complete circle is a circle like Greiter’s extended to its limit. That is, it is made up of twelve perfect fifths and shows all possible transpositions of a major scale (that is, all the possible keys) but does not define the harmonic relations implicit in a single key. On the contrary, a circle like Greiter’s or Diletsky’s leads ineluctably away from any stable point of tonal reference.

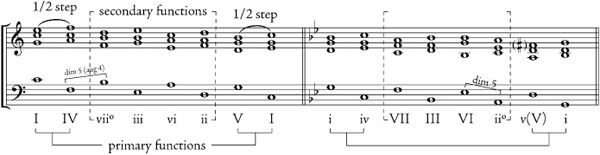

The decisive practical move was to limit the circle of fifths to the diatonic degrees of a single scale by allowing one of the fifths to be a diminished rather than a perfect fifth. When adjusted in this way the circle is all at once transformed from a modulatory device—that is, a device for leading from one key to others progressively more distant—into a closed system of harmonic functions that interrelate the degrees of a single scale. When thus confined, the circle of fifths became an ideal way of circumscribing the key defined by that scale by treating every one of its degrees as what we now call a harmonic root.

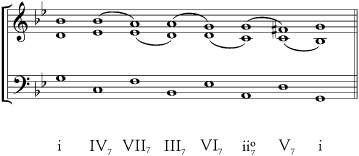

The progression by fifths thus became the definer of “tonality” as we now know it: a model for relating all the degrees of a scale not only melodically but also harmonically to the tonic, and measuring the harmonic “distance” both among the degrees within a single scale and between scales (Ex. 5-4). When the diatonic circle of fifths became the basis of harmonic practice, the major–minor tonal system (or “key system”) can be said to have achieved its full elaboration.

EX. 5-4 Diatonic circles of fifths on C major and G minor

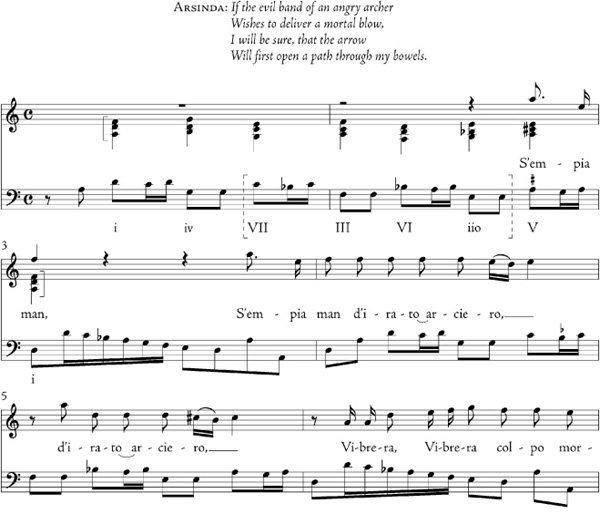

The fully elaborated system’s birthplace was the Italian music of the 1680s. The earliest example known to the author of the use of a full diatonic circle of fifths to circumscribe and thus establish a diatonic tonality occurs in a tiny aria from the third act of L’Aldimiro, Alessandro Scarlatti’s third opera, first performed in the theater of the Royal Palace at Naples in November 1683. It functions here as a ground bass (the more elaborate da capo structure not yet having become the standard; see Ex. 5-5). Like all ground basses, this one surely had a “preliterate” prehistory in improvisation. And like all ground basses it is a static element, a bead for stringing, rather than a dynamic shaper of form.

EX. 5-5 Alessandro Scarlatti, L’Aldimiro (1683), “S’empia man” (Act III, scene 12)

The Presto from Corelli’s op. 3, no. 11 (Ex. 5-3), published in Rome in 1689 but probably composed some years earlier, no longer shows the circle of fifths off as a “device” but simply harnesses it, a fully integrated element of technique, to drive a dynamically unfolding form-generating process. That much is typical of the north-Italian instrumental ensemble music of the time, which for that reason stands as one of the great watershed repertories in the history of European music. It is certainly no accident, moreover, that “tonality” as a fully elaborated system emerged first in the context of instrumental music. Instrumental music stood in far greater need of a potent tonal unifier like the circle of fifths than did vocal music, which can as easily take its shape from its text as from any internal process.

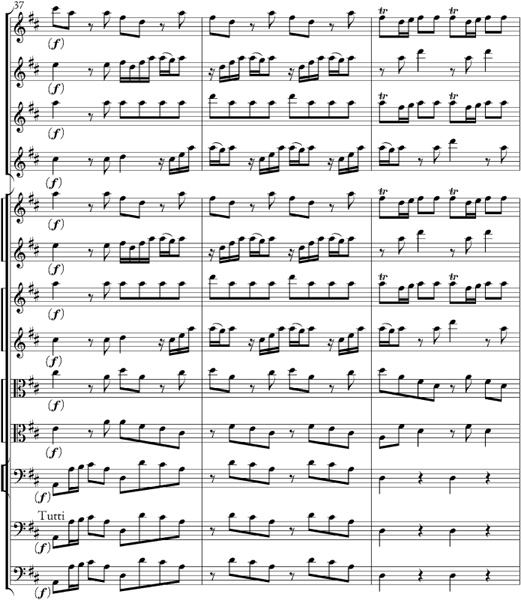

So for our purposes we can let Corelli stand as protagonist of this all-important development—one that put instrumental music on a path of ascendency that would ultimately challenge the preeminent status of vocal genres. For in no other composer of the time is the circle of fifths quite so conspicuously and copiously deployed. In the Presto of op. 3, no. 11, Corelli resorts to it over and over again. The instance already noted at the outset is the first segment of the circle of fifths to appear; but it is by no means the most extensive one, for it only takes the circle half way, to III (what we now call the “relative major”). For a complete circle, fully circumscribing the key of the piece (and then some!), see mm. 11–15.

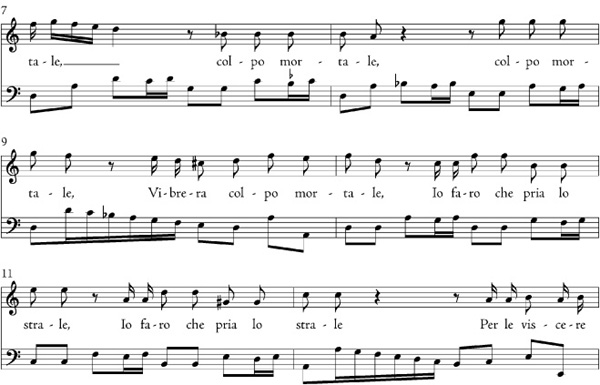

Not only does Corelli use the circle here in its complete form, he also manages to enhance its propulsive force in two distinct ways: first, by doubling the rate of chord change (what is now often called the “harmonic rhythm”) in the second half of the progression; and second, by adding sevenths to most of the constituent chords, especially in the latter (faster, more emphatic) portion. These sevenths, being dissonances, create the need for resolution, thus turning each progression of the circle into a simultaneous reliever and restimulator of harmonic tension. In this intensified form, the circle of fifths becomes more than just a conveyor belt, so to speak; it becomes, at least potentially, a channeler of harmonic tension and a regulator of harmonic pressure—phenomena that can be easily associated or analogized with emotional tensions and pressures, hence harnessed for expressive purposes (see Ex. 5-6).

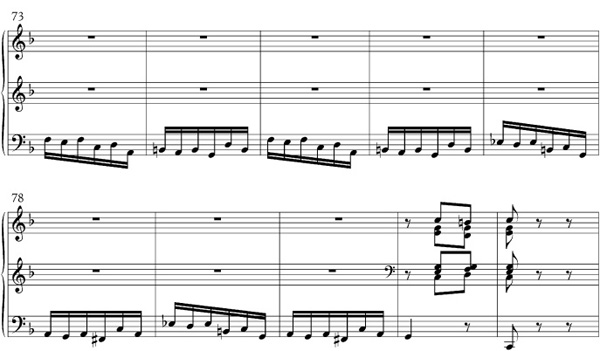

EX. 5-6a Circle of fifths in Corelli, Op. 3, no.11, II (Presto)

EX. 5-6b Circle of fifths in G minor with interlocking sevenths

Note, finally, that when this inexorable cycle gets underway, Corelli (like Scarlatti before him) reinforces it with melodic sequences—another way of demonstrating the inexorability of the progression.

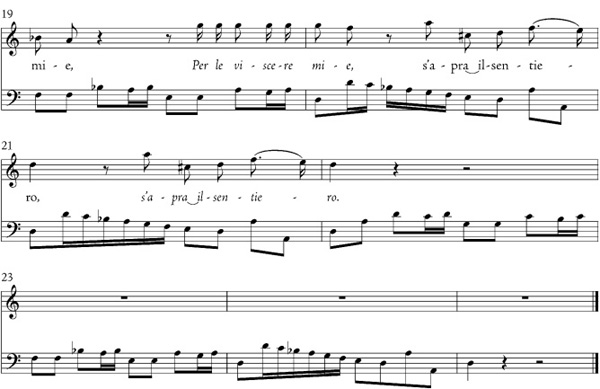

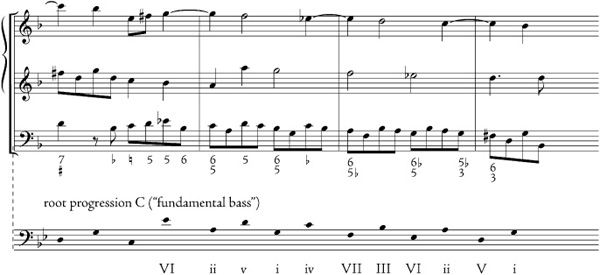

Another kind of standard sequence, not simply melodic but contrapuntal, is the suspension chain. It, too, is easily adapted to the circle of fifths, as Corelli demonstrates in mm. 34–36, the passage that sets up the final cadence: the suspensions between the two violins are accompanied by another supercomplete progression, VI–ii–v–i–iv–VII–III–VI–ii–V-i (Ex. 5-7a). Compare also the suspensions over the “walking bass” at the beginning of the Preludio from the sonata da camera, op. 4, no. 2 (Ex. 5-7b).

EX. 5-7A Arcangelo Corelli, Op. 3, no. 11, II (Presto), mm. 34–36, analyzed to show basse fondamentale

EX. 5-7B Arcangelo Corelli, Op. 4, no. 2, I, mm. 1–5, analyzed to show basse fondamentale

These two techniques in tandem—melodic sequences or suspensions underpinned with dynamic circle-of-fifths harmonies—would become the standard by which all tonal progressions would henceforth be measured. They became, in effect, the basis of what is often called the “Era of Common Practice” and the “sequence-and-cadence” model (shown at its most primitive in Scarlatti’s ground bass) became the chief generator of form in “tonal” or “common-practice” music.

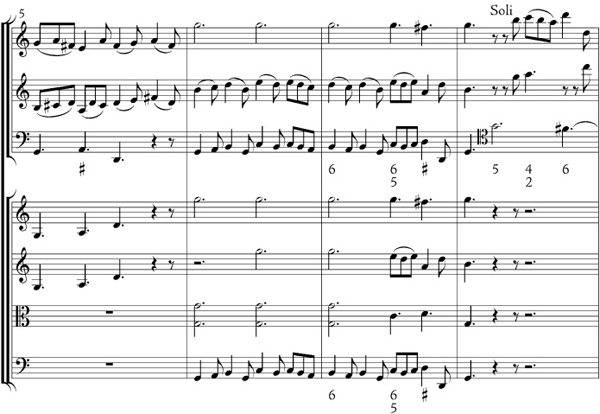

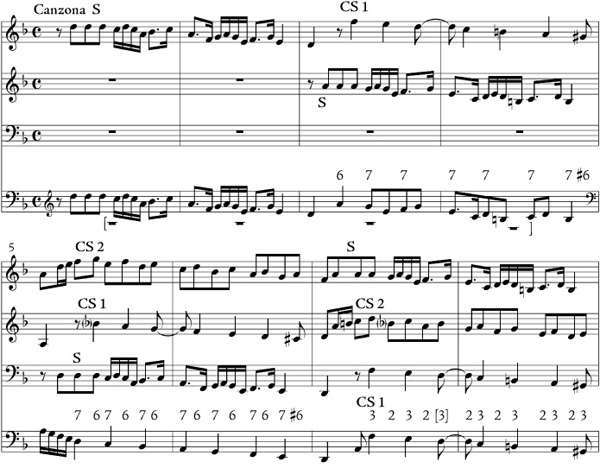

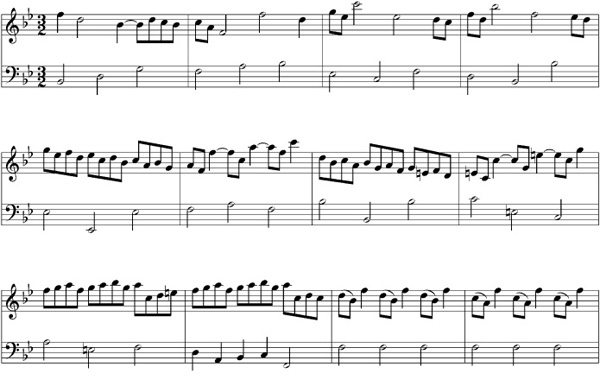

For a final illustration from Corelli’s own work we can take a look at one of his most famous compositions, the “Pastorale ad libitum” from the Concerto Grosso, op. 6, no. 8, a concerto da chiesa “made for Christmas Night” (fatto per la notte di natale) and usually called the “Christmas Concerto” in English. It was probably composed in the 1680s but first published in 1714.

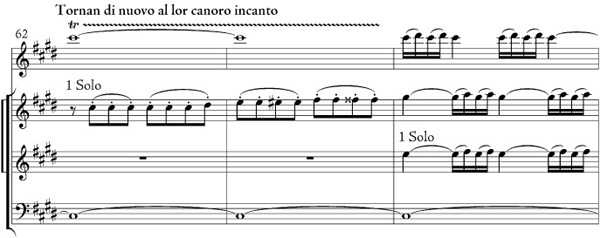

This Pastorale movement is an appendage to the concluding fast movement in the concerto, a dancelike number in binary form. (While untitled, as was the rule in a concerto da chiesa, the movement is clearly a gavotte, and would surely have been so labeled in a concerto da camera.) The Pastorale is marked “ad libitum” (optional) so that the concerto might be performed without it on other occasions, for it is the Pastorale alone that has obligatory or “programmatic” associations with the holiday theme. The Largo tempo and the  meter will bring the Scarlattian “siciliana” to mind with all its rustic associations, and the plangent bagpipe drones with which the backup band (concerto grosso) accompanies the soloists (concertino) in the opening ritornello (Ex. 5-8a), and on its later reappearances, leave no doubt that we are standing among the shepherds, and that the music is painting a manger scene.

meter will bring the Scarlattian “siciliana” to mind with all its rustic associations, and the plangent bagpipe drones with which the backup band (concerto grosso) accompanies the soloists (concertino) in the opening ritornello (Ex. 5-8a), and on its later reappearances, leave no doubt that we are standing among the shepherds, and that the music is painting a manger scene.

EX. 5-8A Arcangelo Corelli, Pastorale ad libitum from the “Christmas Concerto”, Op. 6, no. 8

EX. 5-8B Arcangelo Corelli, Pastorale ad libitum, mm. 8–11, analyzed to show basse fondamentale

That ritornello consists of nothing but three sequential repetitions of a three-bar “rocking” motif (Mary cradling the infant Jesus?) and a two-bar cadence. The little episode for the concertino in mm. 8–11 contains the first circle of fifths. As happens so often, the harmonic circle is unfolded through a suspension chain; in this case, somewhat unusually, the syncopated voice that creates the suspensions is the bass. Its dissonances and resolutions identify an essential root progression by fifths that is broken up and somewhat disguised in the voices above (Ex. 5-8b). The first theorist to employ the technique of “root extractions” used in this analysis and the preceding one was Jean-Phillippe Rameau, in his Traité de l’Harmonie or “Treatise on Harmony” of 1722; as usual, a theorist of the next generation has found a way of systematically rationalizing and representing a manner of writing—or rather of thinking musically—that had already become well established in practice.

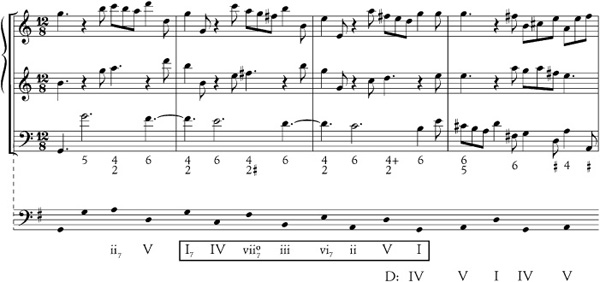

Having characterized the sequence-and-cadence model as a norm that would usher in an era of “common practice,” we need to justify that remark by demonstrating its chronological and geographical spread. The chronological demonstration will emerge naturally enough in the course of the following chapters, but just to show how pervasive the model became within the sphere of Italian instrumental music, and how quickly it spread, we can sneak a peek at a concerto by a member of the generation immediately following Corelli’s.

Alessandro Marcello (1669–1747) was a Venetian nobleman who practiced music as a dilettante—a “delighter” in the art—rather than one who pursued it for a living. His work was on a fully professional level, however, and achieved wide circulation in print. (His younger brother Benedetto, even more famous and accomplished as a composer, was also more prominent as a Venetian citizen, occupying high positions in government and diplomacy.) Marcello, like Corelli before him, was a member of the Arcadian Academy, and maintained a famous salon, a weekly gathering of artist-dilettantes where he had his music performed for his own and his company’s enjoyment. It was for such a gathering that he composed his Concerto a cinque (“concerto scored for five parts”) in D minor, which was published in Amsterdam in 1717 or 1718 and attracted the attention of J. S. Bach, who made it famous in an embellished transcription for harpsichord.

Although published only three or four years later than Corelli’s Concerti Grossi, op. 6, Marcello’s concerto belongs to a different type—one that much more closely resembles the type of concerto we know from the modern concert repertoire. Where Corelli’s concerti were in essence amplified trio sonatas (and while such concerti continued to be written by many composers, particularly George Frideric Handel and his English imitators, long into the eighteenth century), Marcello’s is modeled on the format of the contemporary opera seria aria, such as we encountered in the previous chapter. It is scored for a single solo instrument (replacing Corelli’s “concertino”), in this case the oboe, accompanied by an orchestra (or ripieno, “full band”) of string instruments that chiefly supplies ritornellos.

FIG. 5-4 Antonio Vivaldi, caricature by Pier Loene Ghezzi (the only authenticated life drawing of the composer).

Concertos of this type usually dispensed with the opening “Preludio” of the Corellian model and consisted of three movements: fast ritornello movements at the ends, with a slow “cantabile” (lyrical accompanied solo) in between. This new genre of “solo concerto” seems to have originated in Bologna, at the Cathedral of San Petronio. Its earliest exponent was the violinist Giuseppe Torelli (1658–1709), a contemporary and rival of Corelli’s, who led the Cathedral orchestra. Its “classic” exponent was Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741), the outstanding Venetian composer of the early eighteenth century, to whom we will of course return.

Doubtless Marcello picked up the three movement concerto form from fellow-Venetian Vivaldi. The first movement of his oboe concerto is in a straightforward ritornello form akin to the opening section of a da capo aria. The last movement cross-breeds the ritornello framework with the binary dance form familiar to us from the Corelli “da camera” style. (Marcello, recall, wrote not for the church service but for his own aristocratic salon.)

Of particular interest is the structure of the main ritornello theme (Ex. 5-9a). It begins with a four-measure “head motive” over a bass that is clearly derived from the old “descending tetrachord” of chaconne and passacaglia fame. It ends, accordingly, on a half cadence. Ground basses remained popular in the Italian string repertory. The last sonata da camera in Corelli’s opus 2, published in 1685, consisted of a single showy ciaccona over a descending tetrachord, and the most famous solo sonata in Corelli’s opus 5, publishedin 1700, was a magnificent set of variations over the eight-bar folia ground, one of the old dance “tenors” that went back to the sixteenth century. Corelli’s “La Folia” has remained a virtuoso warhorse—usually in modernized and “violinistically enhanced” transcriptions—to the present day.

All resemblance to the ground bass, however, ends with the fifth measure of Marcello’s ritornello. Instead of another four-bar phrase over the same bass, we now get a nine-bar monster consisting of four sequential repetitions of an angular scale-plus-arpeggio idea that unfolds over a single exact and complete circumnavigation of the circle of fifths, finally hooking up with a cadence formula that adds the “extra” ninth measure to its length. The ensuing oboe solo, a variation on the ritornello, reproduces and embellishes its harmonic structure: a four-bar approach to a half cadence followed by a full circle of fifths accompanying a series of melodic sequences (reduced this time to four measures by doubling the harmonic rhythm) and a concluding set of ascending sequences that reaches a cadence on III, the relative major.

A set of rising sequences, unlike the falling type that arises more or less straightforwardly out of the circle of fifths, requires a different sort of harmonic support. The implied root movement is made explicit in the next oboe solo (mm. 36–52), a fascinating interplay of melodic and harmonic contours (Ex. 5-9b). It begins with the usual four-bar “head,” followed by a sequential elaboration. The sequences in this case begin (mm. 36–41) by rising. The harmonies change bar by bar in a root progression that ascends by fourths and falls by thirds: F (III)-B (VI)-G (IV)-C(VII)-A(V)-D(I). Immediately on reaching the original tonic, the circle of fifths kicks in and the sequences come tumbling down in double time (mm. 41–46), as if to remind us that rising is always more laborious than falling.

(VI)-G (IV)-C(VII)-A(V)-D(I). Immediately on reaching the original tonic, the circle of fifths kicks in and the sequences come tumbling down in double time (mm. 41–46), as if to remind us that rising is always more laborious than falling.

But notice that the rising progression is presented in such a way that if the “functional bass” notes were sampled at the bar lines beginning at m. 36, they would create a rising chromatic line that exactly reversed the old passus duriusculus, the chromatically descending groundbass tetrachord of old: (A)-B -B-C-C

-B-C-C -D. In effect we have a series of interpolated leading tones (again familiar from longstanding practice, in this case the downright ancient principles of musica ficta); and if we now interpret those leading tones within the nascent system of harmonic functions (i.e., as the thirds of dominant triads), we have a new principle—the “applied dominant”—that will emerge over the years as the primary means of harmonic and formal expansion within the tonal practice that is just now reaching full elaboration.

-D. In effect we have a series of interpolated leading tones (again familiar from longstanding practice, in this case the downright ancient principles of musica ficta); and if we now interpret those leading tones within the nascent system of harmonic functions (i.e., as the thirds of dominant triads), we have a new principle—the “applied dominant”—that will emerge over the years as the primary means of harmonic and formal expansion within the tonal practice that is just now reaching full elaboration.

EX. 5-9A Alessandro Marcello, Oboe Concerto in D minor, III, beginning

We are witnessing a truly momentous juncture in the history of harmony: the birth of harmonically controlled and elaborated form. In the Italian instrumental music of a rough quarter-century enclosing the year 1700, we may witness in their earliest, “avant-garde” phase the tonal relations we have long been taught to take for granted. And yet from the very beginning this avant-garde style of harmony was easily and eagerly assimilated, both by composers and by listeners. For composers it made the planning and control of ever larger formal structures virtually effortless. To listeners it vouchsafed an unprecedentedly exciting and involving sense of high-powered, directed momentum, and promised under certain conditions a practically visceral emotional payoff. The tonal system at once gave composers access to a much more explicit and internal musical “logic” than they had ever known before, and also gave them the means for administering an altogether new kind of pleasurable shock to their audiences.

These new powers and thrills made the new style virtually irresistible and assured its rapid spread. Our geographical witness to that spread can be Henry Purcell. Up to now we have viewed Purcell chiefly through a French-tinted lens, as befits a composer for the Restoration stage. He was equally receptive to the new winds blowing from Italy, however, and equally reflective of them, provided one looks for the reflection in the right place. That place, of course, would be string ensemble music, an area in which Purcell’s art underwent an astoundingly quick and thorough transformation at very nearly the beginning of his career. Rarely can one trace so sudden a change of style, or be so sure about its cause.

EX. 5-9B Alessandro Marcello, Concerto in D minor, III, mm. 36–52, analyzed to show basse fondamentale

Purcell was heir to the rich and insularly English tradition of gentlemanly ensemble music for viols that we visited briefly in chapter 3. His first important body of compositions, in fact, was a set of consort “fantazias” that he wrote in the summer of 1680, the year he turned twenty-one. They well exemplify the somewhat archaic imitative polyphony the English held on to so long into the seventeenth century—the “interwoven hum-drum” Roger North affectionately described in his memoirs of rural music-making.

Ex. 5-10, the opening “point” in one of Purcell’s fantasies of 1680, will give us one last look at this style, particularly poignant in its peculiarly English harmonic intensity, replete with false relations of an especially dissonant kind (sevenths “resolving” to diminished octaves!) on practically every cadence. The timing of the entries on the principal motif (first heard in the “tenor”), their progress through the texture, and, most of all, their transpositions seem to be waywardness itself. It is hard to imagine the composer of this piece and the composer of Corelli’s sonatas and concertos as contemporaries, or to believe that Corelli’s first book of trio sonatas was published less than a year after Purcell’s fantasies were composed.

EX. 5-10 Henry Purcell, “Fantazia 7”a 4, mm. 1–26

And yet hard on the heels of those fantasias, in 1683, Purcell published his own book of “Sonnatas of III Parts: Two Viollins And Basse: To the Organ or Harpsecord” that advertise his full capitulation to what old Roger North, who detested it, called the “brisk battuta” of the Italians.1 Battuta is Italian for “beat,” and so it was evidently the fast tempi and the heavy regularity of its rhythm (or maybe just the professional virtuosity that it required) that seems to have affronted traditional English taste in the new Continental fashion. But Purcell, although only six years younger than North, had no such scruple about appropriating for himself and his countrymen “the power of the Italian Notes, or [the] elegancy of their Compositions,” as he put it in the preface to his collection.

The composer whose work Purcell chiefly aped in his trio sonatas was probably not Corelli (although Corelli’s first book of church sonatas would have been available to him) but rather one Lelio Colista (1629–80), an older Roman contemporary of Corelli’s, best known as a lutenist or “Theorbo man” (to quote an English traveler who heard him perform in church in 1661). His sonatas were never published and consequently fairly little known or admired—except, by chance, in England, where they circulated widely in manuscript. The third sonata from Purcell’s set is modeled closely on the church sonatas of Colista, and therefore (somewhat curiously, but characteristically for the island kingdom) preserves the new Italian style at a slightly earlier stage of development than Corelli had already achieved.

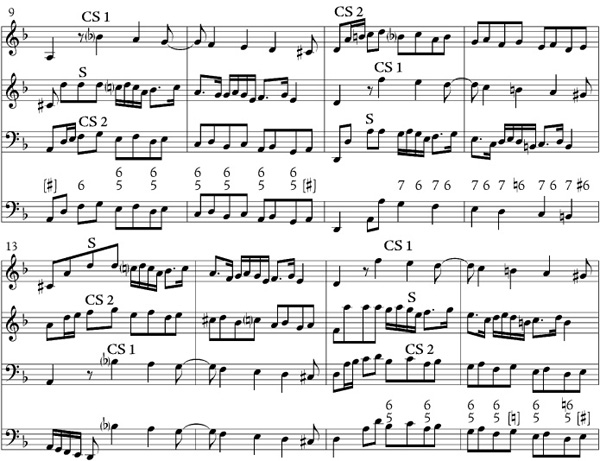

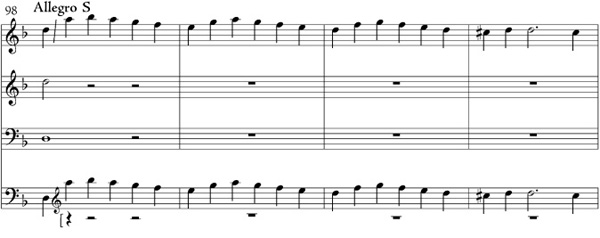

There is another element, besides its harmonically driven form, that defines the new Italianate style. The use of the old-fashioned term “Canzona” for the second movement in Purcell’s sonata (Ex. 5-11) is adopted directly from Colista, as are the movement’s form and texture, somewhat more thoroughgoingly and conservatively contrapuntal than the Corellian norm. It is a very competently crafted fugue, worked out with the perhaps excessive regularity and rigor one might expect to find in a self-conscious (and still youthful) imitator. But since it is the first fully developed fugue (or to be painstakingly accurate, the first fully developed specimen of what would later be called a fugue) to be encountered in this book, it is worth studying in some detail. In the description that follows, the standard modern terminology for the fugue’s components and events will be employed (and set off in italics), even though—like the word “fugue” itself—they are not strictly contemporaneous with the piece at hand.

A fugue is like a single extended and colossally elaborated point of imitation from the older motet or canzona. There is a single main motive or theme, called the subject, on which the whole piece is based. In the opening section of such a piece, called the exposition, the subject is introduced in every voice. In the present example, this has been accomplished by the time the downbeat of the seventh measure is reached. First the subject is heard alone (though doubled by the organ continuo) in the first violin. Then the second violin plays the subject “at the fifth” (meaning a fifth up or, as here, a fourth down); when played at this transposition, it is called the answer. The counterpoint with which the first violin accompanies the answer (here, a chain of syncopations/suspensions) is called the countersubject (CS). Next to enter is the cello, playing the subject in its original form, though down an octave; hence the entering voices continually describe a quasi-cadential “there and back” alternation of tonic and dominant to lend the newly important sense of tonal unity to the exposition. When the third voice to enter plays the subject, the second voice shifts over to the CS (suitably transposed), and the first voice plays a second CS that harmonizes with both the other melodies. These fixed components of the texture are given analytical labels in Ex. 5-11: S (for subject, or when transposed to the “fifth,” the answer), CS1 for the syncopated CS, and CS2 for the second one.

EX. 5-11 Henry Purcell, Sonnatas of III Parts, no. 3 in D minor, mm. 1–37

By now, with all the voices in play, the exposition has performed its function and could end. But this fugue, as already noted, is very demonstratively, even compulsively worked out, and the composer is determined to display his complex of three voices in every possible permutation (for which reason this kind of extremely regular and thoroughgoing fugue is sometimes called a “permutation fugue”). Up to now the subject has always been found in the lowest sounding voice. And so in the seventh measure, still inexorably alternating subjects with answers, Purcell brings it back in the highest voice while keeping the two countersubjects as before.

The texture is now inverted, with subject above countersubjects rather than below. Thus, Purcell announces, this fugue is of the especially rigorous variety known as double fugue because it is written in “double”—that is, invertible—counterpoint. (As any student who has taken counterpoint knows, in order for counterpoint to be invertible it must conform to especially stringent rules of dissonance treatment.) This “double exposition” does not end until the subject (or answer) has circulated through the texture three times and been in every possible juxtaposition with the other voices. It is in fact a triple exposition.

The exposition ends in m. 19 and is followed by what is called an episode, which simply means a stretch of music during which the subject is withheld. Even the episode is contrapuntally complex in this very determined fugue: a three-beat phrase in anapests (short–short–long) that on its repetitions cuts across the four-beat bar and is capriciously alternated with its inversion. Also playful (and welcome, in compensation for the dogged regularity of the exposition) is the episode’s asymmetrical five-bar length.

The subject reappears in m. 24, still whimsically accompanied by the episode figure, now extended and continuous. When the answer comes in at m. 26 (top voice) Purcell pulls one last contrapuntal stunt: the other voices now pile in with overlapping entries on the subject and answer, so that every part is eventually playing some part of it at the same time. This foreshortening device is called the stretto (Italian for “straitened”—tightened or made stricter) and is a common way of bringing fugues to a close. (Strettos have to be worked out in advance while the subject is being cooked up; not every subject will produce one.) Another conventional touch is the concluding passage (or coda, “tail”) over a sustained dominant in the bass: the latter is known as a pedal, or “pedal point,” because the device originated in organ music, where the player produces it by literally planting a foot on the rank of tone-producing pedals with which large built-in church organs are equipped. It is during the pedal point, which projects the cadential harmonic function so forcefully, that Purcell again goes playful, this time with chromatically inflected lines that give a tiny, perhaps nostalgic, whiff of the expressive harmony so endemic to the older English style exemplified in his own fantazia of a few years earlier (cf. Ex. 5-10).

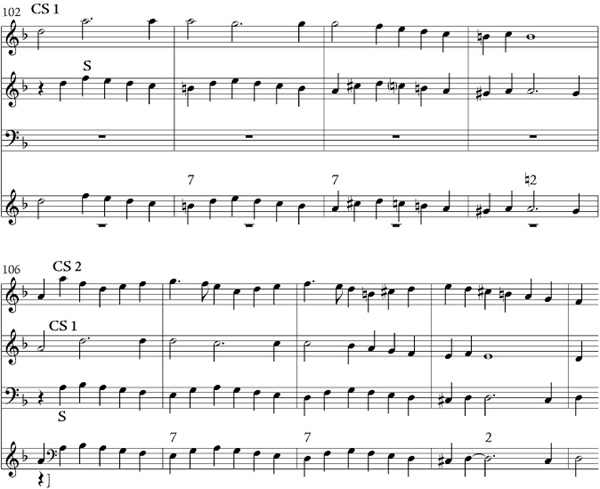

It is interesting to compare the “canzona” in Purcell’s sonata with the other fugal movement, the fourth (Allegro), which bursts in upon the sarabande-like third movement without pause (Ex. 5-12). Its subject descends from the fifth (dominant) degree of the scale to the first, which calls for a “tonal answer” that in effect transposes the subject (once past the first note) up a degree, so that the V-I descent will be balanced by a complementary descent from I to V (covering a fourth, not a fifth). This movement, too, has a first countersubject in syncopations, producing suspensions. But whereas the suspensions in the second movement resolved the old-fashioned “intervallic” way (sevenths resolving to sixths over a stationary bass), the suspensions in the last movement are channeled—as in the newer, Corellian style—through the bounding circle of fifths. The sense of harmonic purpose, of activity at once more intense and more directed than ever before, was as great a stylistic breakthrough for Purcell as it was for every other composer who took it up.

And yet to us, at the other end of its history, it can sound, paradoxically enough, like a step backward. “Those weaned on Purcell’s great Fantasias of 1680,” a recent commentator has observed, “with their superlative juxtaposing of archaic longings and innovative yearnings, might all too easily dismiss the composer’s sonatas as formulaic and fashion-bound.”2 But the familiar “tonal” formulas and patterns were what struck late seventeenth-century ears as innovative, just as the harmonic vagaries that can sound so delightfully unexpected and personal to us—even “other-worldly,” to quote the same critic—struck contemporary ears as familiar, hence entitled to what familiarity breeds.

Purcell was highly conscious that he was “advancing” the music of his homeland by bringing it into contact with the latest emanations from the continent. He underscored the point by retaining “a few terms of Art” from his Italian sources, namely the vocabulary of tempo and expression marks that are familiar to all musicians in the European literate tradition to this day.3 It was Purcell who in his preface to the 1683 Sonnatas first defined words like Adagio, Grave, Largo, Allegro, Vivace, and Piano for English-speaking players.

EX. 5-12 Henry Purcell, Sonnatas of III Parts, no. 3 in D minor, m. 98–110

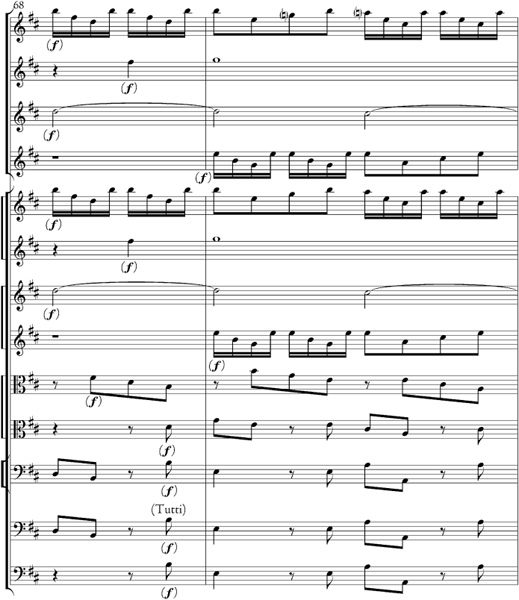

Not that a great and practiced musical imagination could not work refreshing and fanciful changes on the new styles, and keep them fresh. Purcell in 1683 represented the first English adoption of the Corellian (or slightly pre-Corellian) style. It was the style itself that was then new. Merely using it, even at its most basic level, was an innovative act. In a later chapter we will take a long look at the work of George Frideric Handel, a naturalized Englishman who belonged to the generation of Corelli’s or Purcell’s sons and daughters, and who was one of the great representatives of the “High Baroque” style (as it is now so often called) that flourished, particularly in northern Europe, in the first half of the eighteenth century. It will be worthwhile at this point to have a preliminary look at Handel, who knew and played with the venerable Corelli during his apprentice years in Rome, to see what he did with the Corelli style in his set of “Twelve Grand Concertos,” opus 6, published in London in 1740 (more than a quarter of a century after Corelli’s death), one of the very latest major collections of Concerti Grossi.

The seventh concerto grosso from the set is dated 12 October 1739 on its autograph manuscript. By Handel’s day, and especially in England, the old distinction between church and chamber styles had become meaningless. The Anglican church service did not make room for sonatas or concerti da chiesa; instrumental chamber music was by definition secular entertainment. Handel’s concerto has five movements, of which the first two, a kind of prelude and fugue, are a clear echo of the church style. Just as clearly, the last movement, a dance in binary form, echoes the chamber style.

The third and fourth movements, paired slow–fast like the first two, are played without repeats but go through an elaborate harmonic “round trip” such as one finds in binary movements. The Andante, with periodic returns of a rhythmically catchy opening melody in different keys (yet without any interplay of solo and tutti) seems to be a hybrid, combining the characteristic features of the ritornello style, typical of arias or concertos, with those of the dance, typical of suites. The whimsical, diverting quality of the whole concerto is most obviously suggested by the adoption of an English national dance, the hornpipe (also known, fittingly enough, as the “delight” or “whim”) for the concluding movement (Ex. 5-13). As danced in the eighteenth century, the hornpipe was a “longways country dance,” meaning (paradoxically) an urban, genteel couples dance in which the dancers assembled in long files. The rather complicated steps were adapted from an older solo dance often done competitively by sailors; the rhythms, as in Handel’s adaptation, were often syncopated. Handel was surprising his English listeners and players with a delightful stylization of a dance they all knew “in situ,” extended delightfully (and somewhat ridiculously) to monumental length. Ex. 5-13 shows just the first half, allowing the first violin part and the bass to stand in for the four-part texture.

The same whimsicality, the same aim to amuse, can be seen in the second, fugal movement of Handel’s concerto. Using a style that by then had long since become a standard procedure to which nobody paid much attention qua style, Handel subtly “defamiliarizes” it in order to produce the same kind of diverting piquancy Purcell could achieve simply by using the style when it was as yet unfamiliar. Consider first the one-note subject itself, a famous joke. The impression of mindless jabber, “put on” like a comic mask, is actually the means by which Handel exercises a subtle control over the texture of the fugue and keeps it lucid. The progressive rhythmic diminution from half notes to eighths that must run its course before the subject is allowed to quit its initial pitch, and the continuation of the eighth-note pulse into the sequential patterns of the countersubject insure that the subject’s rhythmic “head” in half notes will stand out against the eighth-note ground rhythm on its every entrance, wherever in the texture it may occur, and gives the composer an unusual freedom in placing or “voicing” surprising subject entries.

EX. 5-13 G. F. Handel, Concerto grosso in B-flat major, Op. 6, no. 7

Another area of potential surprise is the timing of subject entries. We see an example of this within the first exposition (Ex. 5-14) in the little three-bar episode (on material derived from the countersubject) that breaks the implicit pattern defined by the second subject entry in mm. 9–11 and delays the third. Thereafter, the whole fugue consists of a game of hide-and-seek: when and where will the subject next turn up? The game is rendered all the more obviously (and amusingly) a game by the way episodes are made to “mark time” with static or obsessive repetitions (at times virtually denuded of counterpoint) of the four-eighths motif first heard in the second violin at the beginning of the countersubject (m. 5).

EX. 5-14 G. F. Handel, Concerto grosso in B-flat major, Op. 6, no. 7, Allegro, mm. 1–22

So in the hands of its ablest practitioners, a style that derives its identity and its strength from the regularity of its patterns is subjected to calculated disruptions that honor the patterns (as the saying goes) “in the breach,” and that turn “form” into a constant play of anticipations and (dis)confirmations. This process of setting up and either bearing out or letting down the listener’s expectations has quite recently been termed the “implication/realization” model of musical form, and has been the focus of much investigation by psychologists, who regard it as a relatively pristine embodiment of the learning (or “cognitive”) processes by which humans adapt to their environment.4

In the instrumental music of the early eighteenth century, the listener’s interest is engaged by these abstract processes of “conditioned response” as if in compensation for the absence of a text as cognitive focus. They brought about a virtual revolution in listening, in which the listener’s conscious mind was much more actively engaged than previously in these processes of forecast and delayed fulfillment, and in which the form may even be said to arise out of the play of these cognitive processes. When it was new, such abstract yet intensely engaging instrumental music seemed to some listeners to be very aggressive both in what it demanded from them in the way of active perceptual engagement, and in its effects on them in the way of intense passive experience.

One particularly uncomprehending listener, an aged French academician named Bernard le Bovier le Fontenelle(1657–1757), who was used to the idea of music not as abstract intellectual process but as “imitation” of feeling, reacted to a bit of Italianate string music with the exasperated question, “Sonate, que me veux-tu?” which means “Sonata, what do you want from me?”5 He was not as uncomprehending as he thought. His indignation was aroused by his correct perception that the sonata wanted his active mental engagement. Music became a more strenuous experience but also a more powerful (and at the same time a more “autonomous”) one. And yet, as we have seen, the process of attending to such an autonomous musical structure can be endlessly diverting. Handel’s fugue, though far more sophisticated than Purcell’s, is also lighter—prankish rather than dogged.

We can witness the new instrumental style at its most sublime, and experience its newfound power to deliver both intellectual gratification and a powerful emotional payoff, by stealing an advance look at the work of Handel’s exact contemporary, Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach’s impressive organ Toccata in F major—probably composed between 1708 and 1717 while Bach held the post of organist at the court chapel of Weimar (a town in Eastern Germany, then known as Saxony)—is in some ways an old-fashioned work, but in others it is downright prescient. A virtuoso showpiece for the organist, Bach’s Toccata belonged to an ancient tradition, one that we have traced back to the Gabrielis and Sweelinck at the end of the sixteenth century, and which lay behind the development of the Corellian “church sonata” as well. Toccatas, etymologically, were “touch pieces.” They foregrounded the playing process itself. And what could be more characteristic of the organ’s particular playing process than the activity of the player’s feet? It was in the fancy footwork that organ playing differed from the playing of any other instrument of the time, and Bach spotlights that footwork in various highly contrasting ways.

The opening section of the piece (Ex. 5-15a) is accompanied through most of its duration by what may well be the longest “pedal point” ever written, one that dramatically

EX. 5-15A J. S. Bach, Toccata in F, BWV 540, mm. 1–82

advertises the derivation of what is often thought of as an abstract harmonic device from the practical technique of organ playing. The organist plunks his foot down on the F pedal and thereby opens up a flue pipe through which air will rush as long as the pedal is depressed. The low F thus produced can last indefinitely; Bach lets it sound for the two minutes or so that it takes to execute the canon that runs up above between the two keyboards (or manuals). The organ is the only instrument capable of sustaining a note of such a length without any break. The implied harmonies that it supports—notably the dominant—are often dissonant with respect to it, but Bach concentrates for the duration of the pedal on the tonic (I) and subdominant (IV) harmonies (both of which contain the F) and on the tonic-plus-E , which functions as an “applied dominant” of B

, which functions as an “applied dominant” of B (“V of IV”).

(“V of IV”).

Bach lets the canon in the manuals peter out in mm. 53–54 without any real cadence, whereupon the pedals take over with one of the most extended solos for the feet that Bach or any organ virtuoso ever composed. It lasts 26 measures, roughly half the length of the preceding canon-over-pedal, and consists entirely of sequential elaborations of the canon’s opening pair of measures, itself already a sequential elaboration of a “headmotif” with a characteristic contour consisting of a “lower neighbor” and its resolution, followed by a consonant leap down, a larger consonant leap up, and a return to the original note. The blow-by-blow description is cumbersome indeed, but the contour itself is instantly apprehensible. (Indeed, the sense of triple meter in the piece depends on our apprehending it, since the rhythm is just an undifferentiated stream of sixteenth notes, and the organ cannot produce accentual stresses; thus the only thing that can serve to define the measure as a perceptual unit here is the recurrent pitch contour and its sequential repetitions.)

A 26-measure section or “period” comprising nothing except sequential repetitions of a single pitch contour is a quintessential display of the technique of melodic elaboration and form-building known as Fortspinnung (“spinning out”). This handy term was actually coined (by the Austrian music historian Wilhelm Fischer) in 1915, but it very neatly defines the techniques of melodic elaboration that arose with the concerto style as a sort of by-product of the circle of fifths and the other standard patterns of chord succession that we have already observed, the melody arising (for the first time in the history of musical style) out of an essentially harmonic process.

In Bach’s long passage of pedal Fortspinnung, the circle of fifths acts as a long-range modulatory guide, within which many smaller cadences and sequences take their place. The long-range workings of the circle of fifths can best be gauged by noting accidentals as they occur. The first accidental to appear (in m. 61)is E , which has the effect, here as previously, of invoking the scale of B

, which has the effect, here as previously, of invoking the scale of B major (IV), which in turn identifies A as leading tone (“vii of IV”). When E-natural occurs (in m. 66) as an accidental that explicitly cancels the E

major (IV), which in turn identifies A as leading tone (“vii of IV”). When E-natural occurs (in m. 66) as an accidental that explicitly cancels the E , it asserts its function as leading tone to the original tonic (I). The next accidental to appear (m. 70) is B-natural, the leading tone of C (V), and the next one after that (m. 78) is F

, it asserts its function as leading tone to the original tonic (I). The next accidental to appear (m. 70) is B-natural, the leading tone of C (V), and the next one after that (m. 78) is F , the leading tone of G (ii, but retaining the B-natural so as to turn ii into “V of V,” and with the E

, the leading tone of G (ii, but retaining the B-natural so as to turn ii into “V of V,” and with the E reinstated to suggest—colorfully but falsely, as it turns out—a cadence on C minor).

reinstated to suggest—colorfully but falsely, as it turns out—a cadence on C minor).

The whole passage may be summed up harmonically in terms of a slowly unfolding circle of ascending fifths: B (IV)-F (I)-C (V)-G (ii/V of V), all preparing the bald cadence formula on C (V) in mm. 81–82. That the first explicit cadence in the piece takes place so late is a testimony to the efficacy of the Fortspinnung technique in organizing vast temporal spans. And the same vast span is now replayed on C (V), replete with 54-measure canon-over-pedal and mammoth pedal solo, now expanded to 32 measures in length.

(IV)-F (I)-C (V)-G (ii/V of V), all preparing the bald cadence formula on C (V) in mm. 81–82. That the first explicit cadence in the piece takes place so late is a testimony to the efficacy of the Fortspinnung technique in organizing vast temporal spans. And the same vast span is now replayed on C (V), replete with 54-measure canon-over-pedal and mammoth pedal solo, now expanded to 32 measures in length.

Again a cadence on C (V) is elaborately prepared and the same cadential formula is invoked. But this time the cadential preparation is detached from the resolution and repeated no fewer than seven times (Ex. 5-15b), dramatically delaying the arrival of the keenly anticipated stable harmony (the “structural downbeat,” as it is often called). When the C major triad in root position is finally sounded, it can no longer be merely taken for granted as the inevitable outcome of a standard harmonic process. The process of delay has “defamiliarized” it and made it the object of the listener’s keenly experienced desire.

Bach’s Toccata is one of the earliest pieces to so dramatize the working out of its form-building tonal functions, adding an element of emotional tension that is inextricably enmeshed in its formal structure. The listener’s active engagement in the formal process is likewise dramatized. The listener’s subjective reaction to the ongoing tonal drama is programmed into the composition. Subjectivity, one may say, has been given an objective correlate. It even makes a certain kind of figurative sense to ascribe the desire for resolution to the notes themselves, objectifying and (as it were) acting out the listener’s involvement.

So far we have had a decisive tonal movement from I (the opening pedal) to V (the long-delayed and intensified arrival at m. 176, shown in Ex. 5-15b). We may now expect the usual leisurely return, by way of intermediate cadences on secondary degrees. And that is what we shall get—but not without dramatic withholdings and ever more poignant delays. The measures that immediately follow Ex. 5-15b unfold a sequential progression along the by-now-familiar descending circle of fifths: C (V)-F (I)-B (IV)-E (vii°)-A (iii). The chord on A is expressed as a major triad, connoting an applied dominant to D (vi), just where one might expect the “medial cadence” on the way back to the tonic.

(IV)-E (vii°)-A (iii). The chord on A is expressed as a major triad, connoting an applied dominant to D (vi), just where one might expect the “medial cadence” on the way back to the tonic.

EX. 5-15B J. S. Bach, Toccata in F, BWV 540, mm. 169–76

That expectation will indeed be confirmed, but only after a really hair-raising strategy of delay shown in Ex. 5-15c has run its course. At the short range the A major chord (“V of vi”) is allowed to reach its goal (m. 191), but the D minor chord is immediately given a major third, a seventh, and even a dissonant ninth, turning it in its turn into an applied dominant (“V of ii”) along the same circle of fifths. The G minor chord (ii) is also manipulated and compromised as a goal, first by harmonizing the G as part of a diminished seventh chord (m. 195), then as part of a “Neapolitan sixth” such as we observed in the last chapter in connection with Alessandro Scarlatti (m. 196). The Neapolitan sixth always acts as a cadential preparation to the dominant, and so the A returns (m. 197) with its previously assigned function (“V of vi”) intact. Again (mm. 197–203) we get the elaborately stretched-out preparation we heard previously in mm. 169–76. But this time, the already much-delayed resolution is thwarted (m. 204) by what was probably the most spectacular “deceptive cadence” anyone had composed as of the second decade of the eighteenth century.

EX. 5-15C J. S. Bach, Toccata in F, BWV 540, 188–219

A deceptive cadence (as it is called in today’s analytical language) is not just any avoided or interrupted cadence. In a deceptive cadence the cadential expectation is partially fulfilled, partially frustrated, producing an especially pungent effect. Most often it is the leading tone that is resolved, the fifth-progression that is evaded; the most common way of achieving this is to substitute a submediant chord for the tonic (Ex. 5-15d).

EX. 5-15D Ordinary deceptive cadences in D major and D minor

Bach does something similar, but much spikier. The leading tone, C , is resolved to D, the expected tonic, in m. 204; but the bass A proceeds, not along the circle of fifths to another D, but rather descends a half step to A

, is resolved to D, the expected tonic, in m. 204; but the bass A proceeds, not along the circle of fifths to another D, but rather descends a half step to A , clashing at the tritone with the soprano D. And the tritone is harmonized with one of the most gratingly dissonant chords available in the harmonic language of Bach’s time: a dominant seventh in the “third inversion” (also known as

, clashing at the tritone with the soprano D. And the tritone is harmonized with one of the most gratingly dissonant chords available in the harmonic language of Bach’s time: a dominant seventh in the “third inversion” (also known as  position), in which the bass note is the seventh of the chord, dissonant with respect to all the rest.

position), in which the bass note is the seventh of the chord, dissonant with respect to all the rest.

The  chord is a chord in drastic need of resolution, and Bach resolves it in timely fashion. That local resolution, however, takes him far afield of his long-range harmonic goal. It is to the Neapolitan sixth chord. Bach first “normalizes” the Neapolitan harmony by treating it as part of a standard sequential progression (mm. 204–209) similar to the one noted in Marcello’s oboe concerto, but made stronger by putting all the applied dominants in

chord is a chord in drastic need of resolution, and Bach resolves it in timely fashion. That local resolution, however, takes him far afield of his long-range harmonic goal. It is to the Neapolitan sixth chord. Bach first “normalizes” the Neapolitan harmony by treating it as part of a standard sequential progression (mm. 204–209) similar to the one noted in Marcello’s oboe concerto, but made stronger by putting all the applied dominants in  position. In m. 210 the Neapolitan is regained, reiterated, and (after yet another set of feints) finally directed “home” to the long-awaited D in mm. 217–19.The process of delay, from the initial adumbration of the cadence to its ultimate completion, has unfolded over an unprecedented span of 32 intensely involving measures, a passage full of finely calculated yet overwhelmingly powerful harmonic jolts and thrills.

position. In m. 210 the Neapolitan is regained, reiterated, and (after yet another set of feints) finally directed “home” to the long-awaited D in mm. 217–19.The process of delay, from the initial adumbration of the cadence to its ultimate completion, has unfolded over an unprecedented span of 32 intensely involving measures, a passage full of finely calculated yet overwhelmingly powerful harmonic jolts and thrills.

The Toccata’s progress from this point to completion can be briefly summarized. In the section that follows Ex. 5-15c, the familiar cadential formula is used to navigate through a complete circle of fifths and beyond, to a cadence on A minor (iii). Over the next 62 measures, an almost identical harmonic process (dramatically extended by the use of the deceptive cadence) is used to establish G minor (ii). From there to the end it is just a matter of holding off the inevitable V–I that will complete the main cadential circle of fifths, and with it the piece. Once achieved, the dominant pedal is held for twenty-three measures while the hands on the manuals go through a frenzy of sequential writing that descends, ascends, descends again, and ascends again in ever-increasing waves. The pedal gives way to a series of cadential formulas that only reach the home key after yet another eruption, like the one in Ex. 5-15c, of the bizarre deceptive cadence to the “V of the Neapolitan,” a chord of crushing disruptive force that makes the final attainment of the tonic seem an inspiring, virtually herculean achievement.

of the Neapolitan,” a chord of crushing disruptive force that makes the final attainment of the tonic seem an inspiring, virtually herculean achievement.

The Toccata in F is thus a tour de force not only of manual (and pedal) virtuosity but of compositional virtuosity as well. Bach deserves enormous credit for sensing so early the huge emotional and dramatic potentialities of the new harmonic processes, and for exploiting them so effectively—at first, presumably, in thrillingly experimental keyboard improvisations of which the “composed” Toccata is the distilled residue. By harnessing harmonic tension to govern and regulate the unfolding of the Toccata’s form, he managed to invest that unfolding-to-completion with an unprecedented psychological import. Thanks to this newly psychologized deployment of harmonic functions—in which harmonic goals are at once identified and postponed, and in which harmonic motion is at once directed and delayed—“abstract” musical structures could achieve both vaster dimensions and a vastly more compelling emotional force than any previously envisioned. Harmonic tension could from now on be used at once to construct “objective” form and “subjective” desire, and to identify the one with the other.

The main protagonist and establisher of the three-movement soloistic concerto, as already mentioned, was Antonio Vivaldi, a Venetian priest who from 1703 to 1740 supervised the music program at the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, one of the city’s four orphanages. The word ospedale (cf. hospital), originally meant the same thing as conservatorio (whence “conservatory”); both were institutions that maintained and educated indigent children (orphans, foundlings, bastards) at public expense, and both emphasized vocational training in music. The Pietà housed only girls, and thanks to Vivaldi’s extraordinary talent and energy, its program was outstandingly successful. The Sunday vespers concerts performed by its massed bands and choirs of budding maidens under Vivaldi’s direction were regarded as something of a phenomenon and became one of the city’s major tourist attractions.

Travelers’ reports are split between those that emphasized the young performers’ allure, and those that emphasized the fiery demeanor of il prete rosso, “the red-haired priest” who presided, when present, with his violin at the ready. “There is nothing so charming,” wrote Charles de Brosses, a French navigator, “as to see a young and pretty nun in her white robe, with a sprig of pomegranate blossoms over her ear, leading the orchestra and beating time with all the grace and precision imaginable.”6 By contrast, Johann Friedrich Armand von Uffenbach, a German music patron who caught Vivaldi in action at the opera house, wrote that his playing “really frightened me.”7

Vivaldi’s official duties at the Pietà were the spur that caused him to produce concertos in such fantastic abundance. The most popular Venetian composer of opera and oratorio in his day, he was superbly prolific in those genres as well, and internationally famous. But it is with his five hundred surviving concertos (out of who can only guess how many composed?) that his name is irrevocably linked. About 350, almost three quarters, feature a single solo instrument, and of these about 230 (almost half the total) are for the violin, which was not only Vivaldi’s own instrument but the one taught to the largest number of girls at the Ospedale. Runner-up, with thirty-seven concertos, is (perhaps unexpectedly) the bassoon. There are also numerous concertos for flute, for oboe, for cello, and occasionally for rarer instruments, including some (like the mandolin and the “flautino” or flageolet) that were most often used in folk or street music—that is, by nonliterate musicians.

Some three hundred Vivaldi concertos are found today in unique manuscript copies, many of them autographs, housed since the 1920s in the National Library of Turin in northern Italy. They were deposited there by the musicologist Alberto Gentili, who tracked them down and purchased them for the library with funds provided by a local banker named Roberto Foà and a textile manufacturer named Filippo Giordano. These manuscripts had belonged to Count Giacomo Durazzo (1717–94), the Imperial (Austrian) ambassador to Venice, who later served as the “intendant” or impresario-in-charge of the Vienna opera. It is thought that he purchased the collection—either in Venice or in Vienna, where Vivaldi happened to die in 1741 while visiting on operatic business—intact from the composer’s estate, and that they represented the actual performing repertoire of the Pietà at the time of his death.

These are the concertos, in other words, that were expressly composed for the outstanding girl musicians—the figlie privilegiati, as they were called—whom Vivaldi trained and led. Published in the aftermath of World War II as a national treasure in a huge series of editions prepared by a leading Italian composer of the day, Gian Francesco Malipiero, these previously unknown Vivaldi concertos were a major spur to the so-called “postwar Baroque boom” that awakened active performing and recording interest in many forgotten repertories of “early music.” They thus have significance in the history of the twentieth century’s musical life as well as the eighteenth’s.

A concerto in C major for bassoon from the Foà deposit can serve as well as any (and better than most) in the somewhat imaginary capacity of “typical” Vivaldi concerto. It once carried the misleadingly low number 46 in the catalogue of Vivaldi’s works by Marc Pincherle, whose listing, once standard, was based on keys (starting with C); more recently it has carried equally misleading high number 477 in the catalogue of Peter Ryom, whose listings, based on instrumentation, are now supplanting Pincherle’s. In any case it well exemplifies the basic principles of concerto-writing that were à la mode in the early eighteenth century, largely because of Vivaldi’s commanding example.

Johann Joachim Quantz, a flutist and composer who in 1752 published (in the modest guise of a flute tutor) the most compendious encyclopedia of mid-eighteenth-century musical practice, called this type of concerto “a serious concerto with a large accompanying body” (the italics were his).8 What made it so was the nature of the ritornello, “majestic and carefully elaborated in all the parts,” in Quantz’s words, and containing a variety of melodic ideas. In its full form this complex ritornello functions as a frame, launching the movement and bringing it to an end, as in the main (“A”) section of a da capo aria. Elsewhere, as Quantz describes (or for any composers reading, prescribes), “its best ideas are dismembered and intermingled during or between the solo passages.”

The twelve-measure ritornello that introduces our bassoon concerto (Ex. 5-16) consists of four distinct melodic ideas. The first (mm. 1–4) is “spun out” of a turn figure and a rising third.The second (mm. 4–7) is a spaciously textured derivation from our old acquaintance the passus duriusculus, the chromatic descent from tonic to dominant degrees, presented not as a bass but as a treble line in the first violins, played against a bass consisting of ostinato repetitions of the opening turn figure. (Mentally connect the first and last notes in every group of four eighths in the first violin part and the chromatically descending line will emerge to the eye as clearly as it does in performance to the ear; the octave Gs in between double the viola’s “pedal.” This kind of “compound” melodic line, containing two registrally separated “voices” in one, was common in Italian string music and in later music, including a lot of Bach’s, that imitated it.) The third characteristic phrase in the ritornello (mm. 8–10) is marked by a radically contrasting texture, called all’unisono because it consists of unharmonized octaves. The fourth and last (mm. 10–12) is a cadential motive that (like the second phrase) makes a playful feint toward the parallel minor.

EX. 5-16 Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 1–12

If we label these component phrases for reference with the letters from A to D, we can easily compare the partial (or “dismembered”) internal repetitions of the ritornello with the full statement at opposite ends of the movement. In the first of them, the opening phrase (A) is balanced against a consequent phrase that telescopes truncated versions of B and D into a single four-bar span. The next internal ritornello consists of phrase A paired with phrase C, the one omitted in the previous statement. The next time, A is followed by fuller statements of B and D. The last internal ritornello is brief; it consists of nothing more than the second half of phrase B (in the major mode rather than the minor).

Each of these ritornellos is built on a different scale degree. Only the outer (full-blown) statements are based on the tonic; their harmonic stability reflects their important role in articulating the form of the piece. In between we get statements on V, vi, iii (the remotest point, articulated by the lengthiest internal ritornello), and (briefly) V again, providing a smooth “retransition” to the home key. The whole trajectory comprises a strongly directed tonal sequence embodying a characteristic “binary” or “round trip” motion: the initial swing to the dominant is prolonged through a deceptive cadence and a “regression” along the circle of fifths (that is, a move farther away from the tonic) before the dominant is picked up again and directed home: I–V–[vi–iii]—V–I.

Thus the sequence of ritornellos defines and unifies the structure of the concerto movement both melodically and tonally. In between come the solos, alternating not only with the ritornellos but with the “ripieni” or backup players who play them. In one sense—the public or “external” sense—the virtuosic solo turns are what the concerto is all about. It is the soloist one pays to hear, after all. In another sense—the structural or “internal” sense—the solos have a much less important role, merely providing modulatory transitions from one “tonicized” scale degree on which ritornellos are played to the next. They are the exact functional equivalent of the “episodes” between the expositions in a fugue.

In contrast to the ripieni, who are confined to repetitions (whether full or partial) of the ritornello, the soloist never repeats. Each episode (summarized in Ex. 5-17a-e) presents a new hurdle, progressively more challenging in its figuration: arpeggios, fast slurred scales, wide-leaping triplets, etc. Thus the typical concerto movement is a fascinating interplay of the fixed and the fluid: one body of players is confined to a single idea, while the other (here a group of one, plus continuo) is seemingly unconstrained in its spontaneous unfolding. One group only repeats, the other never repeats. One “role” is dramatically subordinate but structurally dominant, the other is dramatically dominant but structurally subordinate. Their effect together is one of complementation, of disparate parts fitting harmoniously into a satisfying, functionally differentiated whole, all of it grounded by the constant auxiliary presence of the basso continuo, everyone’s companion and aide.

All of this suggests a social paradigm or metaphor. Indeed, the concerto form has always been viewed, in one way or another, as a kind of microcosm, a model of social interaction and coordinated (or competitive) activity. That is one of the things that has always invested its seemingly abstract patterns with “meaning” and fascination for listeners. And that fascination, along with the fascination of tonal relations with their strong metaphorically “forward” drive to completion, is what allowed “large” forms of instrumental music to emerge and to assume a place of central importance in European musical culture.

EX. 5-17A Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 12–14

EX. 5-17B Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 30–25

EX. 5-17C Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 44–48

EX. 5-17D Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 162–165

EX. 5-17E Antonio Vivaldi, Concerto for Bassoon in C major, F VIII/13, mm. 74–78

The remainder of the concerto amplifies the sense of kinship with the opera seria. The broad (largo) second movement, scored for soloist and continuo alone, is a study in “florid” song (coloratura) over a static bass—a veritable aria d’affetto (or, more precisely, an arietta, in view of its binary form). The final movement, another ritornello-style composition, brings the ripieno back. Less “serious” than the first movement, it sports a ritornello theme with only two distinct parts and a pervasive all’unisono texture. As might be expected, the two halves of the theme are complementary or, more precisely, reciprocal. Tonally, they reproduce the functions of the binary form: the first phrase makes a half cadence on the dominant, the second a full cadence on the tonic. Melodically, too, the phrases are complementary. Both feature rushing scales, first ascending then descending. Taken as a three-part whole, the concerto reproduces in its texture the effect of a typical da capo aria: outer sections with ritornellos frame a contrasting middle section in which the soloist is accompanied by the continuo instruments only.

For an idea of Vivaldi not at his most typical but at his most bizarre or “frightening,” consider one of his most unabashedly extravagant compositions, the Concerto in B minor for four violins. Its only rival in excess might be the concertos “per l’orchestra di Dresda,” which Vivaldi wrote on order to show off the famous orchestra maintained by the Elector of Saxony Friedrich August II, whose titles included that of King of Poland, and who kept up a “royal” court in Dresden; this concerto had a colossal concertino consisting of six instruments: an especially showy violin part for the Elector’s “concertmaster” Johann Georg Pisendel, Vivaldi’s former pupil, along with two oboes, two recorders, and bassoon.