The story is told of King Louis XIV of France that once a courtier fond of the brilliance and grandeur of Italian music brought before the king a young violinist who had studied under the finest Italian masters for several years, and bade him play the most dazzling piece he knew. When he was finished, the king sent for one of his own violinists and asked the man for a simple air from Cadmus et Hermione, an opera by his own court composer, Jean-Baptiste Lully. The violinist was mediocre, the air was plain, nor was Cadmus by any means one of Lully’s most impressive works. But when the air was finished, the king turned to the courtier and said, “All I can say, sir, is that that is my taste.”1

Invoking taste, the thing that is proverbially beyond dispute, is always a fine way of putting an end to an argument, especially when invoked by one to whom nobody may talk back. But while a king’s taste may not be disputed, it may still be worth investigating. Nor can we say we really understand a story unless we know who is telling it, and why.

This particular story comes from a pamphlet, Comparaison de la musique italienne et de la musique française (“A comparison of French and Italian music”), issued in 1704 by one French aristocrat, Jean Laurent Lecerf de la Viéville, Lord of Freneuse, in answer to a like-named pamphlet, Paralèle des Italiens et des Français (“Differentiating the Italians from the French”), issued in 1702 by another French aristocrat, Abbé François Raguenet. It was the opening salvo of a press war that would last in France throughout the eighteenth century—that is, until the revolution of 1789 rendered all the old aristocratic controversies passé.

FIG. 3-1 Jean-Baptiste Lully, Superintendent of the King’s Music. Engraving by Henri Bonnart (1652–1711).

The reason why it enters into our story a little ahead of schedule, and why it was so very typical of France, is that the musician it defended had been dead for almost twenty years at the time of writing, and Cadmus, his second opera, had had its first performance more than thirty years before. Nowhere else in Europe had operas become classics, nor had any other composer of operas been exalted into a symbol not only of royal taste but of royal authority as well. Authority is what French music was all about, and Lully’s operas above all. They were the courtiest court operas that ever were.

Lurking behind the story, as behind every discussion of opera in France, was a political debate. It was touched off by Raguenet’s admiring description of castrato singing, probably the most vivid earwitness account ever penned of singers the likes of which we will never hear. Sometimes, wrote Raguenet (in the words of an anonymous eighteenth-century translator):

you hear a ritornello so charming that you think nothing in music can exceed it till on a sudden you perceive it was designed only to accompany a more charming air sung by one of these castrati, who, with a voice the most clear and at the same time equally soft, pierces the symphony of instruments and tops them with an agreeableness which they that hear it may conceive but will never be able to describe.

These pipes of theirs resemble that of the nightingale; their long-winded throats draw you in a manner out of your depth and make you lose your breath. They’ll execute passages of I know not how many bars together, they’ll have echoes on the same passages and swellings of a prodigious length, and then, with a chuckle in the throat, exactly like that of a nightingale, they’ll conclude with cadences of an equal length, and all this in the same breath.

Add to this that these soft—these charming voices acquire new charms by being in the mouth of a lover; what can be more affecting than the expressions of their sufferings in such tender passionate notes; in this the Italian lovers have a very great advantage over ours, whose hoarse masculine voices ill agree with the fine soft things they are to say to their mistresses. Besides, the Italian voices being equally strong as they are soft, we hear all they sing very distinctly, whereas half of it is lost upon our theatre unless we sit close to the stage or have the spirit of divination.2

And yet, Raguenet emphasizes, these desexed singers were not only the best male lovers, they were the best females as well:

Castrati can act what part they please, either a man or a woman as the cast of the piece requires, for they are so used to perform women’s parts that no actress in the world can do it better than they. Their voice is as soft as a woman’s and withal it’s much stronger; they are of a larger size than women, generally speaking, and appear consequently more majestic. Nay, they usually look handsomer on the stage than women themselves.3

To us, living in an age when sexual identity has become a “hot button,” Raguenet’s comfortable enjoyment of masculine cross-dressing is perhaps the most striking aspect of courts resplendent, overthrown, restored his description. It is a facet of a general comfort with artifice, and a willingness to accept all manner of make-believe, that contrasts strongly with more modern theatrical esthetics. But at the time the most provocative aspect of Raguenet’s discourse—and the one regarded as most potentially degenerate—was his ready receptivity to the purely sensuous pleasure of singing and his willingness to accept it as opera’s chief, most characteristic, and therefore most legitimate, delight. This went not only against the grain of Lecerf de la Viéville’s argument, which ends with strenuous exhortations to “yield to reason” and heed the admonitions that “reason pronounces for us” (that is, for us French)—it went against the whole history of operatic reception in France, and England too.

Opera had a difficult time getting started in France. Indeed, it had to succeed as politics before it had any chance of succeeding as art. Like their English counterparts, who also possessed a glorious tradition of spoken theater (as the Italians did not), the aristocrats of seventeenth-century France saw only a child’s babble in what the Italians called dramma per musica (drama “through” or “by means of” music). To their minds, the art of music and the art of drama simply would not mix. “Would you know what an Opera is?” wrote Saint-Evremond, an exiled French courtier and a famous wit, to the Duke of Buckingham.4 “I’ll tell you that it is an odd medley of poetry and music, wherein the poet and musician, equally confined one by the other, take a world of pains to compose a wretched performance.” Music in the theater, for the thinking French as for the thinking English, was at best an elegant bauble, more likely a nuisance. High tragedians made a point of spurning it. Pierre Corneille, the greatest playwright of mid-century France, would admit music only into what was known as a pièce à machines—a play that already adulterated its dramatic seriousness for the sake of spectacle in the form of flying machines on which gods descended or winged chariots took off. And even then, he wrote in 1650 in the preface to his drama Andromède, “I have been very careful to have nothing sung that is essential to the understanding of the play, since words that are sung are usually understood poorly by the audience.”5 But then artists and critics who value intellectual understanding have always resisted opera. From the beginning dramatic music has been reason’s foe, as indeed it was expressly designed to be.

The irrational, though, can have its rational uses, and nobody knew that better than Jules Mazarin, the seventeenth century’s most artful politician. It was Cardinal Mazarin (né Giulio Mazzarini), the Italian-born de facto regent of France, who took the first steps, in the earliest years of the boy-king Louis XIV’s reign, to establish opera in his adopted country. He recruited the services of Luigi Rossi (ca. 1597–1653), the leading composer of Rome, to write an opera expressly for the French court. Fittingly, indeed all but inevitably, this first officially sponsored French opera, performed at the Palais Royal on 2 March 1647, was another Orfeo, another demonstrative setting of the myth of music’s primeval power to move the soul.

Forty years after Monteverdi’s treatment of the same tale, the new work showed the influence of opera’s commercial popularization, so that it resembled Monteverdi’s Poppea more than it did his Orfeo. Where Monteverdi’s Orfeo had only the briefest of duets for Orpheus and Eurydice (to celebrate their happiness, not express their love), Rossi’s gave the nuptial pair (both sopranos) no fewer than three extended love scenes. Orpheus, a natural tenor in Monteverdi’s setting, is a soprano castrato in Rossi’s, so that these scenes closely resemble the ones for Nero and Poppea in Monteverdi’s last opera. Also in the spirit of Poppea rather than Monteverdi’s Orfeo, Rossi’s Orfeo has a pair of comic characters (one of them a satyr) who mock the lofty passions of the main characters.

But like Monteverdi’s Orfeo, and like all the early aristocratic musical tales, Rossi’s Orfeo was fitted out with sumptuous scenery, with dancing choruses, with lavish orchestral scoring and with machines (the most splendid one reserved for Apollo, who descends in a fiery chariot that illuminates a fantastic garden set). Above all, it had the requisite sycophantic prologue that showered praises on the young King Louis from the mouths of gods and allegorical beings.

By masterminding this display, Cardinal Mazarin secured for himself a prestige that rivaled that of his own mentor, the Roman cardinal Antonio Barberini, Rossi’s patron. The Italian spectacles, full of everything merveilleux, bedizened the French court more gloriously than any rationalistic drama could do, for “the purpose of such spectacles,” wrote the moralist Jean de la Bruyère (1645–96), a court favorite and a converted operatic skeptic, “is to hold the mind, the eye and the ear equally in thrall.”6

And there was something else as well. Rossi, in his turn, recruited for his performances a troupe of Roman singers and instrumentalists, a little colony of Italians in the French capital who were personally loyal to Mazarin, and who, in the time-honored fashion of traveling virtuosi, could serve him as secret agents and spies in his diplomatic maneuvers with the papal court. All of this was a lesson to Mazarin’s apprentice, the young king, who thus received instruction, as a French historian has put it (using the French word for lavish arts patronage), in “the political importance of le mécénat.”7 The foundations were laid for what the French still call their grand siècle, their great century, and opera was destined to be its grandest manifestation.

Yet it was a very special sort of opera that would reign in France, one tailored to accommodate national prejudices, court traditions, and royal prerogatives. The French autocracy was the largest ethnically integrated political entity in Europe. Its royal court was the exemplary aristocratic establishment of the day, and its musical displays would classically embody the politics of dynastic affirmation. Like every other aspect of French administrative culture, the French court opera was wholly centralized. Its primary purpose was to furnish “propaganda for the state and for the divine right of the king,” as the music historian Neal Zaslaw has written, and only secondarily to provide “entertainment for the nobility and bourgeoisie.”8 No operatic spectacle could be shown in public anywhere in France that had not been prescreened, and approved, at court.

At the same time, however, French opera aimed far higher than the “musical tale” of the Italians, which was essentially a modest pastoral play. The French form aspired to the status of a full-fledged tragédie en musique (later called tragédie lyrique), which meant that the values of the spoken drama, France’s greatest cultural treasure, were as far as possible to be preserved in the new medium despite the presence of music.

To reconcile the claims of court pageantry with those of dramatic gravity was no mean trick. Only a very special genius could bring it off. At the time of Luigi Rossi’s momentous sojourn in France, another far less distinguished Italian musician—just an apprentice, really—was already living there: Giovanni Battista Lulli, a Florentine boy who had been brought over in 1646, aged thirteen, to serve as garçon de chambre to Mme. de Montpensier, a Parisian lady who wanted to practice her Italian. She also supported his training in courtly dancing and violin playing. When his patroness, a “Frondist” (that is, a supporter of a failed parliamentary revolt against Louis and Mazarin), was exiled in 1652, Lulli secured release from her employ and found work as a servant to Louis XIV’s cousin, Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orleans (known as the “Grande Mademoiselle”), and as a dancer and mime at the royal court, where he danced alongside, and made friends with, the teenaged king. Upon the death of his violin teacher the next year, Lulli assumed the man’s position as court composer of ballroom music.

His rise to supreme power was steady and unstoppable, for Lulli was a veritable musical Mazarin, an Italian-born French political manipulator of genius. Shortly after the founding in 1669 of the Académie Royale de Musique, Louis XIV’s opera establishment, Jean-Baptiste Lully, who like Mazarin had been naturalized and Gallicized his name, managed to finagle the rights to manage it from its originally designated patent holder. From then on he was a musical Sun King, the absolute autocrat of French music, which he re-created in his own image.

He had a crown-supported monopoly over his domain, from which he could exclude any rival who threatened his preeminence. He squeezed out his older, native-born contemporary Robert Cambert (ca. 1628–77), who, despairing of ever producing his masterpiece, Ariane (1659), withdrew embittered to London where in 1674 he did finally see a much-modified version of it performed in Drury Lane to a partially translated libretto. Likewise Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643–1704), a younger competitor who, though trained in Italy and employed by the king’s cousin and later by the dauphin (the future Louis XV), had to wait until the age of fifty before he could get a tragédie en musique (Medée, 1693) produced at court, several years after Lully’s long-awaited death in 1687. (The old monopolist had died with his boots on, so to speak, following a celebrated mishap with a time-beating cane that resulted in gangrene.) By then Lully had produced thirteen tragédies lyriques, averaging one every fifteen months. The pattern that he set with them became the standard to which any composer aspiring to a court performance had to conform. Two generations of French musicians thus willy-nilly became Lully’s dynastic heirs. His works would dominate the repertory for half a century after his death, in response not to market forces or to public demand but by royal decree, giving Lully a vicarious reign comparable in length of years to his patron’s and extending through most of the reign of Louis XV as well. His style did not merely define an art form, it defined a national identity. La musique, he might well have said, c’est moi.

The ultimate theatrical representation of power, the Lullian tragédie lyrique was from first to last a sumptuously outfitted—but, in another sense, quite thinly clad—metaphor for the grandeur and the authority of the court that it adorned. The monumental mythological or heroic-historical plots, some chosen by the king himself, celebrated the implacable universal order and the supremacy of divine or divinely appointed rulers.

Themes of sacrifice and self-sacrifice predominated. Lully’s Alceste (1674), his second tragedie lyrique and one of his most successful, was based on the myth of Alcestis (as embodied in Euripides’ tragedy of the same name), about a queen who gives up her life so that her husband’s life-threatening malady may be cured. The adaptation was by Philippe Quinault (1635–88), a court poet and member of the Académie Française, who became Lully’s principal librettist. (The same Euripides tragedy would serve about ninety years later as plotline for a similarly lofty, French-style libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi, a Vienna court poet, austerely set to music by the great opera reformer Christoph Willibald von Gluck to honor the Empress Maria Theresa for her devotion to her consort, who had died the year before.)

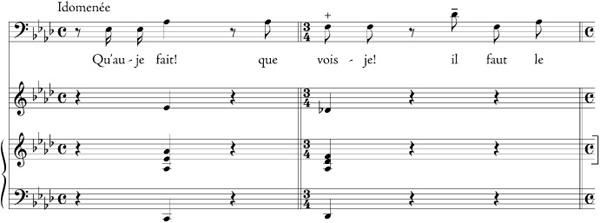

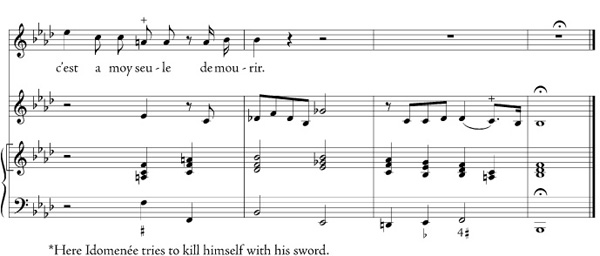

Idomenée (1712), a tragédie en musique by André Campra, a member of the post-Lully generation, concerns Idomeneus, the king of Crete during the Trojan Wars, who makes a hasty vow to Neptune to sacrifice the first living thing he espies on returning home in return for deliverance from a shipwreck, and is forced to sacrifice his own son at the cost of his throne and his sanity. (Its libretto, based on a fourth-century commentary to Virgil’s Aeneid, was later translated, revised, and expanded for Mozart’s Idomeneo, performed for the court of Munich in 1781.) Later, the almost identical biblical story of Jephtha (already the subject of an oratorio by Carissimi described in chapter 2), who makes a similar vow and suffers a similar fate, was turned into a tragédie en musique by Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (Jephté, 1732). By then, tastes had changed sufficiently to permit a happy ending: Jephtha’s daughter is spared in Montéclair’s opera by divine intervention. Lully’s greatest successor, Jean-Philippe Rameau, honored Louis XV with Castor et Pollux (1737), concerning the mythological twins, immortalized in the constellation Gemini, who were each tested and found willing to sacrifice his life for the sake of the other.

FIG. 3-2 Illuminated evening performance of Alceste, a tragédie en musique by Lully and Quinault, at the Marble Court of Versailles, 1674. Engraving by Jean Le Pautre (1618–1682).

FIG. 3-3 Jean-Philippe Rameau, portrait by Jacques Aved (1702–1766).

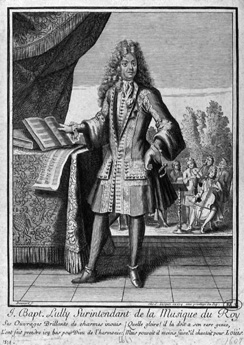

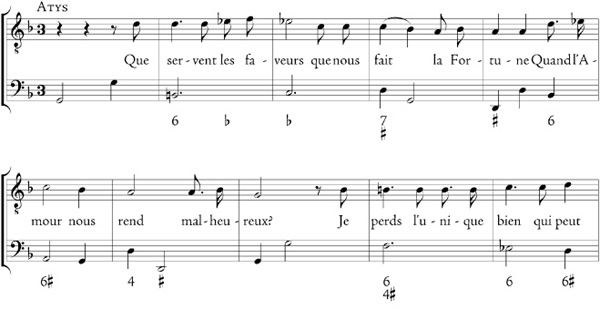

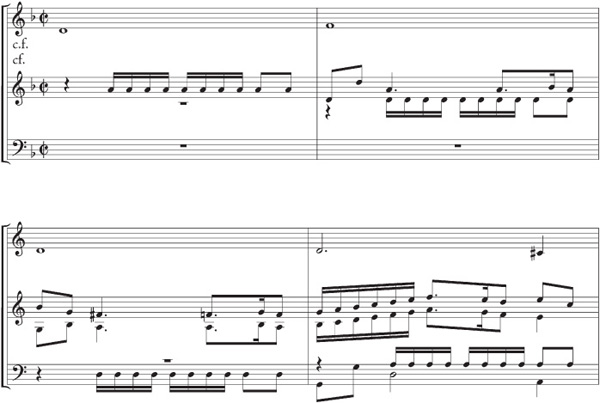

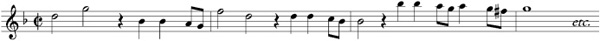

A metaphor of grandeur and authority from first to last, beginning with the marchlike ouverture or “opener” whose stilted dotted rhythms (enclosing a faster jiglike fugue) became for eighteenth-century composers—and even later ones—a universal code for pomp. The “French overture” was actually Cambert’s invention, in his pastorale Pomone (1671), performed a year before Lully managed to secure the royal patent and ruin his rival, meanwhile taking over all his stylistic innovations and expanding them into their “classic” form. Ex. 3-1 shows the beginnings of the two main sections of the ouverture to Lully’s opera Atys of 1676.

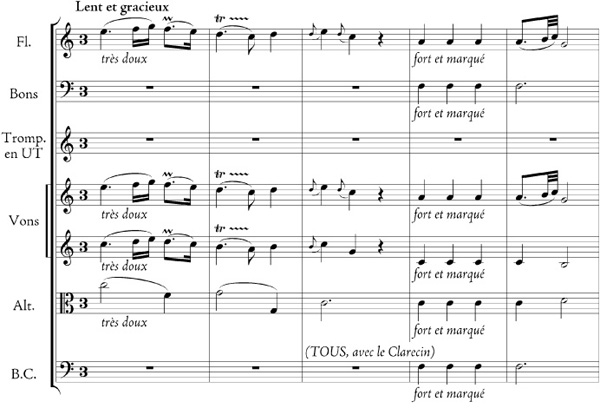

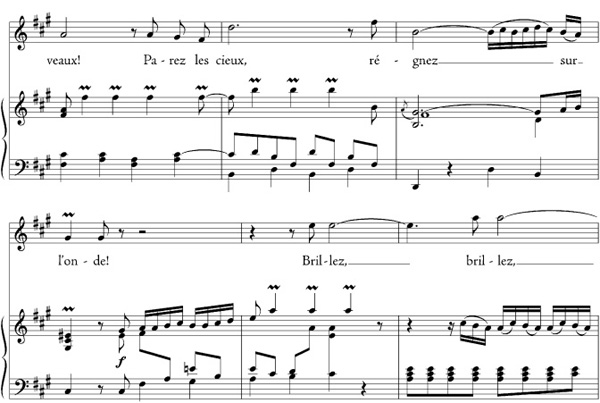

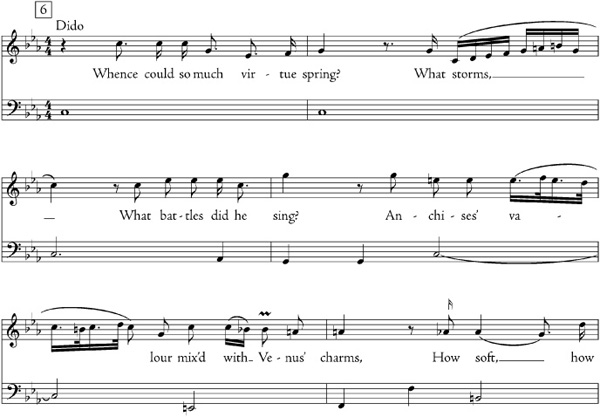

What the ouverture served to introduce was an obligatory panegyric prologue of a full act’s duration, vastly outstripping its Italian courtly prototype. Here mythological beings were summoned to extol the French king’s magnificent person and his deeds of war and peace with choral pageantry and with suites of dances modeled on the actual ballet de cour, an elaborate ritual, in which the king himself took part, that symbolized the divinely instituted social hierarchy. (A description of “the King’s Grand Ball” by Pierre Rameau, Louis XV’s dancing master, may be found in Weiss and Taruskin, Music in the Western World, No. 54.) At times the mythological characters could be joshed a little, as in Rameau’s Castor et Pollux, where Louis XV’s successful mediation of the War of Polish Succession is symbolized textually by an amorous concord of Venus and Mars, the gods of love and war, and musically by a delightfully incongruous love duet of flute and trumpet that only Rameau, a master of the grotesque, could have brought off (Ex. 3-2); or as in Montéclair’s Jephté, where Roman deities scurry out of the way of the Holy Scripture. Such levity was tolerable in a prologue, for it only enhanced the exaltation of the king above his mythological admirers.

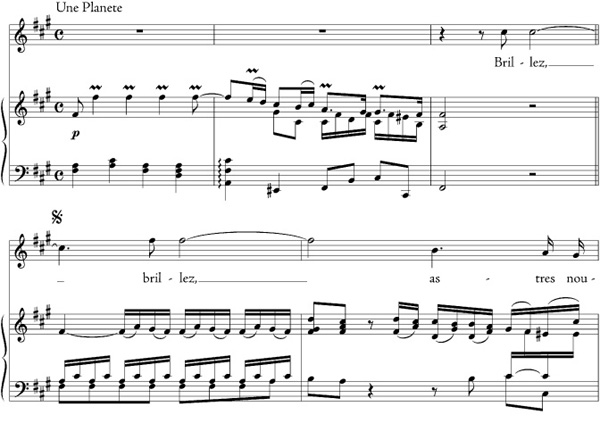

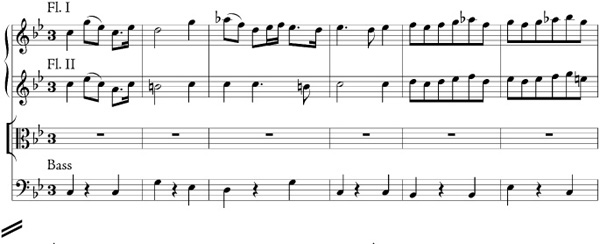

EX. 3-1A Jean-Baptiste Lully, Overture to Atys (1676), opening section

EX. 3-1B Jean-Baptiste Lully, Overture to Atys (1676), beginning of middle section

EX. 3-2 Jean-Philippe Rameau, Castor et Pollux, Prologue

Throughout the spectacle that followed, dancing—ceremonial movement accompanied by les vingt-quatre violons du Roi (“the twenty-four royal fiddlers”), the grandest and most disciplined orchestra in Europe—would furnish a lavish symbolic counterpoint to the words. Sometimes the dance enlarged directly on the dramatic action, sometimes it contrasted with it, as when Jupiter, in the second act of Castor et Pollux, orders up a lengthy divertissement or dance-diversion just to show his errant son what pleasures he will have to give up if he goes through with his planned self-sacrifice.

Everything reached culmination in a monumental chaconne or passacaille, a stately choral dance over one of the ground basses described in chapter 2. It often went on for hundreds of measures, enlisting all the dramatis personae for the purpose of announcing an explicit moral. “C’est la valeur qui fait les Dieux/Et la beauté fait les Déesses” (“Valor makes gods and beauty goddesses”) is the one proclaimed in Castor et Pollux; and the metaphorical signifance of the final dance is spelled out with special clarity in that opera. “C’est la fête de l’univers!” (“Let the whole universe rejoice!”), Jupiter declares, and his words are taken up as a refrain by the ensemble, representing all the planets and the stars in the sky in an orgy of royal panegyric.

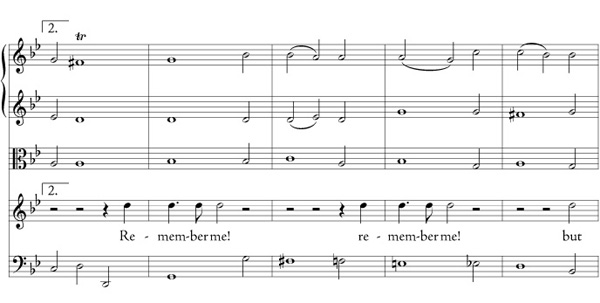

The champion Lully passacaille comes from the fifth act of Armide (1686), his last tragédie en musique, composed to a libretto adapted by Quinault at Louis XIV’s behest from a celebrated episode in Tasso’s 1581 epic Gerusalemme liberata concerning the love of Armida, a Saracen sorceress, for Rinaldo, a crusader, culminating in her conversion and her renunciation of pagan vengefulness in favor of Christian humility and conciliation. (The story became the subject of close to one hundred operas and ballets, from Monteverdi in the early seventeenth century to Dvo ák in the early twentieth.) The work was kept in repertory until 1766, eighty years after its première—a record run, not to be matched till Mozart, whose late operas never left the standard repertory.

ák in the early twentieth.) The work was kept in repertory until 1766, eighty years after its première—a record run, not to be matched till Mozart, whose late operas never left the standard repertory.

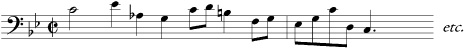

FIG. 3-4 Destruction of the magic palace at the conclusion of Lully’s Armide (1686). Stage design for the original production by Jean Berain.

The passacaille (Ex. 3-3), which if performed complete (that is, with all repeats observed) lasts upwards of twelve minutes, comprises a divertissement performed by a troupe of allegorical Pleasures and amants fortunés (happy lovers) to entertain Renaud (Rinaldo) while Armide seeks advice from the Underworld on what to do about her love-sickness. The fact that it is based largely on the traditional descending minor tetrachord (occasionally garnished chromatically into the passus duriusculus) is a tip-off to the audience that things will not end as happily as they did in Tasso’s original, but with a denouement better suited to the requirements of the French court and its mores. And sure enough, when Armide returns Renaud surprises her with the declaration that he will sacrifice love to duty and leave her; Armide, enraged, humiliated, and despairing, orders the destruction of her magic palace (and Renaud within it) then departs on a flying chariot. Thus Renaud, the true hero of the tale (and the royal patron’s surrogate) ends up sacrificing not only love but life itself on the altar of social obligation.

EX. 3-3 Jean-Baptiste Lully, Armide, Passacaille, beginning

The contemporary allegorical relevance of the plot, proclaimed at the first in the prologue and affirmed at the last by the passacaille, was what really counted in a tragédie lyrique. To drive it home the players wore “modern dress,” adapted from contemporary court regalia, just as the dances they performed were the sarabandes, the gavottes, and the passepieds of their own ballroom, albeit performed at a supreme level of execution. Thus the theatrical pageant was no mere reminiscence of a social dance, it was a social dance enacted by professional proxies. The whole drama was conceived as a sublimated court ritual. Royal and noble spectators did not seek transcendence of contemporary reality but rather its cosmic confirmation. They did not value the kind of verisimilitude that makes the imaginary seem real. They wanted just the opposite: to see the real—that is, themselves—projected into the domain of fable and archetype.

Along with this feast of symbolic movement and rich sonority went an unparalleled, completely un-Italianate prejudice against virtuoso singing, which was abjured not only for the usual negative reasons—uppity singers symbolizing a polity in disarray—but for more positive reasons having to do with the theatrical traditions of France. Here verisimilitude of a very particular sort—fidelity to articulate language, which is the first thing to go in florid, legato, “operatic” singing—suddenly loomed very large. The lead performers in French court opera remained nominally acteurs, and the voice of the castrato went unheard in the land—even when, in Lully’s Atys (1676), after Ovid, the plot actually hinged on castration.

But of course the brave castrato voice referred to anything but itself. The one thing its brassy timbre never symbolized was actual eunuchhood. And so the last character a castrato might have effectively represented was Atys, or Attis, the hero of the ultimate courtly sacrifice-spectacle, known in its time as “the king’s opera” and cited not only as an operatic but as a literary classic by Voltaire, seventy-five years after its first production.9 Attis was a god of pre-Hellenic (Phrygian) religion, later taken over as a minor deity by the Greeks. Like Adonis, he was a beautiful youth over whom goddesses fought jealous battles. Cybele, the earth or mother goddess, fell in love with the unwitting and insouciant Attis, and so that none other shall ever know his love, caused him to castrate himself in a sudden frenzy. Like Adonis, he was worshiped by the Greeks as a god of vegetation who controlled the yearly round of wintry death and vernal resurrection.

In Quinault’s libretto, Cybele’s rival for the love of Attis is the nymph Sangaride, to whom Attis has actually declared his affections. At the end of the opera, Cybele causes Attis to kill Sangaride in his frenzy, and then to stab himself fatally. Before he can die, Cybele transforms him into a pine tree whose life is renewed yearly, so that she will be able to love it forever. According to a gossipy courtier who authored several highly revealing letters about the preparations for the Atys première and about the staging, this ending was contrived expressly so as to avoid having to show an act of castration on stage. The very avoidance, however, testified to everyone’s awareness of the real nature of the hero’s sacrifice and lent an added resonance to the contemporary subtext, no doubt well known to Lully and Quinault: “Word has it,” one of the letters divulges, “that the King recognizes himself in this Atys, apathetic to love, that Cybele strongly resembles the Queen, and Sangaride Mme. de Maintenon, who enraged the King when she wanted to marry the Duke of B****.”10

In other words, the opera gave symbolic representation to a love triangle that was even then being played out in the king’s own household; for “Mme. de Maintenon” (that is, Françoise d’Aubigné, marquise de Maintenon), the widow of a court poet and an influential royal adviser, became the second wife of Louis XIV in 1684. No wonder Atys became known as “the king’s opera.” It was, even beyond the obligatory prologue, an opera about the king. And in its famed artistic “chastity”—(almost) no comic interludes, (almost) no subplots, in short (almost) no popular “Venetian” trappings of any kind—Atys reflected on the artistic plane the same tendency toward serenity and exalted moderation that Mme. de Maintenon advocated in court life.

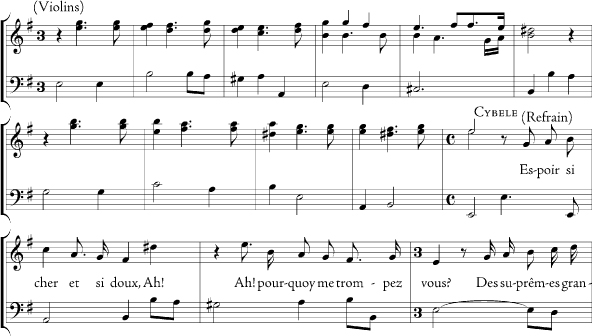

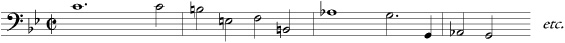

The third act of Atys, at once the most succinct of the opera’s five acts and the most varied, is a perfect model of courtly opera at the peak of its prestige. It begins with a short soliloquy for the title character, cast as an haute-contre, the highest French male voice range, a soft tenor shading into falsetto and the very antithesis of the plangent castrato (Ex. 3-4a). Atys laments the loss of Sangaride to her betrothed, King Celenus of Phrygia. This little number epitomizes Lully’s deliberate avoidance of big Italianate vocal display in the interests of dramatic realism; as the anonymous letter writer describes it, “all in half-tints: no big effects for the singers, no grand arias, but small courtly airs and recitatives over the bare continuo, and their alternation is what will give shape to the action.”

EX. 3-4A Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Atys’s opening air (sarabande)

Atys’s solo is just such a “courtly air” (air de cour). The text consists of a single quatrain, of which the first pair of lines (couplet) is used as a refrain to round it off into a miniature ABA (da capo) form. This little rounded entity is further enclosed between a pair of identical ritournelles, in which the first measure already discloses the characteristic meter and rhythm of the sarabande. Thus even the vocal solos reflect the underlying basis of the French court opera in the court ballet, and beyond that, in ballroom dance itself. The setting of the text is entirely syllabic and responsive to the contours, stresses, and lengths of the spoken language, reflecting the other underlying basis of the court opera, namely high-style theatrical declamation.

These values were hard-won. They ran counter to “musicianly” instincts, and Lully’s famous skills as autocratic disciplinarian, with unprecedented authority stemming directly from his patron the king, were necessary ones to the success of his undertaking—as the anonymous letter writer confirms in a delightfully written, somewhat cynical passage that conjures up a vivid sense of something new in music: haughty, easily offended authorial pride.

Lully is ranting at everybody. Everyone wants to shine in Atys, and there is no way to shine in this work of Lully’s. Everything is fashioned, calculated, measured so that the action of the drama progresses without ever slackening. This singer takes it upon himself to add ornaments, slowing down the beat; and in order to remain on stage longer and arouse a little more applause, drags out an air that Lully intended to be simple, short and natural. That dancer begs for a futile repetition; the violins want to play when Lully asks for flutes…. Everybody seeks his own reflection in Atys. Lully has to defend his work.11

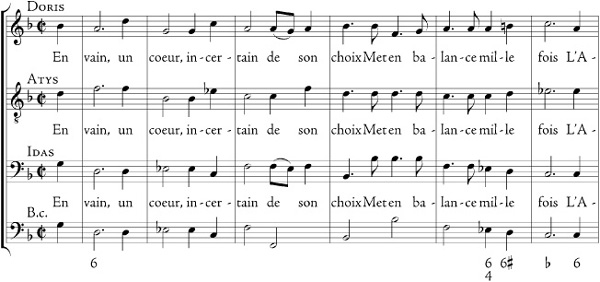

After Atys’s solo, the nymph Doris and her brother Idas enter to urge Atys to act on his passion and spurn his official duty as Celenus’s protégé and chief sacrificer to Cybele, thus crystallizing the moral dilemma on which the drama turns. Like most scenes of dialogue, it is carried by a rhythmically irregular recitative that alternates between measures containing four big beats and measures containing three. But when the two confidants come to their principal argument (“In love’s realm duty is helpless”), they come together in another minuscule air in minuet tempo, into which (and out of which) they slip almost imperceptibly: that is the deft “alternation that shapes the action,” in the words of the anonymous letter writer. And when they win Atys over, he joins them in a tiny trio in the style of an allemande with dotted rhythms recalling the imperious strains of the overture (Ex. 3-4b).

EX. 3-4B Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Air à trois (allemande)

In vain, a heart, uncertain of its choice, puts Love and gratitude a thousand times upon the scales. Love always tips the scales.

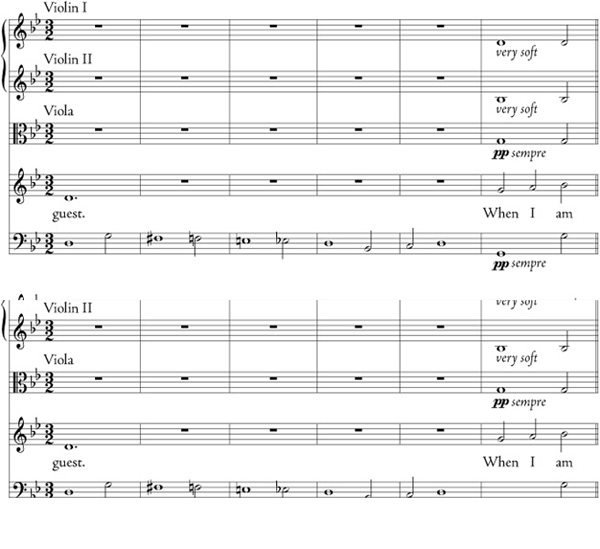

Left alone once again to reflect on his amorous prospects, Atys launches what appears to be another sarabande, heralded by another orchestral ritournelle. (Its giveaway rhythm is the accented and lengthened note on the second beat of the measure.) But he is quickly distracted by the counterclaim of duty and lapses into a recitative, from which he lapses further into sleep. This is an enchanted slumber that Cybele has engineered in order to apprise him of her love without having to confess it (degrading for a goddess). The scene thus conjured up is the most famous scene in the opera—the subtly erotic Sommeil, literally the “sleep scene” or “dream symphony,” so widely copied by later composers and librettists that it became a standard feature of the tragédie lyrique.

FIG. 3-5 Costume design by Jean Berain for the Sommeil (“sleep scene”) in Lully’s Atys (1676).

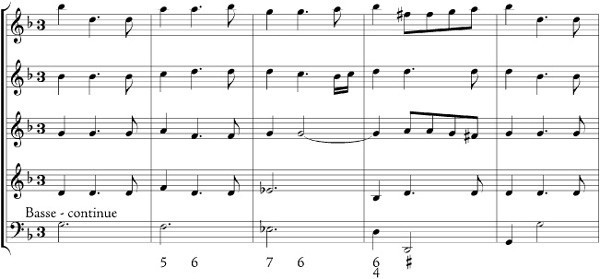

It begins with a Prelude (Ex. 3-4c) in which soft, sweet-toned whistle-flutes (what the French simply called flûtes, or recorders in English) are spotlighted in a somewhat concerto-like dialogue with the string band. The rocking rhythms, slurred two-by-two and surely performed with the characteristic French lilt (the so-called notes inégales), literally cradle the entranced title character and serve as the prologue to a charmed vision of Sleep himself (haute-contre), who sings a hypnotic refrain in alternation with his sons Morpheus (another haute-contre), Phobétor (bass), and Phantase or “Dream” (tenor).

EX. 3-4C Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Sommeil

Morpheus’s short recitative, in which he informs Atys that he has the honor (or in view of the outcome, the curse) of being loved by the exalted Cybele, introduces a typical process of alternating recitatives and accompanied airs with refrains, the chief refrain being the quatrain sung by the three sons of Sleep that continually reminds Atys that Cybele’s love exacts duty and constancy in return. Exhortations give way to a ballet of sweet dreams (des songes agréables), in which the minuet danced by the corps de ballet forms a refrain to alternate with that of the sons.

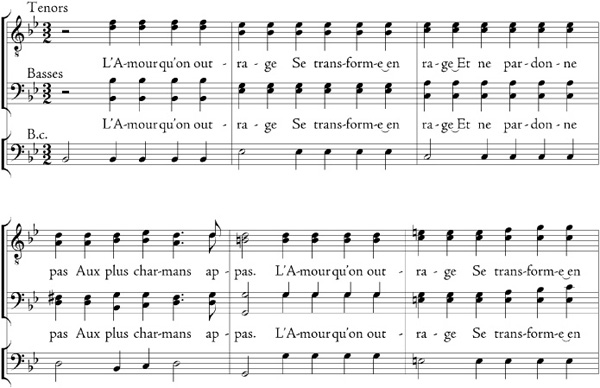

The ballet of the sweet dreams is suddenly disrupted by one of nightmares (songes funestes or “evil dreams”), who enter, heralded by a bass who warns against offending a divine love, to the strains of an allemande in pompous overture style, its regal rhythms reflecting the high station of the goddess at whose behest the nightmares have appeared. The chorus of evil dreams that follows (Ex. 3-4d) is in one of Lully’s specialty styles: the rapid-fire “patter chorus,” which reached its peak the next year with the chorus of “Trembleurs”—People from the Frozen Climates whose bodies quake and whose teeth chatter with the cold—in Lully and Quinault’s pastoral Isis. Having sung, the evil dreams launch into a lusty courante, full not only of the usual hemiolas but of rattling military tattoos as well. The nightmare sequence is dispelled by the awakening of the startled Atys and the arrival of Cybele herself, who comforts him, distressed though she is to learn, through an exchange of minuscule airs, that Atys properly reveres her but does not return her passion. Sangaride enters for a long scene in recitative that encloses the drama’s (would-be) turning point, when Cybele (alas, only temporarily) promises to aid her rival out of unselfish love for Atys. Her crucial decision is rendered as a maxim: “The gods protect the freedom of the heart,” set as a tiny march or allemande for the goddess, immediately repeated by the mortal pair.

EX. 3-4D Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Choeur des Songes Funestes

Love insulted turns to fury and won’t forgive the most charming appeal.

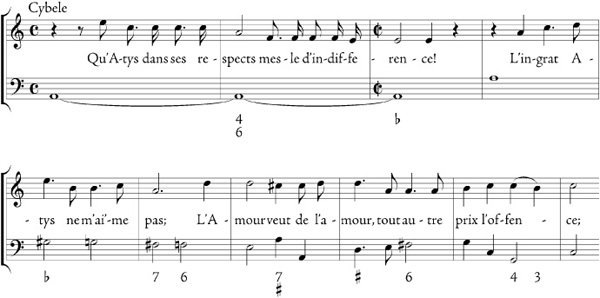

Sangaride and Atys exit to seek the aid of Sangaride’s father, the river Sangarus. (His scene, in act IV, is the opera’s one comic divertissement.) Cybele’s confidant, the priestess Melissa, now enters to console the unhappy goddess, whose complaint that “the ungrateful Atys loves me not” is set against the all-but inevitable passus duriusculus, the chromatically descending tetrachord, in the continuo (Ex. 3-4e). She sings in recitative style throughout, while Melissa’s attempts to console her take the form of petits airs (little songs without repeats), the first of them a gavotte (Ex. 3-4f), identifiable by its characteristic two-quarter upbeat in quick “cut time” (two half notes to the bar).

EX. 3-4E Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Cybele’s complaint

How doth Atys mix indifference with respect! The ungrateful wretch loves me not; Love demands love, any substitute is an offence.

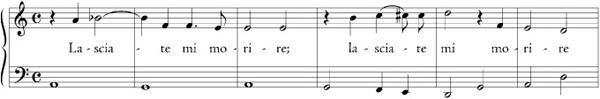

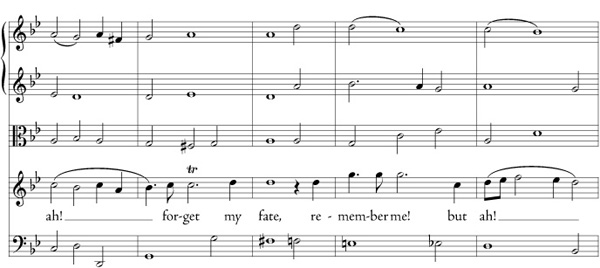

Finally, Melissa leaves Cybele alone on stage and the goddess delivers herself of an impassioned yet dignified lament, the most extended solo turn in the opera. Impassioned though it is, however, it is far from what one would expect from a contemporary Italian opera at such a point. Rather, it harks back directly to such masterworks of the early, courtly Italian style as Monteverdi’s famous lament for Ariadne—Lully surely knew it—in the otherwise lost opera Arianna of 1608, named for her (Ex. 3-4g). Introduced and concluded by a ritournelle in an elegiac sarabande style, Cybele’s lament (Ex. 3-4h), like Ariadne’s, is a recitative built around a three-fold textual and musical refrain: “Hope, so cherished, so sweet, Ah, … ah, why dost thou deceive me?” Between the two consecutive “Ahs,” Lully inserts a quarter rest, called a soupir (“sigh”) in French, on the downbeat. (A teaser: Was the rest called a sigh because it was used like this, or did Lully use it like this because it was called a sigh? The history of the term is not well enough established to answer the question, but it raises the prospect that even the most obviously “onomatopoietic” or “iconic” musical imitations are actually mediated through language concepts and are, in effect, puns.)

EX. 3-4F Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Melissa’s petit air (gavotte)

It is not so great a crime to express oneself poorly; A heart that has never loved knows little about how love is expressed.

EX. 3-4G Claudio Monteverdi, Lamento d’Arianna, refrain

EX. 3-4H Jean-Baptiste Lully, Atys, Act III, Cybele’s lament (sarabande)

As we see from the third act of Atys, French singing actors were rarely if ever called upon to contend with the full orchestra. Their scenes and confrontations were played against the bare figured bass in a stately, richly nuanced recitative whose supple rhythms in mixed meters caught the lofty cadence of French theatrical declamation. Lully, for whom French was a second language, was said to have modeled this style directly on the closely observed delivery—the contours, the tempos, the rhythms and the inflections—of La Champmeslé (Marie Desmares, 1642–98), the leading tragedienne of the spoken drama, who created most of the leading roles in the works of the great dramatist Jean Racine. Racine personally coached her, and thus indirectly coached Lully, whose tragédies en musique were exactly contemporaneous with Racine’s great tragedies for the legitimate stage. Cybele’s concluding lament in act III of Atys was an obvious instance of this musicalized tragic declamation.

Roulades and cadenzas would only have marred this lofty style, but Lully’s singers employed, as if in compensation, a rich repertoire of “graces” or agrémens: tiny conventional embellishments—shakes, slides, swells—that worked in harness with the bass harmony to punctuate the lines and to enhance their rhetorical projection. And there were all kinds of subtly graded transitions in and out of the petits airs, the tiny, simply structured couplets and quatrains set to dance rhythms, which animated the prosody while placing minimum barriers in the way of understanding.

This, then, was the perfect opera for snooty opera haters like Saint-Evremond: an eyeful of spectacle, one ear full of opulent instrumental timbre, the other ear full of high rhetorical declamation. Vocal melody was far from the first ingredient or the most potent one, and the singers were held forcibly in check. Vocal virtuosity was admitted only in a decorative capacity on a par with orchestral color and stage machinery, never as a metaphor for emotion run amok. For passions out of control, the title character’s harrowing final mad scene in Campra’s Idomenée marked the absolute limit (Ex. 3-5). The tragic agitation is conveyed by brusque orchestral roulades, not vocal ones, and by the use of extreme tonalities, whose timbres were darkened by lessened string resonance, and whose unfamiliar playing patterns and vocal placements caused the performers to strain.

EX. 3-5 André Campra, Idomenée, from the final mad scene

By contrast, virtuoso singing could only emanate from the lips of anonymous coryphées: soloists from the general corps, representing members of the crowd, shades, athletes, even planets—whatever the dramatic or allegorical circumstances required. The singing planet in Ex. 3-6—a brilliant ariette to greet a new heavenly constellation—is from Rameau’s Castor et Pollux, part of the fête de l’univers decreed by Jupiter. It embodies a kind of singing otherwise uncalled for in the opera—one that, while eminently theatrical, is essentially foreign to the dramatic purposes of the tragédie lyrique and therefore only suitable for an undramatic ornamental moment in a divertissement.

The resplendent general impression to which this coldly dazzling ariette contributed took precedence over the personality of any particular participant. The concert of myriad forces in perfect harness under the aegis of a mastermind was the real message, whatever the story. While even the prejudiced Saint-Evremond had to admit that “no man can perform better than Lully upon an ill-conceived subject,” he turned it into a barb: “I don’t question but that in operas at the Palace-Royal, Lully is 100 times more thought of than Theseus or Cadmus,” his mythological heroes. But that was all right, since the king was even more thought of than Lully.

EX. 3-6 Jean-Philippe Rameau, Castor et Pollux, ActV, ariette, Brillez, brillez astres nouveaux

Rameau’s planetary ariette shows the influence of a later Italian style than Lully could have known. (We will give it fuller consideration when we turn to the operas of Alessandro Scarlatti and George Frideric Handel.) In a sense it belongs to another age; but although Rameau is obviously later than Lully, and novel enough to have inspired resistance, he is not essentially different; and that is important to keep in mind. The eighteenth-century philosopher Denis Diderot had it right when he called Lully Monsieur Ut–mi–ut–sol (C–E–C–G)—roughly, “Mr. Music”—but called Rameau Monsieur Utremifasollasiututut (CDEFGABCCC)!12 For the Rameau style was the Lully style advanced—in no way challenged, but intensified: richer in harmony, more sumptuous in sonority, more laden in texture, more heroic in rhythm and rhetoric, more impressively masterminded than ever.

FIG. 3-6 Costume designs for Rameau’s Castor et Pollux (1737).

When André Campra said of the fifty-year-old Rameau’s first opera that it contained enough music for ten operas, he did not mean it as a compliment. That same opera, Hyppolite et Aricie (1733), was the very first musical work to which the adjective “baroque” was attached, and as we know, that was no compliment either. Rameau’s prodigality of invention and complexity of style were taken by some as a hubris, a representation of personal power and therefore a lèse-majesté (an affront to the sovereign), offensive not only to the memory of the great founder, whose works were in effect the first true “classics” in the history of music, sacramentally perpetuated in repertory, but also to what the founder’s style had memorialized.

Indeed, if (as we have done) one compares Lully’s dulcet Atys of 1676 with Rameau’s pungent, even violent Castor et Pollux of 1737, one can experience a bit of a shock—until one reckons that the span of time separating these two works is greater than the span that separates Palestrina’s Missa Papae Marcelli from Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda (or, more recently, Bach’s Mass in B Minor from Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony, or Verdi’s Il Trovatore from Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring). Then the shock of the new gives way to amazement at the hold of tradition, a hold that testifies first of all to the potency of administrative centralism and absolute political authority.

The real challenge, to look ahead briefly, came about fifteen years later, with the so-called Guerre des Bouffons, the “War of the Buffoons,” an endless press debate that followed the first performances of Italian commercial opera in Paris, when the French court opera received, according to the great philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “a blow from which it never recovered.”13 Rousseau was a dilettante composer in addition to being a philosopher, and he had an interest in seeing the grand machinery of the official French style, with which he could never hope to cope, replaced with the sketchy “natural” spontaneity of the Italians. He even rode the coattails of the Italians in Paris to some popular success with his own little rustic one-acter called Le Devin du village (“The village soothsayer”).

But of course Rousseau was much more than a musician, and his intense interest in the War of the Buffoons suggests that much more than music was at stake. Historians now agree that what seems a ludicrously inflated press scuffle about opera was in fact a coded episode, and an important one, in the ongoing battle between political absolutism and Enlightenment that raged throughout the eighteenth century. As always, the Italian commercial opera—epitomized this time by a farce (we’ll take a close look at it later) in which a plucky maidservant cows and dominates her master, subverting the social hierarchy it was the business of the French opera to affirm—exemplified and stimulated the politics of opposition.

The political conflict embodied or symbolized in the War of the Buffoons has a great deal of resonance for contemporary politics, or so one might be inclined to think, and for American politics in particular. The basic philosophical contradiction eventually transcended philosophy and passed into political action, culminating in revolutions not only in France, the original site of operatic contention, but in the American colonies as well. The anti-aristocratic, egalitarian ideals expressed in America’s foundational documents, the Constitution and (especially) the Declaration of Independence, arose precisely out of the political ferment adumbrated by the War of the Buffoons. The tragédies en musique of the grand siècle speak eloquently for a social order unalterably opposed to every principle Americans are supposed to hold dear.

And yet we are not likely to be any more troubled by the political content or implication of these works—at least while listening to them—than we are likely to be troubled on hearing “popish ditties” like the Missa Papae Marcelli if we are Protestants (as long as we do not hear them in church). Nor are we apt to be troubled by our equanimity when (as now) it is pointed out. But why should that be so? Why does our appreciation of such works now tend to be almost completely nonpolitical, when their political content was so much a part of their original meaning and value?

Answers to these questions are not simple; indeed, they are questions with which we will have to struggle repeatedly from this point on, just as composers and listeners have struggled with them ever since the notion—the ever-expanding notion—of modern participatory politics (or democracy, as we call it now) was born. Suffice it to say at this point that the answers will have to do both with the artworks with which we engage and with ourselves. Since the nineteenth century the concept both of “the work of art” and of its social import have changed radically.

Once the idea of autonomous art, existing in some sense for its own sake, was born, the tendency has been to apply it to all art that we value. We tend therefore not to expect works of “classical music” to engage with political or social issues, even if they did so at an earlier phase of their history. We are often content to enjoy it and not ask questions. And yet opera—a genre that contains much more than music, and that so often engages explicitly with political and social issues to this day—remains a somewhat ambiguous category. It is hard to regard it wholly as art for art’s sake.

So if we are not troubled by the art of the ancien régime and its absolutist politics—politics that would have consigned the vast majority of those who now enjoy that art to what we would certainly now regard as a miserable existence—it must also be because we no longer regard the figure of Louis XIV or his policies as politically active agents. The War of the Buffoons is over, we are apt to think, and Louis lost. He and his despotic policies are “history”; they do not threaten us. His victims (as we would now define them) are all dead, along with those who mourn them, and we take no umbrage at an art that glorifies his power.

When dealing with more recent despotisms—Nazi Germany, for example, or Soviet Russia, whose victims are still remembered keenly and with anguish—some remain disinclined to regard the art that glorified them as entirely innocent or politically denatured. Studying history, moreover, makes it harder to ignore the fact that it was the political absolutism they celebrated that gave the practitioners of French court music (and Lully above all) the right to institute in their own artistic sphere their own tyrannical exercise of power. Absolute authority—especially as vested in choral and, later, orchestral conductors—has remained part of the ethos of musical performance in the West long after it disappeared from the political scene. Only recently, in fact, has it been moderated by the advent of labor unions representing musicians.

Moreover, whereas modern Protestants, living in societies that have long protected their rights, or where they make up the majority population, may not regard the messages of Counter Reformation art as threatening, it may be a different matter with today’s minority populations. There is a great deal of Christian art, even very old Christian art, that makes modern Jews uncomfortable; there is a great deal of Western art that deals troublingly with “oriental” peoples; and there is much music, now regarded as “classical,” set to texts deriding the rights of women, the elderly, the handicapped, and so on.

We will encounter many examples as we continue our story into the modern age. It is important, at least in a book like this, to take the opportunity historical discussion grants us to air these matters dispassionately. As we are nearing the beginning of the age of modern politics, it seems the right time to raise the issue and make a couple of cautionary observations. One is that it may not be wise simply to assume that an artwork’s status as “classical” is enough to render it politically and socially innocuous. Another is that the impulse to dismiss such considerations as mere sanctimony or “political correctness” may be similarly imprudent.

In today’s society, it may not be superfluous to observe, the charge of “political correctness” is almost invariably made by members of privileged groups against the claims and concerns of the less privileged. It is a way of warding off threats to privilege. “Classical music,” like all “high art,” has always been, and remains, primarily a possession of social and cultural elites. (That, after all, is what makes it “high.”) This is so even in a society like ours, where social mobility is greater than in most societies, and where entry into elites can come about for reasons (like education, for example) that may be unrelated to birth or wealth. To maintain that “classical music” is by nature (or by definition) apolitical is therefore a complacent position to assume, and a rather parlous one. Complacency in support of a not universally supported status quo can serve, in today’s world, to marginalize and even discredit both the practice and the appreciation of art. With these matters explicitly raised and fresh in mind, we may return to our historical narrative with heightened awareness, perhaps, of their ubiquitous implicit presence.

Our next topic, the fate of music (and particularly of opera) in England during the seventeenth century, will underscore with special intensity the relationship between high art and the fortunes of social and political elites. It will also help delineate the difference between the elite attitudes of yesterday and those of today. The hereditary elites of old regarded art as something “there for them”—something that was at their disposal, that awaited their pleasure. The cultural and intellectual elites of today often seem to regard art with a respect formerly reserved for the holy and the mighty. High art has been placed on a pedestal, and we, so to speak, are there for it. And in this attitude of submission to art we have perhaps identified another rationale for our curious habit of purging the notion of art of its social and political component: we now think of art as bigger than its patrons.

These notions are recent, they are virtually restricted to “the West,” and they are decidedly odd when placed in a historical or a global context. But they are the ones most of us have grown up with, and so they can seem “natural” to us. To see them historically means seeing them as strange. Observing a radically different scale of values at work can help us achieve detachment from the familiar and better evaluate our acceptance of it.

Whether courtly or commercial, opera (or, for that matter, any full-blown music in the theater) simply did not take hold in England for most of the seventeenth century. “Spoken drama with musical decorations” was about as far as the English were prepared to go. Shakespeare’s plays made provision for a bit of incidental music, not only in occasional popular-song texts—for instance “It was a lover and his lass, with a hey and a ho and a hey nonny no” from Twelfth Night, of which Thomas Morley made a still-famous setting—but also in the stage directions, which call for trumpets, “hautboys” (high woodwinds, or what would later become oboes), and so on, playing “alarums” (signals for attention), or “sennets and tuckets” (flourishes and “toccatas,” as Monteverdi called them). And a stronger case of the same prejudice that prevented the French from tolerating a virtuoso aria from the mouth of a major character prevented the English from tolerating any music at all from such a mouth. Dramatic “verisimilitude”—sheer believability—would not stretch that far in England. Music, when used at all in the theater, was consigned to the gaudy periphery.

During the early Stuart reigns—called the “Jacobean” period after James I (reigned 1603–25), the Scottish king whose ascent to the throne of England created what is now officially known as the “United Kingdom”—music found its chief theatrical outlet in dance entertainments called masques, which lay somewhere between a costume ball and the prologue to an early Italian or (especially) French court opera. The name of the genre recalls its early link with mummery—masked ceremonial and carnival dancing. By the time of James I such entertainments were organized around mythological or allegorical plots in praise of the ruler or some aristocratic patron. (One early Jacobean masque took as its theme “The Virtues of Tobacco,” recently imported to England from the New World colonies and thought to have medicinal properties.) The participants were noble amateurs, who often selected dance partners from the audience for a central episode (or “entry,” from the French entrée) called “revels,” that amounted to a suite of plotless social dances.

The chief Jacobean masque-maker was the playwright Ben Jonson (1572–1637), whom James I chose as “Master of the Revels” before elevating him in 1617 to become the first British poet laureate. The few individual songs and dances that survive from Jonson’s masques were mainly the work of James’s stable of court composers, including Robert Johnson (ca. 1583–1633), Thomas Campion (1567–1620), Alfonso Ferrabosco II (ca. 1575–1628), and John Cooper (alias Coprario, d. 1626). The closest the Jacobean masque ever came to opera was Jonson’s Lovers made Men of 1617, in which the music, by Nicholas Lanier (1588–1666), was “sung after the Italian manner, stilo recitativo,” according to the published libretto. The music does not survive, however, and so it is impossible to say how continuous it really was.

It is also difficult to say how much masque music survives in the many Jacobean manuscripts that contain dances for lute or for “consorts” (or as we would say, ensembles) of viols. The great profusion of Jacobean instrumental music, especially consort music, compared with the relative paucity of vocal or theatrical music, seems a reliable guide to the musical tastes of the period no matter how low a survival rate we assume. Jacobean England may well have been the earliest European society to value instrumental music more highly than vocal. The preference was as much a social as an esthetic indicator.

Jacobean consort music was, in effect, the earliest instrumental chamber music. It had its forerunners, chiefly in northern Italy—the instrumental chanson reworkings published by the Venetian printer Ottaviano Petrucci beginning in 1501, the ensemble ricercars and canzonas of sixteenth-century Venice, and so on. But the English repertory was not only larger and more varied than these; it also came much closer to our modern idea of what chamber music is. Although “chamber music” performance in our own time has by now been thoroughly professionalized and takes place as much or more on the concert stage than it does in homes, the idea of chamber music originally implied private conviviality. In chamber music, audience and performers are ideally one.

Thus it was in its origins a wholly secular art and largely a domestic one, without significant or necessary social ties to the contemporary court or church (although, as we shall see, there were some residual musical ties to the latter). It was an art addressed to amateurs and connoisseurs, implying privacy and leisure, and ultimately affluence. But its uniqueness lay in the fact that it was an art not primarily of noblemen or courtiers but one of “gentlemen”—aristocrats of commerce and education rather than by way of birthright. Only England had a class of this kind—“self-made men” (though not yet a “bourgeoisie” since they resided for the most part on country estates)—sufficiently numerous and developed to support a distinct musical subculture.

One of the best descriptions of this musical subculture was written by Roger North (1651–1734), a latter-day member or descendent of the class that nurtured it. He belonged to a very distinguished family, a few of whose members held baronies, estates that carried with them minor titles of nobility. The untitled members of the clan distinguished themselves in learning, in trade, and in civil service. Roger North spent his early years in law and politics, holding the offices of solicitor general to the Duke of York and attorney general to the queen consort of King James II. His elder brothers had even more distinguished careers. One, Sir Dudley North (1641–91), amassed a huge personal fortune in trade with the Ottoman Empire and, not altogether surprisingly, became an important early advocate of laissez-faire economics (“free trade”).

Roger North was rather early excluded from politics as a result of the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 that dislodged the Stuart dynasty from the throne, and he spent the rest of his life as a country squire and scholar with a special interest in music. In this he followed in the footsteps of his grandfather, Dudley, the third Lord North, an exemplary Jacobean gentleman who

took a fancy to a wood he had about a mile from his house, called Bansteads, situated in a dirty soil, and of ill access. But he cut glades, and made arbors in it. Here he would convoke his musical family, and songs were made and set for celebrating the joys there, which were performed, and provisions carried up for more important regale of the company. The consorts were usually all viols to the organ or harpsichord …. When the hands were well supplied, then a whole chest went to work, that is six viols, music being formed for it; which would seem a strange sort of music now … 14

Indeed, it was even by the time Sir Roger wrote a somewhat strange sort of music, and one that has long attracted the special interest of musical sociologists.15 It was a socially and politically “progressive” repertory in that it was cultivated by very early members of an entrepreneurial class that, over the next couple of centuries, would challenge the power of the aristocracy all over Europe and that appears to us now as the truest harbinger of the capitalist or “free market” societies of the modern world. At the same time, it was stylistically about the most conservative repertory to be found anywhere in the world. That very combination—economic libertarianism and cultural conservatism—characterizes “business” attitudes to this day.

The two main genres of Jacobean consort music were both inherited directly from the Elizabethan, and even pre-Elizabethan, past. The fantasy or fancy as it was colloquially known (or “fantazia,” to give the more formal designation found in the musical sources) was, in North’s unimprovable phrase, an “interwoven hum-drum” made up of successive points of imitation—known as fantazies since the fifteenth century—occasionally relieved by chordal writing. In other words, it was a textless imitation of the sacred genre known since the fifteenth century as the motet (although the term goes back to the thirteenth).

Thomas Morley, writing at the end of the sixteenth century, called it “the chiefest kind of music which is made without a ditty,” that is, without words, and emphasized the freedom that this gave the composer, who “taketh a point at his pleasure and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little of it according as shall seem best in his own conceit,” so that “in this may more art be shown than in any other music because the composer is tied to nothing, but that he may add, diminish, and alter at his pleasure.”16 Morley’s description, with its enthusiastic emphasis on freedom of enterprise, is consistent with the social status of the genre, even in Morley’s day a gentleman’s occupation par excellence, and also consistent with Morley’s own status as England’s foremost musical entrepreneur.

The genre’s extreme stylistic conservatism—conservatism in the most literal, etymological sense of “keeping old things”—can be dramatically illustrated by focusing on one of its most popular subgenres, a special type of fancy called the “In Nomine.” The odd name, which means “in the name of,” is derived from the text of the Mass Sanctus (“Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini” or “Blessed is he who cometh in the name of the Lord”). Indeed, the instrumental genre goes back to a particularly grand and venerable English cantus-firmus Mass, John Taverner’s six-voice Missa Gloria tibi Trinitas, based on a pre-Reformation (Sarum) Vespers antiphon for Trinity Sunday, “Glory to thee, O Trinity.” Taverner probably composed the Mass around 1528. The chant-derived cantus firmus from the In nomine section of Taverner’s Sanctus, scored for a reduced complement of four solo voices, became the ever-present cantus firmus for the whole repertory of instrumental In Nomines, a repertory numbering in the hundreds and practiced for almost a century and a half after Taverner’s death in 1545.

How did such an improbable tradition get started? Although Taverner’s original In nomine was copied out for instruments and is found in many manuscripts containing fancies, the instrumental In Nomine repertory as such evidently goes back to Christopher Tye (ca. 1505–73), an Elizabethan composer best known for his Anglican hymns and anthems, who wrote no fewer than twenty-one In Nomine fancies (mostly in five parts) over (or, more frequently, under) Taverner’s cantus firmus as a sort of sideline or hobby. As usual with a big series of similar pieces, the composer eventually began to show off his craft by indulging in various sorts of gimmicks.

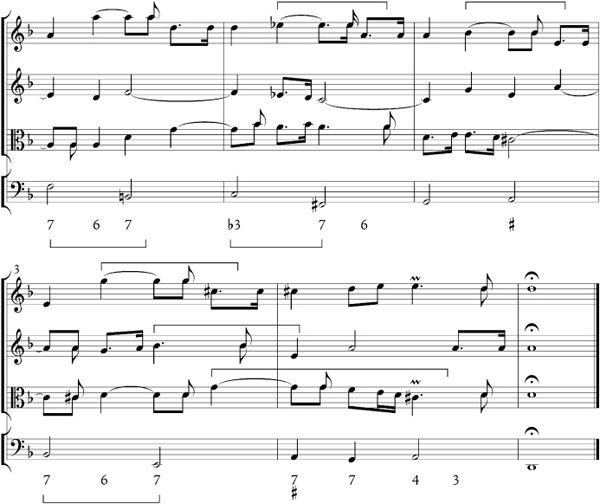

One of his In Nomines, for example, called “Crye,” has a subject consisting of a series of rapid repeated notes that mimic a street vendor’s cry. (Weaving plebeian “Cries of London” or “Country Cries” into the otherwise abstract texture of viol fancies was another standard subgenre that amused the gentlemen patrons of the medium.) Another, called “Howld Fast” (i.e., “hang on”) casts the Taverner cantus firmus in dotted semibreves that crosscut the implied meter of the other parts. Yet another, called “Trust,”is cast in what we would now call a  meter (Ex. 3-7).

meter (Ex. 3-7).

EX. 3-7A Christopher Tye, In Nomines, “Crye” (opening)

EX. 3-7B Christopher Tye, In Nomines, “Howld Fast” (opening)

EX. 3-7C Christopher Tye, In Nomines, “Trust” (opening)

As in the case of the “L’Homme Armé” Masses of the fifteenth century, Tye’s prolific output of In Nomines, both technically impressive and whimsical, seems to have stimulated the emulatory impulse that led to the creation of the genre. The great upsurge of interest in consort music during the Jacobean years led to a flood tide in which every composer of fancies participated. The aged William Byrd composed seven In Nomines, a total exceeded only by Tye himself. After Byrd, the next most prolific In Nomine composer was Alfonso Ferrabosco II, the English-born son of Byrd’s early Italian motet mentor, who composed six, of which three were scored for the full “chest” of six viols, thought not only by North but by all contemporary writers to be the ideal consort medium: “your best provision (and most complete),” in the words of Thomas Mace, seventeenth-century England’s most encyclopedic theorist, who specified that a “good chest of viols” were “six in number, 2 Basses, 2 Tenors, 2 Trebbles, all truly proportionably suited.”17 As time went on and the tradition developed, the style of writing became increasingly idiomatic and “instrumental,” further belying the genre’s vocal, ecclesiastical origins.

The In Nomine by Ferrabosco excerpted in Ex. 3-8, which dates from around 1625, is scored for just such a full complement of viols (Fig. 3-7). The old cantus firmus is given, rather unusually, to one of the treble viols, and was probably played by a novice on the instrument. (The inevitable presence of a part playable by a child has been counted one of the reasons for the In Nomine’s popularity, given the family surroundings in which English consorts were apt to be played.) Meanwhile, the other parts converse motet-fashion, approaching, toward the end, the kind of “perpetuall intermiscuous syncopations and halvings of notes” that North cited as one of the chief pleasures of the genre.

The bass viols, in particular, are given some elaborate “divisions” to play during the last point of imitation; these reflect the solo repertoire that was also growing up at the time, which mainly consisted of bass viols doing what contemporary musicians called “breaking a base”: performing ever more elaborate variations over a ground. Like most virtuoso repertories, that of the “division viol” was as much an improvisatory practice as a literate one. (Its greatest exponent was a gentleman virtuoso named Christopher Simpson, who published a treatise on the subject, called The Division-violist, or the Art of Playing Extempore upon a Ground, in 1659.) The consort fancy, however, depended entirely on writing for its dissemination and performance. It represents positively the last outpost of what on the continent had already been consigned once and for all to the “first practice” or stile antico: a final wordless flowering of the motet, and even, in the case of the In Nomine, of traditional cantus-firmus composition.

EX. 3-8 Alfonso Ferrabosco II, In Nomine a 6

FIG. 3-7 A chest of viols (the ensemble near the right), shown in an anonymous painting (ca. 1596) of the wedding masque for Sir Henry Unton, Queen Elizabeth’s special envoy to the French court.

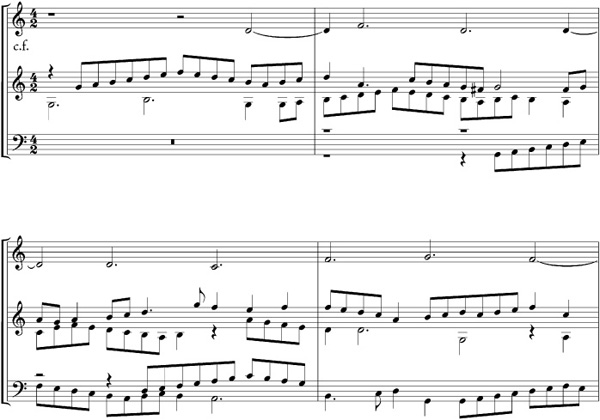

The other main genre of consort music was the “ayre,” a general term no longer meaning a song, but rather any sort of dance-style composition. (Its etymology was chiefly by way of the solo accompanied song or “lute ayre,” which in the hands of great virtuoso John Dowland usually took the form of a pavane or galliard with two or three repeated strains.) The later composers of consort music tended to write their pieces in “setts” that began with one or two numbers in the more elaborate fancy form and concluded more lightly with an ayre or two. The ayre by William Lawes, whose ending is shown in Ex. 3-9, is the final item in what the key signature of two flats already identifies as an unusually serious set: on the way to it there are two lengthy fantasies and an “Inominy,” all in what we would call the key of C minor. (In the seventeenth century minor keys with flats generally carried “Dorian” signatures, that is, with one less flat than their modern counterparts; flatting of the sixth degree was usually done at sight, by applying already ancient rules of chromatic adjustment.)

This ayre, which is really an alman or allemande (“German dance”; cf. Frescobaldi’s balletto) in a dignified duple meter, is cast in a form that will remain with us for centuries to come. Its two dance strains make cadences respectively on the dominant (replete with borrowed leading tone) and tonic, producing an effect of harmonic (or “tonal”) complementation. This “there and back” or “to and fro” effect was immediately found to be an exceedingly stable and satisfying plan for structuring a composition. Indeed, the very concept of autonomous musical “structure” was in large part enabled by the seemingly inherent coherence of this complementary (or “binary”) harmonic relationship. The binary form, originally associated, as here, with dance-derived compositions, would undergo a glorious evolution that quickly transcended the utilitarian genre in which it originated and provided the basis for what has long been known as “absolute music.”

That evolution, of course, lay largely in the future when Lawes composed his “setts,” but his use of the binary form already entailed a good deal of “transcendence of the utilitarian.” The genre of chamber music is itself an embodiment of transcendence, since its constituent genres—the motet-derived fantasy, the Mass-derived In Nomine, the dance-derived ayre—have all been thoroughly divested of their original functions and have become the bearers of abstract or “absolute” tonal patterns for performing or for listening (or, ideally, for both at once) as a form of social recreation.

Yet “abstract” or “absolute” by no means precluded a high level of purposeful expressivity. Flat keys, as we have observed, already connoted pathos, and Lawes followed through with pungent suspension dissonances in the first strain and chromatic inflections in the second (including a really acrid augmented triad in the third measure of Ex. 3-9). These “madrigalisms” without a motivating text show the tardy but inexorable infiltration of what the Italians called seconda prattica effects into the consort repertory.

EX. 3-9 William Lawes, Ayre in six parts

Lawes (1602–45), whose career reached its peak under Charles I, King James’s son and successor, cultivated a highly pathetic style in all his works, as a few of his expressively contorted fantazia themes will vividly attest, their wide leaps and striking arpeggiations seeming to parallel the “mannerist” elongations and foreshortenings of an El Greco torso (Ex. 3-10). Lawes’s remarkably “purple” manner made the already idiosyncratic mixture of old and new in the English consort idiom seem all the more noteworthy and bizarre. Some accounts of Lawes’ spectacular “manneristic” tendencies attribute them to sheer composerly appetites and creative genius; others have sought the origins of the style in broader historical and political conditions. But there is no reason to regard these alternatives as incompatible. Like everyone else, musicians respond to varying degrees, and with varying degrees of consciousness, to historical and political conditions; but—perhaps needless to say—musicians also respond, and respond with the keenest consciousness, to music.

EX. 3-10A William Lawes, fantazia themes, Suite in G Minor

EX. 3-10B William Lawes, Suite in C Minor in five parts

EX. 3-10C William Lawes, Suite in C Major (two variants)

EX. 3-10D William Lawes, Suite in C Minor in six parts

The broader historical and political conditions to which musicians of the mid-seventeenth century perforce responded are reflected deliberately and directly in “A Sad Pavan for These Distracted Times” by Thomas Tomkins, originally for keyboard but transcribed for strings as well (Ex. 3-11). Tomkins (1572–1656), formerly organist of the Chapel Royal, was one of the oldest English musicians still alive and semi-active during the times in question.

EX. 3-11 Thomas Tomkins, “A Sad Pavan for These Distracted Times”

The phrase “these distracted times” was a standard contemporary euphemism for the greatest political upheaval in British history: the Civil War of 1642–48 that culminated in the trial of King Charles I for treason and his beheading on 30 January 1649, after which a republican form of government, called the Commonwealth, was instituted under the nominal rule of Parliament, but in actuality under the personal dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell, the leader of the Puritan party, who in 1653 took the title of Lord Protector. Tomkin’s Sad Pavan bears the date 16 February 1649, roughly a fortnight after the regicide, and its tone bears witness to his loyalty and his sorrow at his former patron’s fate.

Although it is often called the Puritan Revolt, the English Civil War is no longer thought of as a primarily religious conflict. Historians now view it as a collision between the country gentry and urban merchants (the very classes whose support had made possible the growth of English chamber music) on the one hand, and the crown and nobility on the other, whose restrictive trade policies were inhibiting the economic growth of the self-made classes. The most lasting result of the Civil War was the victory of the “common law” over the so-called divine right of the king and the eventual establishment (after the Glorious Revolution of 1688) of the world’s first constitutional monarchy.

Despite the popularity of their chamber music among the classes who broke with the crown, the loyalties of composers, as of all artists and entertainers, were overwhelmingly on the royalist side, for that is where artists and entertainers dependent on patronage had always perceived their self-interest to lie, and that must account in part for the elegiac tone that is so conspicuous in the instrumental music of the Caroline years, the years of King Charles’s ill-fated reign. In the exaggerated but colorful words of the mid-nineteenth-century historian Thomas Macaulay, “the Puritan austerity drove to the King’s faction all who made pleasure their business, who affected gallantry, splendour of dress or taste in the lighter arts, and all who live by amusing the leisure of others, … for these artists well knew that they might thrive under a superb and luxurious despotism, but must starve under the rigid rule of the precisians [religious ascetics].”18

Indeed, one of the casualties of these tumultuous events was William Lawes himself, who fought and died in the 1645 Siege of Chester, one of the King’s signal defeats. As the very partisan poet Thomas Jordan put it in a eulogy for the fallen musician,

When pestilential Purity did raise

Rebellion ’gainst the best of Princes, And

Pious Confusion had untun’d the Land

When by the Fury of the Good old cause

Will Lawes was slain by such whose Wills were

Laws.19

Puritan hostility to the arts, and to music in particular, is often exaggerated. Unlike the early Anglicans they did not instigate search-and-destroy missions against musical artifacts. But of course the absence of a royal court, both under the republican Commonwealth and under the military dictatorship (Cromwell’s Protectorate) that succeeded it in the 1650s, meant that patronage for musicians reached an all-time low. As Calvinists, the Puritans did not tolerate an elaborate professional church music, and so the musical establishments of the Church of England reached a low musical point as well, and the most exalted of British musical traditions suffered disruption and virtual extinction. The Puritans were indeed hostile to the theater, and from 1649 to 1660 closed it down in England; but as we have seen, musical theater had failed to establish itself in England for reasons unrelated to the fall of the royal court or the rise of the Puritan party to power.

The fortunes of music in England, and of theatrical music in particular, took a decisive turn with the Stuart Restoration, the reestablishment of the British monarchy less than a dozen years after its abolition. Charles II, the 30-year-old son of the deposed king, was summoned back from France, where he had been exiled (with interludes in Germany and the Netherlands) since 1646, and crowned in 1660. A shrewd diplomat and skillful politician, Charles II reigned relatively peacefully until 1685, the last three years actually as an absolute monarch without a parliament, but—in marked contrast with this father—a very popular despot. One of the sources of his popularity was the cosmopolitan, libertine character of his court, a most welcome contrast with the times that had gone before. It was a court where (in the waggish words of Keith Walker, a literary historian), “anything went, where actresses were regularly rogered, where whores were ennobled to duchesses, where the arts flourished, where if greed wasn’t yet good, hypocrisy certainly was.”20

In its very cynicism, this sentence neatly encapsulates the contemporary attitude toward the arts and their place in the Restoration scheme of things. No matter how heroic or serious their content, they were viewed and cultivated as an aspect of luxurious living on a par with other sensual and gustatory delights. That hedonism, tinged as it was with licentiousness, may seem to us attractive enough; but in the context of seventeenth-century England it meant a resurgence of aristocratic tastes, values, mores, and privileges. We have another choice example of the beneficial effect of absolutist politics—an ugly politics, most would agree today—on the growth of the fine arts; and again the question starts nagging, whether the élite arts that we treasure can truly flourish in a political climate that we would approve.