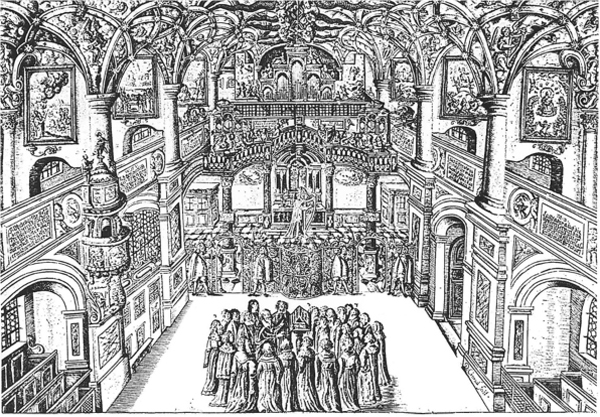

Whoever wrote it, and however it may have related to Monteverdi’s original design, the ending of L’incoronazione di Poppea was a harbinger. The seventeenth century was the great age of the ground bass. Infinitely extensible formal plans (if “plan” is indeed the word for something that is infinitely extensible) enabled musical compositions to achieve an amplitude comparable to the extravagantly majestic Counter Reformation church architecture that provided the spaces in which they were heard (and to which the word “baroque” was first applied).

These forms grew directly out of an oral or “improvisatory” practice that continued to flourish alongside its written specimens. The written examples, especially those meant for solo virtuosos to perform, represented the cream of the oral practice—particularly effective improvisations retained (as “keepers”) in memory for repeated performance and refinement and eventual commitment to paper, print, and posterity.

That certainly seems to be the case with Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583–1643), the organist at St. Peter’s basilica in Rome from 1608 to his death, whose mature works were among the most distinctive embodiments of practices arising in the wake of the Counter Reformation. He was at once the most flamboyantly impressive keyboard composer of his time and the most characteristic, because it was characteristic of early seventeenth-century music to be flamboyantly impressive. The theatricalized quality that virtually all professional music making strove to project was as avidly cultivated by instrumentalists as by vocalists and those who wrote their material. The stock of the instrumental medium rose in consequence to the point where a major composer could be concerned primarily with music for instruments. Before the seventeenth century that had never happened.

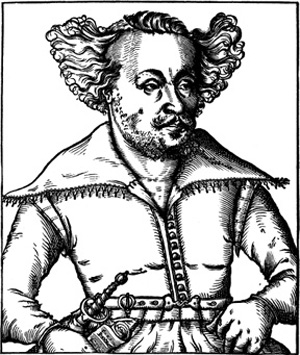

FIG. 2-1 Girolamo Frescobaldi, by Claude Mellan (1598–1688).

FIG. 2-2 Interior of St. Peter’s basilica, Rome, painted in 1730 by Giovanni Paolo Pannini (1692–1765).

Many of Frescobaldi’s compositions circulated during his lifetime only in manuscript, but the composer did personally oversee the publication of sixteen volumes between 1608 and 1637. Of the sixteen, only four volumes contained vocal compositions: one of motets, one of madrigals, and two of continuo arias written during a brief sojourn in Florence. The remaining twelve were devoted to instrumental works. Eight of them were issued in partitura, that is, laid out in score with strict voice leading, in most cases with parts provided so that they could be performed by ensembles as well as at the keyboard. The remaining four were libri d’intavolatura, idiomatic keyboard compositions laid out like modern keyboard music on a pair of staves corresponding to the player’s two hands, with free voice leading and other effects that precluded ensemble performance.

When he played them himself, the composer certainly adapted his ricercari, fantasias, and canzonas to the idiomatic style of his “intabulations.” Nevertheless, the libri d’intavolatura contained Frescobaldi’s most novel, most theatrical, and most elaborately “open-ended” compositions, and in that sense they reflected his most vividly over-the-top (i.e., “baroque”) side. Such compositions came in two main types—partite (that is, variations) over a ground bass, and formally capricious, unpredictable toccate. We will sample both at their most flamboyant.

A visiting French viol player named André Maugars left a revealing description of the mature Frescobaldi at work (or at play) in 1639, “displaying a thousand kinds of inventions on his harpsichord [spinettina] while the organ stuck to the main tune,” adding that “although his printed works give sufficient evidence of his skill, still, to get a true idea of his deep knowledge, one must hear him improvise toccatas full of admirable refinements and inventions.”1 Maugars well knew whereof he spoke. As an internationally famous musician from whom no written music survives, he if anyone knew that the musical daily business of seventeenth-century instrumentalists continued to be transacted ex tempore. On the same trip to Rome, Maugars enjoyed his own success before Pope Urban VIII, Frescobaldi’s patron, improvising in the organ loft during Mass on a theme presented as a challenge by the organist, who then repeated it as an accompaniment “while I varied it with so much imagination and with so many different rhythms and tempi that they were quite astonished.” Frescobaldi’s famous Cento partite sopra passacagli (“A Hundred Variations on Passacalles”), the concentrated residue of years of similar improvising, is nothing if not astonishing, with its frequent surprising forays into contrasting rhythms and tempi and its startling harmonic effects. It comes from the last of his keyboard publications, called Toccate d’intavolatura di cembalo et organo, partite di diverse arie, e correnti, balletti, ciaccone, passacagli, published in Rome in 1637. The title lists four other keyboard genres besides toccatas and partitas:

—The corrente was a dance in triple meter (courante in French) that could occur either with a quick step notated in  or

or  or in a more stately variant notated in

or in a more stately variant notated in  with many hemiolas.

with many hemiolas.

—The balletto, as Frescobaldi used the term, was a dignified dance of German origin (hence allemande in French), usually in a broad duple meter. Balletti and correnti were often cast in melodically related pairs, like the pavanes and galliards of the previous century.

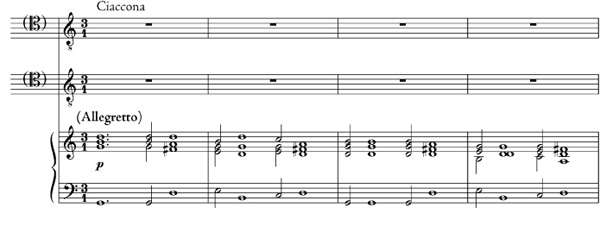

—The ciaccona was a fast and furious dance in syncopated triple meter, which in the sixteenth century had been imported into Spanish and Italian courtly circles from the New World. (The first literary use of the word chacona, the Swiss music historian Lorenzo Bianconi has disclosed, came from a Spanish satire on Peruvian customs published in 1598.2) Its first appearance in a musical print was in an Italian guitar book of 1606, where it was given as a formula for singing poetry in the manner of an old-fashioned “aria.”3 As a dance, the ciaccona was built over repetitive chord progressions similar in practice to the traditional Italian dance tenors, and was considered so inveterately lascivious that it was banished—as an actual dance—from the Spanish stage. An air of forbidden fruit surrounded it thereafter, which is why it was the inevitable choice of Sacrati (or whoever it was who renovated L’incoronazione di Poppea) for the lubricious final duet. The Italian poet Giambattista Marino (1569–1625), whose highly mannered, flamboyant verses Monteverdi often set, aimed some mock curses at this “immodest, obscene dance, with its thousand twisted movements” in his epic Adonis: “Perish the foul inventor who first amongst us introduced this barbaric custom,…this impious profane game, which the novo ispano [i.e., the denizen of “New Spain,” meaning the Americas] calls ciaccona!”4 These lines were written in 1623. Nine years later, Monteverdi published his setting of Ottavio Rinuccini’s imitation of Petrarch’s famous sonnet Zefiro torna (“The breeze returns”) in the form of a “ciacona” (Ex. 2-1), and from then on it was a major Italian medium for love poetry, for stage music, and for instrumental virtuosity.

—Passacagli is Italian for passacalles, a related Spanish genre consisting of variations on cadential patterns that apparently grew out of the habits of guitarists who accompanied courtly singers, and who introduced and bestrewed the songs with casual ritornellos—the kind of thing accompanists in today’s nonliterate (“pop”) genres call “vamping.” Like today’s popular guitarists and keyboardists, who often take off on their vamping figures for impressive flights of fancy, so the players of passacagli often elaborated them into long instrumental interludes, eventually into independent instrumental showpieces.

The repetitive cadential phrases of the ciaccona and the passacagli were a natural for adaptation to traditional ground-bass techniques, and that is how they entered the domain of written music. The first literate instrumental adaptations of the two related genres were by Frescobaldi. His second libro d’intavolatura, published in 1627, contained both a set of Partite sopra ciaccona (roughly “variations on the chacona”) and one of Partite sopra passacagli (“variations on passacalles”). Eventually the name of the latter variations genre was standardized in Italian as passacaglia, and the ciaccona, owing (as we shall see) to its many adaptations on the French stage, has become falsely but firmly identified with France and is now most widely known as the chaconne.

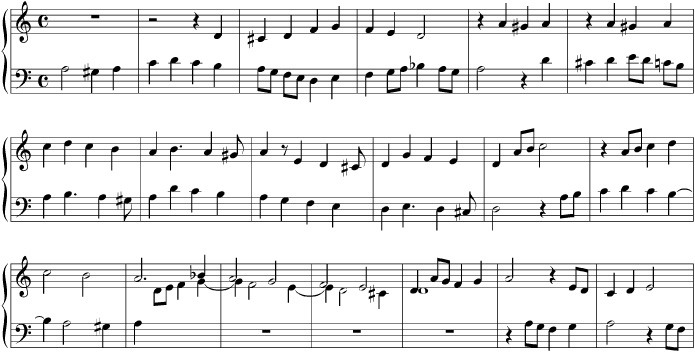

EX. 2-1 Claudio Monteverdi, Zefiro torna, beginning

Frescobaldi’s enormous Cento partite (“hundred variations”) of 1637, though nominally another passacaglia set, actually mixes several of the genres just described. A total of 78 actual passacagli or varied two- or four-bar cadence figures alternate first with a corrente and then with some forty ciaccona progressions, producing a total far in excess of one hundred, from which the player was invited to choose ad libitum. As the composer wrote in the preface, “the passacaglias can be played separately, in accordance with what is most pleasing, by adjusting the tempo of one part to that of the other, and the same goes for the ciacconas.”5

It is even possible that the word cento in the title was chosen for its resonance with the earlier Latin usage, chiefly used in connection with church chant, which denotes not literally “one hundred” but rather a patchwork or mixture of formulas. The title, then, would mean something like “A mixed bag of variations on passacaglias [and other things]” or “Passacaglias mixed with other ground-bass formulas.” In any case, Frescobaldi’s fanciful mixture of sameness and contrast gave instrumental music access to a whole new temporal plane, and a newly dramatized character. This was music with real “content,” not just an accessory to vocal performances or a liturgical time-filler.

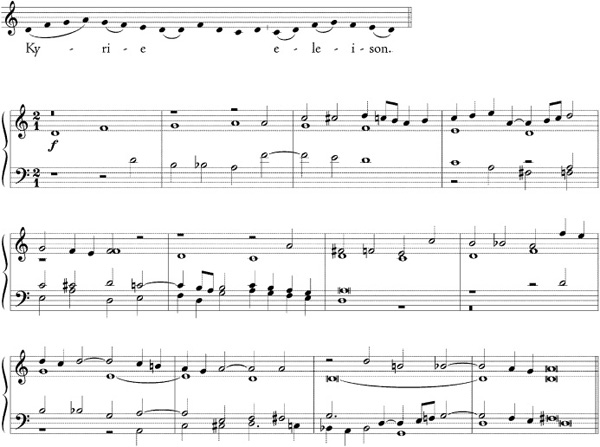

Yet tonally speaking, and in keeping with its character as compendium rather than a work of fixed content, Frescobaldi’s mixed bag is extremely, even disconcertingly, loose. The first set of passacagli, as well as the corrente that they surround, are in D minor. A sudden cadence to what we call the “relative major” on F, duly labeled “altro tono” (“the other mode”), leads to the first section labeled ciaccona, also in F. From there on the tonal behavior of the composition is altogether unpredictable, as is the final cadence on E. This lack of “tonal unity” has led some writers to suggest that the work is no “composition” at all, but just an assortment of goods. Other writers have even suggested that the components were printed in the wrong order as the result of “some sort of mishap at the printer’s office,” to cite one scholar’s particularly rash proposal.6 The composer’s presence on the scene, and his presumable role as proofreader, makes this somewhat implausible. While granting that the performer had many options besides the printed order (“in accordance with what is most pleasing,” as the composer allowed), the printed order must surely be counted as one of the available options. The only conclusion the evidence supports is that the “tonal unity” we look for now in an extended composition was not (yet) considered a necessary criterion of coherence for works of this type. Ex. 2-2 shows the final section, in E. Note the cadences in every other bar. Their regularity is in fact a guide to tempo; from their placement we can tell, for example, that the note values following the triple meter signature should be read at doppio movimiento or double speed.

The earliest recorded use of the word “toccata” in a musical source occurs in a lute collection of 1536, where it refers to the kind of brief improvisatory prelude formerly called preambulum or ricercar or even tastar de corde (“checking to see if the strings are in tune”). The new term was evidently coined to substitute for “ricercar” when the latter term had become firmly associated with “strict” imitative compositions in motet style. Over the next hundred years the term saw a variety of uses; we have already seen it applied by Monteverdi to the curtain-raising flourish before his Orfeo, a kind of theatrical preambulum. Later on, pieces called “toccata” achieved greater dimensions and independent status, but they always remained “free” and open in form, deriving their continuity from discontinuity, to put it paradoxically. That is, they relied on contrast—in texture, meter, tempo, tonality—between short striking sections, rather than the continuous development of motives, to sustain interest. “Striking” meant virtuosic as well; toccatas, like the preluding improvisations of old, were often festive display pieces that turned the very act of playing (or “touching”—toccare—the keys) into a form of theater.

EX. 2-2 Girolamo Frescobaldi, Cento partite sopra passacagli, conclusion

Frescobaldi inherited the toccata from Claudio Merulo (1533–1604), whose two books of toccatas, published in Rome shortly before Frescobaldi took up his duties at St. Peter’s, had established what would become the genre’s basic modus operandi as an alternation of “free” chordal and “strict” imitative sections. With his horror of regularity, Frescobaldi turned Merulo’s placid interchanges into another sort of “mixed bag,” in this case a dazzling bag of tricks. In the very lengthy and detailed preface to his first book of toccatas, the epochal Primo libro d’intavolatura (“First book of intabulations,” 1615), reprinted in every subsequent book, Frescobaldi explicitly gave the performer the last say as to the form his toccatas took, just as he himself must have done when performing them. “In the toccatas,” he wrote, “I have taken care not only that they be abundantly provided with different passages and affections but also that each one of the said passages can be played separately; the performer is thus under no obligation to finish them all but can end wherever he thinks best.”7

This option would seem to apply particularly to the famous Toccata nona or ninth toccata from Frescobaldi’s second book (1637), which set a new and widely emulated standard for fireworks (Ex. 2-3). It begins with a bit of cursory lip service to imitation between the hands, but motivic consistency is not maintained past the second bar; and although the piece ends where it began, in F, the tonal vagaries along the way are seemingly as wayward as possible. It is that sense of wandering through a harmonic labyrinth, as well as the mounting rhythmic figuration and the frequent superimposition of conflicting divisions of the beat (“threes against twos”), that must have prompted the curious note of mingled self-congratulation and lampoonery that Frescobaldi appends in conclusion: Non senza fatiga si giunge al fine (“You won’t make it to the end without tiring”). The many apparent changes of time signature along the way are really proportion signs:  , for example, literally means 12 sixteenth notes in the time of eight, later cancelled by its seemingly inscrutable reciprocal,

, for example, literally means 12 sixteenth notes in the time of eight, later cancelled by its seemingly inscrutable reciprocal,  . It is the sort of thing indicated in more modern notation by the use of triplet signs and the like (Ex. 2-3).

. It is the sort of thing indicated in more modern notation by the use of triplet signs and the like (Ex. 2-3).

EX. 2-3 Girolamo Frescobaldi, Toccata IX (Toccata nona), mm. 11–22

In the hands of Frescobaldi’s pupils like Michelangelo Rossi (1602–56), the toccata could become truly bizarre, seemingly in the spirit of the late polyphonic madrigal. In Rossi’s Toccata settima, the seventh toccata in his first libro d’intavolatura (published in Rome without a date, most likely around 1640) the weird harmonic successions of Carlo Gesualdo’s madrigals or the monodies of Sigismondo d’India are elevated to the level of broad sectional contrasts (Ex. 2-4). Music like this is clearly contrived to knock listeners for a loop, the way an outlandish twist of plot might do the spectators in a drama.

EX. 2-4 Michelangelo Rossi, Toccata VII (Toccata settima), mm. 9–16

In Frescobaldi, stupefying chromatic effects are most often found in a special subgenre called toccate di durezze e ligature (“toccatas with dissonances and suspensions”) that inhabits a very different expressive world from the histrionic self-assertion of the showpiece toccatas. Such pieces are found among the other toccatas in Frescobaldi’s libri d’intavolatura (and they are found in the work of some earlier organists as well), but they may be seen in their natural habitat, so to speak, in his largest collection, Fiori musicali (“Musical flowers,” 1635), which contains music designed for specific liturgical use, arranged in three “organ Masses.”

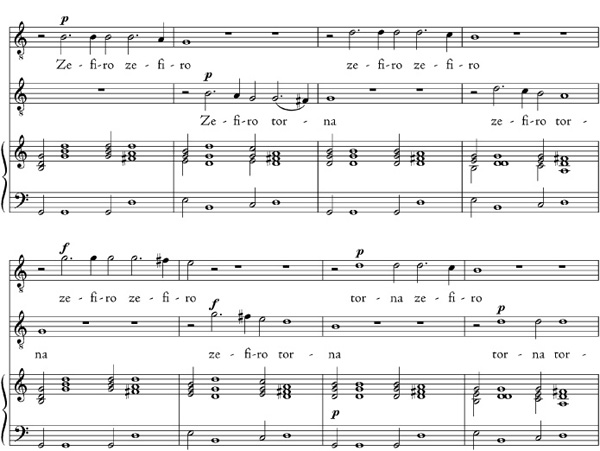

This wonderfully suggestive volume enables us to imagine the way in which organists, still for the most part working ex tempore, actually accompanied the church service in the years following the Counter Reformation. Each Frescobaldi organ Mass begins with a short flourish of a toccata (Toccata avanti la Messa) that functions as an intonazione, a fancy way to give the choir its pitch. The next (and longest) section is a complete and very old-fashioned cantus firmus setting of the Kyrie, the organist’s equivalent of the choir’s stile antico. Ex. 2-5 shows the beginning of the Kyrie setting from the second organ Mass in Fiori musicali, the Messa della Madonna (“Mass of the Virgin Mary”), based on the Gregorian Kyrie IX (“Cum jubilo”).

EX. 2-5 Girolamo Frescobaldi, Messa della Madonna (in Fiori musicali), opening section of Kyrie, mm. 13–23

Then follow a lively Canzon dopo la Pistola, a “canzona [for playing] after the Epistle [and before the Gospel],” to preface or stand in for the Gradual; a strictly imitative Recercar dopo il Credo, a “ricercar [for playing] after the Credo,” to introduce the Offertory and accompany the collection (sometimes itself preceded by a short toccata, giving the effect of what was later known as a prelude and fugue); and to conclude, a Canzone post il Comune, a “canzona [for playing] after [the singing of] the communion [chant],” also sometimes introduced by a little toccata, to accompany the distribution of the wine and wafer. The canzona, a name descending from the French chanson (song), denoted a catchy, lightweight piece in many sections.

The toccata di durezze e ligature, sometimes called the toccata chromatica, is played per le levatione, “for the Elevation,” the moment when the priest performs the transubstantiating miracle that turns the wine and wafer into the blood and body of Christ, as his ordination empowers him to do. It is the most mysterious moment of the Mass, a moment of sublime contemplation, and it is that mood of self-abasement before a truth that passes human understanding that the elevation toccata, in its unearthly harmony, is designed to capture, or induce.

The Elevation toccata from Frescobaldi’s Messa della Domenica, the Mass for Sundays throughout the year, is both his most chromatic composition and the one most poignantly riddled with suspensions. Its obsessive contemplation of an “irrational” idea, in which an apparent leading tone turns tail and descends dissonantly through semitones (an effect later classified by German theorists, among other “unnatural progressions,” as the passus duriusculus, “the hard way down”), makes the toccata an epitome of the Counter Reformation ideal, long since associated with St. Theresa, that envisaged “religious experience” as deeply felt emotion on the very threshold of pain.

Surely the most spectacular workout ever given the passus duriusculus was in a Fantasia chromatica by the Dutch organist Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621), Frescobaldi’s older contemporary, who succeeded his father as chief organist at Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk (Old Church) while still in his teens, and held it until his death. Unlike Frescobaldi, Sweelinck was not a church organist in the full sense of the word. The Dutch Reformed Church, Calvinist in outlook, forbade the use of “figural” (polyphonic or instrumental) music during services. Rather, Sweelinck was employed to perform what amounted to daily organ recitals—an hour of uninterrupted music making—to follow the morning and evening services. Like Frescobaldi, and like every other keyboard virtuoso of the day, Sweelinck was best known for his improvisations, and the works he noted down and allowed to circulate (in manuscript only) represented the skimmed cream of this daily exercise.

For publication Sweelinck composed a great deal of vocal music, most of it secular and none of it meant for actual service use. It was intended for the international music trade and was therefore composed to texts in international languages: French (chansons and metrical psalms), Latin (motets), and Italian (madrigals). Although some of his publications were equipped with organ accompaniments to make them commercially viable, none of Sweelinck’s music is actually “concerted.” His vocal music is all fully polyphonic in the sixteenth-century style; never does the instrumental bass play an independent role, nor did Sweelinck publish so much as a single solo song or monody. That makes him the youngest continental composer never to write in the concerted or monodic styles of vocal music, and he therefore looms in retrospect as the last of the legendary “Netherlanders” of the polyphonic Golden Age.

But his dual preoccupation with old-fashioned vocal music and extremely up-to-date keyboard compositions puts Sweelinck in a position comparable to no other Netherlander, but rather like that of William Byrd, his older English contemporary. The similarity was not fortuitous. While he never met Byrd, Sweelinck was well acquainted with several other English composers who had settled in the southerly (Catholic) part of the Netherlands that is now Belgium. Peter Philips (1560–1628) came to Brussels in 1589 in the entourage of a recusant nobleman, Lord Thomas Paget, who had fled England to avoid religious persecution. After Paget’s death the next year, Philips relocated in Antwerp. He was joined in 1612 by John Bull (1562–1628), who also claimed to be a religious refugee but is now thought to have been evading some sort of “morals” charge (possibly adultery or pederasty). Philips and Bull were the conduits through which the very advanced art of the Elizabethan keyboard composers established, through Sweelinck, a continental base. Sweelinck composed variations on a pavan (a slow keyboard dance) by Philips, and after his death Bull based a fantasia on a theme by Sweelinck.

Once he had absorbed the English styles and genres, moreover, Sweelinck’s work began circulating in England along with native wares. A fantasia by Sweelinck is found in the so-called Fitzwilliam Virginal Book, a mammoth collection of English keyboard music and the chief source for much of Philips and Bull. Its present name comes from its present location, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, but it may actually have been assembled at the Fleet Prison in London, where its compiler, Francis Tregian, was confined for recusancy from 1614 until his death three years later. “Virginal” was the name of the English version of the harpsichord: a small box, often in the shape of a pentagon, that contained only a single set of strings. Several virginals of various sizes were often piled atop one another to gain a fuller range of pitch and color. The origin of the name is obscure, but it was popularly associated with the girls who were most often taught to play it as a social grace, and it became the inevitable pretext for a lot of coarse punning.

The Sweelinck fantasia—one of many, especially by English composers, that used the solmization hexachord (ut–re–mi–fa–sol–la) as cantus firmus—was entered in the Fitzwilliam manuscript in 1612. Equally a tour de force of keyboard virtuosity and of counterpoint, it contains twenty officially numbered statements of the familiar scale segment, both ascending and descending, in various transpositions, diminutions, and syncopated forms, and against many countersubjects and accompaniment figures. And it harbors many hidden variations as well, including strettos. More organ-specific yet are Sweelinck’s four fantasias “op de manier van een echo” (in the manner of an echo), or echo-fantasias, in which the middle section of the piece consists of little phrases marked forte and repeated piano, calling the multiple keyboards or manuals of the organ into play. The effect is transferable to a multiple-manual harpsichord as well, and Sweelinck’s fantasias are often played on that instrument. But on the organ, with its spatially separated ranks of pipes, such passages come out as literally antiphonal, reflecting the old Venetian polychoral style.

FIG. 2-3 Pentagonal virginal (Italian, 1585) at the Russell Collection, University of Edinburgh.

The Chromatic Fantasia (Ex. 2-6), on the passus duriusculus tetrachord, pitches the titular chromatic descent on D, A, and E, so that all twelve notes of the chromatic scale are eventually employed in stages over the course of the composition. The piece is thus a magnificent reconciliation of the venerable academic counterpoint of the sixteenth century with the burgeoning affective or pathetic style of the seventeenth. It is also a summit of virtuosity, displaying the cantus firmus at four rhythmic levels (from whole notes to eighth notes in the transcription) and reaching a peak of rhythmic excitement with sextolets (sixteenth notes grouped in sixes like double-time triplets) and thirty-second notes, very much in the style of English keyboard figuration.

EX. 2-6 Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Fantasia chromatica, mm. 1–16

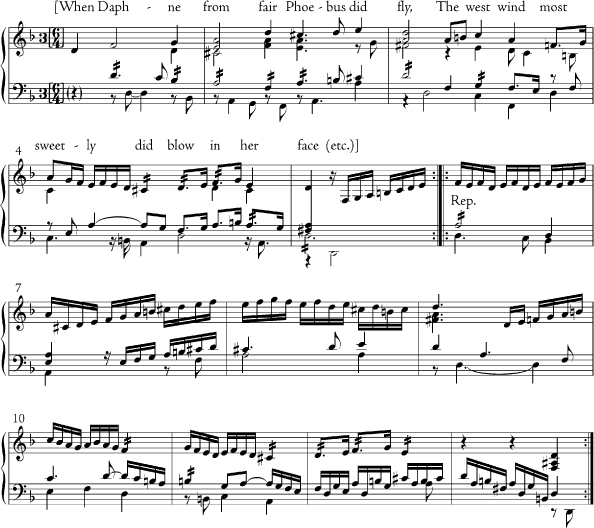

English sextolets can be seen in their natural habitat in Giles Farnaby’s Daphne, from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (Ex. 2-7). This is a set of variations (or divisions, to use the contemporary word) on a bawdy popular song that retold the myth, popularized by Ovid, of Apollo’s (or Phoebus’s) lascivious pursuit of the nymph Daphne and her rescue by the earth-goddess Gaea, who transformed her into a laurel tree. These variation sets were the virginalist composer’s most characteristic genre. Their nearest precedent were sets of diferencias—Spanish for divisions—on popular songs that were published by Iberian lutenists and organists beginning with Luis de Narváez in 1538; the most famous such set is the one by the blind organist Juan de Cabezón on the folk tune Guárdame las vacas—“Watch over my cattle”—printed in 1578, twelve years after his death. Farnaby (1563–1640), a “joiner” or carpenter by trade, was eventually a builder of virginals as well as a performer on them and composer for them. His extant work is preserved almost complete in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book and is hardly found elsewhere.

EX. 2-7 Giles Farnaby, Daphne, mm. 1–13

Whether through Farnaby’s work or Byrd’s, or through personal contact with Philips and Bull, this type of variation writing passed to Sweelinck, who wrote the best-known examples of it, of which some are still played by organ recitalists today. The set on the French love song “Est-ce Mars?” uses a tune known far and wide in many guises. (Farnaby wrote a version under the silly name “The New Sa-Hoo”—i.e., “Say Who?”) The words as Sweelinck knew them mean, “Could this be Mars, the great battle-god, whom I espy? To judge by his arms alone, so I’d think. But at the same time it’s clear from his glances that it’s more likely Cupid here, not Mars.” Sweelinck is just as droll and whimsical as Farnaby and reaches the obligatory rhythmic peak with sextolets; but unlike his English counterpart he is concerned to show off his contrapuntal technique as well as his eccentric fancies, with a suggestion of stretto as early as the second variation and a brief canon in the last. Oddly enough, and with only a couple of exceptions, the only sacred melodies to which Sweelinck devoted variation sets were Lutheran chorales. This unexpected preoccupation on the part of a non-German, non-Lutheran organist seems to have come about as a by-product of Sweelinck’s extensive teaching activity. He was much sought after by pupils, to whom he devoted a great deal of time, and his best ones were German. For a time the three principal organ posts in Hamburg, the largest North German city, were all held by former pupils of “Master Jan Pieterszoon of Amsterdam,” which led Johann Mattheson, an eighteenth-century composer and music historian, to dub Sweelinck the “hamburgischen Organistenmacher” (the Hamburg-organist-maker).8

With his prize pupil, Samuel Scheidt (1587–1654), who came from the Saxon town of Halle in eastern Germany and apprenticed himself to Sweelinck in Amsterdam around 1608 or 1609, Sweelinck engaged in some friendly rivalry, recalling the emulationgames of the early Netherlanders. Scheidt’s monumental organ collection Tabulatura nova, issued in three volumes in 1624, contains examples of every genre that Sweelinck had practiced, including those, like the echo-fantasia, that Sweelinck had pioneered. The first volume even has a set of variations on a “cantio gallica” (French song) that turns out to be Est-ce Mars?. It was no doubt a tribute or a memorial to Sweelinck, but the pupil’s set is twice as long and twice as elaborate as the teacher’s. Also unlike Sweelinck’s, Scheidt’s set begins with a bald statement of the “theme” before proceeding to the ten variationes (singular variatio), a term that in fact first appears in print (with its modern meaning, anyway) in the Tabulatura nova.

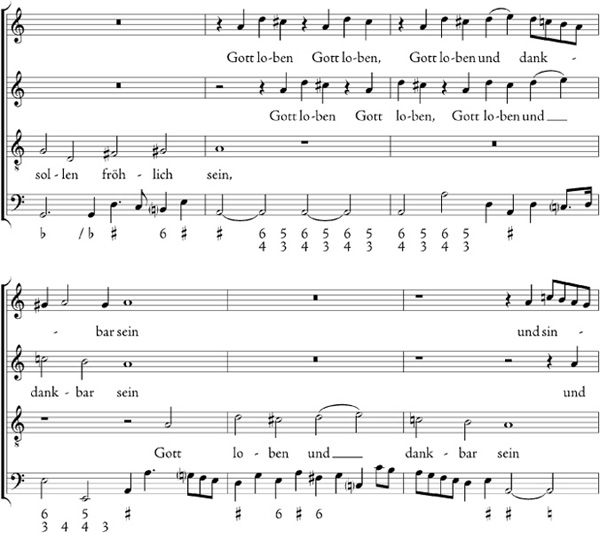

FIG. 2-4 Samuel Scheidt, woodcut from Tabulatura nova (Hamburg: Michael Hering, 1624), the earliest German keyboard publication (its title notwithstanding) printed in open mensural score rather than actual organ tablature. The sheet of music contains a four-part canon in contrary motion on the final words of the Te Deum prayer: In te, Domine, speravi; non confundar in aeternim (“In thee, O Lord, have I trusted; let me not ever be confounded”).

Yet since Scheidt worked for the Lutheran church, which unlike the Calvinist or “Reformed” church integrated organ-playing into its actual liturgy, the Tabulatura Nova contains many works in genres that Sweelinck did not compose in, and that Scheidt presumably picked up from the work of German predecessors, particularly those from the Catholic southern regions of Germany, like Hans Leo Hassler (1564–1612), who came from Nuremberg and studied with Andrea Gabrieli in Venice, or Christian Erbach (1568–1635), the Augsburg cathedral organist. The most important of these liturgical genres were the chant-based “versets,” or organ settings of alternate lines of text in Kyries, Glorias, hymns, and Magnificats. These were interpolated—alternatimfashion, as it was called—into choral or congregational performances. It was yet another instance of an “oral,” extemporized genre (one that in Germany went back at least as far as the fifteenth century) that had only lately begun the process of transformation—or ossification—into a literate one. A great many of these snippets, organized into “organ Masses” and “organ Vespers,” can be found in Book III of Tabulatura nova. As the largest collection of German liturgical organ music of the seventeenth century, Scheidt’s volumes could be thought of as the Protestant counterpart to Frescobaldi’s Fiori musicali, which came out about a decade later.

Most of Sweelinck’s chorale compositions are found in a huge manuscript of organ scores, now at the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek (German National Library) in Berlin, dating most likely from the early 1630s. It is otherwise devoted to chorale variations by a dozen or so of his German pupils, some in the form of collaborative sets, with individual variations contributed by both master and disciples.

In all these works, both Sweelinck’s own and those of the pupils, the basic technique is the same. The variations correspond to the verses of the chorale. In each of them the traditional melody is treated strictly—that is, with little or no embellishment—as a cantus firmus in a single voice. Where the secular variations keep the tune consistently in the uppermost voice, the chorale variations not only allow the lower voices to be tune-bearers in the old cantus-firmus manner but also allow the hymn tune to migrate through the texture as verse succeeds verse. The accompanying voices vary freely in number from a single one (producing a two-part or “bicinium” texture) on upwards. Sometimes they incorporate aspects of the chorale tune, thus integrating it into the polyphony; sometimes they contrast with it as countersubjects.

This, too, was a technique that Sweelinck had picked up from the English and passed along to his pupils. It corresponds exactly to the hymn-setting technique of John Bull, which derived in turn from that of Bull’s teacher, John Blitheman (ca. 1525–91), a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal from 1558 to his death. Tracing it gives us a particularly crisp example of the way in which traditions of personal emulation can serve as the means through which the larger, less personal phenomenon of stylistic dissemination takes place. A technique that English organists had developed for accompanying and supplementing choral hymnody was transferred in stages to a new geographical terrain and a new, music-hungry church, which had an even greater need for organ music to supplement a choral hymnody that had spread from the elite choir to full congregational participation. Sweelinck was the middleman who brokered the transaction.

The end result was the Lutheran chorale partita, as practiced first by Scheidt, most spectacularly by J. S. Bach, and by Lutheran organist-composers to this day. Scheidt’s partita on the “cantio sacra” Christ lag in Todesbanden (“Christ lay in death’s bondage,” a venerable Easter hymn: Ex. 2-8) comes from the second volume of Tabulatura nova, printed exactly one hundred years after the earliest polyphonic settings of the chorale had appeared. In five verses, Scheidt’s set begins with two connected settings of the chorale in the highest part: the first is an integrated motetlike setting with some old-fashioned Vorimitation (imitative foreshadowing of the cantus firmus) in the accompanying voices, of a kind that Luther himself would surely have recognized; the second is more à la Sweelinck, with successive lines of the chorale set in relief against a series of ever more rhythmically active countersubjects, each treated in imitation (Exx. 2-8a-b).

The third verse, the centerpiece, is a “free” variation: an intricate bicinium in which the individual phrases of the chorale are independently developed in dialogue between the player’s hands, sometimes broken up into motives, sometimes superseded altogether by episodes (Ex. 2-8c). The fourth and fifth variation return to a stricter cantus-firmus style. In the fourth, after a brief foreshadowing in the bass, the cantus firmus, placed in the middle voice (the “tenor”), is pitted against two exceptionally florid outer voices that sometimes develop countersubjects in imitation, sometimes contrast with one another as well as with the subject, creating toward the end an “obbligato” texture with a fast-flowing line above the tenor, a slower “walking bass” beneath it (Ex. 2-8d).

EX. 2-8A Samuel Scheidt, Christ lag in Todesbanden, first versus, mm. 1–7

EX. 2-8B Samuel Scheidt, Christ lag in Todesbanden, second versus, mm. 1–5

The fifth and last variation is presented and harmonized in a very unusual fashion that could be considered either tonally wayward (to adopt the viewpoint and expectations of an observer contemporary with Scheidt) or tonally “progressive” (to adopt the viewpoint and expectations of an observer contemporary with us). It is a fascinating case to consider, for the difference between the two historical and aesthetic vantage points is rarely so clear-cut or easily identified. Do we get more aesthetic gratification from the standpoint that sees the piece as intriguingly capricious or “deviant,” or from the one that sees it groping, so to speak, toward a more modern (familiar? higher? more integrated?) conception of tonality? Can we somehow view it from both standpoints at once?

Here is how the piece works. The bass carries the complete cantus firmus (though the “cantus” or top voice and the “tenor” also get to quote phrases from it), but its various constituent phrases are independently transposed. The music thus seems to oscillate between implied mode finals on D, on A (the upper fifth), and on G (the lower fifth), staking out the tonal areas we now think of as “tonic,” “dominant,” and “subdominant.” Particularly “modern” in its tonal effect is the last phrase in the bass, ending on A (the dominant) so as to prepare the grandiose final cadence (Ex. 2-8e).

EX. 2-8C Samuel Scheidt, Christ lag in Todesbanden, third versus, mm. 1–19

EX. 2-8D Samuel Scheidt, Christ lag in Todesbanden, fourth versus, mm. 39–44

EX. 2-8E Samuel Scheidt, Christ lag in Todesbanden, fifth versus, mm. 65–end

The Lutheran chorale partita had its vocal counterpart as well, in which sacred genres that had developed elsewhere were adapted to specifically Lutheran use. The result was the so-called chorale concerto, a mixed vocal-instrumental genre that in its more modest specimens seemed a direct outgrowth of Viadana’s pioneering Cento concerti ecclesiastici of 1602 (pirated by a German publisher seven years later) and that in its more opulent ones could vie with the most extravagant outpourings of the Venetians. Its two main exponents, besides Scheidt, were Michael Praetorius (1571–1621), organist to the Duke of Brunswick (Braunschweig), and Johann Hermann Schein (1586–1630), the cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig, where J. S. Bach would occupy the same position a hundred years later.

FIG. 2-5 Johann Hermann Schein, woodcut portrait at the Musical Instrument Museum, University of Leipzig.

Schein (like Sweelinck before him and Bach after him) was a contracted civil servant who reported to a town council, not a court or church employee who served at the pleasure of a patron. He published a great deal of secular music as well as sacred, including the Banchetto musicale (Leipzig, 1617), an early book of dances-for-listening organized into standardized sequences or suites (though Schein does not use the word). Played by ensembles of viols and violins, they probably served originally as dinner music (Tafelmusik, literally “table music”) at the noble houses where he served briefly before being elected “Thomaskantor.” Each suite in the collection consists of an old-style pair—a slow duple-metered padouana or pavan followed by a quick triple-metered gagliarda—and a new-style pair consisting of the same genres (courente and allemande, as Schein called them) that we saw in Frescobaldi. Each suite ended with a quick-time sendoff in the form of a fast triple-metered variation on the allemande called the tripla. What so distinguished Schein’s suites was his application to them of the keyboard variation technique pioneered by the virginalists and Sweelinck. The components of each suite, as Schein put it, were integrated both in mode and in “invention,” meaning that they were fashioned out of a common fund of melodic ideas so that they became in effect not only a suite but a set of variations as well.

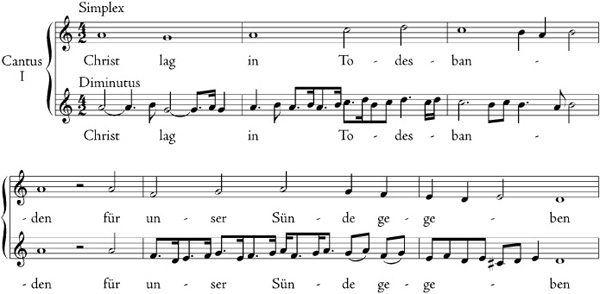

Schein made three settings of Christ lag in Todesbanden. Two of them were Cantionalsätze, simple chorale harmonizations to accompany congregational singing. The third comes from Schein’s first continuo publication, Opella nova (“A new collection of works,” 1618), which consisted, according to its title page, of geistliche Concerten auff italiänische Invention componirt: “sacred concertos composed on the Italian plan.” It is scored for two sopranos (boys) and a tenor over a very active basso continuo. For instructions in realizing his continuo parts, Schein actually referred the user of his book to the preface of Viadana’s Cento concerti.

It looks at first as though the two boys are going to sing a paraphrase of the chorale melody, but it turns out that it is only Vorimitation, preparing the way for the tenor, the true bearer of the cantus firmus. In the second part of the concerto, corresponding in the original melody to the “B” of the AAB chorale form, the boy sopranos and the tenor are pitted against one another in true concertato style (Ex. 2-9). The boys sing fanciful diminutions on the chorale phrases, full of imitations and hockets, that sound like countersubjects against the tenor’s rather stolid enunciations of the same phrases, unadorned. Take away the boys, replace them with violins or cornetts, and the piece would still be a viable chorale concerto. (In fact it might easily have been performed that way on occasion.)

EX. 2-9 Johann Hermann Schein, Christ lag in Todesbanden from Opella nova (1618), mm. 20–25

The incredibly industrious Michael Praetorius, who is said to have died pen in hand on his fiftieth birthday, produced in his relatively brief career well over a thousand compositions, most of which were issued in 25 printed collections published between 1605 and the year of his death. Except for eight chorale settings for organ and a very successful and influential book of ensemble dance music (Terpsichore, pub. 1612)—and also apart from five treatises, including the Syntagma musicum, a giant musical encyclopedia that came out in three volumes between 1614 and 1618—Praetorius’s works consist almost entirely of psalm motets (nine volumes called Musae sioniae, issued between 1605 and 1611) and chorale concerti. His most grandiose compositions were reached in what turned out to be his culminating publication, a three-volume monster issued between 1619 and 1621 and named, significantly, after the ancient Muse of oratory and sacred poetry: Polyhymnia caduceatrix et panegyrica (Polyhymnia, bringer of peace and singer of praise).

The concerti in this collection, some scored for as many as twenty-one mixed vocal and instrumental parts, were written (possibly on commission) after Praetorius had visited the court of Dresden, where the musical establishment was the envy of all Germany. The concerto on Christ lag in Todesbanden, from the second volume, is composed in such a way that it can be performed in various concerted combinations: by two boys with basso continuo, by two boys and two basses with basso continuo, or by two boys and a three- or four-part instrumental ensemble plus basso continuo, for a maximum of seven sounding parts.

In addition, when the two boys perform without competition from other concerted parts they are given the option of singing highly embellished lines—or rather, the composer supplied for them the sort of vocal diminutions more experienced singers habitually extemporized when performing concerted music. Ex. 2-10 shows how Praetorius decorated the chorale’s famous opening line. It is the rare instance like this one, where the composer went to the trouble of furnishing in advance what was normally left to the promptings of the moment, that give us our scarce and precious clues to what the written music whose physical remains we now possess really may have sounded like in life—that is, in performance.

EX. 2-10 Michael Praetorius, Christ lag in Todesbanden from Polyhymnia caduceatrix et panegyrica, vol. II (Cantus I)

All this Italianate splendor was not fated to last. The second quarter of the seventeenth century was a horrendous period for the German-speaking lands, marked by an unremitting series of territorial, dynastic, and religious conflicts collectively known as the Thirty Years War. What had started in 1618 as an abortive revolt of the Protestant nobility in Bohemia against the dominion of the Holy Roman (Austrian) Empire spread all over Germany as the Scandinavian kings to the north of Germany opportunistically took up the offensive against the Austrians to the south. By the mid-thirties the German Protestant territories were one huge blood-soaked battlefield.

A peace was declared in 1635 that gave the Empire the advantage. This antagonized France, the other great centralized European power. France joined forces with Sweden and the final stage of what had in effect become a general European war began. The German princes were forgotten as the French and the Austrians, with their various allies, contended everywhere: in the Netherlands, in Spain, in Italy, and in the north, where the Scandinavian powers were now divided. Peace negotiations were begun even before 1640, but hostilities continued sporadically until 1648. The result was a vastly weakened Austrian Empire, a vastly strengthened France, and a completely ruined Germany.

Powerful repercussions of this virtual world war were felt immediately in the arts. The military successes that made France the richest and most prosperous land in Europe laid the foundations for what the French still call their grand siècle, their Great Century. The musical results of that flowering will be the subject of the next chapter. The impoverishing effects of the war on the arts of the German-speaking countries, on the other hand, can scarcely be imagined.

The “high” or courtly arts managed to hang on through their vicissitudes, though not without crucial adaptive change. In music, that process of adaptation may be viewed with exceptional clarity thanks to the presence on the German scene of a composer of irrepressible genius, whose long career, mirroring in an intense creative microcosm the general fate and progress of his art, furnishes us with an ideal prism. His name was Henrich (or more commonly, Heinrich) Schütz. Despite the conditions in which he was forced to work, he became the first internationally celebrated German master.

Born in 1585 to a family of innkeepers in the Saxon (east German) town of Köstritz near Gera, a musical instrument center, Schütz early displayed his gifts. His singing voice was noticed by a music-loving nobleman, the Landgrave Moritz of Hessen, who happened to stay at his father’s inn in 1598, when the boy was just entering adolescence. Over the objections of his parents, the Landgrave had the lad brought to his residence in Kassel for instruction and training “in all the good arts and commendable virtues.” After his voice changed, Schütz ostensibly gave up music for university studies in law, also underwritten by Landgrave Moritz, who had become a surrogate father to him.

But then one day in 1609, when his protégé was twenty-four, the Landgrave came to visit him at school with a proposition: “Since at that time a very famous if elderly musician and composer was still alive in Italy,” as Schütz recounted his patron’s words in old age, “I was not to miss the opportunity of hearing him and gaining some knowledge from him.”9 Since the proposal was backed up with a generous cash stipend, the young man “willingly accepted the recommendation with submissive gratitude,… against my parents’ wishes.”

FIG. 2-6 Heinrich Schütz, portrait by Christoph Spetner (ca. 1650) at the University of Leipzig.

The musician in question was Giovanni Gabrieli. Schütz spent three years in Venice under his tutelage, right up until the master’s death, by which time the young Saxon had become his prize pupil. “On his deathbed,” Schütz recalled, “he had arranged out of special affection that I should receive one of the rings he left behind as a remembrance of him.” This gift not only signaled the passing of the Venetian musical heritage to a new generation, but also symbolized its becoming, through Schütz, an international standard.

The year before, Schütz had composed a book of Italian madrigals that Gabrieli thought worthy of publication. It was issued in Venice in 1611 with an attribution to Henrico Sagittario allemanno—“Henry Archer (i.e. Schütz) the German”—but its contents are completely indistinguishable in style from the native product. Schütz wanted nothing else. He went back to Germany in 1613 with the intention of fulfilling his promise to his patron by adapting the glorious Venetian style to the needs of the Lutheran church, just as Praetorius and others were also doing, but with the added benefit of authenticity arising out of training at the source.

For the rest of his life Schütz saw himself primarily as the bringer of Italianate “light to Germany” (as his tombstone reads), and saw the composition of grand concerted motets and magnificent court spectacles as his true vocation. Given that ambition, his career was dogged by cruel frustration. His actual contributions, not only to the musical life of his time but to the historical legacy of German music, tallied little with his intentions. But his musical imagination was so great, and his powers of adaptation so keen, that what he did accomplish was arguably a greater fulfillment of his gifts than what he set out to achieve.

On returning to Germany with his sterling credentials, Schütz went back to work, as expected, for Landgrave Moritz of Hessen. The very next year, however, the Elector of Saxony, a personage far superior in rank to the Landgrave, called Schütz to his legendarily appointed court at Dresden, the very court that Praetorius was adorning so splendidly with his Polyhymnia motets, and Moritz had to release him. Schütz arrived in 1615 and spent his entire subsequent career at Dresden (from 1621 as court Kapellmeister), serving faithfully through thick and thin for almost sixty years.

FIG. 2-7 Schütz directing his choir at the Dresden court chapel. Copperplate engraving from the title page of his pupil Christoph Bernhard’s Geistreichen Gesangbuch (“Artful songbook”) of 1676.

At first the times were “thick,” indeed downright opulent. Schütz’s first German publication, issued at Dresden in 1619, was Psalmen Davids (“The psalms of David”) a book of twenty-six sumptuous concerted motets for up to four antiphonal choruses with continuo (“organ, lute, chitarrone, etc.,” according to the title page) and parts for strings and brass ad libitum. There are also archival records of gala court performances of secular compositions by the young Kapellmeister. They included “The Miraculous Transport of Mount Parnassus” (Wunderlich Translocation des … Berges Parnassi), a mythological ballet performed for the visiting Holy Roman Emperor Matthias, and a polychoral birthday ode for the Elector on the subject of Apollo and the Muses. The most tantalizing such reference is to an opera, the first ever composed to a German text, on the time-honored subject of Apollo and Daphne, for the marriage of his first patron’s son to his second patron’s daughter. The libretto was in fact an adaptation by a court poet of Rinuccini’s libretto for Peri’s Dafne of 1597, the first musical tale of all. Except for the early book of madrigals, though, Schütz’s secular output, comprising as well an Orpheus opera and a whole series of court ballets, has perished with only the most negligible exceptions. The five hundred or so works by which he is known to us are virtually all sacred.

And from his Latin-texted Cantiones sacrae of 1625 to his German-texted Geistliche Chor-Music of 1648, Schütz’s output reflects to varying degrees the austerity of wartime conditions, when court establishments were decimated by conscription and budgets for the fine arts were ruthlessly slashed. Schütz was forced to renounce the polychoral style in favor of simpler choral textures and even sparser forces. In 1628, he issued a new collection of settings from the Psalter, again called Psalmen Davids. But where the first collection, counting on the Dresden court chapel forces at their most lavish, had assumed the grand manner, the new one consisted of simple part-songs with continuo, based on metrical psalm paraphrases by Cornelius Becker, a Leipzig churchman, which (as the “Becker Psalter”) were then popular.

Faced with increasingly difficult conditions in Dresden, Schütz petitioned for leave so that he could visit Venice again and wait out the war. He departed in August 1628 and stayed for about a year. He seems to have become acquainted this time with Monteverdi, now the maestro di cappella at St. Mark’s, and to have experimented on the scene with the new declamatory styles that Monteverdi had pioneered. While in Italy he published a book of fifteen sacred concerti to Latin texts, which he called Sacrae symphoniae in tribute to his late teacher Gabrieli, who had published a similarly titled collection in 1597. These are comparatively modest works, scored for one or two solo voices (in one case for three) with obbligato instrumental parts. Only one of them is antiphonal in the literal sense of employing spatially separated ensembles, but all of them remain Venetian in spirit by extracting a maximum of color and interplay out of their reduced forces.

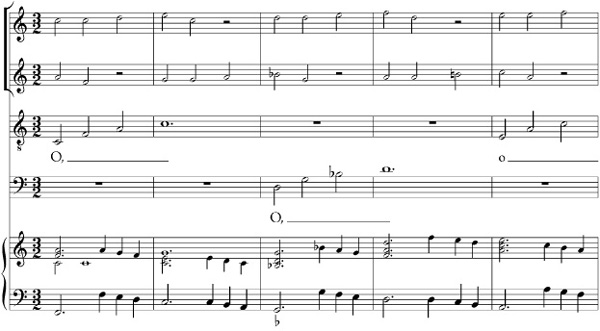

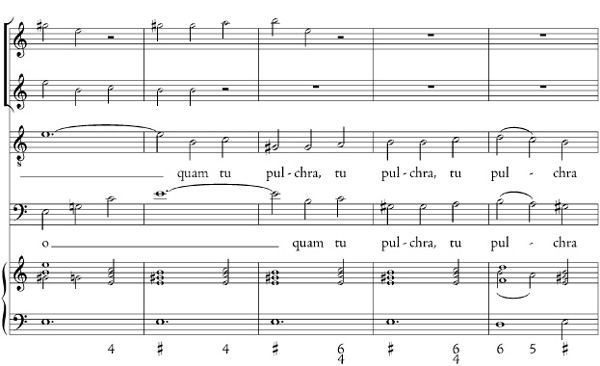

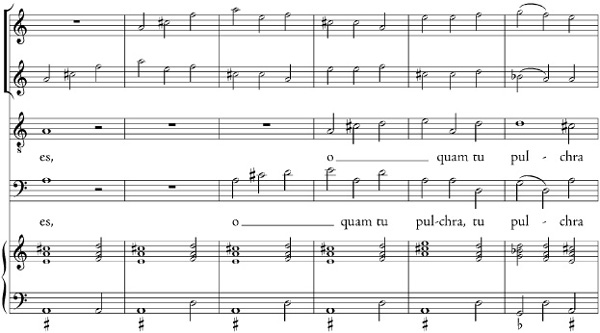

O quam tu pulchra es (“O how comely art thou”), one of the best known items from Schütz’s Symphoniae sacrae of 1629, is set to a text from the Song of Songs that had already served countless composers going back as far as the early fifteenth century (see “Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century” chapter 11). The reason for its popularity, and also the reason why this particular concerto of Schütz has served so long as a favorite introduction to his work, surely lies in the spectacularly erotic text, replete with a catalogue of the beloved’s anatomy, that furnished Schütz, as it had furnished his predecessors, with both a wonderful opportunity to display the attractions of a new “luxuriant” style, and a pretext for pushing the style to new heights of allure.

The term “luxuriant style” (stylus luxurians), meaning a style brimming abundantly with exuberant detail in contrast to the “plain style” (stylus gravis) of old, was coined by Christoph Bernhard (1628–92), Schütz’s pupil and eventual successor as the Dresden Kapellmeister, in a famous treatise on composition that circulated widely in manuscript in the later seventeenth century and was widely presumed to transmit Schütz’s teachings. What mainly abounded in the luxuriant style was dissonance, which makes the stylus luxurians the rough equivalent of what Monteverdi called the seconda prattica.

Like Monteverdi, Bernhard stipulated that freely handled dissonances arose out of (and were justified by) the imagery and emotional content of a text.10 They were an aspect of rhetoric: ornamental figures, so to speak, of musical speech. That is why Bernhard called them figurae (Figuren in German), and why his theory of composition, which treats the novel dissonances of the luxuriant style as ornaments on the surface of the plain style, is known as the Figurenlehre (the doctrine of figures). Bernhard’s Figurenlehre, which may derive from Schütz’s own take on Monteverdi, was the first of many theories of composition, mainly put forth by German writers, that conceptualized and analyzed music in terms of an ornamental surface projected over a structural background.

But the stylus luxurians was anything but a passive response to the contents of a text. On the contrary, and as O quam tu pulchra es shows especially well, the composer actively shaped the text to his musical purposes even as he shaped the music to conform to the text’s specifications. It was a process of mutual enhancement and intensification—indeed, of mutual impregnation—that bore an offspring more powerfully expressive than either words or music alone could be.

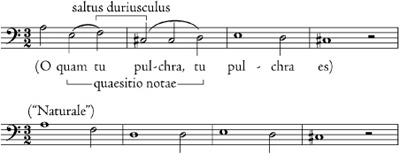

Reading Schütz’s setting of the concerto’s opening words in terms of Bernhard’s opposition of plain background and luxuriant surface (Ex. 2-11a), we might characterize it as descending through the notes of the tonic triad (A–F–D in D minor) with lower neighbors (“overshooting”—quaesitio notae, literally “searching for the note”—in Bernhard’s parlance) decorating the F and the D in the manner of what we would now call an appoggiatura (see Bernhard’s illustration of the practice in Ex. 2-11b). The neighbor to the root of the triad is raised a half step to function as a leading tone, resulting in a diminished fourth—in Bernhard’s parlance a “hard leap” (saltus duriusculus)—from F to C . This chromaticized interval coincides by finely calculated design with the main “operator” in the text, the word pulchra, or “beautiful”.11

. This chromaticized interval coincides by finely calculated design with the main “operator” in the text, the word pulchra, or “beautiful”.11

The lilting triple-metered refrain thus created is heard again and again over the course of the concerto. After addressing a series of endearments to the bride that intensify through sequences to a drawn-out hemiola cadence, the baritone soloist returns to the opening phrase, this time joined by the tenor in imitation. When the pair of vocal soloists have repeated the baritone’s invocation to the bride, the opening phrase jumps up into the range of the instrumental soloists, the violins, who fashion from it a sinfonia or wordless interlude—wordless, but still texted in a way, since the opening melody has been so strongly associated with the opening words. Finally, the vocal soloists join the violins for a final invocation in four parts over the basso continuo to finish off the first section of the concerto.

EX. 2-11A First line of Heinrich Schütz’s O quam tu pulchra es rhetorically parsed

EX. 2-11B Christoph Bernhard, example of Quaesitio notae

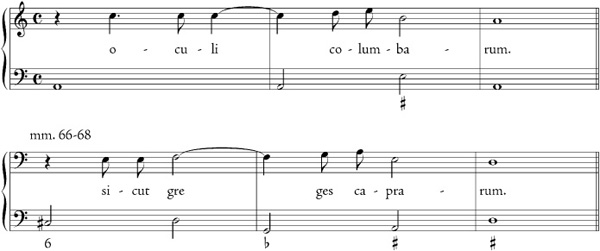

From this point on the text of the concerto consists of the famous inventory of the bride’s body, in which every part named is made the object of a vivid simile—a verbal figure. Since the music performs a similar “figurative” function, Schütz radically abridged the text, leaving most of the actual work of description to the music. This gives him time to bring back the opening phrase in both words and music as a ritornello to follow each item in the enumeration. Its dance like triple meter contrasts every time with the freer declamatory rhythms of the simile verses.

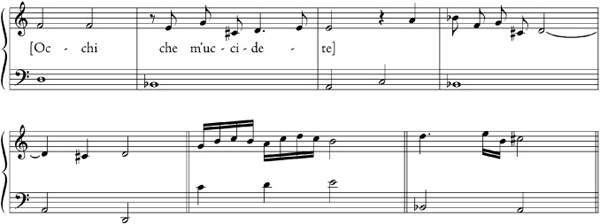

The first simile is the most straightforward; the beloved’s eyes are compared with the eyes of a dove. The music is comparably straightforward, consisting of recitative in what for Schütz was a new style. The next, comparing her hair (presumably as it is blown by the wind) with a flock of (frisking) goats, is matched by trills and wide leaps in the music. The cadence on greges caprarum (mm. 66–67) is similar to that on oculi columbarum (mm. 56–57), but is intensified harmonically very much à la Monteverdi: by interpolating the subdominant (G) in the bass, the melody note (F) is turned into a dissonant suspension that does not resolve directly, but only through an intervening ascent to a more strongly dissonant ninth (A), from which a (goatlike?) leap is made to the note that would have resolved the original suspension by step (Ex. 2-12a). In such a passage it is especially easy to see the “structural” voice leading that underlies the frisky “ornamental” figures on the surface.

After a return to recitative for the simile comparing the bride’s teeth to the whiteness of shorn sheep, there is a steady increase in musical floridity with every extravagant textual figure. From here on the tenor and baritone are in constant, quasi-competitive duet, their intertwining lines suggesting the scarlet ribbon to which the beloved’s lips are compared, the winding staircases that encircle the tower to which her long neck is likened (Ex. 2-12b), and the cavorting of the twin fawns that symbolize (the jiggling of) her two breasts (Ex. 2-12c). The last being an especially potent sexual symbol, it is played out at length, with the violins at last taking part in the simile.

EX. 2-12A Heinrich Schütz, O quam tu pulchra es (Symphoniae sacrae I), mm. 56–58, mm. 66–68

EX. 2-12B Heinrich Schütz, O quam tu pulchra es (Symphoniae sacrae I), mm. 91–95

EX. 2-12C Heinrich Schütz, O quam tu pulchra es (Symphoniae sacrae I), mm. 100–111

It is followed by what is quite obviously a musical representation of a sensual climax, the violins’ mounting arpeggios introducing a passage in which the singers vocalize on similar arpeggio figures, their text shrunk back to mere moaning iterations of the opening O, and with the violins now sounding the aching saltus duriusculus (the diminished fourth) not as a neighbor but as a harmonic interval, producing arpeggios of augmented triads. The baritone, it seems hardly necessary to add, reaches his highest note on his final O. The final cadence is packed with extra cathartic force by adding arbitrarily to its dissonance: the tenor’s C, on the “purple” word pulchra, is not only a dissonance approached by leap but also a false relation with respect to the C immediately preceding it in the baritone and basso continuo parts (Ex. 2-12d). (The apparent ending on the dominant is resolved by the next concerto in the collection, Veni de Libano, set to a continuation of the same passage from the Song of Songs.)

immediately preceding it in the baritone and basso continuo parts (Ex. 2-12d). (The apparent ending on the dominant is resolved by the next concerto in the collection, Veni de Libano, set to a continuation of the same passage from the Song of Songs.)

The most remarkable aspect of O quam tu pulchra es is the refrain. There was nothing new, of course, about the idea of the refrain as such. It was one of the most ancient of all musical and poetical devices, with a literally prehistoric origin. The way Schütz employs it here, however, it acts in a double role—or rather, it combines two roles in a singularly pregnant way. It is of course a musical (or “structural”) unifier, quite a necessary function in a composition that otherwise sets so many contrasting textual images to contrasting musical ideas. It is at the same time the bearer of the central affective message both of the text and of the music, its constantly reiterated and intensifying diminished fourth saturating the whole with the “lineaments of desire,” to borrow a neat phrase from the English Romantic poet William Blake. The refrain, being both the concerto’s structural integrator and its expressive one, erases any possible line between the expressive and the structural. From now on, musical ideas would tend increasingly to function on this dual plane; ultimately that is what one means by a musical “theme.”

EX. 2-12D Heinrich Schütz, O quam tu pulchra es (Symphoniae sacrae I), mm. 112–end

Schütz returned from his second Italian sojourn to find conditions in Germany greatly worsened. The war economy interfered more directly with musical opportunities than ever, and in the autumn of 1631 Saxony became an active belligerent in alliance with Sweden. Most of Schütz’s singers were drafted into the army; by 1633, the Dresden musical establishment, once the envy of Germany, was to all intents and purposes disabled, “like a patient in extremis,” as Schütz put it in a letter to his patron, and so it remained until the mid 1640s. The Gabrielian side of Schütz’s Venetian heritage was deprived of an outlet. “I am of less than no use,” the unhappy composer complained in another letter from the time. The only gainful employment he had during this dismal period came from courts to the north and west that continued to function, particularly that of King Christian IV of Denmark in Copenhagen, which Schütz was permitted to visit from 1634 to 1635 and again from 1642 to 1644, and that of Hildesheim, where he spent some months from 1640 to 1641.

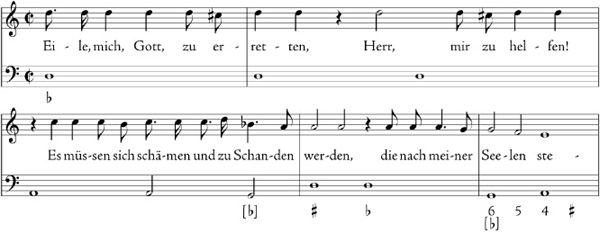

During these bleak years Schütz’s “Monteverdian” side came into its own, as if by default. In 1636 and in 1639 he published collections of what he called Kleine geistliche Concerte or “Little Sacred Concertos,” vastly scaled-down compositions for from one to five solo voices with organ continuo, completely without the use of concertante instruments (with one exception, a dialogue setting of the Ave Maria in the second book). These ascetic compositions were characterized not only by drastically curtailed forces but by a mournfully penitential, subjective mood as well. The ones for single solo voices and continuo, performable by only two musicians, were perhaps the most characteristic of the lot, amounting to what Italian musicians would have called sacred monodies in recitative style, or (as Schütz called it) the stylus oratorius.

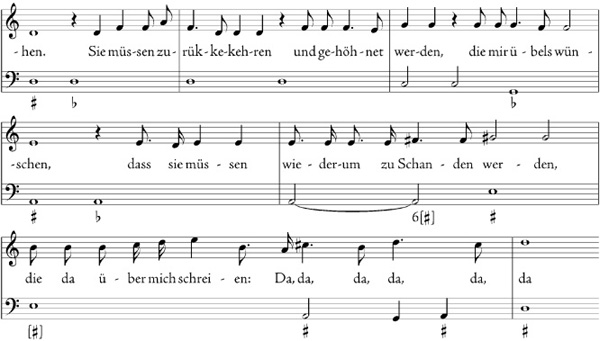

The opening concerto in the first book, Eile mich, Gott, zu erretten (“Hasten, O God, to deliver me!”), a complete setting of the tiny Psalm 70, sets the tone (Ex. 2–13). In this earliest German recitative (labeled in stylo oratorio—“in the style of an oration”—in the original print), the flamboyance of Schütz’s earlier style is replaced by terse declamation. There is not a single melisma. Emphasis comes not from a proliferation of notes but from repetition of key words and phrases, usually without any corresponding repetition of music. A certain amount of word-painting remains—the melody “turns back” on itself on the word zurückekehren in mm. 6–7; the words hoch gelobt (“highly praised”) are repeated in mm. 14–15 on the way to a high note—but it is very restrained. Instead of seeking out madrigalian imagery, Schütz now seems bent on distilling a more generalized, concentrated emotion in the spirit of Monteverdi’s seconda prattica, achieving it through dissonant leaps (see especially the taunts in mm. 11–12) and syncopated rhythms.

Perhaps the most poignant reminder of the straitened circumstances in which Schütz was now forced to work is the puny little symphonia between the stanzas of the psalm (just after Ex. 2-13 breaks off), a single optional (si placet) measure scored for just the bare figured bass. The absence of any tune save what the organist may extemporize searingly dramatizes the absence of the court instrumentalists whose corpses were piling up on the Saxon battlefields.

EX. 2-13 Heinrich Schütz, Eile mich, Gott, zu erretten (Kleine geistliche Concerte I), mm. 1–16

In Schütz’s new-found techniques of poignant text-expression, we may observe the beginnings of a tendency that would reach a remarkable climax in the Lutheran music of the coming century: the deliberate cultivation of ugliness in the name of God’s truth, an authentic musical asceticism. It is often thought to be a specifically German aesthetic, and as evidence of a special Germanic or Protestant profundity of response to scripture (as distinct from Italianate pomp and sensuality). And yet the musical means by which it was accomplished, as Schütz’s career so beautifully demonstrates, were nevertheless rooted in Catholic Italy. Schütz was only the father of modern German music to the extent that he served as conduit for those Italianate means.

Rebuilding of the impoverished German courts and their cultural establishments could only begin after the signing of the Peace of Westphalia on 24 October 1648, which effectively terminated the Holy Roman Empire as an effective political institution (although it would not be formally dissolved until 1806). The German Protestant states, of which Saxony was one, were recognized as sovereign entities, leaving only France as a united and centralized major power on the continent of Europe. Schütz’s patron, the Elector Johann Georg, emerged from the war as one of the two most powerful Protestant princes of Germany. (The other was the Elector of the state of Brandenburg, which later became the kingdom of Prussia.)

Schütz’s last publications reflected these improved fortunes. In 1647 he issued a second book of Symphoniae sacrae, scored like the first for modest vocal/instrumental forces, but with texts in German. The next year saw the publication of his Geistliche Chor-Music, beautifully crafted polyphonic motets specifically intended for performance by the full chorus rather than favoriti or soloists. Finally, in 1650, aged sixty-five, he issued what is now thought of as his testamentary work, the third book of Symphoniae sacrae, scored for forces of a size he had not had at his disposal since the time of the Psalmen Davids. The music, though, was still characterized by the terseness and pungency of expression he had cultivated during the lean years. Schütz’s Gabrielian and Monteverdian sides had met at last in a unique “German” synthesis.

One of the crowning masterworks in this final collection is Saul, Saul, was verfolgst du mich, scored for six vocal soloists, two choruses, and an instrumental contingent consisting of two violins and violone (string bass), all accompanied by a bassus ad organum (continuo). The text consists of two lines from the Acts of the Apostles (chapter 7, verse 14), containing the words spoken by Christ to the Jewish priest Saul on the road toward Damascus. As Saul, according to the Biblical account, later reports to Agrippa I, the grandson of King Herod:

I myself once thought it my duty to work actively against the name of Jesus of Nazareth; and I did so in Jerusalem…. In all the synagogues I tried by repeated punishment to make them renounce their faith; indeed my fury rose to such a pitch that I extended my persecution to foreign cities.

On one such occasion I was travelling to Damascus with authority and commission from the chief priests; and as I was on my way, Your Majesty, in the middle of the day I saw a light from the sky, more brilliant than the sun, shining all around me and my travelling-companions. We all fell to the ground, and then I heard a voice saying to me in the Jewish language, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? It is hard for you, this kicking against the goad.” I said, “Tell me, Lord, who you are”; and the Lord replied, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But now, rise to your feet and stand upright. I have appeared to you for a purpose: to appoint you my servant and witness, to testify both to what you have seen and to what you shall yet see of me” (translation from The New English Bible).

Thus did Saul become the Apostle Paul. The italicized words are the ones that form the text of Schütz’s concerto. It is no straightforward setting, but one designed to fill in a great deal of the surrounding narration of Paul’s miraculous conversion by means of dramatic symbolism. The words echo and reecho endlessly in the prostrate persecutor’s mind, which we who hear them seem to inhabit. The echo idea is portrayed in the music not only by repetition but also by the use of explicitly indicated dynamics, something pioneered in Venice by Schütz’s first teacher.

The musical phrase on which most of the concerto is built is sounded immediately by a pair of basses, then taken up by the alto and tenor, then by the sopranos, and finally by the pair of violins as transition into the explosive tutti. (Divine words were often set for multiple voices, so as to depersonalize them and prevent a single singer from “playing God.”) The syncopated repetitions of the name Saul are strategically planted so that, when the whole ensemble takes them up, they can be augmented into hockets resounding back and forth between the choirs, adding to the impression of an enveloping space and achieving in sound something like the effect of the surrounding light described by the Apostle. The words was verfolgst du mich (“Why dost thou persecute me?”) are often set in gratingly dissonant counterpoint: a suspension resolution in the lower voice coincides with an anticipation in the higher voice, producing a brusque succession of parallel seconds (later known, albeit unjustly, as a “Corelli clash” owing to its routinized use in Italian string music).

The second sentence of text is reserved for the soloists (favoriti), whose lines break out into melismas on the word löcken (lecken in modern German), here translated as “kick.” Against this the two choirs and instruments continually reiterate the call, “Saul, Saul,” as a refrain or ritornello. In the final section of the concerto, the soloists declaim the text rapidly in a manner recalling Monteverdi’s stile concitato. Meanwhile, the tenor soloist calls repeatedly on Saul, his voice continually rising in pitch from C to D to E, the two choirs interpreting these pitches as dominants and reinforcing each successive elevation with a cadence, their entries marking “modulations” from F to G to A, the last preparing the final return to the initial tone center, D (Ex. 2-14).

The ending, rather than the climax that might have been expected, takes the form of reverberations over a fastidiously marked decrescendo to pianissimo, the forces scaled down from tutti to favoriti plus instruments, and finally to just the alto and tenor soloists over the continuo, the fadeout corresponding to the Apostle’s “blackout,” his loss of consciousness on the road to Damascus. Through the music we have heard Christ’s words through Saul’s ears and shared his shattering religious experience. Schütz has in effect imported the musical legacy of the Counter Reformation into the land of the Reformation, reappropriating for Protestant use the musical techniques that had been originally forged as a weapon against the spread of Protestantism.

EX. 2-14 Heinrich Schütz, Saul, Saul, was verfolgst du mich (Symphoniae sacrae III), mm. 67–74

Schütz’s largest surviving works are oratorios, or as he called them, Historien—Biblical “narratives,” in which actual narration, sung by an “Evangelist” or Gospel reciter, alternates with dialogue. Oratorios were most traditionally assigned to Easter week, when the Gospel narratives of Christ’s suffering (Passion) and Resurrection were recited at length. Sure enough, of Schütz’s six Historien, five were Easter pieces: a Resurrection oratorio composed early in his career, in 1623; a setting of Christ’s Seven Last Words from the Cross, evidently from the 1650s; and three late settings of the Passion according to the Apostles Matthew, Luke, and John, respectively. These last, in keeping with Dresden liturgical requirements for Good Friday, are austerely old-fashioned a cappella works in which the chorus sings the words of the crowd (turbae), and the solo parts (the Evangelist, Jesus, and every other character whose words are directly quoted) are written in a kind of imitation plainchant for unaccompanied solo voices.

The remaining oratorio, called Historia der freuden- und gnadenreichen Geburth Gottes und Marien Sohnes, Jesu Christi, unsers einigen Mitlers, Erlösers und Seeligmachers (“The Story of the Joyous and Gracious Birth of Jesus Christ, Son of God and Mary, Our Sole Intermediary, Redeemer and Savior”), performed in Dresden in 1660, is by contrast a thoroughly Italianized, effervescent outpouring of Christmas cheer in which the Evangelist’s part (printed by itself in 1664) is in the style of a continuo-accompanied monody. The words given to the other soloists (Herod, the angel, the Magi) and chorus in ever-changing combinations are set as eight little interpolated songs (Intermedia), accompanied by a colorful assortment of instruments: recorders, violins, cornetti, trombones, and “violettas,” the last probably meaning small viols; and there are introductory and concluding choruses—the former announcing the subject, the latter giving thanks—in which voices resound antiphonally against echoing instrumental choirs in a manner recalling the Venetian extravaganzas of the composer’s youth.

The chief Italian composer of oratorios in the time of Schütz was Giacomo Carissimi (1605–74), a Roman priest who served as organist and choirmaster at the Jesuit German College (Collegio Germanico) from 1629 until his death. His fourteen surviving works in the genre probably represent only a fraction of the biblical narratives he composed, beginning in the 1640s, for Friday afternoon performances during Lent at the college and at other Roman institutions, notably the Oratorio del Santissimo Crocifisso (Oratory of the Most Holy Crucifix), which lent its name to the genre. His many foreign pupils at the College included Christoph Bernhard, who had already trained with Schütz, and the French composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier, who brought the practice of setting dramatic narratives from the Latin bible back with him to his native country.

Jephte, Carissimi’s most famous biblical narrative, was composed no later than 1649 (the date on one of its manuscripts). The story, from the Book of Judges (chapter 11), is a celebrated tale of tragic expiation. The Israelite commander Jephte vows that if God grants him victory over the Ammonites, he will sacrifice the first being who greets him on his return home. That turns out to be his beloved daughter, a virgin, who is duly slaughtered after spending two months on the mountaintop with her companions, lamenting her fate.

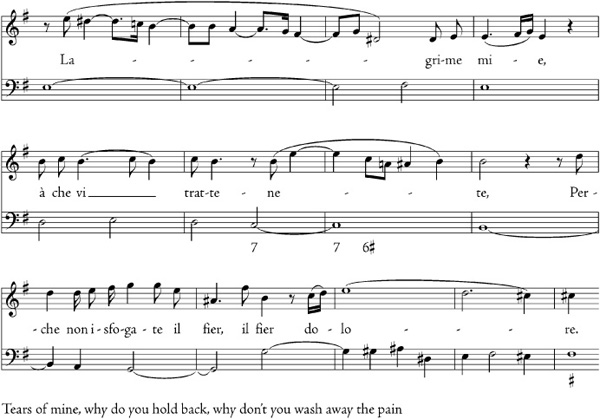

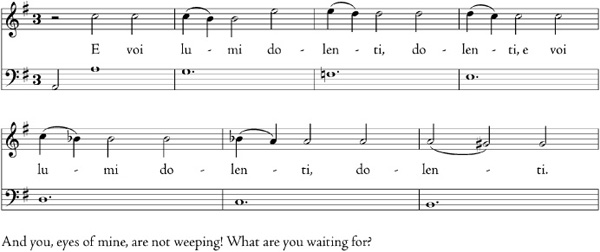

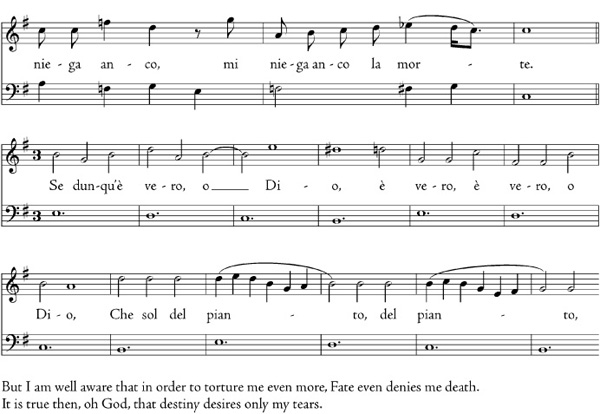

FIG. 2-8 Jephte recognizes his daughter. Painting by Giovanni Francesco Romanelli (1610–1662).

The last part of Carissimi’s setting, consisting of two laments, the daughter’s and (in the final chorus) the community’s, is introduced by a portion of narrative text sung by the historicus, as Carissimi calls the narrator’s part. (In Carissimi’s setting, the function of historicus is a rotating one, distributed among various solo voices and, as here, even the chorus.) The daughter’s lament, a monody in three large strophes, makes especially affective use of the “Phrygian” lowered second degree at cadences, producing what would later be called the Neapolitan (or “Neapolitan-sixth”) harmony. These cadences are then milked further by the use of echo effects that suggest the reverberations of the daughter’s keening off the rocky face of the surrounding mountains and cliffs. Like Schütz (in Saul, Saul), Carissimi uses the music not only to express or intensify feeling, but to set the scene. The double and even triple suspensions (on lamentamini, “lament ye!”) in the concluding six-part chorus are a remarkable application of “madrigalism” to what is in most other ways a typically Roman exercise in old-style (stile antico) polyphony. Its emotional power was celebrated and widely emulated. The chorus was quoted and analyzed by Athanasius Kircher in his music encyclopedia Musurgia universalis (Rome, 1650), and “borrowed” almost a hundred years later by Handel (who also wrote a Jephtha) for a chorus in the oratorio Samson.

Carissimi’s other major service appointment was as maestro di cappella del concerto di camera (director of chamber concerts) for Queen Christina of Sweden (1626–89), patroness of the philosopher René Descartes, who lived in Rome following her notorious abdication in 1654 and subsequent conversion to Catholicism. For her, and for many another noble salon, Carissimi turned out well over one hundred settings of Italian love poetry in a new style known generically as cantata (a “sung” or vocal piece as opposed to sonata, a “played” or instrumental one).