To cap the point on which the previous chapter came to rest, and appreciate the range and depth to which subjective emotional declaration could now be brought within the reach of late eighteenth-century instrumental style, consider a symphonic movement by Mozart, Haydn’s great contemporary, whose short life came to an end during Haydn’s first London tour. Owing to the vastly different conditions of his career, symphonies and quartets were never as central to Mozart’s output as they were to Haydn’s—or rather, they attracted his intense interest only rather late in the game, not long before its premature termination. Until the mid-1780s, they remained for him light entertainment genres. For Mozart, the symphony, especially, remained close to its sources in the opera pit and its frequent garden-party function. One of his best-known symphonies, no. 35 in D, subtitled “Haffner,” was actually composed (as late as July 1782) as a serenade to entertain a party celebrating the ennoblement of a Mozart family friend, and became a concert symphony by losing its introductory march and its second minuet.

Mozart’s instrumental style underwent an appreciable deepening after his move to Vienna in his late twenties and the start of a risky new life as a “free artist.” Meeting Haydn and playing quartets with him—Haydn on violin, Mozart on viola—was one of the catalysts. Mozart wrote a set of six quartets—“the fruits of long and laborious endeavor,” he called them—as if in direct response to Haydn’s op. 33 (then Haydn’s latest works) and published them in 1785 with a title page announcing that they were Dedicati al Signor Giuseppe Haydn, Maestro di Cappella di S. A. il Principe d’Esterhazy &c &c, Dal Suo Amico W. A. Mozart, Opera X (“Dedicated to Mr. Joseph Haydn, Music Director to His Highness the Prince of Esterhazy, etc. etc., by his friend W. A. Mozart, op. 10”).1 The features of texture and motivic saturation that so distinguished Haydn’s quartets were a powerful stimulus to Mozart’s imagination, with results that caused an astonished Haydn to exclaim to Leopold Mozart (at another Vienna quartet party), “Before God, and as an honest man, I tell you that your son is the greatest composer known to me in person or by name. He has taste, and, what is more, the greatest knowledge of composition.”2

What he did not have was a steady job. In the years following his boot from Salzburg, Mozart lived what was by comparison with Haydn, or even with his own father, the life of a veritable vagabond, enjoying a precarious love-hate relationship with a fickle public and its novel institutions of collective patronage. The very fact that Mozart dedicated his quartet volume to Haydn rather than to a prospective noble patron is an indication of his unusually autonomous, hazardous, and self-centered existence. For his livelihood he relied most on something Haydn did not have: surpassing performance skills. Mozart’s most characteristic and important instrumental music, for that reason, usually involved the piano. Because they did not, symphonies and quartets had perforce to take a back seat.

FIG. 11-1 Five-octave piano customary in Mozart’s time (Ferdinand Hoffman, Vienna).

But in the summer of 1788, in the happy aftermath of the Vienna première of Don Giovanni, Mozart composed the three symphonies that turned out to be his last: no. 39 in E , K. 543 (finished 26 June); no. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (finished 25 July); no. 41 in C, K. 551 (known as “Jupiter,” finished 10 August). They are not known to have been commissioned for any occasion; and while Mozart surely hoped to make money from them, either by putting on subscription concerts or selling them to a publisher, they seem (like the “Haydn” quartets) to have been written “on spec,” as the saying now goes among professionals—without immediate prospects, on the composer’s own impulse, at his own risk.

, K. 543 (finished 26 June); no. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (finished 25 July); no. 41 in C, K. 551 (known as “Jupiter,” finished 10 August). They are not known to have been commissioned for any occasion; and while Mozart surely hoped to make money from them, either by putting on subscription concerts or selling them to a publisher, they seem (like the “Haydn” quartets) to have been written “on spec,” as the saying now goes among professionals—without immediate prospects, on the composer’s own impulse, at his own risk.

This was not then a “normal” modus operandi for musicians; in somewhat hyperbolical historical hindsight these works loom as the earliest symphonies to be composed as “art for art’s sake”—or, at the very least, for the sake of the composer’s own creative satisfaction. (This of course is not in the least to imply that other composers did not derive satisfaction from their achievements; only that under conditions of “daily business” such as eighteenth-century musicians thought normal, creative satisfaction was the result of their effort, not its driving force.) Is there anything about their style, craft, or content that reflects this unusual status?

An argument could certainly be made that they are more reflective than most “public” music of the kind of subjectivity associated—like the very act of composing “for no reason”—with romanticism. It is a point similar to one made in a previous chapter about Mozart’s operatic music and its emotional iconicity, its way of appearing, through the exact representation of “body language,” to offer an internal portrait of a character to which listeners could compare their own inner life. The difference, of course, is that in the case of a symphony there is no mediating, “objectively” rendered stage character; there is only the “subject persona” evoked by the sounds of the music, easily (and under romanticism, conventionally) associated with the composer’s own person. There is no hard evidence to support the view that Mozart’s music contains a Romantic emotional self-portrait; there is just the widespread opinion of his contemporaries, and the supposition that the composer, late in life, may have subscribed to what was fast becoming a conventional code.

The supposition is often supported by citing the virtually operatic first movement of the G-minor Symphony, with its atmosphere of pathos, so unlike the traditional affect of what was still regarded in Vienna as party (or at least as festive) music. That atmosphere is conjured up by two highly contrasted, lyrical themes, a wealth of melting chromaticism, and a high level of rhythmic agitation. As with Haydn’s extraordinary concision, Mozart’s lyrical profusion is perhaps his most conspicuous feature. And yet it would be a pity to overlook, in our fascination with Mozart’s prodigal outpouring of seemingly spontaneous emotion, the high technical craft with which a motive derived from the first three notes of the first theme—exactly as in Haydn’s “Joke” Quartet (Ex. 10-6)—is made to pervade the whole musical fabric, turning up in all kinds of shrewd variations and contrapuntal combinations. It is the balance between ingenious calculation and (seemingly) ingenuous spontaneity, and the way in which the former serves to engineer the latter, that can so astonish listeners in Mozart’s instrumental music.

Mozart was keenly aware of the relationship in his work between ingenuity of calculation and spontaneity of effect, and the special knack he had for pleasing the connoisseurs without diminishing the emotional impact of his music on the crowd. His letters are full of somewhat bumptious comments to the effect that (to quote one, to his father, from 1782): “there are passages here and there from which only Kenner can derive satisfaction; but these passages are written in such a way that the less learned (nicht-kenner) cannot fail to be pleased, though without knowing why.”3

So it is no exaggeration to claim that when Mozart is functioning at the top of his form, it is precisely the hidden craft that creates the impression of intense subjective emotion, and that without the concealed devices that only technical analysis can uncover, the emotion could never reach such intensity. A matchless case in point is the slow second movement of the Symphony no. 39 in E , K. 543, the first of the “self-motivated” and possibly self-centered 1788 trilogy. What follows will be the closest technical analysis yet attempted in this book, focusing in as it will on the career of a single pitch over the course of the movement (so keep the score at hand). Ultimately, however, the object of analysis will be not so much the recondite technical means as the palpable expressive achievement.

, K. 543, the first of the “self-motivated” and possibly self-centered 1788 trilogy. What follows will be the closest technical analysis yet attempted in this book, focusing in as it will on the career of a single pitch over the course of the movement (so keep the score at hand). Ultimately, however, the object of analysis will be not so much the recondite technical means as the palpable expressive achievement.

The unfolding of this Andante con moto in A major conforms to no established format. Attempts to pigeonhole the movement according to the forms that were later codified in textbooks result in clumsy circumlocutions that betray their anachronism. The Scottish composer Donald Francis Tovey, one of the great music analysts of the early twentieth century, once found himself in precisely this quandary, reduced to describing the movement chiefly in terms of what it did not contain:

major conforms to no established format. Attempts to pigeonhole the movement according to the forms that were later codified in textbooks result in clumsy circumlocutions that betray their anachronism. The Scottish composer Donald Francis Tovey, one of the great music analysts of the early twentieth century, once found himself in precisely this quandary, reduced to describing the movement chiefly in terms of what it did not contain:

The form of the whole is roughly that of a first movement [i.e., a “sonata form”] with no repeats (I am not considering the small repeats of the two portions of the “binary” first theme), and with no development section, but with a full recapitulation and a final return to the first theme by way of coda.4

But no one ever listens to music like that. Any meaningful description of the movement will have to account for what it does contain, not what it doesn’t, beginning with a main theme (Ex. 11-1a) that, as Tovey observed, is presented as a fully elaborated, closed binary structure. This, of course, is something that never happens in a “first-movement” form, where the whole chain of events is inevitably set in motion by the interruption or elision of the theme’s final close. If we must pigeonhole, the category that is most likely to occur to us as a working hypothesis while listening is that of rondo. And there would be some corroboration for this conjecture later on, as we shall see, in the form of contrasting “episodes” (again reminiscent of those encountered in the slow movement of Haydn’s “Joke” Quartet, to which the present Andante is formally related). But it would still be better to take things as they come and regard the form of the piece as a result or outcome of a sequence of meaningful acts or “gestures,” some of them now and then recalling this or that familiar formal strategy.

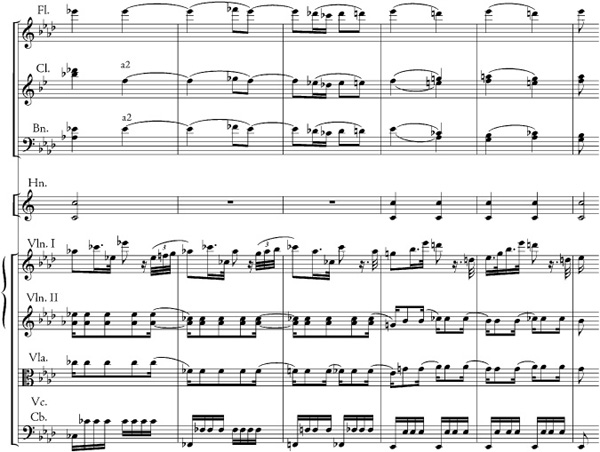

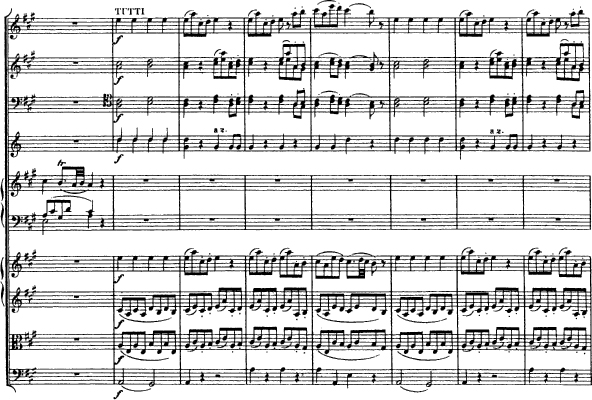

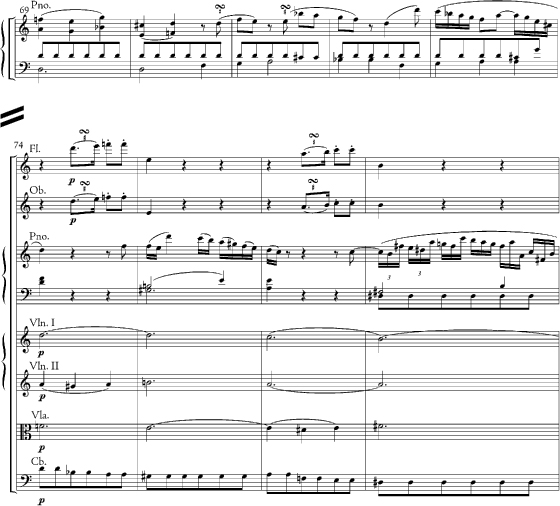

EX. 11-1A W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, opening

The two halves of the opening theme are related in a way that recalls “sonata form,” with the second half encompassing some motivic development, especially of the unaccompanied violin phrase first heard in mm. 2–3, and then a double return. That double return is tinged with irony, though, in the form of a modal mixture—the substitution of the parallel minor for the original tonic in mm. 22–25. The return is no return. You can’t go back again. Experience has cast a pall. The inflection of C to C , the tiniest inflection possible, makes a huge difference. Mozart was very fond of half-step adjustments that have outsized repercussions. Looking back at the first half of the theme, for example, we notice how he has managed to reroute the second cadence to the dominant just by inflecting the signature D

, the tiniest inflection possible, makes a huge difference. Mozart was very fond of half-step adjustments that have outsized repercussions. Looking back at the first half of the theme, for example, we notice how he has managed to reroute the second cadence to the dominant just by inflecting the signature D , as heard in m. 3, to D natural in m. 7.

, as heard in m. 3, to D natural in m. 7.

The inflection to C means a lot more. It bodes ill. As the music historian Leo Treitler memorably put it, the seemingly unmotivated modal mixture is “a signal of a coming complication, or perhaps it is better understood as a provocation—the injection without warning of an element, however small, that is uncongenial to the prevailing atmosphere and inevitably provokes trouble.”5 Indeed it will. And yet the theme’s final cadence puts the intruder out of mind as though nothing had happened. In psychological terms, the C

means a lot more. It bodes ill. As the music historian Leo Treitler memorably put it, the seemingly unmotivated modal mixture is “a signal of a coming complication, or perhaps it is better understood as a provocation—the injection without warning of an element, however small, that is uncongenial to the prevailing atmosphere and inevitably provokes trouble.”5 Indeed it will. And yet the theme’s final cadence puts the intruder out of mind as though nothing had happened. In psychological terms, the C and its troubling implications have been “repressed,” as one might repress a disagreeable passing thought. But as a result that cheery final cadence has an ironic tinge; it is covering something up. One has the uneasy feeling that “something” will be back.

and its troubling implications have been “repressed,” as one might repress a disagreeable passing thought. But as a result that cheery final cadence has an ironic tinge; it is covering something up. One has the uneasy feeling that “something” will be back.

And sure enough, a new intruder now bursts upon the scene: the wind instruments, silent up to now, enter on the dominant of F minor, the relative minor of the main key, and force the music into a new harmonic domain. The element of force is palpable, not only because of the peremptoriness of the winds’ maneuver, but because of the completely unexpected nature of the strings’ response: stormy, anguished, protesting (or, in “objective” musical terms, abruptly loud, syncopated, dissonant). Most significant of all, what finally forces the bass instruments off their tremolando F is the reappearance in m. 33, in a much more dissonant (diminished-seventh) context, of the repressed C , now a far more active ingredient, harmonically speaking, than it had been before (Ex. 11-1b). The repressed has returned; and, as always, it has returned in a more threatening guise. In m. 35 it actually takes over briefly as harmonic root (of a “German sixth” chord) before resolving, its force spent, to the dominant of V.

, now a far more active ingredient, harmonically speaking, than it had been before (Ex. 11-1b). The repressed has returned; and, as always, it has returned in a more threatening guise. In m. 35 it actually takes over briefly as harmonic root (of a “German sixth” chord) before resolving, its force spent, to the dominant of V.

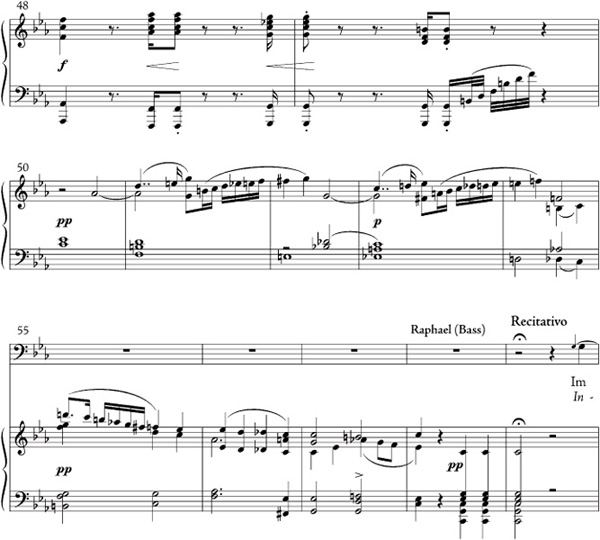

Again it has been repressed, but with much greater effort than before, and incompletely. In mm. 39–45 the winds and basses try to recover the poise of the motivic dialogue first heard in mm. 9–14, but the unremitting tremolo in the violins acts as a continuing irritant, and another anguished response bursts out at m. 46, leading to a recurrence of the repressed note in the bass (in its enharmonic variant, B natural) with gathering force (in m. 48 as a nonharmonic escape note, in m. 49 as the functional harmonic bass; see Ex. 11-1c). The first violins try to change the subject at m. 50, but they cannot shake the B natural; it keeps intruding in place of B (its trespass or forced entry underscored by its being sustained), and in m. 51 it is approached by a direct and highly disruptive leap of a tritone.

(its trespass or forced entry underscored by its being sustained), and in m. 51 it is approached by a direct and highly disruptive leap of a tritone.

EX. 11-1B W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, mm. 33–38

EX. 11-1C W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, mm. 48–53

Now, ironically, it is the winds, the original disturbers of the peace, who intervene to calm things down. The long passage from m. 53 to m. 68, leading to a serenely harmonious reprise of the original theme in the original key, is dominated by two points of imitation in the winds, of which the subject is drawn from the first wind entrance at m. 28; an effort to “undo the damage” is perhaps connoted by the inversion of the sixteenth-note turn figure (compare m. 54 et seq. with the flute in m. 29). The whole passage that follows (through m. 90) sounds like a “recapitulation” of the original theme, with the strings and winds now cooperating amicably in bright and brainy counterpoints (some of them, particularly the winds’ staccato scales in mm. 77–82, in a distinctly opera buffa spirit).

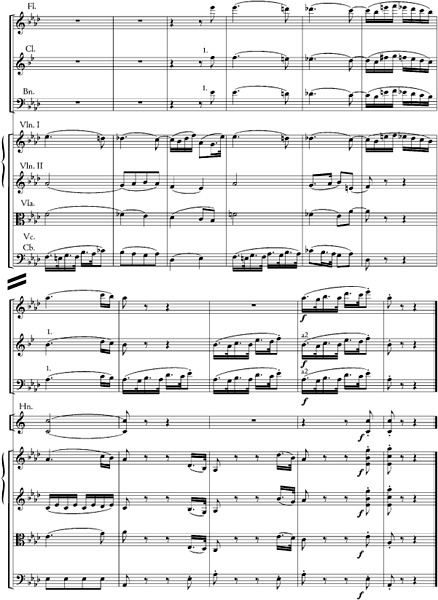

But in m. 91 (Ex. 11-1d) the repressed again returns with a vengeance, abetted by a portentous four-note chromatic segment in the winds that ushers in a passage of bizarre, almost bewildering commotion. It is the old storm-and-stress material first brought on by the winds in m. 28, only now transposed to B minor, a key so “far out” with respect to the original tonic as to have no normal functional relationship with it at all. Its relationship to the original “storm-and-stress” key, however, has been prefigured by that violin leap, already characterized as “disruptive,” from F to B in m. 51. And of course its tonic pitch is none other than the foreign body the movement has been trying to eject since its first appearance in m. 24. The repressed thought has not only returned, it has become an anguished, controlling obsession.

EX. 11-1D W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, mm. 91–97

Now it can be ejected only by really drastic measures. To recount them briefly: after a first fitful attempt to dislodge the B-natural by chromatic steps, it returns (spelled C ) and is resolved in mm. 103–4 by treating it as a dominant to F

) and is resolved in mm. 103–4 by treating it as a dominant to F (how many times could that note have functioned as a tonic in the eighteenth century?). In m. 105, the F

(how many times could that note have functioned as a tonic in the eighteenth century?). In m. 105, the F by picking up an augmented sixth (D natural in the winds), is identified as the flat submediant of A

by picking up an augmented sixth (D natural in the winds), is identified as the flat submediant of A , the home key, and is finally resolved to E

, the home key, and is finally resolved to E , the dominant, in m. 106 (see Ex. 11-1e).

, the dominant, in m. 106 (see Ex. 11-1e).

EX. 11-1E W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, mm. 103–108

Still the repressed note does not give up without a fight. After one last resurgence of conflict (mm. 116–19), the first violins try to bridge the last gap to the tonic, but are stalled briefly (mm. 121–24) by a couple of “difficult” intervals—a diminished fifth, and finally a diminished seventh that softly insinuates the C for the last time before the final subsidence into the tonic (Ex. 11-1f). When the main theme comes back for the last time (m. 144), its cadence is at last purged of modal mixture, as if to say “I’m cured.” Even so, at m. 151 and again at m. 155 there are a couple of lingering, curiously nostalgic twinges (Ex. 11-1g). The C

for the last time before the final subsidence into the tonic (Ex. 11-1f). When the main theme comes back for the last time (m. 144), its cadence is at last purged of modal mixture, as if to say “I’m cured.” Even so, at m. 151 and again at m. 155 there are a couple of lingering, curiously nostalgic twinges (Ex. 11-1g). The C comes back as a decorative bass note, always in conjunction (at first direct, then oblique) with D natural, with which it forms a “pre-dominant” diminished seventh, directing the harmony securely back to a tonic cadence that is repeated four times, the last time suddenly loud. This overly insistent close seems to protest a bit too much, as if to say “I’m OK! Really!”

comes back as a decorative bass note, always in conjunction (at first direct, then oblique) with D natural, with which it forms a “pre-dominant” diminished seventh, directing the harmony securely back to a tonic cadence that is repeated four times, the last time suddenly loud. This overly insistent close seems to protest a bit too much, as if to say “I’m OK! Really!”

The use of words like “repression” and “obsession” might seem carelessly anachronistic. They are (or, at least, can often be used as) psychoanalytical terms—terms that had their main currency in the twentieth century. Obviously, Mozart could not have known them, just as he could not have known the work of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), the main theorist of psychoanalysis, who was chiefly responsible for their vogue in twentieth-century parlance. But of course Freud knew Mozart, just as he knew the literary legacy of Romanticism, and repeatedly commented that his own contribution oftentimes amounted to no more than giving names and clinical interpretations to age-old psychological phenomena that poets (and, let us add, tone-poets) had long since portrayed artistically in their every detail.

EX. 11-1F W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, mm. 121–125

EX. 11-1G W. A. Mozart, Symphony no. 39 in E-flat, II, end

Not only twentieth-century listeners, but Mozart’s own contemporaries recognized that his instrumental music was unusually rich—unprecedentedly rich, they thought—in “inner portraiture.” It was Mozart above all who prompted Wilhelm Wackenroder (1773–98), an early theorist of Romanticism whose life was even shorter then Mozart’s, to formulate the very influential idea that “music reveals all the thousandfold transitional motions of our soul,” and that symphonies, in particular, “present dramas such as no playwright can make,” because they deal with the inner impulses that we can subjectively experience but that we cannot paraphrase in words.6

It was because of this perceived “new art” of subjective expression, as E. T. A. Hoffmann dubbed it, that symphonies, like all instrumental music, achieved an esthetic status far beyond anything they had formerly known, to the point where the instrumental medium could rival and even outstrip the vocal as an embodiment of human feeling. Hoffmann made the point quite explicitly and related it to the historical development traced in chapter 10. “In earlier days,” Hoffmann wrote,

one regarded symphonies merely as introductory pieces to any larger production whatsoever; the opera overtures themselves mostly consisted of several movements and were entitled “sinfonia.” Since then our great masters of instrumental music have bestowed upon the symphony a tendency such that nowadays it has become an autonomous whole and, at the same time, the highest type of instrumental music.

And specifically about Mozart’s E -major Symphony, K. 543, which contains the movement we have just examined in detail, Hoffmann wrote:

-major Symphony, K. 543, which contains the movement we have just examined in detail, Hoffmann wrote:

Mozart leads us into the heart of the spirit realm. Fear takes us in its grasp, but without torturing us, so that it is more an intimation of the infinite. Love and melancholy call to us with lovely spirit voices; night comes on with a bright purple luster, and with inexpressible longing we follow those figures which, waving us familiarly into their train, soar through the clouds in eternal dances of the spheres.7

It is tempting to speculate that the novel impression of enhanced subjectivity in Mozart’s instrumental music, and its vaunted autonomy (leading eventually to the idea, prized in the nineteenth century, of “absolute music” as the highest-aspiring of all the arts), had something to do with Mozart’s own novel, relatively uncertain and stressful social situation, and the heightened sense that it might have entailed of himself as an autonomous individual subjectively registering an emotional (or “spiritual”) reaction to the vicissitudes of his existence.

A number of critics have pointed to Mozart as the earliest composer in whose music one can recognize what one of them, Rose Rosengard Subotnik, has called the “critical world view” associated with modernity.8 Such a view entails a sense of reality that is no longer fully supported by social norms accepted as universal, but that must be personally constructed and defended. Its ultimate reference point is subjective: not the Enlightenment’s universal (and therefore impersonal) standard of reason, but the individual sentient self.

It is a less happy, less confident sense of reality than the one vouchsafed by unquestioned social convention, and it points the way to the “existential loneliness” or alienation associated with romanticism. Hoffmann himself, perhaps somewhat irreverently paraphrasing the words of Jesus, averred that the “kingdom” of art was “not of this world.”9 Artists who see themselves in this way are the ones most inclined to create “art for art’s sake,” as Mozart may have done in the case of his last three symphonies.

And yet, of course, it was a change in the social and economic structures mediating the production and dissemination of art—the conditions, in short, “of this world”—that gave artists such an idea of themselves. Mozart was the first great musician to have tried to make a career within these new market structures. We shall see their effects most clearly by turning now to the works he composed for himself to perform, particularly his concertos.

Despite Haydn’s unprecedented achievements in the realm of instrumental music, his catalogue contains a notable gap. His output of concertos is relatively insignificant. Only two or three dozen works of that kind are securely attributed to him, which may sound prolific enough until his hundred-plus symphonies and eighty-plus quartets are set beside them. Nor are they of a quality to stand comparison with those better-known works. Among them are a couple of perky little items that still figure occasionally on concert programs: a harpsichord concerto in D major and an unusual one in E for “clarino” (that is, trumpet played high), composed in London in 1796.

for “clarino” (that is, trumpet played high), composed in London in 1796.

His two cello concertos, especially the rather lengthy one in D major composed in 1783 for Anton Kraft, the solo cellist in Prince Esterházy’s orchestra (and once attributed to him), are played, some would suggest, more often than they deserve since today’s virtuoso cellists have hardly any “classical” concertos in their repertory. The D-major concerto originally won its place in the modern concert hall thanks to a modernized arrangement by the Belgian music scholar François-Auguste Gevaert; its only “classical” counterpart in the cello repertory, a concerto in B by Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805), was likewise popularized in an arrangement by the cellist Friedrich Grützmacher. It says a lot about Haydn’s concertos that they have needed editorial modernization in order to reenter the modern repertory, while his late symphonies, never modernized, have never gone out of style.

by Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805), was likewise popularized in an arrangement by the cellist Friedrich Grützmacher. It says a lot about Haydn’s concertos that they have needed editorial modernization in order to reenter the modern repertory, while his late symphonies, never modernized, have never gone out of style.

Few but students play Haydn’s four violin concertos any more, and a fair number of Haydn concertos are for instruments that nobody (well, hardly anybody) plays at all any more. Besides two concertos for Prince Nikolaus Esterházy’s beloved baryton, there are five for a pair of lire organizzate, weird hybrid instruments resembling hurdy-gurdies, activated by turning a crank but equipped on the inside with organ pipes and miniature bellows along with (or instead of) the usual violin strings. Haydn’s output for lira organizzata (including several “notturni” or serenades in addition to the concertos) were written quite late in his career, between 1786 and 1794, on commission from Ferdinand IV, King of Naples, an enthusiast of the improbable contraption.

FIG. 11-2 Lira organizzata, for which Haydn wrote a set of concertos (Bèdos de Celles, L’art du facteur d’orgues, 1778).

From this inventory of miscellaneous and rather perfunctory minor works a couple of important facts emerge. As the baryton and lira items suggest, Haydn’s concertos were written to order, as the sometimes unpredictable occasion arose, and had little or nothing to do with the composer’s personal predilections. Never once, moreover, did Haydn envision himself as the soloist in any of his concertos. He was not a virtuoso on any instrument, although he could function creditably as an ensemble violinist or a keyboard accompanist.

The situation with Mozart could not have been more different. His concertos were arguably the most vital and important portion of his instrumental output. Not only do they bulk larger in his catalogue, their total roughly equaling that of the symphonies, they also include some of his most original and influential work. As a result, Mozart’s standing as a concerto composer is comparable to Haydn’s in the realm of the symphony: he completely transformed the genre and provided the model on which all future concerto-writing depended. And that is largely because Mozart, as celebrated a performing virtuoso as he was a creative artist, was his own intended soloist—not only in his twenty-seven piano concertos but in his half-dozen violin concertos as well.

Mozart’s earliest concertos were written at the age of eleven (at Salzburg in the spring and summer of 1767), for use as display pieces in his early tours as a child prodigy. They are not entirely original works but arrangements for harpsichord and small orchestra (oboes, horns, and strings) of sonata movements by several established composers including C. P. E. Bach and Hermann Friedrich Raupach, whom the seven-year-old Mozart had met in Paris during a five-month stay in 1763–64, his first tour abroad. A few years later, when he was sixteen, Mozart made similar touring arrangements of three sonatas by J. C. Bach, whom he had got to know well in London in 1765. These were scored for a really minimal band (two violins and bass) for which Mozart composed ritornellos to alternate phrase-by-phrase with the originals. These pieces may not amount to much, but they did set the tone for Mozart’s lifetime output of concertos written for his own concert use.

Mozart’s first entirely original piano concerto (now known as “No. 5” and listed in the Köchel catalogue as K. 175) was written back home in Salzburg in December 1773, shortly before the composer’s eighteenth birthday. (He was still playing it in 1782, when he furnished it with a new finale for a concert in Vienna.) For the next two years, however, Mozart concentrated on the violin. His father, himself a famous violinist, encouraged him with the promise that if he applied himself, he could become the greatest violinist in Europe. As if to give himself an incentive to practice, Mozart composed five violin concertos between April and December 1775, as well as a curious piece he called “Concertone” (an invented word meaning “great big concerto”) for two violins and orchestra, which he composed, perhaps to perform with his father, in May 1774.

Mozart never did become the greatest violinist in Europe, but his brash and entertaining violin concertos of 1775, composed at the age of nineteen, were nevertheless a watershed in his career. In them he began to combine the older ritornello form inherited from the concerto grosso with the idiosyncratic, highly contrasted thematic “dramaturgy” of the contemporary symphony, itself heavily indebted for its verve and variety to the comic opera. Out of this eclectic mixture came the concerto style that Mozart made his trademark.

The Salzburg violin concertos are light and witty works in the serenade or divertimento mold. The third (in G, K. 216) and fourth (in D, K. 218) are virtually identical in form. They begin with bright allegros in an expanded ritornello form; their middle movements are lyrical “arias” (actually marked cantabile—“songfully”—in no. 4) in which the soloist takes the lead throughout; and their finales, titled “rondeau” in the French manner, are dancelike compositions in which the most variegated episodes alternate playfully with a refrain. In no. 3 the refrain is in a lilting  characteristic of the genre, but one of its episodes is a little march (preceded by an Andante in the minor). In no. 4 the recurrent tune itself alternates phrases in

characteristic of the genre, but one of its episodes is a little march (preceded by an Andante in the minor). In no. 4 the recurrent tune itself alternates phrases in  with phrases in

with phrases in  . This prankishly exaggerated heterogeneity—a Mozartean trademark!—lends these concluding movements something resembling the character of an opera buffa finale.

. This prankishly exaggerated heterogeneity—a Mozartean trademark!—lends these concluding movements something resembling the character of an opera buffa finale.

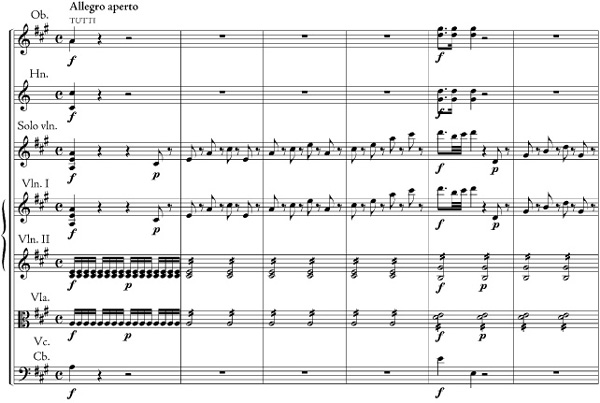

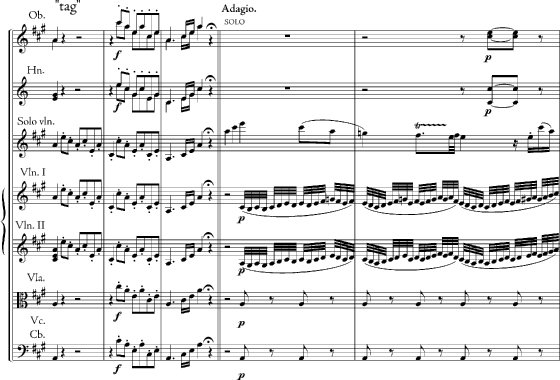

The fifth violin concerto (in A, K. 219) carries this comic opera effect to an extreme. Its finale, though not explicitly labeled “rondeau” since it has only one episode (resulting in the equally operatic da capo form), is an even wilder motley than its predecessors. The outer sections embody a gracious dancelike refrain in  time marked “Tempo di Menuetto,” while the middle of the piece consists of a riotous march or “quick-step” in the parallel minor, cast unexpectedly in the “alla turca” or “janissary” mode we have already encountered in The Abduction from the Seraglio, Mozart’s boisterous singspiel of 1782. (Osmin’s rage aria from that opera, we may recall, is also in A minor, as is the famous “Rondo alla turca” finale from the piano sonata, K. 331; it was Mozart’s “Turkish” key, and the fifth violin concerto is sometimes called the “Turkish” concerto.) The concerto’s first movement opens with a droll sendup of the Mannheim orchestra’s flashy routines, which Mozart had not yet actually heard on location, but which were avidly imitated, as we have seen, at the Parisian Concert Spirituel, which he did most enthusiastically attend as a boy. After a cheeky premier coup d’archet (“first stroke of the bow”) comes a pair of “Mannheim rockets”—lithe arpeggios in the violins that rise to little sonic outbursts in mm. 5 and 9 (Ex. 11-2a). Thereafter the mood of this opening tutti seems to change like the weather, in a manner again recalling descriptions of the Mannheim orchestra and the showpieces composed for it: pianissimos alternating with fortissimos, chromatic harmonies with primary chords, marchlike rhythms with syncopations, all leading to a concluding “tag” or fanfare on the tonic triad, arpeggiated all’unisono (Ex. 11-2b).

time marked “Tempo di Menuetto,” while the middle of the piece consists of a riotous march or “quick-step” in the parallel minor, cast unexpectedly in the “alla turca” or “janissary” mode we have already encountered in The Abduction from the Seraglio, Mozart’s boisterous singspiel of 1782. (Osmin’s rage aria from that opera, we may recall, is also in A minor, as is the famous “Rondo alla turca” finale from the piano sonata, K. 331; it was Mozart’s “Turkish” key, and the fifth violin concerto is sometimes called the “Turkish” concerto.) The concerto’s first movement opens with a droll sendup of the Mannheim orchestra’s flashy routines, which Mozart had not yet actually heard on location, but which were avidly imitated, as we have seen, at the Parisian Concert Spirituel, which he did most enthusiastically attend as a boy. After a cheeky premier coup d’archet (“first stroke of the bow”) comes a pair of “Mannheim rockets”—lithe arpeggios in the violins that rise to little sonic outbursts in mm. 5 and 9 (Ex. 11-2a). Thereafter the mood of this opening tutti seems to change like the weather, in a manner again recalling descriptions of the Mannheim orchestra and the showpieces composed for it: pianissimos alternating with fortissimos, chromatic harmonies with primary chords, marchlike rhythms with syncopations, all leading to a concluding “tag” or fanfare on the tonic triad, arpeggiated all’unisono (Ex. 11-2b).

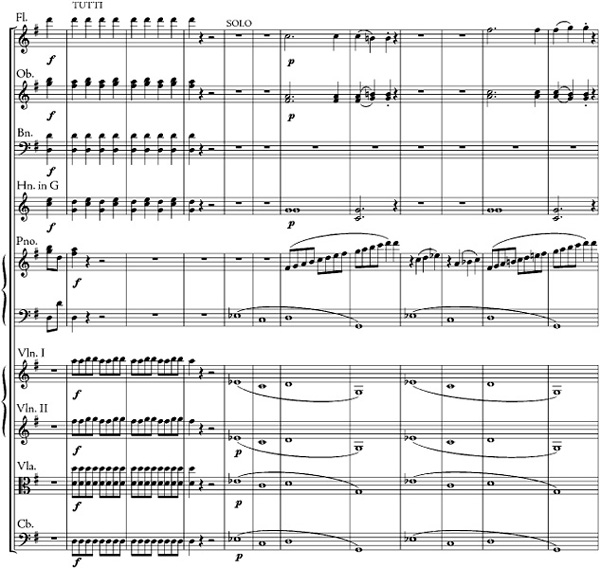

EX. 11-2A W. A. Mozart, Violin Concerto no. 5, K. 219, I, mm. 1–9

And now the soloist enters—with an altogether unexpected lyrical adagio that proceeds through a really purple harmonic patch (a deceptive cadence to an augmented-sixth chord) and reaches yet another full stop on the tonic. Only now does the movement really seem to get under way, and very wittily, with the violin playing the main theme over a repetition by the orchestra of its opening Mannheim flourishes, now revealed as a mere accompaniment to the real substance of the movement (hence the implied satire on what for the Mannheimers was the main event).

Thereafter the whole opening tutti passes in review—with the very telling exception that it is now expanded by means of solo interpolations, and with the quietest passage from the opening tutti now transposed to the dominant, thus taking on the characteristics of a “second theme” in a “sonata-form” or symphonic exposition. More solo passagework intervenes between this transposed passage and the next theme recalled from the opening tutti, thus giving the latter the character of a codetta closing off the exposition and leading—through an unexpectedly “far-out” V of iii—into what is obviously going to be a “development” section.

Of course there has already been a fair amount of thematic development in the exposition, chiefly involving the “tag,” which now comes twice—once in the tonic, to close off the “first theme,” and once in the dominant, to close off the “second.” The first time around (Ex. 11-2c), its final rising arpeggio is immediately appropriated by the soloist, who trades it off with the orchestral basses three times, after which it goes into the orchestral first and second violins to accompany the modulation to the dominant. This merry interplay actually performs a subtle structural role: by initiating the exchange, the first rising bass arpeggio is simultaneously an ending (of the “tag”) and a beginning (of the modulation). Its ambiguous status, in other words, provides the phrase elision or “elided cadence” traditionally invoked to cover the structural joint where theme gives way to “bridge” or transition.

EX. 11-2B W. A. Mozart, Violin Concerto no. 5, K. 219, I, mm. 37–41

EX. 11-2C W. A. Mozart, Violin Concerto no. 5, K. 219, I, mm. 61–73

Here, in embryo, we have the so-called “double exposition” technique through which the concerto form was modernized in the age of the symphony. The first compositions in which the technique can be identified are found in a set of six keyboard concertos by J. C. Bach, published in London as his opus 1 in 1763. These, possibly along with the unpublished but widely circulated concertos of C. P. E. Bach, may be regarded as Mozart’s models. But although pioneered by the Bach brothers, the technique was used so consistently (and more to the point, varied so imaginatively) by Mozart, and became through him so influential, that since the end of the eighteenth century it has been thought of as the foundation of the “Mozartean” concerto style.

According to Heinrich Christoph Koch, the most encyclopedic music theorist and critic of the late eighteenth century, if one considers “Mozart’s masterpieces in this category of art works, one has an exact description of the characteristics of a good concerto.”10 And according to Carl Czerny, a pupil of Beethoven, who wrote the most influential music textbooks of the early nineteenth century, the form of the solo concerto had been expressly established by Mozart as a vehicle for representing the same kind of intense subjective feeling we have already observed in his symphonies.11 This simplified account of the concerto’s genealogy is obviously colored by the mythology that grows up around any great creative figure, but (as in any myth) its departures from the literal truth give insight into cultural values. Like all the other genres of the late eighteenth century, the concerto was formally transformed in order to serve new social purposes and meet new expressive demands.

In the first movement of a modernized (or “symphonicized,” or “Mozartean”) concerto, the opening orchestral ritornello and the first solo episode contain the same thematic material, but with three significant differences the second time around. First, and most obviously, the themes are redistributed between the soloist and the band. Second, they are often augmented by passages and, occasionally, by whole themes newly contributed by the soloist, and thereafter reserved for the solo part. Third, and most important by far, the second statement (and only the second one) will make the intensifying modulation to the dominant without which there can be no properly symphonic form.

These modifications amount, in effect, to a way of “dynamizing” the statically sectional ritornello form in which concertos were formerly cast by adding to it the closed (“there and back”) tonal trajectory of the symphonic binary form. It is true that even in a Vivaldi concerto the first ritornello stays in the tonic and the first solo moves out to the dominant (in the major). But the two sections in the earlier concerto did not share thematic material. It is the deployment of a similar melodic content toward crucially divergent ends that so dramatizes the symphonic concerto. By adding an element of overarching tonal drama to the form, Mozart’s concertos serve further to dramatize the relationship between the soloist and the accompanying (or, as the case may be, dominating) group.

The technique was not christened “double-exposition” until the end of the nineteenth century. (The actual term was coined by Ebenezer Prout, a prolific British writer of conservatory textbooks, in 1895.)12 But as early as 1793, only two years after Mozart’s death, Koch described the contemporary concerto in terms of its relationship to the symphony, and so it is by no means anachronistic to view it so today. Indeed, there is no other way to account for the dynamic, dramatic, and expressive resources now employed by the composers (who were often also the performers) of concertos. They all had their origin in the symphony; but it could be argued that they reached their peak of development somewhat earlier, in Mozart’s concertos.

The works in which that peak was scaled were the piano concertos Mozart wrote for himself to perform during his last decade, when he was living in Vienna and trying to support himself—like increasing numbers of musicians at a time of radical transition in the economy of European music-making—as a freelance artist. The conditions that had so favored Haydn’s development and nurtured his gifts were drying up. Julia Moore, the outstanding economic historian of musical Vienna, has summarized the catastrophic institutional and commercial changes that were taking place, to which Mozart, like countless lesser contemporaries, had to adapt as best he could. Until the middle of the 1770s, she records, court musical establishments or Kapellen were maintained not only by emperors and kings but also by princes, counts, and men without important titles. But between 1780 and 1795, most of the Kapellen in the Habsburg Empire were disbanded, except those at a few important courts, causing widespread unemployment among musicians and a huge surge in freelance activities.

Haydn himself experienced this change in 1790, when his chief patron died and he was put out to pasture. But he had already made his fortune, enjoyed a pension, and was soon visited in any case by a crowning stroke of good fortune when Salomon brought him to London as a celebrity freelancer and guaranteed his earnings. After his return to Vienna, he was a world luminary and was showered with “windfall patronage,” aristocrats and wealthy merchants vying with one another to secure his prestigious and lavishly remunerated presence in their homes for an evening. At his death, Haydn left a net estate of over ten thousand florins, literally hundreds of times the median estate of a composer in late eighteenth-century Vienna, placing him solidly in the ranks of the upper middle class, otherwise populated by industrialists.

Mozart had traveled the length and breadth of Europe during the late 1770s in fruitless search of a Kapelle to direct. Once in Vienna, far from a world celebrity (except insofar as he was remembered from his childhood as a sort of freak), he had to rely on windfall patronage alone for his livelihood, which put him at the mercy of a notoriously fickle public.13 His appearances as virtuoso at “academies” (concerts he put on himself, for which he sold subscriptions) and aristocratic soirées were his primary source of income, and his vehicles at these occasions were his piano concertos. And so during his Vienna years he composed on average about two a year, from the Concerto in F major (K. 413), now known as no. 11, composed in the winter of 1782–83, to the Concerto in B major (K. 595), now known as no. 27, completed on 5 January 1791, shortly before his last birthday. These seventeen concertos, created over a period of less than nine years, were arguably Mozart’s most important and characteristic instrumental compositions.

major (K. 595), now known as no. 27, completed on 5 January 1791, shortly before his last birthday. These seventeen concertos, created over a period of less than nine years, were arguably Mozart’s most important and characteristic instrumental compositions.

Yet they were not evenly spread out over the time in question. In fact, a chronology of Mozart’s concertos turns into an index of his fortunes in the musical marketplace. At first, as a novel presence in Vienna, he was very fashionable and sought-after. Between 1782 and 1786 he was allowed to rent the court theater every year for a gala concert; he gave frequent well-attended subscription academies; and he received frequent invitations to perform at aristocratic salons. He lived high during this period, in a luxury apartment, and had many “status” possessions including a horse and carriage.

At the pinnacle of his early success he proudly sent his father a list of his concert engagements during the Lenten season of 1784. Lent, when theaters were closed by law, was always the busiest time of year for concerts, and Mozart had twenty-one engagements over the five weeks between late February and early April. Most were aristocratic soirées, including five appearances at the residence of Prince Dmitriy Mikhailovich Galitzin (or Golitsyn), the Russian ambassador, and no fewer then nine (twice a week, on Mondays and Fridays) at the home of Count Johann (or János Nepomuk) Esterházy, a member of a lesser branch of the family that so famously patronized Haydn. Three were subscription concerts at the Trattnerhof Theater, and one, on the first of April, was an especially lucrative engagement at the court theater, where ticket prices could be set very high, and where Mozart could expect to net upwards of fifteen hundred florins.

All of these occasions undoubtedly included concerto performances, and so it is no wonder that Mozart completed no fewer than six concertos during the golden year of 1784, with three following in 1785 and another three in 1786. As Moore notes, however, the fact that Mozart never again secured the use of a court theater “indicates that he had become overexposed to the Viennese musical public by 1787.”14 His fortunes declined precipitously. By 1789 he could no longer subscribe academies to the point where they were profitable. “I circulated a subscription list for fourteen days,” he complained in a letter to a friend, “and the only name on it is Swieten!”15 He had to move to a smaller apartment, lost his status possessions, and, as all the world knows, went heavily into debt, so that at the time of his death his widow inherited liabilities totaling over a thousand florins (offset somewhat by the value of his clothing, a remnant from the fat years). The same ruinous decline is also reflected in his concerto output, with only two completed between the end of the year 1786 and his death five years later.

While it is no more realistic an endeavor to select a single “representative” Mozart concerto than it would be to select a single representative Haydn symphony, a combination of factors suggests the Concerto in G, K. 453, now known as no. 17, as a plausible candidate for the role. It was completed on 12 April 1784, immediately after the fabulous Lenten season described above, during Mozart’s most productive concerto year. It was ostensibly written not for Mozart himself to perform but for Barbara Ployer, a Salzburg pianist who had been his pupil, and who was the daughter of a wealthy Salzburg official, who commissioned it; and so it has an unusually complete and painstaking score. Probably for the same reason it is not one of Mozart’s most difficult concertos to perform; but as we shall see, the notated score of a Mozart concerto is by no means a reliable guide to its realization in performance. When Mozart himself played it, which he did often beginning in 1785, he surely embellished the rather modest solo part.

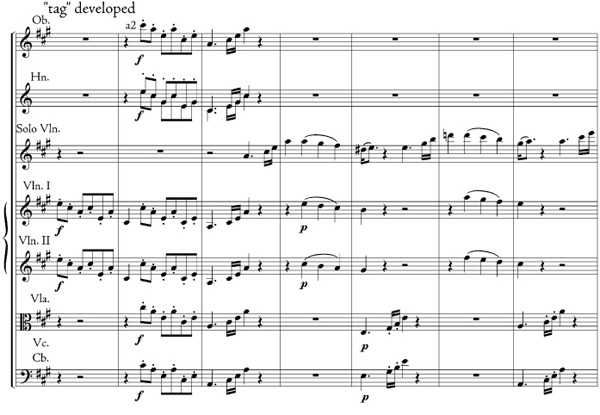

Like practically all solo concertos, still reflecting the century-old Vivaldian legacy, the work is cast in three movements, of which the first is in the “symphonicized” or “sonatafied” ritornello form described above. The two “expositions” are related according to a plan that was by 1784 habitual with Mozart. Comparing them from the moment of the piano’s first solo entry, which takes the form of a little Eingang or “intro” preceding the first theme, it appears that the soloist takes over all the early thematic material the second time around—or rather, the piano replaces the strings in dialogue with the wind instruments. When the crucial modulation to the dominant finally takes place, the piano gets to announce the new key with an unaccompanied solo that contains a theme that was not part of the opening ritornello. It will remain the pianist’s property to the end. The second theme from the opening orchestral ritornello, characteristically Mozartean in its operatic lyricism, eventually arrives in the dominant, with the pianist again replacing the strings in dialogue with the winds. The orchestral tutti that follows (and confirms) the piano’s cadential trill at the end of the second exposition corresponds in function to the second ritornello in older concertos.

The moment corresponding to the final cadence of the ritornello is replaced by a “deceptive” move to a B major harmony that in the local context sounds like the flat submediant. (In terms of the once and future tonic, it is of course the mediant of the parallel minor.) This chromatic intrusion launches a long modulatory section that reaches a surprising FOP on the diatonic mediant (B natural) with a borrowed major third, turning it into the “V of vi.” A passage like this fulfills the structural function of a development section, finally enabling a satisfying resolution of tension in a “double return,” with the tension stretched out just a mite by a typical feint in the solo part: an Eingang (m. 224) that leads not to the by now urgently expected first theme in the tonic, but to a teasingly reiterated dominant seventh.

major harmony that in the local context sounds like the flat submediant. (In terms of the once and future tonic, it is of course the mediant of the parallel minor.) This chromatic intrusion launches a long modulatory section that reaches a surprising FOP on the diatonic mediant (B natural) with a borrowed major third, turning it into the “V of vi.” A passage like this fulfills the structural function of a development section, finally enabling a satisfying resolution of tension in a “double return,” with the tension stretched out just a mite by a typical feint in the solo part: an Eingang (m. 224) that leads not to the by now urgently expected first theme in the tonic, but to a teasingly reiterated dominant seventh.

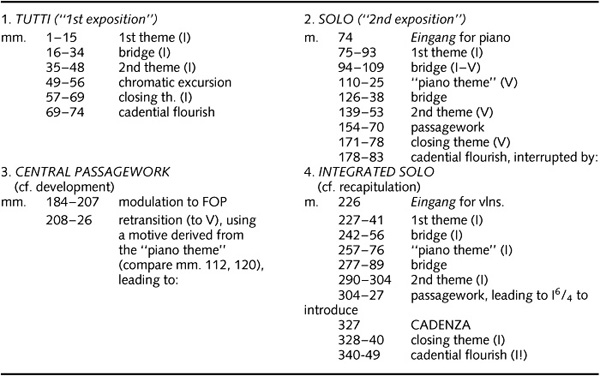

A sneaky little extra Eingang for the violins finally reintroduces the first theme, and we get a slightly truncated “compromise” or integrated version of the exposition, which might be likened to a sonata recapitulation in that it stays in the tonic, but which actually owes a greater historical debt to the older precedent of the da capo aria. This final major section of the movement has all the thematic material from the modulating exposition, including the pianist’s unaccompanied theme, and culminates in the solo cadenza. All of these details are summarized in Table 11-1.

The cadenza, another direct inheritance from the da capo aria, was literally an embellishment of the soloist’s final cadence, or trill, preceding the last ritornello. At the hands of successive generations of virtuosi it kept on growing until Koch (writing in 1793) had forgotten the etymological link that defined the cadenza’s initially rather modest cadential function. Calling the traditional term a misnomer, he defined the cadenza instead as being in reality “either a free fantasy or a capriccio”—that is, a fairly lengthy piece-within-a-piece to be improvised by the soloist on the spot.16 According to the terms by which Koch designated it, the cadenza in his day was a piece in which the usual forms and rules of composition were in abeyance (as suggested by capriccio, “caprice”) and in which the soloist could concentrate entirely on pursuing an untrammeled train of idiosyncratic musical thought (fantasia, “vagary”), as we may remember from the empfindsamer Stil compositions of C. P. E. Bach, the genre’s pioneer (see Ex. 8-4).

TABLE 11-1 Mozart, Concerto no. 17 in G, K. 453, Movement I (Allegro)

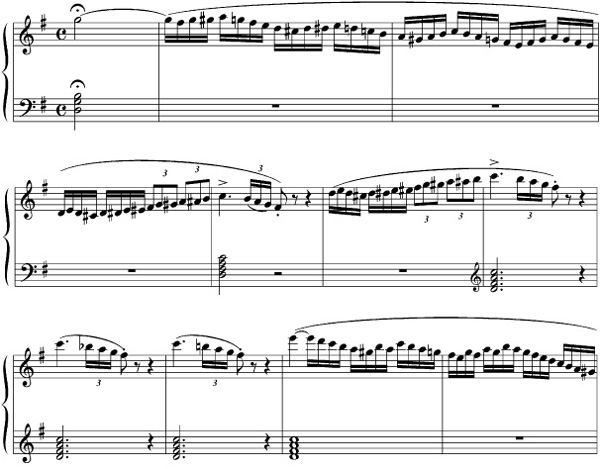

It is hard to tell just what these descriptions had to do with what Mozart himself might have played at the point marked “cadenza” in his concerto scores, since like all true virtuosos in his day he was an expert improviser, and played impromptu with the same mastery as when playing prepared compositions. Nor were the two styles completely separate. When playing a previously composed piece from memory, Mozart (as many earwitnesses report) felt completely free to reembroider or even recompose it on the spot. Only when he composed his concertos for others to perform (as in Concerto no. 17) did he even write out the solo part in full. Most of the existing manuscripts contain sections of sketchy writing that served as a blueprint for impromptu realization. (Nowadays such passages are all too often rendered literally by pianists who have been trained to play only what is written.) When playing a newly finished concerto for the first time, Mozart usually “improvised” the whole piano part from blank staves or a bass line (playing it, that is, half spontaneously, half from memory). For an idea of what he could do, compare the autograph of the opening of the second movement from his “Coronation” Concerto, K. 537, with the first published edition, issued three years after Mozart’s death with a piano part supplied by an unidentified arranger (Fig. 11-3a, b).

FIG. 11-3A Autograph page from Mozart, Concerto no. 26 in D, K. 537.

Nor was any public concert or salon complete without an “ex tempore” performance, often on themes submitted by the audience to make sure that what was billed as improvisation was truly that. Mozart was famous for his ability to improvise not only free fantasias or capriccios on such submitted themes but even sonatas and fugues. “Indeed,” wrote an awestruck member of one of the largest audiences Mozart ever played to (in Prague, on 19 January 1787),

we did not know what to admire the more—the extraordinary composition, or the extraordinary playing; both together made a total impression on our souls that could only be compared to sweet enchantment! But at the end of the concert, when Mozart extemporized alone for more than half an hour at the fortepiano, raising our delight to the highest degree, our enchantment dissolved into loud, overwhelming applause. And indeed, this extemporization exceeded anything normally understood by fortepiano playing, as the highest excellence in the art of composition was combined with the most perfect accomplishment in execution.17

From accounts like this, we may conclude that for Mozart, at any rate, the acts or professions of composing and performing were not nearly as separate as they have since become in the sphere of “classical” music. They are more reminiscent of the relationship that the two phases of musical creation have in the realms of jazz and pop music today. And so is the brisk interaction Mozart enjoyed with his audiences. The spontaneity of the Prague audience’s reaction, as described in the extract above, applied not only to solo recitals, or concerto performances, but even to the performances of symphonies. After the first performance of his Symphony in D Major, K. 297 (now known as Symphony no. 31), one of his most orchestrally brilliant scores, which took place in Paris before the most sophisticated paying public in Europe in June of 1778, Mozart wrote home exultantly:

FIG. 11-3B The same passage from Mozart, Concerto no. 26 in D, K. 5, that was shown in Fig. 11-3A, as posthumously edited and printed

Just in the middle of the first Allegro there was a Passage I was sure would please. All the listeners went into raptures over it—applauded heartily. But as, when I wrote it, I was quite aware of its Effect, I introduced it once more towards the end—and it was applauded all over again…. I had heard that final Allegros, here, must begin in the same way as the first ones, all the instruments playing together, mostly in unison. I began mine with nothing but the 1st and 2nd violins playing softly for 8 bars—then there is a sudden forte. Consequently, the listeners (just as I had anticipated) all went “Sh!” in the soft passage—then came the sudden forte—and no sooner did they hear the forte than they all clapped their hands.18

Such behavior would be inconceivable today at any concert where Mozart’s music is played. And yet in Mozart’s day it was considered normal, as this very letter reveals. Mozart expected the audience’s spontaneous response and predicted it—or rather, knowing that it would be the sign of his success, he angled for it. Now only pop performers do that. Such reactions and such angling are now déclassé (debased, regarded as uncouth) in the “classical” concert hall. The story of how that change came about is one of the most important stories in the history of nineteenth-century music, but Mozart had no part of that.

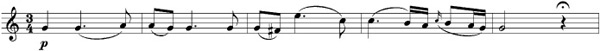

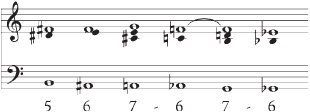

When writing music out for others to perform, Mozart did occasionally provide cadenzas in advance to make the recipients look good, especially his sister Maria Anna (“Nannerl”), known in Salzburg as an excellent pianist in her own right, but not a composer. For the Concerto in G major, K. 453, composed for Barbara Ployer but also sent to Nannerl, he wrote out two different cadenzas for the first movement, and, rather unusually, for the second one as well—but that second movement is a rather unusual movement, as we shall see. The beginnings of the two first-movement cadenzas are set out for inspection in Ex. 11-3.

Like these, Mozart’s written-out cadenzas usually took the form of short fantasias based more or less consistently on themes from the exposition. In the present case the first cadenza to the opening movement exemplifies the “thematic” style (“more consistently based”), the second the “passagework” style (“less consistently based”). In the latest and biggest concertos the thematic style predominates, often broken down into motivic work that begins to resemble “development.” But whether these written cadenzas truly resemble anything Mozart would himself have played is difficult to guess. It seems unlikely that the pianist known among his fellow pianists as the greatest improviser of his time would have hewn so closely to the thematic content of the composed sections of the piece, or stayed so closely within the orbit of the original tonic. All the less likely does it seem if one considers Mozart’s predilection for infusing his instrumental works with “personality”—creating, as we have already seen, the impression of spontaneous subjective expression. This histrionic posture could only have been heightened when he was taking an active part in the performance.

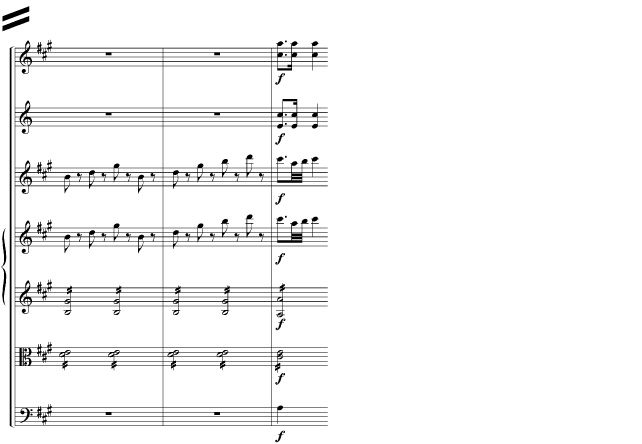

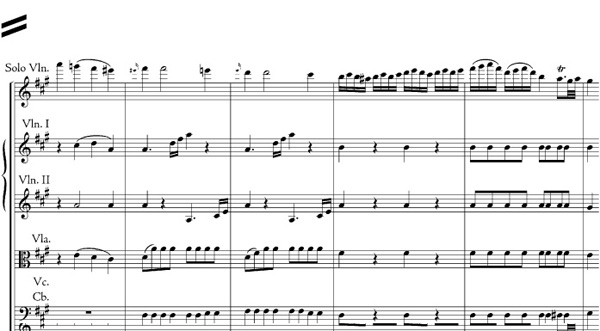

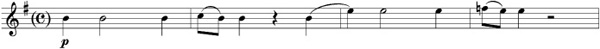

So let us imagine Mozart, not Barbara Ployer, as the soloist in the slow middle movement of the Concerto in G major, K. 453. The form of the piece is unusual on two counts. First, because it has a true symphonic binary shape, rarely found in a slow movement; and second, because that shape is complemented by a striking “motto” or ritornello idea.

The piece may be broken down into four large sections, each of them introduced by a strangely off-center phrase consisting of a single five-bar idea—or half idea, since it ends inconclusively, with a half cadence. The odd phrase length is achieved by drawing out a conventional four-bar phrase with a cadential embellishment that dramatizes its nonfinality, and then really insisting on its suspenseful nature with a rest that is further enhanced by a fermata. The phrase is almost literally a question—to which the ensuing music provides a provisional answer. In contour it strikingly resembles the beginning of the lyrical second theme from the first movement (see Ex. 11-4), and can probably be regarded as a conscious derivation from it (since anything that is likely to occur to us so readily is likely to have occurred just as readily to the composer).

EX. 11-3 W. A. Mozart, Concerto in G major, K. 453, I: beginnings of two different cadenzas

EX. 11-3 Beginning of second candenza

EX. 11-4A W. A. Mozart, Concerto in G major, K. 453, II, mm. 1–5

EX. 11-4B W. A. Mozart, Concerto in G major, K. 453, I, mm. 35–38

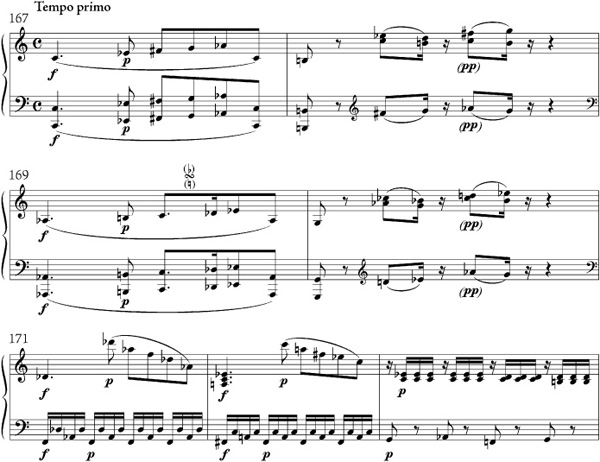

The four sections this motto phrase so suspensefully introduces could be described as corresponding, respectively, to an opening ritornello (or nonmodulating exposition), an opening solo (or modulating exposition), a development section, and a recapitulation. The coda, or closing segment following the cadenza, begins with what sounds like another repetition of the motto; but it differs very tellingly from the others, as we shall see.

Precisely because it does not come to a full stop but demands continuation, the prefatory motto lends the material that follows it a heightened air of expressive moment. That sense of poetic gravity is more than corroborated by the emotionally demonstrative behavior of the solo part. Once past the preliminaries, the first solo starts right off with an impetuous turn to the parallel minor (Ex. 11-5a)—always a sign of emotional combustion—reinforced by a sudden loudening of the volume and a thickening of the piano texture beyond anything heard in the first movement. The modulation to the dominant is accompanied by some very purple harmonies—Neapolitan sixth, diminished seventh—of a kind also largely avoided (or rather, unwanted) in the sunny first movement.

EX. 11-5A W. A. Mozart, Concerto no. 17 in G major, K. 453, II, mm. 35–41

The temperature has cooled and the skies have lightened by the time the final cadence on the dominant is made and the next incantation of the motto begins. But as soon as the soloist returns (Ex. 11-5b), the mood becomes restless again. Another sudden shift to the parallel minor (this time on D, the root of the half cadence in the dominant) is followed by a fairly gruesome passage in which the harmony is violently forced backward along the circle of fifths through successive cadences on A minor, E minor, B minor, and even F minor—all the way to C

minor—all the way to C minor, the tritone antipode of G, the concerto’s nominal tonic. These cadence points are all introduced by disruptive applied dominants, and the last of them is followed by an augmented sixth (A-natural vs. F-double-sharp) that sets up a half cadence on its dominant, the almost unheard-of FOP of G

minor, the tritone antipode of G, the concerto’s nominal tonic. These cadence points are all introduced by disruptive applied dominants, and the last of them is followed by an augmented sixth (A-natural vs. F-double-sharp) that sets up a half cadence on its dominant, the almost unheard-of FOP of G major.

major.

EX. 11-5B W. A. Mozart, Concerto no. 17 in G major, K. 453, II, mm. 69–86

What follows now is a tour de force of harmonic legerdemain. In a mere four bars, as if solving a chess problem in four moves, the orchestra moves in (mm. 86–89) and leads the G major harmony through its parallel minor (altering one note), to a dominant seventh on E (achieved by splitting the D

major harmony through its parallel minor (altering one note), to a dominant seventh on E (achieved by splitting the D , so speak, into E and D, again altering a single note), thence to a dominant seventh on G (inflecting the G

, so speak, into E and D, again altering a single note), thence to a dominant seventh on G (inflecting the G to G and the E to F), the whole thus functioning as an incredibly rapid yet smooth retransition to the original tonic, C major (Ex. 11-5c). Its arrival, signaled by the motto phrase, provides an appropriately dramatic “double return.” From this point to the end the accent is on progressive reconciliation and accommodation. The pianist gets one more outburst to parallel the one in m. 35; but although it still invokes a darkling minor coloration, it is the tonic minor that is invoked, and the cloud is that much more easily dispelled. Although, presumably, Mozart at the keyboard might have let loose a few more harmonic vagaries during the cadenza, the cadence thus embellished prepares the ultimate reconciliation of harmonic conflicts. Mutual adjustment and cooperation is beautifully symbolized by the final orchestral statement of the motto phrase (mm. 123 ff), which this time lacks its embellished half cadence and suspenseful fermata, but rather hooks up with a balancing phrase in the solo part to bring things back, peacefully and on harmonic schedule, to the tonic. Just as in the slow movement from Symphony no. 39 (Ex. 11-1), there are a few chromatic twinges in the closing bars to recall old aches, but the end comes quietly, with gracious resignation.

to G and the E to F), the whole thus functioning as an incredibly rapid yet smooth retransition to the original tonic, C major (Ex. 11-5c). Its arrival, signaled by the motto phrase, provides an appropriately dramatic “double return.” From this point to the end the accent is on progressive reconciliation and accommodation. The pianist gets one more outburst to parallel the one in m. 35; but although it still invokes a darkling minor coloration, it is the tonic minor that is invoked, and the cloud is that much more easily dispelled. Although, presumably, Mozart at the keyboard might have let loose a few more harmonic vagaries during the cadenza, the cadence thus embellished prepares the ultimate reconciliation of harmonic conflicts. Mutual adjustment and cooperation is beautifully symbolized by the final orchestral statement of the motto phrase (mm. 123 ff), which this time lacks its embellished half cadence and suspenseful fermata, but rather hooks up with a balancing phrase in the solo part to bring things back, peacefully and on harmonic schedule, to the tonic. Just as in the slow movement from Symphony no. 39 (Ex. 11-1), there are a few chromatic twinges in the closing bars to recall old aches, but the end comes quietly, with gracious resignation.

EX. 11-5C W. A. Mozart, Concerto no. 17 in G major, K. 453, II, mm. 86–94

Again, as in the symphony, we have a kind of emotional diary in sound, but this time there is the complicating factor of the dual medium: piano plus (or, possibly, versus) orchestra. The heightened caprice and dynamism that Mozart (and before him, C. P. E. Bach) brought to the concerto genre caused a heightened awareness of its potentially symbolic or metaphorical aspect, its possible reading as a social paradigm or a venue for social commentary. Artists imbued with the individualistic spirit of Romanticism interpreted the paradigm as one of social opposition, of the One against the Many, with an outcome that could be either triumphant (if the One emerged victorious) or tragic (if the decision went the other way).

The interaction of the soloist and the orchestra in the slow movement of Concerto No. 17 has been splendid grist for such readings, including a vivid one by the feminist musicologist Susan McClary (whose social interpretation of Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg Concerto was discussed in chapter 6). She reads the piece as a narrative of increasingly fraught contention between the orchestra and the defiant soloist, with that egregious FOP on a G major triad signaling an impasse. “From the point of view of tonal norms,” she writes (having already characterized tonal norms as a metaphor for social norms), “the piano has retreated to a position of the most extreme irrationality, and normal tonal logic cannot really be marshaled to salvage it.”19 And yet the orchestra, as we have already seen, succeeds in salvaging the tonic in a mere four bars. Such a quick victory, McClary argues, is itself “irrational,” defiant of “the pure pristine logic of conventional tonality.” Both the soloist and the orchestra have exhibited startling, not to say deviant, behavior—and deviance requires explanation. The explanation one chooses will reveal one’s social attitudes. Does it seem that “the collective suddenly enters and saves the day”? If so, then one has confessed one’s allegiance to the communal order. (McClary identifies this as the “Enlightened” position.) Or, conversely, does it seem that the “necessities of the individual are blatantly sacrificed to the overpowering requirements of social convention”?20 This would betray one’s identification with “the social protagonist,” and cast the orchestra’s behavior as exemplifying “the authoritarian force that social convention will draw upon if confronted by recalcitrant nonconformity.”

major triad signaling an impasse. “From the point of view of tonal norms,” she writes (having already characterized tonal norms as a metaphor for social norms), “the piano has retreated to a position of the most extreme irrationality, and normal tonal logic cannot really be marshaled to salvage it.”19 And yet the orchestra, as we have already seen, succeeds in salvaging the tonic in a mere four bars. Such a quick victory, McClary argues, is itself “irrational,” defiant of “the pure pristine logic of conventional tonality.” Both the soloist and the orchestra have exhibited startling, not to say deviant, behavior—and deviance requires explanation. The explanation one chooses will reveal one’s social attitudes. Does it seem that “the collective suddenly enters and saves the day”? If so, then one has confessed one’s allegiance to the communal order. (McClary identifies this as the “Enlightened” position.) Or, conversely, does it seem that the “necessities of the individual are blatantly sacrificed to the overpowering requirements of social convention”?20 This would betray one’s identification with “the social protagonist,” and cast the orchestra’s behavior as exemplifying “the authoritarian force that social convention will draw upon if confronted by recalcitrant nonconformity.”

In such a reading, a painful irony colors the final repetition of the opening motto, in which, we recall, the piano and the orchestra finally cooperate in a way that “delivers the long-awaited consequent phrase” that answers the motto’s persistent question. The appearance of concord, McClary suggests, masks oppression and social alienation.

It is not difficult to raise objections to this reading, if one insists that a reading of a work of art directly represent or realize the author’s intentions, and that those intentions are “immanent”—that is, inherent—in the work itself. One can cite biographical counterevidence: in 1784, the year in which Mozart composed this concerto, he was at the very peak of his early Viennese prosperity and showed few signs of alienation from the public whose favor he was then so successfully courting. (A possible rejoinder: we know, nevertheless, that the success was short-lived; and while Mozart could not know that, he did know very well that his freelance activity was risky and that his affluent lifestyle was precarious. This consciousness might well indeed have colored his attitude toward the society in which he was functioning, and made him anxious or mistrustful.) One may also doubt whether either the piano’s tonal behavior or the orchestra’s can really be classified as “irrational” within the listening conventions Mozart shared with his audience. Every symphonic composition reached a FOP, sometimes a very distant one (though, admittedly, rarely so distant as here). Mozart’s techniques for achieving it in the present instance, while extreme in their result, were fully intelligible in their method. Quick chromatic or enharmonic returns to the tonic from distant points are something we have observed long ago in Scarlatti, after all, for whom it was sooner an amusing gesture than a troubling one.

Then too, the quick resolution of a seemingly hopeless imbroglio was the hallmark of the comic opera in which Mozart so excelled, and which (as we have seen) so informed the style of his concerto writing. Another music historian, Wye J. Allanbrook, calls the device the “comic closure,” and maintains that the quicker and smoother the unexpected reconciliation, and the greater the harmonic distance covered by it, the more it reflected Mozart’s essentially optimistic outlook on the workings of his society.21 In this, Allanbrook concludes, Mozart was acting in a manner typical of eighteenth-century dramatists and, like them, expressing an ingenuous commitment to the social ideals of the Enlightenment.

FIG. 11-4 A Mozart family portrait, ca. 1780, by Johann Nepomuk della Croce. W. A. Mozart and his sister Maria Anna (“Nannerl”) are at the keyboard; their father Leopold holds a violin; the portrait on the wall shows the composer’s mother, who had died in 1778 in Paris while accompanying him on tour (Mozart House, Salzburg).

Indeed, the interpretive descriptions of the concerto that have come down to us from the eighteenth century tend to place emphasis on a kind of co-participation in an expressive enterprise, rather than on social conflict. “I imagine the concerto,” wrote Koch, “to be somewhat like the tragedy of the ancients, where the actor expressed his feelings not to the audience but to the chorus, which was involved most sparingly in the action, and at the same time was entitled to participate in the expression of the feelings.”22 Thus, in Koch’s view, there is indeed an “emotive relationship” between the soloist and the orchestra. “To it,” Koch writes (meaning the orchestra), “he displays his feelings, while it now beckons approval to him with short interspersed phrases, now affirms, as it were, his expression; now it tries in the Allegro to stir up his exalted feelings still more; now it pities him in the Adagio, now it consoles him.” As Jane R. Stevens, the translator of this passage from Koch, comments, “instead of antagonists or simply cooperating partners, the solo and tutti are semi-independent, interacting elements in a sort of dramatic intercourse”—one designed not merely to represent a mode of interaction but to achieve a heightened expressive intensity for the audience to contemplate.23

And yet, even if it can be demonstrated conclusively that the idea of concerto as social paradigm was not the dominant view of Mozart’s time, that does not by any means preclude or invalidate social or biographical readings of his contributions to the genre. The view of the concerto as a critical social microcosm seems to have come later than Mozart’s time, but not much later. And when it came, it had surely been influenced by Mozart’s example. Koch himself is a case in point. His remarks on the expressive meaning of the concerto are from his textbook, An Essay in Composition Instruction (Versuch einer Anleitung zur Composition), published in 1793. In this book, C.P. E. Bach is named as the exemplary concerto composer; Mozart’s name is absent. Nine years later, in 1802, Koch published a Musical Dictionary, in which many of the same points are made, but now with Mozart as the prime example.

It was, in other words, only after Mozart’s death that his concertos began to circulate outside of the narrow Vienna-Salzburg corridor and have a wider resonance. By then, Romanticism was burgeoning. The meanings and feelings that were drawn out of Mozart’s music by his later interpreters probably no longer corresponded exactly with those that Mozart was aware of depositing there, so to speak. But a message received is just as much a message as a message sent. In this as in so many ways, Mozart—perhaps unwittingly, but no less powerfully—fostered the growth of musical Romanticism, and became its posthumous standard-bearer.

Whatever we may make of the closing bars of the middle movement, the finale of the Concerto in G, K. 453, like practically all of Mozart’s concerto finales, is cast in the cheerful, conciliatory spirit of an opera buffa finale. While the rondo form remained the most popular framework for such pieces, a significant minority of concertos, including this one, used the theme and variation technique. In either case, the object was the same: to put a fetchingly contrasted cast of characters on stage and finally submerge their differences in conviviality. Mozart’s stock of variational characters is replete, on the happy end, with jig rhythms for the piano and gossipy contrapuntal conversation for the winds; and, on the gloomy end, with mysterious syncopations in the parallel minor, all awaiting reconciliation in the coda.