The year 1685 is luminous in the history of European music, because it witnessed the birth of three of the composers whose works long formed the bedrock of the standard performing repertoire, or “canon,” as it crystallized (retrospectively) in the nineteenth century. In fact, the three composers in question—Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), George Frideric Handel (1685–1759), and Domenico Scarlatti (1685–1757)—were for a long while the three earliest composers in active repertory, and so the number 1685 took on the aspect of a barrier, separating the music of common listening experience from a semiprehistoric repertoire called “early music” (or “pre-Bach music” as it was once actually termed), of concern only to specialists.

The contents, indeed the very existence, of this book show that this barrier has softened considerably, perhaps (some might argue) to the point of nonexistence. Concert life has been enriched by many performing artists and ensembles who confine themselves to music earlier than that of the class of 1685. Excellent recordings of such music abound. It is widely studied, analyzed, and critiqued. It has become familiar to a degree that would have been unthinkable even half a century ago. And yet artists who perform this music still specialize in it, and one aspect of the popularization of “pre-Bach” music has been an effort to reclaim the class of 1685 as specialist repertoire, which paradoxically means separating it from the “standard performing canon as crystallized in the nineteenth century” and placing it in the “pre-Bach” category.

Now we are apt to find Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti performed on the resurrected instruments of their time, not the standard instruments of today, by performers who have made a specialized study of the conventions that governed the performance practices of the early eighteenth century, and who are keen to emphasize the differences between those conventions and those to which “modern” listeners have become accustomed. The newfound familiarity of “early music” has led paradoxically to an effort to “defamiliarize” (or even “re-defamiliarize”) it. This is something that happened in the twentieth century, and so the reasons for it are best studied as part of the history of twentieth-century music.

The formation (or “canonization”) of the old performing repertory was something that happened in the nineteenth century, and so, it follows, the reasons for it are best studied as part of the history of nineteenth-century music. (The revival of Bach, whose music had temporarily fallen out of use except as teaching material, is an important and revealing part of that story.) And yet there were good reasons—“objective” reasons, one could argue—why the music of the class of 1685 became the foundation stone of the standard repertory once it was formed, and why even today their music (plus a few later rediscoveries like Vivaldi’s Four Seasons) remains the earliest music that nonspecialist performers and “mainstream” performing organizations like choral societies and symphony orchestras routinely include in their active repertoires.

Theirs is also the earliest music that today’s concertgoers and record listeners are normally expected to “understand” without special instruction, partly because general music pedagogy is still largely based on their work. No child learns to play the violin without encountering Vivaldi, or the piano without encountering Bach and (if one gets serious) Scarlatti. As soon as one is old enough to participate in community singing, moreover, one is sure to meet Handel.

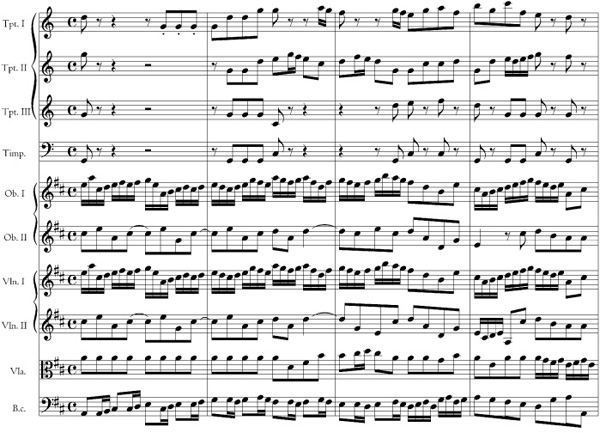

The main reasons for this were broached in the previous chapter. These composers were the earliest to inherit from the Italian string players of the seventeenth century, and then magnificently enlarge upon, a fully developed “tonal” idiom. From the same Italian virtuosi they also inherited a standardized and highly developed instrumental medium—the “ripieno” string band or orchestra, to which wind and percussion instruments could be added as the occasion demanded. The new harmonic idiom and the new instrumental media acted symbiotically to foster the growth of standard instrumental and vocal-instrumental forms of unprecedented amplitude and complexity, and these were the forms on which the later standard repertory rested.

It follows, then, that the works of the class of 1685 that loom largest in the standard repertory will be those that coincide with, or that can be adapted to, standard performing media and esthetic purposes. Those of their works that are apt to be familiar today will therefore represent only a portion of their outputs, and not necessarily those portions considered most important or most characteristic by the composers themselves or by their contemporaries. Opera seria, the reigning genre of their day, has long dropped out of the repertoire. Therefore much of the music that both Handel and Scarlatti regarded as the most important music of their careers has perished from active use, while a lot of music that they regarded as quite secondary (Scarlatti’s keyboard music, Handel’s suites for orchestra) is standard fare today. Bach, who never even wrote an opera, was an altogether atypical and marginal figure in his day. Seeing him, as we do, as being a pillar of the standard performing repertory means seeing him in a way that his contemporaries would never have understood.

Thus to see Bach, Handel, and Scarlatti as standard repertory composers is to see them in a historical context that is not theirs. It will be our job to view them in their own historical context as well as in ours. The most fascinating historical questions about their work will be precisely those that concern the relationship between the two contexts. The most surprising aspect of the comparison will be the realization that Bach and Handel, whom we regard from our contemporary vantage point as a beginning, were regarded more as enders in their own day: outstanding late practitioners of styles and genres that were rapidly growing moribund in their time.

It was their very “conservativism,” paradoxically enough, that later made them “canonical.” The styles that supplanted theirs were destined to be ephemeral. Meanwhile, Handel’s conservative idiom chanced to appeal to conservative members of his contemporary audience—and as we shall see, these members constituted the particular social group that inaugurated the very idea of “standard” or “timeless” repertory. It was logical that Handel’s music should have been the earliest beneficiary of that concept.

With Bach the situation was more complicated. He came back into circulation, and achieved a posthumous status he never enjoyed in life, because the conservative aspects of his style—in particular, his very dense contrapuntal textures and his technique of “spinning out” melodic phrases of extraordinary length—made his music seem weighty and profound at a time when the qualities of weightiness and profundity were returning to fashion (and, as we shall see, served political and nationalistic purposes as well).

A mythology grew up around Bach, according to which his music had a unique quality that lifted it above and beyond the historical flux and made it a timeless standard: the greatest music ever written and (ideologically far more significant) the greatest music that would or could ever be written. That myth of perfection begot in its turn a myth of music history itself. It was given an elegant and memorable expression by the great German musicologist Manfred Bukofzer (1910–55). “Bach lived at a time when the declining curve of polyphony and the ascending curve of harmony intersected, where vertical and horizontal forces were in exact equilibrium,” Bukofzer wrote, adding that “this interpenetration of opposed forces has been realized only once in the history of music and Bach is the protagonist of this unique and propitious moment.”1

There was indeed a unique moment of which Bach was the protagonist. It took place, however, not during Bach’s lifetime but in the nineteenth century, when the concept of impersonally declining and ascending historical “curves” was born. It was a concept born precisely out of the need to justify Bach’s elevation to the legendary status he had come to enjoy as the protagonist of an unrepeatable, mythical golden age and the fountainhead of the Germanic musical “mainstream.” The “equilibrium” and “interpenetration” of which Bukofzer wrote, and to which he assigned such a high value, were qualities and values created not by Bach but by those who had elevated him. The history of any art, to emphasize it once again, is the concern—and the creation—of its receivers, not its producers.

Bach and Handel were born within a month of one another, about a hundred miles apart, in adjoining eastern German provinces (then independent princely or electoral states). Handel, whose baptismal name was Georg Friederich Händel, was born on 23 February, in Halle, one of the chief cities in the so-called March of Brandenburg (a “march” being a territory ruled by a Margrave). Bach came into the world on 21 March a little to the south and west, in the town of Eisenach in Thuringia, a province of Saxony. Because of their nearly coinciding origins and their commanding historical stature, Bach and Handel are often thought of as a pair. In most ways, however, their lives and careers were a study in contrasts.

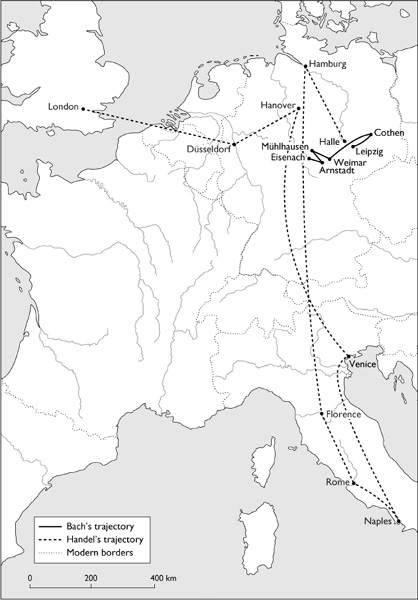

FIG. 6-1 J. S. Bach’s and G. F. Handel’s career trajectories.

Handel spentonlythefirsteighteenyearsofhislifeinhisnativecity, wherehestudied with the local church organist, Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, and attended the university. In 1703 he moved to Hamburg, the largest free city in northern Germany, which had a thriving opera house maintained by the municipal government and supported by the local merchants. There he played harpsichord (continuo) in the orchestra and composed two operas for the company. Having found his métier in the musical theater, Handel naturally gravitated to Italy, the operatic capital of the world. He spent his true formative years—from 1706 to 1710—in Florence and Rome, where he worked for noble and ecclesiastical patrons and met and played with Alessandro Scarlatti, Corelli, and other luminaries of the day, and where he was known affectionately as il Sassone, “the Saxon,” meaning really “the Saxon turned Italian” in the musical sense. In 1710 he became the music director at the court of George Louis, the Elector of Hanover, one of the richest German rulers. There, Handel had to assimilate the French style that all the German nobles affected in every aspect of court life, including court music.

The great turning point in Handel’s life came in 1714, when his employer, without giving up the Electoral throne in Hanover, was elected King George I of England. (Queen Anne had died without a living heir and George Louis, as the great-grandson of King James I, was the closest Protestant blood claimant to the English throne.) George I never learned to speak English and was personally unpopular in England. He continued to spend much or most of his time in Hanover, leaving the running of the English government largely to his ministers of state, chief among them Robert Walpole, the powerful Prime Minister.

Handel had actually made his English debut as an opera composer before George’s accession to the throne. With the King a virtual absentee ruler, his court composer was left remarkably free of official duties, and gained the right to act as a free agent, an independent operatic entrepreneur on the lively London stage. Over the rough quarter century between 1711 and 1738, Handel presented thirty-six operas at the King’s Theatre in the London Haymarket (with a few, toward the end, at Covent Garden, which is still called the Royal Opera House), averaging four operas every three years. Acting at once as composer, conductor, producer, and, eventually, his own impresario, he made a legendary fortune, the first such fortune earned by musical enterprise alone in the history of the art. (Palestrina also died a very rich man, but his fortune came from his wife’s first husband’s fur business.)

Beginning in the 1730s, operatic tastes in London began to catch up with the continent. A rival company, the Opera of the Nobility, managed to engage the latest Italian composers and (far more important) the services of the castrato singer Farinelli (see chapter 4), around whom a virtual cult had formed. After a few seasons of cutthroat competition, both Handel and his competitors were near bankruptcy, and Handel was forced out of the opera business. With his practically incredible business sense he divined a huge potential market in English oratorios: Biblical operas presented without staging, along lines already familiar to us from the Lenten work of Roman composers such as Carissimi.

Handel’s adaptation of this old-fashioned genre was really something quite new: full-length works in the vernacular rather than Latin, without a narrator’s part, but with many thrilling choruses, sometimes participating in the action, sometimes reflecting on it (“Greek chorus” style) to represent as a collective entity the pious yet feisty nation of Israel, with which the musical public in England—a public of “self-made men,” aristocrats of wealth and opportunity, not birth, exulting in England’s mercantile supremacy—strongly identified.

FIG. 6-2 J. S. Bach (?) at age thirty. Oil portrait by Johann Ernst Rentsch (ca. 1715), at the Municipal Museum of Erfurt.

Though ostensibly religious in their subject matter, the subtext of Handel’s English oratorios—twenty-three in all, produced between 1732 and 1752—was stoutly nationalistic. It was the first important body of musical works motivated by nationalism—a nationalism in which the composer, a naturalized British subject who had benefited greatly from his adopted country’s economic prosperity and the opportunities it offered, enthusiastically shared—just as England, since the “revolutions” of the mid and late seventeenth century, was the first country larger than a city state to identify itself as a nation in the modern sense of the word: a collectivity of citizens.

Handel’s was thus the exemplary cosmopolitan career of the early eighteenth century, a career epitomized by his operatic “middle period,” in which a German-born composer made a fortune by purveying Italian-texted operas to an English-speaking audience. Handel’s style was neither German nor Italian nor English, but a hybrid that blended all existing national genres and idioms, definitely including the French as well. France was the one country where Handel, though an occasional visitor, never lived or worked; but its music, an international court music, informed not only the specifically courtly music that he wrote for his kingly patron but the overtures to his oratorios as well, which paid tribute to the “Heavenly King.” Handel was the quintessential musical polyglot and the consummate musical entrepreneur. He commanded “world” (that is, pan-European) prestige. He has been a role model to “free market” composers ever since.

FIG. 6-3 A bird’s-eye view of Leipzig in 1712. St. Thomas Church, where Bach would find employment eleven years later, stands by the south wall at right. The churches of St. Paul and St. Nicolai, where he also supervised musical performances, are at the other end of town.

FIG. 6-4 St. Thomas Square, Leipzig, in an engraving by Johann Gottfried Krügner made in 1723, the year of Bach’s arrival. The church is at right; the school, where Bach lived and worked, is at left.

Johann Sebastian Bach never once left Germany. Indeed, except for his student years at Lüneburg, a town near Hamburg to the north and west, his entire career could be circumscribed by a small circle that encompassed a few east German locales, most of them quite provincial: Eisenach, his Thuringian birthplace; Arnstadt, where he served between 1703 and 1707 as organist at the municipal Church of St. Boniface; Mühlhausen, where he served at the municipal Church of St. Blasius for a single year; Weimar, where he served the ducal court as organist and concert director from 1708 to 1717; Cöthen, a town near Halle, Handel’s birthplace, where he served as Kapellmeister or music director to another ducal court from 1717 to 1723; and finally Leipzig, the largest Saxon city (but not the capital), where he served as cantor or music director at the municipal school attached to the St. Thomas Church from 1723 until his death.

FIG. 6-5 Interior of St. Thomas Church, with a view of the organ loft.

One of the larger German commercial cities even in Bach’s day, Leipzig was nevertheless only a fraction of London’s size and far from a cosmopolitan center. Still, it was a big enough town to have sought a bigger name than Bach as its municipal cantor. He was chosen only after two more famous musicians, Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767) and Christoph Graupner (1683–1760), had declined the town’s offer in favor of more lucrative posts (in Hamburg and Darmstadt, respectively). One of the Leipzig municipal councillors grumbled that since the best men could not be had, they would have to make do with a mediocrity. Bach, for his part, felt he had been forced to take a step down the social ladder by going from a Kapellmeister’s position at Cöthen to a cantorate at Leipzig. Until age put him out of the running, he repeatedly sought better employment elsewhere, including the electoral court at Dresden, the Saxon capital. Leipzig was the best he could do, however, and Bach was the best that Leipzig could do. Neither was very happy with the other.

Bach’s, then, was the quintessential “provincial” career—humble, unglamorous, workaday. He remained for life in the musical environment to which he had been born, and which Handel quitted at his earliest opportunity. Handel had an unprecedented, self-made, entrepreneurial career that brought him glory and a very modern kind of personal fulfillment. Bach’s, by contrast, was entirely predefined: it was the most traditional of careers for a musician of his habitat and class. For a musician of exceptional talent it was downright confining.

It was as “predefined” as that because J. S. Bach happened to come from an enormous clan or dynasty of Lutheran church musicians dating back to the sixteenth century. So long and firmly associated was the family with the profession they plied that in parts of eastern Germany the word “Bach” (which normally means “brook” in German) was slang for musician. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians lists no fewer than eighty-five musical Bachs, from Veit Bach (ca. 1555–1619), a baker from Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia) who enjoyed a local reputation for proficiency on the cittern (a plectrum-plucked stringed instrument related to the lute and the mandolin), down ten generations to Johann Philipp Bach (1752–1846), court organist to the Duke of Meiningen.

Fourteen members of the family were distinguished enough as composers to earn biographical articles in the dictionary. They include two of Johann Sebastian Bach’s uncles (Johann Christoph and Johann Michael), three of his cousins (Johann Bernhard, Johann Nicolaus, and Johann Ludwig), four of his sons (Wilhelm Friedemann, Carl Philipp Emanuel, Johann Christoph Friedrich, and Johann Christian), and his grandson Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst (1759–1845, son of Johann Christoph Friedrich), who died childless and extinguished his grandfather’s line.

The outward shape of Johann Sebastian Bach’s career did not differ from those of his ancestors and contemporaries, and was far less distinguished than those of his most successful sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel and especially Johann Christian, whom we have already met briefly as a globe-trotting composer of opera seria. Most of the elder Bachs were trained as church organists and cantors. That training included a great deal of traditional theory and composition, and as church musicians the elder Bachs were expected to turn out vocal settings in quantity to satisfy the weekly needs of the congregations they served.

The greatest composers of this type in the generations immediately preceding Bach—or at least the ones Bach sought out personally and took as role models—were three: Georg Böhm (1661–1733), whom Bach got to know during his student years at Lüneburg and whose fugues he particularly emulated; the Dutch-born Johann Adam Reincken (1643–1722), a patriarchal figure who had studied with a pupil of Sweelinck, and who died in his eightieth year; and, above all, Dietrich (or Diderik) Buxtehude (1637–1707), a Dane who served for nearly forty years as organist of the Marienkirche in the port city of Lübeck, one of the most important musical posts in Lutheran Germany.

Within that cultural sphere Buxtehude’s fame was supreme, and he received numerous visits and dedications from aspiring musicians, including both Handel (who came up from Hamburg in 1703) and Bach (who took a leave from Arnstadt to make a pilgrimage on foot to Buxtehude in the fall and winter of 1705–1706). According to a story related by one of his pupils in a famous obituary, the aged Reincken, having heard Bach improvise on a chorale as part of a job audition, proclaimed the younger man the torchbearer of the old north-German tradition: “I thought this art was dead,” the patriarch is said to have exclaimed, “but I see that in you it lives!” The story may well be apocryphal, but it contains an important truth: Bach did found his style on the most traditional aspects of north German (Lutheran) musical culture—a culture that was by most contemporary standards an almost antiquated one—and brought it to a late and (in the eyes of some of his contemporaries) virtually anachronistic peak of development. The keyboard works he composed early in his career while serving as organist at Arnstadt and Weimar show this retrospective side of Bach most dramatically.

FIG. 6-6 Johann Adam Reincken, engraving after a portrait by Gottfried Kneller.

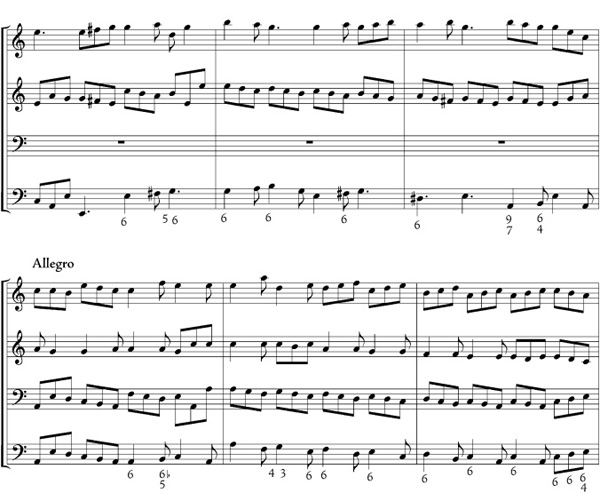

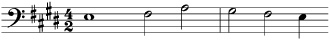

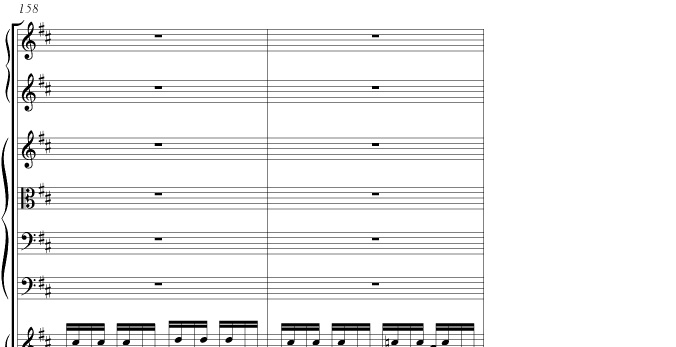

One such apprentice piece, a harpsichord sonata in A minor, was based on a sonata da camera by Reincken himself, originally published in 1687 when Bach was two. Reincken had scored the piece for a trio sonata ensemble of two violins and continuo, enriched by a viola da gamba part that sometimes doubled the basso continuo line, sometimes embellished it, and sometimes departed from it to add a fourth real part to the texture. This kind of saturated texture was very much a German predilection and harks back to the full polyphony of the stile antico. Another Germanic trait was the sheer length of Reincken’s fugal subjects, a length achieved by the use of very long measures ( meter being the most note-heavy meter in general use) and through devices of Fortspinnung or “spinning out” such as we have already associated in the previous chapter with Bach.

meter being the most note-heavy meter in general use) and through devices of Fortspinnung or “spinning out” such as we have already associated in the previous chapter with Bach.

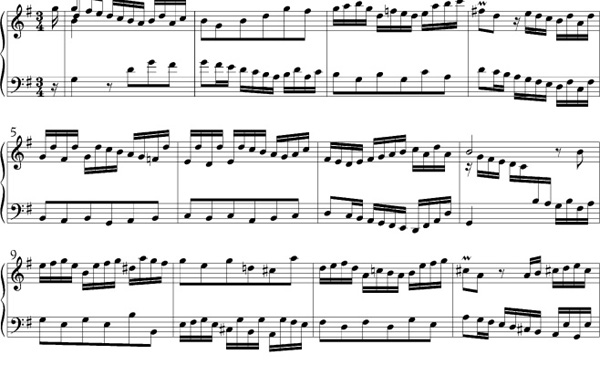

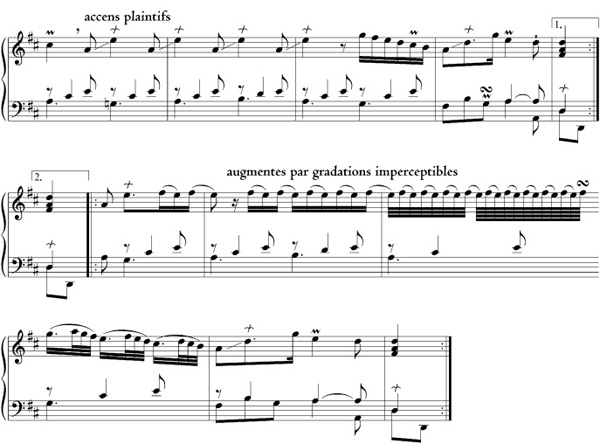

In Ex. 6-1, the first section of Reincken’s last movement, a gigue in typical fugal style, is juxtaposed with Bach’s reworking. It is a true emulation: not just an imitation, not just an homage, but an effort to surpass. One way in which Bach sought to accomplish this was by a sheer increase in size—in two dimensions. Reincken’s nineteen measures are swollen to thirty, and his three-voiced exposition is augmented by a fourth fugal entry in Bach’s version. At a time when many composers—especially composers of opera—were pruning and simplifying their styles in the interests of directness of expression, Bach remained faithful to an older esthetic tradition, seeking instead a maximum of formal extension and textural complexity. Throughout his life he was famed for the density of his music—sometimes praised for it, sometimes mocked.

At the same time, Bach managed, by varying the texture and pacing the harmony, to give his fugal exposition a much shapelier, more sharply focused design than Reincken’s, despite the increase in length and (so to speak) in girth. At the beginning, Bach allows the initial exchange of subject and answer to take place without accompaniment, dispensing with Reincken’s bass line as if getting rid of clutter. Then he gives greater point to the cadence at the end of the subject (m. 3) by spinning the sequence down as far as the leading tone, where Reincken had marked the end by repeating the approach to the tonic pitch.

This sharpening of tonal focus could be thought of as a modernizing touch: a response to the newly focused tonal style that was emanating from Italy, and that had quickly established itself, for musicians of Bach’s generation, as a norm. Indeed, Bach greatly intensifies the harmony both in color and in “functionality,” accompanying Reincken’s long sequences of three-note descents with explicit circle-of-fifths harmonizations that sometimes (as in the full-textured “fourth entrance” in mm. 11–13) go into a sort of chromatic overdrive thanks to the use of secondary or “applied” dominants. For the rest, Bach expands the length of the exposition by devising an “episode” motive consisting of a decorated suspension chain (first heard in m. 7 between the two subject/answer pairs) that is finally brought rather dramatically into contrapuntal alignment with the subject on its last appearance.

Both Reincken’s and Bach’s versions are followed a couple of measures into the second section before Ex. 6-1 breaks off, to show the way in which both composers, following an old tradition, invert the subject to complement its initial statement. Here, too, Bach managed to outdo Reincken by building the inverted exposition from the bottom up instead of repeating the original top-down order of entries, thus achieving inversion, as it were, on two compositional levels at once.

Devices like these, and competition in their ingenious application, were standard operating procedure for church organists, who learned to do such things extemporaneously. More than anything else, they hark back to the learned artifices and contrivances of the stile antico. Bach delighted in these erudite maneuvers that he learned in his prentice years, employed them in every genre, and in his last years brought them to a peak of virtuosity that has been regarded ever since as unsurpassable. His son Carl Philipp Emanuel recalled that when listening to an organist improvise, or even when hearing a composed fugue for the first time, his father would always try to predict all the devices that could be applied to the subject, taking special pleasure in being surprised by one that he had failed to predict, and, contrariwise, reproaching the player or composer if his expectations went unmet.

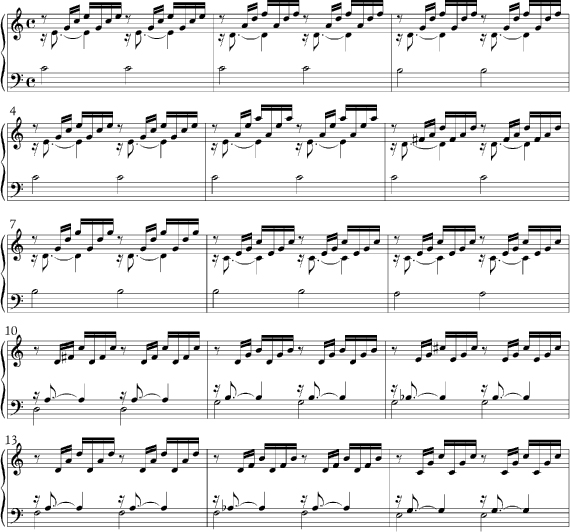

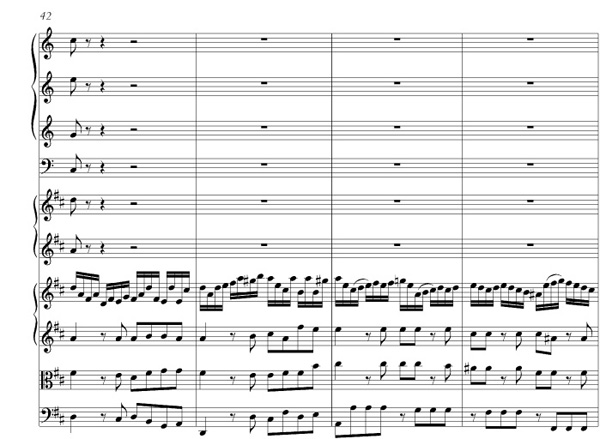

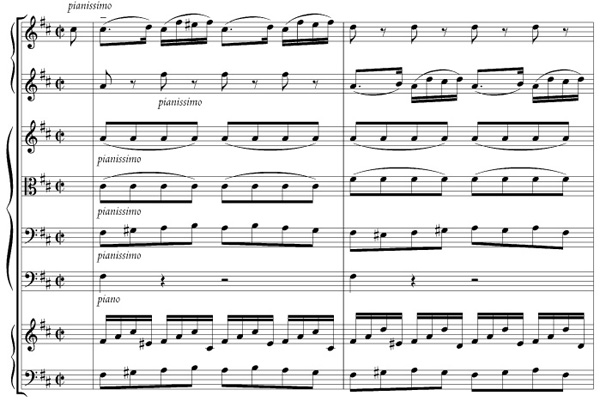

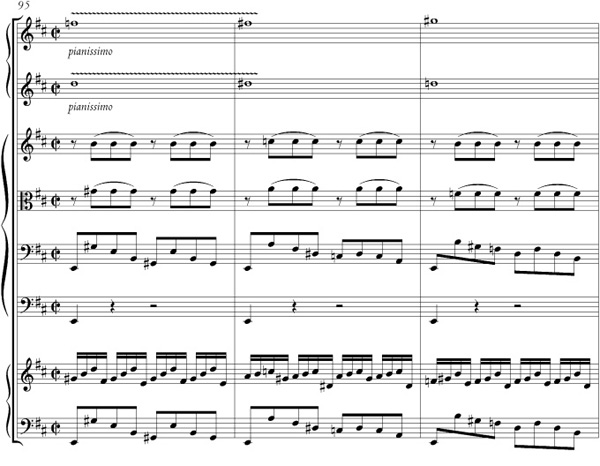

EX. 6-1A J. A. Reincken, Hortus musicus, Sonatano. 1, Gigue, mm. 1–21

EX. 6-1B J. S. Bach, the same, arranged as a keyboard sonata, mm. 1–34

From Buxtehude, Bach inherited the toccata form sampled in the previous chapter. The Toccata in F included there as Ex. 5-15 may have originally been paired with a fugue (in F minor), according to a process that Buxtehude had pioneered, whereby the “strict” and “free” sections of a toccata—that is, the rigorously imitative or “bound” vs. the improvisatory passages—became increasingly separate from one another and increasingly regular in their alternation, with the improvisatory passages serving as introductions to the increasingly lengthy fugal ones.

By the early eighteenth century these sectionalized toccatas had developed into pairs of discrete pieces, the free one prefacing (or serving as “prelude” to) the strict. Such a pair, although still called “Toccata” or “Toccata and fugue” when the “free” part was especially lengthy or virtuosic (as in Ex. 5-15), or “Fantasia and fugue” when the free part had strongly imitative or motif-developing tendencies, was by Bach’s time most often simply designated “Prelude and fugue.”

Bach was the latest and greatest exponent of the prelude-and-fugue form, to which he contributed more than two dozen examples for organ, along with works in even more traditional genres, like his famous organ Passacaglia in C minor. Most of these are early works, the bulk of them composed at Weimar, where he was employed primarily as an organ virtuoso. One of Bach’s most famous and mature compositions, however, was a monumental cycle of forty-eight paired preludes and fugues called Das wohltemperirte Clavier, in two books, the first composed in Cöthen in 1722, the second in Leipzig between 1738 and 1742.

Das wohltemperirte Clavier means “The Well-Tempered Keyboard.” Its subtitle reads “Praeludia und Fugen durch alle Tone und Semitonia,” or “Preludes and Fugues through all the Tones and Semitones.” This meant that each of the books making up Bach’s famous “Forty-Eight” consisted of a prelude-and-fugue pair in all the keys of the newly elaborated complete tonal system, alternating major and minor and ascending by semitones from C major, the “purest” of the keys since it has an accidental-free signature, to B minor (thus: C, c, C , c

, c , D, d, and so on). Only a keyboard tuned in something approaching “equal temperament,” with pure octaves divided into twelve equal semitones, can play equally well-in-tune throughout such a complete traversal of keys.

, D, d, and so on). Only a keyboard tuned in something approaching “equal temperament,” with pure octaves divided into twelve equal semitones, can play equally well-in-tune throughout such a complete traversal of keys.

Equally well-in-tune actually means equally out-of-tune. Except for the octave, intervals composed of equal semitones do not correspond to those produced by natural resonance, known (after the well-known legend of their discovery) as “Pythagorean” intervals. The whole history of tuning has been one of compromise between natural resonance and practical utility. Since musical practice almost always demanded the ability to move from key to key—that is, to transpose scales so that their tonics and other harmonic functions are “keyed” to different pitches—and since the musical practice of the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries suddenly demanded the ability to do this with increasing freedom and variety within single pieces, it was precisely then that the idea of equalizing the semitones decisively overcame the long-standing resistance of fastidious musicians who objected to the total loss of undeniably beautiful “pure” fourths, fifths, and thirds.

Bach’s own preferred tuning was probably not yet quite equal. His practice may have accorded with that of Andreas Werckmeister (1645–1706), the author (in 1691) of the earliest treatise on equal temperament, who nevertheless declared himself willing “to have the diatonic thirds left somewhat purer than the other, less often used ones.” Bach and his contemporaries may in fact have relished the dramatizing effect of greater harmonic “impurity” in remote tonalities. And yet Bach’s twofold exhaustive cycle of preludes and fugues in all the keys celebrated what he clearly regarded as an ongoing triumph of practical technology, enabling a greatly enriched tonal practice that Bach, as we already know from the Toccata in F, was very quick to exploit.

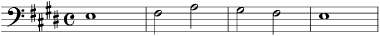

For this, too, Bach had an immediate model. Twenty years before he wrote the first volume of the “WTC,” in 1702, a south German organist and Kapellmeister named Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer published a collection of preludes and fugues under the title Ariadne musica, after the mythological princess who led the hero Theseus out of the Cretan labyrinth. The labyrinth, or maze, had long been a metaphor for wide-ranging tonal modulations, and Fischer’s nineteen prelude-and-fugue pairs are cast in as many keys. (The fact that five “remote” keys are missing from his traversal probably means Fischer presupposed one of several tunings in use at the time that, while basically “well-tempered,” were farther from equal than the one used by Bach.) As early as the sixteenth century, modulatory sets of this kind, placing tonics on all the semitones, had been written as curiosities for the lute, whose frets even then were set in something like equal temperament. But Fischer was undoubtedly Bach’s model, for Bach paid him tribute by quoting a few of his fugue subjects, for example the one in E major (no. 8 in Fischer, no. 9 in Bach).

EX. 6-2A J. C. F. Fischer, Ariadne musica, subject of the E-major Fugue

EX. 6-2B J. S. Bach, Das wohltemperirte Clavier, Book II, subject of the E-major Fugue

And yet just as in the case of Reincken, Bach far surpassed his model even as he kept faith with it. Not only did Bach complete the full representation of keys; he also greatly expanded the scope and the contrapuntal density of his model. And perhaps most significantly of all, he invested the music with his uniquely intense and emphatic brand of tonal harmony.

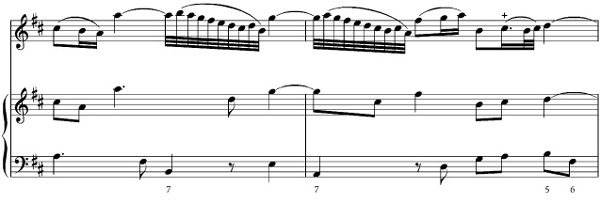

To take the full measure of the WTC in a brief description is impossible; yet something of its range of technique and its intensity of style may be gleaned by juxtaposing the very beginning and the very end of the first book: the C-major prelude and the exposition of the B-minor fugue (Ex. 6-3).

These are both famous pieces, albeit for very different reasons. The C-major prelude is a piece that every pianist encounters as a child. It is in a classic “preludizing” style that goes back to the lutenists of the sixteenth century. That style had been kept alive through the seventeenth century by the French court harpsichordists (or clavecinistes) who took over from their lutenist colleagues like the great Parisian virtuoso Denis Gaultier (1603–72) both the practice of composing suites of dances for their instrument, and also many “lutenistic” mannerisms such as the strumming or arpeggiated style Bach’s prelude continues to exemplify.

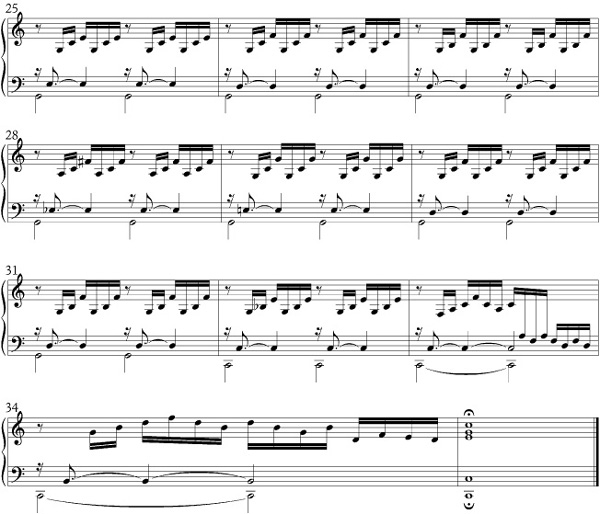

EX. 6-3A J. S. Bach, Das wohltemperirte Clavier, BookI, Preludeno. 1 (C major)

The French called it the style brisé or “broken [chord] style”; early written examples, like those of the claveciniste Louis Couperin (ca. 1626–61), preserve many aspects of what was originally an impromptu performance practice akin to the old lute ricercar, in which the player prefaced the main piece with a bit of preparatory strumming to capture the listeners’ attention and to establish the key. Couperin’s “unmeasured” preludes, like the one in Ex. 6-4, are especially akin to improvised lute-strumming. Their notation actually leaves the grouping and pacing of the arpeggios to the player’s discretion.

EX. 6-3B J. S. Bach, Das wohltemperirte Clavier, Book I, Fugue no. 24 (B minor), mm. 1–19

Thus, descending from a literally improvisatory practice, Ex. 6-3a is cast in a purely harmonic, “tuneless” idiom. (It was so tuneless as to strike later musicians as beautiful but incomplete. The French opera composer Charles Gounod [1818–93] actually wrote a melody, to the words of the antiphon Ave Maria, to accompany—or rather, to be accompanied by—Bach’s prelude. It is a familiar church recital piece to this day.) Even without a tune, though, Bach’s prelude has a very clearly articulated form—as well it might, since as we saw in the last chapter, it is harmony that chiefly articulates the form of “tonal” music even when melody is present.

EX. 6-4 Louis Couperin, unmeasured prelude

The first four measures establish the key by preparing and resolving a cadence on the tonic. Measures 5–11 prepare and resolve a cadence on the dominant: and note that even though all the chords are “broken,” the implied contrapuntal “voice leading” is very scrupulously respected. Dissonances, chiefly passing tones and suspensions, are always resolved in the same “voice.” Thus the suspended bass note C in m. 6 resolves to B in the next measure; the suspended B in m. 8 resolves to A in m. 9; the suspended G in the middle of the texture in m. 9 (its “voice” identifiable as the one represented by the fourth note in the arpeggio—let’s call it the alto) resolves to F in m. 10; while the suspended C in the soprano in that same measure resolves to B in m. 11.(Ex. 6-5 shows this progression in block chords, so that the voice leading can be traced directly.)

in m. 10; while the suspended C in the soprano in that same measure resolves to B in m. 11.(Ex. 6-5 shows this progression in block chords, so that the voice leading can be traced directly.)

EX. 6-5 J. S. Bach, Prelude no. 1, mm. 5–11, analyzed for voice leading

Measures 12–19 lead the harmony back to the tonic, characteristically employing a few chromaticized harmonies as a feint, to boost the harmonic tension prior to its final resolution. That resolution turns out not to be final, however: the tonic chord sprouts a dissonant seventh, turning it into a dominant of the subdominant; and the subdominant F in the bass, having passed (mm. 21–24) through a fairly wrenching chromatic double neighbor (F /A

/A ), settles on G, which is held as a dominant pedal for a remarkable eight measures (remarkable, that is, in a piece only 35 measures long) before making its resolution—a resolution accompanied by more harmonic feinting so that full repose is only achieved after four more measures. This apparently simple and old-fashioned composition conceals a wealth of craftsmanship, and in particular, it displays great virtuosity in the new art of manipulating tonal harmony.

), settles on G, which is held as a dominant pedal for a remarkable eight measures (remarkable, that is, in a piece only 35 measures long) before making its resolution—a resolution accompanied by more harmonic feinting so that full repose is only achieved after four more measures. This apparently simple and old-fashioned composition conceals a wealth of craftsmanship, and in particular, it displays great virtuosity in the new art of manipulating tonal harmony.

That new art is really put through its paces in the B-minor fugue (Ex. 6-3b), famous for its chromatic saturation and its attendant sense of pathos—a pathos achieved by harmony alone, without any use of words. The three-measure subject is celebrated in its own right for containing within its short span every degree of the chromatic or semitonal scale, a sort of maximally intensified passus duriusculus, which at the same time symbolically consummates the progress of the whole cycle “through all the tones and semitones.” What gives the subject, and the whole fugue, its remarkably poignant affect is not just the high level of chromaticism, but also the way in which that chromaticism is coordinated with what, even on their first “unharmonized” appearance, are obviously dissonant leaps—known technically as appoggiaturas (“leaning notes”). The two leaps of a diminished seventh in the second measure are the most obviously dissonant: the jarring interval is clearly meant to be heard as an embellishment “leaning on” the minor sixth that is achieved when the first note in the slurred pair resolves by half step: C-natural to B, D to C . But in fact, as the ensuing counterpoint reveals, every first note of a slurred pair is (or can be treated as) a dissonant appoggiatura.

. But in fact, as the ensuing counterpoint reveals, every first note of a slurred pair is (or can be treated as) a dissonant appoggiatura.

A thorough analysis of mm. 9–15, encompassing the entries of the third (bass) and fourth (soprano) voices, will reveal an astonishing level of dissonance on the strong beats, where the appoggiaturas fall. The bass G in m. 9 is harmonized with a tritone; the B on the next beat clashes with the C above; the E on the downbeat makes the same clash against the F

above; the E on the downbeat makes the same clash against the F above; the C that follows is harmonized with a tritone; the F

above; the C that follows is harmonized with a tritone; the F that comes next, with a fourth and a second; and the D on the fourth beat of m. 10 creates a seventh against the suspended C

that comes next, with a fourth and a second; and the D on the fourth beat of m. 10 creates a seventh against the suspended C . Most of these dissonances are created not by suspensions but by direct leaps—the strongest kind of dissonance one can have in tonal music. Turning now to the soprano entrance in m. 13, we find a tritone and a diminished seventh against the D on the third beat; a leapt-to seventh on the fourth; a simultaneous clash of tritone, seventh, and fourth on the ensuing downbeat; a tritone against the sustained B on the second beat; another leapt-to seventh on the third beat, and so it goes.

. Most of these dissonances are created not by suspensions but by direct leaps—the strongest kind of dissonance one can have in tonal music. Turning now to the soprano entrance in m. 13, we find a tritone and a diminished seventh against the D on the third beat; a leapt-to seventh on the fourth; a simultaneous clash of tritone, seventh, and fourth on the ensuing downbeat; a tritone against the sustained B on the second beat; another leapt-to seventh on the third beat, and so it goes.

It will come as no surprise to learn that these slurred descending pairs with dissonant beginnings were known as Seufzer—“sighs” or “groans”—and that they had originated as a kind of word-painting or madrigalism. The transfer of vivid illustrative effects, even onomatopoeias, into “abstract” musical forms shows that those forms, at least as handled by Bach, were not abstract at all, but fraught with a maximum of emotional baggage. What is most remarkable is the way Bach consistently contrives to let the illustrative idea that bears the “affective” significance serve simultaneously as the motive from which the musical stuff is spun out.

Structure and signification, “form” and “content,” are thus indissolubly wedded, made virtually synonymous. That was the expressive ideal at the very root of the “radical humanism” that gave rise to what Monteverdi (unbeknown to Bach) had called the seconda prattica a hundred years before. Monteverdi could only envisage its realization in the context of vocal music (where “the text will be the master of the music”). He never dreamed that such an art could flourish in textless instrumental music. That was what Bach, building on a century of musical changes, would achieve within an outwardly old-fashioned, even backward-looking career.

Clearly, Bach’s art had a Janus face. Formally and texturally it looked back to what were even then archaic practices. In terms of harmony and tonally articulated form, however, it was at the cutting edge. That cutting edge still pierces the consciousness of listeners today and calls forth an intense response, while the music of every other Lutheran cantor of the time has perished from the actual repertory.

The other traditional genre that Bach inherited directly from his Lutheran organist forebears, and from Buxtehude most immediately, was the chorale setting. This was a protean genre. It could assume many forms, anywhere from a colossal set of improvised or composed variations (the type with which Bach enraptured Reincken and called forth his blessing) to a minuscule Choralvorspiel or “chorale prelude,” a single-verse setting with which the organist might cue the congregation to sing, or provide an accompaniment to silent meditation. The chorale melody in such a piece might be treated strictly as a cantus firmus, or else melodically embellished, or else played off against a ritornello or a ground bass, or else elaborated “motet-style” into points of fugal imitation based on its constituent phrases.

Toward the end of his Weimar period, ever the encyclopedist and the synthesizer, Bach set about collecting his chorale preludes into a liturgical cycle that would cover the whole year’s services. He had only inscribed forty-six items out of a projected 164 in this manuscript, called the Orgelbüchlein (“Little organ book”), when he was called away to Cöthen. But in their variety, the ones entered fully justify Bach’s claim on the manuscript’s title page, that in his little book “a beginner at the organ is given instruction in developing a chorale in many diverse ways.” We can compare Buxtehude and Bach directly, and in a manner that will confirm our previous comparisons, by putting side by side their chorale preludes—Bach’s from the Orgelbüchlein—on Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt (“Through Adam’s fall we are condemned,” Ex. 6-6).

Although the first line makes reference to what for Christians was the greatest catastrophe in human history, the real subject of the chorale’s text is God’s mercy by which man may be redeemed from Adam’s original sin through faith in Jesus Christ.

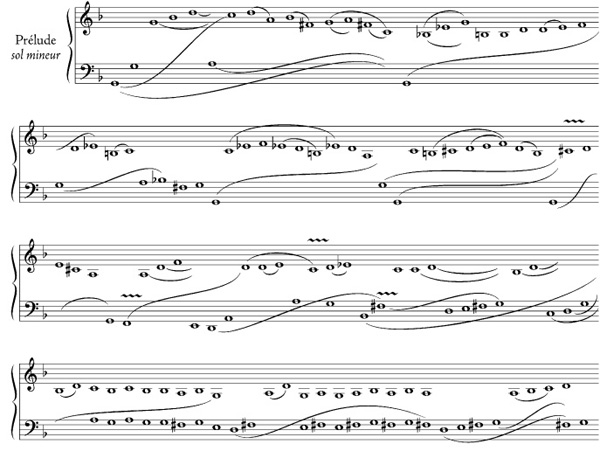

EX. 6-6A Dietrich Buxtehude, Durch Adams Fall, mm. 1–23

EX. 6-6B J. S. Bach, Durch Adams Fall (Orgelbüchlein, no. 38)

Nevertheless, it is the first line that sets the tone for the setting, since the first verse is the one directly introduced by the prelude. Both Buxtehude’s prelude and Bach’s, therefore, are tinged with grief. The chorale melody, treated plain by Bach, with some embellishment by Buxtehude, is surrounded by affective counterpoints.

In Buxtehude’s case the affect is created by chromatically ascending and descending lines that enter after a curious suppression of the bass. In Bach’s setting, the most striking aspect is surely the pedal part. This in itself is no surprise: spotlighting the pedal part was one of Bach’s special predilections, as we already know from the Toccata in F (Ex. 5-15), and fancy footwork was one of his specialties as an organ virtuoso. On the title page of the Orgelbüchlein, which he intended to publish on completion, Bach included a little sales pitch, promising that the purchaser will “acquire facility in the study of the pedal, since in the chorales contained herein, the pedal is treated as wholly obbligato,” that is, as an independent voice.

What is a powerful surprise, and further evidence of Bach’s unique imaginative boldness, is the specific form the obbligato pedal part takes in this chorale setting: almost nothing but dissonant drops of a seventh—Adam’s fall made audible! And not just the fall, but also the attendant pain and suffering are depicted (and in a way evoked), since so many of those sevenths are diminished. A rank madrigalism, the fall, is given emotional force through sheer harmonic audacity and is then made the primary unifying motive of the composition. Again the union of illustration and construction, symbolic image and feeling, “form” and “content,” is complete. And if, as seems likely, Buxtehude meant the three falling fifths that accompany the first phrase of the chorale in the bass to symbolize the fall, we have another case of Bach’s propensity to emulate—to adopt a model and then surpass it to an outlandish degree, amounting to a virtual difference in kind.

The same attitude Bach displayed in intensifying and transforming the traditional techniques of his trade characterized his relationship to all the styles of his time. Despite the seemingly cloistered insularity of his career, he nevertheless mastered, and by his lights transcended, the full range of contemporary musical idioms. In part this was simply a matter of being German. At a time when French and Italian musicians were mutually suspicious and much concerned with resisting each other’s influence, German musicians tended to define themselves as universal synthesists, able (in the words of Johann Joachim Quantz, a colleague of C. P. E. Bach’s at the Prussian court) “to select with due discrimination from the musical tastes of various peoples what is best in each,” thereby producing “a mixed taste which, without overstepping the bounds of modesty, may very well be called the German taste.”2 Bach became its ultimate, most universal, exponent.

But he had many predecessors. We know how eagerly Heinrich Schütz, born a hundred years before Bach, had imported the Italian styles of his day to Germany. A younger contemporary of Schütz, the sometime Viennese court organist Johann Jacob Froberger (1616–67), a native of Stuttgart in southern Germany, traveled the length and breadth of Europe, soaking up influences everywhere. After a period (approximately 1637 to 1640) spent studying with Frescobaldi in Rome, Froberger visited Brussels (then in the Spanish Netherlands), Paris, England, and Saxony. He died in the service of a French-speaking German court in the Rhineland, the westernmost part of Germany.

The first whole book of pieces by Froberger to be (posthumously) published was eminently Frescobaldian: Diverse curiose partite, di toccate, canzone, ricercate etc. (“Assorted off-beat toccatas, canzonas, ricercars and so on”). Four years later, there followed a book containing Dix suittes de clavessin (“Ten suites for harpsichord”), in a style that comported perfectly with the language of the title page. This book of suites would be by far Froberger’s most influential publication. By century’s end, the French style had become a veritable German fetish, the object of intense envy and adaptation. Envy played an important role because it was envy of the opulent French court on the part of the many petty German princelings that led to the wholesale adoption of French manners by the German aristocracy. French actually became the court language of Germany, and French dancing became an obligatory social grace at the many mini-Versailleses that dotted the German landscape.

With dancing, of course, came music. Demand for French (or French-style) ballroom music, and for instruction in composing and playing it, became so great that by the end of the seventeenth century a number of German musicians, sensing a ready market, had set themselves up in business as professional Gallicizers. One of these was Georg Muffat (1653–1704), an organist at the episcopal court at Passau, who had played violin as a youth under Lully in Paris. In 1695 he published a set of dance suites in the Lullian mold, together with a treatise on how to play them in the correct Lullian “ballet style.” His rules, especially those concerning unwritten conventions of rhythm and bowing, have been a goldmine to today’s “historical” performers, who need to overcome a temporal distance from the music comparable to the geographical distance Muffat’s original readers confronted.

Another Gallicizer was J. C. F. Fischer, with whose Ariadne we are already acquainted. His Opus 1 was a book of dance suites for orchestra called Le journal de printems (“Spring’s Diary,” 1695), in which he prefaced the dances, originally composed for the ballroom of the Margrave Ludwig of Baden, with Lully-style overtures. Although the components were all French, this type of orchestral “overture suite” was in fact a German invention, pioneered by Johann Sigismund Kusser (or “Cousser,” à la française) a sort of Froberger of the violin who studied in Paris with Lully and then plied his trade all over Europe, ending up in Dublin, where he died in 1727. Orchestral suites of this kind, actually called ouvertures after their opening items, remained a German specialty. Telemann, cited by the Guinness Book of World Records as the most prolific composer of all time, composed around 150 of them.

Fischer’s op. 2, titled Musicalisches Blumen-Büschlein (“A little musical flower bush,” 1696), was a book of harpsichord suites on the Froberger model. Between the two of them, Froberger’s publication and Fischer’s managed to establish a standard suite format that provided the model for all their German or German-born successors. Froberger’s contribution was the truly fundamental one: it was he who adopted a specific sequence of four dances as essential nucleus in all his suites, setting a precedent that governed the composition of keyboard suites from then on. Fischer prefaced his suites with preludes, some patterned on the style brisé, others on the toccata. This, too, became an important precedent, albeit not quite as universally observed by later composers. (Bach, for example, composed suites both with and without preludes, but always included Froberger’s core dances.)

It is worth emphasizing that Froberger’s core dances had, by the time he adapted them, pretty much gone out of actual ballroom use. They had been sublimated into elevated courtly listening-music by the master instrumentalists of France, which meant slowing them down and cramming them full of interesting musical detail that would have been lost on dancers. The typical French instrumental manuscript or publication of the day, whether for lute, for harpsichord, or for viol, generally consisted of several vast compendia of idealized dance pieces in a given key, each basic type being multiply represented. The French composers, in other words, did not write actual ready-made suites, but provided the materials from which players could select a sequence (that is, a suite) for performance. It was Froberger and his German progeny who began, as it were, “preselecting” the components, thus casting their suites as actual multimovement compositions like sonatas.

The four favored dances, chosen for their contrasting tempos and meters (and, consequently, their contrasting moods), were these:

1. Allemande. This dance had a checkered history. As its name suggests, it originated in Germany, but by the time German composers borrowed it back from the French it had changed utterly. In its original form it was a quick dance in duple meter. The first keyboard examples are by the English virginalists, who called it the alman, and Frescobaldi, who called it the bal tedesco or balletto. It was Gaultier and his claveciniste contemporary Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (1602–72) who slowed it down into a stately instrumental solo in a broad four beats per bar and a richly detailed texture. It was this elegantly dignified allemande, never before heard in Germany, that Froberger borrowed back and ensconced permanently in the opening slot of his standard suite.

2. Courante. In its older form, more often called (in Italian) corrente, this was a lively mock-courtship dance, notated in  or even

or even  meter. (Examples can be found in any Corelli sonata da camera; see Ex. 5-1.) The idealized French type borrowed by Froberger was just the opposite: the gravest of all triple-time suite pieces, notated in

meter. (Examples can be found in any Corelli sonata da camera; see Ex. 5-1.) The idealized French type borrowed by Froberger was just the opposite: the gravest of all triple-time suite pieces, notated in  with many lilting hemiola effects in which

with many lilting hemiola effects in which  patterns cut across the

patterns cut across the  pulse.

pulse.

3. Sarabande. Of all the suite dances, this one underwent the most radical change in the process of sublimation. It originated in the New World and was brought back to Europe, as the zarabanda, from Mexico. In its original form it was a breakneck, sexy affair, accompanied by castanets. Like the passacaglia or chaconne, it consisted originally of a chordal ostinato and is first found notated in Spanish guitar tablatures. Banned from the Spanish ballroom by decree for its alleged obscenity, it was idealized in a deliberately denatured form, becoming (like the chaconne) a majestic triple-metered dance for the ballet stage, often compared to a slow minuet. As borrowed by Froberger, it usually had an accented second beat, rhythmically expressed by a lengthened (doubled or dotted) note value.

4. Gigue. Imported to Europe from England and Ireland, the jig was (typically) danced faster in Italy (as the giga), in more leisurely fashion by the more self-conscious bluebloods of the French court and their German mimics. In its idealized form, the gigue usually began with a point of imitation, which (as we have already observed in Reincken and Bach) was often inverted in the second strain.

A “binary” or double-strain structure (AABB), supported by a there-and-back harmonic plan, was a universal feature of suite dances, particularly as adopted by Germans. (In France there was an alternative: the so-called pièce en rondeau, in which multiple strains alternated with a refrain.) In the hands of Bach and his contemporaries, the binary dance became another important site for developing the kind of tonally articulated form that conditioned new habits of listening and formed the bedrock of the standard performing repertory.

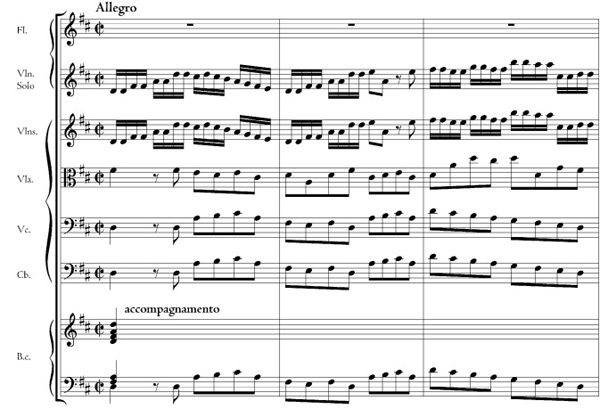

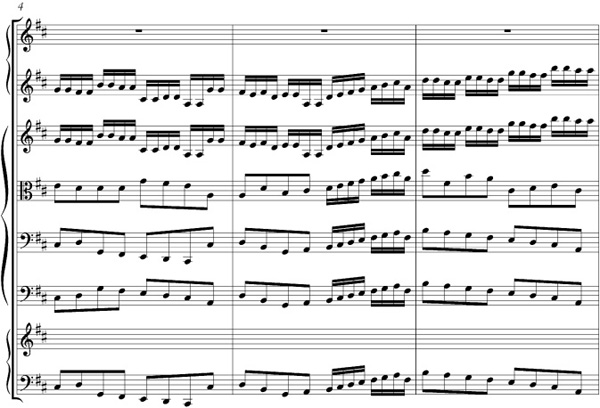

As we know, Bach never went to France. Instead, France came to him through the musical publications that circulated widely in the Gallicized musical environment that was Germany. Bach made his most thorough assimilation of the French style when he was professionally required to do so. That was in 1717, when he left Weimar for the position of Kapellmeister in Cöthen. This was an entirely secular position, the only such position Bach ever occupied and an unusual one for any “Bach.” His new employer, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, was a passionate musical amateur, who esteemed Bach highly and related to him practically on terms of friendship. (He even stood godfather to one of Bach’s children.) Leopold not only consumed music avidly but played it himself (on violin, bass viol or viola da gamba, and harpsichord) and had even studied composition for a while in Rome with Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729), a notable German musician of the day. He maintained a court orchestra of eighteen instrumentalists, including some very distinguished ones. And he was a Calvinist, which meant he had no use for elaborate composed church music or fancy organ playing. So Bach had no call to compose or play in church and could devote all his time to satisfying his patron’s demands for musical entertainments.

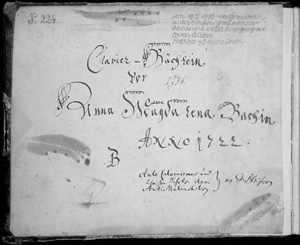

FIG. 6-7 Title page of Anna Magdalena Bach’s music book (Clavier-Büchlein), 1722.

Thus for six years Bach wrote mainly instrumental music. The first book of the WTC dates from the Cöthen period, as we know, but that was done on the side. The kind of entertainments demanded of Bach as part of his official duties would have taken the form of sonatas, concertos, and above all, suites. Bach turned out several dozen of the latter, ranging from orchestral ouvertures through various sets for keyboard, to suites for unaccompanied violin and even cello, the latter unprecedented as far as we know. He even wrote a couple of suites for the practically obsolete lute, the historical progenitor of the idealized suite-for-listening, which still had a few devotees in Germany.

Most of Bach’s keyboard suites are grouped in three sets, each containing six of them. The earliest is a set of six large suites with elaborate preludes and highly embellished sarabandes, probably composed in Weimar around 1715. They were published posthumously as “English Suites,” and have been called that ever since, although no one really knows why. The set published (also posthumously) as “French Suites” are close to the Froberger model. The four dances standardized by Froberger provide the core, with a smaller group of faster and lighter “modern” dances interpolated between the sarabande and the gigue. Of the six French Suites, five are found in one of the music books of Anna Magdalena Bach, the composer’s second wife. They were probably composed for the private enjoyment of Bach’s family and the instruction of his children.

The final group of six, though written at Cöthen, were assembled, engraved, and published by Bach himself at Leipzig in 1731, as the first volume of an omnibus keyboard collection unassumingly titled Clavier-Übung (“Keyboard practice”). Bach borrowed the name from his predecessor as Leipzig cantor, Johann Kuhnau, who published a set of keyboard suites under that title in 1689. Bach also followed Kuhnau in calling the suites contained therein by the old-fashioned (and somewhat misleading) title “partitas.” When we last encountered it (chapter 2), the word “partita” referred to a set of variations, in Lutheran countries often based on chorale melodies. Bach’s fame has firmly implanted his unusual usage in the common vocabulary of music. When musicians use the word “partita” now, it almost always means a dance suite.

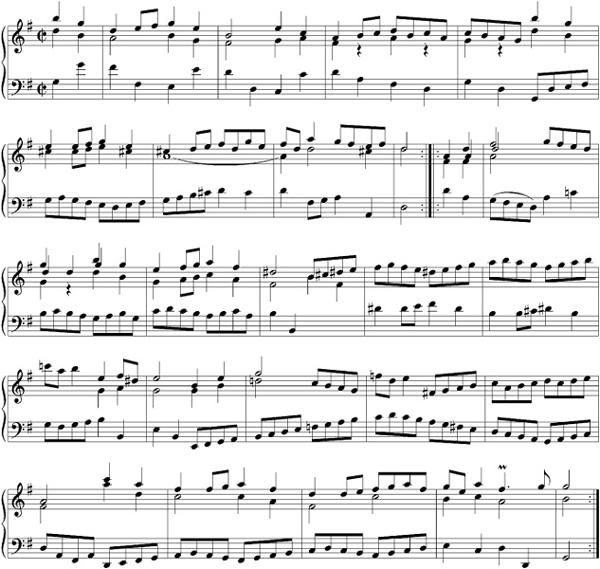

The nucleus of Bach’s fifth French Suite, in G major, consists of the Frobergerian core of allemande, courante, sarabande, and gigue, augmented by a trio of slighter dances (a gavotte, a bourée, and a loure) interpolated before the gigue. Bach himself used the term Galanterien (from the French galanteries) on the title page of the Clavier-Übung to classify these interpolated dances and distinguish them from the core, describing his suites (or partitas) as consisting of “Präludien, Allemanden, Couranten, Sarabanden, Giguen, Menuetten, und anderen Galanterien.” Note that the obligatory or core dances are listed (after the preludes) in order, while the variable category of “minuets and other galanteries” is mentioned casually, out of order, as if an afterthought. This contrast in manner is very telling.

Even though the word galanterie can be translated as a “trifle,” it denotes a very important esthetic category. It is derived from what the French called the style galant, which stemmed in turn from the old French verb galer, which meant “to amuse” in a tasteful, courtly sort of way, with refined wit, elegant manners, and easy grace. It was a quality of art—and life—far removed from the stern world of the traditional Lutheran church, and Bach never fully reconciled the difference between the sources that fed his creative stream.

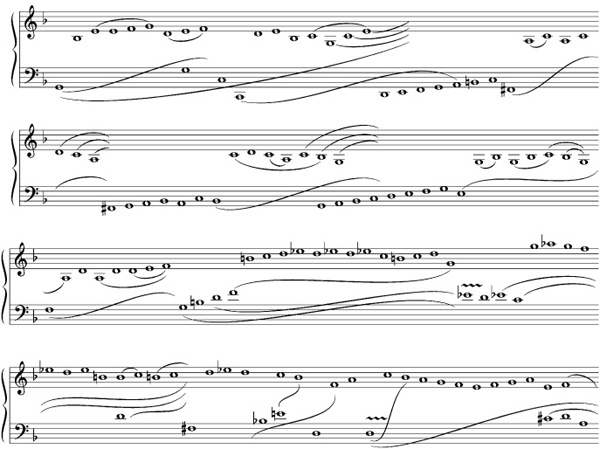

EX. 6-7A J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Allemande

To put Bach’s allemande (Ex. 6-7a) alongside one written sixty or seventy years earlier by Froberger (Ex. 6-7b) is to marvel at the sheer persistence of the French courtly style in Germany. The old style brisé, in which the harpsichord aped the elegant strumming of a lute, informs both pieces equally, although Froberger learned it directly from the lutenists (one of his best known pieces being a tombeau, or “tombstone,” an especially grave allemande or pavane composed in memoriam, for the Parisian lutenist Blancrocher, a friend), while Bach would have learned it from Froberger, from Kuhnau, and from their followers.

EX. 6-7B Johann Jakob Froberger, Suite in E minor, Allemande

The difference between the pieces is the usual difference between Bach and his predecessors or contemporaries. Although not much longer than Froberger’s (twenty-four measures as against twenty), Bach’s makes a far more distinctive and developed impression thanks to two characteristic features, one melodic and the other harmonic. The opening motive of Bach’s allemande, a three-beat ascent of a third (with pickups and a distinguishing trill), is treated thematically—that is, as a form-definer—in a way that was unknown to Froberger.

While Froberger had at his disposal characteristic ways of articulating the melodic shape of his composition—for example, the three-note pickup that begins each half—Bach uses the opening motive to lend the two halves of his allemande a sense of thematic parallelism, echoing on the melodic plane the overall symmetry of design that is chiefly articulated by the harmony. Coordination of the harmonic and melodic spheres is additionally confirmed by the use of the opening motive, replete with defining trill, to point the cadences in m. 4 (which establishes the tonic) and in m. 5 (which launches the movement to the dominant). For an even more dramatic illustration of how conscious and deliberate Bach’s motivic writing could be, compare a passage from one of his concertos (for two harpsichords in C major, probably composed later in Leipzig), in which the same opening figure from the allemande is dramatically proclaimed as a “headmotive” that introduces the main ritornello and is also developed antiphonally as an episode (Ex. 6-7c and d).

As to harmony, both allemandes follow the same there-and-back pendular motion between tonic and dominant that defines the “binary” form of a dance, but Bach’s ranges wider and is at the same time more sharply focused. Each half of Froberger’s dance follows a single motion between harmonic centers with no major stops along the way. Each half of Bach’s, by contrast, is divided into two distinct phrases, keenly marked by cadences. The first phrase, mm. 1–4, begins and ends with the tonic, thus reinforcing it by closure. The balancing phrase, mm. 5–12, establishes the dominant as cadential goal. (Actually, the dominant is reached at m. 8, so that the phrase has two equal components, one that “moves” and the other that “re-arrives” after some interesting chromatic digressions.)

EX. 6-7C J. S. Bach, Concerto in C for Two Harpsichords, BWV 1061, I, mm. 1–4

EX. 6-7D J. S. Bach, Concerto in C for Two Harpsichords, BWV 1061, I, mm. 28–32

The second half of Bach’s allemande is divided more equally than the first. Its first phrase, mm. 13–18, moves from the dominant not straight back to the tonic but to a “secondary function” (that is, a chord with opposite quality from the tonic), in this case E minor, the submediant. The concluding phrase finally zeroes back on the tonic, harking back to the “interesting chromatic digressions” from the first half to signal its impending arrival.

That shape will henceforth serve as paradigm for a fully “tonal” binary form. The new elements include the care with which the tonic is established (almost the way a ritornello might establish it in a concerto movement), and the compensating feint in the direction of some “far out point” (henceforth FOP) in the second half of the piece to redirect the harmonic motion home with renewed force. Once again Bach is out in front of his contemporaries in harnessing the power of tonality to steer the course of a composition through a sort of journey, and to take the measure of its distance, at all points, from “home.”

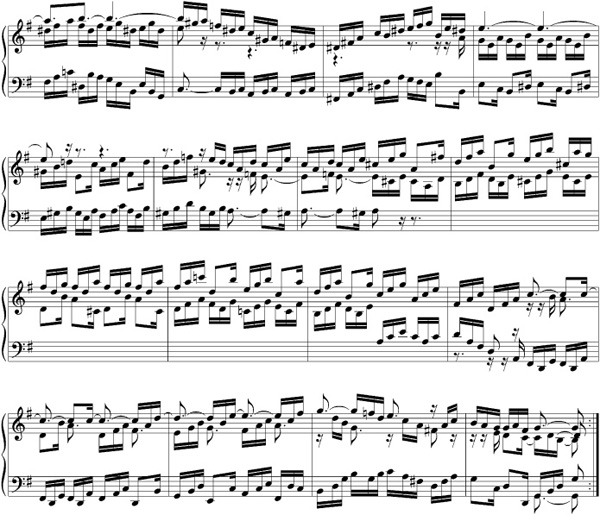

The other movements in the French Suite all confirm this basic pattern of harmonic motion, in which the simple “binary” there-and-back is amplified and extended by means of an initial closure on the tonic to emphasize departure, and an excursion to a FOP on the way back, thus: Here-there-FOP-back. In the Italian-style courante or corrente (Ex. 6-8a), the cadential points are distributed with perfect regularity, as follows: m. 8 (I), m. 16 (V), m. 24 (vi), m. 32 (I). Compare the tonally much more elusive French-style courante from the third French Suite in B minor (Ex. 6-8b), in which the cadence points are quite unpredictably and asymmetrically distributed among its 28 spacious measures: m. 5 (i), m. 12 (V), m. 19 (iv), m. 28 (i).

Note, too, how every pre-cadential measure in Ex. 6-8b (i.e., mm. 4, 11, 18, and 27) foreshadows the cadence by speeding up the harmonic rhythm (that is, the rate of harmony-change) and by regrouping the measure’s six quarter notes by pairs rather than by threes, producing a so-called “hemiola” pattern of three beats in the normal time of two. (The pre-cadential bars are not the only ones that are felt in “ ” rather than “

” rather than “ ”: the surest signal for hemiola grouping is the presence of a dotted quarter note, usually trilled, on the fifth beat.) By comparison with the stately old-style French courante (the only kind Froberger knew), the Italianate type—by virtue of its rhythmic evenness, its regular cadences, and its uncomplicated, predominantly two-voiced texture—is practically a galanterie.

”: the surest signal for hemiola grouping is the presence of a dotted quarter note, usually trilled, on the fifth beat.) By comparison with the stately old-style French courante (the only kind Froberger knew), the Italianate type—by virtue of its rhythmic evenness, its regular cadences, and its uncomplicated, predominantly two-voiced texture—is practically a galanterie.

EX. 6-8A J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Courante

EX. 6-8B J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 3 in B minor, Courante

In the sarabande (Ex. 6-9), the cadence points again evenly divide the first half. In contrast, the second half is elaborately subdivided into sections cadencing on two FOPs (ii in m. 20 and vi in m. 24), and the trip back to the tonic is subarticulated with stops on the subdominant (m. 28) and the dominant (m. 36) before finally touching down at the end (m. 40). The result is a colorfully lengthened, but also strengthened, harmonic structure.

EX. 6-9 J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Sarabande

While of course slighter, the galanteries (Ex. 6-10a-c) observe similar tonal proportions. The gavotte (Ex. 6-10a), a buoyant dance with beats on the half note and a characteristic two-quarter pickup, has cadences on mm. 4 (I), 8 (V), 16 (vi), and 24 (I). Notice that the tendency to expand the second half, already apparent in the sarabande, is maintained here as well by doubling the phrase lengths, though without the addition of any supplementary cadence points. The bourrée (Ex. 6-10b), a rambunctious stylized peasant dance in two quick beats per bar, has its cadences more irregularly placed: mm. 4 (I), 10 (V), 18 (vi), 30 (I). That irregularity is part of its galant or witty charm: each phrase is longer than the last, and the listener is kept guessing how much longer.

The loure (Ex. 6-10c), one of the rarer dances, might be described as a heavy (lourd) or rustic gigue in doubled note values. (In the sixteenth century the word loure was used for a certain kind of bagpipe, but whether that is the source of the dance’s name is unclear.) Its meter and note values resemble those of the “true” French courante (as in Ex. 6-8b), but its rhythms—particularly the pattern  already familiar from the Scarlattian siciliano—are gigue-like. Altogether unlike those of the courante in Ex. 6-8b, the cadences of Bach’s loure are distributed with perfect regularity (mm. 4, 8, 12, 16). The supertonic (ii), somewhat unusually, is used in place of the submediant (vi) as FOP.

already familiar from the Scarlattian siciliano—are gigue-like. Altogether unlike those of the courante in Ex. 6-8b, the cadences of Bach’s loure are distributed with perfect regularity (mm. 4, 8, 12, 16). The supertonic (ii), somewhat unusually, is used in place of the submediant (vi) as FOP.

EX. 6-10A J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Gavotte

EX. 6-10B J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Bourée

EX. 6-10C J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Loure

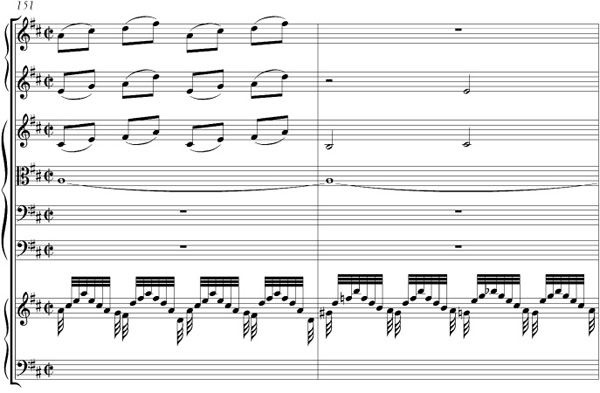

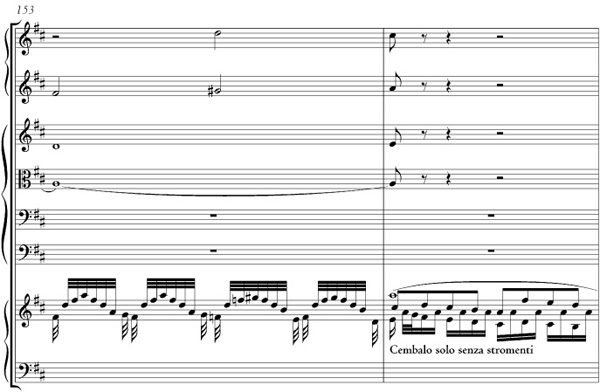

Finally, the gigue (Ex. 6-11): with its 56-bar length (distributed 24 + 32) and its fugal expositions in three real parts, it is the most elaborate dance of all. Tracking cadences here is complicated by the behavior of the fugal writing, which has its own pendular rhythm. The first fugal exposition makes its final tonic cadence on the third beat of m. 9, and the dominant is reached by the third beat of m. 14, when the bass enters with the subject. Final confirmation of arrival on V comes, after a lengthy episode, in m. 24. The second half begins, just as Bach’s gigue after Reincken (Ex. 6-1b) had begun, with an inversion. As befits a dance (if not a fugue), this inverted exposition ends, somewhat indefinitely, on a FOP (either vi in m. 37 or ii in m. 38). The bass then enters with the subject on the dominant of vi, to start steering the course through a slow circle of fifths toward home.

To conclude this little study of the French Suite No. 5, two more comparisons are in order, one “internal,” and the other “external.” The internal distinction, of course, is that between the styles of the traditional “obligatory” dances and the galanteries. Putting the allemande next to the gavotte shows how radically they differ. The textural and harmonic richness of the allemande’s style brisé contrasts with the virtual homophony of the gavotte; the subtle spun-out phrases of the one with the square-cut strains of the other; the placid, equable rhythms of the former with the highly contrasted, vivacious rhythms of the latter.

These musical (“technical”) differences are symptomatic of a fundamental difference in taste, one that would eventually mark the eighteenth century as a kind of esthetic battleground. With Bach, the galant, while certainly within his range, is nevertheless the exceptional style—the sauce rather than the meat. With most of his contemporaries, the balance had rather decisively shifted to the opposite.

Here is where the external comparison comes in. Consider another gigue to set beside Bach’s: the one that opens the fourteenth ordre, or “set,” of harpsichord pieces (published in 1722) by Bach’s greatest keyboard-playing contemporary, François Couperin (1668–1733), royal organist and chief musicien de chambre to Louis XIV (Ex. 6-12). Couperin’s is a “set” rather than a suite because, following traditional French practice, the pieces in it, while related by key, are too numerous to be played or heard in one sitting and are not placed in performance order. One fashioned one’s own suite from such a set ad libitum.

EX. 6-11 J. S. Bach, French Suite no. 5 in G major, Gigue

Couperin’s gigue (Ex. 6-12a) is not identified as such by title. It is, rather, identifiable by its rocking  meter. That is the normal gigue meter; Bach’s

meter. That is the normal gigue meter; Bach’s  is a diminution, betokening a faster tempo than usual. That tempo, since it is conventional, can be conveyed by the notation alone, without any ancillary explanation. And indeed, none of the dances in Bach’s suite carry any verbal indications as to their tempo. Such indications were not needed. The name of the dance, the meter, and the note values conveyed all the essential information.

is a diminution, betokening a faster tempo than usual. That tempo, since it is conventional, can be conveyed by the notation alone, without any ancillary explanation. And indeed, none of the dances in Bach’s suite carry any verbal indications as to their tempo. Such indications were not needed. The name of the dance, the meter, and the note values conveyed all the essential information.

FIG. 6-8 François Couperin (ex collection André Meyer).

But the situation with Couperin’s gigue, one of his most famous pieces (and rightly so), is just the opposite. It is not called “gigue,” but Le Rossignol en amour, “The Nightingale in Love”! It is not really a dance at all, but a “character piece” or (to use Couperin’s own word) a sort of “portrait” in tones, cast in a conventional form inherited from dance music. The subject portrayed is ostensibly a bird, and the decorative surface of the music teems with embellishments that seem delightfully to imitate the bird’s singing. But since (according to the title) the bird in question is incongruously experiencing a human emotion, the musical imitation is simultaneously to be “read” as a metaphor—a portrait not just of the bird but of the emotion, too, in all its tenderness, its languorousness, its “sweet sorrow.”

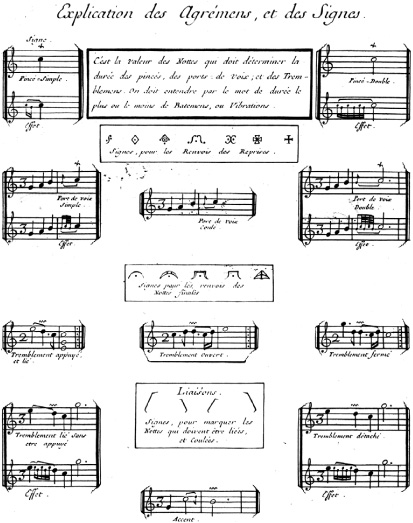

Since the conventional tempo of a gigue contradicts tenderness or languor, Couperin had to countermand it with a very detailed verbal indication, directing the performer to play “slowly, and very flexibly, although basically in time.” At the stipulated tempo there is room for a great wealth of embellishment, all indicated with little shorthand signs that Bach also used, and that are (mostly) still familiar to piano students today. The first sign in order of appearance, which Couperin called the pincée (a “pinched note”) and which we now call a mordant, is a rapid alternation of the written note with its lower neighbor on the scale. The second, which Couperin called tremblement (“trembling”) and we now call a short trill (or, sometimes, a shake), is a rapid and repeated alternation of the written note with its upper neighbor.

Such conventionalized, localized ornaments, called “graces” in English at the time, and agrémens in French, were learned “orally”—by listening to one’s teacher and imitating, the way instrumental technique has always been (and will always be) imparted. There were tables of reference, of course, and many composers compiled them. Couperin’s (published as an insert to his first book of harpsichord pieces in 1713) is shown in Fig. 6-9. For an even more intense or less conventionalized expression, one resorted to specifically composed embellishments.

EX. 6-12A François Couperin, Le Rossignol en amour (14th Ordre, no. 1), beginning

Lentement, et tres tendrement, quoy measuré

That is what Couperin does in his coda or petite reprise, where he notes that the speed of the written-out trill is to be “increased by imperceptible degrees” for an especially spontaneous (or especially ornithological) burst of feeling. And then he follows the whole piece with a “fancy version” or double (Ex. 6-12b), in which the surface becomes a real welter of notes, and where it becomes the supreme mark of skillful performance to keep the lineaments of the original melody in the foreground. (Perhaps that is why Couperin recommends in a footnote that the piece be played as a flute solo, for the flutist can use flexible dynamic shading and a true legato, while a harpsichordist must “fake” both.) Agrémens are still used plentifully in a double, but they are supplemented with turns and runs that have no conventional shorthand notation. Bach’s most notable doubles are those he wrote for the sarabandes in his “English” suites (although he called them, a little incorrectly, “agrémens”).

FIG. 6-9 “Explication des Agremens, et des Signes,” from Couperin’s first book of Pièces de clavecin (Paris, 1713).

Miniatures that display the kind of exquisitely embellished, decorative veneer Couperin knew so well how to apply are often called rococo, a kind of “portmanteau word” formed by folding together two French words: rocaille and coquille, the “rock-” or “grotto-work” and “shell-work” featured in expensively textured architectural surfaces of the period. Were the decorative surface stripped away from Couperin’s pièce, the simplest of shapes would remain: cadences come every four bars (the last one delayed by two bars of “plaintive iterations”), describing a bare-bones tonal trajectory of I–V/V–I. Nor is the emotion expressed one of great vehemence or intensity. Rococo art expressed the same sort of aristocratic, “public” sentiments (including the sort of amorous or melancholy sentiments that can be aired in polite society) that we have already identified as galant. The strong pathos of Bach’s B-minor fugue (Ex. 6-3b) would have been as out of place in such company as it would be in the music of Couperin.

There was a place for such emotion, of course, and for a style of embellishment that expressed it, in the Italian art associated with the opera; and although Bach wrote no operas, he was well acquainted with the music of his Italian contemporaries and much affected by it. By Bach’s time a great deal of Italian instrumental music aspired to an “operatic” intensity of expression; recall some of the “frightening” work of Corelli and Vivaldi from the previous chapter. And there was a concomitant style of instrumental embellishment, allied to, and perhaps in part derived from, the fioritura of the castrati and the other virtuosi of the Italian opera stage.