“Bach is the father, we are the kids” (Bach ist der Vater, wir sind die Buben), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was once quoted, perhaps apocryphally, as saying.1 Only it was not J. S. Bach of whom he said it. “Old Sebastian,” as Mozart called him, was just a dimly remembered grandfather until the last decade of Mozart’s career, when (slightly in advance of the public revival described in the previous chapter) Mozart first got to hear the works of J. S. Bach and G. F. Handel, then virtually unperformed outside of the composers’ home territory—northern Germany in the case of Bach and Great Britain in the case of Handel. It was at the home of Baron Gottfried van Swieten, a Dutch-born Viennese aristocrat who maintained a sort of antiquarian salon, that Mozart made their acquaintance. The baron commissioned from Mozart modernized scores of Handel’s Messiah and other vocal works for performance at his soirées. Although the works of Handel and Bach made a big impression on the van Swieten circle, the very fact that they needed to be updated for performance in the 1780s shows how far their works had fallen out of the practical repertoire.

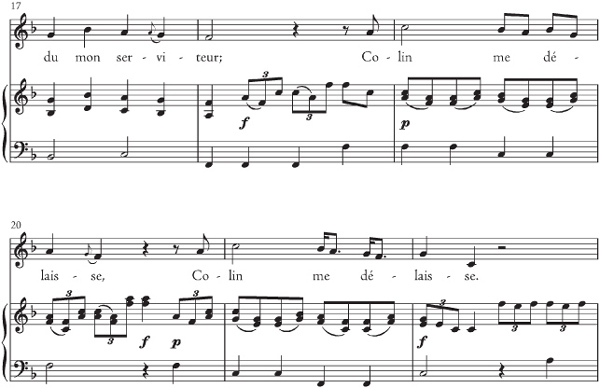

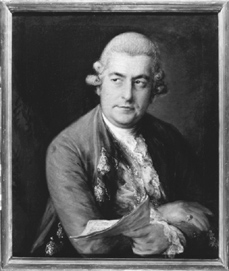

The Bach whom Mozart regarded as a musical parent was old Sebastian’s second son, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714–88), who was indeed old enough to be Mozart’s father (or even his grandfather), and who along with his much younger half-brother Johann Christian (1735–82) was indeed regarded by the musicians of the late eighteenth century as a founding father. Their eminence has much receded, though, owing to the historical circumstances that attended the rise of the modern “classical” repertory and the writing of its history. That modern repertory (we still call it “standard”) began with the works of Mozart himself and his contemporaries, notably Franz Joseph Haydn. When J. S. Bach was revived in the nineteenth century, he was appended to an already-established “canon” of works and, along with Handel, was proclaimed its founding father. The work of his sons, however, was not revived.

The false genealogy thus implied, in which the generation of Bach and Handel was cast in a direct line that led straight to the generation of Haydn and Mozart, was responsible for a host of false historical assumptions. Because of them, the interest and attention of historians was diverted away from the music and the musical life of the mid-eighteenth century, when the Bach sons, along with the later composers of opera seria (with whom we are already somewhat familiar from chapter 4) were at their height of activity and prestige. The result has been something of a historiographical black hole. The earliest attempts to plug it amounted to assertions and counterassertions that this or that repertory formed the “missing link” between the Bach–Handel and Haydn–Mozart poles. First came Hugo Riemann (1849–1919), a great German scholar who identified a once-famous but chimerical “Mannheim School” as “the so-long-sought predecessor of Haydn.”2 The Italian musicologist Fausto Torrefranca (1883–1955) found the missing link in Italian keyboard sonatas;3 the Viennese Wilhelm Fischer (1886–1962) found it in the Viennese orchestral style; and so it went.4

FIG. 8-1 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, J. S. Bach’s second son, master of the empfindsamer Stil and author of the Essay on the True Art of Keyboard Playing.

Finally, in 1969, the American music historian Daniel Heartz blew the whistle on the game in an explosive four-page wake-up call of an article (“Approaching a History of 18th-Century Music”), and made the first comprehensive attempt at a new historiography in a magisterial eight-hundred-page book published twenty-six years later (Haydn, Mozart and the Viennese School: 1740–1780).5 Heartz accounted for the notorious void by noting the fact—which many at the time found maddening to acknowledge—that the historiography of eighteenth-century music “has been done largely by, for, and about Germans.”6 But as he went right on to point out in a truly delicious passage, the Germanic historiography has affected everyone who conceives the history of eighteenth-century music in terms of the modern canon and its masters. The death of Bach in 1750, which seems so dramatically (and conveniently) to split the century into its early and late phases, Heartz observed,

has a sentimental meaning for all music lovers today. It meant nothing at the time. For all that the Leipzig master participated upon the European musical scene of his day he might as well have died a generation earlier. He did not take the extra step that made [the opera seria composer Johann Adolf ] Hasse the darling of Dresden and of Europe … and thank God for that! With Handel the case is different. Had he remained in the North we should probably honor him now no more than we do a hundred other Lutheran worthies. Italy coaxed him beyond his originally turgid and unvocal mannerisms. Had he remained to bask in Southern climes he might have joined the Neapolitan thrust into the mainstream of 18th-century music. But he went instead to Augustan England. There, musical backwater though it was, he found himself in a land that led the world with regard to the freedom and dignity of the human spirit. To England, then, we owe thanks that Handel became one of the greatest of all masters. At the same time it should be borne in mind that Handel in London stood aside from the main evolution nearly as much as Bach.

We tend nowadays to recoil a bit from phrases like “mainstream” and “main evolution,” seeing in them the likely pitfall of substituting one sort of blinkered or biased view for another. Evolutions are only “main” to the extent that their outcomes are valued. Heartz’s “main evolution” is so described because of where it led—namely, to Haydn and Mozart. Meanwhile, the fact that Bach and Handel have returned to the canon in glory, and have exerted a potent influence on composers ever since their return, shows that the evolution from which they stood apart was not permanently or irrevocably “main.” “Main-ness,” in short is not something inherent in a phenomenon but something ascribed to it—inevitably in hindsight, and for a reason. But whether or not we wish to promote the slighted evolutionary line in this way, its reality must be accepted and coped with. Otherwise we have no history, if (to quote Heartz once more) history is an attempt “to seek the interconnection between events.”

So in this chapter we will try to fill in the picture a bit, although the full story is still far from tellable. No period is in greater need of fundamental research than the period that extended from the 1730s to the 1760s: the period, in other words, in which the composers born in the first two decades of the century dominated the contemporary scene. That period, long commonly known as “Preclassic” (and thus relegated by its very name to a status of relative insignificance, a sort of trough between peaks), has been until recently the most systematically neglected span of years in the whole history of European “fine-art” music.

FIG. 8-2 Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, eldest son of J. S. Bach, who followed in his father’s footsteps as a North German church organist.

One very dramatic way of pointing up the problem and suggesting solutions to it (even though it means staying for a while with the Germans) would be to begin with a close look at the work of Bach’s sons, starting with the eldest, Wilhelm Friedemann (1710–84). We last heard of him as the arranger of his father’s huge Reformation cantata for a gala performance on the anniversary of the Augsburg Confession. Thereafter, W. F. Bach (henceforth “WF”) followed a career in his father’s footsteps as Lutheran organist and cantor. Although far less successful than old Sebastian’s in terms of steady employment, owing to what we would probably now diagnose as personality disorders, it was by no means an undistinguished career. WF’s most prominent job, and the one he held longest, was as successor to Zachow, Handel’s teacher, at the Liebfrauenkirche (Church of the Virgin Mary) in Halle, Handel’s birthplace. And despite his career difficulties, WF inherited his father’s reputation as the finest German church organist of his time.

It would be reasonable to expect his music basically to resemble old Sebastian’s. Some of it, notably his church cantatas, did. And yet as the harpsichord sonata in F (Ex. 8-1) suggests, much more of it does not.

Although composed around 1745, that is to say within J. S. Bach’s lifetime, the work occupies a different stylistic universe than anything the elder Bach composed. The very word “sonata” had come to mean something different to WF from what it meant to JS. For JS the word meant chamber music in the Italian style—basically trio sonatas, not keyboard works at all. For keyboard one wrote suites, not sonatas. The only exceptions were keyboard arrangements of chamber sonatas (like the one by Reincken we looked at in chapter 6), or else deliberate imitations of such works, like the set of six sonatas for organ composed in Leipzig around 1727, in which the two hands of the organist represent the two “melodic” parts of a trio sonata and the feet on the pedals played the very active and thematic bass. (The organ trios were thus pedal studies in effect; they were actually composed for WF to practice.) Even JS’s sonatas for solo instrument and harpsichord were usually trio sonatas, thanks to obbligato writing for the keyboard. The most common formal approach in all of these works, especially in the outer (fast) movements, was to spin them out in fugal style.

JS never dreamt of writing keyboard sonatas like WF’s (not just the one given here, but all of them), in which all three movements were in binary form and in which the texture is either two-part or else makes free use of harmonic figuration. But these large formal and textural differences, though significant, are really the least of it. The stylistic and rhetorical gulf is the mind-boggler, and it widens with each movement.

At first blush WF’s first movement does not look all that “un-Bachlike.” It actually begins with a canon. That canon, though, lasts all of two measures, and contains a repeated phrase that turns it into mere “voice exchange.” Imitative counterpoint, though clearly something at WF’s beck and call, is for him an occasional device, more a decorative touch than the essential modus operandi. But even that is not the most basic difference of approach between WF and his father. The most basic differences lie in the interpenetrating dimensions of melodic design and harmonic rhythm.

WF’s melodic design, at the opposite pole from JS’s powerfully spinning engine, is based on the dual principle of short-range contrast and balance. The first four measures tell the whole story. Both melodically and harmonically, they divide in the middle, two plus two. The first pair (our “canon”) continually circles around the tonic, touching down on it at every second beat. The second pair of measures does the same with the dominant harmony and underscores the harmonic contrast with a motivic one. Melodically, the second pair has nothing to do with the first. But the contrast is forged into a sort of higher unity by the principle of balance when the tonic is restored in m. 5.

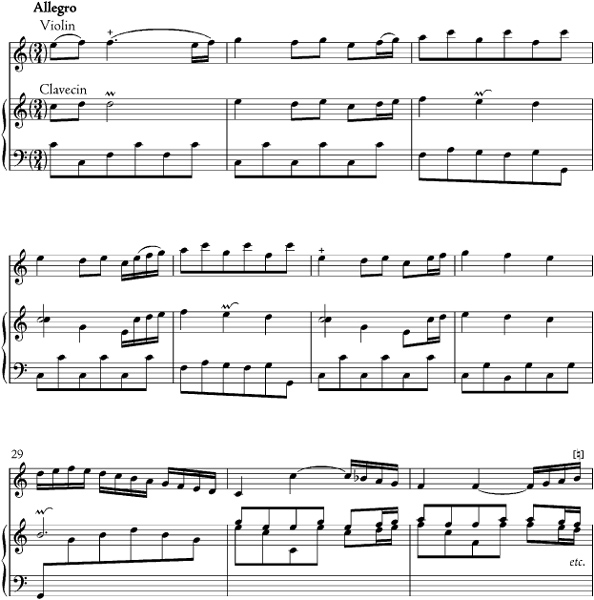

EX. 8-1 W. F. Bach, Sonata in F (Falck catalogue no. 6), first movement

Melodic contrast then seems to run rampant. The fifth measure has a new motive (based on the opening rhythm in m. 1), and so does the sixth (no longer related to anything previous), and so does the seventh! These little melodic cells qualify as “motives” through independent repetition: in m. 5 directly in the right hand, in m. 6 by a twofold exchange between the hands, and in m. 7 by a single exchange; from this perspective, too, variety seems at first to know no bounds. Measure 8 continues with the same motive as m. 7, which once again creates a symmetrical divide (that is, a divide at the middle); measures 5–8 break down into (1 + 1) + 2.

Parenthetically, let us also note that these motives are cast in rhythms that carry definite associations to the “galant”—the “affable” (lightweight, courtly, “Frenchy”) style that JS Bach tended to shy away from, even in the actual galanteries (the “modern” dances) from his suites. The fast triplets alternating freely with duple divisions are one specifically galant rhythm (exploited somewhat ironically by JS, we may recall, in the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto with its most ungallant juggernaut of a harpsichord solo). The “lombard” rhythms (quick short–long pairs) are even more distinctly galant, and even rarer in the work of Bach the father.

But all the surface variety and decorative dazzle in WF’s writing is a feint that covers, and somewhat occludes, a very deliberate and structurally symmetrical tonal plan. Like any binary movement, this one will follow a there-and-back harmonic course, moving from tonic to dominant in the first half and from dominant to tonic, by way of a “far-out point” (FOP), in the second. What distinguishes one piece from another is not the foreordained basic plan they all share but rather the specific means of its implementation. Some pieces rush headlong from harmonic pole to pole. This one, to a degree we have never before encountered in instrumental music, takes time to smell the daisies (and, in the form of unpredictably varied motives, takes care to provide a lot of daisies to smell). That placidity is also part and parcel of what it meant to be galant. It’s a bad courtier or diplomat who’ll allow strong emotion to show.

A stroll around a garden, then—and a very meticulously laid out garden it is. Taking in the first half at a glance now, we count sixteen measures—and it’s no accident. It means that the portion we have examined so far, exactly half of the total span, will be balanced by the rest, so that our observations about short-range harmonic and melodic symmetries will hold at the long range as well: 16 = (8 + 8) = (4 + 4 + 4 + 4), and so on down to pairs and units. The longest-range symmetry governing this half of the movement concerns harmonic balance. The establishment of the dominant as local tonic, or modulatory goal, takes place exactly on the downbeat of m. 9 and is repeatedly confirmed thereafter, thus dividing the whole span into 8 bars of tonic, 8 of dominant. Within the second 8 (that is, mm. 9–16), the motivic contrasts take place in a fashion that continues to emphasize symmetrical divisions on various levels simultaneously. Thus m. 9 introduces syncopes; m. 10 has exchanges of triplets between the hands; mm. 11–12 coalesce into one exchange of triplets and larger syncopes; mm. 13–14 feature a twofold exchange of motives; m. 15 has a single exchange, and m. 16 provides the cadence. Thus in summary we get (1 + 1) + 2 + 2 + (1 + 1), which adds a kind of palindromic symmetry to the mix. The ideal, far from the “Baroque” aim of generating a great motivic and tonal momentum, seems to be to provide a maximum of ingratiating detail over a satisfyingly stable ground plan.

The second half starts off like a palindrome or mirror reflection of the first. Its first four measures (mm. 17–20) are a simple transposition to the dominant of the four-measure gambit that got the whole piece moving, and that we analyzed in some detail above. In m. 21, however, we hit a big jolt, expressed at once in every possible dimension—harmonic, textural, melodic. The harmony is a diminished-seventh chord, the most dissonant chord (as opposed to contrapuntal or “non-harmonic” dissonance) in the vocabulary of the time. The texture is disrupted by it: in fact this is the first actual chord we have heard in what up to now has been a strictly two-part texture, one that implied its harmonies rather than stating them outright. Melodically, too, there is disruption: obsessive (or constrained) syncopated repetition of single tones and dissonant leaps rather than smooth melodic flow. (And there is disruption in phrase length, too, as we shall see.)

In a way this is not unexpected, since it is time to move out to the FOP. But never yet have we seen the move so dramatized. The diminished-seventh at m. 21 is built over the leading tone of vi (d minor); and when resolution is made, the opening motive, familiar from both halves of the piece, returns, only to be brusquely shunted aside by a new diminished-seventh disruption on the third beat of m. 24. This is a far more serious disruption, because it is built over D , the leading tone to E, which is the seventh degree of the scale, and the only pitch in the scale of F major that cannot function as a local tonic because it takes a diminished triad. Therefore, when resolution is made to E major in m. 26, there can be no sense of stable arrival, even at a FOP, because the harmony still contains a chromatic tone and expresses no function within the original key.

, the leading tone to E, which is the seventh degree of the scale, and the only pitch in the scale of F major that cannot function as a local tonic because it takes a diminished triad. Therefore, when resolution is made to E major in m. 26, there can be no sense of stable arrival, even at a FOP, because the harmony still contains a chromatic tone and expresses no function within the original key.

Harmonic restlessness continues through an asymmetrical (because binarily indivisible) five measures—during which, with a single exception (find it!), every degree of the chromatic scale is sounded—before settling down on A minor (iii), the true FOP. At this point, stable thematic material is resumed for two measures—literally resumed at the very point at which it had been interrupted (compare mm. 31–32 with mm. 5–6)—only to be superseded by another five bars’ restless modulation, aggravated this time by quickened syncopes, during which every degree of the chromatic scale is sounded without exception.

This last, extraordinarily chromatic, modulatory passage lets us off in m. 38 within hailing distance of the tonic—on IV, which proceeds to V, thence home. Again the return of stable harmonic functions is signaled, or accompanied, by the return of stable thematic material. The “retransitional” bar, the one that zeroes in on the tonic, brings back the “lombard” motives first heard in m. 7. When the tonic is reached in m. 39, however, the original melodic opening abruptly supersedes the lombards. This is the “double return”—original key and original theme simultaneously reachieved with mutually reinforcing or “synergistic” effect—that we first encountered, but only as an anomaly, in Domenico Scarlatti. Two bars later, in m. 41, the whole section originally cast in the dominant (mm. 7–16) returns transposed to the tonic and finishes the piece off with a sense of restored balance and fully achieved harmonic reciprocity.

In the music of W. F. Bach and his contemporaries, the double return and the large-scale melodic-recapitulation-cum-harmonic-reciprocation that it introduces are no longer anomalous features, as they had been with Scarlatti. They have become standard. Whereas Scarlatti’s use of it created a little historiographical problem (what, precisely, was its relationship—or his—to the “main evolution”?), there is no question of its absolute centrality to the musical thinking of WF’s generation and the ones that followed. Indeed, it would not be much of an exaggeration to dub the whole later eighteenth century the Age of the Double Return, so definitive did the gesture become.

The last movement of the present sonata, a rollicking Presto, offers immediate confirmation. Although it contrasts with the first movement in mood and texture, it follows the very same formal model and achieves the very same sense of roundedness and stability. Practically the whole of the first section of the piece is recapitulated in the second half. The first six measures are actually restated twice: at the very beginning of the second half, where they are transposed to the dominant, and towards the end, where they provide the double return. The middle movement (Ex. 8-2), a minuet (or a pair of minuets to be exact), is a simple galanterie such as J. S. Bach might have included in a suite. Simpler, in fact: JS would never have settled for such an uncomplicated texture, or for so much artless alternation of tonics and dominants, bar by bar, such as one finds here (especially at the beginning of the second minuet or “trio”). Yet we sense that WF is not “settling” for anything, but using the simplicity and “naturalness” of the unaffected dance as a foil for the very sophisticated constructions in the outer movements.

EX. 8-2 W. F. Bach, Sonata in F (Falck catalogue no. 6), second movement (Minuet and Trio)

By the use of this foil, the composer points up that very sophistication by reminding us that all the movements in his sonata are cast in what is basically the same form, and also showing us how much variety of surface detail and structural elaboration that basic form can accommodate. The outer movements, with their tremendous profusion of motives, their cunningly calculated harmonic jolts, and their dramatically articulated unfoldings, are teased-up versions of the old galanterie, set on either side of a basic version that provides a moment of repose.

But where did all these teasing-up devices come from? And where did WF learn them, if he did not learn them at home? Every distinctive feature of the son’s style—its melodic profligacy, its reliance on the contrast and balance of short ideas, its frequent cadences, its self-dramatizing form, its synergistic harnessing of melodic and harmonic events, even its characteristic melodic and harmonic rhythms—were absolutely antithetical to his father’s style, and to Handel’s as well. To see this style surfacing all at once in Germany explains nothing; it merely makes the problem more acute. Its apparent suddenness is but the result of our skewed perspective on it—our skewed Germanocentric perspective, as Heartz might wish to warn us.

Before trying to solve the problem, let’s savor it for a while by making it “worse.” We can expand the scope of our comparison by noting that the new “teasing” techniques not only created a stylistic contrast with the old but an esthetic and psychological one as well. A composition by J. S. Bach or one of his contemporaries was nothing if not musically unified. There is usually one main inventio or musical idea, whether (depending on the genre) we call it “subject,” “ritornello,” or by some other name, and its purpose is to project, through consistently worked out musical “figures” or motives, a single dominant affect or feeling-state, writ very large indeed.

The melodic surface of WF’s sonata, as we have seen, presents not a unified but a highly nuanced, variegated, even fragmented, exterior. The many short-term contrasts, and their implicit importance, seem to undermine the very foundations of his father’s style in both its musical and its expressive dimensions. In contrast to the inexorable consistency of JS’s “spinning-out,” the only predictable aspect of WF’s melodic unfolding is its unpredictability. In place of a heroic affect, “objectively” displayed, there is consciousness of subjective caprice, of impressionability, of quick, spontaneous responsiveness or changeability of mood—in a word, of “sensibility,” as eighteenth-century writers (most famously, Jane Austen) used the word.

The German equivalent of sensibility, in this sense, was Empfindung, meaning the thing itself, or Empfindsamkeit, meaning susceptibility to it. It was a new esthetic, which aimed not at objective depiction of a character’s feelings, as in an opera, but at the expression and transmission of one’s own; and, being based on introspection, it was “realistic” in the sense that it recognized the skittishness and fluidity of subjective feeling. “The rapidity with which the emotions change is common knowledge, for they are nothing but motion and restlessness,” wrote the Berlin composer Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1718–95) in a famous treatise on music criticism.7

Yet while that rapidity was presumably as well known to the composers of theatrical and ecclesiastical music as it was to anyone else, it was not thought by them to be the most appropriate aspect of the emotions for musical imitation. Rather, they sought to isolate, magnify, and “objectify” the idealized moods of gods, heroes, or contemplative Christian souls at superhuman intensity, and use that objective magnification as the basis for creating monumental musical structures that would impress large audiences in theaters and churches. Composers of the empfindsamer Stil, composing on a much smaller scale for intimate domestic surroundings, sought to capture the way “real people” really felt. They sought to create an impression of self-portraiture in which the player (and purchaser) of their music would recognize a corresponding self-portrait.

The origins of artistic “sensibility” were literary. Its first great conscious exponent was the poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724–1803), who established the style with his odes (love poems) in the 1740s, and who lived in Hamburg beginning in 1770. The Hamburg connection is important to us because Klopstock’s neighbor there was Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (henceforth “CPE”), who in 1768 assumed the post of cantor at the so-called Johanneum (Church of St. John) after almost thirty years of service to the court of Frederick the Great, the King of Prussia, in Berlin and at the other royal residences. He and Klopstock were kindred spirits and quickly became friends. CPE set Klopstock’s odes to music and carried on a lively and sympathetic correspondence with him about the relationship of music and poetry. He was in effect a musical Klopstock and the chief representative in his own medium of artistic Empfindsamkeit. The term is now firmly, if retrospectively, associated with him, and with his keyboard music in particular. He took to an extreme the kind of wordless “expressionism” we have already noted in the work of his elder brother.

He did it quite consciously and even wrote about it (though without using the actual E-word) in his famous treatise, An Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments (Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen), published in Berlin in two volumes (1753, 1762). (It was to this book that Mozart was supposedly paying tribute in the comment quoted at the beginning of this chapter.) CPE’s Essay is of course full of technical information—about ornamentation, for example, and continuo realization—that is of great value to the historian of performance practice. But it also deals in less tangible matters, and that is what was new about it.

“Play from the soul,” CPE exhorted his readers, “not like a trained bird!”8 And then, lending his novel idea authority by casting it as a paraphrase of a famous maxim by the Roman poet Horace:

Since a musician cannot move others unless he himself is moved, he must of necessity feel all of the affects that he hopes to arouse in his listeners. He communicates his own feelings to them and thus most effectively moves them to sympathy. In languishing, sad passages, the performer must languish and grow sad. … Similarly, in lively, joyous passages, the executant must again put himself into the appropriate mood. And so, constantly varying the passions he will barely quiet one before he rouses another.9

FIG. 8-3 Frederick the Great performing as flute soloist (probably in his own concerto) at a soirée in Sans Souci, his pleasure palace at Potsdam. His music master, Johann Joachim Quantz, watches from the left foreground. C. P. E. Bach is at the keyboard; leading the violins is Franticek Benda, a member of a large family of distinguished Bohemian musicians active in Germany, who spent fifty-three years in Frederick’s service. Oil painting (1852) by Adolf Friedrich Erdmann von Menzel.

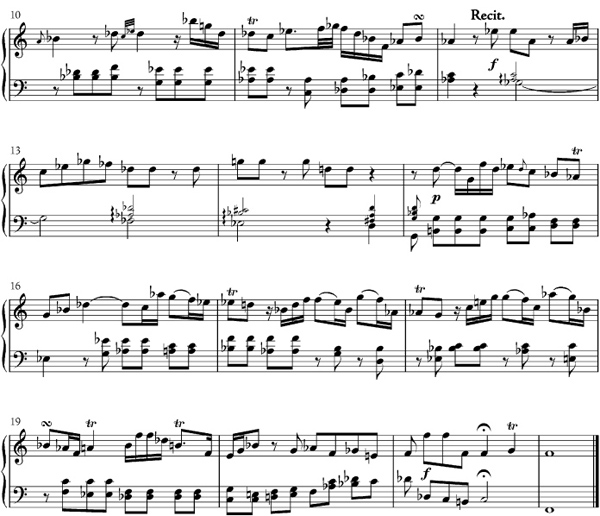

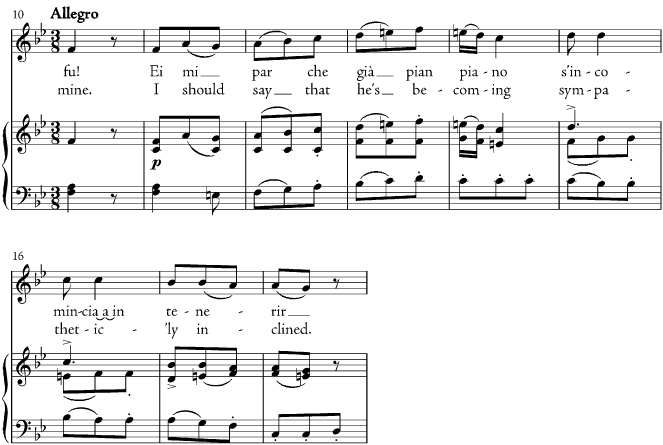

Although the author takes the point for granted, it is important for us to realize that he is describing not only a style of performance but a style of composition as well. The kind of mercurial changeability of mood he emphasizes, and the impetuous sincerity he demands of the player, would both be out of place in a work by his father or in a formalized aria by Handel. For practical examples of musical Empfindsamkeit we must turn to CPE’s own works, like the Sonata in F (Ex. 8-3), chosen for the sake of its outward similarity to WF’s sonata in the same key.

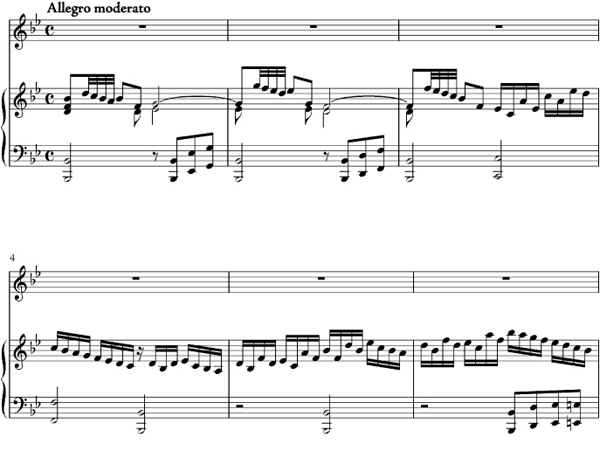

EX. 8-3A C. P. E. Bach, “Prussian” Sonata no. 1 in F (Wotquenne catalogue no. 48/1), first movement, mm. 1–4, 32–37

EX. 8-3B C. P. E. Bach, “Prussian” Sonata no. 1 in F (Wotquenne catalogue no. 48/1), second movement

This sonata is the first in a set of six, composed in Berlin between 1740 and 1742, as much as a decade before the death of J. S. Bach, and published with a dedication to Frederick the Great, for which reason they are called the “Prussian” sonatas. In style and texture the first movement is even simpler than WF’s sonata and even more mercurial. The second half, for example, does not begin with a direct reference to the opening material but rather a fascinatingly oblique one. The first measure is a kind of free inversion of its counterpart; the left hand enters the way it did in the first half, but there is a new countermelody above it in the right, and so on (Ex. 8-3a). Thus when the double return comes, it is the first time the opening melody has been heard in anything like its original form since the beginning of the piece.

The magic movement, however, is the second (Andante). There is nothing like it in WF’s sonata, and nothing remotely like it in the works of J. S. Bach. It is the kind of piece for which the term empfindsamer Stil was coined. The key is F minor, traditionally a key of tortured moods. But no key signature is used—not because the key is in any way unreal, but because the very wayward harmonic digressions from it would entail a lot of tedious cancellations of accidentals. Even before the digressions take place the harmonic writing is boldly “subjective” and capricious: in m. 2, for example, a sigh figure is immediately followed by a leap of a diminished octave.

After the half cadence in m. 3 the melody breaks off altogether in favor of something that at first seems a contradiction in terms: an explicitly labeled instrumental recitative! Even without the label, the texture and the nature of the melodic writing would have labeled it conclusively. The giveaways are the pairs of repeated eighth notes on the first three downbeats, representing the prosody of “feminine endings” (line-endings in which the last syllable is unaccented). A knowing performer would recognize the notational conventions of opera here and perform them like a singer, interpolating an accented passing tone (or “prosodic appoggiatura”) in place of the first eighth as indicated in the score.

The recourse here to a patently operatic style—and the style associated in opera with “speaking,” at that—suggests that the empfindsamer Stil communicates, as it were, an unwritten or unspoken text. An operatic recitative (or scena, to cite the type of scene in which recitative alternates, as it does in CPE’s sonata, with a rhythmically steady melody) is traditionally a “formless” style of music that follows the shape of its text—in this case its unwritten text. Without an actual text to set, the music comes, as CPE puts it in his treatise, directly “from the soul,” and communicates, inchoately and pressingly, an Empfindung that transcends the limiting medium of words.

Thus instrumental recitative, the signature device of musical Empfindsamkeit, implies a direct address from the composer to the listener, who is taken into the composer’s confidence, as it were, and confided in person to person. The impression created is that of an individual intimately addressing a peer—and CPE’s favorite instrument for creating such an impression was the clavichord, an instrument capable of dynamic gradations unavailable on the harpsichord, but so soft that one has to be as near the performer in order to hear it as one would have to be in order to carry on a private conversation.

Also inchoate and pressing are the harmonies that support this wordless recitative—chromatic harmonies that deliberately depart from the model sequences of “normal” music and, if anything, recall the vagaries of the latest, most “decadent” madrigals. If a G natural is interpolated as a prosodic appoggiatura in m. 8, then the first recitative section (like WF’s already rather empfindsamer modulations in the first movement of his sonata) contains every degree of the chromatic scale. While the wildest, most disruptive touch is surely the immediate progression of the  chord of B

chord of B in m. 4 to the vii°

in m. 4 to the vii° of B in the next measure, surely the most sophisticated progression is the enharmonic succession in mm. 7–8, whereby G

of B in the next measure, surely the most sophisticated progression is the enharmonic succession in mm. 7–8, whereby G is transformed to A

is transformed to A , reversing its tendency and smoothly restoring the original key.

, reversing its tendency and smoothly restoring the original key.

CPE would not have called this style of his madrigalian, of course; nor, as already observed, did he himself use the word empfindsamer to describe it. His term for this inchoate, pressing idiom, with its rhythmic indefiniteness and harmonic waywardness, was the “fantasia” style. It was a style more often improvised than actually composed, as he tells us in his Essay, giving us a helpful reminder that the written music on which we base our historiography was still—is always—just the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, the vogue for Empfindsamkeit lent improvisation a new prestige, CPE strongly implying that the ability to improvise is the sine qua non of true musical talent: “It is quite possible for a person to have studied composition with good success and to have turned his pen to fine ends without his having any gift for improvisation. But, on the other hand, a good future in composition can be assuredly predicted for anyone who can improvise, provided that he writes profusely and does not start too late.”10

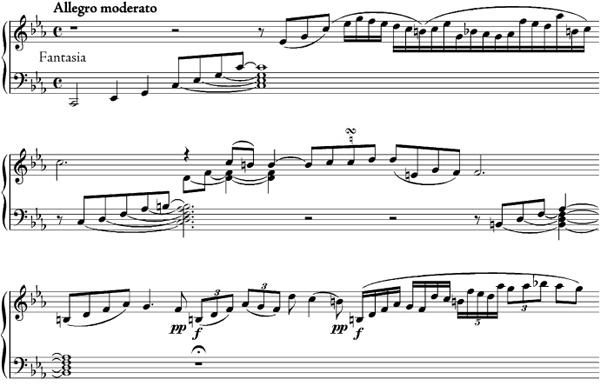

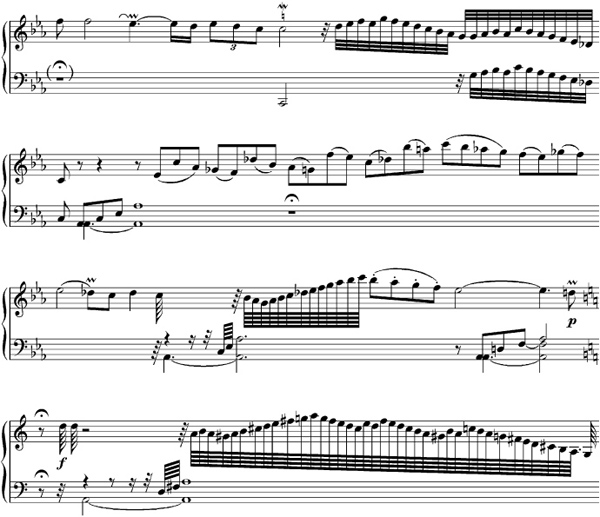

A fantasia, then, might be characterized as a transcribed improvisation. J. S. Bach, a master improviser, wrote down only a few, notably a famous “Chromatic fantasia and fugue” inDminor. For hima fantasia was the equivalent of a prelude—not a fully viable piece in its own right but an introduction to a strict composition. CPE wrote down many more, especially in his later years, and was inclined, in the spirit of Empfindsamkeit, to regard them as freestanding, complete compositions.His most famous fantasia is the one in C minor, which he published as a Probestück, or “lesson piece,” to illustrate the Essay in 1753. Its beginning is shown in Ex. 8-4. Its many dynamic indications show it to have been conceived specifically in terms of the clavichord or the pianoforte, which was just then coming into widespread use.

The recitative style is again invoked at the outset, but a recitative sung by a supersinger with a multioctave range. There is a purely conventional signature denoting “common time,” but there are no bars and hence no measures to count, signaling (according to CPE’s instructions in the Essay) a restlessly fluctuating tempo. Approximately halfway through the piece, however, a time signature of  will supersede the original signature, bars will be measured out so that the new tempo (Largo) is to be strictly maintained, and what amounts to an “arioso” will temporarily succeed the recitative. Here the power of dynamics to delineate quick emotional changes comes into its own; rapid-fire alternations of fortissimo and piano, with the fortissimos on the off-beats, amount to virtual palpitations. Once again, by casting the fantasia in a recognizable vocal form and employing an idiom that apes the nuances of passionate singing, an imaginary text is suggested, of which the music is the intensified expression, faithfully and “truthfully” tracking every fugitive shade of meaning and feeling.

will supersede the original signature, bars will be measured out so that the new tempo (Largo) is to be strictly maintained, and what amounts to an “arioso” will temporarily succeed the recitative. Here the power of dynamics to delineate quick emotional changes comes into its own; rapid-fire alternations of fortissimo and piano, with the fortissimos on the off-beats, amount to virtual palpitations. Once again, by casting the fantasia in a recognizable vocal form and employing an idiom that apes the nuances of passionate singing, an imaginary text is suggested, of which the music is the intensified expression, faithfully and “truthfully” tracking every fugitive shade of meaning and feeling.

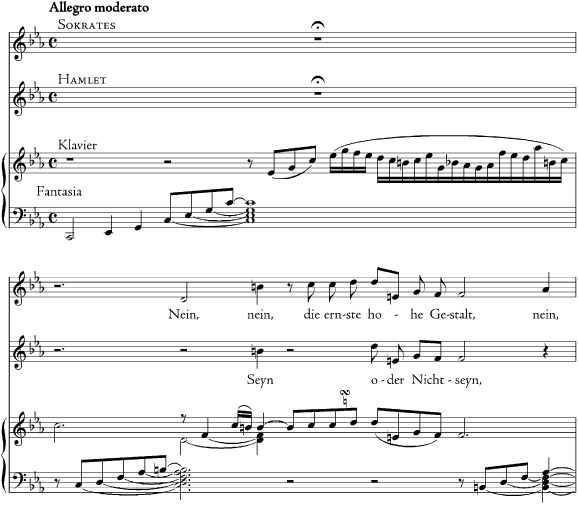

EX. 8-4 C. P. E. Bach, Fantasia in C minor

So clearly does “empfindsamer” instrumental music aspire to the condition of speech-song in its emotional immediacy, and so convincingly does this fantasia conjure up an imaginary or internal theater, that in 1767 the poet Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg (1727–1823), a close friend of Klopstock and an acquaintance of the composer, was moved to furnish the fantasia with not one but two vocal lines that mainly doubled what was singable in the right-hand figuration. The first is fitted to a German translation of Socrates’s speech before committing forced suicide in Plato’s dialogue Phaedo; the second carries a paraphrase in fevered doggerel of the celebrated suicide soliloquy (“To be or not to be …”) from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. These texts, the most searingly emotional outpourings Gerstenberg could find in all of literature, are overlaid to the beginning of the fantasia in Ex. 8-5. The Shakespearean travesty runs as follows:

Invoking Shakespeare was a particularly pointed commentary on the empfindsamer Stil. Gerstenberg was a leader in the so-called Sturm und Drang (“Storm and stress”) movement, a loose literary association that sought to exalt spontaneous subjectivity and unrestrained “genius” over accepted rules and standards of art. Shakespeare (discovered by the Germans in the 1760s, in translations by the poet Christoph Martin Wieland) was their hero, worshiped and emulated for the way in which his plays “freely” mixed prose and poetry, tragedy and comedy, elevated and lowly characters and diction in a manner that—compared to the “neoclassical” style of the French theater or the Metastasian opera seria—seemed to subvert all restraints in the name of unmediated passionate expression.

A style that combined the declamatory freedom of recitative with the concentrated expressivity of the new instrumental music and the semantic specificity of words would synthesize, and hence surpass, all previous achievements in drama and music, thought Gerstenberg. He certainly implied as much when describing his Shakespearean adaptation of CPE’s fantasia in a letter to a friend:

I assume, first, that music without words expresses only general ideas, and that the addition of words brings out its full meaning. … On this basis I have underlaid a kind of text to some Bach keyboard pieces which were obviously never intended to involve a singing voice, but Klopstock and everybody have told me that these would be the most expressive pieces for singing that could be heard. Under the fantasy in the Essay, for example, I put Hamlet’s monologue as he fantasizes on life and death. A kind of middle condition of his shuddering soul is conveyed.11

And Carl Friedrich Cramer, a professor of classics who edited a music magazine where he published Gerstenberg’s experiment in 1787, described it to his readers in terms that capture the very essence of Sturm und Drang, and that may even remind us of the theorizing that had attended the birth of opera two centuries before:

I believe that this eccentric essay belongs among the most important innovations that have ever been conceived by a connoisseur, and that to a thinking artist, one who does not always cringe in slavery to tradition, it may be a divining rod for discovering many deep veins of gold in the secret mines of music, in that it demonstrates in itself what can result from this dithyrambic union of instrumental and vocal music: an effect quite different from the customarily confined possibilities of self-willed forms and rhythms.12

EX. 8-5 C. P. E. Bach, Fantasia in C minor with Shakespeare text overlaid by Gerstenberg

But in an important and quite obvious sense both Gerstenberg and Cramer had missed the point. CPE Bach’s intention, in creating his empfindsamer Stil, was not to express texts, however finely. For doing that, needless to say, there was plenty of precedent. Rather, his aim was to transcend texts—that is, to achieve a level of pure expressivity that language, bound as it was to semantic specifics, could never reach. This transcendently expressive music of which CPE was the fully self-conscious harbinger was later dubbed “absolute” music. It marked the first time that instrumental music was deemed to have decisively surpassed vocal music in spiritual content, and to be consequently more valuable as art.

And yet, to compound the paradox, the means by which the new instrumental music would transcend the vocal were nevertheless all borrowed from the vocal. To Gerstenberg himself, CPE once wrote that “the human voice remains preeminent”13 as an expressive medium, and in his Essay he advises keyboard players to “miss no opportunity of hearing capable singers,” for “from this one learns to think in terms of song.”14 Only thus can one translate one’s ever fleeting, ever changing feelings into tones. And here at last we begin to get an inkling into the source of the tremendous metamorphosis in musical style and esthetics that took place over the course of the eighteenth century, ineluctably transforming the work of the Bach sons, along with everyone else’s, and ineluctably opening up a gaping generation gap. The ferment was caused by opera. That was the “main evolution” to which Daniel Heartz drew attention.

But if the empfindsamer Stil was the most obviously and consciously “operatic” instrumental style of the period (taking “operatic” figuratively to mean intensely passionate and grandly eloquent), it was rather one-sidedly so. It placed emphasis on the formally unstable aspects of opera, particularly on recitative—musical “speech.” (That is what can make it seem a throwback to the earliest days of opera, the days of the seconda prattica and the stile rappresentativo.) It was a kind of dramatic music that, as it happened, was practiced exclusively by composers who never wrote operas.

To see another side—a more direct and “purely musical” side—of opera’s stylistic impact on instrumental music, we need to examine the work of a composer who wrote both operas and sonatas. And that means examining the work of one more son of JS Bach—the youngest one, Johann (or John) Christian (1735–82, henceforth “JC”), the half brother of WF and CPE, who by the end of his life was far and away the most famous of the eighteenth-century Bachs.

Unlike his elder brothers, and as we may remember from chapter 4, JC followed a career completely at variance with his father’s. In some ways, in fact, it resembled Handel’s—in its restlessness, in its worldliness, and even in its geographical trajectory. His main teacher was his half brother CPE, with whom he went to live in Berlin after their father’s death. In 1755, aged nineteen, he made the fateful trip to Italy. He took some additional instruction in Bologna from Giovanni Battista Martini (known as “Padre Martini”), a priest who was also a legendary music pedagogue; he found himself a patron in a Milanese count; and in 1760 he became an organist at Milan Cathedral, having first converted to Catholicism in order to qualify for the job. During the same year he wrote his first opera seria, Artaserse, to Metastasio’s libretto (see chapter 4). From there he was summoned to Naples, the very nerve center of the opera seria, and in 1762 received an invitation to compose for the King’s Theatre in London, Handel’s old stamping ground.

FIG. 8-4 Portrait of J. C. Bach by Thomas Gainsborough.

Just as in Handel’s day, music in London was to a larger extent than anywhere else a public, commercial affair. JC’s career followed the ups and downs of the market. Squeezed out of the opera scene for a while by a jealous rival, he got himself appointed music master to Queen Charlotte, the German-born wife of King George III. Not only did this gain him a royal stipend, it also gave him a privilege to publish his works. The most lucrative prospects for printed music lay in keyboard and chamber music for domestic use (“such as ladies can execute with little trouble,” to quote Dr. Burney, an admiring friend of the composer).15

In another entrepreneurial venture, JC joined forces with Carl Friedrich Abel, a composer and viola da gamba virtuoso whose father had been the gambist at the Cöthen court during J. S. Bach’s tenure as music director there, and who was also by chance living in London. Together they founded the British capital’s most successful concert series, the “Bach-Abel Concerts,” which lasted until JC’s death. At the same time he maintained his ties with the opera stage—ties as much personal as professional, since he married an Italian soprano, Cecilia Grassi, the prima donna at the King’s Theatre. His fame brought operatic commissions from the continent—notably from the famously musical court at Mannheim, in the Rhineland, and even from Paris, where he set some ancient librettos that had previously served Lully.

All in all, John Christian Bach was the most versatile—and for a while, the most fashionable—composer of his generation, turning out music in every contemporary medium and for every possible outlet. Like Handel, he could boast of being a self-made man. But unlike Handel, he did not die a wealthy one. His last years were marked by several reverses in fortune and the declining popularity of his music. He died so deeply in debt that it took the queen’s intervention to get him decently buried and enable his widow to return home to Italy.

FIG. 8-5 Portrait of Carl Friedrich Abel by Thomas Gainsborough.

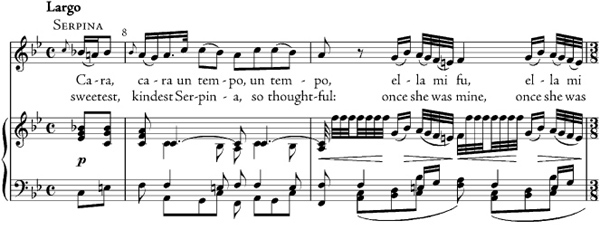

John Christian Bach’s first set of six keyboard sonatas was his opus 5 (“for the Piano Forte or Harpsichord” as the title page stipulates), printed in London in 1768. The second item in the set, sampled in Ex. 8-6, is in D major, a brilliant orchestral key in which strings and brass alike were at their most naturally resonant. The sonata catches a bit of that brilliance. It sounds like a transcribed orchestral piece—more specifically, like a transcribed operatic overture of a kind JC had composed by then in quantity. (It was literally child’s play for the fifteen-year-old Mozart, already an experienced composer—and who had already met John Christian Bach in London during one of his early concert tours as an infant prodigy—to “restore” the sonata to full orchestral dress a few years later in the guise of a piano concerto.)

In style the sonata is in the purest “galant” idiom, witty and ingratiating. The balanced phrases and short-range contrasts that we have observed in the sonatas of JC’s half brothers have become even more pronounced, to the point where they were regarded as J. C. Bach’s personal signature. “Bach seems to have been the first composer who observed the law of contrast as a principle,” wrote Dr. Burney in his History, exaggerating only slightly.16 “Before his time, contrast there frequently was, in the works of others, but it seems to have been merely accidental,” he went on (exaggerating a bit more, perhaps, in his enthusiasm), whereas Bach “seldom failed, after a rapid and noisy passage to introduce one that was slow and soothing.”

And so it certainly is at the outset of JC’s first movement (Ex. 8-6): two bars of loud chordal fanfare followed immediately by two bars of soft continuous music, followed next by a balancing repetition of the whole four-bar complex. Contrast and balance operate in other dimensions as well: the loud bars describe an octave’s descent, for example, while the soft ones describe an octave’s ascent; the loud bars are confined to the tonic harmony, for another example, while the soft ones intermix tonic and dominant. Meanwhile the texture is the work of a composer who seems (despite his surname) never to have heard of counterpoint. It is, throughout and in many different (contrasting) ways, the kind of texture we nowadays call “homophonic,” consisting of a well-defined melody against an equally well-defined accompaniment.

In overall form the sonata meets what by now must be our expectation: all three movements are binary structures. But the ways in which that same “there and back” structure is delineated differ very tellingly each time. The first movement, by far the longest, manages to cram a huge amount of finely contrasted and balanced material into its generous yet orderly unfolding. How that orderliness is achieved despite that abundance is the fascinating thing to observe. It is what made J. C. Bach the greatly influential figure that he was. Notwithstanding all appearances of profligacy, the movement is a study in economy and efficiency.

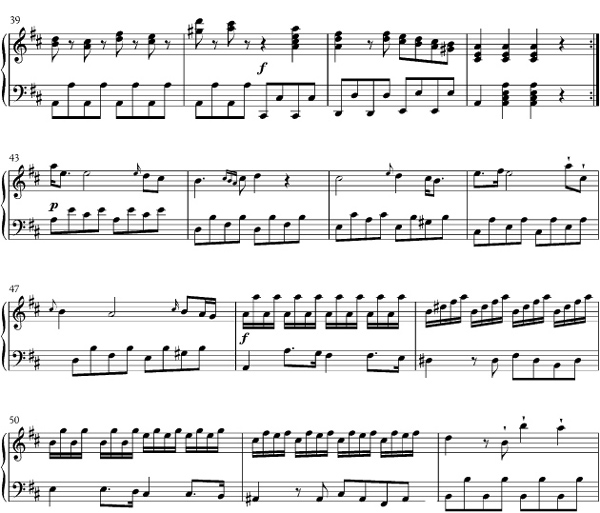

EX. 8-6 J. C. Bach, Sonata in D, Op. 5, no. 2

The arresting fanfare idea heard at the outset, for example, is heard only once again (not counting its “automatic” repetition as part of the unwritten sectional repeat)—namely, at the “double return” (m. 73). Despite its small share of the movement’s running time, its strategic placement lends it an enormous structural importance, for it serves both to launch the movement’s harmonic trajectory and to signal its completion. It thus plays the defining role in articulating a musical form that is equally the product of thematic and harmonic processes. The shape of the movement depends on our recognition of significant melodic and harmonic goals, and on our noticing their achievement. The “fanfare” theme is there to facilitate that recognition, and that makes it the movement’s mainspring.

A similar functional efficiency characterizes all the other themes and melodic ideas in the movement. It is as if the older motivic (and “affective”) prodigality we noticed and admired in the work of JC’s brother WF—short-range contrast as its own reward—had been sorted and organized by JC into a higher and more energetic unity by assigning roles to each component. Thus the new idea—arpeggios in the left hand accompanied by tremolandos in the right—that follows at m. 9 introduces an unbroken span that lasts an asymmetrical ten bars until the next silent beat or caesura, and that seems to have as its assigned task the progressive introduction of new leading tones (first G , then D

, then D ) along the circle of fifths so as to accomplish the “there” of the “there and back” on which all binary forms depend. On its completion, it is the quarter rest or caesura (a term borrowed from poetry, where it means an empty foot) that serves to mark the arrival at the new tonic, A, in m. 19. Silence plays as important a role in articulating the form of a piece like this as the notes ever do.

) along the circle of fifths so as to accomplish the “there” of the “there and back” on which all binary forms depend. On its completion, it is the quarter rest or caesura (a term borrowed from poetry, where it means an empty foot) that serves to mark the arrival at the new tonic, A, in m. 19. Silence plays as important a role in articulating the form of a piece like this as the notes ever do.

We have seen this “modulatory” maneuver countless times by now, in arias, concertos, suites, and sonatas; but we have never before seen anyone make such a look-Ma-I’m-modulating production of it as here. From this point (m. 19)to the double bar, the music is stably in the key of A major. Stable tonality implies stable (that is, symmetrical) phrase structures, and so we are not surprised to find at this point a new, full-blown melody—the longest self-contained musical “section” in the piece so far—whose tuneful abundance is artfully organized into balanced “antecedent” and “consequent” phrases.

Its opening section, four bars ending with a caesura at m. 22, can be broken down into two sequential halves, the first ending with a piquant “lombard” rhythm, the second with a half cadence (i.e., a cadence on the dominant). Phrases ending on the dominant, requiring continuation, are “antecedents”; their balancing “consequents,” as here, often begin like repetitions (compare the beginnings of m. 19 and m. 23), creating “parallel periods.” The four balancing bars (mm. 23–26) also end with a half cadence, requiring yet another phrase to reach the (local) tonic.

This requirement is met—or (alternatively) this function is supplied; or (yet another way of putting it) this role is played—by a new eight-bar phrase (mm. 27–34), itself full of contrasts and balances, to balance the first. Its first four bars consist of two quick (one-measure) upward sweeps balanced by a slow (two-measure) undulating descent. The concluding four, which also break down into 1 + 1 + 2, finally bring back the A-major triad in root position, which alone can mark a “closure.” From here on it’s confirmation all the way: a pair of contrasting two-bar phrases, immediately repeated for a total of eight measures, that regularly reapproach the (local) tonic, reinforcing the sense of arrival and, finally, of closure (for which purpose a witty reference is made to the opening chordal idea).

To sum up the contents of the first half of the movement: it does what all such binary openings do, but does it in a newly dramatic and functionally differentiated way. Four main melodic/harmonic “areas” can be distinguished, which contrast and balance one another just as they are themselves made up of internal contrasts and balances:

1. The first eight measures, in which the tonic and dominant of the main key are introduced and alternated, provide the harmonic launching pad.

2. The next ten measures (asymmetrically divided 7 + 3) accomplish a “bridging” or “modulatory” function; the fact that their purpose is basically connective is equally apparent from their harmonic instability and from their melodic asymmetry. The two factors are always interdependent.

3. The next sixteen measures reestablish harmonic stability (in a new area) and melodic symmetry: the first eight are a parallel period that ends on a half cadence. They are balanced by eight bars ending on a full cadence.

4. The last eight measures, which contrast two-by-two and balance four-by-four, confirm arrival and effect closure. Now it is time to come “back” via the FOP. Again the familiar process unfolds through a remarkable diversity of material, but an equally remarkable functional organization.

The first thing heard after the double bar is a new melody(m. 43) over a characteristic arpeggiated accompaniment (three-note chords broken low-high-middle-high) that has been known ever since the eighteenth century as the “Alberti bass” after Domenico Alberti (d. 1746), an Italian composer who famously abused it. At first the new tune seems to be a stable melody in the dominant, but it makes its cadence after a telltale five measures, and its lack of symmetry is enhanced by the way the expected caesura is elided at its conclusion. Another obviously “modulatory” phrase of four bars impinges at that moment (“obviously” modulatory because it is modeled on the bridging material from the first half). It leads through a bass A to an eight-bar melody (m. 52) consisting of a loud four-bar phrase and its echo that fully establishes a cadence on B minor (vi), the expected FOP.

to an eight-bar melody (m. 52) consisting of a loud four-bar phrase and its echo that fully establishes a cadence on B minor (vi), the expected FOP.

And just as a four-bar bridge and a brief but full-blown symmetrical melody had led away from the dominant to the FOP, the same melodic complex leads from the FOP to the “double return.” Note particularly how A, the dominant pitch, is sustained as a pedal through the whole eight-bar melody (mm. 65–73) that immediately precedes the return, creating a harmonic tension demanding especial relief. The double return palpably impends, creating the kind of suspense we associate with drama. Once again we may say that a familiar form is being newly “dramatized.”

From the double return to the end of the movement, the music consists entirely of material introduced in the first half. Indeed, except for the shrinking of the bridge material (since it is no longer needed for modulatory purposes), the music is a veritable replay of the first half, with all the tunes stably confined to the tonic key, thus creating a sense of structural balance, of melodic invention governed by harmonic function, at the very longest possible range.

What we have just traced could be described, then, as a “maximized” binary form, in which harmonic departures and arrivals are dramatized and elaborated by drawing on a seemingly inexhaustible melodic well. The melodies draw on a common fund of figures and turns: note, for example, how the “new” material immediately after the double bar employs a skipping “lombard” heard previously (compare m. 20 with m. 43). But the dominant impression is one of maximum variety of material organized by the overriding harmonic motion into a maximum unity of concept.

The remaining movements of the sonata, like most sonata movements of the “Bach’s sons” generation, are also cast in binary form—but not in the “maximized” version that gives the first movement (like most first movements, beginning with J. C. Bach) its special preeminent character. The second movement reverts to a procedure much closer to that of Bach the Father: the two halves closely mirror one another melodically as they trace the customary tonal progression, beginning and ending similarly though with reversed harmonic poles, and differing chiefly in the middle, where the second half makes its customary deflection toward the FOP—no actual cadence this time but just a chromatic color: an augmented-sixth harmony over  VI (E-flat).

VI (E-flat).

The last movement, while also cast in a seemingly familiar traditional form—a pair of minuets (old-style galanteries), the second (marked “Minore”) in the parallel minor—actually displays an interestingly novel feature. Like the first movement (and unlike any actual binary dance movement we have as yet encountered) both minuets sport “double returns” in their second halves. The functional association of theme with key has truly become a standard form-defining feature. Another feature that has (or will shortly) become standard is the substitution of III (the so-called relative major) as opposite harmonic pole for pieces in the minor mode, such as the second minuet.

Although it is notoriously easy to overdraw such matters, comparison of the sonata by C. P. E. Bach with that of his younger half brother shows up the two complementary sides of what might be called the “bourgeois” or “domestic” music of the mid-eighteenth century. Stylistically and formally they are similar enough, but “attitudinally” they contrast markedly. CPE’s is solitary, introspective, “inner-directed” music; JC’s is sociable, outgoing. The one explores personal, private, even unexpressed feelings; we easily imagine it performed for an audience of one (or even none but the player, seated at the clavichord), late at night, in a mood of emotional self-absorption. It implies a surrounding hush. The other is party music, implying bright lights, company, a surrounding hubbub of conversation. That about sums up the difference between Empfindung and galanterie, and it is no accident that the one word is German and the other French.

FIG. 8-6 “French concert” (actually a salon). Engraving by Duclos after a painting by St.-Aubin.

It was the spirit of galanterie—conviviality, pleasant “causerie” (another French word in international use)—that gave rise to what we now call chamber music in its modern sense. The first pieces of this kind, in fact, grew directly out of the keyboard sonata, and it happened first in France. The earliest composers to attempt the transformation of keyboard sonatas into sociable ensembles were a couple of forgotten Parisian violinists: Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville (1711–72) and Louis-Gabriel Guillemain (1705–70).

FIG. 8-7 Jean-Joseph Cassanea de Mondonville, by Maurice Quentin de la Tour.

Their inclinations are well illustrated by the titles of Guillemain’s sonata sets: Premier amusement à la mode (op. 8, 1740), for example, or Six sonates en quators ou conversations galantes et amusantes (op. 12, 1743). (In light of these titles, it is irresistible to mention that, in the words of the sonata-historian William S. Newman, Guillemain was “a neurotic, alcoholic misanthrope, who could not bring himself to perform in public, squandered his better-than-average earnings, and finally took his own life.”17 In this case, anyway, the style was not the man.) These were still old-fashioned continuo pieces, but as early as 1734 Mondonville—whose wife Anne Jeanne Boucon was a well-known harpsichordist who had studied with Rameau—took a decisive and much-imitated step in the name of galanterie that completely reversed the textural perspective. He published as his opus 3 a set of Pièces de clavecin en sonates avec accompagnement de violon, “harpsichord pieces grouped into sonatas, accompanied by a violin.” What he offered merely as a piquant novelty quickly took root as a new musical genre. By the 1760s it had turned into a craze that finally marked curtains for the basso continuo style.

The “accompanied keyboard sonata” initiated by Mondonville was (in theory, at least) a fully composed, self-sufficient keyboard sonata to which an obbligato for the violin or flute could be added ad libitum. In theory this was something that could be done to any keyboard sonata, and there is evidence that accompanied sonatas existed for some time as a “performance practice” before the first expressly composed specimens saw the light. Indeed, we have already seen an instance—Couperin’s “Le rossignol-en-amour” (EX. 6-12)—where a composer explicitly suggested turning one of his keyboard pieces into an ensemble piece by giving its melody part to a flute.

In practice, from the very earliest composed specimens, the “accompanying” part added something indispensable to the texture, turning the piece into a true duo, to which a cello or viol could be added to double and lightly embellish the bass line, making a trio. Unlike Guillemain’s continuo pieces, the result was a “conversation galante et amusante” for truly equal conversational partners, each with a melodic life of its own. As the excerpt in Ex. 8-7 from the minuet in Mondonville’s fourth accompanied sonata shows, even at this early stage the texture is quite different from that of J. S. Bach’s trio sonatas with obbligato harpsichord. There is no imitative polyphony, for one thing; the bass figuration shows Alberti-ish tendencies, for another; and for a third (possibly most crucial) thing, the texture is not so clearly laid out in contrapuntal “voices.” The two hands of the harpsichord frequently combine in parallel motion to become a single “voice,” and the violin (especially at such moments) is apt to dip beneath and take over the “bass.”

Mondonville’s earliest imitators were Rameau, his musical father-in-law (whose 1741 collection of Pièces de clavecin en concert for harpsichord solo and two obbligato parts contains a sarabande called “La Boucon,” dedicated to Mondonville’s wife), and Guillemain, who published a collection exactly modeled on Mondonville’s, and identically titled, in 1745.

By the 1760s, accompanied keyboard sonatas were being written everywhere, and J. C. Bach and his London cohort Abel had become preeminent in the genre, of all musical forms and media the most quintessentially galant. In fact, JC published exactly twice as many accompanied keyboard sonatas (forty-eight) as unaccompanied ones, which gives an idea of the genre’s quick ascendancy, a rise that testifies above all to its social utility. Even CPE was moved to try his hand at this profitable genre, but half-heartedly; according to a famous quip of JC’s (like all such reported comments, possibly apocryphal), “my brother lives to compose and I compose to live.”18 It would be hard to come up with a better encapsulation of Empfindsamkeit vis-à-vis galanterie!

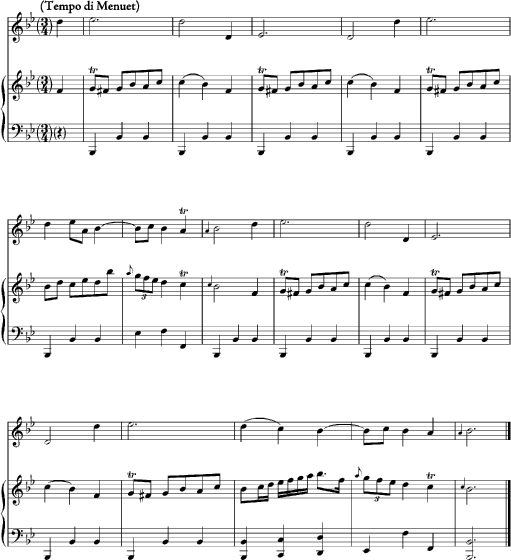

EX. 8-7 Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville, Accompanied Sonata in C, Op. 3, no. 4

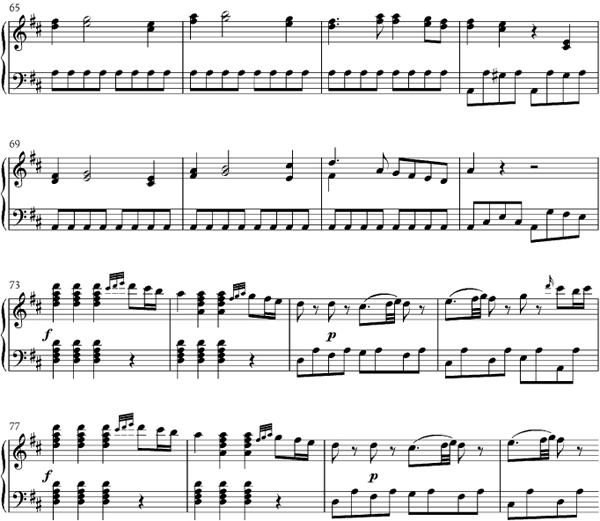

For a last mid-century sonata let us turn to the fourth item in Abel’s opus 2, a set of Six Sonatas for the Harpsichord with Accompaniments for a Violin or German [i.e., transverse or modern] Flute and Violoncello, published in London (with a dedication to the Earl of Buckinghamshire) in 1760. The style will be familiar from JC’s sonata, but the piece is shorter, simpler, more schematic. There are only two movements, a moderately “expanded” or maximized binary followed by a minuet. This is commercial fare par excellence.

The principle of contrast is taken to such an extreme at the beginning of the first movement (Ex. 8-8a) as to amount practically to a spoof—“ingenious jesting with art,” as Domenico Scarlatti, galant avant la lettre (galant before it had a name), might have said. The tonic is established with a deliberately over-pompous four-measure fanfare in orchestral style, thumped out with octaves in the bass. It is followed by a three-bar transition to a half cadence, after which the key, the texture, and even the scoring (thanks to the entrance of the obbligato) all change suddenly: a long, lyrical, legato melody in two distinct halves, accompanied by a counterpoint-dissolving Alberti bass.

EX. 8-8A Carl Friedrich Abel, Sonata in B-flat, Op. 2, no. 4, first movement, mm. 1–11

EX. 8-8B Carl Friedrich Abel, Sonata in B-flat, Op. 2, no. 4, end of second movement

The second half embarks on its journey from the dominant to the tonic with a reference to the opening fanfare—treating it, in other words, in the manner of a ritornello. Thus invoking or alluding to the concerto genre is another way of jesting ingeniously. This time the fanfare dissolves into a new melody whose job it is to lead (through some chromatic harmony and some asymmetrical phrase lengths) to the FOP, in this case D minor (iii), articulated by a reference to the second part of the lyrical theme introduced before the double bar.

The D minor cadence is followed unceremoniously by a brusque return to the tonic through the briefest of transitional motives in the bass. When the tonic arrives, of course, so does the opening fanfare (ritornello), and the movement proceeds to its conclusion through an only slightly abbreviated replay of the whole first half of the movement, the only differences being the omission of the no longer necessary transition to the dominant half cadence (mm. 5–7 in Ex. 8-8a) and the transposition of the long lyrical tune from its original pitching in the key of the dominant to the tonic. The second half of the piece could be described as containing virtually the whole first half, plus a bridging section devoted to harmonic caprice.

The minuet is about as ingratiating, unproblematic, and “popular” as the composer could have made it. The first half does not even leave the tonic; it consists of two parallel periods, the first ending on a half cadence, the second on a full—the sort of thing called “open” and “closed” as far back as the Middle Ages and still common in the eighteenth century in folk (i.e., “popular”) tunes, of which Abel’s minuet thus counts as a sort of sophisticated—or, in the etymological sense, “urbane”—imitation. Because the first half does not leave the tonic, the dominant can function in the second half as the FOP. There are no cadences at all on secondary functions, just an occasional whiff of chromaticism (including a lone diminished seventh) on the way to the last dominant cadence.

When the piece is effectively complete, the composer tacks on a 16-bar coda (Ex. 8-8b) over a satisfying tonic pedal, reasserting both tonal and rhythmic stability at maximum strength. The whole passage might as well have been written for the sake of this book, to provide a demonstration of phrase symmetry. The sixteen bars are really eight plus an exact repetition, and each eight breaks down to four plus four, in which the first four consists of a two-bar plagal cadence and its literal repetition, and the second four consists of the very same plagal cadence joined to an authentic one. More naively “natural” than this—as opposed to cunningly “artificial”—music could hardly get. (But of course to be this “natural” takes a lot of artifice.) It is in the second half of the minuet, by the way, that the harpsichord and the “accompanying” instrument get to engage in a bit of dialogue (the only imitative or even contrapuntal writing in the whole sonata), effectively precluding a performance of the piece as a straight keyboard sonata. It is genuine chamber music for actual chamber (that is, domestic) use, and its style and tone are wholly typical of the genre in its earliest stage.

But whence this cult of the “natural”? And where, once and for all, did the style we have been tracking in this chapter originate? We still have not traced this very important river to its source, for all the hints and suggestions thrown out along the way. Far from solving the historical problem (the problem of the “black hole”) with which we launched this chapter, all we have been doing is restating it over and over again, da capo, with variations and embellishments.

As the very existence of the “Alberti bass” already suggests, there was a slightly earlier but mainly concurrent repertoire of sonatas by Italian composers who deserted the violin family for the keyboard. Their work may indeed be compared with the music of the Bach sons and their friends, and has often been cited as its main model. Besides Alberti himself, whose name mainly lives on thanks to the term associated with it, the most famous member of this group was the Venetian opera composer Baldassare Galuppi (1706–85), a major international figure, who left in addition to his stage works almost one hundred keyboard sonatas of which only a fraction were published, mainly in two books of six issued by the London publisher John Walsh in the late 1750s.

In style, Galuppi’s sonatas (and Alberti’s, too) are eminently galant (see Ex. 8-9): their textures are homophonic, replete with arpeggiated basses and similar figurations; they consist of two or three movements, almost uniformly in binary form; and the keyboardists proceed not by spinning out motives in great waves and sequences in the manner of the older violinists (or their best pupil, Bach the Father), but through short-breathed contrast and balance, and through lyrical, symmetrically laid-out and cadentially articulated melodies. Their evident model was not tireless bowing, but graceful singing. And what else would one expect from composers who worked mainly for the stage?

EX. 8-9A Domenico Alberti, Sonata in C, Op. 1, no. 3 (London, 1748), mm. 1–4.

EX. 8-9B Baldassare Galuppi, Sonata no. 2 (London, 1756), I, mm. 69–79

Once again we are returned to opera as source of it all; but now, having named Galuppi, we are in a position to make a more positive and specific identification of the operatic source. Beginning in the 1740s, Galuppi was the first major international protagonist of a new operatic genre, one that he and his main librettist Carlo Goldoni called dramma giocoso (“humorous drama”), but that took Europe by storm (and is now remembered) as opera buffa—from buffo, Italian for buffoon or clown. If the opera seria was a form of nobly sublimated musical tragedy, opera buffa was musical comedy—the earliest form of full-fledged comic opera.

Here at last is where the body, as the saying goes, is buried. Here is the great stylistic transformer of European music, the spark that ignited what Daniel Heartz called the “main evolution” that somehow managed to take place behind the backs of Bach the Father and Handel. In the comic opera lies the common source for all the musical styles we have been tracking, even the nominally melancholy empfindsamer Stil. And as we shall see, by the late eighteenth century, opera buffa would decisively replace (or more precisely, displace) the seria as the most vital—and even serious!—form of musical theater.

But to appreciate the role of “humorous drama” as a hotbed of stylistic transformation or a plugger of historical holes, which after all is what we have set out to do in this chapter, we must look beyond it to its own antecedents. Then we shall have a proper starting point from which to tell at least the beginnings of a coherent story about the musical eighteenth century, and its relationship to the general social and intellectual currents of the time. One more flashback is necessary.

During opera’s first century, especially at the public theaters of Venice (and as we have known since chapter 1), it was considered good form to mix serious and comic scenes and characters, producing a kind of heterogeneous “Shakespearean” drama that afforded audiences the very utmost in varied entertainment. Then the reformers got to work. Seeking to restore the dignity of the earliest “neoclassical” (courtly) operas and justify the genre in light of classical poetic theory, librettists began to regard comic scenes as breaches of taste. Such scenes were banished, at first by the high-minded dilettantes who ran the learned academies, finally by the frosty Metastasio.

But what is kicked out the front door often climbs back in through the window. The public, especially in Venice, was unwilling to give up a favorite operatic treat—nor, more to the point, were they willing to forgo the pleasure of seeing and hearing their favorite buffi, many of whom had large followings. So a curious compromise was reached. The newly standardized opera seria remained free of any taint of comedy, but little comic plays with music were shown during the intermissions. These, naturally enough, were called intermezzos (“intermission plays”). They were usually in two little acts (called parte, “parts”) to supply the intermissions required by a typical three-act opera seria, and almost always featured two squabbling characters, a soprano and a bass, these being the most typical ranges for buffi. Often enough they were at first loosely based on the comedies of Molière or his many imitators.

The first set of intermezzos for which a libretto survives was given in Venice in 1706 (it was called Frappolone e Florinetta after its bickering pair). Immediately specialist librettists and composers sprang up for the genre, and it assumed a very particular style. It is that style, which directly reflected the strange nature of the relationship between the intermezzos and their host operas, that played such a colossal—and entirely unforeseen—role in the evolution of eighteenth-century music. We have already seen some of the unforeseen products of that evolution. Their existence is the famous “problem” we have been addressing. Here, at last, are the beginnings of a solution to it, based on recent investigations and speculations by a number of scholars, particularly Piero Weiss and Wye J. Allanbrook, who have made progress at filling the black hole.19

The first big international hit scored by an intermezzo composer was Il marito giocatore e la moglie bacchettona (“The gambler husband and the domineering wife”) by Giuseppe Maria Orlandini (1676–1760), a Florentine composer active in Bologna who was even older than Bach the Father, and who actually spent most of his life composing opera seria to lofty “Arcadian” libretti. The set contains three intermezzos, each depicting an episode in the rocky married life of the title characters: in the first, the wife, exasperated at the husband’s behavior, resolves to divorce him; in the second the husband, disguised as the judge at the divorce court, promises to find in the wife’s favor if she will sleep with him and, after she agrees, reveals himself and throws her out of the house; in the third, the wife comes back disguised as a mendicant pilgrim and soothes the husband into a reconciliation.

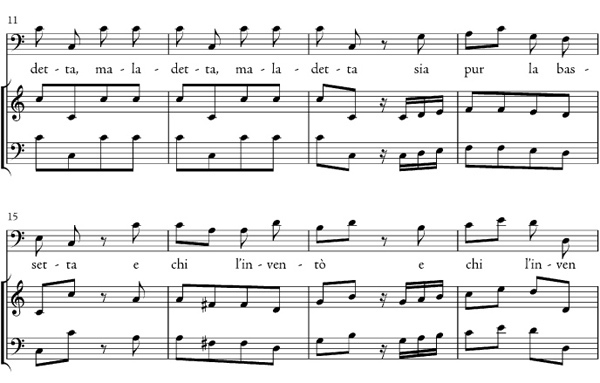

First performed in 1715 (as Bajocco e Serpilla, after the names of the title characters), Orlandini’s intermezzos made the rounds of all the Italian theaters as actual intermission features, and, performed in sequence as a sort of three-act comic opera in their own right, conquered foreign capitals as well, reaching London (as The Gamester) in 1737, and Paris (as Il giocatore) aslateas 1752. Everywhere it made a sensation. Perhaps the aria in which the distraught husband hurls imprecations at his wife will show why (Ex. 8-10).

In keeping with the strictest Aristotelian principles, according to which tragedy portrayed “people better than ourselves” and comedy “people worse than ourselves,” this aria is “low” music with a perfect vengeance.20 Everything about it is impoverished. The texture is reduced to unisons. The vocal line is reduced to barely articulate ejaculations of rage. The melody is reduced to asthmatic gasping and panting with insistently repeated cadences that prevent phrases from achieving any length at all. The structure is reduced to a patchwork or mosaic of these little sniffles, snorts, and wheezes. It might be thought a mere parody, and so the music of the early intermezzos is often described. And yet it came, particularly to foreign audiences, as a revelation.

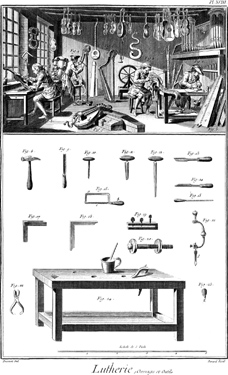

FIG. 8-8 “Instrument making” (Lutherie) from Diderot’s Encyclopédie.

One of the most precious testimonials to that revelation came from the pen of Denis Diderot, the famous French encyclopedist, in his satire Rameau’s Nephew, written early in the 1760s, while the elder Rameau was still alive.

EX. 8-10 Bajocco’s aria from Giuseppe Maria Orlandini’s Il giocatore

From the mouth of this fictional character (albeit based on a real person, a nephew of the great French composer who plied a modest trade as a music teacher and who had a considerable reputation in society as a “character”), Diderot voiced the widespread amazement of French artists and thinkers at the art of the buffi: “What realism! What expression!” he exclaims. And to those who might scoff—“Expression of what?!”—he spells it out with ardor bordering on anger, and with characteristically bizarre imagery:

It is the animal cry of passion that should dictate the melodic line, and these moments should tumble out quickly one after the other, phrases must be short and the meaning self-contained, so that the musician can utilize the whole and each part, varying it by omitting a word or repeating it, adding a missing word, turning it this way and that like a polyp, but without destroying it.21