The paradox is that Handel, the worldly spirit, is most characteristically represented in today’s repertory by his vocal music on sacred subjects, while Bach, the quintessential religious spirit, is largely represented by secular instrumental works. And yet it may be less a paradox than a testimonial to the thoroughly secular, theatrical atmosphere in which all music is now patronized and consumed, and the essentially secular, theatrical spirit that informs even Handel’s ostensibly sacred work—a spirit that modern audiences instinctively recognize and easily respond to. The modern audience, in short, recognizes and claims its own from both composers; and in this the modern audience behaves the way audiences have always behaved. Nor is it in any way surprising: Handel, not Bach, was present at the creation of “the modern audience.” Indeed, he helped create it.

Not that Handel’s secular instrumental output was by any means inconsiderable or obscure. We have already had a look at one of his two dozen concerti grossi, works that (simply because they were published) were far better known in their day than the Brandenburg Concertos or any other instrumental ensemble works of Bach (see Exx. 5-13 and 14). Handel also composed a number of solo organ concertos for himself to perform between the acts of his oratorios. In their origins they were thus theatrical works, but two books of them were published (one of them as a posthumous tribute) and became every organist’s property.

In addition, more than three dozen solo and trio sonatas by Handel survive, of which many also circulated widely in print during his lifetime. Except for a single trio sonata and some instrumental canons in a miscellaneous collection called The Musical Offering, and a single church cantata published by a municipal council to commemorate a civic occasion, the only works of Bach that were published during his lifetime were the keyboard compositions that he published himself.

FIG. 7-1A Portrait by Christoph Platzer, ca. 1710, believed to be the twenty-five-year-old Handel, who was then completing his Italian apprenticeship.

FIG. 7-1B Full-length statue of Handel by Louis François Roubillac (1705–1762).

Handel’s largest instrumental compositions, like Bach’s, were orchestral suites. And as befits the history of the genre, Handel’s orchestral suites were among the relatively few compositions of his that arose directly out of his employment by the Hanoverian kings of England. One was a kind of super-suite, an enormous medley of instrumental pieces of every description (but mostly dances) composed for performance on a barge that kept abreast of George I’s pleasure boat during a royal outing on the River Thames on 17 July 1717, later published as “Handel’s Celebrated Water Musick.” A whole day’s musical entertainment, it furnished enough pieces for three separate sequences (suites in F, D, and G) as arranged by the publisher.

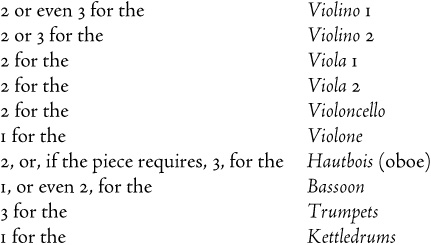

Handel’s other big orchestral suite was composed for an enormous wind band (twenty-four oboes, twelve bassoons, nine trumpets, nine horns, and timpani, to which strings parts were added on publication) and performed on 27 April 1749 as part of the festivities surrounding the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle that ended the War of the Austrian Succession. This was a great diplomatic triumph for George II, who had personally led his troops in battle (the last time any British monarch has done so) and won important trade and colonial concessions from the other European powers, including a monopoly on the shipping of slaves from Africa to Spanish America. Handel’s suite was published as “The Musick for the Royal Fireworks.” In arrangements for modern symphony orchestra by the English conductor Sir Hamilton Harty, these suites of Handel’s were for a while staples of the concert repertoire—especially in England, where they served as a reminder of imperial glory. They are the only Handelian instrumental compositions ever to have gained modern repertory status comparable to that enjoyed by the “Brandenburgs,” and they lost it when England lost her empire. Handel’s instrumental music was always a sideline, and so it remains for audiences today, even though modern audiences value instrumental music far more highly than did the audience of Handel’s time and are much more likely to regard instrumental works as a composer’s primary legacy.

For Handel was first and last a composer for the theater, the one domain where Bach never set foot. His main medium was the opera seria, the form surveyed in chapter 4. There we had a close look at the genre as such. Here we can concentrate on Handel’s particular style as a theatrical composer. For our present purpose it will suffice to boil his entire quarter-century’s production for the King’s Theatre on the London Strand down to a single consummate example. Such an example will of course have to be a virtuoso aria giving vent to an overpowering emotional seizure; for an opera seria role, as we know, was the sum of the attitudes struck in reaction to the complicated but conventionalized unfolding of a moralizing plot in a language that was often neither the composer’s nor the audience’s. The great opera composer was the one who could give the cut-and-dried, obligatory attitudes a freshly vivid embodiment, and who could convey it essentially without words.

Nothing could serve our purpose better than an aria from Rodelinda, one of Handel’s most successful operas, first performed at the King’s Theatre on 13 February 1725, right in the brilliant middle of Handel’s operatic career, and revived many times thereafter. The libretto was an adaptation—by one of Handel’s chief literary collaborators, Nicola Francesco Haym, an expatriate Italian Jew who also acted as theater manager, stage director, and continuo cellist—of an earlier opera libretto, produced in Florence, that was based on a play by the French tragedian Pierre Corneille that was based on an episode from a seventh-century chronicle of Lombard (north Italian) history.

The title character is the wife of Bertrarido, the heir to the throne of Lombardy, who has been displaced and forced into exile by a usurper, Grimoaldo, the Duke of Benevento, who has succeeded in his plan with the treasonable aid of Garibaldo, the Duke of Turin, a former ally of Bertrarido. The moral and emotional center of the plot is the steadfastness of Rodelinda’s love for Bertrarido and his for her, enabling both their reunion and Bertrarido’s restoration to his rightful throne.

FIG. 7-2 Caricature of the alto castrato Senesino, the natural soprano Francesca Cuzzoni, and the alto castrato Gaetano Berenstadt in a performance of Handel’s opera Flavio at the King’s Theater, London, in 1723.

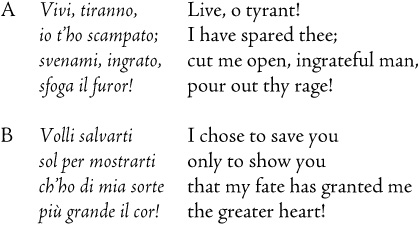

The aria on which we focus, Bertrarido’s “Vivi, tiranno!” (Ex. 7-1), was actually added to the opera for its first revival, in December 1725, so as to give the noble Bertrarido a more heroic aspect and also to favor the famous alto castrato Senesino with a proper vehicle for displaying his transcendent vocal artistry. It is sung when Bertrarido, having killed Garibaldo off stage, returns to confront Grimoaldo. Instead of killing him outright, he hurls his sword to the ground at his rival’s feet and sings, contemptuously:

Like a good seria character, Grimoaldo capitulates to this demonstration of austere magnanimity and gives up his claim to the throne.

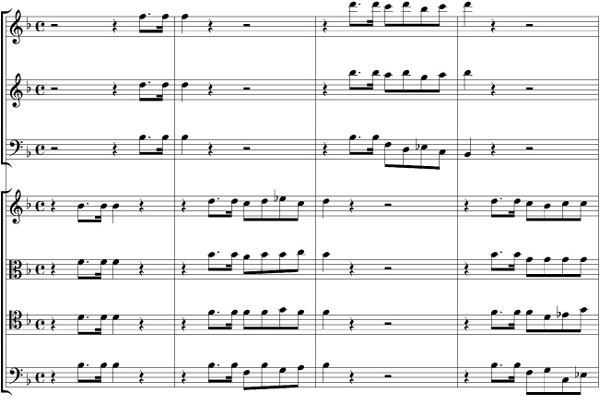

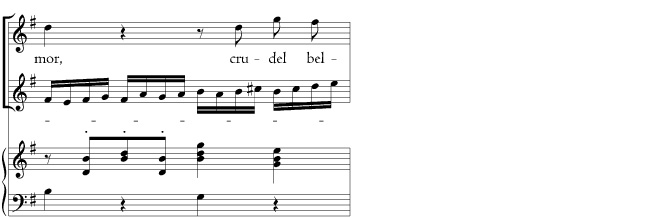

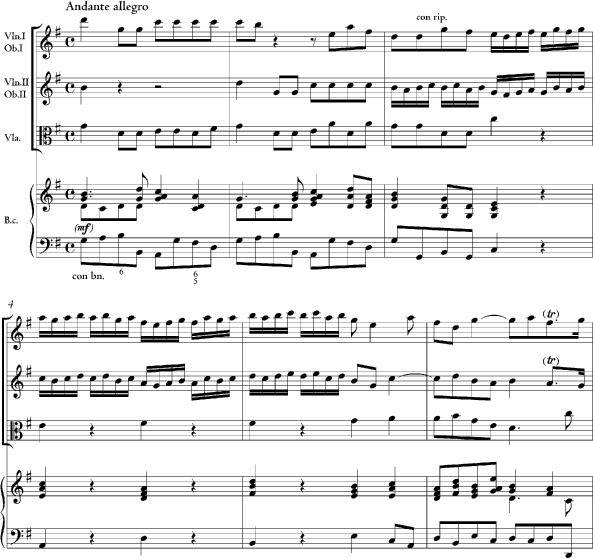

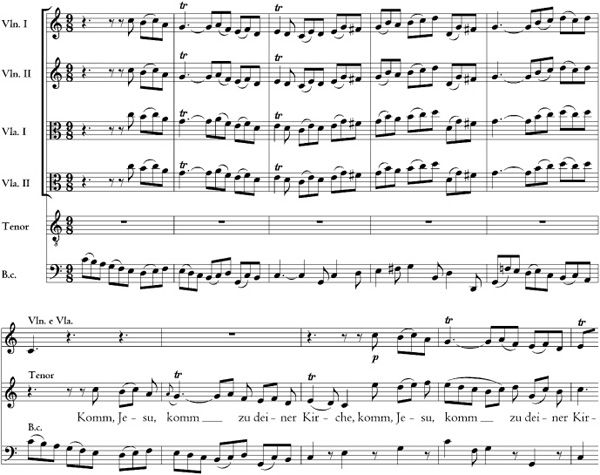

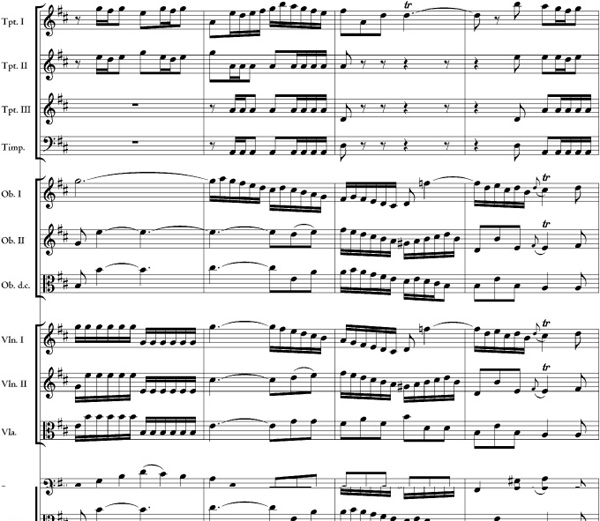

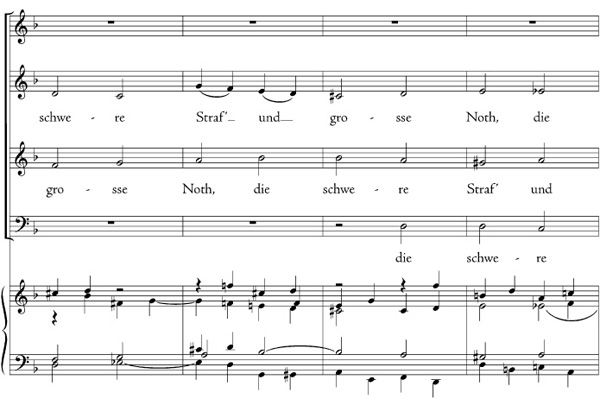

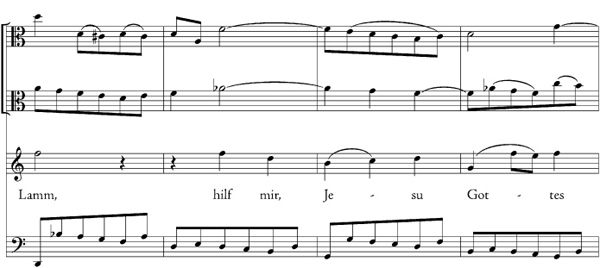

“Vivi, tiranno!” is a perfect—and perfectly thrilling—specimen of aria as “concerto for voice and orchestra.” Its “A” section is structured exactly like a Vivaldi concerto, with a three-part ritornello that frames the whole, and returns piecemeal in between the vocal episodes (Ex. 7-1a). It symbolizes the aria’s affect—stormy indignation, thundering wrath (both as felt by Bertrarido and as summoned forth from Grimoaldo)—with string tremolos that can be related either to the old stile concitato or to the onomatopoetical writing we encountered in the storm episode from Vivaldi’s “Spring” concerto. As we know from chapter 4, such devices were standard procedure in the “simile arias” that formed the opera seria composer’s stock-in-trade. The tremolo clearly retains its meaning in Handel’s aria, even though there is no explicit simile (that is, no direct textual reference to the storm to which the characters’ emotions are being musically compared).

As in the most schematic concerto movement, the vocal part in “Vivi, tiranno!” never quotes or appropriates the music of the ritornello and never carries material over from episode to episode. It is a continually evolving part cast in relief against the dogged constancy of the ritornello. Indeed the opposition of solo and tutti is dramatized beyond anything we have seen in an instrumental concerto. It is made exceptionally tense—even hostile—by having the instruments continually insinuate the ritornello within the episodes whenever the singer pauses for breath, only to be silenced peremptorily on the voice’s return. This, too, is expressive of an unusually tense and hostile affect.

The most spectacular representation of rage, however, is reserved to the singer and takes the most appropriate form such a thing can take within a dramatic context. The progressively fierce and florid coloratura in this aria is calculated to coincide on every occurrence with the word furor—“rage” itself. The singer literally “pours it out” as the text enjoins, setting Grimoaldo a compelling and exhausting example. The most furious moment of all comes when one of the singer’s rage-symbolizing roulades is cast in counterpoint against the stormy tremolandos in the accompanying parts (Ex. 7-1b).

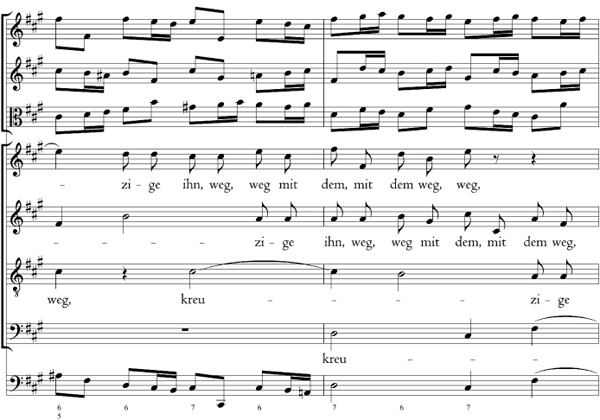

EX. 7-1A George Frideric Handel, “Vivi, tiranno!” from Rodelinda, Act III, scene 8, mm. 1–18

EX. 7-1B George Frideric Handel, “Vivi, tiranno!” from Rodelinda, Act III, scene 8, mm. 68–81

The aria, in short, is a triumph of dramatically structured music—or of musically structured drama, if that seems a better way of putting it. The “purely musical” or structural aspects of the piece and the representational or expressive ones are utterly enmeshed. There is no way of describing the one without invoking the other. An intricately worked out and monumentally unified, thus potentially self-sufficient, musical structure serves to enhance and elevate the playing-out of a climactic dramatic scene. And the structure, in its lapidary wholeness, with contrasting midsection and suitably embellished reiteration, enables the singer-actor to reach a pitch that is both literally and figuratively beyond the range of spoken delivery.

Comparing Handel’s aria with the opera seria arias examined in chapter 4—mostly by actual Italian composers writing for actual Italian audiences—points up the somewhat paradoxical relationship of this great outsider to the tradition on which he fed. It is Handel who, for many modern historians and the small modern audience that still relishes revivals of opera seria, displays the genre at its best, owing to the balancing and tangling of musical and dramatic values just described. Handel’s work is indeed more craftsmanly and structurally complex than that of his actual Italian contemporaries, who were much concerned with streamlining and simplifying those very aspects of motivic structure and harmony that Handel continued to revel in.

His work, in short, was at once denser (and, to an audience foreign to the language of the play, perhaps more interesting) and stylistically more conservative. In his far more active counterpoint (just compare his bass line to Vinci’s or Broschi’s in chapter 4) he affirms his German organist’s heritage after all, for all his Italian sojourning and acclimatizing. And by making his music more interesting in its own right than that of his Italian contemporaries, he gave performers correspondingly less room to maneuver and dominate the show.

In this way, for all that Handel seems to dominate modern memory of the opera seria, and despite his unquestioned dominance of the local London scene (at least for a while), he was never a truly typical seria composer, and as time went on, his work became outmoded. Unlike the actual Italian product, his operas never traveled well but remained a local and somewhat anomalous English phenomenon, admired by foreign visitors but nevertheless regarded as strange. A crisis was reached when Farinelli—the greatest of the castratos, with whose typical vehicles we are already familiar—refused to sing for Handel and in fact joined a rival company set up in ruinous opposition to him. The 1734 pastiche production of Artaserse sampled in chapter 4 was in fact a deliberate effort, on the part of the rival Opera of the Nobility, to depose Handel from his preeminence and, Grimoaldo-like, usurp his place in the affections of the London opera audience.

FIG. 7-3 A scene from Gay and Pepusch’s Beggar’s Opera as painted in 1729 by William Hogarth. The wife and the lover of Macheath the highwayman plead with their respective fathers to spare his life.

Handel’s grip on the London public, or at least its most aristocratic faction, had already been challenged somewhat in the 1720s by a series of easy, tuneful operas by Giovanni Bononcini (1670–1747) imported to London together with their composer, a somewhat older man than Handel but one whose style was more idiomatically Italian and up-to-date. Another bad omen for Handel, the worst in fact, was the huge success in 1728 of The Beggar’s Opera, a so-called “ballad opera” by John Gay, with a libretto in English, spoken dialogue in place of recitative, and a score consisting entirely of popular songs arranged by a German expatriate composer named Johann Pepusch (1667–1752).

This cynical slap in the face of “noble” entertainments like the seria had an unprecedented run of sixty-two performances during its first season (for a Handel opera a run of fifteen performances was considered a great success), and, altogether amazingly, was revived every season for the rest of the eighteenth century and beyond. (It has had hit revivals even in the twentieth century and spawned a huge number of spinoffs and adaptations, including some very famous ones like the Threepenny Opera of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill.) On every level from its plot (set among thieves and other London lowlifes) to its “moral” (namely, that morals are sheer hypocrisy) to its musical and dramatic allusions (full of swipes at operatic conventions and lofty “Handelian” style), The Beggar’s Opera has been characterized as “frivolously nihilistic.”1 But it also played into a prejudice that was the very opposite of frivolous or nihilistic—namely, a peculiarly English version of the old prejudice (as old, we may recall, as Plato) against “delicious” music as a corrupting force that was inimical to the public welfare. The “soft and effeminate Musick which abounds in the Italian Opera,” wrote the playwright John Dennis (1657–1734), a particularly vociferous London critic, “by soothing the Senses, and making a Man too much in love with himself, makes him too little fond of the Publick; so by emasculating and dissolving the Mind, it shakes the very Foundation of Fortitude, and so is destructive of both Branches of the publick Spirit.”2 In an Essay upon Publick Spirit published in 1711, the year of Handel’s London debut, Dennis even argued that British wives should keep their men away from the opera lest they become “effeminate” (by which he meant homosexual). And he proceeded to attach this issue to one that mattered in Britain as it mattered at that time nowhere else on earth—the issue of patriotism, and its attendant religious bigotry:

Is there not an implicit Contract between all the People of every Nation, to espouse one another’s Interest against all Foreigners whatsoever? But would not any one swear, to observe the Conduct of [opera lovers], they were protected by Italians in their Liberty, their Property, and their Religion against Britons? For why else should they prefer Italian Sound to British Sense, Italian Nonsense to British Reason, the Blockheads of Italy to their own Countrymen, who have Wit; and the Luxury, and Effeminacy of the most profligate Portion of the Globe to British Virtue?

One need hardly add that all of these fears and intolerances intersected on the sexually ambiguous figure of the castrato, the very epitome of Italian license and excess, who added insult to injury by commanding princely fees far beyond the earning power of domestic singers. In the same year that Dennis’s essay appeared, Joseph Addison, the eminent satirist, poked malicious fun at the castrati and their fans through an invented character, “Squire Squeekum, who by his Voice seems (if I may use the Expression) to be ‘cut out’ for an Italian Singer.”3

The Beggar’s Opera gave all of these resentful views a colossal boost. Its success was a presage that the opera seria, even Handel’s, could no longer count on the English audience to take it seriously. And indeed, within a decade of its production, both Handel’s own opera company and the Opera of the Nobility had gone bankrupt. Neither Handel nor the castrati were the losers, though. As Christopher Hogwood, a notable performer of Handel’s music and a leader in the revival of an “authentic” period style of presenting it, has shrewdly observed, if The Beggar’s Opera was a bad omen it was because it “killed not the Italian opera but the chances of serious English opera”4—something that would not emerge until the twentieth century, and then only briefly.

Meanwhile, if Handel was to continue to have a public career in England, it would have to be on a new footing. It would take another kind of lofty entertainment to recapture his old audience. Here is where Handel’s unique genius—as much a genius for the main chance as for music—asserted itself. Whenever opera had encountered obstacles on its Italian home turf—for example, those pesky ecclesiastical strictures against operating theaters during Lent—its creative energies had found an outlet in oratorio, especially in Rome, where Handel had served his apprenticeship. Handel had even composed a Roman oratorio himself (La resurrezione, 1708) and on a trip back to Germany in George I’s retinue he composed a German oratorio on the same Easter subject: Der für die Sünde der Welt gemartete und sterbende Jesus (“Jesus, who suffered and died for the sins of the world”), usually called the Brockes Passion after the name of the librettist.

In fact, Handel had already composed some minor dramatic works on English texts, including Acis and Galatea (1718), a mythological masque, and another masque, Haman and Mordecai on an Old Testament subject, both commissioned by an English patron, the Duke of Chandos, for performance at his estate, called Cannons. Handel had also enjoyed great success with some English psalm settings he had written on commission from the same patron (now called the Chandos Anthems), in which he had drawn on indigenous choral genres for which Purcell had set the most important precedents: anthems and allegorical “odes” to celebrate the feast day of St. Cecilia (music’s patron saint), royal birthdays, and the like.

FIG. 7-4 Handel directing a rehearsal of an oratorio, possibly at the residence of the Prince of Wales.

A pastiche revival of Haman and Mordecai, expanded and refurbished (though not by Handel) and retitled Esther, was performed in 1732 in the explicit guise of “an oratorio or sacred drama” and attracted so much interest that Handel himself conducted a lucrative performance on the stage of the King’s Theatre, where business that year was otherwise slow. The next year Handel wrote a couple of English oratorios himself (Deborah, Athalia). As operatic bankruptcy loomed, these experiences gave Handel an idea that the English public might welcome a new style of vernacular oratorio tailored to its tastes and prejudices. The result was Saul (1739), a musical theater piece of a wholly novel kind that differed in significant ways from all previous oratorio styles. As a genre born directly out of the vicissitudes of the British entertainment market, the Handelian oratorio was a unique product of its time and place.

How was it new? The traditional Italian oratorio was simply an opera seria on a biblical subject, by the early eighteenth century often performed with action, although this was not always allowed. In England, the acting out of a sacred drama was prohibited by episcopal decree, but Saul was still more or less an opera in the sense that its unstaged action proceeded through the same musical structures, its dramatic confrontations being carried out through the customary recitatives and arias, making it easy for the audience to supply in their imagination the implied stage movement (sometimes vivid and violent, as when Saul, enraged, twice throws his spear, although the actual singer of the role makes no move).

The listener’s mind’s eye was helped in other ways as well. The imaginary action was “opened out” into outdoor mass scenes unthinkable in opera, with opulent masque-like choruses representing the “people of Israel.” Among the main advertised attractions, moreover, was an especially lavish orchestra replete with a trombone choir, with evocative carillons, and with virtuoso instrumental solos, as if to compensate for the diminished visual component. All the same, Saul—like Esther and Deborah before it, and Samson, Belshazzar, Judas Maccabeus, Solomon, and Joshua after it—remained centered in its plot on dramatized human relations, the traditional stuff of opera. It was in a sense the most traditionally operatic of all of Handel’s oratorios, since the title character—the melancholy and choleric ruler of Israel, racked by jealousy and superstition—is complex, and the action implies a judgment of his deeds.

The other Old Testament oratorios listed above (excepting only Belshazzar) are all tales of civic heroism and national triumph. Esther, Deborah, Samson, Judah Maccabee, and Joshua were all saviors of their people, the Chosen People. All were heroes through whom the nation, over and over again, proved invincible. (And even Belshazzar, while not directly about Israel’s heroism, depicts the destruction of Israel’s adversary.) Here is where Handel truly showed his mettle in catering to his public, for the English audience—an insular people, an industrious and prosperous people, since the revolutions of the seventeenth century a self-determining people ruled by law, and (as we have seen) a latently chauvinistic people—identified strongly with the Old Testament Israelites and regarded the tales Handel set before them as gratifying allegories of themselves. “What a glorious Spectacle!” wrote one enraptured observer

to see a crowded Audience of the first Quality of a Nation, headed by the Heir apparent of their Sovereign’s Crown [the future George III], sitting enchanted at Sounds, that at the same time express’d in so sublime a manner the Praises of the Deity itself, and did such Honour to the Faculties of human Nature, in first creating those Sounds, if I may so speak; and in the next Place, being able to be so highly delighted with them. Did such a Taste prevail universally in a People, that People might expect on a like Occasion, if such Occasion should ever happen to them, the same Deliverance as those Praises celebrate; and Protestant, free, virtuous, united, Christian England, need little fear, at any time hereafter, the whole Force of slavish, bigotted, united, unchristian Popery, risen up against her, should such a Conjuncture ever hereafter happen.5

As the historian Ruth Smith has observed, the author of this letter “deploys the analogy of Britain with Israel to present the idea of a unified nation as natural, desirable, and, in the face of foreign aggression, essential,” and praises Handel’s music as an impetus that “can not only allude to, but actually create, national harmony and strength.”6 Handel’s oratorios, in short, were the first great monuments in the history of European music to nationalism. That was the true source of their novelty, for nationalism was then a novel force in the world.

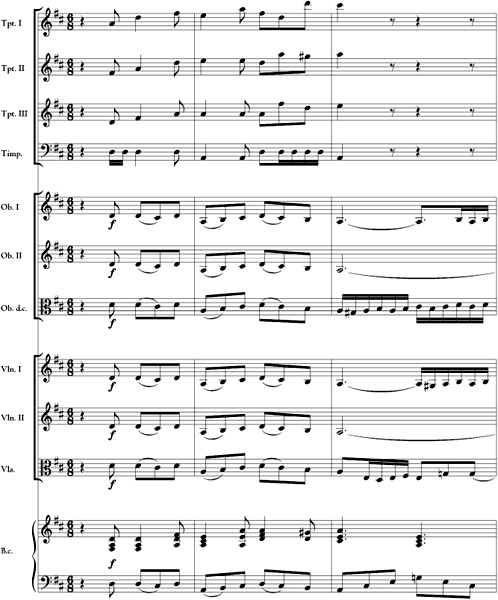

The letter just quoted, printed in the London Daily Post in April 1739, referred to the première performance of Israel in Egypt, the next oratorio Handel composed after Saul, which transformed the genre yet further away from opera and made it yet more novel and more specific to its time and place. For Israel in Egypt almost completely abandons the dramatic format—that is, the representation of human conflicts and confrontations through recitatives and arias—in favor of impersonal biblical narration, much of it carried out by the chorus (i.e., the Nation) directly, often split into two antiphonal choirs as in the Venetian choral concerti of old. It is thus the most monumental work of its kind, and in the specific sense implied by the writer of the letter, which relates to vastness and impressiveness, the most sublime.

This specifically Handelian conception of the oratorio as an essentially choral genre—an invisible pageant, it would be fair to say, rather than an invisible drama—completely transformed the very idea of such a piece. So thoroughly did Handel Handelize the oratorio for posterity that it comes now as a surprise to read contemporary descriptions of his work that emphasize its novelty, indeed its failure to conform to prior expectations. One contemporary listener wrote in some perplexity about Handel’s next biblical oratorio after Israel in Egypt—namely Messiah, now the most famous oratorio in the world and the one to which all others are compared—that “although called an Oratorio, yet it is not dramatic but properly a Collection of Hymns or Anthems drawn from the sacred Scriptures.”7 That is precisely what the word “oratorio” has connoted since Handel’s day. Now it is the dramatic oratorio that can seem unusual.

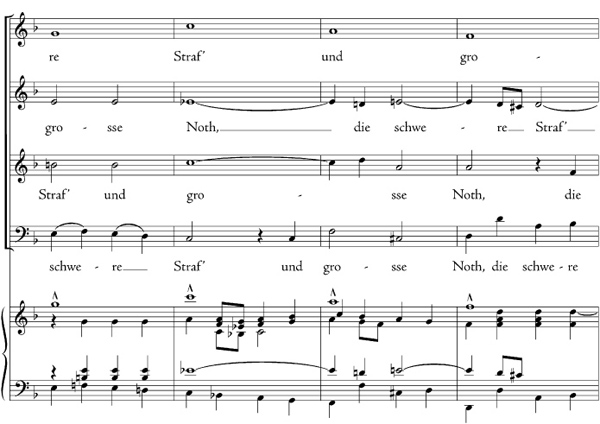

Israel in Egypt, the prototype of the “anthem oratorio,” recounts the story of the Exodus, with a text compiled from scripture by Charles Jennens, a wealthy dilettante who paid Handel for the privilege of collaborating with him, and who had already written the libretto for Saul. This new “libretto” was no original creation but a sort of scriptural anthology that mixed narrative from the Book of Exodus with verses from the Book of Psalms. Its first ten vocal numbers (seven of them choruses) collectively narrate the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt. In musico-dramatic technique they collectively embody a virtual textbook on the state of the “madrigalistic” art—the art of musical depiction—in the early eighteenth century, an art of which Handel, perhaps even outstripping Vivaldi, was past master.

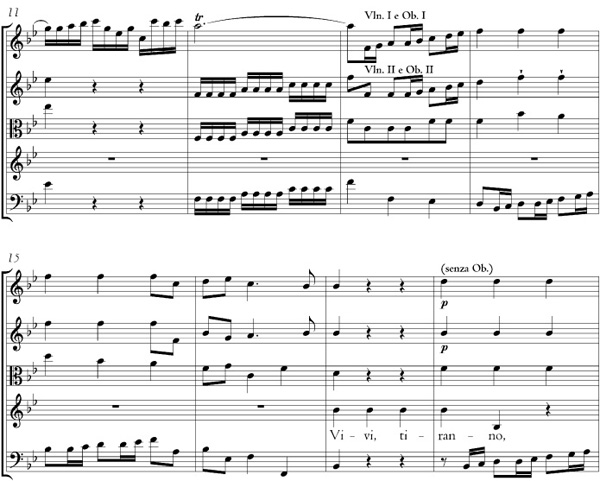

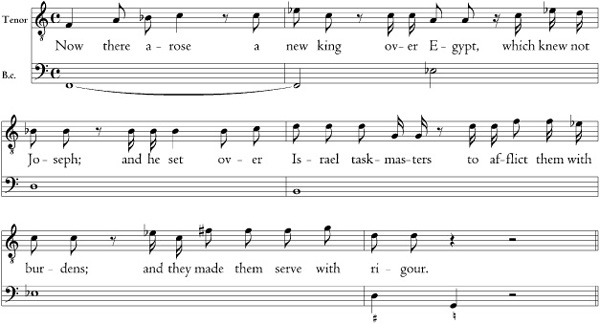

Even the little recitative that introduces the first chorus contains a telling bit of word painting—the dissonant harmony and vocal leap of a tritone illustrating the “rigor” with which the Israelites were made to serve their Egyptian masters (Ex. 7-2a). The fact that these effects of melody and harmony do not exactly coincide with the word they illustrate does not lessen the pointedness of the illustration: the sudden asperities, incongruous with the rest of the music in the recitative, send the listener’s imagination off in search of their justification, which can only be supplied by the appropriate word.

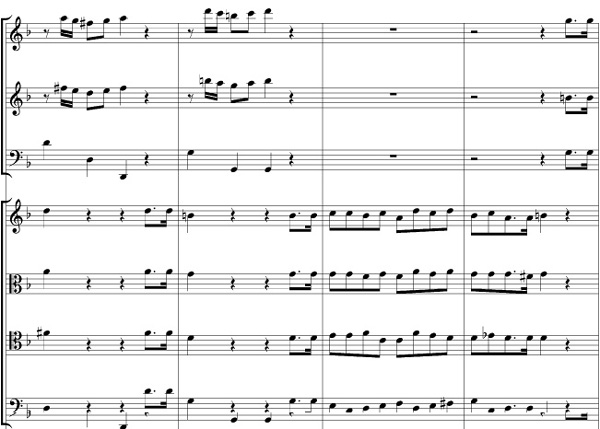

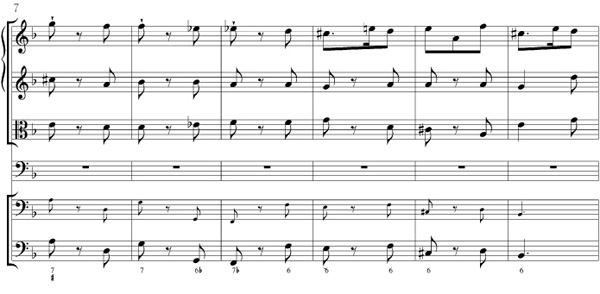

EX. 7-2A George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 2, recitative, “Now there arose a new king”

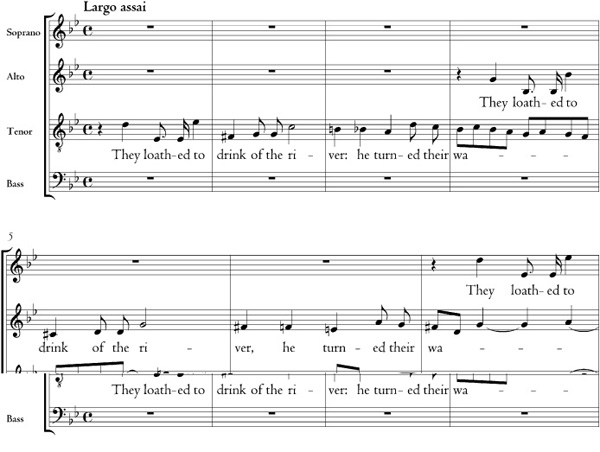

The first of the plagues—the bloody river—is a choral fugue (Ex. 7-2b), in which we again encounter some time-honored devices: melodic dissonance in the subject (a diminished seventh) to portray loathing, and a passus duriusculus to combine that loathing with the river’s flow as the fugue subject recedes from the foreground to prepare for the answer. The next plague (no. 5, “Their land brought forth frogs”) is set not as a chorus but as an “air”—a truncated aria (very common in Handel’s oratorios) in which the “da capo” is represented by its ritornello alone (Ex. 7-2c). Handel chose to make this number a solo item not only to provide some variety for the listener (and some respite for the choristers) but also because he evidently thought the illustrative idea—leapfrog!—would work better as an instrumental ritornello for two violins than in the voice.

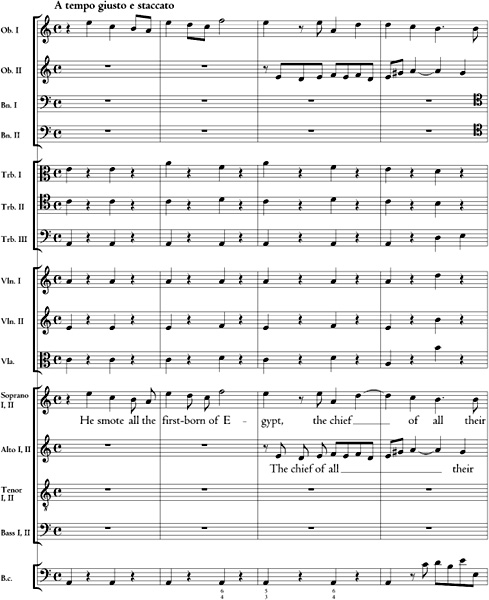

The idea of purely instrumental “imitation of nature” was a Vivaldian idea, as we know from the Four Seasons, but no other composer had ever taken instrumental imitations to such lengths as Handel resorted to in Israel in Egypt—epoch-making lengths, in fact, since the art of “orchestration” as “tone-color composition,” serving expressive or poetic purposes and requiring an extended instrumental “palette,” achieved a new level in Handel’s oratorios, and nowhere more spectacularly than in no. 6, “He spake the word” (Ex. 7-2d). The word here, of course, is the word of God, and so the burnished sound of the trombone choir, associated with regal and spectacular church music since the Gabrielis in Venice at the end of the sixteenth century, was the inevitable choice to echo the choral announcement that God had spoken. Later, the two insects mentioned in the text (flies and locusts) are imitated by string instruments in two sizes. The massed violins are treated especially virtuosically. Demanding of ripienists all a soloist’s skills is another mark of “gourmet” orchestration, marking not only the player but the composer as a virtuoso.

EX. 7-2B George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 4, chorus, “They loathed to drink of the river,” mm. 1–13

EX. 7-2C George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 5, aria, “Their land brought forth frogs,” mm. 1–11

EX. 7-2D George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 6, chorus, “He spake the word,” mm. 1–3

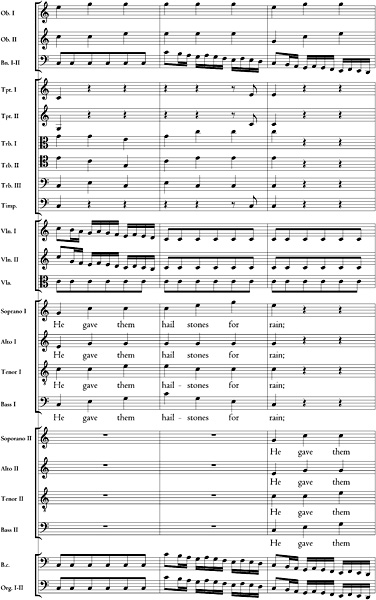

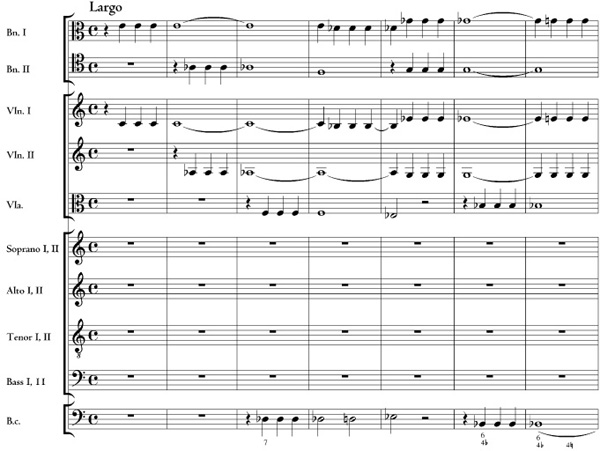

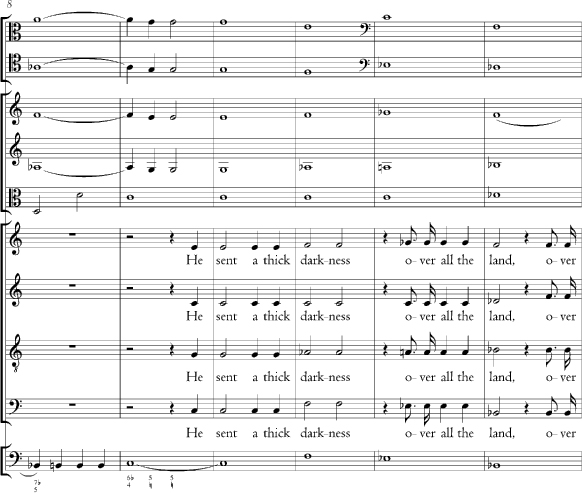

The gathering storm leading to the representation of the “hailstones for rain” in no. 7 (Ex. 7-2e) calls a large assortment of new (woodwind and timpani) colors into play. Here Handel had a precedent in the French court opera, where orchestrally magnificent storm scenes had been a stock-in-trade since Marin Marais’s Alcyone (1706), which spawned a legion of imitators (culminating with a volcanic eruption in Rameau’s Les Indes galantes of 1735) and which, like many court operas, had been published in full score. No. 8, “He sent a thick darkness” (Ex. 7-2f), introduces a new, unheard-of color—high bassoons doubling low violins, but later descending to their normal range and trilling—as well as softly sustained but very dissonant chromatic harmonies to represent the covering gloom. The huge tutti chords slashing on the strong beats in no. 9 (“He smote all the first-born of Egypt”) make almost palpable the grisliest calamity of all (Ex. 7-2g).

Yet no matter how lofty or how grisly the theme, Handel’s representation of the plagues remains an entertainment—an entertainment that an exhaustive description like the one offered here threatens to impair. It has indeed been a tiresome exercise, and apologies are offered to those rightly exasperated by it, for tediously cataloguing the means by which such vivid effects are achieved has the same dampening effect as does the explanation of a joke.

But although the dampening may dull the joke, it may also serve a good purpose if it forces us to realize and confront, through our annoyance, what might be otherwise overlooked or forgotten—that these marvelous and musically epochal illustrations are indeed, for the most part, no more (and no less) than jokes. Like all “madrigalisms,” they depend on mechanisms of humor: puns (plays on similarities of sound), wit (apt conjunctions of incongruous things), caricature (deliberate exaggerations that underscore a similarity). And, as Handel knew very well, audiences react to such effects, despite the awfulness of the theme, as they do to comedy. We giggle in appreciation when we “get” the representation of the leaping frogs and the buzzing flies, and we guffaw when the latter give way to the thundering locusts.

But what of the smiting of all those Egyptian boys? Do we laugh at that, too? We do—or, at least, so the music directs us—just as we have laughed at crop failures, bloody rivers, “blotches and blains.” The withholding of empathy for the Egyptians is an essential part of the biblical account of the Exodus, and the scorn of the biblical Israelites and their religious descendants for the ancient oppressor is what enables the success of Handel’s strategy. This separation of self and other plays also into the ideology of nationalism; a great deal of English national pride (or any nation’s national pride) depends on a perception of separateness from other nations, and superiority to them. Of all of Handel’s oratorios, it is perhaps easiest to see in Israel in Egypt how the manifest religious content coexists with, enables, and is ultimately subordinate to the nationalistic subtext. Hence the essential secularism of its impulse and its enduring appeal.

This applies even to Messiah (1741), the one Handel oratorio that was performed within the composer’s lifetime in consecrated buildings and could count, therefore, as a religious observance. The work, or excerpts from it, is still regularly performed in churches, Anglican and otherwise, especially at Christmas time (although its original performances took place at the more traditional Eastertide). But it is much more often performed in concert halls by secular choral societies. That is appropriate, since, like the rest of Handel’s oratorios, Messiah’s true affinities remain thoroughly theatrical.

EX. 7-2E George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 7, chorus, “He gave them hailstones,” mm. 22–26

EX. 7-2F George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 8, chorus, “He sent a thick darkness,” mm. 1–13

EX. 7-2G George Frideric Handel, Israel in Egypt, no. 9, chorus, “He smote all the first-born of Egypt,” mm. 1–4

What distinguished it from its fellows and gave rise to its occasional special treatment was its subject matter. Practically alone among Handel’s English oratorios, it has a New Testament subject and a text, again compiled by Jennens, drawn largely from the Gospels. That subject, the life of Christ the Redeemer with emphasis first on the portents surrounding his birth, and then on his death and resurrection, brings the work into line with the most traditional ecclesiastical oratorios, and with the even older tradition of narrative Passion settings.

Messiah may have been commissioned by the Lord Lieutenant of Dublin to raise money for the city’s charities. Handel wrote the music with his usual legendary speed—in twenty-four days, from 22 August to 14 September 1741—and finished the orchestral score on 29 October, setting out for Dublin two days later. The first performance took place at the New Music Hall on Fishamble Street on 13 April 1742.

The première performance of Messiah is an especially important date in the history of European music because Handel’s atypical New Testament oratorio is the very oldest work in the literature to have remained steadily in active repertory ever since its first performance. Unlike any other music so far mentioned or examined in this book, with the single equivocal exception of Gregorian chant—and even the chant lost its canonical status at the Second Vatican Council in 1963—Messiah has never had to be rediscovered or “revived,” except in the sense the word is used in the theater, whereby any performance by a cast other than the original one is termed a revival. The continuous performing tradition of European art (or literate) music—which we can now (and for this very reason) fairly call “classical music”—can therefore be said to begin with Messiah, the first “classic” in our contemporary repertoire, and Handel is therefore the earliest of all “perpetually-in-repertory” (“classical”) composers.

Handel himself conducted yearly London “revivals” of Messiah, beginning the next year at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. The work became a perennial and indispensable favorite with the London public when Handel began giving charity performances of it in the chapel of the London Foundling Hospital, starting in 1750. These were the “consecrated” performances that led to the work’s being regarded as an actual “sacred oratorio,” although that was not the composer’s original intention. By the time of Handel’s death on 14 April 1759 (nine days after conducting his last Foundling Hospital Messiah), the British institution of choral festivals had been established, and these great national singing orgies (particularly the Three Choirs Festival, which has continued into our own day) have maintained Messiah as a unique national institution, vouchsafing the unprecedented continuity of its performance tradition (although the style of its performances has continued to evolve over the years, in accord with changing tastes—another sign of a “classic”).

FIG. 7-5 Chapel at the Foundling Hospital, Dublin, where Messiah was first performed.

By the end of the eighteenth century Messiah was accepted and revered as true cathedral music. It is all the more illuminating, therefore, to emphasize and demonstrate its secular and theatrical side. This aspect of the work can be vividly illustrated both from its fascinatingly enigmatic creative history and from its performance history.

In order to compose at the kind of speed required by the conditions under which they worked, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century composers frequently resorted to what have come to be called “parody” techniques—that is, to the reuse or recycling of older compositions in newer ones. Every church and theater composer indulged in the practice. There was really no choice. The only question involved the nature of the sources plundered and the specific means or methods employed. Was it only a process of “cannibalization”—eating one’s own young (adapting one’s own works)—or did it involve what would now be regarded as plagiarism? And if the latter, did the practice carry the ethical stigma now attached to plagiarism—or, for that matter, any stigma at all?

The question comes up with particular inevitability in connection with Handel, since he seems to have been the champion of all parodists, adapting both his own works and those of other composers in unprecedented numbers and with unprecedented exactness. Indeed, ever since the appearance in 1906 of a book (by one Sedley Taylor) entitled The Indebtedness of Handel to Works by Other Composers, the matter has been a cause for inescapable concern on the part of the composer’s admirers, and a whole literature on the subject has sprouted up—two literatures, in fact: one in prosecution of the case, the other in Handel’s defense.

The prosecutors have built an astonishing record. Several of Handel’s works consist largely—in extreme cases, almost entirely—of systematic “borrowings,” as they are euphemistically called. Israel in Egypt is among them. Of its twenty-eight choruses, eleven were based on pieces by other composers, some of them practically gobbled up whole. Three of the plagues choruses—including “He Spake the Word” and “He gave them hailstones,” both singled out for their epoch-making orchestration—were based on a single cantata (or more precisely a serenata, music for an outdoor evening entertainment) by Alessandro Stradella (1639–82), a Roman composer whose music Handel encountered during his prentice years. Compare, for example, Ex. 7-3 with Ex. 7-2d.

Other famous cases detailed by Taylor include a setting of John Dryden’s classic Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day, performed in 1739, the same year as Israel in Egypt, based practically throughout on themes and passages appropriated from a then brand-new book of harpsichord suites (Componimenti musicali) by the Viennese organist Gottlieb Muffat. More recently it has been discovered that no fewer than seven major works composed between 1733 and 1738 draw extensively on the scores of three old operas by Alessandro Scarlatti that Handel had borrowed from Jennens. Perhaps Handel’s most brazen appropriation involved the “Grand Concertos” (concerti grossi), op. 6, familiar to us from chapter 5. They were composed in September and October of 1739 and rely heavily for thematic ideas on harpsichord compositions by Domenico Scarlatti, a fellow member of the Class of 1685, which had been published in London the year before.

Noticing how many of Handel’s “borrowings” involved works from the 1730s, and particularly the exceptionally busy years 1737–39, some historians have tried to connect his reliance on the music of other composers with a stroke suffered in the spring of 1737, brought on by overwork, that temporarily paralyzed Handel’s right hand and kept him from his normal labors. Whether as evidence of generally deteriorated health or as a reason for especially hurried work following his enforced idleness, the stroke has been offered as an extenuating circumstance by some who have sought to defend Handel from the charge of plagiarism.

EX. 7-3 Alessandro Stradella, Qual prodigio e ch’io miri, plundered for Israel in Egypt

Stronger defenders have impugned the whole issue as anachronistic. To accuse Handel or any contemporary of his of plagiarism, they argue, is to invoke the Romantic notion of “original genius” at a time when “borrowing, particularly of individual ideas, was a common practice to which no one took exception” (as John H. Roberts, one of Handel’s ablest “prosecutors,” has stated the case for the defense).8 Going even further, some of Handel’s defenders have claimed his “borrowing” to have been in its way a good deed. “If he borrowed,” wrote Donald Jay Grout (paraphrasing Handel’s contemporary Johann Mattheson), “he more often than not repaid with interest, clothing the borrowed material with new beauty and preserving it for generations that otherwise would scarcely have known of its existence.”9

The philosopher Peter Kivy, in a general discussion of musical representation, once cited a piquant example of such “improvement”: a bit of neutral harpsichord figuration from one of Muffat’s suites that Handel transformed into an especially witty “madrigalism” by summoning it to illustrate Dryden’s description, in the Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day, of the cosmic elements—earth, air, fire, and water—leaping to attention at Music’s command (Ex. 7-4).10 And surely no one comparing the choruses in Ex. 7-2 with their models in Stradella can fail to notice that everything that makes the Israel in Egypt choruses noteworthy in historical retrospect—the lofty trombone chords, the insect imitations, the storm music—came from Handel, not his victim.

Historical distance affects the case in other ways as well: Handel and his quarries being equally dead, it may no longer be of any particular ethical or even esthetic import to us whether Handel actually thought up the themes for which posterity has given him credit. (Nor could he, or any other composer of his day, have had an inkling of the eventual interest posterity would take in his reworkings.) Indeed, comparing Handel’s dazzling reworkings with their often rather undistinguished originals can even cast some doubt on the importance of inventio (as Handel’s contemporaries called facility in the sheer dreaming up of themes) in the scheme of musical values, and cause us to wonder whether that is where true “originality” resides.

And yet it does considerably affect our view of Handel and his times to know that recent scholarship, and particularly John Roberts’s investigations, have pretty well demolished the foundations of the old “defense.” Roberts has shown that what we call plagiarism was so regarded in Handel’s day as well; that, while widespread, “it frequently drew sharp censure”11; and that Handel was often the target of rebuke. One of his critics, ironically enough, was Johann Mattheson, so often cited in Handel’s defense, who openly and angrily accused Handel of copping a melody from one of his operas. Another was Jennens, of all people, who wrote to a friend (in a letter of 1743 that came to light only in 1973) that he had just received a shipment of music from Italy, and that “Handel has borrow’d a dozen of the Pieces & I dare say I shall catch him stealing from them; as I have formerly, both from Scarlatti & Vinci.”12

EX. 7-4A Gottlieb Muffat, Componimenti musicali, Suite no. 4

We know from chapter 4 that Leonardo Vinci, unlike Alessandro Scarlatti, was a contemporary and a rival of Handel’s. Handel “borrowed” from Vinci as a way of making his style more up-to-date, which is to say more profitable. This begins to sound like a familiar plagiarist’s motive for “borrowing,” and Roberts has discovered a unique case where Handel both borrowed from a Vinci score (Didone abbandonata, first performed in 1726) and “pastiched” it as well—that is, arranged it for performance in London under its original composer’s name. Sure enough, Handel rewrote the passages he had borrowed for his own recent operas so as to obscure his indebtedness to Vinci’s. If the old defense—that borrowing carried no stigma—were correct, there would have been no reason for Handel to cover his tracks. And that may also explain why, of all the borrowings securely imputed to him, Handel altered the ones he made from Domenico Scarlatti the most. It may well have been because, of all the music he borrowed, Scarlatti’s keyboard pieces were most likely to be recognized by the members of his own public.

EX. 7-4B George Frideric Handel, Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day

In the case of Messiah, Handel’s known borrowings were of the “cannibalistic” kind—the kind that even now entails little or no disrepute. Self-borrowings, which do not raise any question of ownership, can be called borrowing without euphemism. They are generally regarded, even in the strictest accounting, as a legitimate way for a busy professional to economize on time and labor. And yet they, too, can be revealing in what they tell us about Handel’s (and his audience’s) sense of what was fitting—in a word, about their taste.

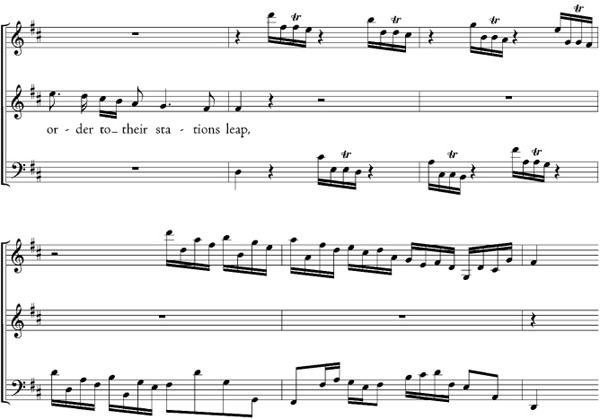

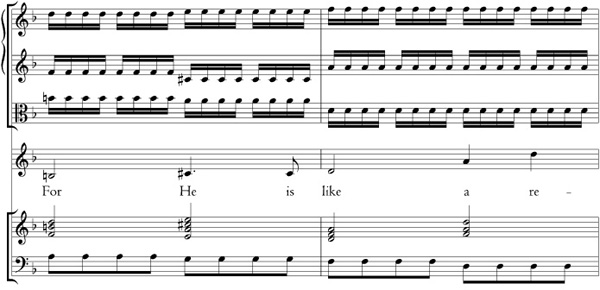

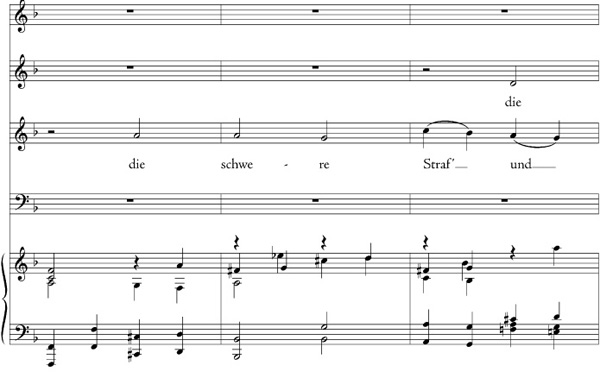

Several of the most famous choruses in Messiah are of an airy, buoyant, affable type that contrasts most curiously with the “sublime” and monumental style of Israel in Egypt. Ornately melismatic, they require a kind of fast and florid, almost athletic singing that is quite unusual in choruses, and they sport an unusually light, transparent contrapuntal texture, in which the full four-voice choral complement is reserved for climaxes and conclusions only. Their virtuosity and their trim shapeliness of form are completely unlike anything one finds in the actual sacred choral music of the day—that is, music meant for performance in church, whether by Handel (who, never having an ecclesiastical patron, wrote very little) or by anyone else.

They are, however, utterly in the spirit of latter-day “madrigalian” genres—genres based on Italian love poetry—such as the chamber cantata pioneered by Carissimi and Alessandro Scarlatti (a genre in which Handel especially excelled during his Italian apprenticeship), and related breeds like the serenata or the duetto per camera.

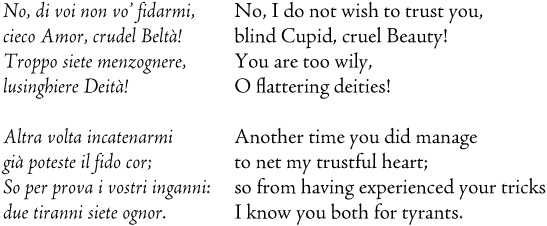

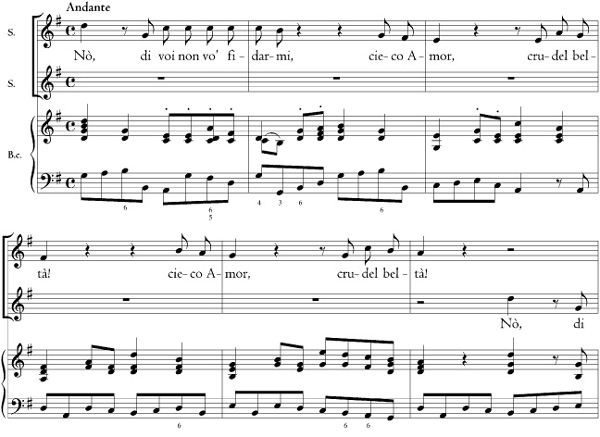

The last-named (the “chamber duet” as it is sometimes called, rather stiltedly, in English) was simply a cantata for two voices. It became popular enough by A. Scarlatti’s time to be regarded as a separate genre—replete with specialist composers, like Agostino Steffani (1654–1728)—partly because in matters of love, two, as they say, is company. Of all the postmadrigalian genres, the duetto was likeliest to be explicitly pagan and erotic. A typical text for such a piece might address or reproach Eros (Cupid) himself, the fickle god of amorous desire:

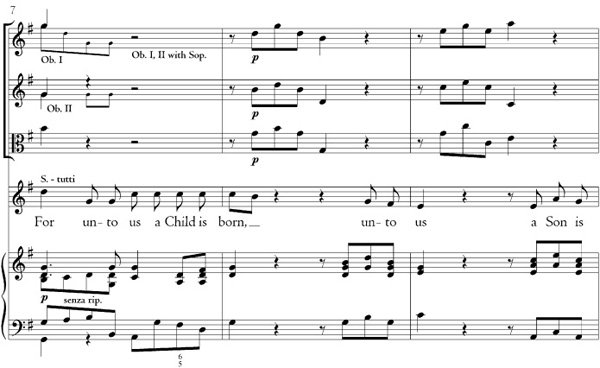

These are the words of a duetto by Handel himself, and as a glance at Ex. 7-5a will show, he wove his paired vocal lines into garlands that wrap around one another to illustrate the “netting” to which the text refers (and behind that, of course, the physical writhing for which the textual words are a metaphor). Should it surprise or dismay us to discover that this erotic duet became the basis for not one but two choruses in Messiah? Handel reworked the opening section into “For unto us a Child is born” (no. 12, Ex. 7-5b) and the closing section (not shown) into “All we like sheep have gone astray” (no. 26).

EX. 7-5A George Frideric Handel, duetto, No, di voi non vo’ fidarmi

In fashioning the chorus shown in Ex. 7-5b, Handel tossed the duet material as a unit between the high male/female pair (sopranos and tenors) and the low one (altos and basses). Only once, briefly, near the end, does Handel amplify the duet writing into a quartet by doubling both lines at consonant intervals. Elsewhere the choral tutti consists of a chordal outburst (“Wonderful Counsellor!”) that is newly composed for Messiah and caps every section of the chorus with a climax. In “All we like sheep,” we have another case where one of Handel’s happiest descriptive ideas (the wayward lines at “gone astray”) turns out to have been not composed but merely adapted to the words it so aptly illustrates.

EX. 7-5B Messiah, no. 12 (“For unto us a child is born”), mm. 1–14

The use of such material as the basis for an oratorio on the life of Christ has tended to bemuse those for whom the sacred and the secular are mutually exclusive spheres. One way of excusing the apparent blasphemy has been to declare that the duetti, composed during the summer of 1741, were actually sketches for Messiah, composed that fall, and that therefore the text was merely a matter of convenience—“little more than a jingle, words of no significance whatever, serving merely as a crystallizing agent for music which was later to be adapted to a text that had not even yet been chosen,” according to one squeamish specialist.13 Another writer, the influential nineteenth-century formalist critic Eduard Hanslick, used the apparent incongruity to argue that the expressive content of music was unreal, and that any music could plausibly go with any text!

These circumlocutions are easily refuted, for the esthetic discomfort that gave rise to them was not Handel’s. It is obvious, for one thing, that the main melody of “For unto us a Child is born” was modeled carefully on the Italian text, simply because the very first word of the English text is quite incorrectly set. (Say the first line to yourself and see if you place an accent on “for.”) But then, the texts (and, consequently the music) of the duetti will seem incongruous, something to be explained away, only if we regard Messiah as being church music, which it was not. Despite its embodying the sacredest of themes, it was an entertainment, and its music was designed to amuse a public in search of diversion, however edifying. The musical qualities of the duets, being delightful in themselves, could retain their allure in the new context and adorn the new text—and even, thanks to Handel’s “madrigalistic” genius, appear to illuminate its meaning.

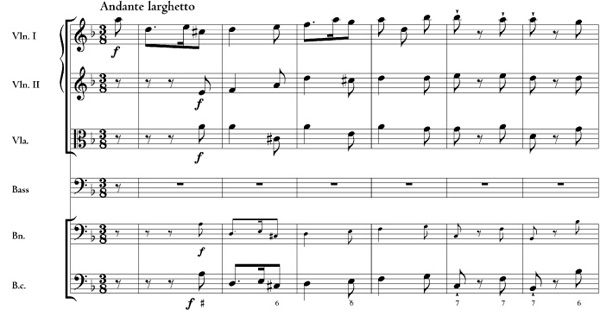

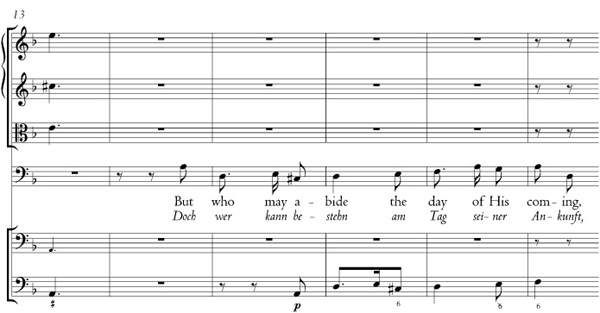

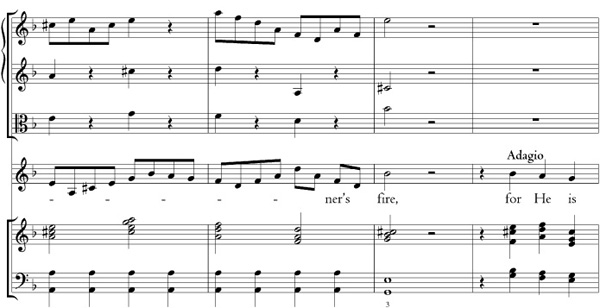

The character of the entertainment Messiah provided—in particular, the absence of any contradiction between the oratorio’s means and aims and those of the secular shows with which it originally competed—is also clarified by its performance history. The aria “But who may abide the day of His coming?” (no. 6) was originally assigned to the bass soloist, and like many oratorio arias, was cast in a direct and simple two-part form that harked back to the earlier style of Alessandro Scarlatti. The Scarlattian resonance is especially marked in this aria (Ex. 7-6a) because of its slowish (larghetto) gigue-like meter and its rocking siciliana rhythms, relieved only by some fairly perfunctory coloratura writing on the word “fire.”

In 1750, Handel replaced the bass aria with a new one for alto that retained the original beginning, but regarded the two halves of the text as embodying a madrigalian antithesis, requiring a wholly contrasting setting for the part that compares God to “a refiner’s fire.” Here the music suddenly tears into a duple-metered section marked Prestissimo, the fastest tempo Handel ever specified, heralded by string tremolos and reaching a fever pitch of vocal virtuosity. A return to the larghetto seems to mark the piece as an operatic da capo aria, but a second prestissimo, even wilder than the first, turns it into something quite unique in both form and impact (Ex. 7-6b).

One way of explaining the replacement is to regard the first version as unsatisfactory and the alteration as an implicit critique, motivated by sheer artistic idealism. In this variant, Handel, on mature reflection, decided that the aria demanded the change of range and character, and then went looking for the proper singer to perform it. If that is what happened, it was a unique occurrence in the career of a theatrical professional who always had to know exactly for whom he was writing in order to maximize his, and his singers’, potential effect.

In the case of “But who may abide,” he knew, and we know, for whom the new aria was intended: the alto castrato Gaetano Guadagni (1729–92), one of the great singers of the eighteenth century, who was then near the beginning of his career, and who had just come to England with a touring troupe of comic singers. Guadagni’s virtuosity, his histrionic powers, and his ability to improvise dazzling cadenzas had taken London by storm. Handel rushed to capitalize on his drawing power, transferring to him all the alto arias in Samson (his latest oratorio) and the perennial Messiah, and specially composing for Guadagni, in the form of the revised “But who may abide,” what his oratorios otherwise lacked: a true virtuoso showpiece for a castrato singer. “But who may abide” was the obvious candidate for this operation, since its “fire” motif gave Handel the opportunity to revert to his old operatic self and compose a simile aria in the old “rage” or “vengeance” mode typified by “Vivi, tiranno!” (Ex. 7-1).

EX. 7-6A Messiah, no. 6 (“But who may abide”), 1741 version, mm. 1–18

EX. 7-6B Messiah, no. 6 (“But who may abide”), 1750 version, m. 139–end

It has been the great showstopper in Messiah ever since. And it all at once erased the distinction between Italianate sissification and manly British dignity that the institution of the English oratorio was supposed to bolster. For here a symbol of “Italian-Continental degradation,”14 as the cultural historian Richard Leppert puts it (or what Lord Chesterfield, in his famous “Letters to His Son,” would call “that foul sink of illiberal vices and manners”15), was holding forth in the very midst of what had even by then become an official emblem of proud British piety.

Handel must have loved the moment. He was getting his own back in many ways. By hiring the latest divine “ragazzo” or Italian boy, he was getting his own back against Farinelli, who had so disastrously snubbed him. By scoring such a hit with his new aria di bravura he was vindicating the exotic entertainments he had been forced so long ago to give up. And by making the British public love the infusion of Italian manners into the quintessential British spectacle (for the original “Who May Abide” was never revived, although the British have often rather incongruously tried to give the florid alto version back to the cumbrous bass), he may have been taking a sweetly secret personal revenge on the stolid tastemakers who had forced him to deny his predilections in more ways than one—for as many scholars now agree, Handel, a lifelong bachelor, was probably what we would now call a closeted gay man.

But what chiefly mattered was the success. Again the old theatrical entrepreneur had seized the main chance. His protean nature, his uncanny ability continually to remake himself and his works in response to the conditions and the opportunities that confronted him—that was Handel’s great distinguishing trait. It marks him as perhaps the first modern composer: the prototype of the consumer-conscious artist, a great freelancer in the age of patronage, who managed to succeed—where, two generations later, Mozart would still fail—in living off his pen, and living well.

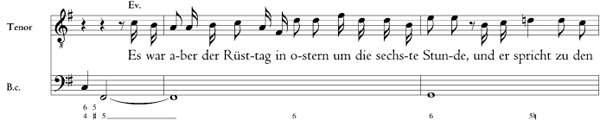

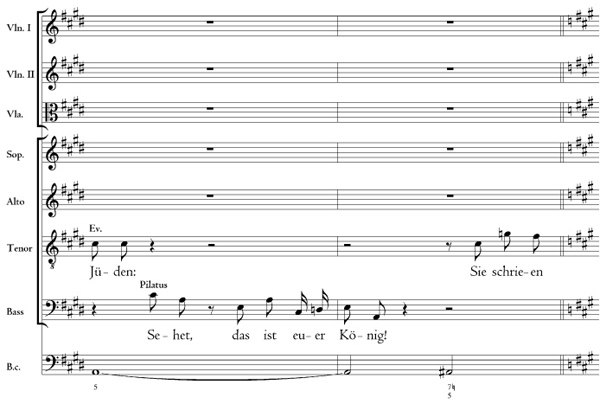

Turning back now to Bach, and to his very different world, we are ready to assess the music he and his coreligionists unanimously regarded as his major contribution. That music is his vocal music, composed to a large extent in forms familiar to us from our acquaintance with Handel’s operas and oratorios, but serving an entirely different audience and an entirely different purpose. With only the most negligible exceptions (birthday odes and the like) chiefly arising out of his Collegium Musicum activities or his nominal role as civic music director, Bach’s vocal music is actual church music.

We have seen in the previous chapters how even in his eminently enjoyable instrumental secular music, and in his sometimes monumentally thrilling keyboard music, Bach managed to insinuate an attitude of religious contempt for the world, the polar antithesis to Handel’s posture of joyous acceptance and enterprising accommodation. In his overtly religious vocal music we shall of course encounter that attitude in a far more explicit guise, even though it was often communicated through the outward forms of secular entertainment.

By the time of Bach’s Leipzig tenure even the music of the Lutheran church had made an accommodation with the music of the popular theater, and this new style of theatricalized music became Bach’s medium. Even though he never wrote an opera and maintained a lifelong disdain of what he called “the pretty little Dresden tunes” (Dresden being the nearest city with an opera theater, which Bach occasionally visited), Bach became a master of operatic forms and devices. But he managed—utterly, profoundly, hair-raisingly—to subvert them.

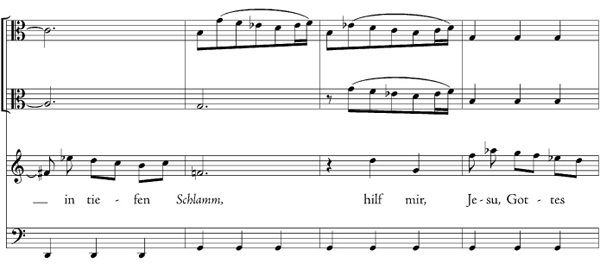

The forms of opera came to Lutheran music through the work of Bach’s older contemporary Erdmann Neumeister (1671–1756), a German poet and theologian, who revolutionized the form and style of Lutheran sacred texts for music. Traditionally, Lutheran church music, even at its most elaborate, had been based on chorales. By the 1680s a Lutheran “oratorio” style had been developed, in which chorales alternated with biblical verses and—the new ingredient—with little poems that reflected emotionally on the verses the way arias reflected on the action in an opera seria. This style was used especially for Passion music at Eastertime. Bach would write Passion cycles of this kind as well, more elaborate ones that reflected some of Neumeister’s innovations. In his early years (up to his stint at Weimar), Bach also wrote shorter sacred works in the traditional style, closely based on chorales and biblical texts.

FIG. 7-6 Erdmann Neumeister, the German religious poet who adapted the forms of Italian opera to the requirements of Lutheran church services.

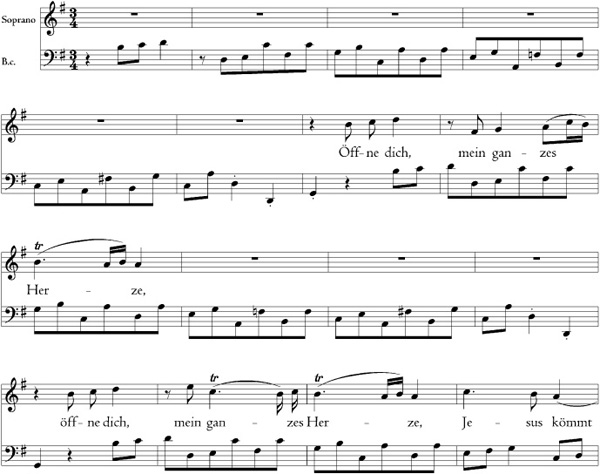

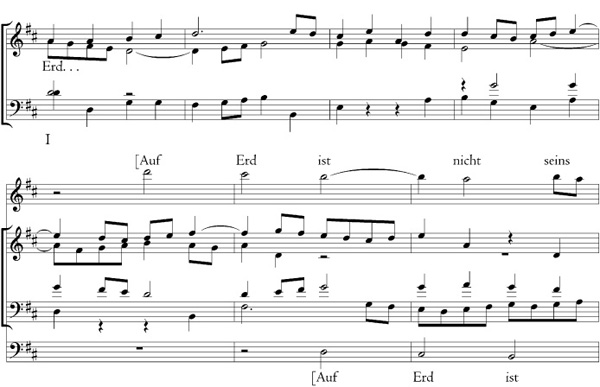

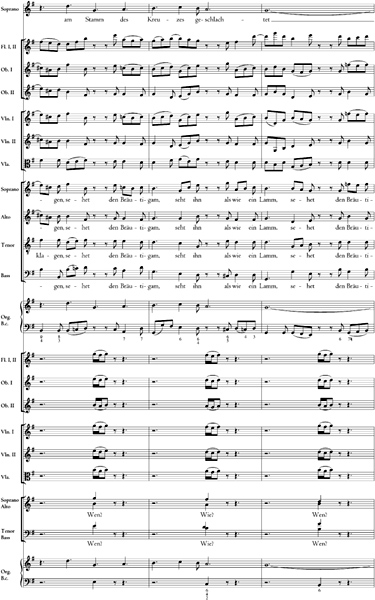

Around the turn of the century, Neumeister began publishing little oratorio texts in a new style, for which he borrowed the name of the Italian genre that had inspired him. Consisting entirely of vividly picturesque, “madrigalesque” verses, and explicitly divided into recitatives and arias, they were dubbed “cantatas” by their author, and they provided the prototype for hundreds of church compositions by Bach (who, however, continued to designate such pieces with mixed voices and instruments as “concertos,” retaining the term in use since the time of Schütz and the latter’s teacher, Gabrieli).

Neumeister’s cantata texts were published in a series of comprehensive cycles covering the Sundays and feasts of the whole church calendar, and they were expressly meant for setting by Lutheran cantors like Bach, whose job it was to compose yearly cycles of concerted vocal works according to the same liturgical schedule. Bach wrote as many as five cantata cycles during the earlier part of his stay at Leipzig, of which almost three survive complete. This remainder is still an impressive corpus numbering around 200 cantatas (a figure that includes the surviving vocal concertos from Bach’s earlier church postings). Only a handful of Bach’s surviving cantatas were composed to actual Neumeister texts, but the vast majority of them adhere to Neumeister’s format, mixing operalike recitatives and da capo arias with the chorale verses. Bach at Leipzig became, willy-nilly, a sort of opera composer.

But cantatas were reflective, not dramatic works. The singers of the arias were not characters but disembodied personas who “voiced” the idealized thoughts of the congregation in response to the occasion that had brought them together. Indeed, the Lutheran cantata could be viewed as a sort of musical sermon, and its placement in the service confirms this analogy.

The numbering system used for Bach’s cantatas has nothing to do with their order of composition. It was merely the order in which the cantatas were published for the first time, by the German Bach Society (Bach-Gesellschaft), in an edition that was begun in 1850, the centennial of Bach’s death. (The numbering was later taken over in a thematic catalogue called the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, published in the bicentennial year, 1950, and is now called the “BWV” listing.) Dating the Bach cantatas, as a matter of fact, has been one of the knottiest problems in musicology.

In dating a body of compositions like the Bach cantatas, one starts with those for which the date is fortuitously known thanks to the lucky survival of “external” evidence. One such is the Cantata BWV 61, on whose autograph title page Bach happened to jot down the year, 1714, which puts it near the middle of his Weimar period.

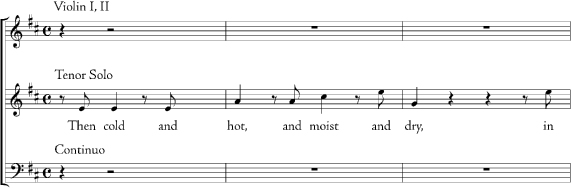

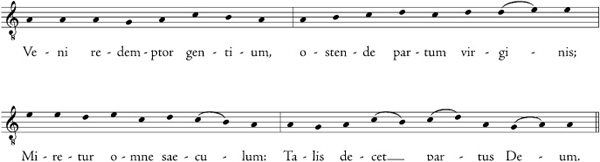

Cantata No. 61 also happens to be one of Bach’s few settings of an actual text by Neumeister, and it was probably the earliest of them. For all these reasons, it can serve us here as an model of the new “cantata” style, to set beside an older “chorale concerto.” It bears the title Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland—one of the most venerable Lutheran chorales (Ex. 7-7b), adapted by the Reformer himself from the Gregorian Advent hymn Veni, redemptor gentium (“Come, Redeemer of the Heathen”) (Ex. 7-7a). The cantata was composed for the first Sunday of Advent, the opening day of the liturgical calendar (in 1714 it fell on 2 December), and was therefore based on the opening text in one of Neumeister’s cycles, perhaps indicating that Bach was planning to set Neumeister’s whole book to music, as several of his contemporaries, including Telemann, did.

EX. 7-7A Gregorian hymn, Veni redemptor gentium

EX. 7-7B Chorale: Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

Now come, redeemer of the heathen, known as the Virgin’s child;

Let all the world marvel, that God chose such a birth.

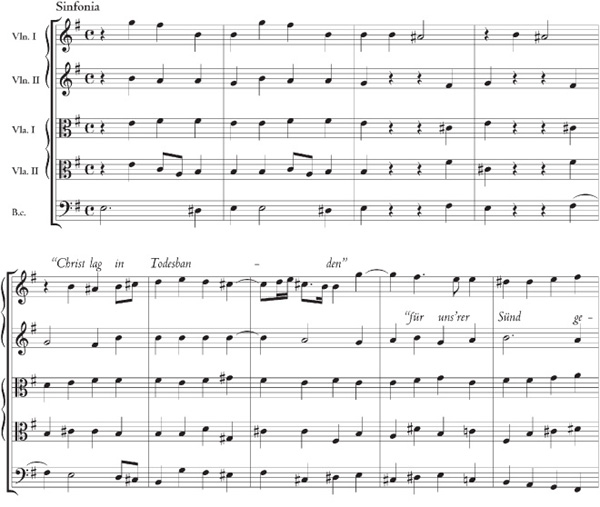

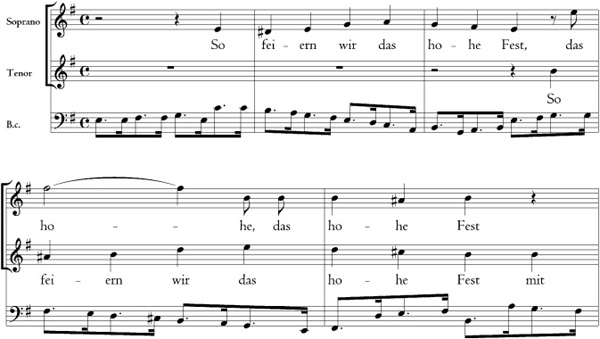

For its chorale-concerto counterpart, Cantata BWV 4, one of Bach’s earliest surviving cantatas but also one of the best known, would make an appropriate choice. First performed at Mühlhausen—possibly on Easter Sunday (24 April) 1707 as part of Bach’s application for the organist’s post there—it consists of a set of variations on another venerable chorale, Christ lag in Todesbanden (“Christ lay enchained by death”), which Luther had adapted from the Gregorian Easter sequence Victimae paschali laudes.

The text of Cantata no. 4 is exactly that of the chorale, its seven sections corresponding to the seven verses of the hymn, with a diminutive sinfonia introducing the first verse. That first verse setting is almost as long as the rest of the cantata put together. The sinfonia (Ex. 7-8a), which serves a kind of “preluding” function, is cleverly constructed out of materials from the chorale melody. The first line of the tune is quoted by the first violin in mm. 5–7; the second line, minus its cadential notes, is played by the second violin in mm. 8–10; the expected cadence is finally made by the first violins at the end. The first four measures are built on a neighbor-note motif derived from the melody’s incipit (first in the continuo, then in the first violins). The obsessive repetitions, a seeming stutter before the first line of the tune is allowed to progress, effectively suggest constraint—“death’s bondage.”

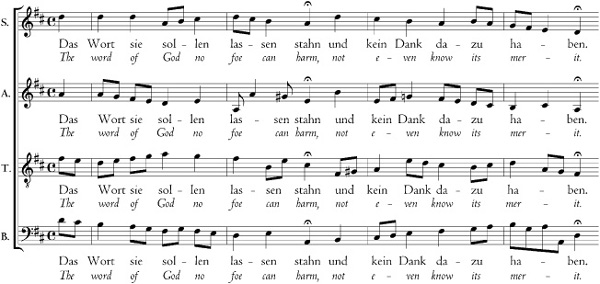

The elaborate first chorus is an old-fashioned cantus-firmus composition in “motet style,” in which the successive lines of the unadorned chorale tune in the soprano are pitted against points of imitation (some of them “Vorimitationen,” pre-echoes of the next line) in the accompanying voices. Although adapted here to a more modern harmonic idiom, and further complicated by the intensely motivic instrumental figuration (often drawn from the neighbor-note incipit), the procedure dates back in its essentials to the sixteenth century. By 1707 such a piece would have been considered entirely passé (or at best an exercise in stile antico) in any repertory but the Lutheran. For the final Hallelujah!, Bach livens things up by doubling the tempo and shifting over to an integrated motet style in which the soprano part moves at the same healthy speed as the rest of the choir. Still, the whole piece, like the church whose worship it adorned, fairly proclaims its allegiance to old ways.

And so does verse 2 (Ex. 7-8b), in which a somewhat “figural” version of the chorale melody in the soprano is shadowed by a somewhat freer alto counterpart, while the two sung parts are set over a ground bass the likes of which we have not seen, so to speak, since the middle of the seventeenth century. The style of verse 3, with its neatly layered counterpoint, is like that of an organ chorale prelude: the tenor sings the cantus firmus in the “left hand,” while the massed violins play something like a ritornello in the “right hand,” and the frequently cadencing continuo supplies the “pedal.” Verse 4 is perhaps the most old-fashioned setting of all. It is another cantus-firmus setting (tune in the alto) against motetlike imitations, with a very lengthy Vorimitation at the beginning that takes in two lines of the chorale. The continuo is of the basso seguente variety, following (in somewhat simplified form) the lowest sung voice whichever it may be, never asserting an independent melodic function of its own. This usage corresponds to the very earliest venetian continuo parts, circa 1600. Like the earliest Venetian “ecclesiastical concertos,” this verse could be sung a cappella without significant textural or harmonic loss. It is, in short, a bona fide example of stile antico.

EX. 7-8A J. S. Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, Sinfonia

EX. 7-8B J. S. Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, Verse II, mm. 1–8

By contrast, verse 5 (Ex. 7-8c), with its initial reference to the ancient passus duriusculus (chromatic descent) in the bass, shows how the chorale may be recast as an operatic lament, for which purpose Bach adopts a somewhat (though only somewhat) more modern stance. For the first time Bach relinquishes the neutral “common time” signature and employs a triple meter that has ineluctable dance associations. With its antiphonal exchanges between the singer and the massed strings (in an archaic five parts), this setting sounds like a parody of a passacaglia-style Venetian opera aria, vintage 1640, or (more likely) of an earlier German ecclesiastical parody of such a piece, say by a disciple of Schütz.

When, toward the end (Ex. 7-8d), the textual imagery becomes really morbid (blood, death, murderer, etc.), Bach seems literally to torture the vocal part, forcing it unexpectedly to leap downward a twelfth, to a grotesquely sustained low E on “death,” and leap up almost two octaves to an equally unexpected, even lengthier high D on “murderer,” while the violins suddenly break into a rash of unprecedented sixteenth notes. Comparing this tormented imagery with the jolly imagery we encountered in Handel’s Israel in Egypt (albeit equally grisly and violent, at times, in its subject matter), we may perhaps begin to note a widening gulf between the two masters of the “High Baroque.” It is an important point to ponder, and we will return to it.

on “death,” and leap up almost two octaves to an equally unexpected, even lengthier high D on “murderer,” while the violins suddenly break into a rash of unprecedented sixteenth notes. Comparing this tormented imagery with the jolly imagery we encountered in Handel’s Israel in Egypt (albeit equally grisly and violent, at times, in its subject matter), we may perhaps begin to note a widening gulf between the two masters of the “High Baroque.” It is an important point to ponder, and we will return to it.

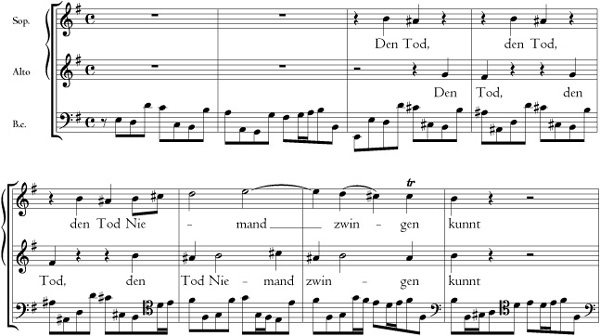

In verse 6, Bach expands the scope of his imagery to incorporate, possibly for the first time in his music, the characteristic regal rhythms of the French overture as a way of reflecting the meaning of So feiern wir (“So mark we now the occasion”), which connotes an air of great solemnity and ceremony (Ex. 7-8e). Later, when the singers break into “rejoicing” triplets, the dotted continuo rhythms are probably meant to align with them. (There was no way of indicating an uneven rhythm within a triplet division in Bach’s notational practice.)

EX. 7-8C J. S. Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, Verse V, mm. 1–12

The final verse (composed later for Leipzig, probably replacing a da capo repeat of the opening chorus) is set as a Cantionalsatz, or “hymnbook setting,” the kind of simple “Bach chorale” harmonization one finds in books meant for congregational singing. (The term was actually coined in 1925 by the musicologist Friedrich Blume, but it filled an annoying terminological gap and has been widely adopted.) Bach ended many cantatas with such settings (enough so that his son Carl Philipp Emanuel could publish a famous posthumous collection of 371 of them), and it is possible that the congregation was invited to join in. We do not know this for a fact, but it does make sense in terms of Leipzig practice as Bach once listed it, where “alternate preluding and singing of chorales” by the congregation customarily followed the performance of the “composition.”

EX. 7-8D J. S. Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, Verse V, 64–74

EX. 7-8E J. S. Bach, Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4, Verse VI, mm. 1–5

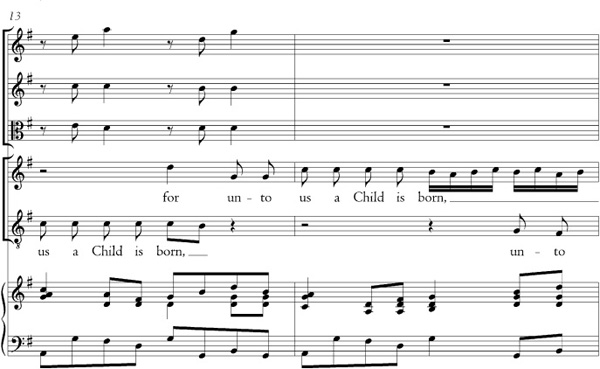

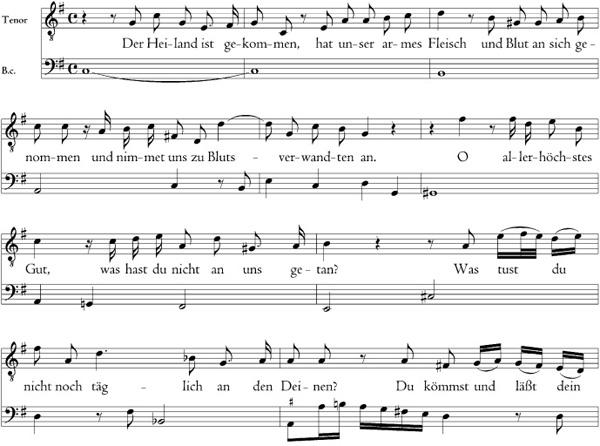

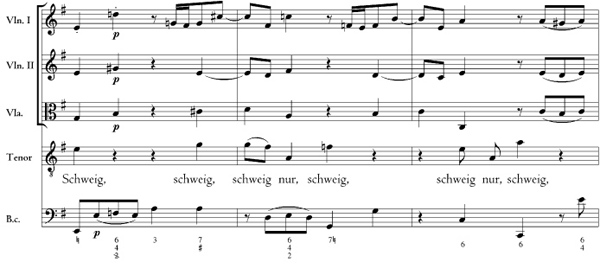

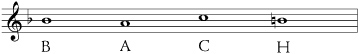

The text of Cantata no. 61 has the more varied structure prescribed by Neumeister, with “madrigals” (recitative-plus-aria texts) and biblical verses intermixed with the chorale stanzas. Such a text is more literally homiletic, or sermonlike, than the chorale concerto. In the present case, for example, only the first verse of the actual chorale is used; the rest is commentary. That single verse (Ex. 7-9a) is given a remarkable setting: not just in “French overture style” but as an actual French overture—a stately march framing a jiglike fugue—scored, as Lully himself would have scored it, for a five-part string ensemble (two violins, two violas, cello plus bassoon continuo) supporting the usual four-part chorus (perhaps even, in Bach’s own church performances, only one singer to a part). This unusual hybrid, the kind of thing we have learned to expect from Bach, resonates in multiple ways with the chorale’s text and the cantata’s occasion.

With respect to the text, the overture format gives Bach a way of emphasizing its most madrigalian aspect—the antithesis between the stately advent of Christ and the joyous amazement of mankind (marked gai, à la française) that greets him. By depicting Christ’s coming with the rhythms that accompanied the French king’s entrée, Bach effectively evokes Christ as King. Most notable of all is the absolute avoidance, in this first section, of choral counterpoint: a single line of the chorale is given a unison enunciation by each choral section in succession, and then they all get together for the second line in a “hymnbook” texture.

In this way the traditional, generic use of imitation in the fast middle section of the overture gains by way of contrast a symbolic dimension, evoking in its multiple entries a crowd of marveling witnesses. With respect to the cantata’s function, it has been suggested that by actually—and, from the liturgical point of view, gratuitously—labeling his chorus “Ouverture,” Bach meant to call attention to its placement at the very opening of the liturgical year. (Or else, conversely, the chorus’s placement at the beginning of the first Advent cantata may have prompted Bach’s choice of the Ouverture format.) Again, we are struck by the singlemindedness of Bach’s expressive purpose. For the sake of the affective contrast between the stern beginning and the “gay” continuation, he is willing to “harden” and distort the chorale melody on its every appearance with a dissonant, indeed downright ugly, diminished fourth. Such a choice reveals an altogether different scale of values from those of the ostensible model, the brilliant French court ballet. In fact, Bach appears deliberately to contradict, even thwart that brilliance with his dissonant melodic intervals and clotted texture.

EX. 7-9A J. S. Bach, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61, Overture, mm. 1–7

From the French court we now move to the Italian opera theater—or at least to the aristocratic Italian salon (where the original “cantatas” were sung)—for a tenor recitative and aria on a reflective text by Neumeister. But both the recitative and the aria differ enormously from any that we have encountered before. The recitative itself (Ex. 7-9b) ends with a little aria, where the bass begins to move (m. 10), and engages in imitations with the singer to point up the metaphorical “lightening” of the mood. This sort of lyricalized recitative, called mezz’aria (“half-aria”) in the Italian opera house, was a throwback to the fluid interplay of forms in the earliest operas and cantatas. By the eighteenth century it was a German specialty (and one of the ways, incidentally, in which Handel often betrayed his German origins in his Italian operas for English audiences).

EX. 7-9B J. S. Bach, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61, no. 2, recitativo

The aria (Ex. 7-9c), a sort of gloss on the word “Come” from the chorale, is a gracious invitation to Christ set as a lilting  gigue. The ritornello, unlike the Vivaldian type with its three distinct ideas, is all “spun out” of a single five-note phrase. It is played by the whole orchestra, massed modestly in a single unison line, creating with the voice and the bass a typical (that is, typically Bachian) trio-sonata texture. The singer’s entry would come as a surprise to connoisseurs of Italian opera, but not to connoisseurs of trio sonatas, for the voice enters with the same melody as the “ritornello” and spins out the same fund of motives. For this reason Bach can dispense with the lengthy instrumental ritornello on the da capo. Instead, he writes dal segno (“from the sign”), placing the sign at the singer’s entry, which fulfills the “return” function perfectly well. This hybridization of operatic and instrumental styles is rarely if ever encountered in the opera house but standard operating procedure in Bach’s cantatas.

gigue. The ritornello, unlike the Vivaldian type with its three distinct ideas, is all “spun out” of a single five-note phrase. It is played by the whole orchestra, massed modestly in a single unison line, creating with the voice and the bass a typical (that is, typically Bachian) trio-sonata texture. The singer’s entry would come as a surprise to connoisseurs of Italian opera, but not to connoisseurs of trio sonatas, for the voice enters with the same melody as the “ritornello” and spins out the same fund of motives. For this reason Bach can dispense with the lengthy instrumental ritornello on the da capo. Instead, he writes dal segno (“from the sign”), placing the sign at the singer’s entry, which fulfills the “return” function perfectly well. This hybridization of operatic and instrumental styles is rarely if ever encountered in the opera house but standard operating procedure in Bach’s cantatas.

EX. 7-9C J. S. Bach, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61, no. 3, aria, mm. 1–5, 17–21

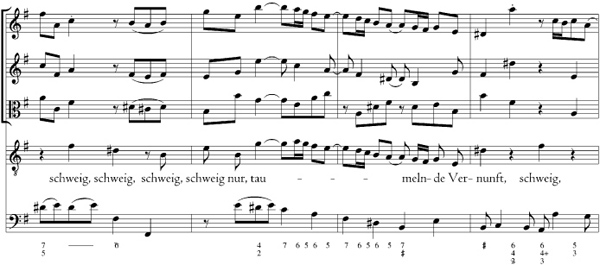

The next recitative/aria pair is of a kind equally rare in Italian cantatas or operatic scenes: the recitative is sung by one singer and the aria by another. That is because Neumeister has cast the recitative (Ex. 7-9d) as Christ’s answer to the invitation tendered in the previous aria. It is a biblical verse, sung by the bass, the only voice of sufficient gravity to impersonate the Lord. The singer emphasizes the word klopfe (“I knock”) in two ways, first by a short melisma, and then by a quick repetition. And that is our signal as to the reason for the curious accompaniment senza l’arco (“without the bow,” or pizzicato in more modern, standard parlance). The periodic plucked chords (with a top voice that is as stationary as Bach could make it) are Bach’s way of rendering Christ’s knocking at the church door.

EX. 7-9D J. S. Bach, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61, no. 4, recitativo, mm. 1–4

The soprano aria (Ex. 7-9e), sung by a disembodied soul-voice to its heart, is the Christian’s answer to Christ’s knock. Scored for voice and continuo only, it is an even more modest aria than the one before. Again the two parts share melodic material. Although only the motto phrase (“Open ye!”) is obviously repeated when the voice enters, the whole vocal melody turns out on analysis to be a simplified version of the cello’s ritornello, shorn of the gentle string-crossings. The fact that the singer’s part is simpler than its accompaniment—especially when the high range of the part is taken into account—is already proof that although an operatic form has been appropriated, we are worlds away from the theater.

Indeed, soprano arias are likely to be the least adorned of all (and therefore especially suitable for “heartfelt” emotions, as here) because they were sung not by a gaudy castrato or a haughty prima donna but by a choirboy. (As in the Catholic church, so in the Lutheran, only male voices could be heard within its walls.) A Bach soprano aria, even one as simple as this one, was likely to strain the vocal and musicianly resources of the boy called upon to sing it. And yet when the text required it, Bach did not hesitate to write very difficult parts for the boys he trained.

EX. 7-9E J. S. Bach, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61, no. 5, aria, mm. 1–16

Nor did he hesitate to write music of utter magnificence, despite the wan forces at his disposal. Undoubtedly his most splendid cantata was BWV 80, written at Leipzig for performance on the Feast of the Reformation, 31 October 1724. (Several of its parts were based on a much smaller cantata written at Weimar.) The Reformationsfest, as it is called in German, is the anniversary of the famous Ninety-five Theses, or articles of protest, which Luther posted on the door of the Castle Church at Wittenberg, 31 October 1517. It is thus the most important feast day specific to the German Protestant church and is always given a lavish celebration.