The earliest public critics were motivated by a concept or ideal called romanticism—an easy thing to spot in a writer or an artist, but notoriously difficult to define. And that is because romanticism was (and is) no single idea but a whole heap of ideas, some of them quite irreconcilable. Yet if it has a kernel, that kernel can be found in the opening paragraphs of a remarkable book that appeared in Paris in 1782 under the title Confessions—the last and (he thought) crowning work of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. “I am commencing an undertaking,” he wrote,

hitherto without precedent, and which will never find an imitator. I desire to set before my fellows the likeness of a man in all the truth of nature, and that man myself.

Myself alone! I know the feelings of my heart, and I know men. I am not made like any of those I have seen; I venture to believe that I am not made like any of those who are in existence. If I am not better, at least I am different. Whether Nature has acted rightly or wrongly in destroying the mould in which she cast me, can only be decided after I have been read.1

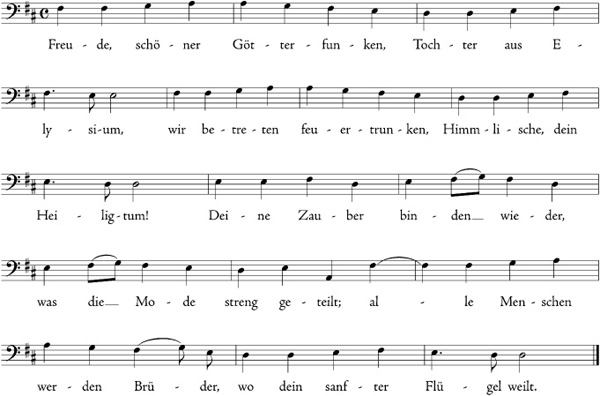

To be romantic meant valuing difference and seeking one’s uniqueness. It meant a life devoted to self-realization. It meant believing that the purpose of art was the expression of one’s unique self, one’s “original genius,” a reality that only existed within. The purpose of such self-expression was the calling forth of a sympathetic response; but it had to be done “disinterestedly,” for its own sake, out of an inner urge to communicate devoid of ulterior motive. It was that, and that alone, that could provide a truly “esthetic” experience (as defined by the philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, who coined the term in his treatise Aesthetica of 1750), as distinct from an intellectual or an ethical one. The only musical works we have encountered so far that could conceivably satisfy these requirements were the late symphonies of Mozart, described in the previous chapter. Not coincidentally, then, Mozart became for the critics of his own time and shortly thereafter the first and quintessential romantic artist, the more so since music was widely regarded as the most essentially romantic of all the arts.

What made it so, according to E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), the most influential music critic of the early nineteenth century, was not merely the power of music to engage the emotions, but rather the “fact” (as Hoffmann felt it to be) that “its sole subject is the infinite.”2 Precisely because music, unlike painting or poetry, has no necessary model in nature, it “discloses to man an unknown realm, a world that has nothing in common with the external sensual world that surrounds him, a world in which he leaves behind him all definite feelings to surrender himself to an inexpressible longing.” In opposition to “the external sensual world,” then, music provides access to the inner spiritual world—but only if it resists all temptation to represent the outer world.

FIG. 12-1 E. T. A. Hoffmann, self-portrait (ca. 1822).

Thus, for romantics, instrumental music was an altogether more exalted art than vocal. This, too, was a novel idea, perhaps only even thinkable since Haydn’s time. Rousseau himself, as we know, was of the opposite view, quoting Fontanelle’s exasperated cry—“Sonate, que me veuxtu?” (“Sonata, what do you want from me?”)—with approval, and adding that a taste for “purely harmonic” (i.e., instrumental) music was an “unnatural” taste. Even Kant, the greatest early theorizer of esthetics, thought instrumental music at once the pleasantest art and the least “cultured,” since “it merely plays with sensations.”3 For Hoffmann, though, writing in 1813, the shoe was on the other foot. Words, for him, were the inferior element—by nature representational, hence merely “external.” They pointed outside themselves, while music pointed within. Music, he allowed, definitely improved a text—“clothing it with the purple luster of romanticism”—but that was only because its inherently spiritual quality rendered our souls more susceptible to the externally motivated (hence, more ordinary, less artistic) emotions named by the poem.4 The poem was transformed by union with music, but the music was inhibited by the poem. Eventually, wrote Hoffmann, music “had to break each chain that bound it to another art,” leaving the other arts bereft and aspiring, in the words of Walter Pater, a latter-day romantic critic, “towards the condition of music.”5

That condition is the condition of autonomous, “absolute” spirituality and expressivity. The whole history of music, as Hoffmann viewed it, was one of progressive emancipation of music from all bonds that compromised the autonomy and absoluteness of expression that Hoffmann took to be its essence. “That gifted composers have raised instrumental music to its present high estate,” he wrote, is due not to the superior quality of modern instruments or the superior virtuosity of modern performers.6 It is due solely to modern composers’ “more profound, more intimate recognition of music’s specific nature.” The composer and the performing virtuoso were henceforth cast in opposition; virtuosity was just one more bond, one more tie to the external world, from which true music had to be emancipated.

All of this was utterly contrary to earlier notions of musical expression, which were founded staunchly on the ancient doctrine (stated most comprehensively by Aristotle) that art imitates nature. That doctrine had itself brought about a revolution in musical expression in its time, the sixteenth century, when musicians discovered the writings of ancient Greece and began, in madrigals and (later) in opera, to devise the “representational style” (stile rappresentativo) so as directly to imitate speech and, through it, the emotions expressed by speech. Like the later doctrine of affections, the stile rappresentativo was at the opposite pole from romantic notions of untrammeled musical expressivity.

For one thing, it depended on alliance with words—another art. For another, it expressed not the unique feelings of the composer but the archetypical feelings of characters, and hence emphasized general “human nature” as an object of representation, not the uniqueness of an individual self as an object of expression. For a third, it dealt with particular objectified categories of feeling that had names, that could be (and were) classified and catalogued, that were the common property of humanity. It was powerless to summon up the verbally inexpressible, the ineffable, the metaphysical or “infinite.” Hence, it could communicate only through a repeatable process of objective intellectual cognition (or recognition), not transcendent subjective inspiration. It was not an absolute art, let alone an autonomous or emancipated one. It dealt in the common coin of shared humanity, not the elite currency of genius.

The “gifted composers” or geniuses to whom music owed its emancipation, Hoffmann declared, were Mozart and Haydn, the first true romantics. As “the creators of our present instrumental music,” they were “the first to show us the art in its full glory.”7 But whereas Haydn “grasps romantically what is human in human life,” Mozart reveals “the wondrous element that abides in inner being.” Haydn, albeit with unique aptitude and empathy, manifests a general humanity, what Kant called the sensus communis—thoughts and feelings common to all (“all men,” as people put it then), thus capable of fostering social union. Haydn is therefore “more commensurable” with ordinary folk, “more comprehensible for the majority.” His art is democratic, in the spirit of Enlightenment.

Mozart, by contrast, expresses for Hoffmann something essential, ineffable, unique. His music “leads us into the heart of the spirit realm”—or those of “us,” anyway, who are equipped (like Tamino, the hero of The Magic Flute) to make a spiritual journey. It springs, like all true romantic art, from an “attempt to transcend the sphere of cognition, to experience higher, more spiritual things, and to sense the presence of the ineffable.”8 That is the definition of romanticism given around 1835 by Gustav Schilling (1803–81), a German lexicographer.

For all these reasons Mozart’s music, unlike Haydn’s, gives rise not only to bliss but to fear and trembling, and to melancholy as well. To sum it all up in a single pair of opposing words, it was Mozart, according to Hoffmann and his contemporaries, who made the crucial romantic breakthrough—from the (merely) beautiful to the sublime.

We are perhaps no longer as sensitive to this distinction as were the theorists of romanticism. We may tend nowadays to interchange the words “beautiful” and “sublime” in our everyday language, perhaps even in our critical vocabulary. To say “Haydn’s music is beautiful” may not seem to us to be very different in meaning or intent from saying “Mozart’s music is sublime.” It may even seem to us like a way of pairing or equating the two. But to a romantic, it meant radically distinguishing them. And that is because, from about the middle of the eighteenth century to about the middle of the nineteenth, the words were held to be virtual opposites.

FIG. 12-2 Caspar David Friedrich, Moonrise on an Empty Shore (1839). Friedrich’s eerily lit landscapes often summon up moods of sublime immensity comparable to the “infinite longing” Hoffmann named as the latent subject matter of romantic art.

For the English philosopher and statesman Edmund Burke (1729–97), writing in 1757 under the influence of Kant (whom he influenced in turn), they presented “a remarkable contrast,” which he detailed as follows:

Sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones comparatively small: beauty should be smooth and polished; the great is rugged and negligent;… beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and even gloomy: beauty should be light and delicate; the great ought to be solid and even massive. They are indeed ideas of a very different nature, one being founded on pain, the other on pleasure.9

This was, indeed, if not something new then at least something so old and forgotten as to seem new again: art founded on pain. Not since J. S. Bach have we encountered any notion that music should be anything but beautiful, and never have we encountered such a notion with reference to secular music. It implies an enormous change in the artist’s attitude toward his audience; and this, too, is a crucial component in any adequate definition of romanticism. The history of music in the nineteenth century—at any rate, of a very significant portion of it—could be written in terms of the encroachment of the sublime upon the domain of the beautiful, of the “great” upon the pleasant. And the process of encroachment applies to retrospective evaluation as well, as we are in the process of discovering where Mozart is concerned.

By characterizing Mozart’s art as being “more an intimation of the infinite” than Haydn’s, moreover, Hoffmann was implying (and claiming as one of its values) that it was inaccessible to the many. Romanticism, at least Hoffmann’s brand of it, was profoundly elitist and anti-egalitarian. It was an agonized reaction to the “universalist” ideals of the Enlightenment, a recoil by thinkers (especially in England and Germany) who viewed the French Revolution and the disasters that ensued—regicide, mob rule, terror, mass executions, wars of Napoleonic conquest—as the bitter harvest of an arrogant Utopian dream. Indeed, the man who gave this opinion its most memorably eloquent expression was none other than Edmund Burke, our erstwhile theorist of the sublime, in his Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790, and the even more embittered Letters on a Regicide Peace of 1795–97.

Examples of “painful” music are common enough in opera. The second-act finale of Mozart’s Don Giovanni will surely come to mind in this connection, with its “devastating opening chords” that (in the words of Elaine Sisman, a perceptive writer on the musical sublime) “intensify almost unbearably the music of the overture by substituting the chord on which the Commendatore had been mortally wounded in the [Act I] duel.”10 The graveyard scene from the same opera had inspired actual “horror” in a contemporary reviewer, who commented that “Mozart seems to have learned the language of ghosts from Shakespeare.”11 Interestingly enough, Mozart, while working on Idomeneo, his most unremittingly serious opera, found fault with that very aspect of Shakespeare, commenting that “if the speech of the ghost in Hamlet were not so long it would be more effective.”12 He twice revised the trombone-laden music representing the terrifying subterranean voice of Neptune in Idomeneo—from seventy measures, to thirty-one, all the way down to nine—so as to achieve a proper sense of awe-inspiring shock, or (in a single word) sublimity.

But these were not the passages in Mozart that inspired Hoffmann to call him romantic, nor did even Haydn’s overwhelming Representation of Chaos in The Creation, culminating in the famous burst of divine illumination, qualify for that honor. The latter was undeniably a sublime achievement. Schilling, the lexicographer, actually referred to it in his definition of das Erhabene (the sublime) in music, although that may have been because the opening words of the Book of Genesis were themselves often cited as the greatest of all models for sublime rhetoric.13

But there was a crucial difference between the sublime as represented in The Creation and the sublime as prized by romantics. Haydn’s representation, like any representation, had a cognizable object, a fixed content that emanated from words, not music. Hence it was an example of “imitation” rather than expression, and therefore, to romantics, not romantic. For a mere imitation to venture intimations of the sublime could strike a romantic critic as a ridiculous misuse of music. “At Vienna, I heard Haydn’s Creation performed by four hundred musicians,” wrote Mme. de Staël, an exile from revolutionary France, in her travel memoir De l’Allemagne (From Germany; 1810):

It was an entertainment worthy to be given in honor of the great work which it celebrated; but the skill of Haydn was sometimes even injurious to his talent: with these words of the Bible, “God said let there be light, and there was light,” the accompaniment of the instruments was at first very soft so as scarcely to be heard, then all at once they broke out together with a terrible noise as if to express the sudden burst of light, which occasioned a witty remark “that at the appearance of light it was necessary to stop one’s ears.” In several other passages of the Creation, the same labor of mind may often be censured.14

In this censure one can hear the authentic voice of early romanticism. It was not for The Creation, after all, that Hoffmann valued Haydn, but for his untitled instrumental works—works of ineffable content but powerful expressivity. That uncanny combination was the result of inspiration, and called forth inspiration from the listener.

The reason why Mozart was thought of—first in his day and then, more emphatically, in Hoffmann’s—as the most romantically sublime of composers had to do, in the first place, with the discomfort of sensory overload. “Too many notes, my dear Mozart” complained the emperor in the famous story, and in so doing reacted to what Immanuel Kant called the “mathematical sublime,” the awe that comes from contemplating what is countless, like the stars above.15 The “difficulty” of Mozart’s instrumental style was most spectacularly displayed, perhaps, in the densely grandiose fugal finale to his last symphony (in C major, K. 551), a movement that created, without recourse to representation, the same sort of awe that godly or ghostly apparitions created in opera. And that is why the symphony was nicknamed Jupiter (by J. P. Salomon, Haydn’s promoter, as it happens). That awe was the painful gateway to the beatific contemplation of the infinite, the romantics’ chosen work.

Nowadays it is conventional, of course, to call Mozart and Haydn “classic” composers rather than “romantic” ones, and even to locate the essence of their “classicism” in the “absoluteness” of their music (construing “absoluteness” here to imply the absence of representation). This is due, in part, to a changed perspective, alluded to at the end of the previous chapter, from which we now tend to look back on Mozart-and-Haydn as the cornerstone of the permanent performing repertory or “canon,” and “classic” is another way of saying “permanent.” As early as 1829, the author of a history of romanticism recognized that in music more than in any other art, everything takes on a “classic” aspect as it ages: “As far as we are concerned,” wrote F. R. de Toreinx (real name Eugène Ronteix), “Paisiello, Cimarosa and Mozart are classics, though their contemporaries regarded them as romantics.”16

But there was more to it than that. Historical hindsight eventually led to a new periodization of music history that came into common parlance around 1840, parsing the most recent phase of that history into a “Classical” period and a “Romantic” one, with the break occurring around 1800. One of the earliest enunciations of this dichotomy, for a long time almost universally accepted by historians, was an essay, “Classisch und Romantisch” (1841), by Ferdinand Gelbcke (1812–92). The music of the late eighteenth century was a “Classical art” for Gelbcke because like all classical art it was “object-centered, contemplative rather than expressive,” and—cliché of clichés!—because it struck a balance between form and content (or as Gelbcke put it, “between the art which shapes it and the material that is to be shaped”).17 Mozart, for Hoffmann a dangerous and “superhuman” (i.e., sublime) artist, was by Gelbcke’s time the very epitome of orderly values:

That composure, that peace of mind, that serene and generous approach to life, that balance between ideas and the means of expression which is fundamental to the superb masterpieces of that unique man, these were the most blessed and fruitful characteristics of the age in which Mozart lived, characteristics that we have imperceptibly yet gradually lost.18

The view may be anachronistic, and it is surely forgetful of romanticism’s original import (to say nothing of the actual conditions of Mozart’s life). But like “Gregorian chant” or “English horn,” the misnomer “Classical period”—corresponding exactly to what the earliest romantic critics called the earliest romantic phase of music—may be too firmly ensconced in the vocabulary of musicians to be dislodged by mere factual refutation. Nor is it without its own historical truth, so long as we remember that what we now call “classical” virtues, especially the virtues of artistic purity and self-sufficiency, are really romantic values in disguise.

Calling them “classical” expresses the nostalgia—an altogether “romanticized” nostalgia—that the artists and thinkers of post-Napoleonic Europe felt for the imagined stability and simplicity of the ancien régime. Gelbcke, unlike many later writers, makes no attempt to conceal his idyllic hankering for a bygone time he never knew. “When the Austrian Empire enjoyed a golden era of security, power, prosperity and peace under the reign of the Emperor Joseph II,” he mused rhetorically,

was this not the age of Haydn and Mozart? Although the storms were brewing elsewhere, within the Austrian Empire, nothing transpired to disturb the calm. So it was that both great composers were free to develop those qualities that have already been mentioned in connection with Mozart, qualities that they derived above all from the spirit of the age in which they lived.19

FIG. 12-3 Sketches of Beethoven by L. P. A. Burmeister (Lyser), published with his signature bytheprintmakerE.H.Schroeder.

Like so many distinctions that try to pass themselves off as “purely” artistic, the Classic/Romantic dichotomy thus has a crucial political subtext. “Classic” was the age of settled aristocratic authority; “romantic” was the age of the restless burgeoning bourgeoisie. Yet even without looking beyond the boundaries of music, no one in the nineteenth century could evade the sense that a torrential watershed had intervened between the age of Mozart and Haydn and the present. Even Hoffmann, writing a generation before Gelbcke, acknowledged that a momentous metamorphosis had taken place, although he saw it as a culmination of a prior “romantic” tendency rather than a break with a “classic” one. A difference of degree can be so great, nevertheless, as to be tantamount to a difference in kind, and so it was for Hoffmann when he compared the work of Mozart and Haydn, “the creators of our present instrumental music,” with that of “the man who then looked on it with all his love and penetrated its innermost being—Beethoven!”20

The enthusiastic quote comes from Hoffmann’s essay, “Beethoven’s Instrumental Music,” published in 1814 but based on articles and reviews written as early as 1810—and so do most of the other quotations from Hoffmann given above. Even as he waxed ardent about Mozart’s romanticism and Haydn’s, Hoffmann did so in the knowledge that they had been surpassed in all that made them great. Hoffmann’s characterization of Beethoven, taken in conjunction with his analytical writings about several of Beethoven’s works, does far more than reflect the romantic viewpoint of 1814. Hoffmann’s view of Beethoven reflects assumptions about art and artists that have persisted ever since—ideas to which practically all readers of this book will have been exposed, and to many of which they will have subscribed, even readers who have never read a single word about Beethoven, or (for that matter) about music.

Ideas received in this way—informally, unconsciously, from “the air,” without knowledge of their history (or even that they have a history)—are likely to be accepted as “truths held to be self-evident.” In this way, Hoffmann’s “Beethoven” stands for a great deal more than just Beethoven. It stands for the watershed that produced the modern musical world in which we all now live. To learn about it will be in large part to learn about ourselves. Before we can adequately understand Beethoven, then, or indeed anything that has happened since, we will need to know more about “Beethoven.”

To begin with, Hoffmann’s “Beethoven” was the idea of the romantic (or Kantian) sublime multiplied to the nth power. “Beethoven’s music,” Hoffmann raved,

opens up to us the realm of the monstrous and the immeasurable. Burning flashes of light shoot through the deep night of this realm, and we become aware of giant shadows that surge back and forth, driving us into narrower and narrower confines until they destroy us—but not the pain of that endless longing in which each joy that has climbed aloft in jubilant song sinks back and is swallowed up, and it is only in this pain, which consumes love, hope, and happiness but does not destroy them, which seeks to burst our breasts with a many-voiced consonance of all the passions, that we live on, enchanted beholders of the supernatural!21

The purpose of art, then, is to grant us an intensity of experience unavailable to our senses, and even (unless we too are geniuses) to our imaginations. But that intensity, to be felt at maximum strength, must be unattached to objects. It must be realer than what is merely present to the senses and nameable. Thus,

Beethoven’s music sets in motion the lever of fear, of awe, of horror, of suffering, and wakens just that infinite longing which is the essence of romanticism. He is accordingly a completely romantic composer, and is not this perhaps the reason why he has less success with vocal music, which excludes the character of indefinite longing, merely representing emotions defined by words as emotions experienced in the realm of the infinite?

The process whereby the great displaces the pleasant as the subject and purpose of art is well under way. And therefore, Hoffmann notes with perhaps a trace of an aristocratic smirk, “the musical rabble is oppressed by Beethoven’s powerful genius; it seeks in vain to oppose it.” But mere musicians, be they ever so learned in the craft of their profession, fare no better:

Knowing critics, looking about them with a superior air, assure us that we may take their word for it as men of great intellect and deep insight that, while the excellent Beethoven can scarcely be denied a very fertile and lively imagination, he does not know how to bridle it! Thus, they say, he no longer bothers at all to select or to shape his ideas, but, following the so-called daemonic method, he dashes everything off exactly as his ardently active imagination dictates it to him.

While a romantic artist inevitably makes a demoniac impression, Hoffmann goes on to assert, a true genius can be “unbridled” in effect yet at the same time fully in control of his method. Discerning that control where others miss it is the function of the critic. A critic, he implies, can be inspired, too. He, too, can be a genius.

The truth is that, as regards self-possession, Beethoven stands quite on a par with Haydn and Mozart and that, separating his ego from the inner realm of harmony, he rules over it as an absolute monarch. In Shakespeare, our knights of the aesthetic measuring-rod have often bewailed the utter lack of inner unity and inner continuity, although for those who look more deeply there springs forth, issuing from a single bud, a beautiful tree, with leaves, flowers, and fruit; thus, with Beethoven, it is only after a searching investigation of his instrumental music that the high self-possession inseparable from true genius and nourished by the study of the art stands revealed.22

What all of this amounts to is the idea, fundamental to the modern concept and practice of “classical music,” of the lonely artist-hero whose suffering produces works of awe- inspiring greatness that give listeners otherwise unavailable access to an experience that transcends all worldly concerns. “His kingdom is not of this world,” declared Hoffmann in another essay on Beethoven, making explicit reference to the figure regarded by Christians as the world-redeeming Messiah. And indeed, the romantic view was in essence a religious, “sacralizing” view. It was literally an article of faith to romantics that theirs was a specifically Christian idea of art—intent, like the Christian religion, on eternal values and on an intensity of experience that (as Schilling put it) might “transcend cognition” so that its communicants would “experience something higher, more spiritual.” Therein lay the difference between romantic art and all previous art, even (or especially) that of classical antiquity. The beauty of all pre-Christian art was a materialistic beauty, as pagan religion was a materialistic religion. Its “classic” proportions and pleasing grace, inspiring though they had been to artists ever since the humanist revival, were hedonistic virtues, expressive of nothing (to quote Schilling once more) beyond a mere “refined and ennobled sensuality.” Beauty, in the name of the new art-religion, had to give way before greatness. From now on music expressive of the new world-transcending values would be called not beautiful music but “great music.” It is a term that is still preeminently used to describe—or at least to market—“classical music,” and Beethoven is still its standard-bearer.

The newly sacralized view of art had immense and immediate repercussions on all aspects of daily musical life. Great works of music, like great paintings, were displayed in specially designed public spaces. The concert hall, like the museum, became a “temple of art” where people went not to be entertained but to be uplifted. The masterworks displayed there were treated with a reverence previously reserved for sacred texts. Indeed, the scores produced by Beethoven were sacred texts, and the function of displaying them took on, at the very least, the aspect of curatorship—and at the highest level, that of a ministry.

Where previously, as Carl Dahlhaus (1928-89) once memorably put it, the written text of a musical composition was “a mere recipe for a performance,” it now became an inviolable authority object “whose meaning is to be deciphered with exegetical interpretations.”23 By invoking the concept of exegesis—scriptural commentary—Dahlhaus once again draws attention to the parallel between the new (or “strong”) concept of art and that of religion. Music, because of its abstract or “absolute” character, required the most exegesis. It therefore became the art-religion par excellence, and provided the most work for an art-ministry—that is, criticism. Where previously the work served the performer, now the performer, and the critic too, were there to serve the work.

The scores of earlier “canonical” composers came to be treated with a similar reverence. But here the new treatment contrasted, and in some ways even conflicted, with the way such older works had been treated when they were new. Mozart did not scruple to alter his works in performance in order to please his audience with spontaneous shows of virtuosity, and neither did his contemporaries. Not only Mozart, but all performers of concertos and arias in his time improvised their passagework, “lead-ins,” and cadenzas, and were considered remiss or incompetent if they did not. For them scores, even (or especially) their own scores, were “mere recipes,” blueprints for flights of fancy, pretexts for display. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, however, spontaneous performance skills began to lose their prestige in favor of reverent curatorship.

Musicians were now trained (at conservatories, “keeping” institutions) to reproduce the letter of the text with a perfection no one had ever previously aspired to, and improvisation was neglected if not scorned outright. By the late nineteenth century, most instrumentalists played written-out cadenzas to all canonical concertos from memory; the cadenzas were now just as “canonical” as the rest of the piece. Beginning with Beethoven, composers actually set them down in their scores, expecting performers to reproduce them scrupulously. Nowadays, it is only the most exceptional pianist who has the wherewithal to improvise a cadenza, and those who do have it are as likely to be censured for their impertinence as praised for their know-how.

Improvisation skills have not died out by any means, but they have been excluded from the practice of “classical music.” They continue to thrive only in nonliterate or semiliterate repertories such as jazz and what is now called “pop” or popular music, a concept that did not exist until “classical music” was sacralized in the nineteenth century.

If sacralization implied inhibition of spontaneous performer behavior, that is nothing compared with the constraints that were imposed on audiences, who were now expected (and are still expected) to behave in concert halls the way they behaved in church. Recalling Mozart’s own description of the audience that greeted his Paris symphony with spontaneous applause wherever the music pleased them (as audiences still do when listening to pop performers), it is hard to avoid a sense of irony when contemplating the reverent passivity with which any audience today will receive the same symphony. Concert programs now even contain guides to “concert etiquette” in which new communicants at the shrine can receive instruction in the faith. One that appeared in New York “stagebills” during the 1980s even affected a parody of biblical language. When attending a concert, it reads:

Thou Shalt Not:

Talk …

Hum, Sing, or Tap Fingers or Feet …

Rustle Thy Program …

Crack Thy Gum in Thy Neighbors’ Ears …

Wear Loud-Ticking Watches or Jangle Thy Jewelry …

Open Cellophane-Wrapped Candies …

Snap Open and Close Thy Purse …

Sigh With Boredom …

Read …

Arrive Late or Leave Early …

This is only the latest version of a mode of discourse that began with critics like E. T. A. Hoffmann around 1810. As musicians and music lovers, we still live under the iron rule of romanticism.

Was Beethoven really responsible for all of this? Only in the sense that things were said and done in his name that, were it not for him, would have been said and done in the name of others, and perhaps differently. He became the protagonist and the beneficiary of an attitude that had been growing for almost half a century by the time he began making a name for himself, and that ultimately reflected changing social and economic conditions over which he had no more control than any other musician. His music was clearly affected by it; if it had not existed he would have composed very differently (in all likelihood more like Mozart). But by the force of his career and his accomplishments, and by the commanding mythology that grew up around his name, he mightily affected it in turn; without him it might not have achieved the authority his powerful example conferred upon it. In the “Beethoven watershed” we have one of the clearest examples of symbiosis between a powerful agent and the intellectual milieu in which he thrived.

FIG. 12-4 The house in Bonn where Beethoven was born.

In some important respects Beethoven shaped his time (and ours) in ways he could never have intended. He was born, on 16 December 1770, into a transplanted Flemish family of court musicians, like the Bachs but far less prestigious. His grandfather and namesake, Louis van Beethoven (1712–73), after occupying positions in several Belgian cities, accepted a singer’s post at the minor Electoral court of Bonn, a smallish city on the Rhine (later the capital of the Federal Republic of Germany or “West Germany”), where he changed his name to Ludwig and in 1761 acceded to the Kapellmeistership, a position to which his son Johann, the composer’s father, did not measure up.

The younger Ludwig was originally groomed for a career in the family mold. By the age of twelve, after establishing a local reputation as a piano prodigy, he was appointed assistant to the Electoral court organist. At eighteen, he took over some of his father’s duties as singer and instrumentalist. His first important compositions date from 1790, when he was nineteen: a cantata on the death of his employer’s elder brother, the emperor Joseph II, followed by another (this one actually commissioned) celebrating the coronation of Leopold II, Joseph’s successor. This sort of piece was standard Kapellmeisterly fare.

Although neither cantata seems to have been performed at the time, they were shown to Haydn, who passed through Bonn en route to England in December of that year, and received his approval. After Haydn’s return from his first London visit, late in 1792, the Elector arranged for Beethoven to study with the great man in Vienna. A line of succession was thus established. The lessons, confined in the main to basic training in counterpoint, did not last long. Haydn was summoned back to England early in 1794.In his absence Beethoven took instruction from some other local maestros—from Johann Georg Albrechtsberger (1736–1809), the Kapellmeister of St. Stephen’s Cathedral; and possibly from Antonio Salieri (1750–1825), the imperial court Kapellmeister—and began making a name for himself as a pianist. He became the darling of the aristocratic salon set, and seemed to be duplicating, or even surpassing, Mozart’s early Viennese success as virtuoso performer and improviser.

By the time Haydn returned in August 1795, Beethoven had become a household name among the noble music lovers of the capital. He had had his first big concert success, performing his Concerto in B major (later published as his Second Concerto, op. 19), and had also published his opus 1. This was a set of three trios for piano, violin, and cello, dedicated to one of his patrons, Prince Karl von Lichnowsky (1761–1814). Haydn expressed regrets that Beethoven had published the third of these trios, a brusque work in the dark key of C minor. In retaliation, Beethoven refused to identify himself on the title page of his op. 2 (three piano sonatas) as Haydn’s pupil, even though the sonatas were dedicated to his former master. (He claimed, when pressed, that although he had taken a few lessons from Haydn, he hadn’t learned anything from him.) These acts of self-assertion, like the startling assertiveness of some of the early compositions, were probably the product of both sincere self-regard and self-promoting calculation. They later became key elements in the Beethoven myth.

major (later published as his Second Concerto, op. 19), and had also published his opus 1. This was a set of three trios for piano, violin, and cello, dedicated to one of his patrons, Prince Karl von Lichnowsky (1761–1814). Haydn expressed regrets that Beethoven had published the third of these trios, a brusque work in the dark key of C minor. In retaliation, Beethoven refused to identify himself on the title page of his op. 2 (three piano sonatas) as Haydn’s pupil, even though the sonatas were dedicated to his former master. (He claimed, when pressed, that although he had taken a few lessons from Haydn, he hadn’t learned anything from him.) These acts of self-assertion, like the startling assertiveness of some of the early compositions, were probably the product of both sincere self-regard and self-promoting calculation. They later became key elements in the Beethoven myth.

Beginning in 1796 Beethoven made concert tours throughout the German-speaking lands. They were immensely successful, both in pecuniary terms and in terms of his spreading fame. The Czech composer Václav Tomá ek (1774–1850) heard him in Prague in 1798; in memoirs he published near the end of his long life he averred that Beethoven was the greatest pianist he had ever heard. Beethoven’s supremacy among composers of his generation was established by the turn of the century, especially after a concert he organized for his own benefit on 2 April 1800. The program contained works by Haydn and Mozart, another Beethoven concerto performed by the author, and, as always, an improvisation.

ek (1774–1850) heard him in Prague in 1798; in memoirs he published near the end of his long life he averred that Beethoven was the greatest pianist he had ever heard. Beethoven’s supremacy among composers of his generation was established by the turn of the century, especially after a concert he organized for his own benefit on 2 April 1800. The program contained works by Haydn and Mozart, another Beethoven concerto performed by the author, and, as always, an improvisation.

But it also contained two new Beethoven compositions without keyboard: the Septet for Winds and Strings, op. 20, which would remain one of his most popular works, and most important by far, the First Symphony, op. 21. This last was the crucial step, because with his symphonic debut Beethoven was now competing not only with other virtuoso composers of his own generation, but directly with Haydn on the master’s own turf. The next year he published a set of six string quartets (op. 18) that challenged Haydn in his other genre of recognized preeminence. This secured Beethoven’s claim, so to speak, as heir apparent to the throne Haydn’s death would shortly vacate.

And now disaster. In a letter to a friend dated 29 June 1801, Beethoven confessed for the first time that, after several years of fearful uncertainty, he was now sure that he was losing his hearing. The immediate result of this devastating discovery was withdrawal from his glittering social life: “I find it impossible to say to people, I am deaf,” he wrote. “If I had any other profession it would be easier, but in my profession it is a terrible handicap.”24 What an understatement! And yet, while eventually he had to cease his concertizing, he did not give up his composing.

FIG. 12-5 Piano by Sebastian Erard, presented to Beethoven by the maker in 1803.

FIG. 12-6 Ear trumpets, made for Beethoven between 1812 and 1814 by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who was best known for his metronome.

Indeed, as he told his brothers in a letter he addressed to them in October of the next year from a suburb of Vienna called Heiligenstadt, composing remained his chief consolation. The realization that he still had music in him, and that he had an obligation to share it with the world, had cured his obsessive thoughts of suicide. This letter, which he apparently never sent, was discovered among Beethoven’s papers after his death. Its poignant mixture of despondency and resolution, and its depiction of a man facing unimaginable obstacles over which he was by then known to have triumphed, have made the Heiligenstadt Testament, as it has come to be known, perhaps the most famous personal utterance of any composer.25 It has done more than any other single document to make Beethoven an object of inexhaustible human interest, the subject of biographical novels, whole galleries of idealized portraiture, and most recently, of biopics.

None of these books, pictures, or films would have been made, it could go without saying, were it not for the extraordinary musical output that followed the Heiligenstadt Testament. And yet perhaps it needs saying after all, for Beethoven’s deafness not only became the chief basis of the Beethoven mystique, and the chief source of his unprecedented authority as a cultural figure; it also served as one of the chief avenues by which Beethoven’s personal fate, as mediated through the critical literature we have been sampling, became the most commanding and regulating single influence on the whole field of musical activity from his time to ours.

The idea of a successful deaf composer is a virtually superhuman idea. It connotes superhuman suffering and superhuman victory, playing directly into the emerging quasi-religious romantic notion of the great artist as humanity’s redeemer. That scenario—of suffering and victory, both experienced at the limits of intensity—became the ineluctable context in which Beethoven’s music was received. And, as we shall shortly see, that very scenario was consciously encoded by the composer in some of his most celebrated works.

Yet there was also another factor at work, profoundly affecting Beethoven’s output and his significance, and enabling him to facilitate by his example the inexorable romantic transformation of musical art and life. His deafness caused him to disappear physically from the musical scene. It removed him, so far as the musical world was concerned, from “real time,” the time frame in which musical daily business was conducted. His creative activities now took place in an unimaginable transcendent space to which no one but he had access. The copious sketches he made for his compositions beginning in the late 1790s (and, somewhat bizarrely, kept in his possession throughout his life) have precisely for this reason exercised an enormous fascination—and not only on musicians or musicologists—as a lofty record of esthetic achievement, but also as an ethically and morally charged human document of Kampf und Sieg (struggle and victory).

The creative and performing functions were in Beethoven gradually but irrevocably severed, leaving only the first. And that sole survivor, the creative function, was now invested with a heroic import that cast the split—again, just as romantic theory would have it—in ethical, quasi-religious terms. Never again would the performing virtuoso composer, on the Mozartean model, be considered the ideal. The composer—the creator—became a truly Olympian being, far removed from the ephemeral transactions of everyday musical life—improvisations, cadenzas, performances in general—and yet a public figure withal, whose pronouncements were regarded as public events of the first magnitude. That was the difference between Beethoven and such earlier nonperforming composers as Haydn. Haydn passed most of his creative life in the closed-off, private world of aristocratic patronage, while Beethoven, even after his social alienation, spoke to the mass public that emerged only after the patronage system had begun to wither.

Beethoven’s last appearance as concerto soloist took place at a concert on 22 December 1808 at which the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies both received their first performances, and Beethoven, in addition to improvising, performed his Fourth Piano Concerto and his so-called Choral Fantasy, a short but grandiose work that begins with a piano solo (extemporized at the first performance) and ends with a choral hymn that foreshadowed the gigantic “Ode to Joy” at the end of the Ninth Symphony. His last public appearance as pianist took place in the spring of 1814 (in the so-called “Archduke” Trio, op. 97), from which time onward, even down to the present, a “classical” composer’s involvement in performance (except as conductor, another sort of silent dictator) would carry something of a stigma, a taint of compromise, as “art” (the province of creators) became ever more radically distinguished from “entertainment” (the province of performers). The distinction between art and entertainment is wholly the product of romantic esthetics. Mozart would not have understood it. Beethoven certainly did. The social and economic conditions that followed the demise of the private patronage system were its enablers. Critics like Hoffmann were its inventors.

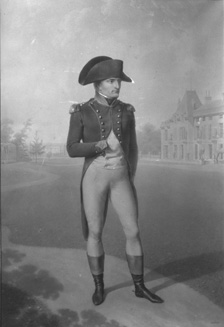

Whether it is fair to infer a causal nexus will forever be a matter for debate, but almost immediately after Beethoven’s confession of his progressive deafness and his social alienation, his music underwent a momentous transformation in style. As early as 1798, the ambassador to Vienna from revolutionary France, General Bernadotte, suggested to Beethoven that he write a “heroic symphony” on the subject of the charismatic young general Napoleon Bonaparte, then riding the crest of adulation for his brilliant campaigns in Italy and Egypt. In the summer of 1803, with Napoleon now (as First Consul) the effective dictator of France and idolized throughout Europe as the great exporter of political Enlightenment, Beethoven was moved to realize this plan.

The work he produced, a sinfonia eroica originally entitled “Bonaparte,” was conceived on a hitherto unprecedented scale in every dimension: size of orchestra, sheer duration, “tonal drama,” rhetorical vehemence, and (hardest to describe) a sense of overriding dynamic purpose uniting the four movements. The monumentally sublime or “heroic” style thus achieved became the mark of Beethoven’s unique greatness and, for his romantic exegetes, a benchmark of musical attainment to which all had now, hopelessly, to try and measure up. The fact that Beethoven, enraged over Napoleon’s crowning himself Emperor of the French in 1804, rescinded the dedication before the first performance of the work, substituting the possibly ironic title “Heroic Symphony Composed to Celebrate the Memory of a Great Man,” only enhanced its sublimity. It took the work beyond the level of representation into the realm of transcendental ideas.

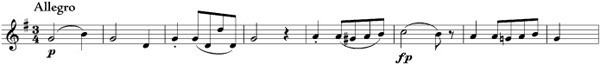

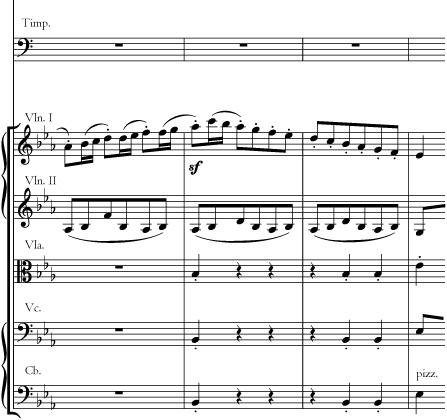

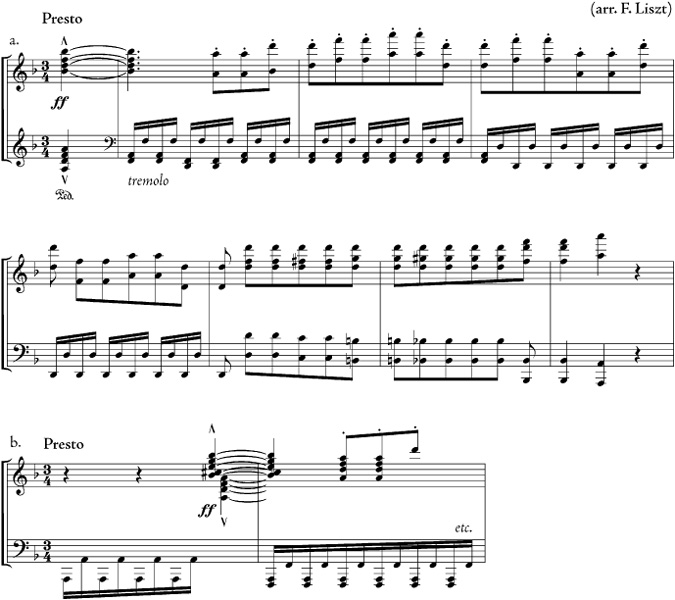

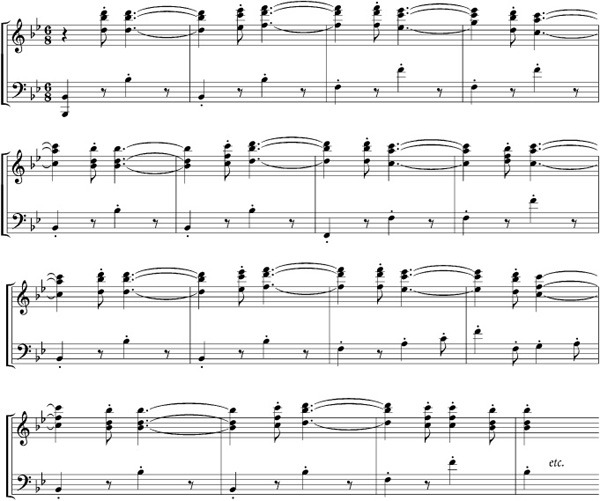

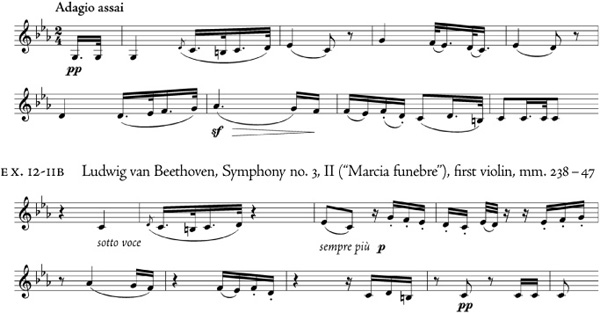

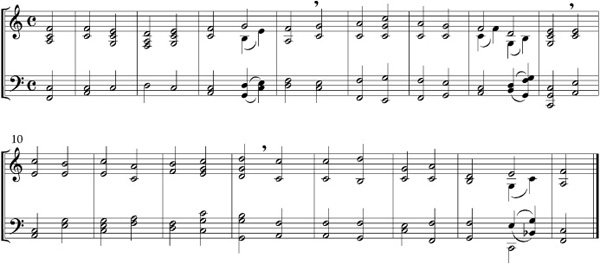

A quick survey of the first movement of the Eroica, as it is now familiarly called, will at once reveal the astonishing earmarks of the new heroic style that seemed so suddenly to spring from Beethoven fully armed, like Athena from the head of Zeus. Analysts and critics never tire of pointing out the insignificance of the theme from which the whole huge edifice derives (a veritable bugle call), or its fortuitous resemblance to the first four bars of a theme by the twelve-year-old Mozart. The latter comes at the beginning of the Intrada (overture) to a trivial little singspiel, Bastien und Bastienne, that the boy wonder tossed off to entertain the guests at a garden party hosted by Dr. Franz Mesmer, the quack healer (Ex. 12-1).

EX. 12-1A W. A. Mozart, Bastien und Bastienne, first theme of intrada, mm. 1–8

EX. 12-1B W. A. Mozart, Bastien und Bastienne, intrada, whole first period

EX. 12-1C Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, mm. 1–44 in thematic outline

There is some point to this comparison. What it shows is not that Beethoven’s theme is inane or insignificant, but more nearly the opposite: that his new style is founded on a new and explosively powerful concept of what produces a significant musical utterance. Mozart’s theme, up to the point quoted in Ex. 12-1a, is entirely conventional in its symmetry. In fairness to the young composer, Ex. 12-1b shows how the continuation of the theme is cleverly “unbalanced.” The second phrase is repeated, and its first two bars are extended in sequence, so that the total length of the theme up to the elided cadence is an interesting fourteen bars in length (4 + 4 + 2 + 2 + 2). But even these departures honor symmetry in the breach. They are by no means unusual or atypical in the music of Haydn and Mozart’s time.

Beethoven’s treatment of the same four-bar fanfare idea is altogether unprecedented in manner (Ex. 12-1c). The C that immediately follows the E

that immediately follows the E -major arpeggio on the downbeat of m. 7 is possibly the most famous single note in the entire symphonic literature, for the way it flatly contradicts all the fanfare’s implications. Rather than initiating a balancing phrase, like the fifth bar of Mozart’s theme, it can only be heard (thanks to the slur) as a violently unbalancing extension—so violently unbalancing, in fact, that the first violins, entering immediately after the C

-major arpeggio on the downbeat of m. 7 is possibly the most famous single note in the entire symphonic literature, for the way it flatly contradicts all the fanfare’s implications. Rather than initiating a balancing phrase, like the fifth bar of Mozart’s theme, it can only be heard (thanks to the slur) as a violently unbalancing extension—so violently unbalancing, in fact, that the first violins, entering immediately after the C , are made palpably to totter for two bars. Relative harmonic stability is restored in m. 9 by the resolution of the uncanny chromatic note back to a normal scale degree (the leading tone), marked with the first of countless sforzandi to give it the force necessary to prop the tottering violins. But the two-bar “time out” in mm. 7–8 has scotched all possibility of phrase symmetry—all possibility, that is, of “themehood,” at least for the moment.

, are made palpably to totter for two bars. Relative harmonic stability is restored in m. 9 by the resolution of the uncanny chromatic note back to a normal scale degree (the leading tone), marked with the first of countless sforzandi to give it the force necessary to prop the tottering violins. But the two-bar “time out” in mm. 7–8 has scotched all possibility of phrase symmetry—all possibility, that is, of “themehood,” at least for the moment.

All one can do is try again. A cadence, reinforced by the wind instruments, clears the slate in mm. 14–15. (The first stab at the first theme, not counting the two-bar chordal preparation at the outset, has lasted not Mozart’s interestingly subdivided fourteen bars, but an entirely undivided and indivisible thirteen—probably the most hopelessly and designedly off-balance opening in the symphonic literature.) Balance having been provisionally restored, the winds restate the opening four-bar fanfare. In dialogue with the strings the ascending arpeggio at the end is detached and developed sequentially until the dominant is reached; whereupon harmonic motion is stalled (m. 22), preventing closure.

The long series of syncopated sforzandi that now follows (mm. 24–33) seems to push hard against a implied harmonic barrier, until an exhilarating breakthrough to the tonic (m. 36) initiates what is obviously a climactic statement of the original fanfare motif, coinciding with the first orchestral tutti, replete with martial trumpets and drums. Even this statement, however, dissipates in a sequence without achieving closure. Instead, after eight bars (m. 42), a decisive pull away from the tonic (by means of an augmented sixth resolving to F, the dominant’s dominant) launches the modulation to the secondary key.

What we have been given, in short, is a thematic exposition that furnishes no stable point of departure, but that instead involves us from the beginning in a sense of turbulent dynamic growth: not state, so to speak, but process; not being, to put it philosophically (and romantically), but Becoming. The theme is not so much presented as it is achieved—achieved through struggle. The clarity of metaphor here, instantly apprehended by contemporary listeners, lent this music from the beginning an unprecedented ethical potency.

Not that the metaphor was in any way categorical or determinate in meaning. As the music theorist Scott Burnham has put it, the struggle-and-achievement paradigm could be attached to Napoleon (as “Beethoven’s hero”) or to the composer himself (as “Beethoven Hero,” Burnham’s name for the “author-persona” of the Eroica).26 It could as easily be felt as a metaphor for the listener’s own inner life, thus potentially symbolizing bourgeois self-realization, or liberation, or religious transcendence. In any event, as Burnham points out, Beethoven’s achievement provided the supreme symbolic expression of the chief philosophical and political ideals of its time and place. He calls it, in the tradition of German cultural history, the “Goethezeit,” the time of the great polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832)—poet, playwright, philosopher, and natural scientist in one. He makes it clear, though, that the time might better have been called the “Beethovenzeit,” for precisely with Beethoven, and by force of his example, music achieved its century-long preeminence in the eyes of all romantic artists.

But of course the Eroica movement is only just getting underway. Closure is deliberately, indeed demonstratively, withheld even from the climactic statement of the theme. Dynamic process continues through the modulatory section that now ensues, carrying the listener along through a great wealth of new melodic ideas before the second theme is even reached—and when it finally arrives, at m. 83, it provides no more than a brief touching-down on the way to the main cadence of the exposition.

FIG. 12-7 Goethe in the Roman Campagna (1787) by Johann Heinrich Tischbein.

The formal development section having been reached, the same structural/ethical process that shaped the opening theme will be seen to operate at the global level as well, giving shape to the entire 691-measure movement, which thus emerges not as a gigantic sprawl but as a single directed span—or, to recall Goethe the naturalist, a single organic growth. The same rhetorical gesture that governed the very first statement of the fanfare—that of a disruptive detour enabling a triumphant return—will shape the movement as a whole, lending the opening statement a quality of prophesy and the whole a quality of fated consequence.

Of course the “there-and-back” or pendular harmonic plan had been a fundamental shaper of musical form for a hundred years or more when Beethoven composed the Eroica; of course his music was rooted in that tradition and depended on it both for its coherence and for its intelligibility. Moreover, his accomplishment could be looked upon as a continuation of Mozart’s and (particularly) Haydn’s earlier project of dramatizing the binary plan: that, we may recall, is what “symphonic” style was all about from the beginning. And yet the difference in degree of drama—or more to the point, of disruption and concomitant expansion—in Beethoven’s treatment of the plan seemed to his contemporaries, and can easily still seem, to be tantamount to a difference in kind.

Consider the move to the “far-out point” (FOP) in the development section, starting (for those with access to the score) at m. 220. That measure recommends itself as an access point because tonal progress up to it has been slow. In fact, the harmony is the same E triad that elsewhere in the piece functions as the tonic. Here, however, owing to its preparation (an augmented sixth on F

triad that elsewhere in the piece functions as the tonic. Here, however, owing to its preparation (an augmented sixth on F , precisely analogous to the one on G

, precisely analogous to the one on G with which Ex. 12-1c ended) it is clearly identified as the local dominant of A

with which Ex. 12-1c ended) it is clearly identified as the local dominant of A , the global subdominant. The harmony rocks gently back and forth for a while between the local dominant and the local tonic before a move to F minor (m. 236) incites a fugato, a common tactic for speeding up harmonic rhythm toward an implied goal.

, the global subdominant. The harmony rocks gently back and forth for a while between the local dominant and the local tonic before a move to F minor (m. 236) incites a fugato, a common tactic for speeding up harmonic rhythm toward an implied goal.

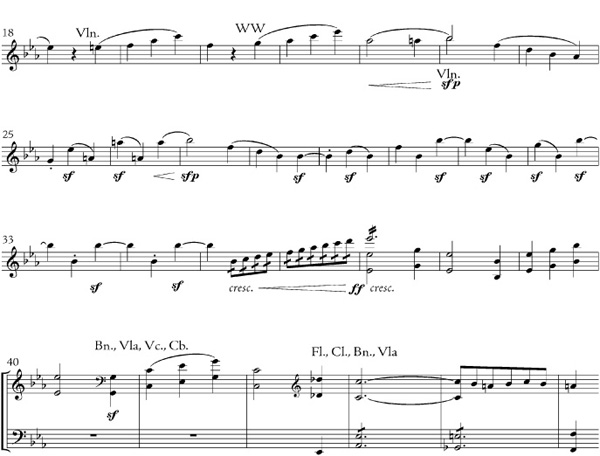

And then it happens. Just as in the exposition at m. 25 ff, the harmony stalls and strains against an invisible barrier suggested by the same syncopated sforzandi as before (Ex. 12-2). Only this time (m. 248) it stalls not on a primary harmonic function of whose eventual resolution there is no doubt, but on a diminished-seventh chord built on G —enharmonically equivalent to A

—enharmonically equivalent to A , the local tonic, but now implying resolution to A, a note altogether outside the tonic scale. The stall therefore arrests the harmonic motion at a far more threatening point; for even when resolution takes place (m. 254), there is no sense of achievement—just another stall. Six measures later the A minor harmony is resolved “Phrygianly” to an even more remote sonority, a dominant-seventh on B-natural, presaging even less satisfying prospects for resolution than before (see Ex. 12-2).

, the local tonic, but now implying resolution to A, a note altogether outside the tonic scale. The stall therefore arrests the harmonic motion at a far more threatening point; for even when resolution takes place (m. 254), there is no sense of achievement—just another stall. Six measures later the A minor harmony is resolved “Phrygianly” to an even more remote sonority, a dominant-seventh on B-natural, presaging even less satisfying prospects for resolution than before (see Ex. 12-2).

And it is indeed to that unlikely goal—E-natural, seemingly a further-out FOP than ever approached before—that resolution is eventually made, but not before one last detour through another set of wrenching harmonic stalls that finally reapproaches the dominant-seventh-of-E through the Neapolitan of that unclassifiable key, expressed in a fiercely dissonant form that retains as a suspension the high flute E from the preceding C-major chord (the flat submediant of the looming key, suggesting that it will materialize in the minor). The suspended E rubs painfully against F, the chord root, in the other flute part. For fully four excruciating measures (mm. 276–279) this ear-splitting harmony is hammered out—and then simply dropped (Ex. 12-3).

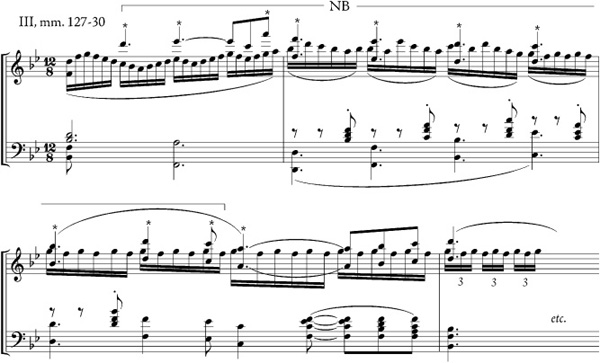

EX. 12-2 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, mm. 248–65

The grating semitone between the flutes is never resolved; resolution takes place only by implication, in another register, played on other instruments (the E resolving to the first violins’ D in m. 280, the F, most unconventionally, to the viola F

in m. 280, the F, most unconventionally, to the viola F ). The resolution chord, delayed by a disruptive rest on the downbeat of measure 280, still throbs tensely owing to the second violins’ C-natural, suspended from the preceding chord, which adds a minor ninth to the dominant seventh on B. Tension is reduced by degrees: the C moves to B in measure 282, the remaining dissonance (A, the chord seventh) to G in measure 284. The smoke has metaphorically cleared, and we are left in E minor, the “unclassified” tonality adumbrated twenty-four measures before, with no immediate prospect of return to harmonic terra firma.

). The resolution chord, delayed by a disruptive rest on the downbeat of measure 280, still throbs tensely owing to the second violins’ C-natural, suspended from the preceding chord, which adds a minor ninth to the dominant seventh on B. Tension is reduced by degrees: the C moves to B in measure 282, the remaining dissonance (A, the chord seventh) to G in measure 284. The smoke has metaphorically cleared, and we are left in E minor, the “unclassified” tonality adumbrated twenty-four measures before, with no immediate prospect of return to harmonic terra firma.

EX. 12-3 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, mm. 276–288.

So far from home no symphonic development had ever seemed to stray before. Having dramatized the disruption, Beethoven now dramatizes the sense of distance by unexpectedly introducing a new theme in the unearthly new key (mm. 284ff). It has been argued that this theme is a counterpoint to an embellished variant of the main theme of the movement (see Ex. 12-4), hence not really a new theme at all. But even if one accepts the demonstration shown in Ex. 12-4, the novelty of the music at m. 284 is striking—as indeed it must be, because it performs an unprecedented function within the movement’s dramatic unfolding. By far the most placid, most symmetrically presented melody in the movement, it expresses not “process” but “state” for a change—the state of being tonally adrift.

EX. 12-4 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, the relationship between the E minor theme at mm. 284ff and the main theme of the first movement

And yet, there being only twelve possible tone centers, and only six degrees of remoteness (since once past the midpoint, whether reckoning by the circle of fifths or by the chromatic scale, one is circling not out but back), one is never quite as far away from home as one is made at such moments to feel. Beethoven engineers a “retransitional” coup similar to the one we have already encountered in the slow movement from Mozart’s G-major piano concerto, K. 453 (Ex. 11-5), whereby the seeming outermost reaches of tonal space are traversed in a relative twinkling. But where Mozart did it with maximum smoothness, to amaze (and perhaps amuse), Beethoven does it with maximum drama, to inspire and thrill.

Understood enharmonically, as F , E-natural is equivalent to

, E-natural is equivalent to  II, the flatted or “Neapolitan” second degree of the scale, just a stone’s throw from the tonic on the circle of fifths. Beethoven does not take quite such a direct route home; but he might as well have done, since by mm. 315–316 he has achieved the essential linkage, hooking up the flat supertonic broached in m. 284 with V and I of the original key, its implied successors along the circle of fifths. All harmonies on either side of this essential link amount to rhetorical feinting, staving off the inevitable moment of “double return,” when the tonic key and the first theme will at last make explosive contact.

II, the flatted or “Neapolitan” second degree of the scale, just a stone’s throw from the tonic on the circle of fifths. Beethoven does not take quite such a direct route home; but he might as well have done, since by mm. 315–316 he has achieved the essential linkage, hooking up the flat supertonic broached in m. 284 with V and I of the original key, its implied successors along the circle of fifths. All harmonies on either side of this essential link amount to rhetorical feinting, staving off the inevitable moment of “double return,” when the tonic key and the first theme will at last make explosive contact.

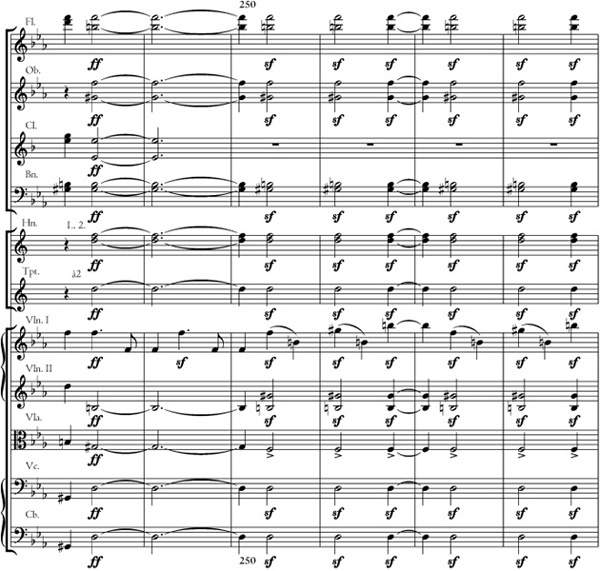

The purpose of strategic delay, or “deferred gratification,” is, as always, the enhancement of the emotional payoff when the long-awaited event is finally allowed to occur. It does not happen until m. 398, by which time suspense has been deliberately jacked up to an unbearable degree (see Ex. 12-5, which begins twenty measures earlier)—so literally unbearable, in fact, that at m. 394 the first horn goes figuratively berserk, personifying and “acting out” the listener’s agony of expectation by breaking in on the violins—still dissonantly and exasperatingly protracting the dominant function in a seemingly endless tremolo—with a premature entry on the first theme in the tonic.

EX. 12-5 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, mm. 378–405

So unprecedented was this bold psychological stroke that it was at first mistaken, even by the composer’s close associates, for a sort of prank. His pupil and assistant Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838) described it in his memoirs as a “mischievous whim” (böse Laune), and recalled that

At the first rehearsal of the symphony, which was horrible, but at which the horn player made his entry correctly, I stood beside Beethoven, and, thinking that a blunder had been made, I said: “Can’t the damned hornist count?—it’s so obviously wrong!” I think I came pretty close to receiving a box on the ear. Beethoven did not forgive the slip for a long time.27

Far from a blunder or a miscount, the horn entrance dramatizes once again in retrospect the unprecedented scope of the tonal journey the movement has traversed and the pent-up emotional stimulation such a journey generates as it nears its desired fulfillment.

Nor is this the only way in which Beethoven will exploit the sense of disruption caused within the movement by the digression in mid-development to a new theme in a remote key. As in the exposition of the first theme, what is done first at a local level is later recast on the global plane. Full redemption of the movement’s disruptive forces, and full discharge of its tonal tensions will come only after the apparent end of the recapitulation, in a mammoth coda that begins at m. 557 with a shockingly sudden irruption of D , the enharmonic equivalent of the pitch that sounded the first disruptive note of all, way back in m. 7. This probably comes as a bigger surprise than anything else in the movement, but like most of Beethoven’s “disruptions” it is a strategic maneuver, enabling the control of longer and longer time spans by a single functional impulse.

, the enharmonic equivalent of the pitch that sounded the first disruptive note of all, way back in m. 7. This probably comes as a bigger surprise than anything else in the movement, but like most of Beethoven’s “disruptions” it is a strategic maneuver, enabling the control of longer and longer time spans by a single functional impulse.

The coda thus convulsively introduced takes up and resolves two pieces of unfinished business. First it effectively recapitulates the E-minor theme within the normal purview of the tonic by having it appear in F minor, the ordinary diatonic (“unflatted”) supertonic. But that is only by the way. The coda’s main business is at last to provide the fully articulated, cadentially closed version of the opening theme that has been promised from the very start of the movement, but that has never materialized. It arrives at m. 631 in the form of a quietly confident horn solo that makes up, as it were, for the horn’s harried “false entrance” 237 bars earlier. Its swingingly symmetrical eight-bar phrase finally juxtaposes tonic and dominant versions of the opening arpeggio, thus for the first time closing the harmonic circle at close range(Ex. 12-6).

Four times the phrase is repeated, together with its rushing countersubject, in a massive crescendo that ultimately engulfs the whole orchestra, the trumpets and drums entering on the third go-round with a military tattoo (pickup to m. 647) and, on the fourth, finally breaking the melodic surface in a final thematic peroration. Yet even this crest is immediately trumped by one final disruption, the diminished-seventh chord in mm. 663–664, with D /C

/C (what else?) as the climactic note in the bass. From here there is nothing left to do but retake the goal in one last eight-bar phrase, after which only a clinching I-V-I remains—with the V extended through one more characteristic “stall” (mm. 681 ff) to bring home the final pair of tonic chords (mirroring the pair at the other end of the movement and retrospectively justifying it) as one last victory through struggle.

(what else?) as the climactic note in the bass. From here there is nothing left to do but retake the goal in one last eight-bar phrase, after which only a clinching I-V-I remains—with the V extended through one more characteristic “stall” (mm. 681 ff) to bring home the final pair of tonic chords (mirroring the pair at the other end of the movement and retrospectively justifying it) as one last victory through struggle.

One listens to a movement like this with a degree of mental and emotional engagement no previous music had demanded, and one is left after listening with a sense of satisfaction only strenuous exertions, successfully consummated, can vouchsafe. Beethoven’s singular ability to summon that engagement and grant that satisfaction is what invested his “heroic” music with its irresistible sense of high ethical purpose and power. It is not the devices themselves—anyone’s devices, after all—that so enthrall the listener, but the singleness of design that they conspire to create, the scale on which they enable the composer to work, and the metaphors to which these stimuli give rise in the mind of the listener.

EX. 12-6 Ludwig van Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, Op. 55 (Eroica), I, mm. 631–639

The exalted climactic statement of the opening theme in particular makes use of a cluster of devices—accumulating sonority over an ostinato swinging regularly between the harmonic poles—that as the “Rossini crescendo” would soon cap the overtures to the zaniest comic operas ever written, operas that ever after would scandalize Beethoven’s high-minded German devotees with their Italianate frivolity. Anyone’s devices indeed: their effect is entirely a matter of context.

In the Beethovenian context, far from a light amusement, the big regular crescendo brings long-awaited closure to a tonal drama of unprecedented scope. That long-deferred resolution is what creates in the listener what Hoffmann called the “unutterable portentous longing” that is the hallmark of romantic art. That “purely musical” tension and release, powerfully enacted in a wordless context, is what produces in the listener such a total immersion in what Hoffmann called “the spirit world of the infinite.”

The great majority of Beethoven’s works, to the end of the first decade of the new century (that is, up to the time of Hoffmann’s decisively influential critiques), were marked by the new heroic style, whether opera (Leonore, later revised as Fidelio, on a subject supposedly borrowed from an actual incident from French revolutionary history), or symphony, whether chamber music (the three quartets published as op. 59 with a dedication to Count Razumovsky, the Russian ambassador) or piano sonata (the “Waldstein,” op. 53, or especially the “Appassionata,” op. 57).

Their prodigious dynamism not only transformed all the genres to which Beethoven applied himself, but also met with wild approval from an ever-widening bourgeois public who read in that dynamism a portent and a portrayal of their own social and spiritual triumph. For such listeners (as Hoffmann, their unwitting spokesman, put it explicitly), Beethoven finally realized the universal mission of music, just as they felt that in their own lives they were realizing the universal aspiration of mankind to political and economic autonomy—an aspiration defined as the superhuman realization of the “World Spirit” by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), the great romantic philosopher of history and Beethoven’s exact contemporary. To read Beethoven’s music as a metaphor of the universal world spirit was as seductive a notion as it was perilous.

What made it perilous was the tendency it encouraged to cast one’s own cherished values as “universal” values, good (and therefore binding) for all. To see all music that did not conform to the heroic Beethovenian model as deficient to the extent of the difference was to discriminate invidiously against other possible musical aims, uses, and styles. To the extent, for example, that the Beethovenian ideal was identified with virility, or with at times violently expressed “manly” ideals of strength and greatness, it invited or reinforced prejudice against women as composers, even as social agents. To the extent that it sanctioned neglect of the audience’s pleasure, it could serve to underwrite gratuitous obscurity or difficulty. To the extent that it exalted the representation of violence, whether of Kampf (struggle) or Sieg (victory), it could serve as justification for aggressive or even militaristic action. To the extent that it was identified with German national aspirations or (as we will very shortly see) with a concept of German “national character,” it encouraged chauvinism. To the extent that it was identified with middle-class norms of behavior, it paradoxically thwarted the expression of other, equally “romantic” forms of creative individualism.

That these unwarranted and undesirable side effects have at various times emerged from the Beethoven myth is a matter of historical fact. Whether they are implicit (or, to speak medically, “latent”) in it is a matter for continued, and possibly unsettleable, debate.

That such attributes were not inherent in Beethoven but constructed by listeners and interpreters is certainly suggested by the facts of his actual career. The remarkable thing is the way in which he was accepted both by the new mass public and by the old aristocratic one, which continued as before to support him financially, albeit collectively rather than by direct employment. (It should be added that Beethoven’s own social attitudes, as conveyed in documents and anecdotes, were ambiguous at best, and inconstant.) Thanks to that support, Beethoven was able to evade the prospect of steady work as Kapellmeister at the court of Westphalia in Kassel, where Napoleon had installed his youngest brother Jerome as king. A consortium of Viennese noblemen undertook in 1809 to guarantee Beethoven a lifetime annuity that more than matched the salary he was offered at Kassel, and that allowed him to devote his full time to composing as he wished, provided only that he remain in Vienna.

This consortium included the Archduke Rudolph, the emperor’s younger brother and Beethoven’s only composition (as opposed to piano) pupil, to whom the composer dedicated no fewer than ten works, including the “Archduke” Trio (op. 97, composed 1810–11), the “Emperor” Concerto (Piano Concerto no. 5, op. 73, composed 1809), and the Mass in D (Missa solemnis), op. 123 (1819–23), composed in celebration of Rudolph’s investment as a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. The consortium also included Prince Joseph Franz Maximilian von Lobkowitz, scion of an ancient Bohemian family long famous for its arts patronage, who had underwritten the first performance of the Eroica Symphony at his own private residence in 1804, and to whom Beethoven dedicated not only the Eroica but six other works as well, including the op. 18 quartets and both the Fifth and the Sixth Symphonies.

From this evidence of mutual devotion between Beethoven and the Viennese aristocracy, it is clear that the idea of the composer as a musical revolutionist or Jacobin, widespread in the romanticizing literature that cast him as “The Man Who Freed Music” (the title of Robert Schauffler’s 1929 biography), is as one-sided and misleading as the opposing image—that of the isolated, world-renouncing hermit on a lonely quest of saintly personal fulfillment, just as widespread in an opposing romanticizing literature that culminated in another influential book (J. W. N. Sullivan’s Beethoven: His Spiritual Development, published in 1927, the centennial of the composer’s death). These images, and many others, were partial readings of the life of Beethoven in support of one or another variant of the myth of Beethoven, for almost two centuries one of the most potent stimuli to musical thought and action in the West, but a fantastically various one.

The “heroic” phase of Beethoven’s career lasted until around 1812, with the completion of his Eighth Symphony. He then lapsed, probably as a result of deepening deafness and personal frustrations, into a period of depression and evident decline. Goethe, who finally met his great contemporary at a Bohemian spa in the summer of 1811, remarked that Beethoven “was not altogether wrong in holding the world to be detestable, but surely does not make it any the more enjoyable either for himself or for others by his attitude,” adding that his deafness “perhaps mars the musical part of his nature less than the social.”28 Between 1810 and 1812 the composer suffered repeated setbacks in his personal life. Increasingly desperate overtures to unwilling or unavailable prospective brides culminated in an enigmatic love letter to an unnamed “Immortal Beloved,” written in the summer of 1812 and discovered unsent, like the Heiligenstadt Testament, among his posthumous effects. Beethoven being almost as much the object of “human interest” attention as he has been of musical, scholars and biographers and movie producers have devoted enormous energy to the problem of identifying Beethoven’s mysterious love interest.

If Maynard Solomon, one of Beethoven’s biographers, was right in advancing the name of Antonie Brentano, now regarded as the most plausible candidate, then Beethoven’s fate as hopeless suitor has been intriguingly illuminated.29 Frau Brentano, the sister-in-law of Bettina Brentano, a young piano pupil and friend of Beethoven’s, was for two reasons out of reach: she was of aristocratic birth, and she was already married. Beethoven’s lifetime status as a forlorn bachelor, another reason for his posthumous casting as a spiritual hermit, may well have been as much the result of psychological obstacles as actual social impediments. Brought to a state of turbulence by his multiple rejections and thwartings around 1812, they may have contributed to his creative silence in the years that followed.