Throughout the eighteenth century, opera and its endless “reforms” continued to encode the social history of the age. That is why opera criticism so often makes good and exciting reading, even when the composers and the operas of which it treats have been long forgotten. Both by design and by its nature, it can mean far more than it says.

And again both by design and by its nature, the burgeoning comic opera continued to bear the heaviest freight of what is now called “subtext” (that is, the stuff you read between the lines) even as it continued to be “the best school for today’s composers,” in the words of the German musician Johann Adam Hiller (1728–1804), who reacted to it both as composer and as critic.1 “Symphonies, concertos, trios, sonatas—all, nowadays, borrow something of its style,” Hiller wrote in 1768.

The composer whom Hiller had first in mind was his exact contemporary Niccolò Piccinni (1728–1800), who certainly qualifies today as “long forgotten.” In his day, however, Piccinni was not only a prominent figure but a controversial one as well. He became the focal point of a “cause” and, in his rivalry with the somewhat older (and today much better-remembered) Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–87), the object of a querelle, a Parisian press war. The issues his career raised for contemporary audiences, critics, and composers continued to reverberate long after the decades of his greatest fame. They were issues of social as well as musical import.

The best way of approaching Piccinni’s “cause” and its social repercussions might be to note that his most famous opera, La buona figliuola (“The good little girl,” or “Virtuous maiden”), was one of the earliest to be based on a modern novel, then a new literary genre with distinct social implications of its own. The opera’s success was virtually unprecedented: between its Roman première (with an all-male cast) in 1760 and the end of the eighteenth century, La buona figliuola played every opera house in Europe, enjoying more than seventy productions in four languages.

Its plot came by way of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), a novel in the form of letters that tells of a chaste maidservant who so resourcefully resists the crass advances of her employer’s son that the young man finally falls seriously in love with her and marries her with his family’s blessing. Pamela achieved phenomenal popularity with a new class of readers, the same “bourgeois” readership that made the novel the paramount literary genre for centuries to come, and who were especially susceptible to Richardson’s idealistic moral: to wit, that natural virtues and emotions—pertinacity, honesty, love—can be practiced both high and low, and can level artificial barriers of rank.

This is only a variation, of course, on an ancient pastoral prototype, in which virtuous maids fend off or are rescued from lascivious aristocrats. But it was indeed a novel variation, and a telling one, this sentimental version in which the bar of class is actually overcome and maid and aristocrat find happiness together. For aristocrats, then, the moral “love conquers all” could be a socially ominous one. The eighteenth-century English novel was, among other things, a celebration—and, potentially, a breeding ground—of social mobility. The Pamela motif has been a stock-in-trade of bourgeois fiction ever since, though by now more a cliché of “romance novels” and soap operas (like Our Gal Sunday, a radio staple from the 1930s to the 1950s: “the program that asks the question, Can a young girl from a small mining town in West Virginia find happiness as the wife of a wealthy and titled Englishman?”) than of serious fiction.

Richardson’s novel was soon translated into Italian, and attracted the attention of Carlo Goldoni, whom we met briefly in the previous chapter as the chief librettist of the early opera buffa. Actually, librettos were only a sideline for Goldoni, the leading Italian dramatist of the century. His main mission in life, as he saw it, was replacing the old improvised commedia dell’arte with literary comedies that had fully worked-out scripts and modern realistic situations, worthy of comparison with Molière and Congreve, the mainstays of the French and English stage. Goldoni saw in Pamela the makings of a hit, but as often happened, some funny things happened to the story on its way to the stage.

The trouble was that an Italian audience would not have found the plot sufficiently believable. Nor could such a thing be shown in the theater, which, being a site of public assembly, was in Italy (as elsewhere) far more strictly policed by censors than the literary press. The sticking point was the happy ending—or rather, what made it happy. The elevation of a poor commoner through marriage was not possible in Italy. According to Italian law, such a marriage would bring about not the ennobling of the commoner but the disgrace and impoverishment of the noble.

Hence Goldoni was forced to find another motivation or excuse for the happy marriage. He found it in the device of mistaken identity: Pamela’s father turns out to be not a poor schoolteacher but an exiled count, and so she can marry her noble lover with impunity. As Goldoni put it in the preface to his adaptation,

The reward of virtue is the aim of the English author; such a purpose would please me greatly, but I would not want the propriety of our Families to be altogether sacrificed to the merit of virtue. Pamela, though base-born and common, deserves to be wed by a Nobleman; but a Nobleman concedes too much to the virtue of Pamela if he marries her notwithstanding her humble birth. It is true that in London they do not scruple to make such marriages, and no law there forbids them; nevertheless it is true that nobody would want his son, brother, or relative to marry a low-born woman rather than one of his own rank, no matter how much more virtuous and noble the former.2

The emphasis was thus shifted away from the potential disruption of traditional social norms, but the satisfaction of natural love in a happy marriage was nevertheless retained, and the story could still capture the imaginations of idealistic lovers. Whereas we may think the device of mistaken identity a threadbare stratagem, in the context of eighteenth-century continental society and its rules, the device made the story more realistic and convincing, not less.

When Goldoni finally adapted his Pamela adaptation as an opera libretto, he had to make even more changes in order to satisfy the musical requirements of the opera stage. Now Pamela (rechristened La Cecchina) and her pursuer (Il Marchese della Conchiglia) are in love from the beginning, at first hopelessly. They are the main soprano/tenor pair, and sing duets. The Marchese’s sister, Lucinda, also based on a Richardson character, is there to oppose the social mismatch. She is given a lover (Il Cavaliere Armidoro) who threatens her with rejection if her brother takes a common wife. There is a basso buffo, Mengotto, a gardener in love with Cecchina, and a sharp-tongued servant girl, Sandrina, in love with Mengotto. (She also gets a sidekick, Paoluccia, with whom she sings gossipy patter duets.)

The last of the newly invented characters is the swashbucking German mercenary soldier Tagliaferro, another basso buffo who gets wheezy laughs by mangling Italian. It is he who clears up the matter of Cecchina’s parentage in the last scene. All the tangled pairs are sorted out, and multiple happy weddings are forecast: Cecchina with the Marchese; Lucinda with the Cavaliere; Mengotto with Sandrina. The libretto ends with an invocation to Cupid from all hands: “Come unite each loving heart,/And may true lovers never part.”

That would henceforth be the stock ending of the buffa, so that operas eventually divided into those in which people die (tragic) and those in which they marry (comic)—but both, increasingly, for love, not duty. That substitution was the great sentimental innovation and the great hallmark of “middle-class” (as opposed to aristocratic or “Family”) values. It flew directly in the face of the opera seria, at first its chief competitor, which celebrated noble renunciation in dramas where people (or title characters, at any rate) neither died nor married. It marked the point at which the comic opera could begin to surmount the farce situations of the intermezzos and carry a serious or uplifting message of its own. That serious message was nothing less than a competing set of class aspirations—the aspirations of a self-made class whose power had begun to threaten that of hereditary privilege.

In Italian the new genre was eventually christened semiseria; in French, more revealingly, it was called comédie larmoyante (“tearful comedy”). In both, the happy end was reached by way of tears and therefore carried ethical weight. But instead of the weight of traditional social obligation, it was the weight of an implied injunction to be “authentic”—artlessly true to one’s natural feelings. (And yet, as the opera historian William C. Holmes observes, the Marchese nevertheless “seems quite relieved when, in the dénouement, Cecchina is revealed as a German baroness.”3) We know the device of mistaken identity the only way we can know it now—through a screen of cynical nineteenth-century satires (as in the operettas of Gilbert and Sullivan) that returned it to the realm of farce. Originally it was just as thrilling a concept as the intervention of a deus ex machina had been in an earlier age: it was the device through which the genre’s approved values—true love and artless virtue—could find their just reward.

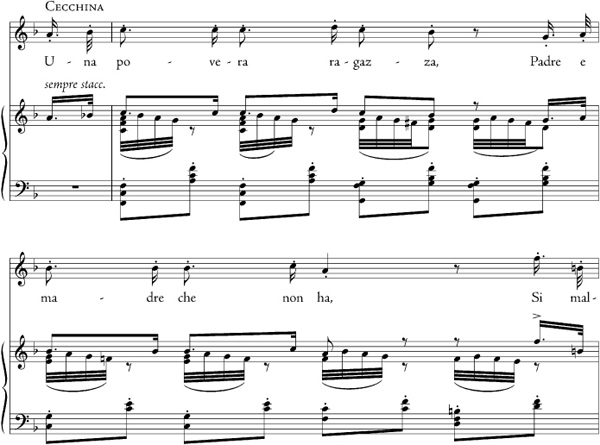

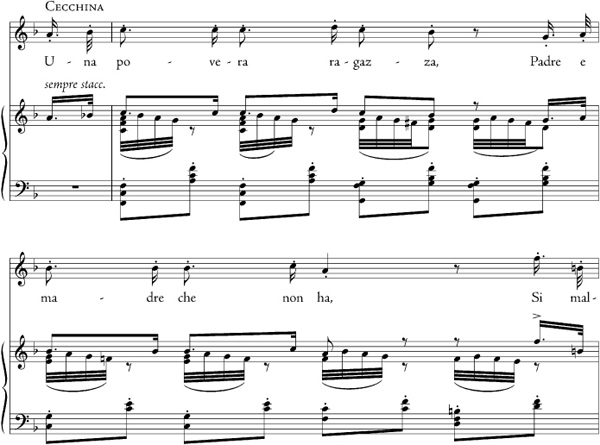

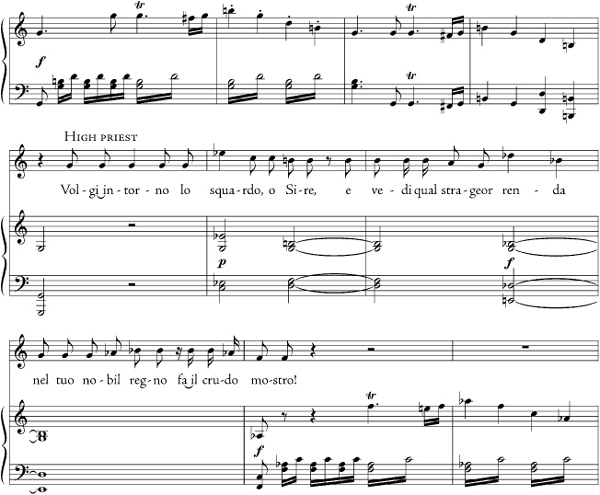

For even though unwittingly a baroness by accident of birth, Cecchina is by nature and by her true character just “una povera ragazza,” a poor girl with a pure heart. The Italian phrase is the title of her main aria, the opera’s most famous number (Ex. 9-1a), in which she exposes that heart for all to see—or rather hear (its very beating is famously represented by the second violins)—since the music, as in any opera, is the ultimate arbiter of truth. The social idealism that was the essence of the comédie larmoyante is made explicit by Piccinni’s music and its canny contrast of styles. For Cecchina’s aria, with its folklike innocence, is immediately contrasted with one that depicts the artful scheming of Lucinda (Ex. 9-1b), who as a “noble” character is given all the appurtenances of an opera seria role—in particular the virtuoso coloratura style of singing, replete with melismas on emblematic words (in this case disperato, “hopeless”). Of course in this ironic context it is just the “noble” aspects of Lucinda’s music that cast her as ignoble, for she schemes to thwart the rightful consummation of true love. It is she, of course, who is thwarted in the end.

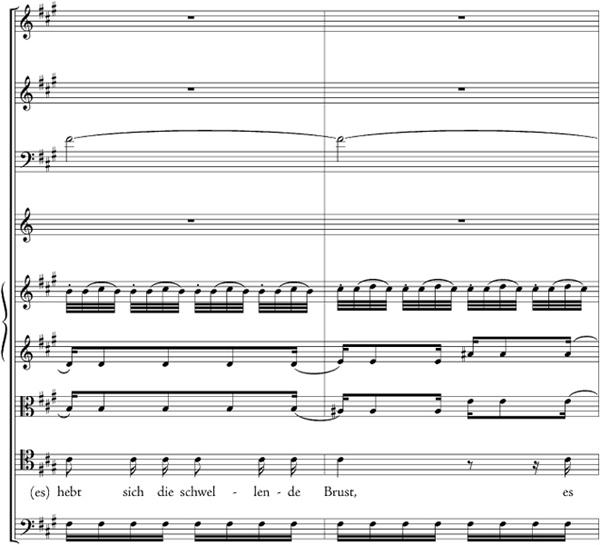

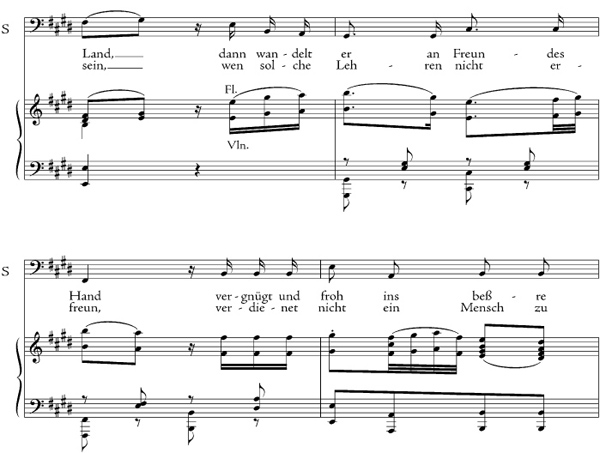

EX. 9-1A Niccolò Piccinni, La buona figliuola, “Una povera ragazza”(Act I, scene 12), mm. 5–9

EX. 9-1B Niccolò Piccinni, La buona figliuola, “Furie di donna irata” (Act I, scene 14), mm. 21–31

So even if it typically ended with a perfunctory nod at aristocratic propriety, the comédie larmoyante was a genre in which the bourgeoisie, the optimistic “self-made” class, glorified itself and celebrated its dream of limitless opportunity. It was no accident, then, that the prototype was English. Indeed, the spread of Pamela, and of Pamela-inspired spinoffs, into continental artistic consciousness is an index by which to measure the spread of bourgeois ideals. Aristocratic audiences, needless to say, found the genre insufferable, and it quickly became just as popular a target for lampooning as the opera seria had been. Indeed, the adjective larmoyante, which in normal usage is just as disparaging in its implications as the English “lachrymose,” was originally applied to the new genre by contemptuous aristocrats.

One aspect of comic opera, noticeable already in Pergolesi’s Serva padrona, received a notable boost from Piccinni in La buona figliuola. The shape of a comic libretto depended on a plot that is first hopelessly tangled, then sorted out. The musical shape of the opera followed and epitomized this plan in a fashion that set the comic genre completely apart from the contemporary seria. Both the tangle (imbroglio) and the sorting were symbolized in complex ensemble finales in which all the characters participated. In an intermezzo like La serva padrona these were mere duets. In full-length opera buffa, they could be scenes of great length and intricacy, in which the changing dramatic situation was registered by numbers following on one another without any intervening recitative, all to be played at a whirlwind pace that challenged any composer’s imaginative and technical resources. The first two acts of La buona figliuola end with quintets, the third and last with nothing less than an octet, representing the full cast of characters.

The second-act finale represents the height of imbroglio. Tagliaferro has just persuaded the ecstatic Marchese that Cecchina must be the lost baroness Mariandel on account of a distinctive blue birthmark on her breast. The Marchese rushes off to prepare their wedding forthwith, leaving Tagliaferro alone with the sleeping Cecchina. She calls tenderly in her sleep on her lost father. Tagliaferro, moved, responds in kind. Unfortunately this curious exchange is witnessed by Sandrina and Paoluccia. It is here that the finale begins.

At first it is dominated by the buffi, the characters most nearly recognizable from the earlier farce intermezzos like La serva padrona—namely Sandrina and Paoluccia, the sharp-tongued gossips, and Tagliaferro, the bumbling bass. They accuse him of trying to seduce Cecchina, and when the master returns (his entry underscored with a modulation to the subdominant), they denounce the hapless Tagliaferro. The Marchese, however, does not believe them, rejecting their malicious tale in a melting siciliano that expresses the purity of his love and faith. A quick change of tempo turns the siciliano into a madcap jig as the two girls argue back with the two men, finally reaching a peak of frenzied raving that is captured musically in a breathless prestissimo (Ex. 9-2) that returns to the opening patter tune of the finale, thus tying the whole imbroglio into a tidy musical package.

EX. 9-2 Niccolò Piccinni, La buona figliuola, Act II finale

The comédie larmoyante was only one of many new departures in theater and theatrical music that burgeoned shortly after the middle of the eighteenth century. Another came to a head in an opera—ostensibly, an opera seria—that had its première performance in Vienna two years later than La buona figliuola, and is remembered today as the very model of “reform” opera, thanks to a deliberate propaganda campaign mounted on its behalf by the composer, the librettist, and their allies in the press. Although in many ways almost diametrically opposed to the style and the attitudes of Piccinni’s masterpiece of sentimental comedy, it embodied a similar infusion of what was known as “sensibility.” It too was in its way a quest for the “natural” and the “authentic.”

The opera was called Orfeo ed Euridice, a knowing retelling of the legend that had midwifed the very birth of opera a century and a half before. The composer was Gluck, who was famous for declaring that when composing he tried hard to forget that he was a musician. What he meant by that, of course, was that he strove to avoid the sort of decorative musicality that called attention to itself—and away from the drama. The implicit target of Gluck’s reform, like that of the comic opera in all its guises, was the Metastasian opera seria and all its dazzling artifices.

But where the buffa, as practiced by Piccinni, sought to replace those artifices with the “modern” truth of the sentimental novel, Gluck sought to replace them by returning to the most ancient, uncorrupted ways, as then understood. His was a self-consciously “neoclassical” art, stripped down and, compared with the seria, virtually denuded. In the prefaceto Alceste (1767), his second “reform” opera (based on a tragedy by Euripides), Gluck declared that in writing the music he had consciously aimed “to divest it entirely of all those abuses, introduced either by the mistaken vanity of singers or by the too great complaisance of composers, which have so long disfigured Italian opera and made the most splendid and most beautiful of spectacles the most ridiculous and wearisome,” just as his librettist, Ranieri Calzabigi, had sought to eliminate “the florid descriptions, unnatural paragons and sententious, cold morality” of the unnamed but obviously targeted Metastasio.4

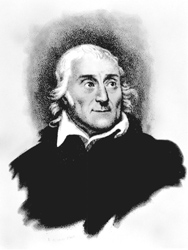

FIG. 9-1 Christoph Willibald Gluck, by Joseph Siffred Duplessis (1725–1802)

Thus in place of the elaborate hierarchy of paired roles that Metastasio had decreed, Gluck’s Orfeo has only three characters—the title pair plus Cupid, the hero’s ally in his quest. The music they sing, despite the loftiness of the theme, is virtually devoid of the ritualized rhetoric of high passion—namely, the heroic coloratura that demanded the sort of virtuoso singing that had brought the opera seria its popular acclaim and its critical disrepute. That sort of musical “eloquence” was now deprecated as something depraved if not downright lubricious, and shed. Gluck’s “reform” was in fact a process of elimination.

Gluck’s ideals, and (even more) his rhetoric, derived from the ideals and rhetoric of what in his day was called “the true style” by its partisans. (Only later, in the nineteenth century, was it labeled “neoclassic” or “classical,” and then only to deride it). The high value of art, in this view, lay in its divine power, sadly perverted when art was used for purposes of display and luxury. The legitimate connection between this attitude and notions of classicism or antiquity came about as a result of contemporary achievements in archaeology (most spectacularly the unearthing of Herculaneum and Pompeii between 1738 and 1748) and the theories to which they gave rise.

The main theorizer was the German archaeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–68), Gluck’s near-exact contemporary, whose most influential work in esthetics, Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works, appeared in 1755. The phrase he used to summarize the qualities in Greek art that he wanted to see imitated—“a noble simplicity and a calm grandeur” (eine edle Einfalt und eine stille Grösse)—became a watchword of the age, echoed and re-echoed in the writings of his contemporaries, including Gluck.

(There was a characteristic irony here, since many of the features of Greek art and architecture that Winckelmann most admired—its chaste “whiteness,” for example—were the fortuitous products of time, not of the Greeks; we now know that the Athenian Parthenon, Winckelmann’s very pinnacle of white plainness and truth, was actually painted in many colors back when it functioned as a temple rather than a “ruin.” The “classicism” of the eighteenth century, a classicism of noble ruins, was in every way that very century’s tendentious creation.)

Yet the heritage of the opera seria nevertheless survives in Gluck’s Orfeo—most obviously in the language of the libretto, but also in the use of an alto castrato for the male title role, and in the high ethical tone that continues, newly purified and restored, to reign over the telling of the tale. Where Peri’s or Monteverdi’s Orpheus had looked back on Eurydice and lost her again out of sheer weakness (the inability to resist a spontaneous impulse), Gluck’s hero does so out of stoic resolution and strength of character: in response to Eurydice’s bewildered entreaties, Orpheus turns and looks to reassure her of his love, even though it means he must lose her. His act, in other words, has been turned into one of noble self-sacrifice: the classic seria culmination.

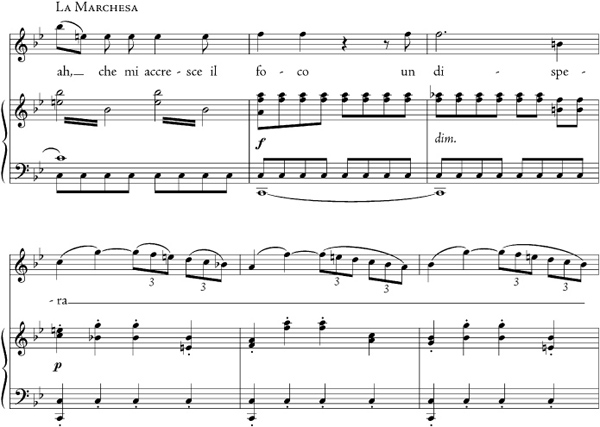

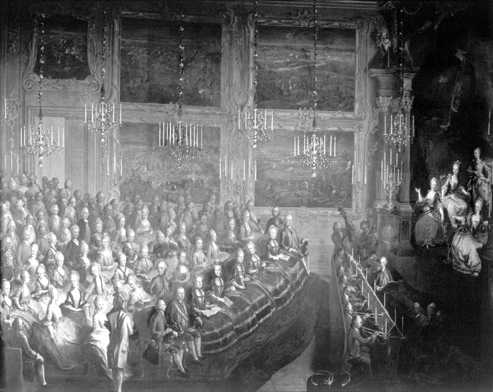

In other ways, the opera follows the conventions of the French tragédie lyrique, the majestic spectacle of the “ancient” and “divine” Lully, lately declared a classical model for imitation by French artists eager to relive the glorious achievements of the “grand siècle,” the Great Age of Louis XIV. This unique mixture of what were normally considered inimical ingredients was typical of Gluck, the ultimate cosmopolitan. He had grown up in Austrian Bohemia. According to his pupil Antonio Salieri, his native language was Czech; “he expressed himself in German only with effort, and still more so in French and Italian …. Usually he mixed several languages together during a conversation.”5And so he did in his music, too.

FIG. 9-2 Gluck’s Il Parnasso confuso as performed at the Schönbrünn Palace, Vienna, in 1765.

His early career was practically that of a vagabond: from Prague to Vienna, from Vienna to Milan (where he worked with Giovanni Battista Sammartini, one of the lions of the operatic stage), from Milan to London (where his operas failed, but where he met Handel), thence as far north as Copenhagen and as far south as Naples. By 1752 he had resettled in Vienna, where he worked mostly as staff composer for a troupe of French actors and singers for whom he composed ballets and opéras comiques. That is where he absorbed the idioms of French musical theater.

The tragédie lyrique, the type of French musical theater Gluck chose to emulate in Orfeo, was, as we know, the courtliest of all court operas, and it might seem that Gluck’s reform was aimed in the opposite direction from Piccinni’s innovations. It was to be a reassertion of the aristocratic values that the latter-day seria had diluted with singerly excess, the values that the opera buffa owed its very existence to deriding. Here the main impetus came from Gluck’s librettist, Calzabigi, an Italian-born poet then resident in Vienna, who had boldly set himself up as rival to the lordly court poet Metastasio. Calzabigi had actually trained in Paris, where he had learned to value the “Greek” dancing-chorus manner of the French opera-ballet over “i passaggi, le cadenze, i ritornelli and all the Gothick, barbarous and extravagant things that have been introduced into our music” by the pleasureloving, singer-pleasing Italians, as he put it in a memoir of his collaboration with Gluck, published years later in a French newspaper.6 (The English translation is by Dr. Burney.)

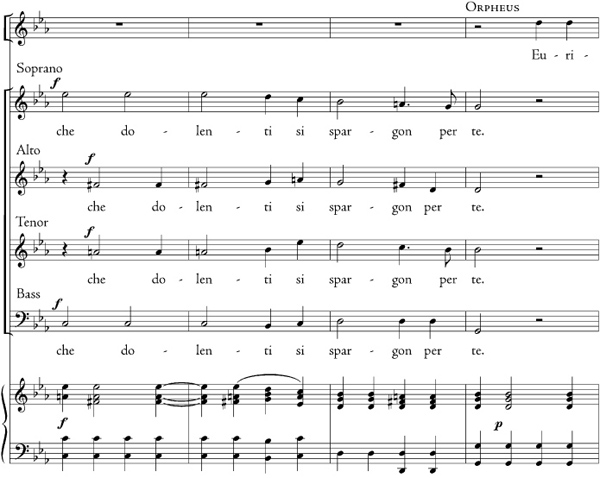

Thus the very first scene in the Gluck-Calzabigi Orfeo is a very formal choral elegy, sung by Orpheus’s entourage of nymphs and shepherds, that corresponds roughly with the one at the end of the second act of Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Eurydice is already dead. The horrifying news of her demise and Orpheus’s reaction to it, so central to Monteverdi’s confrontational drama, is dispensed with so far as the spectacle is concerned. This will be an opera of reflection—of moods savored and considered, not instantaneously experienced.

The aim of austerity—of striking powerfully and deep with the starkest simplicity of means—is epitomized by the role of Orpheus in this first scene. His whole part amounts to nothing more than three stony exclamations of Eurydice’s name—twelve notes in all, using only four pitches (Ex. 9-3). It would be hard to conceive of anything more elemental, more drastically “reduced to essentials.” Gluck once advised a singer to cry the name out in the tone of voice he’d use if his leg were being sawn off—Diderot’s “animal cry of passion” in the most literal terms.

Orpheus then sends his mourning friends away in a grave recitative, whereupon they take their ceremonious leave of him through another round of gravely eloquent song and dance à la française. Orpheus’s recitative is accompanied by the orchestral strings with all parts written out, not just a figured bass. “Accompanied” or “orchestrated recitative” (recitativo accompagnato or stromentato) had formerly been reserved for just the emotional highpoints of the earlier seria, to set these especially fraught moments off from the libretto’s ordinary dialogue, for which ordinary or “simple” recitative—recitativo semplice, later known as recitativo secco or “dry” recitative—would have sufficed. In Gluck’s opera, there was to be no “ordinary” dialogue, only dialogue fraught heavily with sentiment, hence no recitativo semplice, only stromentato.

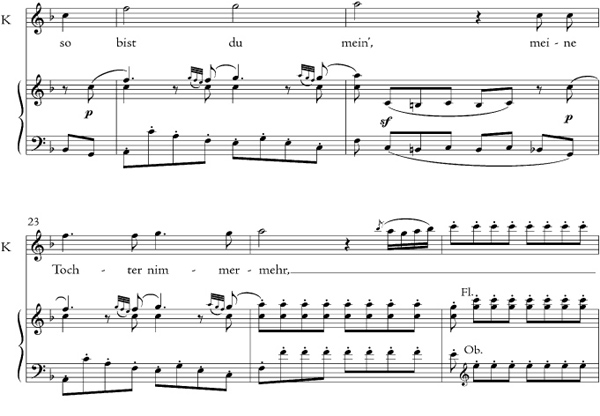

EX. 9-3 Christoph Willibald Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice, Act I, scene 1, chorus, recitative and pantomime

As a result, Orfeo ed Euridice became the first opera that can be performed without the use of any continuo-realizing instruments. Considering that the basso continuo and the opera itself arose side by side as kindred responses to the same esthetic ferment, there could hardly be any greater “reform” of the medium than this. Paradoxically, the elimination of the continuo had the same purpose as its invention: to adapt an existing (but constantly changing) medium to ever greater, and ever more naturalistic, expressive heights.

The same combination of high pathos and avoidance of conventional histrionics characterizes both of Orpheus’s arias. The one in the third act, which takes place after Eurydice’s second death, was very aptly described by Alfred Einstein, an admiring biographer of the composer, as “the most famous and most disputed number of the whole opera,” possibly of all opera (Ex. 9-4).7 Orpheus sings in grief—but in a noble, dignified grief that is in keeping with the nobility of his deed. That nobility and resignation constitute the aria’s dominant affect, expressed through a “beautiful simplicity” (bella simplicità) of musical means, as Gluck put it (after Winckelmann, with Calzabigi’s help) in the preface to Alceste. And that meant no Metastasian similes, no roulades, no noisy exits—for such things only exemplified pride.

The structure of the aria is French, not Italian: a rondeau with a periodic vocal refrain, not a da capo with an orchestral ritornello. The episodes between refrains are set in related keys—the dominant, the parallel minor—so that the return is always a refreshment. That and the shapely C-major melody of the refrain are what have given rise to the “dispute” to which Einstein referred—a dispute between those who have found its “beautiful simplicity” simply too beautiful (and not expressive enough), and those who have seen in it the ultimate realization of music’s power of transcendence.

EX. 9-4 Christoph Willibald Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice, Act III, scene 1: “Che faro senza Euridice?”, refrain, mm. 7–16

The French composer Pascal Boyé, a friend of Diderot, used the aria as ammunition for a treatise entitled L’expression musicale mise au rang des chimères (“Musical expression exposed as an illusion”). Citing the aria by the opening words of the French version premièred in Paris in 1774—“J’ai perdu mon Eurydice!” (I’ve lost my Eurydice!)—Boyé commented drily that the melody would have served as well or better had the text read “I’ve found my Eurydice!”8 Nearly a century later, the critic Eduard Hanslick tried to generalize this remark of Boyé’s and apply it to all music. “Take any dramatically effective melody,” he suggested:

Form a mental image of it, separated from any association with verbal texts. In an operatic melody, for instance one that had very effectively expressed anger, you will find no other intrinsic expression than that of a rapid, impulsive motion. The same melody might just as effectively render words expressing the exact opposite, namely, passionate love.9

And so on. Gluck would surely have found this notion bizarre, and might well have attributed it to the inability of “bourgeois” ears to appreciate a noble simplicity of utterance, awaiting completion (as Boyé recognized, but not Hanslick) by the expressivity of the singer’s voice and manner. The singer for whom the aria was written, it so happens, is one whom we have already met—Gaetano Guadagni, for whom, a dozen years before, Handel had revised Messiah for showy “operatic” effect. Over that time Guadagni had transformed himself into a paragon of nobly simple and realistic acting under the influence of David Garrick, the great Shakespearean actor, with whom he had worked in London and whose then revolutionary methods of stage deportment he had learned to emulate. These, too, could be described with the phrase bella simplicità. A comparison of Handel’s revised “But who may abide” (Ex. 7-6b) and Gluck’s Che farò senza Euridice?, both written for Guadagni, makes a good index of simplicity’s ascendancy. It was resisted by many among the aristocracy, however, who associated “natural” acting and stage deportment with comedy, and therefore with a loss of high “artfulness.”

Piccinni’s rustic sentiment and Gluck’s classical simplicity, though the one was directed at a bourgeois audience and the other at an aristocratic one, were really two sides of the same naturalistic coin. Both were equally, though differently, a sign of the intellectual, philosophical, and (ultimately) social changes that were taking place over the course of the eighteenth century. The famous rivalry that marked (or marred) their later careers might thus seem entirely gratuitous and therefore ironic from our historical vantage point. But although the two composers could have had no inkling of it in the 1760s, when they first became international celebrities, they were on a collision course.

Gluck naturally gravitated toward Paris, the half-forgotten point of origin for most of his innovatory departures. Having Gallicized the opera seria, he would now try his hand at the real thing—actual tragédies lyriques, some of them to librettos originally prepared as much as ninety years earlier for Lully. He arrived in the French capital in 1773 at the invitation of his former singing pupil in Vienna, none other than the princess Marie-Antoinette, the eighteen-year-old wife of the crown prince (dauphin) who the next year would be crowned Louis XVI (“Louis the last,” as it turned out).

Under Marie-Antoinette’s protection, Gluck at first enjoyed fantastic success. He even got old Rousseau to recant the brash claim he had made twenty years before, in the heat of buffoon-battle. After seeing Iphigénie en Aulide, Gluck’s first tragédie lyrique, on a much-softened libretto after Euripides’s bloody tragedy of sacrifice (adapted by Jean Racine), Rousseau confessed to Gluck that “you have realized what I held to be impossible to this very day”—namely, a viable opera on a French text.10 The irony was that the same stylistic mixture that had spelled “Gallic” reform of Italian opera in Vienna was now read by the French as a revitalizing Italianization of their own heritage. Only a Bohemian—a complete outsider to both proud traditions—could have brought it off.

The best symbol of this hybridization of idioms was Orphée et Eurydice, a new version of Gluck’s original “reform” opera, which amounted to a French readaptation of what had already been a Gallicized version of opera seria. Besides translating the libretto, this meant recasting the male title role so that an haut-contre, a French high tenor, could sing it instead of a castrato. Gluck also added some colorfully orchestrated instrumental interludes portraying the beauties of the Elysian fields, which are now performed no matter which version of the opera is employed.

In the summer of 1776, Gluck learned that the Neapolitan ambassador had summoned Piccinni to Paris for no other purpose than to be Gluck’s rival, and had even “leaked” to him a copy of the very libretto Gluck was then working on (Roland, adapted from a tragédie lyrique formerly set by Lully, with a plot taken from French medieval history). Gluck, mortified, pulled out of the project, feeling with ample justification that he was being set up for a flop. “I feel certain,” he wrote to one of his old librettists after burning what he’d written of the opera, “that a certain Politician of my acquaintance will offer dinner and supper to three-quarters of Paris in order to win fans for M. Piccinni ….”11 A couple of years later, though, it happened again, when Piccinni was induced to write an opera on the same story (albeit to a different libretto) as Gluck’s last Parisian offering, a mythological tragedy loosely based on Iphigenia in Tauris, afamous play by Euripides whose story had already furnished the plot for quite a number of operas. The two settings were performed two years apart, Gluck’s in 1779 and Piccinni’s in 1781.

Their partisans (especially Jean François Marmontel, Piccinni’s French librettist and sponsor) worked hard to cast the two composers as polar opposites—Gluck as the apostle of “dramatic” opera, Piccinni of “musical.” Compared with the Querelle des Bouffons, however, the querelle des Gluckistes et Piccinistes was just a tempest in a teapot. The stakes, for one thing, were much lower. The main battle—the “noble simplification” and sentimentalization of an encrusted court art—was won before this later quarrel even started, and its protagonists, privately on friendly terms, were more nearly allies than rivals.

So perhaps it is from the operatic masterpieces of the age that we can best learn an important lesson: it is a considerable distortion of the way things were to describe the so-called Enlightenment exclusively as an “age of reason”—especially if we persist in assuming (as the romantics would later insist) that thinking and feeling, “mind” and “heart,” are in some sense opposites. Gluck and Piccinni show us how far from true this commonly accepted dichotomy really is. The impulse that had led them and their artistic contemporaries to question traditional artifice and attempt the direct portrayal of “universal” human nature was equally the product of “free intellect” and sympathy—community in feeling. This last was based on introspection—“looking within.” The community it presupposed and fostered was one that in principle embraced the whole of humanity regardless of race, gender, nationality, or class. The objective of “enlightened” artists became, in Wye J. Allanbrook’s well-turned phrase, “to move an audience through representations of its own humanity.”12 And not only move, but also instruct and inspire goodness: free intellect and introspective sympathy went hand in hand—or in a mutually regulating tandem—as ministers to virtue.

The notion of free intellect—or “Common Sense,” as the American revolutionary Thomas Paine put it in the title of his celebrated tract of 1776—was the one that tended to attract attention by dint of its novelty and its political implications. “Man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains,” wrote Rousseau at the beginning of his Social Contract (1762), perhaps the most radical political work of the eighteenth century, and the obvious source of Paine’s main ideas. The chains to which he referred were not only the literal chains of enforced bondage, but also intellectual chains that people voluntarily (or so they may think) assume: religious superstition, submission to time-honored authority, acquiescence for the sake of social order or security in unjust or exploitative social hierarchies. The remedy was knowledge, which empowered an individual to act in accord with rational self-interest and with the “general will” (sensus communis) of similarly enlightened individuals.

Dissemination of knowledge—and with it, of freedom and individual empowerment—became the great mission of the times. The most concrete manifestation of that mission was the Encyclopédie, the mammoth encyclopedia edited by Diderot and Jean d’Alembert with help from a staff of self-styled philosophes or “lovers of knowledge” including Rousseau, who wrote the music articles among others. The first volume appeared in 1751, and the final supplements were issued in 1776. By the end, the project had been driven underground, chiefly by the Jesuits, who were enraged at its religious skepticism and persuaded the government of Louis XV to revoke the official “patent” or license to print. Even the clandestine volumes were subjected to unofficial censorship by the printer, who in fear of reprisal deleted the most politically inflammatory passages. These embattled circumstances only enhanced the prestige of the Encyclopédie, giving it a heroic aura as a new forbidden “Tree of Knowledge,” and contributing to its enormous cultural and political influence.

That influence can be gauged by comparison with the famous essay Was ist Aufklärung? (“What Is Enlightenment?”) by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. It was published in 1784, eight years after the Encyclopédie was completed. The answer to the question propounded by the title took the form of a popular Latin motto, originally from Horace: Sapere aude! (“Dare to know!”).13 “Enlightenment,” Kant declared, “is mankind’s exit from its self-incurred immaturity,” defined as “the inability to make use of one’s own understanding without the guidance of another.”

“Enlightened” ideas quickly spread to England as well, where free public discussion of social and religious issues—both in the press and also orally, in meeting places like coffee houses—was especially far advanced. From England, of course, they spread to the American colonies, as already suggested by comparing Rousseau and Paine. Whether or not (as often claimed in equal measure by its proponents and detractors) the Enlightenment led directly to the French revolution of 1789, with its ensuing periods of mob rule, political terror, and civil instability, there can be no doubt that it provided the intellectual justification for the American revolution of 1776—a revolution carried out on the whole by prosperous, enterprising men of property and education, acting in their own rational and economic self-interest. The Declaration of Independence, and the American Constitution that followed, can both be counted as documents of the Enlightenment. As mediated through two centuries of amendment and interpretation, moreover, the American Constitution, as a legal instrument that is still in force, represents the continuing influence of the Enlightenment in the politics and social philosophy of our own time.

It would be wrong, however, to think of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment within its own time as nothing but a vehicle of civic unrest or rebellion. The philosophes themselves believed in strong state power and saw the best realistic hope of freedom in the education of “enlightened despots” who would rule rationally, with enlightened sympathy for the interests of their subjects. A number of European sovereigns were indeed sympathetic to the aims of the Encyclopedists. Frederick II (“the Great”) of Prussia—C. P. E. Bach’s employer and a great patron of the arts and sciences, many of which (including flute-playing and even musical composition) he practiced himself—corresponded with Voltaire (François Marie Arouet, 1694–1778), the “godfather” of the Enlightenment, and entertained d’Alembert at Sans Souci (“Without-a-Care”), his pleasure palace in Potsdam. Catherine II (“the Great”), the German-born Empress of Russia and a protégée of Frederick’s, corresponded enthusiastically with Diderot himself, whose much-publicized praise of Catherine and her liberality was largely responsible for her flattering sobriquet.

The liberality of an autocrat had its limits, though. Kant was a bit cynical about Frederick’s: “Our ruler,” he wrote, “says, ‘Argue as much as you want and about whatever you want, but obey!’”14 And after the French revolution, which Frederick did not live to see, his protégée Catherine turned quite reactionary and imprisoned many Russian followers of her former correspondents.

The prototype of all the “enlightened despots” of eighteenth-century Europe was the Austrian monarch, Joseph II (reigned 1765–90). Beginning in 1780, when he came to full power on the death of his mother, the co-regent Maria Theresia, Joseph instituted liberal reforms on a scale that seemed to many observers positively revolutionary in their extent and speed. He wielded the powers of absolutism, just as the philosophes had envisaged, with informed sympathy for the populace of his lands. He annulled hereditary privileges, expropriated church properties and extended freedom of worship, and instituted a meritocracy within the empire’s civil service. Above all, he abolished serfdom. (Catherine, by contrast, notoriously extended the latter institution into many formerly nonfeudalized territories of the Russian empire.) Yet few of Joseph’s reforms outlived him, largely because his brother and successor, Leopold II, was impelled, like Catherine, into a reactionary stance by the revolutionary events in France, and Leopold’s successor Francis II (reigned 1792–1835) created what amounted to the first modern police state. This anxious response to the French Revolution on the part of formerly “enlightened” autocrats is one of many reasons for regarding the political legacy of that great historical watershed as ambiguous at best.

Joseph II was not a great patron of the arts. His sociopolitical reforms were his all-consuming interest, leaving little room for entertainment or intellectual pursuits. Music historians have tended to despise him a bit, because of his failure to give proper recognition or suitable employment to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–91), the great musical genius of the age, whose music often perplexed him. (Joseph II is now best remembered by musicians not for his heroic reforms but rather for telling Mozart one day that there were “too many notes” in one of his scores.) But in fact Josephine Vienna, where Mozart made his home in the last decade of his life, and to whose musical commerce he made an outstanding contribution despite his failure to achieve a court sinecure, provides an ideal lens through which to view the work of one of European music’s great iconic figures in a truly relevant—and “enlightening”—cultural context.

FIG. 9-3 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Posterity has turned Mozart into an “icon”—the “image of music,” replete with an aura of holiness—for many reasons. One was his phenomenal precociousness; another was his heartbreaking premature demise. These as-if-correlated facts have long since converted his biography into legend. His earliest surviving composition, an “Andante pour le clavecin” in his sister Nannerl’s notebook, was composed just after his fifth birthday (if his father, who inscribed the little harpsichord piece, can be believed). His last, as fate would have it, was a Requiem Mass, on which he was still working when he died, just 30 years, 10 months, and one week later. In that short span Mozart managed to compose such a quantity of music that it takes a book of a thousand pages—the Chronological-Thematic Catalogue by Ludwig Köchel, first published in 1862 and now in its seventh revised edition—just to list it adequately. And that quantity is of such a quality that the best of it has long served as a standard of musical perfection.

FIG. 9-4 Mozart as a boy in Salzburg court uniform.

Mozart was born in Salzburg, an episcopal city-state near the Bavarian border, where his father, Leopold Mozart, served as deputy music director in the court of the Prince-Archbishop. By 1762, when the child prodigy was six years old, his father relinquished most of his duties and gave up his own composing career so that he could not only see properly to his son’s musical education but also begin displaying his astonishing gifts to all the courts and musical centers of Europe. By the age of ten the boy Mozart was famous, having performed at courts throughout the German Catholic territories, the Netherlands, Paris, and finally London, where he stayed for more than a year, was fêted at the court of George III, became friendly with John Christian Bach, and submitted, at his father’s behest, to a series of scientific tests by the physician and philosopher Daines Barrington, to prove that the boy truly was a prodigy and not a musically accomplished dwarf. Barrington’s report, “Account of a Very Remarkable Musician,” read at the Royal Society, a prestigious scientific association, marked an important stage in the formation of the Mozart legend, the “myth of the eternal child,” as Maynard Solomon, the author of an impressive psychological biography of the composer, has called it.15

It is because of his uncanny gifts and his famously complicated relations with his father that Mozart has been the frequent subject of fiction, dramatization, “psychobiography,” and sheer rumor (including the persistent legend of his death by poisoning at the hand of Gluck’s pupil Salieri, a jealous rival). Before Solomon’s sober psychological study there was a reckless one by the Swiss novelist Wolfgang Hildesheimer, not to mention Alexander Pushkin’s verse drama “Mozart and Salieri” of 1830 and its subsequent Broadway adaptation by Peter Shaffer as Amadeus, later a popular movie. But Mozart’s iconic status was also due to his singular skill at “moving an audience by representations of its own humanity.” His success at evoking sympathy through such representations has kindled interest in his own human person to an extent to that point unprecedented in the history of European music, partly because the creation of bonds of “brotherhood” through art had never before been so central an artistic aim.

It is also for this reason that Mozart’s music, in practically every genre that he cultivated, has been maintained in an unbroken performing tradition from his time to ours; he is the true foundation of the current “classical” repertoire, and has been that ever since there has been such a repertoire (that is, since the period immediately following his death). Except for Handel’s oratorios, nothing earlier has lasted in this way. Franz Joseph Haydn, Mozart’s great contemporary, whom we will meet officially in the next chapter, has survived only in part. (His operas, for example, have perished irrevocably from the active repertoire.) Bach, as we know, returned to active duty only after a time underground.

Mozart’s operas have not only survived where Haydn’s have perished. A half dozen of them (roughly a third of his output in the genre) now form the earliest stratum of the standard repertory. But for the Orfeos of Monteverdi and Gluck, they are the earliest operas now familiar to theatergoers. They sum up and synthesize all the varieties of musical theater current in the eighteenth century, as we have traced them to this point, and they have been a model to opera composers ever since.

Mozart composed his first dramatic work, a rather offbeat intermezzo composed to a libretto in Latin (!) for performance at the University of Salzburg, at the age of eleven, shortly after returning from London. It is a mere curiosity, like the composer himself at that age. Within a couple of years, however, Mozart was equipped to turn out works of fully professional calibre in all the theatrical genres then current. In 1769, the thirteen-year-old’s first opera buffa, La finta semplice (“The pretended simpleton”), to a libretto by Carlo Goldoni, was performed at the Archbishop’s Palace in Salzburg. (An earlier scheduled performance at Vienna was cancelled on suspicion that the opera was really by father Leopold.) Its style is most often compared with that of Piccinni. About eighteen months later, in December 1770, Mozart’s first opera seria, called Mitridate, re di Ponto (“Mithridates, King of Pontus”), to a libretto based on a tragedy of self-sacrifice by Racine, was produced in Italy, opera’s home turf, where the Mozarts, father and son, were touring. It was so successful that the same theater, that of the ducal court of Milan, commissioned two more serie from the boy genius over the next two seasons. Another early success was Bastien und Bastienne, a singspiel (a German comic opera with spoken dialogue) based loosely on the libretto of Rousseau’s popular Devin du village, whichwas performed, possibly as early as the fall of 1768 when the composer was twelve, at the luxurious home of Franz Mesmer, the pioneer of “animal magnetism” or (as we would now call it) hypnotherapy.

These three—Italian opera both tragic and comic, and German vernacular comedy—were the genres that Mozart would cultivate for the rest of his career. What his early triumphs demonstrated above all was his absolute mastery of the conventions associated with all three: a mastery that enabled him eventually to achieve an unprecedented directness of communication that still moves audiences long after the conventions themselves have been outmoded. Mastery, rather than originality, was the objective all artists then strove to achieve. The originality we now perceive in Mozart was really a secondary function or by-product of a mastery so consummately internalized that it liberated his imagination to react with seeming spontaneity to the texts he set and achieve a singularly sympathetic “representation of humanity.”

Mozart’s first operatic masterpiece was Idomeneo, re di Creta (“Idomeneus, King of Crete”), an opera seria composed in 1780, first produced in Munich in 1781 and extensively revised five years later for performance in Vienna. By then, having quarreled over terms with the Archbishop of Salzburg and having requested and ungraciously received release from his position (“with a kick in the ass,” he wrote to his horrified father), Mozart, with a wife and eventually a child to support, was living in the capital as a “free lance” musician, accepting commissions and giving “academies,” or self-promoted concert appearances. Although he had craved the freedom to compose as he saw fit, the precariousness of his livelihood (exacerbated by gambling debts) and the attendant stress and overwork undoubtedly contributed to his early death, adding another leaf to the legend of his life—a legend that maintains, romantically but erroneously, that he died a pauper.

Idomeneo, a tragedy of child-sacrifice, was composed to a translation of a very old libretto, one that had served almost seventy years earlier as the basis of a tragédie lyrique (with music by André Campra) that was performed before Louis XIV during the last years of his reign (see Ex. 3-5). Mozart cast his opera, accordingly, in the severe style of Gluck’s neoclassical “reform” dramas, two of which (on the myth of Iphigenia) had also treated the painful subject of a father sworn to sacrifice his child. By modeling his opera on Gluck’s, Mozart completed his assimilation of all the theatrical idioms to which he was heir.

FIG. 9-5 Act II of Mozart’s Idomeneo as staged at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York.

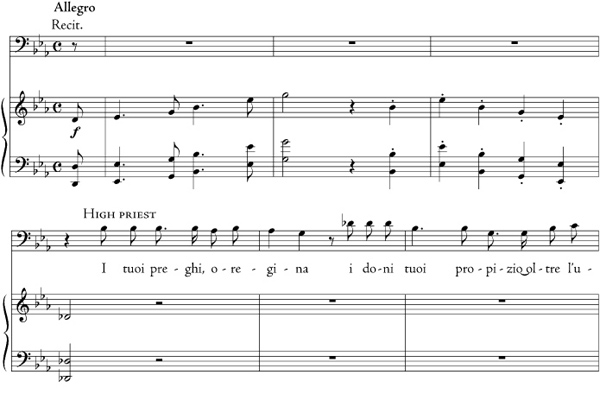

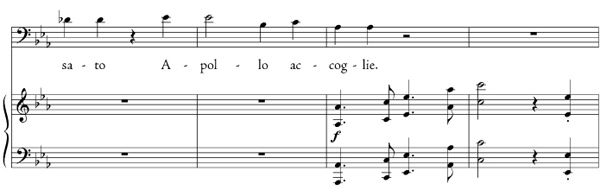

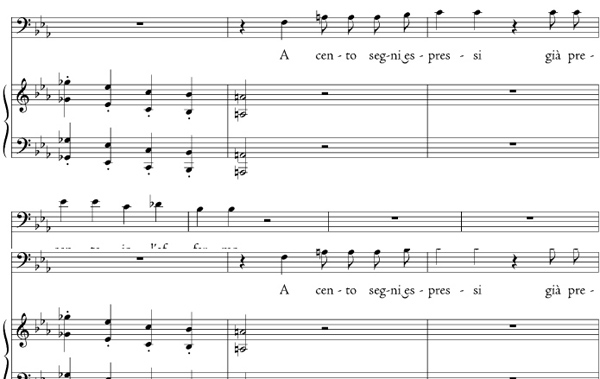

At Mozart’s request, his librettist, a Salzburg friend, added several choruses to the original libretto and also provided some exalted accompanied recitatives for a high priest and an oracle. As Daniel Heartz has shown, prototypes for all of these interpolations and more can be found in the French version of Gluck’s Alceste, performed in Paris in 1776. This was the opera that carried, in the first edition of its score, the preface that set forth Gluck’s famous principles of operatic reform. It had enormous prestige. Mozart’s successful appropriation of Gluck’s ideals and methods, in a manner that vividly illustrates the eighteenth century’s outlook on artistic creativity, not only transcended his predecessor’s achievement but at the same time went a long way toward transforming the reformer’s innovations into conventions.

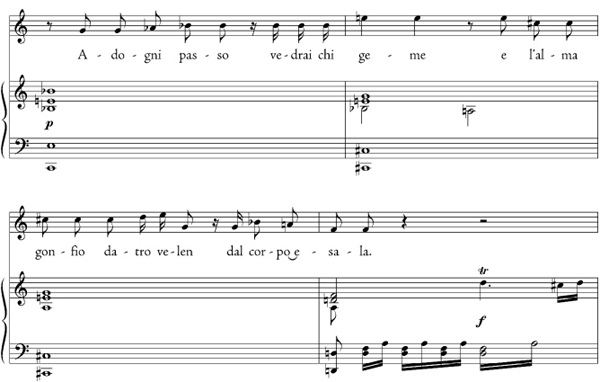

Both Mozart’s indebtedness to Gluck and the astonishing boldness with which the twenty-four-year-old former prodigy exceeded his model can be judged from the High Priest’s chilling recitative in the third act of Idomeneo, in which he exhorts the title character not to shrink from his obligation, incurred by a rash vow, to sacrifice his son Idamante to the god Neptune. It is modeled on the lengthy temple scene in the first act of Alceste, in which the high priest of Apollo issues a similar exhortation to the title character to prepare to sacrifice her life so that her husband, King Admetus of Thessaly, may recover from an illness and continue his propitious reign. Mozart in effect conflates several moments from Gluck’s scene, of which the most prominent is an imperious unison arpeggio figure that modulates to the dark key of B minor (Ex. 9-5).

minor (Ex. 9-5).

EX. 9-5A Christoph Willibald Gluck, Alceste, ActI, scene 4, High Priest’s exhortation, mm. 1–18

EX. 9-5B W. A. Mozart, Idomeneo, no. 23, mm. 2–23

Mozart’s intensification of the harmony, his transformation of the leading motive by obsessively repeating a nasty unison trill, and his antiphonal deployment of it over a restless modulation all contribute to a gruesome effect that some have interpreted as sarcastic, in keeping with the composer’s presumed enlightened attitudes. The trills, according to Heartz, “tell us pretty plainly what Mozart thought of this particular high priest and how we are to respond to the ‘holy’ crime he exhorts.”16 Heartz relates this observation to a remark by Mozart’s older contemporary, Baron Melchior von Grimm (1727–1807), one of the leaders of the German enlightenment who, as a result of his devotion to Voltaire, Rousseau, and Diderot, became a naturalized citizen of France. “What I want to see painted in the tragedy of Idomeneo,” Grimm wrote, “is that dark spirit of uncertainty, of fluctuation, of sinister interpretations, of disquiet and of anguish, that torments the people and from which profits the priest.”17

Whether Mozart’s portrayal of the high priest actually intends or conveys such a judgment may be debated. What is certain, however, is that dramas like Idomeneo were becoming unfashionable in enlightened Vienna, where Mozart would shortly establish his permanent residence. Joseph II had an aversion to the opera seria (ostensibly because of its costliness). Although Mozart made an elaborate revision of Idomeneo in hopes of a performance in the capital, he succeeded only in having it done privately (possibly in concert form, as a sort of oratorio) at one of Vienna’s noble residences during Lent in 1786 when the theaters were closed. Not until the end of Joseph’s reign would Mozart have another opportunity to compose in the tragic style.

The 1780s, then, became Mozart’s great decade of comic opera, a genre he utterly transformed. First to appear was a singspiel, composed in response to Joseph II’s avid patronage of vernacular comedies, for which the Emperor had established a special German troupe at the Vienna Burgtheater (Court Theater), henceforth to be officially—though never colloquially—named the “Nationaltheater.” It was there that Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (“The abduction from the Seraglio”) was first performed, on 16 July 1782. (The production was to have been mounted in honor of the visiting Grand Duke Pavel Petrovich of Russia, who would later reign briefly as Tsar Paul I, but the visit was delayed.)

Although composed in the national language and performed in the national theater, the opera has an exotic rather than a national subject and locale. There had long been a great Viennese vogue for “Oriental” (or “Turkish”) subject matter in the wake of the unsuccessful siege of the city by the Ottoman Turks in 1683. Making fun of the former enemy was a national sport, and Turkish military (or “Janissary”) percussion instruments that had once struck fear in the hearts of European soldiers were now appropriated by European military bands—and eventually by opera orchestras. (The Janissaries, from the Turkish for “recruits,” were originally Christian captives pressed into military service by the Ottoman Empire and forced to convert to Islam; the drafting of Christians waned during the seventeenth century, and the regiment gradually became the hereditary elite corps of the Turkish army.)

FIG. 9-6 The Vienna Burgtheater in 1783, engraving by Carl Schuetz (1745–1800).

The raucous jangling of the Janissary band (also imitated in a piano sonata by Mozart, concluding with a famous “Rondo alla Turca” that children often learn) is a special effect in the merry overture to Die Entführung (whose orchestra includes timpani, bass drum, cymbals, and triangle) and at various colorful points thereafter. The plot of the opera revolves around the efforts of Belmonte, a young Spanish grandee, to rescue Constanze, his beloved, who has been kidnapped by pirates, together with her English maidservant Blonde and Belmonte’s servant Pedrillo, and sold into the harem of Pasha Selim—who turns out to be a runaway Christian himself and shows the lovers mercy. In the end the Christian lovers are reunited: Belmonte with Constanze (who, true to her name, had remained faithful to him despite temptation) and Pedrillo with Blonde (who had been wooed by the blustery and ridiculous Osmin, the keeper of the harem).

While at work in Vienna on Die Entführung, Mozart kept up a lively correspondence with his father, back home in Salzburg. One of his letters, dated 26 September 1781, has become famous for its very revealing descriptions of the arias he was writing for the various characters. About the frenzied last section of Osmin’s rage aria in act I, where the “Janissary” instruments have a field day, he wrote:

Just when the aria seems to be over, there comes the allegro assai, which is in a totally different measure and in a different key; this is bound to be very effective. For just as a man in a towering rage oversteps all bounds of order, moderation and propriety, and completely forgets himself, so must the music too forget itself. But as passions, whether violent or not, must never be expressed in such a way as to excite disgust, and as music, even in the most terrible situations, must never offend the ear, but must please the hearer, or in other words must never cease to be music, I have gone from F (the key in which the aria is written), not into a remote key, but into a related one, not, however, into its nearest relative D minor, but into the more remote A minor.18

The oft-quoted words italicized above have been justly taken as a sort of emblem of “Enlightened” attitudes about art and its relationship to its audience. Bach, on one side of the Enlightenment, would have heartily disagreed; but so too would many composers on the other side of it, as we shall see, and even Mozart himself in at least one famous instance that we will encounter at the end of this chapter.

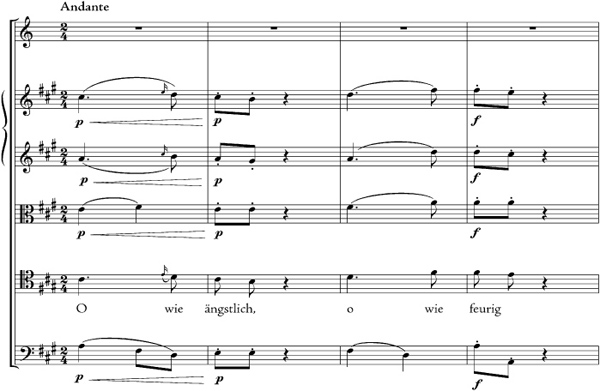

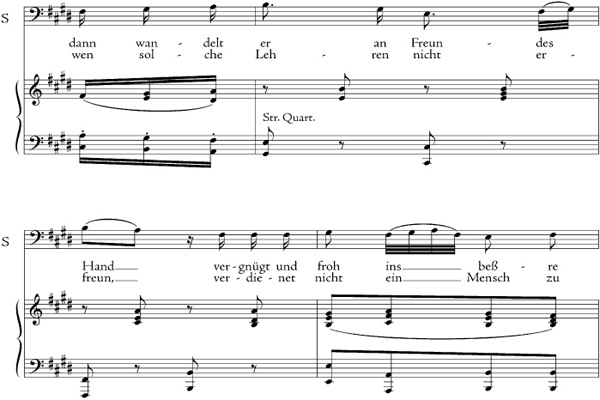

Mozart continues, in the same letter, with a description of the very next item in the singspiel, the brilliantly scored aria in which Belmonte expresses his anxieties about Constanze’s fate (Ex. 9-6 a and b). This passage from the letter has also become a locus classicus—a place everyone cites—for its account of how finely Mozart calculated the orchestral effects to imitate the physical manifestations (or, as psychologists would say, the “iconicity”) of Belmonte’s feelings.

Let me now turn to Belmonte’s aria in A major, “O wie ängstlich, o wie feurig.” Would you like to know how I have expressed it—and even indicated his throbbing heart? By the two violins playing octaves. This is the favorite aria of all those who have heard it, and it is mine also. You feel the trembling—the faltering—you see how his throbbing breast begins to swell; this I have expressed by a crescendo. You hear the whispering and the sighing—which I have indicated by the first violins with mutes and a flute playing in unison.19

EX. 9-6A W. A. Mozart, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Belmonte’s aria, “O wie ängstlich,” mm. 1–8

Mozart’s list is far from exhaustive. He might also have mentioned the harmonic shifts toward the minor as Belmonte’s thoughts darken, recalling the pain of separation. He might have mentioned the continuing heartbeat rhythm that underlies the “whispering and sighing” violins and flute, played by divided violas plucking four-part chords, pizzicato (Ex. 9-6b). (Such detailed writing for the lowly viola was practically unheard of at the time.) He might have mentioned the strangely lurching dynamic patterns and accents—an irregular pulse?—when Belmonte sings of trembling and wavering. The list could go on.

While not exactly a new technique—in cruder form we encountered it in the final duet from Pergolesi’s Serva padrona—Mozart’s mastery of iconic portraiture set a benchmark not only in subtle expressivity but in refinement of orchestration as well. These were new areas in which one could “move an audience through representations of its own humanity.” Mozart’s success was a dual one. In the first place it attracted, and continues to attract, an unprecedented “human interest” in the composer as a person. His portraits of his characters have been read, persistently though of course unverifiably, as self-portraits.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the biographical interpretations often advanced to explain his composing, in swift succession, exemplary works in two such contrasting genres as opera seria (Idomeneo) and singspiel (Die Entführung). With another composer, adept powers of assimilation and mastery of convention might suffice to explain it. With Mozart, “mere” mastery of convention does not seem sufficient to account for such immediacy and versatility of expression. And so the grim Idomeneo is associated with Mozart’s unhappy courtship of the German soprano Aloysia Weber, who spurned him in favor of the court actor and painter Joseph Lange, whom she married in 1780. And the blithesome Entführung is associated with Mozart’s

EX. 9-6B W. A. Mozart, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Belmonte’s aria, “O wie ängstlich,” mm. 29–37

Are such explanations necessary? Perhaps not, but they are certainly understandable. Not only do Mozart’s uncanny human portraits in sound seem to resonate with the reality of a concrete personality; they inspire empathy as well—and this was Mozart’s other breakthrough. One is apt to respond to a work by him not only by thinking “it’s about him,” but also by thinking that, somehow, “it’s about me.” The bond of kinship thus established between the composer’s subjectivity and the listener’s—a human bond of empathy seemingly capable of transcending differences in age, rank, gender, nation, or any other barrier—is supremely in the optimistic spirit of the Enlightenment. When the feat is duplicated in the wordless realm of instrumental music, as we shall see in the next chapter, instrumental music is invested with a sense of importance—indeed, of virtual holiness—it had never known before. We can begin to see why Mozart could be worshiped, particularly by his nineteenth-century posterity, as a kind of musical god who worked a beneficent, miraculous influence in the world.

After Die Entführung, Mozart did not complete another opera for four years. Part of the reason for the gap had to do with his burgeoning career in Vienna as a freelancer, which meant giving lots of concerts, which (as we will see) meant writing a lot of piano concertos. But it was also due to Joseph II’s unexpected disbanding of the national singspiel company and its replacement by an Italian opera buffa troupe at court whose regular composers Giovanni Paisiello, Vincente Martìn y Soler, and Antonio Salieri—Italians all (Martìn being a naturalized Spaniard)—had a proprietary interest in freezing out a German rival, especially one as potentially formidable as Mozart.

Mozart’s letters testify to his difficulty in gaining access to Lorenzo da Ponte (1749–1838, original name Emmanuele Conegliano), the newly appointed poet to the court theater. (There was a certain typically Joseph II symbolism in the fact that a specialist in opera buffa should have been chosen to replace the aged Metastasio, the paragon of the seria, who died in 1782 at the age of 84.) “These Italian gentlemen are very civil to your face,” Mozart complained to his father in 1783. “But enough—we know them! If Da Ponte is in league with Salieri, I shall never get anything out of him.”20 It was these letters, and the intrigues that they exposed, that led to all the gossip about Salieri’s nefarious role in causing Mozart’s early death, and all the dubious literature that gossip later inspired.

FIG. 9-7 Lorenzo da Ponte, engraving by Michele Pekenino after a painting by Nathaniel Rogers (Mozarteum, Salzburg).

Mozart’s wish to compete directly with “these Italians” is revealed in another passage from the same letter to his father, in which he described the kind of two-act realistic comedy (but frankly farcical, not “larmoyante”) at which he now aimed. This was precisely the kind of libretto that Da Ponte, a converted Venetian Jew, had adapted from the traditions he had learned at home and brought to perfection. In this he was continuing the buffa tradition of Carlo Goldoni, which sported lengthy but very speedy “action finales” at the conclusion of each act and a highly differentiated cast of characters. About this latter requirement Mozart is especially firm:

The main thing is that the whole story should be really comic, and if possible should include two equally good female parts, one of them seria, the other mezzo carattere. The third female character, if there is one, can be entirely buffa, and so may all the male ones.21

This mixed genre insured great variety in the musical style: a seria role for a woman implied coloratura and extended forms; buffa implied rapid patter; “medium character” implied lyricism. Da Ponte’s special gift was that of forging this virtual smorgasbord of idioms into a vivid dramatic shape.

Mozart (aided, according to one account, by the Emperor himself) finally managed to secure the poet’s collaboration in the fall of 1785. The project was all but surefire: an adaptation of La folle journée, ou le mariage de Figaro (“The madcap day; or, Figaro’s wedding”), one of the most popular comedies of the day. It was the second installment of a trilogy by the French playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732–99), of which the first installment, Le barbier de Séville (“The barber of Seville”), had already been turned into a hugely successful opera buffa by Paisiello (1782; first staged in St. Petersburg, Russia). These plays by Beaumarchais were the very epitome of that old standby, the servant-outsmarts-master routine, familiar on every operatic stage since the very earliest intermezzi: La serva padrona was of course the first classic of this type. In the spirit of the late eighteenth century, the old joke became much more pointed and audacious than before—“outrageously cheeky,” in Heartz’s words.22 And yet, with both master and servant now portrayed as rounded and ultimately likeable human beings rather than caricatures, the ostensible antagonists are ultimately united in “enlightened” sympathy.

Thus, contrary to an opinion that is still voiced (though more rarely than it used to be), Beaumarchais’s Figaro plays were in no way “revolutionary.” The playwright was himself an intimate of the French royal family. In his plays, the aristocratic social order is upheld in the end—as, indeed, in comedies (which have to achieve good “closure”) it had to be. It could even be argued that the plays strengthened the existing social order by humanizing it. Hence Joseph II’s enthusiasm for them, which went—far beyond tolerance—all the way to active promotion.

In the play Mozart and Da Ponte adapted for music as Le nozze di Figaro, the valet Figaro (formerly a barber), together with his bride Susanna (the mezzo carattere role), acting on behalf of the Countess Almaviva (the seria role), outwits and humiliates the Count, who had wished to deceive his wife with Susanna according to “the old droit du seigneur” (not really a traditional right but Beaumarchais’s own contrivance), which supposedly guaranteed noblemen sexual access to any virgin in their household. All three—Figaro, Susanna, and the Countess—are vindicated at the Count’s expense. But the Count, in his discomfiture and heartfelt apology (a moment made unforgettable by Mozart’s music), is rendered human, and redeemed. On the way to that denouement there is a wealth of hilarious by-play with some memorable minor characters, including an adolescent page boy (played by a soprano en travesti, “in trousers”) who desires the Countess, and an elderly pair of stock buffo types (a ludicrous doctor and his housekeeper) who turn out to be Figaro’s parents.

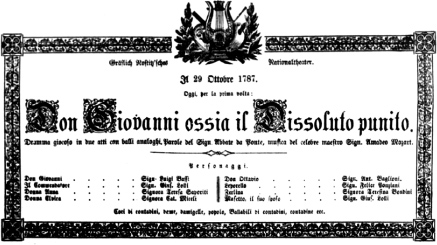

Mozart and Da Ponte had such a success with this play that their names are now inseparably linked in the history of opera, like Lully-and-Quinault or Gluck-andCalzabigi, to mention only teams who have figured previously in these chapters. The triumph led to two more collaborations. Don Giovanni followed almost immediately. It was a retelling of an old story, long a staple of popular legend and improvised theatrical farce, about the fabled Spanish seducer Don Juan, his exploits, and his downfall. Its first performance took place on 29 October 1787 in Prague, the capital of the Austrian province of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), where Le nozze di Figaro had been especially well received; it played Vienna the next year. Its success was only gradual, but by thetimehecametowritehismemoirs, DaPonte(whodiedanAmericancitizeninNew York, where from 1807 he worked as a teacher of Italian literature, eventually at Columbia University) could boast that it was recognized as “the best opera in the world.”23

Their third opera, produced at the Burgtheater on 26 January 1790 (a day before Mozart’s thirty-fourth birthday), was the cynical but fascinating Cosí fan tutte, ossia La scuola degli amanti (“Women all act the same; or, The school for lovers”), which had only five performances before all the theaters in Austria had to close following the death of Joseph II. It would be Mozart’s last opera buffa. The plot concerns a wager between a jaded “old philosopher” and two young officers. The old man bets that, having disguised themselves, each officer could woo and win the other’s betrothed. Their easy success, much to their own and their lovers’ consternation, has made the opera controversial throughout its history.

Many textual substitutions and alternative titles have seen duty in an attempt to soften the brazenly misogynistic message of the original. That message, preaching disillusion and distrust, is perhaps larger (and more dangerous) than its immediate context can contain. Its ostensible misogyny can be seen as part of a broad exposure of the “down side” of Enlightenment—a warning that reason is not a comforter and that perhaps it is best not to challenge every illusion. Some, basing their view on the assumption—the Romantic assumption, as we will learn to identify it—that the music of an opera is “truer” than the words, have professed to read a consoling message in Mozart’s gorgeously lyrical score. Others have claimed that, on the contrary, Mozart and Da Ponte have by that very gorgeousness in effect exposed the falsity of artistic conceits and, it follows, unmasked beauty’s amorality.

The tensions within it—at all levels, whether of plot, dramaturgy, musical content, or implication—between the seductions of beauty and cruel reality are so central and so deeply embedded as to make Cosí fan tutte, in its teasing ambiguity, perhaps the most “philosophical” of operas and in that sense the emblematic art work of the Enlightenment.

In his last pair of operas, both first performed in September 1791 less than three months before his death, Mozart reverted to the two genres in which he had excelled before his legendary collaboration with Da Ponte. Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) is a singspiel to a text by the singing actor and impresario Emanuel Schikaneder, who commissioned it for his own Theater auf der Wieden, a popular playhouse in Vienna. Behind its at times folksy manner and its riotously colorful and mysterious goings-on, it too is a profoundly emblematic work of the Enlightenment, for it is a thinly veiled allegory of Freemasonry.

A secret fraternal organization of which both Mozart and Schikaneder were members (along with Voltaire, Haydn, and the poets Goethe and Schiller), the Order of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons purportedly traced its lineage back to the medieval stonecutters’ guilds (and thence, in legend, to ancient Egypt, the land of the pyramids), but became a widespread international association in the eighteenth century and an important vehicle for the spread of Enlightened doctrines such as political liberalism and religious tolerance. Persecuted by organs of traditional authority, including the Catholic Church and the autocratic monarchies of Europe, the Masons had elaborate rites of initiation and secret signals (the famous handshake, for instance) by which members could recognize one another.

The plot of The Magic Flute concerns the efforts of Tamino, a Javanese prince, and Pamina, his beloved, to gain admission to the temple of Isis (the Earth- or Mothergoddess of ancient Egypt), presided over by Sarastro, the Priest of Light. Tamino is accompanied by a sidekick, the birdcatcher Papageno (played by Schikaneder himself in the original production; see Fig. 9-9), who in his cowardice and ignorance cannot gain admittance to the mysteries of the temple but is rewarded for his simplehearted goodness with an equally appealing wife. The chief opposition comes from Pamina’s mother, the Queen of the Night, and from Monostatos, the blackamoor who guards the temple (a clear throwback to Osmin in Die Entführung). The allegory proclaims Enlightened belief in equality of class (as represented by Tamino and Papageno) and sex (as represented by Tamino and Pamina) within reason’s domain. Even Monostatos’s humanity is recognized, betokening a belief in the equality of races. On seeing him, Papageno (who first sounds the opera’s essential theme when he responds to Prince Tamino’s question as to his identity by saying “A man, like you”) reflects, after an initial fright, that if there can be black birds, why not black men?

FIG. 9-8 Sarastro arrives on his chariot in act I of Mozart's Die Zauberfl"ote. Engraving published in an illustrated monthly to herald the first performance of the opera in Brünn (now Brno, Czech Republic)in 1793.

FIG. 9-9 Emanuel Schikanederin the role of Papageno in the first production of Die Zauberflöte (Theater aufder wieden, Vieden, 1791).

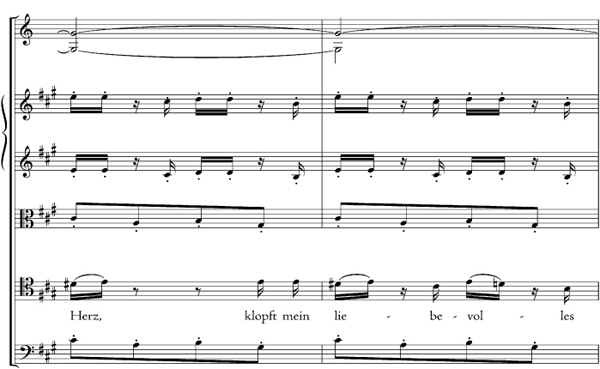

The range of styles encompassed by the music in The Magic Flute is enormous—wider than Mozart had ever before attempted. At one extreme is the folk-song idiom of Papageno, “Mr. Natural.” At the other are the musical manifestations of the two opposing supernatural beings—the forces, respectively, of darkness (The Queen of the Night) and light (Sarastro)—both represented by opera seria idioms, altogether outlandish in a singspiel. In act II, the Queen, seeing her efforts to thwart the noble pair coming to nought, gets to sing the rage aria to end all rage arias (Ex. 9-7a). Its repeated ascents to high F in altissimo are a legendary test for coloratura sopranos to this day. (That pitch had actually been exceeded, incidentally, in a coloratura aria—or rather, a spoof of coloratura arias—that Mozart tossed off early in 1786 as the centerpiece of a little farce called Der Schauspieldirektor or “The Impresario,” sung at its first performance by his sister-in-law Aloysia).

Sarastro, in the scene that immediately follows, expresses the opera’s humanistic creed in the purest, most exalted sacerdotal manner (Ex 9-7b). George Bernard Shaw, the famous British playwright, worked in his youth as a professional music critic. Perhaps his most famous observation in that capacity pertained to this very aria of Sarastro’s, which he called the only music ever composed by mortal man that would not sound out of place in the mouth of God.24 That is as good a testimony as any to the hold Mozart has had over posterity, but it is also worth quoting to reemphasize the point that such sublime music was composed for use in a singspiel, then thought (because it was sung in the German vernacular) to be the lowliest of all operatic genres. That was in itself a token of Enlightened attitudes. In such company, the lyrical idiom of the lovers Tamino and Pamina occupies the middle ground, the roles (so to speak) of mezzo carattere.

Mozart’s last stage work, an opera seria called La clemenza di Tito (“The clemency of Titus”), was composed to one of Metastasio’s most frequently set librettos, one that had been first set to music almost sixty years before by Antonio Caldara, then Vice-Kapellmeister to the Austrian court. Its revival was commissioned, symbolically as it might seem, to celebrate the accession to the Austrian throne of Joseph II’s younger brother, the Emperor Leopold II, who would rule for only two years—just enough time to undo all of his Enlightened predecessor’s reforms. Just so, it could seem as though Mozart’s reversion to a stiffly conventional aristocratic drama of sacrifice “undid” the modern realistic comedies that had preceded them—though of course no one had any premonition that this was to be his last opera.

FIG. 9-10 Pamina, Tamino, and Papageno in scene from act II of Die Zauberflote (Brunn, 1793).

EX. 9-7A W. A. Mozart, Magic Flute, “Der Hölle Rache” (The Queen of the Night), mm. 21–47

EX. 9-7B W. A. Mozart, Magic Flute, “In diesen heil’gen Hallen” (Sarastro), mm. 16–26

It has been claimed that Mozart accepted the commission with reluctance; but while his letters complain of some fatigue (and although he had to work in haste, farming out the recitatives to a pupil, Franz Xaver Süssmayr), there is no evidence that he felt the century-old genre of opera seria to be an unwelcome constraint. In any case, his setting of La Clemenza was fated to be the last masterpiece of that venerable genre, which barely survived the eighteenth century.

For a closer look at the team of Mozart and Da Ponte in action, we can focus in on what the librettist proudly called “the best opera in the world.” Many have endorsed Da Ponte’s seemingly bumptious claim on behalf of Don Giovanni. For two centuries this opera has exerted a virtually matchless fascination on generations of listeners and commentators—the latter including distinguished authors, philosophers, and even later musicians, who “commented” in music.

FIG. 9-11 Poster announcing the first performance of Mozart's Don Giovanni (Prague, 1787).

For E. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), a German writer (and dilettante composer) famous for his romantic tales, it was the “opera of operas,” altogether transcending its paltry ribald plot—about “a debauchee,” as Hoffmann put it, “who likes wine and women to excess and who cheerfully invites to his rowdy table the stone statue representing the old man whom he struck down in self-defense”—and becoming, through its music, the very embodiment of every noble heart’s “insatiable, burning desire” to exceed “the common features of life” and “attain on earth that which dwells in our breast as a heavenly promise only, that very longing for the infinite which links us directly to the world above.”25 There could be no better evidence of the way in which Mozart’s music in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

music reflected to a sensitive listener an image of his own idealized humanity, however at variance with the composer’s.