Chapter 15

Honey, I Love You

IN THIS CHAPTER

Learning about honey’s illustrious history

Learning about honey’s illustrious history

Understanding the difference between styles and varietals

Understanding the difference between styles and varietals

Using honey for health

Using honey for health

Appreciating the culinary side of honey

Appreciating the culinary side of honey

Judging honey for perfection

Judging honey for perfection

Special thanks to C. Marina Marchese for her work in preparing this chapter. Marina is co-author (with Kim Flottum) of The Honey Connoisseur and is founder of the American Honey Tasting Society.

Honey has earned its place as a sweetener of choice. You can hardly visit a farmers’ market or scroll through social networking sites without finding some reference to this remarkable product of the honey bee. Honey is used in beauty care, sought for its nutritional benefits, revered for its medicinal properties, valued as an ingredient for culinary applications, and expertly paired with foods by top chefs around the world. Honey’s uses are fantastically diverse. It’s not just for biscuits and tea anymore!

Appreciating the History of Honey

Man has used honey for thousands of years — certainly as a sweetener, but more often as a medicine to treat a variety of ailments. It has an illustrious history finding its way into folklore, religion, and every culture around the world. In ancient times, honey was considered a luxury enjoyed by the privileged and royals, as well as a valid form of currency to pay taxes.

The Cuevas de la Araña (Spider Caves) of Valencia, Spain, are a popular tourist destination. These caves were inhabitated by prehistoric people who painted images on the stone walls of activities that were a critical part of their everyday life, such as goat hunting, and lo and behold, honey harvesting. One of the paintings depicts two individuals climbing up vines and collecting honey from a wild beehive. Immortalized on the rock wall between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago, it is widely regarded as the earliest recorded depiction of honey gathering. See Chapter 1 for an image of this cave drawing.

Ancient Egyptians were the first known nomadic beekeepers to migrate their beehives on boats up and down the Nile in order to follow the seasonal bloom specifically for pollination (see Figure 15-1). Beeswax paintings on the pyramid walls depicted beekeepers smoking their hives and removing honey. This tells us that the Egyptians understood the seasonality of beekeeping and the symbiotic relationship between honey bees and pollination.

Illustration by Howland Blackiston, based on original tomb painting

FIGURE 15-1: Egyptians harvested honey over 3,000 years ago.

In 2007 a remarkable find was made during an archaeological dig in the Beth Shean Valley of Israel. An entire apiary was uncovered from Biblical times, containing more than 30 mostly intact clay hives, some still containing very, very old bee carcasses. These man-made hives date from the 10th to early 9th centuries BCE, making them the oldest man-made beehives in the world. It is believed that as much as a half-ton of honey was harvested each year from this site.

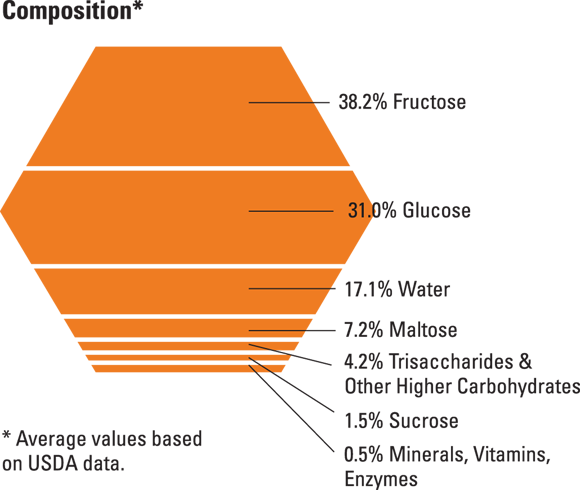

Understanding the Composition of Honey

Honey is the sweet result of the bees magically transforming the nectar they gather from flowers. Honey is about 80 percent fructose and glucose, and between 17 and 18 percent water. Maintaining a balance between sugar and water is critical to the quality of honey. Excess water, for example from poor storage, can trigger yeast fermentation, and the honey will begin to spoil. The bees nail this balance instinctually, but we can upset the delicate ration by improper harvesting and storing of honey.

More than 20 other sugars can be found in honey, depending upon the original nectar source. There are also proteins in the form of enzymes, amino acids, minerals, trace elements, and waxes. The most important enzyme is invertase — which is an enzyme added by the worker bees. This is responsible for converting the nectar sugar sucrose into the main sugars found in honey: fructose and glucose. It is also instrumental in the ripening of the nectar into honey.

With an average pH of 3.9, honey is relatively acidic, but its sweetness hides the acidity.

The antibacterial qualities associated with honey come from hydrogen peroxide, which is a by-product of another enzyme (glucose oxidase) introduced by the bees. See “Healing with Honey” later in this chapter.

The plants themselves and the soil they grow in contribute to the minerals and trace elements found in honey. See Figure 15-2 for a typical breakdown of honey content.

Honey owes its delicate aromas and flavors to the various volatile substances (similar to essential oils) that originate from the flower. As age and excess heat decompose the fructose, hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) naturally found in all honeys increases, thus lowering the quality. Each of these components that make up honey is extremely fragile, and overheating honey or improper or long-term storage can compromise not only the healthful benefits but also honey flavors as well as darken it (see “Raw versus regular honey” later in this chapter).

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 15-2: This chart illustrates the typical content of honey (based on data from the USDA).

Healing with Honey

Honey is nice on toast. But did you know it will also relieve a multitude of health issues — from taming a cough and alleviating allergies to healing cuts or burns? Because of its low pH and hygroscopic properties, most bacteria cannot survive in honey. The pollen in the honey is a pure source of plant-based protein and contains various minerals, enzymes, and B vitamins, which impart immune-boosting properties. Good stuff.

If you are sensitive to sugars, honey is the best sweetener of choice because the fructose and glucose sugars are pre-digested by the bees and aid in maintaining blood-sugar levels. The first gives you a natural burst of energy, and the second sustains your blood levels so you won’t get the sugar blues as you might with processed white sugar. Overall, honey is a wise choice — it is wholesome, flavorful, and the only truly raw sweetener found in nature.

Honey and diabetes

All kinds of conflicting information can be found on the Internet about whether honey is or is not okay for those with diabetes. My advice is that if you are on a diabetes eating plan, you should check with your doctor for the definitive answer. In the meantime, the following information from the Mayo Clinic’s website is helpful:

Generally, there’s no advantage to substituting honey for sugar in a diabetes eating plan. Both honey and sugar will affect your blood-sugar level. Honey is sweeter than granulated sugar, so you might use a smaller amount of honey for sugar in some recipes. But honey actually has slightly more carbohydrates and more calories per teaspoon than does granulated sugar — so any calories and carbohydrates you save will be minimal. If you prefer the taste of honey, go ahead and use it — but only in moderation. Be sure to count the carbohydrates in honey as part of your diabetes eating plan.

Honey’s nutritional value

One tablespoon of honey (21 grams) provides 64 calories. Honey tastes sweeter to most people than sugar, largely due to the fact that fructose tastes sweeter, and as a result, most people likely use less honey than they would sugar.

Honey is also a rich source of carbohydrates, providing 17 grams per tablespoon, which makes it ideal for your working muscles because carbohydrates are the primary fuel the body uses for energy. Carbohydrates are necessary to help maintain muscle glycogen, also known as stored carbohydrates, which is the most important fuel source for athletes to help them keep going.

Honey and children

Choosing Extracted, Comb, Chunk, or Whipped Honey

What style of honey do you plan to harvest? You have several different options (see Figure 15-3). Each affects what kind of honey harvesting equipment you purchase, because specific types of honey can be collected only by using specific tools and honey-harvesting equipment. If you have more than one hive, you can designate each hive to produce a different style of honey. Now that sounds like fun!

Courtesy of Howland Blackiston

FIGURE 15-3: The four basic types of honey you can produce (extracted, comb, chunk, and whipped).

Extracted honey

Extracted honey is quite simply liquid honey. It is by far the most popular style of honey consumed in the United States. Wax cappings are sliced off the honeycomb, and the honey is removed from the cells in a honey extractor by centrifugal force (spun from the cells). Hence the term extracted honey.

The liquid honey spun out of the comb cells is strained and then poured into containers. The beekeeper needs an uncapping knife or fork, an extractor (spinner), and some kind of sieve to strain out the bits of wax and the occasional sticky bee. Chapter 17 has instructions on how to harvest extracted honey.

Comb honey

Comb honey is honey just as the bees made it still in the original container, the beeswax comb. In many countries, honey in the comb is considered the only truly authentic honey untouched by humans while retaining all the pollen, propolis, and associated health benefits. When you uncap those tiny beeswax cells, the honey inside is now exposed to the air for the very first time since the bees stored it.

Encouraging bees to make this kind of honey is a bit tricky. You need a strong nectar flow to get the bees to make comb honey. Watch for many warm, sunny days and just the right amount of rain to produce a bounty of flowering plants. But harvesting comb honey is less time-consuming than harvesting extracted honey. You simply slice the honeycomb out of the frame and package it. You eat the whole thing: the wax and honey. Pure beeswax is edible! A number of nifty products facilitate the production of comb honey (but more on that in Chapter 16).

Chunk honey

Chunk honey refers to placing pieces of honeycomb in a wide-mouthed jar and then filling around the honeycomb and topping the jar off with extracted liquid honey. Packing chunks of honeycomb into a glass jar is a stunning sight, creating a stained-glass effect when a light-colored honey is used. By offering two styles of honey in a single jar (comb and extracted), you get the best of two worlds.

Whipped honey

Also called creamed honey, crystallized honey, spun honey, churned honey, candied honey, or set honey. Whipped honey is a semisolid state of honey that’s very popular in Europe and Canada. In time, all honey naturally forms granules or crystals. But by controlling the crystallization process, you can produce very fine crystals with a velvety-smooth, spreadable texture.

Beekeepers can force their honey to crystallize by blending nine parts of extracted liquid honey with one part of finely granulated (crystallized) honey. It’s stored in a cool place and stirred every few days. The resulting consistency of the whipped honey is thick, ultra-smooth, and can be spread on toast like butter. There are also tools for rapidly whipping the honey as it crystallizes to make a decadently creamy batch. Making it this way takes a fair amount of work, but it’s worth it!

Most honeys eventually crystallize naturally. Some honeys may take a year to crystallize, like tupelo, black sage, acacia, and honeydew honey. When honey crystallizes, the texture can be smooth as silk or like coarse sand. This natural occurrence begins when the glucose spontaneously loses water and forms a solid crystal around pieces of pollen or dust particles that have settled at the bottom of the jar. As more crystals grow, the honey slowly turns solid.

Honeydew honey

There is another style of honey, and it does not originate directly from floral nectar. It’s known as honeydew honey. It’s commonly found in the EU and is revered in religious text under the name manna. When various other insects (typically aphids) gather nectar from flowers, leaves, and tree buds, honey bees will gather these insects’ secretions. The resulting honeydew honey made by bees is rich in minerals and enzymes. It is generally dark in color and prized for its many health and healing benefits. It’s sometimes difficult to tell the difference between traditional honey and honeydew simply by tasting it. Often honeydew sold in shops is labeled as oak, forest, or pine honey. It is slow to crystallize because there is very little pollen in honeydew.

Taking the Terror out of Terroir

The floral sources, soil, and climate ultimately determine how your honey will look, smell, and taste. Winemakers call these ever-changing environmental factors terroir.

The sensory characteristics of any honey — color, aroma, and flavor profile — are reflective of a specific flower from a specific region. Location, location, location! This unexpected diversity of each honey harvest makes tasting honey a never-ending culinary experience. Opportunities to visit honey producers and taste the honey of that region and season can be an eye-opening and delicious adventure.

The flavor of the honey your bees make is likely more up to the flowers in your area, the climate, and the bees than you. You certainly can’t tell the bees which flowers to visit. See Chapter 3 for a discussion of where to locate your hive when you want to encourage a particular flavor of honey.

Customizing your honey

Some beekeepers harvest honey from a single floral source, resulting in varietals or uni-floral honeys. Granted, several acres of that single floral source are needed, and the bees must be prepared to work the bloom at the very moment it is producing nectar. But what we get from this focused approach are honeys that have distinctive flavor profiles that resemble the flower and region from which the honey is harvested. Simply put, varietal honeys are poetry in nature (see Figure 15-4).

Courtesy of Marina Marchese

FIGURE 15-4: Some of the honey varietals from around the world that are in honey connoisseur Marina Marchese’s collection.

Honey from around the world

Here is a short list of some of the most popular varietal honeys harvested by beekeepers around the world. I include some notes on color, aroma, and flavor as well as my favorite food pairings for these various honeys.

Acacia

Region: Europe, Asia, Africa

Color: Transparent pale-yellow color

Aroma: Delicate

Flavor: Sweet notes of apricot and pineapples

Pairings: Salty cheeses, fresh grapefruit, or grilled salmon

Note: Acacia blooms in early spring.

Alfalfa

Region: Midwestern U.S. and worldwide

Color: Light amber, straw

Aroma: Dry hay, sour, pungent

Flavor: Barnyard, spicy, yeasty

Pairings: Cornbread, grilled lamb chops

Notes: Grown for hay to feed livestock, alfalfa apparently doesn’t want honey bees to steal its nectar. So it’s evolved the ability to “spank” the bee when she tries to enter the nectary. This disciplinary action deters the bees and prompts them to chew holes into the side of the flowers to rob the flower nectar.

Avocado

Region: Mexico, Peru, California, Texas, Florida, and Hawaii

Color: Dark amber

Aroma: Medium intense, smoky, brown sugar

Flavor: Fruity, burnt sugar, nutty

Pairings: Barbecue

Blueberry Blossom

Region: Maine, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Oregon

Color: Light to medium amber

Aroma: Warm milk, musty fruit

Flavor: Dark fruit, notes of blueberries

Pairings: Soft cheeses, ice cream, or pound cakes

Notes: Blueberry pollination is the second-largest annual pollination event in the United States. (Almond pollination is the largest.)

Buckwheat

Region: The largest producers are Russia and China, although grown in several states, including Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, South Dakota, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

Color: Dark amber

Aroma: Woody, musty, malty

Flavor: Chocolate, coffee, dark beer

Pairings: Barbecue, dark cherries

Chestnut

Region: Italy, Spain, France, Eastern Europe, and Turkey

Color: Dark amber

Aroma: Woody, pungent, intense

Flavor: Bitter, vegetal, nutty

Pairings: Poached pears, walnuts, or panna cotta

Notes: Blooms appear in June until July, yet the nut matures later in the season. Festivals are common to celebrate the dark earthy and sometimes bitter chestnut honey harvest.

Clover

Region: Heartland USA

Color: Light amber, straw

Aroma: Green grass, beeswax, spicy

Flavor: Cinnamon, grassy, dry hay

Pairings: Salad dressings, rice pudding, or honey butter

Notes: Clover honey can be found in just about every grocer and kitchen because it’s the premier floral source for honey bees in the United States.

Fireweed

Region: Pacific Northwest and Alaska

Color: Transparent; crystallizes slowly

Aroma: Delicate, dried fruit, brown sugar

Flavor: Pears, warm caramel, and pineapples

Pairings: Fried chicken, carrots, gingersnaps

Notes: Fireweed is known as a colonizer plant because it’s the first plant to grow after a wildfire. Without other plants nearby, it is easy to harvest pure fireweed honey. Fireweed blooms in June and lasts until September.

Lavender

Region: The Provence area of France, individual lavender farms in U.S.

Color: Light straw

Aroma: Delicate, floral notes

Flavor: Almond, vanilla

Pairings: Nougats

Notes: The vast fields of lavender blanket the south of France, where everything is inspired by the scent of lavender.

Linden or Basswood

Region: United States, United Kingdom, and Europe

Color: Medium golden amber

Aroma: Butterscotch, fruity, herbal

Flavor: Green fruit, butterscotch with a signature menthol finish

Pairings: Green melon and fresh mint, seared scallops, and cilantro

Notes: Many city streets are lined with linden trees offering city beekeepers a delicious harvest. Basswood trees are good nectar producers known as lime tree honey.

Ling Heather

Region: The moors of Ireland and Scotland

Color: Dark amber, red tint

Aroma: Intense, smoky, woody

Flavor: Toffee, bitter coffee, plum

Pairings: Steel-cut oats, cheddar cheese, or spice cake

Notes: Ling honey is so thick that it must be hand-pressed from the honeycomb. When inside the jar, Ling honey becomes thick as jam until stirred to become liquid again. This thick-to-thin property is called thixotrophy. Only a few rare honeys exhibit this quality.

Locust

Region: East central United States, Europe, China

Color: Light-colored honey that has a green hue

Aroma: Delicate, vanilla

Flavor: Butterscotch, warm vanilla, and dried fruit flavors

Pairings: Salty cheeses

Notes: Blooms in early spring, showing off its highly aromatic clusters of white flowers. This honey is difficult to obtain because of its early bloom time. Conditions must be perfect.

Manuka

Region: New Zealand and southeast Australia

Color: Beige; granulates quickly

Aroma: Musty, camphor, earthy

Flavor: Earthy, damp, and evergreen — like an Alpine forest

Pairings: Used internally for ulcers and health reasons

Notes: Honey is world renowned for its healing properties (especially regarding ulcers and intestinal problems). Manuka is the name for the tea tree, which grows in New Zealand and southeast Australia. Manuka is mostly taken as a medicine in the United States. It is thixotropic and has a very high viscosity. Warning: Because of the very high premium paid for manuka, much of the commercially available product labeled as manuka is not what it claims to be. New Zealand produces 1,700 tons of manuka honey annually (nearly all the world’s production comes from New Zealand). But 10,000 tons or more of honey labeled as “manuka” is being sold annually. That doesn’t quite add up!

Mesquite

Region: Texas, Louisiana, Arizona, New Mexico, and along the Mexican border

Color: Medium amber

Aroma: Warm brown sugar

Flavor: Smoky, woody

Pairings: Barbecue, pecan pie

Orange Blossom

Region: Tropical regions, predominately in Southern California and Florida

Color: Burnt orange

Aroma: Floral notes of jasmine and honeysuckle

Flavor: Orange, perfumy flowers

Pairings: Cranberry bread, glazed chicken, or red cabbage slaw

Notes: The flavor of orange honey harvested in the West has a warmer flavor reminiscent of the sandy desert.

Sage

Region: Native to the United States and can be found along the dry, rocky coastline and hills of California

Color: Water white

Aroma: Delicate, sweet

Flavor: Delicate, sweet notes of green and camphor

Pairings: Roasted potatoes, lamb, or watermelon and feta

Notes: A distinct taste of the warm western desert

Sidr

Region: Hadramaut in the southwestern Arabian peninsula

Color: Dark amber

Aroma: Cooked fruit

Flavor: Rich, dates, molasses, green fruit

Pairings: Traditional warm breads, pastries

Notes: Considered the finest and most expensive honey in the world (expect to pay around $300/pound). It contains the highest amount of antioxidants, minerals, and vitamins. Beekeepers laboriously carry their hives up the mountains twice each year. It’s the Rolls Royce of honey!

Sourwood

Region: Called “mountain honey” because the tree is located throughout the Blue Ridge mountain region of Southeastern U.S.

Color: Water white, gray tint

Aroma: Warm, spicy

Flavor: Nutmeg, cloves ending with a sour note

Pairings: Figs, blue cheese, or warm cider

Notes: A highly sought-after honey

Star Thistle

Region: Found across the entire United States

Color: Yellow amber with a green tint

Aroma: Cooked tropical fruits, wet grass

Flavor: Green bananas, anise, and spicy cinnamon

Pairings: Manchego cheese, vinaigrette, herbal teas

Notes: Attractive plant for honey bees; often called spotted knapweed

Thyme

Region: Highly praised in Greece; some produced in New York’s Catskill region

Color: Very light amber

Aroma: Pungent

Flavor: Fruit, resin, camphor, herbs

Pairings: Pastries and sweet cakes

Notes: It is also known as Hymettus honey, named after the mountain range near Athens.

Tupelo

Region: Grows in the swamps of southern Georgia and northern Florida

Color: Light golden amber, it rarely crystallizes

Aroma: Spicy, buttery

Flavor: A delightful mix of earth, warm spice, and flowers

Pairings: Buttermilk biscuits, honey-mustard salmon

Notes: Often referred to as the champagne of honey, you’ll pay champagne prices for this rare variety.

The Commercialization of Honey

On average, the United States consumes 450 million pounds of honey a year. And yet American beekeepers produce only around 149 million pounds a year. Hmm. Where does that honey come from to meet the demand? It comes from overseas. Countries like Argentina, China, Germany, Mexico, Brazil, Hungary, India, and Canada export millions of pounds of honey each year to satisfy America’s sweet tooth. Of course, as a beekeeper, you will have your own private stash.

Is it the real deal?

Unbeknownst to the average consumer, honey is one of the top five foods for adulteration and fraud. Unfortunately, to fill the huge demand, some commercial honey producers and importers do unscrupulous things like cutting honey by adding extraneous, improper, or inferior ingredients. They may add high fructose corn syrup or other sweeteners in order to extend their assets. Some remove the naturally present pollen in their honey by heating and ultra-filtering it. This makes it sparkling clear and less prone to crystallization (see the following section for the difference between raw and regular honey). Filtering also makes the source of the honey difficult to trace, because the pollen allows the honey to be tracked back to the floral source and the region where it was produced.

Raw versus regular honey

The main difference between regular and raw honey is that commercially produced honey (such as that found in supermarkets) is typically pasteurized and ultra-filtered. Pasteurization is the process where honey is heated at high temperatures to kill any yeast that may be present that may cause botulism. It’s also done to keep the honey from crystallizing, making it look more attractive to consumers. In addition, the ultra-filtering process removes pollen (and makes the product sparkling clear). But all this heating and filtering destroys most of the enzymes and vitamins while removing the beneficial pollen. It also evaporates the natural aromas and flavors. So commercially pasteurized honey doesn’t have as many health benefits or sensory pleasures as raw honey. Raw may not always look attractive in the jar, especially while it is crystallizing, but raw honey smells and tastes miles better than its commercialized counterpart. It also means the wonderful health benefits are not compromised.

Organic or not?

You may have noted that some honey jars in stores are labeled as organic. It’s a great marketing idea (after all, organic products sell very well). But the claim of being organic is not necessarily an accurate representation. If you look carefully at such labels, you will likely find that the so-called “organic” honey is from outside the United States (where organic certification is not to the same strict standards as the USDA uses for certifying other organic food products). In fact, as of this writing, the USDA has not adopted any standards for certifying honey as organic. Therefore, no beekeepers in the USA can truthfully label or tell consumers that their honey is certified organic. Given that bees forage nectar and pollen from flowers that are 2 or more miles in any direction from the hive, there is no practical way to guarantee that absolutely all of the flowering plants in this huge area are not subjected to chemical treatments or are not genetically modified. For now, I suggest you take any organic claims with a grain of salt and stay clear of making such claims for your own honey.

Your own honey is the best

The commercialization of honey is one more reason why keeping honey bees and producing your own honey is the sweeter choice. You know how the product was produced, how you care for your bees, and from where the bees gathered their nectar. Alternatively, if you purchase honey from local farmers’ markets ask your local beekeeper about his bees and management practices. They’ll be happy to give you a taste before you buy a jar.

Appreciating the Culinary Side of Honey

When I first tasted fresh honey from the hive, I was immediately impressed with how delicate and subtle the flavor was. The single, uncomplicated fact that honey could simply be harvested and eaten without any other special preparations made the idea of keeping honey bees deliciously appealing to me. I like to tell people that tasting honey is like tasting wine, except you don’t have to spit. The tasting technique for honey is comparable to tasting wine, coffee, tea, or chocolate. You use all of your senses to evaluate honey in order to learn more about what is happening to your senses and in your mouth. You simply take note of each honey’s color, aroma, clarity, texture, taste, and (most important) flavor notes.

The nose knows

Humans experience thousands of flavors with our noses; however, we are only capable of experiencing four basic taste sensations on our tongues — sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. A fifth, called Umami, is a savoriness found in tomatoes, soy sauce, or mushrooms. Of our five senses, our sense of smell is approximately a thousand times more sensitive than our sense of taste; everything else is considered flavor. Try this exercise: Hold your nose closed as you put a spoonful of honey on your tongue. What do you taste? A sweet liquid but no real flavor? Now, unplug your nose and inhale; immediately you smell its flavor. When you open your nose, the molecules travel up your nose into your olfactory bulb, which is where you experience flavor.

Next, pour a few tablespoons of honey into a small glass jar, cup both hands around it to warm the honey, and with a spoon swirl it around the edges to move the molecules. Notice the honey’s color and texture. There are seven designated colors of honey — water white, extra white, white, extra light amber, light amber, amber, and dark amber. Now stick your nose inside the jar and take a deep smell. This is the best way to capture the honey’s aromas. Take a spoonful onto your tongue and let it melt; then inhale to experience the honey’s flavors. Can you identify the flavors? You can use words like floral, fruity, grassy, or woody. Figure 15-5 shows the seemingly unlimited range of aromas and tastes you can experience when you’re sampling honey. The more honey you taste, the more you will determine its multitude of flavors. Taste, aroma, and texture experienced together are the main components that impart flavor in your mouth.

Excerpted with permission from The Honey Connoisseur, by C. Marina Marchese and Kim Flottum. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2013.

FIGURE 15-5: Use this honey aroma and tasting wheel to pinpoint the unique flavors and characteristics of your honey and others.

Practice makes perfect

No one is born an expert taster; learning to recognize flavors comes from the practice of conscious tasting. The repetitive act of tasting different samples of honey side by side is where the discovery comes into play, and you quickly begin to recognize the differences and similarities between each honey. Whereas sugar and other sweeteners are simply sweet, honey can express floral, grassy, fruity, or woody flavor notes. Look for a wide range of flavors that are clearly identifiable. Take note on when the flavors appear while the honey is on your tongue — there’s a beginning, middle, and finish to each flavor.

Recognizing defects in honey

On occasion, you may come across a honey with undesirable flavors that are not considered positive attributes. These are called off-flavors, or defects. Some are easily recognized, and others require a bit of experience to identify. Common defects are fermentation from a high percentage of water present or improper storage; smoke or burnt flavors from old wax comb or too much smoke used at harvest; or metallic tastes from rusty equipment or storage in metal containers. There also can be chemical residues from colony treatments or dirty equipment and extracting techniques or improperly cleaned containers of honey. Any of these are offensive and unwelcome. If your honey tastes unusual, something could be wrong.

Pairing Honey with Food

There is never a wrong way to eat honey. It pairs perfectly with every food group, and sometimes it is best enjoyed simply off the spoon. You will find that some food pairings will quickly become your favorites. Honey served with cheese is a timeless classic. This favorite pairing can be traced back to a Roman gourmand named Marcus Gavius Apicius (first century AD).

Begin with foods that have flavors and textures you enjoy. Try fresh pears, figs, or walnuts with bread or crackers. Now choose a few varietal honeys or your own harvest, and drizzle over the pairing. Look for combinations that complement or contrast with the honey. Sometimes they blend in your mouth to create an entirely new tasting experience. When one overpowers the other or cancels out another flavor, you have a clash in your mouth. A creamy goat cheese complements a buttery and fruity honey. A rich, dark honey contrasts nicely with a stinky bleu cheese. Serve honey with bread and crackers and sides like fresh or dried fruits, nuts, and vegetables to add color and texture. The choices are endless, and you’ll have fun serving up your favorites at your next gathering.

For some outstanding recipes using honey, be sure to buzz over to Chapter 20.

Infusing Honey with Flavors

Honey will take on the flavors of any foods that you infuse into the jar. It’s a delicious experiment to add flavors like citrus zest, ginger, rosemary, cinnamon, or even rose petals to your honey to add an extra dimension. Be sure to wash and completely dry any food you infuse into your honey. The drying prevents added water from upsetting the delicate water and sugar percentage, which can cause the honey to ferment. Let your infusion sit at room temperature for two to three weeks — the longer it sits, the more flavorful your infused honey will become.

Judging Honey

Preparing honey for competition is an exciting step for beekeepers to demonstrate their attention to detail at the show bench. Honey judges are trained to scrutinize each entry for a perfect presentation of honey samples. Judges follow strict guidelines that are understood by the entrants. For example, air bubbles that create unsightly foam during extraction, debris, wax, lint from cheesecloth during straining, overly dark comb from old wax foundations, layered crystallization, fermentation, and even small holes in the wax cappings are just a few issues that can disqualify even the most delicious honey. Judges look at presentation and quality of each honey entry and take note of all these factors on score cards that serve to aid the beekeeper in understanding how and why the judges came to their final decision. Moisture is a significant factor in fermentation of samples and can be quickly determined by a hand-held refractometer (see Figure 15-6).

Surprisingly, identifying flavors is not as highly important to the judging process as a seamlessly prepared clean sample with a pleasing flavor. Look for honey competitions at your own bee club or at regional beekeeping conferences. You’ll also find international honey shows where you will see, not only honey but also some interesting beeswax crafts. The rules, regulations, and judging criteria vary from show to show, so be certain to research the judging criteria and a honey application for each specific contest.

Courtesy of Misco Refractometers

FIGURE 15-6: A refractometer is used to measure the water content of honey.

Honey Trivia

Here are some tidbits of “betcha-didn’t-know” information about honey that will make for some good banter at the dinner table:

- How many flowers must honey bees tap to make one pound of honey? Two million.

- How far does a hive of foraging bees fly to bring you one pound of honey? Over 55,000 miles.

- How many flowers does a honey bee visit during one nectar collection trip? 50 to 100.

- How much honey would it take to fuel a bee’s flight around the world? About one ounce.

- How long have bees been producing honey from flowering plants? 10 to 20 million years.

- What Scottish liqueur is made with honey? Drambuie.

- What is the U.S. per capita consumption of honey? On average, each person consumes about 1.3 pounds per year.

Interesting, huh? How about three more little-known honey facts:

- In olden days, a common practice was for newlyweds to drink mead (honey wine) for one month (one phase of the moon) to ensure the birth of a child. Thus the term honeymoon.

- One gallon of honey (3.79 liters) typically weighs 11 pounds, 13.2 ounces (5.36 kilograms).

- Honey found in the tombs of the Egyptian pharaohs was still edible when discovered centuries later. That’s an impressive shelf life!

Generally speaking, the darker the honey, the greater the minerals and antibacterial qualities.

Generally speaking, the darker the honey, the greater the minerals and antibacterial qualities. The Mayo Clinic advises that children should be at least 12 months before introducing honey into their diets. Spores of botulism are all around us and naturally find their way into all raw foods and may settle inside a honey jar. Mature digestive and immune systems can normally handle this type of bacteria; however, infants under 12 months of age should not consume raw honey. I urge that you seek advice from your own medical care provider.

The Mayo Clinic advises that children should be at least 12 months before introducing honey into their diets. Spores of botulism are all around us and naturally find their way into all raw foods and may settle inside a honey jar. Mature digestive and immune systems can normally handle this type of bacteria; however, infants under 12 months of age should not consume raw honey. I urge that you seek advice from your own medical care provider. Honey should never be refrigerated. Cooler temperatures accelerate the natural process of crystallization of honey.

Honey should never be refrigerated. Cooler temperatures accelerate the natural process of crystallization of honey.