Chapter One

THE FIFTH AND SIXTH CENTURIES

Reorganisation Among the Ruins

Two of the most informative categories of archaeological evidence are pot sherds and coins, and nothing shows more clearly the extent to which the economic system of the fourth century had changed by the middle of the fifth than that mass-produced vessels ceased to be made in the British Isles, and that there were not enough coins to sustain the circulation of an officially-recognised currency.

Coins had been used to pay the Roman army and to maintain the Empire's bureaucracy, to collect tax and to facilitate the exchange of goods; without them, no large-scale organisation could operate. Early fifth-century coins are found at various sites, but there were no new supplies to maintain a coin-using economy—although the extent to which coins were used in Britain even in the fourth century for marketing rather than for paying the army is not clear. In the same way, the army had created a substantial demand for pottery; without the troops, long-distance transport of pottery was not economic. It was probably also increasingly difficult to carry goods as roads and waterways became overgrown or silted up without the regular maintenance that a central authority could insist upon; consequently production centres could only hope to supply their own immediate hinterlands. Such restricted circulation was unable to justify the scale of production of earlier periods, so the industries came to an end, their workforces presumably merging into the general population. The coarse, hand-made pots of the fifth and sixth centuries, many tempered with farmyard dung, seem to owe nothing to the wheel-thrown products of the specialist late Roman industries.1

Within the span of what for some could have been a single life-time, the structure of the economy and society in those parts of the British Isles which had been under the governmental control of the Roman Empire greatly changed. The nature of the changes was not necessarily uniform: differences in soil types, ease of access to other regions, possession of natural resources, the weight of inherited traditions and external pressures would all have been factors creating wide diversity. Some contrasts between the fourth and fifth centuries can be exaggerated by modern values; that stone buildings were widely in use in the former may hinder proper appreciation of the quality of timber buildings that can be inferred from post-holes and beam-slots in the latter. It may, however, have been a contrast in standards of which contemporaries were themselves well aware. Timber buildings erected within the walled area of Wroxeter, Shropshire, were solid and substantial, but were they regarded as highly as the partly still-standing stone baths alongside, or were they seen as a feeble attempt to keep up appearances?2 Those who had enjoyed the trappings of power, wealth and luxury would not willingly have given up all pretence of them or have lost hope that revival might occur. Even those who had not shared in them could still aspire to what they had offered.

Few agricultural workers or artisans need have felt much sense of loss. For producers, as opposed to entrepreneurs and merchants dealing in finished articles, the breakdown of the market and taxation systems, and of the social structure which went with them, probably meant some relaxation of ties that forced dependence. A family might have the opportunity to take up land, perhaps keeping up a craft skill as a limited part-time activity. Those who worked the land could expect to benefit from the weakening of the state's support for land owners in their exploitation of the production capacity of their slaves and tenants, just as state-imposed tax burdens were reduced, removing some of the pressures on land owners in areas where they managed to remain in possession of some vestiges of their former rights. If there were slaves, their legal servility might be relaxed, equating them with other producers whose role was to support their own families and to create some surplus for their lords.3

One of the problems in this period is to assess the extent to which a landowning class continued to exist, a problem exacerbated by the difficulty of reconstructing the complete settlement pattern in any area, and of recognising any hierarchy both within individual settlements and within the overall pattern. In the south and east, excavations of rural domestic sites have not produced evidence that much social differentiation was physically expressed in the fifth and sixth centuries, but this may be because settlement sites are still far from common, and the most fully excavated and published site, West Stow in Suffolk, may not be typical. But there was at any rate no house-complex there which, from the size of its buildings or from the quality of the contents of the rubbish deposits closest to it, can be claimed as that of a ‘headman’ surrounded by his dependents.4

West Stow was practising a mixed agricultural economy. There was evidence for a range of cereals: wheat, barley, rye and oats. Because pollen samples could not be obtained from the site, evidence of the use of peas and beans is all but absent, but animal and bird bones survived well, and are further evidence of mixed farming: cattle, sheep, pigs, a few goats, and domestic fowl and geese.5 A small number of horses were kept. The bones of some red and roe deer, and of wild birds, were so few that they show plainly that domestic stock was what mattered; anything hunted was an incidental addition to the basic diet. Bones from all parts of the animals were found, so carcases were not brought to the site already partly jointed, an indication, if any were needed, that they had been locally produced. The quality of the stock is a reflection of agricultural standards; the animals were in general not noticeably smaller or scrawnier than animals from earlier sites. Although changes in the economic pattern destroyed the potteries and took money out of circulation, they did not also cause a collapse of the rural base. Meadowland must have been maintained, with a hay crop that could sustain cattle through the winter, since about half the animals were allowed to live until fully grown. Many cows were five years old or more when slaughtered, an indication that they were kept largely for their milk. The pigs on the other hand were nearly all slaughtered while still young, which is good husbandry: only a few breeding sows were allowed to continue to live and feed, since the only point of a pig is its pork. A site with the bones of old pigs is often one with woodland near it, where the swine could range freely and were difficult to recapture. If there were no great woods close to West Stow, however, it was still possible for its inhabitants to acquire timber plentifully, as they used it liberally in their buildings. They may therefore have had gathering rights in woodland quite distant from their homes.

The sheep at West Stow were being killed at an earlier average age than on most later sites, which implies that their main function was to supply meat and milk rather than wool. This suggests that wool was not being produced in quantity for commercial reasons, as it was to be in the rest of the Middle Ages. Weaving was certainly taking place, as clay loom-weights and bone tools attest the use of vertical looms (5, 4) —as indeed they do on most residential sites before about 1100. This was probably basic domestic production, with each household supplying its own needs; certainly the evidence for weaving was not concentrated in particular zones of the site, which would have suggested specialised craft workshop areas. There may have been some production of a surplus, but the sheep bones do not indicate pressure to concentrate upon wool at the expense of other crops.

Other evidence of craft activity that a self-reliant settlement site might produce includes pottery. Over 50,000 sherds were recovered from West Stow, a huge quantity in comparison to most contemporary sites, even though no more than two or three farms may have been operating there at any one time. All the fifth- and sixth-century pottery was made in the locality, since none of the fabrics contained minerals other than what can be found within a ten-mile radius. None was made on a wheel, none was glazed, and all could have been fired in bonfires which would usually leave no trace in the ground. No structural evidence of pot-making can therefore be expected. There was, however, a ‘reserve’ of raw clay found on the site, although this could have been intended for use in wall-building. There were also, near the clay, five antler tools cut so that their ends could be used as stamps, possibly on leather, but more probably on pots. The sheer quantity of pottery found at West Stow, and the care that went into the burnishing and other decoration of at least some of it, suggest a high demand, and perhaps therefore production by people for whom it was a special activity, albeit part-time or seasonal, rather than production by each household just for its own immediate needs. Presumably therefore the pot-makers were turning out a surplus which they could exchange with their neighbours, perhaps in other settlements.

The direct evidence of other crafts is no less scanty. Fragments of worked bone and antler can be assumed to be the waste discarded during the production of some of the tools, such as the five antler dies, and combs. Again, these could all have been produced on the site, but both the quantities and the decoration suggest that those making them had particular skills. Similarly, iron could have been smelted, in small bowl hearths difficult to locate archaeologically, as superficial ore deposits probably existed locally; but only someone with a blacksmith's skills could have produced knives, reaping-hooks and other tools and weapons, and a little slag indicates that at least some smithing did take place. Some raw materials, such as glass, could have been scavenged from earlier, abandoned sites, but the iron objects are too numerous all to have been made from such scrap, nor were any distinctively pre-fifth-century iron objects found awaiting recycling at West Stow, whereas earlier glass rings, and copper-alloy coins, brooches, spoons and other miscellanea were quite common. The glass beads found there may well have been made by melting down such detritus, as could the copper-alloy and silver objects, although no crucibles or moulds were found. Analyses at other sites are showing that considerable care went into the selection of metal for the alloys used in particular objects, although scrap was certainly utilised.6 Amber, used like glass for making beads, could have been collected on occasional forays to the coast, just as shed antlers could have been found in the woods. The West Stow dwellers could therefore have been very self-reliant in producing objects for their everyday needs, just as they were in food; but the range of materials in use, and the variety of skills needed to produce the objects made from them, suggests a more complex system than one in which each household consumed only what it produced, and indicates a greater range of expertise than the known size of West Stow seems likely to have been able to accommodate.

Some of what was found at West Stow cannot have come from the immediate area. Fragments of lava quern-stone could only have come from the Rhineland. Four fragments of glass claw-beakers datable to the sixth century would almost certainly have been made either in Kent or in the Rhineland. West Stow must, therefore, have been involved in some exchange transactions, many of which, such as the need to acquire salt to preserve foodstuffs, would not have left any archaeological trace. Such exchanges may have been fairly infrequent, perhaps little more than annual. Nevertheless, despite the absence of evidence that the site's economy was geared to producing an exportable wool surplus, there was an ability to acquire objects that were status-supporting as well as life-supporting. Even the apparently prosaic Rhenish quern-stones should perhaps be thought of in status terms, for it would have been possible to use local ‘pudding stones’ for grinding, and a few examples were indeed found. Lava may have been more efficient, but it was also more eye-catching.

The range of objects recovered from the West Stow settlement can be compared to that from a cemetery half a mile away. Certain types of object were found at both sites, but whereas some, such as beads, are directly comparable, others, such as brooches, seem far grander at the cemetery and were presumably specially selected for burial. Because it is so elaborate, the ornament on many of the brooches can be likened to that on brooches from a myriad of other sites, in England and abroad. They probably arrived in a variety of ways—such as with spouses from other communities, as spoils of war, or in exchange for other goods or services. Some may have been made on the spot by an itinerant bronze-smith, who did not stay long enough to have to replace his moulds, leaving his old ones or his broken crucibles behind him. Some were probably new when buried, others heir-looms. Although they are not paralleled at the settlement, they are not really discordant with what was found there in terms of wealth, allowing for the inevitable discrepancy between accidental loss and deliberate deposit. The only silver pin, for example, was from the settlement, where there were also a silver-gilt buckle fragment and a silver pendant; in terms of precious metal, the settlement site holds its own against the cemetery.

Nowhere near to West Stow has been recognised as a local market centre where such goods were regularly available; only a mile away is a site at Icklingham which was large enough to have functioned as a small town in the fourth century, and where coins show use into the early fifth, but no later material such as pottery is recorded from there, nor was West Stow acquiring goods of types recognisable as developing out of the traditions of the fourth century, which would have been the case if there had been trade between two co-existing communities. Instead, the reused scraps at West Stow are of all centuries from the first onwards, which suggests that they were collected randomly from abandoned places. The local fifth-century economy must have functioned without the use of established market centres such as Icklingham, nor is there any evidence that new ones were created; instead, exchanges in basic materials must have been effected by visits to or from producers, or during occasional assemblies held for religious, administrative or social reasons. Family and personal relationships may have been the modes by which many goods went from one person to another, and barter must have played an important part where no such interdependence existed. But the Rhenish quernstones and the glass claw-beakers had to come from too far away for a system relying on face-to-face negotiations between producer and user, and promises of future requital. Any merchant bringing such things—and their provenances suggest that wine may have been coming in as well—would not have been satisfied with three dozen eggs and a day's hay-making next summer. Similarly, the objects could not have been sent directly as presents to a family member or to someone whose friendship or service was sought, for personal alliances can only operate over such a long distance amongst the rich and powerful, not at the social level of the West Stow farmers. It may be significant that the claw-beakers all date from the later part of the sixth century—the quern-stones cannot be so precisely dated—by which time it may be that a system of exchange was developing in the area between an élite group of merchants, supplementing an existing, local system based on personal knowledge and contact. Some imported and other goods may then have been passed on by the élite to their dependents.

Icklingham has not been excavated, so the history of its abandonment is not fully known. It may have been a gradual process, as it was in a comparable small town at Heybridge, Essex, in which buildings have been found with pottery of various fifth-century types; initially some of this was coming from Oxfordshire and from the Nene valley some eighty miles away, but those supplies had dried up by the middle of the fifth century and only locally-made wares were available. Occupation in Heybridge did not last until the end of the century, although the site was on the coast and potentially a port. There are very few fourth-century towns of this scale which are likely to have had a very different history, even if they survived at all into the fifth century; the reemergence of some of them as the sites of markets later in the Middle Ages could simply be because they were well-placed on communication lines, or it might possibly be because in a few cases they continued as occasional meeting-places, even if not as occupation sites. Exodus from them in the fifth century was inevitable if they were not to be market or production centres— building debris would have hindered their use even for agricultural purposes.7

A rather different picture is emerging from excavations within the walled towns. The extent to which these had operated as market places and artisan centres in the fourth century, as well as administrative, religious, defensive and leisure foci, is not well understood. Wroxeter is not the only one with standing buildings surviving into the fifth century, and in York and Gloucester collapsed tiles sealing later levels show that some structures at least remained partly roofed for several generations.8 This is not proof of continuous use, however, any more than is topographical evidence that gates or certain street lines were kept open or were re-opened. In many such towns, thick deposits of soil have been found, the compositions of which suggest that they did not accumulate slowly from rotting timbers and other inert debris, and were not washed in as flood silts, but occasionally result from rubbish dumping, sometimes from deliberate attempts to level up uneven ground. In either case, they indicate a lot of abandoned building space, but paradoxically also a considerable human involvement in their accumulation, although many seem insufficiently humic to have been cultivated.9

One possibility is that some at least of the walled towns were being used into the fifth century as centres for the collection of agricultural products. Grain driers in Exeter, Devon, and in Dorchester, Dorset, could indicate large-scale processing, just as a building in Verulamium, Hertfordshire, interpreted as a barn, may indicate a need for storage of large quantities of agricultural supplies. A function of this sort for the towns could have lasted only for so long as there was an authority which could enforce the collection of the produce, and so it is symptomatic of the changing nature of that authority that there is no sign of storage and processing after the end of the fifth century, and in most towns much earlier. It is as though a system initiated during a period of strong government operating a complex structure of control and distribution was temporarily sustained by a few opportunists who were able to usurp authority locally despite the disintegration of centralised state power.10 Their inability to redistribute large volumes of produce into a wide market might cause them only to seek to maintain that part of the system which brought them what they required for their own consumption. For this, direct supply from the producers to the residences of the powerful was more effective than collection in and redistribution from some formerly urban centre.

The loss of central authority inevitably affected different areas in different ways, as a unified state broke down into discordant parts. In Suffolk's Lark Valley, for instance, there is no known site which would seem to be ‘superior’ in status to West Stow. If Caistor-by-Norwich had been the centre of the local area in the fourth century, its decline in the fifth seems to have left a vacuum, or it may be that it is difficult to locate the aristocratic site or sites that succeeded it. At Gloucester, by contrast, there are fifth-century timber buildings inside the walls, and the town may have remained as a focal point in the area. Authority, however, probably resided just outside in the Roman fort at Kingsholm, where the burial of a man within an already existing small stone structure, and the objects buried with him, mark him out as someone of distinction who died early in the fifth century. Although there is nothing else of that date from Kingsholm, it was later to be the site of the royal palace, of which substantial timber buildings identified in excavations may have formed part.11

The precise status of the Kingsholm man is not indicated by the objects buried with him, but it may be significant that nothing about the grave suggests an intention to denote that he had been a warrior. He had a small iron knife, but it is not a weapon distinctively for use in battle, as a sword would have been. The man appears to have been wearing shoes with silver strap-ends, rather than boots, and the rest of his surviving costume fittings are not associated with specifically military dress. It was obviously not considered important to associate him in death with a warrior's life. His accoutrements and his place of burial suggest however that he was at least an aristocrat, if not an autocrat.

A site which shows how an aristocrat's life-style might have been maintained in the fifth and sixth centuries is in the far north at Yeavering, Northumberland, an inland promontory—though not hill-top—site. Timber buildings, some very large and using very solid posts and planks, were replaced at various times in a period of occupation which ended during the seventh century (1, 1).12 The site's initial use was in the Bronze Age as a cemetery, and recognition of this religious use in the past may have been a reason for reoccupation, if association with such antiquities was considered to give some claim to ancestral links, and rights of inheritance to land and authority. The reuse probably started in the fifth century as no mass-produced pottery or other fourth-century artefacts were found. The very few objects that were recovered included an elaborate bronze-bound wooden staff in a grave aligned on the largest building; its purpose is unknown, but its importance must have been clear to those who deposited it in such a prominently-placed grave.13

1, 1. Reconstruction drawing by S.James of one of the phases of the use of Yeavering, Northumberland. In the foreground is part of the ‘great enclosure’ and one side of its entrance, a fenced circle enclosing a building. If animals were brought here as tribute to the palace's owner, it is difficult to see how they could have been prevented from trampling the barrow mound (emphasised here by a totem-like post). The great hall, joined by an open enclosure to a small annexe building, would have been the focus of feasts and entertainment. Beyond, the reconstruction of the post-holes and slots as staging suggests a setting for decision-making by the leader and his people. One of the buildings in the background may have been used as a temple, as human burials and deposits of ox bones and skulls were found associated with it.

Ceremonial and ritual at Yeavering are also suggested by a timber structure, the fan-like ground-plan of which has generally been accepted as the remains of wooden staging, for use during assemblies. These occasions were presumably enlivened by feasts and sacrifices, which the ox skulls overflowing from a pit alongside one building seem to attest. Before their slaughter, the animals were probably kept in a great enclosure on one side of the site. Sheep were also taken to Yeavering, and at least one building may have been used specifically for weaving since loom-weights were found in it.

Yeavering suggests a site to which large numbers of animals came, presumably brought as tribute owed from the surrounding area to its chieftain. The feasts that were held after their slaughter would have confirmed this leader's status as one whose authority brought wealth which could be conspicuously, even recklessly, consumed; the high proportion of young calf bones suggest a profligate disregard for the need to maintain breeding herds. The meeting-place was where decisions were announced and agreed; the biggest of the buildings is interpreted as a hall where the feasts took place and oaths were sworn. These occasions were used to reinforce social ties that bound people together, as lord and dependent. Nor is Yeavering unique, since there is a site not far from it at Sprowston which seems to have most of the same features, except for the assembly-place, and at Thirlings, also in Northumberland, a complex of rectangular buildings, one some twelve metres long, has been investigated.14 Dating is not precise at any of these, but that the Yeavering staging was enlarged from its original size could be an indication that a larger group of people was becoming involved in the affairs conducted there as time passed, as though the authority of the ruler was becoming extended over a wider area.

Nowhere that has been excavated in the south of England has shown evidence comparable to Yeavering's. In the south-west, and possibly further east in a few cases, hill-top sites may have been used by the aristocracy, but it is difficult to establish the precise functions of those places where some evidence of activity has been found. Glastonbury Tor, Somerset, was initially interpreted as a chieftain's residence, on the basis that animal bones suggested food inappropriate to the religious life, but that is now seen as too exclusive an interpretation.15 Activities there included metal-working; crucibles were found, and copper-alloy residues and a fine little head. Dating depends upon Mediterranean and Gaulish pottery imported into the south-west in the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries, bowls and dishes being recognisable as having been made in the East Mediterranean and North Africa between c. 450 and 550.16 Most such sherds are from amphorae, which were probably reaching the south-west as wine containers, so their presence at Glastonbury Tor suggests drinking of an exotic rarity at the feasts of those who managed to obtain it. But the bones found there do not suggest such high-quality consumption; most of the beef and mutton came from elderly animals, not young stock which would have provided the most succulent joints, as at Yeavering.

The meat consumed on Glastonbury Tor was nearly all brought there already butchered and prepared, which is hardly surprising on such a small site where there would have been no room to do the slaughtering. At Yeavering, the great enclosure and the ox skulls suggest that animals were brought on the hoof; only one quern-stone was found, however, which could indicate that most of the grain arrived already ground into flour. A good standard of agriculture would have been necessary to supply Yeavering and the other residences used by a chief and his entourage as they progressed round their territory. Various pollen studies from the north of England show no decrease in meadowland and cereal plants in the fifth century, though some show regeneration of scrub and bog during the later sixth; but these analyses have to be made on sites which, being prone to wetness, have low agricultural potential and are inevitably therefore marginal and not necessarily representative of what was happening everywhere. It is even possible that poorer land was being farmed in preference to better, because the latter tended to be in less remote areas and was therefore more vulnerable in troubled times to slave raiders and other disrupting agents.17 Nevertheless, the evidence from the north seems to support that from West Stow in the east, of reasonable standards being kept up.

The extent to which actual fields and field systems were maintained, abandoned, or allowed to revert from arable to grazing land is not easy to evaluate. On the one hand, there are areas like the high chalk downs in Hampshire, where field boundaries of the fourth century or earlier have been found in what is now thick woodland, and so may never have been used again. In north Nottinghamshire, field boundaries can be seen to have grown over, and to have had no later use. The opposite has happened elsewhere, however; from Wharram Percy, in the Yorkshire wolds, and other sites has come evidence of ditches which were filled up during the third and fourth centuries, but which remained as boundary lines into the Middle Ages and are identifiable as furlong boundaries in strip-field systems. Such cases may only mean that the ditch created a conveniently visible line for later farmers to follow—or one which still affected drainage so that it could not be ignored—and there may have been an intervening period of disuse.18 There is also Nature to consider; flooding and raised sea-levels certainly affected parts of northern Europe, such as the Low Countries, and some low-lying land was probably lost in England as well, creating the Isles of Scilly, for instance, though some of the fens and marshes may have resulted as much as from failure to maintain drainage systems. Certainly flood deposits recorded in some towns are more plausibly attributed to the collapse of sewers than to increased rainfall or rising sea-levels.

It is proving very difficult to find field systems that can be directly associated with the rural settlements that have been located. Around West Stow, for instance, there are no surviving field boundaries or scatters of pottery resulting from manure spreading to indicate whether an infield/outfield system was operated, with arable fields adjacent to the site and rough grazing further away, or with all the land available to the settlement being ploughed at least periodically. It is now established that strip-fields with their ridge and furrow, characteristic of many areas later in the Middle Ages, were not yet introduced, as no such strips and furlongs underlie sites that came into use in the seventh century as they do under some sites of the eleventh, nor can they be seen to radiate out from any fifth- or sixth-century settlements later abandoned. It can also be assumed, from the locations of most of these last, that light soils such as river-gravel terraces, sands and chalks were in use: place-names attributed to the fifth, sixth and seventh centuries show a strong sense of terrain and topography. That leaves unresolved the problem of whether heavier soils such as clays were still ploughed, perhaps from existing sites, or were allowed to revert to rough grazing or scrub and woodland. The Lark Valley again provides an example of the problem: if people were still living in the fifth century at sites where pottery scatters suggest that they had been in the fourth, they have left no trace of themselves, which is not impossible if they did not adopt new burial customs, were no longer acquiring the types of objects available to them before, and eschewed the use of crude, hand-made pottery in favour of wood and leather. Such an aceramic situation can arise: in Gloucester, various sites had been excavated and little pottery found, yet a previously unknown ware was discovered in some quantity in a recent excavation close to the wall of the Roman town. In the Lark Valley, re-emergence of enamelling on metalwork in the sixth century could be evidence for the survival of knowledge of that craft among people for whom its use was traditional, unlike those buried in the cemetery near West Stow.19 Nevertheless, abandonment of many settlement sites in favour of those on lighter soils does seem the most likely pattern in most areas, and would have been facilitated by any weakening of the legal restrictions that tied people to their homesteads. Decline in population, through plague, migration, or falling birth-rates— often a demographic response to adversity—may have been another factor, but one that is extremely difficult to measure in a period of rapidly fluctuating change. There seem to have been fewer large cemeteries in the sixth century than the fifth, but there are also more smaller ones, so that the change may reflect changes in ideas about appropriate burial-places, not in population totals.

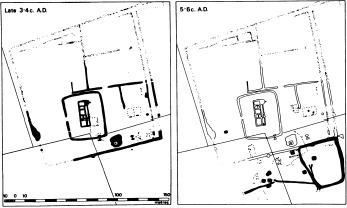

Some rural sites used in the fourth century were also used in the fifth. Although the stone buildings at Barton Court Farm, Oxfordshire, were demolished, activity in and around them continued into the sixth century, with timber buildings and burials, the latter not necessarily of people who had lived on the site, since the objects with them suggest a mid sixth-century context, by which time the timber buildings may have been abandoned (1, 2).20 Connections between the fourth and fifth centuries are hard to evaluate, but nearly all the latter's buildings were outside the former's enclosure, and the pottery and other objects used were very different in kind. The culture was different, even if the land area utilised may have been the same. Other sites have reported a comparable pattern, such as Orton Hall Farm in Cambridgeshire. At Rivenhall, Essex, a stone complex had a timber structure built over it, and there were then burials before the area was used for a Christian church and cemetery. Although the dating is uncertain, this could indicate an élite site remaining in use through from the fourth century so that its owners eventually became the owners and builders of the church, a sequence that could be more common than has been realised.21 Field patterns in Essex also suggest the continuing importance of existing boundaries.22

1, 2. Romano-British and later phases at Barton Court Farm, Oxfordshire, excavated by D.Miles. An eight-roomed stone house was demolished after c. 370, other buildings surviving a little longer. Sunken-featured structures, fence-lines and burials followed, but not in arrangements which suggest that they had any direct connection with the previous use of the site. The new enclosure emphasises this break: it is almost as though for most purposes the earlier lay-out's effect was a negative one, and its structures were avoided except for burials—which could be later than the sunken-featured buildings.

Cultural differences seem to be even more clearly revealed in studies of burial practices. In Essex, there are considerably fewer cemeteries in which people were buried with grave-goods than there are in other eastern counties. Yet even in areas in which objects are found in quantity, there is little uniformity. An analysis of two cemeteries some twelve miles apart has shown the subtlety of variation that can occur. The artefacts in the graves at the two sites were not significantly different in type, but there were differences in the ways in which they were deposited. In Holywell Row, near Mildenhall, Cambridgeshire, knives were found in most of the graves of both males and females, as though they were primarily a symbol of adulthood, whereas in Westgarth Gardens, near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, knives were found much more frequently in men's than women's graves, as though there they usually signified specifically male adulthood. There were also differences in the way that the cemeteries were arranged—children were kept more separate from adults at Westgarth Gardens, but male and female adults were more intermingled.23 Differences like these are at least as important as differences between the objects, particularly since they held good for several generations, which suggests surprisingly stable communities retaining variations in their burial customs despite the intermingling with neighbours through marriage and other social alliances that must surely have taken place. In times of stress, even quite small groups of people may be tenacious of their customs, to emphasise their sense of community.24 With localized differences like these, it becomes difficult to put too much weight upon grave-goods as an indication of wealth. A cemetery in which there are many elaborate brooches may be the burial-place of people richer than those in a cemetery with few such exotica: or it may just be that one group thought it appropriate to festoon their dead, while another did not.

In many parts of the south and east, cremation as well as inhumation was practised. Only a mile from West Stow and its adjacent cemetery, though separated from it by the River Lark, is a totally contrasting cemetery which contained, so far as is known, nothing but cremations. Was Lackford for people of particular distinction, or particular infamy, or race, or family? At another predominantly cremation cemetery, Spong Hill, Norfolk, excavations are making it possible to observe variations in the contents, fabrics, sizes, shapes and locations of burial urns. From this it may be possible to suggest that particular kin-groups can be identified, and to reveal attitudes to age and gender. Children were often distinguished from adults by placing them in smaller pots, as though to acknowledge that they had not attained full membership of the community; women usually have more accompanying objects than men, as they do in contemporary inhumations; taller pots with what seem to be ‘higher status’ objects such as playing-pieces may notify the resting place of those higher in the social hierarchy.25

Identification of the sex of cremated bones is usually very difficult, but even bone from inhumation does not always survive in good enough condition to be fully analysed. At Sewerby, East Yorkshire, the sex of several adults could not be recognised, and some uncertainty is created amongst the rest by two identifications of bones as being those of males although they were accompanied by objects normally associated with females, which may indicate aberrant behaviour if it does not indicate the limitations of sexing criteria.26 No-one seems to have been buried in this small assemblage who was aged less than seven or over forty-five; presumably the former were disposed of elsewhere—but did the community have no venerable elders, or were they also given special burial treatment?27 One man had had a bad injury or wound which had damaged his forehead, but it had partly healed, and other bones did not have the sort of breaks and cuts that a violent society, or one regularly engaged in warfare, might be expected to show. Similarly at Portway, near Andover, Hampshire, only a single wound could be recognised.28 At that site, infants as well as youths and adults were buried, though baby bones had mostly rotted away if they were ever present. Childhood and youth were vulnerable periods, with a one-in-three chance of dying before the age of fifteen; the three years from fifteen to eighteen were relatively safe; the death-rate then rose steadily to the end of about the fortieth year, reached by fewer than a quarter of the population. A small number of people older than forty-five were buried at Portway, however, which shows that some reached a greater age than Sewerby would have suggested possible.

The approximate age-at-death of a reasonably well-preserved skeleton is not difficult to estimate; nor is the average height. Some graves have produced ‘giants’ over 6ft 6ins, but Portway produced no-one over 5ft 11ins and Sewerby's tallest was only 5ft 8ins; 5ft 1in was the smallest recorded there even for a female, however. The heights measured in these cemeteries are of well-grown people, which is some indication that adequate food supplies were available for the whole population. There are occasional signs of deficiency-related problems in the bones, such as cribra orbitalia which can result from insufficient iron in the food, but this was recognised in only two of the Portway skeletons. Many more such investigations are needed before the population's true profile can be established, but there is at present no evidence that some people were consistently deprived of access to a sufficient share of the food resources, or were particularly protected from strains of manual labour. This is not quite in keeping with what might have been expected from the quantities of objects in cemeteries where grave-goods occur; the number of objects varies from grave to grave, with many having nothing at all in them. This could be taken to suggest a wide range of status variation, even within small communities, but it may actually reflect differences in ideas about goods-deposition during the time that a cemetery was in use; there seems to be an increase in quantities generally in the sixth century.

Grave-goods are usually taken to indicate that the people responsible for providing them believed in some sort of after-life, or perhaps a world of gods and spirits running concurrently with the human world. Since tools are infrequent, goods do not seem to have been meant for ‘use’ but may have been symbols—weapons to identify the status, or brooches the family, of their possessor. Occasionally, it is possible to go further; some of the designs are recognisable as being the same as symbols associated with particular gods whose names and deeds are recorded in north European sagas written down in later centuries, and the use of other motifs on both pots and brooches may signify that they are family emblems. In the west, both a hill-top site at Cadbury-Congresbury, Somerset,29 and Wroxeter have had finds that may indicate a skull or head cult, which could have Celtic antecedents. Is the Glastonbury Tor copper-alloy head another example? Several western temples or shrines have produced evidence that a site was still used in at least some way after the fourth century; near that at Brean Down, Somerset, burial seems to have continued into the seventh century, and at Uley, Gloucestershire, there is evidence of a shrine completely remodelled at the end of the fourth century that remained active for a long time thereafter, possibly converted to Christian usage.30 There is no archaeological, as opposed to documentary, evidence that Christianity, which had been widely though not exclusively practised in the fourth century, was still practised anywhere in the fifth, until the appearance of memorial stones. The earliest of these, such as one from Wroxeter of the late fifth to mid sixth century, may not be Christian, as they record simply the names of fathers and sons; distinctively Christian formulae such as ‘Hic iacet’ do not occur until the sixth century. Their distribution in England is then confined to Cornwall and Devon, with outliers in the extreme southwest of Somerset and at Wareham, Dorset.31

Also exclusive in its distribution is the imported Mediterranean and south Gaulish pottery, found at various sites in Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, but nowhere further east. Some of the ‘A’ ware bowls of c. 450 to 550 have incised crosses, and so were at first thought to have been for use in the Christian Mass with the wine that would also have been needed at such services, but the quantity of this imported pottery that has now been found at a variety of sites indicates that it did not have exclusively religious use. The difficulty of establishing the real nature of those sites has already been referred to in relation to Glastonbury Tor, and is well illustrated by Tintagel, Cornwall, where excavations on the peninsula in the 1930s produced evidence then interpreted as identifying a Celtic monastery. More recent work has recognised that that part of Tintagel has no burials or other proof of Christian use. The quantity of imported pottery could be because there was a landing place, and the goods arriving there may not have been consumed at Tintagel. There are, however, timber structures and hearths which show that there was occupation, and mounds in the graveyard of the present church on the mainland suggest the possibility of barrow-burials of people of high status. It therefore seems that Tintagel was a residential complex, perhaps visited seasonally by a wealthy element who controlled the resources of the local territory.32

Tintagel is not apparently a very good harbour, though usable; an example of a site which may have been more inviting as a coastal trading-station is at Bantham, South Devon, where middens, rubbish pits, hearths and traces of structures have been found. A variety of objects, including a number of knives and other iron and bone tools, suggests crafts being practised, and animal as well as fish bones were found in some quantity, indicating that this was not simply a site specialising in the exploitation of marine resources for food. There were also imported pottery sherds, mostly ‘B' wares, particularly handles of amphorae, suggesting breakages. Bantham may well have been a landing place, therefore, perhaps a ‘beach market’ only used seasonally, as it is too exposed to make a comfortable winter residence.33 Goods landed there were probably passed on to consumers elsewhere. That Devon and Cornwall possessed an aristocracy able to command such things is suggested by the memorial stones with their formulae stressing the male line of family descent, which presumably enhanced claims to inherited rights and property. They were in a good position to control the peninsula's trade, particularly perhaps the production and export of its valuable metals, notably tin; ingots at Praa Sands, Cornwall, where radiocarbon dates centring on the seventh century have been obtained, may indicate the whereabouts of another landing place like that at Bantham. Gwithian, Cornwall, may be another, but it also served as an agricultural site, since there are traces of scratch-ploughing associated with it. Its small, drystone-footed huts do not suggest high-status use, but there is a quantity of imported pottery from it. If that was not being passed on up the line to a superior site, it suggests a remarkably high standard of living for ordinary farmers.34

Pottery found at some south-western sites indicates where the local aristocrats were probably living. In Cornwall there are enclosures called ‘rounds’, such as Trethurgy, where much ‘A’ ware has been found. These ‘rounds’ were not necessarily new sites in the fifth century, and suggest less disruption to settlement patterns than occurred further east. Their surrounding banks would have distinguished them, and thus their owners, from their neighbours. Such sites have not been identified in any other county, even Devon; the best candidate there for a place of comparable status is High Peak, on the coast near Sidmouth, where ‘B’ ware has been found, but in circumstances that do not explain its context. The site is a prehistoric hill-fort, with a stone wall revetting the banks, but it is unlikely that this was contemporary with the pottery. In Somerset, the Iron-Age hill-fort at South Cadbury was certainly given a stone and timber wall on its existing top rampart, and there is evidence for timber gates and wall-walks. ‘B’ wares were among the finds from it.35

The cultural differences between the four most south-westerly of England's later counties are worth stressing because they illustrate how divergent were different areas: only Cornwall has ‘rounds’; it also has stone-lined cist graves, unknown in Devon, whereas both Dorset, at a cemetery at Ulwell, and Somerset at Cannington, have them.36 Devon and Cornwall have memorial stones, otherwise found only in the extreme south-west of Somerset, and in Dorset only at Wareham, where there is a group of five, none necessarily earlier than the later seventh century. At Poundbury, outside Dorchester, is a cemetery which probably had some use after the fourth century. There is no trace at Maiden Castle or at any of Dorset's other hillforts of the sort of reuse found at South Cadbury in Somerset. All that is firmly datable to the sixth century is a small cemetery excavated at Hardown Hill, near Bridport, where the objects are like those found in counties to the east.37

No ‘A’ or other such imported wares have yet been found in Dorset, or anywhere east of Somerset. Their distribution is clearly owed to contacts that some, but not all, parts of the south-west had with the Mediterranean and, into the seventh century, southern Gaul. Further east, different overseas contacts can be demonstrated; there are sufficient objects that must have originated in the areas on the Continent controlled by the Franks for it to be possible to argue that they signify not only the importing of prestigious material, but actual immigration of Frankish people.38 So similar to cremation urns in the area of north Germany around the rivers Elbe and Weser are some in certain cemeteries in Norfolk that it seem impossible that they should not have been made by potters from that area who had settled in East Anglia.39 There are bracteates, brooches and other objects which suggest strong contacts between Kent and modern Denmark. Further north, in Humberside and East Anglia, wrist-clasps indicate contact with Norway. But some of the wrist-clasps were buried in England in positions which suggest that they were not all worn on the ends of sleeves, and almost all were worn by women, whereas in Norway a significant proportion were also worn by men.40 Slight though these differences may be, they underline the difficulty in knowing how far objects can be used to measure direct migrations of people, rather than links created through trade, through formation of family and political alliances, or through exchanges created by the unknown demands of some religious cult. Similarly, to trace the internal distribution of a particular type of brooch or pot may be to trace the settlement progress of immigrants who used it, but is as likely to be to identify a particular local custom not directly associated with an ethnic group, and the appearance of the object may owe more to burial rites and any changes to them than to an actual spread of the object's use.

Many objects in use in the fifth century, such as the distinctive quoitbrooches, cannot be associated with any particular continental area, because they are heavily influenced by styles of costume and decoration that originated in the fourth century in the Roman provinces.41 Contacts between those who lived on the two sides of the formal frontier led to a fusion of ‘classical’ Imperial and ‘barbarian’ Germanic tastes. Consequently objects cannot usually be used to indicate the precise origins of those who made or owned them. Some brooches, such as simple discs with ring-and-dot ornament, are common to a number of areas in England, whereas some, like square-headed brooches, can be grouped into sub-divisions which are geographically confined. These may not indicate significant cultural divisions, however, so much as the area in which a particular family dominated, or even where a single craftsman's output circulated. They do not even make clear-cut frontiers between ‘British’ of native descent and ‘English’ immigrants; penannular brooches were certainly made by the former, but are frequently found deposited as grave-goods in the manner assumed to be characteristic of the latter.42 Such things suggest a great deal of interaction between peoples of different origins, and much acceptance of others’ fashions and modes of behaviour. It is likely that it was not just superficialities that were accepted; many burials in the cemeteries of eastern England may be of predominantly indigenous people who had accepted new customs, willingly or not. Similarly there may well be English stock in at least the latest phases of unfurnished cemeteries like Cannington, which had come into use long before migration is likely to have reached so far west. In some areas, distinctions may have been carefully retained if co-existence was uneasy. The upper Thames Valley has many cemeteries with fifth- and sixth-century grave-goods, yet outside Dorchester and at Beacon Hill, Lewknor, Oxfordshire, are large graveyards with virtually no objects, but fifth- and sixth-century radiocarbon dates show that they were in contemporaneous use.43

It is not only objects used and funerary rites practised which are studied to try to distinguish between peoples of different origins. As an increasing number of buildings is revealed, they too can be considered. The most distinctive fifth-century and later structure has a sunken area, sometimes apparently floored over, as can be demonstrated in one or two of the seventy-odd examples at West Stow, but more usually using the lowered ground surface as the floor. Because they would have been cool and moist inside, they are thought especially suitable for craft activities such as spinning and weaving, as thread and yarn must not become dry and brittle. They have been found as far apart as Yorkshire and Hampshire; there are even a couple as far west as Poundbury at a late, probably seventh-century stage in that site's use, after it had ceased to be a cemetery.44 There are also examples on the Continent, in the Low Countries and Germany. Many larger, rectangular timber buildings are now known. Their origin is uncertain, for whereas their plan is like that of Roman buildings, such details of their construction as can be postulated from the traces of timbers in the ground suggest that they were not built in the Roman manner, but had external buttresses, ridge-beams and pairs of opposed doors. They suggest a fusion of ‘British’ and ‘Germanic’ modes, widely spread; building styles seem less geographically confined than many artefacts.45 It is also worth noting the absence of any features in the buildings at Yeavering to mark any point at which ownership passed from one cultural group to another. Either fusion there was complete, or the place was owned by ‘Germanic’ people from the start, even though it is in an area well to the north of those in which fifth- and sixth-century ‘Germanic’ cemeteries are found.

Certain types of buckle and strap-end of the later fourth and the first half of the fifth centuries are thought originally to have been issued by the Roman authorities to barbarian warriors brought over for defence against pirates, and later by those ‘British’ who were trying to maintain Romanised authority. One British writer, Gildas, knew the word foederati that had been applied in the Roman Empire to barbarian troops used on the frontiers in the hope that they would defend it against other barbarians.46 The claim that examples found in England in fifth-century contexts must have been associated with ‘mercenary’ soldiers assumes a continuity of practice that runs counter to the general evidence of the speed of fifth-century change; a buckle type originally issued as military wear might quickly become an item of dress not specific to a soldier. Furthermore, as organisation broke down, specialisation of that sort would have disappeared, as defence became a preoccupation of all holders of land. It is also sobering that the best-known graves in which early ‘Germanic’ objects were found, outside Dorchester, Oxfordshire, did not certainly have weapons with what is thought to have been the one male burial; but iron objects were reportedly thrown away, so he may have had at least a knife or spear.47 Those graves are the only ones of their kind known, so they do not establish a pattern.

Because so much of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and other sources are written in terms of warfare, it has usually been assumed that confrontation between different groups of people, particularly natives and immigrants, was the norm. Archaeological material is used to try to prove or to disprove the conquest of a particular area by a particular group at a particular time (e.g. 1, 3). But most of the dates in the documents are no less problematical than those that can be attributed to the archaeological record, and it is not until the end of the sixth century that a clear narrative framework begins to emerge. As the end of the formal administration of Britannia by the Roman Empire removed from the province the stability of an imperial system based on taxation and a standing army, so the economic system of big estates, perhaps associated with ‘plantations’ of slaves, and the wide distribution of bulk products and of money could not be maintained. The eastern side of the island was both closer to the Continent and had been more Romanised than the west; consequently its social and economic structures were more complex and more liable to collapse, and it was more open to migrant peoples. Yet even Essex and Kent, on the two sides of the Thames, seem to have varied in their patterns of settlement. Some areas retained more ability to resist change than others, but the unity of Britannia broke down into parcels of separate elements, in some of which more signs of élites and power structures are recognisable than in others. Some of these separate elements may be thought of as no more than bands of kin-groups in loose alliance with or actively hostile towards their neighbours; others may be classified as tribal confederacies, though probably ethnically mixed; and others, in the north and west at least, may have evidence of chieftains. What the lack of uniformity shows certainly to have been lacking in this plethora of human conditions was the overriding authority of a centralised state.

1, 3. Old Sarum, Wiltshire. The Iron-Age ramparts might have sheltered an army when ‘Cynric fought against the Britons at the place which is called Salisbury’ in 552—but even if the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is correct about site and date, the record need not mean more than that Sarum was a landmark close to where the battle took place. Cemetery evidence suggests that people using English burial customs were already established in the area: a victory for Cynric may have been a stepping-stone in the progress of his dynasty, but not in that of the Saxon settlement. In the early eleventh century, Sarum became a place defended against Viking raiders, but the castle ruins and the outline of the cathedral attest its Norman use. As a town, Sarum was replaced by Salisbury in the early thirteenth century: its numerous inhabitants, intra- and extra-mural, have left no visible trace, a reminder of the difficulty of recognising many sites even from the air.