Chapter Seven

THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES

Community and Constraint

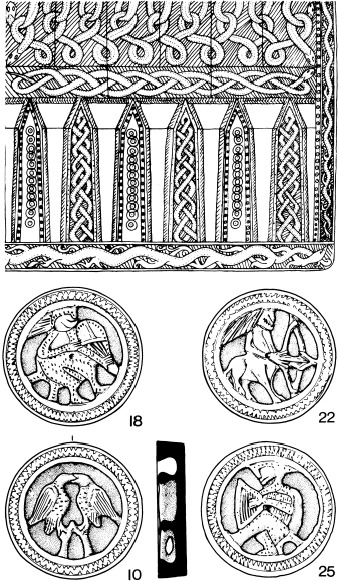

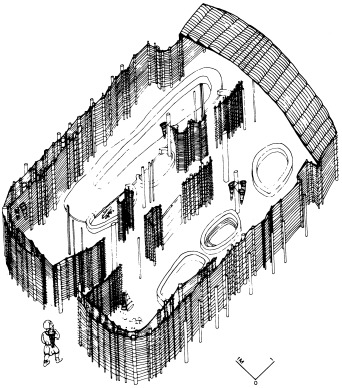

Archaeology is concerned with interpretation, and excavation is a process for recovering information from which hypotheses can be constructed. Nevertheless, even the most hardened excavator may still admit to pleasure at finding ‘things’, whatever their potential for elucidating the society that produced them may be. So it is difficult not to feel envious of the digger who discovered thirty finely-carved gaming-pieces, with parts of the board on which they were used, in a late eleventh-century rubbish-pit on the site of the early Norman castle at Gloucester (7, 1). Their full character was only revealed, of course, after careful conservation, which established that there are fifteen antler and fifteen bone pieces, a complete set for use in Tables, a game of luck and skill similar to backgammon. The pieces are carved with a variety of astrological signs, animals, and biblical and other scenes such as were widely used in Romanesque sculpture. On bone strips which would have been nailed onto a wooden board to make the playing surface, there is interlace and animal ornament, some of it in the Scandinavian ‘Urnes’ style current in the second half of the eleventh and first half of the twelfth centuries.1 ‘Urnes’ was the last significant northern contribution to European art in the Middle Ages, and seems to have been expressing very different values from the Romanesque. To have the two in combination is to have a rare cultural antithesis.

The Gloucester Tables set is particularly interesting because of its discovery within a castle, the milieu of kings and barons. Gaming-counters in pagan burials are associated with people to whom high status can be attributed, but the discovery at York and elsewhere of many discs and cones used in board games suggests that such pastimes became more widespread. Tables, however, seems to have been unknown in England before the eleventh century: it is different from simple games like Fox and Geese or Nine Men's Morris in that it requires rather more skill, and since it lends itself to gambling, it can be a game for the rich. Another introduction of the same period was chess, subtly adapted from its oriental version to reflect European feudal courts, with queens replacing vizirs, castles chariots (but retaining the Arabic name rukh) and bishops, unflatteringly, elephants. Chess is a game of skill, time-consuming to learn and to play, so that only those with leisure could indulge in it: its need for intelligence and subtlety flatters the self-esteem of the good player, gambling is possible, and it can be played between men and women. Consequently it is ideal as a courtly pursuit, and several chess pieces have indeed been found in appropriate contexts such as the castles at Northampton and Old Sarum.2

Opposite: 7, 1a. The Gloucester Tables set. The drawing by J.Knappe shows a reconstruction (at about one-third actual size of the board). The selection of playing counters, drawn (actual size) by P.Moss, indicates the contrast between their Romanesque style and the Anglo- Scandinavian ornament of the board.

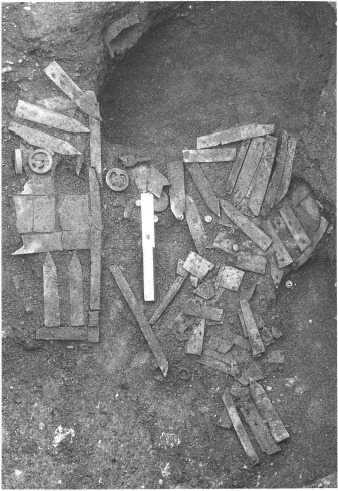

Above: 7, 1b. The Gloucester Tables set during excavation.

Chess pieces are not only known from castles—one was recently found in the middle of Dorchester, Dorset, for instance3 —and any type of artefact is unlikely to be found only in very exclusive contexts. Nevertheless the artefacts found at twelfth-century aristocractic sites and those from other types of site indicate the nature of the luxury goods that feudal magnates required for their status. Musical instruments, for instance, even simple bone flutes, represent another leisure activity. Surprisingly frequent are gilt copper-alloy strips, presumably for nailing onto wooden or leather caskets, indicating superior decoration on functional items. Castle Acre has yielded both a crystal gemstone and a fragment of a glass drinking vessel.4 A different type of consumption is indicated by the large numbers of horseshoes and nails that are usually found, as well as the rather fewer fragments of armour, which emphasize the high cost of equipping and maintaining mounted cavalry. The castles do not seem to have been production sites, except for black-smiths’ work: they were essentially centres of consumption, without the mixture of functions recognisable in some earlier aristocratic enclosures.

Some twelfth-century castle ‘finds’ do not differ materially from those from other sites: in particular, the range of pottery at them does not show any marked use of higher-quality ceramics, such as glazed wares and imports. Pottery was presumably for the kitchens, and was not something that reflected a lord's status. What was actually cooked in the kitchens certainly shows status differences, however: deer bones, which indicate venison; younger animals, more tender meat; a different selection of bones, steaks and chops rather than stews.5 Young pigs, the only ‘entire’ carcases traceable at Portchester Castle, were probably spit-roasted.6 Swan, wild goose and duck, partridge and hare suggest lords’ near-monopoly of the country's non-domestic resources, just as occasional hawk bones indicate one of the ways in which the delicacies were obtained. Nor do such things come only from rural castles where they could easily be acquired locally, for urban castles such as Baile Hill, York, also show much higher numbers of different species relative to the numbers of bones than the surrounding town rubbish pits produced.7 By the end of the century, rabbit was beginning to appear, and fallow deer were replacing red deer in most areas. There is such a high proportion of deer bones at Barnard Castle, Co. Durham, that there may have been slaughter there for sale of meat on the open market,8 though records of distributions of fish from the royal or episcopal ponds show that such products were not usually sold, but taken to the owner's other properties for his own consumption or distributed as gifts to those whom it was wished to favour.9 Fishponds, dovecotes, deer parks and artificial rabbit warrens provide a good measure of the increased attention that was given to careful husbandry and management of a variety of different creatures, all of which gave the wealthy a greater choice and flexibility in their food, and upon which very considerable human effort was expended.

There are perhaps slightly more coin finds at castles than at other sites, but they are not frequent—Hen Domen has yielded nothing earlier than a halfpenny of King John, for instance.10 In general, the quantity of finds suggests places where there were occasional losses by people rich enough to have coin in their purses, but who were not regularly opening them to make payments. There were few wage earners receiving cash if household work and garrison duty were done by those who owed service, and consequently servants and soldiers had little money to lose. One form of involvement that castles had in the use of coin is suggested by the tumbrel, a balance used for checking the weights of pennies, found at Castle Acre:11 its use was illegal except at mints, and it suggests illicit checking by a careful steward of the rent and tax payments being brought there.

The conspicuous expenditure of the great lords is also of course shown by the physical structure of their castles, as well as by what can be found in their rubbish pits. A castle was a ‘symbol of lordship’,12 its size and scale adjusted as much to its owner's status as to any practical need of defence. Earth and timber castles remained effective until the middle of the twelfth century, many being hastily constructed and as quickly abandoned in Stephen and Matilda's wars, but there is a long list of sites to which keeps, bailey walls, gatehouses and wall-towers were added, all in stone. Although timber buildings remained even in royal palaces like Cheddar, it was stone and dominance that mattered. Particularly in the second half of the twelfth century, as it became increasingly necessary to keep miners and siege engines at a distance, the curtilages of castles were enlarged and providing stone defences on a yet bigger scale was a huge expense, to be afforded only by the king or a principal baron. Whereas at the start of the century a serviceable motte-and-bailey was within the range of almost every knight, he could later beggar himself by trying to keep up with the Warennes. As the scale of building increased, so did social disparities.

The trend towards bigger and more elaborate castles is exemplified at Gloucester, where the Tables set was found on the site of an early Norman earthwork motte-and-bailey. This castle was additional to the extra-mural royal palace at Kingsholm, which seems to have continued in use for state occasions, probably because it was less restricted in size. The early Norman castle, like some others such as Canterbury's, was actually abandoned during the twelfth century; excavations have shown that its bailey ditch was deliberately backfilled, although the site was not built over despite being within the growing town. Probably this was to keep a clear space in front of the new castle which was built on an immediately adjacent piece of land acquired by King Henry I between 1110 and 1120. This area backed onto the River Severn, and the reason for the new building may have been to improve control over the waterway.13 Certainly it was in the twelfth century that Gloucester's quayside was developed: whatever remained of the Roman wall was demolished, and pottery has been recovered which shows increased activity, with evidence for both tanning and dyeing. New bridges are recorded, with the consequent effect on water flow in the river channels being partly responsible for the growth of the new occupation zone because the changes affected ships’ access.14

St. Peter's Abbey at Gloucester is a typical Norman refoundation, the work of an energetic abbot who lived to see his great church completed in 1100 after eleven years’ work, with a community of a hundred monks.15 It attracted substantial donations, perhaps because the king was a frequent visitor to Gloucester, and completely overshadowed the Anglo-Saxon establishment of St Oswald's Priory, which followed a course typical of many of the pre- Conquest secular priests’ houses by being converted in the twelfth century into an Augustinian priory. Its church was not neglected; a north aisle was built, with an arcade cut through the existing Anglo-Saxon nave wall, and a western extension was added in the following century. But it never again had the prestige or commanded the income which it must have enjoyed as the mausoleum of Aethelflaed and St Oswald.16

The stimulus to Gloucester's commerce provided by castle and major abbey in bringing people and goods to the town is presumably one explanation for the increased activity around its waterfront. The importance of riverside land in such towns had already been demonstrated in London, where the shore-line was being embanked in the eleventh century. Twelfth-century work of that sort has not been identified, although several towns are like Norwich where a shift of site of the main waterfront activity is suggested by the abandonment of the ‘hard’ near the cathedral.17 These topographical changes in the later eleventh and twelfth centuries seem to be caused by new works like bridges and castles, and not yet by the demands of new types of sailing vessel with deeper draughts. Although recovery of Baltic and Scandinavian wrecks shows that carrying capacities were increasing, it is only possible to demonstrate the same in other parts of Europe by inference. England can, however, claim the earliest representation of a ship with a stern rudder, a feature significant in allowing the development of bigger ships and new sailing techniques, which is clearly carved on the late twelfth-century font at Winchester.18

Growth of commerce was the main reason for the creation of many new towns in the century after the Norman Conquest, the biggest of which were ports. At Lynn, Norfolk, irregular ground around St Margaret's church may result from great mounds of sand discarded from the salt-extraction process which probably marked the first activity at this river mouth site on the Wash.19 By 1096 there was a market and fair, so Lynn flourished though without the benefit of the trade brought by a castle or major church. Boston, also on the Wash but further north, developed at the same time. To the south, Yarmouth had probably begun a little earlier, for excavations there have produced a coin of Edward the Confessor, and eleventh-century pottery.20 East coast trade was obviously buoyant again, even though the Flemish cloth industry may have continued to restrict English competition. Existing towns like Lincoln and Stamford prospered as cloth producers, but it does not seem that demand was sufficient to create new centres. Nor did all towns flourish: Thetford went into rapid decline, with its main urban area falling into disuse. There is little twelfth-century pottery from it, and no post-1100 coins. Some of the activity may have shifted north of the river, where the castle was constructed, but in effect Thetford had ceased to be a major town by the middle of the twelfth century. This change in fortune might be attributed to navigational problems on the river and competition from Lynn, but there is no similar decline at Norwich or Lincoln, threatened by Yarmouth and Boston respectively. The loss of the bishop's seat is hardly a likely factor, since it was at Thetford only from 1071 to 1095. It is just possible that vigorous competition from Bury St Edmunds was responsible, but there is as yet no full explanation for the way that Thetford runs counter to the general urban trend:21

Lynn, Boston and Yarmouth are three of the most successful of the towns added into the growing economic system. Most of the others were considerably smaller, providing marketplaces and minor services for their surrounding areas: most are better known from documentary and topographical than from excavated evidence. Sizes and numbers of towns varied widely according to region: local wealth was obviously a major factor, but so was the nature of the local economy and transport system. The contrasts between areas concentrating upon meat and dairy products and those where wool, cloth and grain predominated are usually apparent from the greater distances between the latter's markets, and towns like Lynn have large marketplaces which reflect the scale of the bulk goods that were being handled in them. Many towns are on or close to geological and environmental boundaries, where, for instance, a cereal district could exchange products with one that had a pastoral bias.22

Wool and cloth rather than grain are usually reckoned to have been the staples of England's medieval economy, although there may be a bias in the records causing them to be a little over-emphasized so far as East Anglia is concerned. The wool trade leaves virtually no direct physical trace: the cloth industry can be seen most clearly in the residues of the dyeing and fulling processes because, like tanning and flax-retting, they required large quantities of water; diversion of streams through streets and tenements can be shown in low-lying locations in towns like Winchester, where timber-lined channels and pits can be attributed to this sort of activity.23 Not all the myriad of small trades attested in the documentary evidence can be directly observed in the archaeological record: ale brewers, cooks and tailors do not make an obvious physical impact. Their production was for the immediate market: such traders did not have the same potential for capital growth that manufacturing industries could have. On the other hand, they may have been prepared to pay higher rents for direct access to their points of sale, so that commerce may to some extent have driven out production as markets grew. At any rate, this could be a reason for one trend of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the almost total abandonment of urban pottery kilns.

Because Thetford itself virtually disappeared, so would its pottery industry have done, whatever general trends might have been. But even before the end of the eleventh century, rural kilns were producing wares similar to Thetford's, for they have been found at Grimston, Langhale, and Bircham in Norfolk, the first of which was to be a major production site for the ensuing centuries. In Norwich, pot making had died out by about the middle of the twelfth century, and it seems also to have left Ipswich.24 Of the late Saxon urban-based centres in eastern England, only the Stamford and perhaps Lincoln industries survived into the thirteenth century, nor did production begin in Lynn, which was supplied by Grimston, in Boston or in Yarmouth.25 The pattern is not substantially different elsewhere: in Gloucester, some production on a limited scale may have continued, but the major supplier was outside the town, quite probably at Haresfield, some five miles away, where Domesday Book records that there were potters. The only other places where potters are mentioned, Westbury in Wiltshire and Bladon in Oxfordshire, were also rural. All three indicate that several potters were at work, and that the trade had a more substantial value than a mere cottage industry would have yielded.26 Nothing is known of the organisation of these documented potters; their kilns have not been found, probably because they mostly used simple bonfire-hearths which did not require any disturbance of the ground, unlike the up-draught East Anglian kilns. But it is in East Anglia, at Blackborough End, Norfolk, that a clamp-kiln has actually been located, producing only cooking-pots, presumably for very local distribution, and not competing with Grimston for other markets.

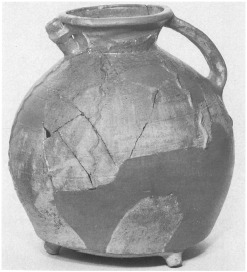

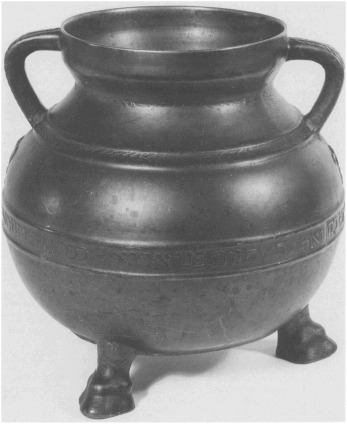

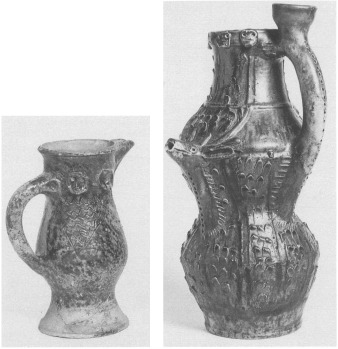

Potters may not have worked at any one place for very long, and many may have been operating, singly or corporately, on an almost transient basis over a wide area, often of woodland: ‘Malvernian ware’ is an example of pottery known from sherds found in Hereford, Gloucester and north to Worcester which are geologically distinctive of the Forest of Malvern area but of which the precise manufacturing sites have not been recognised.27 Access to fuel, clay and water combined with lower rents to make potting a rural craft, despite the advantages to be derived from reducing transport costs of bulky, easily-shattered pots by being sited close to the point of sale in a market town. Another explanation is that concentration on a single market centre was avoided by a rural kiln, able to distribute to several more or less equidistant centres, particularly as more markets were created. Another is that the potters were not able to afford to meet competition for the best locations within those markets, and a peripheral position was worse than one right outside the town altogether. Unlike some other crafts, pottery had no high-status market to serve, as the castle deposits show. This restricted the likelihood that the industry could develop beyond low-level, broadly-based production, since there was no demand for long-distance transport of high-quality pots. Consequently potters could not achieve a high return on their costs, could not afford urban rents and certainly could not accumulate substantial capital for reinvestment. In leaving the towns, pot-making was to some extent anticipating what was to happen to much of the cloth industry in the following century. It is noticeable that a lot of the twelfth-century pottery is coarse and handmade, with little decoration (7, 2). As the urban industries dispersed, so specialist skills were lost and the highest-quality products disappeared. The small scale of most pottery production in the period was typical of peasant industries, in which investment is effectively limited to time and labour rather than to plant, materials and equipment.

There are exceptions to this pattern, such as the continued production at Stamford; the recently-discovered kiln just inside the walls of Canterbury may have been a short-lived attempt by an enterprising Frenchman to produce glazed and other decorated types of vessel not otherwise being made in England.28 Clearly there was no absolute ban on pot production in towns because of fire risk. Doncaster also had a kiln in the town centre for a short while, as well as in a suburb, and Colchester had a suburban kiln in the second half of the twelfth century. Most towns had some available open space even within their walls, such as was utilised by iron-smelters in Norwich.29 Nevertheless, iron-working is another industry which did not establish itself in towns to the extent that might be anticipated. No doubt Gloucester benefited from the iron-working activity in the Forest of Dean by supplying the workers’ everyday needs, but there is no evidence that the proximity of ores led to Gloucester developing as a specialised centre for particular skills and products, although smithing slag has been found in some quantity. Nor did this happen elsewhere: in Stamford, smelting continued, for ore-roasting hearths and slag debris have been found, but it was probably on a smaller scale in the twelfth than in the eleventh century, and no forging by blacksmiths of specialised products has been found.30 Similarly, smelting in Norwich seems to have been a small-scale affair, and there is little evidence from other towns. Also generally lacking in the twelfth century is evidence for other forms of metal-working: crucibles, for instance, are frequently found in the eleventh century but not in the twelfth, although there are exceptions as at Exeter.31 Metal-working was still practised, as copper-alloy buckles, seal-dies and book- and box-fittings show, but direct evidence that these were made in towns is elusive, although Gloucester has yielded a tuyère. Many fewer small, everyday objects are found that date to the twelfth rather than to the thirteenth century, and, it seems, proportionally if not actually fewer than to the eleventh, if the population had grown. The loss by most towns of the right to mint coins would have removed that very important and skilled metal-working craft, perhaps affecting their production ability generally. By the end of Henry II's reign in 1189, only nine towns were still mints.

One urban industry which has been investigated archaeologically is salt production at Nantwich, Cheshire. Here brine springs were channelled to ‘wich houses’, two of which have been excavated (7, 3). In them, the brine was stored in long, narrow clay-lined troughs before being boiled on large hearths in lead pans, the evidence for which was quantities of lead scraps. Relining of the troughs and the stratification show that the houses were maintained in regular use, part of a well-organised industry. There are records of several other ‘wich houses’.32 It seems likely that Nantwich is almost unique in being a place that became urban because of its industrial complexes.

Salt can only be obtained inland at a very few places, but for so long as its production centres could compete with coastal salterns and imported salt, they were in the unusual position of having a product for which there was a high demand at all social levels, and which could not be obtained from a myriad of small-scale suppliers. Nantwich and the other ‘wich’ towns were potentially places where intensive activity could have led to the sort of profits that engender capital growth. The only other medieval industry with that potential was cloth-making, which by the end of the eleventh century had become almost entirely urban-based. Archaeologically this can be shown by the evidence of the horizontal loom (5, 4). The vertical loom did not remain in use in rural areas, for neither loom-weights nor ‘pin-beaters’ are found at village sites in the twelfth century; nor are sunken-featured or other non-agricultural buildings.33 Excavated buildings do not seem to have been large enough to have housed horizontal looms, which would have had to be kept permanently in place. Country people were not therefore making their own cloth, and would have had to be involved in marketing transactions in order to buy it, even if they were making their own clothes. Nor were they able—or they did not need—to augment their incomes by part-time weaving.

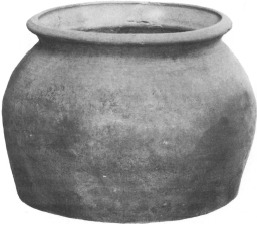

7, 2. Glazed tripod pitcher (left) and unglazed cooking-pot (right) both from Oxford: they are typical of twelfth-century pottery—heavy, much hand-worked even if wheel-turned,

Spindle-whorls have been found at many rural sites, so spinning was taking place, although whether to a commercially significant extent is unknown. There seem to be no reports of metal-working, iron-smelting,34 bone-working or other craft activities from twelfth-century rural sites likely to be of ‘peasant’ status. Without locating kilns, it is not possible to see whether the potters were integrated with the communities that worked the fields on those estates where they are recorded in Domesday, or whether they were virtually full-time specialists, perhaps paid or bond servants of the lord of the manor, taking little part in agriculture. It would seem that most villagers did not have much involvement in anything but farming and basic crop processing, and therefore neither had supplementary support in times of dearth nor freedom of choice in their activities to give them a measure of independence.

Nearly everthing that villagers required apart from home-grown foodstuffs had to be brought in, either by the villagers going to the markets themselves, or by itinerant pedlars. Either way, barter cannot have sufficed for all the necessary transactions, since dealings with outsiders would surely have been possible only with cash. That the villagers had the wherewithal to acquire goods externally is shown in the archaeological record by their pottery, their tools, their whetstones and other items. Most of their buildings seem to have been fairly cheap to build, using techniques such as wooden posts reinforcing earth-material walls, but some longer timbers may have been required for roofs, and these too would often have had to be bought.35 Tax and rent demands would also have forced the countryman into increasing dependence on the market. Documents show that many villages came to have licences for markets of their own: village greens and churchyards could have been used at least informally for limited buying and selling.

and with little decoration. Practical and utilitarian, they seem to express what a peasant could expect from life. (Heights: pitcher 315 mm; cooking-pot 225 mm).

Theoretically, agricultural producers were being squeezed harder and harder by landlords who themselves had to meet growing social pressure to build bigger, to ride better-mounted, to fight with more equipment and to consume more lavishly. The archaeological evidence is not yet really sufficient to see if there are any signs of increased stress on rural dwellers, or whether they could meet the demands placed upon them without undue effect upon their living standards. Such things as village replanning, the closing of churches as at Raunds or their opening on new sites as at Broadfield, Hertfordshire, where a new church displaced existing crofts in the early thirteenth century, may show landlords’ ability to manipulate whole communities, but may sometimes have been as much in villagers’ interests as in lords’. At Wharram Percy, crofts coming into use in the twelfth century may represent in-filling rather than total replanning, but the regularity of their widths suggests more than just piecemeal adjustment. The majority of excavated sites with late eleventh- or twelfth-century use show new areas coming into occupation, but those which, like Goltho, have evidence of formality of layout, have nothing by which to gauge the underlying motivation. The most general conclusion is of expansion of settlement numbers and sizes, indicative of population increase, and of new land development for agriculture, as new sites and dykes in the Fens exemplify.36

7, 3. Isometric reconstruction by R.McNeil of one of the twelfth-century ‘wich’ houses excavated at Nantwich, Cheshire. It has a variety of vats for storing the brine, which was then boiled to extract the salt. This was stored and carried in the conical wicker baskets, known as ‘barrows’. Wooden salt-rakes are shown in one corner.

Some villagers were forcibly evicted from places where the new Cistercian monks wanted privacy, but apart from those well-known examples of landlord manipulation, there are few signs of abandonment or desertion to counter the general picture of growth. The abandoned church at Raunds is probably exceptional, even though there are doubtless others to be located. In general, though, churches were increasing in number and in size, as the Wharram Percy excavation exemplifies. Such growth cannot be a precise index of the growth of a particular community, however, since new building may result from the patronage of a landlord or the benefactions of those who had left the area and done well enough to be able to pay for commemoration at the church where they were baptised.37

The need of a growing number of primary producers to acquire goods is a major factor in the development of the market system that could supply them, and it is probably local demand rather than the needs of long-distance trading that caused the establishment of most of the new towns other than ports after the end of the eleventh century. International trade aimed at the king and aristocracy could indeed by-pass inland towns altogether, with the use of seasonal fairs. Merchants need storehouses, however, and increasingly it is possible to see their investment in substantial headquarters, both in the form of partly or wholly below-ground stone cellars in towns like Oxford and London, and in the two-storey stone houses, with warehouse/shop on the ground floor, and living accommodation above—often with sumptuous fireplaces, chimneys and decorated windows—such as can be seen in Southampton and Lincoln. At the latter, the stone buildings have been attributed to Jewish owners: this cannot always be proven, but certainly they would have had particular need of security because they were dealing in large sums of money.38 The twelfth century saw fairly sophisticated credit arrangements being made, and those involved, whatever their race, would have been rich enough to be very distinct from the rest of the urban community, a distinction physically expressed in the quality of their housing. It may be significant that the two-storey stone houses are almost mirrors of chamber blocks that can be found in castles such as Christchurch, Dorset, and manor complexes such as Boothby Pagnell, Lincolnshire.39 Two inferences might be that the richest merchants saw themselves as on an equal footing socially with rural gentry even though they were not fully integrated into a social system that stressed military service; and that they were creating their equivalent to a landowner's ‘caput’ in the places which they wished to have regarded as their particular territory, the towns. Mercantile enclaves could express their sense of community in this way, as they did in other ways with the attainment of legal privileges; the use of borough seals expressed their new rights.40

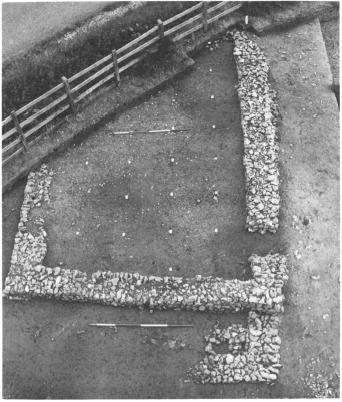

That there were Jewish communities within many English towns is known from documents, but it would be difficult to recognise their presence from normal archaeological evidence, any more than the ‘Frenchmen’ recorded in Domesday Book can be recognised as disparate elements in the towns in which they had settled. Cultural divisions were sharply brought home in York, however, when a cemetery was recognised as Jewish from its northsouth burials.41 Particular burial customs can sometimes identify different ethnic groups even if other archaeological remains do not reveal distinctions that may have been maintained in everyday life. There are occasional Jewish objects, such as the ‘Bodleian bowl’ (7, 4), quite possibly once owned by a Jew in Colchester, a town where two thirteenth-century coin hoards are from properties that may have been Jewish-owned.42 One of these was the largest post-Conquest hoard found in England, with over 10,000 pennies in it, indicative of the very large sums that financiers handled, and of the problems presented by the physical scale of such quantities of coins.

Hoards like those from Colchester make an uneasy contrast to the numbers of coins found as accidental losses on excavation sites; St Peter's Street, Northampton, yielded two twelfth-century pennies but only a single thirteenth-century halfpenny; the same town's Marefair site had one twelfth-century farthing and one thirteenth-century penny; all the 1960s work in Winchester produced but six twelfth-century and twenty-two thirteenth-century coins, excluding those deliberately hidden in small hoards; York has seven twelfth-and about thirty thirteenth-century coins, nineteen of the latter being of Edward I's reign when the king was using the city as the base for his Scots-Hammering expeditions.43 The Colchester hoards indicate that the stray losses represent only a tiny proportion of what was circulating, which is borne out towards the end of the thirteenth century by surviving mint records which show that millions of coins were issued.

That financiers flourished is scarcely surprising when the amount of late eleventh- and twelfth-century building is considered: St Peter's, Gloucester, is only one example of many Norman projects, and there were new ecclesiastical orders such as the Cistercians to be accommodated. The increasing cost of castles has already been mentioned. Building stone was brought from quarries such as Caen despite the distance and costs of transport involved. Blue slate from Devon found in south-east England is a good example of the importance of water transport.44 Documentation is not as full as it is for later centuries, but it seems likely that then as subsequently there was little hesitation in borrowing money for repayment from anticipated incomes. Although usury was forbidden to Christians because the Church would not countenance lending for profit by interest, since humans should not gain wealth through manipulation of God-created time,45 a merchant could ‘lend’ money by paying in advance for next year's crop— a motive, perhaps, for the trend to demesne farming rather than leasing which characterised the practice of Church and other landowners in the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and which could account for some of the reorganisation of villages and fields that took place.

7, 4. The Bodleian bowl. This handsome cast copper-alloy tripod vessel has a Jewish inscription round it which states that it was ‘The gift of Joseph, son of the holy Rabbi Yehiel’. He was a Talmudic scholar in thirteenth-century Paris, where the bowl may have been made. His sons had associations with Colchester.

The rôle of the Church in forming the social pattern of medieval England— by insisting upon monogamy, for instance—is only very indirectly recognisable in physical evidence of this sort. Rural crofts certainly seem best suited to a linear family pattern: the equally-spaced units at Wharram Percy indicate little deviation from a standard unit of accommodation that seems designed for a small number of occupants such as parents and children. The plot which contained them was physically separated from its neighbours, implying little extra-family interaction at a close physical level. The ditches that have been found at a number of sites dividing thirteenth-century villagers from their neighbours may be more satisfactorily explained by such cultural factors than by seeing them as a response to wetter weather, as is sometimes suggested. There is a little evidence that winter rainfall was increasing from about the middle of the twelfth century, but it was compensated for by dry summers until the end of the thirteenth. It does not seem likely that damper conditions would have been clearly enough perceived for drainage ditches or other physical developments such as raised tofts and stone foundations for buildings to have been an inevitable response.46

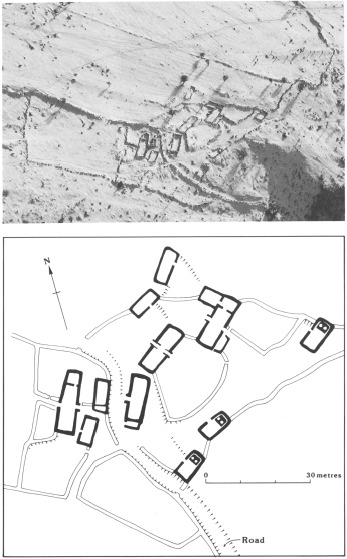

There are excavated rural sites where the neat ladder-like arrangement of Wharram Percy was not emulated. Thirteenth-century Hound Tor, for instance, has groups of stone buildings which suggest at least three farming units (7, 5); its more informal arrangement may result from the less rigid manorial control likely to have been exercised in more peripheral areas.47 The largest house has an enclosed garden space attached to it, within which are two smaller buildings, perhaps barns. But both had hearths, and one had a cooking-pit, and it is suggested that for a time each was lived in by someone who was a dependent of the main house, a servant, a grandparent or a son. Upton,

Opposite: 7, 5. The thirteenth-/early fourteenth-century stone buildings at Houndtor, Devon. The plan has been redrawn by S.E.James from the original by G.Beresford so as to be oriented with the aerial photograph taken by F.M.Griffith on March 17, 1985, when there was a light covering of snow on the ground. The settlement had four long-houses, all with down-slope byre ends. Smaller buildings were also used as houses, at least intermittently. Grain-driers were built into three of them. Garden plots and small fields can also be distinguished. Ridge and furrow behind the buildings is probably not a vestige of medieval ploughing, but rather from an early nineteenth-century phase of intensive land use.

Gloucestershire, has produced another possible example. But in these cases the sub-division seems to have been only temporary. Permanent reduction of property sizes might be expected in areas where partible inheritance was regularly practised, and where manorialisation was less rigid. It would be useful to have excavation results from areas such as Kent and Suffolk where partibility is recorded, to see whether it made any real difference, but it could never be easy to ascribe differences between sites to such causes, rather than to differences in farming regimes, local availability of particular commodities and regional wealth levels.

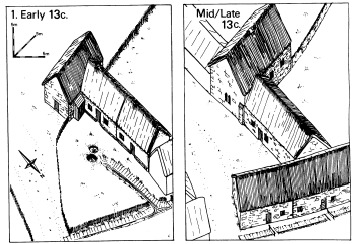

It is more possible to discuss such possibilities for the thirteenth than for the twelfth century, not least because of the adoption almost everywhere of the use of low stone walls or at least pad-stones upon which to construct timber or earth-material houses, as these leave more distinct traces in the ground (7, 6). They do not necessarily indicate more investment in building, as most areas have readily available stone which may not be suitable for masonry building, although perfectly adequate for unmortared foundations: but the change would have made such investment worthwhile, as raised timbers were much less prone to rot and so made the construction of permanent housing more viable. Putting up a properly framed timber construction could be a considerable expense, not only because lengths of wood were needed greater than could be foraged from the local hedgerow, but also because cutting the joints and erecting the frame was skilled work for which a carpenter would have had to be employed. Farmhouses and similar structures begin to survive from the later thirteenth century, becoming relatively common in the fourteenth: it may well be that they were already being widely built by those fairly low in the social hierarchy in the early part of the thirteenth as well, enabling them to present a better face to the world.48

The late twelfth and thirteenth centuries were years when other material consumption by agriculturalists seems to have increased, with a wider range of goods reaching them. Most rural sites have yielded a scatter of decorated items, not spectacular, but enough to suggest a spending power beyond the barest necessities. The range of finds from Goltho, Lincolnshire, is typical: horse harness pendants, belt fittings, a finger-ring and other copper-alloy trivia. Seacourt, near Oxford, has a very similar range, except for a fragment of gilded glass from the Mediterranean, an exotic piece which may have been brought back by a returning crusader or pilgrim from the Holy Land.49 Did it reach Seacourt already broken, but still an object of wonder, like the porcelain fragments that are found in the slaves’ quarters of the American Plantations many centuries later?50 The objects show that peasants were not restricted in their daily lives to what they could make themselves, and it does seem that some at least were able to indulge in small luxuries. Documentary evidence shows that there was a very wide range of income and of amounts of land held, but the different internal social levels that must have existed in most villages are scarcely traceable in the archaeological record. This is partly because rubbish was not generally buried in pits but was carted away to be spread as manure. Consequently differences in standards of living cannot be fully explored through analysis of what was discarded on different crofts, although they were so carefully separated by hedges, fences and ditches. It does seem contradictory, however, that there should be such similarity in the sizes of the crofts and of the buildings that they contained, if peasants varied so much in their potential purchasing power. It is as though social and economic status was not expressed in material terms. There is also a very limited range of tools found on excavation sites,51 an indication that ‘division of labour’ was limited by there being little specialist craftwork: tools and the people using them were multi-purpose.

7, 6. A fourteenth-century building at Popham, Hampshire, excavated by P.J.Fasham before its destruction by a motorway. Carefully constructed of flints, the walls were the footings for a timber-framed—or possibly earth-walled—superstructure. In the bottom right hand corner are the remains of an earlier building, on a different alignment from its successor.

Despite the general absence of pits, there are enough deposits to reveal such things as sea-fish bones at Wharram Percy, which show that food was not entirely restricted to what was locally available. Coastal midden sites such as Braunton Burrows in Devon suggest collection and processing of mussels, oysters and shell-fish on a very large scale,52 and mollusc shells in towns as far from the sea as Oxford show what was available. Peasants’ gardens would also have given them some variation from total reliance upon what the common fields and their limited rights to forage yielded.

It is just possible that the thirteenth century did see at least a few villages becoming directly involved in activities other than agricultural production. Pottery-making, for instance, has not yet been found as an integral part of any twelfth-century agricultural settlement, nor do wasters suggest that it will be. Thirteenth-century Lyveden, Northamptonshire, on the other hand, had kilns scattered amongst the the crofts, as did other places in that county and in neighbouring Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire.53 It is as though a peripatetic, woodland craft was becoming permanently based at particular centres. Such sedentarism would partly have been the result of assarting (the clearance of scrub and woodland for fields) and the amount of woodland available. It would also have fostered the use of more permanent plant such as below-ground kilns instead of bonfires, if the market demand from a larger population was big enough to justify production of larger numbers of vessels in a single batch. Greater control of the firing would produce a more uniform vessel. By the end of the twelfth century, the most distinctive regional variations in pottery, such as the Cornish grass-marked wares or the Thetford-type wares of eastern England, had already gone, but there was still a wide local variety in jug and cooking-pot shapes which was much less noticeable by the end of the thirteenth. The social position of the potters was not uniform, however. Isolated kilns such as at Mill Green in Essex or Nash Hill in Wiltshire perhaps suggest potters—and, at the latter also for a time floor-tile makers—less integrated with the communities around them than those at Lyveden and elsewhere.54

Although rural cloth-making is a recorded thirteenth-century development, most excavations have provided thirteenth-century evidence only of agricultural buildings and activities. It seems at present that rural industries generally are more likely to have soaked up surplus wage-labour resulting from population growth than to have provided a supplementary source of income for ambitious small-holders. At Lyveden, however, pot-making tenements reverted to agricultural use and vice versa, as though there potting was an occupation pursued only intermittently by any particular family, and on one croft bone-working may have been a cottage industry. Despite documentary evidence, evidence of brewing is everywhere infrequent.55

That there was surplus labour in the countryside seems likely not just from the continued growth of towns, which normally are too unhealthy to sustain their populations but have to be supplemented from outside if they are even to remain stable, but also by places which came into use in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Some were expansions of existing sites, like the house recently excavated at Foxcotte, Hampshire; others were single farms probably resulting from assarting, as at Hartfield in Sussex, typical of Wealden expansion.56 It is impossible to quantify, but there may be justification for an argument that growth was more rapid in the thirteenth than in the twelfth century. This would be consistent with documentary evidence from those few places such as Taunton, Somerset, where it exists, even if the details of increase in such records may owe as much to improved manorial accounting as to an actual increase in numbers.

Population growth could in theory have reached a point where a mass market became more significant than one in which king and aristocracy dominated commerce. That this did not happen was partly because of their ability to maintain social control, not least because the limitations of agricultural production tied small-holders to the land. Even in the most fertile and efficiently farmed parts of eastern England, there is little sign of significant social change, although new crops, applications of more fertiliser and use of better-harnessed horses to plough more quickly allowed more to be produced. Other developments speeded processing, such as the use of windmills, recognisable from the cross-timbers laid in the ground at sites like Ocklynge Hill, Sussex, to augment watermills.57 Windmills required the use of very substantial timbers, and were therefore expensive. Their importance should not be overemphasized, for they did not allow large areas to develop for grain-growing which had previously only been used for grazing. Whether any were built communally is not known, but seems unlikely from the number that are recorded as a landowner's investment. Similarly, watermills seem to have passed back into lords’ direct control on estates where in the twelfth century they had been rented out, or even separately owned, and this represented a loss to rural communities of the opportunity for self-improvement that becoming a miller could offer to a peasant. Field evidence of water channels and pools for textile processing found in the north-west can similarly be associated with landlords’ rather than peasants’ initiatives.58

A lord's profit from milling came partly from saving on labour in the grinding of his own grain, if this was a cost to him, but probably more from his tenants if he could insist that they brought their grain to his mill, upon which he could levy a toll. Establishment of this by ‘social control’ exercised ultimately through legal control of conditions of land tenure was one cause of tension between peasant and lord, forcing the former to surrender more of his product to the latter. The extent to which it was often a real burden, as opposed to a visibly symbolic one because of the mill's constant presence, may be wondered. Similarly, prohibitions on hand querns may have been as much for symbolic as for real economic reasons, since they are sufficiently common finds on rural sites for it to be clear that the bans were not rigidly enforced— although it would be interesting to know if their incidence is less in the thirteenth than in the twelfth century. Mills provide a good example, however, of a landlord's coercive powers and economic interest in tenants’ farming and other activities. It could have been lords’ reluctance to see their peasantry becoming involved in non-agricultural activities, from which there were less well-established ways of extracting a substantial proportion of their output, that meant that relatively few villages can be seen to have taken advantage of the possibilities that pot-making and so on provided.

Without gears and pulleys, the actual power output of mills was not great— not enough to heat a modern electric kettle, apparently!59 The vertical wheels at sites like Bordesley Abbey, Worcestershire, were more powerful than the horizontal wheel at Tamworth had been, and there is evidence there of gearing. At Abbotsbury, Dorset, in the fourteenth century, the mill was terraced into a hillslope and the water was fed by a wooden chute onto the top of the wheel, a technique which makes much more effective use of the power source. Such technology was worth applying to agricultural bulk products, but in the cloth industry, for fulling, its advantages were probably more marginal: the two thirteenth-century fulling tubs recently found at Fountains Abbey, Yorkshire, were less than two metres in diameter, yet are likely to have been as large as any.60 This does not suggest a huge output achieving significant economies of scale, especially when labour to perform the same operation by foot-trampling was cheap. Thirteenth-century fulling-mills were a factor drawing cloth-making out of towns and into rural areas, but they were probably less of a factor than the decline in demand for high-quality urban products in the face of Flemish competition. Providing water supplies for such mills often involved creating dams and diverting rivers and streams as at Bordesley; engineering by sheer physical effort was often on a very large scale, just as new river channels and massive sea-walls in marsh-land areas also necessitated big labour forces for construction and maintenance.

That Fountains Abbey should have had a fulling-mill is not necessarily an indication that the monks were involved in selling as well as making cloth: the scale of the operation does not imply that output was other than for the community's exclusive use—to save them, in fact, from buying in and thus actively fostering the open market. In this way, abbeys and other religious organisations could restrict the economy at least as much as they could cause it to develop. Fountains was a Cistercian order, dedicated to isolation, and thus one which would deliberately keep physical contact with commerce at a distance. Other houses, like St Peter's at Gloucester, were probably having more dealings with local suppliers. Nevertheless, the thirteenth-century husbandry manuals and so on emphasised that good management meant self-sufficiency.

Watermill sites are elusive; Bordesley's is the best known, with sluice-controlled leats, wattle-lined and subsequently boxed in with massive oak planks, and oak wheels. Metal-working debris associated with this complex suggests that it was a smithy, wheels being used for the bellows. Whether its products were sold to boost the abbey's income rather than made merely to limit its need to buy-in metal objects is unknown. Apart from monastic sites, however, the only iron-producing evidence is of small-scale operations which need have involved no more than the supply of a manor's own requirements; the only excavated thirteenth-century smelting complex, Alsted in Surrey, was also a smithy, and was within the confines of a manor. Its technology was so simple that its bloomery hearth was below ground level; slag could not be tapped off so the whole furnace had to cool before the ‘bloom’ could be removed. No water sources provided power to increase production. A similarly low-key operation is suggested by sites located in forested areas in Northamptonshire, where one excavated furnace at Waterley measured only some 400×200 millimetres. Again, there is no suggestion that water power was used, to turn wheels operating hammers to break up the ore before roasting or bellows to intensify heat in the furnaces. Nor is use of water power likely at all the Wealden production sites located by spreads of bloomery slag, although used at Chingley, Sussex, probably for hammering. The blast furnace, although used in Sweden, was not introduced to England until the end of the fifteenth century.61

A major factor limiting the development of a large-scale iron industry was the quality of English ores; even the best, like those in the Forest of Dean, required a lot of time and fuel-consuming work to remove phosphorus and other impurities. For hardness they were all right, but the iron was too brittle: much better ores, with more steel-like qualities, were available from abroad, notably Spain as well as Sweden. English ores could be mixed with imports to produce serviceable goods, and analyses of knife-blades have shown that smiths were adept both at ‘piling’ the ores to produce a homogeneous bar and at welding steel-quality strips onto cheaper iron cores.62 Since ordinary ores seem to have been about a fifth of the price of the best imports, it was obviously efficient to combine the two in this way. Consequently, English ores were not simply priced out of the market. What mattered more was the size of that market; if monasteries and manors preferred to produce their own iron, using their own labour, the external producer could only look to towns and rural settlements with their limited needs. Nor did royal demand make up for the deficiency: when the king planned an expedition to France in 1242, he demanded 8,000 horseshoes and 20,000 nails from the archbishop of Canterbury, who, because of his estates in the Weald, was best able to supply them. This order would have required perhaps 3,000 lb of iron; a bloomery furnace can produce some thirty lb per firing (an estimate for the Stamford furnaces suggests seventy-five lb). Consequently six furnaces working on a twenty-four hour cycle would have supplied the whole lot in eighteen days. These estimates are very inexact, but they are useful because they show how little the efforts and quantities involved in meeting what was an exceptionally large order by the standards of its day actually were. Supplying medieval armies might make an individual armourer wealthy, but it would not support a large-scale armaments industry even when payments were offered, and thus would not act as a sufficient catalyst to raise an industry to the point where investment in technology was worthwhile.

Another industry which may have established itself in the Weald in the thirteenth century is glass-making, although the earliest known furnace is fourteenth century.63 English glass production was limited by poor-quality sands, but Near Eastern and Italian imports at Southampton, Boston, Nottingham and Reigate64 show a demand for vessels as well as for window glass, and these are not from the high-status sites such as castles and palaces where they might most be expected to occur. They may be merchants’ status symbols, not imported to sell as trade goods, but even so they show considerable demand for such luxury items.

Something of the same increase in demand for more than the most basic commodities can be seen in pottery. Most obviously, the proportion of glazed wares recovered from rubbish pits and other contexts becomes greater. Bulbous tripod pitchers (7, 2) were generally supplanted by taller, more slender jugs, usually wheel-made; colour contrasts were achieved by applying different clays to the surfaces, and copper filings might be sprinkled on to give a mottled effect. Just as Stamford ware in the late ninth century could be seen to be strongly influenced by overseas products, so too in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries imports from Rouen in Normandy, and subsequently from the Saintonge areas of Gascony, affected the English decorated wares. The actual number of vessels of the former imported was not high—even in London, it represents only 2 per cent or less of the total of pottery found—and sherds from them are almost entirely found in ports, so they were not being traded inland: nevertheless, they were copied in London and elsewhere in a way never attempted of such twelfth-century imports as Rhenish ‘Blue-grey’ handled bowls or red-painted wares. Also copied were high-quality metal table wares, most strikingly the water jugs in the shapes of animals and mounted men, known as ‘aquamaniles’, of which there were pottery equivalents in London by the mid thirteenth century. Many of these were produced in Scarborough, and their coastal distribution around the east coast and as far south as Sussex suggests that there was a wide demand for them. Some could have reached their final breaking-places as gifts, others as the chattels of peripatetic noble households, but there are enough of them to suggest at least some intermittent trade, even if only as make-weights with other cargoes such as coal. Other highly elaborate jugs include puzzle jugs (7, 7), an insight into medieval humour, and many with moulded figures, animals and human faces. Imports of ‘polychrome’ Saintonge wares are sufficiently often found at castle sites as to suggest that by the end of the thirteenth century that particular type of pottery was, perhaps uniquely, being used at the tables of those of the highest status, and by few others except wealthy merchants in ports and occasional inland houses. Although there is a single sherd at Wharram Percy, it was not normally bought by rural dwellers, and almost certainly not by poorer townsmen, since there is not enough of it in urban rubbish pits to suggest regular shipments for sale to a wide market. English potters tried to copy it (7, 7), not very successfully, as they could not achieve the necessary quality of clay.65

7, 7. Two late thirteenth-/early fourteenth-century Oxford jugs. The smaller one, on the left, is English, but in shape and decoration imitates contemporary imports from south-west France. The elaborate ‘puzzle’ jug, also English, has two separate compartments, the lower filled through the hollow handle. The stag's head is its spout: so an unwary drinker gets drenched when he tips up the jug—an insight into peasant humour. The elaboration of these vessels contrasts with the earlier tripod pitcher (7, 2) and suggests that many people already had a little more spending money. (Heights: 205 mm and (puzzle jug) 330 mm).

The scale of operation of many English potters was probably increasing: a single order for the royal castle at Winchester to the potters fifteen miles away at Laverstock, outside Salisbury, Wiltshire, was for 1,000 pitchers. They only cost the king twenty-five shillings, however, including transport. Laverstock had another royal palace to supply, nearby at Clarendon, as well as the marketplace in Salisbury and other towns in the area. Few of their products have actually been reported from Winchester, however, despite the orders from the castle. Even over that distance, they may not have been competitive. This seems to be fairly typical of known inland kilns: they could dominate a few local markets, but not achieve long-distance distribution. Constraint by toll charges may be shown at Bedford, where the pottery found north and south of the river crossing comes from different supply sources. By such restraints was the potters’ capacity to expand limited.66 One useful rôle of pottery studies is to show that many villagers were not dependent on a single supplier for their pots, since sherds from different kilns are usually found. This may well mean that peasants and potters frequented more than one marketplace. In the few cases where a particular pot-making centre did manage to exclude virtually all competition from its nearest market, as Grimston succeeded in doing at Lynn, its coastal location may have meant that it had some export capacity, giving it a price advantage because of the scale of its production.

Although glazed jugs were getting into the countryside, the most highly decorated, and consequently presumably the most expensive, are proportionally less likely to occur there than in towns. The village site at Goltho produced two recognisable face-jug sherds and a few others with dots, pellets or horseshoes; Barton Blount, Derbyshire, did not produce any, nor did Seacourt, and such results seem typical. Nevertheless the preponderance of cooking-pots at these places may occur because they were much more prone to breakage, especially when used on open hearths. The assemblage from a thirteenth-century long-house at Dinna Clerks on Dartmoor is instructive, because the building seems to have been destroyed by fire and no-one bothered to retrieve its contents, which included a penny of the 1250s. There were five cooking-pots, a glazed jug and two charred wooden dishes around its hearth, but in an inner room were a cistern, two more jugs and another cooking-pot. So the ceramic assemblage actually in use had a much higher ratio of jugs to cooking-pots than a normal rubbish deposit contains.67

Did ordinary townspeople have any material advantage over their country cousins? That the wealthy could prosper is shown by the stone houses, but it is not so easy to gauge the access to high-quality goods of the artisans, nor to be sure of their housing conditions. Sites such as St Peter's Street, Northampton, have substantial stone-founded buildings replacing timber, though not on all the tenements, but few towns have yet produced evidence from their central areas to give a clear idea of the different types of dwelling to be found in them in the thirteenth century. Less intensive redevelopment in subsequent centuries may mean that peripheral and suburban zones can be expected to produce more complete evidence, although so far few towns have yielded what might be widely anticipated, the one and two-roomed, probably single-storey clay-walled houses found in fourteenth-century levels in Norwich.68 In the Hamel, Oxford's west suburb, tenements were laid out at the turn of the twelfth and thirteenth century (7, 8). This site was near the floodplain of the River Thames on meadows which had been drained by ditches, one of which provided the boundary line for one of the new tenements. Although laid out in a single operation, the tenements were built on piecemeal. Stone seems to have been used at least for the foundations of all the buildings. Some of the different properties were joined together, suggesting terraced housing. Contiguous structures were not novel, of course, but the use of terracing may have been, suggesting maximum use of the available space, and a type of building particularly appropriate for towns. During the middle of the thirteenth century, there was also a much more substantial house in the Hamel, with walls a metre thick, clearly the property of someone wealthier than his neighbours. A seal owned by ‘Adam the Chaplain’ came from this tenement.69

Intermingling of social groups in towns meant that their rubbish became intermingled in the pits where much of it ended up, so that it is difficult to establish the extent to which the better foods and artefacts were the preserves of the wealthy. Nor is this problem helped by the friars, whose arrival in many towns in the thirteenth century brought a new factor into the urban community. Although they were supposed to espouse poverty, it is fairly clear from the sites of their houses in Oxford and Leicester that expenditure was more than basic, both in the scale of the building of their churches and in the food that they ate. The Dominicans at Oxford, despite being so far from the sea, were acquiring quantities of fish such as herring, cod and haddock, which may have been dried or salted, not fresh, and more than one sturgeon graced their tables over the years. Their Austin counterparts at Leicester were also acquiring such things, with large quantities of marine shell-fish being consumed, which can only have been eaten while fresh.70

7, 8. Two phases at The Hamel, a suburban site in Oxford excavated by N.Palmer. Initially a terrace of buildings, the site was redeveloped intensifying occupation and creating a built-up street frontage. The presence of a more substantial house amongst the cottages shows the social ‘mix’ in the area.

It is possible to be reasonably certain that the fish in the pits and other contexts at the Oxford and Leicester friaries were actually consumed there because both sites were outside the towns, and it is not very likely therefore that their rubbish would have become mixed with others’ to any great extent. Such exclusivity is unusual, however, for many friaries were intra-mural, as in Lincoln or Southampton, probably because powerful patrons were able to find them enough space, at least away from the main streets. This sort of patronage means that the location of friaries cannot be taken as a precise measure of a town's prosperity and consequent rent levels. They do, however, give some indication of which towns were considered the largest and most in need of the mendicants’ missions.

Other measures of towns’ thirteenth-century importance include their walls and gates, and the efforts that many put into maintaining and improving their streets and trading facilities. Particularly visible in archaeology are the quays and wharfs which have been found at a number of towns from the thirteenth century onwards, largely because the lower parts of their timbers are waterlogged. In London, where the process of reclamation and improvement to the river frontage began earlier than elsewhere, the quays were not a municipal effort, uniformly constructed along the Thames, but seem to have been the initiatives of holders of narrow plots along the river bank, each having to compensate for what his neighbour had done, since each new extension into the water would cause the next-door stretch to silt up and lose its access.71 The investment in these structures was not usually enormous, for the timbers did not have to be of great length: what they show is the need for new sorts of harbour facilities, with boats that were not simply unloaded onto a mud flat or shelving hard, with the risk of getting the cargo wet. Thirteenth-century seals indicate the use of high-sided capacious ships with a single main mast, relatively slow but reliable, and not requiring a very large crew. They needed to be able to ride in the water at quay-sides for unloading, or to anchor in mid-channel and use lighters. A good harbour was one where they did not have to lose time waiting for the high tide before they sailed, but as they were bulk carriers of wool, cloth, wine and other goods speed of delivery was not essential. But they were still quite small: the early fourteenth-century wine fleet needed a thousand ships to carry 72,700 barrels, an average load of c. 250 tons.72

Ships were expensive to buy, and to operate even with small crews. Investment in them had to be justified by efficient use; the provision of lighthouses is one way in which increased concern for safe navigation can be recognised.73 Ports like London had to offer repair services as well as harbour and storage facilities. Financial expertise also developed as a result of shipping investments and transaction facilities had to be available. Consequently commercial activity increasingly concentrated at a few large ports rather than at a network of small harbours: ‘beach markets’, whether a Bantham or a Lynn, were no longer sufficient. Bigger ships were a reason for the decline of the river navigations, and several coastal places first mentioned late in the twelfth century grew to displace older-established ports, as Poole in Dorset did Wareham. At Portsmouth, Hampshire, traces of buildings close to the shore line attest the first use of the site soon after its foundation in the late twelfth century; a solidly-built timber-lined cistern dug to hold fresh water presumably partly supplied ships’ water barrels.74 Inland towns on river navigations were further affected by increased use of mills and fish-weirs, traces of which have been located in Nottinghamshire, for instance, which impeded the passage of boats:75 rubbish dumping was another problem. Oxford and Lincoln are two towns whose trade may have suffered as much from this as from the recorded decline of their cloth industries, although loss of navigation may itself have been a cause of that decline.76 Any problems that towns like these were facing are very difficult to establish from their archaeology. General commerce was sufficient to keep Oxford, for instance, buoyant, as the Hamel excavations show. No abandonments of property have been found, which would be the ultimate demonstration that a town was in difficulties. It must not be assumed, however, that walls and quays are necessarily a sign that a town was thriving; they might just as well have been built in a desperate attempt to keep up appearances or to win back lost trade.

Keeping up appearances may have been becoming more important after the middle of the twelfth century. Certainly high-cost items such as jewellery were increasingly evident. The simple twisted rings of the tenth and eleventh centuries passed out of use in the twelfth. New ring-wearing fashions appeared, partly under Church influence, because each priest had a gold ring set with a stone appropriate to his rank, semi-precious sapphires, garnets, turquoises and so on, each of which was considered to be endowed with special properties—to detect poison, to preserve the wearer from sudden death, or even to help an escape from prison. Neither the goldwork nor the quality of the stones are particularly impressive, but they are found in some number, often in ecclesiastics’ graves, like that of Archbishop Walter de Gray of York. Secular usage, or at least import by a merchant if not for his own use, is demonstrated by a ring set with garnets found in a late twelfth-century pit in Southampton. Brooches were also changing, with ring-brooches coming into fashion, often set with stones like the finger-rings and with amorous or devotional inscriptions.77 These things suggest more decorous behaviour and more courtly display as the well-to-do played out a subtler comedy of manners. Henry III was criticised in the middle of the thirteenth century for not acting his part by handing out festive dresses and costly jewels. Finds from Exeter and other towns show that those with shallower purses might have copper-alloy imitations set with glass or pastes: like the contemporary pottery, such copies suggest a unity of culture, divided not so much by birth as by wealth. To argue this is to argue that the rigid caste divisions of feudalism, dominated by inheritance and military service, were to some degree being broken down.

Concomitant with such social changes were changing ways of managing social relations, and the twelfth century is notable for the increased rôle that legislation and government administration played. The use of the abacus may not be attested archaeologically but the importance of legal processes is certainly shown by the increased numbers of seal-dies that are found. Even the poor had to have a personal seal with which to demonstrate their witness to documents: many of the cheapest dies were probably cut in lead and are occasionally found, as recently in Norwich, but copper-alloy seal-rings become quite frequent and probably exemplify the equivalent of Adam the Chaplain's well-cut handled die found at the Hamel.78 Such seals are one way in which an increasing sense of a person as an individual was expressed. The late twelfth-century development of individual tomb effigies is another, at least for the highest ranks. There is an increase in memorial slabs generally, many carved with symbols like shears which seem to be indicators of professions.79 Not only finger-rings, but also pewter chalices and patens were placed in priests’ graves; it is as though these were ways of marking an individual's tomb, distinguishing its occupant from the anonymity of the mass cemetery.

Class distinctions became more important as they became even more prominently displayed. Class barriers could be crossed by the successful: an example is the Ludlow merchant Laurence's purchase of Stokesay Castle in 1281. The aim of acquiring wealth was to spend it, not to use it to accrue even more of it, and lavish expenditure included consumption of exotic foreign foods such as figs, the seeds of which are occasionally found, as well as elaborate display. The aim was to demonstrate the distance between those who could afford luxuries and those who could not, just as Laurence de Ludlow distanced himself physically from his fellow townsmen by buying his country property. It is distancing of this sort which probably accounts for many of the topographical changes in the countryside that mark the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries. At Goltho, for instance, the castle was abandoned, and its owners probably moved to a new site which took them half a mile away from their villagers.80 Sometimes such abandonments may be for tenurial reasons: it is not unreasonable to link the demolition of the substantial stone structure at Wharram Percy in the thirteenth century to the sale of their manor there by the Chamberlain family in 1254.81 Excavations are increasingly showing that moated sites came into use at this time, partly perhaps because of legal and economic prohibitions on castle building: a moat gave an echo of a castle without being seriously defensive, although some owners acquired licenses if they wanted something really big. A few moated sites, such as Milton, Hampshire, a late example, seem to have been laid out over existing peasant houses: more often it was the gentry who moved—at any rate, most of those excavated are either on previously unoccupied land, or overlie occupation that is as likely to come from a previous manor house as from some other building on the site. Not all moats were the property of gentry owners: sheer numbers in East Anglia suggest the work of better-off tenants. Many are in areas only recently brought into cultivation. As their numbers increased, no doubt their status claims declined, but they seem to have been part of a process which allowed a wider social stratum to proclaim its pretensions.82

At the same time as this process by which relative isolation in tight-knit enclaves was achieved by the wealthy was a tendency for their buildings to be conglomerated: instead of the separate halls, kitchens, sleeping-quarters and chapels of a site like Cheddar, a single building typically consisted of private apartments at one end of a hall, and service rooms at the other.83 The great keeps in castles had perforce brought these together, but inconveniently: the new palaces and manor houses combined access and comfort, giving the owner accommodation separate from his servants, but also retaining the great hall in which he entertained and gave display to his gentility: private and public needs were satisfied.

By the end of the thirteenth century, housing at most social levels made this same fundamental provision for a central hall flanked by rooms used for other purposes. On Dartmoor and widely across England on higher ground, the long-house was one variation of it: the largest stone houses at Hound Tor (7, 5) were of this type, each with a centrally placed entrance leading on one side into the hall, identifiable by its hearth, with access from it into a small inner room, and on the other side into a byre for livestock, often identifiable by a drain. Apart from a porch, a feature added to some of the Hound Tor houses during their period of use, this rectangular plan was generally used, and its adoption was probably one reason for the use in southern central, northern and western England of cruck construction, in which pairs of curved timbers along the length of the building gave substantial but flexible accommodation that allowed one end to be used, if required, for winter shelter of animals, perhaps with a loft space above; an open central hall, which might be two bays long if it could be afforded; and perhaps an end room to give further living and storage space. Radiocarbon and dendrochronology date the earliest surviving structures of this sort to the later part of the thirteenth century.84

Rectangularity of plan was not something that peasants would have observed on their visits to their landlord's manor house, where the end-blocks were usually at right angles to the hall and did not share its roof-line; it was the internal arrangement of the space that mattered. In areas where the cruck was not used, similar spatial provision was made. In Kent, for example, the types of joint used in its construction allow a thirteenth-century attribution to a house in Petham, which had an aisled hall and two end-rooms, its hipped roof showing that it had not had a full upper storey.85 It may have been in order to provide first-floor space in such end-blocks that the ‘Wealden’ house and variations upon it came to be widely used in south-east England. All seem most suited to two- or temporarily three-generation nuclear family occupation, each house doing its own food preparation and so on without dependence upon outside support of the sort that a kin-group might provide. In towns, too, something of the same sort had come into use by the early fourteenth century, when the earliest surving ‘burgess’ housing is found, as at 58 French Street, Southampton. There, above a stone cellar which had its own separate access, there was provision for a shop on the street frontage, with a room above it, and a side passage which led into a central, open hall beyond which was another two-storey block. Kitchens, for safety reasons, often remained physically separate.86 Similar plans characterise Chester's famous Rows, for which late thirteenth- and early fourteenth-century dates are now being obtained by dendrochronology.87 Poorer townspeople had to be content with one- or two-roomed cottages, as in Norwich, or with terraced housing as in Oxford's Hamel (7, 8), and there may have been poorly-built cots on the edges of hamlets and villages too, but the evidence of excavations is that the normal unit was rather better.