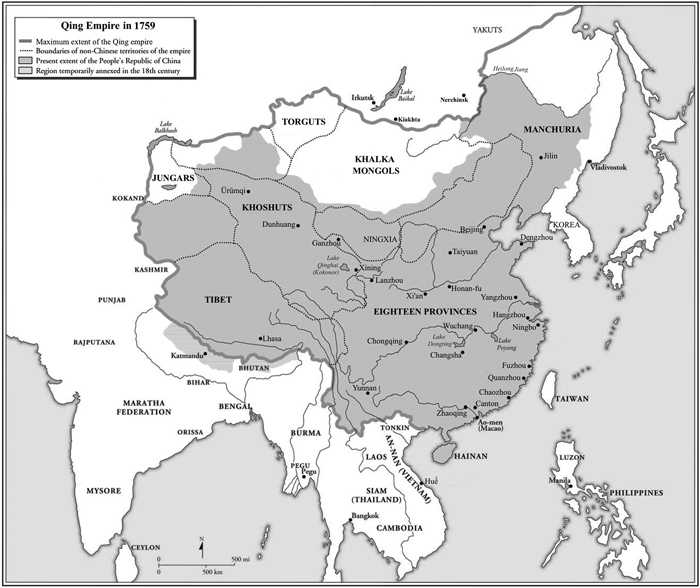

On April 25, 1644, the Ming emperor Zhu Youjian sought to evade capture by the rebel peasant army that had seized control of Beijing by taking his own life. Loyalists of his dynasty would continue to hold out in southern China for another four decades, but in the north the Ming Empire ended with this act of self-destruction. A new dynasty known as the Qing, erstwhile Jurchen clients of the Ming on their northeastern frontiers, moved quickly to fill the vacuum. The new rulers were not content merely to inherit the old, Han-centric Ming Empire, but sought instead to incorporate the Han into a new multiethnic state that—as under the Yuan—was ruled by a non-Han and enthusiastically expansionist elite. This chapter will cover the rise and consolidation of the new Qing Empire, from the efforts of Nurhaci (r. 1583–1626) to weld the seminomadic Jurchen into a coherent state to the apogee of Qing power under the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–95), by which point the dynasty had come to rule over a geographical expanse more than twice the size of Ming China (Figure 3.1).1

This chapter seeks in particular to examine the Qing dynasty’s ability to push consistently, through each expansion, the limits of empire.2 Each time the Qing conquered a new people and territory, be it Taiwan or the Jungar Mongols, they tested their own empire-building skills. Particularly at the frontiers of empires, control over new subjects consisted of a reciprocal accommodation, as those old and new to Qing rule reinterpreted the empire’s concept of sovereignty. Key themes of the chapter will therefore be the limits of imperial expansion, the fault lines of ethnic and cultural difference, the balance of centralization versus decentralization, and the management of Qing relations with other polities along their empire’s frontiers.3

A final theme within this chapter is the effects of frontier expansion. What happened when empires collided with each other and had to reconcile their expansionist aspirations with the need for clear and durable borders? Marching west, for example, the Qing encountered the Russian Empire, another land-based polity then engaged in large-scale territorial expansion into the Eurasian steppes. The final part of this chapter will analyze how the Qing Empire sought to establish control and sovereignty over its new northern and western frontiers. In these areas, the Qing pursued a policy of establishing their authority not only over territory, but also over the people who lived and moved across the new frontier, including intermediaries such as fur traders, Mongol tribes, and Jesuit missionaries who often had their own, diverging imperial allegiances.

As the last people to rule China using a dynastic model before China became a republic in 1912, the Qing dynasty inherited two millennia of imperial statecraft and traditions dating back to the Qin unification in 221 bce. As we have seen, the Chinese dynastic model presumed an emperor (huangdi 黃帝) at its center, possessing the “Mandate of Heaven” (tian ming 天命) to rule “All under Heaven.”4 While the development of this old Zhou doctrine is especially associated with Chinese elite culture and the political unification of Han China, we have already seen that it was also embraced by many non-Han rulers of Turkic, Mongol, Tibeto-Burman, or Tungusic descent. Indeed, a list of the imperial entities that controlled a least a million square kilometers of the territory of modern China reveals that non-Han dynasties (and dynasties of mixed descent) claimed the mandate to rule “All under Heaven” for a longer period of time, cumulatively, than did Han rulers.5

The Manchus were thus the last in a long line of non-Han contributors to Chinese imperial history, and it was the Manchu symbiosis of seminomadic and Han traditions that would take China into the twentieth century and beyond the imperial mold. Before 1635, the Manchus were known as “Jurchen,” a group of Tungusic-speaking peoples living in the region of northeast Asia, often referred to as Manchuria, at the meeting point of the modern territories of China, Korea, and Russia. The historic heartland of the Jurchen stretched from the Liaodong peninsula in the south, Korea and the Pacific in the east, the Gobi Desert and pasturelands of Mongolia in the west, and the Songhua and Amur rivers in the north. The Jurchen homeland was, as Gertrude Roth Li has noted, “a place where forest, steppe, and agricultural lands overlap.”6 Reflecting this geographical diversity, the Ming divided the Jurchen into three distinctive groups: the “Wild Jurchen” hunters of the northern forest and steppe, who were furthest removed from Chinese agrarian culture; the “Songhua Jurchen” who lived a more settled existence as pastoralists and farmers along the Songhua river and its tributaries; and the “Jianzhou Jurchen” of the Changbai mountain range in the modern province of Jilin.7 Qing scholars struggle tracing the shifting shape of Jurchen or Manchu identity before their sudden rise to prominence: were they entirely nomadic people, seminomadic people, including many areas of permanent agricultural settlement, or a combination of all the above? In any case, centuries of physical proximity, trade, and warfare resulted in strong Chinese cultural and political influences on the Jurchen. In recognition of this, Chinese states such as the Ming distinguished “wild” Jurchen from those that had been “civilized” and incorporated into the Chinese world, albeit often only symbolically or nominally. Chinese states frequently recognized the more powerful Jurchen chiefs, for example, by granting them official military titles.8

The Jurchen first began to impinge on Chinese political affairs at the end of the eleventh century, at a time of competition between three great imperial states—the Song, the Liao (ruled by the Turkic Khitan people), and the Xi Xia (ruled by the Tibeto-Burman Tangut)—for control of East Asia.9 As part of Emperor Huizong’s efforts to weaken his Liao rivals, the Song encouraged Jurchen living on the northern frontiers of the Liao to rebel against their nominal overlords. The plan was to crush the Liao between a Song offensive advancing from the south and a Jurchen diversion that would harry Liao forces from the north, resulting ultimately in the restoration of northern China to Song control.10 In practice, the opposite occurred: the Song offensive against the Liao quickly faltered, whereas the Jurchen surpassed all expectations, defeating the Liao Empire and driving its Khitan rulers westward into Central Asia.11 Perceiving the weakness of the Song, the Jurchen next turned on their former allies and advanced deep into the south, even capturing the Song capital of Kaifeng together with Emperor Huizong and his heir apparent in 1127.12 The Song dynasty regrouped to survive another 152 years in southern China, but they would never regain the north.

In place of the Northern Song and the Liao, the victorious Jurchen established themselves as a new imperial dynasty known as the Great Jin. The early influence of Sinic imperial ideology on the Jin can be seen from the fact that already in 1115, at a time when the Jurchen had yet to defeat either the Liao or the Song, the Jurchen leader Aguda (1068–1123) was already styling himself “emperor” (huangdi), wore Chinese imperial regalia, and had adopted Chinese regnal and dynastic titles (Shouguo 收國 and Jin 金, meaning “Receiving Statehood” and “Golden,” respectively).13 Elaborating on governmental innovations made by the Liao before them, the Jin sought to accommodate the diversity of their subjects by establishing parallel administrations. Han subjects, in other words, continued to be ruled by Han laws and institutions, while the Jurchen became a hereditary imperial elite, set apart from their new subjects by the use of Jurchen language, Jurchen dress, the practice of martial skills such as horse riding and archery, and organization into socio-military units known as meng-an (lit. “one thousand”).14

For all the successes of the Great Jin, however, the dynasty had the misfortune to come to prominence only a century before the rise of Chinggis Khan. In the early thirteenth century, the Jin Empire would fall victim to the Mongol expansion, with Ögedei capturing the last Jin stronghold of Caizhou in 1234. Following the loss of their empire, some Jurchen made their peace with the new Mongol-dominated Yuan regime while others retreated to their ancestral lands. Manchuria, in many ways, returned to its pre-Jin condition of wild frontier area and the Jurchen divided into fractious clans and tribal confederations. As with many other steppe peoples, the Jurchen retained a collective memory of the Great Jin as a sort of imperial “ideology in reserve” that might one day be deployed under the right conditions.15

Jurchen imperialism experienced a renaissance in the seventeenth century thanks to Nurhaci (1559–1626), a particularly gifted, ruthless, and ambitious leader of the Jianzhou Jurchen. Beginning with his rise to power as a minor chieftain in 1583, Nurhaci and his sons, Hong Taiji (1592–1643) and Dorgon (1612–50), gradually unified the Jurchen and many neighboring groups (including Mongols and Han Chinese) into a confederacy under the leadership of Nurhaci’s clan, the Aisin (lit. “Golden”) Gioro. In the process, they also began to build the foundations of the political, cultural, and military institutions of the future Qing Empire.

Although the Ming Empire had been instrumental in the deaths of Nurhaci’s father and grandfather, he posed at first as an ally of the Ming and leveraged the support of the latter against his Jurchen rivals. He also increasingly monopolized the lucrative trade with the Ming, by which forest products such as furs and ginseng were exchanged for the silver bullion that Nurhaci needed to pay his growing armed forces. In return, Nurhaci offered the Ming court assistance against the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592–98 and was honored with the rank of general. Nurhaci thus seemed during his early years like any other Jurchen chieftain who collected Ming titles and participated in the Ming tributary system. In particular, such participation required Nurhaci’s formal acceptance of the Ming emperor as the legitimate holder of the “Mandate of Heaven.” In 1616, after the defeat of the last Jurchen tribe to resist the Aisin Gioro, however, Nurhaci broke with his obedience to the Ming by proclaiming himself to be the “bright khan, nurturer of all nations” (geren gurun-be ujire genggiyen han) of a restored, “Latter Jin” (Hou Jin 後金) dynasty.16 In doing so, he let the Ming know that he was no longer a loyal subject and that he aspired to control everything north of the Huai river, the same territory the Jin held in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The next key ideological development came in 1636, when Hong Taiji dispensed with the pretension of being Latter Jin—always a problematic claim inasmuch as the Aisin Gioro were not lineal descendants of the original Jin dynasty. Instead, he proclaimed himself emperor of a new dynasty, the “Great Qing” (大清), and of a new people—no longer “Jurchen” but “Manchu.” While Nurhaci’s Latter Jin dynasty might conceivably have coexisted with the Ming, in the same way that the first Jin dynasty ruled part of China while the Southern Song dynasty ruled China south of the Huai river, Hong Taiji’s dynasty was an even stronger provocation. As Timothy Brook has observed, “The symbolism of the new dynastic name implied that the Qing, a water image meaning clear or pure, would submerge the Ming, a fire image of sun and moon together.”17 Whereas Nurhaci seems to have imagined his state as a Manchurian polity perched on the imperial threshold of its agrarian Chinese neighbors, sticking close to the environmental frontiers of the steppe peoples, Hong Taiji was about to escape these confines and create an empire that was a direct rival to the Ming and appealed to Han-Chinese symbolism—like water dousing out fire. The Qing’s goal was to conquer all of China. The new name of his empire, Daicing, had a double meaning in both Manchu and Mongolian of “warrior,” further indicating its aggressive character.18 Hong died in 1643 just before the final raid one year later into northern China, which became a full-scale invasion of the Ming Empire.19

The fall of the Ming and the (second) rise of the Jurchen/Manchus has been attributed to a range of military, cultural, economic, and, most recently, climatic factors. Traditionally, contemporaries analyzing this episode in China’s imperial dynastic history argued that weak emperors manning the helm of the Ming dynasty were the main reason for the fall of the Ming. The final three Ming rulers—the Wanli, Tianqi, and Chongzhen emperors—fit well within the traditional model of the dynastic cycle, according to which all founding emperors were strong, to be followed by less powerful ones who however had the support of powerful and “righteous” ministers and generals, until, finally, weak, lazy, and possibly “evil” emperors neglected the affairs of the state and allowed power to dissipate to eunuchs and other unsavory characters (in the eyes of the Confucian scholarly elite).20 According to this view, beginning with the negligent Wanli emperor, the Ming were inevitably headed for disaster and it was “natural” that the Manchus conquered the Ming. Even recent historians who do not ascribe to the simplistic model of the dynastic cycle have often described the Manchus as an “unstoppable” force.21 This cyclical perspective on Chinese imperial history was satisfying, as Valerie Hansen has noted, inasmuch as “it always justified rule by the reigning dynasty.” Other historians, however, have objected that this explanation “makes for fine histrionics but poor history.”22

While it is true that the Wanli emperor was notoriously disconnected from the empire’s affairs after 1600, he was a strong military leader able to direct and employ Ming armies and generals who stopped the Japanese in Korea during the 1590s.23 A decade earlier, the Wanli emperor similarly employed Chief Grand Secretary Zhang Juzheng whose tax reform was “the most important transformation of the Chinese economy prior to industrialization.”24 The Wanli emperor may indeed have disengaged from any serious acts of ruling in the first two decades of the seventeenth century, however, he is not the despot who lost the empire. Even as factionalism and fighting at the Ming court came to a peak, Ming armies were, on occasion, able to contain Manchu forces, belying any notion of the Manchus’ “unstoppability.”25 In the end, however, poor leadership was clearly a critical area in which the Manchus outmatched the Ming.26

Economic factors also played a role in the fall of the Ming and the rise of the Qing. The income of Zhang Juzheng’s tax reform flooded the Ming treasury with silver, which was then spent on suppressing domestic rebellions and stopping a Japanese invasion. William Atwell has also pointed out changes in international trade patterns, particularly global silver flows, which may have resulted in a pervasive economic depression during the final Ming decade. Against this assertion, Richard von Glahn has argued that any short-term contraction in silver was not significant enough to cause a general economic recession and that Ming trade abroad and the market at home remained robust until 1642. The most besetting problem for the Ming was instead a series of “catastrophic harvests and popular rebellions.”27 Silver did influence the outcome of the conflict between the Ming and the Qing in a different way, however, inasmuch as the Ming’s desire for ginseng, which it bought from the Jurchen with silver, caused the reexport to Manchu coffers of “as much as 25 percent of the silver [the Ming] took in from Europe and the New World.”28

Finally, two recent historians have reinterpreted the fall of the Ming and rise of the Qing using the history of climate and weather.29 The hostilities between these two empires occurred at a time that climatologists have dubbed “The Little Ice Age,” a global period of crisis in the mid-seventeenth century.30 Why did so many states and empires experience some sort of political, cultural, or social crisis while at the same time “abnormal climatic conditions” lay at the basis of “the longest as well as the most severe episode of global cooling recorded in the Holocene Era [the last 11,700 years]”? Certainly, the rise and expansion of the Qing Empire coincided with a period of unusual climactic events. Subtropical Fujian, for example, experienced heavy snowfall in 1618. In 1640–41, the northern lands of the empire experienced the worst drought conditions in 500 years, while “tree-ring series for East Asia show 1643–44 as the coldest years in the entire millennium between 800 and 1,800.”31 Across the empire, harvests failed and more and more Ming officials petitioned the court for disaster relief. Such extreme weather would continue into the second half of the century, but the decade of the 1640s was the most catastrophic and, as Timothy Brook has observed, “made the era almost impossible to govern.”32 In many ways, then, weather proved the coup de grace that, in combination with economic crisis, domestic rebellions, famines, and lack of central control due to factional infighting at the court, ended the Ming empire.

Global cooling did not just affect the Ming, however; the latitude of the region where the Jurchen lived was north of the temperate zone and colder temperatures could have even greater impact than in the south. In many parts of Manchuria, a fall in mean average temperature of even two degrees reduced harvest yields by a stunning 80 percent.33 As a result, the Jurchen were themselves suffering from hunger and deprivation in the early 1600s, and the temptation posed by the grain storehouses of the Ming must have been powerful. Chronically adverse weather may thus have been a factor explaining the shift from sporadic Manchu raids against the Ming in the 1620s–1630s to full-blown invasion in 1644. The Qing leadership, however, realized that new conquests might bring as many problems as they solved. When Nurhaci’s advisors urged him to invade the Ming lands as a means of alleviating the famine at home, for example, he objected saying: “We do not even have enough food to feed ourselves. If we conquer them, how will we feed them?” He continued: “Now we have conquered so many Chinese and animals, how shall we feed them? Even our own people will die. Now during this breathing spell let us first take care of our people and secure all places, erect gates, till the fields and fill the granaries.”34

In 1644, despite such misgivings, the Manchus—led by Nurhaci’s brother, the Prince Regent Dorgon (1612–50)—prepared once again to conduct raids into the Ming’s northern provinces.35 Fortuitously for the Manchus, in April of 1644, the Ming state had reached its nadir of internal dissolution after a peasant rebellion led by Li Zicheng conquered and sacked the Ming capital. With the suicide of the Chongzhen Emperor, Ming commanders in the field found themselves caught between the demands of a usurping commoner—Li Zicheng, who had declared himself emperor—and their redoubtable Manchu enemy; many opted for the latter and Ming defectors quickly swelled the ranks of the Qing army. Most critically, the Ming general Wu Sangui, commander of the strategic Shanhai pass in the Great Wall, formally requested that Dorgon help him to expel Li Zicheng from Beijing and avenge the fallen Chongzhen Emperor. The Qing seized upon this invitation and promptly dispatched an army to Shanhai. There, the combined forces of Prince Dorgon and Wu Sangui inflicted a decisive defeat upon Li Zicheng and his bandit army on May 27, forcing them to withdraw first from the frontier and then from Beijing. On June 5, Dorgon and his army entered Beijing and took possession of the imperial palace and regalia. He proclaimed to the somewhat bewildered inhabitants that there would be no Ming restoration—the “Mandate of Heaven” had henceforward passed to the Qing.36 On November 8, 1644, Dorgon’s nephew, Fulin, the young Shunzhi Emperor (1638–61), was formally installed in Beijing as the ruler of All under Heaven.

Imperial Consolidation and Expansion

Occupation of the Ming capital was one thing; the establishment of effective Qing rule over the vast and unsettled provinces of China was quite another. It took two decades for the Qing to fight their way down to the southernmost frontiers of the former Ming Empire, defeating or co-opting one loyalist commander after the other, until General Wu Sangui had captured and executed the last of the Ming princes, Zhu Youlang, in 1662.37

The work of pacification did not end there. A local notable family of Ming loyalists, the Zheng, held out in Fujian and posed a serious threat to the new dynasty. In 1658, for example, Zheng Chenggong (1624–62), known as “Koxinga,” pushed deep into Qing territory to besiege Nanjing with 150,000 troops.38 More dangerously, Koxinga evicted the Dutch from Taiwan in 1661 with the clear intention of using that island as a staging ground for the reconquest of the Chinese mainland. The Qing responded with vigor and sought to break the anti-Qing resistance in southern China by weakening the maritime communities that provided its military and economic bases. The Qing therefore revived a long-lapsed Ming ban on unlicensed sea travel, tightly restricted foreign trade, and destroyed many private ships. The Kangxi Emperor further issued two evacuation edicts in 1661–62 ordering all residents within ten to fifteen miles of the coast from Shandong to Guangdong to move inland on pain of death.39 Tremendous dislocation and misery ensued, but the Zheng remained defiant.

The Qing campaign to drive the Zheng from their island sanctuary had to be delayed another decade as the Kangxi Emperor confronted yet another serious threat to the empire in the form of the “Three Feudatories Rebellion” of 1673–81. From the days of Nurhaci, the Qing had been acutely aware that the conquest of the Ming Empire could not be achieved by Manchu troops alone—there were simply too few Manchus relative to the size of their intended prize. Securing the acquiescence and active cooperation of Han-Chinese subjects was therefore essential and, in practice, the “Manchu conquest of China” was indeed carried out overwhelmingly by Han-Chinese soldiers and officials who had defected to the Qing cause. In recognition of these invaluable services, the Qing dynasty had appointed three of its most accomplished Han generals to rule as governors over the provinces in southern China that they had only just brought under Qing control—Wu Sangui (1612–78) in Yunnan and Guizhou, Shang Kexi (1604–76) in Guangdong, and the family of Geng Zhongming (1604–49) in Fujian. Initially, the three governors had been allowed to treat their provinces as virtual fiefdoms. As it became obvious to them in the early 1670s that the Qing court did not intend to let this arrangement become either permanent or hereditary, they rose in rebellion. The contest was thus not so much between partisans and opponents of Qing rule, per se, but rather within the Qing elite between centripetal and centrifugal visions of how the empire would operate.40

It took the young Kangxi Emperor eight years to put down the Three Feudatories rebellion and another two to finally conquer Taiwan, but by the end of 1683 Qing rule over all of the former Ming territories was firmly established. The following century that encompassed the successive reigns of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors is often referred to as the “High Qing,” being a period marked by internal security, economic and cultural achievements, and territorial expansion. Having defeated the Zheng, for example, the Qing relaxed the coastal evacuation orders in 1669 and embraced a more open set of maritime policies in 1684.41 On land, the three emperors undertook a series of ambitious campaigns that nearly doubled the size of the Qing Empire. The dynasty extended its rule westward into Outer Mongolia (effectively under Qing control by 1697), Tibet (1720), Kokonur/Qinghai (1724), Jungaria (1757), and the Tarim Basin (1759). By the late 1700s, the forces of the Qianlong Emperor were even campaigning in lands as far distant from the imperial center as Nepal and the Toungoo and Đại Việt empires in Southeast Asia.

The first three Qing dynasts—Nurhaci, Hong Taiji, and Dorgon—deliberately set out to create institutions that would unite their followers into a coherent group, while at the same time distinguishing that imperial elite from their future subjects. In particular, they were responsible for two of the most emblematic features of the Qing Empire: the banner system and the fostering of Manchu language and group identity.

The Qing banner system began as a reorganization of Nurhaci’s army and followers into four companies of roughly 300 warriors and their households, with each company distinguished by a blue, red, white, and yellow banner (Manchu: gūsa; Chinese: qi旗). As Nurhaci’s army and followers increased, the number of banner companies was doubled from four to eight, and then further divided along ethnic lines to produce eight Manchu banners, eight Mongol banners, and eight Han banners. These banners became the elite of the Manchu armed forces, a status revealed by the fact that the banners came under the personal command of the emperor or one of the imperial princes and enjoyed a virtual monopoly over artillery and other gunpowder weapons. Three-quarters of the Qing soldiery, by comparison, were enrolled in a “Green Standard Army” that stood outside the banner system and took its orders from the Ministry of War, rather than directly from the imperial house. These mostly Han soldiers of the Green Standard Army manned garrisons all over the empire and functioned as police in many rural areas, where they were less disruptive to local society than Manchu banner soldiers. In this way, as Elliot has observed, the Qing “use[d] Han to rule Han.”42

Although many aspects of the banner system remain unclear, its importance to the Qing is obvious.43 Certainly, the banner system was much more than just an army, incorporating as it did not only soldiers, but their extended families, servants, slaves, and—by extension—even the subject peoples over whom a particular banner garrison exercised authority. As the Qing conquest proceeded apace, the banners also became important vehicles for settlement and administration of the newly acquired lands. Bannermen garrisoned urban centers and outposts, administered the large estates they had been awarded in return for their services, and served in the local bureaucracy as officials. Membership in a banner passed from father to son and, as membership bestowed considerable privileges and connections to the imperial center, the banners increasingly became a hereditary aristocracy. Indeed, many historians have described the banner system as a form of feudalism, with the distinction that “the system of proprietorship that underlay it was not land but rather slaves.”44 As such, Qing banners served simultaneously as units of military organization, civil administration, and economic production.

Through the banner system, the Qing also created an imperialized form of society, in which prior clan, tribal, ethnic, and religious ties were subsumed into the banner structure and subordinated to service to the dynasty.45 The bannermen even referred to themselves as slaves (aha or nucai) of the emperor.46 This system, as Burbank and Cooper have observed, “recalls Chinggis Khan’s and Tamerlane’s efforts to fracture established loyalties” as well as the reliance of Mamluk, Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal rulers on military slaves to create a dynastic counterpoise to less reliable tribal and feudal elites.47 Particularly in the early years of the empire, the banner system was a critically important means of incorporating non-Manchu elites into the Qing imperial project. Ethnic Hans, Mongols, Koreans, and other Tungusic groups could gain membership in a banner either directly, by enlisting as a soldier, or indirectly, by having a family member marry into a banner. The fact that most bannermen were non-Manchus throughout the history of this institution underlines the Qing desire to build hybrid institutions that would accommodate and mirror the internal diversity of their multiethnic state.48 Over time, of course, the banner system lost some of this openness to outsiders as bannermen sought to protect their elite status and the borders around ethnic privilege and difference hardened.

Between the conquest era of the 1640s and the late 1700s, the continuous territorial expansion of the Qing Empire kept the banners relevant. With the start in the 1760s of the “Great Qing Peace,” which would last until the Opium Wars of the nineteenth century, however, the utility of the banners declined.49 Some historians have argued that the great peace from 1760 onward “was so overwhelming that it removed the stimulus of war.”50 The dulling of the banner and other army forces through multiple generations of inaction may indeed have been a central factor in the “great military divergence” that had opened up between Europe and Qing China by 1850.51

Certainly, by 1850, the banner system was no longer an effective military organization. There were various reasons for this. The first was technological: banner soldiers were using firearms that were at best thirty to forty years old—in theory, the maximum time period allowed for use before the Qing government was supposed to replace them. The soldiers did not have much say in this: they were responsible for the purchase and upkeep of their own bows, swords, knives, armor, and banners, but the government was responsible for arming them with firearms. There were cases, especially toward the end of the High Qing period, “where some cannons and other firearms had been used for over 100 years.”52 On a structural level, the banners were an increasing financial burden on the central state by the mid-eighteenth century, since the privileged and hereditary bannermen received a much larger chunk of the overall Qing military budget relative to the Green Standard Army than their services on the battlefield warranted.53 By the end of the long reign of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–96), the empire found it difficult to carry the ever-increasing financial burden of sustaining both its enlisted forces soldiers and the contracted laborers who provided logistical support for all military campaigns. It became obvious that the Qing military apparatus was in need of serious reforms, but Qianlong’s successors did little to address this need. Instead, the logistical and financial costs of the Qing military system continued to rise, such that in the early nineteenth century the once “abundant state treasury was almost depleted” when it had to suppress rebellions between 1795 and 1806 by the Miao tribes of southwestern China and the White Lotus Society.54 In response, the government sought to curb military expenses simply by underfunding all Qing forces, both the banners and the Green Standard Army. When the Taiping Rebellion broke out in 1850, the facility with which the rebels besieged and decimated the Manchu banner garrison in Nanjing revealed the extent to which the Qing Empire’s former elite forces had become unfit for battle, having been systematically underpaid for more than a generation. Not only had their stipends failed to keep pace with the cost of living, but they had a reputation for squandering whatever money they did receive from the state in reckless living.55 By the nineteenth century, then, the banner system—much like the Ottoman janissary corps or the Mogul jāgīrdārs—had become inimical to the very empire it had once helped to build up.

If the Qing had used the banner system to integrate a diverse range of elite groups and unite them in service of the new dynasty, they also needed means of distinguishing loyal from disloyal subjects and the new imperial elite from the masses. The Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties had used parallel systems of administration to keep their conquering ethnos—Khitan, Jurchen, and Mongol, respectively—separate from their Han subjects; the Qing similarly sought to harness Jurchen ethnicity and recreate it as a marker of dynastic identity and apartness. Most famously, in 1645, Prince Dorgon issued a Tonsure Decree (Tifa Ling 剃发令) imposing the Jurchen hairstyle on all non-Manchu subjects as a visible indicator of their submission to Qing authority. Former subjects of the Ming were given a stark choice: shave the front of their heads over the temples and braid the remaining hair in a long, single queue down the back—or face execution. The Manchu queue would remain mandatory on all Qing subjects until the 1910s, with the specifically licensed exceptions of Taoist priests, Buddhist monks, Turkic Muslims, and the inhabitants of the Ryukyu Islands.

The imperial uses of Manchu ethnicity can be seen most clearly, perhaps, in Qing attitudes toward the Jurchen language. As with the banner system, Qing policies on language were formulated early by the founding fathers of the Qing Empire and reached their most explicit formulation under Qianlong. As Elliott has noted, “Emperors from Hong Taiji on all made the link between language and identity, but none perhaps as consistently as the Qianlong emperor.”56

The formal remaking of the Jurchen vernacular into an official “Manchu” language of state began early in 1599, when Nurhaci ordered that the Mongolian alphabet be adapted to the sounds of Jurchen so that his officials could produce documents comprehensible to ordinary Manchus.57 Prior to this, Jurchen statesmen had had to produce documents written in literary Chinese and Mongolian, or else they had attempted to use Chinese characters for Jurchen in much the way that Chinese characters had been appropriated elsewhere to write Khitan, Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese.58 The emergence of the Manchu script and annalistic documents written in Manchu were thus symptomatic of an evolving and expanding bureaucracy. Over the next decades Manchu became part of the multilingual Qing correspondence, together with Chinese, Mongol, and Tibetan (or Uighur depending on the region and people involved).59 The ongoing nature of dynastic interest in written Manchu can be seen from alterations to the script ordered in the 1700s by Qianlong. Surviving state documents in “old Manchu” were promptly rewritten in the reformed “new Manchu” script.

As many scholars have noted, Manchu had many uses, both as a marker of difference and as an “exclusionary” language of state. It provided, for example, an excellent vehicle for preserving the secret nature of communications affecting national security. Manchu banner soldiers, for example, were expected to speak Manchu both in their personal lives and in their official communications with the emperor and the imperial court. It was not uncommon, moreover, for the court to omit key information when translating Manchu documents into Chinese. The frequency of such deliberate acts of self-censorship have prompted Manchu scholars to periodically remind students of the necessity of learning Manchu, and not just Chinese, if one is to appreciate the inner workings of the Qing.

Apart from serving as a “security language” for military affairs, Manchu also served as a badge of intimacy within the imperial service. Scholars such as Beatrice Bartlett and Mark Elliott have noted the more personal relationship between Qing emperors and their bannermen, in contrast to the less intimate communications with their Han-Chinese officials. Written exchanges between the Kangxi emperor and General Boji of the Bordered White Banner, for example, could be very casual in tone: “I am fine. It is cool now outside the passes. There has been enough rain, so the food is very good. There is nothing to do. Because my mind is unoccupied, I am looking really rather well. You’re an old man—are grandfather and grandmother both well?”60 On other occasions, the emperors’ feelings were still intimate but not so positive. The Yongzheng Emperor wrote the following to a Manchu lieutenant general: “I hear tell you’ve been drinking. If after receiving my edict you are not able to refrain, and so turn your back on my generosity, I will no longer want to value you or use your services. Act in accordance with my fond and well-meant instructions.”61

The importance of Manchu to the dynasty is also evident from the reaction of later emperors to the creeping Sinicization of the Manchu elite. As Chinese became the dominant language at court and in the army, the Yongzheng Emperor noted with disapproval that bannermen were even using Chinese when just “joking around.” Alarmed, the emperor issued the following edict in 1734:

The study of Manchu by banner soldiers is of the utmost importance. Hereafter let the members of the senior bodyguard, the imperial guard and all those who guard palace gates and keep watch speak only in Manchu. No Chinese should be allowed. As far as training, when the soldiers are assembled and at the parade ground, they should also be made to use only Manchu.62

Several years later, the Qianlong Emperor renewed this call for exclusive use of Manchu. From then on until the end of the eighteenth century, the dynasty made vigorous efforts to reverse the decline of Manchu language and identity.

The Qing state realized, for example, that much of the weakness of Manchu compared to Chinese sprang from its lack of a literary corpus outside official edicts. The court therefore began to sponsor generously the production of new texts in Manchu.63 The Qianlong emperor’s penchant for monumentalism was reflected in the style of his literary commissions intended to preserve and revive the Manchu language—and with it “the Manchu Way.” Besides ordering scholars to copy the dynasty’s seventeenth-century archival sources into “New” Manchu, Qianlong also authorized the compilation of a first “national history” of the early Qing. Qianlong was particularly displeased that no translations of the Buddhist scriptures had been made into Manchu when they had long ago been translated into the languages of the Mongols and Chinese, two peoples that, Qianlong noted, “were beholden to” the Manchus as “officials and servants.” He therefore sponsored a massive translation project to render the entire Buddhist canon into Manchu translation—a project that took one hundred translators eighteen years to finish and resulted ultimately in a set of 108 volumes. The emperor sponsored two more works of (invented) history, namely, the Ode to Mukden (Mukden-i fujurun bithe) and the Researches on Manchu Origins (Manjusai da sekiyen-i kimcin bithe).64 Both of these were transparently intended to preserve the Manchu identity, language, and history for generations to come. Despite all such efforts, the knowledge of the Manchu language among ethnic Manchus, banner soldiers, and even the dynastic successors of Qianlong himself continued to erode. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the last Qing emperor knew only one word in Manchu: Ili! (“Arise!”).65 In 2016, the New York Times reported that the last native speaker of Manchu to reside in the Manchu’s original homeland in the northeast corner of China had died.66 The only people who today still speak Manchu are to be found in the northwest of Xinjiang province on the border with Kazakhstan, where it is preserved by the descendants of Manchu soldiers ordered to settle this newly conquered province back in 1764.

As Mark Elliott has argued, “The Qing dynastic enterprise depended both on Manchu ability to adapt to Chinese political traditions and on their ability to maintain a separate identity.”67 It is in this context that we can appreciate how critical the banner system and the maintenance of a Manchu identity were to the Manchus’ ability to rule and hold their empire together. Not surprisingly, the rise and fall of both institutions coincided rather precisely with the division made by most historians between the “High Qing” period pre-1800, and the nineteenth-century period of decline when the Qing were dubbed the “sick man of Asia.” Whereas prior to the 1800s, for example, both the banners and Manchu identity had flourished and been instrumental in the establishment and expansion of the Qing Empire, by the nineteenth century both had become obsolete and were in the process of being replaced with Han-Chinese equivalents. Written and spoken Manchu thus gave way to cultural Sinicization, while the dynasty increasingly discounted the banners and came to rely on regionalized military forces led by Confucian scholars such as Zeng Guofan (1811–72) to defend the state from internal rebellions and external threats.68

In terms of the internal structure of the Qing Empire and its practices, Qing statecraft was in many ways similar to that of the Ming—a similarity that is hardly surprising given that both the Ming and the Qing had built upon common foundations laid down by the Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties before them. The Qing thus continued the Ming practice of ruling through a Department of State Affairs (Shangshu Sheng 尚书省) made up of Six Boards or Ministries—Revenue, Personnel, Rites, War, Justice, and Works—under the supervision of a Grand Secretariat (Neige 内阁). Two ministers, however, one Han and one Manchu, were appointed to head each ministry and keep an eye on each other. In addition, the Qing preserved the Ming institution of the Censorate (Yushitai 御史台), a group of more than fifty “whistle-blowers” who monitored the behavior of officials. They also brought back to prominence the Hanlin Academy, a “post-graduate school” of promising young aspirants eager to enter the bureaucracy, and who were always ready to voice criticism.69 Perhaps most importantly, the Qing continued the long-standing practice in China of using the civil service examination system based on classical Chinese literary texts to staff the imperial bureaucracy.

The Qing also brought with them some innovations in state institutions. The Jurchen, for example, like many peoples of the Eurasian steppe, viewed warfare and governance as processes that required frequent consultation among interested stakeholders—most especially among the members of the imperial elite. Nurhaci and his sons had regularly held such consultations with their kin, generals, and advisors, and after the Qing emperors moved to Beijing they continued to consult with a Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers (Yizheng Wang Dachen Huiyi 议政王大臣会议) on important matters of state. Besides helping to keep the bonds of loyalty fresh between the throne and its most important servitors, the “Grand Council” (as it was known after 1733) also helped the emperors to sidestep its own Grand Secretariat, which too often had acted as a bottleneck controlling the flow of information between the emperor and his officials. The Qing also created a new Imperial Household Department (Neiwufu 内务府) to care for the needs and internal affairs of the palace. The responsibilities of this body grew over time to include a wide range of activities, from the production of arms and armor to carrying out trade missions to secure luxury items for the court. The Imperial Household Department was also different in that it was staffed by bondservants (booi) rather than the Chinese eunuchs who had so dominated the old Ming court.

The territorial administration of the Qing Empire betrayed a similar mix of Ming continuities and Manchu innovations. The financial and administrative heart of the empire, for example, was formed by the eighteen provinces of “the Middle Kingdom,” China (Manchu: Dulimbai Gurun), roughly comparable in name and extent to the fifteen provinces of the Ming Empire.70 The emperors appointed a pair of civil and military governors to administer each of these provinces, which as under the Yuan and Ming, were further subdivided into prefectures, subprefectures, and counties. Set apart from this regular and centralized provincial system lay both the Manchurian homeland of the dynasty and the Qing conquests in Tibet, Inner and Outer Mongolia, Jungaria, and the “Muslim Frontier” (Huijiang 回疆) of modern-day Xinjiang. These territories were formally administered by bannermen military viceroys, although in practice local political figures such as the dalai lamas of Tibet, the hakim begs of Xinjiang, or the tribal khans of Mongolia enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy under the oversight of a Qing imperial “resident” (known as an amban). Manchuria itself was a special case. In an attempt to preserve the “purity” of the ethnic character of their homeland, the Qing excluded the region from the provincial structure of China and preserved it as a special military governorate. To further fortify Manchuria against foreign influences, the entire region was fenced off with an elaborate “Willow Palisade” (Liutiao Bian 柳條邊) composed of trenches and embankments planted with rows of interwoven willow trees. Both Han settlers and Mongol pastoralists were forbidden from traveling or settling past the bounds of the Willow Palisade. In theory, it was to remain an exclusive preserve for Manchus and those honorary Manchus, the soldiery of the imperial banners (including, by extension, Han and Mongol bannermen).

Finally, beyond the thick belt of military governorates that stretched from the Himalayas to the Pacific lay the various states that the Qing considered its tributaries (fanshu 藩属) and dependencies (shudi 属地). This long list of tributary states—from the perspective of the Qing, at least—included the khanates of Central Asia, Nepal, the Toungoo Empire (Myanmar), Lan Xang (Laos), Siam, Đại Việt, Chosŏn Korea, and the Sulu Sultanate, as well as Russia, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Great Britain. Already in 1638, six years prior to the Manchu conquest of Ming China, the Qing dynasty had established another important state body—the Mongol Department (Monggo yamun)—to manage relations with its Mongol allies and rivals. As the territories controlled by the Qing expanded, moreover, the Mongol Department became the Ministry for Administering the Outer Regions (Manchu: Tulergi golo be dasara jurgan/Chinese: Lifan Yuan 理藩院)—and its purview extended to all political relations with the various territories beyond the borders of the empire’s core provinces.71 This expansive charge included management of such sundry tasks as the distribution of ranks and emoluments to vassal rulers, collection of taxation, regulation of trade, maintenance of postal routes, and the registration of Buddhist lamas.72 In many ways, the new ministry expanded and built upon the examples provided by early dynasties. The Yuan, for example, had established a Bureau of Buddhist and Tibetan Affairs (Xuanzhengyuan 宣政院) to supervise Buddhist affairs throughout the empire as well as the temporal administration of Tibet, while the Ming had (to a more limited extent) tasked its Ministry of Rites (Libu 禮部) with managing the dynasty’s relations with tributary states.73

That this expanded empire belonged to the Manchus alone, however, was made clear by the exclusion of Han literati almost entirely from employment in the Lifan Yuan and the carrying out of most of the ministry’s internal communications in Manchu or Mongolian rather than Chinese.74 It should be noted that the Qing had no other foreign ministry, as such, until 1861, so the Lifan Yuan was responsible for managing relations both with regions like Xinjiang that were under de facto Qing control and with entirely independent states like Russia. Administratively, then, the Qing treated diplomatic relations with other states as, quite literally, a domestic affair.

Control of Frontiers and Subjects

Ideologically and administratively, then, the Qing behaved as though they were the only true, hegemonic empire or great power in the world. Other states might exist but they did so by the sufferance and paternal regard of the Qing emperor. As the Kangxi Emperor wrote in 1687 to the Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, the leader of the Gelug school of Buddhism in Mongolia:

To establish and unite into one the great kings of the world, one must be compassionate to both the inner [i.e., the 18 provinces of China] and outer [i.e., lands outside China], have no distinction between those near and far, [as if] all were one, and bestow grace upon the 10,000 nations. When the wise teaching has spread in the world, tribute will be given yearly [to the Qing].75

What happened in practice, however, when the Qing came up against other empires with similarly universalist ambitions or with sufficient strength to challenge the Son of Heaven? How did the Qing deal with such peers, establish borders, or manage relations with them? After the conquest of the lands previously occupied by the Ming Empire drew to an end in the 1680s, the major threats to the Qing over the next century all seemed to come from its far western and northern frontiers and this is where the dynasty focused its attention under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors. The vast region of Inner Asia stretching from the Pacific to the Altai Mountains and the Kazakh Steppe might appear at first blush to have posed little threat to the Qing, being poor and sparsely settled as it was. Experience had proven it to be the very cockpit of empire in Asia, however, the crucible from which the Chinggisid empires of the past had emerged and, indeed, the Manchus themselves. Conquest or at least effective control of this region and its peoples therefore was fundamental to the larger Qing imperial project.

While Qing policies aimed at pacifying the lesser Mongol, Tibetan, and Tungusic peoples of the region was broadly successful, the Qing watched with concern as two neighboring states with imperial pretentions—Romanov Russia and the Jungar Khanate of the Oirat Mongols—expanded toward China’s borders. Russian fur-traders and Cossack adventurers had been actively exploring the river systems of Siberia over the course of the 1600s. By 1649, they had reached the Amur River and began making military incursions into northern Manchuria itself. Worse, they had started to make explicit claims to the tribute and obedience of the local people. An exploratory Russian expedition in 1650–53 led by Yerofey Khabarov, for example, had built forts along the Amur, burned Manchu villages, defeated a larger force of Manchu troops, and demanded that the local people and their rulers submit to the Russian tsar.76 Further west in the 1650s, the Jungar or Oirat Confederation under Galdan Khan had begun to unite the western Mongols and seemed poised to create a reunified empire of all the Mongols on the Qing’s vulnerable northwestern frontiers. The subsequent Jungar conquest of the Turkic Muslim principalities of the Tarim Basin in 1678–80 and joint Russo-Jungar attacks in 1687–88 against the rival Khalka Confederation underlined the threat that the Jungar Khanate posed to Qing strategic interests in the region.

Clearly, something had to be done, but what? In the past, a succession of Chinese empires from the Qin to the Ming had sought to contain the political disorder that spilled off the steppe through a reliance on the tribute system, “setting barbarian against barbarian,” and the construction of a defensive network of walls and garrisoned forts. The Qing, less intimidated by the steppe, perhaps, on account of their own origins, opted for a more aggressive, forward strategy and sought to project their direct authority far beyond the established limits of urban settlement. This strategy resulted in radically different policies toward the two rivals of the Qing in Inner Asia.

Toward the Jungar Khanate, the Qing adopted a policy of direct confrontation and, ultimately, of extermination. Beginning in 1690, Qing armies—in many cases led by the emperor himself—undertook a succession of aggressive campaigns against the Jungars. Despite mounting costs and many frustrating reverses, by 1758 the conquest of the Jungar Khanate—the last of the large steppe nomad empires—was complete. Not content with political submission, the Qianlong Emperor issued orders for the physical eradication of the Jungar populace after a final, ill-fated rebellion against Qing authority led by Prince Amursana in 1755.77 The very name of the Jungars was to be expunged, all men capable of bearing arms massacred and women and children enslaved. One Qing historian estimated that of the original Jungar population, 40 percent had died of smallpox, 20 percent had fled into exile, 30 percent had perished at the hands of Qing forces, and the remainder had all been enslaved.78 In their place, the Qing state resettled Jungaria with colonists from the rest of the Qing Empire and from the neighboring Turkic Muslim cities of the Tarim Basin.

Toward Russia, by comparison, the Qing opted for a much milder policy of diplomatic engagement, compromise, and watchful coexistence. In truth, the Qing Empire’s struggle against the Jungars made a more conciliatory policy toward Russia essential if the Jungars were to be isolated from outside aid and assistance. More specifically, the Qing concluded two formal treaties with the Russian Empire: the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 and the Kiakhta trade treaty in 1727. These treaties are of particular interest for historians of the Qing Empire, and not merely because they would set the tone for Russo-Qing relations into the early twentieth century.79 They were the first treaties to be signed by the Qing with a European power and the only ones to be signed when the Qing could still negotiate from a position of relative strength. As such, they provide a unique window on Qing political attitudes.

As Peter Perdue has noted, one of the reasons the negotiations between Russia and the Qing were so unusual was precisely because of their conflicting universalist imperial claims and ideologies. Neither empire “believed in equal-status negotiations between sovereign states [and] both acted from hierarchical assumptions of tribute, vassalage, and deference.”80 Even the simple act of talking to one another raised thorny issues of protocol. If the Russians were seen as visiting the Qing, for example, Manchu practice would have demanded that they kowtow to the representatives of the Son of Heaven and render tribute; if the Qing were seen to be visiting the Russians, they would have been walking into a figurative minefield strewn with potential insults to the dignity of their imperial master, as well as raising the awkward question of how a foreign embassy could “receive” representatives of the Qing on lands that the Qing still considered theirs! To avoid such difficulties, the two parties simply omitted to meet at all, formally. Instead, they pitched two tents next to one another and communicated across the ambiguous void space between their two splendid, imperial solitudes.

Two other factors allowed the two empires to square the circle and treat each other as de facto equals. The first was the existence of a common rival to the expansion of both states: the Jungar Khanate. This was a particularly motivating consideration for the Qing. If for Russia, the greatest benefit to be secured through the treaties of Nerchinsk and Kiakhta was primarily economic, the Qing dynasty wanted assurance that it could commence hostilities against the Jungars without fear that Russia would assist them in the form of materiel, manpower, or asylum from pursuit by Qing forces.81 The second essential factor to the success of the negotiations was the existence of third-party mediators, who, while pursuing their own agendas, made it possible for the two empires to negotiate at arm’s length. In the case of Nerchinsk, these intermediaries were Mongols and—most importantly—Jesuits, who acted as interpreters and advisers to the Qing.

By the time of the Treaty of Nerchinsk, Jesuit missionaries had been operating in the Chinese mainland for almost a century. Yet they had struggled to secure permission to evangelize in China, so the Jesuits realized they needed to reinvent themselves as desirable imperial subjects of the Qing. To this end, the Jesuits learned Chinese and presented themselves in the dress of Confucian scholars. In a further attempt to make themselves useful to the Chinese elite, they showcased Western technology, cartography, and mnemonic methods as a means of establishing their credentials before introducing their religion. While some Chinese never stopped wondering why the Jesuits went to such lengths to talk about religion, the Jesuit strategy did eventually secure them a role at both the Ming and Qing courts as scholars, astronomers, cartographers, diplomats, and religious experts—all skills that the Qing recognized as essential to the repertoire of any empire.82

Indeed, if there was one organization that incorporated the global movement of people, ideas, and goods from 1550 until 1750, it was the Society of Jesus.83 In particular, the Jesuits acted in many places across Asia as freelance “imperial consultants,” offering their specialized services to multiple imperial states in exchange for influence and freedom to promote the Catholic faith. In South Asia, for example, Jesuits sought to carve out a niche for themselves at the court of the Mughal emperor while acting as translators and interpreters for the Portuguese; in Guam, they implemented Spanish colonizing policies; in Japan, Jesuits acted as advisers to great feudal lords like Oda Nobunaga while simultaneously promoting Spanish and Portuguese interests there.84 Qing emperors saw their Jesuit advisors precisely in this light as agents who were not to be trusted but who might be very useful, especially when operating in strategically and politically volatile areas such as frontier regions between competing empires.

It was this reputation for utility that moved Kangxi to send two Jesuits to Nerchinsk to assist at the meeting with the Russian delegation: Jean-François Gerbillon (1654–1707) and Tomé Pereira (1645–1708).85 Although the pair presented a united front to the outside world, the two men did not get along on their first mission together, a situation aggravated by the ongoing dispute between French and Portuguese Jesuits in China since the arrival of the first French Jesuits in 1685 over whether to steer Qing policy in favor of Portuguese or French interests.86 Despite this rivalry, the Jesuits served the Qing well at Nerchinsk. The Kangxi Emperor had been anxious, for example, to prevent Mongols from acting as go-betweens at the negotiations. Mongolian was the obvious language for the negotiations to be carried out in as it served as a lingua franca along the northern frontier, but the rise of the Jungars had thrown the Mongol world into an uproar and the emperor felt that Mongols—especially any Mongols that the Russians might use—could not be trusted. The Jesuits therefore outmaneuvered the Mongol intermediaries by convincing the Russians that there were not enough Mongolian translators, that those present were incompetent, and that the negotiations would be more “objective” if carried out in Latin, which the Jesuits spoke fluently as did one Polish member of the Russian delegation.87 Having gained de facto control of communications between the two parties, Gerbillon and Pereira helped to steer negotiations toward Kangxi’s principal goals.

The resulting treaty, produced in Latin with Russian and Manchu translations, demarcated for the first time an exact (albeit incomplete) boundary between the lands of the Qing and those of Russia by using the Gorbitsa and Argun rivers and the Stanovoy Mountains (Arts I and II).88 The Qing were left secure in their possession of Manchuria, while the Russians were left with the troubled area between the Argun River and Lake Baikal that bordered on the lands of the Jungars. The achievement of a bilateral agreement to respect the sovereignty of each empire over their respective subjects was quite as significant as the demarcation of territory. Whereas the porous frontier had long made it possible for bandits and rebels of all descriptions to evade Russian or Qing authority, for example, the Treaty of Nerchinsk specified that henceforward both parties were bound to apprehend and surrender any fugitives or criminals back to their empire of origin (Arts IV and VI). The Qing clearly gained most from the negotiations, but the Russians could comfort themselves that their merchants were guaranteed entrance to China for the purposes of trade and travel (Art. V) and that the agents of the Russian tsar had not been forced to make any of the usual humiliating marks of submission to Qing supremacy.

By the end of the 1600s, then, the Qing and Russian empires had cooperated to bring about a profound change in the character of the region. The most defining geopolitical characteristic of this vast region of Inner Asia for more than four centuries prior had been its fluidity. It was rare to find clear, effective, and durable control of space, robustly enforced by state power, anywhere in a region that remained volatile, contested, and predominantly populated by nomadic peoples. As a result, political power in the region was understood to be rooted in control of people rather than territory. The expansion of the Qing and Russian states toward each other brought this formlessness to an end as they subjugated the peoples, polities, and space between them through brute application of force majeure. In this effort, the two great empires found a point of common interest that drew them to cooperation rather than conflict. Neither wished to allow peoples, power, and trade to move as they wished through this vast region. Both sought to tie down peoples, by fixing and enforcing clear frontiers, controlling movements, overbearing and absorbing local military power, and regulating economic activity. The Jungar Khanate, by comparison, was a less promising partner. Being still in a very early phase of its state formation, the Jungar Mongols were seen as deeply subversive of the sort of stabilization of the Inner Asian frontier that the Qing and Russian empires wanted. Jungar plans to unite the Mongol peoples across imperial borders posed a direct threat to the Qing, who relied heavily on Mongol supporters, and would have interfered with Russian plans for expansion around Lake Baikal and into Central Asia. The nomadic forces of the Jungars moved opportunistically across the steppe, often crossing into Russian or Qing territory in search of pastures, plunder, and safe refuge from their enemies. Clearly, the Jungars were not ready in the late 1600s for the sort of tacit imperial association that Russia and the Qing were contemplating—and the price of the Jungars’ nonconformity was their obliteration. Henceforward, Inner Asia was to be the frontier zone not of many polities but of two great empires, who concentrated on consolidating their control of this space until the fall of the dynasties that reordered it.

Despite the increase of centrifugal forces across most Asian states from the seventeenth century onward, there is little evidence prior to the nineteenth century to suggest that the Qing were losing control over their peripheral or most recently acquired territories, as was happening in other major Eurasian empires such as the Ottomans or the Mughals.89 To some extent, this was due to the Manchus’ jealous reluctance to recognize or permit the devolution of state power onto local potentates.90 The Qing dynasty had instead insisted on keeping administrative control firmly in its hands. Newly conquered regions such as Xinjiang or Taiwan were placed under various forms of military rule, whereas Mongolia was ruled by military garrisons or tribal nobilities.91 The Qing also sought to strengthen its hold over contested areas by planting settlements of loyal colonists selected from the banners or various parts of China. The long struggle required to subdue regions such as Taiwan, Jungaria, and the former holdouts of Ming or Zheng loyalists in southern maritime China ensured that the imperial center remained suspicious of conquered people for a long time. However, such deeply engrained distrust could prevent the Qing from gaining an accurate picture of developments in these regions. In the southeastern provinces of Fujian and Guangdong, for example, a chronic lack of connections between official circles and the society around them meant that the outbreak of the First Opium War in 1839 caught the dynasty completely unaware of the local ramifications of the growing European mercantile presence in the region.92

In the short term, however, the 1700s was an era of serene repose for the Qing Empire, marked by peace and a sense of easy superiority. The dynasty had subdued or reconciled all apparent threats from both overland and by sea. No new nomadic empire would rise on the northwestern frontier to challenge Qing authority again, while European maritime contacts were conducted entirely on the Qing Empire’s terms. The Qing’s trade balance was, as it had been for a long time, positive, in the sense that the outside world eagerly sought out China’s products and was willing to pay China’s price for them. The empire of Qianlong had thus arrived at a golden age, both economically and militarily.

Over the second half of the eighteenth century, however, the Qing began to fall victim to their own success. Economically, the Kangxi and Qianlong emperors’ laissez-faire attitude left the state fiscally weak at a time when the empire’s population was booming, but its productive capacities were not keeping pace.93 Toward the beginning of the nineteenth century domestic social ailments such as the millions of Qing subjects addicted to opium signaled a sea change in the Qing’s relationship with the outside world and, more particularly, with Western empires such as Britain that were actively promoting the opium trade. The Qing government came to the logical conclusion that the opium trade was an unacceptable drain on the resources and good order of the empire, but when it moved to interdict the trade it ran up against the stubborn resistance of a British Empire that was better equipped than the Qing to defend the interests of its merchants and smugglers.

The result was the Anglo-Qing Opium Wars (1839–42 and 1856–60), two mismatched contests that abruptly laid bare the Qing’s failure to keep abreast of military and technological developments among its imperial rivals. Defeat in the First Opium War came as a particularly rude shock for the Qing court, following as it did two centuries in which the Qing had been militarily equal or superior to all its challengers. In most of its encounters with the British army and navy, Qing forces were bested and the British acquired a stranglehold on the riverine and coastal trade of the empire with disturbing ease. As a Qing contemporary to these events grimly observed in 1843: “From the time of the piracy in the Ming period, there have been more than two centuries passed here without military disaster, and now we have been twice violated by the British.”94 Although the Qing Empire was thus territorially intact at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it could no longer present a convincing façade of easy superiority over all rivals.

Between 1600 and 1800, the accomplishments of the Qing dynasty had been truly extraordinary. Beginning from a small frontier chieftaincy they had created one of the largest and most populous empires in the world, which at its height in the late 1700s ruled over perhaps 360 million subjects and extended over thirteen million kilometers from Kyrgyzstan to the Ryukyu Islands and from the Amur River to Hainan in the South China Sea.95

The legacies of such an entity to the state of modern China are obvious and immense, not least of these being the very concept of a Han-dominated but multiethnic China itself. Prior to the Qing, “China” had referred only to the core lands of Han history and culture between the Great Wall and the highlands of Southeast Asia and from the Sichuan Basin to the East China Sea. The Qing, as a matter of policy, had insisted from the outset on conflating their empire—all of it—with “the Middle Kingdom.” Wherever the dynasty acquired territory in Mongolia, Tibet, Central Asia, or anywhere else, in other words, the new lands and people automatically became part of a single, Chinese imperial “family,” a notion that was expressed in a recurring slogan of the dynasty that “centre and periphery are one family (Zhong wai yi jia 中外一家).” In 1755, the Qianlong Emperor explicitly criticized the popular, non-dynastic view of China, “according to which non-Han people cannot become China’s subjects and their land cannot be integrated into the territory of China. This does not represent our dynasty’s understanding of China, but is instead that of the earlier Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties.”96 While the Qing’s Han subjects may not initially have accepted the dynasty’s expansive vision of “China” as their own, the long-term impact of the Qing Empire’s frontiers is undeniable when looking at a map of the People’s Republic of China today. In Peter Perdue’s evocative phrase, the Qing’s two centuries of aggressive imperial expansion became “the sceptre that haunts the modern [Chinese] nation.”97

The Qing managed to redefine more than just China, however. At its height, the Qing Empire served as the very paragon of “empire” for much of Eurasia. Courts from Ayudhya to Seoul fretted about where they fit within the Qing system of tributaries and imitated Qing imperial protocols and practices. In the East, of course, there was nothing new in such emulation as China had long exercised a hegemonic influence over the culture and politics of the larger Sinosphere that included much of the Himalayas, Inner Asia, Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan. By the 1700s, however, many Europeans too had come to regard China as the very paradigm of a perfect empire and the Qing as model emperors. The admiration of European statesmen and scholars was directed not merely at the size and wealth of the Qing Empire, but precisely at its administrative structures, laws, and political policies—in other words, its reputation for exceptional imperial statecraft.98 Francois Quesnay, one of the leaders of the influential Physiocratic school of economic thought, promoted the Qing as the very model of rational autocratic government and one that “deserves to be taken as a model for all states.”99 Voltaire, similarly, declared China to be “the wisest and best governed nation in the universe,” and singled out specific features such as its religious tolerance, the examination system, and the Qing system of bureaus and councils for particular praise. “The human mind cannot imagine a better government,” he enthused, “than one where all is decided by great tribunals subordinate to one another and staffed by men who have proven themselves qualified for their task by having taken several difficult examinations.”100

If the Qing thus occupied a key ideational space among Asian polities as the grandest and best of empires, a correspondingly gaping vacuum opened up as the Qing began demonstrably to decline in power and authority over the course of the mid-nineteenth century. Europeans were the first to begin casting aspersions on Qing statecraft, initially from pique at their treatment by the Qing and new ideas in Europe itself about models of governance, but increasingly on the basis of practical experience with the failings of the Manchu administration and armed forces. Western observers increasingly viewed China not as a model of sagacity and policy, but as an object lesson in what modern empires could no longer afford to be: backward, inward looking, unenterprising, and uninterested in the latest innovations in science, technology, and administration.101

Asian statesmen too began to have their doubts when the Qing proved unable to protect their “dependencies” from European incursions or from imperial Japan. One by one, the Qing’s neighbors stopped sending tributary missions to the imperial court in Beijing, either by choice or more frequently because rival empires prevented them from doing so: the Kazakhs sent their last mission in 1823, Siam in 1852, Toungoo Burma and the Ryukyu Islands in 1875, Vietnam in 1882, Korea in 1894, and Nepal in 1908.102 The impression that the Qing imperial order was failing meant that Asian states that had once looked to Chinese models scrambled to learn the new repertoire of European imperialism. As the Japanese Foreign Minister Munemitsu Mutsu observed: “Japanese students of China and Confucianism were once wont to regard China with great reverence. They called her the ‘Celestial Kingdom’ and the ‘Great Empire,’ worshipping her without caring how much they insulted their own nation. But now, we look down upon China as a bigoted and ignorant colossus of conservatism.”103

With a contradictory mixture of naiveté and perspicuity, statesmen and intellectuals across East Asia argued that just as the assimilation of Chinese culture had formerly meant recognition and a certain status within the Chinese imperial schema, so in the nineteenth century Westernization was the only way to secure a place within the emerging European-dominated world system. As the headline of one Japanese newspaper declared somewhat paradoxically in 1884: “Japan must not be an Oriental country”!104 The new watchwords of empire in Asia were no longer to be Sinicization, tributary relations, and “All under Heaven,” but Westernization, “Progress,” free trade, constitutional monarchy, race, and nation.

Notes

1William Rowe, China’s Last Empire: The Great Qing (Cambridge: Belknap Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 1.

2Pamela Kyle Crossley, Helen F. Siu, and Donald S. Sutton (eds), Empire at the Margins: Culture, Ethnicity, and Frontier in Early Modern China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

3Tonio Andrade and William Reger (eds), The Limits of Empire: European Imperial Formations in Early Modern World History: Essays in Honor of Geoffrey Parker (Burlington: Ashgate, 2012), pp. xix, 1, 4.

4For an important introduction, see Mark Edward Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007), p. 62.

5For such a list, see: Peter Turchin, “A Theory for Formation of Large Empires,” Journal of Global History 4, no. 2 (2009), 193.

6Gertrude Roth Li, “State Building before 1644,” in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 9 Part One: The Ch’ing Empire to 1800, ed. W. J. Peterson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 9.

7Ibid., pp. 10–11.

8Jonathan Spence, The Search for Modern China (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1990, 1999, 2013), p. 26; Roth Li, “State Building before 1644,” p. 14.

9F. W. Mote, Imperial China, 900–1800 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), chaps 1–8.

10Dieter Kuhn, The Age of Confucian Rule: The Song Transformation of China (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 61–70.

11Tonio Andrade, The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016), pp. 33–4.

12Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Emperor Huizong (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), chaps 13–17.

13Hok Lam Chan, “The Dating of the Founding of the Jurchen-Jin State: Historical Revisions and Political Expediencies,” in Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary, ed. Alessandra Pozzi, Juha Antero Janhunen, and Michael Weiers (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006), pp. 55–72.

14Herbert Franke, “The Chin dynasty,” in The Cambridge History of China: Volume 6 Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368, ed. Herbert Franke and Denis Twitchett (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 265–91; Valerie Hansen, The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2015), p. 306.

15Nicola Di Cosmo, Ancient China and Its Enemies: The Rise of Nomadic Power in East Asian History (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 184; and Philip Carl Salzman, When Nomads Settle (New York: Praeger, 1980), pp. 1–20.

16Rowe, China’s Last Empire, p. 15; Spence, The Search for Modern China, p. 28.

17Timothy Brook, The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010), p. 249.

18Mark Elliott, Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World (New York: Longman, 2009), p. 55.

19Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 256.

20Valerie Hansen, The Open Empire: A History of China to 1800 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000), p. 6.

21Kenneth M. Swope challenges these conceptions from a military point of view in his works A Dragon’s Head and a Serpent’s Tail (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009) and The Military Collapse of China’s Ming Dynasty, 1618–1644 (London and New York: Routledge, 2014).

22Hansen, The Open Empire, p. 6; Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 241.

23Swope, A Dragon’s Head, pp. 7, 295.

24Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 119.

25Swope, The Military Collapse, chap. 2.

26See also Wang Jinping’s conclusion to Chapter 2 in this volume.

27William S. Atwell, “A Seventeenth-Century ‘General Crisis’ in East Asia?,” Modern Asian Studies 24, no. 4 (1990), 664–5; and Richard von Glahn, Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000–1700 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); Richard von Glahn, The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 311.

28Rowe, China’s Last Empire, p. 14.

29Brook, The Troubled Empire; Geoffrey Parker, Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013).

30Parker, Global Crisis, pp. xvii–xix.

31Ibid., pp. 125 and 135.

32Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 73.

33Parker, Global Crisis, p. 18.

34Jiu Manzhou Dang, vol. 1, p. 103, quoted in Roth Li, “State Building before 1644,” pp. 39–40.

35Peter Perdue, China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2005), p. 48. Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 250.

36Parker, Global Crisis, p. 137. Brook, The Troubled Empire, p. 254. Mark Elliott, The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), p. 3.

37Rowe, China’s Last Empire, p. 25. Lynn A. Struve, The Southern Ming 1644–1662 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984).

38Tonio Andrade, Lost Colony: The Untold Story of China’s First Great Victory over the West (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011), pp. 84–98; Xing Hang, Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c. 1620–1720 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 115–24.