The existence of “empires” in island Southeast Asia1 has been alluded to by some scholars, especially in describing the polities of Srivijaya, Majapahit, and Melaka.2 Southeast Asian imperialism, however, has not been examined anywhere near as intensely as the process of state-formation in general during the premodern period. Southeast Asianists have identified various “state” structures as typical of the region, ranging from “port-polities” to “city-states,” “charter states,” “theatre states,” “hydraulic states,” “galactic polities,” “absolutist states,” and “gendered states and transvestite alternatives.” Scholars have also arrived at divergent views on the nature of these structures, ranging from “anarchy” and “incongruous”3 on the one hand to “imperial constructs”4 on the other.5 Despite this lack of focused study hitherto, the concept of empire can be a useful lens for making sense of the historical experience of this time and place—and for reconsidering how we should situate both within the wider contexts of Asia and the world, as well as in the literature. Where should one search for “empire” in the Malay world of insular Southeast Asia? When (if at all) did such “empire-formation” take place? And how was it related to the broader processes of state-formation? Could empire-building be seen as integral to the evolution of the layered forms of power or “layered sovereignty” that characterized this complex region?

Space and the manner in which it was understood, controlled, and used seem to be so frequent an issue in trying to understand empire in history that it can form a useful starting point here. Empires have often been conceptualized as polities that revolved around a core or center of territory and people, that possessed a consciousness of dominion over space and peoples beyond this core, and that were able, by varying means and with varying degrees of control, to exercise authority over these peripheries. An empire might extend its control or influence over a well-defined territory or it could have rather porous borders; it might be fairly homogenous with some minority components, or it might constitute several distinct ethnicities with their own local or provincial governments and political structures. The center-periphery relationship was usually asymmetrical, with the center extracting resources from the subject-periphery; but the more successful cases would often be marked by a more symbiotic patron-client relationship. Whatever the forms of economic relationship, they were often further sealed by political-religious ideology that forged ties of loyalty, or acted as the glue that bound disparate entities together. In the case of the Malay world, however, how did imperial centers exercise and consolidate control over peripheries prior to the arrival of European colonialism? What were the instruments of control, bases of legitimacy, and sources of unity that bound multiple ethnicities and diverse structures together?

This chapter will begin by glancing at the historical evolution of political structures of polities in insular Southeast Asia starting from Srivijaya in the eighth century and proceeding through the development of Malay/Muslim political structures in Melaka, Aceh, and Johor down to the eighteenth century, during which time such polities increasingly came into sustained and systematic geopolitical contact with both each other and the wider world. Although Srivijaya was a Buddhist state and therefore differed from the Muslim polities that became the norm in the Malay world, it has been included as the prototype of the insular harbor polity whose major characteristics were inherited and recast by Melaka, then in turn by Aceh and Johor. Given the numerous archipelagic polities that stretched from Aceh in the west to the Moluccan islands in the east, it is beyond this chapter to include all major Malay polities, and so readers may question why significant entities such as Makassar, Banten, and Mataram have been omitted. While these other polities were unquestionably important, Srivijaya, Melaka, Aceh, and Johor deserve special attention as they provided the exemplars of the principal Malay/Muslim political structures that would come to characterize the entire region by the eighteenth century.

This chapter does not seek to convince the reader that there were indeed empires in early-modern Malay Southeast Asia, whether unique to the region or comparable to those found elsewhere. It tests the use of empire as a conceptual framework to help make sense of the historical experience and political structures of the region, internally and in the larger Asian context. It will examine key features of the state-structures of Srivijaya, Melaka, Aceh, and Johor—their forms of power and legitimacy, ideology, forms of control (people, economic resources, military), and the nature of center-periphery, overlord-vassal relations, as well as relations with larger Asian empires in China, India, and the Turco-Persianate world. Pursuing these questions, this chapter will invite the reader to consider whether in the Malay world, the characteristics that could indeed define empire as that term is more broadly defined and historicized were indeed present or not.

It will then evaluate the received view of most scholars that while mainland Southeast Asia embarked on centralization and was successful in the “empire-building” project by the eighteenth century, insular Southeast Asia failed and became fragmented. Using a broader understanding of empire, this chapter argues that the insular Malay/Muslim world forged its own imperial constructs, reflecting local contexts—geography, political, cultural, and religious norms. Though localized, the Malay world was not isolated but connected to other, especially Muslim, empires, and a certain degree of inter-imperial political and cultural borrowing did take place.

Srivijaya, 700–1400: Seventh-Century “Harbor City” or “Imperial Construct”?

It is now appreciated that in the Malay archipelago some areas supported advanced chiefdoms, stratified societies, and complex systems of symbolic legitimation predating Indianization, and that Southeast Asians had pioneered trade circuits across the Bay of Bengal.6 The concentricity of entrepôt and polity, harbor cities, or coastal confederacies was an almost universal phenomenon in maritime Southeast Asia.7 One such example was Srivijaya—a polity which reflects what some scholars called the “mandala model.” According to Herman Kulke, the main center of such mandala polities was the kedatuan (a Malay term used in Srivijayan Sebokingking inscriptions)—the politically weighty but spatially limited residence of the datu or ruler, a fenced compound similar to the Javanese kraton (royal palace).8 The center of the concentric “field of force” of Srivijaya was thus the datu of Srivijaya.9 The urban concentration around his residence would include religious buildings, parks, markets, and semirural riparian villages.10 Together, these formed the first circle or core area of the mandala, surrounded by another circle composed of localities or communities, known variously as desa, wanua, or samaryyada (from Sanskrit), that were ruled by local leaders who had been entrusted with the charge by the more powerful datu at the center (although these local leaders sometimes only uneasily recognized the authority of the primus inter pares, the ruler himself). Beyond these desa lay outlying concentric circles, referred to as bhumi in the inscriptions, that constituted the outer reaches of the polity.11 Besides this mandala model, another model offered by archeologists is the hierarchical upstream-downstream organization involving a primary focal urban center downstream from one major river and a series of upstream secondary/tertiary centers along the same major river basin.12

The relationship between the inner core of the mandala and its outlying circles, as well as between the focal downstream and peripheral upstream communities, was grounded in formal alliances or bonds cemented by oath-taking rituals. This geographical representation epitomizes the spatial integration of the polity in a riparian landscape. It in no way conveys the notion of a topographically well-defined territory. What is essential here is the center-periphery relationship with the ruler at the center as the pivot of the polity, the focus of centripetal forces that keeps the system together. The main feature is the maintenance of a network of relations. In this sense, Srivijaya sought not a territorial empire but control over strategic points on the main trade routes of the Melaka Straits.

From the fourth to fifth centuries, Srivijaya profited from international trade by dominating the Melaka Straits, the most practicable route for east-west bulk trade and supplying China with local products and drugs and fumigants from Persia and the Arab world. Old Malay inscriptions from the 680s refer to bloody conquests of rival ports such as Kedah and other harbors in North Sumatra. By the eleventh century, a Chinese account described Srivijaya as the “uncontested master of the Straits receiving tributes from fourteen cities.”13 Dependencies were obliged to supply specified goods for export and to divert vessels to Srivijaya’s harbor. Its control of maritime trade in the Melaka Straits was achieved by the support of local sea and riverine peoples called the orang laut (sea people) who had a more or less tributary relationship with the ruler. In return for assured markets for their goods and marks of royal favor, these orang laut supplied Srivijaya with pearls, turtle shells, and piloted ships, guarded the Straits, and enforced royal restrictions on trade.14 Besides the Straits, on land, the Musi and Batang Hari rivers provided access to the interior of Sumatra, where Srivijaya obtained jungle produce and gold.

The acquisition by the ruler of prestige and luxury goods from trade and the redistribution among clients provided the basis for the exercise of economic influence and political authority in Southeast Asia.15 One distinctly regional feature which has been identified by scholars is the importance of the distribution of material largesse by a chief to sustain his spiritual aura.16 Among the tributaries, Srivijaya’s rulers sought to inculcate loyalty and stigmatize treason (derhaka) by emphasizing their magical potency (sakti), presenting themselves as Bodhisattvas.17 Effective administration was not via a centrally managed bureaucratic structure, but through the ruler’s exercise of patronage and reciprocal relations with the elite. Relations between the center and component parts of the state, which were inherently fragile and fluctuating, were held in balance by the ruler’s individual strength and charisma, making them what Wolters called “men of prowess.”18

Due to Srivijaya’s strategic location, the port-polity functioned as a “gateway city,” not only controlling economic and political relations with the interior and surrounding regions, but assuming the undisputed role of cultural brokers.19 Srivijaya’s reputation for cultural refinement attracted both regional and foreign elites. In the 600s, Srivijaya reportedly had a thousand monks and it became a center for Mahayana Buddhist scholarship, while the ruler generously patronized Buddhist endowments in India.20 Old Malay became the lingua franca of inscriptions and the speech and culture of people in the Musi and Batang Hari Basins came to be referred to as Melayu. Commercial ties and Srivijaya’s prestige produced imitation of the Srivijayan court’s linguistic and ritual practices as far afield as Java and the Philippines.

Srivijaya nurtured relations with China and maintained its tributary allegiance to China from the 600s to 1300s.21 This gave it privileged entrée to the imperial court, increased Chinese interest in Srivijayan goods, and strengthened Srivijayan rulers’ commercial position at the Straits by the prospect of Chinese diplomatic support against local challengers.

Herman Kulke concluded that Early Srivijaya was neither an empire nor a chieftaincy but a typical Early Kingdom, characterized by a strong center and surrounded by a number of subdued but not yet annexed or “provincialized” smaller polities. Indeed, he argued that “the longevity ... of Srivijaya was based on the very non-existence of those structural features that historians regard as pre-requisites of a genuine empire.”22

What, though, was a “genuine empire”? Moving away from the dominant understanding of empire, one may ask—are state consolidation and political, if not territorial, integration necessary conditions for empire-formation? If one uses the lens of a more universal view and understanding of the term “empire” as an entity that revolved around a core or center, where the center possesses a consciousness of some form of hierarchical control over space and peoples beyond this core, and was able, by varying means, with varying degrees of control, to exercise some sway over these peripheries and to seal this relationship with political and religiously based ties of loyalty, then Srivijaya reflects most of these features. Moreover, unlike the politico-military structures which constitute the dominant conception of empire, as Herman Kulke has pointed out, the very nonexistence of these structural features ensured the resilience of Srivijaya. Srivijaya survived as an “imperial center” for almost six centuries because of its localized or indigenous forms of control, based on pledges of allegiance to the center (rather than territorial annexation) and decentralized, elastic, and minimalist administrative state structures.

Melaka, 1400–1600: Islamic City-State or a Global Malay/Islamic Center?

According to Anthony Reid,23 the Mongol invasion of the 1290s, the southward immigration of Thai-speakers, climatic changes, and a rise of seaborne east-west trade were factors that had a role in the emergence of “maritime city-states” in Southeast Asia from 1400 to 1600.24 Muslim Arab and Indian traders came to form the majority in Southeast Asian ports and they were primarily responsible for establishing the earliest “Islamic city-states” such as Melaka, Pasai, Aru, Kampar, Inderagiri, Brunei, and the Moluccan islands of Tidore and Ternate (with the exception of the Banda Islands, which were ruled by an oligarchy of orang kaya or merchant aristocrats instead of a raja or sultan).25 Reid saw these city-states as forming a “system” since almost all were monarchies, with a cosmopolitan ruling class highly dependent on foreign trade, all sharing similar political and geographical features and, most critically, a common language (Malay) and religion (Islam).26

Although there were some radical political transformations that took place in insular Southeast when coastal confederacies such as Buddhist Srivijaya declined and were succeeded by Islamic “city-states,” Melaka inherited five key features of Srivijaya’s political, economic, and cultural structures. These features were: location near the Straits, orang laut support, Malay culture, Chinese imperial patronage, and fluid, amorphous center-periphery relations. Just like Srivijaya, Melaka had a political center (negeri) similar to the kedatuan and its relationship with the periphery was described in terms of the confluents, bends, and reaches of a river system (anak sungei dan teluk rantau).27 However, Melaka’s hinterland need not directly surround the entrepôt nor be directly upstream of the negeri. It could rather be seen as a regional trade sphere extending a few hundred miles from the center and could be described as an “umland” lying beyond the entrepôt but linked by Melaka’s network of waterways, both riverine and maritime.28 The various river basins that constituted this umland included other polities that had entered into various degrees of reciprocal alliances with the rulers of Melaka such as Pasai, Pedir, Siak, Inderagiri—sometimes competing with each other or even forming central places of their own. However, at the height of Melaka’s power, these polities were said to be “in dependence” or “tributaries” (jajahan/takluk) of Melaka.29 Similarly, Srivijaya had kept under its “submission” (bhakti) a variety of polities from its own Musi River basin, such as Jambi/Melayu, which ended up becoming the political center superseding Srivijaya after the eleventh century.30

The negeri of Melaka referred to the city where a part of the population was urban in nature and largely dependent on imported grain as opposed to its dependent rural hinterland.31 Like Srivijaya, Melaka was not a clearly defined and territorially bounded state, with the city as its capital. Instead, sovereignty resided in the monarch himself, the raja or sultan, ruling over his subjects/followers (rakyat). The principal asset of the ruler was his subjects, not land or territory. When a Portuguese force led by Afonso de Albuquerque attacked Melaka in 1511, for example, Albuquerque noted that “the Sultan drew himself from the city taking with him some Malay merchants, captains and governors of the land.”32 The defeated sultan, Mahmud Shah, went south of the peninsula and literally “opened a state” (buka negeri) there. What mattered, in other words, was not a state structure, but the survival of his person and dynastic lineage.

Due to the China connection, Melaka became the entrepôt, the chief collection center for pepper, marine and forest goods for the China trade, and for official tribute. In turn, Melaka became the chief distribution center for Chinese porcelain, textiles, and handicrafts.33 Besides China, another sector of the Melakan trade was the Indian Ocean connection, managed by Arab, Persian, and Indian traders, while the third sector comprised the archipelago itself, which supplied Melaka with the pepper, spices, foodstuffs, marine products, and slaves it needed.34 Melaka extended its influence throughout its umland through a mixture of force, political alliances through strategic marriages, and chiefly through its attraction as a global commercial entrepôt, a major node in a Muslim dominated network that stretched from Maluku to Java to Gujarat and Hormuz, Alexandria, and Venice. Unlike Srivijaya, which relied on coercion and control of some key items of trade, Melakan rulers sought less to coerce but rather to attract traders in a rather free market. A minimalist administration accommodated diverse interests not only in the city but also with its tributaries where the local heads of these Malay networks treated the Melaka Sultan as the primus inter pares.

In his study of what is often referred to as the kerajaan (kingdom) system of Malay polities such as Melaka, Milner identified the raja as the central institution that gave the subjects identity.35 Ruler-subject, patron-client relationships were the basis of the kerajaan. The system was characterized by fluidity and mobility, movement of rulers and subjects with no fixed territorial boundaries. There was no absolute ownership of land. Royal-elite relations were fragile and sometimes contested. To compensate for the rather fragile relations of kin and patron networks, subjects were exhorted to obedience and the Malay chronicles such as the Sejarah Melayu emphasized the daulat (sovereignty) of the raja and the paramountcy of loyalty to him. Treason (derhaka) was a major sin while the ruler in return was encouraged to consult the ministers and not to humiliate his subjects. The ruler’s position was however central where politics was a contest for the nama (rank/status) that individuals acquired from their raja. Raja-subject relations were manifested in elaborate court rituals where pomp and ceremony enhanced the aura, prowess, and charisma of the rulers.36 Thus on the one hand, while the basis of the ruler’s power was personal and fragile, the survival of the negeri was ensured as long as the ruler and his heirs lived since they could leave one locale and open a new state (buka negeri) with their followers, as the Melakan dynasty did after the Portuguese conquest of 1511.

The spread of Islam in the thirteenth century throughout the Malay world was important in shaping concepts of monarchical government in these insular polities. It gave to those rulers who converted to Islam a means of legitimizing their position and enhancing their claim to hereditary rule and international status. Islam was used to buttress royal power by introducing new formulae and theories on kingship. It introduced new codes of law and literacy and opened the way for elites and local traders to enter into new profitable Muslim commercial links/networks.

Islam was also important because it became part of Malay cultural identity, which defined Melakan prestige and created a shared culture. This plus the use of the Malay language, which became the lingua franca for most Malay/Muslim courts, created a network of relations and loyalties based on a shared language, culture, and Islam.37 The spread of Malay culture moved along archipelagic lanes from Melaka to well-beyond its immediate domains and this extended Malay culture to areas never before under substantial Srivijayan influence. Stories of those who spread Islam to Aceh and the Moluccas indicate that by the late fifteenth century links between Melaka and Java and the Moluccas had developed beyond mere trading connections to ties maintained by formal alliances and dynastic marriages. Lieberman asserts, “Melaka, no less than Ava, Pegu, Ayudhya, and Thang Long, became exemplar and patron of cultic and linguistic norms whose acceptance implied support for a central dynasty.”38 Reid argues that, when the “city-state” was dominant in the “the empty center” of Southeast Asia, a distinctive urban culture developed in the Malay idiom that was innovative, dynamic, and reminiscent of similar developments in the Mediterranean. These city-states were held together by a “tense kind of ‘peer-polity interaction,’”39 in which negeris needed each other as trading partners but also competed fiercely for trade and status.40 Reid argues that by the end of the period in which these city-states were either conquered or affected by European encroachments, they represented a crucial stage in Southeast Asian history because of their legacy in the area of religion and culture rather than for their political, military, and commercial structures.41

Melaka, like Srivijaya, lacked the central political and military structures needed to dominate or subjugate its far-flung vassals. The “empty center” of these states, in other words, could not be more dissimilar from most agrarian, land-based, densely populated empires, nor did they resemble other renowned Muslim empires such as the Ottomans or Mughals, whose governors and administrators exercised centralized control over their provinces.42 Even so, at the zenith of its power, Melaka, like Srivijaya, could be seen as an “imperial center” exerting political and commercial influence over its vassals and tributaries. Unlike Srivijaya, Melaka reached much farther afield as a global commercial entrepôt with links from Java to Venice. Melaka, as a Malay/Muslim center, managed to bind and integrate “an empty center” not with military or centralized political control but with a shared culture based on Malay language, culture, and Islam.

Increased demand from China after 1567 when Ming maritime bans were formally abolished, together with increased demand from Europe and from Muslim trading quarters, brought about an increase in exports of nutmeg and mace from Maluku by 500 percent. The volume of Southeast Asian pepper rose an estimated 550 percent, as did exports of tin, other spices, and forest and sea products.43 This period, which A. Reid termed the “Age of Commerce,” saw increased vitality and population growth in most cities in the archipelago. The economic stimuli caused by the expansion of cash-crop production and exports, urbanism, and increasing interventions by Portuguese, Dutch, and English companies in local polities encouraged rulers of insular Islamic monarchies to centralize and consolidate their rule, so that they might better control cash-crop production and partake in wealth creation in the face of increased European competition. This combination of external stimuli and local initiative would radically transform the city-states into more “absolutist” ones, paralleling European-style trajectories of political integration, militarization, centralization, and the tightening of center-periphery relations.44 These developments were exemplified by the sultanates of Aceh, Johor, Banten, Makassar, and Mataram. Could these more powerful Islamic monarchies be seen as having finally developed a “genuine empire-building” process comparable to those of their counterparts elsewhere in the Muslim world such as the Mughal and Ottoman empires?

Following the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511, the Melakan royal family retreated to the southernmost tip of the Malay Peninsula, where they sought to continue the Melakan line. When Sultan Mahmud Syah, the last ruler of Melaka, died in Kampar on the east coast of Sumatra between November 1527 and July 1528, he was succeeded by his son, Sultan Alauddin Riayat Syah. In the early 1530s Sultan Alauddin moved his residence to the valley of Johor River and became the first ruler of the Melakan dynasty to establish a permanent settlement in Johor. The “foundation” of the Kingdom of Johor was more a continuation than a fresh start in the history of the Malays of Melaka, so many features of the structures of power in the “new” Johor kingdom had their origins in the Melakan kingdom.45

The other polity that grew in power and emerged alongside Portuguese Melaka was Aceh, at the northern tip of Sumatra. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a peculiar balance among the three powers of Aceh, Johor, and Melaka became an important feature of the political and economic life in the Straits of Melaka.

The Beginnings of “Empire-Building” in Insular Southeast Asia? The Case of Aceh

The creation of the kingdom of “Aceh Dar al-Salam” began as a response to Portuguese incursions into the Straits from 1519 to 1524. Sultan Ali Mughayat Shah (r. 1516–30) drove the Portuguese from Pasai and united this port-city together with others such as Pidie and Lamri on the north coast of Sumatra. In 1520, the capital or royal center of the kingdom was located in the valley of the Aceh River itself, known as Aceh Besar, an area known for its deep harbor although it was not an important source of export production. Pepper, and later betel nut, was grown on the northern coast of Sumatra; pepper, camphor, gold, and other exports came from the ports of the west coast of the island; tin was exported from Perak on the Malay Peninsula. Aceh’s consistent policy was to dominate these regions politically, deny their produce to the rival Portuguese, and as far as possible direct all foreign trade through its capital. In his study of trade and power in Aceh, Reid identified three stages in the political development of the sultanate: (1) a great mercantile oligarchy up to 1589; (2) the period of royal absolutism (1589–1636); and (3) the decline of the crown and rise of the three sagi (supra-districts) up to 1700.46 This threefold division serves as a useful framework for examining whether the process of the establishment of the kingdom of Aceh (stage 1), its consolidation (stage 2), and its decline (stage 3) during the period between 1500 and 1700 reflect characteristics of empire-building in the Straits of Melaka.

The desire of many Malay Muslims to repel the Portuguese from the region provided an important impetus to Aceh’s effort to consolidate its position and to be recognized as the leading Malay power in the region. Ala’ad-din Ri’ayat Syah al-Kahar (r. 1539–71) also sought to defeat the Portuguese commercially, in addition to trying to drive them physically from the Straits of Melaka. Continuing his predecessor’s policies, he conquered Aru on the east coast of Sumatra and Pariaman on the west, establishing his sons as vassal rulers of these regions. He presided over the revival of the Muslim spice trade between his port and the Red Sea, which by the end of his reign was carrying as much as the Portuguese route. Following the death of al-Kahar, his son Ali Ri’ayat Syah (r. 1571–9) largely continued his policies, but Ali Ri’ayat’s death was followed by a decade of respite for the Portuguese as the kingdom passed to a succession of five weak rulers. As the powers of the throne declined, an elite mercantile class of orang kaya (“men of means”) came to hold sway over the kingdom. In 1589, Ala’ad-din Ri’ayat Syah Sayyid al-Mukammil, a descendant of the Dar al-Kamal dynasty that had ruled in the Aceh valley before its unification, regained the throne and ruled with a firm hand until 1604. He massacred a large number of leading orang kaya by poisoning them at a feast and centralized political and commercial power in his own hands such that no major Acehnese merchants remained except the Sultan himself. Al-Mukammil’s centralizing policy was carried to new heights by his grandson, Sultan Iskandar Muda (r. 1607–36), who ushered in a period of “absolutism” in Aceh and who also launched the largest military expedition against the Portuguese.

From Sultan Ala’ad-din al-Kahar to the reign of Iskandar Muda with the exception of the decade of five weak rulers (1579–89), Aceh initiated a series of about ten holy wars against Portuguese Melaka that finally culminated in 1629 with Aceh’s defeat and the loss of about 19,000 men.47 Just as Melaka sought to bolster its position against the Portuguese by establishing diplomatic, tributary, and commercial relations with China, Aceh also negotiated a series of diplomatic, commercial, and military alliances with other Muslim empires outside the region. Through the mediation of the governor of Egypt, for example, the Ottoman Empire agreed to send Ottoman and Abyssinian troops to help Al-Kahar. As a result, Mendes Pinto reported that the Portuguese faced an Acehnese army that included many soldiers from the Ottoman Empire, Cambay, Malabar, and Abyssinia.48 Al-Kahar sent a further mission to the Ottomans to ask for weapons for the struggle against the Portuguese, and sent other Acehnese ambassadors to the rulers of Bijapur, Calicut, and the Coromandel coast seeking assistance. From 1539 to 1569, the Ottomans supplied Aceh with artillery, gunners, military engineers, shipwrights, and elite troops who provided the Acehnese with military training. In 1570–71, Bijapur, Ahmadnegar (Gujarat), Calicut, and Aceh launched a concerted offensive against Portuguese possessions throughout the Indian Ocean.49 This was intended to escalate into a pan-Islamic alliance of the Ottoman Empire, Aceh and the Muslim states of South Asia against the Portuguese, but the planned joint campaign did not materialize and the Ottomans became distracted by events in the Red Sea theatre of war. Aside from the period of the 1560s when Aceh received some support from Johor, its initiatives against the Portuguese were generally not supported by the other Malay/Muslim polities as the latter viewed any campaign that might lead to Aceh’s territorial aggrandizement with suspicion. When Aceh sent envoys to Demak to ask for help against the Portuguese, for example, Demak was apparently so afraid of the insatiable ambition of the Sultan of Aceh that it put the Acehnese ambassadors to death.50

It was not lost on other states that Aceh’s military expeditions against the Portuguese were occurring against the backdrop of various measures intended to bring about the political, military, and economic consolidation of the Straits of Melaka under Acehnese auspices. From 1539 to 1621, for example, Aceh undertook a series of diplomatic and military offensives to subdue the Minangkabaus, Bataks, and other rival Malay polities in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula.51 During the reign of Iskandar Muda, Aceh extended her influence over the east and west coast of Sumatra to dominate pepper and gold exporting ports such as Pidir, Deli, Aru, Daya, Labu, Singkel, Barus, Batahan, Pasaman, Pariaman, Tiku, and Padang. Across the Straits on the Malay Peninsula, Iskandar Muda also conquered his main local rival, the Sultanate of Johor, in 1613, and seized control of the tin zones of Pahang (1617), Kedah (1619), and Perak (1620).52 Control over these areas enabled Iskandar Muda to raise an army of 40,000 men.53

In an Acehnese seventeenth-century chronicle, the Hikayat Aceh, the chronicler described Iskandar Muda as “subjecting” (mengempukan) and “enslaving” (hambakan) these other Malay polities. Clearly then, Sultan Iskandar Muda and his successor son-in-law, Sultan Iskandar Thani (r. 1637–41), saw themselves as the imperial center in relation to these conquered Malay states.54 Islam had been used by Melaka to develop concepts of monarchical government and to embark on a process of institutionalization of law codes and governance; Aceh’s rulers strengthened monarchy even further by adopting local, Islamic, Ottoman, and Persian notions of universal kingship and grandiose titles. Iskandar Muda was known as Mahkota Alam (“Crown of the Universe”), Johan Berdaulat (“Champion Sovereign”), Perkasa Alam (“Might of the Universe”), Khalifah Allah (“Caliph of Allah”), and Sayyidina al-Sultan (“Our Master, the Sultan”).55 In a letter to Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange, and Antonio van Diemen, Governor in Batavia, Sultan Iskandar Thani described himself as “Champion Sovereign, shadow of God on earth ... glittering like the sun, whose attributes are like the full moon ... who is king of kings, descendants of Iskandar Zulkarnain ... who owns many types of elephants, horses, gold,” and so on.56 It is interesting to note how in the Hikayat Aceh the concept of universal kingship was reconciled with the practical need to defer to the military power of Ottoman Turkey. In that text the (Ottoman) Sultan of Rum himself was credited with having declared that “at the present time” and by divine decree there were two great kings who shared the world: the king of Rum in the West and the king of Aceh in the East. These were then compared to the two great kings of yore: Solomon and Alexander the Great.57 The Sultans of Aceh certainly did not see themselves as mere kings of insular Southeast Asia.

According to Charles Boxer, the 1560s saw Aceh reemerging as the formidable eastern bastion of the Muslim counter-crusade against the Portuguese. Pepper propelled Aceh’s ascendancy in the sixteenth century as the sultanate succeeded Melaka to become the main Muslim commercial center supplying pepper to the Mediterranean market via the Red Sea.58 In order for Aceh to meet the economic challenges posed by its Portuguese and later Dutch and English rivals, it was crucial that the areas providing the sultanate with pepper and other commodities be reliably subservient or at least compliant with Acehnese plans. Any possible internal threats from the orang kaya also had to be prevented. Iskandar Muda and his successor Iskandar Thani therefore embarked on a series of measures to consolidate power and strengthen royal authority in Aceh. The privileges of the Acehnese orang kaya were substantially curtailed. They were not permitted to build fortified houses, or to keep cannons of their own. Any orang kaya who was late in answering the call to supply men for war was severely punished.59 A register was kept of firearms, and these had to be returned to the state once military campaigns were completed. Internal opponents were punished with immediate execution. Indeed, according to European accounts the orang kaya needed only to be wealthier and more popular than the sultan to incur their rulers’ wrath and risk death. Iskandar Muda is also credited with dividing the central territories of Aceh into mukim (subdistricts), which were later consolidated into larger administrative units.

Besides strengthening the position of the sultanate at its center, Iskandar Muda also tightened his control over Aceh’s vassals and sought to curtail local loyalties and identities. Royal princes, previously stationed in outlying areas as governors, for example, were replaced by officials directly responsible to the ruler. The sultan appointed these officials, enjoying the title of panglima (“commander”), every three years. They were required to report annually and were periodically inspected by the ruler’s representatives. Punishment for dereliction of duty was severe.60 To limit the local elite’s commercial power and to forestall Dutch monopolies, Iskandar Muda sought to monopolize trade by introducing the sultan’s right of preemption to purchase Indian textiles and to sell pepper. Europeans could not purchase gold and pepper in west-coast Sumatra without a license from him, while vassals of Aceh had to surrender 15 percent of their pepper, tin, and gold to the ruler and sell the rest to him at a price fixed by the sultan.61

Culturally, Aceh also succeeded Melaka to become the center of the “Malay world” (Alam Malayu). Aceh was well aware of this, and presented and saw itself as the leader of the Malay world. Malay continued to be the main lingua franca of the state, and the language of its court and literature. Aceh produced the largest corpus of Malay theological, historical, and literary works such as the Taj us-Salatin, Bustan us-Salatin, which were well known in other parts of the Malay world to the east. As L. Andaya has shown in his study, Aceh was more connected to the other Muslim powers “above the wind,” as could be seen in its Persian-Arab inflected Malay dialect and Ottoman-Mughal style palace organization.62 As the “veranda of Mecca” Aceh was influenced by teachings from Cairo, Mecca, and Yemen and it became the center for Sufi scholarship and Muslim networks that stretched to the eastern part of the Malay world.63 Compared to Srivijaya and Melaka, Aceh came closest to meeting European criteria of “empire” and its contacts with the Ottoman and Mughal empires provided Aceh with the bases of legitimacy, court rituals, political and military structures that made Aceh similar to these empires above the wind compared to its indigenous neighbors in the south.

Iskandar Muda’s and Thani’s centralizing, militarizing, and expansionist policies were not continued by their female successors who reigned from 1641 to 1699. The four sultanahs adopted a more decentralized policy and when Johor and Pahang began to act independently Sultanah Safiatuddin Shah (r. 1641–75) did not attempt to reassert Aceh’s overlordship over these states. In contrast to their male predecessors, the sultanahs also adopted a more consensual approach to the orang kaya based on power- and wealth-sharing with these male elites and an institutionalization of state apparatus. In the provinces, the sultanahs nurtured overlord-vassal relations through kinship loyalties, devolution of authority, and a sharing of resources. In Perak, for example, the sultanahs shared the profits of the tin trade with their orang kaya and with the local elites of Perak.64 Instead of waging holy wars against their European rivals, the sultanahs also sought an accommodation with the VOC and EIC by signing treaties with them and granting limited trade concessions.

Did these changes mean that Aceh’s development toward state consolidation and even empire-building had come to a halt? In contrast to the leadership style of Iskandar Muda, whose rule is deemed the “golden age” of Aceh by most scholars, the sultanahs have been seen as weak and Aceh was said to have declined by the end of female rule in 1699. I would argue otherwise, however. “Absolutism” in insular Southeast Asia was, by the very nature of conditions there, a fragile and contingent phenomenon, based more on the force of personality, wealth, and coercion of individual rulers, rather than on lasting institutions or rule of law that supported them. Iskandar Muda’s “absolutism,” for example, was in itself a function of his personality and also a reaction to the powers wielded by the orang kaya earlier.65 In insular Southeast Asia, however, where direct control was elusive and allegiances fluid, provincial leaders could still temper a strong ruler such as Iskandar Muda thanks to their control over much of the resources and armed forces of outlying territories.66 For example, when local elites on the west coast of Sumatra became unhappy with the trade conditions imposed on them by Iskandar Muda, they simply opted to change their allegiance from Aceh to the Dutch East India Company in Batavia.

While the sultanahs’ apparent retreat from the centralizing, militarizing, and expansionist style of their predecessors certainly limited royal power, their decentralized, more elastic, and fluid management of the elite and vassal states based on cultural and religious loyalties rather than military coercion was adaptive and more akin to the tried-and-true indigenous style of managing center-periphery relations that had been so successful for Srivijaya and Melaka. Far from leading to the decline of Aceh, such a change in strategy was critical in helping Aceh maintain its independence.

The Beginnings of “Empire-Building” in Insular Southeast Asia? The Case of Johor

The expansion of Aceh in the sixteenth century after the fall of Melaka in 1511 relegated Johor to a secondary role within the regional panorama. Especially after the crisis of 1613–15 when Johor was attacked and its population forcibly brought to Aceh, Johor was seen by Aceh as its vassal.67 It was only after the end of the expansionist rule of Iskandar Muda and the destruction of Portuguese power in Melaka that Johor began to pose as Aceh’s rival and an alternative center as the successor of Melaka. By 1641, Johor had lost some of the areas which had originally been dependencies of Melaka, though it still held sway over other dependencies such as Selangor, areas on the Kelang, Linggi, Siak, Kampar, Muar, and Batu Pahat Rivers, the islands of Karimun, the Riau-Lingga Archipelagos, and Singapore.

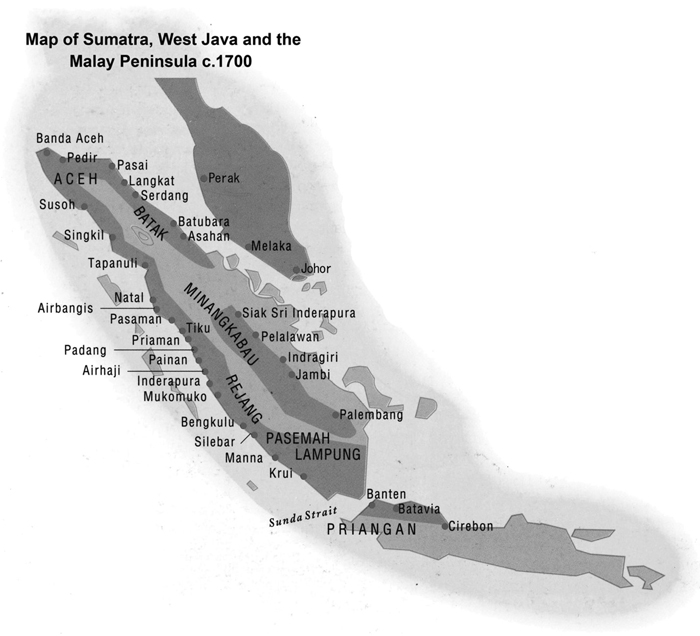

Over the course of the seventeenth century, Johor reasserted its authority on the east coast of Sumatra as far north as Deli, and over the kingdoms of Pahang and Terengganu on the east coast of the Malay Peninsula.68 Like Melaka, Johor was in no danger of dissolution so long as its ruler and dynasty survived. In the Malay Anals (Sejarah Melayu), the recurrent phrase “where there is sovereignty, there is gold” reflected the common belief that faithful subjects shared not merely in the material wealth of their sultan, but also in the glory and prestige of a ruler descended from an ancient and illustrious line. The possession of sakti, “the supernatural power associated with the gods,” placed the ruler in a sacred realm far above the common people and thus worthy of their veneration. The sakti or daulat (to use an alternative, Arabic-derived term) of a prince from Palembang, for example, would have been perpetuated among his descendants, the rulers of Muslim Melaka. As in Melaka and Aceh, the dual concepts of the ruler’s daulat (and the obedience that it demands from the subjects) and of derhaka, treason to one’s ruler as the greatest sin, underlined the central role of the ruler in Johor and in all Malay polities. In practice, however, the ruler of Johor was supported and at the same time limited by his chief ministers, namely, the laksamana (“admiral of all naval forces”) and the bendahara (variously translated as “prime minister,” “first minister,” or “vizier”). Despite the rivalries between royalty and nobility, and the apparent independence and authority exercised by some of the chief ministers, Leonard Andaya has argued that the rivalry between the factions led by the bendahara and the laksamana in the seventeenth century vividly illustrated that their position and power depended ultimately on the sanction of the ruler.69 Only with the murder of Sultan Mahmud Syah by his laksamana in 1699 was this power of the ruler undermined, since the Melakan lineage was broken and the throne was usurped by the family of the bendahara. The new Bendahara dynasty which came to power in 1699 was not able to maintain the authority and prestige of the Johor Sultanate, however, and it was finally forced to submit to the realities of the power structure in the kingdom by the Minangkabau invasion of 1718 (see Figure 8.1).

In addition to the ruler and the chief ministers, the Council of Nobles (orang kaya) was a third important component in the power structure of Johor. The principal orang kaya formed their own individual centers of power within the kingdom. In times of war they would assemble their men and lead them as a group in battle. The orang kaya were also essential figures in the international trade conducted in the ports of Johor under the system of patronage. In this system business transactions were left entirely in the hands of the traders, but the latter could not buy or sell anything without money provided by their patrons. For this vital service the patrons retained a substantial commission, sometimes amounting to 25 percent of the total money required by traders.70 Through this profitable system of trade, the orang kaya obtained the revenues necessary to acquire followers and slaves to serve them. These orang kaya proved to be a force capable of righting any imbalance in the exercise of power, as when they were ignored or abused by one ruler, they lent their assistance to a rival contender in order to improve their position within the kingdom. When they were courted, they responded favorably and contributed toward a successful working relationship with the ruler and the chief minister.

As in Srivijaya and Melaka, a principal component in the power structure of Johor was the orang laut. Because of their intense loyalty to the rulers of the Melaka dynasty, a relationship approximating that of a lord and his personal retainers, they were an effective counterforce to the strength of the orang kaya. The orang laut constituted about one-fourth of the military manpower of the kingdom. Since the size of a population was an important index of power in the Malay world, the orang laut played a decisive role in the politics of Johor.71 Their complete trust and loyalty to the Melaka-Johor ruler was not based merely on wealth but on blood line. As long as the rulers of the Melaka-Johor kingdoms could claim descent from the prince from Palembang, they could continue to enjoy the privileges and powers of kingship. However, their devotion to the Melaka-Johor ruling house suffered a shock with the regicide of 1699, which resulted in confusion within the ranks of the orang laut and culminated in the betrayal of the new dynasty in 1718 in favor of a pretender, the supposed son of the last Melaka dynastic line, Raja Kecil of Siak. Refusing to offer their total devotion to a new ruling family, but also unwilling to transfer their loyalty wholly to Raja Kecil, the orang laut vacillated between Riau-Johor and Siak, thereby weakening their impact in the affairs of these kingdoms.

While Iskandar Muda of Aceh centralized control by military and political coercion (a strategy that was reversed by his female successors), the center-periphery relations between Johor and its vassals were more varied in nature. On the east coast of Sumatra there were various systems of governance both patrimonial and feudal, which reflected the degree of control exercised from the center in the seventeenth century. The region of Indragiri on the western coast of Sumatra, for example, was governed through its own ruler who was, however, handpicked by the sultanate of Johor. This arrangement did not prove entirely satisfactory and led to some difficulties when Johor had to send expeditions to Indragiri to prop up an unpopular figure against someone more favored by the local population. Kampar, Siak, and Rokan (all in western Sumatra) were each governed by a syahbandar (“harbor master”), who was responsible to the chief minister of Johor. Since most of the gold and pepper produced in the interior of Sumatra came through these regions, they were much sought-after fiefs and were usually administered by the most powerful minister of Johor. Batu Bahara and Deli in eastern Sumatra acknowledged the overlordship of Johor but retained their own sultans. They exercised an independence of policy and were less responsive to the wishes of the center than most of the other territories. Once a year a Johor mission headed by a chief minister was sent to the outlying dependencies to collect tribute and receive the homage from the heads of governments.72

Johor’s authority over these vassal states was grounded more in its network of relations than in military coercion. The power of Johor was based on two essential pillars: the surviving network of vassals loyal to the sultanate’s heirs across the territories of the former dominions of Melaka and its direct domination over the coastal inhabitants of the Riau-Lingga archipelago, the orang laut, who constituted the heart of Johor’s maritime power.73 Hence, the fall of Melaka and the foundation of Johor did not constitute a major break with the past; the orang laut remained loyal to the lineage.74 The orang laut kept watch over the Straits of Melaka and Singapore and their labyrinth of canals, controlling maritime trade and human traffic in the Straits and protecting commerce at the service of the sultans of Johor.75 Another pillar of Johor’s power was the prestige that the sultanate enjoyed throughout the Malay World as the successor to Srivijaya and Melaka.76 The Portuguese recognized this preeminence, attributing to this sultanate a supremacy over other Muslim powers. The chronicles of Aceh, the Hikayat Aceh, on the other hand, denigrated the sultan of Johor as a mere Raja Selat (“Ruler of the Straits”). Toward the end of the seventeenth century, Johor regained authority over various regions of the Malay Peninsula (Pahang, Muar) and Sumatra (Siak, Kampar, Indragiri, Aru) apart from the Riau-Lingga archipelagos and diverse islands in the Straits, vassals lost to Aceh during the sixteenth century and the early decades of the seventeenth century.

Both Aceh and Johor realized that in order to meet the challenges posed first by the Portuguese and then by the Dutch and English, they needed to strengthen and increase their control of the region, both politically and commercially. The results were levels of centralization and militarization without precedent in the Malay world. Political consolidation was matched by a high degree of cultural coherence, anchored in the Malay language and Islam. However, Malay sultanates adopted different strategies to attain these goals. Aceh, under sultans al-Kahar to Iskandar Muda, was notable for its use of “holy wars” and military conquest to impose Acehnese authority on vassals. The more characteristic mechanism of control in Malay/Muslim polities, however, was to use “soft power” through the forging of a network of relations and loyalties. It is important to understand the reasons why the ruled were motivated to enter into such alliances and give their allegiance to aspiring imperial centers. The relationship between center and periphery could be protective rather than always exploitative, and the center could inspire confidence and loyalty rather than just fear. This type of relationship was nurtured by the female rulers in Aceh and to a certain extent by the sultans of Johor. In this regard, too much military and political centralization could actually limit the ability of states to maintain their hegemony over neighbors. The co-optation of local elites by offering them privileges and respecting local particularities (in other words a certain degree of decentralization and devolution of power to the periphery) would make the system more stable than maintaining an expensive, coercive, and absolute center.

Mainland/Island Southeast Asia Dichotomy: A Case Study of Success and Failure in the Empire Project?

Unlike other Muslim empires such as the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals, the history of the smaller archipelagic Malay/Muslim polities has never been seriously considered from the lens of empire-formation (with the exception perhaps of the more renowned Sultanate of Melaka). In his study of Malay kingdoms, for example, Milner conceded that Melaka was an empire and Aceh aspired to be one, but he also concluded that no other Malay state rose to that level. Important centers of power such as Pasai, Aru, Patani, and Johor were able to remain independent from European control, but did not manage to create large states or zones of power of their own. Malays did not even formally acknowledge a single, preeminent sovereign, since most Malay rajas had genealogies of comparable prestige and status.77 Malay polities were instead characterized by multiple centers, each chronically vying for a leadership role.

Victor Lieberman asserts that within Southeast Asia, mainland states such as Burma, Vietnam, and Thailand demonstrated a higher degree of state consolidation by the eighteenth century, moving toward empire-integration since the

economic centres within each empire had become too closely integrated to go their separate ways, because the memory of imperial success (however imperfect) inspired constant imitation; because local headmen, monks, literati and merchants all required an effective coordinating authority to regularize their own status and to validate their privileges; and because popular self-images and notions of moral regulation depended too heavily on the imperial project to permit its abandonment.78

However, movement toward centralization and integration in the form of the creation of “exemplary centres,”79 “absolutist” and “gunpowder states”80 in Aceh, Johor, Banten, and Makassar gave way instead, after the seventeenth century, to political and cultural fragmentation.81 Indeed, Barbara Andaya argues that the differences between island and mainland are reflected in the contemporary historiography of Southeast Asia. It is rare for chronicles in the island world to look beyond a dynasty or a specific cultural group.82 Between circa 1750 and 1850, commercial wealth contributed to another cycle of movement toward political consolidation and territorial expansion in Terrengganu, Kedah, Siak, Palembang, Bali, Lombok, especially in Riau-Johor, south-central Java, Sulu, and Aceh.83 However, Lieberman argues that by mainland standards all such revivals of archipelagic power were ephemeral.84

Both Victor Lieberman and Barbara Andaya assert that the move toward political and economic integration in the archipelago was halted by 1800. None of the “exemplary centers” such as Aceh and Johor survived into modern times and much of the island world in the mid-eighteenth century was in disarray.85 Lieberman therefore concluded that the nearest analogies within the Malay Archipelago to the emergent mainland empires of Southeast Asia were not the indigenous Malay-ruled states, but rather the Spanish and Dutch regimes in the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies. Between 1750 and 1850, the latter regimes promoted supra-local integration and defined the political and economic options, and in some cases, the religious identity, of commoners and elites alike.86

In explaining the differences between the archipelagic and continental states of Southeast Asia, both Lieberman and Andaya identified geography, cultural variation, and European intervention as critical factors. Certainly, the fragmented nature of island geography was less favorable to political centralization. Regional seas did not provide a sheltered avenue of communication between any aspiring political center and its scattered peripheries, nor any clear axis of internal integration The nodes of the archipelagic economy were both more numerous and more dispersed than the urban centers of the mainland, meaning that economic development could just as easily promote political devolution as integration. Most critically, poor soils throughout much of the archipelago and especially where Malays lived precluded the demographic densities that provided mainland states with a secure center of gravity.

Culturally, the idea of a charismatic-religious center based on the person of the primus inter pares contained within itself the seeds of fragmentation. Only a powerful center could maintain its position in the face of cumulative tensions induced by continuing efforts to tighten supervision of people and resources. Whenever the dominance of the primus inter pares was questioned, given the existence of multiple centers competing with each other, it was followed by a steady seepage of manpower away from the center to other royal competitors. In such a society, where rulers were heavily reliant on their people/followers to maintain their standing against potential opposition, any loss of manpower was serious, especially if the defection coincided with conflicts over succession or the sharing of power.

Increased European interventions in archipelagic political affairs between 1750 and 1850 highlighted precisely these weaknesses, as the Portuguese, Dutch, and English supported royal pretenders, wooed the allegiance of subject populations, and sought to play local rulers off against each other. Such interventions made political consolidation and regional trade integration even more difficult, and even when archipelagic states surmounted these difficulties they still struggled to recapture the momentum that had buoyed them during the earlier, golden era of Reid’s “Age of Commerce.”

In comparison with the empires of the mainland and the more standard definitions of “empire,” the states of insular Southeast Asia seem to fall considerably short of the mark. The Sultanate of Aceh under al-Kahar to Iskandar Thani would come the closest, and then only for a relatively brief period. If one were to shift from a narrow understanding of “empire”—one that presumes a dominant political and military center controlling an agrarian-based, densely populated land mass, with established (albeit contested) territorial borders—to a broader vision, then different understandings of “imperial centers,” forms of control, bases of legitimacy, geopolitical contexts, and historical trajectories become possible. In insular Southeast Asia, the mandala, umland model of administration focused on the control of people/manpower rather than territories, and the sea presented no obstacle to such claims of a sovereignty of primus inter pares. The Straits of Melaka connected the Acehnese and Johorese maritime, coastal dominions and the orang laut were more than sea-people but sea-soldiers acting in the service of their lords. Successful rajas attracted manpower and followers not by coercion but by their distribution of material largesse and by the glory of their daulat and lineage. In this model, reciprocal patron-client relations, respect for local authorities, and the devolution of political and commercial power provided surer bases for stability at the center than centralization, which too often provoked resistance. The dependence of these states on fluid, flexible relationships, soft-power, and the accommodation of local loyalties and identities thus did not mean that they were weak, fragmented, and in disarray. On the contrary, accommodation and the forging of diplomatic and political alliances with European powers helped both Johor and Aceh (under the sultanahs) to stave off political and economic decline in the seventeenth century and even to stage a modest revival.

Could empire-building take place only after state consolidation, and was political integration a necessary condition for empire-formation? Even entities that are widely accepted as empires expanded, contracted, and changed over time, demonstrating different strategies across time and space. Could not the fluid, looser, more elastic configurations that characterized center-periphery relations in insular maritime Southeast Asia still demonstrate features that were quintessentially imperial—albeit shaped by local variations, and on a local scale? Even if polities like Aceh and Johor did not possess the integrated military and political structures of the Ming, Ottoman, and Mughal empires, there still existed a clear, underlying political system within the archipelago, as Reid has argued in his study on city-states, based on the shared structures of the kerajaan system, the Malay language and literary culture, and Islam (with the notable exception of Buddhist Srivijaya).87

Of course, there were limits to this unity just as there were political tensions between monarchies within the kerajaan system. Islam, for example, could be both a source of unity and of division. On the one hand, the Muslim principalities of the archipelago signally failed to unite and present a common front against the infidel, despite much talk of a pan-Islamic jihad to eject the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish, and English. There is considerable evidence, on the other hand, to suggest that the ideal of uniting all Muslims under the leadership of a caliph exercised a strong appeal for the otherwise disunited Muslims of Southeast Asia, from at least the 1500s and continuing well into the nineteenth century.88 In the sixteenth century, the sultans of Aceh, Japara, Ternate, Grisek, and Johor all seemed ready to submit themselves to the Ottoman sultan/caliph—at least in the more limited, mandala sense of recognizing him as primus inter pares.89 From the seventeenth century to the colonial period, Islam would remain a source of inspiration and legitimation for ulama and Islamic reformers seeking to resist European colonialism. The indigenous monarchies and Malay language were used by Malay nationalists to resist the British and Dutch empires and to create new nation-states based on cultural nationalism. A modified and modernized version of the kerajaan system, embodying the close identification of Malayness, Islam, and the traditional hereditary monarchies, has survived down to the present in the form of Malaysia’s “Council of Rulers” (Majlis Raja-Raja), made up of the nine hereditary sultans of Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Negeri Sembilan, Pahan, Perak, Perlis, Selangor, and Terengganu.

The Malay/Muslim maritime polities discussed above thus deserve to be seriously studied in the effort to broaden and establish a more universal vocabulary of empire, placed within a global frame of reference. Scholars of Southeast Asia have provided enough evidence to show that “urbanization” and “city” and “state” formations in this region are comparable to Europe and other areas, albeit with local variation. If Srivijaya, Melaka, Aceh, and even Johor can be seen as “imperial centers” in their own right—influencing and even controlling, at the zenith of their power, ethnically diverse peripheral subject regions—then the search for “empire” here is not too far-fetched.

Notes

1Also known as the “Malay world,” a space dominated by peoples loosely identified by a combination of ethnicity, language, culture, and customs as Malay.

2Victor Lieberman states that the crisis of the thirteenth century brought disruption to loose “imperial constructs” which had presided in some sense over multiple ethno-linguistic groups, such as the decline of the Angkor Empire and of Srivijaya. Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Contexts, c.800–1830. Vol. 1: Integration on the Mainland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 25.

3Tony Day, Fluid Iron: State Formation in Southeast Asia (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002), pp. 283, 293.

4Lieberman, Strange Parallels, p. 25.

5A full literature review on state-formation in Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Period is beyond the scope of this chapter. See studies mentioned in fn. 2–3; other studies are by scholars such as A. Reid, Barbara Andaya, Leonard Andaya, Clifford Geertz, Stanley J. Tambiah, O. W. Wolters, Lance Castles, Jane Drakard, Anthony Milner, Herman Kulke, Henk Schulte Nordholt, Pierre- Manguin, John Miksic, and Derek Heng.

6Jan Wisseman-Christie, “State Formation in Early Maritime Southeast Asia,” Bijdragen tot de Taal- Land- en Volkenkunde 151, no. 2 (1995), 235–88.

7J. Kathirithamby-Wells, “Introduction,” in The Southeast Asian Port and Polity: Rise and Demise, ed. J. Kathirithamby-Wells and John Villiers (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1990), p. 2.

8Hermann Kulke, “‘Kadātuan Śrīvijaya’—Empire or Kraton of Śrīvijaya? A Reassessment of the Epigraphical Evidence,” Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient 80 (1993), 159–81, 164.

9Ibid., p. 170.

10Ibid., p. 171.

11Ibid., p. 172.

12Bennet Bronson, “Exchange at the Upstream and Downstream Ends,” in Economic Exchange and Social Interaction in Southeast Asia, ed. Karl Hutterer (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1977), pp. 39–52.

13O. W. Wolters, Fall of Srivijaya (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1970), pp. 9–10.

14O. W. Wolters, Early Indonesian Commerce (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1967), pp. 227, 242.

15Kathirithamby-Wells, The Southeast Asian Port and Polity, p. 2.

16Ibid., pp. 2–3.

17L. Y. Andaya, “The Structure of Power in Seventeenth Century Johor,” in Pre-colonial State Systems in Southeast Asia: The Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Bali-Lombok, South Celebes, ed. A. Reid and L. Castles (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch, Royal Asiatic Society, 1975), p. 8.

18O. W. Wolters, History, Culture, and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives, rev. ed. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 1999), pp. 18–19, 93–5.

19Kathirithamby-Wells, The Southeast Asian Port and Polity, p. 3.

20Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, Malay Peninsula (Leiden: Brill, 2002), pp. 238–40, 246, 254, 346.

21Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Vol. 2, p. 777.

22H. Kulke, “‘Kadātuan Śrīvijaya,’” p. 176.

23Anthony Reid, “Negeri: The Culture of Malay-Speaking City-States of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries,” in A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures, ed. M. H. Hansen (Copenhagen: C.A. Reitzels Forlag, 2000), pp. 417–29.

24Anthony Reid, Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680, vol. 2 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), pp. 203–14.

25Anthony Reid, “Trade and the Problem of Royal Power in Aceh. Three Stages: c. 1550–1700,” in Reid and Castles, eds, Pre-colonial State Systems in Southeast Asia, pp. 46–7.

26Anthony Reid, “Negeri,” pp. 418–19.

27Pierre-Yves Manguin, “The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries,” Moussons 5 (2002), 77.

28Ibid., 76.

29Ibid., 77.

30Ibid.

31Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Vol. 2, p. 802.

32Braz de Albuquerque, The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, vol. 3, ed. W. de Gray Birch (London, 1880), p. 129, quoted in A. Reid, “The Structure of Cities in Southeast Asia, Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries,” in Reid and Castles, eds, Pre-colonial State Systems in Southeast Asia, p. 244.

33M. A. P. Meilink-Roelofsz, Asian Trade and European Influence in the Indonesian Archipelago between 1500 and about 1630 (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, 1962), pp. 74–80.

34On Melaka’s trade, see ibid., chaps 3 and 4.

35A. C. Milner, Kerajaan: Malay Political Culture on the Eve of Colonial Rule (Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1982), p. 2.

36Ibid., p. 97.

37Ibid., p. 9.

38Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Vol. 2, p. 817.

39Concept by Renfrew and Cherry, Peer-Polity Interaction and Socio-political Change (New York: 1986). Quoted in Anthony Reid, “Negeri,” p. 427.

40Reid, “Negeri,” p. 427.

41Ibid.

42Suraiya Faroqhi, The Ottoman Empire and the World Around It (London: I.B. Tauris, 2007), pp. 76–7.

43Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Vol. 2, p. 819.

44Reid, “Negeri,” p. 427.

45Andaya, “The Structure of Power in Seventeenth Century Johor,” pp. 1–11.

46A. Reid, “Trade and the Problem of Royal Power in Aceh,” pp. 46–53.

47Tomé Pires, The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires, vol. I, ed. Armando Cortesão (London: Hakluyt Society, 1944), pp. 138–9.

48A. K. Dasgupta, “Aceh in Indonesian Trade and Politics, 1600–1641,” PhD dissertation, Cornell University, 1962, pp. 45–6.

49A. Reid, “Sixteenth Century Turkish Influence in Western Indonesia,” Journal of South East Asian History 10, no. 3 (1969), 406.

50Ibid., 405.

51Paulo Jorge de Sousa Pinto, The Portuguese and the Straits of Melaka 1575–1619: Power, Trade and Diplomacy (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2012), p. 82.

52Denys Lombard, Kerajaan Aceh: jaman Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607–1636), trans. Winarsih Arifin (Jakarta: Balai Pustaka, 1986), p. 132.

53Dasgupta, “Aceh in Indonesian Trade and Politics, 1600–1641,” p. 81.

54T. Iskandar (ed.), Hikayat Atjeh (s’.Gravenhage: Martnus Nijhoff, 1958), pp. 153, 171–5, 182.

55Sher Banu A. L. Khan, “Men of Prowess and Women of Piety: A Case Study of Aceh Dar al-Salam in the Seventeenth Century,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 44, no. 2 (2013), 204–25.

56Iskandar Thani’s letter to Antonio van Diemen, in J. A. van der Chijs et al. (ed.), Dagh-Register van Batavia, 1640–1682 (The Hague: M. Nijhoff, Batavia: G. Kolff & Co. 1887–1928), pp. 6–7. For a fuller account, see Sher Banu A. L. Khan, “Rule behind the Silk Curtain: The Sultanahs of Aceh, 1641–1699,” PhD dissertation, University of London, Queen Mary College, 2009.

57Iskandar, Hikayat Atjeh, pp. 161–7.

58Anthony Reid, An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and other Histories of Sumatra (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2005), p. 6. See also: Charles Boxer, “A Note of Portuguese Reactions to the Revival of the Red Sea Spice Trade and the Rise of Aceh, 1540–1600,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 3 (1969), 415–28.

59Barbara Andaya, “Political Development between the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” in The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Vol 1 from Early Times to c. 1800, ed. Nicholas Tarling (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p. 439.

60Ibid., p. 438.

61Dasgupta, “Aceh in Indonesian Trade and Politics, 1600–1641,” p. 115.

62L. Y. Andaya, Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka (Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), chap. 4. Note that “above the wind” was an expression used to describe people or places located west of the Straits of Malacca.

63Ibid., p. 847.

64Khan, “Men of Prowess and Women of Piety,” pp. 212–13.

65Reid, “Trade and the Problem of Royal Power in Aceh,” pp. 45–55. Also, J. Kathirithamby-Wells, “Restraints on the Development of Merchant Capitalism in Southeast Asia before c.1800,” in Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power and Belief, ed. Anthony Reid (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993), p. 125.

66Takeshi Ito, “The World of the Adat Aceh: A Historical study of the Sultanate of Aceh,” PhD dissertation, Australian National University, 1984, p. 62.

67De Sousa Pinto, The Portuguese and the Straits of Melaka 1575–1619, pp. 144–5.

68Andaya, “The Structure of Power in Seventeenth Century Johor,” p. 2.

69Ibid., p. 5.

70Ibid., p. 6.

71Ibid., p. 8.

72Ibid., p. 5.

73De Sousa Pinto, The Portuguese and the Straits of Melaka 1575–1619, p. 145.

74Ibid., p. 146.

75Ibid.

76Ibid., p. 147.

77Milner, Kerajaan, pp. 1–2.

78V. Lieberman, “Mainland-Archipelagic Parallels and Contrasts, c.1750–1850,” in The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900, ed. A. Reid (London: Macmillan Press, 1997), p. 30.

79Andaya, “Political Development between the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” p. 443.

80Anthony Reid, “Multi-state and Non-state Civilizations in Maritime Asia,” paper presented to the symposium “The Formation of the Great Civilizations: Contrasts and Parallels” of the Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study and Centre for Medieval Studies in Bergen, held in Upsalla, Sweden, 2008, p. 9.

81Lieberman, “Mainland-Archipelagic Parallels and Contrasts,” p. 27.

82Andaya, “Political Development between the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” pp. 454–5.

83According to A. Reid, Southeast Asia reestablished itself as the overwhelmingly dominant source of the world’s pepper. From little more than 6,000 tons a year in the 1780s, Southeast Asian exports were estimated to rise significantly. This increase took place almost entirely in independent states—Aceh, Siam, Riau-Johor, Brunei, Deli, and Langkat. The cash income it generated served to commercialize their societies, and in some cases to strengthen their states. A. Reid, “A New Phase of Commercial Expansion in Southeast Asia, 1760–1840,” in The Last Stand of Asian Autonomies: Responses to Modernity in the Diverse States of Southeast Asia and Korea, 1750–1900, ed. A. Reid (London: Macmillan Press, 1997), p. 73.

84Lieberman, “Mainland-Archipelagic Parallels and Contrasts,” p. 42.

85By the early 1800s, new dynasties ruled in Burma, Siam, and Vietnam; in the island world Banten and Makassar had both lost their status as independent entrepôts, Mataram was divided into two, and Aceh had been torn by two generations of civil strife. See B. Andaya, “Political Development between the Sixteenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” p. 445.

86Lieberman, “Mainland-Archipelagic Parallels and Contrasts,” p. 48.

87Reid, “Negeri,” p. 419.

88Reid, “Sixteenth Century Turkish Influence in Western Indonesia,” p. 408.

89The Muslim states in Southeast Asia that appeared most susceptible to the pan-Islamic ideal were those that participated in the Muslim spice trade from Ternate through Java and Aceh to the West. Consequently, they shared the international currents of the Muslim world. M. A. P. Meilink-Roelofsz, in A. Reid, “Sixteenth Century Turkish Influence in Western Indonesia,” Journal of Southeast Asian History 10, no. 3 (1969), 408–409.