INTRODUCTION

ALL THAT GLITTERS

“The flames of a new economic evolution run around us, and we turn to find that competition has killed competition, that corporations are grown greater than the State and have bred individuals greater than themselves, and that the naked issue of our time is with property becoming the master instead of servant, property in many necessaries of life becoming monopoly of the necessaries of life. … Our industry is a fight of every man for himself. The prize we give the fittest is monopoly of the necessaries of life, and we leave these winners of the powers of life and death to wield them over us by the same ‘self-interest’ with which they took them from us.”

In 1890, 73 percent of America’s wealth was held by the top 10 percent of the population. In 2013 (per data released by the Congressional Budget Office in 2016), the top 10 percent of families held 76 percent of total wealth. As Mark Twain is often credited with having said, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”2 Googling the phrase “new gilded age” on December 26, 2016, returned “about 9,040,000 results,” including the farewell speech of retiring Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, who left office warning of “a new gilded age.”3

Many of today’s economists and historians believe they have found a kind of handbook of the new gilded age. It is Capital in the Twenty-First Century (English edition, 2014) by French economist Thomas Piketty, a work the Nobel laureate economist Paul Krugman calls a “magnificent, sweeping meditation on [wealth] inequality.”4 Piketty argues that when the rate of return of capital is greater than rate of economic growth, concentration of wealth results. A nearly identical concentration occurred during the post–Civil War nineteenth century and during the last quarter of the twentieth century into the opening of the twenty-first. The numbers support the assertion that we have both a First and a Second Gilded Age. Perhaps by understanding the First, we can understand and—as a democracy—more effectively manage the Second. Perhaps.

IF PIKETTY’S CAPITAL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY is the book of the New or Second Gilded Age, its counterpart in the original Gilded Age—the American period between the end of the Civil War and the dawn of the twentieth century—is perhaps more importantly remembered for being an eponym of the period itself: an 1873 novel written by Mark Twain in collaboration with the journalist-editor Charles Dudley Warner, titled The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. Twain borrowed that title from one of William Shakespeare’s least-read and least-performed plays, The Life and Death of King John, based on the life of John, king of England (1166–1216), who was forced by his kingdom’s rebellious barons to guarantee them certain legal rights as set out in the Magna Carta. Act 4, Scene 2 begins with the king pleased after commanding a second coronation to force his barons to swear their allegiance anew. One baron, Lord Salisbury, compares this to a brief catalog of other superfluous and extravagant acts:

The original cover of the 1873 satirical novel by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner that gave the era its name.

To gild refined gold, to paint the lily,

To throw a perfume on the violet,

To smooth the ice, or add another hue

Unto the rainbow, or with taper-light

To seek the beauteous eye of heaven to garnish,

Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.

Thus Twain and Warner saw their own era—an epoch of excess, of consumption not merely conspicuous but pornographic, as a “gilded age.” It was an age of robber barons and political bosses; of obscene wealth acquired and disposed of in total disregard to “how the other half lives”; an age of industrial expansion at the expense of the land; an age of American imperial adventurism culminating in the Spanish-American War, annexation of the Philippines, and annexation of Hawaii, all in 1898. Most of all, Twain, Warner, and many others regarded the Gilded Age as an amoral epoch of exuberant political cynicism and chronic political mediocrity. As Senator and Republican National Committee Chairman Mark Hanna (R-Ohio) remarked in 1895, “There are two things that are important in politics. The first is money and I can’t remember what the second one is.”5

Having elected in 2016 a combination magnate and reality television star to the presidency—especially one whose signature show, The Apprentice, embodied the social Darwinism Andrew Carnegie defined in his 1889 essay “Wealth” (see page 86)—Americans may be forgiven for seeing the nineteenth-century Gilded Age through a twenty-first-century lens. Both Gilded Ages are steeped in the same lily-gilding self-indulgence of what reality TV pioneer Robin Leach (host of the 1980s Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous) called “champagne wishes and caviar dreams.”6 But to go no further than visions of bubbly and roe is to do great injustice at least to the original Gilded Age.

True, Twain and Warner’s novel is about the greed, excess, and corruption in post–Civil War America. True, also, is the hint that the “Gilded Age” was something of a pun on “Guilty Age,” a period of American history criminal at its core and steeped in original sin. There is also the notion that it was an era marked by stark contrasts between insiders and outsiders and populated by a profusion of “guilds,” as it were—monopolies, crony-capitalist cartels, political parties, labor unions, and other special interest groups, including lodges, secret societies, and a host of reform organizations. Those who could not identify themselves with any particular “guild” were the outsiders, the masses, the feckless victims.

Finally, it is also true that the most obvious connotation of a “gilded age” is that it must be a much-degraded imitation of a true “golden age.” For Twain and Warner, the robber baron capitalist was a Midas whose touch was so shallow that it produced not solid gold but only a thin veneer barely covering the rot and corruption that had spawned it.

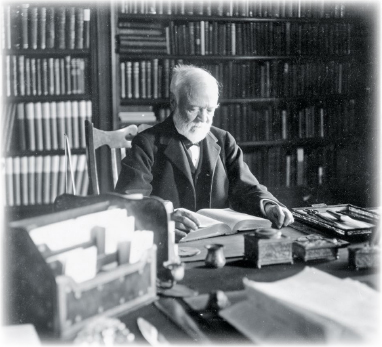

Andrew Carnegie was an impoverished child laborer in Scotland who became a ruthless industrialist in America. Having made his fortune, he gave most of it away to finance works for the public good. “The man who dies rich,” he wrote, “dies disgraced.”

Twain and Warner were not mistaken about the age they named. But they hardly told the whole story. Pursue the metaphor of a gilded age further and you will find that, whatever its symbolic and moral implications, gilding is an artificial process, a means of transforming the world through human invention, industry, artifice, and will. In this sense, America’s “Gilded Age” was an era of unprecedented creativity, not confined to a few extraordinary geniuses as in the Renaissance—an era popularly seen as a true golden age—but creativity disseminated to a burgeoning new American middle class in a kind of manufactured utopia, a demi-Eden predicted in the dazzlingly optimistic Centennial Exposition of 1876 (which we will cover in chapter 1) and in the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 (chapter 15), an even more dazzling display.

In the chapters that follow, we will neglect none of the lurid negatives of post–Civil War America, but we will also celebrate the positives, the myriad inspirations from which our own beleaguered and materially unequal age may draw inspiration.

“America’s ‘Gilded Age’ was an era of unprecedented creativity, not confined to a few extraordinary geniuses as in the Renaissance.”

WAR IS USUALLY RUINOUS TO PEOPLES AND NATIONS, especially civil war, but the bloody conflict between the American North and South from 1861 to 1865 made fortunes and laid the foundation for even more fortunes to come. Although it brought devastation to the South, the war rapidly accelerated industrial development in the North, and it occasioned two great national initiatives. One was the opening of public lands in the trans-Mississippi West to settlement and development by the Homestead Act of 1862, and the other was the federally subsidized building of a transcontinental railroad by the Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1863. All three pieces of legislation were demonstrations of bold faith in a nation torn apart by the biggest, costliest, bloodiest war in its history. The Homestead Act affirmed the American dream of property ownership in what white Americans thought of as “virgin land,” quite disregarding the Native Americans’ age-old residence in the West. The Homestead Act also encouraged foreign, specifically European, immigration to the United States, and it opened up vast new markets for the fruits of American invention and industry.

As the Homestead Act began the transformation of the United States into a great consumer economy, the building of the transcontinental railroads, enabled by the legislation of 1862 and 1863, made western expansion practical, even as it stimulated American industrialization—which, by the 1870s, pulled far ahead of the original epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, Great Britain. The American railroads spawned many heavy industries and created a vast demand for coal that expanded coal mining, especially in the Far West.

Western settlement and western railroads drew domestic as well as international investments in American business. New York was added to London and Paris as a global capital of finance and soon eclipsed both European cities in this regard. Indeed, while America grew as an industrial giant, its growth as a center of capitalism—investment in industry, real estate, and banking—began to overshadow even manufacturing, mining, and railroad building.

“The business of America is business,” President Calvin Coolidge would say in the 1920s. But it was much earlier, during the final quarter of the nineteenth century, that the business of American business had become, quite simply, wealth. This meant that “building” businesses was something more than a matter of brick and mortar. As great wealth became increasingly concentrated in a relatively few families during the Gilded Age, so corporations began to coalesce into massive and monopolistic “trusts”, especially in the petroleum, steel, meat, sugar, and farm machinery sectors. The largest of these trusts were not only horizontal—a Standard Oil, for instance, gobbled up many smaller oil companies—but vertical as well. Standard Oil’s John D. Rockefeller came to control the extraction, refining, transportation, and retail distribution of petroleum products, and his friend Andrew Carnegie, founder of Carnegie Steel, not only operated steel mills, but also owned the iron mines that fed them and the coal mines that fed the ovens, which processed the coal into coke to fuel the mill furnaces. Carnegie also invested in research and development to create advanced steel-making techniques, which were disseminated to Carnegie Steel managers and employees through classes conducted at a Carnegie industrial institute.

The great capitalists not only revolutionized the structure of corporations, they redesigned work itself. At the lower levels, factory workers were subject to training in efficiency, and their labor was closely integrated with specialized machinery, to which they were effectively subordinated. The era of the unskilled manual laborer gave way to the trained machine tender, even as the era of the craftsman gave way to the semiskilled factory worker. A new class of middle-management employees developed as well, many of them trained in engineering colleges, which began to appear across the country. America became a center of innovation and led the world in the creation of patents.

Dubbed the “Smoky City,” Pittsburgh was the center of the burgeoning American steel industry during the Gilded Age. This stereograph from c. 1905 shows a plant along the Monongahela River.

As the American economy grew during the 1870s and 1880s at the fastest rate in its history, the so-called robber barons7 ruled over the working class sometimes ruthlessly, sometimes paternalistically, and, often, even philanthropically. Men like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Leland Stanford, ruthless in business, used a large portion of their wealth to finance vast philanthropic endeavors, including centers for medical research, hospitals, public museums and libraries, universities, opera houses, and other noble institutions. Yet they never abandoned the social Darwinism of nineteenth-century English philosopher Herbert Spencer, who transferred Charles Darwin’s concept of the “survival of the fittest” from the realm of biological evolution to that of social development. Capitalism, Spencer argued, winnowed out the socially weak and elevated the socially strong, thereby justifying social stratification and inequality of wealth distribution.

The rise of the capitalist class did not go unchallenged. The Gilded Age saw the rapid development of large labor unions, beginning with the Knights of Labor, established in 1869. Strikes were frequent and sometimes violent, with violence directed by strikers against employers and, even more viciously, by employers against strikers. In 1886, a labor demonstration in Chicago’s Haymarket Square was bombed, killing seven police officers and four demonstrators, and wounding sixty other people. On June 26, 1892, Andrew Carnegie’s Homestead Steelworks in Pennsylvania was struck by workers protesting a wage cut. Ten days later, on July 6, a battle erupted between the strikers and Pinkerton guards hired by the company. Ten strikers and three Pinkerton operatives were killed, prompting Pennsylvania’s governor to call out the state militia. The strike dragged on until November 20. On May 11, 1894, workers at the Pullman Palace Sleeping Car factory in Chicago went on strike to protest cuts wage cuts that had been made without reductions in rents at company-owned housing. Eugene V. Debs, president of the American Railway Union, called for a boycott on trains carrying Pullman cars on June 26, and violence related to the strike and the boycott resulted in some thirty deaths and fifty-seven injuries.

Along with strikes, Progressive activists and politicians moved to improve conditions for workers, increase wages, and regulate or eliminate child labor. In the meantime, immigration, which had been encouraged by both political and business leaders to stimulate westward expansion, was becoming an increasingly contentious political and economic issue. Workers were concerned that immigrant labor would “steal” their jobs by undercutting their salary demands. Labor interests lobbied for restrictions and quotas on immigration, even as many capitalists lobbied for liberalized immigration policies. In the big cities, the influx of immigrant labor led to the construction of cheap tenement apartment buildings, which, on the one hand, created culturally diverse and intellectually rich communities while, on the other, resulted in the development of unhealthy and sometimes crime-ridden slums.

Racial and ethnic discrimination became major issues in American life. Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants were often targeted for discrimination, as were African Americans. In the South, the end of post–Civil War Reconstruction in 1876 (see chapter 10), brought a racist backlash against freed slaves and their descendants, ranging from employment restrictions that created a permanent black underclass in the South to outright terrorism, as practiced by such groups as the Ku Klux Klan. Many African American working men and families migrated to the cities and factory towns of the North, where racial segregation was not decreed by law, but was nonetheless a fact of life.

The Carnegie Steel plant at Homestead, Pennsylvania, was the site of a labor lockout and strike that turned into a bloody battle between strikers and Carnegie’s Pinkerton guards in 1892.

The clashing interests of wealthy capitalists and struggling workers reshaped American politics, promoting both audacious corruption—which reached its height during the two-term administration of Ulysses S. Grant (1869–77)—and the ambitious reform initiatives of the Progressive movement. In the cities, machine government, run by political bosses, became rampant as the “spoils system” exerted a powerful hold on state and local governments. The bosses curried favor and exerted control by rewarding their faithful with lucrative government positions and government contracts.

On the national level, the spoils system expressed itself in special interest lobbying and in political patronage. Paralleling this was the emergence of what many have called ethnocultural politics: party adhesion based on ethnic, immigrant, religious, and racial affiliation or origin. In 1891, the People’s Party—sometimes called the Populist Party—was founded in Cincinnati, Ohio, mainly as an agricultural third party aligned against the two major political parties, the Republicans and Democrats. On July 4, 1892, the party nominated former Union general James Baird Weaver, an Iowan, for president, under a banner proclaiming, “We Do Not Ask for Sympathy or Pity. We Ask for Justice.” Four years later, the Populists endorsed Democratic agrarian candidate William Jennings Bryan, who spoke against the monetary gold standard and in favor of the coinage of silver in a move to increase the money supply and free up credit for farmers. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold,” he declared on July 7, 1896, to the delegates assembled at the Democratic National Convention. Bryan was defeated for the presidency by Republican William McKinley; however, the Populists would be replaced by the Progressive Party, which, in 1912, would nominate Theodore Roosevelt as its candidate. Before the Gilded Age came to an end, both Populism and Progressivism emerged as important forces challenging the political status quo.

“We Do Not Ask for Sympathy or Pity. We Ask for Justice.”

THE GILDED AGE SAW THE URBANIZATION OF AMERICA, but it also created a massive expansion of farming. Between 1860 and 1905, the number of American farms increased from two million to six million and the number of people living on farms during that time from ten million to thirty-one million.8 Unfortunately, however, farmers were subject to the whipsaw effect of agricultural booms and busts, especially when demand for and prices of wheat and cotton would skyrocket, only to plummet during the numerous crises of economic instability to which the nation was subject during this period. Farmers’ troubles were compounded by the predatory freight pricing of rail carriers, who fixed prices among themselves to avoid competition and thereby were often in a position to gouge farmers in the regions served by a single railroad. Farmers responded by embracing mechanization of farming, which increased productivity while reducing costs, and, in 1867, by organizing themselves into the politically powerful Grange movement (a fraternal organization that still exists on a smaller scale today). The Grange successfully pressured Congress for passage of so-called Granger Laws, which set limits on railroad and warehouse fees. On February 4, 1887, Congress enacted the most sweeping piece of Gilded Age regulatory legislation, the Interstate Commerce Act, which required railroads to charge reasonable rates and barred them from granting “preferred” (that is, big and powerful) customers reduced rates.

This Puck magazine chromolithograph depicts Populist apostle William Jennings Bryan, who, having electrified the Democratic National Convention with his “Cross of Gold” speech, won that party’s 1896 presidential nomination, only to be defeated by Republican William McKinley.

Indian chiefs and U.S. officials meet at the Pine Ridge Reservation on January 16, 1891, in the aftermath of the Wounded Knee Massacre of December 29, 1890. Among those pictured here are Crow Dog and Short Bull, standing second and third from the left; standing sixth from the left is William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was followed by the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, the Timber Culture Act of 1873, the land rushes in Oklahoma in 1889 and the 1890s, and the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909. Together with the expansion of the transcontinental rail lines, these accelerated white settlement in the West, triggering the so-called Indian wars, beginning in the late 1860s and culminating in the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota on December 29, 1890.

Along with abuse of African Americans in the South and the urban North, the war against and the displacement of Native Americans in the West are tragic and shameful aspects too often glossed over in discussions of the Gilded Age, which typically focus on conflicts between labor and capital. In fact, the injustices committed against African Americans, Native Americans, farmers, and labor were all intimately related to the economic growth that drove the Gilded Age. It was this explosive growth that also contributed to the rise of American imperialism, yet another dimension of the Gilded Age.

The combined energy of capital and political ambition sought out new outlets for profit and power in the 1890s. On July 12, 1893, an obscure history professor from the University of Wisconsin rose to deliver a paper at the Art Institute of Chicago during the World Columbian Exposition. Based on his interpretation of the 1890 census, in which the United States Bureau of the Census had decided that it could no longer designate the boundaries of a western frontier by means of population statistics, Professor Frederick Jackson Turner announced that the frontier, the source of so much of America’s distinctive identity, was now, in effect, statistically “closed.” Although uniformly rejected by modern historians as a distorted and inadequate explanation of the early modern history of the American West, Turner’s “frontier thesis,” as it was called, not only made him America’s foremost historian at the close of the nineteenth century, it profoundly influenced the way most Americans thought of themselves. It explained much about the popular mythology of the American West, and it suggests a reason why American political and business leaders turned from the West to lands beyond the North American continent to expand both nation and markets.

“What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks,” Turner told his Chicago audience, “breaking the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities, that, and more, the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States.” He continued: “And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.” He argued that the expansive character of American life—“that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism … that buoyancy and exuberance which comes from freedom”—created by the frontier would not end with its closing. Instead, he asserted, “American energy will continually demand a wider field of exercise.”9

Some of Turner’s fellow historians called his “frontier thesis” the “safety valve” thesis. Anyone living in the Gilded Age, an era driven by steam power, would have appreciated the metaphor. Steam was a tremendous force—indispensably useful when properly managed, but catastrophically explosive when it was not. For this reason, all steam devices were equipped with a safety valve to relieve pent-up pressure before it became dangerous. In Turner’s formulation, the frontier had served as a “safety valve” for the relentless energy of Americans. Now that this outlet was closed, where would the nation’s expansionist drive find release? Turner predicted that Americans would be impelled to undertake imperialist ventures overseas. Whether or not the frontier/safety valve thesis truly explains why the 1890s were indeed an era of American imperialism, the Spanish-American War (1898), the annexation of Hawaii (1898), the Hay-Bunau-Varilla (Panama Canal Zone) Treaty (1903), and the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine (1904) pushed American national interest beyond U.S. borders. This, too, is a legacy of the Gilded Age.

ABOUT NINE O’CLOCK ON THE EVENING OF SUNDAY, OCTOBER 8, 1871, fire broke out in or near a barn belonging to the O’Leary family on Chicago’s Near South Side. With astonishing speed, a conflagration tore through the city’s masses of wood-frame buildings, and by Tuesday, almost four square miles (10 km2) of the city lay in charred ruins, at least 300 lives had been lost, and 100,000 Chicagoans out of a population of some 300,000 were homeless.

In at least one way, the Great Chicago Fire was the best thing that ever happened to a city widely condemned as a blighted example of careless, ramshackle growth, spurred by the industrialization of the Midwest. A “Great Rebuilding” followed the fire, and, fortunately for the city and the nation, Chicago drew on a cadre of remarkably forward-looking architects, including William Le Baron Jenney, John Wellborn Root, Louis Sullivan, and Dankmar Adler. These and others introduced the skyscraper, a distinctive American building type, to world architecture, along with the radically innovative steel-cage construction that made it possible. What is more, the work of these individuals was set in the context of a great modern urban-design plan masterminded by Daniel Burnham. Chicago thus became a showcase of unique and uniquely influential American architecture, arrayed along the magnificent shore of Lake Michigan.

A phoenix risen from the ashes, post-fire Chicago came to symbolize the creative energy that was as much a part of the Gilded Age as all its excess, conflict, and corruption. The innovative buildings were of a piece with American innovation in areas of applied technology. Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone in 1876 and Thomas Edison filed for a patent on his incandescent electric light in 1879 (awarded in 1880). From these developed two national and global economic and technological networks, the telephonic communication network and the electrical power grid. Other inventors, including George Westinghouse and Nikola Tesla, further established electricity as the basis of a whole new mode of civilization, and both industry and markets grew in ways unimagined before the Civil War.

A Gilded Age vision of the American city as a New World utopia—the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago. Most of the magnificent structures were built of “staff,” a cheap concoction of plaster of Paris, cement, and a few other materials intended for the erection of temporary buildings and monuments.

There was an explosion of commerce in the high-tech Gilded Age, and consumerism rose as the principal driver of the American economy. Great department stores opened in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, along with humbler “five-and-dime” stores in towns and cities across the nation. Rural America was served by new catalog-based mail-order enterprises introduced by Montgomery Ward (1872) and Richard Warren Sears (1888). Despite growing income inequality, consumerism in the Gilded Age was the product of a rising middle class, and it shaped both personal economic aspirations and politics. The mass of Americans had entered the Gilded Age as seekers of nothing more or less than the means of sustenance. Before they emerged from the era, they were dedicated consumers. As the nation crossed the threshold of the twentieth century, the products and the iconography of corporate America vied for mindshare with the traditional patriotic symbols of the republic itself.

This new American materialism was reflected in the art, literature, and philosophy of the era. In American literature, the decade prior to the Civil War—the 1850s—is often called the American Renaissance. It was an intense literary period that saw the rise of some of the nation’s greatest authors and poets, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, and Emily Dickinson. Although they grappled with the realities of American life and life in general, they shared a certain romantic, often idealistic and even spiritual vision. The subsequent generation of post–Civil War authors, who came to dominate the Gilded Age, had a harder edge to their outlook. Such writers as Mark Twain—who gave the era its name—William Dean Howells, Henry James, Edith Wharton, and Hamlin Garland were unapologetically immersed in the material realities around them. Those who entered the literary arena toward the end of the era, including Stephen Crane, Kate Chopin, Frank Norris, and Theodore Dreiser, took the materialism to a more radical level, developing a distinctly American version of what such novelists as Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert, and Emile Zola had created in France. It was called naturalism, and it brought to literary realism the cool, sometimes brutal, rigor of scientific observation. Whereas the pre–Civil War generation had focused on spirit, the first writers of the Gilded Age concentrated on the material surface of things, and the later writers went even further. They clawed beneath the surface in search of the operation of natural law, a force indifferent to the sensibilities and sufferings of humanity. These writers produced memorable, dynamic, amoral, and even shocking characters as they delved into the phenomena of corruption, vice, disease, poverty, racism, and social violence.

Mark Twain, second from left, celebrates his seventieth birthday in 1905 at New York’s famed Delmonico’s restaurant. With him (from left) are children’s book author Kate Douglas Wiggin, his close friend Reverend Joseph Twichell, Canadian poet Bliss Carmen, authors Ruth Stuart and Mary Wilkins Freeman, author Henry M. Alden, and industrialist Henry H. Rogers.

The intellectually and morally challenging aspects of Gilded Age literature were matched by the emergence of a fresh vision in American visual arts. Painters such as John Singer Sargent specialized in the splendors of high society, whereas Mary Cassatt absorbed French Impressionist influences and turned them into a unique vision of domesticity. Others took visual art in bolder directions. Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer developed intense, even dark, visions of the world around them with an aesthetic that sometimes paralleled the literary naturalists. James McNeill Whistler had ideas different from Singer and Cassatt as well as from Eakins and Homer. He sought to reclaim art for itself—“art for art’s sake”—by producing what he called “compositions,” which were to be appreciated less as renderings of external reality than as new creations that deserved to take their place in the world in their own right and on their own merits. Whistler opened the door, albeit just a crack, to abstract as well as the nonrepresentational art of the mid- and late twentieth century.

The technology, enterprise, architecture, literature, and visual art of the Gilded Age created a legacy of a new and distinctly American “realism.” It has proved to be enduring and deep, rather than superficial or “gilded.” For all the undeniable moral and physical ugliness of the era, the period from the end of the Civil War to the opening of the twentieth century produced some of the greatest intellectual and aesthetic monuments of American civilization. We need to appreciate these works, just as we need to accept that it was the injustice, exploitation, excess, and corruption of the Gilded Age that provoked and incited a generation of American reformers to launch the Progressive movement.

Acknowledge though we must that the Gilded Age is justifiably synonymous with political corruption, we must further recognize that this view, by itself, is far too simplistic and far too narrow. Still, there is truth in it, and the greatest political scandal of the many that characterized the era was the “stolen election” of 1876, in which Democratic Party leadership agreed to concede the disputed outcome of the presidential contest between Samuel Tilden and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for Hayes’s pledge to end the regime of post–Civil War Reconstruction throughout the South. Duly installed in the White House in 1877, Hayes kept his pledge, and African Americans were thereby relegated to persecution and second-class citizenship throughout the former Confederacy. While this situation endured until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the Gilded Age itself produced foundational reforms in racial justice, including ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) and the Fifteenth Amendment (1870), as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1875 and the founding of the Tuskegee Institute in 1881.

The Gilded Age also saw the revolt of many American women against social marginalization and forcible confinement to the domestic sphere. This rebellion laid the foundation for what would emerge as the “women’s movement” nearly a hundred years later. Indeed, the last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the rise of what some have called a “maternal commonwealth” of female reformers and female-led reforms. These ranged from the full flowering of the temperance movement, to the ongoing struggle for women’s voting and property rights, to relief and uplift of the poor. The latter was embodied most dramatically by the settlement house movement organized by Jane Addams, who founded Chicago’s Hull House in 1889. The maternal commonwealth unfolded within the context of the changing roles of women of all socioeconomic levels during the Gilded Age. Although feminist leadership was drawn chiefly from the upper, upper-middle, and so-called educated classes during the era, the rank and file of the growing movement was drawn from laboring women, both married and single.

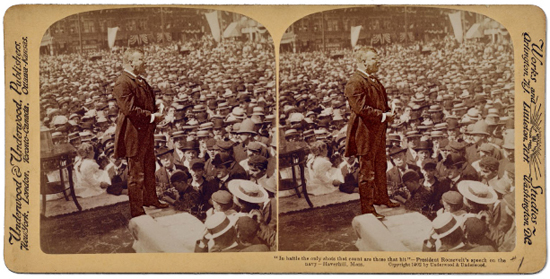

Stereograph photo of President Theodore Roosevelt promoting the expansion of the U.S. Navy in a 1902 speech at Haverhill, Massachusetts.

As a political movement, Progressivism developed in opposition to the apparent triumph of an oligarchic class and an unholy alliance between government and big business in an unapologetic orgy of crony capitalism. Not since the American Revolution was an American political movement so thoroughly joined and led by nonpoliticians. It was crusading journalists, novelists, educators, philosophers, social scientists, and all-around activists who inspired reform among the political class. In the end, however, it was a great politician and political leader, Theodore Roosevelt, who finally transformed the Gilded Age into the Progressive era, the heyday of which overlapped the Gilded Age and went beyond it, spanning roughly 1890 to 1920. In one way or another, Progressivism endured to both influence and infuse American civilization through two world wars, the Great Depression, and the liberal movements of the 1960s. Today, as we embark upon what many are already calling a Second Gilded Age, it remains to be seen whether a new Progressivism will reemerge into political relevance.