CHAPTER 4

IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT IN STORYTELLING

This chapter describes the importance of understanding data’s context and its role in helping data storytellers ask the right questions to build a story framework. You’ll learn about exploratory and explanatory analysis and strategies for successful storytelling, including narrative flow, considerations for spoken versus written narratives that support visuals, and structures that can support your stories for maximum impact. You will also explore helpful techniques in Tableau that guide you to crafting effective data narrative structure.

More than twenty years ago, Bill Gates coined the iconic phrase, “Content is king.” Gates was, of course, referring to the importance of content on demand in the early days (circa 1996) of the World Wide Web. His words were prophetic, however, and over the past two-plus decades this mantra has been applied to everything from Internet marketing to media to viral online content—suddenly everybody is a media company.

The never-ending quest for bigger, bolder, better online content has radically changed the way people acquire and share information and how we interact and communicate with others. However, although Gates might have been right then, his mantra is missing a critical ingredient: context.

If you type Gates’ “content is king” into your Google search bar, you might notice that a “but” is coming right behind it (see Figure 4.1). Content is king—but context is god.

Figure 4.1 Sorry, Bill. Content might be king, but context is god.

Context is especially important in the field of analytics. Just as communication begins before you ever start building your first data visualization, like any good story, a visual data story requires context—a setting, a plot, a need—before you can begin to communicate. Discovering this context is part of the storytelling process.

This chapter focuses on helping you understand the importance of context in data visualization and visual storytelling, how to ask the right questions in analysis that will help you begin to build out your story framework, and how to let context drive the story as you share it with your audience. The context of a data story is made up of four ingredients:

Context of data

Context of structure

Context of audience

Context of presentation

context caution

There’s more to context than just the data. Context can also be created by the storyteller or by the audience, based on knowledge, biases, and expectations. A successful storyteller needs to learn how to anticipate these issues. A good way to ensure your context works for you rather than against you is to ask and then answer a series of logically thought out and connected questions about the project, the data, and the audience. The answers to these questions provide a framework for your data story.

Context in Action

To quote football consulting company 21st Club, without context [in analytics] data is “meaningless, irrelevant, and even dangerous.”1 This might sound aggressive, but in practice, it’s an understatement. Without context we can’t answer any of the pivotal journalistic questions—who, what, where, when, why, and how—that provide pertinent details to help us get to the bottom of any big question. In fact, we can’t do much beyond just make good guesses. We have a whole lot of information, but it is incomplete and this can often cause us to miss out on major points that change the entire scope of our story. Beyond just bad storytelling, omitting critical context carries an even bigger risk. Ultimately, we use data stories to drive decision-making, and nothing paves the way for bad decisions like a lack of good information.

Rather than me just writing about the importance of context in data storytelling, let’s take a quick look at a fun example of a story where context makes all the difference. I use this practice in the dissection of data stories throughout this book.

Harry Potter: Hero or Menace?

In June 2017, Harry Potter and JK Rowling’s world of wizards celebrated its 20th anniversary.

By now, most of us are familiar with The Boy Who Lived. The Harry Potter series has been distributed in more than 200 territories, translated into 68 languages, and has sold more than 400 million copies worldwide.2 However, although we are familiar with Harry’s story in its novelized form, most of us haven’t taken such a concentrated look on the data inside the story.

note

If you’re a Potterhead, you’re in luck! A later chapter explores several stories hidden within the wizarding world’s data—working through the entire storytelling process from collecting and preparing data to presenting a complete data narrative.

Even if you don’t know all the nuances of Harry Potter, you likely know that the story follows the journey of young wizard Harry Potter as he fights against the evil dark wizard, Lord Voldemort, and his minions. With that minimal amount of context, we can assume that Harry is the good guy and Voldemort the bad.

To aid in visualizing the story of good versus evil in Harry Potter, we can use a fantastic public dataset of all the instances where characters in each of the books acted aggressively. When we visualize this data at the most superficial level (see Figure 4.2)—aggressive acts enacted by Harry and Voldemort in each of the books—these “lightning bolts” seem to show that over the course of the series Harry committed significantly more aggressive behaviors than did his nemesis, Lord Voldemort. In this version of the story, our good wizard suddenly looks a little more sociopathic than we might have expected. Yikes!

Figure 4.2 A modified bar chart of aggressive actions committed by Harry Potter and Lord Voldemort.

The good news to Potter fans is that if we look at the data like this we are overlooking critical context and showcasing a faulty story. Remember, the danger of a story told wrong is the prospect of making a bad decision based on inaccurate or otherwise incorrect information, and this logic applies to any story—even Harry’s. If we had presented this visual to, for example, Rowling’s publisher prior to the series being published, we might never have been introduced the wizarding world. Who would want to publish a children’s book that condones violence? Who would want their kids to read about a malevolent hero? Thus, telling an incorrect story could have resulted in a wrong decision (no Potter), rather than introducing a pop culture phenomenon that swept the world. Fortunately, we can remedy this by putting context back into the narrative.

Ensuring Relevant Context

To make sure we’re including context in a meaningful way, we need to revisit our initial assumptions of how we approached visualizing two key variables: the two characters and their aggressive acts.

In the previous attempt, we simply visualized a count of aggressive acts and neglected to consider the context in which the acts were committed (or the influence of the character on the narrative). Doing so puts an undue spotlight on Harry and presents an immediate contextual fallacy. This is Harry’s story, and as the protagonist all of his actions, aggressive or not, are heavily documented. In contrast, Voldemort, while a main character, has a lesser presence in the story. This logic helps us see critical context we neglected in a simple counting exercise. Rather than how many aggressive acts were committed by each character, we need to look at how often each character appears and how often they commit aggressive acts when mentioned.

Out of Context: How many times Harry and Voldemort acted aggressively.

In Context: How often Harry and Voldemort acted aggressively when mentioned.

Putting the data back into a relevant context, when we visualize again we see something very different (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 With a little bit of context added back into the data, we see a different story.

With more context added into the narrative, we see Voldemort’s true colors emerge. While Harry rarely acts aggressively when mentioned, Voldemort usually acts aggressively when his name is spoken. This completely changes the story takeaway that we presented before.

Of course, there is much more exploration we could do with this data to dig deeper into the role of aggression in Harry Potter and craft a richer visual narrative. We could bring more characters into view to analyze whether Voldemort is the ultimate bad guy in the series. We could look at aggression by book rather than by character, or look at who committed aggressive acts against whom and how and when character relationships affect how these aggressions are brought into play. We could even break down aggressive acts into violent and non-violent categories, or rank aggressive acts by level of severity. In any case, it’s unlikely the full context of this story could ever be told without knowledge of the series and its complicated plot, and both of these require support on the part of the presenter. This hints to the value of presentation in a visual data story. No matter how deep, data alone will never be able to tell a story as well as you.{55}{56}

note

Be especially careful with counts as these can influence your data and present a distorted version of the truth. To prevent this, “normalize” your data with a calculated field.

Exploratory versus Explanatory Analysis

Before moving on to looking at storytelling techniques and story structures, we need to draw a distinction between exploratory and explanatory analysis, and how these contribute to storytelling.

Exploration fuels discovery. It’s the process we take to explore data and uncover its story. In my visual analytics classes, I use an image of Indiana Jones to illustrate the concept of exploratory analysis because, like Dr. Jones, this is where we go looking for a discovery to share and hope to find something. We take time to search, digging in and out of data iteratively and with curiosity as we work to build a story, or perhaps many stories, or perhaps even none at all. Exploration is a process of “look and see,” and we must explore before we can explain.

Our job as analysts is to explore. Our job as data storytellers is to explain. Exploratory analysis might yield important story points, but they are not part of the storytelling process. As storytellers, we are focused on explanatory analysis and communicating our discoveries in the form of a story.

The distinction between explanatory and exploratory analysis has an important impact on context, particularly in how we present our results.

It is common for people to present exploratory graphics as part of their data story—after all, the discovery process can be an undertaking and we can be eager to show all of our hard work or display every detail we’ve found! However, the inevitable result is that this adds bulk to what should be a streamlined, focused story and muddies the message for the audience. In addition to telling a story, data storytellers must also act as their own editors. This requires trimming unnecessary content away so that the core of the data story remains unencumbered and intact. The following sections cover techniques to help achieve this.

recommended reading

For more on visual data discovery and working through exploratory analysis, read my book, The Visual Imperative. Additional resources are provided in Chapter 10 as well as on the website www.visualdatastorytelling.com.

EXPAND THE SHOW ME CARD!

You met the Show Me card in Chapter 3. The Show Me card (see Figure 4.4) can help guide you to building visualizations that best represent your data. As you choose measures and dimensions and bring them to the shelves, the Show Me card will display what chart types are available based on the fields you’ve selected. Likewise, if you’re unsure of which data to bring over to the shelves, you can use the Show Me card as a tool to select the right measures and dimensions.

Figure 4.4 The Tableau Show Me card, opened on symbol maps.

FILTERING OUT, ZEROING IN

Filters are a great way to help cut out the noise and let your data’s story shine (see Figure 4.5). You can strip out unnecessary information, or, likewise, focus on specific fields or elements critical to your data story. Like many things in Tableau, filtering can be done in several ways and several places. You explore some of these when working with real data sets later in this book.

Figure 4.5 A selection of filtering options in Tableau.

Structuring Stories

Like traditional stories, data stories have shape—and not just bars and bubbles!—or “structure.” Story structure plays an important role in developing a story’s context, and can be broken down into two parts:

![]() Part One: Story Plot

Part One: Story Plot

![]() Part Two: Story Genre

Part Two: Story Genre

Story Plot

The events of a story (or the main part of a story) are its plot (this is also called its storyline). These events generally relate to each other in a pattern or a sequence, and the storyteller (or author) is responsible for arranging these actions in a meaningful way to shape the story.

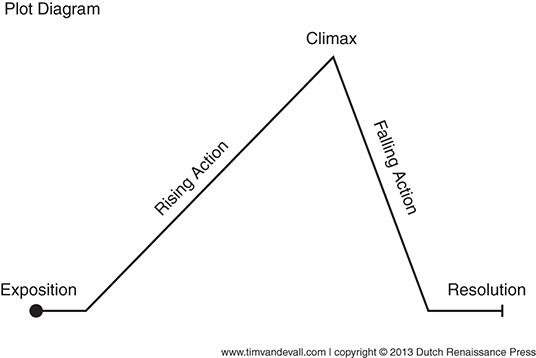

Like other forms of storytelling, the plot of a data story can be organized into a linear sequence (see Figure 4.6) or not—not all data stories are told in order; however, they all have one thing in common: They must be true. Data stories are not the place to practice fiction.

Figure 4.6 The basic plot diagram.

note

The plot diagram is an organizational tool to help map events in a story. Its familiar triangle shape (representing the beginning, middle, and end of a story) was described by Aristotle and later modified by Gustav Freytag who added rising and falling action. Though designed for traditional stories, data stories can be built using this same framework.

For the purposes of data storytelling, there are eight basic “plots” to help shape your visual data story (see Figure 4.7). Can you identify the plot used in the Harry Potter example (Hint: We were telling a story of aggressive acts over the series)?

Change over time—See a visual history as told through a simple metric or trend

Drill down—Start big, and get more and more granular to find meaning

Zoom out—Reverse the particular, from the individual to a larger group

Contrast—The “this” or “that”

Spread—Help people see the light and the dark, or reach of data (disbursement)

Intersections—Things that cross over, or progress (“less than” to “more than”)

Factors—Things that work together to build up to a higher-level effect

Outliers—Powerful way to show something outside the realm of normal

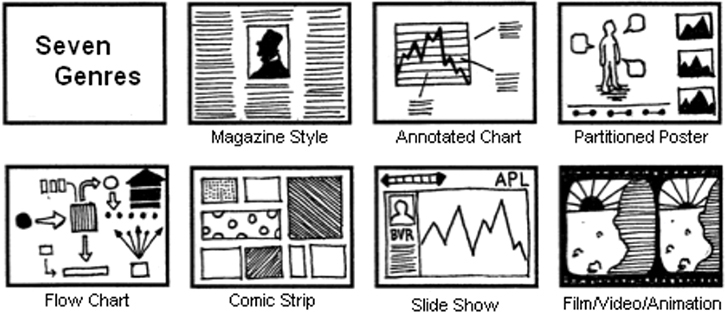

Story Genre

The other half of story structure is its genre. Like the diversity in plot, there is more than one genre to choose from. In fact, there are seven genres of narrative visualization. Developed by Segel and Heel,3 they vary primarily in the number of frames and the ordering of visual elements and include the magazine style, the annotated chart, the partitioned poster, the flow chart, the comic strip, the slide short, and finally, the conglomerate film/video/animation (see Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7 Genres of Narrative Visualization by Segel and Heer.

In Tableau, you can use dashboards and story points to each of these genres, and Chapter 7, “Preparing Data for Storytelling,” explores how to build them. For now, keep in mind that data stories are most effective when they have constrained interaction at various checkpoints and allow the user to explore and engage with the story without veering too far away from the intended narrative. Stories unfold, and each visualization should highlight one story point at a time (whether within the same visualizations or within multiple) as storytellers layer points to build a complete data narrative.

Audience Analysis for Storytelling

A successful data storyteller has to be a master of their craft, able to meld the worlds of data visualization and storytelling together into a cohesive whole. However, the story is only half of the equation. A story is a piece of communication, and like every communication, stories are part of a two-way dialogue between the sender (you) and the receiver (your audience). If the story gets interrupted or otherwise lost in translation, you’ve lost the ability to communicate and will likely fail. Therefore, storytellers need to be clear on exactly who is on the receiving end of their story, and have confidence that they have the information they need to build the right story for their audience.

Many visualization instructors might phrase this step of the story-building process in terms of asking the “right” questions, though a lot of ambiguity exists that surrounds just what these questions are. Just like in any type of analysis, there is no silver bullet approach for gathering audience expectations or stakeholder requirements. Questions, like stories, have entropy: They change based on everything from the nature of the relationship of the storyteller to the audience, to the action the audience would like to take, to the mechanism in which the story is presented. So, a good storyteller knows that the trick isn’t asking the right questions, but in asking many. It’s okay to be really, really curious, even insatiable in your desire to really understand your audience and every situation you encounter. It’s iterative, and a process of compromise between what you want to say and what the audience needs to hear. Ultimately you need to be able to learn as much as you can about your audience and what they need to know, and then build a story that anticipates and delivers on audience needs.

Curiosity is a learned skill. It takes time to develop a palate for asking the right research questions and plucking out the relevant details from the noise. Remember, visual data storytelling is fact, not fiction, and as such involves a requisite degree of research as you move through visual analysis. As you practice molding yourself into a thoughtful questioner, however, you can use the some of the same journalistic questions that help to parse out the correct context for a story—particularly who, what, why, and how—to make sure you build a presentation that’s going to resonate with your audience and give them the information they need to take action. Let’s look more closely at these.

Who

Be specific about your audience. Avoid generalizations and assumptions. Taking a broad view of your audiences has the consequence of overlooking nuances and specific needs that help you zero in on what your audience needs and wants to hear, as well as how you might be best able to communicate with them to capture their interest. Also, narrowing in on your audience will show you who the decision makers and key influencers are, who needs and wants to hear your story, and those whose buy-in you really need to earn. Remember, engaging with your audience is a critical part of successful storytelling.

It’s also important to consider the affect of your relationship with the audience. Do they know you? Do they trust you? Do they believe that you are a credible and reliable source of information and insight? The answers to these questions are important because they might influence how you structure your presentation as well as any pre- or post-presentation communication. Your audience must believe in you as an analyst and a storyteller before they will listen to your story and be open to taking any actions you might suggest.

What

Analytics begins with understanding data—what you have, what you need, its capabilities and its limitations. Additionally, you should have a realistic view of its quality and validity, and thus its ability to answer business questions or explore a hypothesis—as well as if you should seek additional or external data to complete your dataset for analysis. Understanding your data also requires you to have a good grasp on how to visually represent this data compellingly and accurately, so that you are practicing “no harm” data visualization as you design your narrative.

In addition to knowing the ins and outs of your data, be sure you’ve asked enough questions to work out what your audience is asking of you, or what story they are asking you to tell with the information you have at your disposal. Be sure to have a solid alignment of ideas between what questions can be answered with your data and what insight or information your audience needs or wants; otherwise, your data story will fall flat, unable to satisfy audience expectations.

Why

Every good story should prompt an action, whether you are building a story intended to help your audience to make a decision; to cause them to change their opinion; or otherwise to convince, persuade, or educate. Ultimately, you should be crystal clear on what your goal is with the story, and why your audience should care about what you are saying. This helps to both ensure your story is meaningful and necessary, and to give you a clear target of how to build logical arguments toward a salient end goal.

To help crystalize the answers to the “why” part of the equation, be able to articulate an answer to clearly and concisely answer the following questions:

![]() Who is your audience? (They might not be as homogenous as you think.)

Who is your audience? (They might not be as homogenous as you think.)

![]() What do they want?

What do they want?

![]() What do they need?

What do they need?

![]() How might they be feeling?

How might they be feeling?

![]() What action do they need to take?

What action do they need to take?

![]() What type of communication do they prefer?

What type of communication do they prefer?

![]() How well do they know the data?

How well do they know the data?

![]() What beliefs or bias might they have that you need to reinforce or challenge?

What beliefs or bias might they have that you need to reinforce or challenge?

![]() What, specifically, are you sharing with your audience?

What, specifically, are you sharing with your audience?

![]() What, specifically, do you want them to do with this information?

What, specifically, do you want them to do with this information?

If you cannot readily answer most (if not all) of these questions, you might need to revisit your purpose.

How

Finally, the communication medium and channel you use to present your story matter. In fact, it has a number of implications for how you deliver your story, as well as how much influence you have as a storyteller and how interactive your audience can be with you as well as with the story itself. Although there are many facets to explore in this step, one of the most constructive is to understand the differences between data stories delivered as narrated, live versions or those that are non-narrated or otherwise “static” presentations.

Narrated

Narrated storytelling presentations are those that are delivered live—whether in person or virtually—where the storyteller has the ability to narrate the presentation and guide the experience. In this mode, the storyteller has full control of the narrative and is able to direct the audience’s attention to points of interest and facilitate transitions between story points, explaining any potential areas of ambiguity, or likewise, emphasize or soften points as needed.

In addition to the ability to direct the audience, live presenters also have an obligation to be sensitive to the audience and respond to their needs. As a presenter, you have a front row seat to your audience, and remember: You are not a TV screen—you can react and respond to visual cues to determine whether you need to speed up or slow down or go into more or less detail as you move through your presentation. One tip I give to students learning to present is to always have more pieces of the story than you are planning to share stored in your back pocket. That way, if you need to dive into detail or add an embellishing point to your story, you can introduce it without adding junk into your presentation and interfering with the flow of your data story.

Non-Narrated

On the other hand, non-narrated storytelling presentations are those that are delivered without the benefit of a storyteller to guide the experience, such as reports or emails or even dashboards. In any of these instances, the storyteller relinquishes control of the audience’s experience and relies on the puts it in the hands of the tool used to distribute the information.

To ensure the integrity of the visuals and the story, a highly curated and detailed view of the information is necessary. In the case of Tableau, dashboards or story points, this translates into not just well-crafted visualizations, but cohesive, logical storylines and appropriate filters, highlights, and other venues to let the audience explore visuals without degrading the story or the underlying data’s integrity. Pay attention to device form factor here, too, as you will need to be aware of how your story presents across multiple devices (laptop screens, tablets, smartphones, and so on).

TIPS FOR SUCCESS IN PRESENTATIONS

Telling data stories through a live presentation is as much an art as building the story itself. This means that storytellers must, in addition to their skills in data analysis and visualization, be skilled presenters, equipped with the capability to guide the audience through the story and facilitate a shared experience.

It’s a known fact that public speaking in any form isn’t a concept that excites many people. In fact, in a statistic made humorous by comedian Jerry Seinfeld, according to most studies, people’s number one fear is of public speaking. Number two is death. Thus, Seinfeld’s joke is that the average person at a funeral would rather be the one in the casket than the one conducting the eulogy.

The secret to overcoming presentation anxiety and polishing up your skills as a speaker is this: practice. Practice gives you opportunities to learn your own strengths as well as identify areas to improve, helps you discover and fine-tune your speaking style, and—perhaps most important—it is the one and only venue to building confidence earned from experience.

Here are a few tips to help you become more comfortable to go “on stage”:

![]() There’s wisdom in the mantra “practice makes perfect.” Rehearse, revise, rehearse.

There’s wisdom in the mantra “practice makes perfect.” Rehearse, revise, rehearse.

![]() Write out speaking points, not speaking paragraphs. Document three to four important points you want to make for each slide to be your compass.

Write out speaking points, not speaking paragraphs. Document three to four important points you want to make for each slide to be your compass.

![]() Design presentations to support your story, not presentations to tell your story. Your audience should be listening to you, not reading slides. Just like in a chart or graph, maximize the data-to-ink ratio and keep visuals clean and minimal.

Design presentations to support your story, not presentations to tell your story. Your audience should be listening to you, not reading slides. Just like in a chart or graph, maximize the data-to-ink ratio and keep visuals clean and minimal.

Summary

This chapter looked closely at the importance of understanding data’s context and its role in helping data storytellers ask the right questions to build a story framework. You learned about exploratory and explanatory analysis and strategies for successful storytelling, including narrative flow, considerations for spoken versus written narratives that support visuals, and structures that can support stories for maximum impact.

The next chapter looks at the importance of choosing the right visual—or combinations of visuals—to support your data story, as well as how to build basic visualizations in Tableau.

_____________

1. http://www.21stclub.com/2013/08/11/contextual-intelligence-a-definition/

2. http://harrypotter.scholastic.com/jk_rowling/

3. Segel, E. and Heer, J. (2010). Narrative visualization: Telling stories with data. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 16(6), 1139–1148. https://doi.org/10.1109/TVCG.2010.179