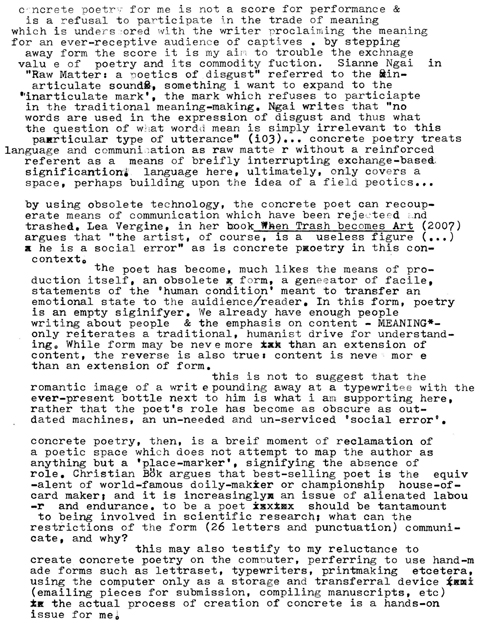

Figure 5.1

Original of Derek Beaulieu’s “statement,” a poetic manifesto

Translating Experimental Canadian Poetry for a Brazilian Audience

The great writer Isaac Bashevis Singer once wrote,

The translator must be a great editor, a psychologist, a judge of human taste; if not, his translation will be a nightmare. But why should a man with such rare qualities become a translator? Why shouldn’t he be a writer himself, or be engaged in a business where diligent work and high intelligence are well paid? A good translator must be both a sage and a fool. And where do you get such strange combinations?1

Where indeed do we get such “strange combinations,” and how and why does anyone become engaged in the unlikely project of taking contemporary experimental poetry from one hemisphere to another and from a so-called hegemonic language into a non-hegemonic one?2 All these questions and others have come to my mind as I reflect now on a project that began some years ago, and which is slowly but steadily coming to a conclusion: the idea of creating the first-ever sampling of contemporary experimental poetry from English-speaking Canada for a Brazilian audience.3 In this essay, I would like to reflect on the many lessons learned in this journey from the Rockies to the Amazon, lessons not only about translation but also about cultural contact. I begin first with issues emerging from the creation of anthologies in general, and of anthologies of translation specifically, and how those issues played out in our case. I then move on to briefly consider the literary relations between these two countries, particularly aspects of the reception of Canadian literature in Brazil, another matter that influenced both the creation and configuration of this anthology. After a brief consideration of the nature of experimental texts and its relevance for translation, I discuss some of the textual choices Christine Stewart and I, as coeditors, made and how some of the translation problems were handled by Luis Dolhnikoff and me as co-translators. Throughout all of these sections, I will touch upon questions of translatability, a concept “inevitably coupled with untranslatability.”4 By way of conclusion, I offer a summary of the issues we faced, which could be seen as suggestions for similar projects, and a reflection on how this project, as cultural intervention, also brought to light surprising geopolitical parallels and aesthetic affinities between these two countries.

As a growing body of research on anthology compilation points out, much is at stake when producing an anthology. Jeffrey R. Di Leo, editor of the most comprehensive anthology of essays on anthologies, argues that “[t]oday anthologies are discussed […] in terms of the canonical formation that they propose and the possible political and cultural direction in which they implicate their subject matter […] Anthologies have consequences and are grounded in commitments.”5 When Christine Stewart, a poet from Vancouver’s Kootenay School of Writing, and I, a researcher and translator specializing in Brazilian poetry, began work on this anthology, we were (perhaps blissfully) unaware of the canonical formations and other cultural and political consequences our project might have. A number of commitments, however, did serve as grounding. The first was a common interest in experimental writing; and the second, a desire to bring together, via translation, two seemingly far-flung contexts, Canada and Brazil. These commitments led us to the task of compiling a selection of Canadian English-language experimental writing, within certain bounds in terms of generations and that would speak to a sophisticated Brazilian readership. Our intention coincided with what some critics identify as the general goals of translated anthologies as a paradigmatic medium of literary transfer: “to promote an interest in target in the source literature” and to serve as “instigation to target-side poets.”6

Active in Canada’s contemporary poetry scene, and very knowledgeable about it, Christine began gathering a selection of texts by experimental writers who agreed to have their work included in the anthology. As any anthology editor knows, “assembling a fresh and viable anthology involves hard decisions,”7 and a number of lessons emerged at this early stage, even before tackling translation issues. For instance, one author we approached decided not to be part of our project because she did not want her work labeled as “Canadian.” Other writers, in turn, complained about not being included. Finally, we were also taken to task, at a public presentation, for our role as “gatekeepers” of Canadian poetry abroad. All of these reactions betray the above-mentioned perception of the canon-formation power that anthologies wield, whether intentionally or unintentionally. Perhaps making our aims and criteria for inclusion more explicit at the outset might have avoided some of these misunderstandings.

Anthologies, indeed, have various aims and orientations. Margarida Vale de Gato notes that “[s]urvey anthologies can be national or oriented towards ethnicity, genre, particular movements or literary schools and periods, and [often] they overlap with the focus anthology that might adopt, for example, the angles of genre and gender.”8 So, while our anthology attempted a sampling of territory and genre responding to (admittedly subjective) notions of quality, it was never meant to exhaust any of these categories. Moreover, when it comes specifically to national identification, “the notion of Canada presented in anthologies,” Robert Lecker reminds us, “varies widely and is constantly changing in response to shifting concepts of the country.”9 We adopted a very open view of Canada—basically any author that self-identified as Canadian, whether or not he or she was actually based in Canada— and, given our qualifications, we limited ourselves to its English-language context. Our intention was to “present,” rather than “represent,” because, ultimately, as Lecker observes, “the anthological construction of the nation today is in many ways about the deconstruction of national identity,” a point we will return to below. In essence, our objective was in line with Paul Auster’s view that “[o]ne must resist the notion of treating an anthology as the last word on its subject…. It is no more than a first word, opening on to a new space.”10

Nothing could be truer in our case. As, literally, “a first word,” our project aimed at creating awareness of this experimental scene, seemingly unknown to otherwise savvy Brazilians.11 Other valuable lessons were learned here. The fact that “[t]ranslation anthologies are very common in many countries,” playing a role in cultural transmission (both nationally and internationally) as configurated corpora,12 led us to ponder what this lacuna might mean. “Do national literature anthologies—or the absence of them—say something about how nations are understood? Or do such anthologies encourage nations to be mis understood?” one scholar wonders, concluding that “[t]hat could be their most valuable function.”13 In our case, what could the dearth of experimental (and other) Canadian writing available to Brazilians14 signal about how Canada is (mis)understood in a context otherwise open to foreign and innovative trends?15 Could it be chalked up to (a relative lack of) literary awareness between these two countries,16 or to yet something else?

P. K. Page, a major Canadian poet, is a notable exception in this history of limited cultural contact. She lived in Brazil in the 1950s as the wife of a Canadian diplomat but didn’t speak enough Portuguese to fully participate in Rio’s literary circles at the time. Page’s memoir, Brazilian Journal, records her observations of Brazil’s people, culture, and language. Miguel Nenevé, the Portuguese translator, calls it an “inviting and challenging task for a Brazilian reader, as the text is about the author’s experience of Brazil and an attempt to translate the country for her Canadian audience.”17 Closer to our time, major writers such as Margaret Atwood and Alice Munro have been widely translated and read in Brazil, especially after Munro was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2013.

Other efforts at exchange have been more institutional. The Canadian government maintains a (somewhat uneven) site of Canadian writers who have been translated into Portuguese.18 An academic organization, the Brazilian Association of Canadian Studies (ABECAN), was founded in 1991 in Curitiba with the mission promoting mutual exchanges in “the study of culture, science and technology of Canada and its interrelation with Brazil.”19 Based at a number of major Brazilian universities, ABECAN publishes an online academic journal, Interfaces Brasil/Canadá, which includes literary scholarship. Another recent connection attempt was the 2014 edition of the Porto Alegre Book Fair, where Canada was the guest of honour. On the South-North exchange, the work of the Brazilian émigré poet and academic Ricardo Sternberg should be mentioned. Trained in the United States, he became Professor of Brazilian literature at the University of Toronto, teaching and writing about Brazilian poetry and literature, and translating major poets such as Jorge de Lima, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, and João Cabral de Melo Neto. Another item of note: revue ellipse mag (1969–2012), a unique long-running periodical that published poetry and other literary works in both official languages of Canada, devoted a full issue in 2010 to Brazilian writing in translation.20 More recently, in 2014, the Brazilian poet Adélia Prado was awarded, along with her American translator, Ellen Doré, Canada’s most prestigious poetry distinction, the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry’s Lifetime Recognition Award. Still, when it comes to the experimental writing scenes in these two countries, there is little to no contact between them.21

To the inherent issues involved in creating anthologies discussed above, we can thus add the lack of contact. The difficulties escalate if we then consider the nature of the anthologized texts. Something which clearly hinders the dissemination of experimental writing in any language is the very nature of that writing. This was acknowledged by the editors of Pulllllllllll: Poesia contemporânea do Canadá (2011), an anthology published in Lisbon which gathered thirteen English-language Canadian poets22 working at the intersection of experimental movements such as sound poetry, concrete poetry, OuLiPo, and L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E. Experimental texts are frustrating to readers and even more so to translators, the editors of Pulllllllllll note, because of the “resistance to translation” that emerges from their intensive work on language and which produces a crucial experience of “não-sentido” (“non-meaning”) in the reader.23 In other words, these texts are difficult to read in the original, as our examples below will show, and many—given their tight connection between meaning and form—are also borderline untranslatable.

Translation issues don’t end with form. The target context and audience likewise need to be carefully considered. “[O]ne must be attentive,” Victor Mair writes, “not only to the quality and representativeness of the literary pieces that will be included, but also to the tastes of one’s audience as well as their ability to comprehend and appreciate what one is offering up to them. Otherwise there will be a basic incompatibility.”24 This becomes a question of translatability in a way that may not be entirely obvious. As Pym and Turk argue, translatability, as a dynamic category, depends “on the target language, and especially on the translation culture existing within it; it would lean on previous translations of the same text or of other texts translated from the same language, literature or genre. It can also be influenced by the attention of critics, the interest and previous knowledge of the receiver.”25 In other words, when preparing an anthology such as this one, the editor/translator acquires roles and responsibilities that go beyond the traditional concern for rendering accurately and creatively the contents of even the most complicated original. He or she must be aware of how experimental texts, challenging to begin with for a “domestic” audience, may fare as they cross over to a remote language, context, and audience, especially if no previous history of translation or reception of such works can be depended upon.

This had consequences for the way Christine Stewart and I approached the editorial process. Initially, I entirely relied on her judgment and her thorough familiarity with the work of most of the writers we included. Soon, however, the question became not so much who, but what should be included, and why. This would have been a very different question if we were only considering the work in its original language. At that point my own role as anthologist/editor began to change into that of a diplomat, a cultural broker, and a judge dictating sentence on which texts would work better than others in translation and therefore deserved inclusion. And I say my role, because just as I deferred to Christine about the initial cut, given her extensive knowledge of the source language and context, as translator, I had the knowledge of the target language and audience of our project.

Here the considerations were many. First, in our role as diplomats or cultural brokers, I felt we had the responsibility to create a certain “narrative” of contemporary experimental poetry from Canada that would “resonate” with the poetry readership in Brazil. Accordingly, while this did not mean defining the “Canadianness” of this writing, it did mean “packaging” Canadian experimental poetry for a Brazilian audience who, though poetically sophisticated, would nonetheless be encountering these poets for the first time. In the attempt to find points of contact between this unlikely pairing, there were interesting revelations. For one thing, we were drawn to poems and poets that reflected the diversity of Canadian experience and identity (Native, immigrant, women, etc.) and its oral traditions, something we felt was important to portray. This led us to poets such as Annharte and Oana Avasilichioaei, whose work is inflected by their Native and immigrant backgrounds, respectively. For instance, the following passage from Annharte’s poem “Mama Sasquatch” (a reference to a Pacific Northwest folk character), reveals the presence of First Nations voices and the texture of orality in the midst of a gritty street scene in Vancouver:

| ndn bag lady panhandling for a drink | indígena sem teto pedindo esmola para beber |

| interrogation reveals you a teacher | interrogação revela que você é professora |

| first friend during depression episode | primeira amiga durante episódio de depressão |

| I stare back at ugly sidewalk café customers not even wanting a latte | observo o feio café com mesas na calçada clientes indiferentes não bebem café-au-lait |

| Commercial Drive repels me lonely need a job so I wander back forth | Commercial Drive me repele solitária precisando de emprego divago pelas ruas |

| you became a true pavement ndn type | você virou um tipo de indígena urbana genuína |

| teacher education did not prepare us | a escola normal não nos preparou para |

| for street survival and your ass print | a supervivência nas ruas e a impressão de |

| on the bench front of the bank is gone | tua bunda no banco frente ao banco sumiu |

Likewise, Avasilichioaei’s poem, “The Tyrant and the Wolfbat: A Tailing or A Telling,” discussed below, evokes the storytelling traditions of the poet’s Romanian ancestors. In making these choices, it would be disingenuous not to admit, as Lecker notes, that “the development of the anthological text may be viewed as a harmonized and conflicted narrative that expresses the editor’s impossible desire for coherence.”26 In our case too, it also meant finding points of contact with an equally conflicted narrative of Brazil. The effort revealed convergence and variance. Brazil also possesses a rich indigenous folklore and vast immigrant populations, something that would strike a familiar chord with readers there, who may be familiar with indigenous traditions and boast diverse ancestries. Still, in contrast to Canada, these voices are seldom heard in Brazilian experimental poetry, where there is only minimal participation from minorities or the incorporation of orality.27 On a different note, and in another parallel with Brazil, where historically there was racial prejudice against Asian immigrants, we chose works that tackled, often through mild sarcasm and black humour, racial and cultural stereotypes still prevalent within Canada’s multicultural society. One eloquent example is this passage from Fred Wah’s “The Marlin Grill”:

It’s called the Marlin for two reasons. First, I had this stuffed Marlin of my father’s. He got it when he worked in Mexico after leaving China around 1902, before he came to Canada. But I also wanted to call it the Marlin to honour my father’s brother, uncle Mah Lin, who was murdered in Calgary in 1900…. We thought of calling it Chinaman’s Peak after that mountain in Canmore but people here are still a little prejudiced so we thought it wouldn’t be such good luck for business.

A churrascaria se chamava o Marlin por dois motivos. Primeiro porque lá tinha um marlim empalhado pertencente ao meu pai. Ele o ganhou quando trabalhou no México, depois de sair da China ao redor de 1902, antes de vir pro Canadá. Mas eu também queria lhe dar o nome de Marlin para honrar a memória de meu tio Mah Lin, irmão do meu pai, que foi morto em Calgary em 1900…. Pensamos também chamá-lo de Chinaman’s Peak, em homenagem a essa montanha em Canmore, mas as pessoas aqui ainda tem um pouco de preconceito, pelo qual achamos que não seria bom para os negócios.

Another evident preference was poetry that focused primarily on language and the relations between sound, meaning, and image, along the lines of concrete poetry. The choice here was clearly based on precedents for this kind of writing in the target context. Brazil was, after all, one of the hotspots of the literary avant-garde from the 50s on, and its legacy is still felt today, as much in its staunch opponents as in its faithful supporters. In North America, concrete poetry did not reach a point of exhaustion in precisely the same way, so it is not surprising that nowadays Canadians such as Christian Bök practice the kind of Oulipian poetry that earned him the prestigious Griffin Poetry Prize in 2002 for his book Eunoia. The title of this work, a word from the Greek, meaning “beautiful thinking,” is the shortest word in the English language containing all five vowels. The book itself is what Bök calls an instance of univocalics: each chapter uses words that contain only one vowel, something which in his view proves that “each vowel has its own personality, and demonstrates the flexibility of the English language.”28 Whether one buys this argument or not, the effect is mesmerizing, as the following passage from “Chapter E—For René Crevel,” shows:

Westerners revere the Greek legends. Versemen retell the represented events, the resplendent scenes, where, hellbent, the Greek freemen seek revenge whenever Helen, the new-wed empress, weeps. Restless, she deserts her fleece bed where, detested, her wedded regent sleeps. When she remembers Greece, her seceded demesne, she feels wretched, left here, bereft, her needs never met. She needs rest; nevertheless, her demented fevers render her sleepless (her sleeplessness enfeebles her). She needs help; nevertheless her stressed nerves render her cheerless (her cheerlessness enfetters her).29

Clearly, Bök’s poetic tour-de-force is a translator’s nightmare. Precedents for the challenge of translating this type of forbidding poetry include the many French translations of Lewis Carroll’s 1876 nonsense poem The Hunting of the Snark, beginning with the Surrealist Louis Aragon (1929),30 to Gilbert Adair’s translation of Georges Perec’s Oulipian novel, the e-deprived La Disparition ( A Void ).31 One possible choice for the translator, in the case of Bök’s Eunoia, would be to reproduce the writing constraint (using only words containing a certain vowel), while attempting only in a secondary way to reproduce the semantics and the narrative. Needless to say, this might generate an entirely different effect in Portuguese. Vowels might very well have vastly different “personalities” in different languages, and the specific narratives Bök creates in English would be inevitably lost. This determined our choice not to attempt a translation from this landmark work—the losses would have been far greater than the gains. Instead, we chose poems from an earlier book Crystallography, which also played on the materiality of language, particularly alliteration and graphic layout, but not to the same extent as Eunoia. Still, in the process of translation, this deceptively “simpler” text revealed a series of subtle language games that included hidden palindromes and anagrams (of, for instance, the name of the French mathematician Mandelbrot), which needed to be rendered creatively in Portuguese.32 A fragment from “Fractal Geometry” illustrates this:

| Fractals are haphazard maps that entrap entropy in tropes. Fractals tell their raconteurs to counteract at every point the contours of what thought recounts (a line, a plot): recant the chronicle that cannot coil into itself—let the story stray off course, its countless details, pointless detours, all en route toward a tour de force, where the here & now of nowhere is. Don’t ramble—lest you dream about a random belt of words brought to you by Mandelbrot. | Os fractais são mapas casuais que atrapam a entropia em tropos. Fractais dizem a seus contadores para contradizer em cada ponto os contornos do que o pensar reconta (a linha, a trama): desconte a crônica que não se encaracola em si—deixe a história desandar fora de curso, detalhes sem conta, desvios inúteis, todos en route rumo a um tour de force, em que sem lugar ou hora o aqui é agora. Mas não se embote: não vá sonhar sobre elos randômicos de palavras a todos lembrados por Mandelbrot.33 |

In this passage, the play on words such as count and counting did not present as much of a difficulty as did the palindromes “here & now” / “nowhere” or “don’t ramble”/ “random belt” / “Mandelbrot.” These verbal games, however, are not unlike much of the wordplay that animated the work of concrete poets in Brazil from the 1950s on and even contemporary poets such as Arnaldo Antunes continue to employ, so we felt the poems would travel well.

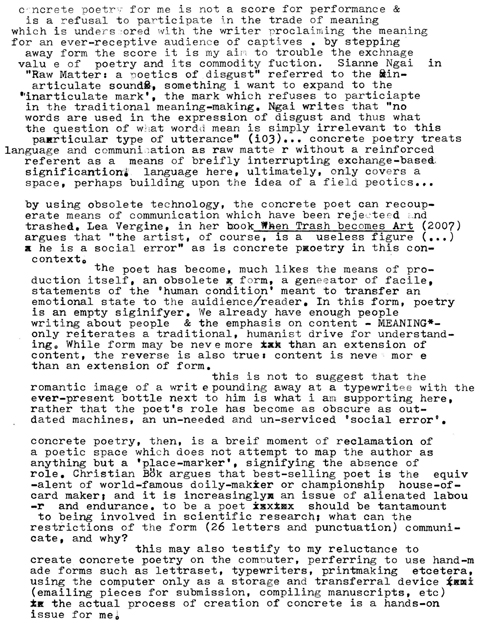

Another nod to the importance of concrete poetry in Brazil, was our inclusion of Derek Beaulieu’s “statement,” a manifesto typed on an old typewriter where he writes that, “by using obsolete technology, the poet can recuperate means of communication which have been rejected and trashed.” This piece provided a fascinating counterpoint to the “Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry,” launched in Brazil in the 1950s by Haroldo and Augusto de Campos and Décio Pignatari, where the poets advanced the idea of using the then-novel mass media to transmit their message more effectively.34 The impulse in Beaulieu’s poem is the opposite (he embraces obsolete technology), but the focus on the material is identical. In order to preserve the focus on the materiality, Beaulieu participated in the “translation” of this piece by offering to retype the translated text using the same method he used for the original, namely, typing the piece without looking at the keys and with the roller of the typewriter unengaged, which is why the piece slants down the page. He thus created a new piece exclusive to our edition, which, above and beyond the semantic content, allowed for even the physical form of the original to echo in the translation (see Figures 5.1 &5.2 below):

Figure 5.1

Original of Derek Beaulieu’s “statement,” a poetic manifesto

Figure 5.2

Translation of Derek Beaulieu’s “statement,” a poetic manifesto

This had implications in terms of authorship and also destabilized the concept of translation, since the author himself participated in the “form” translation of his piece, subsequently creating a new “original” out of the Portuguese translation.

Besides the materiality of language, a couple of other narrative threads emerged, which I will discuss only briefly. The first narrative thread led us to poetry linked to environmental concerns. One example in this vein is the series by a. rawlings, “signs of engenderment,” “signs of endangerment,” “signs of extinction,” where the gradual disappearance of certain letters of the alphabet from the text mirrors the extinction of living beings on earth. Likewise, we chose Rita Wong’s environmentally charged texts “recognition/identification test” and “green trust,” where words referring to natural objects are juxtaposed to “artificial” names of companies or brands, warning us about contemporary society’s estranged relationship to nature. The second important narrative involved critiques of capitalism, such as Aaron Vidaver’s “The Market Prefers,” a text made up of fragments randomly culled from online sources. When queried about the meaning of certain phrases during the translation process, Vidaver revealed that certain questions were impossible to answer because his original had been generated through an Internet search:

For me a key thing is that “the market” is the subject as active force with desires, preferences as well as subject in the grammatical sense. Also important for the composition was to keep it documentary, that is, a display of actual language use rather than as “raw material” from which to write a poem. The fragments appear as fragments because in the listing of search results often the sentences would be cut off.35

In this sense, there was a fair degree of freedom in terms of the translation choices, as there was no deliberately “intended” meaning, and our goal in the Portuguese translation was to produce the same effect of estrangement that the original would have on the English-language reader.

Then came the difficult cases, literally, the ones where, as judges, we had to sentence certain canonical works to exclusion, selecting instead lesser-known works. The main reason in these cases was that, for textual and contextual reasons, we sensed insurmountable difficulties in how well they would carry over into the target language and culture. One such example was the landmark collection Debbie, An Epic by the renowned poet Lisa Robertson, which plays with, and indeed debunks, the epic genre by turning its rhetorical devices against itself and deploying a Barbie-like mock heroine. After reading selections of this important and dense work, I strongly felt that it would be tragically lost in transit. I just could not see Brazilian readers getting it. Among the problems were both the poem’s tenor, references, and vocabulary, as well as the attack on a particular kind of rhetoric Robertson carries out. Equally untranslatable would be the associations around the personality of the female pseudo heroine “Debbie,” a name common in North America, but whose contextual resonances would be entirely lost in Brazilian Portuguese. I chose instead passages from another work that also references the epic, but in a different way, and then, interestingly, a poem where Robertson alludes to the Brazilian modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer, a household name in Brazil. With many of Dorothy TrujilloLusk’s pieces there were similar translation challenges. Some of her poems work intensively with the roots of Anglo-Saxon words, creating untranslatable textures and sounds I could not even see the possibility of replicating by resorting to Galician or medieval Portuguese.

Still, despite the choices and exclusions, our selection proved a generous one, and the hope is that the translations will do justice to the originals. The task and process of translating in collaboration with a talented poet/translator from Brazil, Luis Dolhnikoff, also personally afforded me many findings and surprises. I’d like to mention a couple of examples which explain, to recall my initial quote again, why translators do what they do. The following stanza from Oana Avasilichioaei’s “The Tyrant and the Wolfbat” evokes the orality of itinerant vendors:

—Taaaales for sale! Get your tale for a pennnny!

We got yarns, we got legends, we got them alllll!

—Cooontos com desconto! Compre seu conto por “um connnto”!

Temos lendas, legendas, lorotas, tuuuudo!

In our translation, certain felicitous coincidences made the translation, if not gain something, at least become a deserving parallel of the original. With the Portuguese play on “contos,” stories, “desconto,” discount, and “conto,” an amount of money, we obtained an interesting rhyme to reflect the English “tale/sale.” The English “yarn” and “legend” is contained in the single word “lorota,” which means both a piece of yarn and a piece of gossip. (Interestingly, this poem was originally titled “Gossip in the Valley.”) To intensify “lendas”—legends—we added the word “legendas” a so-called false friend in Portuguese meaning not “legends” but “subtitles.” This verbal instability and wordplay adds a bit of the humour displayed throughout the entire poem. Another passage describes aspects as well as states (physical and emotional) of the made-up mythical character “wolfbat”:

(hung-up, wolfbat is brood)

Though the emotional state (brooding) is inevitably present indirectly, almost as a shadow, as the author explained in an email communication, “it is more just the animal sense of brood (as in a family of young animals, a brood of animals). So that the wolfbat is multiple and is creature. Again, this is related to veering away from the personification… more towards the creaturely.”36 Our solution was:

(cabisbaixo, o lobimorcego é ninhada)

Here the challenge was obtaining the physical and emotional meanings of “hung-up” and the affective connotations of “brooding” besides the reproductive meaning of “brood.” The Portuguese word “cabisbaixo,” etymologicallywith one’s head is hanging low but meaning “crestfallen, ashamed,” reflects both bodily and psychological states, while “ninhada” conveys the exact reproductive meaning of “brood.” It is in these small moments of discovery and wonder when one realizes why the translator takes on all those roles and many more, as Singer notes, why the translator, in his words, must be “both a sage and a fool.”

Reflecting on the process of translation, perhaps the most important lesson from this experience is that collaboration in these types of translations, from dissimilar contexts that historically have had little contact, and of challenging texts such as these, is not only desirable but almost necessary. It has become clear to me that this can rarely be the work of a single person. Bringing two very different poetry contexts together through the act of translation involves a deep knowledge of, and expertise in, both languages and contexts, something that seldom is found in any one individual. Thus, collaboration with one person who is more familiar and competent in the source language and context and someone with similar expertise and knowledge of the target context yields a much better result and makes up for the gaps of knowledge that either of the two collaborators may have. This apparently was routinely the case for English translations of Japanese poetry,37 and scholars also suggest that teaming up “a scholar and a poet” might be the most viable translation method for Native American poetry.38

Arriving now, at the end of this journey from the Rockies to the Amazon, I pause to take stock of the invaluable lessons learned, not only practical ones that involve the creation of anthologies but also more wide-ranging ones about the cultural positioning and contact between these two contexts and languages. Creating this anthology made us understand the importance of defining clear aims and criteria for inclusion while also resisting the idea of “representing” Canadianness in any definitive way. Still, the lack of contact or precedent meant assuming the responsibility of packaging, so to speak, this highly-textured writing, to ensure it would “travel well” from source to target. The process revealed fascinating points of aesthetic and cultural affinity as well as translation challenges which influenced our textual choices and ultimately also our translation strategies. Among these strategies, the most important feature was collaboration in both the editorial and translation work, pooling our individual talents to achieve creative solutions.

The process of producing this anthology was also instructive more generally for the way it raised interesting questions about the geopolitics of translation and the circulation of texts between these two nations—both the largest (geographically speaking) in the Northern and Southern hemispheres of the Americas, yet somehow traditionally marginalized for linguistic, cultural, political, and historical reasons: Canada vis-à-vis the United States, and Brazil vis-à-vis Spanish America. Likewise, the project presented us with the challenge of translating experimental writing from a hegemonic into a non-hegemonic language, a fascinating twist to the usual politicsof translation.39 In this case, by virtue of sheer numbers, could Canadian experimental writing gain more readership, visibility, and symbolic capital abroad than at home through translation into a “less prestigious” target language? Whether this is the case or not, this project, as any anthologizing activity, Odber de Baubeta contends, affords us a unique “understanding of how authors and their works cross geopolitical and linguistic borders to enter other cultural systems.”40

1. Quoted in Eliot Weinberger, “Anonymous Sources: A Talk on Translators and Translation,” in Voice-Overs: Translation and Latin American Literature, ed. Daniel Balderston and Marcy Schwartz (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2002), 113.

2. Our project, thus, followed the opposite route of what Tong-King Lee describes as “ littérisation, whereby literatures written in non-H[egemonic]-languages tend to be translated into H[egemonic]-languages in order to increase their visibility and symbolic capital in what Casanova calls the ‘world republic of letters.’” Tong-King Lee, “Translation and Language Power Relations in Heterolingual Anthologies of Literature,” Babel: Revue internationale de la traduction/International Journal of Translation 58, no. 4 (2012): 445.

3. This project would the first of its kind in Brazil, and it will be published by Editora da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina in 2018. A precedent in Portuguese is Pulllllllllll: Poesia contemporânea do Canadá, an anthology of Canadian contemporary poetry, which appeared in Lisbon in 2011. That anthology, discussed further below, understood “contemporary” as comprising three generations of poets born between 1925 and 1966, brought together under the sign of a poetic practice characterized by a radical questioning of language and by an abandonment of fossilized signification strategies. John Havelda, Isabel Patim and Manuel Portela, “Que sentido é o sentido que o sentido faz?” in Pulllllllllll: Poesia contemporânea do Canadá, ed. John Havelda, Isabel Patim and Manuel Portela (Lisbon: Antígona, 2010), 5.

4. Anthony Pym and Horst Turk, “Translatability,” in Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, ed. Baker Mona, 1st ed. (London; New York: Routledge, 1998), 273.

5. Jeffrey R. Di Leo, “Analyzing Anthologies,” in On Anthologies: Politics and Pedagogy, ed. Jeffrey R. Di Leo (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 2.

6. Armin Paul Frank and Helga Essmann, “Translation Anthologies: A Paradigmatic Medium of International Literary Transfer,” Amerikastudien/American Studies 35, no. 1 (1990): 30, 32.

7. Victor Mair, “Anthologizing and Anthropologizing: The Place of Nonelite and Nonstandard Culture in the Chinese Literary Tradition,” in Translating Chinese Literature, ed. Eugene Eoyang and Yao-fu Lin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 231. One of the problems that Mair mentions is “whether emphasis will be placed on a few authors or whether as many authors as possible should be included.” 231. Given that this would be a first anthology of this sort, we decided to include 25 authors, emphasizing comprehensiveness while still, within budget and time constraints, giving fair coverage to each author. Our selection includes: Marie Annharte Baker, Oana Avasilichioaei, Derek Beaulieu, Christian Bök, Clint Burnham, Edward Byrne, Louis Cabri, Angela Carr, Peter Culley, Jeff Derksen, Maxine Gadd, Dorothy Trujillo Lusk, Erín Mouré, Meredith Quartermain, Angela Rawlings, Lisa Robertson, Jordan Scott, ChristineStewart, Catriona Strang, Aaron Vidaver, Fred Wah, Darren Wershler, Lissa Wolsak, Rita Wong, and Rachel Zolf.

8. Margarida Vale de Gato, “The Collaborative Anthology in the Literary Translation Course,” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 9, no. 1 (2015): 51, accessed September 11, 2016, doi: 10.1080/1750399X.2015.1011901.

9. Robert Lecker, “Introduction,” in Anthologizing Canadian Literature: Theoretical and Cultural Perspectives, ed. Robert Lecker (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2015), 5.

10. Quoted by Di Leo, “Analyzing Anthologies,” 2.

11. As my co-translator, Luis Dolhnikoff remarked, Brazilians’ knowledge of North American poetry “often ends at the Great Lakes.” Luis Dolhnikoff, e-mail message to author, April 20, 2011.

12. Armin Paul Frank, “Anthologies of Translation,” in Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, ed. Mona Baker, 1st ed. (London; New York: Rout-ledge, 1998), 13. Frank describes this concept as “corpora whose constituent elements stand in some relation to each other either in space… or in time…. The arrangement, the configuration creates a meaning and value greater than the sum of meanings and values of the individual items taken in isolation, and translation anthologies are important manifestations of this phenomenon. For example, an anthology of world poetry embodies and projects the compiler’s image of the world’s best poetry,” 13.

13. Lecker, “Introduction,” 5.

14. Canadians, of course, have routinely had access to the various anthologies of Brazilian poetry published and/or distributed in the United States since Elizabeth Bishop’s 1972 An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Brazilian Poetry. However, the reception of these works in Canada is under-researched. Commentary on the translation of Brazilian poetry into English can be found in J. S. Dean Jr., “Crossing the Line from Portuguese to English,” Luso-Brazilian Review 10, no. 1 (1973): 120–140.

15. Concrete poetry, one of the most radical innovations of the postwar era in poetry, acquired a firm footing in Brazil through the work of the de Campos brothers (Haroldo and Augusto) and of Décio Pignatari, also avid translators of experimental writing by Joyce, Pound, Maykovsky, Khlebnikov, and cummings, among others.

16. In a recent co-authored article, Zilá Bernd, who with Joseph Melançon edited a pioneer anthology of Québecois writing, Vozes do Quebec (1991), notes that even today, “a literatura canadense ainda permanece distante do público leitor brasileiro que, com raras exceções… só tem acesso a ela no original, em língua inglesa ou francesa” [“Canadian literature is still far removed from Brazilian readers who, with rare exceptions… only have access to it in the original English or French”]. Zilá Bernd, Ana Maria Lisboa de Mello, and Eloína Prati dos Santos, “Vertentes atuais da literatura canadense de língua inglesa e francesa,” Letras de hoje Porto Alegre 59, no. 2 (April–June, 2015): 162, accessed January 27, 2017, doi: 10.15448/1984-7726.2015.2.21337.

17. Miguel Nenevé, “Translating Back P.K. Page’s Work: Some Comments on the Translation of Brazilian Journal into Portuguese,” Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 1, no. 3 (2003), 159.

18. Government of Canada, “Autores canadenses com publicações em português,” last modified August 15, 2013. www.canadainternational.gc.ca/brazil-bresil/cultural_relations_culturelles/authors-auteurs.aspx?lang=por.

19. “ABECAN,” last modified November 13, 2014. https://nelcfaam.wordpress.com/2014/11/13/%EF%BB%BFabecan/

20. revue ellipse mag No. 84–85 “Literatura contemporânea brasileira em tradução/ Contemporary Brazilian Writing in Translation / Littérature contemporainebrésilienne en traduction,” ed. Eloína Prati dos Santos and Sonia Torres, and coordinator Hugh Hazelton, (2010), 160 pp.

21. Christian Bök, an experimental writer whose book Eunoia (2002) became a bestseller, is mentioned in a couple of blogs, but his work appears untranslated. See “Modo de Usar & Co,” last modified September 19, 2008. http://revistamododeusar.blogspot.ca/2008/09/christian-bk.html. For the Brazilian writer Moacyr Scliar, Albert Braz notes, “new Brazilian writers are not particularly interested in formal experimentation.” Albert Braz, review of revue ellipse mag No. 84–85 “Literatura contemporânea brasileira em tradução / Contemporary Brazilian Writing in Translation / Littérature contemporaine brésilienne en traduction” ed. Eloína Prati dos Santos and Sonia Torres, and coordinator Hugh Hazel-ton, Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 11, no. 2 (2011): 188.

22. Spanning a much wider range in terms of generations and styles, this anthology included Robin Blaser, Christian Bök, Dionne Brand, Dennis Cooley, Jeff Derksen, Robert Kroetsch, Karen Mac Cormack, Steve McCaffery, Roy Miki, Erín Mouré, bpNichol, Lisa Robertson, and Fred Wah.

23. Havelda et al., “Introduction,” 6.

24. Mair, “Anthologizing and Anthropologizing,” 231.

25. Pym and Turk, “Translatability,” 276.

26. Lecker, “Introduction,” 14.

27. For discussion of some of these parallels, see my article, Odile Cisneros, “Contemporary Experimental Poetry in Canada and Brazil: Convergence and Contrast,” Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 13, no. 2 (2013): 139–152.

28. BBC Today. “Beautiful Vowels,” last modified October 30, 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_7697000/7697762.stm.

29. Christian Bök, Eunoia (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2001), 33.

30. Aragon abandons the strict metre and rhyme of Carroll’s original, a valid choice when translating poetry. More disappointingly, however, Aragon’s version largely glosses over the eight nonsense words from Carroll’s earlier poem “Jabberwocky” that appear in this poem too (bandersnatch, beamish, frumious, galumphing, Jubjub, mimsiest, outgrabe, and uffish), despite the fact that Carroll explains in the preface to the Snark, how these portmanteau words are created, thus providing a clue, indeed a strategy, for their translation: “For instance, take the two words ‘fuming’ and ‘furious.’ Make up your mind that you will say both words, but leave it unsettled which you will say first. Now open your mouth and speak. If your thoughts incline ever so little towards ‘fuming,’ you will say ‘fuming-furious’; if they turn, by even a hair’s breadth, towards ‘furious,’ you will say ‘furious-fuming’; but if you have that rarest of gifts, a perfectly balanced mind, you will say ‘frumious.’” Lewis Carroll, The Annotated Hunting of the Snark: The Full Text of Lewis Carroll’s Great Nonsense Epic The Hunting of the Snark, ed. Martin Gardner, Definitive ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2006), 10.

31. Perec’s lipogrammatic novel La disparition (1969) tells the story of the linguistic virtuoso punster Anton Voyl (Anton Vowl), who goes missing, just as the letter “e” disappears from the entire novel. The choice of constraint here alludes both to Georges Perec’s name, where that letter appears 4 times, but also Perec’s family disappeared during the Holocaust. Adair’s version, A Void (1994) reproduces the story with the same constraint. Amazingly, this novel has another translation, by John Lee, under the title Vanish’d. Perec also wrote a complementary univocalic novel, Les revenentes (1972) translated by Ian Monk in 1996 as The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex. See the articles in the special issue of Palimpsestes in the bibliography.

32. Unless otherwise noted, all Portuguese translations of poems were co-authored by Luis Dolhnikoff and Odile Cisneros.

33. Christian Bök, Crystallography, 2 rev ed. (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2003), 20.

34. Haroldo de Campos et al., “Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry,” in Novas: Selected Writings, trans. Jon Tolman, ed. Haroldo de Campos, Antonio Sergio Bessa and Odile Cisneros (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007), 217–219.

35. Aaron Vidaver, Email communication with the author, September 11, 2013.

36. Oana Avasilichioaei, Email communication with the author, May 18, 2011.

37. Jeremy Munday mentions that when translating from Japanese or Hebrew, the American poet John Silkin “depended absolutely on his co-translators to provide a reliable literal [version] for him to work on. But this type of arrangement was common in the translation of Japanese poetry.” Jeremy Munday, “Jon Silkin as Anthologist, Editor and Translator,” Translation and Literature 25 (2016): 99, accessed September 9, 2016, doi: 10.3366/tal.2016.0238.

38. Arnold Krupat and Brian Swann, “Of Anthologies, Translations, and Theory: A Self-Interview,” North Dakota Quarterly 57, no. 2 (Spring 1989): 138.

39. Tong-King Lee writes, “When literary works written in non-H-languages are translated into this H-language, they claim a wider readership than if they were to remain untranslated in their original language of composition.” Lee, “Translation and Language Power Relations,” 446.

40. Patricia Odber de Baubeta, quoted by Gato, “The Collaborative Anthology,” 52.

“Abecan.” Last modified November 13, 2014. https://nelcfaam.wordpress.com/2014/11/13/%EF%BB%BFabecan/

Avasilichioaei, Oana. Email communication with the author, May 18, 2011.

BBC Today. “Beautiful Vowels,” last modified October 30, 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/today/hi/today/newsid_7697000/7697762.stm

Bernd, Zilá, Ana Maria Lisboa de Mello, and Eloína Prati dos Santos. “Vertentes atuais da literatura canadense de língua inglesa e francesa = Current Perspectives on Canadian Literature in English and French.” Letras de hoje 50, no. 2 (2015): 162–167, accessed January 27, 2017, doi: 10.15448/1984-7726.2015.2.21337.

Bök, Christian. Crystallography. 2nd rev ed. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2003.

———. Eunoia. Toronto: Coach House Books, 2001.

Braz, Albert. “Review of Revue Ellipse Mag no. 84–85 ‘Literatura Contemporânea Brasileira Em Tradução/Contemporary Brazilian Writing in Translation/Littérature Contemporaine Brésilienne En Traduction’ Ed. Eloína Prati dos Santos and Sonia Torres, and Coordinator Hugh Hazelton.” Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 11, no. 2 (2011): 187–190.

Campos, Haroldo de, and et al. “Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry.” In Novas: Selected Writings, Haroldo de Campos, translated by Jon Tolman, edited by Antonio Sergio Bessa, Odile Cisneros and Roland Greene, 217–219.Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2007.

Carroll, Lewis. The Annotated Hunting of the Snark: The Full Text of Lewis Carroll’s Great Nonsense Epic the Hunting of the Snark, ed. Martin Gardner, Definitive ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2006.

———. La Chasse au Snark: Une Agonie en huit crises, translated by Louis Aragon. Chapelle-Réanville, Eure: Hours Press, 1929.

Cisneros, Odile. “Contemporary Experimental Poetry in Canada and Brazil: Convergence and Contrast.” Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 13, no. 2 (2013): 139–152.

Dean, J. S., Jr. “Crossing the Line from Portuguese to English.” Luso-Brazilian Review 10, no. 1 (1973): 120–140.

Di Leo, Jeffrey R. “Analyzing Anthologies.” In On Anthologies: Politics and Pedagogy, edited by Jeffrey R. Di Leo, 1–26.Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

Frank, Armin Paul. “Anthologies of Translation.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, edited by Mona Baker. 1st ed., 13–16.London; New York: Routledge, 1998.

Frank, Armin Paul and Helga Eßmann. “Translation Anthologies: A Paradigmatic Medium of International Literary Transfer.” Amerikastudien/American Studies 35, no. 1 (1990): 21–34.

Gato, Margarida Vale de. “The Collaborative Anthology in the Literary Translation Course.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 9, no. 1 (2015): 50–62, accessed September 11, 2016, doi: 10.1080/1750399X.2015.1011901.

Government of Canada. “Autores canadenses com publicações em português,” last modified August 15, 2013. www.canadainternational.gc.ca/brazil-bresil/cultural_relations_culturelles/authors-auteurs.aspx?lang=por

Havelda, John, Isabel Patim, and Manuel Portela. “Que sentido é o sentido que o sentido faz?” In Pulllllllllll: Poesia Contemporânea do Canadá, edited by John Havelda, Isabel Patim, and Manuel Portela, 5–7.Lisbon: Antígona, 2011.

———, eds. Pulllllllllll: Poesia Contemporânea do Canadá. Lisbon: Antígona, 2011.

Krupat, Arnold and Brian Swann. “Of Anthologies, Translations, and Theory: ASelf-Interview.” North Dakota Quarterly 57, no. 2 (Spring, 1989): 137–147.

Lecker, Robert. “Introduction.” In Anthologizing Canadian Literature: Theoretical and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Robert Lecker, 1–33.Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2015.

Lee, Tong-King. “Translation and Language Power Relations in Heterolingual Anthologies of Literature.” Babel: Revue Internationale de la Traduction/ International Journal of Translation 58, no. 4 (2012): 443–456.

Mair, Victor H. “Anthologizing and Anthropologizing: The Place of Nonelite and

Nonstandard Culture in the Chinese Literary Tradition.” In Translating Chinese Literature, edited by Eugene Eoyang and Yao-fu Lin, 231–261.Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

“Modo de Usar & Co.” last modified September 19, 2008. http://revistamododeusar.blogspot.ca/2008/09/christian-bk.html

Munday, Jeremy. “Jon Silkin as Anthologist, Editor, and Translator.” Translation &Literature 25, no. 1 (Spring, 2016): 84–106, accessed September 9, 2016, doi:10.3366/tal.2016.0238.

Nenevé, Miguel. “Translating Back P.K. Page’s Work: Some Comments on the Translation of Brazilian Journal into Portuguese.” Interfaces Brasil/Canadá 1, no. 3 (2003): 159–169.

Palimpsestes: Traduire la littérature des Caraïbes; La Plausibilité d’une traduction: Le Cas de La Disparition de Perec. Edited by Christine Raguet-Bouvart and SaraR. Greaves. Vol. 12.Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne nouvelle, 2000.

Perec, Georges. A Void, translated by Gilbert Adair. London: Harvill, 1994.

———. La Disparition, Roman. Paris: Les Lettres nouvelles, 1969.

Pym, Anthony and Horst Turk. “Translatability.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies, edited by Mona Baker. 1st ed., 273–277.London; New York: Routledge, 1998.

Vidaver, Aaron. Email communication with the author, September 11, 2013.

Weinberger, Eliot. “Anonymous Sources: A Talk on Translators and Translation.”

In Voice-Overs: Translation and Latin American Literature, edited by Daniel Balderston and Marcy Schwartz, 104–118.lbany: State University of New York Press, 2002.