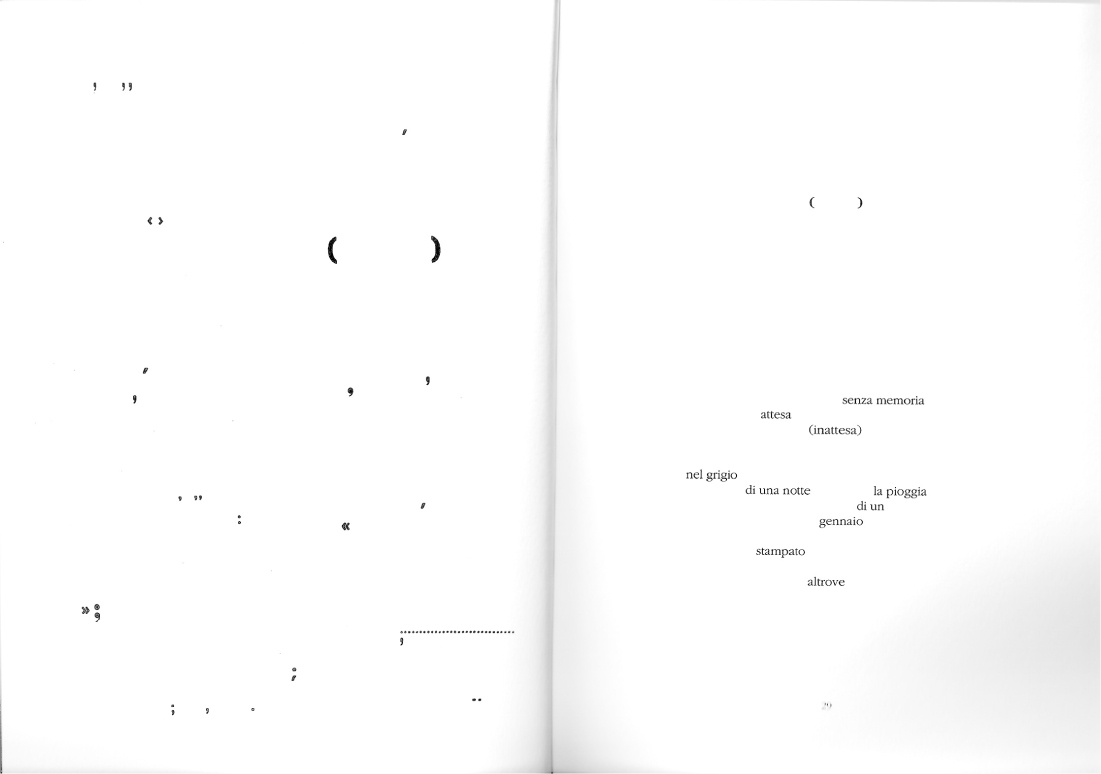

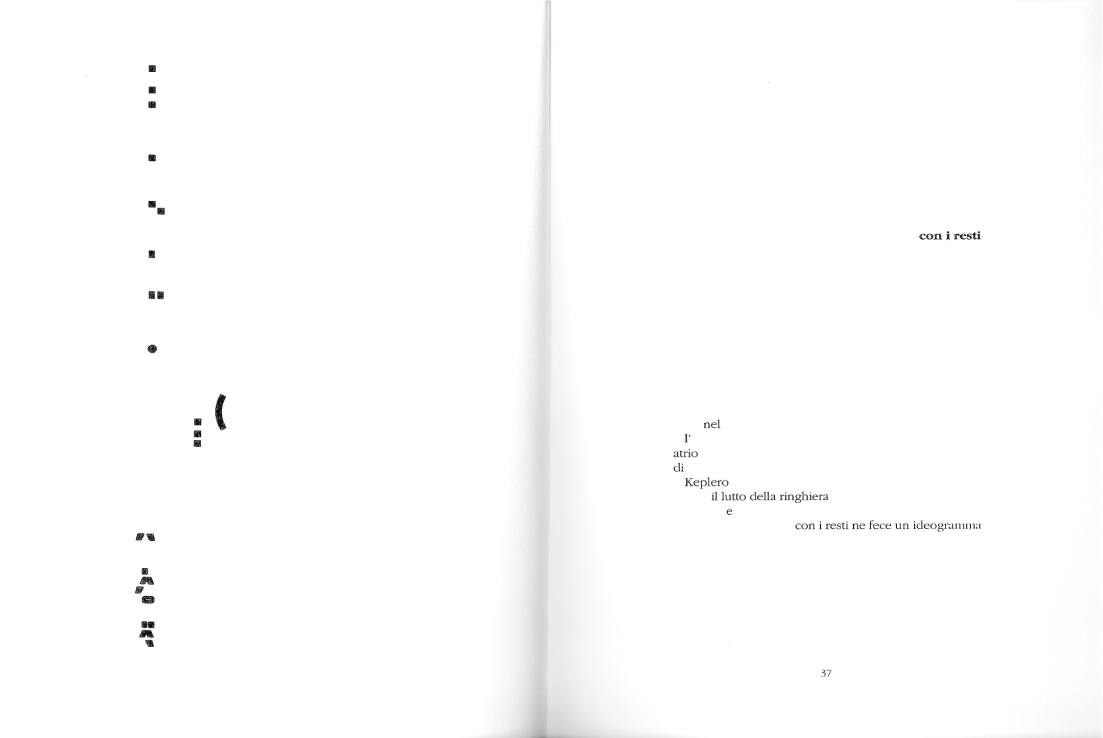

Figure 7.1 Two-page spread of Giovanna Sandri’s “creazione illimitata”

Translating Giovanna Sandri’s clessidra: il ritmo delle tracce

In the mid-1960s Italian poet Giovanna Sandri (1923–2002) began using dry-transfer lettering to create abstract graphic compositions that would come to be featured in exhibitions of visual and concrete poetry internationally, as well as in the Quadriennale di Roma (1968) and the Biennali di Bolzano (1969), di Venezia (1978), and de São Paulo (1981). Her unique visual texts, which would soon share the page with verbal texts, were also the subject of two solo exhibitions: “alfabeto/albero del Tempo” [“alphabet/ tree of Time”] at the Galleria Civica d’Arte Modena, Palazzo Te, Mantua (1977), and “erörtern (occhi/tarocchi per estrarre segni)” [“erörtern (eyes/ tarots for extracting signs”] in the Libreria Internazionale oolp, Turin (1978). Though she also wrote purely verbal poems, her entire body of work is characterized by an exploration of the graphic qualities of written signs and a preoccupation with the formal composition of the poetic text, traits that present interesting challenges for the translator.

Sandri’s books range from volumes of strictly visual poetry, to strictly verbal poetry, to a hybrid of the two.1 In all cases, the poetic text is like a drawing or painting in that its unique shape and position on the page are integral parts of its overall composition. Furthermore, in certain of her books the basic poetic unit is not the single page but the two-page spread, and in such cases the notion of the poem expands to include the binary of texts appearing on facing verso and recto pages. It goes without saying that all of these elements, in addition to semantic “content” of course, must be taken into account in the translation of her work.

I began translating Sandri in 1995, when Paul Vangelisti asked me for an English version of her poem “origine lunare dell’alfabeto” (1978) for a journal he was editing at the time.2 I have translated other works of hers over the years, both individual poems and complete books, for publication in journals, as chapbooks, and most recently in the volume of her selected poems.3

In the remarks that follow, I would like to focus on the translation of one book in particular— clessidra: il ritmo delle tracce—and share excerpts from an exchange I had with the author during the translation process.4

Recipient of the 1992 Premio Lorenzo Montano, clessidra is a beautiful if slim volume of hybrid, verbo-visual poems of the kind mentioned above, the visual texts all being repurposed from her first book, Capitolo Zero [“Chapter Zero”]. Luigi Ballerini, a close friend of Sandri’s, brought me a copy of clessidra, a gift from the author, in November 1996. The work immediately appealed to me and I soon began to translate it. By this time I was corresponding with Sandri and was thus able to ask her about the poems and, since she knew English, send her my versions to look over. She received a complete draft of the translation in February 1997 and wrote back in May, sending me her suggestions and annotations either handwritten on the proofs themselves in the case of minor corrections or changes, or typewritten on a half-sheet of paper and stapled to the proofs in the case of lengthier commentary. In the letter that accompanied them, she wrote:

here are your beautiful translations sliding throughout the white pages as I expected: even in English they keep the flowing rhythm you succeeded in perceiving, not to speak about your visualization

(and rhythm in its Greek etymology is linked to the verb to flow )

if I compare your translations with mine, I see yours have a more abstract, impersonal flavor

(see encounter, far better than meeting: I translated in the words/she meets/but fragments/she finds, while you, in the words/encountered/only frag/ments found, far, far better, bravo)5

[…]

you’ll find my suggestions/corrections in the notes I have written for some poems, when my interpretation is different, and please let me know if you agree with them as my English may create some problems. I also added some personal references as, even if I haven’t yet met you personally, I like to dialogue with you through these notes6

In those translations that Sandri annotated, she felt that I had either misunderstood a word or passage or considered that it could have been rendered more effectively. In the alternate renderings she proposed she occasionally allowed herself changes that, as a translator, I wouldn’t have considered, or perhaps even thought of, had she not brought them up. The first such poem I will give here is “creazione illimitata” [“limitless creation”], reproduced on page 79. On top inFigure 7.1 you have the two-page spread from the original Italian edition, and below inFigure 7.2 Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of my translation (they cover the visual part of the poem on the facing page).

Figure 7.1 Two-page spread of Giovanna Sandri’s “creazione illimitata”

Figure 7.2

Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of Guy Bennett’s translation, “limitless creation”

even if your translation is so beautiful ( the one/who/lets/go ) it doesn’t convey an unexpected further maening [sic] which came out from my subdivision of the line:

“la freccia/del/Tempo/com/pensa/quel/che/ la/scia/ cader/e //,”

: the subdivision of the verb lascia (la/scia) let emerge la scia (its trail), which led me to translate:

“the arrow/of/Time/com/pensate [sic]/what/its/trail/lets/fal/l //,”: that’s what happens letting words dance from one language to another

As we see, Sandri takes advantage of the passage into English—i.e. “letting words dance from one language to another”—to make explicit a potential double meaning of the Italian verb. By giving both the noun (“its trail”) and the verb (“lets”) in English, she introduces a new meaning (i.e. that it is the trail that lets fall, not the arrow of Time, the agent of the action in the Italian text) that is at best latent in the original. In other words, she uses the translation process to creatively alter the poem. She does something similar with “( ),” reproduced below inFigure 7.3.

Figure 7.3

Sandri’s original poem “( )”

In her notes to this translation, Sandri suggests an alternate version for the first stanza, which in Italian reads: “senza memoria/attesa/(inattesa),” and which I had rendered, rather flatly I feel in retrospect, as “without expected/(unexpected)/memory.” She writes:

sometimes an extreme conciseness may be misleading: in your translation it has been focused the reader’s attention [sic] on memory, and omitting its absence ( senza ) the meaning has been misunderstood

in Italian attesa (inattesa) may look like a contradiction, but as in English there are two verbs (to wait for, to expect), they can express the shade of meaning I tried to convey: “free from memory/an aimless wait/ (unexpected)”

Figure 7.4

Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of Bennett’s translation, “( )”

Her version is definitely the more interesting, but it is also far enough away from the original that I wouldn’t have imagined it, or permitted myself to use it without her permission if I had. Translating “senza memoria” as “free from memory,” and “attesa” as “an aimless wait,” Sandri is introducing nuances (“to be free from” and “aimless”) not present in the original. They are at best interpretations, as the rest of her annotation makes clear:

in that psychologic state of inner Void, memories disappear ( free from memory ) and one may experience the flowing of life, open to the verystreaming forth, free from any expectation: open presumes a sort of wait for what one is open to: omitting for, an unconscious wait emerges, rid from any aim (that’s why I translated an aimless wait ): unexpectedly it emerges, so your ( unexpected ) is simply perfect

[…]

I quite remember when these lines were written: it was a Winter night rain went on wrapping silence and stillness breathrhythm let pure detachment spread around its halo (memories disappeared) on lifting the windowcurtain that present gray rainy night was seen from an indefinite distance, peculiar to that state of psychic experience

(simple, isn’t it ?!

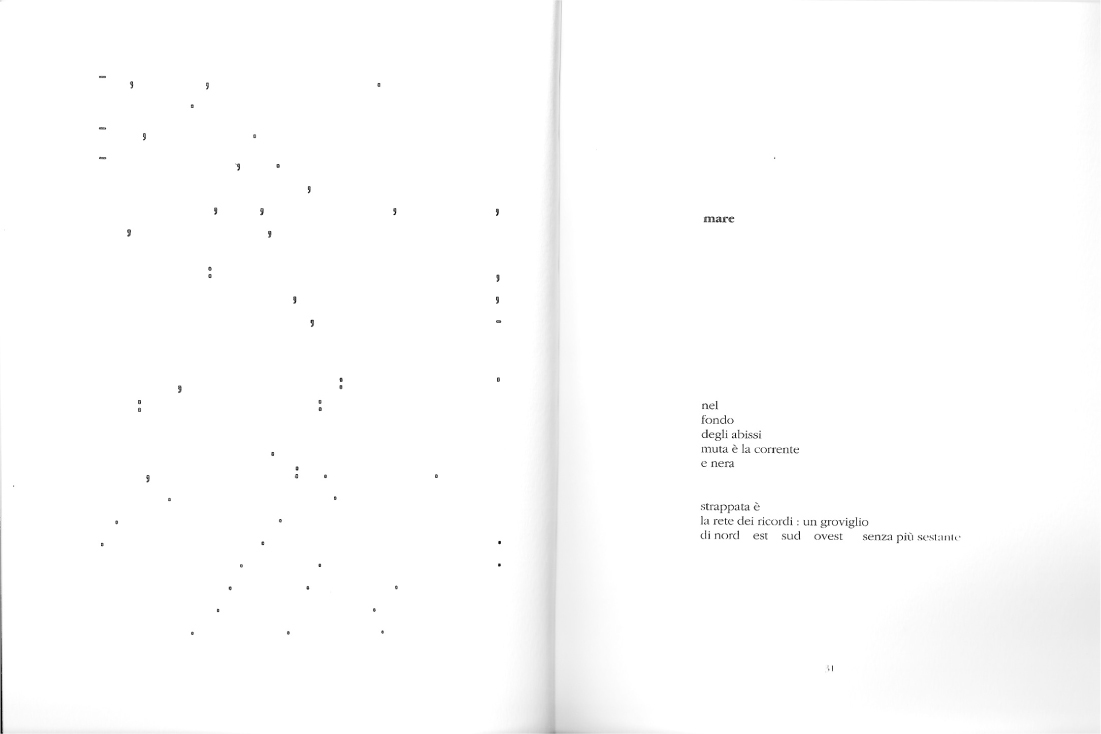

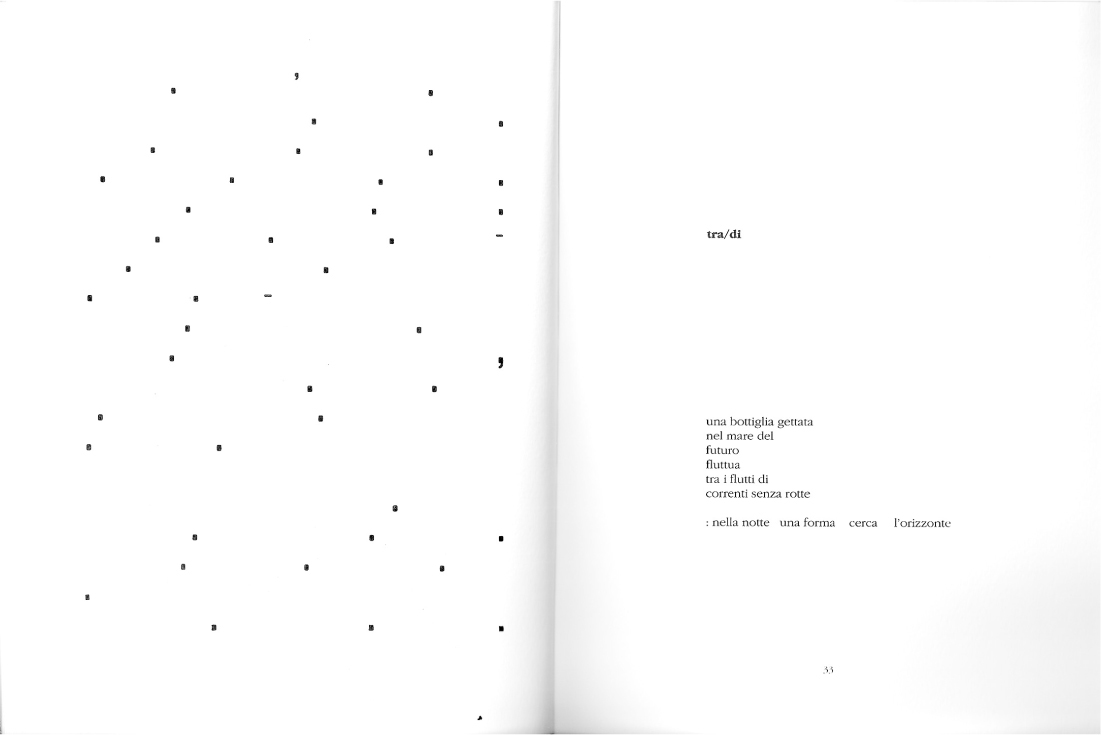

Of all of the poems that make up clessidra, the texts of only two were set “hard left,” that is, the verses were not articulated spatially on the page as they were in all of the other poems; they aligned on the left, as poems traditionally do. In her notes, Sandri speculated that she had apparently not had the time to “visualize” them, as she put it, before sending them off to the publisher, so she proposed to visualize the translations in order “to improve [the English] edition.” The poems in question are “mare” [“sea”] and “tra/

di” [“on/of”] (seeFigures 7.5,7.6,7.7, and7.8 on pages 82–84).

Figure 7.5

Sandri’s original poem “mare”

As we see in her annotations, she completely recast both of the translated poems, breaking nearly all of the lines differently and splitting the long, final lines into multiple new ones. Furthermore, in “sea” she reformed the stanzas, moving the first line and first word of the second line of the second stanza to the end of the first stanza, which now concludes with a colon. In “on/of” she

Figure 7.6

Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of Bennett’s translation,

“sea”

Figure 7.7

Sandri’s original poem “tra/di”

shifts the colon that introduces the final line to the end of the poem, where in effect it becomes the final stanza, finishing the poem on an “open” note.7

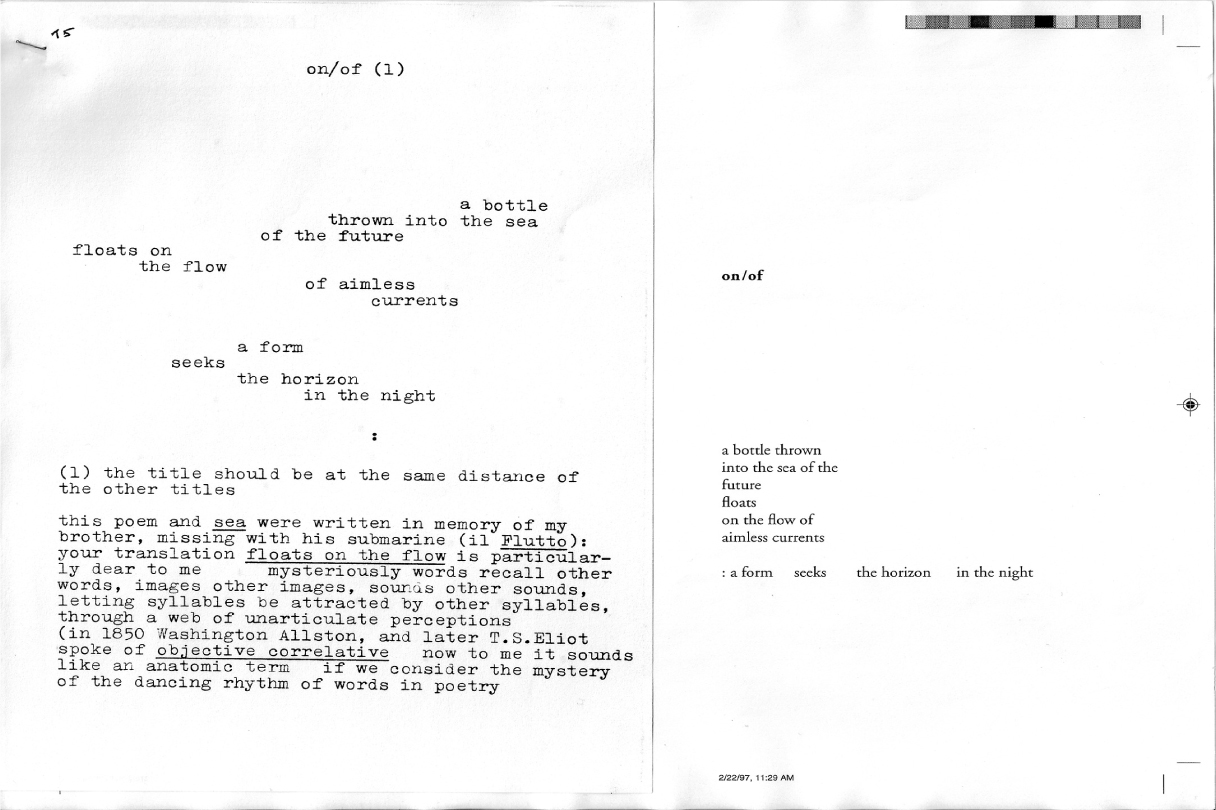

Figure 7.8 Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of Bennett’s translation, “on/of”

The recasting of these poems is significant, I believe, in that it suggests that a “visualized” poem may well have different phraseological “needs” than a poem traditionally set. Evidently, it was not enough to merely indent the lines written as they were; they needed to be rewritten in view of the poems’ new shape, which in turn suggests that for Sandri, the shape of a poem takes precedence over the linear articulation of its constituent lines when set conventionally. As she did with “( ),” she also explains the origins of these two poems and comments briefly on their semantic content:

this poem and sea were written in memory of my brother, missing with his submarine (il Flutto ): your translation floats on the flow is particularly dear to me mysteriously words recall other words, images other images, sounds other sounds, letting syllables be attracted to other syllables, through a web of unarticulate perceptions (in 1850 Washington Allston, and later T.S. Eliot spoke of objective correlative now to me it sounds like an anatomic term if we consider the mystery of the dancing rhythm of words in poetry

Given the subject matter of these poems, I had initially “read” the visual texts appearing on the verso pages as specular highlights on the ocean surface. Infact, these pieces were not intended to be representational—Sandri created them from a page of Joyce’s Ulysses (specifically, p. 440 of the Bodley Head edition, containing the “description of confraternities (At the sound of the sacred bell)”), removing all of the words and retaining only the punctuation. Several pieces in Capitolo Zero were made in this way, in order, she explained, to reveal the rhythm of the writing, il ritmo delle tracce, as the book’s subtitle has it.8

The final example I would like to consider is the poem “con i resti” [“with the rest”] (seeFigure 7.9 and7.10 on pages 85–86).

Figure 7.9

Sandri’s original “con i resti”

The poem reads, “nel/l’/atrio/di/Keplero/il lutto della ringhiera/e // con i resti ne fece un ideogramma,” which I translated as, “in/Kepler’/s / atrium/a banister in mourning/and // made an ideogram with the rest.” Sandri suggested that I reword the final line to read, “an ideogram was made with the rest,” a minor but not insignificant change, explaining that:

sometimes the white space between the first part of a poem and the last line (or lines) allows a sudden image to emerge, as an unexpected reaction to the former lines

in this case (made an ideogramm [sic] with the rest) made is related to a banister in mourning (bravo), and the reaction is quite conveyed but in my translation there is (am I wrong?) a stronger snap to the stemma of the ideogramm, snap due to its being unrelated it seems to me that as subject of the statement, an ideogramm (uffa) conveys other shades of expressiveness (?): who made it? when was it made?

One might wonder whether Sandri only noticed that the line could be improved after the fact, or whether she felt that, for whatever reason, only the English version of the poem needed improvement. Whatever the case may be, it is clear that for her, strict fidelity to the original was less important than creating what she felt would be a strong(er) English version, even if this meant altering aspects of the Italian text (in this case, going from an active to a passive construction, with the syntactic and positional changes that that implies) to do so.

Figure 7.10

Sandri’s typewritten notes stapled to the page proof of Bennett’s translation, “with the rest”

Given her suggested revisions in each of the cases mentioned above, for the purposes of translation it seems that Sandri considered the original versions of her poems latent works that could be altered and manipulated as desired as they are rendered in another language (and this beyond the alterations and manipulations implicit in the act of interlingual translation itself). Just as a photographic negative can be cropped to change the overall composition and printed intentionally darker or lighter, whether in whole or in parts, than the latent image it contains, so too, she apparently felt, can the poem be retouched, reshaped even—in a word, rewritten—in the target language, whether to take advantage of possibilities not available in the source language, to update the poem based on her later vision of it, or to compensate for perceived shortcomings in it.

This leads to the somewhat unusual situation in which there is no longer a single “author original,” so to speak, but two, since several of the published Italian versions were re-imagined by the author as they were brought into English and subsequently differ, in some cases significantly, from her initial iteration of them. Though this is not an example of self-translation strictly speaking—after all I was free to incorporate Sandri’s suggestions or not (and in most cases I did)—it does bear the mark of this practice as Sandri’s rewritings move the English versions further from the Italian texts than I would have felt comfortable taking them. In fact, the whole experience corroborates Anthony Cordingley’s truism that “self-translators bestow upon themselves liberties of which regular translators would never dream,” and gives weight to his assertion that “self-translation typically produces another ‘version’ or a new ‘original’ of a text.”9 Not coincidentally (or entirely without irony), it also illustrates Borges’ seemingly paradoxical observation that El original es infiel a la traducción [“The original is unfaithful to the translation.”].10

It is interesting to consider the choice facing future translators of clessidra, should there be any: Will they work uniquely from the Italian texts, or will they take the English versions into account as well? Were I to find myself in such a position, I should like to work from both, since the (re)writings discussed above represent an author-sanctioned range of possibilities for further renderings. In fact, one might even argue that the English version is the “definitive” one—at the very least in the case of the two “visualized” poems, “mare” and “tra/di”—just as a “revised and corrected” edition of a given work would be considered so, as Sandri herself suggested in reference to the latter two poems. Whatever the case may be, while it is certainly true that having more than one “author original” to work from makes for a richer palette, it also complicates the task of the translator, who must now deal with two iterations of a text as s/he writes a third. I suppose that that, too, is a consequence of “letting words dance from one language to another.”

Books by Giovanna Sandri

Capitolo Zero. Rome: Lerici Editore, 1969.

da K a S (dimora dell’asimmetrico) | from K to S (ark of the asymmetric), translated by Faust Pauluzzi. New York, Norristown, Milan: Out of London Press, 1976.

alfabeto/albero del Tempo. Mantua: Galleria civica d’arte moderna, Palazzo Te, 1977.

dal canguro all’aithyia (o come farsi scrittura). Rome and Venice: le parole gelate, 1981.

Hermes the Jolly Joker. Rome and Venice: le parole gelate, 1983; second edition, 1994.

Giovanna Sandri. Spec. issue of Le Parole rampanti 8 / 9, 1988.

clessidra: il ritmo delle tracce. Verona: Anterem Edizioni, 1992.

hourglass: the rhythm of traces, translated by Guy Bennett. Los Angeles: Seeing Eye Books, 1998.

le dieci porte de Zhuang-zi | the ten Gates of Zhuang-zi, translated by Giovanna Sandri. Rome: le parole gelate, 1994.

noi campagni di Ulisse (Argonauti dispersi. Milan: Archivio di Nuova Scrittura, 1998.

only fragments found: selected poems, 1969–1998. Edited by Guy Bennett, translated by Faust Pauluzzi, Giovanna Sandri, and Guy Bennett. Los Angeles: Otis Books | Seismicity Editions, 2014.

1. See her books Giovanna Sandri, Capitolo Zero (Rome: Lerici Editori, 1969); From K to S: Ark of the Asymmetric (New York, Norristown, Milano: Out of London Press, 1976); Dal canguro all’aithyia (o come farsi scrittura) (Rome: Le parole gelate, 1980).

2. “lunar origin of the alphabet” appeared in Ribot 3 (1995): 134–136. The Italian original was first published in Le Parole rampanti 8/9 (1988), a special double-issue devoted to her work.

3. Giovanna Sandri, only fragments found: selected poems, 1969–1998, ed. Guy Bennett, trans. Faust Pauluzzi, Giovanna Sandri, and Guy Bennett (Los Angeles: Otis Books | Seismicity Editions, 2014).

4. My translation of Giovanna Sandri’a clessidra was published as hourglass: the rhythm of traces (Los Angeles: Seeing Eye Books, 1998).

5. This is the second and final stanza of the poem “incontro.”

6. Sandri, Giovanna. Letter to the author, May 25, 1997. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are from this letter.

7. Sandri occasionally ended poems, even books, with commas, colons, equals signs, etc., as if to suggest that the text is to be continued in the mind of the reader.

8. In the copy of Capitolo Zero which she gave me, Sandri slipped typewritten notes between certain pages to explain their origins and comment on their contents. Thus I learned that she appropriated and manipulated in this way pages from Joyce, Addison, Dylan Thomas, and an unidentified essay in structural linguistics, in each case analyzing the rhythm suggested by the remaining punctuation. This is undoubtedly what she was referring to in clessidra’s subtitle: il ritmo delle tracce.

9. Anthony Cordingley, “Introduction: Self-translation, going global,” in Self-Translation: Brokering Originality in Hybrid Culture, ed. Anthony Cordingley (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), 2.

10. Jorge Luis Borges, “Sobre el ‘Vathek’ de William Beckford,” La Nación, April 4, 1943, 1. Collected in Otras inquisiciones, Obras completes, Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1989, II, 110. Translation: “On William Beckford’s Vathek,” Selected Non-Fictions, ed. Eliot Weinberger (Penguin Books, 1999), 239.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “Sobre el ‘Vathek’ de William Beckford.” In La Nación, 1.April 4, 1943.Collected in Otras inquisiciones, Obras completes, Buenos Aires: Emecé, 1989, II, 110.Translation: “On William Beckford’s Vathek,” Selected Non-Fictions, ed. by Eliot Weinberger, Penguin Books, 1999, 239.

Cordingley, Anthony. “Introduction: Self-translation, Going Global.” In Self- Translation: Brokering Originality in Hybrid Culture, edited by Anthony Cord-ingley, 1–10.

London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Sandri, Giovanna. Capitolo Zero. Rome: Lerici Editore, 1969.

———. da K a S (dimora dell’asimmetrico) | from K to S (ark of the asymmetric), translated by Faust Pauluzzi. New York, Norristown, Milan: Out of London Press, 1976.

———. dal canguro all’aithyia (o come farsi scrittura). Rome and Venice: le parole gelate, 1981.

———. only fragments found: selected poems, 1969–1998. Edited by Guy Bennett, translated by Faust Pauluzzi, Giovanna Sandri, and Guy Bennett. Los Angeles: Otis Books | Seismicity Editions, 2014.

“Sobre el ‘Vathek’ de William Beckford.” La Nación, April 4, 1943, 1.