Chapter I.1.6

Role of Water in Biomaterials

In the world there is nothing more submissive and weak than water. Yet for attacking that which is hard and strong nothing can surpass it.

Lao Tzu

Water! Omnipresent, inert, a simple diluent – these words come to mind and prompt the question: “why is there a section of this textbook devoted to water?” The special properties of water, this substance that is critical for life as we know it, significantly impact the “materials-centric” subject of biomaterials, and the biology closely associated with biomaterials. Water is a unique, remarkable substance – in this instance, the word “unique” can be used without hyperbole. Although its chemical composition was elucidated in the 1770s by Lavoisier and others, its liquid structure continues to be explored today using state-of-the-art physical characterization methods. The importance of water for life as we know it was appreciated as early as 1913 in an interesting historical volume, The Fitness of the Environment (Henderson, 1913; available in reprint).

This chapter will first introduce the physical and chemical properties of water. Then water’s significance for biomaterials and biology will be expanded upon.

Water: The Special Molecule

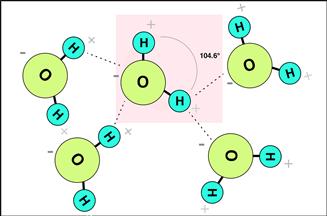

The simple “H2O” structure of the water molecule does not immediately communicate the ability of one water molecule to interact with many other water molecules, in particular to interact not too strongly, and not too weakly. This interaction, largely via the hydrogen bond, is associated with the dipole of the water molecule (slightly more negatively charged at the oxygen and positively charged at the hydrogen, i.e., partial negative and positive charges). This dipole, combined with the bent shape (bond angle of 104.6°) of the molecule and its small size contributes to the special properties of liquid water. Figure I.1.6.1 illustrates schematically the geometry of the water molecule, and suggests some hydrogen bonding possibilities with neighboring water molecules (as well as the occasional H+ or OH−).

The physical properties of water are profoundly unique compared to all other substances.

FIGURE I.1.6.1 Schematic illustration of five water molecules suggesting their geometry and dipole. A hydrogen bond is represented by a dotted line. Consider the many possibilities for these electrostatic (charge) interactions.

The unique physical and chemical properties of water, attributable to the 104.6° bond angle and the ability to form multiple hydrogen bonds, are discussed here. Note how special water is compared to other liquid and solid substances.

Melting Point and Boiling Point

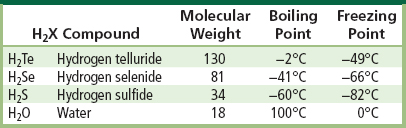

The physical properties of H2O that make it stand out from all other related molecules are best appreciated from the data in Table I.1.6.1.

TABLE I.1.6.1 Boiling Point and Freezing Point of Water Contrasted to Other H2X Compounds

As the molecular weight for compounds in this series of related molecules decreases, the boiling points also decrease, until you reach water, where the boiling point is (unexpectedly) up to 160°C higher. At common temperatures and pressures on earth, all the other compounds exist as gases, except water. A similar dramatic trend is seen in freezing point.

Density and Surface Tension

Water has a density of 0.997 g/ml at 25°C. As the temperature decreases, water, like most substances, increases in density, until 4°C where its density is 1.00 g/ml. Then, as temperature is decreased further, an unusual phenomenon is observed. The density decreases as the temperature is lowered. At 0°C, the density is 0.92 g/ml. Thus, ice floats on liquid water. There is special significance to this. If bodies of water froze from the bottom to the top (i.e., if ice were heavier than water), during cold periods in earth’s geological history most aquatic life might have been destroyed.

Surface tension is a measure of the magnitude of cohesive forces holding molecules together. For substances at ambient temperature and pressure, water has the highest surface tension with one exception – mercury. The water surface tension is 72.8 dyne/cm. Compare this to, for example, ethanol at 22.3 dyne/cm (mN/m) and ethylene glycol at 47.7 dyne/cm. This surface tension permits a water strider insect (family Gerridae) to transport across lakes riding on the “surface skin” of water, a metal paper clip to float (Figure I.1.6.2), and assists with the transport of water from soil to the tops of tall trees.

FIGURE I.1.6.2 A metal paper clip floats on the water surface “skin,” a manifestation of water’s high surface tension.

(Photograph by Buddy Ratner.)

Specific Heat and Latent Heats of Fusion and Evaporation

Water has a specific heat of 1.0 calorie/g°C, that is, the heat per unit mass required to raise the temperature of water 1°C. For comparison, copper has a specific heat of 0.1 cal/g°C, and ethyl alcohol has a specific heat of 0.6 cal/g°C. Water has a higher specific heat than any other common substance. Related to the specific heat is the latent heat of fusion or evaporation. The latent heat is the energy in calories per gram taken up or released by matter changing phase (liquid/solid or solid/liquid) with no change in temperature. Again, water has anomalously high values compared to other common substances.

Water as a Solvent

Water is a remarkably powerful and versatile solvent. It will dissolve proteins, ions, sugars, gases, many organic liquids, and even lipids (up to the critical micelle concentration). In fact, it is the most versatile solvent that we know.

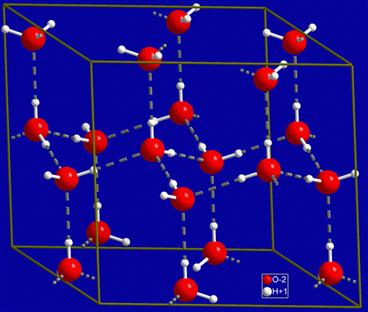

Water: Structure

Figure I.1.6.1 suggests that water can form extended hydrogen bonding structures. These structures grow in three dimensions. The molecular crystal structure of ice is shown in Figure I.1.6.3. At temperatures of 0°C and below, thermal fluctuations of molecules (referred to as kT vibrations) are low and a continuous, ordered three-dimensional network of water molecules can form. The hydrogen bonds in water are relatively low strength, approximately 5 kcal/mol (21 kJ/mol); in contrast, a C–H bond is approximately 100 kcal/mol. At room temperature, the thermal fluctuations of water molecules can disrupt this H-bond association – if it were not so, water would coalesce into a solid at room temperature. An oft-cited model of water molecule organization suggests that disrupted groupings of water molecules rapidly form new clusters (dimers, trimers, tetramers, pentamers, hexamers, etc.) (Keutsch and Saykally, 2001). This is the “flickering cluster” model of water structure. More recently, it has been established that liquid water is closer to a hydrogen-bonded continuum with much bond angle distortion from the tetrahedral organization seen in the ice structure, and with bonds breaking and reforming so rapidly (in the order of 200 femtoseconds), that the cluster model is not an accurate description (Smith et al., 2005). The continuum model is now the most accepted model for water structure, through there is still much controversy about water structure, and new insights are frequently reported.

FIGURE I.1.6.3 The hexagonal ice structure. (Wikipedia public domain image.)

The water structure discussion, above, applies to bulk, pure water. The water continuum organization can be disrupted or reorganized by dissolved ions or solutes, by absorption into hydrophilic polymers (hydrogels when the polymer is cross-linked), and by solid surfaces. Each of these cases will be very briefly addressed.

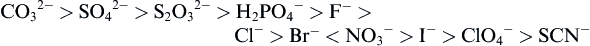

Dissolved ions and solutes may have a profound impact on water organization (Marcus, 2009). Dissolved salts are dissociated to form an anion and a cation, with each ion having a shell of water of different structure from the bulk. This hydration shell perturbs the structure of water adjacent to it (Marcus, 2009). Much of the study of dissolved ions has centered around studies of the Hofmeister series of anions:

Ions to the left of the series are referred to as kosmotropes – they generally precipitate proteins from solution and inhibit denaturation. Ions on the right side of the series are considered chaotropes, and these increase protein solubility and are more denaturing. Note that chloride is roughly at the center of the series, and thus might be expected to induce little change in proteins and water. Though earlier theories on the Hofmeister series suggested that ions to the left enhanced water structure while those to the right destructured or disordered water, this concept is not fully supported by recent experiments. The Hofmeister effect is impacted by the degree of hydration of ions in water, which cation is involved and specific interactions of ions with solutes. Review articles that discuss the complexities of the Hofmeister effect and consider contemporary experimental and theoretical work are available (Zhang and Cremer, 2010; Paschek and Ludwig, 2011).

The “swelling” water entrained in gels (hydrogels, see Chapter I.2.5) is thought to be in three possible forms. Different nomenclatures are used to describe these forms, but basically three states have been proposed: (1) free water (similar to bulk water); (2) tightly-bound water (more structured and with limited mobility); and (3) intermediate water (with characteristics of both free and bound water) (Jhon and Andrade, 1973; Akaike et al., 1979). Below, when the hydrophobic effect is discussed, other possibilities will be suggested. Evidence for different forms of water in gels continues to accumulate (Sekine and Ikeda-Fukazawa, 2009) and implications for biomaterials and biocompatibility have been discussed (Tsuruta, 2010). The nature of the water in the gel may also impact on the diffusion of molecules through it, blood interactions, and its performance as a cell-support in tissue engineering. The water that swells a hydrogel is impacted by the polymer chains at a nanoscale, because of its close proximity to the polymer that comprises the mesh of the hydrogel. When macroscopic pores are introduced into the hydrogel, the polymer will impact the water in a different fashion, i.e., the surface of the pores will interact with water in a manner similar to surface effects discussed in the next paragraph; in the interior of the pore (away from the pore wall), the water will have an organization more similar to bulk water.

When a solid surface or biomaterial disrupts the continuum structure of water, the water near the solid surface will have to adopt a new organization to achieve energy minimization for the total system. Since all our biomaterials will first see water before proteins or cells ever diffuse or transport to the surface, the nature of this surface water layer may be, from a biomaterials science standpoint, the most important event driving biointeractions at interfaces.

The nature of water in proximity to surfaces may be the primary driver for interactions between biomaterials and biological systems.

There is ample evidence from many analytical techniques, and also from computational methods, that water organization is altered close to a surface compared to the bulk. Most experimental data suggests this difference persists over a length of 1 to 4 water molecules, before reverting to a structure indistinguishable from the bulk water. There is much research on the adsorption of the first layer of water on materials. Clearly, the organization of this first layer will dictate the structure of subsequent layers. On many close packed metal crystal surfaces (for example, Pt, Ni, Pd) results suggest that a water bilayer exists with a structure analogous to ice (Hodgson and Haq, 2009). This may have led to the somewhat misleading term for interfacial water, “ice-like water.” Although the water structure is different from the bulk liquid at all surfaces, the specific ice-like organization is predominantly seen at these close packed metal crystal surfaces. Above the water bilayer directly in contact with the metal, water structure is altered for a few molecular layers until it becomes indistinguishable from bulk water. Other studies demonstrate differences between hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces as to their interactions with water (Howell et al., 2010). Hydrophilic surfaces largely have a substantial effect on water organization, while at hydrophobic interfaces there appears to be a low water density zone, sometimes called a depletion zone, less than a nanometer from the surface. There are hundreds of recent studies on the water–solid interface, mostly in physical chemistry journals. A comprehensive review of this complex and still controversial subject would be impossible in this textbook. However, the take home message is relatively straightforward – the presence of an interface alters the water structure adjacent to it.

Water: Significance for Biomaterials

When a protein or a cell approaches a biomaterial, it interacts with the surface water first. This final section will briefly review some implications of this surface water for biomaterials.

When a protein or a cell approaches a biomaterial, it interacts with the surface water first.

Hydrophobic Effect, Liposomes, and Micelles

If we place a drop of oil under water it will round up to a sphere as it floats to the water surface. The common explanation for this is that because oil molecules do not H-bond with water molecules the oil cannot strongly interact with the bulk water phase. Another way to say this is that the oil disrupts the bulk (continuum) structure of water, and the water molecules at the oil interface then have to restructure to a new (more ordered) organization. This decrease in water entropy is energetically unfavorable according to the second law of thermodynamics. So, the oil minimizes its interfacial area with the water by coalescing into a sphere (a sphere has the lowest surface area for a given volume). This is called the hydrophobic effect (Tanford, 1978; Widom et al., 2003). It is not driven by the oil–water molecular interactions, but rather by the necessity to minimize the more structured (low entropy) organization of water molecules.

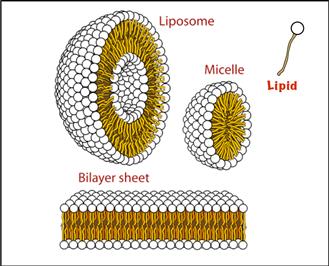

If we now take a surfactant molecule comprised of an “oily” segment and a polar (water-loving) segment, by shielding the oily phase from the water with the hydrophilic head groups, contact between oil and water is minimized. Figure I.1.6.4 illustrates some hydrophobic effect-driven supramolecular aggregate structures that lead to this energy minimization. Liposomes and block copolymer micelles are widely used in drug delivery, where the hydrophobic region (micelle core or liposome bilayer) or the aqueous center (liposome) can carry a hydrophobic drug or hydrophilic drug, respectively (see Chapter II.5.18). Bilayer sheets are used in biosensors to orient and stabilize receptor proteins.

FIGURE I.1.6.4 Lipid molecules with polar head groups (white) and hydrophobic tails (brown), when placed in water, organize themselves to minimize surface area contact between the hydrophobic tail (typically comprised of methylene units, -CH2-) and water. This minimization of contact area, depending on precise conditions, can lead to micelles, liposomes or bilayer sheets.

(Modified from a public domain image on Wikimedia Commons.)

Hydrogels

The structured water within hydrogels has been discussed. Water structure associated with hydrogels has been implicated in their interactions with blood (Garcia et al., 1980; Tanaka and Mochizuki, 2004). Water structure in hydrogels is also thought to be important in the performance of hydrogel contact lenses, specifically the rate of lens dehydration (Maldonado-Codina and Efron, 2005).

Protein Adsorption

Protein adsorption is discussed in detail in Chapter II.1.2, and is critically important for understanding the performance of biomaterials. A question commonly posed is: “Why do proteins bind rapidly and tenaciously to almost all surfaces?” A model that can explain this considers structured water at interfaces. All surfaces will organize water structure differently from the bulk structure; this organization almost always gives more structured (lower entropy) water. If a protein can displace the ordered water in binding to the surface, the entropy of the system will increase as the water molecules are released and gain freedom in bulk water. This is probably the driving force for protein adsorption at most interfaces. There are some specially engineered surfaces referred to as “non-fouling” or “protein-resistant” (see Chapter I.2.10). These surfaces may resist protein adsorption by binding or structuring water so strongly that the protein molecule cannot “melt” or displace the organized or tightly bound water, and thus there is no driving force for adsorption.

Life

Living systems self-assemble from smaller molecular units. For example, think about the organizational processes in going from an egg, to a fetus, to a mature creature. Much of this assembly is driven by hydrophobic interactions (i.e., entropically by water structure). Another area where water structure has a major impact on life involves DNA and its unique binding of water (Khesbak et al., 2011). Also, consider enzymes that are so essential to life. A substrate molecule enters the active site of an enzyme by displacing water molecules. The unique mechanical properties of cartilage under compression can be modeled by considering water organization. In fact, the average human is 57% by weight water, on a molar basis by far the major component in the human body. Thus we can well appreciate, as Henderson surmised in 1913, that water is essential to this phenomenon we call life. As you work through this textbook, think about how the phenomena you are reading about may be driven or controlled by water that comprises such a large fraction of all biological systems.

Bibliography

1. Akaike T, Sakurai Y, Kosuge K, Kuwana K, Katoh A, et al. Study on the interaction between plasma proteins and synthetic polymers by circular dichroism. ACS Polymer Preprints. 1979;20(1):581–584.

2. Garcia C, Anderson JM, Barenberg SA. Hemocompatibility: Effect of structured water. Transactions of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs. 1980;26:294–298.

3. Henderson LJ. The Fitness of the Environment. New York, NY: The Macmillan Company; 1913.

4. Hodgson A, Haq S. Water adsorption and the wetting of metal surfaces. Surface Science Reports. 2009;64(9):381–451.

5. Howell C, Maul R, Wenzel W, Koelsch P. Interactions of hydrophobic and hydrophilic self-assembled monolayers with water as probed by sum-frequency-generation spectroscopy. Chemical Physics Letters. 2010;494(4–6):193–197.

6. Jhon MS, Andrade JD. Water and hydrogels. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1973;7:509–522.

7. Keutsch FN, Saykally RJ. Water clusters: Untangling the mysteries of the liquid, one molecule at a time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(19):10533–10540.

8. Khesbak H, Savchuk O, Tsushima S, Fahmy K. The role of water H-bond imbalances in B-DNA substrate transitions and peptide recognition revealed by time-resolved FTIR spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133(15):5834–5842.

9. Maldonado-Codina C, Efron N. An investigation of the discrete and continuum models of water behavior in hydrogel contact lenses. Eye & Contact Lens: Science & Clinical Practice. 2005;31(6):270–278.

10. Marcus Y. Effect of ions on the structure of water: Structure making and breaking. Chemical Reviews. 2009;109:1346–1370.

11. Paschek D, Ludwig R. Specific ion effects on water structure and dynamics beyond the first hydration shell. Angewandte Chemie (International Edition). 2011;50(2):352–353.

12. Sekine Y, Ikeda-Fukazawa T. Structural changes of water in a hydrogel during dehydration. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2009;130 034501.

13. Smith JD, Cappa CD, Wilson KR, Cohen RC, Geissler PL, et al. Unified description of temperature-dependent hydrogen-bond rearrangements in liquid water. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(40):14171–14174.

14. Tanaka M, Mochizuki A. Effect of water structure on blood compatibility: Thermal analysis of water in poly(meth)acrylate. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 2004;68A:684–695.

15. Tanford C. The hydrophobic effect and the organization of living matter. Science. 1978;200(4345):1012–1018.

16. Tsuruta T. On the role of water molecules in the interface between biological systems and polymers. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2010;21(14):1831–1848.

17. Widom B, Bhimalapuram P, Koga K. The hydrophobic effect. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2003;5(15):3085.

18. Zhang Y, Cremer PS. Chemistry of Hofmeister anions and osmolytes. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2010;61(1):63–83.