Chapter I.2.10

Non-Fouling Surfaces

Introduction

“Non-fouling” surfaces (NFSs) refer to surfaces that resist the adsorption of proteins and/or adhesion of cells. They are also loosely referred to as protein-resistant surfaces and “stealth” surfaces. It is generally acknowledged that surfaces that strongly adsorb proteins will generally bind cells, and that surfaces that resist protein adsorption will also resist cell adhesion. It is also generally recognized that hydrogel surfaces are more likely to resist protein adsorption, and that hydrophobic surfaces will usually adsorb a monolayer of tightly adsorbed protein. Exceptions to these generalizations exist but, overall, they are accurate statements. Further details on protein adsorption can be found in Chapter II.1.2.

Given that proteins have a strong tendency to adsorb to almost all surfaces, how might NFSs work to inhibit such adsorption? Although there are many potential mechanisms for action, most non-fouling surfaces seem to have strong interactions with water. This water–polymer interaction highly hydrates and expands surface hydrophilic polymer chains. Also, the NFSs bind water tightly, and this water shield separates the proteins from the material of the surface. These mechanisms will be elaborated on below.

An important area for NFSs focuses on bacterial biofilms (see Chapter II.2.8). Bacteria are believed to adhere to surfaces via a “conditioning film” of organic molecules that adsorbs first to the surface. The bacteria stick to this conditioning film and begin to exude a gelatinous slime layer (the biofilm) that aids in their protection from external agents (for example, antibiotics). Such layers are particularly troublesome in devices such as urinary catheters and endotracheal tubes. However, they also form on vascular grafts, hip joint prostheses, heart valves, and other long-term implants, where they can stimulate significant inflammatory reaction to the infected device. If the conditioning film can be inhibited, bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation can also be reduced. NFSs offer this possibility.

Non-fouling surfaces are important in medical devices where they may inhibit bacterial colonization and blood cell adhesion. They are also valuable for microfluidic devices, surface-based diagnostic assays, preventing marine organism build-up on ships, and reducing biofilm formation on heat exchangers.

NFSs have medical and biotechnology uses as blood-compatible materials (where they may resist fibrinogen adsorption and platelet attachment), implanted devices (where they reduce the foreign-body reaction; simplify device removal), urinary catheters, biosensors, affinity separation processes, microchannel flow devices, intravenous syringes and tubing, and non-medical uses as biofouling-resistant heat exchangers and ship hulls. It is important to note that many of these applications involve in vivo implants or extra-corporeal devices, and others involve in vitro diagnostic assays, sensors, and affinity separation processes. As well as having considerable medical and economic importance, they offer significant experimental and theoretical insights into an important phenomenon in biomaterials science: protein adsorption. Hence, NFSs have been the subject of many investigations. Aspects of non-fouling surfaces are addressed in many other chapters of this textbook, including the chapters on water at interfaces (Chapter I.1.6), surface modification (Chapter I.2.12), and protein adsorption (Chapter II.1.2).

The significant portion of the literature on non-fouling surfaces focuses on surfaces containing the relatively simple polymer, poly(ethylene glycol) or PEG:

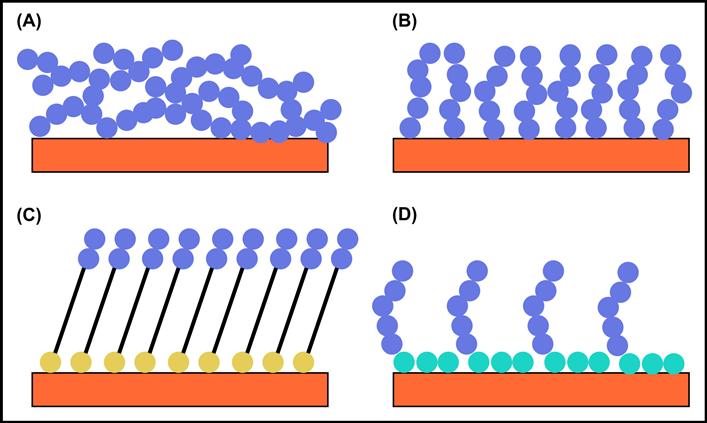

When n is in the range of 15–3500 (molecular weights of approximately 400–100,000), the PEG designation is used. Where molecular weights are greater than 100,000, the molecule is commonly referred to as poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO). Where n is in the range of 2–15, the term oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) is often used. Other natural and synthetic polymers besides PEG show non-fouling behavior, and they will also be discussed in this chapter. Figure I.2.10.1 schematically illustrates types of surfaces that show non-fouling properties.

FIGURE I.2.10.1 Four surfaces that can show non-fouling behavior. The blue dot represents a non-fouling chemical moiety such as (CH2CH2O)n. (A) Cross-linked network of long, polymeric chains; (B) polymer brush grown off the surface; (C) oligo-non-fouling headgroups on a self-assembled monolayer (the yellow dot is the anchor group such as a thiol); (D) surfactant adsorbed to the surface. The hydrophobic tails are represented by turquoise dots.

Background

The published literature on protein and cell interactions with biomaterial surfaces has grown significantly in the past 40 years, and the following concepts have emerged:

• It is well-established that hydrophobic surfaces have a strong tendency to adsorb proteins, often irreversibly (Hoffman, 1986; Horbett and Brash, 1987, 1995). The driving force for this action is most likely the unfolding of the protein on the surface, accompanied by release of many bound water molecules from the solid surface at the interface (see Chapter I.1.6), leading to a large entropy gain for the system (Hoffman, 1999). Note that adsorbed proteins can be displaced (or “exchanged”) from the surface by solution phase proteins (Brash et al., 1974).

• It is also well-known that, at low ionic strengths, cationic proteins bind to anionic surfaces and anionic proteins bind to cationic surfaces (Horbett and Hoffman, 1975; Bohnert et al., 1988; Hoffman, 1999). The major thermodynamic driving force for these actions is a combination of ion–ion coulombic interactions, accompanied by an entropy gain due to the release of counter-ions along with their waters of hydration. However, these interactions are diminished at physiologic conditions by shielding of the protein ionic groups at 0.15 N ionic strength (Horbett and Hoffman, 1975). Still, lysozyme, a highly charged cationic protein at physiologic pH, strongly binds to hydrogel contact lenses containing anionic monomers (see Bohnert et al., 1988, and Chapter II.5.9A).

• It has been a common observation that proteins tend to adsorb in monolayers, i.e., proteins do not adsorb non-specifically onto their own monolayers (Horbett, 1993). This is probably due to retention of hydration water by the adsorbed protein molecules, preventing close interactions of the protein molecules in solution with the adsorbed protein molecules. In fact, adsorbed protein films are, in themselves, reasonable non-fouling surfaces with regard to other proteins (but not necessarily to cells).

• Early studies were carried out on surfaces coated with physically- or chemically-immobilized PEG, and a conclusion was reached that a minimum PEG molecular weight (MW) was needed in order to provide good protein repulsion (Mori et al., 1983; Gombotz et al., 1991; Merrill, 1992). This seemed to be the case whether PEG was chemically bound: (1) as a side-chain of a polymer that was grafted to the surface (Mori et al., 1983); (2) by one end to the surface (Gombotz et al., 1991; Merrill, 1992); or was incorporated (3) as segments in a cross-linked network (Merrill, 1992). The minimum MW to achieve an NFS with these low molecular weight polymeric PEGs was found to be ca. 500–2000, depending on packing density (Mori et al., 1983; Gombotz et al., 1991; Merrill, 1992).

• The mechanism of protein resistance by the polymeric PEG surfaces may be due to a combination of factors, including the resistance of the polymer coil to compression due to its desire to retain the more expanded volume of a random coil (called “entropic repulsion” or “elastic network” resistance) plus the resistance of the PEG molecule to release both bound and free water from within the hydrated coil (called “osmotic repulsion”) (Gombotz et al., 1991; Antonsen and Hoffman, 1992; Heuberger et al., 2005). It is interesting, as noted above, that the non-fouling character of PEG surfaces begins when the MWs of PEG reach around 500–2000. As that size is reached, Gombotz et al. postulated that the chain segments will begin to form random coils, which could retain water more efficiently between the chain segments. The retention of water by shorter chains would not be as efficient as by the higher MW coils, especially at relatively low surface OEG/PEG densities. The size of the adsorbing protein and its resistance to unfolding may also be important factors determining the extent of adsorption on any surface (Lim and Herron, 1992).

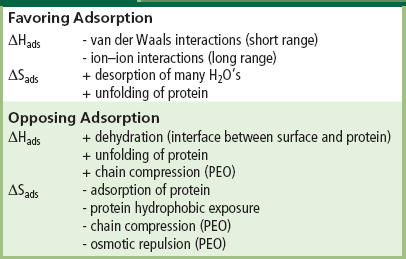

The thermodynamic principles governing the adsorption of proteins onto surfaces involve a number of enthalpic and entropic terms favoring or resisting adsorption. These terms are summarized in Table I.2.10.1. The major factors favoring adsorption will be the entropic gain of released water and the enthalpy loss due to cation–anion attractive interactions between ionic protein groups and surface groups. The major factors favoring resistance to protein adsorption will be the retention of bound water plus, in the case of an immobilized hydrophilic polymer, entropic and osmotic repulsion of the polymer coils.

Although evidence was discussed above for a PEG molecular weight effect, excellent protein resistance can be achieved with very short chain PEGs (OEGs) and PEG-like surfaces (Lopez et al., 1992; Prime and Whitesides, 1993; Sheu et al., 1993). When these surfaces with only short OEG units have sufficiently high (CH2CH2O) unit molar densities, they exhibit excellent non-fouling behavior under conditions of low protein concentration. For example, Prime and Whitesides (1993) have noted that non-fouling behavior begins when around 50–60% of the surface groups in their self-assembled monolayer (SAM) are conjugated with OEGs having six EG units. This may be due to formation of a “contiguous” surface film of bound water that is extensive in area and a nanometer or so thick. Another way to view this phenomenon is that, if the OEG units are spaced isotropically on the surface, the remaining “bare” or exposed surface areas on average are less than the diameter of a typical globular protein. (Note: At higher protein solution concentrations, these oligo surfaces foul with adsorbed protein. This solution concentration effect will be discussed shortly.)

Observations on self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of lipid-oligoEG molecules have been particularly important in the understanding of NFSs (SAMs are described in Chapter I.2.12). SAMs prepared to explore NFSs were formed on gold with a set of molecules based on this alkyl thiol structure: HS(CH2)11(OCH2CH2)nOH. The oligo(ethylene glycol) chain length, n, was 0, 1, 2, 4, 6 or 17. OEGs with larger n (more EG units) were more protein-resistant. The surface concentration of these OEG-thiol units needed to achieve non-fouling behavior decreased with increasing n (Prime and Whitesides, 1993). Note that when n = 17, the OEG chain has a molecular weight over 700. Thus, the excellent non-fouling behavior of this surface can be attributed to both chain entropy arguments, and the ability of EG units to interact with water. Thus, protein resistance by OEG-coated surfaces may be related to a “cooperativity” between the hydrated, short OEG chains in the “plane of the surface,” wherein the OEG chains interact together to bind water to the surface in a manner analogous to the hydrated coil and its osmotic repulsion, as described above. It was observed that a minimum of three EG units are needed for highly effective protein repulsion (Harder et al., 1998), although Prime and Whitesides (1993) demonstrated that good protein resistance could be achieved with n = 2, if the surface density was high enough. Based on all of these observations, one may describe the mechanism as being related to the conformation of the individual oligoEG chains, along with their packing density in the SAM. It has been proposed that helical or amorphous OEG conformations lead to stronger water–OEG interactions than an all-trans OEG conformation (Harder et al., 1998).

TABLE I.2.10.1 Thermodynamics of Protein Adsorption

Packing density of the non-fouling groups on the surface is clearly an important factor in preparing non-fouling surfaces. Nevertheless, one may conclude that the one common factor connecting all NFSs is their resistance to release of bound water molecules from the surface. This argument is supported by neutron reflectivity measurements by Skoda et al. (2009), where they found a depletion of protein concentration around 4–5 nm above an OEG surface that might be attributable to a tightly-bound water layer interfering with the protein approach to the actual surface. Also, direct measurements by D2O exchange and sum frequency generation (SFG, see Chapter I.1.5) of water organization at the interface of non-fouling and fouling SAMs demonstrate that NFSs lead to a more bound, organized water (Stein et al., 2009). Interfacial water may be reorganized both by hydrophobic groups and by hydrophilic (primarily via hydrogen bonds) interactions. In the latter case, the water may be H-bonded to neutral polar groups, such as hydroxyl (-OH) or ether (-C-O-C-) groups, or it may be polarized by ionic groups, such as -COO− or -NH3+. The more profound molecular reorganizations of water seen in NFSs are associated with certain hydrophilic surfaces. The overall conclusion from all of the above observations is that resistance to protein adsorption at biomaterial interfaces is directly related to retention by interfacial groups of their bound waters of hydration.

Resistance to protein adsorption at biomaterial interfaces is directly related to resistance of interfacial groups to the release of their bound waters of hydration.

Based on these conclusions, it is obvious why the most common approaches to reducing protein and cell binding to biomaterial surfaces have been to form surfaces that strongly interact with water. This has been accomplished by a variety of strategies:

• Chemical immobilization of a hydrophilic polymer (e.g., PEG or OEG) on the biomaterial surface using: (1) UV or ionizing radiation to graft copolymerize a hydrophilic monomer onto surface groups; (2) deposition of such a polymer from the vapor of a precursor monomer in a gas discharge process; (3) covalent immobilization of a pre-formed hydrophilic polymer or surfactant to the surface using radiation, gas discharge or wet-chemical coupling processes; or (4) growth of a non-fouling polymer brush off the surface by controlled radical polymerization methods.

Examples of some of these strategies follow.

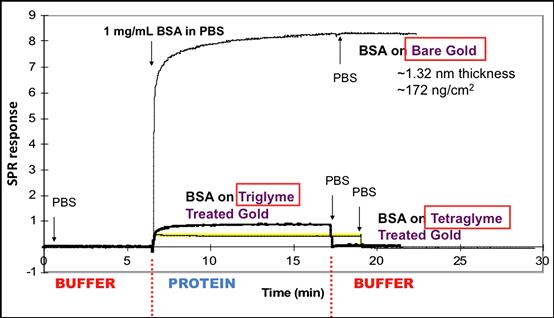

• Gas discharge has been used to covalently bind non-fouling surfactants such as Pluronic® polyols to polymer surfaces (Sheu et al., 1993), and it has also been used to deposit an “oligoEG-like” coating from vapors of triglyme or tetraglyme (Lopez et al., 1992; Mar et al., 1999) (Figure I.2.10.2). Highly fouling-resistant brushes of PEG chains have been grown from surfaces using atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) methods (Ma et al., 2004).

FIGURE I.2.10.2 A surface plasmon resonance (SPR) study of protein adsorption to plasma-deposited triglyme and tetraglyme surfaces. The SPR response (y axis) is proportional to protein concentration. At minute 7, bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution (1 mg/mL) is introduced into the buffer flow over the surfaces being examined. A gold surface adsorbs significant levels of BSA. Both the triglyme and the tetraglyme surfaces show much lower SPR responses. At 17 minutes, the protein flow is switched to a buffer flow. No protein desorbs from the gold. Essentially all the protein on the triglyme and tetraglyme surfaces desorbs, bringing the SPR signal for those surfaces back to baseline. This experiment is described in Mar et al., 1999.

• Chemical derivitization of surface groups with neutral groups, such as hydroxyls, or with negatively-charged groups (especially since most proteins and cells are negatively charged) such as carboxylic acids or their salts, or sulfonates.

• Physical adsorption of surfactants or other surface-active molecules that are coupled to non-fouling moieties. Examples include: adsorption of poly(ethylene gycol-propylene glycol) block copolymers (Lee et al., 1989); surface attachment of biomimetic analogs of muscle adhesive peptides coupled to PEG chains (Dalsin et al., 2003); and immobilization of PEG brushes to metal oxides through interaction with a positively charged polylysine backbone (Kenausis et al., 2000).

• Hydrophilic polymers containing zwitterionic groups along their backbones have been extensively studied for their non-fouling properties. Examples include: poly[2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine] (Ishihara et al., 1998; Iwasaki et al., 1999; Ishihara and Takai, 2009); sulfbetaines (Stein et al., 2009); and carboxybetaines (Zhang et al., 2008).

• Coatings of many hydrogels, including poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) and polyacrylamide, show reasonable non-fouling behavior (Lopez et al., 1993).

A number of naturally-occurring biomolecules such as albumin, casein, hyaluronic acid, and mucin have been coated on surfaces and exhibited resistance to non-specific adsorption of proteins (Vogt et al., 1987; Van Beek et al., 2008). Albumin and non-fat milk solids (mainly containing casein) are often used as “blocking” agents to prevent non-specific protein adsorption in ELISA assays. Naturally-occurring ganglioside lipid surfactants having saccharide head groups have been used to make “stealth” liposomes (Lasic and Needham, 1995). One paper even suggested that the protein resistance of PEGylated surfaces is related to the “partitioning” of albumin into the PEG layers, causing those surfaces to “look like native albumin” (Vert and Domurado, 2000).

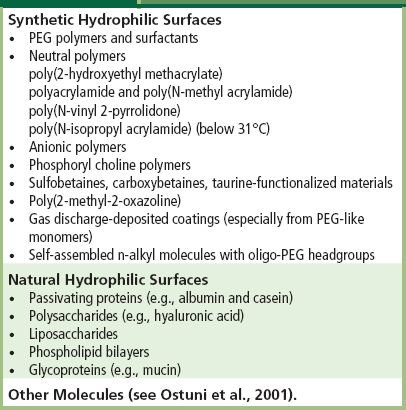

SAMs presenting an interesting series of head group molecules that can act as H-bond acceptors, but not as H-bond donors, have been shown to yield surfaces with unexpected protein resistance (Chapman et al., 2000; Ostuni et al., 2001; Kane et al., 2003). Interestingly, PEG fits in this category of H-bond acceptors but not donors; Merrill first noted this in 1983 (Merrill and Salzman, 1983). However, this generalization does not explain all non-fouling surfaces; consider that mannitol groups with H-bond donor -OH groups were found to be non-fouling (Luk et al., 2000). Also, adsorbed protein films are non-fouling, and these have H-bond donor and acceptor groups. Another hypothesis proposes that the functional groups that impart a non-fouling property are kosmotropes, order-inducing molecules (Kane et al., 2003). Perhaps because of the ordered water surrounding these molecules, they cannot penetrate the ordered water shell surrounding proteins, therefore strong intermolecular interactions between surface group and protein cannot occur. An interesting kosmotrope molecule with good non-fouling ability described in this paper is taurine H3N+(CH2)2SO3. Table I.2.10.2 summarizes some of the different compositions that have been applied as non-fouling surfaces.

TABLE I.2.10.2 “Non-Fouling” Surface Compositions

It is worthwhile mentioning computational papers (supported by some experiments) that offer new insights and ideas on NFSs (Lim and Herron, 1992; Pertsin and Grunze, 2000; Pertsin et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2011). Also, many new experimental methods have been applied to study the mechanism of non-fouling surfaces, including neutron reflectivity to measure the water density in the interfacial region (Schwendel et al., 2003; Skoda et al., 2009), scanning force microscopy (Feldman et al., 1999; Heuberger et al., 2005), and sum frequency generation (Zolk et al., 2000; Stein et al., 2009).

The significance of protein solution concentration for surface protein resistance requires further discussion. In relatively dilute protein solutions, such as are used in diagnostic assays and sometimes in cell culture, all of the surfaces described so far will demonstrate non-fouling behavior. However, at protein concentrations similar to that in the bloodstream or in body fluids, many of these surfaces no longer appear non-fouling. The surfaces that exhibit non-fouling behavior at higher protein concentration are comprised of longer hydrophilic chains with high conformational freedom (Ma et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2008). Surfaces comprised of short oligo units of non-fouling chemistries (Figure I.2.10.1C or the glyme surfaces described in Figure I.2.10.2) probably function by tightly binding water. It may be that at high solution protein content, the protein molecules compete for the bound surface water, and the non-fouling effect vanishes. On the other hand, when longer, flexible chains are present, the entropic repulsion effect described earlier permits these surfaces to remain free of adsorbed protein, as long as the hydrophilic polymer surface density is high enough.

Finally, it should be noted that bacteria tend to adhere and colonize almost any type of surface, perhaps even many protein-resistant NFSs. However, the best NFSs can provide acute resistance to bacteria and biofilm build-up better than most surfaces (Johnston et al., 1997). Resistance to bacterial adhesion remains an unsolved problem in surface science. Also, it has been pointed out that susceptibility of PEGs to oxidative damage may reduce their utility as non-fouling surfaces in real-world situations (Kane et al., 2003).

Conclusions and Perspectives

It is remarkable how many different surface compositions appear to be non-fouling (although the majority of surfaces used in medicine and biology adsorb protein). Although the unifying mechanisms are not fully clarified, it appears that the major factor favoring resistance to protein adsorption will be the retention of bound water by the surface molecules, plus, in the case of an immobilized hydrophilic polymer, entropic and osmotic repulsion of the polymer coils. Little is known about how long a non-fouling surface will remain non-fouling in vivo. Longevity and stability for non-fouling biomaterials remains an uncharted frontier. Defects (e.g., pits, uncoated areas) in NFSs may provide “footholds” for bacteria and cells to begin colonization. Enhanced understanding of how to optimize the surface density and composition of NFSs will lead to improvements in quality and fewer micro-defects. Finally, it is important to note that a clean, “non-fouled” surface may not always be desirable. In the case of cardiovascular implants or devices, emboli may be shed when such a surface is exposed to flowing blood (Hoffman et al., 1982). This can lead to undesirable consequences, even though (or perhaps especially because) the surface is an effective, non-fouling surface. In the case of contact lenses, a protein-free lens may seem desirable, but there are concerns that such a lens will not be comfortable (mucin adsorption, for example, may contribute to comfort). Although biomaterials scientists can presently create surfaces that are non-fouling for a period of time, applying such surfaces must take into account the specific application, the biological environment, and the intended service life.

Bibliography

1. Antonsen KP, Hoffman AS. Water Structure of PEG Solutions by DSC Measurements. In: Harris JM, ed. Polyethylene Glycol Chemistry: Biotechnical and Biomedical Applications. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992:15–28.

2. Brash JL, Uniyal S, Samak Q. Exchange of albumin adsorbed on polymer surfaces. Trans Am Soc Artif Int Org. 1974;20:69–76.

3. Bohnert JL, Horbett TA, Ratner BD, Royce FH. Adsorption of proteins from artificial tear solutions to contact lens materials. Invest Ophth Vis Sci. 1988;29(3):362–373.

4. Chapman RG, Ostuni E, Takayama S, Holmlin RE, Yan L, et al. Surveying for surfaces that resist the adsorption of proteins. JACS. 2000;122:8303–8304.

5. Dalsin JL, Hu B-H, Lee BP, Messersmith PB. Mussel adhesive protein mimetic polymers for the preparation of nonfouling surfaces. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(14):4253–4258.

6. Feldman K, Hahner G, Spencer ND, Harder P, Grunze M. Probing resistance to protein adsorption of oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated self-assembled monolayers by scanning force microscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(43):10134–10141.

7. Gombotz WR, Wang GH, Horbett TA, Hoffman AS. Protein adsorption to PEO surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1991;25:1547–1562.

8. Harder P, Grunze M, Dahint R, Whitesides G, Laibinis P. Molecular conformation in oligo (ethylene glycol)-terminated self-assembled monolayers on gold and silver surfaces determines their ability to resist protein adsorption. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:426–436.

9. Heuberger M, Drobek T, Spencer ND. Interaction forces and morphology of a protein-resistant poly(ethylene glycol) layer. Biophys J. 2005;88(1):495–504.

10. Hoffman AS. A general classification scheme for hydrophilic and hydrophobic biomaterial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1986;20 ix–xi.

11. Hoffman AS. Non-fouling surface technologies. J Biomater Sci., Polymer Ed. 1999;10:1011–1014.

12. Hoffman AS, Horbett TA, Ratner BD, Hanson SR, Harker LA, et al. Thrombotic events on grafted polyacrylamide-Silastic surfaces as studied in a baboon. ACS Adv Chem Ser. 1982;199:59–80.

13. Horbett TA. Principles underlying the role of adsorbed plasma proteins in blood interactions with foreign materials. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1993;2:137S–148S.

14. Horbett TA, Brash JL. Proteins at Interfaces: Current Issues and Future Prospects. In: Horbett TA, Brash JL, eds. Proteins at Interfaces, Physicochemical and Biochemical Studies. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1987;1–33. ACS Symposium Series Vol. 343.

15. Horbett TA, Brash JL. Proteins at Interfaces: An Overview. In: Horbett TA, Brash JL, eds. Proteins at Interfaces II: Fundamentals and Applications. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society; 1995;1–25. ACS Symposium Series Vol. 602.

16. Horbett TA, Hoffman AS. Bovine Plasma Protein Adsorption to Radiation Grafted Hydrogels Based Hydroxyethylmethacrylate and N-Vinyl-Pyrrolidone. In: Baier R, ed. Advances in Chemistry Series, 145, Applied Chemistry at Protein Interfaces. Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 1975;230–254.

17. Ishihara K, Takai M. Bioinspired interface for nanobiodevices based on phospholipid polymer chemistry. J Roy Soc Interface. 2009;6(Suppl. 3):S279–S291.

18. Ishihara K, Nomura H, Mihara T, Kurita K, Iwasaki Y, et al. Why do phospholipid polymers reduce protein adsorption?. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39:323–330.

19. Iwasaki Y, Nakabayashi N, Nakatani M, Mihara T, Kurita K, et al. Competitive adsorption between phospholipid and plasma protein on a phospholipid polymer surface. J Biomater Sci Polym Edn. 1999;10:513–529.

20. Johnston EE, Ratner BD, Bryers JD. RF Plasma Deposited PEO-Like Films: Surface Characterization and Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Accumulation. In: d’Agostino R, Favia P, Fracassi F, eds. Plasma Processing of Polymers. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1997;465–476.

21. Kane RS, Deschatelets P, Whitesides GM. Kosmotropes form the basis of protein-resistant surfaces. Langmuir. 2003;19:2388–2391.

22. Kenausis GL, Vörös J, Elbert DL, Huang N, Hofer R, et al. Poly (L-lysine)-g-poly (ethylene glycol) layers on metal oxide surfaces: Attachment mechanism and effects of polymer architecture on resistance to protein adsorption. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104(14):3298–3309.

23. Lasic DD, Needham D. The “stealth” liposome: A prototypical biomaterial. Chem Rev. 1995;95(8):2601–2628.

24. Lee JH, Kopecek J, Andrade JD. Protein-resistant surfaces prepared by PEO-containing block copolymer surfactants. J Biomed Mater Res. 1989;23:351–368.

25. Lim K, Herron JN. Molecular Simulation of Protein-PEG Interaction. In: Harris JM, ed. Polyethylene Glycol Chemistry: Biotechnical and Biomedical Applications. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992;29.

26. Lopez GP, Ratner BD, Tidwell CD, Haycox CL, Rapoza RJ, et al. Glow discharge plasma deposition of tetraethylene glycol dimethylether for fouling-resistant biomaterial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1992;26:415–439.

27. Lopez GP, Ratner BD, Rapoza RJ, Horbett TA. Plasma deposition of ultrathin films of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate): Surface analysis and protein adsorption measurements. Macromolecules. 1993;26:3247–3253.

28. Luk YY, Kato M, Mrksich M. Self-assembled monolayers of alkanethiolates presenting mannitol groups are inert to protein adsorption and cell attachment. Langmuir. 2000;16:9605.

29. Ma H, Hyun J, Stiller P, Chilkoti A. “Non-fouling” oligo(ethylene glycol)- functionalized polymer brushes synthesized by surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization. Adv Mater. 2004;16(4):338–341.

30. Mar MN, Ratner BD, Yee SS. An intrinsically protein-resistant surface plasmon resonance biosensor based upon a RF-plasma-deposited thin film. Sensor Actuator B. 1999;54:125–131.

31. Merrill EW. Poly(ethylene oxide) and Blood Contact: A Chronicle of One Laboratory. In: Harris JM, ed. Polyethylene Glycol Chemistry: Biotechnical and Biomedical Applications. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992;199–220.

32. Merrill EW, Salzman EW. Polyethylene oxide as a biomaterial. ASAIO Journal. 1983;6:60.

33. Mori Y, et al. Interactions between hydrogels containing peo chains and platelets. Biomaterials. 1983;4:825–830.

34. Ostuni E, Chapman RG, Holmlin RE, Takayama S, Whitesides GM. A survey of structure–property relationships of surfaces that resist the adsorption of protein. Langmuir. 2001;17:5605–5620.

35. Pertsin AJ, Grunze M. Computer simulation of water near the surface of oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir. 2000;16(23):8829–8841.

36. Pertsin AJ, Hayashi T, Grunze M. Grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations of the hydration interaction between oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106(47):12274–12281.

37. Prime KL, Whitesides GM. Adsorption of proteins onto surfaces containing end-attached oligo(ethylene oxide): A model system using self-assembled monolayers. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10714–10721.

38. Schwendel D, Hayashi T, Dahint R, Pertsin A, Grunze M, et al. Interaction of water with self-assembled monolayers: Neutron reflectivity measurements of the water density in the interface region. Langmuir. 2003;19(6):2284–2293.

39. Sheu M-S, Hoffman AS, Terlingen JGA, Feijen J. A new gas discharge process for preparation of non-fouling surfaces on biomaterials. Clin Mater. 1993;13:41–45.

40. Skoda M, Schreiber F, Jacobs R, Webster J, Wolff M, et al. Protein density profile at the interface of water with oligo (ethylene glycol) self-assembled monolayers. Langmuir. 2009;25(7):4056–4064.

41. Stein M, Weidner T, McCrea K, Castner D, Ratner BD. Hydration of sulphobetaine and tetra(ethylene glycol)-terminated self-assembled monolayers studied by sum frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113(33):11550–11556.

42. Van Beek M, Jones L, Sheardown H. Hyaluronic acid containing hydrogels for the reduction of protein adsorption. Biomaterials. 2008;29(7):780–789.

43. Vert M, Domurado D. PEG: Protein-repulsive or albumin-compatible?. J Biomater Sci Pol Ed. 2000;11:1307–1317.

44. Vogt Jr RV, Phillips DL, Omar Henderson L, Whitfield W, Spierto FW. Quantitative differences among various proteins as blocking agents for ELISA microtiter plates. J Immunol Methods. 1987;101(1):43–50.

45. Xu X, Cao D, Wu J. Density functional theory for predicting polymeric forces against surface fouling. Soft Matter. 2011;6(19):4631–4646.

46. Zhang Z, Zhang M, Chen S, Horbett TA, Ratner BD, et al. Blood compatibility of surfaces with superlow protein adsorption. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4285–4291.

47. Zolk M, Eisert F, Pipper J, Herrwerth S, Eck W, et al. Solvation of oligo(ethylene glycol)-terminated self-assembled monolayers studied by vibrational sum frequency spectroscopy. Langmuir. 2000;16(14):5849–5852.