Chapter III.1.4

Device Failure Mode Analysis

The design of implants, the biomaterials selected for them, their fabrication, and the protocols used to test them before use in humans, are all intended to minimize the possibility of device failure. Indeed, the majority of such devices serve their patients well, alleviating pain and disability, enhancing quality of life, and/or increasing survival. Nevertheless, some medical devices fail, often following extended intervals of satisfactory function. Problems involving medical device technology are often called “medical device error” (Goodman, 2002). Unraveling a cause of failure in an individual case usually requires systematic integration of clinical and laboratory information pertaining to the patient, and careful and protocol-driven pathological analyses. Analysis of a cohort of failed devices, often called “failure mode analysis”, involves many such cases and sometimes additional investigation, such as review of corporate quality assurance and/or other documents. Irrespective of implant site or desired function of the device, the overwhelming majority of clinical complications produced by medical devices fall into several well-defined categories, which are summarized in Table III.1.4.1.

Unraveling a cause of failure in an individual case usually requires systematic integration of clinical and laboratory information pertaining to the patient, and careful and protocol-driven pathological analyses. Analysis of a cohort of failed devices, often called “failure mode analysis”, involves many such cases and sometimes additional investigation, such as review of corporate quality assurance and/or other documents.

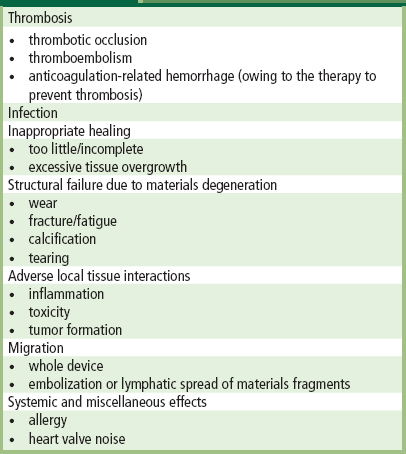

TABLE III.1.4.1 Patient–Device Interactions Causing Clinical Complications of Medical Devices

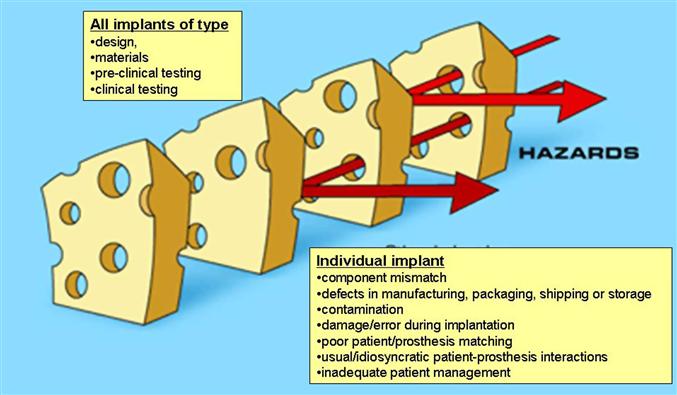

Medical device failures have some features in common with medical errors in general, in that they result from an alignment of “windows of opportunity” in a system’s defenses (Carthey et al., 2001). In general, demographic, structural, functional or physiologic factors relating to the patient (e.g., age, anatomy of the implant site, activity level, genetic predisposition to complications to thrombosis, allergies) and the implantation procedure (e.g., implant selection, technical aspects of the surgery, potential damage to the implant), are superimposed on the biomaterials and device design, which collectively induce vulnerabilities to particular failure modes (Figure III.1.4.1). Thus, we will see that failure of a device in the clinical setting often involves multiple contributing factors. For example, a material or design inadequacy that could potentially cause excessive wear or fracture in an orthopedic prosthesis (hip or knee joint) may only come to light in a young, athletic patient. Moreover, a tendency toward thrombosis of a new design of prosthetic heart valve may only cause a problem in a patient whose anticoagulation effectiveness drops below a critical point, who has a genetic hypercoagulability disorder or who has local blood stasis owing to atrial fibrillation. The determination of the cause(s) and contributory mechanism(s) of implant or other device failure is accomplished by a process called implant retrieval and evaluation (see Chapter II.1.5).

In general, demographic, structural, functional or physiologic factors relating to the patient (e.g., age, anatomy of the implant site, activity level, genetic predisposition to complications to thrombosis, allergies) and the implantation procedure (e.g., implant selection, technical aspects of the surgery, potential damage to the implant), are superimposed on the biomaterials and device design, which collectively induce vulnerabilities to particular failure modes.

FIGURE III.1.4.1 Analysis of implant failure using systems approach to understanding multiple factors (including latent factors, i.e., those relating to any implant of a particular type, and active factors, i.e., conditions affecting a particular implant), useful in critical incident and near-miss reporting in other high technology industries. When potential risks “line up” a failure can occur.

(Concepts modified from Carthey, J., de Leval, M. R. & Reason, J. T. (2001). The human factor in cardiac surgery: Errors and near misses in a high technology medical domain. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 72, 300–305. Reproduced by permission from The Society for Thoracic Surgeons)

The fundamental objective of incident investigation is to identify the root cause of an incident, and eliminate or decrease the risk (based on the probability and severity) of recurrence (Baretich, 2007). The results of implant failure analysis have several potential implications for quality care in individual patients or cohorts of prior and potential recipients, and thus the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Medical Device Reporting regulations require investigation and reporting of certain device-related incidents (Shepherd, 1996). Analysis of an isolated failed implant or of multiple implants that have suffered a consistent failure mode can provide important information for individual patient care. For example, such information can:

• Impact on implant selection and patient–prosthesis matching.

• Mandate altered management of a specific patient, such as a change in the type or dose of drug therapy, such as anticoagulation, and/or closer monitoring of the patient with the at-risk type of prosthesis by echocardiography for a heart valve or X-ray or bone scan to monitor a hip joint.

• Reveal a vulnerability of a sub-group of patients (often called a cohort) with a specific prosthesis type to a particular mode or mechanism of device failure. This can both lead to closer scrutiny of that group of patients with such a device already implanted, and/or stimulate the need for a prospective change in design, materials selection, processing or fabrication, or potential action by regulatory agencies such as further testing or withdrawal from use.

The results of failure analysis can also influence product liability litigation, either in an individual case or in a class action proceeding involving multiple patients who have received a device with a specific real or potential failure mode.

The purpose of this chapter is to define a conceptual approach to the determination of the factors responsible for a device or implant failure. The aim is to provide a basis for using failures to guide patient management and enhance high-quality design, biomaterials development, selection, and implantation of implants.

Analysis often reveals considerations which relate to the development, testing or manufacturing processes, and thereby potentially affect all devices in a cohort, or conditions germane primarily to a particular failed device and the patient who received it.

Questions to be addressed in a specific case might be:

• Was the device chosen the correct type and size for the patient?

• Was it optimally implanted or was there a technical error in placement?

• Was the implant damaged during fabrication or implantation by the surgeon or interventionalist?

• Did the patient have an idiosyncratic pathophysiologic response to the implant, such as allergy or an inherited heightened tendency toward blood clotting on the component biomaterials?

• Was there a design flaw in this prosthetic device type or a poor choice of materials in using an appropriate design?

• Did failure arise because the pre-clinical testing phases of the device did not (or were unable to) reveal some defect of design or materials which only became apparent following use of the device in a large number of patients or for longer duration following large-scale clinical utilization?

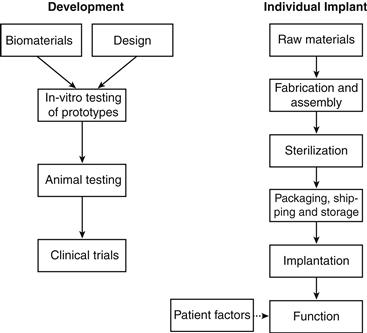

The array of potential causes is summarized in Table III.1.4.2 and conceptualized in Figure III.1.4.2. This chapter is not meant to describe the detailed mechanisms of either deterioration or biological responses of materials, although they may be contributory to complications (which are covered in Sections II.2 and II.4 of this book).

TABLE III.1.4.2 Potential Contributory Causes of Implant or Device Failure

Inadequate materials properties

Inadequate materials testing

Design flaw

Inadequate pre-clinical animal test models

Components missized/mismatched during fabrication

Defects introduced during manufacturing, packaging, shipping, and storage

Damage or contamination during sterilization

Damage or contamination during implantation

Technical error during implantation

Poor patient–prosthesis matching

Unavoidable, physiologic patient–prosthesis interactions

Inadequate patient management

Unusual/abnormal patient response

FIGURE III.1.4.2 Potential causes of implant or device failure.

Multiple recent instances of medical device cohort failures have occurred in the last decade; particularly notable are the metal-on-metal hip replacements implicated for excessive wear (Browne et al., 2010), late thrombosis in drug-eluting endovascular stents (Holmes et al., 2010), and some implantable cardioverter-defibrillators with defective leads, making them unable to provide life-saving heart rhythm corrections (Becker, 2005; Maron and Hauser, 2007).

Role of Biomaterials–Tissue Interactions: Effect of Materials on the Patient and the Effect of the Patient on the Materials

Biomaterials Selection

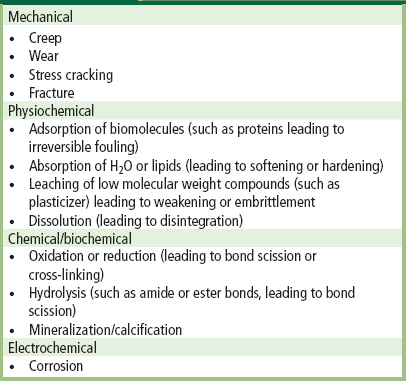

Mechanical failure of biomaterials and adverse biomaterials–tissue interactions are often implicated as the key factors in a device failure. The wide range of different material “breakdown” mechanisms which can cause an implant or device to fail is summarized in Table III.1.4.3. A device or implant can fail simply because the component biomaterials did not have, and/or were not tested for, the requisite physical, chemical or biological properties for the intended application. For example, the poor resistance of Teflon® (polytetrafluoroethylene) to abrasive wear, and its unsuitability for use in both hip joint prostheses (Charnley et al., 1969) and artificial heart valves (Silver and Wilson, 1977) was appreciated only following extensive clinical use. Similarly, the inadequate durability of a carbon-reinforced Teflon® in temporomandibular joint replacement was encountered in clinical usage (Trumpy et al., 1996). In addition, the earliest silicone ball poppets in the Starr–Edwards caged-ball heart valves frequently absorbed lipids from blood during function, and consequently swelled and became brittle, and sometimes fractured (Chin et al., 1971). “Ball variance,” as this complication was known, caused valve dysfunction and/or downstream embolization of fragments. This problem stimulated development of an improved processing protocol for curing medical silicone elastomers that enhanced their mechanical properties, mitigated the lipid absorption, and thereby effectively eliminated ball variance. Conversely, a material used to form the femoral stem of a hip joint prosthesis which is too stiff can cause “stress-shielding,” leading to structurally poor surrounding bone remodeling and consequent loosening of the prosthesis (Huiskes, 1998).

TABLE III.1.4.3 Some Mechanisms of Biomaterial “Breakdown”

Design

Device design is critical to performance. Design of the femoral stems of hip joint prostheses has evolved from clinical experience with fractured stems in human implants to computer-aided design and manufacturing techniques. The design of a heart valve affects the pattern of blood flow and associated platelet damage, and/or the presence of regions of blood stasis, both of which can lead to thrombosis (Yoganathan et al., 1978; Yoganathan et al., 1981).

Device design is critical to performance. Design of the femoral stems of hip joint prostheses has evolved from clinical experience with fractured stems in human implants to computer-aided design and manufacturing techniques. The design of a heart valve affects the pattern of blood flow and associated platelet damage, and/or presence of regions of blood stasis, both of which can lead to thrombosis.

However, redesigning a medical device to eliminate one complication can have unintended, potentially serious consequences. When a widely used tilting disk heart valve was redesigned to allow more complete opening, and thereby enhance its hemodynamic function as well as reduce the incidence of thrombosis, a large number of mechanical failures occurred (Walker et al., 1995). Nearly all failures had similar characteristics; they resulted from fracture of the welds anchoring the metallic struts (which confine and guide the motion of the disk) to the housing, with consequent separation of the strut and escape of the disk. Pathology studies revealed that the underlying problem was metal fatigue resulting from design-related high-velocity over-rotation of the disk during closure, excessively stressing the welds, potentially coupled with intrinsic flaws in the welded regions (Schoen et al., 1992). Interestingly, many such failures occurred in young patients during exercise, when cardiac forces and thereby valve closing velocities, are enhanced (Blot, 2005). Another example was a specific design of a bileaflet tilting disk heart valve which developed fractures that were initiated in various locations along the contacts of the disks with the housing (Baumgartner et al., 1997). In this case, the likely cause was a design flaw which led to the formation of cavitation bubbles during function as the disk moved away from the housing during the earliest phases of valve opening. The hypothesis was that implosion of these bubbles initiated microscopic cracks in the pyrolytic carbon components which then precipitated gross fractures.

Testing of Biomaterials–Design Configurations

In some cases, the pre-clinical in vitro or in vivo evaluation studies that were carried out on the material itself, or on the design and device prototype, either did not adequately simulate the range and/or nature of conditions which are encountered in actual clinical use or were “under powered” (did not have enough replicates) to reveal relatively low-frequency complications, especially where those complications are potentiated by infrequent patient-related factors. For example, some patients have genetic conditions that predispose to hypercoagulability; such individuals would be particularly vulnerable to clotting in cardiovascular devices (Valji and Linenberger, 2009). Individuals taking high therapeutic doses of (cortico) steroid medications for inflammatory/autoimmune disease may not heal implants properly. The inability to reveal certain complications in pre-clinical studies may be a result of the necessarily limited numbers of animals used, or differences in animal versus human anatomy or physiology. In the case of a new bileaflet tilting disk heart valve design which suffered clinical failures due to thrombosis initiated at the points where the hemidisks contacted and pivoted in the housing, the testing of implants in sheep failed to reveal a tendency toward thrombosis (Gross et al., 1996). Furthermore, appropriate tests are not available for some physiologic responses, especially but not exclusively where those problems potentially arise from immunological interactions of xenograft (animal) or allograft (from another person) tissues with humans. For example, the potential for a significant immunological response, such as has been suggested but not proven in some patients with silicone gel breast implants, and is always a possibility in tissue-based biomaterials, is difficult to evaluate adequately in pre-clinical studies. It is also possible that available tests were overlooked because the specific problem types that occurred later were not anticipated.

A particularly illustrative example points out not only the need for improved and comprehensive pre-clinical testing regimes, but also that a change in biomaterial implemented to alleviate one complication may precipitate another problem if corresponding design changes are not considered. Specifically, bioprosthetic heart valves were fabricated from photooxidized bovine pericardium to mitigate the well-known potentiating effect of glutaraldehyde on calcification. However, many of these valves failed by abrasion-induced tearing of the pericardial tissue against the cloth which covered a portion of the stent (Schoen, 1998). The issue in this case was that photooxidized pericardium has a higher compliance than the glutaraldehyde-preserved pericardium used, but the design was unchanged from that of a valve which had been clinically successful. Higher tissue compliance led to greater excursion of the cuspal material during valve closing; the greater tissue movement of the more compliant material caused the tissue to contact and thereby abrade against the cloth. However, this was not revealed during extensive pre-implantation in vitro bench fatigue testing, most likely owing to the markedly accelerated rate of in vitro durability testing which limits tissue movements used owing to a high rate of cycling (generally approximately 20 times or more actual). Moreover, animal testing done in sheep was not (and is typically not) extended more than approximately five months, except in a few specimens which in this case did not exhibit gross failure.

Biological Testing of Implants

After prototype devices have been designed and fabricated, biologic tests in vitro and in animals are normally used to gain more information for eventual regulatory approval and introduction of such a device into the clinic. However, as with the in vitro tests on the materials or designs, in vivo tests on the final device or implant could be poorly chosen, key tests could be overlooked, and/or the animal model selected or permitted may not be the most appropriate one available. For example, there have been continuing arguments over the past several decades among biomaterials scientists as to whether the dog is an appropriate animal model for evaluating blood–surface interactions, especially since dog platelets are considered to be much more adherent to foreign surfaces than human platelets. Furthermore, there is no adequate animal model to study the intense inflammatory reaction to wear debris and other particulates which can accumulate adjacent to a hip joint (Holt et al., 2007). Another case in point highlights a problem that arose owing to differences in healing in some animal models versus humans with a caged-ball mechanical prosthetic heart valve type which had a ball fabricated from silicone and cloth-covered cage struts (Schoen et al., 1984). This design was intended to encourage anchoring and organization of thrombus in the fabric, and thereby decrease thromboembolism. Pre-clinical studies of this valve concept utilized mitral valve implants in pigs, sheep, and calves; in such models the cloth-covered struts were rapidly healed by endothelium-coated fibrous tissue (Bull et al., 1969). However, subsequent clinical implantation of these valves was complicated by cloth wear and embolization before healing occurred. This vivid “case history” illustrates and reinforces the concept that human implantation may reveal important problems not predicted by pre-clinical animal testing. The more vigorous healing that occurred in the preclinical implants in this case is typical in animals compared to humans; this sometimes makes prediction of such problems very difficult. This reinforces the need for closely monitored clinical (human) trials during the introduction of a new implant type, and continued post-market surveillance following widespread general availability and implantation thereafter (Blackstone, 2005).

Animal models also must be used thoughtfully in the study of calcification of tissue valves (Schoen and Levy, 1999), another problem that results from an adverse biomaterial–tissue interaction (see Chapter II.4.5). Two animal models are generally used: (1) subcutaneous implants of valve materials in weanling (approximately three-week-old) rats, which achieve clinical levels of calcification in eight weeks or less; and (2) mitral valve replacements in juvenile sheep, which calcify extensively in 3–5 months. However, when older animals are used (in either model), calcification is vastly diminished. Use of inadequately severe models could lead to overestimation of the efficacy of an anticalcification strategy. This raises a more generic problem: that demonstration of the absence or prevention of specific pathologic features by a therapeutic option in a study requires proper controls to ensure that the model used is capable of provoking the pathology being investigated.

Raw Materials, Fabrication, and Sterilization

In unusual circumstances, a batch of raw material may become defective or damaged. The fabrication process used to manufacture a device can introduce defects or contaminants which can lead to failure of a device, even though the biomaterials and design are well-matched and appropriate for the application and otherwise intact at the start of device assembly. The fracture in the weld of the tilting disk heart valve mentioned above illustrates well the introduction of defects and vulnerabilities during the fabrication process that can contribute to failure.

Incomplete sterilization of the implant (potentiating infection) or damage to the material by the sterilization process also can occur. Indeed, the use of certain materials places serious limitations on sterilization conditions. For example, PMMA intraocular lenses cannot be heat sterilized because the shape (and thereby optics) of the rigid poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) lens would change above the glass transition temperature of the PMMA (100°C). Sterilization by ethylene oxide (EO) gas cannot be used with some biomaterials, because of EO solubility within and/or reactivity with the biomaterial.

These limitations are sometimes so severe that a sterilization protocol is used which is inadequate to sterilize the device. Incomplete sterilization, of course, can lead to infection, as exemplified by cohorts of porcine aortic valve or bovine pericardial bioprostheses contaminated with Myobacterium chelonei, an organism related to that causing human tuberculosis (Rumisek et al., 1985; Strabelli et al., 2010). The problem is that the antibacterial and antifungal efficacy of low concentrations of glutaraldehyde may be poor. The use of combined sterilization agents (e.g., alcoholic glutaraldehyde solutions) has been used to solve this problem without damaging the valve tissue.

Packaging, Shipping, and Storage

Contamination or degradation can occur not only during fabrication and sterilization of devices, but also can be introduced during packaging and shipping. In all medical devices and implants, inadequate packaging or improper storage can contribute to limited shelf life. Transdermal drug delivery patches have to be carefully protected so that the drug does not leak out of the device. Tissue-derived heart valves and other devices may be degraded by excessive heat or freezing, and so are packaged with temperature indicators. Packaging and storage are also critical issues for condoms, made from natural rubber, which is sensitive to oxidation, a process that can degrade the rubber chains during storage on the shelf. Moreover, any drug delivery implant or device (e.g., skin patch, stent, degradable microparticles) could become saturated with the drug while the device is stored, and deliver a burst of drug until the steady-state concentration gradient is reached after contact with the body.

Clinical Handling and Surgical Procedure

Given an implant made of appropriate materials, properly designed, fabricated, sterilized, tested, manufactured, packaged, shipped, and stored, the “moment of truth” occurs at the instant when the package is opened, and the device is handled and implanted or contacted extracorporeally with the patient’s “biosystem.” Key issues here relate to the technical aspects of the surgery and the skill of the surgeon, the possibility of infection due to pre-implantation contamination or mechanical damage caused by improper handling by surgical personnel and/or their instruments. An example is the kinking of a tubular vascular graft, during implantation, thereby impeding its flow and potentially inducing thrombosis.

The Recipient

Although patients are generally well-matched to their prostheses, factors related to the particular recipient, but infrequent in the population at large, may cause or contribute to some failures. For example, since young patients exhibit accelerated calcification of tissue heart valves, such devices are generally avoided in children and adolescents, in whom calcification is accelerated (see Chapter II.4.5). Moreover, appropriateness of prosthesis selection (type or size) can play a role. For example, it would not be appropriate to use a mechanical valve (which requires anticoagulation therapy) in a patient with a known bleeding problem, such as a stomach ulcer. Moreover, some patients are allergic (i.e., exhibit hypersensitivity) to nickel or other metallic elements, and patients with implants containing nickel have had hypersensitive reactions that necessitated reoperation with removal. Thus, a prosthesis containing nickel should not be implanted in a patient with a known allergy to nickel. In addition, a prosthesis inappropriately sized can be deleterious, such as a heart valve with an insufficiently sized orifice (Rahimtoola, 1998). Finally, a patient can abuse or misuse an implant, or can exhibit an unexpected “abnormal” physiologic response. For example, a hip implant recipient who over-exercises before adequate healing has occurred could cause implant loosening.

Abnormal responses may be related to normal or disease-altered physiology. All individuals with implants are vulnerable to infection (see Chapter II.2.8), and they often receive prophylactic antibiotics when undergoing procedures that may introduce bacteria into the bloodstream. However, individuals with cancer or who have received organ transplants, who are often immunosuppressed, are particularly vulnerable to infection at any tumor, transplant or implant site; they may be at even higher risk to develop implant-related infections. Moreover, “abnormal” or “skewed” pathophysiologic responses may also occur in any large population of patients. For example, some patients have genetic or acquired abnormalities of coagulation which render them particularly vulnerable to thrombosis. They are at heightened thrombotic risk for cardiovascular implant or device therapies (De Stefano et al., 1996; Girling and de Swiet, 1997). This general issue of patient heterogeneity in biologic processes may become even more critical in the future with cell-based and other tissue engineered medical devices, in which biological processes play a critical role in both efficacy and safety (Mendelson, 2006).

Failure can also be related to use, independent of patient factors. Implanted interposition grafts (called fistulas) linking artery to vein in the arm are often used for the access to the vasculature required by hemodialysis. Use requires frequent puncture by needles. Repetitive puncture can lead to graft fragmentation, local hemorrhage or aneurysm formation (Georgiadis et al., 2008).

Conclusions

In this chapter, we have described the wide range and diversity of factors that can contribute to the failure of a medical device or implant, and an approach to thinking about them in a particular case. It is important to emphasize that inadequate properties or behavior of the biomaterials or poor design features are not always responsible for failure, and other factors may be superimposed on particular inherent vulnerabilities of the biomaterial and/or design. Moreover, a well-meaning and heavily tested modification of biomaterials and/or designs to solve an important complication can lead to unintended and unpredictable consequences. Indeed, abnormal physiological responses of a patient due to an implant or treatment with a therapeutic device can be expected in some, but is not always predictable in a random subgroup of patients. It is up to the biomaterial scientists and engineers to alert and educate the public and their representatives, as well as the corporate community, to these possibilities. In this way, the biomaterials scientist or engineer can play a major role in ensuring the success of medical devices and implants.

Bibliography

1. Baretich MF. Medical device incident investigation. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2007;43:302–305.

2. Baumgartner FJ, Munro AI, Jamieson WR. Fracture embolization of a Duromedics mitral prosthesis. Tex Heart Inst J. 1997;24:122–124.

3. Becker C. Stuck with the check? Guidant recall raises questions of medical tab. Mod Healthc. 2005;35(20):22.

4. Blackstone EH. Could it happen again? The Björk–Shiley convexo-concave heart valve story. Circulation. 2005;111:2717–2719.

5. Blot WJ, Ibrahim MA, Ivery TD, et al. Twenty-five–year experience with the Björk-Shiley Convexoconcave Heart Valve – A continuing clinical concern. Circulation. 2005;111:2850–2857.

6. Browne JA, Bechtold CD, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG. Failed metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties: A spectrum of clinical presentations and operative findings. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2313–2320.

7. Bull B, Fuchs JC, Braunwald NS. Mechanism of formation of tissue layers on the fabric lattice covering intravascular prosthetic devices. Surgery. 1969;65:640–648.

8. Carthey J, de Leval MR, Reason JT. The human factor in cardiac surgery: Errors and near misses in a high technology medical domain. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:300–305.

9. Charnley J, Kamangar A, Longfield MD. The optimum size of prosthetic heads in relation to the wear of plastic sockets in total replacement of the hip. Med & Biol Eng. 1969;7:31–39.

10. Chin HP, Harrison EC, Blankenhorn DH, Moacanin J. Lipids in silicone rubber valve prostheses after human implantation. Circulation 1971; 43, I-51–I-56.

11. De Stefano V, Finazzi G, Mannucci PM. Inherited thrombophilia Pathogenesis, clinical syndromes, and management. Blood. 1996;87:3531–3544.

12. Georgiadis GS, Lazarides MK, Panagoutsos SA, Kantartzi KM, Lambidis CD, et al. Surgical revision of complicated false and true vascular access-related aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1284–1291.

13. Girling J, de Swiet M. Acquired thrombophilia. Bailleres Clin Ob Gyn. 1997;11:447–462.

14. Goodman GR. Medical device error. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;14:407–416.

15. Gross JM, Shu MCS, Dai FF, Ellis J, Yoganathan AP. A microstructural flow analysis within a bileaflet mechanical heart valve hinge. J Heart Valve Dis. 1996;5:581–590.

16. Holmes Jr DR, Kereiakes DJ, Garg S, Serruys PW, Dehmer GJ, et al. Stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(17):1357–1365.

17. Holt G, Murnaghan C, Reilly J, Meek RM. The biology of aseptic osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;460:240–252.

18. Huiskes R. The causes of failure of hip and knee arthroplasties. Neder Tijdsch Voor Geneesk. 1998;142:2035–2040.

19. Maron BJ, Hauser RG. Perspectives on the failure of pharmaceutical and medical device industries to fully protect public health interests. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:147–151.

20. Mendelson KM, Schoen FJ. Heart valve tissue engineering: Concepts, approaches, progress, and challenges. Ann Biomed Engin. 2006;34:1799–1819.

21. Rahimtoola SH. Valve prosthesis–patient mismatch: An update. J Heart Valve Dis. 1998;7:207–210.

22. Rumisek JD, Albus RA, Clarke JS. Late Myobacterium chelonei bioprosthetic valve endocarditis: Activation of implanted contaminant?. Ann Thorac Surg. 1985;39:277–279.

23. Schoen FJ. Pathologic findings in explanted clinical bioprosthetic valves fabricated from photooxidized bovine pericardium. J Heart Valve Dis. 1998;7:174–179.

24. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Tissue heart valves: Current challenges and future research perspectives. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:439–465.

25. Schoen FJ, Goodenough SH, Ionescu MI, Braunwald NS. Implications of late morphology of Braunwald–Cutter mitral valve prostheses. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;88:208–216.

26. Schoen FJ, Levy RJ, Piehler HR. Pathological considerations in replacement cardiac valves. Cardiovasc Pathol. 1992;1:29–52.

27. Shepherd M. SMDA ’90 (Safe Medical Devices Act of 1990): User facility requirements of the final medical device reporting regulation. J Clin Eng. 1996;21:114–148.

28. Silver MD, Wilson CJ. The pathology of wear in the Beall model 104 heart valve prosthesis. Circulation. 1977;56:617–622.

29. Strabelli TM, Siciliano RF, Castelli JB, Demarchi LM, Leão SC, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae valve endocarditis resulting from contaminated biological prostheses. J Infect. 2010;60(6):467–473.

30. Trumpy IG, Roald B, Lyberg T. Morphologic and immunohistochemical observation of explanted proplast-Teflon temporomandibular joint interpositional implants. J Oral Maxillo Surg. 1996;54:63–68.

31. Valji K, Linenberger M. Chasing clot: Thrombophilic states and the interventionalist. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;10:1403–1416.

32. Walker AM, Funch DP, Sulsky SI, Dreyer NA. Patient factors associated with strut fracture in Bjork–Shiley 60° convexo-concave heart valves. Circulation. 1995;92:3235–3239.

33. Yoganathan AP, Corcoran WH, Harrison EC, Carl JR. The Bjork–Shiley aortic prosthesis: Flow characteristics, thrombus formation and tissue overgrowth. Circulation. 1978;58:70–76.

34. Yoganathan AP, Reamer HH, Corcoran WH, Harrison EC, Shulman IA, et al. The Starr–Edwards aortic ball valve: Flow characteristics, thrombus formation, and tissue overgrowth. Artif Organs. 1981;5:6–17.