THOUGH HISTORIANS HAVE NOT IDENTIFIED the Iranian plateau as a region of economic dynamism, urban expansion, or manufacturing for export in the pre-Islamic period, it became the most productive and culturally vigorous region of the Islamic caliphate during the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, only a century and a half after its conquest by Arab armies.1 The engine that drove this newfound prosperity was a boom in the production of cotton.

In the eleventh/fifth century the cotton boom petered out in northern Iran while the agricultural economy in general suffered severe contraction. At the same time, Turkish nomads for the first time migrated en masse into Iran. These developments resulted in long-term economic change and the establishment of a Turkish political dominance that lasted for many centuries. The engine that drove the agricultural decline and triggered the initial Turkish migrations was a pronounced chilling of the Iranian climate that persisted for more than a century.

Such are the major theses of this book. Though the argumentation to support them will concentrate on Iran, their implications are far-reaching. Iran’s prosperity, or lack thereof, affected the entire Islamic world, and through its connections with Mediterranean trade to the west and the growth of Muslim societies in India to the east it affected world history. The same is true of the deterioration of Iran’s climate. Not only did it set off the fateful first migration into the Middle East of Turkish tribes from the Eurasian steppe, but it also triggered a diaspora of literate, educated Iranians to neighboring lands that thereby became influenced by Iranian religious outlooks and institutions, and by the Persian language. These broader implications will be addressed in the final chapter, but first the substance of the two theses, which have never before been advanced, must be argued in some detail.

If the evidence to back up the proposition that Iran experienced a transformative cotton boom followed by an equally transformative climate change were abundant, clear, and readily accessible, earlier historians would have advanced them. So what will be presented in the following pages will be less a straightforward narrative than a series of arguments based on evidence that may be susceptible of various interpretations.

With respect to the latter thesis, the cooling of Iran’s climate, the crucial evidence is clear, but it only recently became available with the publication of tree-ring analyses from western Mongolia. The question in this case, therefore, is not whether scientifically reliable data exist, but whether or to what degree information proper to western Mongolia can be applied to northern Iran over 1500 miles away. This question, along with a variety of corroborative information, will be addressed in chapters 3 and4.

The case for an early Islamic cotton boom, on the other hand, rests on published sources that have long been available. However, these sources only yield their secrets to quantitative analysis, as will be seen in this chapter and the next. The methodology of applying quantitative analysis to published biographical dictionaries and other textual materials constitutes a third theme of this book.

In 1970, Hayyim J. Cohen published a quantitative study of the economic status and secular occupations of 4200 eminent Muslims, most of them ulama and other men of religion. He limited his investigation to those who died before the year 1078/470.2 Overall, he surveyed 30,000 brief personal notices in nineteen compilations that are termed in Arabic tabaqat, or “classes.” These works are generally referred to in English as biographical dictionaries. The subset of notices that he extracted for quantitative analysis were those for whom he found specific economic indicators—to wit, occupational epithets like Shoemaker, Coppersmith, or Tailor—included as part of the biographical subject’s personal name. All the compilations Cohen used covered the entire caliphate from North Africa to Central Asia. None was devoted to a specific province or city, except for a multivolume compilation specific to the Abbasid capital of Baghdad.

Commercial involvement with textiles, Cohen found, was the most common economic activity indicated by occupational epithets, and from this he inferred that the textile industry was the most important economic mainstay of the ulama in general. For individuals dying during the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, textiles accounted for a remarkably consistent 20 to 24 percent of occupational involvement. He does not specify which epithets he included in the “textiles” category, or the relative importance of each of them, but the master list of trades that accompanies his article includes producers and sellers of silk, wool, cotton, linen, and felt, along with articles of clothing made from these materials. (Whether he classed furs with textiles or with leather goods is unclear.)

Cohen’s sample amounted to only 14 percent of the total number of biographies he surveyed because in an era before surnames became fixed and heritable, individuals were distinguished by a variety of epithets (e.g., place of origin or residence, occupation, official post, distinguished ancestor), some chosen by themselves and some derived from the usage of others. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the occupational distribution of the 14 percent identified by the name of a trade roughly mirrors the economic profile of the entire 30,000. Scholarship on Islamic subjects, by and large, was not a highly remunerative activity in the Muslim societies prior to the twelfth/sixth century. So most Muslim scholars, unlike Christian clergy supported by the revenues of churches or monasteries, had to earn a secular livelihood to maintain their families. To be sure, the son of a prosperous trader or craftsman who had the leisure to become highly educated in religious matters might have taken the occupational name of his father without himself engaging in the trade indicated, but it seems unlikely that he would have adopted an occupational name entirely unrelated to his or his family’s position in the economy. Whether at first or second hand, then, the abundance of textile-related names, as opposed to the total absence of, say, Fishers or Potters, almost certainly reflects the broad economic reality of the class of people included in the biographical dictionaries.

Cohen’s study provides a baseline against which to compare a parallel analysis of a large biographical compilation devoted to a single city, the metropolis of Nishapur in the northeastern Iranian province of Khurasan.3 With a population that grew from an estimated 3000 to nearly 200,000 during the period of Cohen’s survey, Nishapur was one of the most dynamic and populous cities in the caliphate, probably ranking second only to Baghdad itself.4 Compiled in many volumes by an eminent religious scholar known as al-Hakim al-Naisaburi, this work survives today only in an epitome that contains little information beyond the names of its biographical subjects. But that is sufficient for our purposes.

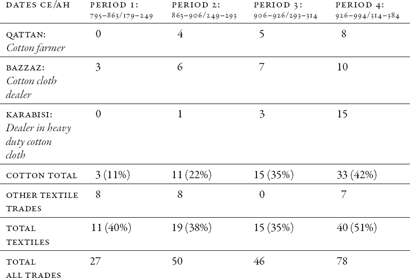

Table 1.1 shows that in each of the periods covered, the proportion of individuals engaged in basic textile trades in Nishapur (“Total Textiles”) is 50 to 100 percent higher than the proportions uncovered by Cohen for the caliphate in general. The dominant role of textiles in the economic lives of Nishapur’s religious elite would have loomed still larger if tailors and vendors of specific types of garments had been included, but they have been left out, since it is uncertain which of them may have been included in Cohen’s calculations.

TABLE 1.1 Occupational epithets in al-Hakim’s Ta’rikh Naisabur

Looking specifically at the tenth/fourth century, cotton growers and cotton fabric vendors alone accounted for 35 to 42 percent of all occupational epithets in Nishapur. This elevated level was noted by Cohen: “As for cotton, the biographies of Muslim religious scholars indicate that Khurasan province was a big centre for its manufacture.”5 This preponderance of cotton farmers and merchants is all the more striking in view of the absence on the table of any cotton growers at all down to the final third of the ninth/third century. In other words, if Iran really did experience a transformative cotton boom, as is being argued here, it would seem to have reached Nishapur only in the late ninth/third century. As we shall see later, however, other types of data show that cotton began to become a major enterprise farther to the west, in central Iran, a century earlier.

Also of interest is the fact that during Period 1 of table 1.1, which immediately preceded the apparent start of the boom in Nishapur, five of the people dealing in textiles other than cotton traded in felt, a commodity produced mainly by nomads in Central Asia and imported into Iran by caravan. This hint that Central Asian imports still dominated Nishapur’s fiber market in the early ninth/third century is reinforced by the fact that there are also five fur merchants recorded for the period. (Since I am not certain whether Cohen considered fur a textile, I have not included furriers in the table.) In sum, felt and fur, two products coming from beyond Iran’s northeastern frontier, together made up 30 percent of all textile/fiber commerce conducted by Nishapur’s religious elite before the rise of cotton.

The occupational preferences of Nishapur’s ulama apparently changed from imported felts and furs to locally produced cotton. The data from Period 3 covering the last third of the ninth/third century, 863 to 906/250–315, confirm this shift . Cotton was then clearly emerging as a major new product, going from 11 percent to 22 percent of all trade epithets, but three felt merchants and two furriers are still recorded for this period. However, during Periods 3 and 4, covering the period down to the start of the eleventh/fifth century, felt dealers disappear from al-Hakim’s compilation, with only one furrier mentioned. Imported fibers were no longer of major interest to Nishapur’s religious elite.

For the skeptically inclined reader, deducing a cotton boom from the changing percentages of occupational names distributed among a couple of hundred religious scholars may seem strained. But leaving precise numerical calculations aside, cotton clearly became an important part of the Iranian economy during the early Islamic centuries. The comparison with Cohen’s data indicates a role for cotton in Iran that was far greater than that played by all textile production combined in the caliphate as a whole, particularly considering that if he had chosen to systematically exclude Iranians from his tabulations, his total for non-Iranian ulama involvement in textile trading would have been appreciably lower.

An even more striking attestation to the historical significance of cotton’s emergence as a key product in the Iranian agricultural economy, however, is the fact that little or no cotton seems to have been grown on the Iranian plateau during the Sasanid period prior to the Arab conquests of the seventh/first century.6 The soundness of this statement is fundamental to the argument of this chapter. Hence, the evidence on which it is based needs to be explored in some detail.

Although at least one scholar, Patricia L. Baker in her book Islamic Textiles, has asserted that large quantities of cotton were exported from eastern Iran to China before the rise of Islam,7 The Cambridge History of Iran takes a more cautious position: “The study of Sasanian textiles … is hampered by an almost total lack of factual information. The meagerness of the historical sources is matched by the paucity of textile documents.”8 The discussion that follows this introductory sentence deals extensively with silk and secondarily with wool. Cotton is nowhere mentioned.

Nevertheless, Baker’s statement refers to trade with China and to “eastern Iranian” provinces that may have been outside the borders of the Sasanid empire. In fact, evidence from east of the Sasanid frontier, which roughly coincided with the current frontier between Iran and Turkmenistan, does confirm the presence of cotton cultivation there, but it falls well short of indicating large-scale production or trade. Moreover, it strongly implies links with India rather than with the Sasanid-ruled Iranian plateau.9

Archaeologists have dated some cottonseeds excavated in the agricultural district of Marv, northeast of today’s Iranian border, to the fifth century CE, and cotton textiles have been found in first-century CE royal burials of the Kushan dynasty in northern Afghanistan.10 At the other end of the Silk Road, there are occasional Chinese textual references to cotton “from the Han dynasty [ended 220 CE] or later,”11 and in 331 CE an embassy from the Central Asian principality of Ferghana, today part of Uzbekistan, arrived at a royal court in Gansu in northwest China with tribute goods that included cotton and coral.

The mention of coral is a first clue that India played a key role in the spread of cotton to Central Asia. India was not only the land of origin of cultivated cotton but also a much more likely source of coral than Iran. Moreover, the Kushan and post-Kushan periods (i.e., the first five centuries CE) saw a prodigious territorial expansion of Indian Buddhism in western Central Asia, providing the basis for the entry of Buddhism into China. The names are recorded of some 150 Buddhist pilgrims, both Indian and Chinese, who passed through Gansu, the province linking northern China with Inner Asia, and helped spread Buddhism in China between the second and sixth centuries.12 Surviving itineraries of these wayfarers demonstrate that the normal practice for pilgrims seeking sacred manuscripts in India was to travel northwestward through Gansu, then traverse the Silk Road to Sogdia (today Uzbekistan), a region of non-Sasanid Iranian-speaking principalities east and north of the Oxus River; and finally, to turn southward to Bactria, the old Kushan territory in northern Afghanistan. From there they traversed the high passes of the Hindu Kush Mountains before descending into India. Though many stops at Buddhist monasteries en route are detailed in the written accounts, none indicates an extension of the pilgrim journey into Sasanid Iran. With respect to the relative importance of cotton as a trade good along this route, recent Chinese excavations at Khotan, a major entrepot on the Silk Road, have unearthed many textile fragments, 85 percent of them wool, 10 percent silk, and only 5 percent cotton.13 Other sources stress the predominance of silk as a trade good.14

Philology also points to India as the point of origin of the cotton reaching China from Bactria and Sogdia. The word for cotton in the Iranian language spoken at Khotan, known as Khotanese Saka, was kapaysa, a word that later appears as kaybaz in the eastern Turkic languages of Inner Asia. The word is clearly derived from Sanskrit karpasa, meaning cotton. Of similar derivation is the Persian word karbas, which in later Muslim times designated a kind of heavy cotton cloth.15

The occupational name Karabisi, which appears in table 1.1, that became frequent in Nishapur toward the end of the tenth century literally means “a dealer in karabis,” the plural of karbas. The form of this plural, however, is Arabic, not Persian, which would normally be karbas-ha. Because Arabic was heard only rarely in northeastern Iran prior to the fall of the Sasanid empire to invading Arab armies, the implication is that even though Sanskrit-derived words for cotton were known in Central and Inner Asia before the advent of Islam, the term karbas only entered Khurasan during the Islamic period. This would also accord with the comparatively late popularity of the word karbas in the Nishapur cotton industry. Karabisi is very uncommon as an occupational name farther west in Iran, where cotton came to be cultivated earlier than in Nishapur.

To sum up, before the Arab conquest cotton was grown, but was of limited commercial importance, in the vicinity of Central Asian urban centers such as Marv, Bukhara, Samarqand, and Ferghana, all of which had river water available for irrigation during the summer growing season. Although it is impossible to prove that its cultivation was unknown on the Iranian plateau,16 it was only after the Arab conquest that cotton took off as a major commercial crop in central Iran, which was almost entirely lacking in river water during the long, hot summers it needed to grow. This poses several crucial questions: Who introduced cotton to the Iranian plateau? Where was it grown? How was it irrigated? To whom was it sold? Why was it so successful? And, most enigmatically, what was its connection to the Islamic religion?

Before addressing these questions, we must start with some background. Historians generally recognize that the early Islamic centuries witnessed a remarkable surge of urbanization and cultural production in the piedmont areas surrounding the deserts of the central Iranian plateau. Cities like Nishapur, Rayy, and Isfahan, which had not previously ranked as major urban centers, grew to accommodate populations of more than 100,000 souls. Historians who have taken note of this growth have advanced several causative explanations, from Andrew Watson’s hypothesis that the spread of new crops increased calorie production and thereby touched off a demographic surge,17 to my own suggestion that conversion to Islam triggered a migration from countryside to city,18 to a more diffuse effort to relate the Muslim political unification of lands previously ruled by the Byzantine and Sasanid emperors to overall economic growth. What all of these approaches lack, to a greater or lesser degree, is a foundation in Iranian economic data.

The economic history of medieval Islam is a notoriously intractable subject. Financial documents of even the most rudimentary sort are virtually nonexistent, and economic matters rarely arise in the more discursive writings of the period. To be sure, coinage is abundant and carries informative inscriptions, but only spotty information is available about the relationship of the gold dinars and silver dirhams studied by numismatists to actual commercial transactions: What did things cost? What were people paid? What was the volume of production?19

Geographers and travelers do touch now and again on such relevant matters as trade routes, export commodities, and manufactures. But their comments seldom enlighten us on matters of quantity, value, and personnel engaged. We learn, for example, that rhubarb, turquoise, and edible clay were all prized exports from Nishapur, but we don’t know whether the annual volume of these goods was measured in tens of pounds or in thousands of pounds, much less how much a typical shipment might be worth, who its buyers were, or how many people were engaged in its production and shipping.

Textiles, of course, are different from rarities or luxuries like rhubarb and turquoise. They have long played a disproportionate part in world trade. People everywhere need to clothe themselves, and it is not unusual for imported fibers, as opposed to those that are locally produced, to dominate a region’s textile markets. Chinese silk in late antiquity; Spanish and English wool in late medieval and early modern Europe; American, Egyptian, and Indian cotton in the nineteenth century; and Australian wool in the twentieth century afford outstanding examples of fibers playing a powerful role in export economies.

Prior to modern times, no export product could achieve market dominance unless it commanded a market of sufficient size and profitability to offset the costs and risks of land or sea transportation, which were unfailingly expensive, perilous, and slow. For long-distance trade, the most desirable commodities were light in weight, high in value, steady in demand, easily packaged, and unaffected by slowness of transport. Fresh foods that could spoil or suffer from rough handling did not travel far, but dried or preserved foodstuffs did. At different times and places, vegetable oils; wine; grains; dried beans, fruits, and nuts; and salted fish, pork, or beef have all fed lucrative export markets. Nevertheless, some of these commodities were of such low unit value that high volumes were necessary to turn a good profit. By contrast, products that fit into the luxury category, such as spices, aromatics, dyestuffs, and gemstones, tended to be low in bulk and high in profit. However, demand for these items was often variable, because there is a limit to the amount of myrrh, ginger, or emeralds a society can absorb. In addition, some of these products, such as nutmeg, high-quality frankincense, and lapis lazuli, came from narrowly restricted locales, in the cases cited, Indonesia’s Banda Islands, Oman’s Dhufar province, and Afghanistan’s Badakhshan region.

Unlike all the previously mentioned products, textile fibers meet every test of market suitability. Whether shipped raw, as thread or yarn, or as finished fabric, textile fibers resist spoilage, pack efficiently, enjoy steady demand, and, depending on the degree of processing and fabrication, can have monetary values that are comparatively high in relation to bulk. Among these fibers, animal hair (used to make felt) and wool adapt less easily to changing demand than do cotton, flax, or silkworm filament. To be sure, Spain and England in their time witnessed deliberate large-scale conversions of cropland into pasturage in order to increase the production of wool. However, considerably less flexibility existed in regions like the Middle East, where animal husbandry took the form of wide-ranging nomadism in arid or semiarid regions. The nomads themselves fabricated woolen goods and felts for their own use and for occasional sale, but most grazing took place too far from a commercial center to make large-scale marketing of fleeces or hair convenient. A marketer interested in meeting or stimulating increased consumer demand would have had to improve collecting and marketing techniques, or enlarge the area devoted to pasture, or both. Because the producers were so often on the move, the former option was difficult. And so was the latter, because it was likely to involve conflicts with cultivators or landowners who had vested interests in keeping animals off their sown fields. So fiber production has usually played a secondary role in the pastoral nomadic economies of the Middle East and Central Asia. Trans-Asian camel caravans, for example, once included men with large sacks who trailed after the two-humped camels as they molted in the springtime and collected for eventual sale the camel hair that fell off or snagged on bushes. But this was purely ancillary to the camels’ main use as beasts of burden.

With vegetable fibers and the mulberry leaves that nurture silk worms there is inherently greater flexibility. As with most other agricultural crops, the acreage under production can increase or decrease, depending on market conditions. Yet cotton, linen, and silk differ substantially in their technical requirements.20 The case of silk, where silkworms have to be nurtured and then killed and the fiber of their cocoons painstakingly unwound, is well known. But linen production too entails great labor. After the flax seeds are removed by combing, the plant’s inner fibers must be freed. This process, known as retting, involves either partial decomposition in the field or the application of great amounts of running water. Then comes a drying stage, which is followed by braking, scutching, and hacking processes in which the fibers are freed from the boon, or woody portion of the plant. Once these steps have been completed, the fiber that remains for spinning amounts to only 15 percent of the harvested flax plant.

In comparison, cotton processing is less complicated and less onerous. The primary operations include beating the bolls to separate the fibers and remove any clinging bits of soil, removing the seeds by hand or with a gin, and carding, which consisted of raking the fibers out for spinning.21 In addition, cotton enjoys another advantage over flax and silk as an export commodity. The flax plant and mulberry tree can grow in a wide range of temperate climates, but cotton is strictly a warm-weather plant. Thus whenever cotton cloth has become known and its qualities appreciated in a temperate region that does not have the long, hot growing season and abundant water needed for local cultivation, a demand for imported fabrics has usually followed.

It may be hyperbolic to conclude from these considerations that cotton is historically the most important product ever in interregional trade, but the capacity of cotton farming to support entire economies is beyond question. The histories of India, the Nile Valley, the American South, and Soviet Central Asia all testify to this. The question to be asked with respect to Iran, therefore, is not whether cotton cultivation had the potential to transform the medieval Iranian economy, but whether in fact it did so.

Evidence on economic matters is as woefully lacking for the pre-Islamic period of Iranian history as it is for the early Islamic period. Studies of Sasanid Iran usually speak only in generalities about agriculture on the Iranian plateau. Scholars concur that the primary crops were wheat and barley and that various other foodstuffs were produced in smaller quantities for local consumption. In the area of agricultural technology, scholars are reasonably certain that the most distinctive feature of Iranian farming, the use of underground canals known as qanats to bring irrigation water to thirsty fields, dates as far back as the Achaemenid period of the sixth to fourth centuries BCE.22 Nevertheless, there is no measure of how frequently crops were irrigated by qanat, as opposed to springs and artesian wells, natural precipitation, seasonal runoff, or surface streams and canals.

Within the general profile of the agricultural economy of the Sasanid Empire, Iran’s plateau region seems to have produced only a few exportable commodities, mostly nuts, dried fruits, and saffron. Control of the land lay in the hands of great lords and lesser gentry, who are usually described as enjoying a rural lifestyle. The model of manorial life familiar from descriptions of the agricultural economy of medieval Europe, with, in the Iranian case, a lord’s adobe brick castle and outbuildings and one or more nearby villages forming a self-sufficient economic unit, is perhaps not too farfetched. Villagers were more or less self-sufficient after the lord had taken his share of the harvest. Wheat and barley provided basic sustenance for man and beast. When taxes were collected in kind, substantial quantities of grain might be laid up in government store houses, but there is little reason to suppose that grain was ever exported in significant quantity from the plateau region. There were no seaports or navigable rivers, and overland transport was too expensive for such bulky and low-value commodities. Instead, the stored grain was probably allocated, as it would later be under Muslim rule, to local military and administrative personnel, to armies in transit, or occasionally to the alleviation of hardship caused by drought or other local catastrophes.

Cities on the Iranian plateau, particularly in the north along the western portion of the Silk Road running from today’s Turkmenistan frontier to the Baghdad region in Iraq, seem typically to have been composed of a garrisoned fortress adjoining a walled enclosure. Judging from standard ratios of medieval urban density, the total walled area of such a city could typically accommodate a few thousand people. However, the existence of open space within the walls for sheltering villagers during times of rural unrest favors the lower end of these population estimates, around 3000 to 5000 people. In addition to providing local security against marauders, the purpose of these cities was primarily servicing and protecting the caravan trade between Mesopotamia and Central Asia, China, or India. In the southwest, the provinces of Fars and Khuzistan seem to have had somewhat larger urban centers and to have been more strongly linked to the comparatively well-urbanized culture of Mesopotamia.

Information about fiber use in the Sasanid period relates mostly to the elite strata of society. Visual evidence, surviving fabric specimens, and textual references show clearly that the upper classes favored silk garments woven with elaborate patterns. Vegetable and animal motifs within repeating geometric settings are commonly represented (fig. 1.1). Though Iranians eventually became abundant producers of silk, much Sasanid silk came from China as a staple of Silk Road caravans.23 Many patterns, however, were distinctly Iranian, indicating either that imported silk thread was woven into fabric after it reached Iran or that Chinese exporters designed fabrics specifically for export. The weaving techniques used in Sasanid fabrics were quite sophisticated, but little is known of weaving as a trade. If weaving in the Islamic period followed earlier occupational patterns, it is likely that weavers did not enjoy high social status in Sasanid Iran. As for ordinary villagers, little is recorded about their garments, though wool was undoubtedly in use, possibly alongside linen or hemp.

The accepted grand narratives of Iranian history take for granted the role of the plateau region as a rural hinterland for the capital province in lower Mesopotamia. They describe a land dominated by warrior nobles whose lives centered on warfare, hunting, and feasting, and whose aesthetic sense was most fully gratified by silk brocade garments and gold and silver plates and drinking vessels. A vast gulf yawned between these nobles and the common villagers, and there was little in the way of a middle social stratum. In the absence of large and dynamic cities, manufacturing and marketing were poorly developed.

FIGURE 1.1. Example of Sasanid silk brocade. (By permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

In the early Islamic centuries this pattern changed. The Arab conquests smashed the power of the Sasanid royal family and diminished (but did not destroy) the domination of the grand baronial families.24 Though crown estates and firetemple lands became the property of the caliphal state, great landowners and lesser landowning gentry continued to control most agricultural land, as is indicated by the frequent use of the term dihqan, referring to both large and small landowners, in accounts of the period down through the eleventh/fifth century. In the wake of the Sasanid defeat, the Arab victors planted garrisons and governing centers at strategic points throughout the country. These nodes of Muslim Arab influence and control were also economic centers from the very start. Local government officials oversaw the collection of taxes, a sizable portion of which were retained at the governing node, with the rest being sent west to the caliphal capital in Damascus or later Baghdad, or to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Of the sums retained locally, a large portion was distributed as military pay to the Arab garrison, which thus acquired purchasing power. Not surprisingly, this new class of warrior consumers attracted artisans and merchants interested in servicing their needs. Many of these were Iranians who converted to Islam and wanted to live in proximity to other Muslims; others were Christians, Jews, or, less frequently, Zoroastrians. Over time these military-administrative nodes of caliphal control grew in size and matured into full-fledged cities. However, this geographical pattern of government and nascent urban development, in and of itself, says nothing about the agricultural hinterland, where Sasanid taxation procedures probably continued with little change during the first century and more of Arab rule.

To make the case for a cotton boom transforming the economy, we will have to explore the linkages between land ownership, irrigation, and the market for agricultural commodities. In schematic form, the remainder of this chapter will argue the following:

1. The new elite of Arab Muslims, along with an initially small number of Iranian converts to Islam, sought to become landowners.

2. In the absence of a policy of displacing the traditional Zoroastrian landowners, the Muslim newcomers utilized a principle of Islamic law that granted ownership to anyone who brought wasteland under production.

3. The vast, arid piedmont areas around Iran’s central plateau could be made arable by using the Iranian technological tradition of digging underground irrigation canals (qanats).

4. Qanats were expensive, and the necessity of recruiting farm labor and constructing a village on newly arable desert land added substantially to their cost.

5. Wheat and barley grown on qanat-irrigated land cost more to produce but probably had higher yields than grain irrigated by cheaper means, such as natural rainfall or canals diverting water from surface streams.

6. Unlike wheat and barley, which were normally grown as winter crops, cotton was a summer crop that needed both a long, hot growing season and the steady irrigation that a qanat could supply.

7. As a result of these considerations, wealthy Muslims who wished to become landowners invested in digging qanats and establishing villages on desert lands that they thereby came to own. To make their investments profitable, they planted cotton and fed it into a growing urban textile market, and increasingly into a lucrative export market.

8. For a period of time in the ninth/third century, Iran showed signs of a dual agriculture economy in which traditional Zoroastrian landowners grew primarily winter grains and Muslims grew primarily summer cotton.

Some of these propositions, especially the phrase “dual agricultural economy” in the final point, sound altogether too modern for the period we are dealing with. They assume a degree of market rationality that certainly did not exist. They ignore local social, political, and economic variables, including such obvious matters as proximity to markets. And they imagine a calculus of agricultural investment that is unrealistically isolated from noneconomic factors, such as rural security, ethnic friction, and family rivalries and rankings. They also ignore the fact that in Central Asian areas that already had some familiarity with cotton growing, such as Marv in today’s Turkmenistan and Bukhara and Samarqand in today’s Uzbekistan, qanats were not used. There crops of every sort were irrigated by canals carrying water from the Murghab and Zeravshan rivers.

Nevertheless, these propositions briefly describe, grosso modo, what happened in some of Iran’s northern piedmont areas, and they call attention to three issues in particular: the problem of land ownership in a postconquest situation, the connection between investment and irrigation, and the connection between Muslims in particular and the growing of cotton. Just as earlier we used quantifiable evidence from a single Iranian city to illustrate the major role that cotton played in the medieval Iranian economy, as seen from the position of the Muslim religious elite, so the quantifiable evidentiary base for the propositions we have just given will come mostly from a single district centered on the city of Qom, which was largely established by immigrant Arabs and has become, today, Iran’s paramount center for religious education. Our argument will center on place-name analysis and tax data.

Place-name analyses have proven of great historical value in virtually every part of the world.25 Names placed on the land often last for centuries and tell the tale of population movements, political and social change, and linguistic evolution. In Iran, however, village names do not seem to be particularly durable. For example, around Nishapur scarcely a single village name survives from the pre-Mongol period. Although this could be seen as testifying to the destruction of civilized life so often ascribed to the era of Mongol dominion in the thirteenth/seventh century, it may equally stem from the long-term self-destructive nature of qanat irrigation. No matter how carefully an underground canal is engineered and maintained, water running through earth will eventually take its toll. When a qanat eventually caves in, there may be no alternative but to abandon the village it served and pioneer a new qanat and village nearby.

Can qanat-irrigated villages be distinguished by name from other villages? To explore that question with a view to analyzing village names in the early Islamic centuries, we will look at a distinctive class of names for inhabited places (as opposed to rivers, mountains, etc.) that accounts for a large share of all of Iran’s toponyms today. This class consists of compounds in which the first element refers to a person, usually by name but sometimes by title, position, or other identifier, and the second element is abad, which identifies the place as built and inhabited. For convenience sake I will term this the fulanabad pattern, using the Arabic-derived word fulan, meaning “somebody” or “so-and-so,” as a placeholder for the personal designator that begins the compound.

A plausible supposition is that the person named in the first part of a fulanabad compound is the person who “founded” the town or village, though what “founding” consists of is not immediately evident or always the same. Support for this supposition may be found in India, where the handful of fulanabad place-names (e.g., Heydarabad, Ahmedabad) listed in the index of A Historical Atlas of South Asia are mostly substantial cities that can readily be identified with a historical founder whose act of foundation is preserved in the name.26 In Iran, however, scarcely any sizable cities have fulanabad names. The overwhelming majority of the many thousands of fulanabads are villages. In a small percentage of cases, the name of the village does suggest formal establishment by a ruler or official (e.g., Shah-abad, Soltan-abad), but the vast preponderance of the fulan elements in Iranian village names cannot be identified with any particular ruler or official. For Iran’s Ostan-e Markazi, or “Central Province,” which includes both Tehran and Qom, the top ten fulanabad names listed in the Farhang-i Jughrafiyai-i Iran, an exhaustive gazetteer published between 1949 and 1954, are listed in table 1.2.

This list suggests that if fulanabad villages are typically named after their founders, then the founders of the villages that exist today were mostly neither rulers nor officials, because over the last two centuries or so such illustrious individuals have more often been identified by title or honorific epithet than by an unadorned given name. This does not resolve the issue of “founding,” however. The personal name attached to a fulanabad village could be that of the owner of the village, rather than the founder. In this case, the fulan part of the name might have changed when the village passed from one owner to another. Yet this seems unlikely. Surviving eighteenth-/twelfth and nineteenth-/thirteenth-century documents recording land sales make it clear that village ownership was commonly divided among several parties.27 Deeds of sale covering between one and five sixths of a village—each sixth called a dang—are as common as those transferring full ownership. Yet the village has only one name, and the deeds do not indicate a change in that name. In addition, it seems unlikely that any tax administration would have tolerated the sort of rapid changes in name that might occur at a time of rural disorder or volatility in the real estate market that might have caused villages to change hands often.

TABLE 1.2 Modern village names in Ostan-e Markazi

| VILLAGE NAME | NUMBER OF VILLAGES |

| Hosein-abad | 44 |

| Ali-abad | 31 |

| Hajji-abad | 23 |

| Hasan-abad | 22 |

| Mohammad-abad | 21 |

| Ahmad-abad | 21 |

| Abbas-abad | 18 |

| Mahmoud-abad | 18 |

| Qasem-abad | 17 |

| Karim-abad | 14 |

| Source: Farhang-i Jughrafiai-i Iran (Tehran: Dayirah-i Jughrafiai-i Sitad-i Artish, 1328–1332 [1949–54]), 9 v. | |

The not infrequent employment of the name form fulanabad-fulan, wherein a personal name different from that included in the primary fulanabad compound is appended to the compound, may have been a convenient way of indicating current ownership without changing the foundation name of the village. Many of these appended fulans contain precisely administrative ranks, honorific titles, or other markers of individual identity that are almost wholly absent from fulanabad names proper. (As table 1.3 shows, the word or words following a fulanabad name also include terms that are not proper names or personal epithets.)

Proceeding on the assumption that the initial personal components of fulanabad names do indeed reflect the names of village “founders,” we will ignore these words that come after fulanabad and look at the full array of the initial personal components as a reflection of the personal names in use among what we may tentatively term “the village founder class.” The names in table 1.2, for example, are all among the most common Iranian male given names of the pre–World War II era. But a list of the most popular names in the ninth/fourth century, the period of our putative cotton boom, would be quite different. Most notably, the third most frequent fulan, the title Hajji, or “Mecca Pilgrim,” which in post-Mongol times became so important in many parts of the Muslim world as to effectively substitute for a personal name, never appears as a part of a personal name in the biographical dictionaries of the earlier period.

TABLE 1.3 Examples of names and terms suffixed to modern fulanabad village names

| PERSONS | ADMINISTRATIVE STATUS |

| Khaleseh | |

| Bu al-Ghaisas | Shahi |

| Kadkhoda Hossein | Tribes |

| Hajji Qaqi | Inanlu |

| Hajji Agha Mohammad | Ahmadlu |

| Arbab Kaikhusro | Afshar |

| HONORIFIC TITLES | Qajar |

| Amir Amjad | PHYSICAL FEATURES |

| Majd al-Dowleh | Olya (upper) |

| Dabir al-Soltan | Sofla (lower) |

| Qavvam al-Dowleh | Wasat (middle) |

| Moshir al-Soltaneh | Kuchek (small) |

| Ain al-Dowleh | Bozorg (large) |

The question of what can be concluded from the personal components of early fulanabad toponyms will arise again later, but other characteristics of fulanabad villages must be explored first. The most important of these is water supply. The 1949–54 gazetteer includes for most villages a note as to their source or sources of water. Tabulating these sources for the interior piedmont regions of Iran, it becomes apparent that there is a high correlation between the fulanabad name form and irrigation by qanat. In the Ostan-e Markazi 765 out of 2708 villages, or 35 percent, bore a fulanabad name. For 133 of these the gazetteer listed no water source. However, of the remainder, 75 percent—473 out of 632—were watered by qanat. As for villages bearing some other name form, only 34 percent were watered by qanat. By comparison, in the Caspian provinces, where rainfall supplies water in abundance, qanats are almost nonexistent; accordingly, fulanabad village names rarely occur.

The correlation between a fulanabad name and qanat irrigation is far from absolute; but it is sufficiently striking to raise the suspicion that in the case of fulanabad villages, “founding” a village involved paying for the digging of a qanat. It must be noted, however, that there is considerable disagreement among Iranian scholars on just this point. On the one hand, Aly Mazaheri, the Iranian scholar who translated into French an Arabic treatise written in 1017/407 on the calculations entailed in engineering a qanat, remarks in his introduction:

Having discovered water, studied the terrain, and provided the underground channel to the fields destined to be irrigated, the “waterlord” [hydronome: English equivalent patterned on “landlord”] built the village. In Eastern Iran (Khurasan) he bore the prestigious name of paydagar: the discoverer, the midwife, the pioneer, the founder, the creator of the village. It is thus that the term apady, “irrigation,” has come to mean “water source,” village, cultivation, town, civilization, and that the word abad, “irrigated by,” follows the name of the founder in designating so many sites of Persian civilization between the Bosphorus and the Ganges. Thus beside Ali-Abad, Mohammad-Abad, Hossein-Abad, etc., so numerous in Iran, we have Hyder-Abad, Ahmad-Abad, Allah-Abad, etc. throughout the vast world where Persian was once the administrative language.28

A contrary view is maintained by the Iranian sociologist Ahmad Ashraf. Writing in the Encyclopaedia Iranica, he defines the word “Abadi” as:

Persian term meaning “settlement, inhabited space;” it is applied basically to the rural environment, but in colloquial usage it often refers to towns and cities as well. The Persian word derives from Middle Persian apat, “developed, thriving, inhabited, cultivated” (see H. S. Nyberg, A Manual of Pahlavi II, Wiesbaden, 1974, p. 25); the Middle Persian word is based on the Old Iranian directional adverb a, “to, in” and the root pa, “protect” (AIR Wb., cols. 300ff, 330, 886). Some Iranian social scientists have suggested an analysis into ab “water” and a suffix –ad … and this error is also found in some early modern dictionaries (e.g., Behar-e ʿajam, 1296/1879; Asaf al-logat, Hyderabad, 1327–40/1909–21; Farhang-e Ananderaj, 1303/1924).29

Though modern philological research must be respected as providing the last word on the subject, the folk etymology associating the word with ab, or “water,” should not be disregarded. If the early dictionary compilers cited by Ashraf lent their authority to such a folk etymology, it may be that a simple-minded linguistic association between abad and “water” has a long enough tradition in popular use to have made it a significant factor in rural naming despite its being philologically in error. That is to say, 100 years ago or a 1000 years ago, a qanat builder thinking about the name to give to his new village may well have had a linguistically incorrect association with water in mind. In any event, the philological debate over whether village founders felt that water was intrinsically associated with the fulanabad place-names they opted for has no bearing on the strong quantitative correlation between qanat irrigation and villages designated by such names.

Visualizing the process by which a qanat-watered village comes into being is essential to our historical argument. In thousands of instances, the cultivation of village lands depends entirely on a qanat. However, there are certainly exceptions. Sometimes other water sources exist, and a qanat simply makes the water supply more abundant and more consistent for all purposes year round. In other cases, water from other sources may suffice for growing winter crops (e.g., wheat and barley), which benefit from the winter being the rainy season in most of Iran, but be insufficient for summer crops (e.g., cotton), which grow throughout the hot, dry season and utilize the regular flow from a qanat.

For simplicity’s sake, let us assume that as a prospective village founder, you are not simply improving an existing water supply or changing your mix of crops, but creating a village from nothing in a previously uncultivated stretch of desert. Your first step is to call in a specialist in qanat engineering.30 His job is to site a “mother well” somewhere on the upslope of a nearby range of mountains or hills (fig. 1.2). The “mother well” establishes the depth of the water table and the rate at which water seeps from the surrounding moist soil into an empty well. Once the “mother well” has clarified these conditions, the specialist calculates the direction and length of an underground channel that will lead water by gravity flow from the “mother well” to a point in the arid countryside where it will ultimately flow forth as a surface stream usable for irrigation, drinking, washing, and so forth. He marks that route for the actual diggers and determines the depth of each well to be dug along the qanat’s course.

FIGURE 1.2. Diagram of qanat irrigation tunnel.

The expertise demanded by these procedures is amply remunerated by the village entrepreneur, for a qanat whose slope is insufficient (i.e., less than approximately 1 meter per thousand) will silt up, and one that is too steep (i.e., more than approximately 3 meters per thousand) will be scoured out and made to collapse by the flow of the water. Because the qanat may extend for several miles beneath ups and downs of hilly terrain, the slope calculation is particularly vital. The eleventh-/fifth-century Arabic treatise on slope calculation mentioned earlier testifies to the skill of the qanat engineer. Written by a noted mathematician, it is one of the few works on practical engineering devoted to agricultural matters in premodern Islamic lands.31

Once the qanat engineer has done his job, the village founder brings in experienced qanat diggers to supervise the excavation of the channel. Working backward from the projected point of exit toward the “mother well,” the diggers sink wells every 30 meters or so to the depths prescribed by the qanat engineer. When they reach the right depth, a horizontal tunnel is excavated connecting each well with its downstream neighbor. The wells admit air for the diggers and allow the excavated dirt to be hauled up and dumped around the well-head. The dumping creates the characteristic “row of craters” that traces the qanat’s course on the surface and, in modern times, is particularly apparent from the air. Candles are used to check the alignment of the tunnel as it grows. The water begins to flow as soon as the tunnel reaches the water table. Only then can the irrigation of the land begin.

Several observations may be made about this scenario. First, there is no presumption that the land on which the village is slated to come into being must be owned by the village founder prior to the digging of the qanat. I am here distinguishing ownership of a specific parcel of land from various broader rights of exploitation that might reside with a monarch, a territorial lord, or a tribe. Rights of the latter sort certainly have existed in Iranian history; but had they normally been asserted so rigidly as to make every newly founded village automatically the property of the monarch, lord, or tribe, it is hard to imagine thousands of individual entrepreneurs investing in the costly and lengthy process of qanat excavation. Nor do narrative sources represent individual rulers or regimes as undertaking the construction of scores or hundreds of qanats. Thus the strong correlation of ordinary male first names with fulanabad toponyms, and of the fulanabad name pattern with qanat irrigation strongly suggests that individual entrepreneurs did commonly finance qanats. Moreover, surviving documents make it clear that individuals have owned villages and have transferred their ownership by deed of sale for at least several hundred years.

One might draw an analogy between the relationship of a prospective Iranian village founder to a ruler, territorial lord, or tribal leader holding broad territorial rights and the relationship of a homesteader to the U.S. government in the nineteenth century. The federal government owned the nation’s undeveloped “public” land categorically, but for a nominal sum it ceded ownership of specific parcels to individual homesteaders on condition that they invest the time and labor needed to make the land productive. The government then benefited from the taxes paid on the product of the land. From at least the late eighth/second century, Islamic law has embodied this reward for entrepreneurship in the form of recognizing freehold ownership for people who make dead land (ard al-mawat) productive. The principle was embodied in a hadith, or saying of Muhammad, that states: “The rights of ownership belong to him who revives dead land, and no trespasser has any right.”32 However, a famous passage from the second-century BCE Greek historian Polybius relates that the ancient Achaemenid rulers had granted qanat builders five generations of freedom from financial dues, so the exemption in Islamic law may simply have continued a pre-Islamic practice.33

A second observation is that the farmers who cultivate the land once the water begins to flow from the qanat cannot be supported by the product of that land from the very outset of the project. Because the land produces nothing and has no inhabitants before the qanat is dug, there can be no stored surpluses from earlier seasons. Thus until the first harvest is brought in, the villagers must gain their sustenance from elsewhere, most likely the resources of the village founder. This obviously makes the investment of the village entrepreneur substantially greater than simply paying for the qanat. He must also supply plow animals, seed, food rations for workers, and building materials for the village houses.

The third observation is that the people who assemble to build a village and cultivate the land in a previously desert locale must come from someplace. How are they assembled? In some modern instances it would appear that prosperous or overpopulated villages sometimes spawned new villages. This process may account for place-names of the fulanabad-fulan form that have identical first components but are distinguished only by an adjective in the last element of the name, the adjective in most instances being ʿolya (upper) and sofla (lower), or kuchek (small) and bozorg (large). One might hypothesize that when the earlier of such a pair of villages outgrew its water supply, the landlord decided to dig a new qanat and build a new village nearby using supplies and labor drawn from the original village. But aside from these cases, it seems likely that a person seeking to found a village in a period of static or negative population growth must have borne the burden of recruiting farmers for his entrepreneurial project. Given the hardships that surely would have accompanied the first season or two in a new village, it seems likely that village founders faced with such conditions offered inducements to men who were willing to leave wherever they had been living, possibly against the wishes of their former landlord, and join in the new enterprise.

One form of inducement that seems to have been common was an offer to become part of a boneh, or “work team.” Unlike landless agricultural laborers or villagers possessing cultivation rights to specific plots of land, members of bonehs enjoy a collective right to a share in the produce of village lands.34 Though the history of the boneh system is not well known, it is plausible to imagine a village entrepreneur assembling his initial cohort of cultivators by giving them a stake in the productivity of the village through “work team” membership. This would explain the finding of geographer Javad Safinezhad that the geographical portion of Iran in which the boneh system is utilized almost exactly coincides with the area in which qanats are used for irrigation (fig. 1.3).35 Though Safinezhad makes no specific correlation between bonehs and fulanabad place-names in particular, it stands to reason that for the modern period that has been the focus of his research, if most fulanabad villages had qanats, they also had bonehs.

FIGURE 1.3. Map of water resources and boneh zone in Iran. (After Javad Safinezhad, “The Climate of Iran” ([1977].)

Let me summarize now the tentative conclusions that emerge from this examination of village names from the 1950s:

1. The personal component in fulanabad village names probably designates the village “founder,” and the idea of “founder” probably includes not only the initial excavation of the village qanat but a variety of other substantial expenses.

2. Fulanabad (and probably other) villages were commonly owned by individuals with sufficient freehold rights to permit transfer of the village to another owner by sale.

3. Fulanabad names usually do not change when a village changes ownership.

4. The personal components of fulanabad names reflect the onomasticon, or name-list, current at the time the villages were founded.

5. Fulanabad villages are irrigated by qanat much more often than villages with other sorts of names.

6. Qanat irrigation correlates geographically with the employment of “work teams” (bonehs) for cultivating the land.

7. Fulanabad villages probably organized their cultivation around bonehs more frequently than did non-fulanabad villages.

These conclusions are tentative, but they will prove helpful in guiding our efforts to understand the information contained in the earliest large list of village names surviving from the period after the Arab conquest of Iran.

A K. S. Lambton36 and Andreas Drechsler37 have written extensively on the early history of the city of Qom and on the contents of Taʾrikh-e Qom, a local history compiled in Arabic by Abu Ali Hasan b. Muhammad b. Hasan al-Qummi and translated into Persian in 1402–4/804–6. The Persian translation alone survives, and it contains only five of an original twenty chapters. Hasan al-Qummi began to assemble the work in 963/352 but did not finish it until 990/379 because of a prolonged absence from the city.

Lambton and Drechsler offer many valuable observations relating to the wealth of fascinating information in this work. The protagonists of the historical narrative are Arab settlers of Yemeni tribal background, and the account of their conflicts with the native population, their rise to positions of dominance in the city of Qom proper, and their arguments with the central caliphal government over tax assessments is complex, highly detailed, and minimally related to agricultural production.

However, our current inquiry concerns itself primarily with the information relating to taxation. Lambton notes that Hasan al-Qummi drew on eight documents that she terms “tax schedules.” Drechsler does not entirely agree with her translation of this unusual Arabic word, wadiʿa, but for convenience sake I shall follow Lambton’s usage. The dates given for the tax schedules encompass the entire ninth/third century:

| Tax Schedule 1 | 804/188 |

| Tax Schedule 2 | 808/192 |

| Tax Schedule 3 | 836/221 |

| Tax Schedule 4 | 839/224 |

| Tax Schedule 5 | 841/226 |

| Tax Schedule 6 | 897/265 |

| Tax Schedule 7 | 903/290 |

| Tax Schedule 8 | 914/301 |

Although al-Qummi is neither systematic nor complete in his citation of information from the schedules, it appears that each of them contained inter alia both the rates of taxation for specific crops and information on individual taxable locales. We shall return later to the matter of tax rates, for our first concern is with the names of the taxable locales. These are listed in thirty-four groupings, some labeled tassuj, some rustaq, and some unlabeled. Though Lambton states that the term tassuj refers to an administrative sub-district within a larger district called a rustaq, a comparison of village names suggests that in some cases tassuj and rustaq may have been interchangeable. For our purposes it is reasonable to proceed on the assumption that all thirty-four headings given by al-Qummi refer to districts of some sort and the names listed below them, to taxable locales in those districts.

The task of assembling a definitive list of discrete taxable locales suitable for comparison with the list of villages so conveniently laid out for the modern period in the Farhang-i Joghrafiyai-i Iran is complicated by al-Qummi’s practice of listing in different locations place-names belonging to the same district but coming from different tax schedules. For example, for the district of Tabresh, which may be related to the modern town of Tafresh west of Qom, he lists forty-one taxable locales from Tax Schedule 1; three more from Tax Schedule 3, one of them duplicating a name already given; and thirty-one more from Tax Schedule 5, including sixteen duplicates. In addition to these, Tax Schedule 2 lists thirty-nine names under the rubric Tabresh, none of which overlap the combined fifty-eight names given in the other three schedules. And Tax Schedule 4 lists eight names, which similarly do not duplicate those on the other lists. It would appear, therefore, that there were at least two districts with more or less the same name.

Problems of this sort are compounded by inconsistent spelling and by the absence of any indication of al-Qummi’s purpose in listing the names. He does not classify the places listed according to types of ownership or taxation, nor does he indicate why he lists so few names from some districts and so many from others, or why he lists no names at all from Tax Schedules 6 and 7.

After taking into account, to the degree possible, all the duplications and spelling variations, the final composite list totals 1271 names spanning the entirety of the ninth/third century. This would appear to be the longest list of Iranian toponyms specific to a single urban hinterland to survive from the early Islamic period. A comparison of this total with the 2708 villages listed in the 1950s for the entire Ostan-e Markazi, the larger region in which Qom is now situated, suggests that al-Qummi’s list, despite its peculiarities, probably represents most of the taxable rural locales of his time.

However, one difference between the modern and the medieval lists must be noted. Where 35 percent of the modern names are of the fulanabad form, the list from the Taʾrikh-e Qom contains only 344 fulanabad names, or 26 percent of the total. On the basis of the modern correlation between fulanabads and qanat irrigation, one might surmise from this difference that qanat irrigation was not as widely employed in the ninth/third century as in the twentieth/fourteenth. But before exploring this conjecture we should look at the personal names represented in the fulanabad compounds (table 1.4).

What stands out in this list of the twelve most common fulanabad names is that only one of them, Hormizdabad, is Persian. A look at the complete list of fulanabads confirms this low representation of Persian names. At least 80 percent of the fulanabad names are clearly Arabic, and the percentage could be a bit higher, because a few names that look Persian might actually be Arabic. This disproportion between Arabic and Persian stands out when we consider village names of the pattern fulanjird, in which the second component, jird or gerd, is often taken to signify the rural estate or manor of one of the gentry. Every one of the twenty-nine fulanjirds has a Persian name or word as the first part of the compound.

TABLE 1.4. Fulanabad village names in Ta’rikh-e Qom

| VILLAGE NAME | NUMBER OF VILLAGES WITH NAME |

| Mohammad-abad | 33 |

| Ali-abad | 22 |

| Musa-abad | 11 |

| Yahya-abad | 9 |

| Ahmad-abad | 9 |

| Malik(Milk, Mulk)-abad | 8 |

| Imran-abad | 7 |

| Sulaiman-abad | 7 |

| Hormizd-abad | 7 |

| Hasan-abad | 6 |

| Ishaq-abad | 6 |

| Ja‘far-abad | 6 |

This comparison puts in relief the dual agricultural economy of early Islamic Iran postulated earlier. If we assume that the association between qanat irrigation and the fulanabad name pattern that is apparent in modern toponyms from the Qom region represents a long-standing historical relationship, then it is hard to escape the conclusion that in the ninth/third century, village entrepreneurs who built qanats were overwhelmingly of the Muslim faith, whether they were Arabs or Iranian converts who had taken Arabic names.

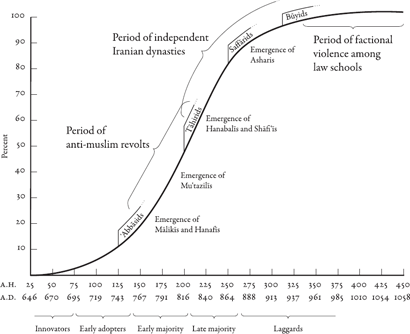

Of course, there might be nothing out of the ordinary in this conclusion if it could be established that the central plateau region of Iran had become overwhelmingly Muslim by the early ninth/third century, but this is not the case. In an earlier work entitled Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period I proposed a quantitative technique for estimating the rate of growth of the Muslim community in Iran. In the three de cades that have elapsed since that book’s publication there have been numerous reservations expressed about the quantitative onomastic method on which it was predicated, but there has been little disagreement with its main finding, namely, that conversion to Islam took place slowly over a period of four centuries or more. In fact, the most challenging criticism, that of Michael Morony, argued that conversion took place at an even slower pace.38 Thus the once popular “fast calendar” of conversion, which maintained that Islam grew with great rapidity following the Arab conquests, either because of military coercion or from a desire to escape a caliphal head tax ( jizya) levied on Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews, has generally been replaced in scholarly circles with a “slow calendar” extending over several centuries (fig. 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4. Graph of the growth of the Muslim community in Iran. (From Bulliet, Conversion to Islam [1979].)

Figure 1.4 reproduces from my earlier book a hypothesized curve of Iranian conversion.39 It shows that the growth of Iran’s Muslim community was approximately 30 percent complete in 804/188, the date of Qom’s earliest tax schedule, and 90 percent complete in 914/301, the date of the eighth and last schedule. However, the last schedule made only negligible additions to the list of village names, and no names at all are given from the two schedules preceding it. Thus the effective terminus ad quem of the list of village names is the date of Tax Schedule 5, namely, 841/226, by which time the graph of conversion indicates a level of 60 percent.

If, however, as Morony and others have persuasively argued, my onomastic technique underestimates conversion in rural areas, these percentages may be somewhat too high. But they are probably not too low. The consensus view is that Iran in the ninth/third century saw a rapid growth of Islam but was very far from being a predominantly Muslim country until the very end of the century. Even then, large Zoroastrian populations persisted in some rural areas.

The list of most popular fulanabad names in table 1.4 provides an additional clue that the villages in question were founded before or toward the beginning of the ninth/third century, when the proportion of Muslims in the population was still quite low, rather than at the end. Four of the twelve names appear in both the Bible and the Quran: Musa = Moses, Yahya = John the Baptist, Sulaiman = Solomon, and Ishaq = Isaac. The popularity of such scriptural names in the Iranian biographical dictionaries shows a distinct pattern: During the eighth/second century they enjoy substantial popularity, amounting to some 30 percent of all names given by converts to Islam to their sons. However, as conversion to Islam accelerated during the ninth/third century, this popularity quickly ebbed. Fathers became more interested in publicly affirming Islam by giving their sons names like Mohammad and Ahmad than in giving names that had earlier offered a sort of protective coloration—being either Muslim, Christian, or Jewish—when Muslims of Iranian ethnicity were few and far between. By 950/338 scriptural names had dropped to only 5 percent among converts’ sons.40 Though coincidence cannot be ruled out, the fact that the four scriptural names in table 1.4 show up in 27 percent of the 124 Arabic-named fulanabads on the list of most popular village names fits the earlier period far better than the later. This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that a number of quite uncommon Arabic fulan names included on the list of fulanabads in Qom (e.g., Ahwas—five villages, Shuʿaib—three villages) almost certainly relate to specific Arab leaders that are identified in the Taʾrikh-e Qom as being politically influential in the early de cades of the century and even before.41

In light of the overall timetable of conversion and the onomastic evidence pointing to the late eighth/second to early ninth/third century as the most probable period of village genesis, the 80 percent predominance of Arabic names among the fulanabad villages of the Qom district points clearly to a disproportionate participation of Arabs and/or Iranian Muslim converts in the founding of new villages. A possible alternative explanation might be that the fulanabad pattern somehow in and of itself signified Muslim land ownership, and that Arabs or Muslim converts who acquired villages from Zoroastrian owners changed their old names to fulanabad names, conceivably as a symbolic effort to plant Islam on the land. This, however, is belied by the 20 percent of the fulanabads that do not have Arabic names. If the fulanabad pattern had indeed, in and of itself, signified Islam, its adoption by Zoroastrian landowners would have been nonsensical. Therefore, whatever the abundance of fulanabads signifies, it is something that relates much more strongly to the Arab/Muslim portion of the population than it does to the Iranian/Zoroastrian portion.

Several other place-name patterns corroborate this impression of a difference between Arab/Muslim agriculture and Iranian/Zoroastrian agriculture. One has already been mentioned, the twenty-nine exclusively Persian fulanjirds. Another concerns names beginning in bagh, or “garden.” At least nineteen of the twenty-five “garden” locales contain Arabic fulan names (e.g., Bagh-e Idris, Bagh-e Abd al-Rahman). This makes them roughly 80 percent Arabic, just like the fulanabads. In addition, of the ten locales with names beginning in sahraʾ, or “desert,” only one is non-Arabic. The common denominator of the fulanabad, bagh, and sahraʾ names is water. Gardens were commonly watered by qanat, and a similar qanat association for the village names compounded with sahraʾ will be explained later. Most of the thirty-five bagh and sahraʾ names, it should be noted, come from just three tax districts.

By contrast, another specialized term for a taxable locale is much more strongly associated with the Iranian–Zoroastrian sector. Mazraʿeh, meaning “cultivated field,” but with an implication of dry farming, shows up seventy-seven times in plural or singular form either as a specifically named taxable entity (e.g., Mazraʿeh-ye Asmaneh, Mazraʿeh-ye Binah) or as an appendage to the name of a particular village (e.g., Binastar “and its cultivated fields” [wamazareʿiha]). Only a quarter of these citations include Arabic names, however. Thirteen show up in the form of a fulanabad “and its cultivated field(s),” and seven refer to individuals with Arabic names. Only one mazraʿeh is listed for the three districts that have a majority of the bagh and sahraʾ names. From this one might surmise that some districts had a much higher concentration of Arab–Muslim villages than others.

The conclusion these number games lead to is that types of property names that are strongly associated with qanats—fulanabad, bagh, and sahraʾ—frequently incorporate Arabic personal names, whereas toponyms that are unrelated to water (as well as those naming rivers and streams) rarely incorporate such names.

Our survey of the modern list of village names in the Qom region established a strong correlation between the fulanabad name pattern and irrigation by qanat. Projecting that correlation onto the (early) ninth-/third-century list of fulanabads, we can most easily explain the 80 percent share of Arabic fulans by imagining a powerful wave of qanat building and village founding carried out primarily by Arabs and/or Iranian converts to Islam. Is this a sound hypothesis? The eleven-century gap between the modern gazetteer and the Qom village list is a very long period, and naming practices could have changed many times. So there is no way of proving directly that the fulanabad-qanat association has remained consistent throughout Iranian history. To make this association all but certain, we must turn to the economics of cotton cultivation.

Hasan al-Qummi records the recollection of the old men of Qom that before the coming of the Arabs, barley, carroway seeds, and saffron were the only crops cultivated.42 Whether this is literally true or not, it is unlikely, for reasons already given, that any significant amount of cotton was cultivated in Sasanid times. Tax records prove that this situation changed greatly sometime after the conquest. The tax assessments per jarib for wheat, barley, and cotton are shown in table 1.5.

TABLE 1.5 Tax Rates of Various Crops

* Ta’rikh-e Qom, 121

† Ibn Hawqal, Configuration de la Terre (Kitab Surat al-Ard), tr. J. H. Kramers and G. Wiet (Paris: G.-P. Maissoneuve & Larose, 1964), 296.

Interpreting fixed tax rates, as opposed to a series of actual market prices, runs the risk of failing to consider unknown factors. Even so, looking at the ratios between the rates for grain and cotton, it is hard to imagine any factors that would substantially alter the conclusion that cotton farming was more profitable than grain farming. No farmer would have continued to plant cotton if his profit had been insufficient to pay his taxes, particularly at the beginning of the tenth/fourth century, when converting his irrigated acreage from cotton to wheat would have given him a tax rate ten to twenty times lower.

Another indicator of cotton’s value may be found in the ratio between cotton and saffron. Saffron is now and probably always has been one of the world’s most costly agricultural commodities, and one that is normally sold by the gram or the ounce. The hand labor of plucking the red top inch of the stigma of a small purple crocus is so enormous that saffron sells today for $45 to $60 an ounce. The rate for saffron on Tax Schedule 1 (804/188) is 15 dirhams per jarib, about the same as for wheat and barley, and less than half the rate for cotton. On Tax Schedule 7 (904/291) it is 62 dirhams, double the rate for cotton. By this comparative standard, which must reflect a greatly enhanced appreciation for saffron, the value of cotton fell somewhat during the course of the ninth/third century. But cotton continued to be a high-value crop, because by that time saffron was taxed at twenty times the rate for wheat and barley.

Was the apparent bonanza for cotton farmers in the Qom area in the ninth/third century as great as the one Egyptian or Carolina cotton farmers would enjoy in the nineteenth/thirteenth century? Probably not. It must be kept in mind that even if all the fulanabad villages grew cotton, they amounted to only 26 percent of the taxable locales around Qom. In terms of acreage, therefore, wheat and barley for local consumption doubtless continued to dominate Iranian agriculture by a wide margin. The cotton trade profited a relatively small number of growers. But because it was tied directly to cloth manufacturing and the export market, these growers played a major role in the urban and interregional commercial life of their districts.

A steady tax rate throughout the ninth/third century shows that cotton’s profitability persisted. Soil depletion must have been a problem, as it is anywhere cotton is grown, but there was no shortage of unspoiled land if water how to identify a cotton boom could just be brought to it. Accounting for the steep decline in the taxation levels of wheat and barley from the beginning of the ninth/third to the middle of the tenth/fourth century is another matter. Particularly striking is the differential between rates for grain grown on irrigated as opposed to unirrigated land. One might suppose that the profitability of cotton would have prompted grain farmers to shift to the new crop, thereby reducing grain production and raising the market price of wheat and barley. Though no market prices that might prove this have been preserved, a plausible interpretation of the astoundingly low tenth-/fourth-century tax on irrigated grain fields is that the assessors who fixed the rates were bent on discouraging conversion to cotton by those wheat and barley farmers whose land was well enough watered to make this feasible.

Though the idea of using tax policy to discourage conversion from grain to cotton seems too modern for medieval times, exactly such a policy may have been prompted by a growing problem of sustaining burgeoning urban populations. If the cotton boom began, as we are hypothesizing, when desert lands that had previously been barren were first cultivated, then the acreage devoted to staple grains would not have been affected. Yet part of the agricultural labor force would have shifted to nonfood production. Moreover, as the boom continued, the coordinated growth of city-based textile production and marketing would have become one of the important factors contributing to the dramatic growth in urban population levels generally observed in the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries.43 Rural–urban migration would thus have compounded the problem of rural workers shifting from food grain to cotton production by luring even more villagers away from the countryside completely. As a greater and greater proportion of Iran’s working population took up residence in cities or devoted their labor to growing cotton, grain production seems to have become less and less adequate for supporting people who were no longer engaged in producing food.

I have argued in my book Islam: The View from the Edge44 that precisely this pattern of imbalance between city size and rural food production made Iran vulnerable to severe food shortages and urban unrest in the eleventh/fifth century, and I propose later in this book that a change in climate also contributed to a deteriorating food situation at that time. But the falling tax rates on grain during the preceding century may well have signaled an early awareness of this developing problem. Despite the suspiciously modern tenor of this sort of tax policy, it might be noted that in the nineteenth/thirteenth century, when Iran’s leaders had no better understanding of the science of economics than their predecessors had had 1000 years earlier, a governor of Isfahan reacted to a spectacular rise in profits from growing poppies and exporting opium by requiring that farmers plant one jarib of grain for every four of poppies, lest food grains disappear from the market.45