IN HIS BOOK THE TURKS IN WORLD HISTORY, Carter Findley outlines the geographical features of the Turco-Mongolian steppe lands and then makes the following wise comment: “Only a few short, foolish steps lie between describing these environments and advancing environmentally determinist arguments about them.”1 As we turn to the topic of climatic change, we shall see how far we can advance in the direction he warns against.

My thesis will be that Iran experienced a significant cold spell in the first half of the tenth/fourth century, followed by prolonged climatic cooling in the eleventh/fifth and early twelfth/sixth centuries. The colder weather affected not just Iran, but Central Asia, Mesopotamia as far south as Baghdad, Anatolia, and Russia. First will come the evidence for this climate shift . Then we shall advance cautiously down the deterministic road by exploring both the more speculative and the more certain effects of the apparent cooling. The more speculative argument will correlate the hypothesized Big Chill with a general agricultural and demographic decline in the northern districts of the Iranian plateau that included the effective end of the cotton boom. What renders this speculative is a lack of a consistent correlation of scientific evidence with climatic events in places that may also have been affected, such as northern China, and a shortage, though not a total absence, of strong anecdotal evidence corresponding to what should have been the coldest years at the turn of the twelfth/sixth century.

As for the more certain impact of the cold, this involves the folk migration into northeastern Iran of the Oghuz Turks, known in Arabic as the Ghuzz and usually described in the sources of the period as Turkomans. The textual, geographic, and biological data associated with the first two episodes of tribal relocation in the first half of the eleventh/fifth century, and their correspondence with anecdotal evidence of bad weather, correlates too closely with the strictly scientific evidence to be considered mere happenstance.

At the end of January in 926/313 heavy snow fell in Baghdad. Before this day there were six days of intense cold. Then after the snowfall the cold became even sharper, exceeding all bounds to the extent that most of the date palms in Baghdad and its environs perished, and the fig and citrus trees withered and died. Wine, rosewater, and vinegar froze. The banks of the Tigris iced up at Baghdad, and most of the Euphrates froze at Anbar [at the same latitude as Baghdad]. At Mosul [200 miles to the north] the Tigris froze completely so that pack animals crossed it. A hadith reciter named Abu Zikra assembled a class on the ice in the middle of the river, and they took dictation from him. Then the cold broke with wind from the south and heavy rain.2

On November 24, 1007/398 snow fell in Baghdad. It accumulated to one dhiraʿ in one place and to one-and-a-half dhiraʿ in another. [A dhiraʿ is a unit of length equal to the average distance from elbows to fingertips.] It stayed on the ground for two weeks without melting. People shoveled it from their roofs into the streets and lanes. Then it began to melt, but traces of it remained in some places for almost twenty days. The snowfall extended to Tikrit [80 miles to the north], and letters arrived from Wasit [100 miles to the south] mentioning the fall there between Batiha and Basra, Kufa, Abadan, and Mahruban.3

So reports the twelfth-/sixth-century man of religion Ibn al-Jawzi (d. 1200/596) in his Baghdad-based chronicle Al-Muntazam fi Taʾrikh al-Muluk waʾl-Umam, the published portion of which begins in the year 871/257. These snowfalls were eighty years apart, but they were not unique occurrences. Ibn al-Jawzi’s descriptions of less vivid episodes of winter cold will be detailed later in this chapter. Yet only one of his severe-cold stories dates to the half century preceding the year 920/308. For that date he relates the following: “In July of this year, the air got so cold that people came down from their roofs and wrapped themselves in blankets. Then during the winter severe cold damaged the dates and trees, and a lot of snow fell.”6 The closest Ibn al-Jawzi comes to reporting severe winter weather before that year is in a report for January 904/291, when snow fell on one day from noon until evening.7 In other words, during the half century covered by the chronicle prior to the frigid winter of 920/308, and presumably for many de cades before that, severe winter cold was so uncommon in Baghdad that a five-hour snow shower in January was big enough news to be preserved in historical memory.

Today a five-hour snow shower in Baghdad would be as startling and memorable as it was in 904/291. As for a November blizzard blanketing the city with two feet of snow and staying on the ground for more than two weeks, as is reported for 1007/398, it would be meteorologically inconceivable. Modern weather data covering every month from 1888 to 1980 show the twenty-four-hour average temperature of Baghdad in the month of November to be 63 degrees Fahrenheit. The average for December is 52 degrees. January, the coldest month of the year, has a twenty-four-hour average temperature of 49 degrees. These averages, which take into account both the high and low temperatures of the day, show that a significant and long-lasting snowfall in Baghdad is a virtual impossibility in today’s climate. Even if some snow did fall during a cold night, it would melt the next morning; and the orange and fig trees that died in 926/313 would survive the brief chill.

The cautious historian must take into account, of course, the possibility that Ibn al-Jawzi’s reports are mere historiographical artifacts. He reported these weather events in the late twelfth/sixth century, more than 200 years after they supposedly occurred. So he clearly depended on earlier writers whose works are no longer extant. Do his bad-weather stories accurately reflect the severity of the events? Does he include every freeze and snowfall mentioned in his sources? We have no way of knowing. Does he use bad-weather reports for symbolic purposes, such as to hint at a correlation between meteorological anomalies and times of worldly turmoil and hazard? Probably not. His bad-weather years do not coincide in any obvious way with either political or religious calamities. Moreover, his reports, albeit secondhand, have the flavor of what must originally have been firsthand observation. The specification of which fluids froze, which he includes in more than one report, is particularly telling, because it reflects an awareness of freezing temperature differences in an era before thermometers. Today vinegar typically freezes at 28 degrees Fahrenheit and wine at 15 degrees. The freezing point of rosewater is more variable, as is that of animal urine, which varies, like saltwater, with the quantity of dissolved impurities.

Baghdad residents of Ibn al-Jawzi’s own time probably read his blizzard reports with the same sort of puzzlement that such reports elicit today, for the Big Chill that we shall be describing was certainly over by the middle of the twelfth/sixth century. Comparative evidence to this effect comes from the historian Ibn al-Fuwati (d. 1323/723), who compiled a Baghdad-based chronicle covering the years 1228–1299/625–698. His work provides an opportunity to test the quality of Ibn al-Jawzi’s reports. Over seventy years, Ibn al-Fuwati reports eight unusual floods on the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.8 This puts his observations of important natural phenomena (nothing imperiled the river city of Baghdad so much as a disastrous flood) on a par with Ibn al-Jawzi, who mentions unusual floods approximately five times in every fifty years over the substantially longer period that his chronicle covers. Yet Ibn al-Fuwati mentions only one winter with freezing weather and has no tales to tell about great blizzards or people crossing the frozen Tigris on horseback.

Of course, weather stories haphazardly preserved in chronicles do not constitute a trend. What is needed to link such reports into a pattern of climatic change is a context in which to place both the deep freeze of 926/313 and the blizzard of 1007/398. Field research completed in 1999/1419 by a team from the Tree-Ring Laboratory at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University provides that context.9 An analysis of tree-ring thicknesses from Solongotyn Davaa in western Mongolia, as shown on figure 3.1, indicates that the Iranian cotton boom described in the preceding chapters occurred during a period of notable warmth, except for a cold period between roughly 920/307 and 943/331. Then, at the beginning of the eleventh/fifth century, temperatures dropped significantly, reaching a consistent low level by century’s end. The cold then continued well into the twelfth/sixth century. Though the Lamont-Doherty researchers classify these data as statistically robust, their report has one apparent deficiency: western Mongolia is a long way from Iran.

FIGURE 3.1. Graph of tree-ring variation from Solongotyn Davaa, Mongolia. (After Rosanne D’Arrigo, Gordon Jacoby, et al., “1738 Years of Mongolian Temperature Variability Inferred from a Tree-Ring Width Chronology of Siberian Pine,” Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 28, no. 3, p. 544.)

What links these Mongolian tree rings to the winter weather of Iran is the meteorological phenomenon known as the Siberian High, a massive, clockwise-rotating, vortex (anticyclone) of high-pressure air that forms every winter north of the loft y mountain ranges ringing Tibet. As figure 3.2 illustrates, the Siberian High affects Eurasian winter weather all the way from northern China to Russia, though the effect can differ from one region to another because of encounters with other weather systems. In the Middle East, the Siberian High introduces cold air into northern Iran, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia. This regime not only can produce heavy winter snows when it contacts moist westerly winds from the Mediterranean, but can also block those winds and thus generate drought conditions along with severe cold.

Since the possibility of a lasting shift to a colder weather regime in the northern Middle East has not previously been discussed for this time period in the literature on climate history, it is necessary to ask how it relates to the generally accepted outlines of that history. The contemporary debate over global warming has attracted attention to evidence of climatic fluctuations in earlier times, but it has also biased that attention toward reconstructions of climate on a global or at least hemispheric scale, as opposed to more localized episodes. The unprecedented warming trend of the past hundred and fifty years has been compared to an earlier phenomenon that climate historians have labeled the Medieval Warm Period. This period was initially hypothesized on the basis of European data. Starting as early as the ninth/third century, depending on whose analysis you follow, the Medieval Warm Period is thought to have extended through the thirteenth/seventh century, after which the climate slowly worsened, eventually giving rise to the Little Ice Age. Various dates are assigned to this cooling trend; it was certainly well under way by 1600/1008,10 but no climate historian pushes it back as far as that snowy Baghdad November of 1007/398.

FIGURE 3.2. Map of Asia showing Siberian High.

The questions climate historians ask go beyond establishing local weather facts. Given the globally interconnected character of certain weather cycles, they want to know how broadly the effects of the Medieval Warm Period and Little Ice Age were felt. If they could be conclusively shown to be global, or even hemi sphere-wide, such a finding would bear on the general hypothesis that human activities have a recurrent history of affecting world climate. The search for such broad interconnections has led climatologists to combine and weigh data of many different sorts from many different areas, and this has introduced complexity into what began as local, and seemingly clear-cut, historical indications of warmer times giving way to colder times, and vice versa.

Our approach here departs from this analytical trend. It is local, at least in comparison with hemisphere-wide projections, and it concerns a single weather system, the Siberian High, and its effect on the northern Middle East. It also relies on a single scientific indicator, Mongolian tree rings. Yet the broad Medieval Warm Period hypothesis remains important for us because our proposal that there was a century of persistent cold winters in at least some regions affected by the Siberian High system apparently contradicts it.11 In Europe, evidence for a Medieval Warm Period is diverse and persuasive. Purely scientific indicators aside, ordinary historians put great store in textual evidence of Viking settlement in Iceland and Newfoundland, monastic wine production in England, and the expansion of grain farming in Estonia.12 What has come into question with the accumulation of data from other parts of the world, and with an ever-greater diversity and sophistication of scientific indicators, has been how widespread this European warm period was. According to the 2001 report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

current evidence does not support globally synchronous periods of anomalous cold or warmth over this timeframe, and the conventional terms of “Little Ice Age” and “Medieval Warm Period” appear to have limited utility in describing trends in hemispheric or global mean temperature changes in past centuries…. As with the “Little Ice Age,” the posited “Medieval Warm Period” appears to have been less distinct, more moderate in amplitude, and somewhat different in timing at the hemispheric scale than is typically inferred for the conventionally-defined European epoch.13

Willie Soon and Sallie Baliunas, in their exhaustive reappraisal of the debate published in 2003, express similar caution but reach a less negative conclusion: “The picture emerges from many localities that both the Little Ice Age and Medieval Warm Period are widespread and perhaps not precisely timed or synchronous phenomena…. Our many local answers confirm that both the Medieval Climatic Anomaly and the Little Ice Age Climatic Anomaly are worthy of their respective labels” (emphasis added).14

Given the reservations that have accumulated as more and more data have been analyzed, the question is whether this highly technical debate should frame our examination of weather data from early Islamic Iran. On the one hand, if the Medieval Warm Period did indeed constitute a consistent hemispheric phenomenon, the Baghdad hard freeze of 926/313 and blizzard of 1007/398 would be situated in the very heart of what should have been an era of record balminess. Ibn al-Jawzi’s reports would thus constitute an anomaly every bit as striking as the warm climate of Viking Iceland appeared to be to the historians who first called attention to it. Indeed, if historians of medieval Baghdad had been the first to arrive on the field of climatic battle, they might well have postulated a Medieval Cold Period. On the other hand, the scientific finding that the Medieval Warm Period may not be a “precisely timed or synchronous phenomen[on]” and that it “appears to have been less distinct, more moderate in amplitude, and somewhat different in timing at the hemispheric scale than is typically inferred for the conventionally defined European epoch” may provide the leeway for focusing exclusively on Iran, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia and putting on hold the question of how the experience of these areas compares with the undisputed warmth of northern Europe in the tenth/fourth through twelfth/sixth centuries.

A second set of Mongolian tree rings provides an example of how general climate indices can obscure more localized weather fluctuations. The tree rings in this case come from Tarvagatay, a Mongolian mountain pass not far from Solongotyin Davaa. The Tarvagatay sequence covers only 450 years instead of the 1700-year span of the Solongotyin Davaa data, but a published study compares the data for those years with a generalized temperature reconstruction for the Northern Hemi sphere based on a wide variety of indicators, precisely the kind of combined climate appraisal that has raised questions about the timing and extent of the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice age.15 For the early 1870s/late 1280s, both the Tarvagatay and the Solongotyin Davaa data indicate a sudden dip into near-record coldness. However, the multicomponent generalized Northern Hemi sphere curve shows stable temperatures in the cool range from 1850/1266 until around 1890/1307. As historians of Russia, Iran, and the Ottoman Empire will recall, the 1870s were severe famine years over a broad region affected by the Siberian High.16 Here is a case, then, where the Mongolian tree-ring data fit the weather actually experienced in the region we are concerned with far better than the hypothesized hemi sphere-wide indicator.

Although one must exercise caution in making inferences from two-or three-year anomalies, they should not be ignored.17 An instructive example comes from the year 855/241, when Solongotyin data not shown in figure 3.1 show another cold spike of near record dimension squeezed in the middle of a series of much warmer years. Since Ibn al-Jawzi’s chronicle does not begin until 871/257, the timeline of Baghdad weather that we have been using includes no information on this earlier year. However, another chronicler, Hamza al-Isfahani, whose work was completed in 961/349, fills in the gap:

In the year 855/241 a freezing cold wind emerged from the land of the Turks [Central Asia] and moved toward Sarakhs [in Khurasan]. Many people got a severe chill. Unable to resist the cold, coughing, and pain, they died. The wind then shifted from Sarakhs to Nishapur and reached the city of Rayy [modern Tehran]. Then this cold wind moved and blew to Hamadan and Holvan [in western Iran]. The wind was divided into two branches. One branch of wind moved to the right in the direction of the city of Samarra [on the Tigris north of Baghdad], and the other branch of severe cold wind reached the city of Baghdad. Many people were affected by it and died. Finally the wind reached the city of Basra [at the head of the Persian Gulf] and ended in Ahwaz. 18

Two year-specific correlations (855/241 and 1870–4/1286–90) between extreme cold signaled by Mongolian tree rings and severe cold or famine in the northern Middle East do not prove that the Solongotyin Davaa data always reflect the weather experienced in the western reaches of the region affected by the Siberian High. But they encourage one to think that the longer trends covering the ninth/third through twelfth/sixth centuries may well provide a reliable guide. Ideally, this conclusion would now be buttressed by a learned digression about how temperatures are inferred from the widths of tree rings and how fluctuations in the intensity and westward extension of the Siberian High relate to another climatic phenomenon called the North Atlantic Oscillation. Alas, the reader will have to turn elsewhere for this degree of scientific expertise on an extremely complex topic.19

Although the Mongolian tree-ring series sets the chronological parameters of the cold period we are concerned with here, textual descriptions better reflect the reality people lived through. Baghdad must have been on the fringe of the affected region, but the comments of its chronicler Ibn al-Jawzi provide our best source on unusual weather. Striking stories come from the de cades following the blizzard of 1007/398, when the tree rings indicate that winters were becoming increasingly cold:

1027/417

In this year, continuously from November to January, came a cold that no one had ever known before. Water froze solid throughout this period, including the shores of the Tigris and the wide canals. As for the water wheels and smaller channels, they were frozen solid. People suffered from this severity, and many were prevented from doing things and moving about.20

1028/418

In April large hail struck the districts of Qatrabbul, al-Nuʿmaniyya, and al-Nil and affected the crops in these areas. It killed many wild and domestic animals, and it was reported that one hailstone weighed two ratls or more [approximately two pounds]…. In November a cold wind blew from the west, and the cold lasted until the beginning of January. It went beyond normal. The banks of the Tigris froze along with vinegar, date wine, and the urine of animals. I saw a waterwheel that had stopped because of the frozen water, which had become like pillars in its holes.21

1029/419

We mentioned what happened to the dates last year because of cold and wind. So this year there was a dearth of animal feed, except for what was imported. It cost one jalali dinar [a gold coin] for every three ratls [approximately three pounds]. The cold became so intense that the shores of the Tigris froze, and the Bedouin stopped at ʿUkbara from making their migrations because of the freezing in the vicinity. Tens of thousands of date palms died in Baghdad.22

So much for Baghdad; our concern is Iran. If the severe winters reported for Baghdad derive from the Siberian High spreading a deep chill all the way from Mongolia, then there should be some parallel stories of intense cold from Iran. Here, however, we run into two complications. First, chronicles for Iran in this period are few and far between. And second, the climate of northern Iran, unlike that of Baghdad, is conventionally described in terms of “continental extremes”; that is, hot summers and cold winters. So the contrast between a normally cold winter and a truly frigid winter might not have been so evident, or so historically memorable, as a blizzard along the banks of the Tigris. Nevertheless, a detailed travel account by a wayfarer from Baghdad and certain passages in Hamza al-Isfahani’s tenth-/fourth-century chronicle and Abu al-Fazl Bayhaqi’s history of the third decade of the eleventh/fifth century parallel the dire reports of Ibn al-Jawzi.

Ahmad ibn Fadlan, the wayfarer, served as the secretary of an embassy sent by the Caliph al-Muqtadir to the king of the Turkish Bulgars then living on the lower reaches of the Volga River north of the Caspian Sea.23 The embassy departed from Baghdad in July 921/309, just a few months after the end of the capital’s first frigid winter as reported by Ibn al-Jawzi. It made its way through the Zagros Mountains and across northern Iran following the main route of the Silk Road all the way to Bukhara. From there, warned about the harshness of winter, it doubled back to the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and proceeded northward by boat toward the Aral Sea, or more properly, toward the flourishing farmlands of Khwarazm, the desert-framed region formed by the delta of the Oxus, where it entered the sea. There the embassy remained for four months, November through February, prevented from going further by the severity of the winter cold. For three of those months the river froze solid enough “from end to end” for horses, mules, and carts to travel on it as if it were a highway.24

Ibn Fadlan reports from that period an anecdote that will reenter our discussion in a different context in the next chapter. It seems that two men took twelve camels out to collect wood in some brushy swamps, but somehow they forgot to bring any implements for starting a fire. When they awoke after spending the night in the cold, they found that all the camels had frozen to death. Returning to his own personal observations, he remarks: “I saw weather where the cold made the market and streets so empty that a person could walk around without seeing or encountering a single soul. I used to come out of the public bath, and when I entered a house, I would notice that my beard was a single block of ice until I held it near the fire.”25 In March, the embassy set off again after buying some “Turkish camels.” Yet they still encountered snow that reached up to their camels’ knees and cold so severe as to make them forget the cold they had already endured during their stay in Khwarazm.26

Coming from Baghdad, Ibn Fadlan may not have been able to state explicitly that the cold he experienced in Khwarazm, which is today in Uzbekistan, was unprecedented, but the tenor of his account certainly implies this, particularly his reports of streets and markets being entirely empty as if even the local population had no familiarity with such severe weather. For comparison, the current minimum temperatures for Nukus, which is today the main city of the historic province of Khwarazm, are 30.7 degrees in November, when Ibn Fadlan’s embassy arrived, and 30.6 degrees in March, when it departed. The highs for these months are 50.4 and 51.1, respectively.

If Ibn Fadlan’s account marks the beginning of the tenth-/fourth-century cold spell, Hamza al-Isfahani describes the weather toward its end: “In the year 942/330 on the twentieth day of the month of Aban [mid-autumn] an unprecedented snow fell on the city [Isfahan].”27

In the early morning of Nowruz [the vernal equinox] in the year 943/332, when the residents of Isfahan woke up they witnessed a tremendous snowfall that had covered the whole city. The amount of snow was so great that people were not able to move around. We never had snow in the springtime. Following the snow a severe cold wind began to blow, and people started their Nowruz while all the trees were badly damaged. This wind that caused a lot of damage then shifted toward the eastern parts. The extent of damage was so great that people did not have fruit in that year.28

Turning to the more prolonged chill that began at the beginning of the eleventh/end of the fourth century, the historian Bayhaqi relates the following episodes:

1035/426

The Amir left Nishapur on Sunday 12 RabiʿI [25 January 1035] and took the Esfarayen road to Gorgan. It felt bitterly cold on the way, with very strong winds, especially up to the head of the Dinar-e Sari valley. We were traveling in the last month of winter and I, Buʾl-Fazl, was feeling so bitterly cold while riding my horse that when we reached the head of the valley I felt as if I was not wearing anything at all, in spite of the fact that I had taken all precautions and was wearing quilted trousers stuffed with feathers and a jacket of red fox fur and had donned a rainproof coat.29

This might be dismissed as normal hyperbole but for the fact that in October of the same year, Bayhaqi describes a defeated Turkish army fleeing across the frozen Oxus River. On this the noted Russian orientalist Wilhelm Barthold commented: “This story evokes some doubt; it is strange that as early as October a whole army could cross the Amu-Darya on ice.”30 However, the date is entirely compatible with the account already cited from Ibn Fadlan.

1037/429

During the whole time I was in the service of this great dynasty, I never witnessed a winter at Ghaznin [south of Kabul in Afghanistan] as hard as that of this year.31

1038/430

The Amir set out from Balkh [northern Afghanistan] heading for Termez [across the Oxus River in Tajikistan] on Monday, the nineteenth of this month [19 December 1038]. He crossed by the bridge and encamped on the plain facing the fortress of Termez. My master accompanied the Amir on this journey, and I went with him. It was bitterly cold, colder than anyone could remember in their lifetime…. The cold there was of another degree of intensity, and snow fell continuously. The army suffered more on this expedition than on any other.32

Other reports focus on crop failure and famine. The following notice in Bayhaqi from January of 1040/431 reflects the food situation following the frigid winter just mentioned:

1040/431

Nishapur was not the city I knew from the past: it now lay in ruins with only vestiges of habitation and urban life. A man (maund) of bread sold for three dirhams. Property owners (kadkhodayan) had torn off the roofs of their houses and sold them. A great number of people, together with their families and children, had died from hunger. The price of landed property had plummeted … the weather was bitterly cold and life was becoming hard to bear. Such a famine in Nishapur could not be recalled, and large numbers of people died, soldiers and civilians alike…. After we went back, a man of bread had become thirteen dirhams at Nishapur, and the greater part of the population of the city and its outlying regions died…. The position regarding food and fodder got so serious that camels were led as far as Damghan, and food and fodder brought back from there. It goes without saying that the Turkmens did not harass or hover around us, since they too were taken up with their own welfare, since this dearth and famine had spread everywhere. 33

Damghan was 250 miles from Nishapur, which indicates that crop failures affected all Khurasan. Bayhaqi picks up the story again at the time of Nowruz, the vernal equinox:

The Amir had pitched his tent on an eminence, and the army had encamped in battle formation, fully equipped. He was drinking wine, and was not going out in person with the main body of the army to confront the enemy but was waiting for the supplies of grain to arrive. The prices had spiraled up to such an extent that a man of bread went up to thirteen dirhams, but was still scarce, and as for barley, it was nowhere to be found. They ransacked Tus [40 miles east of Nishapur] and its surroundings, and whoever had even a man of corn was forced to part with it….Many people and livestock perished from lack of food and fodder, for it is obvious how long one can survive on a diet of rough weeds and bramble.34

By May the new crop of winter wheat and barley should have been nearing harvest, but the famine continued:

The Amir departed from there, heading towards Sarakhs [on the Iran-Turkmenistan border], on Saturday, 19 Shaʿban [5 May]. Before we could reach Sarakhs, countless horses dropped dead on the road, and the men were all immersed in deep despair from hunger and dearth of food. We reached there on 28 Shaʿban [14 May]. The town looked parched and in ruins, and there was not a single shoot of corn anywhere. The inhabitants had all fled, and the plains and mountains looked scorched, with not a speck of vegetation in sight. The troops were dumbfounded. They would go and fetch from afar bits of rotten vegetation that rainwater had washed up and deposited in the surrounding plains in former times, and they would sprinkle water on them and throw them before their mounts. The beasts would try a mouthful or two but would then lift up their heads and just stare until they died from hunger. The infantry were in no better state.35

The relative contributions of cold weather and drought to these two years of crop failure cannot be determined, but these were not the only famine years during the period of bad winters. In 1036/428, just three years earlier, Ibn Funduq, the local historian of the Bayhaq district just west of Nishapur, tells of a famine that necessitated the importation of food from Gorgan, a much warmer district near the Caspian coast.36 He also reports that for the next seven years, from 1037/429 onward, there were food shortages caused by a cessation of planting and harvesting outside the walled areas of the community. Ibn Funduq’s phrasing might lead the reader to surmise that rural insecurity was the central problem in this prolonged period of meager harvests, but Abu al-Fazl Bayhaqi’s detailed descriptions of cold winters and general Khurasani crop failure already cited for the years 1037–1040/429–431 clearly link the situation in the town of Bayhaq to the broader agricultural catastrophe.

A slightly earlier famine in the same region received an excessively florid account in the Kitab-i Yamini of Abu Nasr Muhammad al-ʿUtbi:

In the year 1011/401, in the province of Khurasan, generally, and in the city of Nishapur, particularly, a wide-spread famine, and a frightful and calamitous scarcity occurred…. Such was the extent of the calamity that, in the district of Nishapur, nearly 100,000 men perished, and no one was at liberty to wash, coffin, or inter them, but placed them in the ground in the clothes they had…. Some arrested their last breath by means of grass and hay, until all sustenance from sown fields and cultivated things were [sic] cut off…. And the Sultan during those days commanded, and sent an edict into the provinces of the kingdom, ordaining that the revenue officers and magistrates should empty the granaries of corn, and distribute amongst the poor and wretched…. And that year came to an end in the same state, until the produce of the year 1012/402 arrived, when the fire of that calamity was extinguished, and that extremity was remedied.37

Like the weather reports from Baghdad, these chance mentions of cold winters and famines in Khurasan cannot be sewn together into a seamless narrative of climatic change. (We experience the same uncertainty today when a chilly spring following a balmy winter casts doubt on the reality of global warming—until we look at the scientific data.) But the temperature curve derived from the Mongolian tree rings so closely reflects the dating of these weather events that one may cautiously advance the following conclusions:

1. The northern Middle East away from the Mediterranean (i.e., northern Iran, Mesopotamia from Baghdad north, and eastern Anatolia) experienced comparatively warm winters throughout the ninth/third and tenth/fourth centuries, with the exception of a sharp cold period from 920/308 to 943/331.

2. A deeper chill set in early in the eleventh/fifth century and lasted well into the twelfth/sixth century.

3. Serious famines recurred frequently during at least the early part of this cold period.

A search for bad-weather stories from the later de cades of the Big Chill, 1050–1130/441–524, has turned up relatively few, even though the tree-ring analysis points to continuing cold. But those that do appear bespeak the grinding impact of stress in the agricultural economy. The historian Ibn al-Athir (1160–1233/554–630) deals broadly with the political history of the entire Islamic world in his work al-Kamil fiʾl-Taʾrikh and rarely touchs on minor concerns like weather. Yet for the year 1098/492 he reports: “In Khurasan, there was a sharp increase in prices, with food prices becoming impossible. It lasted for two years. The reason was cold weather that entirely destroyed the crops. Afterward the people were visited by pestilential disease. A large number of them died, making it impossible to bury them all.”38 In the following year, he reports: “Prices in Iraq became unstable. A large measure (kurr) of wheat reached 70 dinars, or even a good deal more at some moments. The rains didn’t come, and the rivers dried up. [Winter is the rainy season in Iraq and in Anatolia, where springtime snowmelt normally causes the Tigris and Euphrates to flood.] So many people died that it was impossible to bury them all.”39

A different sort of testimony comes in a letter written in the year 1106/500 by the famous theologian al-Ghazali to the Seljuq ruler, Sultan Sanjar: “Be merciful to the people of Tus [al-Ghazali’s hometown near Nishapur in Khurasan], who have suffered boundless injustice, whose grain was destroyed by cold and drought, and whose hundred year old trees dried up at the roots…. For if you demand something from them, they will all flee and die in the mountains.”40 The closing sentence of this letter is particularly suggestive of the way in which inept government responses to hard times could drive villagers from the land and thus compound the disaster.

Why are there fewer reports of frigid temperatures, drought, crop failure, and famine after 1050/441 than before? The worst-case possibility from the perspective of the argument being made in this book would be that the Mongolian tree-ring data only sporadically reflect the weather of the northern Middle East and should not be given credence without specific textual corroboration. Yet it is precisely in the later de cades that the lowest temperatures are indicated, and this is also the point when cold weather hits China as well (see note 9). But there are other possibilities. Relying as he did on what he found in earlier writings, Ibn al-Jawzi may have come to the end of a chronicle that made frequent mention of weather phenomena and moved on to another chronicle that was less attentive to such things. Another alternative is that because weather events are best remembered when they are contrary to expectation, once people became accustomed to chillier winters, they were less inclined to mention specific instances of extreme cold or heavy snow.

A more dire interpretation would take note of the fact that the chronicles covering the period of the chill increasingly relate instances of nomadic depredations, urban factional conflict, rural insecurity, and, in the latest de cades, internecine warfare among members of the Seljuq family. If these events were in some measure negative consequences of the climate change, then the weather particulars in and of themselves might have become less noteworthy. In 920 or 1007 extraordinary freezes and snowfalls were big news. But as time passed, the crop failures, famines, and political disorder brought on by the Big Chill claimed the headlines. Iran went through bad times during this period. Agricultural land fell out of production (al-Ghazali’s letter to Sultan Sanjar suggests one reason why) and pastoral nomadism occupied more and more territory. Cities that had already been approaching the limit of the land’s ability to feed unproductive urban workers shrank, particularly in northern districts, and the educated elite emigrated to Central Asia, India, Anatolia, or the Arab lands.41 A heightened competition for dwindling resources, particularly in the cities, contributed to all kinds of social disorder, from lethal factional feuding between Sunni law schools to the rise of a violent sort of Ismaʿili Shiʿite sectarianism. However, in exploring these consequences of the Big Chill, we should look at how cotton farming in particular weathered the transition from warm to cold winters.

The Big Chill signaled by the Mongolian tree-ring data roughly coincides with a pronounced decline in Iran’s cotton industry. Cotton did not reappear as a fiber of major economic importance until early modern times, when printed fabrics inspired by Indian techniques became popular, and raw cotton from northern Iran began to be exported in large quantities to Russia, primarily in the nineteenth/thirteenth century.42 This does not mean that cotton made no return after the Big Chill. When it did, however, it was grown more in southern than in northern Iran, and its economic role was local rather than transregional.

André Miquel, in the first volume of his monumental La géographie humaine du monde musulman jusqu’au milieu du 11e siècle, which encompasses all parts of the Islamic world, lists the references to cotton growing and cotton export that he found in four major works of Arabic geography completed before the year 1000/390 (i.e., before the Big Chill).43 Half—twenty-one out of forty-one—pertain to the Iran-Afghanistan-Central Asia region, and two-thirds of those refer specifically to cities or provinces north of Isfahan. Miquel’s tabulation can be compared with a later geographical work penned by a government official named Hamd-Allah Mustawfi in 1340/740, when the Big Chill had faded from memory.44 Mustawfi mentions only twelve Iranian cotton-producing areas, and of those twelve, all but three are located either in southern Iran or in the balmy Caspian lowlands. More important, the locales he mentions are mostly villages, not cities, which indicates local consumption rather than a major export trade in cotton textiles. Major cities like Isfahan, Qazvin, Nishapur, Marv, Bukhara, Samarqand, and Rayy that had dominated the cotton industry prior to the year 1000/390 are no longer mentioned as producing areas. Moreover, these cities are not named as cotton centers in Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo’s narrative of an embassy to the court of Timur in the years 1403–1406/805–808.45 His observations on cottons imported to Sultaniyeh, Timur’s capital in northwestern Iran, specify Shiraz, Yazd, and Khurasan as producing areas: two southern cities and one general northeastern province.

The southward shift in cotton growing hints at climate change having lingering effects. However, it is hard to determine whether cold weather in and of itself brought devastation to the cotton planters of the north. Fluctuations in the Siberian High, a winter phenomenon, probably did not diminish the heat of summer or shorten the growing season to less than the five months needed for cotton plants to mature. To be sure, the cotton plant is sensitive to cold, but the greatest sensitivity is at the time of planting. Seeds do not germinate properly if the soil temperature falls below 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Without thermometers, Iran’s cotton farmers may well have occasionally sown their crops too early after a severe winter. An agricultural almanac from Yemen, where Iran’s cotton culture probably originated, matches crop activities to specific times of year, suggesting that farmers relied more on time-honored tradition than on technical calculation in determining the best date for planting.46 However, as experienced men of the soil, Iran’s cotton farmers probably learned from these mistakes and by trial and error adapted their practices to the chillier temperatures.

The greater impact of the cold, and the one signaled by the famine reports, must have been on winter crops, notably the staple grains that sustained both man and beast.47 The plummeting rate of taxation on wheat and barley discussed in the previous chapter indicates that pressure on food resources had already begun by the beginning of the tenth/fourth century, in apparent response to the exuberant urban growth and rural–urban migration of that period.48 If this analysis is sound, then the effect of the Big Chill on cotton may have been more indirect than direct. Reduced harvests caused by cold weather or rural insecurity would have only added to an already existing pressure on farmers to convert cotton fields into wheat fields.

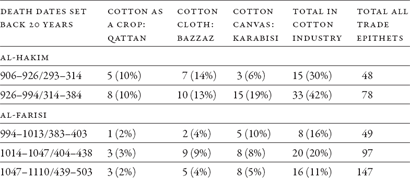

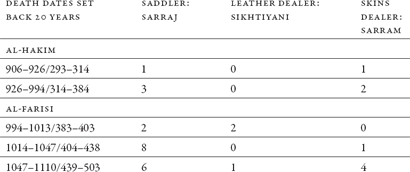

Another factor may also have contributed to lower cotton production: waning prestige as a fabric and loss of the luxury market to silk. The tabulation of occupational names borne by ulama in five different cities (see table 2.1) revealed that the number of cotton growers roughly equaled the number of cotton cloth merchants in four Iranian cities, whereas the ratio in Baghdad was one cotton farmer to every five cotton cloth dealers. Excluded from table 2.1, however, was the occupational information from the most extensive Iranian biographical dictionary dealing specifically with the eleventh/fifth century, ʿAbd al-Ghafir al-Farisi’s Kitab al-Siyaq li Taʾrikh Naisabur.49 Al-Farisi’s work continued the compilation of al-Hakim al-Naisaburi, whose work was used for table 2.1. Like al-Hakim, al-Farisi divided his biographies into chronological categories. His first chronological category contains the biographies of people who died between roughly 1014/405 and 1033/425. These individuals lived most of their lives before the Big Chill set in, so we will set the death-date limits back by twenty years to approximate the time when their occupational epithets may have signified an active involvement with the economy. This makes the boundary dates for Period 1 994–1013/383–403. The limiting dates for Period 2 and Period 3, with the same twenty-year setback, are 1014–1047/404–438 and 1047–1110/439–503, respectively. It is with the individuals included in these two later periods that evidence of a change in the cotton industry becomes apparent.

The decline of the cotton industry as a prestige occupation shows clearly in table 3.1. Roughly one third of the fourth-/tenth-century occupational epithets contained in al-Hakim’s compilation relate to cotton growing and the production of cotton cloth. This drops by half, to an average of 15 percent in the three chronological divisions of al-Farisi’s work, with the lowest percentage being in Period 3. Decline in the industry as a whole becomes even more striking if we exclude the trade in karbas, a sturdy, heavy-duty fabric that seems to have become a Nishapur specialty inasmuch as the name Karabisi rarely appears elsewhere in Iran. Without karbas, cotton sinks from 25 percent of all epithets to 8 percent, a drop of two thirds. If one looks specifically at cotton growers, the falloff is even greater than two thirds, going from 10 percent in al-Hakim to under 3 percent in al-Farisi.

Though the number totals shown in table 3.1 are all so small as to make percentage calculations precarious, some corroboration of cotton’s decline can be gleaned from information about other trades. The leather industry, as portrayed in table 3.2, offers an instructive comparison. The numbers here are so small as to make percentage comparisons truly meaningless, but the overall trend from the fourth/tenth to the fifth/eleventh century is suggestive. The last two time periods of al-Hakim’s work and the first time period of al-Farisi’s cover the century preceding the migration of large numbers of Turkoman nomads into Khurasan. Over those 110 years, eleven members of Nishapur’s religious elite bore names pertaining to the leather industry. However, during the eleventh/fifth century, comprising Period 2 and Period 3 of al-Farisi’s work, the number of leather merchants totals twenty, almost double the tenth-/fourth-century rate. It is hard to avoid the suspicion that a growing number of Nishapur’s scholar-merchants found profit in marketing the skins produced by the extensive flocks of sheep and goats herded by the nomadic newcomers to their region. And it is similarly plausible that the decline in cotton, whether caused by weather, rural insecurity, or changes in demand, was somewhat counterbalanced by the rise of leather.

TABLE 3.1 Occupational names in Nishapur’s cotton industry

Professional names associated with fiber commodities imported along the Silk Road (Farraʾ, meaning “furrier”; Ibrisimi, meaning “silk merchant”; and Labbad, meaning “felt dealer”) similarly indicate a movement away from cotton. One furrier and one silk importer appear in Period 1 of al-Farisi, whereas four of the former and one of the latter show up in Period 2, along with one felt dealer. Two more silk importers are registered in Period 3. The reappearance of these Silk Road commodities, which are almost totally unrepresented among the occupational names of Nishapur’s ulama between the middle ninth/third and late tenth/fourth century,50 suggests a reinvigoration of trans-Asian caravan trade. This matter will be pursued further in the next chapter.

TABLE 3.2 Occupational names in Nishapur’s leather industry

Quantitative indicators, especially those based on small number totals, need to be tested against other sorts of evidence. What other observations might support an argument for cotton losing status or commercial prominence in the eleventh/fifth century? Anecdotes are sometimes helpful. Bayhaqi relates the following story in his chronicle of the year 1031/422:

The next day, Tuesday, the Grand Vizier came to the court, had an audience with the Amir and then came to the Divan. A prayer rug of turquoise-colored satin brocade had been spread out near his usual prominent place…. He sent for an inkstand, which they set down, and also for a quire of paper and a lightweight scroll, of the kind that they bring along and set down for viziers. He set to work and wrote there: “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. Praise be to God the lord of the worlds, and blessings upon His Messenger, the Chosen One, Muhammad, and all his house. God is my sufficiency, and how excellent a guardian is He! O God, help me to do what You desire and what is pleasing to You, through Your mercy, O most merciful of those who show mercy! Let there be given out to the poor and destitute, by way of thanks to God, the Lord of the Two Worlds, 10,000 dirhams of silver coinage, 10,000 dirhams worth of bread, 5,000 dirhams worth of meat, and 10,000 cubits’ lengths of [karbas].51

This story from shortly before the Seljuq takeover makes it clear that cotton is not in short supply, at least in the government store houses. The Grand Vizier himself, however, sits on silk brocade, and the cotton he distributes to the poor is heavy-duty stuff, not fine fabric. Karbas is obviously the sort of cotton that was most available in Nishapur.

Visual evidence is also valuable. In the preceding chapter I proposed that the growth of the cotton industry in the ninth/third century was stimulated in part by a desire of the Muslim Arabs and of the non-Arab Iranian converts to Islam to make themselves visibly distinguishable from non-Muslims in the public arena. Wearing silk brocade garments by the Sasanid elite was recognized as a non-Muslim practice and consequently prohibited in the hadith of Muhammad that were being assiduously collected and transmitted in Iran. By the end of the tenth/fourth century, however, silk garments, and silk brocade in particular, no longer stirred strong religious opposition. Thenceforth, plain white cotton cloth continued to be the preferred garb only of the ulama, and the military and governing elites felt more and more comfortable with the Sasanid-style luxury fabrics that they had never truly abandoned.

The evidence for this change in taste is diverse but consistent. With respect to the ulama, the Adab al-imlaʾwaʾl-istimlaʾ of ʿAbd al-Karim al-Samʿani, a work on the etiquette of teaching hadith by a Khurasani scholar who died in 1167/562, is unequivocal. Under the prescriptive heading “Let [the hadith reciter] dress in white garments,” he quotes the Messenger of God as saying about white garments: “Your living bodies wear them, your corpses are wrapped in them; truly they are the best of your garments.”52

At a more general level, we may recall the tenth-/fourth-century trend in Nishapuri pottery mentioned in the preceding chapter, to wit, the flagging popularity of slip-painted ware, the plain white ceramic dishes with ornate Arabic calligraphy, and the growing popularity of buff ware. Though most specimens of buff ware do not feature human figures, those that do closely mirror the designs on Sasanid gold and silver vessels, the characteristic luxury products of the Iranian aristocracy. During the Seljuq period both styles disappear, being replaced by blue wares of various sorts and by painted wares that take up feasting and warrior themes from their buff ware precursors. The stark Arabic calligraphy on a plain white background has no successor.

The onomastic data from which I projected the course of Iranian conversion to Islam in my 1975 book Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period pointed to the late ninth/third century as the beginning of the climax period (i.e., end of the “late majority” phase) in the growth of Iran’s Muslim community (see figure 1.4).53 I have now been persuaded by the observations of constructive critics that this data base underrepresented rural areas and that the climax period was probably not reached until some time in the tenth/fourth century. Nevertheless, regardless of its precise chronology, the climax period was still a time when many of those members of the landowning elite who had not become prisoners of war during the original Arab conquests, and subsequently converted to Islam to escape slavery, finally gave in to an unstoppable trend and switched their communal identification from Zoroastrian (or Christian) to Muslim. For these high-status individuals of the Late Majority period, the Muslim clothing style sanctioned by hadith may have had little appeal. Just as they enjoyed listening to the pre-Islamic Iranian legends that were being collected into the Shahnameh or “Book of Kings” by the end of the tenth/fourth century, they preferred the clothing styles of the Sasanid period, both for apparel and as designs on pottery. With Arab caliphal power supplanted by more localized Iranian political regimes, and the permanence of Islam as the religion of Iran no longer in doubt, they saw little reason to dress like Arabs. Indeed, a desire to distinguish themselves from Arabs may have become as common as the desire to look and act like Arabs had been among the earliest generations of Iranian converts.

The Seljuq period of the eleventh/fifth and twelfth/sixth centuries provides abundant visual evidence—pottery, figurines, miniature paintings—of silk brocade being the preferred clothing fabric of the governing elite. This does not mean, however, that tiraz ceased to be made for incorporation into royal presentation garments. Not only do the occupational names Tirazi and Mutarriz continue to appear throughout the eleventh century, but Bayhaqi indicates in his description of arrangements made for a subordinate ruler in the year 1030/421 that embroidering the name of a ruler on tiraz had become a formal symbol of political legitimacy:

[A further condition is] that our brother should act as our deputy, in such a way that our own name is proclaimed first from the pulpits in the towns, and the formal intercessory prayers at the Friday sermon (khutba) [are] pronounced in our name at those places and then afterwards in his name. With the minting of dirhams and dinars, and the official embroidery on luxury garments (tiraz-e jama), they are likewise to write our name first and then his.54

However, the Seljuq pictorial evidence reveals that the tiraz embroidery was now worn around the upper arm of a brocade garment, rather than being the sole ornamentation on a length of plain or striped cloth (fig. 3.3). What had once amounted to the government’s religious endorsement of the cotton industry had become simply a vehicle for affirming the authority of the ruler.

The following conclusions will help summarize and draw together the various threads of argument presented in this chapter:

1. Because of unusually cold winter temperatures influenced by the Siberian High, Iran’s climate suffered a two-decades-long chill starting in 920/307, and then sank into a period of severe winter cold and accompanying drought in the early eleventh/fifth century that seems to have continued into the fourth decade of the twelfth/sixth century.

2. Cotton underwent a decline in production during the cold period of the eleventh/fifth century but had already passed its peak of popularity as a distinctively Muslim clothing fabric by the early tenth/fourth century.

3. Religious scholars dealt more often in leather, fur, felt, and imported Chinese silk, the latter three Silk Road commodities, as their involvement in the cotton industry declined. But their own personal clothing preference remained plain white cotton.

4. The cotton industry that revived after the return of warmer temperatures centered primarily in southern Iran, with the northern cities that had been central to the early Islamic cotton boom no longer involved.

FIGURE 3.3. Tiraz worn on upper arm in Seljuq period. (By permission of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

In mustering the evidence on which these conclusions are based, we have avoided the question of how the migration of the Turkic people known as the Oghuz (Ghuzz) or Turkomans, and the building of the Seljuq empire on the basis of their manpower, fits into these climatic and economic changes. That will be the topic of the next chapter.