This chapter discusses the roots of Gestalt psychology and presents the work of some of the more prominent early Gestalt theorists and the influence of that work on psychology as a whole. Gestalt psychology was another product of psychologists working in Germany during the early 20th century that was then imported and further developed in the United States. The early roots of Gestalt psychology began outside of psychology in the disciplines of philosophy and the natural sciences. Immanuel Kant’s (1724–1804) idea that phenomenological experiences are not reducible to an elemental state, Edmund Husserl’s (1838–1916) proposal of the existence of two new types of sensation, space form and time form, and Christian von Ehrenfels’ (1859–1932) development of the concept of Gestaltqualitaten (or form qualities), are described herein as providing the groundwork upon which Gestalt psychology was built.

The research of Max Wertheimer (1880–1943) is discussed as the first evidence of research within psychology employing Gestalt concepts. His research into the subject of apparent movement, a phenomenon Wertheimer called phi phenomenon, is discussed. He introduced the concept of isomorphism, and the Gestalt Principles of Perceptual Organization.

Two psychologists, Kurt Koffka (1886–1941) and Wolfgang Köhler (1887–1967), collaborated with Wertheimer in his initial research into the phi phenomenon and became, along with Wertheimer, the premier researchers and theorists on Gestalt psychology. The high degree of their influence on Gestalt psychology is evident from the nickname earned by the threesome—the Gestalt Triumvirate.

Each of these three prominent figures in psychology played a slightly different role in Gestalt psychology’s development. Wertheimer was the acknowledged founder and inspirational leader, Kurt Koffka popularized Gestalt psychology and was influential in its spread beyond Germany’s borders to America’s shores. Wolfgang Köhler rounded out this productive threesome as Gestalt psychology’s primary theorist and researcher. He expanded the application of Gestalt ideas from the area of perception to learning research in his influential work with apes, described in his text The Mentality of Apes (1925). Some of the concepts Köhler developed from this research include insight learning, and Umweg (or detour) problems.

Kurt Lewin (1890–1947) is another influential Gestalt psychologist discussed in this chapter. Some of Lewin’s contributions include his development of field theory in which he incorporated the concept of the life space. Lewin also conducted influential research on the impact of different leadership styles, authoritarian and democratic, on child development, as well as what he called “action research,” in which he explored such issues as leadership and group problem solving in an industrial setting.

Other researchers have contributed to the development and expansion of Gestalt psychology and this chapter concludes with a discussion of some of their works, including Kurt Goldstein’s (1878–1965) work with brain damaged World War I veterans, Karl Duncker’s (1903–1940) work on problem solving providing the basis for our understanding of the concept of functional fixedness, and Hedwig von Restorff’s (1906–1962) memory research. Frederick S. Perls (1893–1970) constructed psychotherapeutic approach that included some of the concepts employed in Gestalt psychology. However, Perls work is not considered by many in the field as a true extension of Gestalt psychology.

When you finish studying this chapter, you will be prepared to:

- Discuss the early roots of Gestalt psychology in philosophy and the natural sciences

- Define and describe the following concepts: elementism, phenomenology, Gestaltqualitaten, space form/time form

- Discuss the significance of Max Wertheimer’s research on phi phenomenon

- Describe some of the Gestalt principles of perceptual organization

- Discuss the different roles played by Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler in the early development of Gestalt psychology

- Describe the differences between insight learning and trial-and-error learning

- Discuss Kurt Lewin’s contributions, including: field theory, action research, and his work on leadership styles and prejudice

- Define functional fixedness and the Von Restorff Effect

- Describe the general principles of Gestalt therapy

American psychology began, in large measure, as a European import. However, once the seeds of European psychology were planted in American soil this import, fertilized by American ambition and cross-pollinated with an indigenous spirit both utilitarian and pioneering, began to grow in ways that brought American psychology farther away from its European roots. While American psychology was evolving and changing, European psychology itself did not remain stagnant and Germany was one of the intellectual centers of this evolving European psychology during the early years of the 20th century.

Often acknowledged as the birthplace of the scientific psychology that found its way to American shores, German involvement in the growth and development of psychology did not end with the pivotal works of Wilhelm Wundt at the University of Leipzig. Another later contribution to psychology that in many ways was a deep reflection of the German psyche was the development of Gestalt psychology, which, ironically, began as a revolution against Wundtian voluntarism and Titchenerian structuralism.

At the root of this revolution were Gestalt psychologists’ objections to the Wundtian focus on elementism, “the thesis that all psychological facts … consist of unrelated inert atoms and that almost the only factors which combine these atoms and thus introduce action are associations” (Köhler, 1959, p. 728). In its place, the Gestaltists proposed a different thesis, namely, that “the whole is different from the sum of its parts.” Rather than take a Wundtian elementist approach, the Gestalt approach was phenomenological; that is, involving the study of meaningful intact experience not analyzed or reduced to elemental parts. For example, an introspective study of the experience of holding a cup of hot coffee in the morning would be broken down, by a structuralist, into individual component parts, such as the sensation of heat, the texture of the cup’s outer surface, and the visual experience of the color of the coffee and of the mug. No attempt would be made to integrate these experiences. In contrast, a phenomenologist would attempt to study the experience as an integrated whole. For example, the Gestalt approach would include all of the above sensory elements, as well the phenomenological experience of the feelings of refreshment and even of bracing oneself for the day ahead.

At the helm of this phenomenological revolt were three men who came to be known as the Gestalt Triumvirate: Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler. What evolved as a result of their combined efforts was a Gestalt movement that accepted the centrality of some key principles, namely, that psychological awareness cannot be understood simply by breaking experiences down into what appear to be component parts, and that physical and psychological contexts and past experience are important factors in our psychological experiences. While these principles were first identified through studies in visual perception, these and other Gestalt principles were later extended to the areas of problem solving, learning, intra- and interpersonal relationships, and psychotherapy.

Historians have debated the relative importance of the Zeitgeist as opposed to the Great Person as the cause of significant events in history. This debate is particularly relevant to the history of Gestalt psychology. Proponents of “Great Person” historical theories would argue that Max Wertheimer’s insight into perceptual mechanisms in 1910 was fundamental to the development of Gestalt theory and that Gestalt psychology would never have developed without his contribution (Seaman, 1984). However, Zeitgeist theorists would disagree, arguing that at the time of Wertheimer’s insight, many antecedents had already laid significant groundwork making the development of Gestalt theory inevitable (O’Neil & Landauer, 1966).

One of the earliest contributors to the Gestalt approach to studying psychological phenomena was Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), who reasoned that when we first perceive a novel object, we experience mental states that appear to be reducible to the kinds of sensory elements proposed by empiricists and associationists as the building blocks for simple and complex ideas. When past experience with an object is lacking, our experience of that object is reduced to one of raw “elemental” sensations. Kant argued, however, that these phenomenological experiences are not reducible to an elemental state and, furthermore, they are meaningfully organized not through some mechanical associative process, but rather in a priori fashion. The mind, in the process of perceiving, seeks to create a meaningful and organized whole. For Kant, the mind is an active agent coordinating sensations into perceptions. Our experience of the outside world, which Kant called the noumenal world, is filtered by our minds to give us the phenomenal world. The noumenal world consists of “things-in-themselves” and can never be experienced directly, while the phenomenal world is created by the intuitions and conceptions of our minds and is therefore directly experienced. For example, if we were to ski down a hill and hit a tree our experience of the tree would have been described by Kant as noumenal in nature, as it is obtained through our sensory systems and thus is not one of direct knowledge. We do not “become one with the tree”; instead we experience the tree as something separate from the self, an external object actively constructed by the mind from the various sensory phenomena coupled with our own preexisting mental conceptions.

Kant’s concept of perception as an organized unified experience was in opposition to Wundt’s later focus on breaking down consciousness into basic elements as practiced in the Wundtian form of introspection. Psychologist Franz Brentano (1838–1917) favored a more Kantian phenomenological form of introspection with the direct observation of experience as it occurred without further analysis of consciousness into elemental parts.

At the same time that elementism and phenomenology were debated in philosophy and psychology, a similar shift was occurring in the natural sciences, including physics. With the discovery and acceptance of the notion of fields of force, that is, regions or spaces crossed by lines of force, such as electricity or magnetism, these fields allowed the exertion of physical forces at a distance and without direct contact between objects or matter. Accordingly, the notion of elementism was being reconsidered and physicists began to think of the physical world in terms of fields and organic wholes.

Ernst Mach (1838–1916), a professor of physics at the University of Prague, made observations concerning perceptions of space and time in his book The Analysis of Sensations (1885), which later had a significant impact on the Gestalt movement. In this book, Mach proposed the existence of two new types of sensation—space form and time form—and argued that these sensations exist independently of their elements. As an example of a space form, a triangle can be made large or small or can be painted any color while still retaining its basic triangular nature. A time form, such as a melody, can be played on different instruments or in different keys yet the melody remains recognizable and distinct. Similarly, Mach observed that our perception of an object does not change regardless of our spatial orientation to it. You can look at a table from the front, from the side, or from above, without changing your unified perception of it as a table.

Christian von Ehrenfels expanded on Mach’s ideas, and, in 1890, published a critique of Wundt in which he noted Wundt’s failure to include what Ehrenfels considered to be a key element of consciousness in addition to sensations, images, and feelings. Ehrenfels dubbed these elements of consciousness Gestaltqualitaten (form qualities) and described them as qualities of experience that cannot be explained in terms of associations of elementary sensations. Ehrenfels considered these form qualities to be new elements created by the mind as it operated on sensory elements, and, therefore, these Gestaltqualitaten are phenomenological as opposed to noumenal in nature. Ehrenfels, like Mach, used a musical melody as an example of such Gestaltqualitaten. According to Ehrenfels, a melody is more than individual notes, and thus can be transposed to different keys or played on different instruments while remaining recognizable. The melody has form quality (Gestaltqualitaten) even when the expression of the melody varies across different musical instruments.

Philosopher Edmund Husserl also played a role in laying the groundwork for Gestalt psychology. While working at the lab of G. E. Müller in Göttingen, Husserl and his contemporaries expanded on an idea popularized by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) in his most important work, The Phenomenology of Mind. According to Husserl, phenomenology is the scientific examination of the data of conscious experience. Although his understanding of phenomenology in fact closely resembled William James’ conception of psychology, Husserl did not consider phenomenology as a type of psychology but rather as a separate science altogether (Thorne & Henley, 1997). For Husserl, phenomenology and psychology could be of mutual benefit in that phenomenology offered a methodology for analyzing the data of consciousness and a structure with which to guide such an analysis. In turn, psychology could provide new discoveries and collect the data about the nature of conscious experience that could aid in refining phenomenology (Thorne & Henley, 1997).

Born in Prague to a family of intellectuals and artists, Wertheimer attended local schools until the age of 18 at which time he attended the University of Prague. He was a multitalented young man, gifted in mathematics, philosophy, literature, and music. Although he started at the university as a law major, Wertheimer soon changed his major to philosophy and attended lectures by the aforementioned Christian von Ehrenfels. Later, Wertheimer studied philosophy and psychology at the University of Berlin as a student of Carl Stumpf (1848–1936) and then earned his doctoral degree in 1904 at the University of Würzburg under the direction of Oswald Külpe (1862–1915).

Between 1904 and 1910, Wertheimer worked at the Universities of Prague, Vienna, and Berlin. His fateful revelation that sparked the formal development of Gestalt psychology came to him while on a vacation trip from Vienna to the German Rhineland. As the story goes, while riding on a train Wertheimer came to a sudden and dramatic realization concerning the perception of apparent movement (the phenomenon in which the perception of movement is experienced when no actual physical movement has taken place, e.g., the perception of movement experienced when watching a videotape or an IMAX movie projected upon a stationary screen). Wertheimer’s inspiration was that this perceived movement must mean that perception does not necessarily have a one-to-one correspondence with sensory stimulation as assumed by the structuralists. Instead, Wertheimer proposed that perceptions have properties that are not predictable based on the analysis of elemental sensations that comprise them, and that, indeed, the whole of perception may be different from the sum of its sensory parts!

Eager to test his hypothesis, Wertheimer abandoned both the train and his vacation plans! When the train stopped in Frankfurt, Germany, Wertheimer left to purchase a stroboscope—an early precursor of the motion picture camera that allowed still images to be projected on a screen in a time sequence giving the figures in the image the compelling and unmistakable appearance of movement. The stroboscope was a popular toy at the time; in fact, Wertheimer purchased his from a toy store in Frankfurt. In his experiments using the stroboscope, Wertheimer did what no one had thought to do before, namely, to ask the question: Why does apparent movement occur? Many people had used the stroboscope before Wertheimer and seen the same apparent movement, yet none had thought to inquire systematically regarding the conditions that give rise to apparent movement. After experimenting with the toy stroboscope in his hotel room, Wertheimer went to the Frankfurt Academy (which later became the University of Frankfurt) where he could conduct more extensive research on the phenomenon of apparent movement.

While researching his hypothesis at Frankfurt, Wertheimer recruited the assistance of two other former graduates of the University of Berlin, Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Köhler, both of whom were then working in Frankfurt, and the Gestalt Triumvirate was born. Using Koffka, Köhler, and Koffka’s wife, Mira, as subjects, Wertheimer conducted a series of experiments. Wertheimer selected the tachistoscope over the stroboscope for his experiments because it afforded him the ability to control selectively individual features of a visual stimulus while holding other factors constant. Using the tachistoscope, which was a device that flashed lights on and off for brief intervals, Wertheimer was able to project light through two narrow slits, one vertical and the other tilted 20° to 30° from the vertical. If the light was projected first through one slit and then the other with a relatively long time interval between projections (an inter-stimulus interval, ISI, greater than 200 milliseconds), subjects saw two discrete successive lights appearing first at one slit and then at the other. When the ISI was shortened (to less than 50 milliseconds), the subjects reported seeing two discrete lights shining continuously. When a moderate ISI was utilized (approximately 60 milliseconds), the subjects reported the perception of apparent movement, specifically, the subjects saw a single line of light which moved back and forth from one slit to the other. In his 1912 paper titled “Experimental Studies on the Seeing of Motion,” Wertheimer gave this perceived movement the name phi phenomenon. Wertheimer reasoned that phi phenomenon existed just as perceived or experienced and was not reducible to sensory elements compounded by consciousness. In this same paper, Wertheimer was also the first of the three original Gestaltists to describe the concept of isomorphism (which literally means identical shape or form). This principle assumes a direct correspondence between brain processes and mental experiences. This is not to say that brain processes and perception are identical in form. Gestalt psychologists illustrate the concept of isomorphism using the analogy of a map. The relationship between neural processes and corresponding perceptions is similar to that of a map and the region it depicts. Although the map is not a literal recreation of the countryside, we are able to equate features (such as lakes, rivers, and mountains) on the map with corresponding features in the landscape.

Wertheimer remained at the University of Frankfurt until 1916 and during World War I became a German army captain conducting research for the military on sound localization, which led to the later invention of an early type of sonar. Between 1916 and 1929, Wertheimer reestablished his working relationship with Koffka and Köhler while a Privatdozent (the approximate German equivalent of a postdoctoral fellow) at the University of Berlin. While at the University of Berlin, the threesome established the journal Psychologische Forschung (Psychological Research), which provided the primary publication forum for the developing Gestalt movement.

Wertheimer’s career as a psychologist was unfortunately hampered by two key factors, namely, his Jewish heritage and his own perfectionist tendencies. The anti-Semitic atmosphere in Germany at the time made appointment to a full professorship an unlikely achievement for Wertheimer, particularly given the fact that budgetary decisions and professorial appointments at the 21 universities in the German Empire were strongly controlled by educational and financial officials of the German government (Ash, 1998). Wertheimer’s career was also hampered by his lack of publications. A noted perfectionist, Wertheimer apparently found it very difficult to release manuscripts for publication (Thorne & Henley, 1997, p. 377).

Despite this overdue acknowledgment of his research contributions and abilities, Wertheimer found the growing anti-Semitic influence of the Nazi regime increasingly intolerable and finally left Germany in 1933 to seek refuge in the United States. Along with a group of scholars from various fields seeking refuge from Nazi Germany, Wertheimer came to work at the “University in Exile” (later known as the New School for Social Research) in New York City. This institute was founded to create a haven for academic freedom with a mission “to follow the truth wherever it leads, regardless of personal consequences” (Hothersall, 1995, p. 230). During the 1920s and 1930s the New School was responsible for rescuing over 170 scholars, scientists, and their families from fascist Europe.

After completing his initial studies on the subject of apparent movement, Wertheimer expanded his research into perceptual organization, and, in 1923, published a paper summarizing his position that we perceive all objects in much the same manner in which we perceive apparent motion, namely, as unified wholes and not as clusters of mechanically or passively associated elemental sensations. Contrary to the associationists, the Gestalt scientists proposed that the brain functions as a dynamic system in which all elements present in a given stimulus and its context at a given time interact with each other. Gestalt organizational mechanisms aid in organizing this dynamic system, and are triggered in some cases by stimulus features and in others as inherent neural processes. Elements that are similar or close together tend to be processed in combination while dissimilar elements or elements that are far apart are not. On the basis of research into this premise, Wertheimer delineated several of the basic principles summarized in Figure 11.1 by which the brain organizes sensory elements.

Wertheimer’s early contributions to Gestalt theory were heavily focused in the area of perception, which proved both a blessing and a curse for the developing Gestalt movement. Since Gestalt psychology began as a revolt against Wundt and the structuralists with their use of introspection and focus upon perception, it was necessary for proponents of Gestalt psychology to focus also on perception to gain acceptance through the direct refutation of Wundtian introspective methodology. This early focus, however, also meant that Gestalt psychology was unfairly categorized as dealing only with perception.

After immigrating to the United States, Wertheimer remained at the New School for Social Research until his death in 1943. His American colleagues’ recognition of his significant research is evident from their invitation to him to join the prestigious Society of Experimental Psychologists in 1936.

A great deal of Wertheimer’s research in the United States was focused on his interest in education. In addition to his collaboration with John Dewey (1859–1952) on a radio

Figure 11.1 Gestalt Principles of Perceptual Organization

program, Wertheimer was involved in writing a book on productive thinking in which he sought to expand the scope of Gestalt psychology by applying Gestalt principles of learning to creative thinking in humans. Written as a series of case studies, Productive Thinking (1982/1945) included cases involving children solving simple geometric problems as well as interviews with Wertheimer’s close friend Albert Einstein concerning the more complex thought processes that led Einstein to the development of his famous theory of relativity. In writing these cases, Wertheimer found evidence supporting his theory that learning and problem solving proceed in a top-down or deductive fashion from perception of the whole problem downward to its parts. This approach contradicted the prevailing model, namely, Thorndike’s trial-and-error learning in which the whole problem is not necessarily evident to the solver and thus problem solving must proceed from the bottom-up through inductive reasoning. Although Productive Thinking became Wertheimer’s best-known work, he never knew of its impact, as he died of a coronary embolism on October 12, 1943, in New Rochelle, New York (two years before the book’s publication).

Each of the three members of the Gestalt Triumvirate played a slightly different role in the development of Gestalt psychology. Wertheimer is considered the founder and inspirational leader of the Gestalt movement with his program of research into the significance of phi phenomenon and the discovery of organizational principles that operate for perception and learning. However, because of his limited publications, Wertheimer was unable to function as the movement’s popularizer, a role that belonged to Kurt Koffka.

Kurt Koffka was born and educated in Berlin and earned his PhD there in 1909 as a student of Carl Stumpf. In addition to his studies in Berlin, Koffka also spent one year at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland where he developed his strong fluency in English, a skill that later served him well in his efforts to spread Gestalt psychology beyond German borders. Koffka was already working at the University of Frankfurt when Wertheimer arrived in 1910 and invited Koffka to participate as a subject in his research on the phi phenomenon.

Koffka left Frankfurt in 1911 to take a position at the University of Giessen. Putting his English fluency to the test, Koffka then traveled to the United States where he was a visiting professor at Cornell University from 1924 to 1925, and two years later at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Eventually, he accepted a position at Smith College in Holyoke, Massachusetts, where he remained until his death in 1941.

While at the University of Giessen, Koffka wrote an article for the American journal Psychological Bulletin, which introduced American psychologists to the new Gestalt psychology that was taking shape in Germany. Unfortunately, his article, titled “Perception: An Introduction to Gestalt-Theorie” (1935), may have reinforced the misconception that Gestalt psychology focused exclusively on perception (particularly visual perception) and that it had marginal, if any, relevance for other areas such as learning or developmental psychology, which were of great interest to American psychologists and the public as well.

In fact, the scope of Gestalt psychology was far broader than simply the systematic study of visual perception. The primary Gestalt concern was a search to identify a priori or innate mechanisms that might serve to organize and direct all mental experiences including learning, thinking, and feeling, in addition to perceptual experience. As Gestalt psychology’s most prolific writer, Koffka made great strides, after the publication of his 1922 Psychological Bulletin article, in expanding awareness and understanding of the breadth of Gestalt psychology. His major works to that end included a book on child psychology from the Gestalt perspective, The Growth of the Mind (1924) and his most ambitious work, Principles of Gestalt Psychology (1935). In the latter work, which Koffka dedicated to Wertheimer and Köhler, he sought to apply Gestalt psychology systematically to diverse areas such as perception, learning and memory, social psychology, and personality. Although Koffka intended the text for a lay audience, it never achieved the level of popularity he hoped for and, according to Henle (1987), “was probably read only by professional psychologists.” (p. 14).

While Koffka was working to popularize Gestalt psychology both in Germany and in the United States, the third member of the triumvirate, Wolfgang Köhler, was functioning as Gestalt psychology’s primary theorist and researcher.

Born in Reval, Estonia, Köhler grew up in northern Germany. Like Wertheimer and Koffka, Köhler attended the University of Berlin, earning his PhD in 1909 under the direction of Carl Stumpf. Interestingly, although Stumpf directed the early academic careers of all three members of the Gestalt Triumvirate, none of the three attributed any influence on Stumpf’s part to their later development of Gestalt psychology. Indeed, Stumpf himself denied having any influence on the Gestalt school (Thorne & Henley, 1997, p. 376).

In 1913, Köhler’s career took an interesting turn when he accepted the invitation of the Prussian Academy of Science to head an anthropoid research station on Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa. Six months after Köhler’s arrival on the island, World War I began and he was reportedly unable to leave the island. A controversial theory proposed by psychologist Ronald Ley (1990), and challenged by historians and Gestalt psychologists alike, suggests that Köhler’s assignment on Tenerife involved more than the supervision of anthropoid research and that Köhler was also engaged in espionage activities for the German government. Ley (1990), based on archival research and interviews, charged that Köhler concealed a radio transmitter on the top floor of his home, which he used to broadcast information to the German navy concerning allied naval activities. Ley (1990) published a highly readable account of his search for information about Köhler’s alleged espionage activities titled A Whisper of Espionage; however, this account builds a case that is primarily based on circumstantial evidence and Ley was unable to find a “smoking gun.”

Köhler spent seven years at the research station studying the behavior of chimpanzees assisted by his first wife, Thekla Köhler. The product of that research was his 1917 publication of Intelligenz prufunge an Menschenaffen (Intelligence Tests with Anthropoid Apes), which was published in English in 1925 as The Mentality of Apes (Köhler, 1976/1925). The work became a classic text in psychology.

Just as Wertheimer (1982/1945) challenged trial-and-error learning in his Productive Thinking, Köhler raised his own challenges in his research studies described in The Mentality of Apes. Thorndike’s theory of trial-and-error learning was based on the premise that an animal makes a specific response that is either rewarded or not rewarded and those rewards serve to strengthen the bond between a stimulus and a response. Learning, according to Thorndike, proceeds in a trial-and-error fashion and the subject eventually learns to prefer responses that most reliably lead to a reward. Thorndike formed his theory on the basis of research using animals in puzzle boxes. One of Köhler’s main arguments against trial-and-error learning was that the puzzle boxes utilized in Thorndike’s experiments made it difficult for the animals to see the whole problem or situation, forcing them to rely on random activity and trial-and-error learning to solve the problem.

Köhler reasoned that this problem situation was artificial and instead tried to create a problem situation for his chimpanzees in which the animals were able to see all of the problem elements but not necessarily the sequence or structure of elements that would lead to a solution. In order to solve the problem, the animal would need to restructure the perceptual field in some way. Put simply, the animal would need to see first the Gestalt, or the relationship between the elements of the situation, that would then yield a solution. Thereafter, the execution of that solution would proceed as a smooth pattern of actions rather than in a discontinuous and extended trial-and-error fashion.

For example, in one study a piece of fruit was placed outside of a cage just beyond the chimpanzee’s reach. If a stick was placed near the bars of the cage in front of the fruit it would be easy for the animal to perceive the relationship between the stick and the fruit and the animal would readily use the stick as a tool to bring the fruit within reach. However, if the field were rearranged so that the stick was placed at the back of the cage, the animal would then need to restructure the perceptual field in order to solve the problem. In both cases, awareness of the solution of the problem preceded the execution of the solution plainly revealing that learning and problem solving may be more fruitfully cast as cognitive rather than solely behavioral phenomena. Köhler’s work is an early expression of the cognitive movement that swept through all areas of psychology beginning in the late 1950s, and that continues to the present moment.

On the basis of these and similar studies using a variety of problem situations, Köhler derived the concept of insight learning to describe the apparently spontaneous apprehension or understanding of the relationship between stimulus elements in a problem. The animals appeared to make an insightful discovery or to experience a kind of “aha moment,” which led to a sudden behavioral change that resulted in accomplishing the target task. Köhler concluded that insight learning involved certain characteristics including the fact that it often occurred suddenly, there were no partial solutions to a problem (it was either solved completely or not at all), and that learning did not depend on reinforcement. Unlike Thorndike’s trial-and-error learning, reward provided an incentive for learning but learning was not dependent upon this reinforcement. Later research by Birch (1945) indicates that the boundary between insight learning and trial-and-error learning may not be as clearly defined as Köhler originally thought. Instead, in order for insight to occur, subjects must have at least acquired experience and/or skill in one aspect of the problem’s solution.

Köhler also created tasks involving what he termed Umweg or detour problems. In an Umweg problem situation, the goal is visible but cannot be reached directly so that the animal must make a detour, initially traveling away from a goal in order to obtain it.

In 1920, Köhler returned to Germany where his career progressed rapidly, due in part to the critical acclaim of the high level of scholarship evident in his second book Static and Stationary Physical Gestalts (1920).

Köhler, the exact opposite of the warm and friendly Max Wertheimer, appeared cold and aloof and apparently experienced some interpersonal difficulties. In the mid-1920s he divorced his wife, marrying his second wife, Lili Köhler, a young Swedish student. After his remarriage, Köhler apparently had little contact with the four children from his first marriage. In addition, his students were quick to note his development of a tremor in his hands, which became noticeably worse whenever Köhler was stressed or annoyed. Indeed, his laboratory assistants were said to have taken care to observe Köhler closely every morning to see how badly his hands were shaking as a way of gauging his mood (Ley, 1990).

Despite the sometimes negative comparisons with Wertheimer, Köhler had distinct advantages over Wertheimer when it came to the advancement of his career. Köhler, not being Jewish, was not hampered by the anti-Semitic leanings of some German political officials who were in control of professorial appointments. In fact, Köhler may have used his influence to help Wertheimer achieve his Frankfurt professorship. When Köhler later immigrated to the United States, his fluency in English meant that he also did not share Wertheimer’s difficulty in adjusting to the language barrier presented by his new professional environment.

Köhler made brief forays across the Atlantic, first as a visiting professor at Clark University in 1925, then as William James Lecturer at Harvard in 1934, and as a visiting professor at the University of Chicago in 1935. Yet each time, Köhler returned to his native Germany. A staunch opponent of Nazi political policy who openly condemned the dismissal of Jewish and anti-Nazi professors, Köhler wrote the last anti-Nazi article published in a German newspaper in 1933. Despite his own fears that his action would lead to his immediate arrest, Köhler was in fact not arrested, possibly due to his high position in German academia and the relative newness and subsequent cautiousness of the Nazi regime. His status, however, became increasingly precarious over time and he finally immigrated permanently to the United States in 1935.

Köhler taught at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania until his retirement in 1958, at which time he moved to New Hampshire where he continued researching and writing at Dartmouth College. The American Psychological Association (APA) honored Köhler with the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award in 1956 and elected him president of APA in 1959.

We have already discussed the origin of Gestalt psychology as a revolt against structuralism. When Gestalt psychologists first made their way to the United States, however, they found themselves operating in a very different environment, one in which Wundtian psychology had already given way to new and different approaches. The behaviorist school presented a new challenge to Gestalt psychology. Again, the issue that concerned proponents of the Gestalt approach was that of reductionistic and elementist qualities that they considered to be equally present in behaviorism and structuralism. Gestalt psychologists were also critical of behaviorism’s total rejection of consciousness as an appropriate subject for scientific psychology. As Koffka argued, it was senseless to develop a psychology devoid of consciousness, as the behaviorists proposed, since that would reduce psychology to little more than a collection of animal research studies. Perhaps one Gestalt psychologist whose work most strongly reflected a move away from atomistic thinking was Kurt Lewin, and through this work he expanded Gestalt psychology far beyond the scope of the first three Gestalt psychologists.

Kurt Lewin was born in Mogilno, in what is now part of Poland, and moved to Berlin in 1905. He was raised in a warm and affectionate middle-class Jewish home and was educated at the universities of Munich, Freiburg, and Berlin, where he completed studies toward his PhD in psychology as a student of Carl Stumpf by 1914. However, Lewin did not actually receive his degree until 1916 due to the outbreak of World War I. While a student at Stumpf’s Berlin Psychological Institute, Lewin was intrigued by the potential of a scientific psychology but found the Wundtian approach in the coursework at Berlin to be both irrelevant and dull (Hothersall, 1995). His goal was to develop a more useful and meaningful psychology.

Lewin distinguished himself as a German soldier during World War I and by the time the war ended he had risen through the ranks from private to officer and was awarded the Iron Cross (one of Germany’s highest military decorations) before being wounded and hospitalized in 1918. After the war, Lewin returned to the University of Berlin where he was welcomed into the ranks of the Gestalt Triumvirate. While at the University of Berlin, Lewin conducted research on association and motivation and began to develop the system for which he later became famous, namely, field theory.

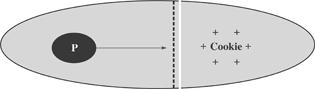

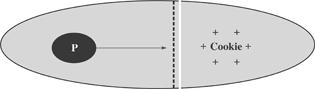

Field theory, as defined by Lewin, borrowed from physics the concept of fields of force to explain behavior within the context of the individual’s total physical and social context. An important concept of Lewin’s field theory was that of the life space, which Lewin presented as a kind of psychological field encompassing all past, present, and future events that affect an individual. Lewin first described this concept in a paper written in 1917, while he was a soldier on furlough, under the title “The War Landscape.” In this paper describing the soldier’s experience of war, Lewin referred to the soldier’s “life space” and used such terms as boundary, direction, and zone which later became central concepts in his field theory. Seeking a mathematical model to represent his concept of the life space, Lewin used a form of geometry called topology to diagram the life space and to represent symbolically at any given moment an individual’s goals and the strategies to achieve them (Figure 11.2).

Lewin incorporated into these “topological maps” arrows or vectors to represent the direction of movement toward a goal, and used valences or weights to quantify the positive or negative value of objects within the life space. For example, objects attractive to the individual would be given a positive valence while objects that were threatening or prevented achievement of a desirable goal carried a negative valence.

In the process of expanding his field theory, Lewin was focused sharply upon applied aspects of Gestalt psychology, more so than the three Gestalt founders. Criticizing the work of industrial engineers and industrial/organizational psychologists, who were at that time heavily focused on time and motion studies and increasing efficiency, Lewin argued that work is something more than producing maximum efficiency. Instead, work has “life value” and should be enriched and humanized (Hothersall, 1995).

Figure 11.2

Life Space Diagram of a Child Desiring an Out-of-Reach Cookie

Pursuing his own life’s work, Lewin was appointed a Privatdozent in 1921 at the University of Berlin where he quickly attracted students with the applied focus of his lectures and research programs. Lewin enjoyed notably close relationships with many of his students, often meeting with them as a group for informal discussions at the Swedish Café across the street from the Berlin Psychological Institute. Included in this group was one young woman who made her own significant contribution to Gestalt psychology, namely, Blyuma Zeigarnik.

During a regular meeting with his students at the Swedish Café, Lewin made an observation that led him to hypothesize that attaining a goal relieves tension. One of the members of the group at the café had called for the bill and their waiter demonstrated exact recall for what everyone had ordered despite the fact that he had not written down any of the orders. Later, Lewin asked the waiter to write down the check again, at which time the waiter responded that he no longer knew what the group had ordered because they had already paid the bill. Lewin reasoned that the unpaid bill (an incomplete task) created psychological tension that was relieved when the bill was paid (and the task completed), creating closure and dissipating the tension, thus erasing a no longer needed memory.

To test Lewin’s theory one of his students, Blyuma Zeigarnik, devised a study in which a large number of subjects were given a variety of cognitive and mechanical tasks. The subjects were allowed to complete some of the tasks but not others and then a few hours elapsed before a recall test was administered. Zeigarnik demonstrated that subjects remembered many more of the incomplete rather than the completed tasks. She concluded that a subject, when given a task, feels the need to complete it, and if prevented from doing so this need for completion creates psychological tension, which in turn facilitates recall of the incomplete task. In a further extension of her original classic study, Zeigarnik hypothesized that if the recall test were delayed for longer than two or three hours the state of tension would be decreased and recall of incomplete tasks would likewise decrease. When she tested subjects after waiting a full 24 hours after the task period, she indeed found that recall of the interrupted tasks was considerably reduced (Köhler, 1947, p. 304). Zeigarnik completed this research as part of her dissertation, published in 1927 under the title “Uber das Behalten von erledigten und unerledigten Handlungen” (“On the Retention of Completed and Uncompleted Tasks”).

Modern television and advertising writers have managed to take clever advantage of this phenomenon, known today as the Zeigarnik Effect. For example, end-of-season cliff-hanger episodes are produced in the hope that tension resulting from lack of closure will compel you to tune in for the next season. Some of you may also recall advertising campaigns in which a series of commercials build on a single story line with each commercial segment ending with a lack of closure, which the advertisers expect will create psychological tension thus compelling viewers to buy the product.

In addition to the young European students who were flocking to learn more about Lewin’s ideas, he also attracted American psychology students studying in Germany. English-speaking psychologists first became acquainted with Lewin’s field theory and research following the publication of an article by one such student. In 1929, J. F. Brown published an article in the Psychological Review titled “The Methods of Kurt Lewin in the Psychology of Action and Affection,” in which Brown outlined Lewin’s theories and described experiments performed by Lewin and some of his students. In this article, Brown (1929) emphasized Lewin’s focus on total acts or Gestalts, and warned psychologists not to dismiss Lewin simply because he had not discovered any absolute psychological laws. Brown likened Lewin’s theories to some of the work done by physicists during the early phase of the development of physics as a science, saying:

Like all pioneers, rather than dictate finished laws, Lewin’s aim has been to indicate directions and open new paths for experiment from which laws must eventually come.

(Brown, 1929, p. 220)

Lewin further developed his American following when he presented a paper titled “The Effects of Environmental Forces” at the Ninth International Congress of Psychology at Yale University in 1929. A particularly powerful feature of the presentation was Lewin’s use of a brief film of an 18-month-old infant that served as an illustration of his concepts. This film, along with Lewin’s use of diagrams and illustrations, allowed him to convey his concepts across a language barrier. As social psychologist Gordon Allport, who attended the lecture, later wrote, “to some American psychologists this ingenious film was decisive in forcing a revision of their own theories of the nature of intellectual behavior and of learning” (Allport, 1968, p. 368).

This presentation along with a later article of Lewin’s, titled “Environmental Forces in Child Behavior and Development,” secured Lewin’s reputation in America. He was invited to spend six months as a visiting professor at Stanford University in California. On his way home, Lewin visited former students in Japan and in Russia giving lectures to psychologists in both countries. Riding the Trans-Siberia Express on the final leg of his trip home, the news came of Hitler’s rise to political power as Chancellor of Germany. While his status as a decorated World War I veteran protected Lewin from Nazi law mandating the removal of Jewish professors, Lewin was not immune from persecution. He resigned from the University of Berlin in 1933 after making a public statement that he had no desire to teach at a university that would not accept his own children as students.

Seeking assistance from his American colleagues, Lewin’s situation came to the attention of Robert Ogden, dean of the School of Education at Cornell University, who presented Lewin’s case to Cornell’s president, Livingston Farrand. A psychologist, Farrand was also chairman of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars and Scientists, established to assist academics who were victims of Nazi persecution (Freeman, 1977). With the support of the Emergency Committee, Ogden offered Lewin a nonrenewable two-year faculty appointment at Cornell in the School of Home Economics rather than the department of psychology.

Lewin left Germany in August 1933, followed by two of his Berlin students, Tamara Dembo and Jerome Frank, who both joined him at Cornell. During his two years at Cornell, Lewin published two major works, A Dynamic Theory of Personality with coauthors Fritz and Grace Heider, and Principles of Topological Psychology with Donald Adams and Karl Zener. Unfortunately, both books received mixed reviews partly because of the difficulty of the material and partly due to a continued lack of familiarity with Lewin’s work on the part of most psychologists in America.

When his two years at Cornell were completed, Lewin attempted to secure financial backing to organize a psychological institute at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem where he hoped to conduct research on Jews immigrating to Palestine as well as on the roots of anti-Semitism and ways to combat it. He was unable to secure adequate funds, and instead found a position at the Child Welfare Research Station at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, Iowa.

Lewin went to work at the Child Welfare Research Station accompanied by his former student Tamara Dembo. Again, Lewin proved to be very popular with the student body and revived his Berlin tradition of informal discussions in what came to be known as “the Iowa, Tuesday-at-Noon, Hot Air Club.” In one important series of experiments, Lewin and his students investigated the effects of authoritarian and democratic leadership styles on the behavior of children (Lippitt, 1939). In this series of experiments, Lewin divided ten-year-old boys into groups who then engaged in various activities while being exposed to different leadership styles, namely, authoritarian and democratic. In the authoritarian group, the adult leader exercised absolute authority over decision making and imposed these decisions on the group, while in the democratic group the adult leader allowed the children to participate in decision making yielding to the desires of the majority. In each of Lewin’s experiments, authoritarian leadership led to increased aggression both in terms of overt acts and more subtle hostility. The boys also evidenced a general preference for democratic leadership. As Lewin later said:

There have been few experiences for me as impressive as seeing the expression on children’s faces during the first day under an autocratic leader. The group that had formerly been friendly, open, cooperative, and full of life, became within a short half-hour a rather apathetic-looking gathering without initiative. The change from autocracy to democracy seemed to take somewhat more time than from democracy to autocracy. Autocracy is imposed on the individual. Democracy he has to learn!

(Lewin, quoted by Marrow, 1969, p. 127)

Beginning in 1939, Lewin returned to an earlier interest, conducting what he called “action research” in an industrial/organizational setting. Using various techniques including group problem-solving sessions, Lewin worked as a consultant both in industry and later during World War II as part of the American war effort (Marrow, 1969). During the war years, Lewin also founded the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, serving as the society’s president from 1942 to 1943. From its inception, the society has been active in conducting research and in producing publications on a variety of social issues including peace, war, poverty, prejudice, and family matters (Perlman, 1986). Many psychologists today consider Kurt Lewin as the founder of social psychology.

As a consequence of working in such varied settings, Lewin realized the restrictive nature of his position in Iowa so he decided to move on. He organized the Research Center for Group Dynamics, which he established on the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). One of the most significant achievements of this research group was the development of the concept of “Training or T groups.” These T groups were designed to develop effective leadership skills, improve communication techniques, and combat prejudice and destructive attitudes. The techniques developed have been widely used in a variety of educational, counseling, industrial, and clinical settings.

Lewin also became involved in a series of studies on prejudice that he conducted as part of a second research institution, the Commission on Community Interrelations (CCI) for the American Jewish Congress, headquartered in New York City. Under Lewin’s leadership, this institute was involved in research that significantly impacted such social problems as racial discrimination in employment and the effects of segregated and integrated housing on racial attitudes. One particular study, which Lewin called “Ways of Handling a Bigot,” used role-playing in a series of vignettes presenting different versions of a single incident. In each case, an actor would express a prejudiced or bigoted opinion, which would be answered differently in each vignette. In one such vignette, the bigoted remark would be unanswered while in the second it would receive a quiet response, and in the third vignette the remark would be met with an emotionally fused and angry reply. When an audience was polled regarding their perception of these different ways of handling a bigot, the calm answer was preferred as the best way to respond to the depicted situation 65% of the time, while 80% of the audience stated that they wanted to see the bigot challenged. Rationality rather than emotionality was preferred as the appropriate mode of handling bigotry suggesting that educational strategies could be deployed to manage major racial problems.

Lewin died of a heart attack on February 1, 1947. Edward Tolman gave a memorial address at that year’s APA convention in which he said:

Freud the clinician and Lewin the experimentalist—these are the two men whose names will stand out before all others in the history of our psychological era. For it is their contrasting but complementary insights which first made psychology a science applicable to real human beings and real human society.

(Marrow, 1969, p. ix)

Even if Gestalt psychology never expanded beyond the efforts of Lewin and the influential threesome of Wertheimer, Koffka, and Köhler, their combined efforts alone would have constituted a significant contribution to psychology as a whole. Although Gestalt psychology began with the efforts of these four influential individuals, it did not end with them as well. Many others have contributed to an expansion of the scope of Gestalt psychology and others have brought ideas from Gestalt psychology into more recent movements such as humanism and cognitive psychology.

For example, Kurt Goldstein (1878–1965) was an editor of Psychologische Forschung as well as a pioneer in clinical neuroscience whose work with brain-damaged veterans of World War I expanded our understanding of the relationship between neurology and behavior within the context of a Gestalt framework (Thorne & Henley, 1997). Karl Duncker (1903–1940) was a student of both Wertheimer and Köhler and followed in their footsteps as a Gestalt psychologist with a particular interest in thinking. His 1945 work on problem solving provided the basis for our current understanding of the concept of functional fixedness, defined as the opposite of creativity or the inability to use objects to attain a goal in ways that differ from the objects’ previously established usage (Thorne & Henley, 1997).

Another Gestalt psychologist who studied under the founders of Gestalt psychology and who followed them to the United States to escape the Nazi regime was Hedwig von Restorff (born in 1901, although the precise date of her death is not known). Her name has become synonymous with the phenomenon she discovered as part of her research, namely, the Von Restorff Effect. Von Restorff was involved in memory research with subjects who were asked to learn lists of nonsense syllables with a three-digit number imbedded in the list. Subjects invariably evidenced better recall for the three-digit number than for any of the syllables. Expanding on the concept of the figure–ground relationship, von Restorff hypothesized that the number provided a sharp figure against the background of nonsense syllables (Baddeley, 1990). This phenomenon, in which any stimulus in an information array stands out in some fashion and is recalled better than any other element in the array, is known as the Von Restorff Effect.

More recently, individuals such as Rudolph Arnheim (1904–2007) and Mary Henle (1913–2007) have continued to identify themselves as Gestalt psychologists and to extend the scope of Gestalt psychology. Rudolph Arnheim has written concerning classical Gestalt topics in such articles as “The Trouble with Wholes and Parts” (1986) and has also tried to dispense with misconceptions of Gestalt psychology to expand the range of applications of Gestalt principles. An area of interest for Arnheim has been visual perception and his works, including Visual Thinking (1969) and Art and Visual Perception (1974), helped develop the fields of the psychology of art and of architecture (Thorne & Henley, 1997).

Mary Henle has been one of the primary historians of Gestalt psychology in addition to her contributions to the Gestalt research enterprise. A Professor Emeritus at the New School for Social Research, Henle has compiled several essay collections and written articles on some of the many contributors to the development of Gestalt psychology. One controversial question that Henle has sought to answer concerns the relationship between Gestalt psychology and a later movement that professed to be an extension of Gestalt psychology, namely, the Gestalt therapy approach developed by Frederick S. Perls.

In his 1951 book Gestalt Therapy (co-authored by Ralph Frank Hefferline and Paul Goodman), Perls first described an approach to psychotherapy that he claimed, in one of his later works, derived its perspective “from a science which is neatly tucked away in our colleges; it comes from an approach called Gestalt psychology” (Perls, 1969, p. 61). In all of his books on his therapeutic approach, Perls made use of terminology and concepts from Gestalt psychology and continued to lay claim to a link with Gestalt psychology; however, he acknowledged that he was never accepted by Gestalt psychologists and admitted to never having actually read any of their books.

In her article analyzing Perls’ claim to a relationship between Gestalt therapy and Gestalt psychology, Mary Henle firmly denied any basis for Perls’ attributions:

What Perls has done has been to take a few terms from Gestalt psychology, stretch their meaning beyond recognition, mix them with notions—often unclear and incompatible—from the depth psychologies, existentialism, and common sense, and he has called the whole mixture gestalt therapy. His work has no substantive relation to scientific Gestalt psychology. To use his own language Fritz Perls has done “his thing,” whatever it is, it is not Gestalt psychology.

(Henle, 1978, p. 31)

Fritz Perls’ “thing,” whether it may rightly be referred to as an extension of Gestalt psychology or not, does make use of basic Gestalt principles in deriving an understanding of the nature of human beings and of behavior, including the Gestalt principles of closure, projection, and figure/ground, conceptualizing behavior as an integrated whole, which is more than a summation of component behaviors, and viewing behavior within the person’s environmental context. Gestalt therapy holds at its core basic assumptions about human nature:

- That a person is, rather than has, emotions, thoughts, and sensations, all of which function in union giving rise to the whole person

- That a person is an integral part of her or his environment

- That a person behaves proactively, not reactively

- That a person is capable of self-awareness, is able to make choices, and is therefore responsible for behavior and capable of self-regulation

- That the fundamental drive for behavior is the need for self-actualization

- That a person is neither intrinsically good nor bad

(Passons, 1975, pp. 12–15)

The goal of Gestalt therapy was to increase self-awareness and to work toward integration of the person into a systemic whole. Metaphorically, it may be said that Gestalt therapy did not, itself, achieve integration with Gestalt psychology as a similar systemic whole.

Gestalt psychology has managed to influence a broad selection of areas within psychology including perception, learning, cognitive psychology, personality, social psychology, and motivation. One of Gestalt psychology’s most significant contributions has been the sustained fostering of interest in conscious experience as legitimate subject matter for psychological study during the years in which the dominance of behaviorism threatened to remove consciousness entirely from the domain of psychology. Without the Gestalt movement as a counterpoint to behaviorism, the current rejuvenated interest in the areas of humanistic and cognitive psychology would have been less likely. In turn, this resurgence of humanism and cognitive psychology has given new relevance to the research of the early Gestalt psychologists such as Wertheimer, Köhler, and Lewin.

Wolfgang Köhler (1959) addressed the question of Gestalt’s legacy or place within psychology in his presidential address to the American Psychological Association. In this address, Köhler traced Gestalt psychology from the work of Wertheimer to the then current work of social psychologists Solomon Asch and Fritz Heider. Köhler proposed that the next step would be the gradual disappearance of competing individual schools of psychology such as Gestalt psychology and behaviorism and the emergence of a single unified psychology. Thorne and Henley (1997) have pointed to modern cognitive-behavioral therapies and the latest advances in cognitive science related to learning theory as evidence that Köhler may have been correct in his prediction as these developments exemplify the combining of disparate areas of psychology.

In the course of the development of Gestalt psychology and through its continued influence in a wide variety of areas within psychology it is possible that Gestalt psychology has come close to approaching the vision for the movement that was summarized by Kurt Koffka:

The hopeless error which the materialists committed was to make an arbitrary discrimination between these three concepts (matter, life, and mind) with regard to their scientific dignity. They accepted one and rejected the two others … whereas each of them may, as a conception, contain as much of the ultimate truth as the others….

I have implied the kind of solution our psychology (will) have to offer. It cannot ignore the mind-body and the life-nature problem, neither can it accept these three realms of being as separated from each other by impassable chasms…. To be truly integrative, we must try to use the contributions of every part for the building of our system.

(Koffka, 1935, pp. 11–12)

Gestalt psychology arose from the dissatisfaction of a rising group of young German psychologists with the elementism characteristic of the ideas of the structuralists who dominated psychology during the early 20th century. This chapter discussed some of the ideas of German philosophers and natural scientists, including Immanuel Kant, Ernst Mach, Christian von Ehrenfels, and Edmund Husserl, that formed the philosophical groundwork from which Gestalt psychology arose. These philosophers and theorists contributed the concepts of fields of force and Gestaltqualitaten.

The work of three key figures in psychology who became known as the Gestalt Triumvirate (Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler) was discussed. We presented Max Wertheimer’s research on phi phenomenon and the Gestalt principles of perceptual organization, Kurt Koffka’s efforts to popularize Gestalt psychology, and Wolfgang Köhler’s influential research on insight learning.

Kurt Lewin’s broad influence brought Gestalt psychology to bear on such diverse areas as social psychology, industrial/organizational psychology, and child development. Some key contributions of Lewin include his development of field theory and T (training) groups and his research on the effects of different leadership styles on child development and his work on prejudice.

Many other individuals have contributed to the expansion of the scope of Gestalt psychology and some of their contributions were also described in this chapter, including, Kurt Goldstein, Karl Duncker, Hedwig von Restorff, Rudolph Arnheim, and Mary Henle. Frederick Perls’ Gestalt therapy was also discussed, since Perls presented his psychotherapeutic technique as having been derived from basic principles of Gestalt psychology.

Discussion Questions

- Was the development of Gestalt psychology more in keeping with the “Great Person” theory or the “Zeitgeist” theory of history and why?

- According to Kant, what is the difference between the “noumenal world” and the “phenomenal world”?

- What effect did anti-Semitism have on Max Wertheimer’s career and why?

- Why did early Gestalt theory focus on the area of perception and what, if any, impact did this focus have on Gestalt psychology’s later development?

- How do Wertheimer’s and Köhler’s theories on learning and problem solving differ from Thorndike’s theories of trial-and-error learning?

- What personal experiences or historical events may have contributed to Lewin’s theories on the impact of leadership styles on childhood development and his research on prejudice?

- What, if any, relationship exists between Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy?