In its broadest sense, the term object relations refers to the process by which the self-structure forms early in life out of our relationships with objects. Objects, in psychoanalytic theory, do not adhere to the traditional definition of an object as an inanimate thing. Instead, an object can be truly anything, that is, while an inanimate thing can be an object, so can a person or even a part of a person. Additionally, objects can be both external and internal to an individual.

The use of the term object originally appeared in Freud’s work to refer to anything toward which an individual directs drives for the purpose of satiation, with drives categorized into two types: libidinal and aggressive. Freud’s drive/structure model includes four basic assumptions relevant to a discussion of objects and object relations:

- The unit of study in psychoanalysis is the individual as a discrete entity.

- The essential aim of the individual is to achieve a state in which the level of stimulation within the individual is as close to zero as possible.

- The origin of all human behavior can be ultimately traced to the demands of drives.

- There is no inherent object; rather, the object is “created” by the individual out of his or her experience of drive satisfaction and frustration.

(Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983)

In reviewing particularly the fourth assumption, it becomes clear that in Freud’s model drives took center stage with object creation occurring as a secondary process. For Freud, objects are created by drives and object relations are therefore a function of drive. Although Freud introduced the use of the word “object,” the full development of a theory of object relations was primarily the accomplishment, not of Freud, but of his followers, in particular Melanie Klein and W. R. D. Fairbairn.

Melanie Klein (1882–1960) published her first psychoanalytic paper in 1919, in which she addressed a gap between psychoanalytic theory and practice. Freud had initially constructed his theory of psychoanalysis on the basis of clinical work with young adult hysterics; however, Freud subsequently expanded psychoanalytic theory into a general theory of psychosexual development. Prior to 1919, no psychoanalyst had attempted to apply psychoanalytic techniques directly to children either to improve their emotional and psychological well-being or to test out Freud’s developmental theories firsthand (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

Klein began to address this gap by applying psychoanalytic principles and techniques to the treatment of children. In the course of her work with children, Klein became increasingly focused on the relationship between the child and the maternal nurturing figure, particularly during the first years of a child’s life. This focus on the mother–child relationship was somewhat tragically ironic given the very troubled relationship between Melanie Klein and her daughter Melitta, also an analyst, who maintained that her brother Hans, killed during a mountain climbing accident in 1934, had actually committed suicide because of his poor relationship with their mother (Grosskurth, 1986).

As Klein began developing object relations theory she maintained that her work was not a contradiction but rather an expansion of Freudian orthodoxy. However, she did deviate from Freud, particularly regarding the relative impact upon development of the psyche of internal forces versus such external forces as the individual’s social milieu. Freud’s early description of objects de-emphasized the role of environment in development of the psyche. Freud centered the struggles and dramas of relationship within each individual in contrast to the usual location of human relating in the social realm of interaction between individuals (Cushman, 1992).

Like Freud, Klein presented the major components of the psyche as originating in the individual organism and developing in a maturational sequence, at which time they begin to be modified and transformed through interactions between the individual and others in his or her environment (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). This process relied heavily on Klein’s concept of “phantasy.” Klein’s use and understanding of “phantasy” was unique enough that subsequent object relations theorists have used the unconventional spelling “phantasy” to differentiate Klein’s use of the term from theories including a more conventional concept of fantasy. For Klein, phantasy constitutes the basic substance of all mental processes. Klein emphasized the child’s unconscious phantasies about objects and gave little weight to the significance of environmental experience in determining an infant’s basic outlook other than to the nature of her or his unconscious phantasy.

In a series of papers, Klein depicted a child’s mental life as filled with increasingly complex phantasies, particularly concerning primary objects, such as the mother, and often specifically focused on the mother’s “insides.” The child desires to possess the goodness that she or he imagines is contained, for example, in the mother’s body. The child imagines a similar interior to his or her own body, containing good and bad substances and objects, and is preoccupied with the need to grasp or obtain “good” substances and objects and to suppress the action of “bad” objects and substances.

In imagining this internal world of objects the child internalizes or introjects whole or partial objects and a complex set of internalized object relations are established, with phantasies and anxieties concerning the state of one’s internal object world forming the basis for one’s behavior, moods, and sense of self (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). In this sense, phantasy serves as the vehicle for introjection and the creation of internal objects. Klein theorized that as early as between 6 and 12 months of age infants are able to internalize whole objects with the first whole object usually being the mother in keeping with Klein’s emphasis on the particular intensity of the maternal–infant relationship.

While developing further her basic theory of object relations, Klein elaborated several key concepts that remain fundamental to current psychotherapeutic theory and technique. One such key concept is that of splitting, which emerged in Klein’s 1946 paper, “Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms” (Hughes, 1989), and was tightly intertwined with Klein’s concept of phantasy. In the course of interacting with external objects in the environment, whole objects are internalized, which in turn form the basis of psychic life. A conflict arises within the individual psyche, however, when it attempts to reconcile the conflicting good and bad aspects of a whole object and these good and bad aspects are split off and internalized as separate good and bad internal objects which cannot be amalgamated (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

While Klein retained Freud’s overall drive/structure model and presented Freudian instincts as the motivational force for object relations, she also understood instincts as being related to others’ responses. This modification was the first transition from a pure drive/structure model to more of a relational/structural model of the human psyche.

Critics of Klein have often presented her theories as highly speculative and too heavily focused on descriptions of primitive fantasy material. In addition, many critics point out major shifts in basic principles and areas of emphases over the course of Klein’s career as a theorist as well as the unique forcefulness in Klein’s writing style. This blend of focus on fantasy material, her theories’ internal inconsistencies, and her tendency toward overgeneralizations and hyperbole have resulted in a body of work which is also extremely rich, complex, and, unfortunately, only loosely organized (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). This loosely organized quality of Klein’s work has contributed to the frequent crediting of the development of a systematic and comprehensive object relations theory to someone other than Klein, namely, W. R. D. Fairbairn.

Fairbairn (1889–1964), who was from Edinburgh, Scotland, and therefore maintained some physical distance from the influence of Melanie Klein at the British Psychoanalytic Society, is frequently acknowledged as a central figure in the development of object relations theory. His accomplishments toward that end may hinge, in part, on his willingness to make a more radical departure from Freudian theory than did Klein.

Fairbairn first introduced the essential elements of his theory of object relations in his paper “Endopsychic Structure Considered in Terms of Object-Relationships,” first published in 1944. One of the biggest points of departure Fairbairn made from Freud’s theories concerned the nature of libido. For Freud, libido was primarily pleasure-seeking, whereas for Fairbairn libido was object-seeking. By taking this stance, Fairbairn actually questioned two separate but related Freudian claims, that first, the need for gratification of sexual and aggressive drives is the primary motivation for all behavior; and, second, our interest in and relation to objects is based primarily on the object’s role in serving this need (Eagle & Wolitzky, 1992).

One of Fairbairn’s most important contributions to object relations theory was his shift in emphasis away from Freud’s focus on the id and toward the ego. In Freudian theory, the ego was regarded as a relatively superficial modification of the id, designed specifically for the purpose of impulse control and adaptation to social reality demands. In contrast, Fairbairn envisioned the ego at the core of the psyche as the real self. By elevating the status of the ego and de-emphasizing the id, instinctual drives that reside in the id lost their importance and human behavior and the human psyche became instead an effect of ego-functioning (Meissner, 2000). Healthy development thus requires an intact and integrated ego.

One of Fairbairn’s greatest criticisms of classic psychoanalytic theory was his perception of the failure of psychoanalysts to apply their clinical experience with patients to even their most basic theoretical principles.

Fairbairn theorized object relations as containing a number of basic points that differentiate object relations from classical psychoanalysis:

- The ego is conceived of as whole or total at birth, becoming split and losing integrity only as a result of early bad experiences in relationships with objects, particularly the mother object.

- Libido is regarded as a primary life drive and the energy source of the ego in its drive for relatedness with good objects.

- Aggression is a natural defensive reaction to frustration of libidinal drive and not a separate instinct.

- The psyche evolves as ego unity is lost and a pattern of ego-splitting and the formation of internal ego–object relations ensue.

In developing his object relations theory Fairbairn collided with adherents of Melanie Klein as well as orthodox Freudians. In particular, Fairbairn’s conception of the original primitive ego was very different from Klein’s. Klein presented the primitive original ego as split either at the very beginning of life due to opposing attachment and death instincts or relatively early in infancy. According to Fairbairn, however, there exists at the outset a “whole, pristine, unitary ego” that only splits as a consequence of environmental failure. As a consequence of this particular aspect of his theory, Fairbairn is frequently criticized for a perceived overemphasis on the role of parents and their early interactions with the infant as the root of all later difficulties in living. But even his critics acknowledge Fairbairn’s work as providing a starting point for the accomplishments of later theorists, including Bowlby’s work on attachment, Kernberg’s work in the treatment of severe personality disorders, and Mitchell’s relational theory. Fairbairn’s work has been increasingly influential in research on infant development, child abuse, and the borderline, schizoid, and narcissistic disorders. One of Fairbairn’s most influential written works was Psychoanalytic Studies of the Personality (1953).

Donald Woods Winnicott (1896–1971) was born into a prosperous middle-class family in Plymouth, England. Winnicott studied medicine in Cambridge, completed his medical studies in 1920 and in 1923 he married and took a position as a physician at the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital in London.

A contemporary of W. R. D. Fairbairn, Winnicott was an early enthusiastic supporter of Freud and was heavily influenced by Freud’s work. In 1923, Winnicott’s involvement with psychoanalysis became deeper and more personal when he entered into analysis with James Strachey, who had himself been analyzed by Freud.

In 1927, Winnicott was accepted for training by the British Psychoanalytical Society, qualifying as an adult analyst in 1934 and as a child analyst in 1935. He was still working at the children’s hospital, and commented later that “at that time no other analyst was also a pediatrician so for two or three decades I was an isolated phenomenon” (Jacobs, 1995). His work in treating psychologically disturbed children and working with their mothers gave Winnicott the basis upon which he would later build his most original theories.

Over six million people, many of them urban working-class citizens, were evacuated from England’s cities to the countryside during World War II, particularly following the blitz of September 1940. In many cases, these evacuations resulted in the separation of children from their parents; fathers were frequently off serving in the military while mothers were required to leave the home and seek employment either for financial reasons or in support of the war effort. Despite these evacuations, nearly 8,000 children were killed in Great Britain (Holman, 1995).

To give some perspective to the evacuations contrast it with the stress and anxiety experienced by children in the United States, particularly in New York City, following the tragic events resulting from terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001.

Many of Great Britain’s child evacuees were unwelcome in the private middle-class homes that were required to accept them. Many children brought with them psychological problems, and social work services throughout the country set up programs to meet the needs of these children. In cases where home placements were unavailable or unsuccessful, these children were placed in hostels or group homes established for the purpose of providing specialized care. Clare Britton (Winnicott) worked with these evacuated children in Oxfordshire and it was there that she met D. W. Winnicott, who came on a weekly basis as a consultant to work with the children in these hostels.

The Winnicotts’ work in Oxfordshire became well known across Great Britain; their paper on the Oxfordshire program was the lead article in the premier issue of Human Relations, an interdisciplinary journal published by the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations (Winnicott & Britton, 1947). The Winnicotts were also influential in the institution of significant changes in the structure of child welfare services in Great Britain. Subsequent to the experience of many families with the trauma of child–family separation during World War II, and particularly following the 1945 well-publicized death of a foster child, the British Home Office established the Curtis Committee in 1946 to investigate and report on the state of child welfare services. The committee interviewed 229 witnesses including John Bowlby, Susan Isaacs, and D. W. and Clare Winnicott. Their final published assessment, known as “The Curtis Report,” was well received and the majority of their recommendations were implemented as part of the Children Act of 1948 (Kanter, 2000).

From his experience at Paddington Green Children’s Hospital, Winnicott became convinced of the importance of the behavior and state of mind of the mother (or other primary caretaker) in the healthy psychological development of the child. A particularly well-known quote of Winnicott’s concerns the importance of relationship in the development of self during infancy:

There is no such thing as a baby—meaning that if you set out to describe a baby, you will find you are describing a baby and someone. A baby cannot exist alone, but is essentially part of a relationship.

(Winnicott, 1964, p. 88)

This notion of the infant, not simply as a discrete, individually functioning unit but rather in terms of its relationship to others, is a key feature of Winnicott’s work and differentiated his theories from those of both the Kleinian and the Freudian camps. Winnicott believed that it is not instinctual satisfaction that causes an infant to begin to feel real and that life is worth living, but rather relational processes that lead to these feelings.

One of Winnicott’s most influential written works was his paper “Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena” (1953). Winnicott later expanded upon the ideas presented in this paper in his book Playing and Reality, published in 1971, the year of his death. One of the key concepts presented in these works was that of a transitional object, described by Winnicott as an object used by the child as a bridge between subjective and objective reality. The transitional object is used by the child to control anxiety when threatened and in early development of play.

Another key concept of Winnicott’s is that of the “holding environment.” While Winnicott argued that the self was developed as a consequence of the parent (usually maternal)–child relationship, he also described a conflict that arises between the child’s need for intimacy and the urge for separation or individuation (Cushman, 1992). According to Winnicott, the maternal figure plays a critical role in infant development by providing a “holding environment” that psychologically contains and protects the child and within which the infant can begin to integrate the “bits and pieces” of her/his experience into a more cohesive sense of self. In a psychotherapeutic relationship, the therapist is also seen as an actively holding and nurturing figure—not just in fantasy but also in reality. Winnicott used the term good enough mother to refer to any ordinary woman whose maternal instincts are not deflected by personal disability or by faulty “expert” advice and who is capable of providing the above described holding environment.

In the years following World War II, Winnicott was president of the British Psychoanalytical Society for two terms, a member of study groups convened by UNESCO and the World Health Organization (WHO), and he continued to lecture widely and produce publications while simultaneously maintaining a private practice as a pediatrician. Winnicott also continued his work at the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital into the 1960s. He died in 1971 following a series of heart attacks.

Heinz Hartmann (1894–1970) was another prominent figure in the psychoanalytic community whose work diverged from that of Freud. Hartmann is particularly known for his theories on “ego psychology.” Another branch of psychoanalysis, ego psychology, so called because of its focus upon ego structures and functions, was primarily developed by Anna Freud and her followers and became the primary American form of psychoanalysis from the 1940s to the 1970s. Ego psychologists translated, simplified, and operationally defined many Freudian constructs and encouraged experimental investigation of psychoanalytic hypotheses (Steele, 1985).

Born in Vienna, Hartmann was an intellectual aristocrat and the product of a long family tradition of scientific and academic achievement. An ancestor from his father’s side of the family was noted astronomer and historiographer Adolf Gans (1541–1613), who was a personal acquaintance of Johannes Kepler (1571–1630). Hartmann’s father, Ludo Hart-mann, was a famous historian and professor of history at the University of Vienna as well as Austrian ambassador to Germany after World War I (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

Hartmann began work at the Vienna Institute of Psychiatry and Neurology in 1920. He moved to the United States in 1935 to become director and later president of the Psychoanalytic Institute of New York. He also served as president of the International Psychoanalytical Association from 1951 to 1957.

Hartmann’s ultimate goal was to develop psychoanalysis into a “general psychology” rather than a theory limited by a focus on psychopathology, as evidenced by his statement that “in order fully to grasp neurosis and its etiology, we have to understand the etiology of health, too” (Hartmann, 1951, p. 145). Hartmann approached psychological development as a problem of evolution and adaptation to reality. According to Hartmann, actions (from infancy onward) are always undertaken in an attempt to adapt to one’s physical and psychological realities; his reality principle took precedence over Freud’s pleasure principle. Instead of Freud’s conceptualization of fantasy as regressive and pathological, Hartmann believed fantasy furthered an individual’s relation to reality. His psychotherapeutic strategy shifted from an interest in the examination of intrapsychic conflict and the defensive functions of the ego to an examination of the ego’s adaptive functions to an average environment. Environmental failure became the key causal element in psychopathology.

Hartmann’s most important and influential publication was his work, Ego Psychology and the Problem of Adaptation (1958/1939), in which he introduced the idea of the ego as autonomous from the instinctual drives of the id. He also emphasized the central role of the ego in the adaptation of the psyche to the individual’s environment and the relevance of cognitive functions in learning about reality for the purpose of ego adaptation.

Throughout his career he remained committed to Freud’s drive/structure model and, while he was aware of the many radical alternatives to drive theory proposed in the 1930s and 1940s by such theorists as Harry Stack Sullivan, Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and others, he was unwilling to abandon drive as the conceptual center of psychoanalysis. Recognizing the validity, however, of some of their criticisms of strict orthodox Freudianism, Hartmann sought to create a blended theory incorporating their modifications within the framework of a drive/structure model. For this reason, he has been referred to as an accommodation theorist or a mixed model theorist. The end result of his efforts was to open psychoanalysis to possibilities never before considered (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

Margaret Schonberger Mahler (1897–1985) was born in a small district on the border of western Hungary. Educated in Hungary and Germany, she studied medicine, eventually specializing in pediatrics, and gained a reputation for her work with severely disturbed and psychotic children. While working in Heidelberg, Germany, Mahler became more deeply interested in psychology and trained as a psychoanalyst. Her area of interest was in gaining a better understanding of early childhood development both in normal as well as disturbed children (The Margaret S. Mahler Psychiatric Research Foundation, 2002).

Mahler emigrated from Europe first to London and later to New York where she continued her work in psychoanalysis. She established a therapeutic nursery at the Masters Children’s Center in New York City, which later expanded to include a mother–child center for neighborhood families. The center provided a setting in which Mahler and her colleagues could further their observational research into child development.

Mahler, like Hartmann, followed an accommodation approach in her modification of orthodox Freudian theory. In her work, she presented the problem of development and adaptation as a coming to terms with the human environment. She presented successful development as a process she called “separation–individuation,” which involved movement through different levels of relatedness, beginning with a state of embeddedness within a symbiotic child–mother dyad to the achievement of a stable individual identity. The various stages of development delineated and described by Mahler are summarized in Table 13.1.

From the beginning of her interest in psychology until her death in 1985, Margaret Mahler conducted research, wrote, taught, and supervised analysts in training in New York and Philadelphia. A prolific author, her publications continue to serve as a resource for clinicians and researchers (The Margaret S. Mahler Psychiatric Research Foundation, 2002).

Heinz Kohut (1913–1981) was born in Vienna, the only child of a concert pianist who had married the daughter of a wealthy merchant family, the Lampls. His father ended his music career during World War I when he served as a soldier on the Russian Front and after the war he went on to become a successful businessman.

Kohut attended the Doblinger Gymnasium where he excelled academically. In addition, his family hired a young university student who tutored him from the time Kohut was eight until he reached the age of 14. Kohut entered university at the age of 19 and at the same time had his first exposure to psychoanalysis when he entered therapy with psychoanalyst August Aichhorn. Kohut studied medicine at the University of Vienna, graduating

in 1938, at the age of 24. Kohut followed Freud into exile when he fled Vienna for England in 1939, and served as a medical intern. He then traveled to the United States, landing on his new country’s shores, despite his family’s wealth, with only $25 to his name. By the time he was 31, Kohut had advanced to the position of assistant professor in neurology and psychiatry. He also began training as a psychoanalyst and, upon completion of his studies in 1949, he joined the staff of the Chicago Institute of Psychoanalysis.

Table 13.1 Mahler’s Stages of Infant Development

|

Stages and Ages

|

Primary Features

|

| Normal Autism: 0–2 months |

Infant unaware of the mother. |

| Normal Symbiosis: 1–4 months |

Awareness of the need to depend on another for satisfaction. |

| Differentiation: 4–10 months |

Child begins to realize that there is a difference between him/herself and the primary parenting figure. |

| Early Practicing: 10–18 months |

“The height of the child’s love affair with the world.” (G reenacre, 1957) |

| Rapproachement: 18–36 months |

Continued exploration by the child of the environment, combined with a growing fear of loss of the object and the love of the object. Child begins to realize that love object is a separate individual, and surrenders her/his feelings of infantile grandiosity. |

| Object Constancy: 3 years on |

Internalization of a constant inner image of the mother. |

|

Mother is clearly perceived as a separate person in the outside world, and at the same time has an existence in the internal representational world of the child. The ability to tolerate delayed gratification signifies the beginning of ego (only possible after mother is internalized). |

Kohut began to find his own voice and used it to express what he and many fellow psychoanalysts were beginning to perceive as problems in orthodox Freudian psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic theory and practice were reaching a crisis point; many orthodox beliefs were being called into question as anachronistic and/or overly focused on personal insight at the cost of empathy, overly obsessed with guilt, and overly valuing autonomy and individualism.

In the late 1960s, Kohut began to focus on issues in the treatment of severely disturbed patients who had previously been considered unsuitable for psychoanalytic technique. It became clear to Kohut at this time that psychoanalysis needed revision because many of the disorders commonly diagnosed by Freud and his contemporaries, such as hysteria, were no longer prevalent due to changes in society and family. New disorders such as borderline and narcissistic personality disorders were emerging which did not easily lend themselves to treatment using orthodox Freudian methodology. For this reason, Kohut did not see himself as diverging from orthodox Freudian psychoanalysis, but rather as attempting to modernize it and to keep it sociohistorically relevant. He presented himself as the “new voice of psychoanalysis.”

Beginning in the mid-1960s, Kohut experienced a burst of creativity lasting for the next 15 years of his life and resulting in a theoretical model that Kohut called his “psychology of the self.” His reformulation of psychoanalysis is frequently regarded as the pivotal event transforming the field from the Freudian emphasis on the drive/structure model into a true “relational psychoanalysis.” At the center of Kohut’s self psychology lies his concept of the self, to which he ascribes functions previously attributed to the id, ego, and superego in the classical Freudian drive/structure model. The self is no longer a representation or by-product of ego activity but is itself an active agent.

For Kohut, the infant is born into an empathic and responsive human environment, and relatedness with others is as essential for the infant’s psychological survival as oxygen is for physical survival (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). The infant’s self cannot stand alone—it requires the participation of others to provide a sense of structure. The early self emerges at the point where “the baby’s innate potentialities and the [parents] expectations with regard to the baby converge” (Kohut, 1977, p. 99). The emergent infant self, however, is weak and amorphous and cannot stand alone as it requires the participation of others, termed by Kohut as “self-objects,” to provide a sense of cohesion, constancy, and resilience (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

Empathy was a critical process in Kohut’s approach to psychotherapy. The therapeutic psychoanalytic process involves creation of an empathic interpersonal field in which the participation of the analyst is essential, in contrast to the traditional psychotherapeutic approach in which the therapist is a neutral observer interpreting drive and defense processes within the patient.

Heinz Kohut was not the only psychoanalyst to consider social and historical factors in terms of their relevance to psychopathology and to psychoanalytic theory. However, while Kohut broadened the scope of psychoanalytic theory to make room for such considerations, the primary aim of his self-psychology was the better understanding of individual development and not, necessarily, a better understanding of societal development; Kohut was a psychoanalyst first and foremost and not a social psychologist. In contrast, Erich Fromm stands as someone who, while he identified himself primarily as a psychoanalyst, was also a social psychologist.

Erich Pinchas Fromm (1900–1980) was born in Frankfurt, Germany, the only child of a wine trader named Naphtali Fromm and his wife Rosa. In his book Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx and Freud (1962), Fromm described a couple of events from his childhood that deeply impacted him and affected the nature and scope of his later work as a theorist. The first event occurred when he was 12 years old. At that time Fromm was quite fascinated by an attractive young woman who was a friend of the Fromm family; this fascination stemmed in part from the fact that she was the first painter he had ever met as well as from her physical beauty, which appealed to the adolescent male Fromm.

Fromm was profoundly impacted by his experiences as a young teenager in Germany during World War I. His early exposure to occasional evidence of racial hatred toward himself and his family as Jews in Germany had not prepared him for what he described as the “hysteria of hate against the British which swept throughout Germany” in the years surrounding World War I. Again, Fromm found himself asking “How is it possible?” “How is it possible that millions of men continue to stay in the trenches, to kill innocent men of other nations, and to be killed and thus to cause the deepest pain to parents, wives, friends?” (Fromm, 1962, p. 8). By the time the war ended in 1918, Fromm was obsessed by the need to understand how war is possible, and with a questioning and critically appraising attitude toward individual and social phenomena.

It was with this same questioning and appraising attitude that Fromm first encountered and studied the teachings of two individuals who deeply influenced his work in psychology: Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx. The extent of their influence is suggested by the subtitle of Fromm’s intellectual autobiography Beyond the Chains of Illusion. As a young student at the University of Frankfurt, his preoccupation with the problem of understanding the seeming irrationality of human mass behavior naturally drew him to the study of psychology, philosophy, and sociology.

In 1929, Erich Fromm co-founded the South German Institute for Psychoanalysis in Frankfurt, together with Karl Landauer, Frieda Fromm-Reichmann, and Heinrich Meng. In 1930, Fromm became a member of the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, which held sway over the fields of both psychoanalysis and social psychology. At the same time, he completed his training as a psychoanalyst at the Psychoanalytic Institute in Berlin.

Fromm’s gradual divergence from Freud stemmed from Fromm’s greater focus on political and cultural issues and their impact on individual personality. His interest in the effects of culture brought him into the intellectual orbit of like-minded figures in the psychoanalytic community, including Karen Horney, with whom Fromm engaged in a brief but intense love affair in addition to their intellectual collaboration, and psychiatrist Harry Stack Sullivan.

In 1934, Fromm fled Germany and immigrated to the United States, settling in New York City where he worked at the Institute for Social Research. In 1941, Fromm began teaching at the New School for Social Research in New York where he remained for several years and also published one of his most well-known books, Escape From Freedom. In addition to his work at the New School for Social Research, Fromm also held part-time positions and guest lectured at various institutions such as Bennington College in Vermont and Yale University in Connecticut.

In the 1950s, Fromm and his second wife, Henny Gurland, moved to Mexico City where Fromm was very instrumental in the development of psychotherapy in Mexico. He served as Professor Extraordinary at the Medical Faculty of the National Autonomous University of Mexico where he taught Mexico’s first course in psychoanalysis, and in 1956 founded the Mexican Psychoanalytic Society. In 1963, he also opened the Mexican Psychoanalytical Institute.

During the 1960s, while he maintained his primary residence in Mexico, Fromm continued lecturing in the United States. He also became increasingly involved in politics, participating in a peace conference in Moscow in 1962 and becoming actively involved in protests against the Vietnam War. Fromm remained professionally active throughout the 1970s, although his health became progressively fragile and he moved to Tessin, Switzerland, where he found the climate and atmosphere more restful. He suffered a series of heart attacks over a period of several years and finally died of a heart attack on March 18, 1980.

Fromm based his synthetic Freudian-Marxian model on the premise that the inner life of each individual draws its content from the cultural and historical context in which he or she lives (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983). We each institute and perpetuate social values and processes as a means of individually solving the problems posed by the human condition. Despite the breadth of Fromm’s contributions to psychoanalysis and social psychology, his dual emphasis on psychodynamics and sociohistorical factors contributed to the frequent dismissal of his importance by critics who view him more as a social philosopher than as a psychoanalytic theorist (Greenberg & Mitchell, 1983).

In his 1970’s book, The Crisis of Psychoanalysis, Fromm believed the major flaw in Freud’s psychoanalytic theory was Freud’s failure to place his observations of human behavior within the larger context of history and culture. For Fromm, Freud’s key discovery was humankind’s capacity for distorting the reality of one’s experience to conform to socially established norms.

According to Fromm, Freud’s error was in focusing on the sexual and aggressive content and extrapolating from such content a motivational theory for all human behavior thereby ignoring the process and structure of self-deception. In effect, Freud shifted the focus of analysis away from the relationship between the individual and the world of other people to a focus on forces arising within the individual. Fromm saw a potential solution to “Freud’s error” in Marx’s ideas concerning history and cultural transformation. Both Freud and Marx, however, developed theories that were deterministic in their view of human behavior: Freud’s theory postulated that behavior and the individual psyche were largely determined by biology; Marx saw human behavior as determined by society, particularly by economic systems (Boeree, 1997a). In contrast, Fromm allowed for the possibility for people to transcend determinism by centering a great deal of his theory on the idea of freedom, making it the central characteristic of human nature.

According to Fromm, the concept of the individual with unique thoughts, feelings, moral conscience, freedom, and responsibility has evolved over the centuries. Thus, for example, in contrast to the modern individual, a person living during the Middle Ages led a life largely determined by socioeconomic realities. If your father was a peasant, you would grow up to be a peasant; a prince would eventually become a king, all predetermined by the fate of one’s birth. Given this relative lack of freedom, however, life is made easier and simpler because an individual’s life has structure and meaning and there is no need for doubts or soul-searching (Boeree, 1997a). As the modern individual evolved, the consequences of increased individual freedom emerged, such as isolation, alienation, and bewilderment, thus making freedom a difficult challenge. Fromm described three ways, summarized in Table 13.2, in which we seek to escape the difficul-ties and associated pain of freedom through an “escape from freedom”; one’s choice of method of escaping from freedom has a great deal to do with what kind of family one grew up in. Fromm outlined two kinds of family structures lending themselves toward particular choices in method of escape from freedom, namely, symbiotic families and withdrawing families. In a symbiotic family, some members are “swallowed up” by other members so that they fail to develop personalities of their own, for example, the parent “swallows” the child so that the child’s personality becomes a mere reflection of the parent’s wishes. Symbiotic families tend to promote an authoritarian method of escape from freedom. Withdrawing families, the more recently evolved type of family structure, manifest themselves in two ways: parents are either demanding, holding high expectations of their children and maintaining very high, well-defined standards, or parents tend to be overly controlling of their own emotions, presenting a façade of cool indifference. The most common method of escape from freedom in a withdrawing family structure is automaton conformity (see Table 13.2). Fromm expressed concern regarding automaton conformity as he felt that the withdrawing family structure was becoming increasingly prevalent embodied by the modern, shallow, television family (Boeree, 1997a).

Fromm believed we have absorbed our culture so well that it has become unconscious—the social unconscious, to be precise. This “social unconscious” is very different from Jung’s concept of a “collective unconscious.” Fromm believed that the social unconscious could be best understood through an examination of our economic systems.

A number of theorists described thus far in this chapter have focused the bulk of their theorizing on issues relevant to human behavior and human development during the first half of the lifespan from infancy through the early phase of adulthood. Erik Erikson

developed the first detailed model tracing human development beyond these early phases reaching across the continuum of the lifespan.

Table 13.2 Fromm’s Three Methods of “Escape from Freedom”

|

Authoritarianism

|

We avoid freedom by fusing ourselves with others and becoming a part of an authoritarian system. Two ways to approach this are, (1) to submit to the power of others by becoming passive and compliant or (2) to become an authority by applying structure to others. Either way, the individual escapes his or her separate identity. |

|

Destructiveness

|

We escape what is a painful existence by essentially eliminating ourselves: If there is no me, how can anything hurt me? Alternatively, we can respond to personal pain by lashing out at the world: If I destroy the world, how can it hurt me? These approaches lead to destructive behavior (destructive of self or of others): suicide, drug addiction, self-abuse versus crime, terrorism, brutality, humiliation. |

|

Automaton conformity

|

Another means of escape from freedom is to hide in our mass culture. If I look like, talk like, think like everyone else in my society, then I disappear into the crowd. I no longer have to struggle with decisions and I don’t need to either acknowledge my freedom or take personal responsibility for my actions. |

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) was born in Frankfurt, Germany, the son of Danish parents. His father was Protestant and his mother Jewish and the two actually separated prior to his birth. Erikson’s mother, Karla Abrahamsen, lived in Karlsruhe, Germany, raising Erikson as a single mother prior to marrying her son’s pediatrician, Dr. Theodor Homberger, when Erikson was three years old. Erikson attended the Humanistiche Gymnasium in Karlsruhe where unfortunately he was constantly treated as an outsider (Hunt, 1993). He graduated at the age of 18 but was uninterested in pursuing higher education at that time, following instead his interest in art and traveling about the German countryside reading, drawing, and making woodcarvings (Top Biography, 2002). As Erikson himself once said, “I was an artist then, which is European euphemism for a young man with some talent but nowhere to go.”

At first, Erikson had difficulty merging his artistic style with his intellectual efforts, but gradually, with the mentoring of Anna Freud, he was able to use his artistic talent for keen observation in the psychoanalytical observation of children’s play. While in Vienna, Erikson met and married Joan Serson, a Canadian-born, American-trained sociologist with an interest in modern dance and psychoanalysis. She became an English teacher at the school where Erikson worked and also one of his closest professional collaborators.

Erikson became a psychoanalyst after completing training at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute in 1933. By that time fascism was already becoming a concern for anyone with a Jewish heritage, and after considering several options the Eriksons decided to take advantage of an invitation from Hans Sachs, a disciple of Freud, to come to Boston. Erikson was the first child psychoanalyst in the Boston area and he joined the faculty of Harvard Medical School, becoming part of a research team working on personality under the leadership of Henry Murray.

During World War II, Erikson conducted research relevant to the war effort, including studies on submarine habitation and on the interrogation of prisoners of war. He also wrote psychobiographical essays on Adolf Hitler and published Hitler’s Imagery and German Youth (1942). Another, later, psychobiographical work, his book Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence (1969), earned Erikson both a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award, a unique achievement for a psychologist.

Although Erikson was offered a professorship at the University of California at Berkeley his tenure was broken as a result of the activities of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the Committee on Un-American Activities. McCarthyism had infiltrated academia and professors were being forced to sign loyalty oaths establishing that they were anticommunist. Erikson was fired for being one of the few individuals who refused to sign. Although later reinstated, he chose to resign in 1950 in support of his peers who had been fired for the same reason but had not been reinstated to the faculty. Erikson then accepted Robert Knight’s invitation to join him at the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, a center devoted to psychotherapy and research with severely disturbed adolescents and young adults.

From 1960 until his retirement in 1970, Erikson taught as a Professor of Human Development at Harvard University. However, even after his so-called retirement, Erikson undertook his first research efforts in the area of gerontology in collaboration with his wife Joan Erikson, and their colleague, Helen Kivnick, which was published in 1986 as Vital Involvement in Old Age. Erikson’s career finally came to an end when he died at the age of 92 in Harwich, Massachusetts, on May 12, 1994.

Professor Gordon Allport (1897–1967) more than any other theorist played a vital role in bringing the formal study of personality into academic acceptance from out of its previously exclusive focus in the clinical setting. Allport, unlike Freud and many Freudian followers, led a relatively happy and unremarkable childhood. Both Gordon and his brother Floyd Allport pursued the study of psychology at Harvard University. Gordon Allport earned his PhD in psychology from Harvard in 1922.

Allport took time off to travel between his undergraduate and graduate years at Harvard, and visited Sigmund Freud in Vienna. Years later he described this single encounter as traumatic and voiced the opinion that psychoanalysis focused too greatly on unconscious forces and motives and neglected conscious motives (Allport, 1967). Hence, Allport proceeded to develop his own theory of personality that differed dramatically from that of Freud. Allport minimized the role of the unconscious in mentally healthy adults arguing that they instead function in a more rational conscious mode. Allport also disagreed with Freud concerning the impact of childhood experiences on conflicts in adult life and insisted that we are more influenced by the present and by our plans for the future than by our past. Allport also insisted that personality could only be investigated through the study of normal adults and not the study of neurotics.

Allport’s personality theory centered on the concept of motivation. A key concept in his theory is that of functional autonomy or the idea that a motive is not functionally related to any childhood experience and is independent of the original circumstances in which the motive first appeared. Allport envisioned the adult human being as self-determining and independent of childhood experiences. For Allport, motives change over time.

Allport decided to dispense with the common word “self” and substituted instead the word “proprium” taken from the Greek root meaning appropriate. The term proprium, however, never came into popular usage in psychology. For Allport, the “proprium” or self is what belongs to or is appropriate for the individual and this self develops through seven stages from infancy to adolescence. The key element in the course of the development of this self is not the psychosexual issues so important to Freudian theory, but rather social relationships.

A primary area of study for Allport was personality traits, beginning with his doctoral dissertation. He distinguished between traits, which can be shared by any number of individuals, and personal dispositions, which are traits unique to each individual. He further described three different kinds of traits, including:

- Cardinal traits, which define and dominate every aspect of life.

- Central traits, which are more generalized behavioral themes, for example, aggressiveness or sentimentality.

- Secondary traits, which are displayed less frequently and consistently than other traits.

Lastly, Allport contributed significantly to research examining such social issues as prejudice. He received the Gold Medal Award from the American Psychological Foundation and the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award from the American Psychological Association (APA), and also served as a past president of the APA. He remained professionally active until his death in 1967 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Henry Murray (1893–1988) began undergraduate studies at Harvard majoring initially in history. After completing his BA, Murray transferred to Columbia, earning his MD in 1919. Murray then studied embryology at the Rockefeller Institute for four years, followed by further doctoral studies at Cambridge University in England where he completed a PhD in chemistry.

Murray’s interest in psychology was prompted initially by a personal crisis. He had fallen in love with a married woman named Christiana Morgan while he himself was also married. Morgan suggested that Murray seek the advice and counsel of Carl Jung, who at the time was also openly having an affair with a younger woman while maintaining his relationship with his wife and family. Jung advised Murray to follow his example and to openly maintain both relationships, which Murray did for the next 40 years.

This initial contact on a personal level led to Murray’s professional interest in psychology. In 1927, he decided to pursue studies in psychology and returned to the United States to become the assistant to Morton Prince at Harvard’s new psychological clinic (Thorne & Henley, 1997). Murray remained at Harvard for the majority of his career with the exception of a period of time during World War II when he worked for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which is the prototype for today’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

His work in the area of personality led to his development, in collaboration with Christiana Morgan, of the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) in 1935. The TAT consists of 30 pictures depicting ambiguous social situations, and administration of the test typically consists of the presentation of a subset of these pictures to the subject with the instruction that the subject must then create a story about each picture. The story contents are then analyzed for the presence of common themes giving insight into the personality of the subject. This psychodynamic approach to personality assessment is very reminiscent of Freud’s use of dream analysis to reveal unconscious processes. While enthusiastically received at first, TAT subsequently declined in popularity due to the difficulty in developing valid and reliable scoring methods for interpreting results. For many years it was assumed that the TAT was primarily Murray’s work with Christiana Morgan functioning strictly in an assistive role; however, in 1985, Murray himself wrote that Morgan in fact had the main role in developing the test and noted that the original idea came from a woman student in one of his classes (Bronstein, 1988).

Murray’s varied background and his exposure, through Jung, to the ideas of Freud both influenced the nature of Murray’s own theory of human personality, which he called personology. Following the Freudian tradition, Murray’s model stressed the concept of tension reduction as well as the importance of the unconscious and the impact of early childhood experience on adult behavior. Murray also incorporated into his model a somewhat modified version of Freud’s id, ego, and superego (Murray, 1938). His modification to the id involved his inclusion of positive, socially desirable tendencies such as empathy, identification, and love in contrast to Freud’s focusing of the id on more primitive and sexual impulses. While Freud focused on the need for suppression of these dark id impulses, Murray’s system allowed for the need to foster or to express fully the more positive aspects of the id as critical for normal development to occur.

Murray also modified Freud’s concept of the ego, giving the ego a more active role as the conscious organizer of behavior and not simply as the servant of the id. Murray also expanded the sphere of social influences impacting the development of the superego. Freud focused primarily upon parental influence as the key to development of the superego whereas Murray included one’s peer group and exposure to cultural vehicles such as literature and mythology as also influential. Unlike Freud, who felt that the superego was essentially fixed by the age of five, Murray believed that the superego continued to develop across the life span.

Murray’s personality theory differed from Freud’s in that it centered on motivation. One of Murray’s most fundamental contributions to psychology remains his development of a classification of needs to explain motivation. In Murray’s theory, needs, including for example the need for achievement, affiliation, and dominance, involve chemical forces in the brain that organize intellectual and perceptual functioning. Need leads to arousal and increased tension levels in the body, which are then only reduced through satisfaction of the need. Need thus activates behavior, the purpose of which is need satisfaction.

Beginning in the early 1960s a new movement arose within American psychology known as humanistic psychology or the “third force.” Humanistic psychologists emerged in opposition to what were at that time the two most influential theoretical forces in psychology, namely, behaviorism and psychoanalysis. Humanistic psychology was known by the name “third-force psychology” to signify its presence as a third alternative to these two powerful rivals. The basic underlying assumptions separating humanistic psychology from behaviorism and psychoanalysis include:

- An emphasis on conscious (not unconscious) experience.

- A belief in the wholeness of human nature.

- A focus on free will, spontaneity, and the creative power of the individual.

- The study of all factors relevant to the human condition.

The roots of the humanistic movement in psychology can be found in the work of earlier psychologists including Franz Brentano (1838–1917) and William James (1842–1910), both of whom criticized the mechanistic/reductionistic approach to psychology; Oswald Külpe (1862–1915), who demonstrated that not all conscious experience was reducible or explainable in terms of simple stimulus–response relationships; and the Gestalt psychologists, who believed in taking a holistic approach to the study of consciousness. Psychoanalysts such as Adler, Horney, Erikson, and Allport also contributed to the development of the third force by contradicting Freud’s focus on the unconscious and focusing instead on the individual as a conscious being possessing free will and capable of active self-creation and not just passive development in response to external forces. The creative and self-generative aspects of third-force psychology struck a chord with the 1960s American counterculture, expressed primarily by college-age youth.

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) was one of the leading groundbreakers in humanistic psychology. Maslow was born in Brooklyn, New York, and led a rather unhappy childhood. His father, an alcoholic and a womanizer, frequently disappeared for long periods of time and Maslow’s mother was frequently abusive toward Maslow, openly rejecting him and favoring his younger siblings. Maslow never forgave his mother for her treatment of him, and refused to attend her funeral when she died.

As an adolescent, Maslow tried to compensate for feelings of inferiority stemming from his scrawny build and large nose by excelling in athletics. When he failed to succeed as an athlete, however, he turned to academics. Maslow enrolled at the City College of New York (CCNY) where he studied law before becoming interested in psychology. He then transferred to Cornell University where Edward B. Titchener (1867–1927) taught Maslow’s first course in psychology. Maslow found that psychology as presented by Titchener was “awful and bloodless and had nothing to do with people, so I shuddered and turned away from it” (Maslow, as cited in Hoffman, 1988, p. 26). Fortunately, he did not turn away from psychology for very long. In 1928, he married his first cousin, Bertha Goodman, against his parents’ wishes and the couple moved to Wisconsin where Maslow transferred to the University of Wisconsin, earning his BA (1930), his MA (1931), and a PhD in psychology (1934). While at the University of Wisconsin, Maslow worked with Harry Harlow, who was famous for his experiments with rhesus monkeys and attachment behavior.

A year after graduation, Maslow returned to New York to work with E. L. Thorndike at Columbia where Maslow became interested in research on human sexuality, motivation, personality, and clinical psychology. He also began teaching full-time at Brooklyn College. Initially an enthusiastic behaviorist, Maslow became convinced, on the basis of personal experiences including the birth of his children and his experiences in World War II, that behaviorism was too limited to be of relevance to real human issues.

Maslow’s initial attempts to develop humanistically oriented theories within psychology met with resistance from the influential behaviorist establishment. After leaving Brooklyn College, he took a position at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, where he remained from 1951 until 1969. He was elected president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1967 and died of a heart attack on June 8, 1970.

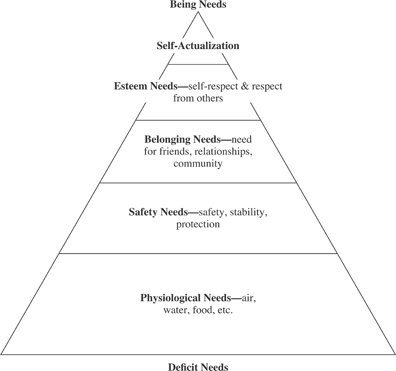

While he was working at Brandeis University, Maslow met Kurt Goldstein, who introduced him to the concept of self-actualization, which is a state of achieving the full development and realization of one’s abilities and potential (Boeree, 1997b). Maslow was convinced that humans have needs beginning with basic physiological and practical needs, and progressing in hierarchical fashion through higher-order levels of need. Needs at any given level within this hierarchy could not be addressed unless lower-level needs had been satisfied. At the apex of this hierarchical structuring of human needs, Maslow believed that humans have a deep need to achieve the state of self-actualization. Perhaps one of Maslow’s most influential and popular contributions was his creation of this hierarchy of human needs (Figure 13.1).

Carl Rogers (1902–1987) was born in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Carl Rogers was an academic achiever even in early childhood and entered school directly into the second grade. When Rogers was 12 years old, the family moved from the suburbs to a rural farm.

Rogers enrolled at the University of Wisconsin as a major in agriculture but later switched his major to religion with the intention of studying for the ministry. He was selected to join nine other students who traveled for six months to Beijing, China, as part of the “World Student Christian Federation Conference.” His experiences in Beijing caused Rogers to begin to doubt some of his most basic religious views and assumptions. His academic career was also interrupted at this time when he was hospitalized for six months for treatment of an ulcer (Boeree, 2002).

After graduating from the University of Wisconsin, Rogers married Helen Elliot and moved to New York City where he began attending the Union Theological Seminary, a famous liberal religious institution (Boeree, 1998). While there he took a seminar titled “Why am I entering the ministry?” and in the course of taking the class, made the decision not to pursue the ministry. He left the seminary to enroll in the clinical psychology program at Columbia University where he earned his PhD in 1931. His decision to make the transition from theology to psychology was in part stimulated by a course Rogers took at Columbia in clinical psychology taught by Leta Stetter Hollingworth (1886–1939). While still enrolled at Columbia, Rogers began clinical work in psychology, first at the Institute of Child Guidance and, later, after completing his Doctor of Education (EdD) from Teachers College, at the Rochester Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. While there Rogers learned about the clinical theories and therapeutic techniques of Otto Rank (1884–1939), a psychoanalyst and disciple of Sigmund Freud.

Rogers then left New York to take a position as a full professor at Ohio State in 1940. While at Ohio State, he published his first book, Counseling and Psychotherapy: Newer Concepts in Practice (1942). In 1945, he went to work at the University of Chicago where he established a counseling center and remained until 1957. While at the University of Chicago, Rogers published his most popular and influential work, Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory (1951), in which he outlined the bulk of his clinical theory (Gendlin, 1988).

Client-centered (or what is now called person-centered) therapy is distinguished by certain qualities or characteristics including an environment in which the therapist provides unconditional positive regard and empathic understanding toward the client as well as a sense of genuineness or authenticity on the part of the therapist. The therapist displays empathic understanding by listening to what the client is trying to communicate and then sharing his or her understanding with the client as a means of validating the client’s communication (Boeree, 2002).

In addition to promoting a very different therapeutic technique as an alternative to psychoanalytic techniques that had previously dominated the clinical setting, Rogers and his colleagues were also instrumental in promoting the idea that psychotherapy could be studied objectively. Rogers was elected president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1946 and in 1956 and, along with Wolfgang Köhler and Kenneth Spence, was selected to receive the first Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award by the American Psychological Association (APA).

Rogers eventually returned to the University of Wisconsin; however, interdepartmental conflicts caused him to become disillusioned with academia and in 1964 he left to take a research position in the private sector in La Jolla, California. Although no longer working in the academic setting, Rogers continued to practice as a clinical psychologist and to write about his clinical theories until his death in 1987.

Rollo May (1909–1994) was born in Ada, Ohio. May’s childhood was marred by his parents’ divorce as well as his sister’s psychotic breakdown. He briefly attended Michigan State but was asked to leave after he became involved with a radical student magazine (Boeree, 1998). May then attended Oberlin College in Ohio, and after graduating from Oberlin he traveled to Greece where he taught English at Anatolia College for three years and also studied briefly with Alfred Adler, a protégé and later defector of Sigmund Freud.

Perhaps coincidentally, May shared Carl Rogers’ early interest in religious studies, and after obtaining his BA from Oberlin College (1930), May earned a divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary (1938) before earning a PhD in clinical psychology granted by Columbia in 1949 (Boeree, 1998). Also like Rogers, May’s academic progress was somewhat slowed due to personal illness, in May’s case, tuberculosis.

May spent three years in a sanatorium for the treatment of tuberculosis and this experience had a significant impact on him as a psychologist. Forced to face the possibility of death at an earlier age than most, he spent many of his hours reading philosophy and religion and was greatly influenced by the writings of Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish religious writer and philosopher who was influential in the existentialist movement (Boeree, 1998). Before undertaking graduate studies at Columbia, May also studied psychoanalysis at the White Institute where he met influential figures in the psychoanalytic community including Harry Stack Sullivan and Erich Fromm.

May’s dissertation had an existentialist orientation as it focused on the meaning of anxiety. He became, over the course of his career, perhaps the most celebrated American existential psychotherapist of his era and he drew heavily on the ideas of existentialist philosophers including Kierkegaard and Heidegger. In 1958, he co-edited the book Existence: A New Dimension in Psychiatry and Psychology with Ernest Angel and Henre Ellenberger, in which the trio introduced existential psychology to the United States. He died in Tiburon, California, in October of 1994.

Existential psychology was heavily influenced by the earlier work of existential philosophers such as Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), and Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). Two themes in existentialism were particularly appealing to humanistic psychologists, namely, subjective meaning rather than “objective” third-person observations of brain and behavior must be the central focus of psychology. Second, humans have free will and thus must take responsibility for their choices.

The formalization of the humanistic movement in psychology was evident in several events: the founding of the Journal of Humanistic Psychology in 1961, the establishment of the American Association for Humanistic Psychology in 1962, and the establishment of the Division of Humanistic Psychology of the American Psychological Association in 1971. Humanistic psychologists sought to promote their theories, methods, and terminology; however, by 1985 even humanistic psychologists were agreeing that while “humanistic psychology was a great experiment … it is basically a failed experiment in that there is no humanistic school of thought in psychology, no theory that would be recognized as a philosophy of science” (Cunningham, 1985, p. 18).