The American Approach

People around the world are becoming more connected and interdependent, exchanging goods and cultural practices, and seeking knowledge to live wholesome and rewarding lives free from fear and the threats of terrorism. Psychology can assist all of us in these pursuits and help us construct a meaningful and sustainable peace.

Psychology as a science seeks knowledge to understand human affective, behavioral, and cognitive systems, while as a profession psychology applies this knowledge to instruct the lives of individuals and groups around the world. Psychology is becoming more and more global and there is subsequent tension between the identification of invariant laws that describe and shape affective, behavioral, and cognitive phenomena. To understand the global and local challenges and opportunities of today and tomorrow it is essential to be informed about the history of psychology in different countries and cultures.

The major focus of this chapter is upon psychology in the United States as an example of an indigenous psychology that has in many respects dominated the history and development of psychology around the globe. Accordingly, we examine some of the fundamental ideas of American psychology and their applications. We also examine the dynamics of global and local forces as they impact psychology in the United States, and identify three critical challenges facing psychology here as well as in other countries and cultures. We conclude the chapter by emphasizing the importance of applied knowledge grounded in solid data sets and theory.

When you finish studying this chapter, you will be prepared to:

- Describe psychology as a science and a profession

- Appreciate the breadth of psychology and its relationship to other disciplines

- Appreciate local and global dynamics influencing psychology in the United States, the American Psychological Association, and the Association for Psychological Science

- Describe the three issues in psychology in the United States focusing upon credentials, diversity, and prescription privileges

- Define psychology and identify a new vision for the field

Psychology, the science and profession, focuses upon the ABCs of life, that is, the systematic study of the affective (A), behavioral (B), and cognitive (C) systems and their interaction in living creatures, especially but not exclusively human beings, in a variety of contexts. Although psychology focuses upon affects or feelings, behaviors, and cognitions (i.e., thoughts, memories, and expectations) of individuals and groups, it shares this interest with many other disciplines ranging from the arts and humanities, the social sciences, the biological sciences, and medicine. Psychology is a rich mix of scientific and artistic methods of inquiry and applied strategies.

Scientific psychology seeks to discover invariant laws that govern the affective, behavioral, and cognitive systems of all humans and infrahumans (e.g., hominids such as chimpanzees and apes as well as other mammals such as dogs and cats). Scientific psychology is most often conducted in university laboratories with an emphasis upon understanding and explaining affective, behavioral, and cognitive systems while professional psychology focuses upon the application of psychological knowledge. Most psychologists around the world practice psychology by providing psychotherapy to individuals or groups. For our purpose, applied psychology refers to the broader delivery of psychological services in a variety of settings to a wide variety of persons in our communities, schools, workplaces, and governments.

To be an effective psychologist anywhere today, it is essential to envision the world with an informed view of the historical development of key psychological ideas and findings. It is also important to be informed about applied strategies derived from systematic research, which may have involved many different methods of inquiry, ranging from controlled laboratory experiments and field-based studies to postmodern methods of inquiry and analysis such as deconstructionism. Psychology without application can lead to pedantry and irrelevance while psychology without a grounding in systematic research findings can lead to fads and inconsequential, even harmful interventions (Christopher et al., 2014).

People have yearned to understand themselves and others long before psychology became a formal science and profession. This need to know has expressed itself over the millennia through personal reflection, religions, spiritual and rational philosophies, and the sciences, all of which remains a fundamental part of a fuller understanding about the human experience. Accordingly, this long-standing universal need to know likely led Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850–1909), a psychologist known for early work in systematic studies of human memory, to comment that “Psychology has a long past but a short history.” Unlike the history of psychology, psychology as a science began in 1879 at the University of Leipzig with Professor Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) at the helm.

The past of psychological inquiry is richer and more varied. It could be said that the earliest history of psychology began around 50,000 years ago when some cultural hominid, a human or human-like creature living in a group, took some time out from the pressing demands of daily survival and reflected on fundamental questions about the meaning of existence and community. As the evolving inquiry became more shared, public, and systematic over the millennia, persons from religion, philosophy, the arts, and the sciences stepped in to answer enduring existential questions, leading eventually to the formal establishment (in 1879) of the science and later the profession of psychology.

Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, the knowledge held by most psychologists is predominantly the history of Western psychology of the 19th century, coupled with more recent historical developments in psychology (Mays, Rubin, Sabourin, & Walker, 1996; Pawlik & d’Ydewalle, 1996). Psychology in most places around the globe is comparatively ethnocentric or culturally bound, which stands in contrast to the current Zeitgeist or Spirit of the Times of globalization (Triandis, 2001, 1996). Worldwide webs of communication, trade, and travel along with the international transfer of technology contribute to the need for a global psychology (Gergen, Gulerce, Lock, & Misra, 1996; Lunt & Poortinga, 1996). Psychology must move in the inevitable direction of globalization or risk being left behind.

American psychology is influenced by local economic, philosophical, and governmental systems as well as by cultural traditions. Psychology in all countries around the world has been influenced by this local/global dynamic. The following is a brief history of both the American Psychological Association and the American Psychological Society.

The American Psychological Association (APA) was founded primarily through the organizational efforts of Granville Stanley Hall (1844–1924), held its first preliminary meeting on July 8, 1892, and is today the largest psychological association in the world (Evans, Sexton, & Cadwallader, 1992). Although there are in most cases large and absolute differences in membership between APA and other national psychological associations, the rate of growth of its patronage is decreasing in the United States while increasing rapidly in many other countries such as Israel, China, and South Africa (Mays et al., 1996; Sexton & Hogan, 1992).

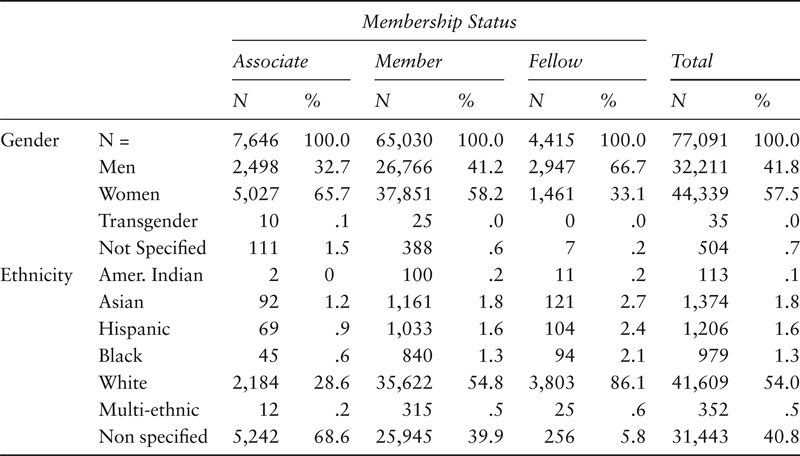

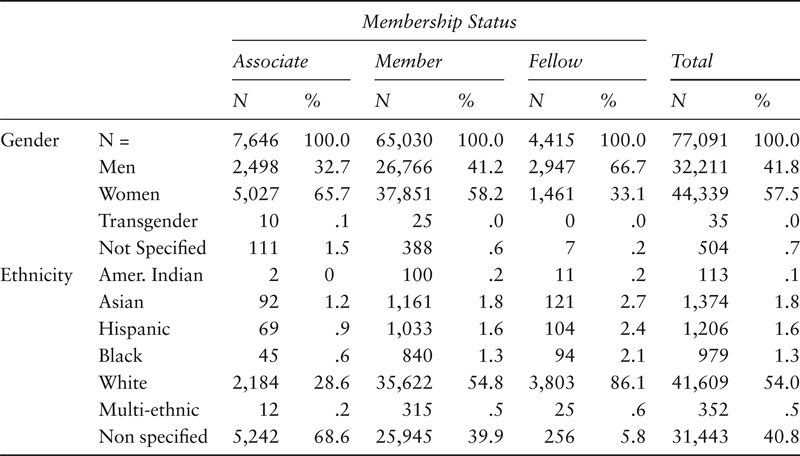

In its 125 years of history, the American Psychological Association has elected only 16 women presidents; the first of whom was Mary Whiton Calkins in 1905, and the most recently elected woman was Susan H. McDaniel in 2016. A profile of the 2016 APA membership is presented in Table 2.1, in which one can observe a marked asymmetry by gender of APA Fellows, 2,947 men compared to 1,461 women. This gender difference in Fellow status is more striking, as there are more women members (44,339) than men (32,211). Given the above membership profiles, it is reasonable to conclude that women have less influence and representation in APA as Fellow status signifies outstanding and unusual contributions to the science and profession of psychology, and affords members access to set APA policies and procedures while the two other membership categories cannot.

Tensions within the APA have influenced psychology in the United States particularly between the science and practitioner wings. For example, at the beginning of the 20th century there was division between two types of science in psychology. One was the older, laboratory-based experimental psychology imported from Germany and advocated by Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927) known as structuralism. Titchner was an

Englishman who earned his PhD from Wilhelm Wundt at Leipzig University and believed that psychology was a laboratory science. He founded “The Experimentalists” separate from the APA to focus the attention of psychologists primarily upon psychology as a laboratory science rather than a profession (Goodwin, 1983). The alternative to structuralism was called functional psychology or functionalism, which was the original indigenous psychology in America. Functionalism stressed individual differences, the application of psychological knowledge to address individual and social needs, and mental measurement of intelligence, personality, and job skills. American psychology is still searching for the optimal balance between psychology as a science and as a profession.

Table 2.1 American Psychological Association Membership: 2016 (modified)

At the end of World War II the Veterans Administration sponsored an extensive program to train clinical psychologists to augment the efforts of psychiatrists dealing with the massive psychological needs of returning veterans (Albee, 1959). The Boulder Conference, a signal event in the history of American psychology, attempted to codify and standardize clinical training and yielded a clinical training model of scientist-practitioner to achieve a working relationship between psychology as a science and a practice, which worked, although somewhat awkwardly, for about 25 years (Peterson, 2000; Raimy, 1950).

The APA currently consists of 56 divisions with each division maintaining its own mission, structure, and literature. Further information pertaining to each division housed within APA can be linked to from the APA main website, www.apa.org. The science-oriented group known as the Assembly of Scientific and Applied Psychologists (ASAP) broke away from the APA in 1988 and formed a rival organization known as the Association for Psychological Science (APS).

In the 1980s a new division within the APA emerged between many academic psychologists engaged primarily in research as contrasted with the much larger number of those providing clinical and counseling services (Rice, 1997). Despite this division between science and practice, the general membership of APA voted to maintain what was then the organizational structure of the APA Council of Representatives and the divisional structure focused upon specific areas within psychology such as clinical, developmental, gay and lesbian issues, and sports psychology, rather than a federation of semiautonomous societies reflecting major constituent identities (Dewsbury, 1997; Rice, 1997).

The Association for Psychological Science (APS) was founded in 1988 to advance scientific psychology and its representation as a science on the national level. Membership included leading psychological scientists and academics, clinicians, researchers, teachers, and administrators.

The society rapidly became involved in advocacy for psychological science. In January 1989, APS organized the first Summit of Scientific Psychological Societies, a collection of representatives from over 40 psychological organizations, to discuss the role of scientific advocacy, the enhancement of psychology as a coherent scientific discipline, the protection of scientific values in education and training, the use of science in the public interest, and the scientific values of psychological practice.

In response to some of the previous issues, and convinced of the need for a new cadre of young behavioral science investigators, APS prompted the creation of the Behavioral Science Track Award for Rapid Transition (B/START) program at the National Institute of Mental Health, which was launched in 1994. The B/START program was expanded to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in 1996, and later to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in 1999. In 2006 APS membership was 15,000; by 2015 it had grown to nearly 53,000 members.

The relationship between psychology as a science and psychology as a profession is still evolving. We focus on three critical issues that need be addressed. First is the designation of the doctoral degree as either PhD (Doctor of Philosophy—the research degree) or the PsyD (Doctor of Psychology—the professional degree); second is finding the appropriate educational and service response to fast-growing diversity on the American campus and in the clientele served by psychologists. The third issue is that of drug prescription privileges for psychologists.

The Doctor of Psychology (PsyD) became available in the 1970s, and was designed to provide better training for applied clinical therapy work. The PsyD emphasizes training for the practice of psychology while the PhD focuses on research with admission requirements about the same for both degree programs. The major difference between the degree programs arises in in the later years with PsyD focusing on applied psychology through internships with the PhD emphasizing research papers and dissertations. Both programs take four to seven years to complete, both require an internship, and almost all PsyD and PhD require a doctoral dissertation.

The American Psychological Association accredits both PsyD and PhD programs, and it is important to document that the degree program of interest to you is APA accredited. Most state licensing boards require applicants to have completed their degree and supervised internship at an APA-accredited institution.

The degree designation issue needs to be monitored continually as to make sure that the public can make informed decisions in selecting a psychologist with the appropriate professional credentials for the provision of psychological services.

Hall, Yip, and Zarate (2016) believe that American psychology must make substantive modification to its curriculum, training, research, and practice components to respond appropriately to the changing demographics of the U.S. population. Similarly, the rising acceptance of bisexuality among the youth of America (Leland, 1995), and a gay and lesbian population of about 10–12% in the United States makes plain the need for the further diversification of psychology (Crooks & Baur, 1990).

Although the APA has been supportive of diversity, substantive curricular and policy changes are needed within psychology. Underrepresented minority groups held approximately 13% of faculty jobs in 2013, up from 9% in 1993. Yet they still only hold 10% of tenured jobs (Inside Higher Ed, www.insidehighered.com/news/2016).

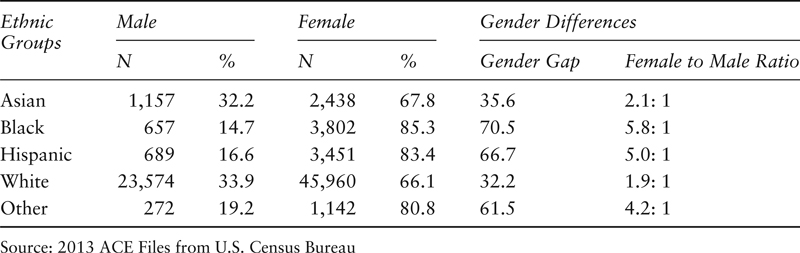

Table 2.1 presents APA membership by ethnicity. Note that whites make up the largest ethnic group of members, 41,609 compared to 4,024 that is the total of all other ethnicities combined. Also, note that 3,841 whites are Fellows compared to 358 Fellows for all other ethnicities combined. In addition, very few ethnic minorities have served at the policy level or board of directors.

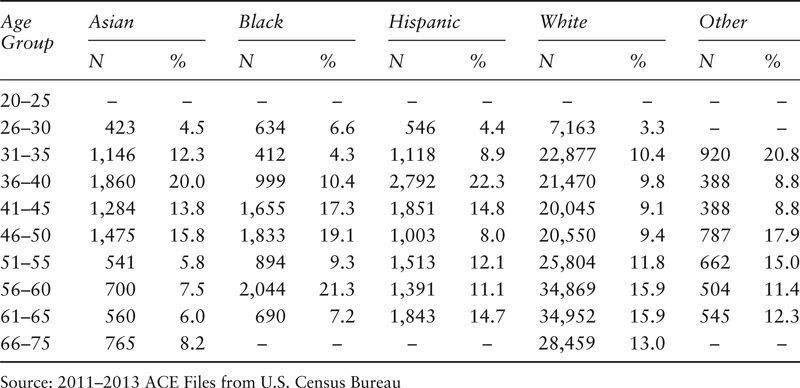

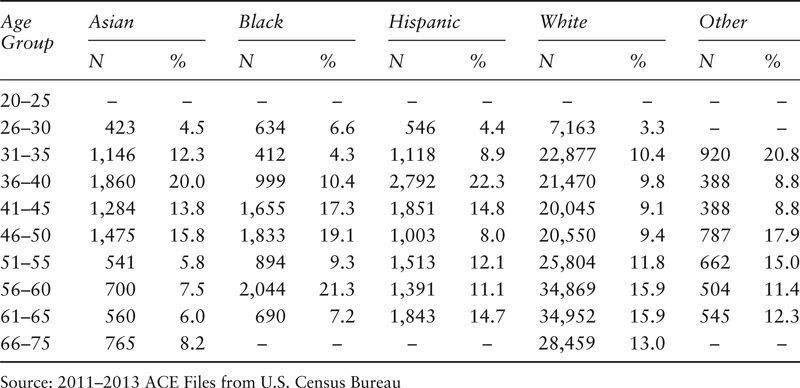

From 2005 to 2013, the percentage of Asians in the psychology workforce grew 80%, and black/African American practicing psychologists doubled in size. The proportion of Hispanic psychologists increased by 47%, while the proportion of “other ethnic groups” increased by 67%. With larger numbers of young ethnic minority psychologists entering the field, the mean ages of ethnic minority groups were lower than the mean age of white psychologists (www.apa.org/workforce/publications/13-demographics/index.aspx).

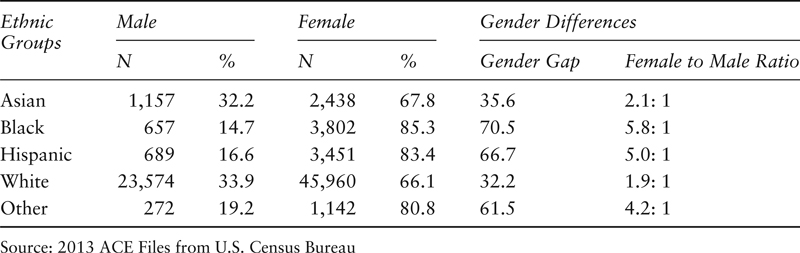

The gender gap in the number of active psychologists widened with fewer males than females entering the workforce (see Table 2.3). With larger numbers of young ethnic minority psychologists entering the field, this group of psychologists are younger than the average white psychologists in the workforce (see Table 2.2).

While psychology remains a popular subject on American campuses and abroad, American psychologists currently account for only 21% to 24% of the world’s psychologists (Bullock, 2012a). Takooshian, Gielen, Plous, Rich, and Velayo (2016) believe it essential to vigorously pursue the internationalization of American psychology curricula and

professional practices to be better prepared to connect with and support an increasingly diverse U.S. and world population.

Table 2.2

Estimate Number and Percentage of Active Psychologists by Ethnicity and Age (modified)

Table 2.3 Estimate Number and Percentage of Active Psychologists by Gender & Ethnicity (modified)

In Chapter 1 we mentioned that multicultural collaborative benefit from culture-sensative practices, such as balancing traditional Western quantitative measurement/categorization/labeling research methodology with a pluralistic notion of science (Yakushko, Hoffman, Morgan, Melissa, & Lee, 2016; Lykes, Hershberg, & Brabeck, 2011; Rogers, 2009). For example, when a culturally diverse school community comes together to address a contemporaty issue, it is wise to choose a hybrid of cultural practices. Teachers, students, parents and school administrators, upon entering the building are encouraged to fill out a questionnaire (quantitative methodology) that is anonymously tallied and used to inform individual/collective concerns for generating group discussion. In addition, dialogue format is carefully structured to ensure respect for diverse perspectives, interests, and needs, while fostering constructive conflict resolution practices and community ownership. The collective wisdom that inspires and guides this decisionmaking process is born of value pluralism. William James (1956) once said, “There is very little difference between one person and another, but what little difference there is, is very important” (pp. 256–257).

The third source of tension within psychology is the scope of prescription privileges for psychologists as those privileges can and do vary from state to state. There is a long and continuous debate in the literature of the benefits and potential risks associated with providing psychologists prescription privileges. More than 22 years ago, Deleon, Sammons, and Sexton (1995) constructed a standard two-year psychopharmacological curriculum including a clinical internship like that employed by the U.S. Department of Defense Psychopharmacology Demonstration Project (PDP). Completion of this process would give prescription privileges to psychologists and other non-physician health care providers (i.e. optometrists, advanced practice nursing field, etc.).

Those opposed to the Deleon et al. proposal expressed concerns about prescription privileges potentially moving psychology away from the traditional practice of assisting people in acquiring more effective thinking and behavior patterns, which have been shown to be highly effective strategies. A Consumer Reports survey of approximately 4,000 persons who received only psychotherapy for a broad range of disorders indicated that they improved as much as those who received drugs in addition to the therapy, without the side effects frequently associated with medications (Seligman, 1995). There is also concern that the prescription privileges laws being determined by each state will lead to costly and single-focus legislative battles in state legislature depleting each association’s financial resources and ignoring other important issues before psychology (DeNelsky, 1996; Hayes & Heiby, 1996).

In 2002, New Mexico was the first state to give specially trained psychologists the authority to prescribe certain drugs related to the diagnosis and treatment of mental health disorders (Holloway, 2004). Presently there is prescription privilege legislation pending in 18 states including Ohio, Texas, California, New York, and New Jersey.

Psychology is the science and profession that focuses primarily upon the A ffective, B ehavioral, and C ognitive systems of living creatures, especially, but not exclusively, human beings. Accordingly, we define psychology as:

The systematic investigation of affective, behavioral, and cognitive systems and their interaction in a variety of creatures and contexts.

Psychology as a science focuses upon knowledge that promotes understanding while psychology as a profession focuses upon using knowledge to solve problems and enhancing the capacities of an individual or group. The future of psychology requires the continuing interaction between the scientific and applied sides of psychology, which was noted as early as the first annual meeting of the American Psychological association in 1892 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

According to Martin Seligman (1998), the 1998 president of the American Psychological Association, a new vision for psychology in the United States, which has evolved from events over the past 100 years. From 1900 to 1945, psychology in the United States focused upon finding solutions and developing appropriate strategies to treat mental illness, making the lives of all people fulfilling, and identifying and nurturing talented persons. However, from the end of World War II up to the present, American psychology has focused primarily upon understanding and providing psychotherapy for individuals with behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional problems or dysfunctions (Seligman, 1998 January). In short, the bulk of psychology in the United States for the second half of the 20th century has focused an inordinate amount of attention and resources on individual illness, dysfunction, and morbidity rather than wellness, prevention, and further strengthening of effective and resilient individuals as well as understanding and providing services to groups and families.

The new vision for psychology as reflected in Seligman’s work and that of many others (Fredrickson, 2001; Sheldon & King, 2001) focuses upon positive psychology as “the scientific study of ordinary human strengths and virtues” (Sheldon & King, 2001) and is a reaction to the primary focus of psychology upon pathology over the past 50-plus years. Likewise, although there are some links to religious movements and related positive-thinking campaigns, positive psychology is more grounded in empirical observations and experimentation.

As a consequence of working in a medical model focusing upon personal weakness and on the damaged brain for the past 50 years, psychology in the United States is not well-equipped to deal with a broad range of applied problems and is like other indigenous psychologies around the world, which also face massive applied social problems. As Seligman (1998) made plain, we need to focus our resources upon studying and enhancing human strengths and virtues. Psychologists need to appreciate that much of the best work they do is amplifying the strengths rather than repairing patients’ frailties and dysfunctions. Positive psychology requires that psychologists around the world continue to develop psychological models or theories to support a psychology of strength and resilience and continue to repair individuals damaged by corrosive habits, drives, childhood experiences, or brains. As we move deeper into the new millennium of the 21st century, psychology in the United States is shifting attention to prevention and addressing a wider array of applied social challenges by understanding and applying the forces of courage, optimism, interpersonal skills, value of work, hope, integrity, mutual respect, and endurance. Psychologists are now seeing more clearly individuals as decision makers with choices, preferences, and competencies who can manage their own lives, families, and communities, and who periodically need support to avoid or escape from helplessness and hopelessness.

This vision for psychology requires sustained and systematic communication between scientists and practitioners to make certain that applications of psychology are firmly grounded in a systematic body of knowledge. Beutler, Williams, Wakefield, and Entwistle (1995), based upon a national survey of 325 psychologists, found that clinical practitioners value and listen to science more than scientists value and listen to clinicians with the possible consequence that scientists may be missing important avenues for identifying critical areas of research.

As people around the world become increasingly interdependent and connected, psychologists must move with flexibility toward a global psychology or be left behind.

Psychology is a science-seeking knowledge for understanding the affective, behavioral, and cognitive systems of primarily but not exclusively human beings. Likewise, psychology is also a profession that consists of practice strands focused upon the delivery of individual and group psychotherapy as well as applied interventions grounded in systematic psychological knowledge to address the wide variety of challenges and opportunities for preventing problems and strengthening further thoughtful, resilient, and courageous individuals and communities. To be an effective psychologist it is essential to be grounded in the historical development of key empirical psychological ideas and findings and their application in a variety of contexts around the world.

Psychology around the world, whether in the United States, China, India, Latin America, or anywhere, is influenced by global and local forces and issues. What counts in contemporary psychology is a sound grounding in the historical development of empirical foundational ideas and systematic findings and the application of these to the many challenges facing humanity around the world.

Discussion Questions

- Define psychology and explain the ABCs of psychology.

- What are the distinguishing characteristics separating the science and profession of psychology?

- How does psychology influence other disciplines?

- What is the role of the two largest psychological organizations in the United States?

- What are the three pressing issues of psychology in the United States?

- Where is the future of psychology headed?