Psychology has gradually evolved into a science over the past 138 plus years. In the early formative years of psychology, it was the work of a few German scientists that launched the discipline as a separate science from biology, chemistry, physics, and the extensive influences of philosophy. Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795–1878) focused his psychological experiments upon psychophysics and consciousness by studying systematically the just noticeable difference (JND). The JND was defined as the difference between two stimuli detected accurately on 75% of the presented trials.

Gustav Fechner (1801–1887) argued for psychophysical parallelism, according to which the mental and physical worlds run parallel to each other but do not interact. Fechner developed the Weber–Fechner law, according to which the perceived intensity of a stimulus increases arithmetically as a constant multiple of the physical intensity of the stimulus or S = K Log R. In other words, changes of physical intensity gallop along at a brisk pace while the corresponding changes of perceived intensity creep along. The Weber and the Weber–Fechner laws were the first laws to provide a mathematical statement of the relationship between the mind and the body. Another significant contribution to the psychophysical foundations of psychology was made almost 100 years later when S. S. Stevens (1906–1973) demonstrated that psychological intensity (experiences of physical magnitudes) grows as an exponential function of physical stimulus intensity, that is, equal stimulus ratios always produce equal sensory ratios although different ratios hold for different sensory modalities (S = KΦb).

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) used Weber and Fechner’s work on the relationship between subjective and physical intensities as a key component in the establishment of psychology as an independent science. Voluntarism, as Wundt’s new psychology became known, focused upon the specific subject matter of immediate conscious experiences of an adult studied by systematic introspection. The use of systematic introspection or the more specific strategy known as internal perception, a narrow focus on verbal immediate responses to precisely controlled stimuli by trained observers, was an attempt to avoid committing the stimulus error. The stimulus error arises when the person focuses primarily upon a description of the stimulus instead of the conscious experience evoked by a stimulus.

Wundt’s interests were widely diversified and included topics such as mental chronometry and cultural psychology or Völkerpsychologie. Mental chronometry was a systematic laboratory method for measuring the speed of mental processes that included measurements of discrimination and choice reaction times. The primary objective of mental chronometry was to demonstrate that psychological or mind functions could be measured, studied scientifically, and yield consistent findings indicating that mind or psychological processes follow identifiable laws.

Some of Wundt’s contemporaries differed with him not only about the subject matter of psychology, but also the primary methods of study of psychological phenomena. For example, Franz Brentano (1838–1917) envisioned an alternative subject matter for psychology that focused upon the study of the activities or acts of the mind consisting of recall, feelings, and judging, his Act Psychology. Likewise, Oswald Külpe (1862–1915) focused upon the study of imageless thought. Külpe argued that some thoughts or ideas arose in consciousness without specific images, which ran directly opposite to Wundt’s psychology that consciousness always consisted of some combination of the three elements of consciousness (i.e., sensations, feelings, and images).

Edward Bradford Titchener (1867–1927) was responsible for introducing Wundt’s voluntarism to the United States under the name of structuralism.

Wundt’s conceptualization of the psychological experiment was the first in a series of three specific models that have been integral steps in the construction of the current psychological experiment as we know it today. The Leipzig or Wundtian model was characterized by the lack of distinction between the ideas of experimenter and subject as they were interchangeable roles. The Parisian model did not permit the interchange of roles between the experimenter and the subject as in the Leipzig model, but rather established rigid experimenter–subject (or doctor–patient) roles considered critical for objective experimentation. Finally, the American model, the most recent model, introduced the study of populations, samples, and groups of persons rather than only the study of individuals, leading to an emphasis on keeping individual subjects anonymous and constructing experimental protocols requiring relatively brief experimenter–subject contacts.

Recently, psychologists taking the lead from Wundt’s analysis of consciousness into three components (sensations, feelings, and images) have studied systematically human love and identified three components of love. Specifically, the triangular theory of love describes the three elements of love: intimacy, passion, and decision or commitment. According to this theory, it is possible to have combinations of some or all of these three elements that yield different types of love. Love that is referred to as liking is the combination of experiences of the intimacy component of love in the absence of passion and decision commitment, while romantic love is the combination of intimacy and passion causing lovers to be drawn not only physically to each other, but also with an emotional bond yet without necessarily a long-term commitment. The combination of all three elements of love is consummate love and is very difficult to maintain once it is reached.

When you finish studying this chapter, you will be prepared to:

- Define the relationship between the mental and physical worlds as described by the psychophysical laws proposed by E. H. Weber, G. T. Fechner, and S. S. Stevens.

- Identify and define Fechner’s three psychophysical methods

- Describe the role that psychophysics played in the development of Wundt’s psychology of voluntarism

- Explain the challenges that psychology faced in the early years as an independent science

- Identify the subject matter (immediate conscious experience) and method of study (systematic introspection of conscious experiences) of Wundt’s new psychology, voluntarism

- Describe the elements of consciousness according to Wilhelm Wundt

- Explain and define simple, discrimination, and choice reaction times as expressions of mental chronometry

- Compare and contrast the work of Franz Brentano and Oswald Külpe to that of Wundt

- Describe E. B. Titchener’s study of consciousness and his core context theory of meaning

- Define and distinguish between Wundt’s voluntarism and Titchner’s structuralism

- Explain the social development of the psychology experiment

- Identify the three components of the triangular theory of love

The majority of what we take for granted today in the field of psychology in many respects is the direct result of pioneers such as Ernst Heinrich Weber, Gustav Theodor Fechner, Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt, and Edward Bradford Titchener. The foundation of the current field of psychology, not even considering the subfields and clinical practices, are based on findings from their early basic research utilizing laboratory experiments. The psycho-physicists such as Weber and Fechner and much later S. S. Stevens introduced the strategy of examining the relationship between the physical and mental worlds by deriving mathematical equations that arose from empirical laboratory-based experiments.

Wundt was then successful in introducing this view of rigorous study of psychological phenomena into somewhat controlled laboratory experiments. Accordingly, Wundt defined the subject matter of psychology and established the first laboratory and method of study for psychology. Although his early methods have changed and have been expanded greatly as the science has grown, his was the first step toward the empirical basis of laboratory research in psychology.

Psychophysics set out to describe and understand how the intensity of sensory experiences related to the physical intensity of stimuli and to determine if a lawful relationship existed between the physical and subjective worlds. In the beginning, psychophysics provided laboratory-based tools to determine the relationship between the mental and physical worlds, and also set the stage for the importance of defining the subject matter and methods of study in the subsequent schools of psychology, beginning with Wundt’s voluntarism.

Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795–1878) was a professor of anatomy at the University of Leipzig, where his earlier studies in anatomy, biology, physiology, and physics prepared him, along with his brother, to discover the utility of excitatory and inhibitory functions of the central nervous system. Later his interests shifted toward the study of sensations arising from the skin and muscles, which led him to publish a classic in experimental psychology in 1834, The Sense of Touch (Weber, 1978).

Weber was interested in determining how we detect or become aware of the difference in intensities between two stimuli, which we do automatically on a daily basis when, for example, we lift objects and notice one just heavier than another, or when we turn up the volume on our radio or television so we can hear it just a little more loudly. Weber found that the judgments we make of the intensive differences between two stimuli are relative rather than absolute. For example, if we had one canister or box filled with sand and this standard stimulus weighed 120 grams, the question then becomes how much do we have to change (increase or decrease) the weight of another canister or box (the comparison stimulus) to just notice the difference in weight between these two stimuli. In this example for lifted weights, Weber found consistently that he had to add (or subtract) 3 grams to the comparison stimulus for the difference to be just noticed reliably (i.e., on 75% of the test trials). Thus, the relative difference between two weights had to be 1/40 to detect reliably the difference between the weights of the two objects.

Put another way, K = Δ I/I, where K is the experience of the just noticeable difference (JND), Δ I is the amount of change of the physical intensity of the comparison stimulus over the standard stimulus or I (Weber, 1978). Thus, to just notice the difference consistently between a standard stimulus, say, of 200 grams, the other lifted weight (the comparison stimulus) had to weigh now 5 grams more (205 grams) to be perceived consistently as just heavier or 5 grams less (195 grams) to be perceived consistently as just lighter than the standard. Ratios between the intensities of stimuli matter rather than the absolute differences between the intensities of the stimuli. K = Δ I/I is known as Weber’s Law and was the first mathematical statement that described the relationship between the physical and psychological worlds.

In general, the Weber fraction varies from one sensory system to another, and is valid only over the middle of the intensive continuum for any sensory system. Thus, for example, the Weber fraction is 1/50 for length so if the length of a line (the standard stimulus) was 100 millimeters (just a little more than 3¾ inches) then the comparison stimulus or other line would have to be 104 millimeters long (just a little more than 4 inches) to be perceived consistently as just longer, while the comparison would have to be 96 millimeters to be perceived consistently shorter than the standard of 100 millimeters. However, the just noticeable differences for very heavy or very light weights or very long or very short lines would yield Weber fractions much larger than the above 1/40 and 1/50, respectively. Albeit, Weber’s findings were all that some others needed to make the case that the mind or psychological functions could be measured and psychology could be considered a separate discipline distinct from philosophy and biology although arising from and related to both of these disciplines.

Gustav T. Fechner (1801–1887) was a trained physician who argued for psychophysical parallelism, according to which the mental and physical worlds run parallel to each other but without direct interaction. After graduating with his MD in 1822, he focused his work strictly on physics. His interest in a demonstrable relationship between the mind and body emerged following his resignation from his position as the chair of physics at the University of Leipzig in 1838, as a result of severe emotional exhaustion. His emotional disturbance was a reaction to what he perceived as permanent blindness; however, when he regained his sight, his emotional health improved as well. He resumed his faculty position at the University of Leipzig in 1848 as a professor of philosophy rather than as professor of physics.

His program of work in psychophysics began with the publication of Zend Avesta, On Concerning Matters of Heaven and the Hereafter (Fechner, 1851). This magnum opus contained the psychophysical law that bears his name, which came to him in a dream on the morning of October 22, 1850, when he had an insight that there must be a measurable relationship between sensory and physical intensities. According to the Weber–Fechner Law, the perceived intensity of a stimulus increases arithmetically while physical intensity gallops along as a constant multiple of physical intensity, or S = K Log R. In this equation, S is the perceived intensity, K is a constant, and Log R is the logarithmic function of the physical intensity of the stimulus. The logarithmic function describes sensation as growing in equal steps (arithmetically) while the corresponding stimulus intensity continually increases as a function of a constant multiple (geometrically). Thus, larger and larger outputs of stimulus energy are required to obtain corresponding sensory incremental effects, or, as eloquently described by Woodworth (1938, p. 437), “The sensation plods along step by step while the stimulus leaps ahead by ratios.” This means that as a stimulus gets larger there must be a larger change in stimulus intensity for a change to be detected (Fechner, 1966/1860).

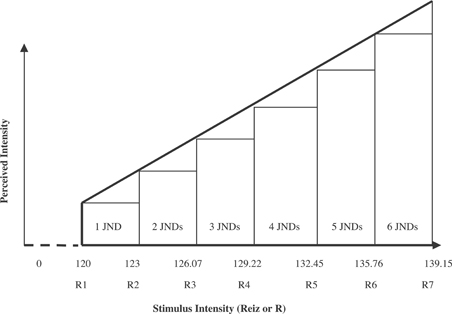

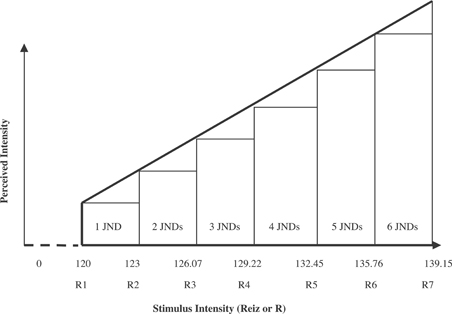

Let us take, for example, lifted weights that have a Weber fraction of 1/40, and start with a standard stimulus weight of 120 grams (R1) shown on the x or horizontal axis in Figure 8.1. We already know that for a comparison weight to be perceived as just heavier, it has to be 123 grams (R2), as shown in Figure 8.1. Now, for a comparison stimulus to be judged just heavier than R2 of 123 grams it has to be 126.07 grams (R3); for another comparison to be perceived as just heavier than R3 (126.07 grams) it has to weigh 129.22 grams (R4); for comparison stimulus to be perceived as just heavier than R4 (129.22) it has to be 132.45 grams (R5), and so on, with stimulus intensity along the x axis increasing as a constant multiple of 1/40 (the Weber fraction) and perceived intensity increasing along the vertical or y axis increasing as a constant addition of JNDs. Fechner argued that the perceived intensities of a stimulus as indicated by the JND are additive such that a weight of 126.07 would be perceived as twice as heavy as the original standard stimulus of 120 grams, while a weight of 129.22 would be perceived as three times heavier than the original standard. Although the argument was elegant, the data did not fit precisely the predictions of the Weber–Fechner Law as JNDs are not additive. Thus, as in the above illustration of the progression of physical and perceived intensities, R4 is not perceived consistently and therefore lawfully as three times heavier nor is R3 perceived consistently

as twice as heavy as the standard stimulus, R1. In addition, the Weber–Fechner Law required a true zero for the perceived scale, the absolute threshold, which is variable, depending upon how it is measured, and changes slightly over time during measurement.

Figure 8.1 A Visual Representation of the Weber–Fechner Law—S = K Log R

Gustav T. Fechner also introduced three psychophysical methods into psychology that were very important to Wilhelm Wundt when he launched psychology as a laboratory-based experimental science in 1879. The method of just noticeable differences or the method of limits, as it is called today, requires a person to compare two stimuli with the intensity of one varied (the comparison stimulus) until the person notices the comparison as just different from the other or standard stimulus. The data described earlier in this section and the data presented in Figure 8.1 have been collected using the method of limits. The method of average effort or adjustment was Fechner’s second method and requires the person to adjust or change continuously a variable stimulus until it matches a standard stimulus or appears just different. This method can be used to measure both the difference limen or threshold (DL, the just noticeable difference) and/or the absolute limen or threshold (AL, that stimulus energy that is detected on 50% of the trials with this statistical value set somewhat arbitrarily by the experimenter and thus can yield different ALs). In the method of constant stimuli or right and wrong cases, comparison stimuli are paired randomly with a standard stimulus and the person reports whether the comparison stimulus is greater than, equal to, or less than the standard stimulus or, alternatively detected or not detected. This method is used to measure both the difference and absolute thresholds, respectively. In all three of Fechner’s psychophysical methods, repeated measures are taken yielding average values such that both the difference and absolute thresholds are best thought of as statistical values rather than fixed immutable values. Some variations of Fechner’s original three psychophysical methods are still used today, for example, to measure air quality or how much sweetener needs to be added to a cereal so that it appears just sweeter than unsweetened cereal, which can save the manufacturer large sums of money when tons of cereal are produced. Lastly, as any seasoned cook well knows, we use some of Fechner’s methods when adding just the right amount of herbs, condiments, and/or oils to produce our favorite dishes.

The Weber and the Weber–Fechner laws were the first laws to provide a mathematical statement of the relationship between the mind and the body based upon systematic psychophysical methods employed in a laboratory setting. Weber and, especially, Fechner were revolutionary in their thinking and methods of study pointing psychology in the direction of examining potential lawful relationships in the field. These laws, along with Fechner’s three psychophysical methods, the advances in brain localization, nerve physiology, and philosophy stressing empiricism and associationism, provided the fundamental calculus to launch the new science of psychology (Fechner, 1966/1860).

We now move ahead to a scientist who was very much influenced by the work of E. H. Weber and Gustav Fechner but not in agreement with their proposed laws. S. S. Stevens (1906–1973) presented yet another set of principles by which the mind–body relationship could be measured in his paper “To Honor Fechner and Repeal His Law” (Stevens, 1961). In this paper, Stevens respectfully demonstrated that the Weber–Fechner law was incorrect because it does not apply at the extreme ends of any intensive continuum; for example, weight, brightness, length, and JNDs are not equal and cannot be added one to another. Accordingly, Stevens believed sensory or psychological intensity (experiences of magnitude) grew as an exponential function of physical stimulus intensity by which equal physical ratios always produce equal sensory ratios. Stevens’ Law is written as S = KØb in which S is equal to sensory intensity, K is equal to a constant, Ø is equal to physical intensity, and b is the exponent for the relationship between sensory and physical intensities.

Examples of this relationship can be seen in length, brightness, and electric shock. In terms of length, for a line to appear twice as long as another (double sensory intensity), we must increase the length of a line by 100% (i.e., double the length). Thus, the exponent describing this sensory continuum is 1.0. Brightness, on the other hand, requires an increase in physical intensity of the light by 900% for the light to appear twice as bright; thus, the exponent is 0.33. Turning to electric shock, we learn that for an electric shock to appear twice as intense as another electric shock we only need to increase the stimulus intensity by 20%. Thus, the dynamic range of perceived intensities of brightness is very broad allowing us to see under very dim and extremely bright conditions. On the other hand, the dynamic range of perceived intensities for electric shock is very narrow such that small changes in the intensity of electric shock are perceived as very large, thus protecting us from potential tissue damage and possible electrocution.

Stevens came to these conclusions by utilizing magnitude and cross-modality estimations. With magnitude estimation the subject estimates directly the sensory intensity of a stimulus relative to a modulus or referent, whereas with cross-modality estimation the subject is asked to measure directly sensory intensity by matching one sensory intensity (e.g., hand-grip intensity) against another sensory intensity (e.g., line length). In general, both of these psychophysical methods yield consistent and reliable results.

The initial two theorists, Weber and Fechner, and later Stevens, made a significant contribution to the field of psychophysics by exploring the relationship between the existential duality of nature, the physical and mental worlds, and paved the way for the progress of deciphering lawful relationships in psychology for years to come. The successful implementation of methods of measuring mental processes in general was notable, but we must also remember the passion that drove these scientists to achieve that point, and that is the desire to understand the relationship between mind and matter, sensation and stimuli, and internal and external environments.

Wilhelm Wundt formally founded a laboratory-based experimental psychology in 1879 when he established the first experimental laboratory at the University of Leipzig with the intent to “mark out a new domain of science.” It was Wundt who took the psychophysical tools and findings reported by Weber and Fechner and launched psychology as a separate scientific discipline, and in so doing transformed psychology from a branch of philosophy into a science. His desire to move psychology away from unsystematic introspection employed by philosophers toward the use of the scientific method was directly influenced by his medical background. His interest in laboratory work began with the realization that the practice of medicine was not for him and thus he initially pursued research in physiology, which later came to include a growing interest in psychology and psychological research. The combined interest in physiology and psychology led Wundt to write (1969/1910) Principles of Physiological Psychology in 1910. His position at the University of Leipzig teaching sensory physiology, psychology, anthropology, and physiology afforded him the opportunity to establish himself as one of history’s most productive research scientists by publishing an average of two journal publications per month in the journal he created, Philosophische Studien (Philosophical Studies) during his first four years at Leipzig.

In many ways, it is surprising yet fortuitous that Wilhelm Wundt established psychology as an independent science. First off, Wundt, for a variety of reasons, had a relatively lackluster academic career prior to entering medical school at the University of Heidelberg where he devoted himself totally to his studies and earned his medical degree in three years in 1855. He then turned to developing his research skills primarily in physiology at the prestigious University of Berlin, studying with prominent scientists including Johannes Müller and Emil Dubois-Raymond. Thereafter, he returned to Heidelberg, instructing medical students in the required course of sensory physiology, and in addition taught some courses of his own including one dealing with psychology as a natural science. From about 1862 to 1874, the year that he joined the University of Leipzig due to his growing and solid reputation in psychology, Wundt taught a variety of courses in physiology and philosophy, lectured on the need for the development of experimental psychology, did not make much money, married Sophie Mau in 1872, and all along continued to refine his ideas about the systematic study of consciousness (Bringmann, Balance, & Evans, 1975). Although Wundt was immersed initially in the materialistic sciences of his day, such as physiology, he was not a materialist and believed that consciousness does not arise from “a thing or substance.” Therefore, a new science was needed to identify the composition of and the psychological laws that govern conscious experiences via a laboratory-based science (Blumenthal, 1975). Accordingly, Wundt established a one-room psychological laboratory in 1879; directed as well as participated actively in student research in the laboratory; published voluminously; established a journal, Philosophical Studies; and from these developments the field of psychology as an independent scientific discipline expanded rapidly and widely thereafter. The academic dean who had recruited Wundt to the University of Leipzig in the latter part of 1864, with the expectation that Wundt would make a difference in the area of psychology, saw that Wundt was indeed a great intellect and organizer, and a hard worker, and only after Wundt threatened to move to another university did resources begin to flow his way in the mid-1880s, including the move to a multi-room, well-equipped laboratory facility.

Wundtian laboratory-based psychology is the systematic study of immediate conscious experiences and the identification of the psychological laws that govern dynamic or changing conscious experiences. The psychological process of attention and volition or choice are central to Wundt’s psychology, and accordingly he named his psychology voluntarism, which was the first formal school of psychology and is very different in many respects from E. B. Titchener’s school of psychology known as structuralism (Blumenthal, 1975). Wundtian psychology focused upon the immediate conscious experience (e.g., actually tasting an apple) rather than the mediated conscious experiences (reading about the taste of an apple) of the person. In the laboratory, the subject or participant focused upon the internal perception, that is, what the person was actually experiencing in response to highly controlled stimuli, rather than defining the properties of the stimulus which is known as the stimulus error. In other words, internal perception focused on what the highly trained person was perceiving, rather than his or her awareness of the external stimulus, with attention paid to the size, intensity, duration, quality, and affect of the experience rather than properties of the stimulus.

Immediate conscious experiences were thought to be composed of two fundamental components or elements. The first element was sensation or the basic mental process or experience that has reference to some “external thing” (the stimulus). The modality of a sensation is determined by the sensory nerve activated (e.g., the visual or auditory nerve) and could be differentiated by quality, intensity, clearness, and duration of the sensation. Affect or feelings were the second component of immediate consciousness. This element was conceptualized as experiences that accompany sensations and are perceived as more general than sensations. Feelings varied along three dimensions from pleasant to unpleasant, relaxed to strained, calm to excited. The intensity of a sensation yields changes in the nature of a feeling as, for example, slight tickling might be experienced as pleasant while more intense and protracted tickling is perceived as unpleasant. An idea, another component of consciousness, arises from combinations of sensations derived from memory or previous sensations. Ideas are retrospective and historical, while sensations and feelings are given in the immediate conscious experience related to an external stimulus (Bringmann & Tweney, 1980).

The systematic study of immediate human consciousness, which included sensations, feelings, and ideas, stressed the total perceptual experiences derived from the elements of consciousness. The combination of these elements of consciousness was thought to arise from either passive or active combinations. Passive combinations produced by perceptions were referred to as associations while active combinations were the result of apperception or what we call today selective attention. The mental process of apperception involving what the person chooses to attend to allows the individual to yield a complex unified conscious experience as opposed to an array of unorganized elements, that is, sensations, feelings, and ideas. Just as chemical elements react to yield compounds, apperception results in a total perceptual experience, which is inherently different from the sum of the individual experiences. The dynamics of apperception are illustrated by the attentional processes of blickpunt and blickfeld. The blickpunt is a glance point in which elements are the focus of attention (i.e., apperception) and blickfeld (i.e., perception) is a field of consciousness in which elements are not in the range of immediate attention or awareness. Thus, for example, you may be focused on reading the sentences on this page yet not aware of the pressure sensations from your watchband, shoes, or the chair in which you are seated until you shift your attention voluntarily to these sensations and feelings. Apperception yields new experiences similar to chemical interaction of molecules to form a whole different from the parts as, for example, water which arises from the gases of two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen.

Mental chronometry, based upon the measurements of reaction time (RT), was developed by Franciscus Cornelius Donders (1818–1889) and imported into Wundt’s laboratory as a method for measuring various mental processes. Donders and Wundt concluded that RT could be used as a measure of mental activity, which is composed of nerve impulses that had been measured as a result of the earlier work by Hermann L. F. von Helmholtz (1850), one of Wundt’s mentors. Thus, if the mind was made of nerves and nerve impulses that could be measured, it followed deductively that mental activity could also be measured. Mental chronometry in Wundt’s laboratory consisted of measuring simple, discrimination, and choice reaction times, which are progressively more complex mental operations. Discrimination reaction time (DRT) is the amount of time it takes, for example, to respond to a green light compared to simple reaction time (SRT), which is the time it takes to respond to any light as no discrimination between the color of the light stimuli is required. Thus, the duration of the mental process of discrimination could be measured as follows:

Discrimination Time = DRT − SRT

Therefore, using the subtractive process of first measuring simple reaction time and then subtracting that time from the time for discrimination reaction time provided a laboratory-based measure of the psychological process of discrimination. It then followed that perhaps more complicated psychological processes could also be measured using the subtractive process. Choice time (CT), a more complicated psychological process than discrimination time, involves the time that it takes to make a choice such as releasing one key for a green light and releasing a different key for a red light. It was believed that the mental process of choosing could also be measured as the difference between choice reaction time (CRT) and discrimination reaction time (DRT). Following our above example this relationship exists because the CRT is essentially a DRT in addition to the time to make the choice response of which key to release.

Choice Time = CRT − DRT − SRT

Many studies were conducted in Wundt’s laboratory by many of his students utilizing both discrimination reaction time and choice reaction time in experiments referred to as complication experiments. Unfortunately, the reaction time method was abandoned because the additive premise that was the foundation of this work was found invalid. Specifically, choice reaction time did not always exceed DRT plus SRT, so it failed to support the additive time expectations of the mental chronometry model.

The ten-volume Völkerpsychologie, published by Wundt in 1916, encompassed his work on group or cultural psychology over the last 20 years of his life. Wundt believed that higher mental processes such as thinking, memory, and motivation could not be studied experimentally in the laboratory but could be studied by historical analysis and naturalistic observations of members of different cultures. The Völkerpsychologie described Wundt’s belief that cultures could be understood as points on a continuum from those then considered as primitive (e.g., Australian aboriginal) to advanced (e.g., Germany) cultures. This theory was developed through addressing topics such as anthropology, the psychology of religion, and group social psychology. Wundt’s studies of the variety of subjects contributing to his model of cultural psychology were strongly influenced by Darwinian thought that identified evolution as an underlying mental process (Wundt, 1916). The comparison of different cultures along an evolutionary continuum allowed Wundt to better understand consciousness as an organized whole rather than focus only upon the individual parts of consciousness as identified by systematic yet relatively simple laboratory studies.

Clearly, Wundt was the first to present a comprehensive psychology, voluntarism, grounded in laboratory experiments of immediate conscious experience employing the method of systematic introspection and later other methods such as reaction time experiments. Interestingly, his program of psychology did not go unchallenged especially regarding the issue of the primary subject matter of psychology and the content of consciousness.

Shortly after Wundt defined immediate conscious experience as the subject matter for the new discipline of psychology, Franz Brentano envisioned an alternative subject matter, namely, the systematic study of the mental acts of consciousness. In essence, Brentano took a step away from Wundt’s work, which studied what was immediately in the mind, and a step toward the study of the activity of the mind in the mental processes consisting of recall, feeling, and judging. His success as a teacher was his ability to influence and inspire his students, one of whom was Carl Stumpf (1848–1936), who was an important influence on the founders of Gestalt psychology.

Specifically, Brentano thought that psychology needed to focus upon mental acts of consciousness as opposed to the contents of consciousness. Accordingly, what the mind does or the activity of the mind was more important for psychological study than understanding what was in the mind or the content of the mind. He insisted that the mind be studied through the concept of activity as the fundamental base of empiricism in his book Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (Brentano, 1874). Brentano used the term empirical standpoint to distinguish his consistent and reasoned account of the mind from Titchener’s and Wundt’s descriptive nature of the mind. Brentano’s work on mental acts, known as Act Psychology, emphasized three key mental acts: recall, judging, and feeling. The first of these, recall, is remembering or having an idea of an object. The second act is in judging the object, which can also be thought of as the affirmation or the denial of the object, while the third act of feeling is forming an attitude toward the object. Brentano used the method of internal perception to study mental phenomena, which differed from Wundt’s method of inner observation (or introspection) in that it was a perception of psychological experiences that contain an object in themselves that is identical to an object outside itself. For example, a psychological experience consists of the first step, the act of seeing, and then the second step, the content of the seeing. In Wundt’s view only the second step was crucial, the content of the seeing; thus, it could only be studied through introspection. Although both Brentano’s and Wundt’s methods rested on the foundation of inaccurate human memory, Brentano justified its use by arguing that all science consults memory; thus, psychology is no different.

As Brentano continued his studies he struggled with the question of unity of experience. He was unsure if the total experience was a sum of the three key mental acts or if it was the relationship between the parts that created the experience. He concluded with some reservation, knowing that there was more work to be done in the area, that the mental acts or consciousness were unified, unique to the individual, and composed of all three (and even more as he later discovered) key mental acts. His work on these three specific types of mental acts and the formation of the self as a result of the integration of past, present, and intentions about the future became an inspiration for Gestalt psychology as well as psychoanalysis.

Oswald Külpe established the theory of imageless thought as another alternative to the psychology of Wilhelm Wundt. Külpe believed that some thoughts could be imageless in the absence of a sensation, feeling, or image as required by Wundtian psychology (Linden-feld, 1978). Interestingly, Külpe earned his PhD under Wundt in 1887 and later became one of Wundt’s major critics.

Once in his laboratory at Würzburg, Külpe pursued testing his theory by asking persons how they solve problems in terms of mental operations such as searching, discriminating, and categorizing information through the use of scrambled pictures, in hopes of developing an alternative to Wundt’s work utilizing the elemental building blocks of consciousness. Külpe believed that the ability to form a mental image was fundamentally different from the ability to remember an experience or recognize something. Examples of this concept include recognizing an individual when one is unable to form a mental image of the individual from memory alone, and the understanding of words such as philosophy and empiricism that have no direct mental image associated with them. Research on problem solving using mental set or einstellung illustrated a predisposition to respond in a given way. When subjects are made aware of certain elements of a problem to be solved, although other elements are present, the variability in the method of problem solving is greatly reduced. The mental set provided for an individual through instructional communication significantly impacts the method by which a person solves the problem at hand. Thus, for example, if instructed up front to listen primarily to what women say in a meeting rather than men, the accuracy of recall for the contributions of women speakers would be much higher than if no mental or einstellung was activated.

Külpe was successful in using experimental methods to decipher a difference between the elemental mental processes of Wundt and his study of the higher-order mental processes, such as problem solving, using mental sets.

E. B. Titchener’s psychology evolved from his two years of doctoral study under Wilhelm Wundt, which earned him a PhD in 1892. He was the primary force that introduced the Titchenerian brand of Wundtian psychology utilizing introspection in the United States. After completing his doctoral studies with Wundt in Leipzig, Titchener was offered a position at Cornell University in a relatively rural part of New York State, where he spent the remainder of his life as an Englishman who never became a U.S. citizen or immersed in American society. Titchener referred to his brand of psychology as structuralism as did William James (1842–1910). Titchner’s structuralism was a system of psychological thought intended to be modeled after more established sciences such as chemistry that employed observation or introspection as the method to search for the same three basic elements of consciousness as Wundt (i.e., sensations, feelings, and images or ideas).

Titchener’s Core-Context Theory of Meaning explained the assignment of meaning to sensations that were the core of the experience while the elicited fringe images from prior sensations and associations were the context. The context in which the sensation is experienced determines the meaning of the sensation; for example, a particular fragrance may elicit images of particular flowers thus giving meaning to the individual. This context or fringe image is necessary for the sensation to acquire meaning; thus, in the case of rapid speech in which a sensation is experienced but the context is not assessed it is possible to have sensation without meaning. It is also possible for meaning to be associated with meaningless sensations; for example, learning a new language. In this instance, meaning is associated with the currently meaningless sensation of vocalizing a new pattern of syllables.

Titchener’s view on the fundamental question of the basic elements of consciousness was one component of his work; he also studied the differences in levels of primary (involuntary) and secondary (voluntary) attention. His experimental studies on association that included the core-context of meaning theory also examined emotion and its relation to the James–Lange theory of emotion. Titchener did not agree with the James–Lange theory, which argued that emotions were a result of an organic or physiological experience. On the contrary, Titchener thought that affect was associated with earlier memories or images and that emotion was the result of a much more complex psychological process rather than primarily an organic cause.

Titchener, like Wundt, had many of his works published, namely, two books: Outline of Psychology (Titchener, 1896) and Experimental Psychology (Titchener, 1905), and many journal articles that he presented at meetings of the Society of Experimental Psychologists, which he established in 1904. Although he never attended a meeting of the American Psychological Association (APA), he established the Society of Experimental Psychology to concentrate on laboratory psychology as opposed to the APA’s focus upon both laboratory-based and applied psychology. Titchner served as the doctoral mentor for Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939), the first woman PhD psychologist, who studied comparative psychology.

The early psychophysicists such as E. H. Weber and G. T. Fechner pioneered the conceptual framework for an experimental psychology while Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt built upon their work and established the first psychology laboratory in a university setting. Over the years other changes have occurred in the protocol of the psychological experiment, such as providing participants with more information about the nature and purpose of the research they are involved in, the development of status differentials between the researcher and the subject, and an elaborate set of rules created to govern the permissible interactions among the researcher and participants.

There are three main models of psychological experimentation that have been employed over the years in the evolution of the psychological experiment; the Leipzig, the Parisian, and the American models. Danziger (1985) found that during the period 1875–1890, the Leipzig model was dominant, which basically involved no distinction between the roles of researcher and subject in an experiment. For example, the subject and researcher were often roles filled by the same person; this type of research was conducted in Wundt’s laboratory.

The hypnotic experiments conducted in Paris, France, by Charcot and others were different from the Leipzig model and the current American model. The Parisian model did not permit the interchange of roles between the experimenter and the subject as did the Leipzig model. This distinction by the Parisian model established the rigid patient–doctor relationship roles that are considered by some as critical for objective experimentation.

The American model of the psychological experiment differed from both the Leipzig and Parisian models by studying populations, samples, and groups of persons rather than focusing on individuals. In addition to this focus on aggregated data as opposed to individual data, the American model kept individual subjects anonymous and included only brief experimenter–subject contacts. Both the Parisian and the American models were modified from the original Leipzig model so that there is a strict difference in the function of the subjects (mainly as a data source) and the researcher (theoretical conceptualization, task administration, and publication of the study) to remove possible confounds from the experimental process, while the American model made it possible to identify psychological characteristics that could be applied across populations instead of being applicable primarliy to individuals.

Regardless of what the subject matter of psychology was according to Wundt, Brentano, Külpe, or Titchener, one thing is certain: they all experienced love. Although feelings were studied extensively in Wundt’s laboratory, the uniquely human experience of love was not studied. Thus, it was not until many years later that, like consciousness, some proposed that love consists of three elements that can be combined into different patterns yielding different types of love. Human love, which is a sought-after and desirable experience, is thought to be composed of three main elements, namely, intimacy, passion, and decision or commitment (Sternberg, 1986). According to the triangular theory of love (Sternberg, 1986), the element of intimacy is characterized by feelings of closeness, connectedness, and bondedness in loving relationships while passion is characterized by drives that lead to romance, physical attraction, sexual consummation, and related phenomena in loving relationships. Although both intimacy and passion lead to love, love is not complete without the final element of decision or commitment. In the short term this element is the decision to love someone else besides oneself and in the long term it is the commitment to maintain that love. In a relationship, two of these three components tend to be stable, intimacy and decision; however, passion tends to be unstable and comes and goes over the course of a loving relationship.

Loving relationships cover a wide variety of experiences other than consummate love, which is the result of the combination of all three elements but rather can include liking or romantic love as well. In liking, one experiences the intimacy component of love in the absence of passion and decision-commitment, whereas in romantic love the combination of intimacy and passion coexist, causing lovers to be drawn to each other not only physically but also with an emotional bond without commitment. Although it may appear that once consummate love is reached one has reached the pinnacle of love, it must be noted that reaching consummate love is easier than maintaining it. A beautiful piece by Louis de Bernieres described the phenomenon of maintaining consummate love, in his book Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (1994), as roots that have grown so intertwined that it is inconceivable to ever part even after the passion has burned away, whereas when the petals fall away and the roots have not intertwined the consummate love falls apart as well.

In this chapter, we have seen the influence of German psychologists on the development of psychology as an independent science. Ernst Heinrich Weber studied systematically the just noticeable difference (JND), which is summarized in his law K = Δ I/I. Gustav T. Fechner’s work, building upon Weber’s Law, is captured concisely by his psychophysical law that states that the correspondence between the perceived intensity of a stimulus increases by the addition of a constant (i.e., the JND) while the physical intensity must increase by a constant multiple or S = K Log R. Later psychophysical studies by S. S. Stevens demonstrated the limitations of Fechner’s Law.

Wilhelm Wundt built upon the earlier work of Weber and Fechner on the relationship between the mind and the physical world as a key component in the establishment of psychology as an independent science. Wundt, in the first psychological laboratory at Leipzig University, began the study of scientific psychology by focusing upon the subject matter of immediate conscious experiences composed of sensation, affect or feelings, and images. Wundt also studied mental chronometry, which measured the times of discrimination and choice mental processes.

Franz Brentano envisioned an alternative subject matter for psychology known as Act Psychology and Oswald Külpe studied imageless thought. Edward Bradford Titchener was responsible for introducing laboratory-based psychology to the United States under the name structuralism as well as developing his Core-Context Theory of Meaning.

As we have seen, Wundt’s conceptualization of the psychological experiment was a crucial first step in a series of three specific models that have been integral in the construction of the current psychological experiment. The Leipzig, the Parisian, and the American models were all derived from Wundt’s original protocol for the psychological experiment. We concluded this chapter by reviewing briefly the triangular theory of love. According to this theory, there are three elements of love: intimacy, passion, and decision or commitment, with different combinations of some or all of these three elements yielding different types of love.

Discussion Questions

- How did Gustav Fechner’s theory of psychological parallelism build on Ernst Heinrich Weber’s work in “just noticeable difference” (JND)?

- When studying immediate conscious experiences, what is the particular error that Wundt identified as being necessary to avoid?

- How did Wundt’s predecessors envision a different subject matter and method of study to understand psychophysics and consciousness?

- Who introduced structuralism to the United States and how did it draw upon Wundt’s voluntarism?

- What were the three key steps in developing the modern-day psychological experiment?

- According to the triangular theory of love, how do the three elements of love interact to produce the feeling of love?