II. CONFIGURATIONS IN PLAY AND DREAMS

Configurations in Play—Clinical Notes (1937)

Introduction

Listening to an adult’s description of his life, we find that a clear vista into his past is limited by horizons: one is the onset of puberty, with its nebulous “screen memories;” another the onset of the so-called latency period through which, in retrospect, memories appear inaccurate and obscure, if at all. In our work with children we meet another horizon, the period of language development. “The material which the child furnishes us,” says Anna Freud in her Introduction to the Technic of Child Analysis, “supplies us with many welcome confirmations of facts which up to the present moment we have only been able to maintain by reference to adult analysis. But . . . it does not lead us beyond the boundary where the child becomes capable of speech; in short, that time from whence on its thinking becomes analogous to ours.”1

Associations, fantasies, dreams lead in the analysis of the adult mind to the land beyond the mountains; in child analysis these roads lose their reliability and have to be supplemented by others, especially the sequences which occur spontaneously in the child’s play.

It seems to me, however, that when substituting play for other associative material we are inclined to apply to its observation and interpretation methods which do not quite do justice to its nature. We tend to neglect the characteristic which most clearly differentiates play from the world of psychological data communicated to us by means of language, namely, the manifestation of an experience in actual space, in the dynamic relationship of shapes, sizes, distances—in what we may call spatial configurations.

In the following notes it is hoped to draw attention to this spatial aspect of play as the element which is of dominant importance in the specificity of “Spiel-Arbeit.” These notes are based on observations made for the most part in the twilight of clinical experience, and must be supplemented by systematic work with normal or only slightly disturbed children. For although the adult who is not an artist must undergo the specific psychoanalytic procedure in order to reveal his unconscious in the play of ideas (a procedure which cannot easily be replaced for “scientific purposes” by less intimate and more systematic arrangements), the child in his play continuously and naturally “weaves fantasies around real objects.2”

I. “Houses”

An anxious and inhibited four-year-old boy, A, comes for observation. The worried mother has told us: (1) that he is afraid to climb stairs or to cross open spaces; (2) that as a baby he had eczema and that for eight months his arms were often tied in order to prevent his scratching; and (3) that until recently he continued to wet himself, with a climax at the time of a younger sister’s arrival.

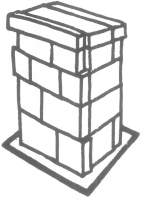

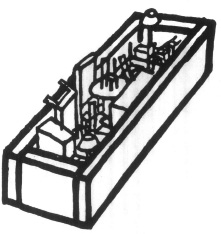

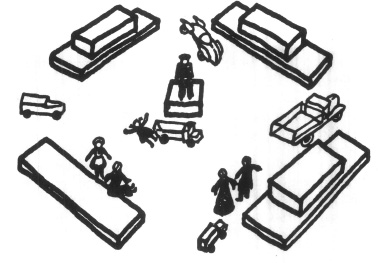

Let us see what he shows in the first minutes of play. Taking a toy house he places three bears close together in one corner. The father bear is lying in the bathtub, the mother bear is washing at the sink, while the baby bear is drinking water. The emphasis on water reminds us of the boy’s urinary difficulty. It also must mean something that the family is placed so close together, for he then arranges a group of animals outside the house equally close to one another. “Can you build a cage around these animals?” he asks me. Provided with blocks, he builds the “cage” shown in Figure 1 beside them—a house-form which on a normative scale of infantile house-building would belong to a much younger age. At five one knows that a house is “around something”; but A has forgotten the animals. He seems to use the blocks in order to express the feeling of being caged; he even places a small picture frame which he finds among the toys around the cage itself. Thus he is indicating in the content of his play what is libidinally the most important function of his body (urination) and in the spatial arrangement of the toys he expresses narrowness and the feeling of being caged, which we are inclined to trace to the early traumatic experience of being tied and to connect with his present fears of open spaces.

Figure 1

The boy then begins to ask persistently for many details about things in my room. When asked, “What is it you really want to know?,” he quiets down quickly and in a dreamy way turns a shallow bowl upside down and puts many marbles into the cavity of its hollow base. This he repeats several times, then takes one toy car after the other, turns it upside down and examines it.

Here, finally, we have behavior which belongs to the “putting-into” and “taking-out” type of play. By his persistent questions, and his silent examination of the toy cars, he seems to express an intellectual problem: “What is the nature of the underside of things?” This question arises because of the real conflict with the objective world which began when his mother gave birth to his sister, and represents the material most accessible for future psychoanalytic interpretation.

Beneath this level we see that two aspects of his “physical” experiences are expressed in his play. The one indicating strong interest in a pregenital (urethral) function will, during treatment, offer material for interpretation and will at the same time necessitate retraining. The earlier experience, the feeling of being caged, seems to be connected deeply with the impression which a seemingly hostile world has made on this child when he was still so young that his only method of defense was a general withdrawal. This must have so influenced his whole mode of existence as to create severe resistances to the analytical or educational approach.

The crux of this resistance is shown in the fact that for an abnormally long time A wanted to walk only in a walker. To be tied, once distasteful, proved in this instance to be a protection. We may assume that it is this double aspect of physical restriction, what it once did to his ego and how his ego is now using it which A expressed in his very first play constructions when he was brought to me, because of his fear of openness and height.

In stating that A expressed some quality of his experience of body and environment in the form of a cage-house, we imply not only that alloplastic behavior may reproduce the pattern of a traumatic impression and an autoplastic change imposed by it, but also that in play a house-form in particular may represent the body as a whole. And indeed, we read of dreams that: “The only typical, that is to say, regularly occurring representation of the human form as a whole is that of a house, as was recognized by Schemer.”3 As is well known, the same representation of the body by the image of a house is found throughout the gamut of human imagination and expression, in poetic fantasy, in slang, wit and burlesque, and in primitive language.

It would not, therefore, be important to lay much stress on the fact that in play, as well, a house-form can mean the body were it not that it is simple to ask a child to build a house, which often reveals the child’s specific conception of and feeling for his own body and certain other bodies. We seem to have here a direct approach through play to the traces of those early experiences which formed his body-ego.

This assumption led to interesting results when older children and even adults were given the task of constructing a house. Two extreme examples may suffice here.

A girl of twelve, B, had, at the age of five, developed a severe neurosis following the departure of her first nurse, who had been in the house from the time of the child’s birth. The nurse had spoiled B; for example, by allowing her to suck her thumb behind her mother’s back, and to eat freely between meals. During the mother’s frequent absences, B and her nurse lived in a world of their own standards; the nurse shared the secret of the girl’s first sex play with a little boy, while the girl was the first person to hear of it when the nurse became pregnant. B had just begun to puzzle about this fact when the parents discovered it and peremptorily discharged the nurse. Knowing nothing of the shared secrets, they were unaware that in so doing they were suddenly depriving the girl of a queer and asocial intimacy for which she was unable to find a substitute, especially since the mother set out to break, in the shortest possible time, all of the bad habits left from the nurse’s era. The result was a severe neurosis. When I saw the child for the time with no knowledge of the psychogenesis of her neurosis, I noted a protruding abdomen, and my first impression was, “She walks like a pregnant woman.” The secrets she had shared with her nurse and their pathogenic importance became apparent only later, however, when she confided that sometimes she heard voices within herelf. One voice repeated: “Don’t say anything, don’t say anything,” while others in a foreign language seemed to object to this command. She could save herself from the anxiety and the voices only by going into the kitchen and staying with the cook, obviously the person best fitted to represent the former nurse.

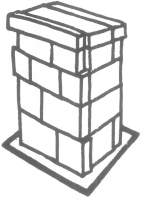

B first built a house without doors with a kind of annex containing a little girl doll (Figure 2a). Then she changed the house and built form 2b with many significant objects placed in and around it. In a vertical position we can see that the house-form could represent not only her own unusual posture but also the unconscious determinants for it, especially her identification with the pregnant nurse. The following superficial parallels (and I assume that deeper investigation of similar cases would reveal these as typical spatial elaborations of infantile body feelings) may be drawn:

CONSTRUCTION |

HOUSE |

BODY |

1 A little girl with a baby carriage goes to the country (to the cow). |

Outside the House: Where there is freedom. |

Head: Where she thinks she would like to go away: to the nurse who gave her everything to eat. |

2 A family around a table. |

In the Dining Room: Where the child has conflicts with the parents about eating. Where she is present when the parents (immigrants) talk about her in a foreign language. |

Inside the Body: Where one feels conflicts. Where she hears foreign voices quarrel. |

3 A cow in the country. |

Outside the House. |

In Front of the Chest: Where women (nurses) have breasts which give milk. |

4 Bathroom furniture behind thick protruding walls. |

In the Bathroom (thick walls): Where the secret is (the closed doors); the forbidden (nakedness, masturbation); the dangers (threats concerning masturbation); the bloody things (menstruation); the dirty (toilet activities). |

In the Protruded Abdomen: Where the secret is (the baby and it origin); that which is forbidden (the baby); the dangers (the growing baby); dirt (feces). |

5 A red racer and a truck in collision. |

Outside the House: Where the dangerous but fascinating life is, from which the parents try to protect the child. The accident. |

Under the Abdomen: Where it seems a girl can lose something, since boys have something there and girls do not. Where people say girls will bleed. Where men do something to women. Where babies come out, hurt women and sometimes kill them (the nurse died shortly after childbirth). |

The doorless house not only pictures the child’s posture, and shows the unconscious idea of having incorporated the lost nurse, it seems also to indicate that part of her body which is firmly entrenched within the fortress of ego-feelings, as distinguished from what are only thoughts and fears concerning the body, felt as “outside”: the expectation of breasts and the fear of menstruation, of which she had been warned.

Figure 3

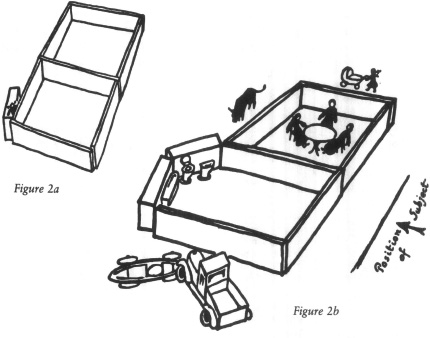

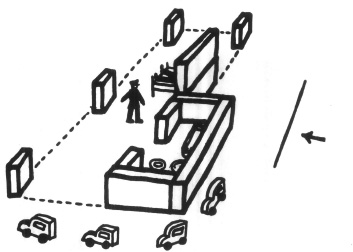

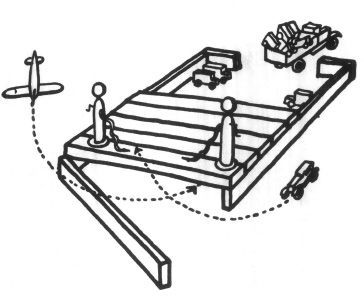

As a further example justifying our looking at the house from different positions and our assumption that the walls reveal something of the builder’s body-ego, the following is of interest: A young schizophrenic man, C, a patient in the Worcester State Hospital, built the house shown in Figure 3.

He said it was a screen house all around, except for the back part. This patient complains of having no feeling in the front of his body. Ever since he was the “victim” of a spinal injection, he claimed that he suffered from a certain electric feeling drawing down from his spine to the rectum, and from difficulties in urination. He walked in a feminine manner with protruding buttocks. One may recognize this posture in the house-form. C strengthened that part of his house which corresponded to the spine of his body by placing two blocks on top of one another, and he furthermore placed walls around one room only (the bathroom) which in position corresponded to his buttocks. The cars are again put at the place corresponding to that of the urethrogenital region on the body and their arrangements suggested a symbolizing of the patient’s urethral symptoms (he could urinate only “in bits”).

In children without marked orality and adults without psychotic symptomatology, I have not found such detailed parallels between posture and house-forms as those of cases B and C. In laying out the play of their houses, they stood over it in such a way that the house, as compared with a body, was “dorsal recumbent,” and therefore might be said to represent more a baby’s than an adult’s body-ego. By rotating the diagrams, we recognized in the same constructions the subject’s posture which could be interpreted as expressing an identification with a mother image. It seems that the phenomenon of most striking similarity between house-forms and posture is based on the introjective and projective mechanisms of orality, which must be assumed to be active in the establishment of the body-ego in earliest childhood.

Figure 4

In attempting to find similar relationships between the growing organism and the typical block-building of normal children, one will have to be prepared for a much less striking and more sophisticated spatial language in which more emphasis is laid on structural principles than on similarity of shape. Interestingly enough, from Ruth Washburn’s nonclinical material, only children with strongly emphasized orality produced parallels between body and house at all similar to B’s and C’s constructions. The house-form shown in Figure 4 was built by D, who was a fat, egoistic boy of five, a heavy eater. He explained that room 1 is the entrance, room 2 the living room. About room 3 he said: “This is where the water goes through; it is not going through now, though.” He added, “There is a drawbridge; when boats come, you pull it up.” D’s eagerness to “take in” and his reluctance “to give away” are well illustrated by the large opening of the entrance and the complicated closing arrangements at the other end, where water and boats go through the house.

Figure 5

Returning to analytical material from children, we select a house-form of a boy of eight, E, which, in its primitiveness reminds us of A’s construction. Upon my advice, E had been brought home from a special school where, diagnosed as defective, he had spent half his life. The problem was to find out whether with psychoanalytic help he could resume ordinary home and school life. When he came to his first hour, tense and hyperactive, he remained in my office just long enough to build a house with the blocks he found there (Figure 5). This house, primitive and without doors (like A’s house), was filled chaotically with furniture. When, after a few minutes, he ran away shouting that he never would come back, he left behind him nothing but this doorless wall, dividing an outside from a chaotic inside.

I accepted this theme of a closed room and devoted the next few appointments to a short discussion of whether he had to stay and for how long, and whether or not the door of my room would remain open. On the second day he did not want to stay, although the door was not closed. He was immediately dismissed, sooner in fact than he really wanted to go. On the third day he stayed for a few minutes; on the fourth, he asked whether he could stay the whole hour; but when the door was closed, he was driven at once to manifestations of anxiety. He had to touch all the little buttons or protrusions in the room. I made the remark that it seemed as though he had to touch everything, and that he gave me somewhat the impression that for touching something (I did not know what) he expected to be put in jail. His blushing showed that he understood. Like most children who do not quite understand why they are detained with problem children, he had associated the sexual acts of some of them with his own sins and with “being a problem” in general. What he did not remember was that in his infancy, he, like A, had been tied when he rocked his bed (muscular masturbation with genital and anal elements).

The next day he asked questions, all of which began with, “Who has the power to . . .” and since I had heard from his mother that at home he was greatly worried because she wanted to get rid of a soiling cat, I told him that his mother had asked me about the cat and that I had told her she had no right to send the cat away. One should give cats and children a chance before one tries to get rid of them. He sat down and asked softly, “Why do I get so furious?”—and after a long silence, “Why do boys get so furious?” To every reader of Anna Freud’s Introduction to Child Analysis it is obvious that this question shows a concern which is important for the therapeutic situation. While his defiant behavior at first had announced that he did not wish to be sent away or kept anywhere because of his violent aggression, his question showed insight, confidence, and a readiness for conversation. I asked him why he thought boys were “furious.” “Maybe because they are hunters . . . ,” he suggested.

Then we began to compare what boys wanted to be with what girls wanted to be, and to make out a written list containing on the one side the toys which boys liked: (streamline train, speedboat, gun, bow and arrow); and on the other those preferred by girls: (doll, doll’s house, doll clothes, carriage, basket). The one group could be summed up under the symbol of an arrow and the other under that of a circle. I asked him whether this did not remind him of a certain detail in the difference between a boy’s body and a girl’s body. “That is why,” he said thoughtfully, “I call my streamline train Johnny Jump-up.’ ” So we talked about the psychobiological implications of having a penis, the fear of the impulses connected with its possession and the fear of the possibility of not having one. He seemed somewhat relieved.

The next day the cat interfered again. Her regression as to toilet habits had, to say the least, been overdetermined: she was, as everybody at home now agreed, pregnant. But no one could tell just when the kittens would arrive. The questions when do the kittens want to come out and when will they be allowed to come out, became the patient’s main interest in life. Unfortunately, his unlucky father and his even more unlucky analyst happened to tell him different periods for the duration of a cat’s pregnancy. He wondered seriously if God himself was sure when the kittens should come out.

Figure 6

One day, having left the office for a moment, I returned to find E all rolled up in the cover of the couch. He remained there half an hour. Finally, he crawled out and sat beside me. I began to talk about the kittens kept in the cat, children kept in special schools, babies tied in their beds and stillborn babies kept in glass jars. (I knew that not long ago he had seen such an exhibit, and that someone had jokingly told him it was actually a stillborn brother of his.) He probably could not remember, so I added that when he was a baby his father had tied him to his bed because he had rocked so loudly during the night. He blushed and when he got up from the sofa I noticed that he had tied his hands and feet before rolling himself up in the cover.

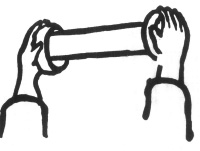

The toy which he subsequently chose for his first concentrated play in my office was a bowl (Figure 6), a piece of which was broken off. (It will be mentioned here in connection with several cases.) He turned it around to “shoot” marbles into it. For a while we competed at this game, until another cloud came up over the horizon.

As to Figure 5, one can see now how many different phenomena it “meant,” all of them similar only in the possession of strong walls, no doors and chaos within—attributes at one and the same time of his tension of mind and body; his experience of being tied in bed; his concept of the female body as a claustrum; his experience and expectation of being kept at a place far from his family; and last, but not least, my office. In beginning our relationship with the “spatial” discussion of this last mentioned “cage” (office), we succeeded in lining up all his cage-conceptions before an interpretation which included them all was given. The play with the marbles, then, was the first free, though not yet quite uncompulsive, expression of that phallic tendency which, in its unsublimated form, had given him the impulse “to do something to women”—and the fear of “being put in jail.” Soon afterwards his intrusive tendencies began to possess him entirely in the sublimated form of “scientific” curiosity. Appealing for comradely help from his father, and equipped with an extensible telescope, he entered Mother Nature’s secluded areas and investigated birds’ nests and other secrets.

Figure 7

In analyzing the full significance of a certain house-form in play, as in the evaluation of a well-known dream symbol, we need the aid of biographical material. On the other hand, the form of the house itself and the play activity provoked by it will sometimes tell at once where on the scale of object-relationships our small patient can be assumed to be; whether absorbed in narcissistic orality like B, C and D, or restricted by an early psychophysiological experience like A and E, or whether he has achieved a fearless, clear object-relationship, expressed in unrestricted functional play as in the case of F, which follows.

F, a boy of five, was not a patient—he was occasionally brought into the office to play for an hour (a pleasant procedure of regular, preventive observation). At the time of the visit to which I am referring, F talked at home in a rather unrepressed way about impulses towards his mother’s body. She would, he hoped, let him put the next baby into her.

In my office he built a house (Figure 7), and played contentedly, without showing compulsion or anxiety, for a whole hour. Trucks drove into the backyard to unload dozens of little cars which were lined up. A little silver airplane and a red car were the favorites, and had individual rights: when the airplane majestically neared the house, the front door was opened to permit it to glide right in. The red car sometimes jumped on to the roof, to be fed by one of the two gasoline tanks stationed there. His remarks at home and his interest in his parents’ bodies (so usual for this inquisitive age) justify the interpretation that F played with the house as his fantasies played around his mother’s body. The little red car is fed by the two tanks just as F’s sister drinks from the mother’s breasts. The airplane enters the house from the front as his father’s erect penis enters the mother’s body. And his loading and unloading of trucks that like most children he has concluded that there are innumerable babies in the mother’s body and that they are born through the rectum, the orifice through which the contents of his own body pass.

One was reminded of Santayana’s recent description:

A boy at the age of five has a twentieth century mind; he wants something with springs and stops to be controlled by his little master-ego, so that the immense foreign force may seem all his own, and may carry him sky-high. For such a child, or such an adventurous mechanic, a mere shape or material fetish, like a doll, will never do; his pets and toys must be living things, obedient, responsive forces to be coaxed and led, and to offer a constant challenge to a constant victory. His instinct is masculine, perhaps a premonition of woman: yet he is not thinking of woman. Indeed, his women may refuse to satisfy his instinct for domination, because they share it; machines can be more exactly and more prodiciously obedient.4

II. Psychoanalysis Without Words

(ABSTRACT OF A CASE-HISTORY)

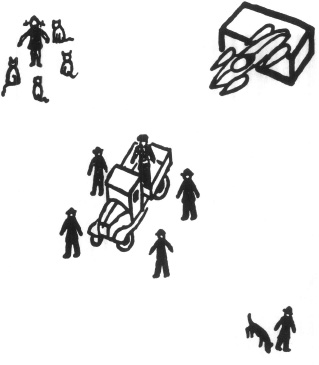

A little girl, G, two and one-half years old, had stopped looking and smiling at people and had ceased developing in her play. She had not learned to say a word or to communicate in any way with other children. Only occasionally, and then in connection with some tense, compulsively repeated play, did her pretty face lose its monotonous and melancholy expression. At such moments her excited sounds were strangely gutteral and were produced by noisy inhalations. No diagnosis meant much at this stage. The question was: Could one make contact with her at all? Could one reawaken her interest in this world?

Upon my first visit to her, one single fact induced me to make the trial. As she approached me slowly, coming down a stairway, she did not look at me directly but around me in concentric circles. She did not fail to see me, as had been supposed, but definitely avoided doing so.

My first subsequent observations revealed that her spells of excitement showed a mixture of pleasure and anxiety. I noticed this first during a spell which took place as she was banging a door, which in opening and closing touched a small chain that hung from an electric light. However, such “spells” could also occur when she was quiet. She would suddenly look out of the corners of her eyes at an extreme angle, focusing them far away, usually at the brightest point in the surroundings; then she would twist her hands almost convulsively and produce gutteral sounds, half like crying, half laughing.

She seemed never to have made any of the usual pre-language sounds; nor had she ever licked things as other children do, nor bitten anything. She would urinate only once in twelve or twenty-four hours, and often had bowel movements only once in forty-eight hours. Her room was overclean and her nurse seemed not without anxiety in regard to these matters.

When I heard this, and saw her exhibit the same excitement while simply throwing a ball again and again between a piano stool and a piano, I concluded that she had experienced training as a trauma, which in turn has been connected somehow with unknown traumata of her earlier life. I first tried to approach this symptom by suggestive play. Disregarding her, since she avoided looking at me, I threw stones into some old “potties” for almost an hour. When I then left, and observed her from a place where she could not see me, she played around these potties in concentric circles which grew narrower and narrower. Finally she dropped a stone in a potty, laughed heartily and loudly, and said clearly, “a-ba-ba-ba-ba.” During the succeeding days her toilet habits changed completely, whether as a result of this simple suggestion I do not know, but an immediate relief of general tension was obvious.

We then tried by mild suggestion to influence her playing and her playful movements in space. Not only had she fortified her position against the outer world by not looking at people, not listening, not eating unfamiliar food, and by holding back urine and feces, but she behaved on the whole as if something actually inhibited the movements of her body in space. Her legs and arms were tense and stiff, so much so that a neurological disturbance was suspected and she was examined, with no findings to indicate disease. Even when ample space was at her disposal, she seemed to imagine limits and boundaries where she stopped suddenly, as if confronted with a fence or an abyss. It was an imaginary noise at a certain distance upon which she then focused her attention with an expression half anxious, half delighted. I was interested to see at what limit freer play and freer physical movement would be stopped by a real anxiety or end in the manifest excitement described above. If she threw things, I would try to induce her to throw them further; I would take her hand to run with her, to jump down or to climb steps—always somewhat more quickly or extensively than she would dare to do alone.

While I attempted to help her expand the limits of her expression, it became obvious that there was a correlation between the functions of focusing on objects, grasping objects, aiming at things, biting into things, forming sounds, having sufficiently large bowel movements, and touching her genitals. The manifestation of increasing aggressiveness in one of these functions was accompanied by similar improvements in the others; but when a certain limit was reached, anxiety inhibited all of them. A sudden large defecation on the porch was followed by severe constipation and regression in all functions, and a “talking” spell of four hours one night, in which she seemed to be able to talk all the languages of Babel, but unable to single out English from the confusion, had the same effect.

The first word she suddenly used—pronouncing it quite clearly—showed that it had been right to assume an early traumatic experience. While banging a door she looked far away into the sky and exclaimed (obviously imitating an anxious adult, quite in the fashion of a parrot), “Oh dear, oh dear, oh dear.” On another occasion, she said clearly several times, “My goodness.” A few days later I saw her pick out of a potty numerous stones and blocks which smelled of paint, and lick them. When I softly said, “Oh dear, oh dear,” she vigorously threw the potty away, as if remembering a prohibition.

On the other hand, nothing could excite her more than having a bright, shining pinwheel moved quickly toward her face. I cannot report here all of the details of her play, which finally pointed to the following elements as possible aspects of a traumatic situation in her past: looking through bars (like those of a crib?); a light moving quickly toward her face; a light seen at a certain angle; a light seen far away; traumatic interference with licking and with play somehow connected with defecation. These corresponded to two of the definite

fears she had occasionally manifested, i.e., of a light in the bathroom and of a traffic light blinking some hundred feet away from her window. She had also been terrified by the fringes of the covers on her parents’ beds, a fear which seemed unconnected with this, until the chains of the lights which fascinated or frightened her proved to play an important role.

I then visited the hospital where she had been born. The most critical period of her short life had been its first few weeks, during which her mother had been too ill to nurse her for more than two days. The baby developed an almost fatal diarrhea. Not much was known about this period and her special nurse had left the country.

Another nurse, helping me to study the lights in the hospital, suddenly said, “And then we have another lamp which we only use with babies who have severe diarrhea.” She demonstrated the following procedure with its clear parallels to the child’s play behavior. The baby is laid on its side so that the lamp, which is put as near as possible to the baby’s sore buttocks, can shine directly on them. The baby then must see the lamp from approximately the angle which this child’s eyes always assume when she is preoccupied with her typical day-dream. The lamp has a holder which can be bent and the full light could then shine on the baby’s face for a moment as the lamp is being adjusted. When this has been done, the lamp is covered so that it is, so to speak, in the bed. For the baby, then, the light is where the pain is.

The discovery of this traumatic event from the second week of her life helped us to meet a situation which arose when the child suddenly became frightened of a lamp in my office, stopped drinking milk at home and began, wherever she was, to play at being in bed. She would build a kind of cave out of the cover of my couch, crawl into it, and, terrified but fascinated, would look towards the dangerous light. We began to play with lights. Since at the time she liked all things which could be spun around quickly, I would put a light underneath the cover, presumably where the hospital lamp had been, and would spin it around. She began to love lights, and when she smiled for the first time at the light that she had been afraid of, she said, “ma-ma-ma-ma.” At the same time her motor coordination improved so much that when the lamp above her bed had to be unscrewed because she played with it too much she could rock her bed across the room in the dark to pull another lamp chain.

At this point in the treatment the mother remembered another important part of the child’s earliest history. In the third month of the child’s life, when she had left the girl to take a trip, she had given instructions that an electric heater be turned on while diapers were being changed. After her return she was told that all through this month, dynamite had been used to blast rocks in the vicinity and had terrified the whole neighborhood. The baby, being upset already by the nervousness of the adults, had been further terrified when one day the electric heater suddenly exploded beside her. Here we have the connection between the light where the pain is and the light where the noise is. The flashing traffic light several hundred feet away, of which she consequently was afraid, apparently was a “condensation” of the exploding light near at hand and the terrifying noises at a distance.

After she had learned to play with lights without fear, we attempted to extend further the radius of her activities, and gave her hard toast in order to induce her to bite. She refused—and presently reacted with a show of fear on seeing a tassel hanging from the girdle of her mother’s dress. At the same time, she began to bite into wooden objects. Having observed in her a similar fear of a lamp chain (usually, as I pointed out, the object of traumatic play) directly after she had first seen two little boys naked, I inquired whether, and how much, she could have seen of her father’s and mother’s bodies. Her fear spread to all objects which had tassels or fringes or were furry or hairy, when they were worn by a person. When offered her mother’s belt to play with, she touched and finally took it between thumb and forefinger as if she were taking a living and detestable thing, and threw it away (with an expression much like that occasionally shown by women when they report a snake dream). When by playing with the fringe repeatedly, she had overcome her fear of it, she began staring down into the neck of her mother’s nightgown, focusing her fascinated attention on her breasts. When we add to these observations the recollection of how she had formerly looked in a concentric circle around people, supposedly not seeing anybody at all, we may reconstruct one more of the traumatic impressions which were probably factors in arresting her development. We may assume that as a small child when seeing her parents undressing on a beach, she had experienced a biting impulse toward the mother’s breasts and (a not uncommon displacement) the father’s penis.5 What this meant to her becomes clear when we remember the first two traumatic events we were able to uncover. The first had been the experience of intestinal and anal pain in association with light during the frustrated sucking period. The second was the experience of noise (the blasting) and exclaiming women (“Oh dear,” “My goodness”) in connection with the electric heater during the onset of the biting period. (Other material suggested that the nurse had exclaimed in a similar way when she once found the child playing with feces which she was about to put into her mouth.)

No doubt from the very outset this child had not been ready to master stimulations above a certain intensity. On the other hand, some meaning could be detected in her strange behavior and under the influence of our play and of simultaneous change of atmosphere in a now more enlightened environment, the child’s vocalizations approached more nearly the babble of a normal child before it speaks. She began to play happily and untiringly with her parents and to enjoy the presence of other children. She had fewer fears, and she developed skills. This newly acquired relationship to the object world, though a precondition of any reorientation, was, of course, only a beginning.

III. Pregenitality and Play

A. CLINICAL OBSERVATIONS

1.

In her article Ein Fall von Ebstörung6 [A Case of an Eating Disorder] Edith Sterba reports the case of a little girl who began to hold food in her mouth, after having been trained to release the feces which for an annoyingly long period she had preferred to retain in her rectum. This food she would turn around and around until it formed a ball, whereupon she would spit it out, thus using or rather misusing, the mouth to execute an act which had been inhibited at the anus.

A zone of the body with a specific muscular and nervous structure, the typical function of which is to accept, examine and prepare an incoming object for delivery to the inside of the body, is here used instead to hold for a while in a playful manner, and then return the object to the outside. This act resembles the anal act which it replaces only as a “gesture,” but without any functional logic. Such as “unnatural” use of a substituted zone is one form of what is called displacement. In this case it implies a partial regression, since the mouth precedes the anus in the erogenous zones sequence, and offers the specific tactual pleasure sought after at an earlier period. It is hard to understand psycho-physiologically that a zone can replace another zone of different neurological quality and location, and serve dramatically to represent its function. Psychoanalysts have accepted the interrelationship of these interchangeable zone-phenomena as being libido economical. Physiologists and psychologists in general are for the most part not even aware of the phenomena as a problem.

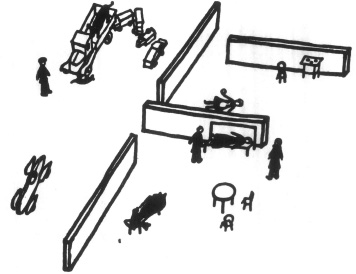

Figure 8

What interests us most in this connection is the relationship to play of such displacements from one organ to another. Most children, instead of displacing from one section of their own body to another, find objects in the toy world for their extrabodily displacements. If, in a moment of deep concentration in play, the dynamics of which are yet to be described, a child is not disturbed from within or without, he may use a cavity in a toy as a representative of a cavity in his own body, thus externalizing the entire dynamic relationship between the zone and its object.

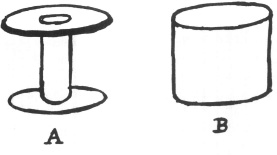

Between displacements within the body (habits, symptoms) and the free external displacement in play, we find various arresting combinations. A little boy, H, two-and-one-half years of age, who struggled rather belatedly against enuresis, began to take to bed with him little boxes, which he held closed with both hands. When a box would open during the night, sometimes apparently with his unconscious help, he would cry out in his sleep, or awaken and call for someone to help him close the box. Then he would sleep peacefully, though not necessarily dry. But he continued to experiment. During the day he looked around for suitable boxes—obviously driven by an urge to materialize an image of “closedness.” Finally he found what seemed to fit the image: it was a cardboard cylinder which had been the center of a roll of toilet paper, and two cardboard caps from milk bottles, which he put over the openings of the roll. (See Figure 8.) All through the night he would try to hold this arrangement firmly together with both hands—as an animistic guardian of the retentive mode. But no sooner had his training achieved a relative success in closing his body during sleep, then he began, before going to sleep, to throw all available objects out of the window. When this was made impossible, he stole into other rooms and spilled the contents of boxes and bottles on the floor.

Clearly, the first act, namely, holding a closed box as a necessary condition for sleep, resembles a compulsive act originating in the child’s fear of being overpowered by his weakness to retain or his wish to expel. Emptying objects, on the other hand, or throwing them out of the window is “delinquent” and the result of the fear of being overpowered by the claims of society to which he surrenders the zone but not the impulse. The impulse begins an independent existence.

To prevent the little boy from throwing things out of the window, it was opened from the top. Thereupon he was found riding on it, leaning out into the night. I do not think he would have fallen out; he wanted only to show himself “master of openings,” as compensation for the surrender of the free use of his excretory openings to society. When, in consequence, his mother kept his window closed until he was asleep, he insisted that the door should be ajar. At an earlier stage, the same boy, as he was learning to control his bowel movements, had gone through a short period of excessive running away. Thus not only sections of one’s body and toys, but also the body as a whole in its spatial relationship to the whole room or to the whole house may serve the displaced impulse in various degrees of compulsive, naughty, or playful acts.

I may refer again to the wooden bowl which I mentioned on page 87 (see Figure 6). After a piece had been broken off, this bowl proved to be of manifold use to various children. They used it with deep concentration and with endless repetitions. As noted in page 79, A, curious and much restricted, turned it upside down to fill its hollow base and look at it; F, reassured about his phallic aggressiveness, used the opening, as thousands of boys at certain ages do, as a goal for his marbles; G, over-retentive, did not “retain” marbles in the bowl, but filled it again and again in order to spill them excitedly all over the floor. Similarly, a girl of three, who was fighting desperately against soiling herself, did not spill, but asked for the broken-off piece to close the bowl tightly, reminding us of the boy H with his animistic retention boxes. Thus we see the impulses appearing in play as the advance guard or rear guard of new sublimations.

It is conceivable that a form such as this bowl, as it is used by children of various age groups, could also prove of experimental value. We must keep in mind, however, that units of play behavior, like parts of dreams or single associations, seldom have independent meaning value. To know what a certain configuration in a child’s play means, we should know the contemporaneous changes in his growth, his habits, his character and his concepts of others.

Figure 9

2.

Let us look at an individual who showed pathological oscillation in the pregenital sphere, and let us place a specific bit of play in the center of our observational field.

At a certain period in his treatment, J, a boy of eight, untiringly repeated the following play: A caterpillar tractor slowly approached the rear end of a truck, the door of which had been opened. A dog had been placed on the tractor’s chain wheels in such a way that he was hurled into the truck at the moment the tractor bumped into it. (Figure 9.)

Symptom. In a very specific way, J had failed to respond to toilet training. Dry and clean when he wished to be, he had nevertheless continued to express resistance against his mother by frequent soiling (as much as three times a day), an act which became a perverted expression of his highly ambivalent feelings about the other sex. In school, when angered by certain girls by whom he would feel seduced, he would take their berets to the toilet and defecate into them. His masturbatory habit consisted in rubbing the lower part of his abdomen, which caused genital excitement at first, but ended in defecation.

First treatment. The psychiatrist who first treated the boy was amazed to find that he offered “unconscious” material of a sexual and anal nature in a never ending stream. As the naïve preconception in some child guidance clinics would express it, the boy was a real “Freudian” patient. But the psychiatrist was well aware of the fact that the patient did not really respond to the explanations for which he seemed to ask. This was probably due to the fact that in being voluble he did not communicate with the therapeutic agency in order to get cured, but cleverly “backed out” by regressing to a new kind of oral perversion in “talking about dirty things.”

Second treatment. When the boy’s masturbation increased, it had been thought necessary to circumcise him, under the assumption that it was a slight phimosis which, though stimulating him genitally, did not allow him to have a full erection and led his excitement into anal-erotic channels. Simultaneously, he was subjected to an encephalogram. Following this, the boy had stopped soiling entirely; but he also underwent a complete character change. He talked little, looked pale, and his intelligence seemed to regress—symptoms which are apt to be overlooked for some time because of the specific improvement in regard to a socially more annoying symptom. In this case, the closing up was nothing but a further regression, an outwardly more convenient but in fact more dangerous retreat into orality (as was also shown by his excessive eating) and into a generalization of the retentive impulse. In consequence, his behavior soon gave rise to grave concern, and when he was first referred to me, I was doubtful as to the therapeutic reliability of his ego, which either seemed to be no longer or perhaps never to have been secure.

Psychoanalytic treatment. The first barrier which psychoanalysis was forced to attack was the castration fear, which, after the circumcision, had suppressed his soiling without ridding him of the impulse. Expecting new physical deprivations, the boy would appear equipped with two pairs of eyeglasses on his nose, three knives on a chain hanging out of his trousers, and a half dozen pencils sticking out of his vest pocket. Alternately he was a “bad guy” or a cross policeman. He would settle down to quiet play only for a few moments, during which he would choose little objects (houses, trees and people) no larger than two or three inches high, and make covers for them out of red Plasticine. Suddenly he would get very pale and ask for permission to go to the bathroom. When consequently the circumcision was talked over and reassurances given for the more important remainder of his genitals, his play and cooperation became more steady.

His first drawing pictured a woman with some forms enlarged so as to represent large buttocks. In violent streaks he covered her with brown paint. It was not, however, until his castration fear had been traced to earlier experiences that he began to look better and to play with real contentment.

J had witnessed an automobile accident in which the chief damage was a flat tire. In describing this and similar incidents to me he almost fainted, as he had also done merely while enlarging and protecting the little toys with covers of Plasticine. In view of his anxiety, I pressed this point. He felt equally sick when I asked him about certain sleeping arrangements. It appeared that he had seen (in crowded quarters) a man perform intercourse with a woman who sat on him, and he had observed that the man’s penis looked shorter afterwards. His first impression had been that the woman, whose face seemed flushed, had defecated into the man’s umbilicus and had done some harm to his genitals. On second thought, however, he associated what he had seen with his observations on dogs, concluding that the man had, as it were, eliminated a part of his penis into the woman’s rectum out of which she later would deliver, i.e., again eliminate, the baby. His castration fear was traced to this experience, and the enlightenment given that semen and not a part of the penis remained in the woman.

First play. His first concentrated skillful and sustained play was with the tractor and the truck. At that moment I made no interpretation of it to him, but to me it indicated that he wanted to make sure by experimenting with his toys that the pleasant idea of something being thrown into another body without hurting either the giver or the receiver was sensible and workable. At the same time, his eliminative as well as his intrusive impulses helped him in arranging the experiment. Finally he showed that his unresolved anal fixation (no doubt in cooperation with certain common “animalistic” tendencies and observations) did not allow him to conceive of intrusion in any other way than from behind. From his smearing of the woman’s picture with brown paint to this game, he had advanced one step: it was not as before brown stuff or mud which was thrown into the truck, it was something living.

Technical consideration. Melanie Klein, in her arresting and disturbing book The Psychoanalysis of Children has given the significance of an independent, symbolical unit to the fact that in a child’s play motor cars may represent human bodies doing something to one another. Whether or not this is unreservedly true in its exclusively sexual interpretation has become a matter of controversy. Probably the question cannot be given any stereotyped answer. Symbolism is dangerous because it distracts attention from the imponderables of interpretation. No doubt, any group of mechanical objects, such as radiators, elevators, toilet and water systems, motor cars, and so on, which are inanimate but make strange noises, have openings to incorporate, to retain, and to eliminate, and finally are able to move rapidly and recklessly, constitutes a world well suited to symbolize one of the early concepts which the child has of his body as he develops the agencies of self-observation and self-criticism. Encountering in himself a system of incalculable and truly “unspeakable” forces, the child seeks a counterpart for his inner experience in the unverbalized world of mechanisms and mute organisms. As projections of a being which is absorbed in the experiences of growth, differentiation, and objectivation, they are not as yet systematically described. Their psychological importance certainly goes beyond sexual symbolism in its narrower sense.

Likewise, play is much too basic a function in human and animal life to be regarded merely as an infantile substitute for the verbal manifestations of an adult. Therefore one cannot offer any stereotyped advice as to the form or time when interpretations of play are to be given to a child. This will depend entirely on the role of play at the specific age and in the specific stage of each child patient. In general, a child who is playing with concentration should be left undisturbed as long as his own anxiety allows him to develop his ideas—but no longer. On the other hand, some children, becoming aware of our interest in play, use this to lead us astray and away from quite conscious realities which should be verbalized. We are not in possession of a theory embracing the dynamics of play and verbalization for different ages in childhood. We do not want to make the child conscious of the fact that play as such means something, but only that his fears, his inability to play playfully, may mean something. In order to do this, it is almost never advisable to show to the child that any one element in his play “means” a certain factor in his life. It is enough after one has drawn one’s own conclusions from the observation of play, to begin to talk with the child about the critical point in his life situation—in a language the sense of which is concrete to a child at a specific age. If one is on the right track, the child’s behavior (through certain positive and negative attitudes not discussed here) will lead the way as far as it is safe. No stereotyped imagery should lure us beyond this point.

Return of the impulse. Outside the play hours, the eliminative impulse typically made its reappearance in J’s life in macrocosmic7 fashion and at the periphery of the life space: the whole house, the whole body, the whole world were used for the representation of an impulse which did not yet dare to return to its zone of origin. In his sleep, he would start to throw the belongings of other people, and only theirs, out of the window. Then, in the daytime, he threw stones into neighbors’ houses and mud against passing cars. Soon he deposited feces, well wrapped, on the porch of a hated woman neighbor. When these acts were punished, he turned violently against himself. For days he would run away, coming back covered with dirt, oblivious of time and space. He still did not soil, but desperation and the need for elimination became so all powerful that he seemed to eliminate himself by wild walks without any goal, coming back so covered with mud that it was clear he must have undressed and rolled in it. Another time he rolled in poison ivy and became covered with the rash.

Resistance. When he noticed that, by a slowly narrowing network of interpretations, I wanted to put into words those of his impulses which he feared most, namely, elimination and intrusion in their relationship to his mother, he grew pale and resistive. The day I told him that I had the impression there was much to say about his training at home, he began a four-day period of fecal retention, stopped talking and playing, and stole excessively, hiding the objects. As all patients do, he felt rightly that verbalization means detachment and resignation: He did not dare to do the manifest, but he did not want to give up the latent.

Return of symptom. He did not live at home at this time. After many weeks, he received the first letter from his mother. Retiring to his room, he shrank physically and mentally, and soiled himself. For a while he did this regularly whenever his mother communicated with him.8 It was then possible to interpret to him his ambivalent love for his mother, the problems of his bowel training, and his theories concerning his parents’ bodies. It was here also that his first free flow of memories and associations appeared, allowing us to verbalize much that had been dangerous only because it had been amorphous. Interestingly enough, after the patient understood the whole significance of the eliminative problem in his life, the eliminative impulse, in returning to its zone did not flood, as it were, the other zones. Verbalization did not degenerate to “elimination of dirt” this time, as in the previous psychiatric treatment.

Sublimation. One day he suddenly expressed the wish to make a poem. If there ever was a child who, in his make-up and behavior, did not lead one to expect an aesthetic impulse, it was J.9 Nevertheless, in a flood of words, produced during an excitement similar to that which had been noticeable when he had talked about dirt to the psychiatrist, he now began to dictate song after song about beautiful things. Then he proposed the idea, which he almost shrieked, of sending these poems to his mother. The act of producing and writing these poems, of putting them into envelopes and into the mailbox, fascinated him for weeks. He gave something to his mother and it was beautiful! The intense emotional interest in this new medium of expression and the general change in habits accompanying it indicate that by means of this act of sending something beautiful to his mother, part of that libido which had participated in the acts of retaining feces from women and eliminating dirt to punish them had achieved sublimation. The impulse had found a higher level of expression: the zone submitted to training.

3.

In part 1 page 94, I gave an example of what different children may do with one toy; in part 2, an example of the therapeutic significance of one play-event in a child’s life. I would like to add a word about a child’s behavior with different play-media:

A child playing by himself may find amusement in the play world of his own body—his fingers, his toes, his voice, constituting the periphery of a world which is self-sufficient in the mutual enchantment of its parts. Let us call this most primitive form of play auto-cosmic. Gradually objects which are close at hand are included, and their laws taken into account.

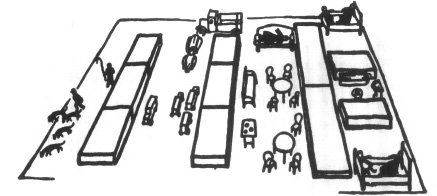

If, at another stage, the child weaves fantasies around the reality of objects, he may construct a small toy world which is dominated by the laws of his own growing body and mind. Thus, he makes blocks “grow” by placing them on top of one another; and, with obvious pleasurable excitement in repetition he knocks them down, thus externalizing the trauma of his own falls. Later the blocks may serve as the building stones for a miniature world in which an ever increasing number of bodily, mental and social experiences are externalized and dramatized. This manifestation we may call microcosmic play.

We can term macrocosmic that form of play in which the child moves as in a kind of trance among life-sized objects, pretending that they are whatever background he needs for his imagination. Thus he manifests his need for omnipotence in a material which all too often is rudely claimed by adults, because it has other, “grown-up” purposes.

These are a few of the more basic types of play which the child offers to us for comparison—each with its special kind of infantile fascination—developing one after the other as he grows and then shifting more or less freely from one to the other at certain stages.

Following an exceptional sequence of disappointments and frustrations, a girl of eight, K, a patient of Dr. Florence Clothier of Boston, made a veritable fortress of herself. Stubborn, stiff, uncommunicative, she would occasionally open all the orifices of her body, and annoy her environment by spitting, wetting, soiling, and passing flatus. One received the impression that these symptoms were not only animistic acts by which she eliminated hated intruders (her stepmother and her stepbrother) but also “shooting” with all available ammunition. While polymorphous in their zonal expression, these acts were clearly dominated by a combination of the eliminative and intrusive impulses. As the main object of the destructive part of this impulse, one could recognize the stepmother’s body, in which the child suspected that more rival stepbrothers were growing. Naturally, this wild little girl was at the same time most anxious to find for herself a good mother’s body in which to hide, to cry, and to sleep. Someone had told her that her own mother had died while giving birth to her; and one can imagine what conflicts arose when she first met the psychiatrist and saw that this potentially new and better mother was actually pregnant.

These biographic data are enough to explain the play which I am going to describe. Nevertheless, there is nothing essentially atypical in this play. This girl’s constitution and experience simply made dominant the problem of intrusion which every child faces at least in one period of his life, namely, in the phallic period.

The phallic phase, last of the ambivalent stages, leads the child into a maze of “claustrum” fantasies, in which some children—for a longer or shorter time—get hopelessly lost.10 They want to touch, enter and know the secrets of all interiors but are frightened of dark rooms and dreams of jails and tombs. As they flee the claustrum they would like to hide in mother’s arms; fleeing their own disturbing impulses toward the mother’s body they escape into willful acts of displaced violence, only to be restricted and “jailed” again. The mother’s body, into which the baby wanted to retreat in order to find food, rest, sleep, and protection from the dangerous world, becomes in the phallic phase the dangerous world, the very object and symbol of aggressive conquest. Further obstructing this conquest are the father’s rights (because of his strength) and the younger siblings’ rights (because of their weakness); and thus the mother, a heaven and hell at the same time, becomes the center of a hopeless rivalry. Whether to go forward or backward, to be hero or baby—that is the question. It is in this phase that the boy, knowing there is no way back, sets his face towards the future (where all those ideals are waiting for him, which we symbolize by superhuman mother figures); while to the girl, her own body’s claustrum offers a vague promise and new dangers.

In his play, the boy at this stage prefers games of war and crime, and expresses most emphatically the intrusive mode; the girl, by contrast, in caring for dolls, in building a small house with a toy baby or a toy animal in it or in other protective configurations expresses the procreative-protective tendency which will remain the point of reference for whatever course she may take in her future.

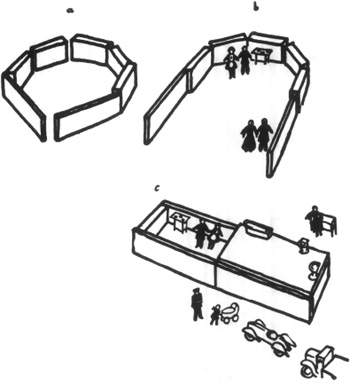

Dr. Clothier’s patient, in her play during a period of transition from eliminative-intrusive to female tendencies, showed many distorted manifestations of these problems:

In cutting her own hair and eyelashes, and threatening to cut her eyes and teeth, she approximated a return into the autocosmic sphere of play.

Microcosmic: (1) Dramatic: Five dolls, named after father, stepmother, stepbrother, sister and herself are approached from behind by a snake who eats everybody except herself and her pet animal.

(2) Pictorial: Drawings with long rows of houses which are being approached, entered, and left by a stealing cat: The house more and more assumed the appearance of the human body, with the two sides of the walk leading to it representing the legs between which the door was entered by the cat. The girl noticed this resemblance herself and made the giggling remark, “Do you think that a house can stand on the walk?”

Macrocosmic: (1) For several days she built “houses.” The entrance had two round portal forms represented by a dish on each side. The patient began going in and out of the house on all fours, always entering the house backwards. When inside, she picked up one of the dishes and pretended to drink from it; then she curled up in a fetal position. Crawling backwards over and over again, she said to the psychiatrist, “You watch and tell me so I won’t hit the back of the house.” The psychiatrist told her when to stop, but each time she gave a vicious lunge backwards, breaking through the wall.

(2) Where her macrocosmic play expanded beyond the sphere of toys, i.e., became naughty, she climbed on tables, desks and shelves, invaded drawers, and tore papers. Often only bursting in and out of the room was an act big enough to express her intrusive rage.

(3) At a decisive point in her treatment, the girl was especially fascinated by a rubber syringe with which she squirted water everywhere. “Now I’m a wild Indian, so look out!” On a certain day, during a period of a general change in attitude, the girl squirted on the floor a big circle with one line representing a radius  ; then she angrily made a puddle out of her design. The next day she repeated the same configuration, but added a small circle in the center of the big one:

; then she angrily made a puddle out of her design. The next day she repeated the same configuration, but added a small circle in the center of the big one:  On the third day, she again drew a larger circle and, without the connecting radius, a smaller circle in the center, saying, “This is a baby circle.”

On the third day, she again drew a larger circle and, without the connecting radius, a smaller circle in the center, saying, “This is a baby circle.”  This time she did not destroy the figure, but said giggling, “There are no cats here” (to enter the circle and steal the baby). The change of configurations in this play from phallic (syringe) to female-protective is obvious. Moreover the little girl created a symbol and in doing so seemed to have a moment of clarity and pacification.

This time she did not destroy the figure, but said giggling, “There are no cats here” (to enter the circle and steal the baby). The change of configurations in this play from phallic (syringe) to female-protective is obvious. Moreover the little girl created a symbol and in doing so seemed to have a moment of clarity and pacification.

(4) Around the same time she dictated the following story to a teacher. She said she had heard it somewhere. We add it as an association which in a narrative and quite humorous form seemed to express symbolically an acceptance of the difference between boys and girls:

The Pumpkin and the Cat: The farmer put the pumpkin in the barn, and the cat came, and the cat said to the pumpkin, “Do you want to stay here? Let’s go away.” And the pumpkin rolled and tumbled, and the cat walked and walked, until it began to rain. The cat lifted up his wet paw. A woodcutter came by. The pumpkin said, “Mister, will you please cut my top off, and scrape all the seeds out, so the cat can come in?” The woodcutter cut off the top of the pumpkin and scraped all the seeds out.

They went on tumbling and rolling until morning. They started off again, tumbling and rolling. Then pretty soon it was night. And it began to rain harder, and the cat lifted up his wet paw, and the pumpkin said, “You’d better get inside.” “Yes, but we haven’t got any two windows and a nose and a mouth.” The pumpkin said, “You get out and I’ll go to the carpenter.” He went to the carpenter and said, “Mr. Carpenter, will you please cut two windows and a nose and mouth?”

The cat came in the pumpkin and the pumpkin and the cat laughed. Then they rolled and tumbled, until they came to a little house. They heard a boy whistling and then a girl came out of the house and said, “What do you wish you had most for Halloween?” The boy said: “I wish I had a nice round pumpkin,” and the girl said, “I wish I had a nice little black cat.”

Up rolled the pumpkin to the little boy, and the girl said, “Look what the fairy brought us, and I think it’s a cat inside!”

And off jumped the cover, and out jumped the little black cat, and right into the little girl’s arms.

And they lighted the pumpkin, and put it on the table, and put the kitty next to it, until the mother came home.

B. ZONES, IMPULSES, MODES

It is not only in pathological cases that children’s acts impress us as being unexpected and apparently incoherent. The observer of any child’s life feels at moments that an essential factor is eluding him, as the loon in the lake eludes the hunter by sudden turns under the surface. Whether the child is playful, naughty or compulsive; whether his acts involve bodily functions or toys, person or abstracts, only analytic comparison reveals that what so suddenly appears in one category is essentially related to that which disappeared in another. Sometimes it is the mere replacement in time which makes the analyst become aware of the inner connection of two acts; sometimes it is a quality of an emotion or a tendency of a drive common to both. Often, however, (and this is especially true for the period of pregenitality on which we focus our attention here) the only observational link between two acts is what we wish to describe as the organmode.11

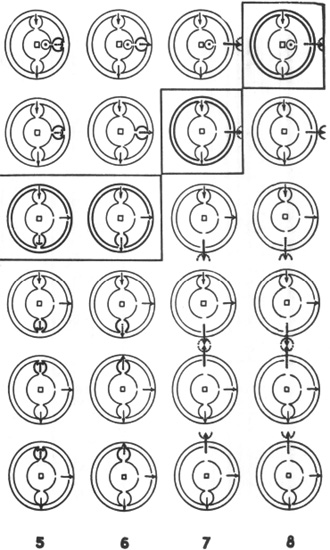

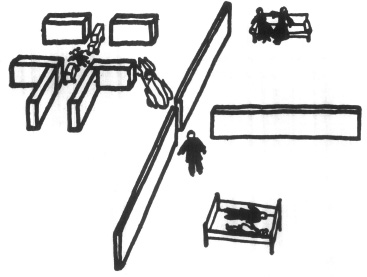

To clear the way for more systematic observations of the interrelationship between the intrabodily and extrabodily aspects of pre-genitality, it seems best to reduce the displaced impulses to the simplest spatial terms, i.e., to signs which represent the dynamic principle of the body apertures in which the impulses are first centered. I propose that we accept the sign  as representing the incorporation of an object by means of sucking.

as representing the incorporation of an object by means of sucking.  may represent the incorporation by means of biting;

may represent the incorporation by means of biting;  the retaining of or closing up against an object;

the retaining of or closing up against an object;  expelling and

expelling and  intruding.

intruding.

The organ-modes, then, are common spatial modalities peculiar to the appearance of pregenital impulses throughout their range of manifestation; whether gratification is experienced in the elimination of waste product by a body aperture, by the spilling of a bottle’s content, by throwing objects out of a window, or pushing a person out of one’s physical sphere, we recognize the mode of elimination as the common descriptive characterization of all these acts, and conclude that we are confronted with interchangeable manifestations of what was originally the impulse of elimination.

Surveying the field of these manifestations, one finds that what Freud has described as pregenitality is the development through a succession of narcissistic organ cathexes of impulses which represent all the possible relationships of a body and an object. Pregenitality not only teaches all the patterns of emotional relationship but also offers all the spatial modalities of experience. Led by pregenital impulses (or confused by them as the case may be) children experiment more or less playfully in space with all the possible relationships of one object to another one and of the body as a whole to space.

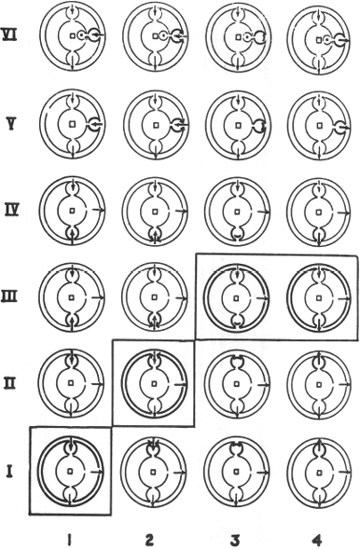

For didactic purposes, I have arranged the modes in a chart of pregenitality which (in formulation without words) indicates the network of original interrelationships of zones and impulses. This chart has been helpful in observation and teaching when used as a shortcut, leading to but by no means avoiding the knowledge of the other components of pregenitality.

Nobody who works in the field of human behavior can be unaware of the dangers of or blind to the necessity for such tentative systematization.

The chart is composed of single diagrams which represent the human organism in the successive stages of emphasis on certain erotogenic zones in pregenitality. I 1, for example, like all the other diagrams, consists of three concentric circles which represent three primitive aspects of the life of any organism: a the inner surface, b the outer surface, and c the sphere of outward behavior. The bodily impulses are represented in the diagram where certain organs connect the outer world with the inner surface of the body, respectively, 1 the oral-facial, 2 anal-urethral, and 3 genitalurethral zones.12

In each diagram one impulse is represented as being dominant by means of a heavier line; in I 1 it is the first (“sucking”) mode in the oral system. Thus we indicate that we are concerned with that stage of development in which the libido is concentrated mainly in the oral system and serves normally to develop this impulse. Also the circle which represents the surface of the body is more heavily outlined, as is true for all corresponding circles in the diagrams which lie on the diagonal. This indicates that the principle of receptive incorporation legitimately dominates the whole “surface of the body” during the first oral stage. Skin and senses are ready to “drink in” all kinds of perceptual sensations as brought to them by the environment and to enjoy libidinally all kinds of touching, stroking, rocking sensations if they are only kept below the threshold at which motor response would be provoked. The heavy outlining of the outer circle indicates that at this stage social behavior also expresses expectant readiness to receive, as is obvious in the rhythm of waiting, crying, drinking, sleeping. Reactions to stimuli which require more than the holding on with mouth and hands to what has been offered by the environment remain diffuse and uncoordinated. All of this—degree of coordination, muscle and sense development, libido distribution and spontaneous behavior—will have to be represented in a final formulation of the first bodily manifestation of our impulse.

In II 2, the dominating impulse is  The biting system (gums, jaws, neck, etc.) is in the possession of a relatively high amount of libido and of muscle energy which, at the same time, is manifest throughout the spheres of perception and action; the eyes learn to focus, the ears to locate, the hands to reach out, and the arms to hold. The coordination of the system necessary for reaching out to an object and the “plucking” of it for oral incorporation is established. Simultaneously, a change in the concept of the outer world probably occurs. This is represented by the dotted arrow, which indicates that the incoming object is conceived of in a somewhat different way from formerly. The object of libidinal interest and of psychobiological training is now the food. Later it will be feces and then the genitals. Presumably each is first conceived of by the infant as belonging inherently to his own body and subject to his own will, during the first stages of the development of each zone (I 1, III 3, 4, V 6). It is only through a sum of psycho-biological and cultural experiences that the child learns that these objects belong to the environment—an expulsion from the paradise of omnipotence which takes place in the transition from the first (I, III, V) to the second (II, IV, VI) part of each stage. If we say psychobiological and cultural influences, we mean for orality that the changing conditions of the gums and the irresistible biting impulse, no less than the changing character of the food and of its delivery, participate in this expulsion into a world where “in the sweat of thy face thou shalt eat bread till thou return under the ground.”

The biting system (gums, jaws, neck, etc.) is in the possession of a relatively high amount of libido and of muscle energy which, at the same time, is manifest throughout the spheres of perception and action; the eyes learn to focus, the ears to locate, the hands to reach out, and the arms to hold. The coordination of the system necessary for reaching out to an object and the “plucking” of it for oral incorporation is established. Simultaneously, a change in the concept of the outer world probably occurs. This is represented by the dotted arrow, which indicates that the incoming object is conceived of in a somewhat different way from formerly. The object of libidinal interest and of psychobiological training is now the food. Later it will be feces and then the genitals. Presumably each is first conceived of by the infant as belonging inherently to his own body and subject to his own will, during the first stages of the development of each zone (I 1, III 3, 4, V 6). It is only through a sum of psycho-biological and cultural experiences that the child learns that these objects belong to the environment—an expulsion from the paradise of omnipotence which takes place in the transition from the first (I, III, V) to the second (II, IV, VI) part of each stage. If we say psychobiological and cultural influences, we mean for orality that the changing conditions of the gums and the irresistible biting impulse, no less than the changing character of the food and of its delivery, participate in this expulsion into a world where “in the sweat of thy face thou shalt eat bread till thou return under the ground.”

It is to be regretted that for the sake of orderly procedure we have to begin with the lower left corner of our chart which justly should be kept as vague as our knowledge of these stages of development is dark. But a principle of description to be used throughout the chart may be explained here: The normal succession of stages is represented in the diagrams on the diagonal. It is in these stages that impulse and zone find the full training of their function within the framework of growth and maturation. A deviation from the normal diagonal development can be horizontal, i.e., progressing to the impulse of the next stage before the whole organism has integrated the first stage; or, it can be vertical i.e., insisting on the impulse of the first stage when the organism as a whole would be ready for the training and integration of the dynamic principle of the next stage. Thus, a differentiation of zones and impulses is introduced which gives our chart its two dimensions: in the horizontal we have different impulses connected with one and the same zone; in the vertical we see one and the same impulse connected with different zones.

The stages, as well as their functional characteristics, are, of course, overlapping. The libido, during and after the stages of concentration shown in 11, and II 2, becomes concentrated in the excretory system, can be pleasurably gratified by the retention and expulsion of the (now more solid) feces, while, or perhaps just because, the general impulses dominating the rapidly developing sensory and muscular behavior are retaining and expelling. Unlike the previous stages, when incorporation at any cost seemed the rule of behavior, now strong, sometimes “unreasonable,” discrimination takes place: sensations are in rapid succession accepted, rejected; objects are clung to stubbornly or thrown away violently; or persons are obstinately demanded or pushed away angrily—tendencies which under the influence of educational factors easily develop into temporary or lasting extremes of self-insistent behavior, maintaining a narcissistic paradise of self-assertive discriminations. The sad truth to be learned in the anal stage and added to the experience of oral phase (which was: “You shall not find pleasure in incorporation except under certain conditions”) is: “In your body, your self, your mind, your room, you shall find pleasure in retaining or expelling only under certain conditions.”

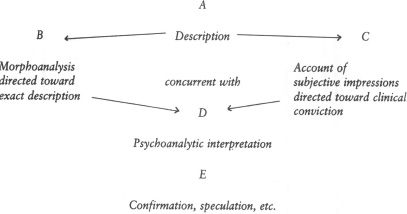

Thus, the diagonal of the chart indicates and draws up for formulation some normal stages of development, in which certain zones are normally libidinized, certain impulses normally generalized. Where the outer circles are not heavily outlined (in the non-diagonal remainder of the chart) those configurations of impulses can be found which at the particular stage become dominant and generalized only when an abnormal situation arises; though as integrated part tendencies all the impulses are essential for all the zones of a living organism at all times. Wherever a specific case suggests it, the chart might be used to illustrate abnormal correlations by interchanging impulses and by outlining more heavily any untimely generalization of an impulse.