A discernible relationship between the dreamer’s acute life problem and the problems left over from corresponding infantile phases has been indicated in Section VI. Here I shall select two further items as topics for a final brief discussion: psychosexual fixation and arrest; collective identity and ego identity.

In our general clinical usage we employ the term fixation alternately for that infantile stage in which an individual received the relatively greatest amount of gratification and to which, therefore, his secret wishes persistently return and for that infantile stage of development beyond which he is unable to proceed because it marked an end or determined slow-up of his psychosexual maturation. I would prefer to call the latter the point of arrest, for it seems to me that an individual’s psychosexual character and proneness for disturbances depends not so much on the point of fixation as on the range between the point of fixation and the point of arrest, and on the quality of their interplay. It stands to reason that a fixation on the oral stage, for example, endangers an individual most if he is also arrested close to this stage, while a relative oral fixation can become an asset if the individual advances a considerable length along the path of psychosexual maturation, making the most of each step and cultivating (on the very basis of a favorable balance of basic trust over basic mistrust as derived from an intensive oral stage) a certain capacity to experience and to exploit subsequent crises to the full. Another individual with a similar range but a different quality of progression may, for the longest time, show no specific fixation on orality; he may indicate a reasonable balance of a moderate amount of all the varieties of psychosexual energy—and yet, the quality of the whole ensemble may be so brittle that a major shock can make it tumble to the ground whereupon an “oral” fixation may be blamed for it. Thus, one could review our nosology from the point of view of the particular field circumscribed by the points of fixation and arrest and of the properties of that field. At any rate, in a dream, and especially in a series of dreams, the patient’s “going back and forth” between the two points can be determined rather clearly. Our outline, therefore, differentiates between a point of psychosexual fixation and one of psychosexual arrest.

The Irma Dream demonstrates a great range and power of pre-genital themes. From an initial position of phallic-urethral and voyeuristic hybris, the dreamer regresses to an oral-tactual position (Irma’s exposed mouth and the kinesthetic sensation of suffering through her) and to an anal-sadistic one (the elimination of the poison from the body, the repudiation of Dr. Otto). As for the dreamer of the Irma Dream (or any individual not clearly circumscribed by neurotic stereotypy), we should probably postpone any over-all classification until we have thought through the suggestions contained in Freud’s first formulation of “libidinal types.” In postulating that the ideal type of man is, each in fair measure, narcissistic and compulsive and erotic, he opened the way to a new consideration of normality, and thus of abnormality. His formulation does not (as some of our day do) focus on single fixations which may upset a unilinear psychosexual progression of a low over-all tonus, but allows for strong conflicts on each level, solved by the maturing ego adequate to each stage, and finally integrated in a vigorous kind of equilibrium.

I shall conclude with the discussion of ego identity (2,3,5). This discussion must, again, be restricted to the Irma Dream and to the typical problems which it may illustrate. The concept of identity refers to an over-all attitude (a Grundhaltung) which the young person at the end of adolescence must derive from his ego’s successful synthesis of postadolescent drive organization and social realities. A sense of identity implies that one experiences an over-all sameness and continuity extending from the personal past (now internalized in introjects and identifications) into a tangible future; and from the community’s past (now existing in traditions and institutions sustaining a communal sense of identity) into foreseeably or imaginable realities of work accomplishment and role satisfaction. I had started to use the terms ego identity and group identity for this vital aspect of personality development before I (as far as I know) became aware of Freud’s having used the term innere Identität in a peripheral pronouncement and yet in regard to a central matter in his life.

In 1926, Freud sent to the members of a Jewish lodge a speech (8) in which he discussed his relationship to Jewry and discarded religious faith and national pride as “the prime bonds.” He then pointed, in poetic rather than scientific terms, to an unconscious as well as a conscious attraction in Jewry: powerful, unverbalized emotions (viele dunkle Gefühlsmächte), and the clear consciousness of an inner identity (die klare Bewusstheit der inneren Identität). Finally, he mentioned two traits which he felt he owed his Jewish ancestry: freedom from prejudices which narrow the use of the intellect, and the readiness to live in opposition. This formulation sheds an interesting light on the fact that in the Irma Dream the dreamer can be shown both to belittle and yet also temporarily to adopt membership in the “compact” majority of his dream population. Freud’s remarks also give added background to what we recognized as the dreamer’s vigorous and anxious preoccupation, namely, the use of incisive intelligence in courageous isolation, the strong urge to investigate, to unveil, and to recognize: the Irma Dream strongly represents this ego-syntonic part of what I would consider a cornerstone of the dreamer’s identity, even as it defends the dreamer against the infantile guilt associated with such ambition.

The dream and its associations also point to at least one “evil prototype”—the prototype of all that which must be excluded from one’s identity: here it is, in the words of its American counterpart, the “dirty little squirt,” or, more severely, the “unclean one” who has forfeited his claim to “promising” intelligence.

Much has been said about Freud’s ambitiousness; friends have been astonished and adversaries amused to find that he disavowed it. To be the primus, the best student of his class through his school years, seemed as natural to him (“the first-born son of a young mother”) as to write the Gesammelten Schriften. The explanation is, of course, that he was not “ambitious” in the sense of ehrgeizig: he did not hunger for medals and titles for their own sakes. The ambition of uniqueness in intellectual accomplishment, on the other hand, was not only ego-syntonic but was ethno-syntonic, almost an obligation to his people. The tradition of his people, then, and a firm inner identity provided the continuity which helped Freud to overcome the neurotic dangers to his accomplishment which are suggested in the Irma Dream, namely, the guilt over the wish to be the one-and-only who would overcome the derisive fathers and unveil the mystery. It helped him in the necessity to abandon well-established methods of sober investigation (invented to find out a few things exactly and safely to overlook the rest) for a method of self-revelation apt to open the floodgates of the unconscious. If we seem to recognize in this dream something of a puberty rite, we probably touch on a matter mentioned more than once in Freud’s letters, namely, the “repeated adolescence” of creative minds, which he ascribed to himself as well as to Fliess.

In our terms, the creative mind seems to face repeatedly what most men, once and for all, settle in late adolescence. The “norma” individual combines the various prohibitions and challenges of the ego ideal in a sober, modest, and workable unit, well anchored in a set of techniques and in the roles which go with them. The restless individual must, for better or for worse, alleviate a persistently revived infantile superego pressure by the reassertion of his ego identity. At the time of the Irma Dream, Freud was acutely aware that his restless search and his superior equipment were to expose him to the hybris which few men must face, namely, the entry into the unknown where it meant the liberation of revolutionary forces and the necessity of new laws of conduct. Like Moses, Freud despaired of the task, and by sending some of the first discoveries of his inner search to Fliess with a request to destroy them (to “eliminate the poison”), he came close to smashing his tablets. The letters reflect his ambivalent dismay. In the Irma Dream, we see him struggle between a surrender to the traditional authority of Dr. M. (superego), a projection of his own self-esteem on his imaginative and far-away friend, Fliess (ego ideal), and the recognition that he himself must be the lone (self-) investigator (ego identity). In life he was about to commit himself to his “inner tyrant,” psychology, and with it, to a new principle of human integrity.

The Irma Dream documents a crisis, during which a medical investigator’s identity loses and regains its “conflict-free status” (10, 13) . It illustrates how the latent infantile wish that provides the energy for the renewed conflict, and thus for the dream, is imbedded in a manifest dream structure which on every level reflects significant trends of the dreamer’s total situation. Dreams, then, not only fulfill naked wishes of sexual license, of unlimited dominance and of unrestricted destructiveness; where they work, they also lift the dreamer’s isolation, appease his conscience, and preserve his identity, each in specific and instructive ways.

Bibliography

1. E. H. Erikson, “Studies in the Interpretation of Play,” Genetic Psychology Monograph, 22 (1940), 557–671.

2. ——, Childhood and Society (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1950).

3. ——, “Growth and Crises of the ‘Healthy Personality.’ ” For Fact-Finding Committee, Midcentury White House Conference (New York: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, 1950). Somewhat revised in Personality in Nature, Culture and Society, eds. C. Kluckhohn and H. R. Murray (New York: Knopf, 1953).

4. ——, “Sex Differences in the Play Constructions of Pre-Adolescents.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 21 (1951), 667–92.

5. ——, “Identity and Young Adulthood.” Presented at the Thirty-fifth Anniversary of the Institute of the Judge Baker Guidance Center in Boston, May 1953 (to be published).

6. S. Freud, “The Interpretation of Dreams,” In The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud (New York: Modern Library, 1938).

7. ——, “The History of the Psychoanalytic Movement.” In The Basic Writings of Sigmund Freud (New York: Modern Library, 1938).

8. ——, “Ansprache an die Mitgleider des Vereins B’Nai B’rith” (1926). In Gesammelte Werke, vol. 16 (London, Imago Publishing Co., 1941).

9. ——, Aus den Anfängen der Psychoanalyse (London: Imago Publishing Co., 1950).

10. H. Hartmann, “Ichpsychologie und Anpassungsproblem.” Internationale Zeitschrift für. Psychoanalyse und Imago, 24 (1939), 62–135. Translated in part in Rapaport (13).

11. E. Kris, “On Preconscious Mental Processes.” Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 19 (1950), 540–60. Also in Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art (New York: International Universities Press, 1951).

12. ——, “On Inspiration.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 20 (1939), 377–89. Also in Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art (New York: International Universities Press, 1952).

13. D. Rapaport, Organization and Pathology of Thought (New York: Columbia University Press, 1951).

Notes

1 German words in brackets indicate that the writer will question and discuss A. A. Brill’s translation of these words.

2 “Formerly I found it extraordinarily difficult to accustom my readers to the distinction between the manifest dream-content and the latent dream-thoughts. Over and over again arguments and objections were adduced from the uninterpreted dream as it was retained in the memory, and the necessity of interpreting the dream was ignored. But now, when the analysts have at least become reconciled to substituting for the manifest dream its meaning as found by interpretation, many of them are guilty of another mistake, to which they adhere just as stubbornly. They look for the essence of the dream in this latent content, and thereby overlook the distinction between latent dream-thoughts and the dream-work. The dream is fundamentally nothing more that a special form of our thinking, which is made possible by the conditions of the sleeping state. It is the dream-work which produces this form, and it alone is the essence of dreaming—the only explanation of its singularity” (6, pp. 466–467).

3 See the chapter “Zones, Modes, and Modalities” in (2).

4 According to a report presented to the Seminar on Dream Interpretation in the San Francisco Psychoanalytic Institute.

5 In another dream mentioned in The Interpretation of Dreams (6), Freud accuses himself of such hypocrisy, when in a dream he treats with great affection another doctor whose face (“beardless” in actuality) he also alters, this time by making it seem elongated and by adding a yellow beard. Freud thinks that he is really trying to make the doctor out to be a seducer of women patients and a “simpleton.” The German Schwachkopf and Schlemihl, must be considered the evil prototype which serves as a counterpart to the ideal prototype, to be further elucidated here, the smart young Jew who “promises much,” as a professional man.

6 See Ernst Kris’ concept of a “regression in the service of the ego” (11).

7 As pointed out elsewhere (2), Hitler, also the son of an old father and a young mother, in a corresponding marginal area, shrewdly exploited such infantile humiliation: he pointed the way to the defiant destruction of all paternal images. Freud, the Jew, chose the way of scholarly persistence until the very relationship to the father (the oedipus complex) itself became a matter of universal enlightenment.

Sex Differences in the Play Configurations of American Preadolescents (1955)

In previous publications,1 the writer has illustrated the clinical impression that a playing child’s behavior in space (i.e., his movements in a given playroom, his handling of toys, or his arrangement of play objects on floor or table) adds a significant dimension to the observation of play. And, indeed, three-dimensional arrangement in actual space is the variable distinguishing a play phenomenon from other “projective” media, which utilize space either in two-dimensional projection or through the purely verbal communication of spatial images. In an exploratory way it was also suggested that such clinical hints could be applied to the observation of older children and even of adults; play constructions of college students of both sexes2 and of mental patients were described and first impressions formulated.3 In all this work a suggestive difference was observed in the way in which the two sexes utilized a given play space to dramatize rather divergent themes; thus male college students occupied themselves to a significant degree with the representation (or avoidance) of an imagined danger to females emanating from careless drivers in street traffic, while female college students seemed preoccupied with dangers, threatening things and people in the interior of houses, and thus from intrusive males. The question arose whether or not such sex differences could be formulated so as to be useful to observers in a nonclinical situation and on a more significant scale; and whether these differences would then appear to be determined by biological facts, such as difference in sex or maturational stage, or by differences in cultural conditioning. In 1940 the opportunity offered itself to secure play constructions from about 150 California children (about 75 boys and 75 girls), all of the same ages.4 The procedure to be described here is an exploratory extension of “clinical” observation to a “normal” sample.5 The number of children examined were, at age eleven, 79 boys and 78 girls, at age twelve, 80 boys and 81 girls, at age thirteen, 77 boys and 73 girls. Thus the majority of children contributed three constructions to the total number of 468 (236 play constructions of boys and 232 constructions of girls), which will be examined here.

On each occasion the child was individually called into a room where he found a selection of toys such as was then available in department stores (122 blocks, 38 pieces of toy furniture, 14 small dolls, 9 toy cars, 11 toy animals) laid out on two shelves. There was no attempt to make a careful selection of toys on the basis of size, color, material, etc. A study aspiring to such standards naturally would have to use dolls all made of the same materials and each accompanied by the same number of objects fitting in function and size, and themselves identical in material, color, weight, and so on. While it was not our intention to be methodologically consistent in this respect, the degree of inconsistency in the materials used may at least be indicated. Our family dolls were of rubber, which permitted their being bent into almost any shape; they were neatly dressed with all the loving care which German craftsmen lavish on playthings. A policeman and an aviator, however, were of unbending metal and were somewhat smaller than the doll family. There were toy cars, some of them smaller than the policeman, some bigger; but there were no airplanes to go with the aviator.

The toys were laid out in an ordered series of open cardboard boxes, each containing a class of toys, such as people, animals, and cars. These boxes were presented on a shelf. The blocks were on a second shelf in two piles, one containing a set of large blocks, one a set of small ones. Next to the shelves the stage for the actual construction was set: a square table with a square background of the same size.

The following instructions were given:

I am interested in moving pictures. I would like to know what kind of moving pictures children would make if they had a chance to make pictures. Of course, I could not provide you with a real studio and real actors and actresses; you will have to use these toys instead. Choose any of the things you see here and construct on this table an exciting scene out of an imaginary moving picture. Take as much time as you want, and tell me afterward what the scene is about.

While the child worked on his scene, the observer sat at his desk, presumably busy with some writing. From there he observed the child’s attack on the problem and sketched transitory stages of his play construction. When the subject indicated that the scene was completed, the observer said, “Tell me what it is all about,” and took dictation on what the child said. If no exciting content was immediately apparent, the observer further asked, “What is the most exciting thing about this scene?” He then mildly complimented the child on his construction.6

The reference to moving pictures was intended to reconcile these preadolescents to the suggested use of toys, which seemed appropriate only for a much younger age. And, indeed, only two children refused the task, and only one of these complained afterward about the “childishness” of the procedure: she was the smallest of all the children examined. The majority constructed scenes willingly, although their enthusiasm for the task and their ability to concentrate on it, their skill in handling the toys, and their originality in arranging them varied widely. Yet the children of this study produced scenes with a striking lack of similarity to movie clichés. In nearly five hundred constructions, not more than three were compared with actual moving pictures. In no case was a particular doll referred to as representing a particular actor or actress. Lack of movie experience can hardly be blamed for this; the majority of these children attended movies regularly and had their favorite actors and types of pictures. Neither was the influence of any of the radio programs or comic pictures noticeable except in so far as they themselves elaborated upon clichés of western lore; there were no specific references to “Superman” and only a few to “Red Ryder.” Similarly, contemporary events of local or world significance scarcely appeared. The play procedure was first employed shortly before the San Francisco World’s Fair opened its gates—an event which dominated the Far West and especially the San Francisco Bay region for months. This sparkling fair, located in the middle of the bay and offering an untold variety of spectacles, was mentioned in not more than five cases. Again, the approach and outbreak of the war did not increase the occurrence of the aviator in the play scenes, in spite of the acute rise in general estimation of military aviation, especially in the aspirations of our boys and their older brothers. The aviator rated next to the monk in the frequency of casting.

It has been surmised that in both groups the toys suggested infantile play so strongly that other pretensions became impossible. Yet only one girl undressed a doll, as a younger girl would; she had recently been involved in a neighborhood sex-education crisis. And while little boys like to dramatize automobile accidents with the proper bumps and noises, in our constructions automobile accidents, as well as earthquakes and bombings, were not made to happen; rather, their final outcome was quietly arranged. At first glance, therefore, the play constructions cannot be considered to be motivated by a regression to infantile play in its overt manifestations.

In general, none of the simpler explanations of the motivations responsible for the play constructions presented could do away with the impression that a play act—like a dream—is a complicated dynamic product of “manifest” and “latent” themes, of past experience and present task, of the need to express something and the need to suppress something, of clear representation, symbolic indirection, and radical disguise.

It will be seen that girls, on the whole, tend to build quiet scenes of everyday life, preferably within a home or in school. The most frequent “exciting scene” built by girls is a quiet family constellation, in a house without walls, with the older girl playing the piano. Disturbances in the girls’ scenes are primarily caused by animals, usually cute puppies, or by mischievous children—always boys. More serious accidents occur too, but there are no murders, and there is little gun play. The boys produce more buildings and outdoor scenes, and especially scenes with wild animals, Indians, or automobile accidents; they prefer toys which move or represent motion. Peaceful scenes are predominantly traffic scenes under the guiding supervision of the policeman. In fact, the policeman is the “person” most often used by the boys, while the older girl is the one preferred by girls.7 Otherwise, it will be seen that the “family dolls” are used more by girls, as follows functionally from the fact that they produce more indoor scenes, while the policeman can apply his restraining influence to cars in traffic as well as to wild beasts and Indians.*

The general method of the study was clinical as well as statistical; i. e., each play construction was correlated with the constructions of all the children as well as with the other performances of the same child. Thus unique elements in the play construction were found to be related to unique elements in the life-history of the individual, while a number of common elements were correlated statistically to biographic elements shared by all the children.

In the following three examples, the interplay of manifest theme and play configuration and their relation to significant life-data will be illustrated.

Deborah,8 a well-mannered, intelligent, and healthy girl of eleven, calmly selects (by transferring them from shelves to table) all the furniture, the whole family, and the two little dogs, but leaves blocks, cars, uniformed dolls, and the other animals untouched. Her scene represents the interior of a house. Since she uses no blocks, there are no outer walls around the house or partitions within it. The house furniture is distributed over the whole width of the table but not without well-defined groups and configurations: there is a circular arrangement of living-room furniture in the right foreground, a bathroom arrangement along the back wall, and an angular bedroom arrangement in the left background. Thus the various parts of the house are divided in a reasonably functional way. In contrast, a piano in the left foreground and a table next to it (incidentally, the only red pieces of furniture used) do not seem to belong to any configuration. Taken together, they do not constitute a conventional room, although they do seem to belong together.

Turning to the cast, we note, within the circle of the living-room, a group consisting of a woman, a boy, a baby, and the two puppies. The woman has the baby in her arms; the boy plays with the two puppies. While this sociable group is as if held together by the circle, all the other people are occupied with themselves: clockwise, in the left foreground, the man at the piano, the girl at the desk, the other boy in the bed in the left background, and the second woman in the kitchen along the back wall.

Having arranged all this slowly and calmly, Deborah indicates with a smile that she is ready to tell her story, which is short enough: “This boy [in the background] is bad, and his mother sent him to bed.” She does not seem inclined to say anything about the others. The experimenter (who must now confess that, at the end of this scene, he permitted himself the clinical luxury of one nonstandardized question) asks, “Which one of these people would you like to be?” “The boy with the puppies,” she replies.

While her spontaneous story singled out the lonely boy in the farthest background, an elicited afterthought focuses, instead, on the second boy, who is part of the lively family circle in the foreground. In all their brevity, these two references point to a few interpersonal themes: punishments, closeness to the mother and separation from her, loneliness and playfulness, and an admitted preference for being a boy. Equally significant, of course, are the themes which are suggested but not verbalized.

The selective references to the boy in disgrace and to the happier boy in the foreground immediately point to the fact that in actual life Deborah has an older brother. (She has a baby brother, too, whose counterpart we may see in the baby in the arms of the mother.) We have ample reason to believe that she envies this boy because of his superior age, his sex, his sharp intellect, and his place close to the mother’s heart. Envy invites two intentions: to eliminate the competitor and to replace, to become him. Deborah’s play construction seems to accomplish this double purpose by splitting the brother in two: the competitor is banished to the lonely background; the boy in the foreground is what she would like to be.

We must ask here: Does Deborah have an inkling of such a “latent” meaning? We have no way of finding out. In this investigation, which is part of a long-range study, there is no place for embarrassing questions and interpretations. Therefore, if in this connection we speak of “latent” themes, “latent” cannot and does not mean “unconscious.” It merely means “not brought out in the child’s verbalization.” On the other hand, our interpretation is, as indicated, based on life-data and test material secured over more than a decade.

But where is Deborah? The little girl at the desk is the only girl in the scene and, incidentally, close to Deborah’s age. She was not mentioned in the story. She is, as pointed out, part of a configuration which does not fit as easily and functionally into a conventional house interior as do the other parts. The man at the piano, closest to the girl at the desk, has in common with her only that they share the two red pieces of furniture. Otherwise, they both face away from the family without facing toward each other; they are parallel to each other, with the girl a little behind the father.

In life, Deborah and her father are close to each other temperamentally. Marked introverts, they are both apt to shy away in a somewhat pained manner from the more vivacious members of the family, especially from the mother. Thus they have an important but negative trend in common. Just because of their more introvert natures, they are unable to express what unites them in any other way than by staying close to each other without saying much. This, we think, is represented spatially by a twosome in parallel isolation.

In adding this theme to the two verbalized themes (the isolated bad boy and the identification with the good boy in the playful circle), we surmise that the total scene well circumscribes the child’s main life-problem, namely, her isolated position between the parents, between the siblings, and (as yet) between the sexes. In a similar but never once identical manner, our clinical interpretation arrives at a theme representative of that life-task which (present or past) puts the greatest strain on the present psychological equilibrium. In this way, the play construction often is a significant help in the analysis of the life-history because it singles out one or a number of life-data as the subjectively most relevant ones and adds a significant key to the dynamic interpretation of the child’s personality development.

We may ask one further question: Is there any indication in the play constructions as to how deeply Deborah is disturbed or apt to become disturbed by the particular strain which she reveals? Here a clinical impression must suffice. Deborah uses the whole width of the table. She does not crowd her scene against the background or into one corner, as according to our observations, children with marked feelings of insecurity are apt to do; neither does she spread the furniture all over the table in an amorphous way, as we would expect a less mature child to do. Her groupings are meaningfully and pleasingly placed; so is her distribution of people. The one manifest incongruity in her groupings (father and daughter) proves to be latently significant; only here her scene suffers, as it were, a symptomatic lapse. Otherwise, while there is a simple honesty in her scene, there certainly is no great originality and no special sparkle in it. But here it is necessary to remember the surprising dearth of imagination in most constructions and the possibility that only specially inclined children may take to this medium with real verve.

In one configurational respect Deborah’s scene has much in common with those produced by most of the other girls. She places no walls around her house and no partitions inside. In anticipation of the statistical evaluation of this configurational item, we may state here an impression of essential femininity, which, together with the indications of relative inner balance, forms a welcome forecast of a personality potentially adequate to meet the stresses outlined.

In addition to the arrangement on the table and its relation to the verbalization, clinical criteria may be derived from the observation of a child’s general approach to the play situation. Deborah’s approach was calm, immediate, and consistent; her selection of toys was careful and apt. Other typical approaches are characterized by prolonged silence and sudden, determined action; by an enthusiasm which quickly runs its course; or by some immediate thoughtless remark such as, “I don’t know what to do.” The final stage of construction, in turn, can be characterized by frequent new beginnings; by a tendency to let things fall or drop; by evasional conversation; by the need to find room for all toys or to exclude certain types of them; by a perfectionist effort at being meticulous in detail; by an inability to wind up the task; by a sudden and unexplained loss of interest and ambition, etc. Such time curves must be integrated with the spatial analysis into a space-time continuum which reflects certain basic attributes of the subject’s way of organizing experience—in other words, the ways of his ego.

In the spatial analysis proper, we consider factors such as the following:

1. The subject’s approach, first, to the shelves and then to the table, and his way of connecting these two determinants of the play area.

2. The relationship of the play construction to the table surface, i.e., the area covered, and the location, distribution, and alignment of the main configurations with the table square.

3. The relationship of the whole of the construction to its parts and of the parts to one another.

Let us now compare the construction of calm and friendly Deborah with that of the girl most manifestly disturbed during the play procedure. This girl, whom we shall call Victoria, is also eleven years old; her intelligence is slightly lower than Deborah’s. She appears flushed and angry upon entering the room with her mother. A devout Catholic, Victoria had overheard somebody in the hall address this writer as “Doctor.” She had become acutely afraid that a man had replaced the Study’s woman doctor at this critical time of a girl’s development. This she had told her mother. The mother then questioned the writer; he reassured both ladies, whereupon Victoria, still with tears in her eyes but otherwise friendly, consented to construct a scene in her mother’s protective presence.

Victoria’s house form (she called it “a castle”) differs from Deborah’s construction in all respects. The floor plan of the building is constricted to a small area. There are high, thick walls and a blocked doorway; and there is neither furniture nor people. However, there seems to be an imaginary population of two: “The king,” says Victoria, letting her index finger slide along the edge of the foreground, “walks up and down in front of the castle. He waits for the queen, who is changing her dress in there” (pointing into the walled-off corner of the castle).

In this case the “traumatic” factor seems to lie, at least superficially, in the immediate past; for the thematic similarity between the child’s acute discomfort in the anticipation of having to undress before a man doctor and, in the play, the exclusion of His Majesty from Her Majesty’s boudoir seems immediately clear. High walls and closed gates, as well as the absence of people, all are rare among undisturbed girls; if present, they reflect either a general disturbance or temporary defensiveness.

One small configurational detail in this scene contradicts the general (thematic and configurational) emphasis on the protection of an undressed female from the view even of her husband. In spite of the fact that quite a number of square blocks were still available for a high and solid gate, Victoria selected the only rounded block for the front door. This arrangement, obviously, would permit the king to peek with ease if he were so inclined, and thus provides, for this construction, the usual (but always highly unique) discrepant detail which reveals the dynamic counterpart to the main manifest theme in the construction. Here the discrepant detail probably points to an underlying exhibitionism, which, in this preadolescent girl, may indeed have been the motivation for her somewhat hysterical defensiveness; for her years of experience with the Study had not given her any reason to expect embarrassing exposition or willful violation of her Catholic code. We note, however, that Victoria’s construction, overdefensive as it is in its constricted and high-walled configuration and theme, is placed in the center of the play table and does not, as we have learned to expect in the case of chronic anxiety, “cling” to the background; her upset, we conclude, may be acute and temporary.

Lisa, a third girl, has to deal with a lifelong and constant problem of anxiety: she was born with a congenital heart condition. This, however, had never been mentioned in her interviews with the workers of the Guidance Study. Her parents and her pediatrician, although in a constant state of preparedness for the possibility of a severe attack, did not wish the matter to be discussed with her and assumed that they had thus succeeded in keeping the child from feeling “different” from other children.

Lisa’s scene consists of a longish arrangement, quite uneven in height, of a number of blocks close to the back wall. On the highest block (according to the criteria to be presented later, a “tower”) stands the aviator, while below two women and two children are crowded into the small compartment of a front yard, apparently watching a procession of cars and animals. Lisa’s story follows. We see in it a metaphoric representation of a moment of heart weakness—an experience which she had never mentioned “in that many words.” The analogy between the play scene and its suggested meaning will be indicated by noting elements of a moment of heart failure in brackets following the corresponding play items.

“There is a quarrel between the mother and the nurse over money [anger]. This aviator stands high up on a tower [feeling of dangerous height]. He really is not an aviator, but he thinks he is [feeling of unreality]. First he feels as if his head was rotating, then that his whole body turns around and around [dizziness]. He sees these animals walking by which are not really there [seeing things move about in front of eyes]. Then this girl notices the dangerous situation of the aviator and calls an ambulance [awareness of attack and urge to call for help]. Just as the ambulance comes around a corner, the aviator falls down from the tower [feeling of sinking and falling]. The ambulance crew quickly unfolds a net; the aviator falls into it, but is bounced back up to the top of the tower [recovery]. He holds on to the edge of the tower and lies down [exhaustion].”

Having constructed this scene, the child smilingly left for her routine medical examination, where, for the first time, she mentioned to the Institute physician her frequent attacks of dizziness and indicated that at the time she was trying to overcome them by walking on irregular fences and precipitous places in order to get used to the dizziness. Her quite unique arrangement of blocks, then, seems to signify an uneven fencelike arrangement, at the highest point of which the moment of sinking weakness occurs. That the metaphoric expression of intimate experiences in free play “loosens” the communicability of these same experiences is, of course, the main rationale of play therapy.

These short summaries will illustrate the way in which configurations and themes may prove to be related to whatever item of the life-history, remote or recent, is at the moment most pressing in the child’s life. A major classification of areas of disturbance represented in our constructions suggests as relevant areas: (1) family constellations; (2) infantile traumata (for example, a twelve-year-old boy, who had lost his mother at five but had seemed quite oblivious to the event, in his construction revealed that he had been aware of a significant detail surrounding her death; this detail, in fact, had induced him secretly to blame his father for the loss); (3) physical affliction or hypochrondriac concern; (4) acute anxiety connected with the experiment; (5) psychosexual conflict. Naturally these themes interpenetrate.

We shall now turn to a strain which is by necessity shared by all preadolescents, namely, sexual maturation—a “natural” strain which, at the same time, has a most specific relation to the clearest differentiation in any mixed group, namely, difference in sex.

Building blocks provide a play medium most easily counted, measured, and characterized in regard to spatial arrangement. At the same time, they seem most impersonal and least compromised by cultural connotations and individual meanings. A block is almost nothing but a block. It seemed striking, then (unless one considered it a mere function of the difference in themes), that boys and girls differed in the number of blocks used as well as in the configurations constructed.

Boys use many more blocks, and use them in more varied ways, then girls do. The difference increases in the use of ornamental items, such as cylinders, triangles, cones, and knobs. More than three-quarters of the constructions in which knobs or cones occur are built by boys. This ratio increases with the simplest ornamental composition, namely, a cone on a cylinder; 86 per cent of the scenes in which this configuration occurs were built by boys. With a very few exceptions, only boys built constructions consisting only of blocks, while only girls, with no exception, arranged scenes consisting of furniture exclusively. In between these extremes the following classifications suggested themselves: towers and buildings, traffic lanes and intersections, simple inclosures, interiors without walls, outdoor scenes without use of blocks.*9

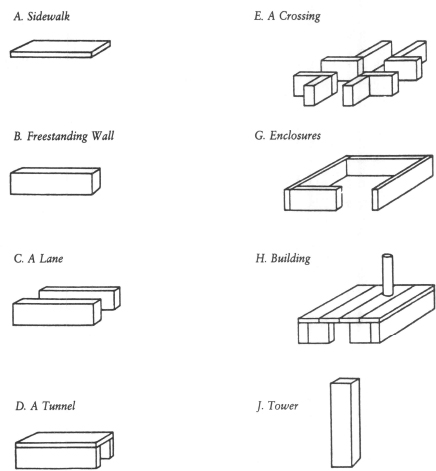

CONFIGURATIONAL ANALYSIS SCALE

I. Block configurations.

A. Sidewalk. One or more blocks lying flat, the length being at least one unit length long. (One unit length and one unit width are measured with the lengths and the widths of the large standard blocks.)

B. Freestanding wall. One or more blocks forming a wall. This wall is not a part of any configuration described in categories C to L, but is freestanding and at least one unit long. It may be straight or form an angle.

C. A lane. This configuration consists of two parallel A’s or B’s. The distance between the parallels should be smaller than their length.

D. A tunnel. A lane with a roof.

E. A crossing. Consists of lanes which cross one another.

F. Miscellaneous partitions. Walls dividing a given space without forming configurations A to E.

G. Inclosures. In general, while configurations A to F have more the character of dividing a space in such a way that objects are kept apart or channelized, the emphasis in G (and partially also in H and J) is on the enclosing of a given space on four sides. The background may form one of these sides.

H. Building. A house representation in which an interior is not only enclosed on four sides, but also covered with a roof which furthermore bears ornaments such as smokestacks or towerlike additions. In this category another basic general configurational trend is added to the previously mentioned tendencies toward dividing, channelizing, and enclosing, namely, the tendency toward elevating and elaborating, which in an increasing measure dominates categories H, J, and K.

J. Tower. At least twice as high as it is wide. At least half of its height transcends the rest of the construction.

K. Miscellaneous structures not included under A and J, such as façades, boats, trains, bridges, and so on.

L. Ruin. A pile of blocks arranged to indicate that it represents a destroyed structure.

II. Configurations of furniture without any use of blocks.

A. One room.

B. More than one room.

III. Configurations of animals without any use of blocks.

IV. Configurations of cars without any use of blocks.

The most significant sex differences concern the tendency among the boys to erect structures, buildings and towers, or to build streets; among the girls, to take the play table to be the interior of a house, with simple, little, or no use of blocks.

The configurational approach to the matter can be made more specific by showing the spatial function emphasized in the various ways of using (or not using) blocks. This method would combine all the constructions which share the function of channelizing traffic (such as lanes, tunnels, or crossings); all elaborate buildings and special structures (such as bridges, boats, etc.) which owe their character to the tendency of erecting and constructing; all simple walls, which merely inclose interiors; and all house interiors, which are without benefit of inclosing walls and are thus simply open interiors.

Block Configurations

In the case of inclosures, it was necessary to add other differentiations. To build a rectangular arrangement of simple walls is about the most common way of delineating any limited area and, therefore, is not likely to express any particular sex differences. But it was found that, in the case of many boys, simple inclosures in the form of front yards and back yards were only added to more elaborate buildings or that simple corrals or barnyards would appear in connection with outdoor scenes. In this category, therefore, only more detailed work showed that (1) significantly more boys than girls build inclosures only in conjunction with elaborate structures or traffic lanes; (2) significantly more girls than boys will be satisfied with the exclusive representation of a simple inclosure; (3) girls include a significantly greater number of (static) objects and people within their inclosures; (4) boys surround their inclosures with a significantly greater number of (moving) objects.

Height of structure, then, is prevalent in the configurations of the boys. The observation of the unique details which accompany constructions of extreme height suggests that the variable representing the opposite of elevation, i.e., downfall, is equally typical for boys. Fallen-down structures, namely, “ruins,” are exclusively found among boys,10 a fact which did not change in the days of the war when girls as well as boys must have been shocked by pictorial reports of destroyed homes. In connection with the very highest towers, something in the nature of a downward trend appears regularly, but in such a diverse form that only individual examples can illustrate what is meant: one boy, after much indecision, took his extraordinarily high tower down in order to build a final configuration of a simple and low character; another balanced his tower very precariously and pointed out that the immediate danger of collapse was in itself the exciting factor in his story, in fact, was his story. In two cases extremely high and well-built façades with towers were incongruously combined with low irregular inclosures. One boy who built an especially high tower put a prone boy doll at the foot of it and explained that this boy had fallen down from its height; another boy left the boy doll sitting high on one of several elaborate towers but said that the boy had had a mental breakdown and that the tower was an insane asylum. The very highest tower was built by the very smallest boy; and, to climax lowness, a colored boy built his structure under the table. In these and similar ways, variations of a theme make it apparent that the variable high-low is a masculine variable. To this generality, we would add the clinical judgment that, in preadolescent boys, extreme height (in its regular combination with an element of breakdown or fall) reflects a trend toward the emotional overcompensation of a doubt in, or a fear for, one’s masculinity, while varieties of “lowness” express passivity and depression.

Girls rarely build towers. When they do, they seem unable to make them stand freely in space. Their towers lean against, or stay close to the background. The highest tower built by any girl was not on the table at all but on a shelf in a niche in the wall beside and behind the table. The clinical impression is that, in girls of this age, the presence of a tower connotes the masculine overcompensation of an ambivalent dependency on the mother, which is indicated in the closeness of the structure to the background. There are strong clinical indications that a scene’s “clinging” to the background connotes “mother fixation,” while the extreme foreground serves to express counterphobic overcompensation.

In addition to the dimensions “high” and “low” and “forward” and “backward,” “open” and “closed” suggest themselves as significant. Open interiors of houses are built by a majority of girls. In many cases this interior is expressly peaceful. Where it is a home rather than a school, somebody, usually a little girl, plays the piano: a remarkably tame “exciting movie scene” for representative preadolescent girls. In a number of cases, however, a disturbance occurs. An intruding pig throws the family in an uproar and forces the girl to hide behind the piano; the father may, to the family’s astonishment, be coming home riding on a lion; a teacher has jumped on a desk because a tiger has entered the room. This intruding element is always a man, a boy, or an animal. If it is a dog, it is always expressly a boy’s dog. A family consisting exclusively of women and girls or with a majority of women and girls is disturbed and endangered. Strangely enough, however, this idea of an intruding creature does not lead to the defensive erection of walls or to the closing of doors. Rather, the majority of these intrusions have an element of humor and of pleasurable excitement and occur in connection with open interiors consisting of circular arrangements of furniture.

To indicate the way in which such regularities became apparent through exceptions to the rule, we wish to report briefly how three of these “intrusive” configurations came to be built by boys. Two were built by the same boy in two successive years. Each time a single male figure, surrounded by a circle of furniture, was intruded upon by wild animals. This boy at the time was obese, of markedly feminine build, and, in fact, under thyroid treatment. Shortly after this treatment had taken effect, the boy became markedly masculine. In his third construction he built one of the highest and slenderest of all towers. Otherwise, there was only one other boy who, in a preliminary construction, had a number of animals intrude into an “open interior” which contained a whole family. When already at the door, he suddenly turned back, exclaimed that “something was wrong,” and with an expression of satisfaction, rearranged the animals along a tangent which led them close by but away from the family circle.

Inclosures are the largest item among the configurations built by girls, if, as pointed out, we consider primarily those inclosures which include a house interior. These inclosures often have a richly ornamented gate (the only configuration which girls care to elaborate in detail); in others, openness is counteracted by a blocking of the entrance or a thickening of the walls. The general clinical impression here is that high and thick walls (such as those in Victoria’s construction) reflect either acute anxiety over the feminine role or, in conjunction with other configurations, acute oversensitiveness and self-centeredness. The significantly larger number of open interiors and simple inclosures, combined with an emphasis, in unique details, on intrusion into the interiors, on an exclusive elaboration of doorways, and on the blocking-off of such doorways seems to mark open and closed as a feminine variable.

Interpretation of Results

The most significant sex differences in the use of the play space, then, add up to the following picture: in the boys, the outstanding variables are height and downfall and motion and its channelization or arrest (policeman); in girls, static interiors, which are open, simply inclosed, or blocked and intruded upon.

In the case of boys, these configurational tendencies are connected with a generally greater emphasis on the outdoors and the outside, and in girls with an emphasis on house interiors.

The selection of the subjects assures the fact that the boys and girls who built these constructions are as masculine and feminine as they come in a representative group in our community. We may, therefore, assume that these sex differences are a representative expression of masculinity and of femininity for this particular age group.

Our group of children, developmentally speaking, stand at the beginning of sexual maturation. It is clear that the spatial tendencies governing these constructions closely parallel the morphology of the sex organs: in the male, external organs, erectible and intrusive in character, serving highly mobile sperm cells; internal organs in the female, with vestibular access, leading to statically expectant ova. Yet only comparative material, derived from older and younger subjects living through other developmental periods, can answer the question whether our data reflect an acute and temporary emphasis on the modalities of the sexual organs owing to the experience of oncoming sexual maturation, or whether our data suggest that the two sexes may live, as it were, in time-spaces of a different quality, in basically different fields of “means-end-readiness.”11

In this connection it is of interest that the dominant trends outlined here seem to parallel the dominant trends in the play constructions of the college students in the exploratory study previously referred to. There the tendency was, among men, to emphasize (by dramatization or avoidance) potential disaster to women. Most commonly, a little girl was run over by a truck. But while this item occurred in practically all cases in the preliminary and abortive constructions, it remained a central theme in fewer of the final constructions. In the women’s constructions, the theme of an insane or criminal man was universal: he broke into the house at night or, at any rate, was where he should not be. At the time we had no alternative but to conclude tentatively that what these otherwise highly individual play scenes had in common was an expression of the sexual frustration adherent to the age and the mores of these college students. These young men and women, so close to complete intimacy with the other sex and shying away only from its last technical consummation, were dramatizing in their constructions (among other latent themes) fantasies of sexual violence which would override prohibition and inhibition.

In the interpretation of these data, questions arise which are based on an assumed dichotomy between biological motivation and cultural motivation and on that between conscious and unconscious sexual attitudes.

The exclusively cultural interpretation would grow out of the assumption that these children emphasize in their constructions the sex roles defined for them by their particular cultural setting. In this case the particular use of blocks would be a logical function of the manifest content of the themes presented. Thus, if boys concentrate on the exterior of buildings, on bridges and traffic lanes, the conclusion would be that this is a result of their actual or anticipated experience, which takes place outdoors more than does that of girls, and that they anticipate construction work and travel while the girls themselves know that their place is supposed to be in the home. A boy’s tendency to picture outward and upward movement may, then, be only another expression of a general sense of obligation to prove himself strong and aggressive, mobile and independent in the world, and to achieve “high standing.” As for the girls, their representation of house interiors (which has such a clear antecedent in their infantile play with toys) would then mean that they are concentrating on the anticipated task of taking care of a home and of rearing children, either because their upbringing has made them want to do this or because they think they are supposed to indicate that they want to do this.

A glance at the selection of elements and themes in their relation to conscious sex roles demonstrates how many questions remain unanswered if a one-sided cultural explanation is accepted as the sole basis for the sex differences expressed in these configurations.

If the boys, in building these scenes, think primarily of their present or anticipated roles, why are not boy dolls the figures most frequently used by them? The policeman is their favorite; yet it is safe to say that few anticipate being policemen or believe that they should. Why do the boys not arrange any sport fields in their play constructions? With the inventiveness born of strong motivation, this could have been accomplished, as could be seen in the construction of one football field, with grandstand and all. But this was arranged by a girl who at the time was obese and tomboyish and wore “affectedly short-trimmed hair”—all of which suggests a unique determination in her case.

As mentioned before, during the early stages of the study, World War II approached and broke out; to be an aviator became one of the most intense hopes of many boys. Yet the pilot shows preferred treatment in both boys and girls only over the monk, and—over the baby; while the policeman occurs in their constructions twice as often as the cowboy, who certainly is the more immediate role-ideal of these western boys and most in keeping with the clothes they wear and the attitudes they affect.

If the girls’ prime motivation is the love of their present homes and the anticipation of their future ones to the exclusion of all aspirations which they might be sharing with boys, it still would not immediately explain why the girls build fewer and lower walls around their houses. Love for home life might conceivably result in an increase in high walls and closed doors as guarantors of intimacy and security. The majority of the girl dolls in these peaceful family scenes are playing the piano or peacefully sitting with their families in the living-room; could this be really considered representative of what they want to do or think they should pretend they want to do when asked to build an exciting movie scene?

A piano-playing little girl, then, seems as specific for the representation of a peaceful interior in the girls’ constructions as traffic arrested by the policeman is for the boys’ street scenes. The first can be understood to express goodness indoors; the second, a guarantor of safety and caution outdoors. Such emphasis on goodness and safety, in response to the explicit instruction to construct an “exciting movie scene,” suggests that in these preadolescent scenes more dynamic dimensions and more acute conflicts are involved than a theory of mere compliance with cultural and conscious ideals would have it. Since other projective methods used in the study do not seem to call forth such a desire to depict virtue, the question arises whether or not the very suggestion to play and to think of something exciting aroused in our children sexual ideas and defenses against them.

All the questions mentioned point to the caution necessary in settling on any one dichotomized view concerning the motivations leading to the sex differences in these constructions.

The configurational approach, then, provides an anchor for interpretation in the ground plan of the human body; here, sex difference obviously provides the most significant over-all differentiation. In the interplay of thematic content and spatial configuration, then, we come to recognize an expression of that interpenetration of the biological, cultural, and psychological, which, in psychoanalysis, we have learned to summarize as the psychosexual.

In conclusion, a word on the house as a symbol and as a subject of metaphors. While the spatial tendencies related here extend to three-dimensionality as such, the construction of a house by the use of simple, standardized blocks obviously serves to make the matter more concrete and more measurable. Not only in regard to the representation of sex differences but also in connection with the hypochrondriac preoccupation with other growing or afflicted body parts, we have learned to assume an unconscious tendency to represent body and its parts in terms of a building and its parts. And, indeed, Freud said fifty years ago when introducing the interpretation of dreams: “The only typical, that is to say, regularly occurring representation of the human form as a whole is that of a house.”12

We use this metaphor consciously, too. We speak of our body’s “build” and of the “body” of vessels, carriages, and churches. In spiritual and poetic analogies, the body carries the connotation of an abode, prison, refuge, or temple inhabited by, well, ourselves: “This mortal house,” as Shakespeare put it. Such metaphors, with varying abstractness and condensation, express groups of ideas which are sometimes too high, sometimes too low, for words. In slang, too, every outstanding part of the body, beginning with the “underpinnings,” appears translated into metaphors of house parts. Thus, the face is a “façade,” the eyes “front windows with shutters,” the mouth a “barn door” with a “picket fence,” the throat a “drain pipe,” the chest a “bone house” (which is also a term used for the whole body), the male genital is referred to as a “water pipe,” and the rectum as the “sewer.” Whatever this proves, it does show that it takes neither erudition nor a special flair for symbolism to understand these metaphors. Yet, for some of us, it is easier to take such symbolism for granted on the stage of drama and burlesque than in dreams or in children’s play; in other words, it is easier to accept such representation when it is lifted to sublime or lowered to laughable levels.

The configurational data presented here points primarily to an unconscious reflection of biological sex differences in the projective utilization of the play space; cultural and age differences have been held constant in the selection of subjects. As for play themes, our brief discussion of possible conscious and historical determinants did not yield any conclusive trend; yet it is apparent that the material culture represented in these constructions (skyscrapers, policemen, automobiles, pianos) provides an anchor point for a reinterpretation of the whole material on the basis of comparisons with other cultures. In such comparisons houses again mean houses; it will then appear that the basic biological dimensions elaborated here are utilized at the same time to express different technological space-time experiences. Thus it is Margaret Mead’s observation that in their play Manus boys who have grown up in huts by the water do not emphasize height, but outward movement (canoes, planes), while the girls, again, concentrate on static houses. It is thus hoped that the clear emphasis in this paper on the biological will facilitate comparative studies, for cultures, after all, elaborate upon the biologically given and strive for a division of labor between the sexes and for a mutuality of function in general which is, simultaneously, workable within the body’s scheme and life-cycle, meaningful to the particular society, and manageable for the individual ego.

Case Illustrations*

Now as I show you some pictures, I wish you would pay attention to whether there are blocks at all, or whether there aren’t; if there are blocks, whether they make for high buildings or low buildings, whether the buildings are open or closed, whether the whole construction is in the foreground or in the background; and whether the buildings contain people and animals or are surrounded by people and animals. The sex differences lie in these simplest spatial relationships.

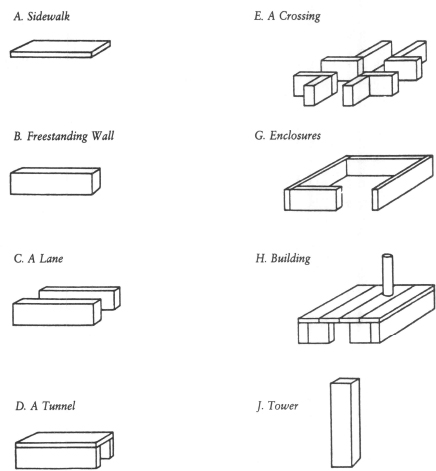

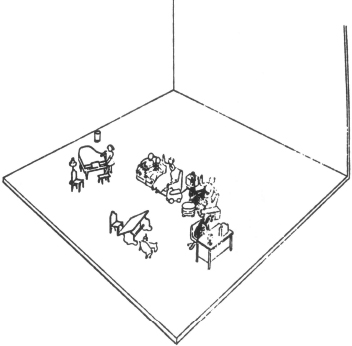

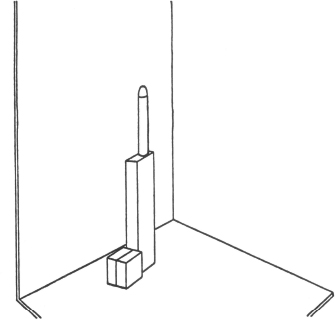

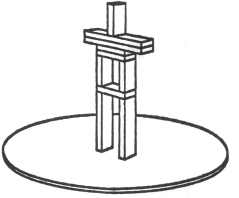

Figure 1

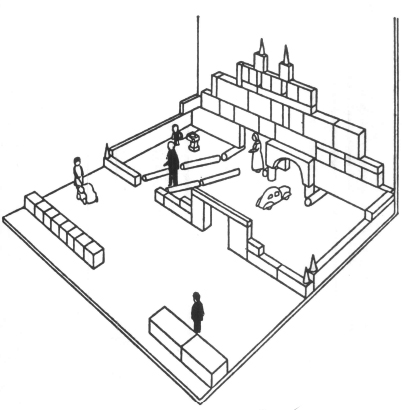

Fig. 1, I would classify as an open interior. There are no walls around the house, nor walls separating the different rooms of the house. This is a kind of construction which occurs significantly more often in girls’ scenes.

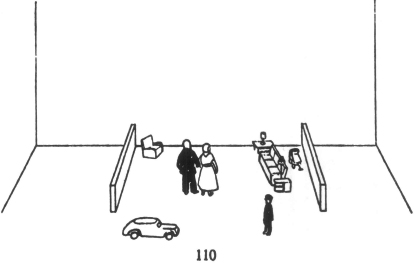

Fig. 2 is what I would call a “low inclosure.” A low inclosure is one that is only one block high, has no ornaments, no roof, no tower, but on occasion an “elaborate front door.” This again is on the whole a feminine construction. Boys build such inclosures primarily in connection with more complicated structures. In this case, the low inclosure is attached to the background, in fact, it opens up toward the wall.

Fig. 3 is a very feminine configuration. There are not only no walls, but a round arrangement of furniture, with either an animal or a male breaking into the circle. Sometimes both appear—such as father coming home on a lion and right behind him, upholding a semblance of law and order, a policeman. The Fig. 3 configuration was done by an Italian-American girl. You see how visibly excited that family is. The child spent quite some time turning their arms up in the air. The exciting thing is that a little pig has run into the family house, and in this case it is not the policeman but the dogs who are trying to protect the house.

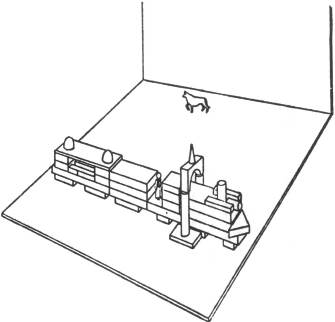

Figure 2

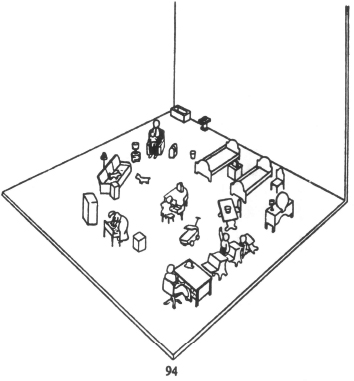

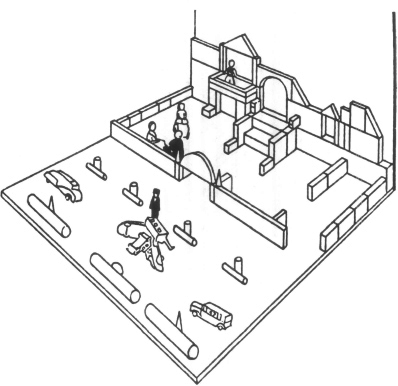

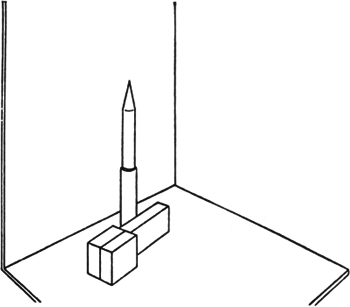

Fig. 4 is a boy’s construction: a locomotive constructed out of blocks. I would definitely call this an “elaborate building,” and as a building it is very masculine construction. Yet, when I asked the boy, “What is so exciting about it?” he said that is a very, very narrow bridge which that train has to squeeze through. This boy had an acute and painful phimosis. Thus what dominates at the moment as a discomfort or a conflict enters by way of a unique detail in what otherwise is a normal and in fact outstanding performance.

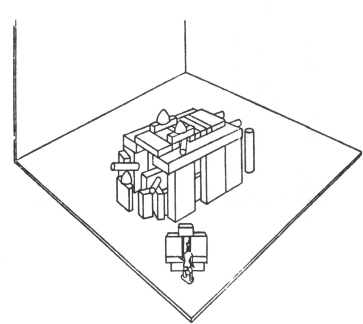

Fig. 5 is a typical boy’s construction. There is an Indian who wants to attack a fort, which, as you see, has many guns. Boys, more often than girls, erect buildings, cover them with roofs, provide them with ornaments and other items which stick out: towers, guns, etc.

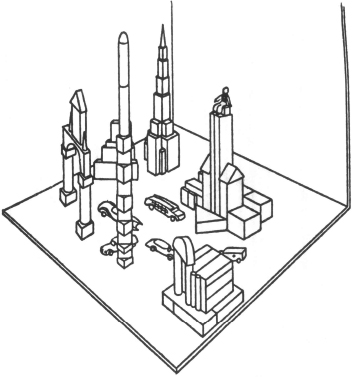

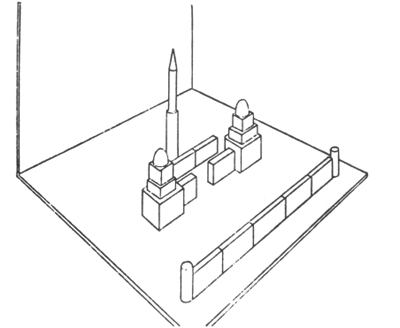

I do not need to point out that Fig. 6 is a boy’s construction. it is almost too masculine. It isn’t just height that is masculine. In connection with the highest towers and buildings there is in the exciting or unique element a downward trend, as if such height went too far. He “stuck his neck out.” In this case, the exciting element is that the proud boy sitting on top of the world is really insane, and in fact, on top of a sanatorium.

Figure 3

Fig. 7 is by a boy who at the time was highly dependent on his mother, and with a certain “façade” of aloofness. This is expressed by a high façade, leaning against the background. But not only that. When I asked him, “What is the exciting element?” he said that this man (the “father”) has placed some bombs underneath that façade. You can see the cylinders. So here again, his high façade, if you pushed slightly, would collapse. But now let’s see how such a theme may develop as time passes.

Fig. 8 shows his later construction, again a façade, this time well founded, but still against the background. The boy standing there, high and mighty. The same cylinders which before had represented bombs are now out here, each one kept by a peg from rolling towards the building. So he has regained safety. I cannot go now into that critical year in the family history.

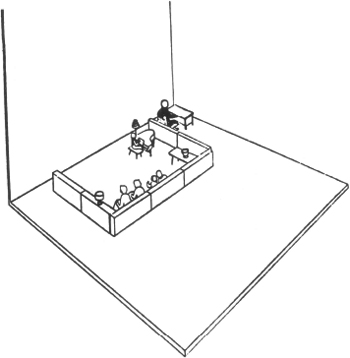

Fig. 9 you may also find too good to be true. Here is the only child whose mother came in with her. I had to ask the mother to wait outside.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

This child builds a boardwalk against the back wall, and another one coming out into space. Not a diagonal then, but two separate tendencies, to hang on to the background and to come out. Let me show how the repetition of a theme underlines this configuration. Here is a cowboy guarding a bull. Here is a policeman guarding a bear, a tiger and a lion. Here is an Indian guarding the baby. So that you see that in content and form the emphasis is on the “Mother watches over me, I hang on to her.” In this particular case, attempt at a symbiosis with the mother was clinically evident.

Incidentally, only two children ignored the table altogether. One was this girl, the other a very meek little black boy. He built under the table. He nearly made me cry. He didn’t dare to build where the others did.

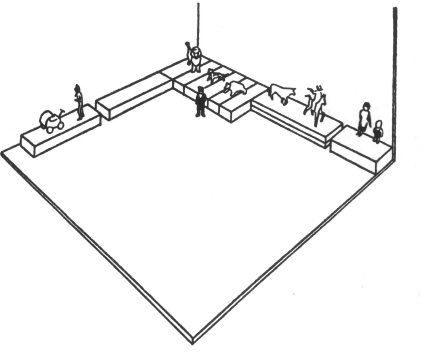

Fig. 10 is the construction made by the same girl half a year later. The conflict over emancipation from the mother is now more clearly counterpointed. There is a “tower,” hugging the background, and there is a boardwalk reaching out, and the children sit and watch the world go by. Such changes in configuration often correspond to clear-cut changes in the interview material secured by other workers. Incidentally, the only high towers built by girls are in the back third of the table, and the highest tower built by any girl was built on the shelf back behind the table.

Figure 9

Figure 10

Fig. 11 is an example of the development of one theme during one session. This boy was an enuretic. He started with this phallic tower out in the foreground. Then he took the tower down. His configuration then went downward and backward to Fig. 12. He moved it into the background, and made it a low inclosure such as is typical for girls. At the same time, his final story “regressed,” as it were, for it concerned a sleeping baby.

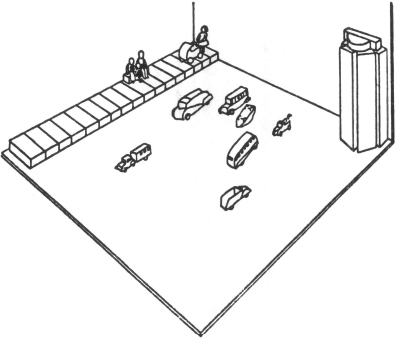

Yes. In later constructions he overcame these trends. Here in Fig. 13 is his brother, at the time more “outgoing” and more masculine. The similarity of initial configuration is uncanny. I do not believe that he could have possibly known what his brother had built. He starts with a phallic tower of more moderate height. But then (Fig. 14) he builds outward, retaining the tower, and adds what I call a “barrier”—an exclusively male configuration. By the same token his story is concrete and up-to-date; this represents the entrance to the San Francisco World’s Fair.

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Notes*

1 Erikson, 1937, 1938, 1940.

2 Erikson, 1938.

3 Erikson, 1937; see also Rosenzweig and Shakow, 1937.

4 The author is indebted for this opportunity to Dr. Jean W. Macfarlane, director of the Guidance Study, Institute of Child Welfare, University of California, Berkeley. The Guidance Study, in the words of its director, is “a 20-year cumulative study dedicated to the investigation of physical, mental, and personality development” (Macfarlane, 1938). Its subjects were “more than 200 children arbitrarily selected upon the basis of every third birth during a given period in Berkeley, California.” The children were matched at birth on certain socioeconomic factors and divided into a guidance group and a control group. The study thus provided for “cumulative observation of contemporaneous adjustments and maladjustments in a normal sample.”

5 At the time of this investigation, the author was not familiar with the much more comprehensive “world-play” method of Margaret Lowenfeld in England (Lowenfeld, 1939).

6 The emphasis on the element of “excitement” warrants an explanation. In the exploratory study mentioned above (Erikson, 1938), Harvard and Radcliffe students had been asked to build “a dramatic scene.” All English majors educated in the imagery of the finest in English drama, they were observed to build scenes of remarkably little dramatic flavor. Instead, they seemed to be overcome by a kind of infantile excitement, which—on the basis of an extensive data collection—could be related to childhood traumata. Conversely, a group of psychology students in another university, who decided to employ a short cut by asking their subjects to build “the most traumatic scene of their childhood,” apparently aroused resistance and produced scenes characterized by a remarkable lack of overt excitement of any kind, by a dearth in formal originality, and by the absence of relevant biographic analogies. These experiences suggested, then, that we should ask our preadolescents for an exciting scene in order to establish a standard against which the degree and kind of dramatic elaboration could be judged, while this suggestion as well as the resistance provoked by it could be expected to elicit lingering infantile ideas.

7 Honzik, 1951.

8 All names are, of course, fictitious, and facts which might prove identifying have been altered.

9 An analysis of the sex differences in the occurrence of blocks and toys in the play constructions of these preadolescents has been published by Dr. Marjorie Honzik. For a systematic configurational analysis and for a statistical evaluation see the original article (Honzik, 1951). The writer is indebted to Dr. Honzik and also Drs. Frances Orr and Alex Sherriffs for independent “blind” ratings of the photographs of the play constructions.

10 One single girl built a ruin. This girl, who suffered from a fatal blood disease, at the time was supposed to be unaware of the fact that only a new medical procedure, then in its experimental stages, was keeping her alive. Her story presented the mythological theme of a “girl who miraculously returned to life after having been sacrificed to the gods.” She has since died.

11 For an application of the configurational trends indicated here in a masculinity-femininity test cf. Franck, 1946. See also Tolman, 1932.

12 Freud, 1922.

List of References

ERIKSON, ERIK HOMBURGER. 1937. “Configurations in Play,” Psychoanalytic Quarterly, VI, 2, 139–214.

——. 1938. “Dramatic Productions Test.” In Explorations in Personality, ed. H. A. MURRAY. New York: Oxford University Press.

——. 1940. “Studies in the Interpretation of Play. I. Clinical Observation of Play Disruption in Young Children.” Genetic Psychology Monographs, XXII, 557–671.

——. 1951. “Sex Differences in the Play Configurations of Preadolescents,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, XXI, 4, 667–92.

FRANCK, K. 1946. “Preference for Sex Symbols and Their Personality Correlation,” Genetic Psychology Monographs, XXXIII, 2, 73–123.

FREUD, S. 1922. Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

HONZIK, M. P. 1951. “Sex Differences in the Occurrence of Materials in the Play Constructions of Preadolescents,” Child Development, XXII, 15–35.

LOWENFELD, M. 1939. “The World Pictures of Children: A Method of Recording and Studying Them,” British Journal of Medical Psychology, XVIII, Part I, 65–101.

MACFARLANE, J. W. 1938. Studies in Child Guidance. I. Methodology of Data Collection and Organization. (“Society for Research in Child Development Monographs,” III, 6.)

ROSENZWEIG, S., and SHAKOW, D. 1937. “Play Technique in Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, VII, 12, 32–47.

TOLMAN, E. C. 1932. Purposive Behavior in Animals and Men. New York: Century Co.

Maria Piers’s benevolent planning has made me the last speaker in this series of symposia and permits me to do two things—one hardly dreamt of, the other habitual throughout my professional life. I never dreamt of having the last word after Konrad Lorenz, Jean Piaget, and René Spitz. And I welcome the opportunity after numerous digressions to turn once more to the play of children—an infinite resource of what is potential in man. I will begin, then, with the observation of one child’s play and then turn to related phenomena throughout the course of life, reflecting throughout on what has been said in these symposia.

In the last few years Peggy Penn, Joan Erikson, and I have begun to collect play constructions of four-and five-year-old children of different backgrounds and in different settings, in a metropolitan school and in rural districts, in this country and abroad. Peggy Penn acts as the play hostess, inviting the children, one at a time, to leave their play group and to come to a room where a low table and a set of blocks and toys await them. Sitting on the floor with them, she asks each child to “build something” and to “tell a story” about it. Joan Erikson occupies a corner and records what is going on, while I, on occasion, replace her or (where the available space permits) sit in the background watching.

Figure 1

It is a common experience, and yet always astounding, that all but the most inhibited children go at such a task with a peculiar eagerness. After a brief period of orientation when the child may draw the observer into conversation, handle some toys exploratively, or scan the possibilities of the set of toys provided, there follows an absorption in the selection of toys, in the placement of blocks, and in the grouping of dolls, which soon seems to follow some imperative theme and some firm sense of style until the construction is suddenly declared finished. At that moment, there is often an expression on the child’s face which seems to say that this is it—and it is good.

Let me present one such construction as my “text.” I will give you all the details so that you may consider what to you appears to be the “key” to the whole performance. A black boy, five years of age, is a vigorous boy, probably the most athletically gifted child in his class, and apt to enter any room with the question “Where is the action?” He not only comes eagerly, but also builds immediately and decisively a high, symmetrical, and well-balanced structure. (See Fig. 1). then does he scan the other toys and, with quick, categorical moves, first places all the toy vehicles under and on the building. Then he groups all the animals together in a scene beside the building, with the snake in the center. After a pause, he chooses as his first human doll the black boy, whom he lays on the very top of the building. He then arranges a group of adults and children with outstretched arms (as if they reacted excitedly) next to the animal scene. Finally he puts the babies into some of the vehicles and places three men (the policeman, the doctor, and the old man) on top of them. That is it.

The boy’s “story” follows the sequence of placements: “Cars come to the house. The lion bites the snake, who wiggles his tail. The monkey and the kitten try to kill the snake. People came to watch. Little one (black boy) on roof is where smoke comes out.”

The recorded sequence, the final scene as photographed, and the story noted down all lend themselves to a number of research interests. A reviewer interested in sex differences may note the way in which, say, vehicles and animals are used first, as is more common for boys; or he may recognize in the building of a high and façade like structure something more common for urban boys. Another reviewer may point to the formal characteristics of the construction—which are, indeed, superior. The psychoanalyst will note aggressive and sexual themes not atypical for this age, such as those connected here with the suggestive snake. The clinician might wonder about the more bizarre element, added almost as a daring afterthought, that of men of authority (doctor, policeman, old man) being placed on top of the babies. Such unique terms, however, escape our comprehension in this kind of investigation, and this usually for lack of intimate life data.