“The most creative producer I have worked with is Lorenzo O’Brien. His talents include handling enormous numbers of people with great tact and efficiency, protecting the director from unnecessary slings and arrows, and providing unusually perceptive script and story notes. On one occasion he provided me with the entire script, El Patrullero (Highway Patrolman), and then found us the money to make it. I owe Lorenzo the best work of my career.”

—Alex Cox, Writer, Actor, Director, Repo Man, Sid and Nancy, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

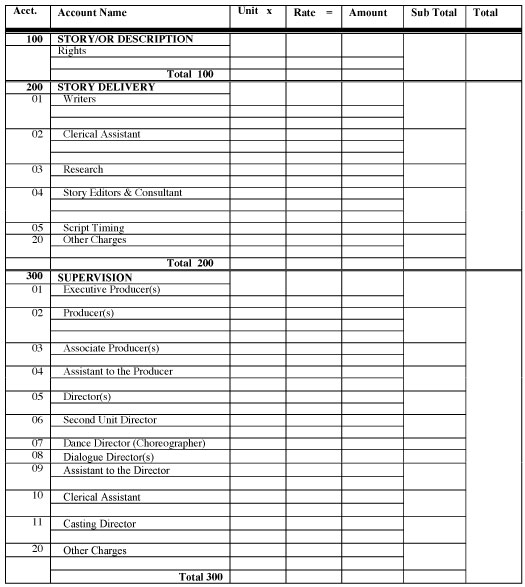

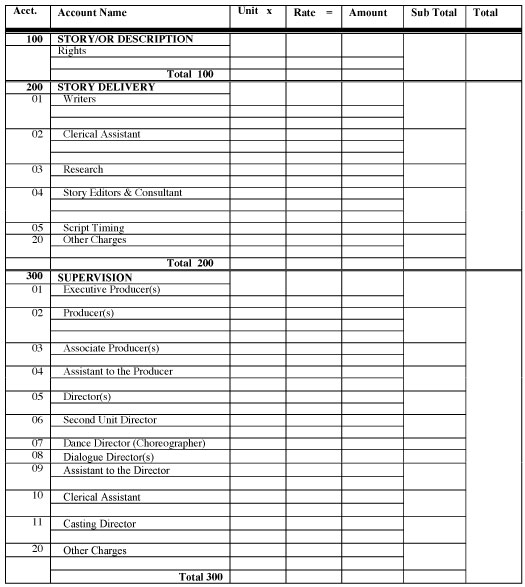

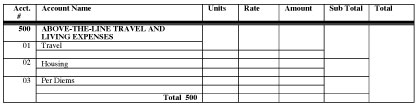

We begin our discussion of above-the-line cost items and their relationship to the creative process by examining the cost centers indicated in Figure #12. A project’s origin begins with the rights to the project. If a project originates with a book or a newspaper article, then the producer must acquire the rights to that book or article before a screenplay can be written. If a screenplay is an original screenplay, then the producer is purchasing the rights to the story that is inherent in the screenplay as well as the screenplay itself. No matter what the project, there will be underlying rights that must be optioned or purchased.

The rights must be in writing and it is important that you do due diligence in finding the existence of any underlying rights. A handshake deal is not enough. Not only is getting things in writing good business practice, in this case it is necessary in order to obtain an Errors and Omissions Insurance policy (see Chapter 10). Being able to get an E&O policy is a mandatory delivery item for distribution. This relates to the “end result” concept of producing and becomes evident when you analyze the process from Z to A as mentioned in Chapter 2.

During the development stage of Hunter’s Blood, the executive producer needed to make a film for no more than $1,000,000, since she felt she could raise that amount easily. So we looked around for a project that had interesting character points and could be made for under $1,000,000.

Figure 12

Note: Units in the budget are by weeks, months, footage or flat. Unit × Rate = Amount (Example: 4 wk. × 2000 = 8000)

The original screenplay for the project was submitted through a writer’s representative. Upon reading it, I found myself interested in the clash of cultures that existed in the story and the notion that the characters who appeared to be the “good guys” were really the guys who initiated the trouble and upset the sociological culture of another group of people. Although the screenplay was weak and had exploitive elements (like cannibalism and salacious nudity), I was led to the same conflict of culture issue that had been part of the John Boorman film Deliverance. I knew Hunter’s Blood could be made for under $1,000,000. When I asked about the origin of the story, I was told that it was based upon a “pulp novel” of the same name written by Jere Cunningham. We have all seen those types of books in the supermarket or on the rack in a convenience store. Their cover artwork designed to intrigue every man who might peruse the stand, just as romance novel covers are meant to attract women. The writers’ representative told me that his client had optioned the novel at one time in order to write the screenplay on speculation and that the writer no longer owned the rights to the story. I researched the rights to the novel, found they were available and that its author had recently signed with Creative Artists Agency for representation as a writer of feature films. I contacted his agent, who turned out to be someone I had known for years (relationships). Although he knew of Cuningham’s screenplays he had never heard of this novel. I was honest with the agent and told him what we wanted to do and the agent allowed us an exclusive short-term free option to the rights in order to raise the funds to do the project.

Several years ago I was the creative producer of the development of the New York stage production of On the Waterfront. The notion to do this as a play came from my experiences in working with actors on scenes from the film, and my realization that the film had all the elements of good theater. I was under contract to Columbia at the time and was able, through studio research, to find out that neither the studio nor Sam Spiegel owned the rights for a stage presentation. The original agreement indicated that these rights reverted back to Budd Schulberg, the author of the screenplay. After contacting Budd, he informed me that he had also written a novel called Waterfront and that the movie’s screenplay was based on a series of articles in a New Jersey newspaper detailing mob like crimes on the docks of New York. On advice of our attorney we needed to obtain the rights to both the novel and the articles before proceeding with the play. They and the screenplay became part of the entire rights deal before the play was written.

Once we had a green light, the purchase price for the rights to the novel was to be $15,000. Two percent of the budget, or $20,000, was allocated towards acquiring the rights and the screenplay. The writer of the screenplay was not a member of the Writers Guild of America so we were not bound by WGA minimums. The original screenplay, written on speculation, was no good without the underlying rights, which we now owned. So we offered the screenwriter $5,000 for the screenplay that he wrote several years before. For that amount we also wanted one supervised rewrite to make the shoe fit the creative parameters of the foot. He agreed to this arrangement.

The writer writes the narrative or screenplay. Often more than one writer works on a project and the structure of each writer’s deal can vary depending on the needs of the project. In the entertainment industry the employment of professional writers of movies and television shows is often (but not always) governed by the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and the 1998 Theatrical and Television Basic Agreement. The present agreement includes a standard Internet contract for writers. In general, the agreement is for writers who render their services in the United States or Canada or whose deals were negotiated in the United States. This also applies to those writers who live in the United States but who are transported abroad for their services. The agreement covers most forms of writing, from the original story and screenplay to simple polishes that a producer may want for a screenplay. It is important to note that the writer must be a dues paying member of the WGA and the production company must be a signatory to the WGA in order for this agreement to be binding. WGA members are not permitted to work for a non-signatory production entity, and a signatory production entity is not permitted to hire a writer who is not a member of the WGA. Also, the Writers Guild requires scripts to be submitted to signatory producers or companies only through qualified agents, managers or attorneys. So understanding how this guild works in relationship to the industry is important.

Deal Memo–A short, written statement outlining the terms of an agreement. It outlines information regarding services, compensation, etc., and, if not used as a final contract signed by both parties, can serve as the basis for further negotiation or for preparation of a lengthier or union-required contract. Until a formal contract is drawn and signed, the deal memo is fully binding to all parties.

First Look–A deal wherein a company has the first right of refusal on a project.

Greenlight–When a production is given the go-ahead from a studio.

WGA–Writers Guild of America, in the United States, the union for film, television and radio scriptwriters. Writers Guild of America, East, headquartered in New York City, represents scriptwriters east of the Mississippi River; Writers Guild of America, West, headquartered in Los Angeles, represents scriptwriters west of the Mississippi River. The two are affiliated; each offers a script registration service to members and nonmember writers.

The guild requires the production entity to be responsible for writers’ pension, health and welfare, and residual payments under the agreement. A residual payment is made when the project is distributed in various markets (free television, pay television, basic cable, internet, CD-ROM, DVD, multimedia games, etc.)

It is not uncommon for non-guild writers to use the basic wage scale terms of the WGA as a yardstick for their deals with a producer. Flat compensation for theatrical features is based upon the stated verified budget of the project. A project budgeted less than $5,000,000 is considered low budget and a project higher than that amount is considered high budget. As an example of the rates under the current agreement, a scale rate for an original screenplay, including a treatment, for a low budget feature is $43,930, and for a high budget feature is $82,444. This may change after the new contract is negotiated with the Writers Guild in June of 2001. Scale is the minimum a producer can pay. When a scale deal is negotiated (of any sort, with any guild) it is negotiated as a scale plus 10 percent deal, as agents are not permitted, by their sanctions with the guilds, to take a commission from their clients when they work for guild minimum. The 10 percent goes to the agent of the writer, director or actor. You should check with the Writers Guild (www.wga.org) to get the specific terms and details of their various agreements, which include theatrical, television, documentary, reality, news and promotional, game show, and new media. There are also compilation books that provide a digest of all guild and union agreements.

Many times a producer will option a writer’s work before purchasing the project. An option is an agreement that gives the exclusive rights to a literary property, such as a novel or play, for a period of time (the term of the option), in order to turn the property into a motion picture or video. The acquisition of literary rights can be structured as an outright purchase or as an option/purchase agreement. Producers often prefer to take an option on a property to reduce the up-front risk. A fee is paid against (or in addition to) the agreed upon purchase price and authors of any literary works must warrant that they own free and clear, all the rights they are selling.

An option gives the producer the exclusive right to purchase the rights within the period of the option. The exclusivity makes it impossible for someone else to purchase the rights during the option period and for the writer to interfere with the purchasing of those rights. Once the option expires, however, the writer retains the option money and the rights as well. If the option is exercised the producer owns the rights outright. When negotiating the option for a property, you must also negotiate the terms of the purchase so that once the option is exercised the literary purchase agreement is automatically in force. If you enter into an option agreement without negotiating the underlying literary purchase agreement, you have bought a useless option because all you have is the right to enter into an agreement in the future should you want the rights. The writer is under no obligation to sell on the terms you want to propose. One other important thing to remember when negotiating the purchase agreement is to include a provision that states that you are under no obligation to actually produce the project. You want the right to make the project but not be obligated to do so.

You should also seek the rights to renew the option before it expires. In this case you will probably pay an additional fee for the period of the extension but you should do it before your original option period expires. Otherwise the writer can refuse to grant or extend your option. Renewals essentially let you extend your option without exercising it. The standard option fee according to WGA rules is 10 percent of scale and is often for a period of eighteen months. Renewals should be based upon that yardstick.

It is not uncommon for writers to require clerical assistants or researchers for projects. I know one writer who writes through dictation. He spends a great deal of time researching the characters before writing and then when he begins he acts out the characters while his assistant, in shorthand, writes what he says, both the dialogue and the action. A producer may require a writer to work with a consultant or a story editor to help get the screenplay to the point where it is ready for production. These key personnel all assist the writer in delivering the best possible project in a written form.

Colored Pages–Whenever a project has been fully prepared for production and is in the hands of the appropriate personnel, the script pages are usually white. Once revisions of any kind are made, the new pages are printed on colored paper (beginning with blue, then pink, yellow, green, etc). The date of the correction on the page is marked on the top of the page and an asterisk is noted in the margin by the precise changes on the page.

Longform–Narrative television project that is longer than an hour in length.

Spec Script–A screenplay written on speculation. The writer spends his own time and money researching and writing the script, with hopes that a producer will buy it. If a writer sends a spec script directly to a producer who did not request it, it is also called an unsolicited script and may be returned unread. A spec script can also be used as a writing sample, especially by an unproduced or aspiring screenwriter; it also can be submitted in scriptwriting competitions.

Step Deal–A method whereby decisions (and payments) are made at various steps towards completion. This usually pertains to the story and is broken out by synopsis, treatment, first draft, second draft, and final screenplay.

Turnaround–The negotiated right of a writer or producer to submit a project to another studio or network, if the company that developed the property elects not to proceed with production. Typically, the right is subject to the condition that the developing company’s investment is repaid; it also may require the developing company to retain an interest in the film’s earnings.

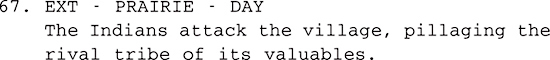

Determining the running time of a script is the function that is often relegated to the continuity person (discussed later) and is called script timing. A scene in a screenplay written as:

is written as 1/8th of a page may take many days of production to shoot and might be seen onscreen for a minute, five minutes or longer. Since it involves a creative relationship to the story, the producer and director should determine its length onscreen. One of Hitchcock’s continuity people once said that one page of script written in proper screenplay format will play 47 seconds onscreen, everything being equal. So a 100 page screenplay should roughly run eighty minutes and a 120 page script, approximately 110 minutes. Some continuity people use the scale of one page equals one minute. Although necessary for television, script timing may not be a necessity for feature films. Commercial television formats rely on precise timing for the insertion of commercials. Therefore it might be beneficial to have a teleplay timed for onscreen running accuracy. The creative side of television requires aesthetics different from theatrical presentations, so the style of production and direction is different. Television makes more use of close-ups, and employs a more confined story structure through the dialogue of the characters rather than the spectacle of production. Whatever the decision might be for having a script timed for running accuracy, preparing for that requires the funds for this line item.

The person responsible for the project being financed is the executive producer. This can be someone who provides the funding for the project or puts elements together (such as the cast or a director) that may trigger the financing. The executive producer’s main duty is usually completed once the project is in pre-production, although they may still be involved in arranging for the distribution of the project. Because of this, the executive producer is generally non-exclusive to a project and may be involved with more than one project at any one time. It would not be unusual to see the salary for an executive producer be lower than a producer’s salary. This may not always be the case since people like Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg, when acting as executive producers, may be receiving a salary equal to or more than the producer’s. Their involvement may have been the reason the project was funded.

The producer is exclusive to a project. The producer’s salary is the only item in your budget that you always have absolute control over. You can determine your own financial needs and structure this area accordingly. If you are a first-time producer, your motivation may be getting the project made and not the amount of money you might earn as the producer. Your ego is motivating you to establish yourself in the profession and you may only be looking for enough money to pay your bills.

On the other hand, if you have a proven track record, your fee may be one that reflects your status and strength on the package of the project. Unless the project is one that an established producer is extremely passionate about, the fee will probably not be any lower than the last project he or she produced. This is especially true if the producer is not a primary owner of the project, but a hired hand.

In some instances it might be necessary for a first time producer to bring aboard an established producer to provide credibility to the project. If that is the case, then more than likely there will be two fees set aside for producing, one lower than the other, to accommodate for two producers. In other instances a project may have a producer whose reputation and expertise is that of a production manager but who wants to be more involved with the creative side of the project along with the management side of the production. In that case, the producing fee may be lower since the person is making a vertical career move to establish themselves as a producer, a practice discussed in Chapter 2. Above-the-line producing salaries are often high because narrative projects today may have three, four and five producers each involved with the project in some way. It is not unusual for the director to also be a producer. Directors are realizing that in order for them to have more creative authority, they have to be a producer on the project.

What is an associate producer? By definition it is someone who is a producing associate given some limited creative responsibility towards the producing of the project. It can be someone who is solely involved with the producer, or someone who may have another responsibility on the project, like editing or production management. The associate producer title may be given to someone in the latter instance if they have been effective in the pre-production creative decisions that involve the producing of a project. The distinguished Film Editor Richard Marks (Broadcast News, Apocalypse Now, Terms of Endearment) was also the associate producer on I’ll Do Anything, a film written and directed by James L. Brooks. An associate producer might be involved only with supervising the post-production on a project or just the day to day activities of the production period. Associate producers do not have as much creative responsibility for the whole project as the producer does, but they assist the producer in achieving certain creative producing assignments. It is also a title that you can keep in your arsenal of negotiating techniques for above-the-line creative talent. Maybe you want to have the writer on the set for necessary rewrites during the production process, and you offer the writer an associate producer credit in an effort to pay less for these and other creative services of the writer. Here this technique approaches two principles discussed in Chapter 2: appealing to the writers’ ego, and elevating the writer to a different category within the industry. A smart producer will not underestimate the value of the associate producer title on a project.

The Director of a project is creatively responsible for the interpretation of the vision and has the final word as to what happens in front of the camera during the production. A wise producer will select a director who shares the same vision of a project and will collaborate to bring the project to fruition. Independent producers in the United States are faced with directors who may or may not be members of the Directors Guild of America (DGA), the bargaining organization representing directors, second unit directors, assistant directors, associate directors and production managers. A director who is not a member of the DGA is free to enter into any agreement with the producer for services on the project, providing the producer’s company is not a signatory to the DGA agreement. If the company has signed an agreement with the DGA then it must only use members of the Guild, or the director it wishes to hire must join the Guild. The strength for the directors in the Guild rests with the production managers, assistant directors and associate directors who also make up its membership. These people provide the primary support for directors to do their jobs successfully and they, through practices established by the DGA, are trained in specific techniques in assisting the director and being responsible for production logistics and schedules.

Minimum fees for DGA (www.dga.org) directors are set by contract with the Guild. It includes theatrical, television, reality, commercial, experimental, low budget or new media. Once a DGA director is employed, he or she is paid regardless of whether the picture is made. This is called pay or play and is required when the producing company is a DGA signatory. When producing a low budget film or a project for the Internet, independent producers often believe that they are not able to use Guild personnel because of their fees. This notion is not true. The Directors Guild has afforded producers with the opportunity to hire its members for independent projects based upon the budget of the project. Briefly stated, a director’s salary is 75 percent of scale for films budgeted between $3.605 million and $7 million and 90 percent of scale for films budgeted between $7 million and $9.5 million with the remaining percentage of the scale wage deferred until break even which is defined as the producer’s total gross receipts equals 200 percent of the production costs. If the budget of the project is at least $2.57 million but less than $3.605 million, the director’s minimum salary is $75,000.

Further, if the budget of the project is at least $1.03 million but less than $2.57 million, all conditions of employment including compensation and deferred compensation are open for negotiations between the producer and the director.

Coverage–(1) A brief analysis of characters and story line of a project as prepared by a story analyst or script reader. The coverage will include a recommendation for any further action on the project. Story analysts are subjective in their views. Many story analysts are writers themselves whose egos often may not permit them to see the potential or the vision of the creative work that is the passion of the producer. (2) Shooting a scene from various angles and setups to provide options for the editor.

Cover Shot–An additional take of a shot that is printed in the event that the preferred take is unusable or damaged. Directors will often do a second take of a shot for safety purposes or in the hopes of getting a better performance from the actors.

DGA–The Directors Guild of America is the collective bargaining unit for directors, assistant directors, stage managers, and production assistants (tape television) in the industry. Founded in 1959. Based in Hollywood, California.

Director’s Cut–(1) Version of a film approved by the director after the initial assembly of footage by the editor; guild contract may allow the director a specified length of time to produce his cut before the producer may suggest changes, if at all. (2) Commercially released version of a film conforming to the director’s personal editing choices; typically, this is a version of the theatrically released film that contains unused or deleted footage. For example, there are six different versions of James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) available on laser disc, many of them featuring special editions, added footage, etc. Also called a director’s special edition.

Finally, if the budget is $1.03 million or less, the producer and director may set any terms they wish including salary and/or deferrals. Similar conditions exist in each of these categories for production managers and assistant directors. In other words, the basic motivation for a director at this level will clearly be his or her own creative ego. (They may even work for food.)

There are also minimums for television work depending on the use for television: i.e. network, syndicated, cable etc. There is also a separate agreement for a standard Internet and new media contracts. Every few years the Guilds negotiate terms and conditions of their contract with the MPAA, so it is wise to check their web site for the latest terms and conditions.

DGA directors are entitled to budget approval and certain creative rights by the terms of their contract, such as a director’s cut. Other issues open for negotiation by all directors (DGA and non-DGA) may include final edit of the project, creative control, casting approval and their choice of assistant directors. These are all issues that must be worked out before the director is hired and are all based upon the producer’s trust and collaborative relationship with the director.

The press sometimes reports directors leaving projects due to “creative differences” with the producer. Although this may or may not be true, certainly when this happens, people are not able to collaborate with one another. The working relationship between the producer and director is the most important working relationship towards the success of a project. While the final responsibility for everything on the project falls in the lap of the producer, directors should keep in mind three basic responsibilities: The first is the responsibility to the audience in telling the story, the second is the responsibility to the producer, without whom there would be no project, and the third is to the director’s creative self. This third responsibility must be nurtured by the creative producer.

There are specific recommended guidelines for producers when working with a director. First, make sure the director has the ability to work with actors or any talent in front of the camera. The only person on a set during the making of the project with that responsibility is the director, and a director who is intimidated by actors, or who cannot communicate with sensitive onscreen talent, will be the downfall of the project. I have seen talent take control of a set when the director did not feel comfortable with their communication. This is not unusual since actors often talk back to directors if they believe the director has not been clear about what is wanted or needed, or if the director has not provided a creative atmosphere in which actors can work.

Second, do not interfere with the director on a set. The director must be absolutely in charge on the shooting set. If a producer interferes with what the director is doing in front of a cast or crew it will demoralize the director and damage the working relationship with the production company. If the producer wants to talk to the director about something during shooting, it is best to do it in private away from the cast and crew or to wait until there is a break, or before or after the day’s work. This way the producer is maintaining the collaborative and respectful process of production.

The medium is collaborative whether you work in film, video or digital. The collaboration begins with the producer and the director and the trust and confidence that each must have with one another. If this is in place then the trust and confidence will be there through the entire production.

Third, and most important, make sure the director does his or her homework on the project. Directing is not only creatively handling actors and interpreting the screenplay, it also includes the ability to complete a day’s work on time and on schedule. A director who is properly prepared allows for the creative, while planning for the inevitable problems. A director who is able to think creatively while making instantaneous decisions based upon the pressures of production is a successful director.

I teach a course at UCLA in the collaborative nature of production between the producer, director and the cinematographer. One year a student producer, who was also the writer of the project, took the course having already had extensive professional experience. He met with one of the directors’ two days before the actual shoot date and planned out the creative aspect of the story they were to shoot on that day. On the day of production the director decided at the last minute to totally change certain characteristics of the main characters, without discussing it beforehand with the producer. On the set the producer tried to carefully adhere to the practice of not interrupting the set activity, and not waiting for a specific break in the activity, quietly addressed the question with the student director. The response he received had no logical answer directed at the story. The student director threw his hands in the air and yelled, “because I want to be creative!” Needless to say, this interaction infuriated the student producer who had a difficult time holding his temper in front of the rest of the student crew and actors. When we talked about the incident later in class, the students all agreed that the director was arbitrary and non-communicative and the producer should have taken the director aside during a lull in the production and discussed the matter in private. The situation never should have happened if the director and producer had discussed the change before coming to the set.

All the previsualization in the world won’t prevent problems from occurring if a director doesn’t have the ability to creatively improvise. Cinematographer Tom Denove tells this story about a director with whom he worked. It was the director’s first picture; his background was in animation and he spent hours doing his homework, elaborately sketching out each shot on paper so he was able to show Tom exactly what he wanted as an image. One day he came to work and, as he faced the set, the door in the set was on the left and the door in his sketch was on the right. He stood and looked at the real set, and then at his sketch, and then back at the real set. He couldn’t figure out how to stage the scene to make it work because the set was not as he had sketched it. Many people, including the actors, gave him suggestions, but he was so locked to his previsualization that he couldn’t unfreeze his thinking to create on the spot. This went on for several hours until he realized that by turning his sketch over and holding it up to the light, the door that was on the right in his sketch was now on the left. He was then able to figure out what to do. But by then time had passed and the day’s work could not be completed on schedule.

Some productions will require a second unit director. Second unit is a second production crew that shoots selected sequences of the production board either before, during or immediately after the main production unit shoots the majority of the project. Many times this involves stunts, special effects, establishing shots or images that do not involve speaking or identifiable cast members. It can also involve shooting performers or main actors on a green- or bluescreen stage for photographic or digital effects as in the case of X-Men, The Cell or The Matrix. The logistics of the production defined by the production board, or by the needs of the director, often dictate the necessity for a second production unit, that is headed up by a second unit director or in some cases, the visual effects supervisor. Collaboration is necessary between the project’s director and the second unit director before second unit production takes place so that the second unit director clearly understands the creative style of the project set by the cinematographer and director. In the case of stunts, the second unit director is often a stunt coordinator who knows the best angle from which to shoot a stunt. A production budget will contain a “mini-crew” just for second unit photography. This is a smaller crew but mirrors the first production unit. (Many directors will do first and second unit direction themselves.)

The casting director is the producer’s face to the acting community during and after pre-production. Selecting the right casting director can give actors’ agents and managers an idea of the quality and integrity of your project. There are many people in the industry who call themselves “casting directors,” and many more being added every month. They may have experience at casting companies as receptionists or assistants, or may have come from the ranks of management, but that doesn’t guarantee they have any real creative casting experience. So check them out for the casting quality. There are several questions that a producer needs to ask about a casting person before hiring their services. What is their casting track record? What projects have they cast recently? Have they worked only on low budget action projects and is your project a romantic comedy? Do they have an excellent creative sense of the characters in the project? A quality casting director can be invaluable to the producer when it comes to finding the right actor for the part.

One of the most important questions a casting director can ask of the producer is; “If you had all the money in the world, whom do you see in these roles?” This question quickly removes any fiscal limitations from a creative casting discussion. What is the casting directors’ relationship to the actor/agent/management community? Find out what their reputation is with producers, agents, actors and managers. Do they primarily work with the “A,” “B” or “C” level theatrical agencies? Agencies sanctioned by the Screen Actors Guild can be classified in terms of the actors they represent. The William Morris Agency, Creative Artist Agency and United Talent Agency are three of many “A” agencies that generally represent actors of excellent quality who may be considered a name, are packagable or are up and coming in the acting community. The size of these agencies varies as many of the smaller “boutique” agencies also fall within this category. These agencies are aggressive and are always seeking new and exciting material for their clients. “B” agencies are smaller agencies that represent quality actors who may be experienced in theater or commercials, but who have little film experience. These agencies are always looking to move their clients up the talent ladder and into new arenas of performance. “C” agencies represent actors with little or no experience. They may be excellent actors but they may or may not be members of the Screen Actors Guild. “C” agencies often work the hardest since their clients are unknown commodities. These agencies deal in volume in the hopes that one of their clients clicks. Casting directors usually work with specific agents and agencies that trust their judgement on projects. These relationships are strong and are based on years of successfully working together. If an “A” agency knows that a casting director they respect is casting a specific project, they may be willing to submit their clients even for smaller or lower budget projects than they might usually consider. The concept of relationships discussed in Chapter 2 is very important to a producer when considering a casting director.

Casting directors usually work on a flat rate for the job, as most of them work as independent entities. The rate will be based upon the amount of casting the producer is asking them to do. You may hire the casting director to cast only certain roles, thereby using the relationships the casting director may have with certain agencies to find specific acting talent. You may decide that you want someone in-house to cast the smaller roles or hire a casting associate to work with the casting director. Or you may want a casting agency to cast the entire project and will negotiate a fee for those services. The fee is generally based upon the budget, the status of the casting agent and the amount of work expected for the project. It will also have a direct correlation to past or ongoing relationships with the producer and the quality of the project. An interesting, exciting and creatively strong project may be enough to motivate a strong and effective casting director. Getting the project to that point will cost you absolutely nothing but your own innate creativity.

When a project is ready to hire actors, casting directors contact the agencies and managers with specific descriptions of the characters that have been approved by the producer. In Los Angeles, Vancouver and New York City, the project is submitted to Breakdown Services, a company that performs a reading and descriptive breakdown of the synopsis and characters for the producer at no charge. They also gather other important information supplied by the producer that may affect actor submissions (union/non-union, etc.). Once Breakdown Services has created the approved information, they send it out to those agencies and managers that subscribe to their service. There are also trade newspapers for actors like Back Stage West and online Internet sites at which a producer may post descriptions of their cast of characters. The producer must be prepared to receive hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of submissions for the project. Weeding through those submissions is a laborious chore best suited for casting agencies. The final decision on casting rests entirely with the producer and director. But a wise producer will find a casting director whose creative instinct for talent can be trusted. Listen to them and consider their ideas carefully. Casting is a very small world, and establishing a supportive relationship with a quality casting director can be very worthwhile.

The single most volatile segment of a production will be within the CAST budget. There are many variables involving the onscreen talent (including their own egos’) that have an impact on what and how they do what they do.

The Screen Actors Guild is the bargaining organization that represents actors in the industry. Producers, of course, can use actors who are not members of this guild. They are referred to as non-SAG actors. In order for an actor to be a member of the Screen Actors Guild, a production company who has agreed to only use SAG actors must hire them. These production companies are called signatory companies. Once a company is a SAG signatory it agrees to use only dues-paying members of the Screen Actors Guild and non-SAG actors are unable to work on the project. A SAG actor who works on a non-signatory project bares the burden of that responsibility, as they can be penalized or even ejected from their guild for doing nonunion work. The producer cannot be held responsible since the company is not a signatory to the Screen Actors Guild. It is therefore critical that the producer makes it clear at the time of the casting announcement as to whether the project is SAG or not. Be warned!

Agents that are franchised by the Screen Actors Guild may not submit their clients to a non-SAG signatory project. Occasionally, an agent who believes in the talent of a non-SAG actor will attempt to find work for the actor in a SAG signatory film. But it is usually very difficult and the main avenues of exposure for that actor lie with student films or nonunion projects. These rarely provide financial incentives for agents but they are necessary for the actor to build a career. Acting for the camera has different technical requirements than acting on the stage and actors must learn both of these techniques. Also actors usually work in student or nonunion films with the promise that they will be given copies of their work which they can include in their product reel. If you make those agreements, make sure you honor them. The actor you work with today may well be the actor you need to get your project made tomorrow.

The independent producer is usually faced with the need to secure “name” acting talent as part of the package to entice the financing of the project. You can rest assured that these actors will be members of the Screen Actors Guild and will only work on signatory productions. It is important to note that SAG has jurisdiction in the United States or any commonwealth, territory or possession of the United States in which the Guild has established a branch. However, if the production company has a representative or is based in the United States and wishes to use an actor who is a member of the Screen Actors Guild, it must become a signatory even if the project is being made outside of the United States. The Guild includes actors, performers, professional singers, stunt performers, stunt coordinators, airplane and helicopter pilots, dancers and puppeteers who appear onscreen. (SAG also covers extras, but only under certain conditions which are discussed later in this chapter.)

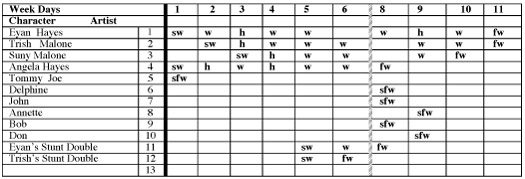

Figure 13

Often new independent producers will feel somewhat intimidated by the size and power of the Screen Actors Guild. They fear that the Guild will make it impossible for them to produce their projects. This statement is far from the truth. The Guild wants their members to work and has become very “producer friendly” in establishing various agreements under which a producer may do a project in film, video or digital. They also recently approved an agreement for their members to work on projects made for the Internet. This agreement provides basic coverage that includes pension and health contributions. It does not as yet specify minimum rates although the producer can negotiate with SAG; the starting salary for negotiations is the basic minimum daily rate of $617. This contract is available from SAG on a case-by-case basis but in the new film and television contract negotiations they will probably seek to include some language that will give more explicit administration over made-for-Internet product.

The Screen Actors Guild recognizes the need for various types of agreements based upon the budget and motivation of the project. They were one of the first Guilds to work with producers and to attempt to structure agreements that allow their members to exercise their creative egos while maintaining dignity and integrity in their work.

All SAG agreements are based entirely on the end use of the project. The Basic Codified Agreement is the basic SAG agreement and includes pay schedules and terms for full budget theatrical feature film, commercials and television.

To qualify for the basic agreement, at least one month prior to the start date of pre-production the producer should contact one of the SAG offices located in twenty-three cities throughout the United States. SAG requires the project to have a verified copyright number issued by the copyright office of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. They will also require a copy of the script and the proposed shooting schedule, after which they will send a packet of documents for the producers’ signature. Within the packet of information will be the minimum (scale) rates for performers who work both on a daily and weekly contract, and information regarding the use of SAG extras in the New York and Los Angeles Zones (discussed later in this chapter). Note: The New York Zone is within 300 air miles from Columbus Circle, including New York City, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. The Los Angeles Zone includes Los Angeles, San Francisco, Sacramento, San Diego, Las Vegas and the islands of Hawaii.

Callback–1. Invitation for an actor to audition again (after the field of competition has been narrowed). For SAG members, there is a limit to the number of callbacks an actor may have before being paid. 2. Actor’s automatic invitation to continue working as a day player, unless specifically notified by the end of the shooting day that he has been laid off.

Drop and Pickup–A specific SAG rule which applies to their basic agreement that states that there must be ten free days between the last day that an actor works and the time he/she next works on a production otherwise payment must be provided for all intervening non working days. This applies to weekly and daily performers and is waived on certain SAG agreements. This rule can be applied once per actor per production.

Principal Players–Members of the cast comprising the main featured actors.

SAG–The Screen Actors Guild is the collective bargaining unit for actors and performers in projects released in film and film television. In the United States, the union for actors working in motion pictures, television and commercial productions shot on film and released on film, videotape or videodisc. Founded in 1933 and based in Hollywood, California, with offices around the United States.

As part of the package of documents the producer will be asked to sign a certificate assigning the negative of the project as security for assurance that their actors will get paid the necessary residual and Pension, Health and Welfare payments upon the project’s exhibition in ancillary and subsequent markets. Once the distribution deal for the project is in place, then the producer must obtain an executed Distributors Assumption Agreement which will release SAG’s security interest in the project’s negative. If the project is made as a theatrical project the producer is entitled to distribute it worldwide theatrically without additional compensation to the actors. When the project is distributed beyond the theatrical market, and moves into ancillary markets (such as foreign, television, Internet and DVD), the producer is required to pay residuals to the principal performers (SAG members). Residuals are paid each calendar quarter and are generally based on a percentage of the Distributor’s Gross Receipts (DGR). The percentage is then divided up amongst the performers based on their salary and the amount of time they worked on the project. These percentages vary on the terms of whatever contract is in force.

The Low Budget Agreement is one that may be used when the producer is doing a project for an initial theatrical release and is 80 minutes or longer but with total budget less than $2,500,000 including all deferments, and shot entirely in the United States. This agreement allows for certain benefits for the producer and the actor. First is the waiving of the consecutive employment policy for day or weekly performers. This allows the performer to be dismissed and recalled for the actual days worked rather than paying the performer for days for which they may be on hold or waiting to be used. This can save the producer and the production the expense of paying an actor who may not be used daily, as the volatility of production can cause a ripple in the production schedule which could force an actor to be rescheduled for another date. The downside of this benefit is that the producer may not ask the actor to be exclusive on days that the actor is not scheduled (the consecutive rule is not waived when the actor is on an overnight location). In addition this benefit allows the actor to work weekends without benefit of weekend premiums. The second benefit is a lower scale rate of salary for weekly and daily performers. As an example: $466 for a daily performer, vs. $617 and $1,620 for a weekly performer, vs. $2,142. The third benefit is that SAG is amenable to reducing the number of extras employed under the extra performers agreement. The fourth and final benefit rests with a reduction in the overtime rate. In this agreement, overtime is paid at 1½ times until the 12th hour and then double time thereafter. It is important to note that if a project is budgeted under $2,000,000 and a producer makes the project under this agreement, the producer must distribute the project theatrically before going to any other markets. If it first plays in another market (such as television or DVD) the project will be upgraded to the terms of the Basic Agreement and the producer will be obliged to pay the difference including the consecutive employment. Thus the need for adhering to the End Result Use theory. SAG encourages the casting of four protected groups of actors and has established the diversity in casting initiative. Under this initiative the budget for a Low Budget Agreement Project may be increased to $3.75 million if the project can demonstrate casting diversity by meeting the following criteria: 50 percent of the total speaking roles and 50 percent of the total days of their employment is cast with actors who are people of color, women, seniors (over sixty) and/or actors with disabilities. And 20 percent of the days of work must be with actors who are either Black, Latino, Asian-Pacific and/or Native American.

This agreement can be applied when the producer is shooting a project in the United States for less than $2,750,000 and is initially for theatrical release. Fifty percent of the roles and the days of work must be for performers of color, women, seniors, and/or performers with disabilities. Twenty percent of the roles and days of work must be for performers who are African-American, Latino, Asian-Pacific or Native American. When applying to SAG for this agreement the producer must present a list of characters identified by category before SAG will provide its approval. The benefits are the same as the previous agreement, except that it permits a ceiling of a higher budget than that for the low budget agreement.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is shooting a project for theatrical release 80 minutes or longer that is shot in the United States for less than $625,000 including all deferments. The production benefits include no consecutive employment (except on overnight locations) and significantly lower scale rates of $248 for a daily performer and $864 for a weekly performer. This agreement also permits the producer to negotiate in good faith with the Guild before hiring extras, and allows for a reduced overtime rate for its performers. The Distributors Assumption Agreement requirement is the same with this agreement as it is with the others regarding residual responsibilities, however under this agreement the percentages of Distributor’s Gross Receipts (DGR) are different than the Low Budget Agreement. SAG encourages the casting of four protected groups of actors and has established the diversity in casting initiative. Under this initiative the budget for a Modified Low Budget Agreement Project may be increased to $937,500 if the project can demonstrate casting diversity by meeting the following criteria: 50 percent of the total speaking roles and 50 percent of the total days of their employment is cast with actors who are people of color, women, seniors (over sixty) and/or actors with disabilities. And 20 percent of the days of work must be with actors who are either black, Latino, Asian-Pacific and/or Native American.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is making a live action feature project that is not produced primarily for commercial exploitation. It cannot cost more than $200,000 excluding all deferments and must be entirely shot in the United States. Under no conditions can the budget including deferrals cost more than $500,000. This agreement is not intended for projects made for television, cable or DVD markets and it explicitly excludes animated projects and music videos. The benefits under this agreement include no consecutive employment (except on overnight locations) and work on weekends with no premium pay. It also covers professional performers and professionals only when they are hired as extras. The rate for these performers is $100 a day. The producer has the right to distribute the project theatrically and if the project is distributed outside the theatrical market residuals must be paid to the actors in accordance with the Basic SAG Agreement.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is shooting a project for the experience of making the project. It is intended to be used when the project is for a workshop or training situations or for noncommercial short films which can be used as showcases of the filmmakers work. The maximum budget of the project is $50,000 with a maximum running time of 35 minutes. It must be shot entirely in the United States. The benefits to the producer include no consecutive employment and completely deferred salaries for the performers although time sheets are kept which include deferred payment for overtime. No premiums are levied and the agreement only covers professionals and does not cover background players. This means that the producer may use SAG players alongside non-SAG players. The producer is entitled to distribute this project at film festivals only and for limited distribution for Academy Award® consideration. If the producer wishes to distribute it beyond film festivals, each SAG performer must be contacted, provide a written consent and negotiate compensation with the producer for any further distribution. This negotiation must reflect the rates in the SAG agreement which is applicable to the initial distribution beyond festivals.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is shooting a project for the experience of doing the project. It cannot cost more that $200,000 and must be entirely shot in the United States. The intention of this agreement is to allow the producer to do a workshop or training project. The benefits under this agreement include no consecutive employment (except on overnight locations) and a six-day workweek with no premium pay. It also covers professional performers and professionals only when they are hired as extras. The rate for these performers is $100 a day when they have one or two days that are guaranteed, and $75 a day when three days are guaranteed. The producer is free to distribute this project only in film festivals, limited run art houses, or on basic cable and public television that allow for an “experimental/independent producer” type of format. Any other type of distribution will require the professionals’ (SAG performers) salaries to be upgraded to the rates in the SAG agreement that is applicable to the form of distribution. The residual payments that are due beyond the initial distribution market are the same as the Modified Low Budget Agreement.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is shooting a project for the experience of making the project. It is intended for projects that are workshops or training situations. The total budget of the project must be less than $75,000, and the project must be shot entirely in the United States. The benefits to the producer include no consecutive employment and completely deferred salaries for the performers. No premiums are levied and the agreement only covers professionals. This means that the producer may use SAG players alongside non-SAG players. The producer is entitled to distribute this project at film festivals only and for limited distribution for Academy Award® consideration. If the producer wishes to distribute it beyond film festivals, each SAG performer must be contacted, provide a written consent and negotiate compensation with the producer for any further distribution. This negotiation must reflect the rates in the SAG agreement, which are applicable to the initial distribution beyond festivals.

Pictures Gross–The gross revenue a project earns before expenses are assessed to the project. Box-office grosses are part of the Pictures Gross.

Producers Gross–Producers profit revenue before expenses.

Producers Net–Producers profit revenue after expenses.

This agreement is applicable when the producer is a bona fide student shooting a project affiliated with their course of study and the project is owned by the student. The student must submit a copy of the final shooting script, a detailed budget and a letter of intent itemizing the specific information endemic to the project. The student must also have a letter from the instructor at the school confirming that the student is enrolled at that educational institution and is undertaking the project as a course requirement. The project must not be more than thirty-five minutes in length and have a cost of no more than $35,000 with no more than twenty consecutive shooting days. SAG actors may waive compensation but agreements must be entered into as if they were getting paid for their services under the SAG agreement. This means that all time sheets must be kept as if the actors were receiving payment. Student projects must carry workmen’s compensation insurance. The project may be exhibited in the classroom for a grade, or as a visual resume to demonstrate before established members of the entertainment industry the merits of the student’s filmmaking capabilities. It may also be exhibited at student film festivals and for possible award consideration before the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. If the project earns ․1.00 in any form, or is exhibited in any public forum, then the student is required to pay all SAG actors for services performed on the project. The specifics of the Student Film Agreement may change from school to school. SAG has altered the agreement for schools based upon the structure of each schools’ curriculum.

The Screen Actors Guild agreements are renegotiated every three years at which time new areas of concern are discussed. It is best to check the current conditions of the SAG contract.

The Screen Actors Guild agreements are renegotiated every three years at which time new areas of concern are discussed. Terms of the new contract and these agreements are currently up for review and the terms of the new contracts are expected to be in place by June 2001.

The Screen Actors Guild agreement covers many areas affecting the working conditions of performers. It not only includes provisions for minimum wages, but it also deals with such issues as nudity, per diems, travel, meal periods, rest periods, retakes, added scenes, looping, wardrobe fittings, night premium, overtime, forced calls and so on. The contract is complex but the details of the contract are generally known and understood, not only by the production accountant, but also by the second assistant director. It is important for the producer and the director to be cognizant of some (if not all) of the basic aspects of the contract since it will affect the creative use of talent.

Each actor is entitled to an individual dressing room when working. In most cases they are small cubicles where they may rest. In other cases it may be a separate room or a motor home dedicated to the comfort for the actor.

Travel time to and from a distant location is considered work time for an actor. If the actor travels to a location (as opposed to reporting to the studio) and that travel begins on any day that the actor is not scheduled to work in front of the camera, the actor is compensated for a days pay with no overtime over eight hours. If the actor travels on a holiday such as Independence Day or Christmas, the actor is paid time and a half for the travel time. If the actor works and travels the same day and should overtime occur caused by travelling, then the actor receives time and a half for the overtime for that day. If the actor lives or works in any area in which there is a SAG branch and the actor is brought to the set or distant location in a different area of the United States for any purpose, the actor will receive not only the transportation to that area but an additional $75.00 a day from the time the actor begins travelling to the time the actor is put on salary.

The producer is not permitted to replace an actor’s voice without written permission of the actor or in certain other circumstances. Generally it is not necessary to replace the voice of an actor but on occasion, in order to make delivery of the project possible, it may be required. Under those circumstances working with SAG is especially recommended. During post-production on The Clonus Horror, one of the female actors refused to loop (replace) her voice, which had been recorded badly during production. I spent many hours with her on the phone trying to get her to agree to loop. She finally told me that she would come in only if we gave her the negative footage of the partially nude love scene she did with the main actor. She honestly believed that we were going to sell the footage to a pornography company and destroy her career. Of course this was ridiculous but she was insistent upon this as a condition of her looping. The investors and the production company owned the negative and we could not fulfill her demand. I was faced with a predicament. I called our representative at the Screen Actors Guild who warranted that her fears were unfounded since she was protected by our agreement with SAG against misuse of the nude scene footage. Knowing this, I asked the representative to speak with her. She did, and then notified me that all was fine and the actress would loop the scene. Thinking everything was resolved, I called the actress to schedule her time and she continued to find excuses why she couldn’t loop. It seemed that the excuses, whether true or not, were all connected with her work as a model for a magazine photo shoot. When she told me the name of the magazine, I called my representative at SAG and explained that the actress she spoke to would still not appear to loop because of her commitments as a model for a magazine photo layout. This did not faze the representative until I informed her that the actress had said that the magazine was Penthouse. Our SAG rep immediately ended our conversation with eight words; “You have SAG’s permission to use another voice!”

Performers must be notified in advance of the first audition if nudity or sex acts are expected in the role. When an actor signs in for the audition, be sure to indicate that nudity is required for the role on the sign-in sheet. That way you will have a signed acknowledgement that the actor is aware of the nudity. A performer has the right to have a person of their choice present at the audition. The producer should require the performer to sign a written consent as part of the contract when it concerns nude or sex scenes. It is a good idea for the producer to require the actor to authorize the doubling of the actor in these types of scenes if that is agreed upon by the actor. This will protect the producer should an actor who has consented to this type of scene subsequently withdraw that consent. The producer will then be able to double the actor and the scenes that have already shot may be used under the conditions granted in the original approval. Of course, if a double is used, doubles are not entitled to any residuals or screen credit. Finally, when nude scenes are done, the set must be a “closed” set to all people not having any connection or business with the project.

Voiceover–Dialogue or narration coming from off-screen, the source of which is not seen.

The director should know under what contract the actor is employed. The basic agreement provides for overtime to be paid for a daily player contracted for less than two times scale per day at 1½ times over eight hours up to ten hours and double time after ten hours. If the actor is contracted for more than two times scale a day, all overtime is paid at 1½ times over eight hours at the maximum daily rate of $225 an hour. If the performer is on a day player contract, overtime begins after eight work hours. If the actor is on a weekly player contract the overtime begins after ten workday hours on a forty-four (studio) or forty-eight (location) cumulative hour week. That is to say that weekly contracted actors who work past ten hours a day receive overtime for that day and if on a cumulative weekly basis they work over forty four hours (forty eight on location) they receive weekly overtime payments. Weekly contracted actors who are employed under the terms of special employment indicated in the SAG rules as Schedule C and F receive overtime payments only on a daily basis, as any weekly overtime is included as part of their weekly fee. This is in excess of ten hours on any day and is a double time rate. If the project is made for television, the overtime rates are somewhat different depending on the rate and terms of employment. Make sure you check the specific amounts with SAG.

This does not mean that the director must adhere to completing the actors’ work within the eight or ten hour day, but it does signify that the director must be aware of these conditions and should plan the use of the actor with these conditions in mind. Second assistant directors on the set are responsible for keeping track of the actual time each actor works. Although they should not bother the director with the conditions of employment for the actor, they should bring any overtime concerns to the first assistant director who in turn should gently nudge the director about being cost effective with the actor. The actual time the actor works is the time that is reflected on a sign out sheet, which is kept in the care of the second assistant director. The actor is normally permitted fifteen minutes to get out of makeup. Therefore, even though the director excuses an actor from the set, the additional fifteen minutes can put the actor into an overtime status. Some actors know that their time is based upon what is on the sign out sheet, so upon being excused by the director, they will purposely wander around, perhaps have a cup of coffee at the craft service table and chat with another actor just to delay signing their time out form so that they will get the extra overtime. This is especially true with actors who are working for minimum scale.

Rehearsal time is work time according to the SAG agreement. Rehearsal is a luxury on low or efficiency budget projects. Although the actor or director may want to rehearse, the budget may not allow for a rehearsal period. The producer should not worry or panic or think that rehearsal is absolutely necessary. The creative process for the performer, or the process that permits the performer to feel and experience the role usually happens when the performer is put in the actual location and wearing the appropriate wardrobe. This does not totally happen until they are on the set and working. There is a style of directing that will permit the director to get quality rehearsal time with the performers and not slow the production process during the actual day of shooting. An experienced and skilled director knows and utilizes this technique. Rehearsal that involves getting actors on their feet with the script in hand to stage a scene definitely counts as work towards shooting the project. This notion comes from the rehearsal process employed in theater. When this is done you will have to pay actors because this sort of rehearsal constitutes official work time. But a group of people getting together for dinner, during which they discuss the story, character and relationships is certainly not a rehearsal. It will not feel like a rehearsal to actors and therefore they will not have a notion of “needing” to get paid for that evening. Yet this will provide actors with the security that their egos need to fully grasp the work and relate to their fellow players. An informed gathering like this gives the director the opportunity to introduce the actors to one another and to view the interchange of creative ideas and thoughts; it also provides the producer the opportunity to nurture a creative environment for the “in front of camera” talent, without officially putting performers on the payroll.

SAG requires that their performers sit and eat a meal within six hours of their reporting to work. The meal period is deducted from the performers work time and must be no less than thirty minutes and no more than one hour in duration. Each additional mealtime is to be within six hours of the preceding meal. But if the six-hour period ends while the camera is in the actual course of photography, the shot may be completed without a penalty being levied to the producer. For the first half hour or fraction of violation of the meal period, the performer will receive $25.00; for the second half hour or fraction of violation the performer will receive $35.00; and for the third half hour and each additional half hour thereafter or fraction of violation the performer will receive $50.00. So if the performer sits down to eat a meal 7½ hours after they have started work, they are to receive $110.00 (non-taxable) from the producer. Meal penalties occur more times than they should, primarily due to poor planning on the part of the director.

If a producer asks a day player to go to a wardrobe fitting any day prior to the day the actor works, the day player is entitled to be paid for the amount of time they are required for the fitting, unless the day player is receiving more than $950 a day for their performing services. However, a producer may require a weekly player to go to a wardrobe fitting without additional compensation as the producer is entitled to four free hours of fitting time on two separate days for each week the performer works on the project. Any more than four hours or additional days requires the producer to pay the performer for their time.

The producer must schedule performers so they are able to have twelve hours between the time they are dismissed from any days’ work to the time they are called in to work the next day. The twelve hours may sometimes be reduced to ten hours (only once in three days), only if the next day’s schedule is a location other than an overnight location and exterior scenes are required on the day before and the day after the rest period. On theatrical projects with overnight locations, the producer may give a performer eleven hours of rest on any two non-consecutive days. A performer must also be given thirty six consecutive hours of rest within the workweek. This usually reflects the amount of time that is taken during a six day shooting week, which is customary on overnight locations. If the workweek is a studio workweek, then the rest period the producer must provide for a performer is fifty-six consecutive hours. The penalty for any of these violations, known as a forced call, is one day’s salary. This penalty may not be waived under any conditions without the specific consent of the Screen Actors Guild. Forced calls are common when the director has not planned out the shooting day, or does not know how to work creatively with performers in relationship to production schedules. Directors who are not skilled with directing techniques to avoid forced calls are usually first-time directors whose experience has been on low budget films where fourteen to sixteen hour production days are the norm. Will Gotay, one of the stars of the film Stand and Deliver, was employed under a SAG agreement for a series of commercials to be shot in Mexico. Eight of the nine days he was working were forced call days. He came home with enough money to purchase a new automobile outright while the producer had to go back to the advertising agency and try to explain why the lead actor’s salary went triple over the projected budget.

The production board comes in handy when estimating the probability of forced calls. This will depend on the complexity of the production elements on any specific day and on the director’s preparation. The production board will also provide information about other actor scheduling problems. From the production board the producer is able to establish a day out of days.

The day out of days in Figure #14, taken from the production board tells the producer many things; “sw” indicates start work, “w” indicates workday, “fw” indicates finished work, while “h” indicates that the performer is on hold for that day. A hold day is a standby day in case the director needs to call the performer in to work because of new scenes, rescheduling of scenes, or scenes that were not completed from another day. A wise producer will also use the hold day to schedule actors for looping or rerecording badly recorded dialogue for scenes that have already been shot. This may avoid additional payments to the actor for looping during post-production. The day out days in Figure #14 tells us that the character Eyan Hayes will need to be hired on a weekly contract with one-week guarantee. Although the character works seven days, four of them are in the first week and three of them in the second. Without including the words “one week guarantee” in the contract, we would not be able to pay the performer for 4/5ths of a week for the second week of work. The performer would have to be paid for the entire week, since he would be employed as a weekly performer without a mention of a guarantee. The same holds true for the performer playing Trish Malone even though her week begins a different day than the actor playing Eyan’s. It should be noted that both characters have the appropriate two days off and the producer and director have to make sure that they have fifty six hours of time off from the time they are released on the last day of their work week to the time they start their second work week. If they do not, the first day back becomes a forced call.

Figure 14

The character Angela will have to be hired on a weekly as well. But with her there is a fiscal question. She is scheduled to work the sixth day of a five-day week with only one-day off before working again. Unless the project is being done under one of the other SAG agreements (other than the Basic Agreement), the sixth day will be a double time day and the seventh day of work will be a forced call day. If this is the case, the producer will have to re-schedule this character by reboarding if possible, or plan for the extra funds needed to pay the actress playing this character. The characters Tommy Joe, Delphine, John, Annette, Bob and Don are all day players who are scheduled to start and finish work on the same day. The key issue in their cases is the eight hours of work before they reach an overtime status. Remember, overtime for a day player contracted for less than two times the scale wage is at 1½ times over eight hours up to ten hours and double time after ten hours. If the actor is paid more than two times the scale wage for the day, overtime is paid at 1½ times at $225 an hour.

Finally, the day out of days indicates that Eyan’s stunt double is working on a day that Eyan is not scheduled. Although this seems strange, it really is not. It means that the stunt that Eyan does in the project will be done by the stunt double on the last day of the workweek and the performer playing Eyan is not needed. In this case, the director has made a definite creative decision not to see the actual performer playing Eyan when the stunt is being done. In Hunter’s Blood, the shooting schedule was based on a six-day week for the crew, but a five-day week for the actors. We were able to board the project so that Sam Bottoms was the only actor to work on the sixth day in two successive weeks, and we planned to pay him for that sixth day pursuant to the SAG agreement as an overtime day. We just had to make sure that he had the appropriate turnaround time before beginning his next week of work.

As the schedule changes for whatever reasons, the day out of days will change and will inform the producer and director of other creative and fiscal issues that might become problems. In reality, this puzzle changes constantly and a smart producer will stay on top of this major issue since it has such a huge creative impact upon the project. This will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 11. A word to the wise: “What goes on behind the camera during the process of production can be learned from a book, but what goes on in front of the camera, or the story, can take a lifetime to learn.”