7

Cyclic Compaction Under Alternate Shear Motion

7.1. Background and framework of the analysis

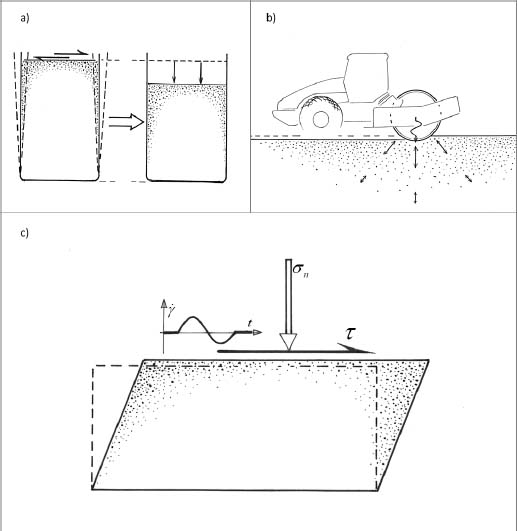

The basic phenomenon of granular materials compaction under alternate shear motion is commonly experienced in daily life with everyday granular materials of all kinds, e.g. in filling to maximum a jar with raw sugar, coarse salt, dry rice, etc. (Figure 7.1). In geomaterials, this well-known phenomenon has been documented by specific experimentations for a long time (see [SIL 71, YOU 72, TAT 74, MOD 11]). It is widely used in civil works for improving the consistency of granular fills used as infrastructure platforms such as highways and rail track platforms, rockfill dams, etc., with the means of static or vibratory roller compactors.

This same phenomenon is also responsible for liquefaction effects in saturated granular materials subject to earthquakes or other dynamic cyclic solicitations, where the cyclic compaction induces an increase in the pore pressure until the effective stresses are no longer able to withstand the exerted shear stresses (see [MAR 75, ISH 93]).

In this chapter, a simplified model of this phenomenon is proposed through the macroscopic dissipation equation under quasi-static conditions. The aim of this simple model is not to propose a detailed description of the whole complexity of cyclic behavior, but to display the significant basic features already “built inside” the present dissipative approach, especially as significant features of large amplitude cyclic motions of all kinds appear already quite well represented (Chapter 6). The analysis is performed for the simplest mechanical scheme of stresses and strains exerted in this process: the situation of simple shear under plane strain conditions (see Figure 7.1) with some rotation of principal axis, as found in the simple shear apparatus.

Figure 7.1. Alternate shear motion. (a) Common experience. (b) Usual compaction practice in civil works. (c) Simple shear schematic representation

In this framework, basic features of the dissipation relation may be investigated, regarding the effect of quasi-static strain-driven alternate shear motion cycles, small enough to maintain stress variations negligible relative to their average values.

The main results are:

- – For such strain-driven small cycles, the cumulated volume changes are always in contraction, or compaction.

- – The relative intensity of this volume contraction or compaction decreases with the principal stress ratio, as displayed by the curve of cyclic compaction ratio to principal stress ratio.

- – If the cycles are repeated, a typical ratcheting effect appears.

- – The best efficiency of compaction in this process retains the core of the “characteristic state” near the isotropic stress states line, and regarding energy efficiency (the energy required for a given volumetric compaction) for low mean stresses.

- – Regarding compaction procedures in embankments, these results mean that best compaction results are to be expected with thin horizontal layers, with an unavoidable decrease in efficiency near the embankment slopes.

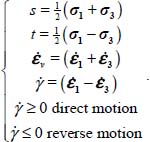

In this present investigation, we will use specific notations that were implemented long ago for plane strain situations (adapted from [ODA 75, HUG 77])

The considered alternate shear motions consist of two phases, one in plane strain Mode Direct motion (strain rate signature (+,0,−) or  as mentioned in section 6.2) and one in plane strain Mode Reverse motion (strain rate signature (−,0,+) or

as mentioned in section 6.2) and one in plane strain Mode Reverse motion (strain rate signature (−,0,+) or  ), which can be analyzed separately through the dissipation equation (see section 6.2 and corresponding Appendix A.6.3), and the set of the two phases represents the whole back-and-forth movement of the cycle.

), which can be analyzed separately through the dissipation equation (see section 6.2 and corresponding Appendix A.6.3), and the set of the two phases represents the whole back-and-forth movement of the cycle.

The features foreseen by the dissipation relation in this framework are treated in Appendix A.7.

7.2. Key results

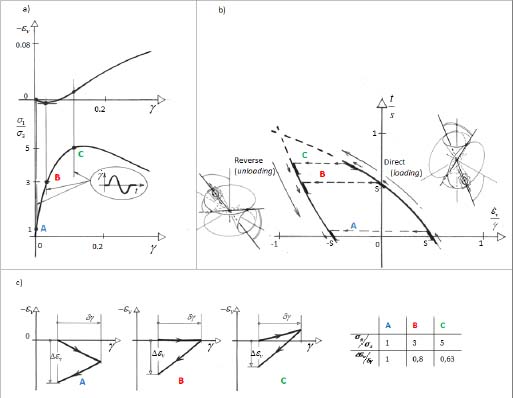

The results are first detailed for the following three kinds of cycles, concerning:

- – a neighborhood of isotropic stress state, principal stress ratio about σ1/σ3 = 1;

- – a neighborhood of “characteristic state”, principal stress ratio about σ1/σ3 = 3;

- – a situation with pronounced dilatancy in direct motion (dilatancy rate about 1.67), and principal stress ratio about σ1/σ3 = 5.

The locations of these three typical cycles along a would-be monotonic stress–strain curve, and within the specific stress–dilatancy diagrams for this kind of simple shear situation, are shown in Figure 7.2(a) and (b), and the results for the respective volume changes are shown in Figure 7.2(c).

Figure 7.2. Small alternate shear motions analyzed. (a) Position on monotonic stress–strain curves. (b) Position on specific dilatancy diagram, with micro-scale polarization patterns. (c) Resulting volume changes versus shear strains. For a color version of the figure, please see www.iste.co.uk/frossard/geomaterials.zip

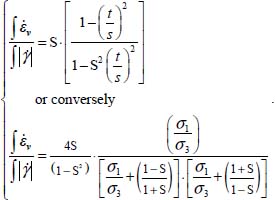

Even if dilatancy appears in the direct motion phase of the cycle (as in cycle C), the reverse phase is always in contraction, the intensity of which increases with the value of the principal stress ratio, according to the effect previously outlined in section 5.8. The ratio of cumulated volume change to cumulated shear cycle amplitude, or the cyclic compaction ratio, is always a contraction given by the following relations:

7.3. The cyclic compaction ratio versus the principal stress ratio

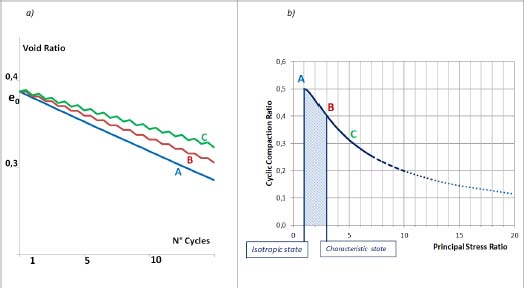

Considering now the repeated cycles, the cumulated change in the void ratio may be computed from the detailed relations of Appendix A.7. Results are displayed in Figure 7.3(a) with the typical ratchet effect resulting from the irreversibility of the motion.

The global efficiency of this cyclic compaction may also be appreciated by tracing the cyclic compaction ratio defined above versus the principal stress ratio, as shown in Figure 7.3(b). The best efficiency appears clearly in the figure within the limits of “characteristic state”, with a maximum near stress isotropy. In the cycles performed under significant shear stresses, as type C cycles, the loss of compaction efficiency is quite significant relative to cycles performed under isotropic stresses (type A); about 40% reduction in this global efficiency for type C cycles relative to type A.

This result also denotes that while compacting embankments by horizontal layers is a common practice in civil works, a significant decrease in compaction efficiency is expected near the slopes of the embankments, where more shear stresses are likely to develop through the simple effect of gravity (hence locally increasing the principal stress ratio).

Figure 7.3. Effect of repeated cycles of small alternate simple shear motion. (a) Void ratio evolution displaying the typical ratchet effect. (b) Cyclic compaction ratio versus principal stress ratio. For a color version of the figure, please see www.iste.co.uk/frossard/geomaterials.zip

7.4. Energy efficiency of compaction

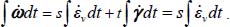

The energy efficiency of compaction can also be analyzed by comparing for one complete cycle (direct shear motion + reverse shear motion) the cumulated volume reduction achieved to the cumulated energy dissipated in the cycle.

Note that the work rate of internal forces is written as

Therefore, for each motion of the cycle (direct shear motion and reverse shear motion)

- – Direct shear motion (δγ): δω = sδεv + tδγ.

- – Reverse shear motion (δ'γ = –δγ): δ'ω = sδ'εv + tδ'γ.

Total cycle

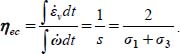

As this total work of internal forces is fully dissipated here, the energy efficiency of volumetric compaction is simply obtained as

Thus, in this simplified approach, the best energy efficiency of this strain-driven cyclic compaction is obtained for the lowest mean stress (σ1 + σ3 as low as possible), i.e. for compaction procedures by thin horizontal layers.

These results point also that, for a given thickness of material to be placed and compacted, it should be more efficient to divide it into various thin layers to be worked successively than to try placing and compacting it once with a very thick layer. This corresponds to normal procedures in civil works, consistent with the practical data displayed in Figure 10.9 in Chapter 10.

7.5. Limit of cyclic compaction when apparent inter-granular friction vanishes

It may be observed that when apparent inter-granular friction vanishes (i.e. the value of  tends to 0), the cyclic compaction ratio encountered in equation [7.2] vanishes; the material tends to become incompressible.

tends to 0), the cyclic compaction ratio encountered in equation [7.2] vanishes; the material tends to become incompressible.

This result is consistent with the fact that when this inter-granular friction vanishes, the features of granular materials mechanics provided by the present approach tend toward the mechanics of a “perfect incompressible fluid” (Chapter 5, section 5.9).