Maps and Listings

The past three decades’ stupendous growth in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) – with the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) of Shenzhen at the forefront – has been a key part of China’s recent transformation. Occupying around 40,000 sq km (15,500 sq miles), the delta was once totally consumed by manufacturing, contributing around 30 percent of China’s total exports. These numbers are now on the decline as factories relocate inland and to other parts of Southeast Asia. There are upsides in terms of pollution – while sometimes bad, the air tends to be better here than in Beijing or Shanghai – and the wealth generated during the boom years has made the region among the most modern and developed parts of China.

Pedaloes in Lizhi Park, overlooked by the enormous Kingkey 100 Finance Building.

AWL Images

The Delta’s transfiguration from paddy fields to stocks and shares deals, described by The Economist magazine as “so huge as to transform global trading patterns and investment flows”, began in earnest in 1992. The then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping toured China’s southern provinces, passing on the message that to get rich was glorious. SEZs with looser regulations and taxation started up in Shenzhen and Zhuhai shortly after. Investors from Taiwan and Hong Kong hurtled in, putting their international marketing savvy to prime use, to be swiftly imitated by their mainland counterparts.

The always bustling Donmeng Pedestrian Street.

iStock

The PRD still produces a large proportion of the world’s electronics, motor parts, shoes, toys, furniture, textiles, clocks, watches, lighting and ceramics. There are around 200,000 factories here, approximately half of which are owned by Hong Kong companies whose workers largely originate from the less industrialised inland areas of China. These migrant workers typically live in dormitories on site at factories, and send money back to their families at home.

Dongmen Pedestrian Street celebrates Chinese New Year.

Dreamstime

Shenzhen and environs

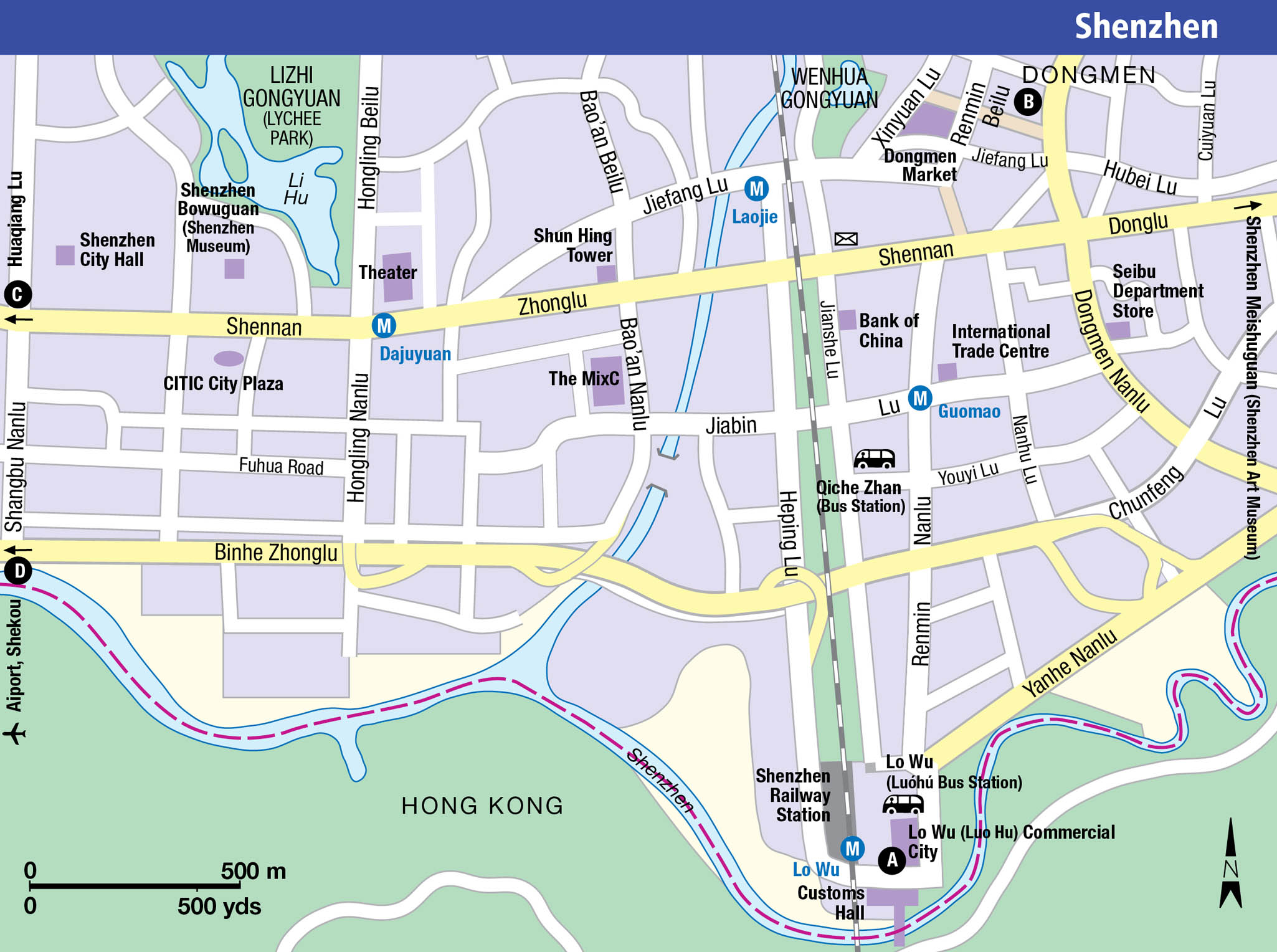

Shenzhen 1 [map], slap bang next to the Hong Kong border, was always going to do well. This is the new face of the PRC, where capitalism has been given pretty much a free hand after decades of communism. Nowadays its Mission Hills Golf Club, which embraces a dozen 18-hole championship courses (designed with help from the likes of Jack Nicklaus, Nick Faldo and Vijay Singh) stands in the Guinness World Records as the world’s largest. Shun Hing Square, some 384 metres (1,260ft) tall, is the 21st-highest building in the world. Yet in the late 1970s, there was little here except for a farming community and a dingy border town.

The rise and rise of Shenzhen

The creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) during the 1980s, with their modern and relaxed business and tax regulations, kick-started the transformation of the Pearl River Delta, and nowhere was this more pronounced than in Shenzhen. Pell-mell, the factories and skyscrapers grew almost overnight, immigrants from all over China poured into the burgeoning city to make their fortunes, highways were rolled out, airports and railways constructed, and arable land smothered in concrete. The few hundred peasants who once eked out a living here dispersed in a phenomenon that was to become a byword for fast living, cheap shopping and a no-holds-barred race to the future.

Three decades later and Shenzhen is the second-richest city in China. Per capita income is around eight times the national average, and the population has risen from 700,000 to 11 million in 25 years. Between 1992 and 2011, the city’s GDP increased more than thirty-fold, from Rmb 32 billion to 1.1 trillion. Of course, the relentless growth has its downside. As inequality rises, so does crime: you are around nine times as likely to be mugged in Shenzhen as in Shanghai, and the air pollution can be choking.

Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport lies to the west of the city and has good ferry and coach links to Hong Kong. There has been talk of one day creating a “mega-metropolis” comprising Hong Kong and Shenzhen, but for now there are six land borders between the two; most visitors from Hong Kong take the MTR to either Lo Wu, the busiest border crossing point, or Lok Ma Chau, and walk across to enter mainland China. Both crossings link directly into the Shenzhen metro network.

Replica of the Eiffel Tower in the Window of the World Park.

Dreamstime

Shenzhen offers a (rather unrepresentative) glimpse of the People’s Republic to Westerners visiting Hong Kong, while Hong Kongers themselves visit in search of cheaper dining, nightlife and recreation, not to mention the shopping bargains at the emporia where the goods are “inspired by” major fashion companies like Prada and Chanel.

What to do in Shenzhen

One of the most extensive retail romper rooms is the exhausting Lo Wu Commercial City A [map] (Luo Hu in pinyin), on the right after you exit the customs hall. Jewellery, clothes, leather goods, knick-knacks and a cornucopia of other merchandise are packed one atop the other here – although shops selling the same sort of items tend to cluster together. The cardinal rule is to bargain fiercely. Offer less than a third of the asking price and settle for no more than half. Stallholders will calculate the price in Renminbi or HK dollars, but you will get a better deal if you use the former.

Shenzhen’s other main shopping areas are Dongmen B [map], with a wide range of shops and some good tailors, and at Huaqiang Lu C [map], where electronics goods stores can be found. There is little difference in price compared to Hong Kong as far as mainstream electronics brands are concerned: the bargains lie in goods manufactured for the domestic market, although the price is a fair indication of the quality and life expectancy of any item. (For more details on Shenzhen shopping, for more information, click here.)

Even half a day’s shopping in Shenzhen is likely to take it out of you, so take time out to enjoy some inexpensive grooming. Lo Wu Commercial Centre has dozens of low-key nail bars and well priced – if a tad spartan – massage parlours and beauty salons.

People hang wishes on the tree for good luck in the Foshan Ancestral Temple.

Dreamstime

If Shenzhen has a Wild-West vibe during the daytime, wait until the evenings. International hotels are a safe bet unless you are partying with locals. The main bar areas are International Bar Street in Futian and Shekou D [map], a more expat-friendly residential area.

Chinese New Year Parade in the Folk Culture Village, Shenzhen.

Dreamstime

The theme parks

It’s tempting to regard Shenzhen as one enormous wacky theme park, and there’s certainly no shortage of the real thing. The three main parks are clustered together in the Nanshan District, about 12km (8 miles) west of the downtown area. There are combination tickets available if you wish to see more than one park. Window of the World 2 [map] (daily 9am–10.30pm; charge) showcases facsimiles of everything from Thai palaces and Japanese teahouses to European monuments – none more spectacular than the impressively large scale model of the Eiffel Tower.

In a rather similar vein, Splendid China 3 [map] (daily 9am–9.30pm; charge) packs the whole country into one park, while the China Folk Culture Village 4 [map] (daily 9am–9.30pm; charge) presents 56 different ethnic perspectives. Meanwhile, Minsk World 5 [map] (daily 9am–7.30pm; charge), on the other side of Shenzhen, offers themed fun inside a 40,000-tonne former Soviet aircraft carrier.

The Shenzhen Museum, on Fuzhong San Lu in Futian District (Tue–Sun 10am–6pm; free), is home to more than 20,000 cultural relics, with permanent exhibitions on the history of the Pearl River Delta. Exhibitions on folk history include Hakka culture and Hakka roundhouses.

Transport to/from Shenzhen

Hong Kong–Shenzhen

Trains: Every 6–8 minutes from Kowloon to the border terminus of Lo Wu (5.30am–11.07pm) or, slightly less frequently, to Lok Ma Chau (5.35am–9.35pm). Journey takes around 45 minutes. Shenzhen station is located just over the border.

Ferries: 20+ daily ferries between Hong Kong/ Kowloon and Shekou port (50 mins); 11–13 daily between Hong Kong Airport and Shekou (30 mins); 5–8 daily between Hong Kong Airport and the Fuyong Ferry Terminal (Shenzhen Airport; 45 mins).

Buses: Frequent shuttle buses (typically every 30 mins) run from several locations around Hong Kong, including Central, Tsim Sha Tsui and the airport, to downtown Shenzhen, Shekou and Shenzhen Airport.

Shenzhen–Macau

Ferries: 3 daily to/from Shekou port (80 mins). Also hourly Shekou–Zhuhai (1 hr).

Shenzhen–Guangzhou

Trains: 3–5 express per hour (55–70 mins), plus slower trains (1.5 hrs).

Buses: frequent departures (1.5 –2 hrs).

Shenzhen’s metro system opened in 2004 and has since developed at warp-speed. There are currently five lines: the “green” Luobao line is probably the most important, running from Lo Wu , through the central Dongmen area, out past the theme parks, through the rapidly-developing Nanshan district and on to the airport; the “red“ Longhua line runs north–south from the Futian border crossing (beside Lok Ma Chau) to Qinghu; the “blue” Longgang line also begins in Futian and ventures northeast past the Universiade park; the “purple” Huanzhong line does a northerly loop around the city; while the “yellow” Shekou line runs east–west all the way out to the Shekou port and peninsular. Trains run every 6–8 minutes 6.30am–11pm.

Around the Delta

Away from Shenzhen, much of the Pearl River Delta is a mix of sprawling industrial parks, odd swathes of farmland and occasional golf courses interspersed with a few less developed hilly areas. The areas to the west of the river delta itself are, on the whole, more attractive than those to the east.

Passengers aboard the train at Shenzhen Railway Station.

Dreamstime

Humen and the Opium Pits

While international trade is now all the rage in the Delta, early attempts by Western traders to introduce opium to China in the 19th century met with stiff official resistance, commemorated at both a park and a museum in the town of Humen, right on the river delta, around 25km (15 miles) northwest of Shenzhen Airport. It was at Humen that Commissioner Lin Zexu (for more information, click here) contaminated several thousand chests of opium with quicklime in 1839, then deposited the haul in the so-called opium pits on the shore to the south of town. The British retaliated, sparking the First Opium War, and Lin was exiled. In the Opium War Museum (Yapan Zhanzheng Bowuguan; daily 8.30am–5pm; charge) in Zhixin Park, much is made (and rightly so) of the perfidiousness of foreign merchants who started the conflict that ended with the Chinese forces vanquished and the ceding of Hong Kong in 1841. On the coast some 5km (3 miles) south of Humen town, the original opium pits and the fortress of (Shajiao Potai) are worth a visit (8am–5pm; charge).

Foshan and Shiwan

The busy city of Foshan 6 [map] lies southwest of Guangzhou. It’s a dusty centre of ceramics and textile production, but hidden away from the grids of factories is the 1,000-year old Zu Miao Temple complex (21 Zumiao Lu; daily 8.30am–7.30pm) The temple is well preserved, with many finely sculptured friezes made from limestone, ash of shells, paper, rice, straw and sand. The once colourfully painted friezes depict fables and scenes of Foshan’s history. Many of the friezes have faded to an antique tone, which adds to the temple’s charm.

Shiwan 7 [map], just 2km (1.25 miles) southwest of downtown Foshan, has been making ceramics for centuries, and is home to many porcelain factories that these days welcome tour groups. The fires at the Nanfeng Ancient Kiln (daily 8am–6pm; charge) are said to have been alight and firing pottery since the Ming era. The four-day firing process is explained by way of a series of English-language signs.

In the Nanhai district of Foshan, Xiqiao Shan 8 [map] is a hilly area with villages that have retained some of their 19th-century flavour. Xiqiao is one of the more peaceful areas in Guangdong, one that still thrives on its local produce and river trade. From the town, it’s possible to travel by cable car to visit the statue of Guanyin on the crest of the nearby hill and walk along stone paths that wind through even smaller villages, rocky plateaux and waterfalls, including Feiliutian Chi, which is reckoned to be the most picturesque.

South to Macau

Shunde 9 [map], on the road from Guangzhou to Zhuhai, is renowned for its Qing garden, and has some photogenic back lanes and canals. Further south, the large town of Jiangmen ) [map] is eminently missable, although the Ming-era villages in the surrounding countryside – centred round a watchtower – are a pleasant reminder of architectural whim in former days. Closer to Zhuhai, and on the coast, the memorial garden at Cuiheng ! [map] pays tribute to its best-known son, Dr Sun Yat-sen, China’s first republican president. Zhuhai @ [map] is the last major city before Macau, and is steadily growing in importance as a Special Economic Zone.