Because an Armistice was on it did not mean that work ceased for members of the motor units. As a matter of fact, the numbers of duties to be attended to seemed to increase rather than otherwise.

Car crews had to be out on outpost duties the same as usual and relieved one another for day and night shifts as the front lines were kept intact and no armed bodies were allowed to approach. Numerous trips were undertaken to quell disturbances caused chiefly by bodies of unfriendly Arabs and tribesmen in the various villages and towns in the vicinity.

In fact, we came to the conclusion that the whole population of Asia Minor and Syria were more or less cutthroats and robbers. The tribe that was strongest generally murdered and robbed the weaker ones.

52. No. 1 Australian Light Car Patrol at Aleppo Railway Station in November 1918. From left to right: two Model T Ford ‘fighting’ cars armed with Lewis machine-guns, a Ford tender, German Loreley, another Ford Tender, two ‘fighting’ cars and two motorcycles. Clearly some effort has been made to reassemble the cars at the end of the war (AWM B00707).

The Light Car Patrols owing to their mobility were gradually taking over the job of policing the occupied territory and had to take numberless excursions by night and day in all directions on both real and false alarms. One of the first undertakings of the British at Aleppo was to get the railway intact and trains running through to Damascus again. Several of the bridges had been blown up and most of the locomotives had been damaged before the Turks left the town.

A small shunting engine had been overlooked and this came in very useful for moving construction material. Several German motor lorries with flanged wheels to use as rail motors were also discovered and, in a very few days, Major Alexander, the Commander Royal Engineers, had the line clear for the first train from Damascus and a daily service was soon in vogue.

Several miles north of Aleppo was Muslemeye which was a very important point on the railway line as the junction of the two lines from Constantinople and Bagdad took place there. At this junction was stationed a large German Mechanical Transport Depot with stores and workshops. In the yards we were surprised to see quite a number of the German army lorries, which we had put out of action several months previously on the Amman and Es Salt Road. They were in for reconstruction, but practically nothing had been done to them and they were in the same state as we had left them on the road, some with their water jackets smashed and others with gear boxes blown in. We could imagine the tremendous amount of work the enemy had put in in getting these vehicles back over the road and then on to the rail again, only to be abandoned once more several miles north.

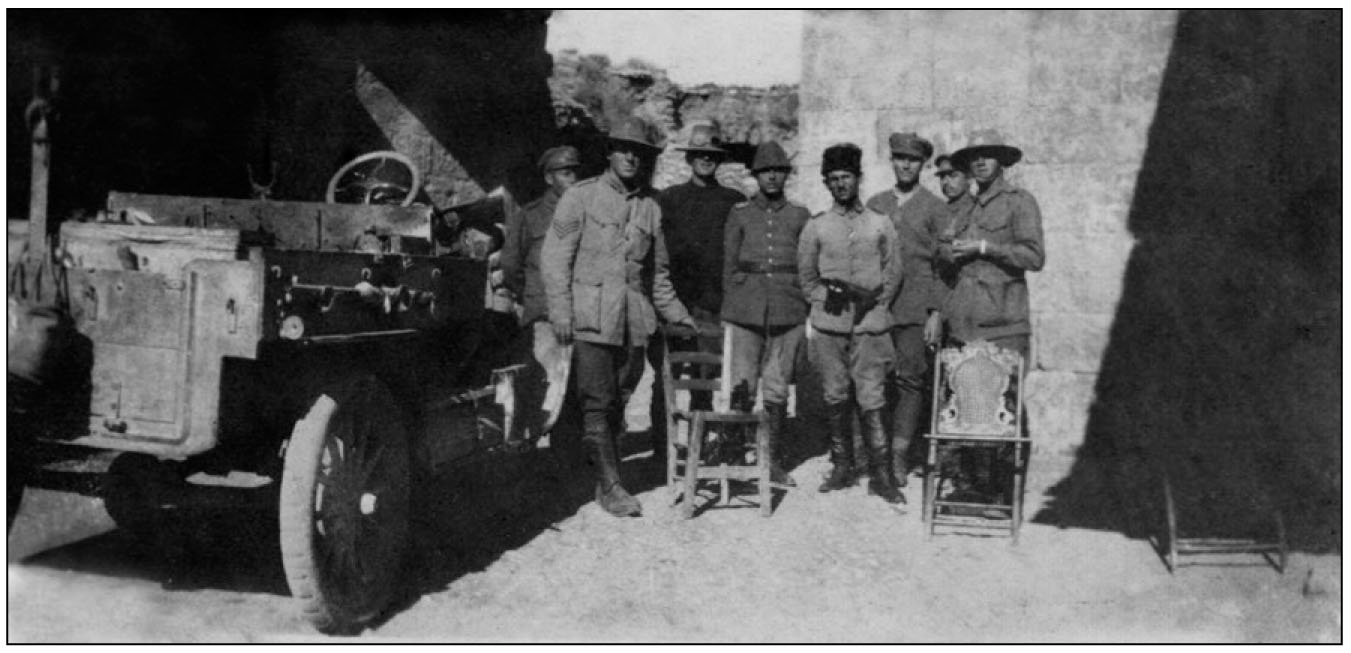

53. Sergeant Bert Creek and Driver Hal Harkin with Turkish prisoners, 150 miles from Alexandretta (Cohn collection ATM LCP.HC 016).

On the 24th November, we had an interesting trip into the enemy country under arrangements made between the British, French and Turkish authorities.

Our instructions were to make a road reconnaissance up to the town of Erzin which is west of the Taurus Mountains in Asia Minor as it was proposed to send ambulances to this point to pick up sick and wounded prisoners in Turkish hands and bring them back to our own hospitals before the weather became too wet for travelling. We accordingly took a couple of our own cars and borrowed one of the Rolls’ tenders from the 11th Light Armoured Motor Battery Squadron and drove westward over the Hills of Bailin to the Mediterranean at Alexandretta (about 100 miles) where we stayed for the night in a liquorice factory on the sea coast.

In the morning we picked up the English Base Commandant and the French Military Governor (as Alexandretta was in the French sphere).

We made an early start and drove north under a white flag until we came to the Turkish line of trenches where we were halted. The Turkish Authorities had been advised and had raised no obstacles to the expedition. After a short delay we crossed the trenches, picked up a Turkish Officer as a guide and drove along the coast for a while then proceeded inland passing numbers of Turkish and Armenian villages (most of the latter being deserted and looted). There were very few travellers on the roads and the few that we passed ignored us probably thinking we were German. We arrived in time to have a late lunch at Erzin and after interviews between the British and Turkish local authorities who all seemed to talk in French we drove back to Alexandretta arriving at the French lines before dark. We found the tracks rough but quite negotiable for motor ambulances provided the weather was dry but quite hopeless after any heavy rain and we made our report accordingly. Next morning we left Alexandretta and got back to Aleppo in the afternoon.

On the 4th December, we had another interesting trip and under orders from the General Officer Commanding we proceeded to Katna, a railway town, to take over from the Turks a train load of guns and machine-guns from the Turkish southern line. These were to be handed over to us under the terms of the Armistice. We arrived at Katna in the morning expecting the train to be in about midday and waited all day in the teeming rain without any sign of it. Late in the afternoon a message was received that the train was delayed owing to the lack of fuel, and the firewood gathered along the route was wet and unsuitable. We camped on the railway platform for the night and next morning the train slowly steamed in.

Headquarters 5th Cavalry Division.

3rd December 1918

PRESSING.

TO No. 11 L.A.M. Battery.

No. 1 L.C. Patrol.

13th Cavalry Brigade.

15th Cavalry Brigade.

Divl. Train.

‘Q.’

1. The 11th L.A.M. Battery and the No.1 L.C. Patrol under an Officer not below the rank of Major to be detailed by the 13th Cavalry Brigade, will proceed to MASHALE station to-morrow December 4th to receive the surrender of the guns Light and Heavy, machine guns and ammunition of Turkish Forces, South of the line KILLIS-ISLAHIE.

2. The guns will be handed over at MASHALE station at 1200. The number to be surrendered is not known, but the officer in charge will give a detailed receipt for all guns, machine guns and ammunition taken over.

3. The machine guns and ammunition will be brought back to ALEPPO by the lorries detailed in QX/916 of 2nd, which will move to MASHALE station for this purpose after depositing their loads at KATNA.

4. The surrendered guns will be towed to ALEPPO by these lorries, and rope and tackle for this purpose will be taken out by the lorries.

5. In the event of the lorries being unable to bring in all the surrendered guns and ammunition, they will be dumped at MASHALE under guard of No. 1 L.C. Patrol and the fact reported by wireless from KATNA to Divisional H.Qrs.

6. Rations for 3 days are to be taken by No.1 L.C. Patrol.

7. Name of the Officer detailed by 13th Cavalry Brigade to be wired to Divl. H.Quarters.

8. The 13th Cavalry Brigade will detail an Officer to proceed with this party to reconnoitre and report on suitable site for a camp at or near KATNA for one cavalry regiment.

9. Acknowledge.

Lieut-Colonel

General Staff

5th Cavalry Division.

H.Qtrs 5th Cav. Div.

3rd December 19184

We went through the inventory of the guns and stores on board and found these correct. The Turkish Officer in Charge seemed to be quite pleased to hand over his charge. He said he was finished with military duties and was going back to his farm. He had had quite enough of war and handed to the writer his dagger as a souvenir. We placed a guard in the train which was the first one through from the Turkish direction since the Armistice and after about an hour’s wait to get up a sufficient head of steam the train slowly proceeded on to Aleppo.

We drove there by road and arrived a couple of hours ahead of the train. Two days later we received orders at midnight to turn out and kill or capture a party of bandits who were attacking our telegraph linesmen along the road about 60 miles west. The night was black, cold, wet and miserable but after about five minutes grumbling the unit was going full speed, splashing through sheets of water and mud and all soaked through to the skin, only to arrive at our destination (with the first streaks of dawn) to find that the bandits had bolted to the mountains hours before, probably long before we started. However, this was only what we expected, so we picked up the linesmen and returned to our camp near Aleppo.

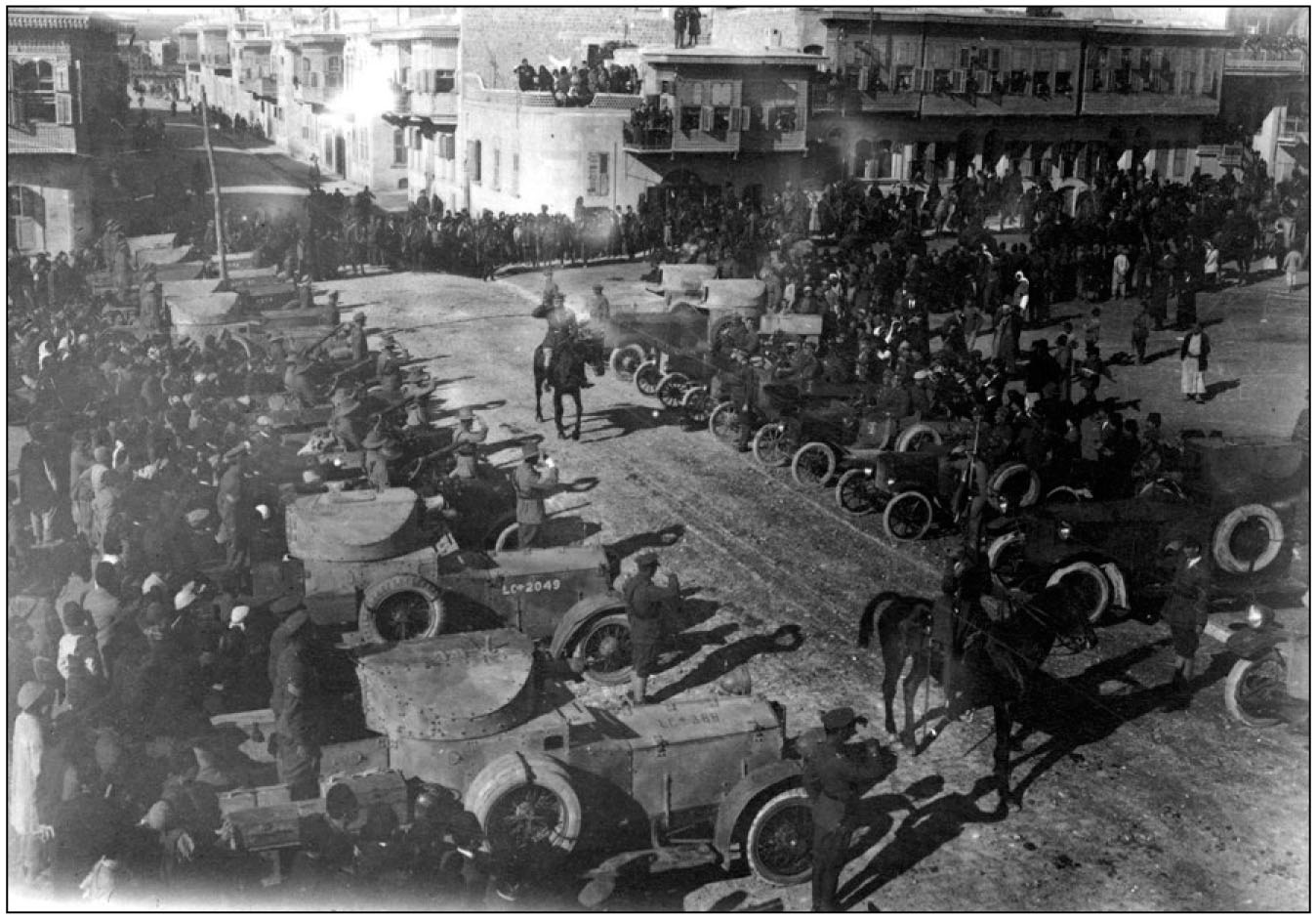

54. General Allenby, mounted, taking a salute from paraded drivers and crew of armoured cars from the 2nd, 11th and 12th Light Armoured Motor Batteries, Machine Gun Corps, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section and the Scottish 7th Light Car Patrol (AWM P11419.007).

On the 11th we had a different sort of turnout. All cars and guns were cleaned up and polished and everyone had his best uniform on for the occasion as this was the day of the Grand Procession through the city on the official entry of General Allenby (the Commander in Chief). The inhabitants had to be impressed properly and the mounted forces with the various motor units in full strength made a good display as they paraded through the principal streets.

Two days later, we had another excursion after bandits in the direction of El Hamman. This time we managed to capture one of them. We brought him in and handed him over to the authorities to deal with.

The weather at this time of the year being the wet season was very cold and miserable and the members of the patrol were feeling it very severely after their long sojourn in the extreme heat of the Jordan Valley. Many of them who managed to survive the malaria while in the hot and unhealthy parts were now succumbing to it although in a district where malaria was not prevalent, and one after another the men were being drafted off to hospital. Fortunately, we were able to get sufficient reinforcements to carry on with.

On the 28th December, the unit drew petrol and supplies for ten days and received orders to move north about 100 miles to the Turkish town of Ain Tab which was to be the centre of our operations until further orders. Ain Tab is at the foot of the mountains and is a very cold place in the winter and as it happened to be nearly midwinter we arrived there at the coldest time of the year. We drove into the town at 4 p.m. and were met by Major Mills, the British representative there. We were allotted quarters in an American school which was empty and were glad to get under a roof once more. We soon had some firewood brought up and a cheerful fire burning. Next morning when we woke up a snowstorm was in full progress and the ground was under a mantle of white. Motoring was more or less out of the question and we hoped that no orders for any more moves would be received for some time. New Year’s Day broke out fine and we took the opportunity of sending back to Aleppo to bring up further supplies of petrol. The following night the car returned to Ain Tab with supplies after a very rough trip; the driver reported that the rains had washed innumerable stones on to the roads and he had had no fewer than fourteen punctures on the trip back. We found out afterwards that the stones were not wholly responsible for our tyre trouble as the tyres themselves were somewhat to blame. The Motor Transport stores had received a consignment of tyres of American manufacture which had been sent from Egypt and these we discovered were far from being up to the standard of the quality of the usual tyres of British manufacture which we had received previously.

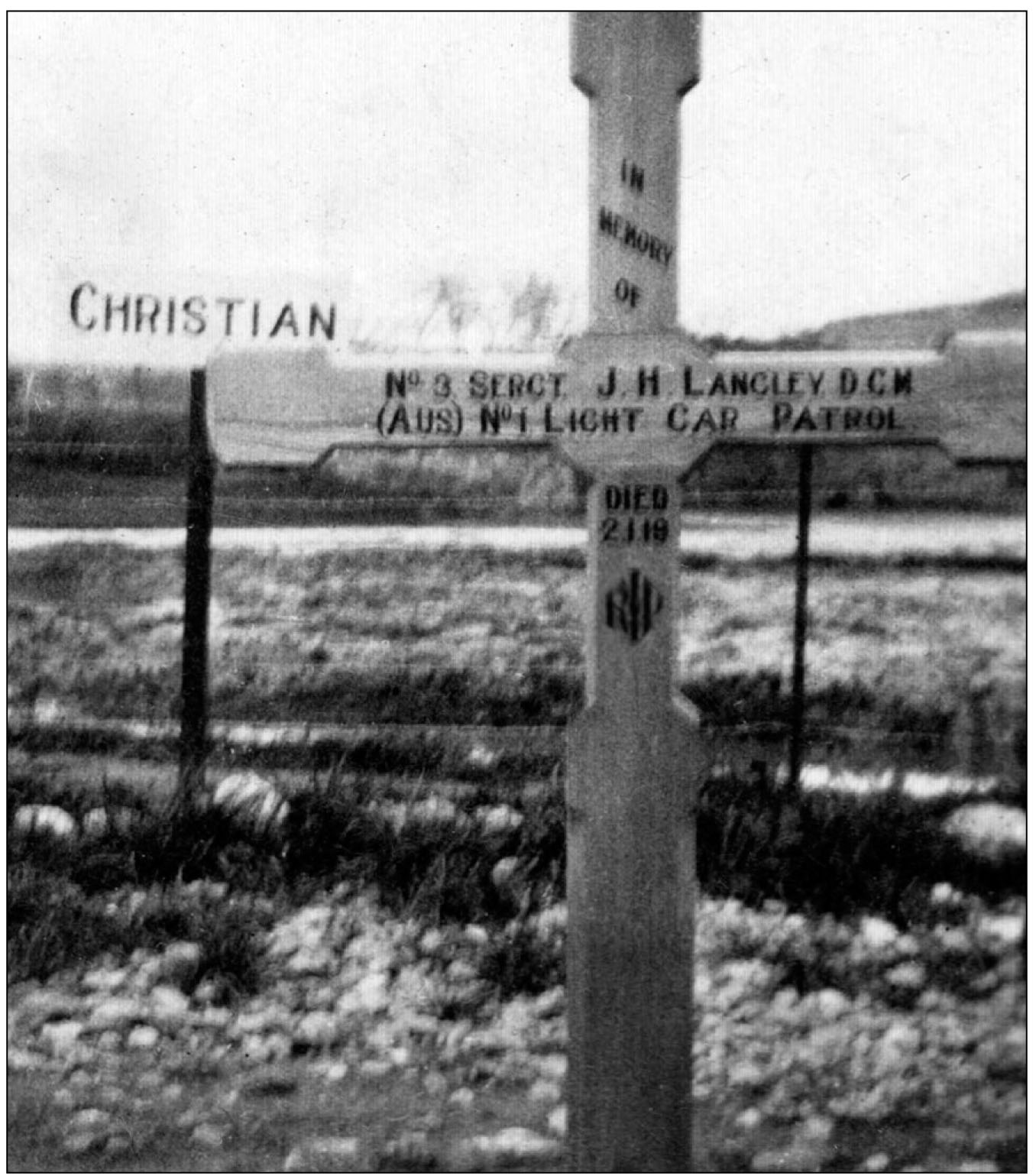

This day the 2nd January, was a day of gloom with the unit. Sergeant J. Langley, the gallant Non-Commissioned Officer who had led his car into numerous fights and who was the admiration of the whole unit, died at Aleppo hospital from malaria. He was a man of splendid physique, young, healthy and full of vigour, yet he died the second day after going to hospital. He received a bar to his DCM the week previously. He was buried with full military honours at Aleppo Cemetery.

55. Sergeant John Langley’s grave marker in the military cemetery at Aleppo, Syria. He was later reinterred in the Commonwealth section of the Beirut War Cemetery in Beirut, Lebanon (Creek collection ATM LCP.LC.005).

Trooper Leo Cohn

Aleppo.

January 12, 1919

Dear Mother,

Isn’t it sad about poor Jack. Mrs. Mackay’s death, Pies, Bert Henderson, Hugh McColl, what terrible lists for the past month or so. It quite takes the glow off this wonderful Peace that we have prayed for so long.

I have been out of hospital for a few days now and am all right once more. The unit is still up in the mountain but I am putting in a week or so with a Scottish Horse Patrol until I am properly fit.

I do not know whether Jack was in hospital last time I wrote. He had intended to go back to Puchc [sic] to see about our kit left there before the stunt and from there to Cairo. He had had slight jaundice but reckoned on the mild climate back further to fix him up. He grew that bad that he was persuaded to go into hospital for a week or so first and then down the line. The day after he was admitted I was able to get him to the next bed to me. He had grown a bit worse, but jaundice is such common complaint just now that the Doctor just put him on milk diet and said he would be right in few days. The next day he was semi-conscious and had passed a very bad night, so first thing in the morning I got the Doctor to come and have another good look at him. He suspected Malaria straight away, took a blood test but it proved negative but he was certain and gave him an injection of quinine.

Later in the day he gave him two more injections. All the next day and night he lay unconscious. The next afternoon he was just the same and although in the morning the Doctor said that most likely he would come too before night he had grown worse and the Doctor told us there was very little chance. At this time there were two more of the Patrol in hospital also. He was a little better after tea and two of us decided to sit up all night. I had been sitting with him for an hour or so when suddenly his breathing stopped or rather just faded away and he passed out absolutely in peace.

I wired to the ALCP and next day he arrived down with Norman and another fellow. Next we buried him in a small military cemetery just outside the town.

This has been a great blow to us all. He was a fine fellow and most of us idealized him. I don’t think you could have found a cleaner living fellow and that does more good amongst a crowd of men than Bible banging.

It was only our limited little unit that kept him from making a name for himself for he had a great personality.

Norman has gone off on the Hickson on a Cairo trip. He expects to be away six weeks or more. A fortnight would be the very shortest time I should say that he would work his way back to Palestine ....

Your loving son,

Leo.

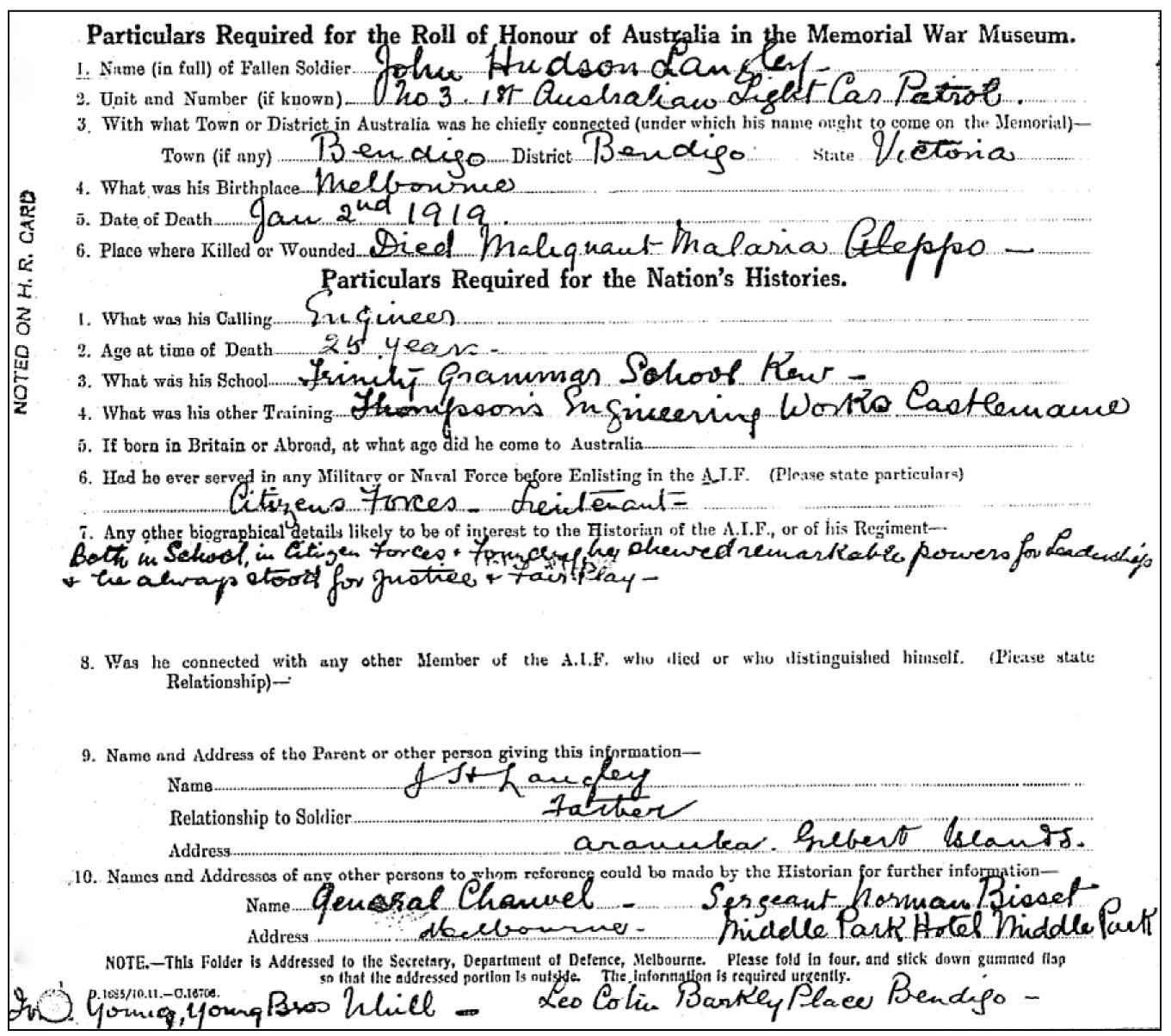

56. Jack Langley’s Roll of Honour circular for the Australian War Memorial.

Jack Langley.

An appreciation, by

Captain Alexander Barrett Keage

Master in Charge,

Trinity Grammar Cadets.

All those who were contemporaries of Jack Langley eight or nine years ago must have felt a sincere pang of regret when they learned that he had died of malaria at Aleppo at the beginning of the year. Jack had fought with distinction all through the Palestine Campaign, and had taken part in the adventurous dash, under the Duke of Westminster into the Sahara where they rescued the crew of an English ship from the Senussi.5

It is a painful reflection that while his audacious campaigns against the Turks were nearing a victorious end he was obstinately fighting a malignant foe in the form of Malaria, contracted some weeks previous in the Jordan Valley and to this insidious enemy he surrendered his life on 2nd January. Those who were intimately acquainted with Jack in 1910-11 need not be told that he was a brave as a lion. We guessed that, and we were not surprised to learn that he had been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He also has been personally recommended by his General for a Bar to the DCM a few weeks before he died.

It seems to be a characteristic of brave and chivalrous men to be also gentle and good-natured. It was this trait, no doubt, which endeared him to his comrades both at School and the Front. His O.C. Captain James speaks of him as: “Dear Sergeant Langley, my right hand man, and the finest fellow that ever lived.” He also refers to him as “Dear Old Jack my old comrade he has been with us from the very beginning, and has really been the backbone of the Battery since the day of its formation. The whole unit was broken up at the sad news, as he was undoubtedly the most popular man in our part of the force.”

Jack will always be remembered by his old friends and comrades for his cheerfulness and good temper, nothing, except injustice or wrong, could disturb his imperturbable good temper and equanimity and he was always straight and dependable: altogether, one of those for whom we have to thank god for making tradition of Trinity.

Born 10th April 1894

Entered the School 9th February 1909.

No 310 on School Roll.

Left December 1911.

Died of Malaria at Aleppo, 2nd January 1919.

For noble deeds as simple duty done,

In their Christlikeness known to god alone;

For high, heroic bearing under stress;

Fore hearts that no ill fortune could depress;

For every helpful word and kindly deed;

That formed occasion in brother’s need

We thank Thee Lord.

(The Mitre, May 1919, p. 40)

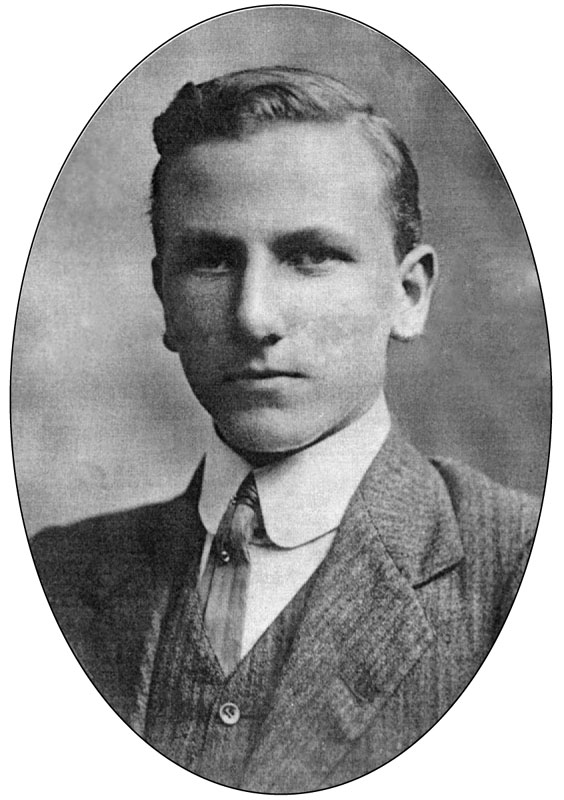

57. John H. Langley as a student at Trinity Grammar, Melbourne, 1911 (Trinity Grammar School Trinity 001).

26/1/19 &

31/1/19,

Dear Mother,

Have been very busy this last week so excuse change of date. Have been out of hospital or, rather out of Aleppo for over a week now and am with the Unit at Ain Tab, a filthy little Turkish and Armenian town. We are pretty short-handed and since being back I have had two trips to Aleppo, eighty miles of rotten roads and as cold as charity. They have been arresting some of the Young Turk (Party) and we have had to run them to Aleppo. It is Turkish territory and we were not too sure how they would take it, but there hasn’t been any fuss so far.

My fellow was the most evil looking man I have ever seen. He must weigh about twenty-one stone, huge face, pock-marked and with a Hindenburg moustache. I must send you a snap of him sitting beside me in the car and a fellow behind him with a rifle ready to pop him off if any of his crowd tried to hold us up on the road. He was supposed to have killed three or four hundred women and kids and while down in Mespot he was in charge of two labour battalions and instead of taking the trouble and transport to bring them back, he murdered the lot. Of course they were all Armenians. He confided in me going down and from what I could make out, Allah was responsible. I gave him plenty of spiritual advice, mostly because of a bag of gold-boys that he had ...

... As soon as I hear any definite word of being sent home I shall cable. There are rumours that the French are coming to take over all country north of Jerusalem.

Best love to all.

Your loving son

Leo ...

58. Troopers Cohn and Richardson escort a Turkish officer wanted for crimes in Mesopotamia (Cohn collection ATM LCP.LC.006).