THE MEN OF THE ORIGINAL ARMOURED CAR SECTION6

The Armoured Car Section (later the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol) was unique in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), as it was a self-contained unit with just 33 men serving between its formation in 1915 and disbandment in 1919. As such, it has been possible to trace the lives of all these men and identify trends such as factors in their enlistment and those that influenced their lives.

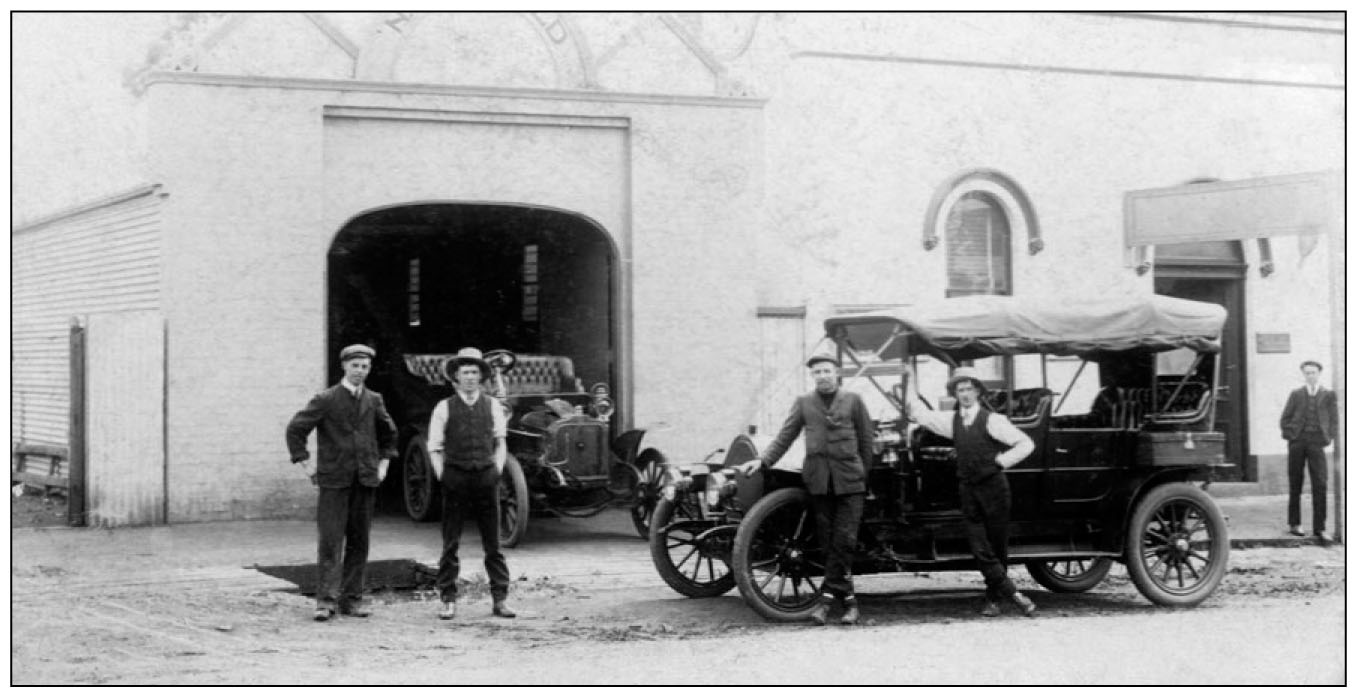

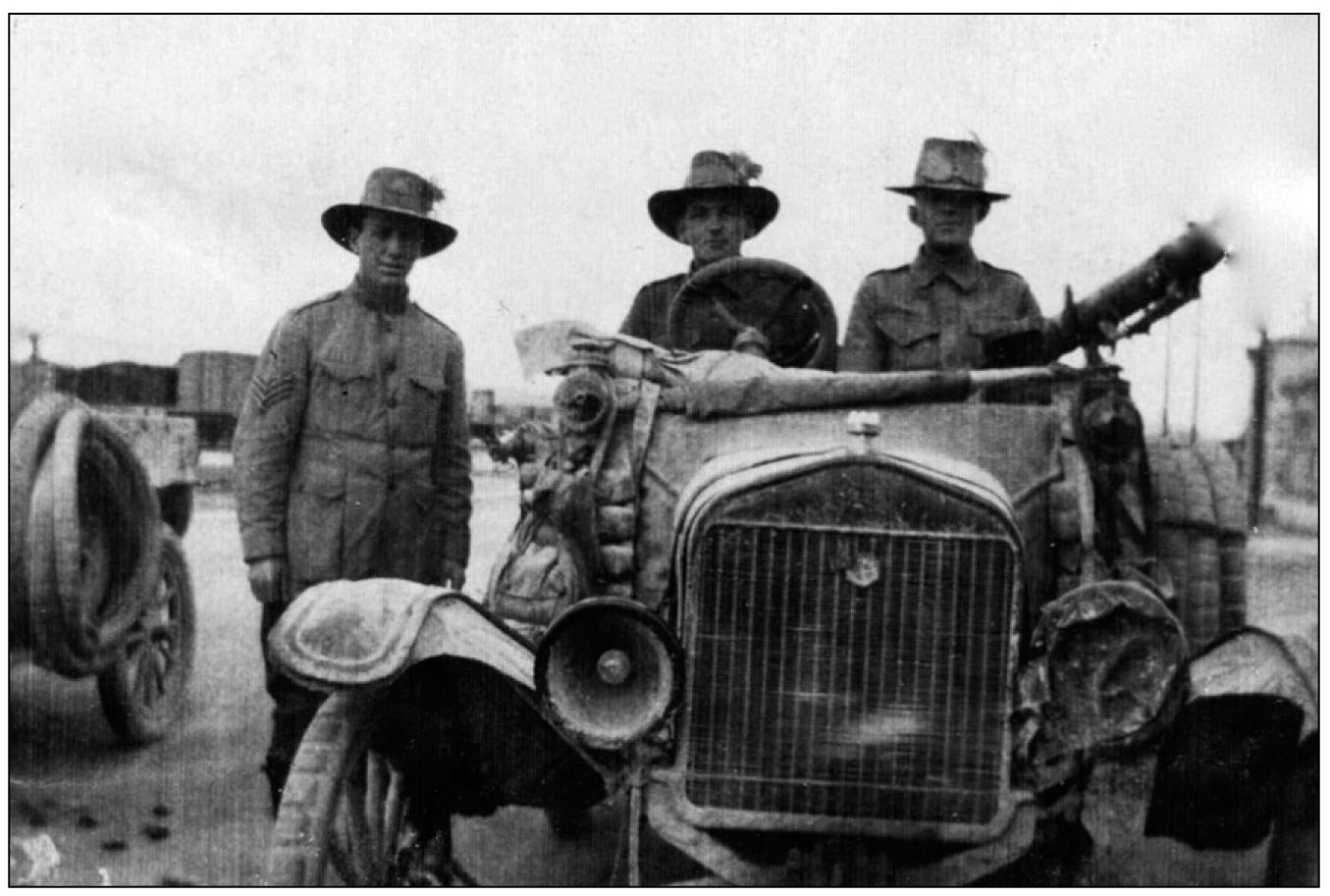

60: Ernest James behind the wheel of an early motorcar. James passionately embraced motorcars in the years prior to the Great War (James collection ATM LCP.EJ.001).

The unit consisted of two distinct groups. The first group comprised the ‘originals’ —James’ motoring enthusiasts of 1915–16 who committed time, effort and finances to make his vision a reality. As the war progressed, the circumstances of military service saw a call for reinforcements as members of the original group were transferred to other units. The second group consisted of reinforcements who were already serving in the Middle East when the Armoured Car Section arrived in August 1916. It is evident that, while these two groups were different in many ways, they also had a great deal in common.

The demographics of the 1916 Armoured Car Section originals reveal some interesting trends. The youngest member at the time of enlistment was Driver Harkin who was just 18, the oldest Lance Corporal Thompson, who was 41 years of age. The average age was 28. All were native-born Australians and only Driver Hyman had ancestors who hailed from outside the Anglo-Irish tradition. Religious affiliations show an overwhelmingly protestant influence as six were members of the Church of England, seven were Presbyterians and one Methodist. The originals were all Victorian apart from Hyman, who was South Australian and the lone enlistee from outside Victoria. Five men were married, the rest single.

In terms of the rural-urban divide, eight came from either Melbourne or Adelaide while six hailed from regional centres or smaller country towns. Thus 57% could be described as being of urban origin. However, the occupational status of the section reveals that none came from a traditional rural occupation. Nine members or 64% claimed engineering and technical backgrounds, and the remaining five came from the commercial world. Some men listed their occupations variously. Sergeant Young, for example, described himself as a clerk on some documents but not on others. It is evident, however, that all members were employed at the time of their enlistment.

There are several indicators of wealth or social class. At least five original members were educated at elite private school such as Coburg and Geelong Colleges, Melbourne and Trinity Grammars. Four held qualifications such as engineering or accountancy that required recognised qualifications. At least four members made significant financial donations to James’ project: Cornwell and Young donated expensive private motorcars, Thompson and Hyman made significant financial contributions. In Hyman’s case the figure of £100 was quoted. A comparison of this donation to his pay rate of 8/- per day as a motor transport driver suggests that he had donated 250 days’ pay just to join the unit!

The originals and their families were also active citizens within their communities. Among their parents and grandparents were a member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly, the Secretary of Education, a magistrate, one doctor, two Justices of the Peace, two Shire Presidents and an Anglican bishop. Both Cornwell and Young are recorded as benefactors to local charities and good causes.

Sporting achievements are also evident in the pre-war lives of the originals and during their military service. Local newspapers of the period recorded the cricketing and football achievements of Young, Hyman and Creek. Hyman was a gifted athlete, raced at the top professional levels in his native South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria, and played in both the South Australian and Victorian Football Leagues. Young and Hyman both owned racehorses. Millar managed the Richmond Racetrack where both horse and motor racing took place. Cornwell embraced speed racing of both cars and motorboats. In 1914 he and his brother won the Australian Motorboat Championship in Sydney.

61. Cadet Corporal Henry Harkin of the Melbourne Grammar School Cadet Unit. Many members of the AIF had their first military experience in the cadets or Militia (Harkin collection ATM LCP.HH.002).

Membership of the Militia and rifle clubs was also popular in Federation Australia. Of the originals, Captain James was the first to enter military service with the Victorian Defence Force prior to Federation, later serving with the 5th Australian Infantry Regiment, Commonwealth Military Forces, although by 1914 he had transferred to the Reserve of Officers. Millar had served in the Senior Cadets and with the Victorian Bushmen and Imperial Forces in the South African War. Sergeant Langley and Driver Morgan served with the 66th Infantry and Driver McGibbon with the Fortress Engineers. Others had also served in the cadet system. It is apparent that there were at least five members of the originals who had some military experience prior to 1915. A late arrival to the unit was Driver Bisset who had returned from service at Gallipoli in 1915.

A typical member of the 1915–16 originals would be protestant, 28 years of age, well educated by the standards of the day, employed in a technical or professional role, single, Victorian, and have Anglo-Irish ancestry.

On departure in 1916, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section would boast significant engineering, technical and driving experience in its ranks. There was also a range of prior military experience, with several having served in the Citizen Military Force (CMF) and two seeing active service either in South Africa or the 1915 Gallipoli campaign.7

Unlike most other units of the AIF, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section, and later the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol, did not receive dedicated reinforcement drafts from Australia. New members to fill vacancies and bring the unit up to strength came from the resources of the Australian Mounted Division. In all, 19 officers and men joined the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol between May 1917 and January 1918. The reinforcements present a very different profile to the men of 1915–16.

Ernest Homewood James

MVO, MC & Bar, VD

Ernest Homewood James was born in Richmond, Victoria, on 22 November 1879, the son of Charles and Mary James. Charles James was a prominent public servant who at one stage served as the Victorian Secretary for Education. Their son Ernest married Kate Melville, the daughter of the Honourable Donald Melville, MLC, and Catherine Melville at Brunswick in March 1909. In 1910 Ernest and Kate’s only child, Alice James, was born in Hawthorn.

62. The wedding party of Lieutenant Ernest James and Kate Melville in Brunswick in 1908. Next to James is Lieutenant Colonel Elliot, DCM. The Militia had been part of James’ life since the late 1890s (James collection ATM LCP.EJ.001).

Ernest James demonstrated a passion for engineering and motor transport from an early age. An article in the Melbourne Argus in 1938 reported: ‘One of his earliest recollections is being found in the pool of oil beneath an engine at the Centennial International Exhibition of 1888 by an anxious mother who had searched several hours for her mechanically minded son.’ His experience in automotive design and construction dated back to the 1890s when he witnessed the construction of the first successful steam-driven car built in Australia by Herbert Thompson of Armadale. At the age of 18, he and his brother Cyril built one of the first steam-driven launches on the Yarra River. James also developed a lifelong interest in scale models.

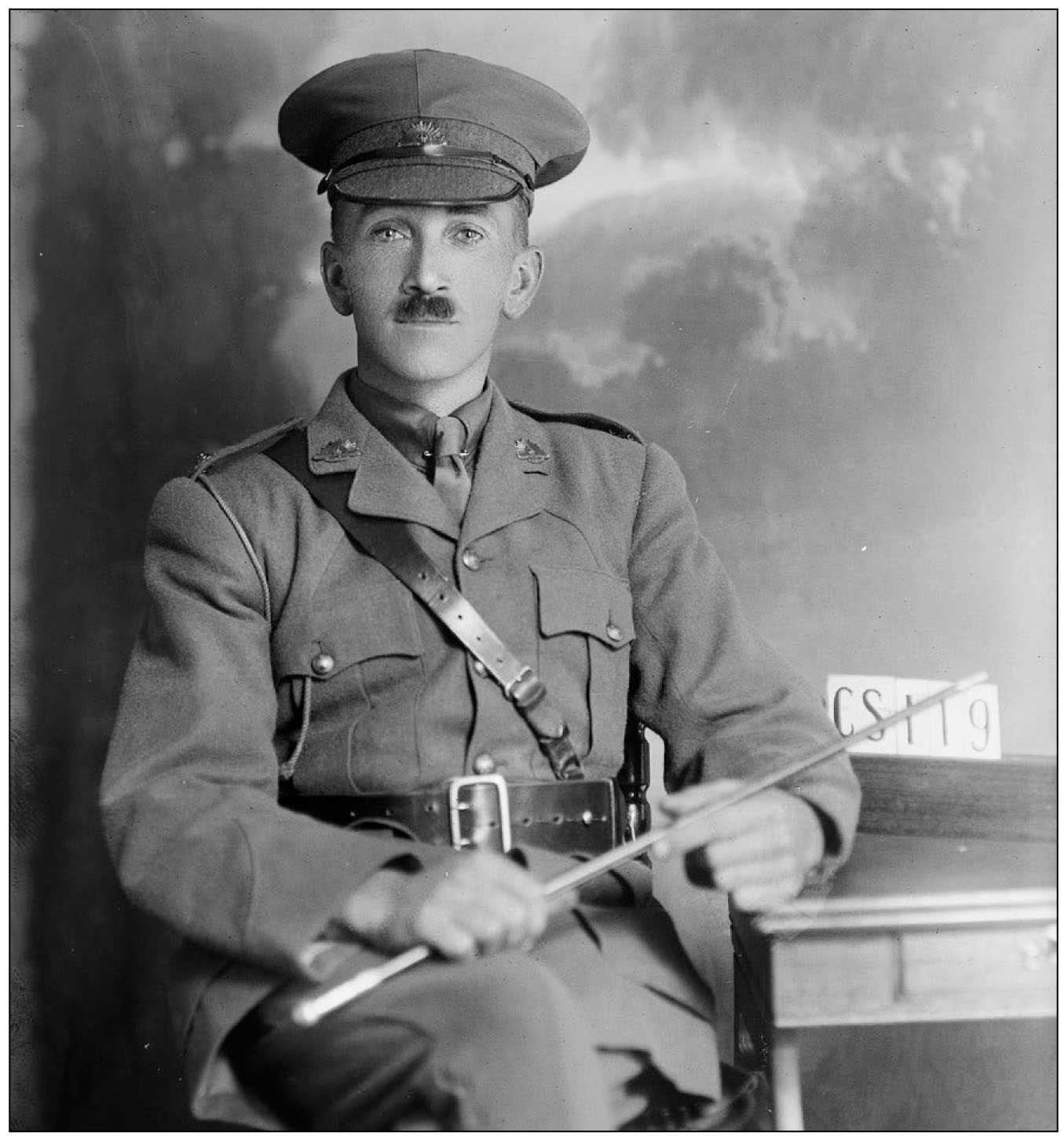

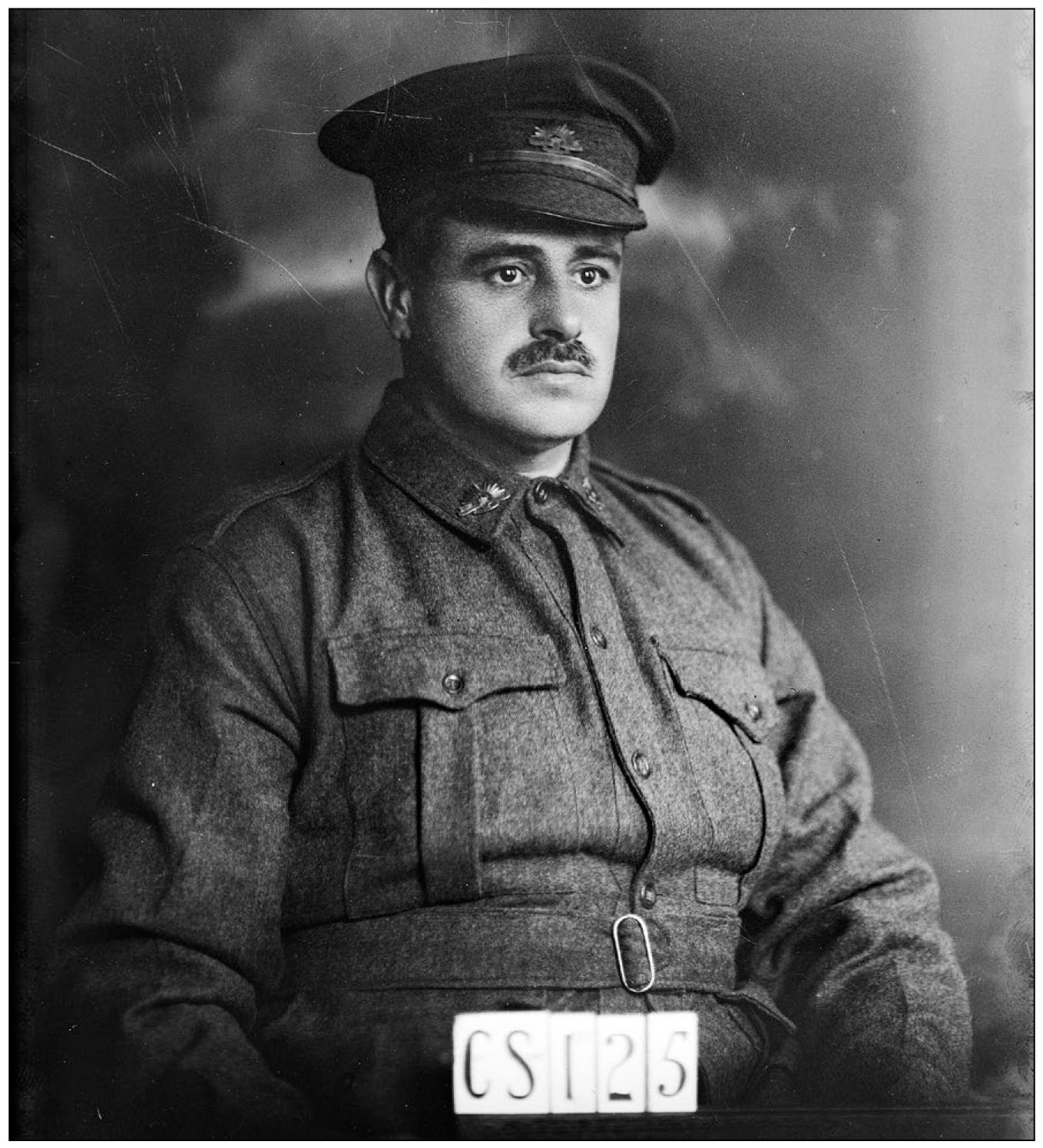

63 Pre-embarkation studio portrait of Lieutenant Ernest Homewood James, taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916. The portrait is part of the Darge Photographic Company collection. The Darge company had a concession to photograph personnel at both Broadmeadows and Seymour camps. The portraits of several members of the 1st Armoured Car Section were consecutively numbered by the Darge staff, indicating the unit’s personnel were all in attendance at Broadmeadows Camp at the same time, probably to make final preparations for overseas service (AWM DACS0120).

James’ military career began when he enlisted in the Victorian Military Forces circa 1897 and served with the Senior Cadets and 1st Victorian Infantry Regiment. With the formation of the Commonwealth, he transferred to the Australian Military Forces (AMF) on 1 July 1903 and served with the 5th Australian Infantry Regiment. On 28 August 1911 he transferred to the Reserve of Officers (3rd Military District).

In 1914 he appears on the electoral roll as a merchant residing in Riversdale Road, Hawthorn, Victoria. On other documentation his occupation is shown as an engineer. In the Edwardian years James promoted various technical innovations such as the use of suction gas technology for the lighting and heating of the greater Melbourne area. The interest in motor vehicles seems a logical extension of his childhood passion.

On the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914 James was one of a small group of motoring enthusiasts who pressured the Commonwealth government over the potential value of armoured cars as a weapon of war. At first James’ efforts made little headway with the Commonwealth, but later, with the support of Colonel Osborne of the Motor Transport Board, approval was granted for the design and construction of two armoured cars, a tender and a motorcycle with sidecar. The Vulcan Engineering Works in South Melbourne provided workshop space and support for this grand design.

Lieutenant James was transferred from the Reserve of Officers to the CMF on 1 April 1915 and posted to the 38th Fortress Company, Australian Engineers. From this posting, Lieutenant James oversaw the construction of the vehicles and recruitment for the Armoured Car Section. On 3 March 1916 Lieutenant James was appointed Officer Commanding the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section, Australian Motor Machine Gun Corps, AIF. He transferred to the AIF on the same day.

Lieutenant James and his section embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June 1916. Disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August 1916. The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve with the British 11th and 12th Light Armoured Car Batteries in operations against the Senussi tribesmen. On 3 December 1916 Lieutenant James received orders that the section was to be redesignated the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol. They were to hand in their vehicles and would be re-equipped with Model T Fords. On 1 January 1917 James was promoted captain. Between January 1917 and the Light Car Patrol’s disbandment in 1919, Captain James remained as officer commanding.

Captain James was recognised for his leadership in January 1919 with the award of the Military Cross ‘for continuous good work in command of his unit when he showed marked zeal and ability especially when acting with cavalry reconnaissances.’ In March 1919, a second Military Cross was awarded for actions ‘at Aleppo, on 24 and 25 October 1918, [where] he displayed great dash and perseverance in the way he attacked and drove enemy cavalry off the hills south of the town. He so disposed his cars that he held a strong force of enemy in check and denied them the crest and observation. All through the operations he displayed courage and resourcefulness.’

Captain James embarked on the Kaiser-i-Hind at Port Said, Egypt, on 15 May 1919 and disembarked at Port Melbourne on 23 June 1919. On return to Melbourne he did not seek an early discharge but was retained for duties with the entourage of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. James was to control six motorcars and their drivers as the Prince of Wales toured south-eastern Australia. For his services during this royal visit, Captain James was awarded the Royal Victorian Order (5th Class) in October 1920. In the same year he was also awarded the Volunteers Decoration.8

Captain James’ appointment to the AIF was terminated in Melbourne on 29 October 1920. For his services he had been awarded the Royal Victorian Order, the Military Cross and Bar, the British War and Victory Medals, the Volunteers Decoration and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.

Captain James resumed his service in the CMF with the 38th Fortress Engineers Company in South Melbourne on 1 January 1920. He transferred to the Reserve of Officers on 1 April 1924. His period of military service finally ended when he was placed on the retired list with the rank of honorary major on 31 March 1942.

James always remained a passionate advocate for Australia’s automotive future. In 1923, while Assistant Controller of the Australasian Equipment Company Ltd, he wrote a detailed letter to Melbourne’s Argus newspaper promoting the use of buses to ease congestion on Melbourne roads. Several other letters would appear in Melbourne newspapers promoting motoring interests. In 1924 James was the secretary of the Australian Omnibus Company of Victoria Street, Melbourne. Around 1930 James and a friend established the Model Dockyard in Swanston Street, a business that would become a Melbourne institution. While running this store James, a renowned maker of scale models, fostered several modelling clubs.

Like many old soldiers James retained his interest in the Australian Army. During the Second World War he wrote an extended letter to the Army outlining the tactical use of light cars and advocating their employment with the Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC). Later he donated his papers to the Royal Australian Armoured Corps Directorate. These were ‘lost’ for a time but have since found their way to the Army Tank Museum in Puckapunyal. The Army newspaper and RAAC Bulletin reported James’ death and described him as one of the Army’s most colourful characters. Both publications also included a reflection James had made on his service: ‘My worst job in the Army was acting lance corporal. I had everybody on my back at the same time!’ James died in Heidelberg, Victoria, in 1960.

Percy Reginald Vernon Cornwell

Percy Reginald Vernon Cornwell was born in Brunswick, Victoria, on 23 August 1882, the son of Alfred and Eleanor Cornwell. Alfred was an immigrant from Cambridge, England, and Eleanor a native of Wicklow in Ireland. Alfred established the colony of Victoria’s first industrial pottery kiln in Phoenix Street, Brunswick, in 1859.9 By 1900 Cornwell’s Pottery was a successful business, providing stoneware pipes to various municipalities throughout Victoria as well as exporting to the Americas.

Percy Cornwell was educated at Brunswick College where he attained excellent academic results.10 In 1905 he joined Cornwell’s Pottery as an apprentice, learning the manufacturing aspects of the family enterprise from the ‘bottom up’. Between 1910 and 1912 he graduated to travelling for the firm. He and his brother Fredrick were well schooled in all aspects of the business when they assumed management of the kilns and associated business in 1912.

Cornwell’s inclusion in Ernest James’ group of motoring enthusiasts in August 1914 would have come as little surprise to those who knew him. Cornwell, like many well-to-do businessmen of the Edwardian era, lived a life in which public service and the adoption of new ideas and challenges were considered a civic duty. Cornwell embraced both charitable works and the internal combustion engine with equal zest.

In October 1904 the Brunswick Leader reported a singing competition held in the Brunswick Town Hall for the benefit of the La Trobe Street Ragged Boys Mission and Home. As secretary, Cornwell was described as having worked ‘indefatigably to make the competition a success.’11 In 1909 Cornwell’s Pottery celebrated its Golden Jubilee and Percy Cornwell assumed a major role in organising the festivities. These included a works picnic at Mordialloc where he expended much effort in organising sports and entertainment for his workers. The day concluded with speeches that provide a genuine insight into the firm’s success: the engineering skills and innovation of Cr Allard, the works manager, the sense of community and common purpose, and the manufacture of a product that was ‘second to none’. The final presentation on behalf of the staff was to ‘Mr. Percy Cornwell on the occasion of the jubilee of his father’s works’ and expressed the hope that ‘as he was only a young man, he would live long and be a credit to the works.’12 In 1914 Cornwell demonstrated his patriotic spirit by presenting revolvers to staff members who were leaving the firm to enlist in the AIF.13

64 Portrait of Second Lieutenant Percy Cornwell, taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916. Cornwell was a well-known motor racing identity who donated his private vehicle for conversion as an armoured car (AWM DACS0119).

Percy and his brother Fredrick shared a love of speed and Percy raced both cars and powerboats. In early 1913 he toured New Zealand with his motorcar, demonstrating racing techniques, the New Zealand newspaper even reporting a crash at Alexandra Park. After returning to Australia Percy became involved in the Richmond races. In November he lent his 90hp Mercedes racing car to the American Douglas Campbell who raced at the Richmond Race Track before a crowd of 10,000 which reportedly attended with the ‘half pleasurable anticipation of an accident.’14 Cornwell also raced that day in the ten-mile event, although the race was forced to an early stop by rain. In February 1914 the Cornwell brothers travelled to Sydney Harbour with their boat the Nautilus II to compete in the Motorboat Championship of Australia. Percy sped overland from Melbourne to Sydney in his 75hp Mercedes, while Frederick embarked on the more traditional means of transport between capitals, the steamer Yarra.15 The championship boat race was conducted between Rose Bay and Manly. The Leader reported, ‘The Victorian boat beat her rival easily. Fred and Percy Cornwell had their engines in perfect order and maintained an average speed of 85 miles per hour.’16 Percy also had interests in less frenetic sports as a member of the Melbourne Cricket Club.

By the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, Cornwell had established himself as a successful community leader, businessman and sportsman. He appears on the electoral roll as a manger residing at ‘The Grove’, 35 Moreland Road, Brunswick. His attestation papers in 1915 noted that he was a mechanical engineer.

It is unclear when or how Cornwell became involved in James’ group of car enthusiasts. The first clear evidence can be found in late August 1915 when the Melbourne Leader newspaper reported in its motoring column ‘Motors and Motoring’: ‘The Armour of the experimental armoured cars has been tested and the work of constructing them is now in hand. Mr. Percy Cornwell has donated a powerful car, to be transformed into one of these war machines. He has volunteered to take an armoured car to Gallipoli.’17

In Australia prior to the Great War, the supply of a motorcar to the Department of Defence also gained the donor an honorary commission. However, Cornwell’s engineering, manufacturing and motoring experience would have made him a natural candidate for a leadership role in the new Armoured Car Section. Cornwell’s donation of a Mercedes is consistent with his previous history of public service and interest in motorcars.

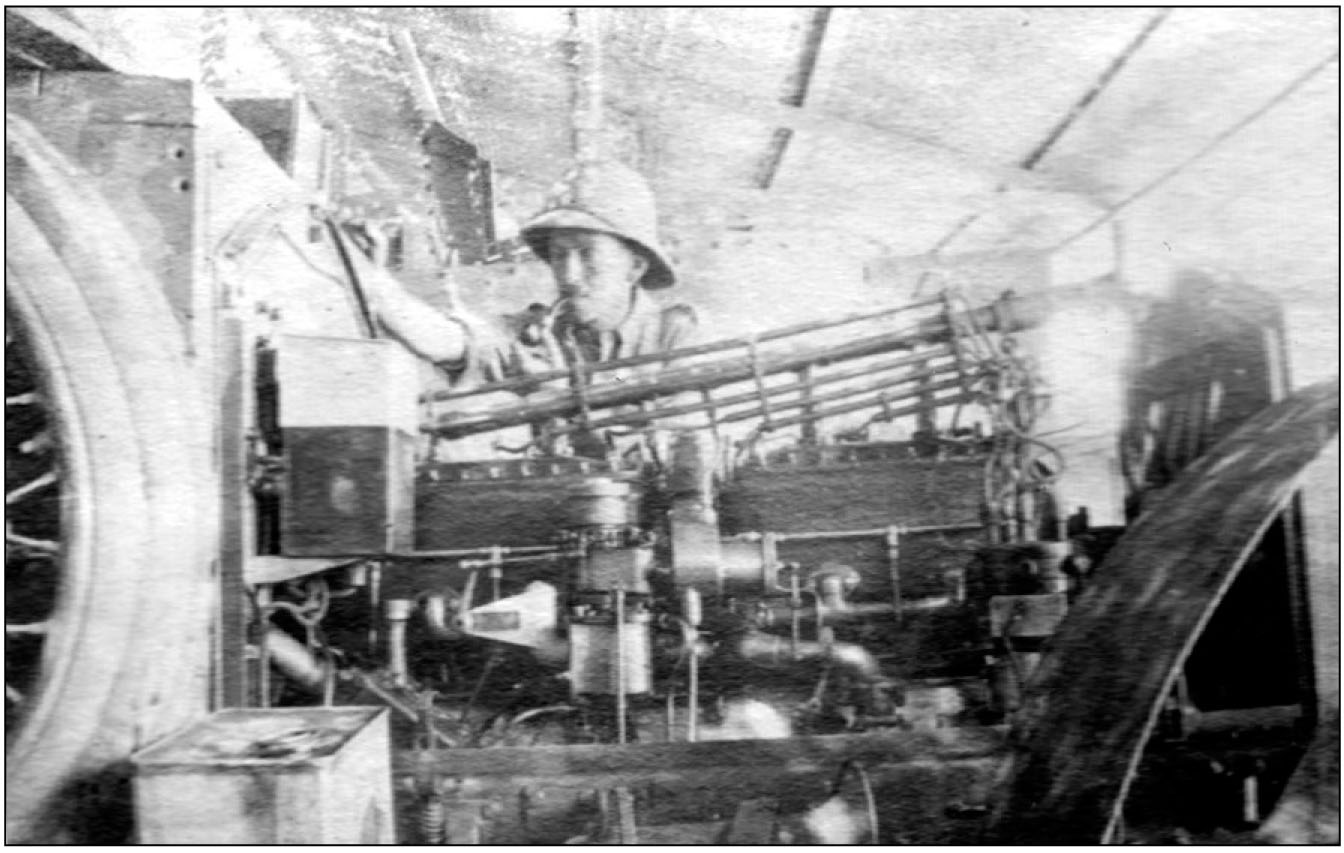

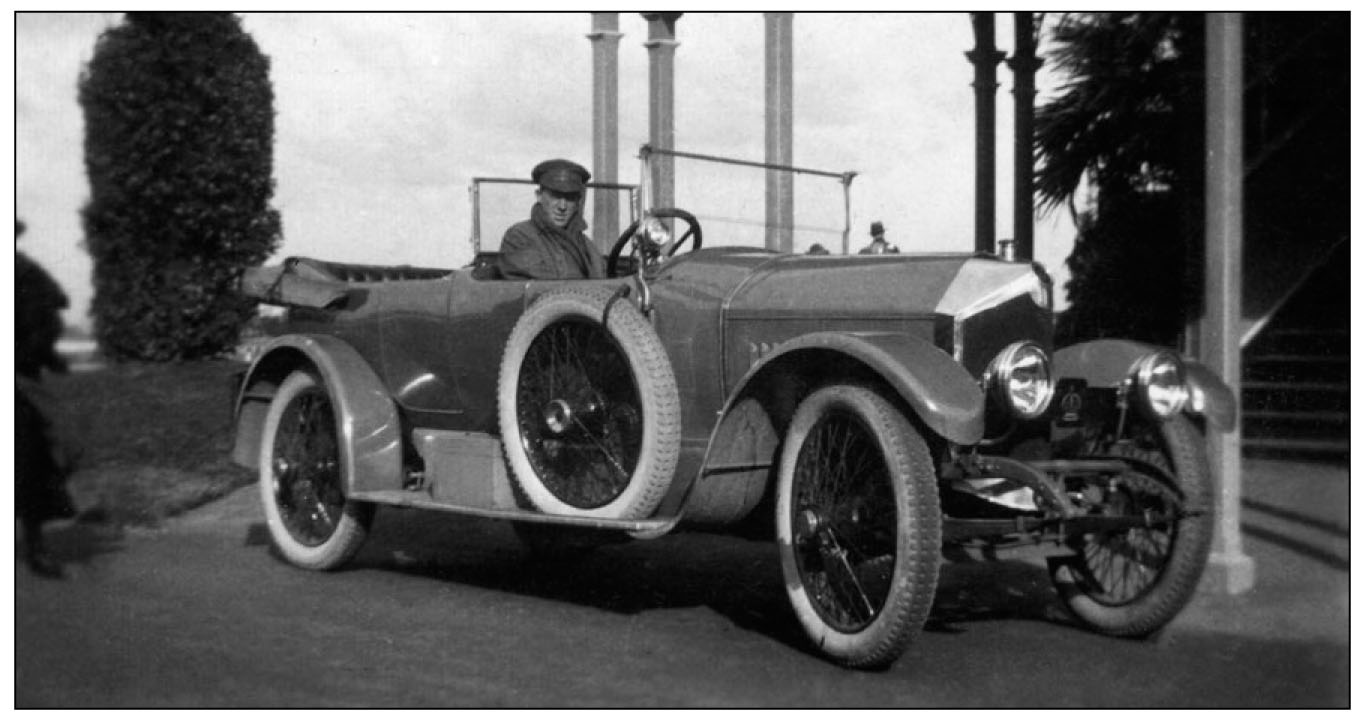

65 Lieutenant Percy Cornwell leaning over the engine of a Rolls Royce. Cornwell’s engineering abilities proved an asset to both the Australian Light Car Patrol and the British units (Young collection ATM LCP.IY.240).

Cornwell’s military service began when he was appointed provisional lieutenant in the CMF on 10 October 1915 and posted to the 38th Fortress Company, Australian Engineers. From this posting, Lieutenant Cornwell assisted with the construction of the armoured vehicles and the training of the Armoured Car Section. On 16 March 1916 Lieutenant Cornwell was appointed second lieutenant in the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section, Australian Motor Machine Gun Corps, AIF. He was administratively transferred to the AIF on the same day. In March 1916 Second Lieutenant Cornwell attended a Special Machine Gun Course in Randwick, New South Wales (NSW).

Prior to his departure on active service, Cornwell was given a send-off by the members of the Victorian Stoneware Pipe, Tile and Potter Manufacturers Association at Café Francis where his generosity and patriotism were recognised with the presentation of a portable typewriter suitable for use on active service.18

Second Lieutenant Cornwell and the other members of the Armoured Car Section and their vehicles embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June 1916. Disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August 1916. The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve with the British Army’s 11th and 12th Light Armoured Car Batteries in operations against the Senussi tribesmen. The section was later redesignated the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol and re-equipped with Model T Fords. On 1 January 1917 Cornwell was promoted lieutenant. He remained with the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol for the majority of the Palestine Campaign other than for some brief periods of hospitalisation, training and a detachment to the Topographical Survey Section, Sinai, at Khan Yunus between 15 May and 18 September 1917. On 1 February 1919 he left the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol to return to Australia on compassionate grounds. He embarked on the HMAT A11 Ascanius at Suez on 21 February 1919 and disembarked in Port Melbourne on 3 April 1919.

Lieutenant Cornwell’s appointment to the AIF was terminated in Melbourne on 11 May 1919. For his services he was awarded the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge. Lieutenant Cornwell was appointed to the Reserve of Officers, Australian Engineers, on 1 November 1920. He continued in that capacity until placed on the retired list on 30 June 1942.

On return to Australia in 1919 Cornwell returned to his role at Cornwell’s Pottery works. On 21 January 1920 he married Adele Sleeman. In the early 1920s Cornwell renovated ‘Annandale’ in Waterdale Road, Ivanhoe, his home showcasing the terracotta products of Cornwell’s Pottery works.19 In the late 1940s the Cornwells relocated to Glenferry Road in Malvern. Percy Cornwell died in Armadale on 26 April 1962 and was cremated at the Springvale Cemetery where his ashes were interred in the memorial garden.

Ivan Sinclair Young, J. P.

Ivan Sinclair Young was born in Nhill, Victoria, on 7 July 1889, the son of John and Louisa Young. John Young was a prominent Wimmera businessman and citizen with interests in agriculture and stock and station supplies. He was also the president, at various times, of the Nhill Agricultural Society and Shire Council, member of the Nhill Water Trust, and a Justice of the Peace.20 By the outbreak of the Great War, Young Brothers Auctioneers, Stock and Station Agents, was a well-established trading company in the Wimmera region.

Ivan was educated at the Nhill School and Geelong College, where he distinguished himself in academics and sport.21 He pursued higher education at Roseworthy Agricultural College in Adelaide, South Australia, in 1911 where he graduated with first class honours in dairying and surveying. He was also an active sportsman, batting for the Nhill cricket team, playing golf, and as a member of the Nhill Football Club. In 1914 Young showed an interest in politics, becoming secretary of the Nhill branch of the People’s Party.22

Ivan Young enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 9 July 1915 and was allocated to C Company, 31st Infantry Battalion. In Broadmeadows Camp, Young was reunited with Private Herbert Creek, who was formerly employed by Young Brothers as a mechanic, and friend Sergeant John Langley of Bendigo. All three men would soon be recruited into the new Armoured Car Section.

Young’s enlistment was not as straightforward as his service record indicates. Young had donated his private car, a Daimler, to provide a chassis for Captain James’ project. This action gained him a position in the Armoured Car Section and promotion to sergeant on 19 January 1916. As part of James’ team he assisted in the conversion of the vehicles to armoured cars.

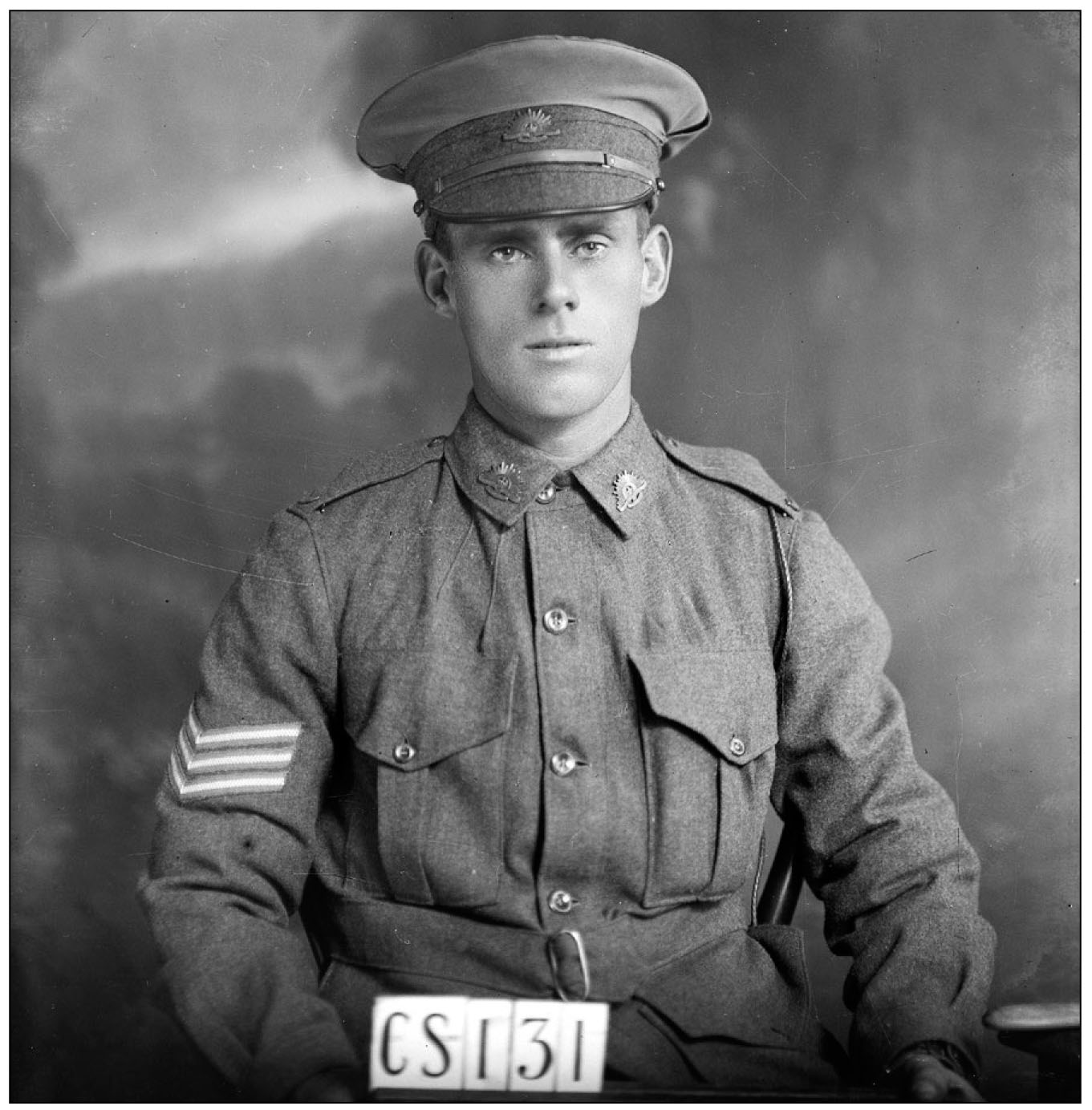

66 Sergeant Ivan Young, who donated his Daimler car for conversion to the armoured car ‘Gentle Annie’, photographed in the Darge Photographic Company’s temporary studio at Broadmeadows Camp, Victoria, in May 1916 (AWM DACS0131).

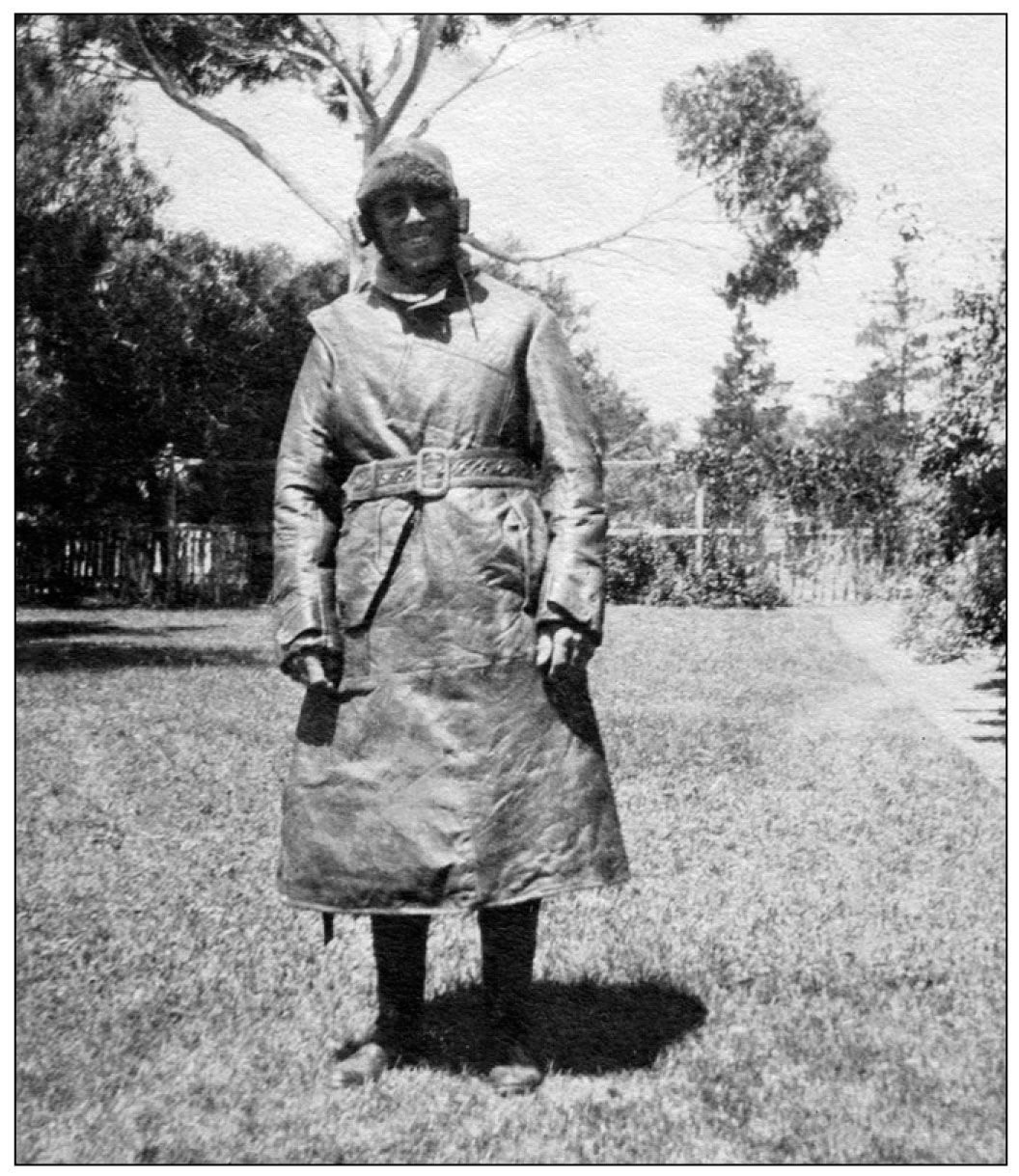

67. Lieutenant Ivan Young, Australian Flying Corps, wearing his flying suit at Bishop’s Court, Bendigo, in 1918 (Young collection ATM LCP.IY.249).

The Horsham Times records the emotion and patriotic feelings of the time that characterised Private Young’s farewell at Nhill’s Royal Hotel, which it reported in detail:

A social to Private Ivan Young was tendered at the Royal Hotel, when the occasion was also availed to say good-bye to Sergeant J. Langley and Corporal W. Nunan. Private Young was handed a gold-mounted fountain pen and wished well by his friends. In acknowledging the toast of the parents, Mr. John Young said that right from the beginning he knew well that Ivan wanted to enlist. Had he been in his son’s place he would also have enlisted for active service. He knew how Ivan felt, and told him if he desired to go to the front he would not stand in his way. The titanic struggle was not a question of “my country, right or wrong” but right against being completely crushed, before a lasting and honourable peace, could be attained. Realizing that Great Britain had entered into this great conflict on the side of liberty, justice and freedom, Mrs. Young and himself offered not the least objection to Ivan’s decision to volunteer for active service.23

Sergeant Young embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June, disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, where the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August 1916. Young remained with the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section and later the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol during the Egyptian Campaign until March 1917 when a new opportunity presented itself.

On 10 March Young was detached from the Light Car Patrol to attend a school of instruction at Abbassia. Having completed the course, he proceeded to the School of Aeronautics on 24 March and was taken on strength by the 58th Reserve Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC), on 12 April. Between 6 and 15 May he attended a wireless course at the School of Aero Gunnery at 20th Wing, RFC. On graduation he was promoted second lieutenant and, on 26 May, posted to the 67th Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC), at Moascar as an air observer.

The Nhill Free Press published a letter from Lieutenant Young in September 1917 in which he describes his experiences in the AFC:

Things are pretty quiet here for the present. We were at Jaffa for a while but have now shifted to a place called Din el Bulah right in amongst thick orchards of big fig trees and vines which at present are laden with fruit which should be ripe in about a month. It’s as hot as anything, but luckily we have a sea bath fairly often. As you know we are still in front of Sampson’s city, Gaza, which the Turks strongly hold and with whom we had two scraps, called the first and second battles of Gaza. Some people at home think it’s a holiday out here. Old Gallipoli men say that April 19 was worse than any day they had on the Peninsula. We have just about got on even terms with the Hun in the air. So far I’ve been lucky enough to dodge any stray Huns and their “Archies”. The latter is the thing to shake you up. When you are sailing round at 7000 or 8000 feet viewing proceedings below, High Explosive or shrapnel bursts fairly close and you hear the pieces whistle, you are wondering all the time if they’ve chipped any part of the machine or whether it will collapse with you and it’s a dammed long way down to mother earth. The armored cars are near here on our right flank with the Light Horse at a place called To el Para; it’s very interesting seeing these old biblical places even if it’s from a fair height. Have seen Jerusalem and the Dead Sea from a distance and have sailed over Beersheba, Hebron, Giza, Irgey, Hareira, Sharia, and other places, and you get a few “Archies” put up at you from most of them, so, needless to say, one doesn’t dwell for a week over them. We have lost two men in the last couple of weeks, so we have just about got the Hun bluffed; for the previous couple of months our air casualties were very heavy. You ought to see the caterpillar tractors here pulling enormous loads over sand dunes. They are built on the same principle as the tanks and no sand dunes ever made will stop them. Remember me to all the boys.24

In July 1917 John Young Senior died suddenly in Nhill, leaving the management of Young Brothers in serious difficulties.25 Soon after, Lieutenant Young was granted compassionate leave to return to Australia to settle his father’s estate.26 He embarked on the HMAT A42 Boorara at Suez on 23 August and disembarked in Port Melbourne on 27 September.

Lieutenant Young’s appointment to the AIF was terminated in Melbourne on 22 October 1917. For his services he was awarded the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.27 Lieutenant Young was appointed to the Reserve of Officers in 1920 and remained on the reserve list until the 1930s when he returned to the Militia as Officer Commanding B Squadron of the newly raised 19th Light Horse (Armoured Car) Regiment. He relinquished this position when he left the district and returned to the Reserve of Officers.28 He was placed on the retired list on 19 December 1944 with the rank of honorary captain in the Australian Armoured Corps.29

Young’s return to Nhill appears to have been not altogether a pleasant experience. His late father had been a strong advocate for the introduction of conscription in 1916; furthermore, many local families had suffered hardship caused by the absence of fathers, sons and husbands on active service. Nhill also had many entries on the local honour roll by the end of 1917. Lieutenant Young’s return on compassionate and business grounds caused significant disquiet in some sections of the community. By December the local Member of the House of Representatives, Mr A.S. Rodgers, had entered the debate when he spoke at a Reinforcements Referendum Campaign at Nhill’s Theatre Royal:

Before he commenced his address Mr. Rodgers said he wanted to refer to another matter, a matter which caused him considerable pain, viz the fact that certain people had seen fit to defame Lieutenant Ivan S. Young of the Royal Australian Flying Corps. Now he wanted the true facts in regard to Lieutenant Young’s case to be known to the people of Nhill and District. On July 3rd last. Mr. John Young died. Lieutenant Young was on active service, and a cable was dispatched asking for leave of absence for Lieutenant Young, which was granted. Mr. Thomas Young, of Horsham, one of the principals of Messrs. Young Brothers interviewed the speaker and said he believed the altered circumstances with regard to the family life and business in Nhill, which represented the life’s work of the late Mr. Young, were such that Lieutenant Young should take up his father’s and the family’s responsibilities, he being the only male member of the family—the mother being in delicate health and there being only two single daughters and the latter could not be expected to supervise family and business matters.

He (Mr. Rodgers) was asked to put full particulars of the request before the military authorities which he did; therefore, the proposal was made that Lieutenant Young be relieved from further military duty. He took the full responsibility and submitted to the family request in making the application, and the case rested solely on its merits. His relationship with the Defence Department was purely official. He had no private interview over the matter with the authorities; it was done by official letter, a copy of which Mr. Rodgers read to the audience. However, a somewhat similar case had previously come before the military authorities when the request was granted. Lieutenant Young was still a soldier of the king, he is not yet discharged although, Mr. Rodgers believed that, in the altered circumstances of the family, his request would be granted.

The slanderers of Lieutenant Young doubtless were not aware of the fact that he was on active service for 14 months and 7 months he served against the enemy in the Libyan Desert, and afterwards joined the Royal Australian Flying Corps. For three months now was flying over enemy territory in Palestine where, it is stated, on an average 600 shells per day are fired at each airman who participates in reconnoitring work. It ill becomes anyone in this district to slander a local soldier who has daily risked his life in the defence of his country and for those who remained at home.30

On return to Australia, Ivan Young married Nancy Chisholm in Sydney on 20 March 1918. The Reverend Doctor Langley, Bishop of Bendigo, celebrated the wedding. Young became a member of the Nhill Racing Club and a racehorse owner. His love of technological progress also extended to the world of aviation. In 1920 the Nhill Free Press reported that he had received a wire from Sir Ross Smith that he would fly his Vickers Vimy over Nhill during his flight from Adelaide to Melbourne.31 Young Brothers also provided the land for the first aircraft landing ground at Nhill. In November 1933 Young and his wife were part of the official party that greeted Sir Charles Kingsford Smith at Nhill during his visit to the Nhill Aerodrome.32 Young also showed a keen interest in photography and early home movies.33

In the twenties and thirties he was prominent in many community activities in the Nhill district. He retired from an active role in the management of Young Brothers in January 1936, later relocating to central Victoria where he took up the pastoral property Zintara at Trawool. In 1943 he was appointed a Justice of the Peace.34 Prior to 1949, Young relocated to the Melbourne area where he died in Kew on 12 July 1966.

Ivan Young’s son John served as a sergeant in the 2nd Cavalry Division Signals during the Second World War.

Herbert Creek, DCM, RVM

Herbert Creek was born in Hamilton, Victoria, on 2 March 1888, the son of Joseph and Ellen Creek. At the time of his enlistment he was a motor mechanic employed at Young Brothers’ Motor Department in Horsham. In 1911 he acted as chauffeur for the Governor of Victoria, Sir Thomas Gibson-Carmichael, when he toured the Western District. Advertisements for new cars sold by Young Brothers in 1914 promised that Bert Creek would act as an instructor to all who purchased cars. Creek was also a talented footballer, playing in the centre for Horsham prior to the Great War.

68. Herbert Creek standing outside McDonald’s Motor Garage, Hamilton, circa 1912. Creek would be one of the first men in Victoria to make his living from this new technology (Creek collection ATM LCP.HC.021).

Creek enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 2 July 1915. He was taken on strength by A Company, Depot Battalion, at Flemington. On 12 July he was posted to C Company, 31st Infantry Battalion, at Broadmeadows. His former employer, Ivan Young, was also serving in the 31st Battalion and it is likely that Creek accompanied Young to the Royal Park Depot where his mechanical and driving skills were used in the construction of the armoured cars. On 17 January 1916 he was promoted corporal and was taken on strength by the Armoured Car Section. The Horsham Times of 15 February reported that Ivan Young and Bert Creek were part of the new Armoured Car Section and that Creek would be a driver.35

69. Studio portrait of Corporal Herbert Creek taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916. Creek was later promoted sergeant and commanded one of the 1st Light Car Patrol’s gun cars equipped with a Lewis light machine-gun (AWM DACS0132).

Creek embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June 1916. After disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August 1916. The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve with the British 11th and 12th Light Armoured Car Batteries in operations against the Senussi tribesmen.

On 1 August 1917 Creek was promoted sergeant. Other than a period of hospitalisation for malaria in early 1918, Creek remained with the Light Car Patrol in the Palestine Campaign until the end of hostilities. On 20 September 1918 Creek’s driving skills and courage were tested close to Ajule where his patrol encountered three enemy motor lorries containing men and equipment. He boldly cut the lorries’ avenue of escape, forcing them to surrender. For this action he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

In December 1918 an extended letter from Bert Creek appeared in the Hamilton Spectator:

Private Bert Creek, who up to the time of his enlistment was employed in Messrs. Young Brothers motor department Horsham, writing to his mother from Damascus, states “that the Allied advance from the Dead Sea to Damascus was an eventful one”. At the time of writing (October 11) he was quartered on the outskirts of the city. “The place,” he added, “was rather out of order when we got there, but our people are getting it cleaned up, and put in order. The trams were not running, but were getting ready.” On the advance, sometimes travelling all night, the Allies captured in one instance an aerodrome, four aeroplanes, motorcars, motor lorries, and a quantity of material. At Bieran they had practically surrounded the Turkish army, so they stayed there patrolling the roads and collecting prisoners who were wandering about in all directions, and did not know what to do or where to go. At Iliafia, Private Creek’s patrol, the only Australians among the British and Indian troops, watched the coast for 20 miles. Subsequently they proceeded through Nazareth and on to Tiberius (where they had a swim in the lake), crossing the Jordan at Lake Hula, and then the advance proceeded to Damascus. The Turks burnt their petrol and ammunition dumps, and “it was”, Private Creek adds, “the biggest and best fire I have ever seen.” Next morning, the town was theirs, and Private Creek, who escorted the general through the town, states that the population came out into the streets and cheered and clapped. Nearly all the prisoners taken were in a state of starvation, and although the army of occupation was put on half rations in order that the prisoners might be fed, the latter died in hundreds. As there were a lot of grapes, vegetables, and sheep about, he could not understand why the Turks starved. The 150 miles’ advance had been somewhat difficult, and supplies had to be kept up to the troops by means of motor lorries but when the railways were running again things would improve.36

On 15 March 1919 Creek was posted to the AIF Details Camp pending his return to Australia. He embarked on the HT Kaiser-i-Hind at Suez on 16 May and disembarked in Port Melbourne 16 June. Sergeant Creek was discharged on 31 July. For his service he was entitled to the Distinguished Conduct, British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.37

On arrival in Australia, he joined the 1919 Royal Tour of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales as a driver, along with Motor Transport Driver Harkin, another former Light Car Patrol driver. The Horsham Times newspaper reported that Sergeant Herbert Creek of Horsham, son of

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Creek, of Hamilton, was employed as one of the drivers in connection with the visit of HRH The Prince of Wales, on his recent visit, had a unique compliment paid to him. At the Prince’s request he was invited on board HMS Renown, and made the recipient of a valuable tie pin and decorated with the Victoria Medal in recognition of the faithful and conscientious manner in which he had discharged his duties. There are only six Victoria medallists in Australia, so that the honor conferred on Sergeant Creek is a valued one. The Prince also gave one of his photographs to Sergeant Creek.38

70. Herbert Creek at the wheel of HRH the Prince of Wales’ limousine during the Prince’s Australian tour (Creek collection ATM LCP.HC.032).

In 1954 Bert Creek recalled his time with the Prince of Wales to a South Australian journalist who wrote that Creek was:

No. 1 of four chauffeurs engaged to drive the Prince of Wales on HRH’s Australian tour. “I drove the Prince round when he had an extra seven days off the record,” Bert told us. “He went along very quietly. I took him to Caulfield where he tried a horse over the fences and to Elsternwick for golf, to Morphettville racecourse for another private ride.” Lord Mountbatten was the Prince’s companion on these unofficial trips. The Prince was a likeable man. “When he said goodbye on the Man-o-War steps in Sydney Harbour, he gave us an autographed photograph of himself, and a medal. He also gave me a platinum tie pin with his crest on it.” Bert Creek won the DCM in Palestine with the Armoured Car Section (Capt. E. H. James, MC).39

For this service Creek was awarded the Royal Victorian Medal on 1 January 1920.

After the Royal Tour, Creek returned to Horsham where he resumed his trade as a mechanic and hire car operator. He married Mary McClounan at the Presbyterian Church in Horsham on 18 September 1922. It is apparent that Creek lived a colourful life. In September 1930 the Horsham Times newspaper reported on a raid by Melbourne detectives at the Royal Hotel where off-course gambling was taking place. Creek, with fellow returned soldier Murphy, were charged with being ‘SP bookies’.40 Later,

... in the Magistrates Court the police prosecutor called for a minimum penalty of £20 be imposed. Murphy was a returned soldier and was incapacitated from work by war wounds and he was trying to eke out a living in these unfortunate circumstances. Mr. Bennett entered a plea for Creek, who was also a returned soldier, and added that the defendant had already been fined £20; he had been awarded high war honours and had served the Prince of Wales as a motor driver. If the defendant were fined it would inflict great hardship. The prosecuting sergeant suggested to the Magistrate that the further hearing of the defendant’s case be adjourned. Mr. Bennett: “It would be a better corrective than penalizing him.” The Magistrate asked defendant Creek, “if he was prepared to give up the practice.” The defendant said he was prepared to do so as a licensed bookmaker because he could not follow his trade of a motor mechanic. The Magistrate said: “You see betting is not a very profitable game.” Defendant Creek replied: “Not after today!”41

In his later years, Creek was interviewed several times by journalists about his experiences in the Great War and the 1919 Royal Tour. Herbert Creek retired to an aged care home in Bendigo where he died on 8 April 1980.

Robert Wilson McGibbon

Robert Wilson McGibbon was born in Albert Park, Victoria, on 11 June 1896, the son of John and Mary Margret McGibbon. At the time of his enlistment he was a mechanic residing in Mowbray Street, Albert Park.

71. Portrait of Driver Robert McGibbon, one of the 1st Armoured Car Section ‘originals’, who transferred to the Australian Flying Corps as an air mechanic in August 1917. At war’s end he remained in Palestine working with the American Red Cross where he met his future wife, Ruby, an American nurse. The McGibbons eventually settled in Maryland, USA (AWM DACS0126).

McGibbon enlisted in the 34th Electrical Company, Australian Engineers, CMF, in Melbourne in June 1915. He transferred to the AIF in Melbourne on 25 March 1916. On 3 April he was posted to C Company, 22nd Depot Battalion, at Royal Park, followed by a posting to the 24th Depot Battalion at Royal Park on 12 May.

On 20 June McGibbon was taken on strength by the Armoured Car Section as a motor transport driver and embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne. After disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August. The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve with the British 11th and 12th Light Armoured Car Batteries in operations against the Senussi tribesmen. On 8 December the section was redesignated the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol and re-equipped with Model T Fords.

On 6 August 1917 McGibbon was posted to the 67th Squadron, RFC (later 1st Squadron, AFC), and was mustered as a second class air mechanic (fitter and turner). He was promoted to first class air mechanic on 1 March 1918. On 19 July he was re-mustered as a motor transport driver.

In January 1919 McGibbon was approached by the American Red Cross in Palestine and the Near East with an offer to take charge of the repair workshops in Jerusalem. He accepted this offer and was discharged in Cairo on 11 February. McGibbon’s further service in Palestine with the Red Cross is undocumented. For his service in the AIF he was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.42

McGibbon returned to Australia in 1920 with an American war bride, Ruby, who had served as a nurse with American forces during the war.43 They settled in Abbotsford, Victoria, where he resumed his civilian engineering trade, However his return to Australia was short-lived as the McGibbons emigrated to the United States (US) in 1925. Robert travelled to the UK and resided briefly at Jeaturgh Road in London prior to embarking on the SS Minnekahda for New York on 11 July. The McGibbons settled in Midland, Maryland, where he worked as a machinist and, in November 1925, became a US citizen. The family finally settled in Allegany, Maryland, where McGibbon worked for the Celanese Corporation of America. During the Second World War there are numerous reports in the Cumberland newspapers of the McGibbons’ undertaking Red Cross and hospital work. In 1942 McGibbon registered for Selective Service but was not called up. Robert McGibbon died in Washington, District of Columbia.

During World War II, McGibbon’s father, John McGibbon, served in the CMF as a corporal with the 115th Australian Military Hospital at Heidelberg between 1941 and 1947. McGibbon’s son, David Allan McGibbon, served in Headquarters 2nd Battalion, 115th Infantry Regiment of the Maryland National Guard.44

Oscar Henric Hyman

Oscar Henric Hyman was born in Mitcham, South Australia, on 25 November 1877, the son of Robert and Sarah Hyman. He married Harriette Brennan on 16 November 1898. Hyman held the licenses for several hotels in the Adelaide area including the General Havelock, the Caledonian, Earl of Zetland, and the United Service Club. At the time of enlistment in 1916 he was a licensed victualler and resided in Dover Street, Malvern, South Australia.

Prior to the Great War, Hyman demonstrated considerable sporting talent, playing Australian Rules Football for South Adelaide in the South Australian Football League and for Collingwood in the Victoria Football League. He concluded his playing career in 1910 having represented South Australia on nine occasions and played 41 games with Collingwood.45

In August 1905 Hyman played for Collingwood in a match in Broken Hill. The Barrier Miner reported a post-match incident in dramatic terms:

Sunday Night’s Outrage. The young man Oscar Hyman, a member of the Collingwood team of footballers, who had his skull fractured by a blow from a stone thrown in Blende Street on Sunday night, is still in the Hospital. He is no worse than he was yesterday. He will require rest and quietness for a time, and will probably be compelled to remain in the institution for a couple of weeks to come. “J.F. Dunn” writes to express his indignation at the fact that a visitor to the city should have been treated as Oscar Hyman, the Collingwood footballer, was on Sunday evening. He hastens to insist that the assault was not the work of any worker. Our correspondent’s sentiments will be universally shared, but the fact that a man is under arrest on a charge of having assaulted Hyman it is obviously improper to at present discuss the most regrettable happening.46

This story appeared in newspapers across Australia. The case’s conclusion at the Magistrate’s Court in November was reported in some detail:

Stone throwing Outrage. The defence was that the quarrel was caused by the aggressiveness of Hyman and the Collingwood footballers who were in his company on the night of the alleged wounding. William A. Hutchinson and John Dorman both swore that McCourt acted in selfdefence. He, in the first place, courteously bid the Collingwood men ‘Good-night,’ but received an unseemly reply and was knocked down. Accused went into the witness box and swore that he was set upon by the Collingwood men and knocked down. He got up and tried to get away, but was rushed a second time, and in defence picked up a stone and threw it. He had been very roughly handled by the Collingwood men. After hearing the evidence of these witnesses the jury informed his Honor that they were satisfied accused had acted in self defence, and on his Honor’s direction returned a formal verdict of not guilty.47

Hyman was also a gifted runner, competing in Western Australia, South Australia and Victoria. In 1896 he won the Sheffield Handicap, South Australia’s premier professional athletic event.48 In 1904 he came third in the Stawell Gift, returning in 1905 and 1906. Hyman’s sporting interests also included the owning of racehorses such as Major Booth, which ran in the 1910 South Australian Derby.49 On Hyman’s enlistment in 1916 he was described by the Barrier Miner as: ‘a good patron of the turf, owning several fair horses, but none of them did much stake collecting.’50

At the time of the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, Oscar Hyman was a well-known racing identity and sportsman in South Australia with both family and business responsibilities. Although still fit, he was by then in his late thirties and was under no obligation to enlist. Like several other members of the Armoured Car Section, Hyman’s enlistment proved unusual. The ‘Sporting Gossip’ section of the Port Pirie Recorder reported: ‘The old Adelaide and Melbourne footballer, Mr. Oscar Hyman, paid £100 to become an Australian soldier. A little while ago two armoured motorcars were presented to the Victorian Military Authorities by a few young men, who, in addition to contributing the cost of the motors, also armed themselves. For his seat, as one of the detachment, Mr. Hyman paid £100. The cars have been taken over by the Military Authorities, and attached to the 22nd Infantry.’51

Hyman travelled from South Australia and enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 28 March 1916. He was briefly posted to the 22nd Depot Battalion on 3 April but joined the other members of the Armoured Car Section at the 24th Depot Battalion at Royal Park where he would have participated in the final construction work on the armoured cars. On June 20 he was appointed a motor transport driver and taken on strength by the Armoured Car Section, embarking for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna at Port Melbourne on the same day. Disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August. The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve with the British 11th and 12th Light Armour Car Batteries in operations against the Senussi tribesmen. Hyman was a member of the section when it was re-equipped and designated the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol on 8 December.

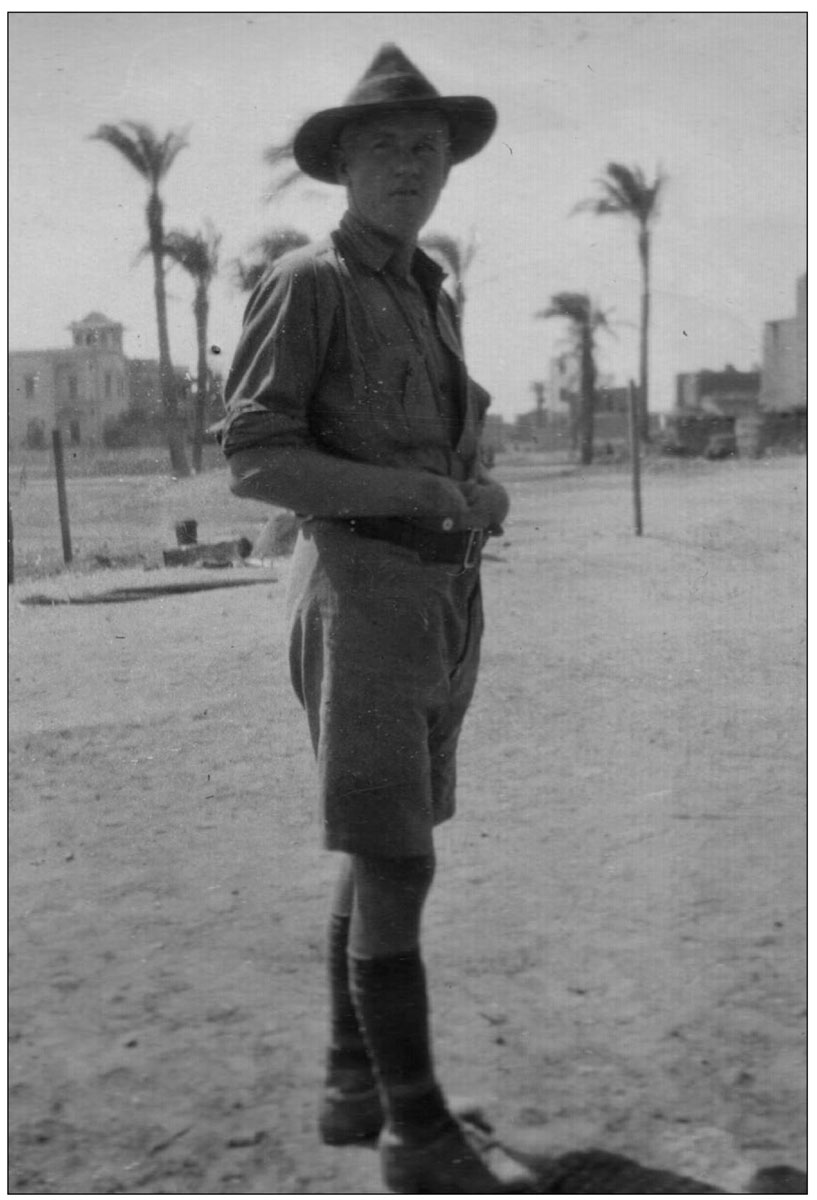

72. Driver Oscar Hyman’s studio portrait taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916. Hyman was an accomplished athlete and a wealthy hotelier by the time of his enlistment in March 1916 (AWM DACS0127).

Hyman recorded his first Christmas overseas in a letter published in the Adelaide Register:

Oscar Hyman, of the Australian Armoured Car Section in Egypt, writing to a friend in Adelaide, says: “I am penning these few lines in the hope that they will be published in the Register, just to give the public of South Australia an idea of how our little camp (consisting of small units necessary to keep the advanced base camp going) spent their Christmas Day in the desert.

We are located out in the wilderness, 500 miles from Cairo and 150 miles from the Nile, and, thanks to the generosity of Lieut. Cornwell and the ladies of Australia, we spent a most enjoyable and never-to-be-forgotten day. We were favoured with very fine weather, and a programme of sports arranged by a committee was successfully carried out. Prizes or the most part were donated by Mr. McDiarmid of the Y.M.C.A. A feature of the sports was the donkey race, and it caused endless amusement. The donkeys were specially brought from Kharga, 20 miles away, for the occasion. There was also a tug-of-war between different units (eight men a side), and our unit, the Australian Armoured Car section (now increased to 20 men, in order to take over light car patrol work and responsibility), after beating two other teams, were unlucky enough to run up against a better team in the final. We had one win to our credit, your humble servant succeeding in winning the 100 yards scratch race.

After a very interesting afternoon we left for our respective camps, ready to do justice to the good things in store. Our marquee was decorated with a few flags, and the table set for our Christmas dinner, with 27 of us stated at 6 p.m., Lieut. Cornwell in the chair. A start was made on the good things provided, the menu consisting of pea soup, roast turkey, baked potatoes, plum pudding, trifle, jelly, blancmange, and fruit, walnuts, almonds, raisins, and bonbons.

The liquid refreshments were bottled beer, whisky, and lemonade, so you can see we had a real Christmas dinner. A musical evening followed naturally and several toasts were honoured. The toast of the evening was ‘The Ladies’ Leagues of Australia’, the splendid work done by them in sending ‘billies’ and Christmas cheer of all description being freely commented on.

They can rest assured that their untiring efforts, accompanied by good wishes, are very much appreciated by the boys so for from home. The work of the women of Australia was an eye opener to those of the Tommy regiments attached to us (who participated), and the toast was followed by prolonged cheering. It was atop a great send off to our unit, who are getting ready to move off to patrol and explore a way to another oasis some 400 miles further into the desert. It will probably mean months and months of work shifting the Senussi tribes.”52

Hyman served with the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol in Egypt, Palestine and Syria until the end of the Great War, remaining with the unit for the entire campaign other than during brief periods of hospitalisation. He was promoted lance corporal on 8 March 1918. On 15 March 1919 Hyman was posted to the AIF Details Camp pending his return to Australia. He embarked on the HT Kaiser-i-Hind at Suez on 16 May and disembarked at Port Adelaide 14 June. Lance Corporal Hyman was discharged on 29 July and was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge for his service.53

Hyman returned to his business commitments and, in April 1922, opened a billiard saloon in Unley.54 In January 1926 he was appointed the handicapper for the Tattersalls Club.55 In this new position Hyman became both successful and well respected in racing circles. In 1930 he visited the UK as a representative for Tattersalls. He was later the senior handicapper for the South Australian Jockey Club and the Australian Racing Club. After a long and successful career he retired in June 1948. His retirement was reported in the Adelaide Chronicle:

Mr. Oscar Hyman announced at the weekend that he had resigned as handicapper to the SAJC and ARC. He was appointed in 1941. Mr. Hyman stated in his resignation to the two committees that ill health prevents him from continuing with his duties after the end of the racing season. ... Mr. Hyman, who is 70, is widely known in sporting circles and until he was appointed to his present position he was handicapper for Tattersalls Club for 16 years. He was a star footballer in his youth and played league standard in three States. He played with North, South, West Torrens and Sturt. He captained Sturt for two years and led the State team in the 1908 carnival. His last season was 1910. A returned soldier from the First World War, Mr. Hyman saw three years’ active service with a fighting unit in Egypt, Palestine and Asia Minor. At a meeting of the committee of the SAJC on Monday it was decided to place on record appreciation of Mr. Hyman’s services.56

Hyman died in Mitcham on 11 January 1955.

Walter Perrin Thompson was born in Kew, Victoria, in 1874, the son of Henry and Elizabeth Thompson. He married Fanny May White in 1904. The Thompsons had two daughters: Gwyneth, born in 1904 and Elizabeth, who arrived in 1911. The electoral rolls prior to the Great War recorded Thompson as an accountant or merchant residing in the Hawthorn-Kew area. His address on the outbreak of war was Berkely Street, Hawthorn. Thompson was part-owner of W.P. Thompson and Co Pty Ltd of Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. By the standards of the day it appeared to be a successful company; in November 1920 a business report in the Melbourne Argus stated that the firm was General Merchant, Saddlers and Ironmonger with capital of £75,000 issued in £1 shares.57

It is likely that Thompson was one of the motoring enthusiasts described by James. His age, wealth and social position would have made him a likely candidate for motorcar ownership in Edwardian Melbourne. One could also imagine his angst as he made the difficult decision between family and business management responsibilities, and his strong patriotic feelings.

Thompson chose the latter, joining the AIF on 25 March 1916 when Lieutenant James, the Officer Commanding the Motor Machine Gun Corps, gave him a letter stating that he was willing to accept Thompson into the Armoured Car Section. He was allotted to C Company, 22nd Deport Battalion, on 3 April and, while at Royal Park, assisted with the construction of the armoured cars. On 17 May he was promoted lance corporal. Once the armoured cars were accepted by the Defence Department and training had been completed, Thompson embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June. After disembarking at Port Tewfik, Egypt, the 1st Australian Armoured Car Section joined the Egyptian Expeditionary Force on 9 August.

The section soon entrained for southern Egypt to serve in operations against the Senussi tribesmen. During this period Lance Corporal Thompson was thrown from a patrol motorcar and injured his left knee. He was treated at a field ambulance and later evacuated to Cairo where he developed rheumatism. On 17 August 1917 he was transferred to the Australian Army Pay Corps at AIF Headquarters Middle East. However 1918 saw further admissions to the 14th Australian General Hospital where he was medically boarded as B1 on 13 January. On 1 March Thompson was promoted to extra regimental corporal, later reverting to lance corporal on embarkation for Australia. He boarded HMAT A15 Port Sydney at Suez on 19 May and disembarked in Port Melbourne on 4 July.

73. Studio portrait of Lance Corporal Walter Thompson taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916, just prior to his embarkation with the 1st Armoured Car Section (AWM DACS0125).

Lance Corporal Thompson was discharged as medically unfit for service on 14 August 1918. For his service he was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals, the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.58

Following discharge Walter Thompson returned to Berkely Street, Hawthorn, and resumed his business activities. During the 1920s and 1930s he wrote several extended letters to the Argus newspaper on Melbourne’s history. He died on 9 August 1934 and was buried in Kew Cemetery. When probate was granted on 30 May 1935 his estate was valued at £78,387-4, a considerable fortune in that era.59

Henry Lloyd Fitzmaurice Harkin, RVM

Henry Lloyd Fitzmaurice Harkin was born in Chiltern, Victoria, in 1897, the son of Dr Charles Harkin J.P. and Emily Harkin.

The Harkin family were early pioneers of Victoria’s north-east. Henry Harkin Junior was named after his paternal grandfather, Henry Charles Harkin, who was an early member of the Victorian Police at Wodonga and later rose to the rank of police sergeant. After leaving the police force he became a successful businessman and later a magistrate. In 1917 his death was widely reported in the newspapers of the area and he was described as Wodonga’s oldest citizen.

Charles Harkin attended Dublin University and qualified as a doctor. On his return he practised in Albury, NSW, and Chiltern in Victoria. Dr Harkin was an active citizen with an extensive list of achievements that included President of the Chiltern Rifle Club, Justice of the Peace, Shire Councillor, Shire President, director of several local gold mines and President of the Overseas Wine Marketing Board. In 1911, when gold mining declined in the district, Dr Harkin led a group of local businessmen in founding the Chiltern Vineyard Company in an attempt to establish new industries in the area. He was also the first owner of a motor vehicle in Chiltern—a Stanley Steamer.60

Henry Harkin Junior was educated at Melbourne Grammar School between 1912 and 1915 where he reached the rank of cadet sergeant in the Grammar cadets. By 1916 Harkin had served in the junior cadets for two years and the senior cadets for four. In March 1916 he was still a member of the 29th Battalion of the Senior Cadets. His nephew, Henry Harkin, in an interview in 2006, recalled that Henry lived for cars and that he was passionate about every aspect of motors and motoring. On enlistment in 1916 he stated that he was a motor mechanic by trade.61 In March 1916 he was given a letter by Lieutenant James which stated that he was ‘willing to enrol H. Harkin as a member of the armoured motor crew when enlisted.’62

Harkin enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 30 March 1916. At 18 years and seven months, he was to become the youngest member of the Armoured Car Section. Interestingly, his attestation paper was marked with the comment that he had defective vision and that he was only suitable for mechanical (motor) services and should wear spectacles. He was taken on strength by C Company, 22nd Depot Battalion, on 3 April but was posted to the 24th Depot Battalion on 12 April where he participated in the final stages of Lieutenant James’ project. On 20 June Harkin was posted to the 1st Armoured Car Section and, on the same day, embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne. Harkin remained with the Armoured Car Section and the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol until the end of hostilities. During that time his dossier remarkably records no illness or hospitalisations until he is diagnosed with malaria just prior to his return to Australia in March 1919.

74. Studio portrait of Driver Henry Harkin, the youngest recruit to the 1st Armoured Car Section, taken at Broadmeadows Camp in May 1916. He became Lieutenant Percy Cornwell’s driver in the Light Car Patrol (AWM DACS0130).

On 15 March 1919 he was posted to the AIF Details Camp pending his return to Australia. He embarked on the HT Dorset at Suez on 29 April, and disembarked in Fremantle, Western Australia, on 29 May due to influenza. Sufficiently recovered from his illness, he re-embarked on the HT Dorset, finally arriving in Port Melbourne on 11 June. Motor Transport Driver Harkin was discharged as medically unfit on 13 August. He was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges for his service.

On arrival in Australia, Harkin and Sergeant Creek joined the 1919 Royal Tour of His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales as drivers. For this service Harkin was awarded the Royal Victorian Medal on 1 January 1920. Harkin returned to Chiltern following the Royal Tour, his family recalling that he returned to the vineyard in very poor health and seemed unable to gain weight. A short while later he did not have the energy to walk from the vineyard back to the house. He was diagnosed with Juvenile Diabetes and died from this illness at ‘Kilara’ in Mentone on 18 January 1922.

In 2006, Henry Harkin donated his uncle’s effects to the Army Tank Museum. These included personal items Henry carried with him during his Army service, his Royal Victorian Medal and the personal keepsakes presented to him by His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales for the 1919 tour. There were also photos of the Armoured Car Section in Melbourne in 1916.

Leslie John Millar

Leslie John Millar was born in Melbourne on 12 September 1877, the son of Thomas and Helen Millar. At the time of his enlistment in 1916 his next of kin was his wife, Isabella Millar, of William Street, Melbourne. He listed his occupation as accountant and motorcar expert.

Millar’s military service began in 1900 when he enlisted in the 3rd Victorian Bushmen. On enlistment he stated that he was a boundary rider and resided at the Doutta Galla Hotel, Flemington, Victoria. Millar embarked on the SS Euryalus at Port Melbourne on 10 March 1900 and disembarked at Beira in Portuguese East Africa on 3 April. He served with the Rhodesian Field Force and was present at the siege of Elands River between 10 and 16 August 1900. He returned to Victoria aboard the SS Morayshire, disembarking in Port Melbourne on 5 June 1901. He was discharged on 8 August. Millar subsequently returned to South Africa where he served in the Imperial Military Railways.63

Following his return from South Africa, Millar settled in William Street, Melbourne, and became a commercial traveller, marrying Isabella Monteith in 1906. On the 1914 electoral roll his occupation was listed as eye specialist and he was residing at Dundas Place, Albert Park.

Millar was an early user of motorcars and, in November 1911, he learnt of the dangers of road use first hand:

Knocked Down by a motorcar. A motor accident occurred in Beaconsfield Parade yesterday afternoon, the victim being Ray Phelan, 7 years of age ... he was playing with several other lads in one of the rockeries, and, rushing on to the parade, was struck by a motor driven by Leslie Millar, of Dundas Place, Albert Park. The Car was travelling at not more than five miles an hour, and the boy appeared to run under the wheels. When picked up the boy was badly bruised on the face and the body. In company with Constable Hall, Mr. Millar drove the lad to the Homeopathic Hospital where he received attention from Dr. Gould. No bones were broken, and the case is not regarded as serious.64

Millar’s interest in motorcars also extended to the infant sport of motor racing. In 1913 he was manager of the Richmond Racecourse where Percy Cornwell raced his Mercedes.65

75. Corporal Leslie Millar, prior to embarking for overseas service with the 1st Armoured Car Section. Note the ribbons of the Queen’s and King’s South Africa medals on his uniform tunic that indicate his prior service (AWM DACS0123).

Millar enlisted in the CMF (Home Service) sometime after the outbreak of the Great War and served with the Australian Army Pay Corps. He transferred to the AIF on 3 April 1916 in Melbourne and was taken on strength by C Company, 22nd Depot Battalion, and promoted corporal. He was posted to the 24th Depot Battalion at Royal Park on 13 April. On 20 June he was appointed lance sergeant and quartermaster sergeant of the Armoured Car Section. Millar embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne on 20 June 1916. In April 1917 his health declined and a series of hospitalisations followed. On 19 September he was posted to the AIF Details Camp at Moascar. In the year that followed, Millar was repeatedly admitted to hospital for a wasting condition that affected his left leg and right knee. Eventually he was medically boarded and classified as unfit for further service. He embarked on the HMAT A18 Wiltshire at Suez on 30 August 1918 and disembarked in Port Melbourne on 4 October.

Lance Sergeant Millar was discharged as medically unfit on 29 May 1919. For his service in the South African and Great War he was entitled to the Queen’s South Africa Medal (Bars: Cape Colony, Transvaal, Rhodesia and South Africa 1901), the King’s South Africa Medal (Bar 1902), British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s and Silver War Badges.66

Following his discharge Millar resided at Alexandra Mansions in South Melbourne. The 1919 electoral roll lists his occupation as manager. Sometime in the late 1920s he relocated to Whitehorse Road, Balwyn, and returned to commercial travelling. Millar died at the Mont Park Hospital in Macleod on 21 November 1956 and was cremated at Springvale.

Gordon Alexander McKay

Gordon Alexander McKay was born in Brunswick, Victoria, on 7 January 1887, the son of Andrew and Christina McKay, and joined Havelock Tobacco Company in 1902 as an office lad. He married Annie Forbes in March 1913. At the time of his enlistment he was a clerk residing in Bruce Street, Preston.

McKay enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 1 July 1915. He was promoted corporal and taken on strength by Headquarters Company at Ascot Vale Camp on 12 July. On 27 November he was transferred to the invalid list due to chronic arthritis. His file contains a note that he could only be employed in Australia as a clerk, while other documents recommended discharge on medical grounds. After time spent at the Melbourne Hospital, McKay returned to the Ascot Vale Camp on 14 February 1916 and was promoted acting sergeant. On 25 April he was posted to D Company, 23rd Depot Battalion, at Royal Park only to be posted again on 18 May, this time to the 24th Depot Battalion, also at Royal Park. On this occasion he reverted to private at his own request.

On 20 June he was taken on strength by the Armoured Car Section as a motor transport driver and embarked for overseas service on HMAT A13 Katuna in Port Melbourne. McKay served with the Armoured Car Section and the 1st Australian Light Car Patrol until July 1917, with only a short period of detachment between 19 and 27 May 1917 to act as Lieutenant Cornwell’s batman with the survey party in the Sinai area.

76. Driver Gordon Alexander McKay, Armoured Car Section (DACS0238).

On 20 July 1917 McKay was posted to the AIF Canteens Service. He was promoted acting sergeant on 31 May 1918, extra regimental staff sergeant on 10 November and warrant officer Class I the following day. On 27 November McKay boarded the HT Harden Castle bound for Gallipoli where he was part of the occupation forces. He later returned to Egypt pending his return to Australia. He embarked on the HT Ulimaroa at Suez on 13 March 1919 and disembarked in Port Melbourne on 22 April. Warrant Officer Class I McKay was discharged as medically unfit on 13 June. He was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s and Silver War Badges for his service.67

Following discharge McKay returned briefly to Preston but soon relocated to Cowra, NSW, where he took up farming. He died on 25 April 1922 as a consequence of an accident. The Canowindra Star and Eugowra News reported:

Death at Cowra. The death occurred last week of Mr. Gordon Alexander McKay, one of the Victorian farmers who came to Cowra some years ago and took up lucerne land at Mr. C. N. Grieves’ property. Several months ago the late Mr. McKay had one of his knees seriously injured (through being run over by a wagon at Billimari) and blood poisoning set in and he died as stated at the early age of 35 years, at Nurse Matheson’s Private Hospital, despite the best medical attention and the most skilled nursing. He leaves a sorrowing widow and a young family.68

He was buried at Cowra the following day.

McKay’s two sons both served in the Second World War. Keith Ronald McKay enlisted in the AIF on 6 June 1940 and served as a lance corporal with the 2/8th Field Company. In May 1941 he was captured in Greece and remained a prisoner of war in Europe until 1945.69 Alan Murray McKay enlisted in the CMF on 15 August 1940 and served as a gunner with the 2nd Medium Regiment. He left the Army and enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) in September 1941, training as a wireless and radar mechanic. McKay served with the 79th Squadron in the Pacific before returning to Australia where he was posted to the 1st Operational Training Unit based at East Sale, Victoria. He was engaged in radar tests when he was killed in an air accident on 23 February 1945. The Lockheed Ventura twin-engine bomber in which he was flying crashed 12 miles east of Sale, the aircraft disintegrating on impact and killing all those on board.70

Norman Sinclair Bisset

Norman Sinclair Bisset was born in Sandhurst, Victoria, in 1887, the son of George and Malvena Bisset. Norman was educated at Golden Square and Sandhurst High School. He played lawn tennis for the Bendigo Lawn Tennis Club71 and was a member of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church.72 At the time of his enlistment in 1914 he was an accountant employed by the Bendigo Permanent Land and Building Society and resided in Wade Street, Golden Square.73

Bisset enlisted in the AIF in Bendigo on 15 November 1914. He was soon allocated to the 1st Reinforcements, 16th Battalion, with whom he embarked on HMAT A35 Berrima on 22 December in Port Melbourne.

After a period of training in Egypt he was detached to the Administrative Headquarters Staff, although this was not recorded in his military records. However he describes his experiences in Egypt in a letter published in the Bendigonian in March 1915:

Headquarters Base Details, Camp Abbassia, 15th February, 1915. As I have a few moments to spare, I will spend them with you. You will see by the heading I am now stationed on the headquarters staff and don’t I know it. It’s a case of getting a move on as early in the morning as possible, take as little time as is safe to your meals, and burn as much midnight oil as you can. We have no time we can really call our own. Our hours are “get through it”, and we have to go for it. I am the correspondence clerk, and have to register and file all letters that come in and go out. It is interesting in so much that I know what is going on in our sphere, but would rather be at some of the other work, getting experience in something that I am not used to. I have also other duties, for which I am responsible, and between the lot I get plenty of “hurry up”. I will now give you the details since my last letter. I was doing some clerical work a week ago with our company clerk, when I was told to report at the Orderly Room. I did so and was picked with nine others to go into the Headquarters in Cairo, and was told to report at 12.30. In the meantime I learned that we would likely be stuck in Cairo for good, and I didn’t fancy the experience, so I went to the Adjutant and asked if the change meant that I would not see any service, and he said, “practically, no.” I then asked if I could strike my name off the list. He asked me what I had been used to, when I told him he asked me to join his staff, which meant that we would always move with the troops. I agreed, so here I am. The offices are in a part of the barracks, which practically surround the camp, and I eat and sleep here. Compared with the rest of the troops we are fed like prize turkeys, so it works both ways. What do you think of this for a day’s menu? Yesterday we had four eggs each, bacon, coffee, bread and jam for breakfast; mutton, three vegetables, plumb duff and tea for dinner; bread and jam and pancakes for tea. How is that for active service living? We have two cooks between twelve of us. “Bowie” and V. Ryan came in from Mena yesterday, and looked me up, and we went into Cairo together. They are camped near the Pyramids. When going through the camp we ran into W. Dawe. He has been camping about six tents from me and I did not know he was here. I keep running up against fellows from Bendigo all the time. One day our telephone orderly said to me, “You will be missing the dances this year.” I looked at him and said. “What do you know about my dancing?” He said, “Oh, I often saw you at the Town Hall; my father is caretaker there.” He is a son of Mr. Green. I haven’t seen much of the sights yet, and goodness knows when I will. The best place about here is Heliopolis, half a mile from the camp, and I believe it is a magnificent town. It was originally built to be a rival to Monte Carlo, and money wasn’t considered; but it did not come off. The main building is now used as a military hospital. There is a Luna Park, lit up just like the St. Kilda one, scenic railway and all. The inhabitants are mostly English and French, and there are no slums or poor parts. Every residence, they say, is a model. Another place I must get to is the Dead City, near Cairo, and the Pyramids go without saying. Some of our chaps went there yesterday, and I saw a native make a bet of 5/- to run down the biggest from top to bottom in two minutes. He surprised them by doing it in a minute and a half. I have just heard that the rest of the Australians are on the water. All the reinforcements are being taken from Abbassia to make room for those who are coming, and soon it will be a new crowd altogether.74

While it was not recorded precisely when Bisset rejoined his battalion or arrived at Gallipoli, the Bendigonian reported his probable departure as mid-November 1914 and thus it is likely he reached Gallipoli sometime after August. At Gallipoli he developed a septic hand and was evacuated on 10 November to the 1st Australian General Hospital at Heliopolis. After a period of hospitalisation and convalescence Bisset returned to his unit on 5 February 1916.

On 19 March 1916 he embarked on HMAT A64 Demosthenes at Suez to be returned to Australia as an escort, disembarking at Port Melbourne on 19 April. His return home was reported in the Bendigo Advertiser on April 29: