HOME SERVICES AND PERMANENT MILITARY FORCES

The men who manned Grit during its service in Australia came from two distinct groups. The first crew, trained at the Tank Corps Training Depot at Bovington Camp under the leadership of Lieutenant Brown, were members of the AASC Motor Transport Service. The other ranks were qualified motor transport drivers. On arrival in Australia they were all discharged from the AIF and re-enlisted in the Special Unit Tank Crew (Home Service). When these men finally discharged from military service in late 1918 and 1919, the responsibility for crewing and maintaining Grit passed to soldiers of the PMF stationed at the Swan Island RAE Depot. These men were technicians who garrisoned the forts that guarded Port Phillip Bay.

Returned to Australia for duty with tank

The traditional image of the AIF during the Great War was of units formed either in Australia or abroad for service overseas. Once a unit was disbanded, its members were generally returned to Australia in piecemeal fashion for demobilisation. The tank personnel of 1918 are possibly a unique example of a unit formed abroad for service in Australia.

The nine men gathered at Bovington Camp in January and February of 1918 all had relevant mechanical experience, both in the AIF as qualified motor transport drivers and before, with pre-war occupations including garage manager, four motor mechanics, one mechanical engineer and two chauffeurs. In terms of AIF service, three members had enlisted as early as 1914 and the average length of service was 32 months. The shortest service was no fewer than 16 months.

This group of men all came from the major urban centres and reflected the primary religious divisions within Australian society of the period: 33% were Roman Catholic while the remaining members belonged to the major protestant faiths. The majority were born in eastern Australia with the other 22% born in the UK. All members could claim Anglo-Irish roots. It is also apparent that these men came from predominantly skilled working class origins. The average age of the crew was a mature 28 years with the oldest 35 and the youngest 26.

Norman Lovell Brown was born in Glenelg, South Australia, on 4 March 1883, the son of Israel and Emma Brown. He married Emma Monkhouse at Unley on 25 December 1902. By 1916 the couple had four children. At the time of his enlistment in the AIF, Brown was a garage manager residing in Rose Park.

Brown enlisted in Adelaide on 10 April 1916. His postings in Australia between April and October included: D Company, 2nd Depot Battalion, the Musketry School at Chatham, B Company Base Infantry, the 5th Reinforcements 50th Battalion and the NCO School. During this period Brown displayed leadership qualities and acted as corporal, sergeant and company sergeant major. On 16 September he applied for a commission which was granted on 7 October. Lieutenant Brown was posted to the 3rd Australian Army Mechanical Transport Company, AASC, on 16 October.

Lieutenant Brown embarked for overseas service on HMAT A34 Persic at Port Melbourne, Victoria, on 22 December 1916 and disembarked at Devonport, UK, on 3 March 1917. During this voyage an alarm was raised and Brown, rushing to the deck, suffered a head injury which caused concussion and saw him hospitalised aboard the Persic. Brown reported to the ASC Training Depot 6 March. On 31 March he was admitted to Delhi Hospital where a plate was inserted in his skull. He did not return to the training depot until 26 April. Lieutenant Brown embarked at Southampton and proceeded to Havre, France, on June 20 and joined the 5th Divisional Ammunition Sub Park, AASC. It was to be a short appointment. On 8 July he was posted to the 1st ANZAC Corps Supply Column.

The 1st ANZAC Corps Supply Column was engaged in support of the 1917 offensive around the Belgian city of Ypres. During this period Lieutenant Brown began to suffer pains in his head, caused chiefly by the gunfire. Despite this affliction, his Officer Commanding, Major Goddard, regarded Brown as a capable and efficient officer who performed the duties of Roads Officer particularly well. However Brown was medically boarded at Rouelles on 6 November and found to be unfit for general service for six months, but fit for home service. On 21 November, Lieutenant Brown was evacuated to the UK awaiting further appointment. The decision was made to return Brown to Australia and terminate his appointment due to his medical condition. At the same time, the Imperial government agreed to send a Mk. IV tank to Australia on public relations duties. An Australian crew was required, and it seemed logical that Brown, with his mechanical knowledge, should command the crew.

Lieutenant Brown reported to the Tank Corps School of Instruction at Bovington Camp, Dorset, for special duty on 27 January 1918 and was appointed officer in charge of tank personnel. On 12 May he embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine for Australia with eight Australian tank crew who were to maintain and demonstrate the Mk. IV on its tour of Australia. The Special Unit Tank Crew disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.

Lieutenant Brown’s service with the AIF was terminated on 15 August 1918. The following day he was appointed a captain in the Home Service as Officer Commanding the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he commanded the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia. In early 1919 he supervised the training of the PMF engineers from the Swan Island detachment who took over the running of Grit until its final placement at the Australian War Memorial. This appointment was terminated on 23 October 1919.

For his service in the AIF, Lieutenant Brown was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.109

Brown’s later life illustrates his very complex personality. In 1923 Emma Brown wrote to the Base Records Office requesting her husband’s medals as ‘he has not and will not claim for the same. He has left me, and I understand he is living with another woman ... My reason for this application is so that my young children may have them.’110 In 1924 Brown returned his service medals. His service file also contains a 1933 letter from a family member that suggests that Brown’s whereabouts were unknown to his family. In 1935 Brown visited the Australian War Memorial in Canberra where he claimed he was a major rather than a captain. By 1943 he had settled in Woollahra, NSW, and was working as an engineer.

Brown died suddenly at the Repatriation General Hospital in Concord, NSW, on 27 April 1949. His death notice in the Sydney Morning Herald added to Brown’s mystique: ‘Brown-Arroll Captain Norman April 27 (Suddenly), 3rd AAMTC and RNR at the Repatriation General Hospital Concord beloved husband of Edna, Thy will be done.’111 In 1950 a memorial notice appeared: ‘Arrol. In loving memory of my late husband, Captain. N.L. DSO and Bar, MC passed away April 27 1949, Love endureth forever and anon-yea even into Eternity. Inserted by his loving wife, Edna’.112 These notices revealed a new surname as well as decorations and service that are not supported by his service record. Sadly, correspondence would continue for some time between Edna and the Imperial War Graves Commission as she attempted to substantiate her late husband’s claim that he had been decorated at Cambrai.

Two of Brown’s sons would serve in the AIF in World War II: Private Norman John Brown, 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion, and Sergeant George Alfred Brown, 2/3rd Field Company.113

Richard John Dalton

Richard John Dalton was born in Essendon, Victoria, on 22 May 1891, the son of Martin and Mary Dalton. At the time of his enlistment in 1915, Dalton described his occupation as motor mechanic and driver, and his place of residence as Middle Park. Soon after enlistment he married Eileen Margret Houston of Punt Road, Windsor, Victoria.

Dalton’s driving skills came to the attention of the police in June 1914 according to court report found in the Port Melbourne Standard:

Richard Dalton, chauffeur, drove a motor car along a section of Bay street at the rate of 30 & 1/2 miles an hour on 30 June 1914 and was fined £2 at the local court on Thursday last for travelling at a speed dangerous to the public. He did not appear, but the case for the prosecution was borne out by Constables Fitzgerald and Burke. Defendant told the latter that he was hurrying in order that he might be in time for a departing mail boat and that he had no idea that he was going so fast.114

Dalton enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne on 12 July 1915. His enlistment, unlike many of his contemporaries, was classed as special; he enlisted as a motor transport driver for service with the AAMC, thus employing his civilian trade and associated skills. While in Australia, Dalton served with the AAMC Transport Section and the 1st Motor Transport Base Depot. During this time he was promoted lance corporal.

Lance Corporal Dalton embarked for overseas service on HMAT A19 Afric at Port Melbourne on 5 January 1916 as part of a group of reinforcement AAMC motor drivers. On arrival in Egypt on 13 February he was taken on strength by the Australian Motor Transport Service. Dalton served in Egypt until he embarked at Alexandria for Marseilles, France, on 16 June. He was then posted to the 4th Divisional Ammunition Sub Park, AASC, on 5 August as a motor transport driver. It is unclear when Dalton reverted from lance corporal to motor transport driver. He served in France and Flanders between June 1916 and August 1917 when he was granted leave to the UK. While on leave he was admitted to the 2nd Auxiliary Hospital. Following his discharge from hospital on 1 November, he was posted to the Australian Motor Transport Service, London. He remained in London until 27 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, Dalton embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May bound for Australia as a member of the tank personnel. Dalton disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.

On 12 August 1918 Dalton was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF Home Service ‘for service in Australia only’ as a member of the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he was part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia. He was discharged at his own request on 26 December 1918.115

In August 1922 Richard Dalton was one of four men who faced the Williamstown Magistrate’s Court for a breach of licensing laws. The publican, Mr Fyfe, pleaded guilty, arguing that, ‘they were returned soldiers, celebrating a great battle on the Rhine. They were just having a “sing-song” and playing on the piano. It was 3 o’clock when they left. Why the bar door was open when the police entered was that the licensee had gone to it for some cigarettes. There was no intention to commit a breach of the law.’ The ex-diggers asserted that they ‘were celebrating the last engagement of the war, the battle of Villers Bretonneux.’ The police prosecutor withdrew the charges under the circumstances.116

On 7 May 1940 Dalton enlisted in the CMF at Puckapunyal, Victoria. While serving with the Australian Army Canteens Service, Corporal Dalton died suddenly at Caulfield on 22 July 1942.117 He is buried at the Williamstown General Cemetery.

For his service in the AIF Corporal Dalton was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge. He was also entitled to the War and Australian Service Medals for his service in the Second World War.

Two of Dalton’s sons served in the Second World War: Sergeant Geoffrey Dalton, 2/23rd Battalion, and Able Seaman Thomas Houston Dalton, HMAS Lonsdale.118

Thomas Richard Fleming

Thomas Richard (Montague) Fleming was born in Paddington, Middlesex, UK, in March 1893, the son of John and Emma Fleming. In the 1911 census, Fleming was residing at Maynard Road, Rotherhithe, and was employed as a van boy. Sometime between 1911 and 1914 Fleming arrived in Sydney. At the time of his enlistment in 1914, his next of kin was his mother who resided at Shirland Road, Paddington, London. Fleming described his occupation as a chauffeur; his attestation papers also stated that he had served for two years in the Portsmouth Division of the Naval Brigade, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

Fleming enlisted in the AIF in Sydney on 22 August 1914 and was posted to the 2nd Infantry Battalion’s C Company. Private Fleming embarked for overseas service on HMAT A23 Suffolk in Sydney on 18 October and disembarked in Alexandria on 8 December. After training in Egypt, Fleming embarked on the Derfflinger at Alexandria on 5 April 1915 with the 2nd Battalion to join the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. On 25 April he landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Fleming was wounded in the foot in the week following the landing and was evacuated to Egypt. After convalescing at Mustapha Camp he rejoined his battalion on 8 June. This return proved short lived as, on 8 June, he was wounded a second time, hit by gunshot in the forearm. Fleming was evacuated to Egypt and admitted to the 1st Australian General Hospital and later the 2nd Auxiliary Convalescent Depot. On 25 April 1916 he embarked at Alexandria on the Ansonia for the UK, where he would remain for the rest of his overseas service. Having recovered from his wounds, Fleming was transferred to the Australian Motor Transport Service on 30 January 1917. In August he was mustered as a motor transport driver and medically reclassified as C1.

Fleming remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service at Chelsea until 27 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, Fleming embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia as a member of the tank personnel. He disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.119

On 12 August 1918 Fleming was discharged as medically unfit from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the Home Service ‘for service in Australia only’ as a member of the Special Unit Tank Crew. Promotion to staff sergeant would soon follow. Until his discharge he remained part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia.

For his service in the AIF, Staff Sergeant Fleming was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, British War and Victory Medals, and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges. In 1967 he claimed his Gallipoli Medallion.

Following discharge, Fleming lived in Adelaide and on the York Peninsula, South Australia, also spending some time in Queensland. He married Lorell Nobel in Maitland, South Australia, in April 1928. In 1967 he was living at Urania on the York Peninsula. Fleming died in Maitland on 21 November 1969 and is buried at the Maitland Cemetery.120

Frederick George Gifford was born in Exeter, South Australia, in 1889, the son of William and Ellen Gifford. At the time of his enlistment in 1916, his next of kin was his mother, Ellen Gifford, who resided in Glen Osmond Road, Glen Osmond. Gifford described his occupation as mechanical engineer; his attestation papers also stated that he had served in the Naval Reserve and had been rejected as unfit for service on a previous occasion.

Gifford enlisted in the AIF in Adelaide on 24 October 1916 and was posted to A Company of the 9th Depot Battalion. Private Gifford embarked for overseas service on HMAT A35 Berrima in Port Adelaide on 16 December with the 6th Reinforcements, 43rd Infantry Battalion, and disembarked at Devonport, UK, on 16 February 1917. In England, Gifford trained with the 2nd and 11th Training Battalions at Durrington. While at Durrington, Private Gifford was medically boarded and graded as C1. On 2 October he was transferred to the Australian Mechanical Transport Service, London, and mustered as a motorcyclist.

Gifford remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service in London until 26 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. This also involved a change of mustering and an appointment as an artificer. Having completed the course, Gifford embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia as a member of the tank personnel, disembarking in Sydney on 5 July.

On 12 August 1918 Gifford was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he was part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia. He was discharged on 26 December 1918. For his service in the AIF, Artificer Gifford was entitled to the British War Medal and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.121

Following his discharge, Gifford settled in Mount Gambier, South Australia, and was initially employed by the British Imperial Oil Company. His marriage to Ellen Maloney on 2 July 1922 at St Paul’s Catholic Church brought a significant change of fortune. Articles appeared in the Border Watch for the next 30 years portrayed a very successful life: he played cricket for the Standard Cricket and Kookaburras Clubs, was a patron of Gambier East Football Club, he became licensee of the Mount Gambier Hotel, promoted the local tourist industry, was a successful businessman, involved in the local aviation industry, and a supporter of many local charities and good causes. In the early 1940s the Giffords moved to Melbourne but retained a strong interest in the affairs of Mount Gambier; again the Border Watch contains numerous references to visits and correspondence from the Giffords. In March 1954 the Hotel was sold for £100,000.122 Gifford died in Albert Park, Victoria, in 1961.

Charles Robert Jackson

Charles Robert Jackson was born Newtown, Sydney, in 1890, the son of William and Meta Sophia Jackson. In 1914 his next of kin was his mother, Sophia Jackson, who resided at the Hospital, Great Victoria Street, Belfast, Ireland. On his enlistment Jackson stated that he was an engineer by occupation.

Jackson enlisted in the AIF in Sydney on 15 October 1914 and was posted to the 8th Company, AASC. This unit was also known as the 301st (Motor Transport) Company, 17th Divisional Ammunition. The 8th Company was to be one of the first motorised transport units in the Australian Army.123

Driver Jackson embarked for overseas service on HMAT A40 Ceramic in Port Melbourne on 22 November 1914 and disembarked at Avonmouth, Gloucestershire, UK, on 15 February 1915. In England, the 8th Company spent the spring of 1915 training and supporting the construction of the military camps being built on the Salisbury Plain. On 12 July Driver Jackson embarked on the SS Saba at Avonmouth and disembarked in France. The 8th Company and its sister company, the 1st Divisional Supply Column, became the first units of the AIF to arrive in France, almost a year before the infantry divisions. Jackson was transferred to the 23rd Ammunition Sub Park on 28 August. On 16 September 1916 he was posted to the Australian Motor Transport Service, London, thus ending his active service in France. In the UK Jackson was promoted corporal on 21 August 1917 and married Kathleen Alice Jackson at Winchester on 16 February 1918.

Jackson remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service at Chelsea until 26 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, Jackson embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia as a member of the tank personnel. He disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.

On 12 August 1918 Corporal Jackson was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he was part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia. He was discharged on December 26.

For his service in the AIF, Corporal Jackson was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, the British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.124

Following discharge, Jackson returned to Sydney, where the 1930 electoral roll shows him residing in Matilda Street, Bondi, and employed as a motor mechanic. His marriage to Kathleen was dissolved in February 1931 on the grounds of his wife’s desertion. In 1933 he married Annie Titterington and they eventually settled in Bellingen where he ran a garage. Jackson died at the Bellingen Hospital on 29 June 1953 and was buried in the Presbyterian section of the Bellingen Cemetery.125

Donald Bernard Lord

Donald Bernard Lord was born in Hanwell, Ealing, Middlesex, UK, in 1890, the son of James and Elizabeth Lord. Donald married Camille Dolly Cameron in 1912. At the time of his enlistment in 1914, his next of kin was his wife, Camille Lord, who resided in Millington Street, South Yarra, Victoria. Lord described his occupation as motor mechanic; his attestation papers also stated that he had served in the light horse in the CMF.

Lord and his elder brother Norman both enlisted in the AIF at the Albert Park Drill Hall on 17 September 1914 and were posted to the 9th Company, AASC, a unit also known as the 1st Divisional Supply Company. The 9th Company was to be one of the first motorised transport units in the Australian Army.126

Private Lord embarked for overseas service on HMAT A40 Ceramic in Port Melbourne on 22 November 1914 and disembarked at Avonmouth, UK, on 15 February 1915. He was promoted lance corporal on 21 December. In England, the 9th and its sister company, the 8th Company, spent the spring of 1915 training and supporting the construction of the military camps being built on Salisbury Plain. In June both units were warned for service in France with the British Expeditionary Force. On 3 June, Lord wrote to his wife, ‘tomorrow I am going before a medical board that will decide if I am to be invalided home. I presume they will decide, as I cannot walk yet. I don’t know what you will do with a cripple.’127 Lord did not proceed to France with his company. Between June 1915 and September 1916 there is no indication as to where he was hospitalised or located. On 16 September he was taken on strength by the Australian Motor Transport Service, Chelsea. His brother, Driver Norman Lord, would move to France with the 9th Company in July 1915 where he would serve until January 1917 when he was invalided from France after a serious accident. The brothers would be reunited in the Australian Motor Transport Service, Chelsea.128

Donald Lord remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service in Chelsea until 26 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, Lord embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia, disembarking in Sydney on 5 July.

On 12 August 1918 Lance Corporal Lord was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge on December 26 he was part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia.

For his service in the AIF, Lance Corporal Lord was entitled to the British War Medal and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.

Following his discharge it is unclear whether Lord was reunited with his wife and child. The correspondence contained in his service record contains several letters from Camille enquiring about Lord’s location or complaining that he had not maintained contact with her. By 1922 Lord had returned to the UK where he married Louisa Weldon at Melton Mowbray, Leicester. Lord died in Wells, Somerset, UK, in 1972.129

Michael George McFadden

Michael George McFadden was born in Sydney in 1891, the son of Michael and Kate McFadden. At the time of his enlistment in 1915 his next of kin was his father who resided in Latimer Road, Rose Bay, Sydney. He stated that he was a motor mechanic by trade.

McFadden enlisted in the AIF at Victoria Barracks, Sydney, on 22 November 1915. Prior to embarkation he served with Depot Battalion at Casula and the Mining Corps, Australian Engineers. Sapper McFadden embarked for overseas service with the 3rd Mining Company, boarding HMAT A38 Ulysses in Sydney on 20 February 1916. The Ulysses’ voyage was delayed at Fremantle when it ran aground on rocks while leaving Fremantle Harbour on 8 March.130 The Mining Corps was disembarked at Fremantle and transferred to Black Boy Camp outside Perth where it undertook a period of further training. On 2 April the Corps finally departed Western Australia on a repaired Ulysses for France via Egypt. On 5 May the miners disembarked in Marseilles. McFadden served with this unit until June when he was admitted to the 26th General Hospital. He was evacuated to England on 4 September and, after treatment at the Northamptonshire War Hospital and a period of leave, he returned to France on 13 February 1917. At the Australian General Base Depot at Etaples, McFadden was told that he would return to the UK to serve permanent base duty. After a period of hospitalisation in the UK, McFadden was transferred to the Australian Motor Transport Service on 19 May when he was mustered as a motor transport driver.131

Driver McFadden remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service at Chelsea until 27 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, McFadden embarked on the D8 Ruahine on 12 May bound for Australia. He disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.

In Melbourne, on 12 August 1918, McFadden was discharged from the AIF as medically unfit. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge on December 26 he was part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia.

For his service in the AIF, Driver McFadden was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.

Following discharge, McFadden married Annie Hales in Sydney in 1928 and resided in Rose Bay and Kogarah. He died in Kogarah in August 1928 from war-related causes and was buried at the Woronora Catholic Cemetery. The Army added a memorial plaque and scroll to his headstone in 1929.132

Arthur Reginald Rowland

Arthur Reginald Rowland was born at Maryland Station, Tenterfield, NSW, in 1885 the son of John Edward and Mary Anne Rowland. At the time of his enlistment in 1915, his next of kin was his mother who resided in Locke Street, Warwick, Queensland. Rowland gave his occupation as a dentist; his attestation papers also stated that he had served in the CMF with the 5th Bearer Company, AAMC, for two years.

Rowland enlisted in the AIF in Toowoomba on 2 January 1915 and was posted to the AAMC as a motor transport driver for the field ambulance. Driver Rowland embarked for overseas service on HMAT A7 Medic in Brisbane on 2 June 1915 with the AAMC drivers. He disembarked in Egypt and was taken on strength by the 1st Australian General Hospital in July 1915. On 1 October, Rowland was transferred to the Australian Motor Transport Service at Gamrab. On 10 June 1916 he embarked at Alexandria, disembarking in Marseilles on 16 October. He marched into the Base Motor Transport Depot at Rouen on 6 August and was posted on the same day to the 4th Divisional Ammunition Sub Park. On 29 March 1917 he was evacuated to the 15th Field Ambulance with a hernia. He was medically boarded at Etaples and classified as permanent base staff on 4 April. In England, Rowland passed through Army Headquarters and the Command Depots at Perham Downs and Weymouth. He was medically boarded and graded as C1 in August. Between 22 June and 20 September he served with the 66th Dental Unit at Perham Downs and was then transferred to the Australian Army Mechanical Transport Service, Chelsea, and mustered as a motor transport driver.133

Rowland remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service in Chelsea until 26 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. This also involved a change of mustering and an appointment as an artificer. Having completed this course, Rowland embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia, disembarking in Sydney on 5 July.

On 12 August 1918 Rowland was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he remained part of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia.

For his service in the AIF, Driver Rowland was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, the British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.

Following his discharge, he married Lena Mary Smith on 16 June 1919. They settled in Fisher Street, Chifton, on the Darling Downs and he returned to dentistry. In around 1930 the family moved to Melbourne. Between 1930 and 1950 the electoral rolls show Rowland’s occupation and residence as service station proprietor of Carlton, sales manager of Brighton, and fitter and garager of Hawthorn. He died in Kew, Victoria, on 8 October 1952 and was cremated at the Springvale Crematorium.134

Three of Rowland’s sons would serve in the Second World War. Private John Herbert Rowland served in the CMF while Corporals Reginald Laurence Rowland, Central Flying School, and William James Rowland, Radio Development and Installation Unit, served in the RAAF.135

Harry Stewart Swain

Harry Stewart Swain was born in Strafford, Essex, UK, on 28 July 1891, the son of Henry and Elizabeth Swain. At the time of his enlistment in 1914, Swain was residing in Brunswick Road, Parkville, Victoria, his next of kin his mother, Elizabeth Cox of Greenvale. Prior to embarkation, he married Elizabeth Ruth Prebble of Grant Street, Clifton Hill. Swain gave his occupation as a chauffeur; his attestation papers also stated that he had served in the Royal Navy for two years and had received a free discharge.

Swain enlisted in the AIF at Victoria Barracks, Melbourne, on 24 August 1914 and was posted to Headquarters Section, the Divisional Ammunition Column. The Divisional Ammunition Column was part of the Australian Artillery and was responsible for providing ammunition and reinforcements to artillery units. Gunner Swain embarked for overseas service on HMAT A9 Shropshire at Port Melbourne on 20 October, disembarking in Egypt in December. He remained in Egypt until 26 May 1915 when he moved to the Gallipoli Peninsula. On 6 September he was transferred to the 5th Battery of the 2nd Field Artillery Brigade. Swain developed enteric fever on 25 September and was evacuated to the 21st General Hospital in Alexandria. On 25 October he embarked on HMT Delta at Alexandria and, on 11 November, he was admitted to Graylingwell War Hospital, Chichester.

On 24 January 1916 Swain was transferred to the Australian Motor Transport Service, Chelsea, and mustered as a motor transport driver. He remained with the Australian Motor Transport Service in London until 26 January 1918 when he marched into the Tank Corps Depot at Bovington to attend a course. Having completed this course, Swain embarked on the HT D8 Ruahine on 12 May for Australia. He disembarked in Sydney on 5 July.136

On 12 August 1918 Swain was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. The following day he re-enlisted in the AIF ‘for service in Australia only’ in the Special Unit Tank Crew. Until his discharge he remained a member of the AASC crew that maintained and demonstrated Grit at various locations in eastern Australia. He served as a corporal until 10 December 1918 when he was discharged at his own request.

For his service in the AIF, Corporal Swain was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge. He died in Adelaide on 31 July 1957 and was buried at the Old Noarlunga Anglican Cemetery.137

Fortress Engineers of the PMF

Members of the PMF were confined to service in Australia and its territories. Under the Defence Act, members could not be forced to serve abroad. Those PMF soldiers who sought service abroad had to seek permission to enlist in the AIF; once granted they were discharged from the PMF and could then enlist in the AIF. Of the six members of Grit’s PMF crew, four followed this path. Second Corporal Marnie joined the AIF in September 1914 and served with the 1st and 5th Division Engineers at Gallipoli and in campaigns in France and Belgium, reaching the appointment of Regimental Sergeant Major before being commissioned. Sappers Hosking, Kubale and McDonald waited until 1916 before joining the AIF in field artillery and engineering units. Hosking and Kubale were both wounded while McDonald was awarded the Military Medal for bravery in the field. By the start of 1920 all had returned to Australia and rejoined the PMF as sappers. Sapper Cook and Artificer Nicholson remained in Australia during the Great War.

By the time these men began crewing Grit they had served an average of five years in the PMF and AIF, and all had significant experience in maintaining the mechanical and electrical devices in use within the fortress. The sappers came from a more diverse background than the AIF AASC motor transport drivers. They were evenly divided between rural and urban backgrounds, and between primary industry and trade occupations. Two were born in the UK, while the others were born in Victoria. All were protestant and all but one claimed Anglo-Saxon heritage. The average age was around 31, based on Artificer Nicholson’s very flexible 45 years!

Grit’s final crew comprised both experienced soldiers and technicians, qualities that kept the tank mobile until its transfer to the Australian War Museum in 1921.

Royal Australian Engineers Detachment,

Permanent Military Forces, 1919–1921

Sapper S.B. Cook

Corporal F.A. Hosking

Corporal A.H. Kubale

Sergeant W.K. Marnie

Corporal E. Mc. McDonald, MM

Artificer W.D. Nicholson

Stanley Brensley Cook

Stanley Brensley Cook was born in Williamstown, Victoria, on 29 March 1890, the son of Archibald and Mary Cook. At the time of his enlistment in 1912, Cook was an engine cleaner who resided in Bridge Street, Queenscliff, Victoria. He married Ruby Ellen Barnard in 1916.

Cook enlisted in the PMF in Queenscliff on 9 May 1912 and served with the 3rd Fortress Engineers Company, RAE, at the Swan Island Depot. He served in many of the Fortress Engineer garrisons within Australia in various technical trades such as engine driver and machinist. He was also posted to the Alexandra Battery in Hobart, Headquarters Fremantle Fixed Defences, Fort Queenscliff, the Engineers School at Wagga and the 3rd Australian Engineer Stores Base Depot.138

His skills as an engine driver and machinist would have served Cook well in the aftermath of World War I when he joined the crew of the Mk. IV tank Grit as a temporary corporal and while stationed at the Swan Island Depot. He was promoted corporal in 1920 and sergeant in 1922. During his posting to the Fixed Defences in Hobart in 1932 he was awarded the Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. He was promoted staff sergeant on 3 March 1936, temporary warrant officer Class II on 14 April 1940 and temporary warrant officer Class I on 20 January 1942. Cook’s posting to the Headquarters Fortress Engineers at Fort Queenscliff as Regimental Sergeant Major on 9 February 1942, almost 30 years after joining the same unit as a recruit, represents a significant achievement and milestone for any regular soldier. He was discharged at the age of 60 on 29 March 1950 after completing almost 38 years of service.

Tragedy would affect the Cook family while in Tasmania in May 1931 when Cook’s wife Ruby disappeared from her Sandy Bay home while Cook was absent on military duties. Her body was recovered several days later at Bull Bay after an extensive search. The Coroner handed down an open finding and Cook was widowed with six children.139 He would marry his second wife, Florence, in September 1933.

For his service, Cook was entitled to the War, Australian Service, Long Service and Good Conduct and the Meritorious Service Medal. He died in Heidelberg, Victoria, on 29 May 1974 and is buried at the Queenscliff Cemetery.

Frederick Alexander Hosking

Frederick Alexander Hosking was born in Flemington, Victoria, on 22 January 1890, the son of Richard and Helen Hosking. He married Francis Glover in 1916. At the time of his enlistment in the AIF in 1916, Hosking was a permanent soldier who resided at Swan Bay, Queenscliff, Victoria. His next of kin was his wife, Francis Hosking, of Richardson Street, Essendon.

Hosking enlisted in the CMF sometime in 1908 and served with the 38th Fortress Engineers in South Melbourne. In mid-1914 he enlisted in the PMF and served as a corporal with the RAE on Swan Island. In May 1916 he was granted permission to enlist in the AIF, joining on 8 May in Melbourne and was posted to the 10th Field Company. He was promoted to second corporal on 25 May and embarked for overseas service on HMAT A54 Runic in Port Melbourne on 20 June, disembarking at Plymouth, UK, on 10 August. Hosking was detached to the Engineers Training Depot at Christchurch on 7 November and promoted to temporary corporal. On 4 December he reverted to second corporal and proceeded to France where he rejoined the 10th Field Company on 19 December.

During 1917, apart from brief periods of hospitalisation and convalescence, Hosking would serve with the 10th Field Company in France and Flanders until 5 October when he was wounded in action. He suffered a gunshot wound to the left arm that caused a compound fracture. He was initially treated at the 10th Casualty Clearing Station and the 6th General Hospital in France. On 14 October he was evacuated to the UK and admitted to the Southern General Hospital, Birmingham, and later the 1st Australian Auxiliary Hospital. Following convalescence and leave, Second Corporal Hosking embarked on the Durham Castle on 10 March 1918 for South Africa. Hosking’s voyage to Australia would continue when he boarded the Orontes on 19 April, disembarking in Melbourne on 10 May. On 17 June Hosking was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne, deemed medically unfit.

For his service in the AIF, Hosking was entitled to the British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.140

In 1918 Hosking returned to the RAE’s Swan Island detachment. During his service at the Swan Island Depot, he was a member of the RAE crew that manned the Mk. IV tank Grit. Later he transferred from the PMF to the newly raised Australian Air Force. Hosking’s death was reported in the Melbourne Argus of 7 October 1925:

Fall From Motor Lorry. Inquiry Into Airman’s Death. A fall from the top of a motor lorry, which resulted in the death of Frederick Alexander Hosking aged 36 years, an aircraftsman at Point Cook, was inquired into by the city coroner (Mr. D. Berryman, P.M.) at the morgue on Tuesday. Charles Seymour Vaughan an aircraftsman motor driver at Point Cook, said; “On the afternoon of September 22, I was one of a squad which included Hosking which was detailed to load some heavy rolls of canvas onto a motor wagon in No. 11 hangar. To lift the canvas we had to fix a block and tackle to a beam on the roof of the hangar and to reach the beam Hosking stood on the roof of the lorry just over the tailboard. I was standing on the floor of the lorry. I said to him ‘look out, I am going to jump down,’ and caught hold of the rope from the block and jumped to the ground. As soon as the whole weight was taken on the rope it broke, and I fell to the ground at the same time causing Hosking who had been steadying himself by holding the rope to fall. In falling he struck his head on the tailboard and was made unconscious.” He was taken to the Caulfield Military Hospital suffering from a fractured skull and died on September 28. The coroner found that the fall was accidentally caused.141

Albert Henry Kubale

(Heinrich Albert Kubale)

Heinrich Albert Kubale was born in Natimuk, Victoria, on 2 May 1889, the son of Johann and Emma Kubale. Prior to joining the Army, Kubale worked at his uncle’s foundry at Natimuk.

Kubale enlisted in the PMF sometime in 1911 and, by 1915, he had been appointed a second corporal at the Swan Island Depot. On 6 November he enlisted in the AIF in Melbourne and was posted to the 2nd Divisional Ammunition Column where he worked as a wheeler. On enlistment, Kubale anglicised his name to Albert Henry Kubale.

Gunner Kubale embarked for overseas service on HMAT A39 Port Macquarie in Port Melbourne on 16 November with the 2nd Divisional Ammunition Column and disembarked at Suez on 13 December. He was posted initially to the 105th Howitzer Battery of the 22nd Howitzer Brigade on 10 March 1916. He embarked at Alexandria on 18 March and disembarked in Marseilles on 22 March. On 13 May Kubale was posted to the 5th Field Artillery Brigade where he remained until 13 May 1917 when he suffered gunshot wounds to the right elbow and foot. He was evacuated to the 8th Field Ambulance and 2nd Stationary Hospital. Kubale was further evacuated to the UK on the HMHS St Patrick on 5 June. After treatment and convalescence at the Norfolk War and 1st Australian Auxiliary Hospitals, he was medically classified as unfit for further overseas service.

Gunner Kubale embarked on the Suevic on 27 September 1917 bound for Australia and disembarked in Melbourne on 18 November. On 31 December he was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne, having been deemed medically unfit. He was initially awarded a pension of 45/- per fortnight for his war wounds. For his service in the AIF he was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, Military British War and Victory Medals and the Silver War and Returned Soldier’s Badges.142

Kubale returned to the RAE’s Swan Island detachment in 1918. During his service at the Swan Island Depot he was a member of the RAE crew that manned the Mk. IV tank Grit.

Kubale married Ethel Dandel at St Andrew’s Church, Queenscliff, on 16 March 1918 and, after his discharge from the Army, resided in Masters Street, Caulfield. He would later work for the Post Master General’s Department. Kubale died suddenly on 22 November 1953 and was cremated at the Necropolis, Springvale.143

Kubale’s son, Ronald James Kubale, served as a corporal with the 4th Aircraft Depot, RAAF, during the Second World War.144

William Kermack Marnie

William Kermack Marnie was born at Kerriemuir, Forfar, Angus, Scotland, on 29 July 1888, the son of David and Margaret Marnie. He was educated at the Dundee Technical College and completed an apprenticeship as a mechanical engineer in Scotland. Prior to arriving in Australia he had spent time in Waikato, New Zealand, working as an electrical and mechanical engineer. At the time of his enlistment, Marnie was a mechanical engineer and his next of kin was his father, David Marnie, of Myrtle Cottage, Kerriemuir, Scotland.

Marnie enlisted in the PMF on 18 May 1912 and served with the RAE at Swan Island, which was part of the Port Phillip Defences. By 1914 he had been promoted to second corporal. In August 1914 he was granted permission to enlist in the AIF. On 1 September he enlisted in Melbourne and was posted to No. 1 Section, 2nd Field Company. He was still in Melbourne when he was promoted second corporal on 24 September. Marnie embarked for overseas service on HMAT A3 Orvieto in Port Melbourne on 21 October, disembarking in Egypt in November. After training in Egypt, the 2nd Field Company embarked for service with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force on 5 April 1915 and landed at Gallipoli on 25 April. On 15 May Marnie was promoted corporal; he would remain at Gallipoli until the evacuation in December. He disembarked from the HT Caledonian in Alexandria on 27 December.

On its return to Egypt in 1916, the AIF was reorganised as reinforcements were absorbed and new formations raised. Marnie was transferred to the 8th Field Company at Tel el Kebir and promoted sergeant on 10 January 1916; an appointment as acting company sergeant major followed on 13 March and promotion to warrant officer Class II on 19 April. The 8th Field Company embarked on the Manitou in Alexandria on 17 June and disembarked in Marseilles on 25 June. Marnie served with the 8th Field Company until 29 September when he was temporally attached to the Commander Royal Engineers ‘Frank’s Force’. On 11 October he was promoted warrant officer Class I and posted to Headquarters 5th Division Engineers as the Regimental Sergeant Major on 23 October. RSM Marnie remained in this appointment in France and Flanders until 8 August 1917 when he reported to the Royal Engineers Training School at Newark in the UK. After successfully completing his course, he was appointed as a second lieutenant on 17 November. He returned to France on 19 December and rejoined the 5th Division Engineers on 26 December. He was posted to the 15th Field Company Engineers on 30 December. On 31 January 1918 Marnie was promoted lieutenant. On 16 December he returned to the UK for 1914 leave and return to Australia.

Lieutenant Marnie embarked on the City of Exeter on 15 January 1919 for Australia and disembarked in Melbourne on 2 March. On 1 May Marnie’s appointment in the AIF was terminated in Melbourne. For his service in the AIF, Lieutenant Marnie was entitled to the 1914–15 Star, Military British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge. In 1969, while residing in Chatswood, NSW, Marnie applied for the Gallipoli Medallion.145

Marnie returned to the RAE’s Swan Island detachment in May 1919. On return to the PMF, Marnie reverted to non-commissioned rank. During his service at the Swan Island Depot he was a member of the RAE crew that manned the Mk. IV tank Grit. By 1922 he had been promoted to warrant officer Class II. During his service in the PMF he served in the RAE Works Section which was responsible for the construction and maintenance of Army camps and fortifications. In 1932 Warrant Officer Class I and Honorary Lieutenant Marnie was detached from the 2nd Military District Base, where he held the position of works foreman, and assigned to the Darwin detachment. Marnie boarded HMAS Australia in Sydney on 24 August bound for Darwin, arriving on 6 September. On arrival in Darwin, Marnie was appointed Assistant Director of Works for the construction of the East Point Battery gun positions and magazines. On 13 October 1933 Marnie boarded the SS Marella and returned to Sydney.146

January 1939 saw Marnie promoted to quartermaster and honorary lieutenant with the Headquarters Eastern Command Directorate of Works. In February 1939 Lieutenant Marnie visited Port Moresby and the Mandated Territories to view the establishment of fixed defences and battery positions.147 Promotion to captain followed in July 1939 and temporary major in September 1941. This promotion was confirmed in September 1942 and Marnie transferred to the second AIF on 12 April 1943. During the Second World War he served in a variety of RAE Works units within Eastern Command. He would attain the rank of major and retire on 7 April 1949 as an honorary lieutenant colonel after almost 38 years of service in the Australian Army.148 Marnie was awarded the War, Australian Service, the Long Service and Good Conduct, and Meritorious Service Medals and the Australian Service Badge for his career in the PMF.

Marnie married Emily Gertrude Muir in Victoria in 1919. While he initially settled in Francis Street, Ascot Vale, he relocated to NSW sometime prior to 1930 when the Australian Electoral Roll recorded that the Marnies resided in Snape Street, Kingsford. At this point Marnie described his occupation as a clerk of works. He died in 1971 in Wahroonga, NSW.149

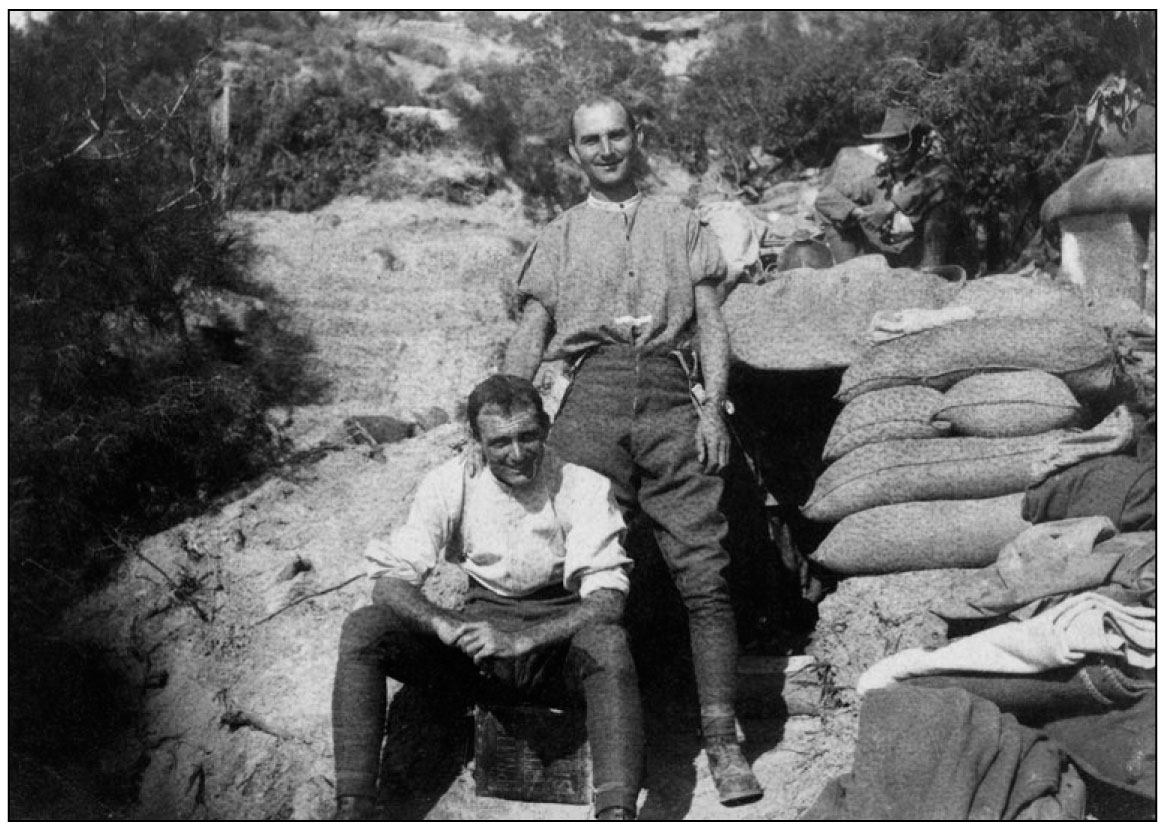

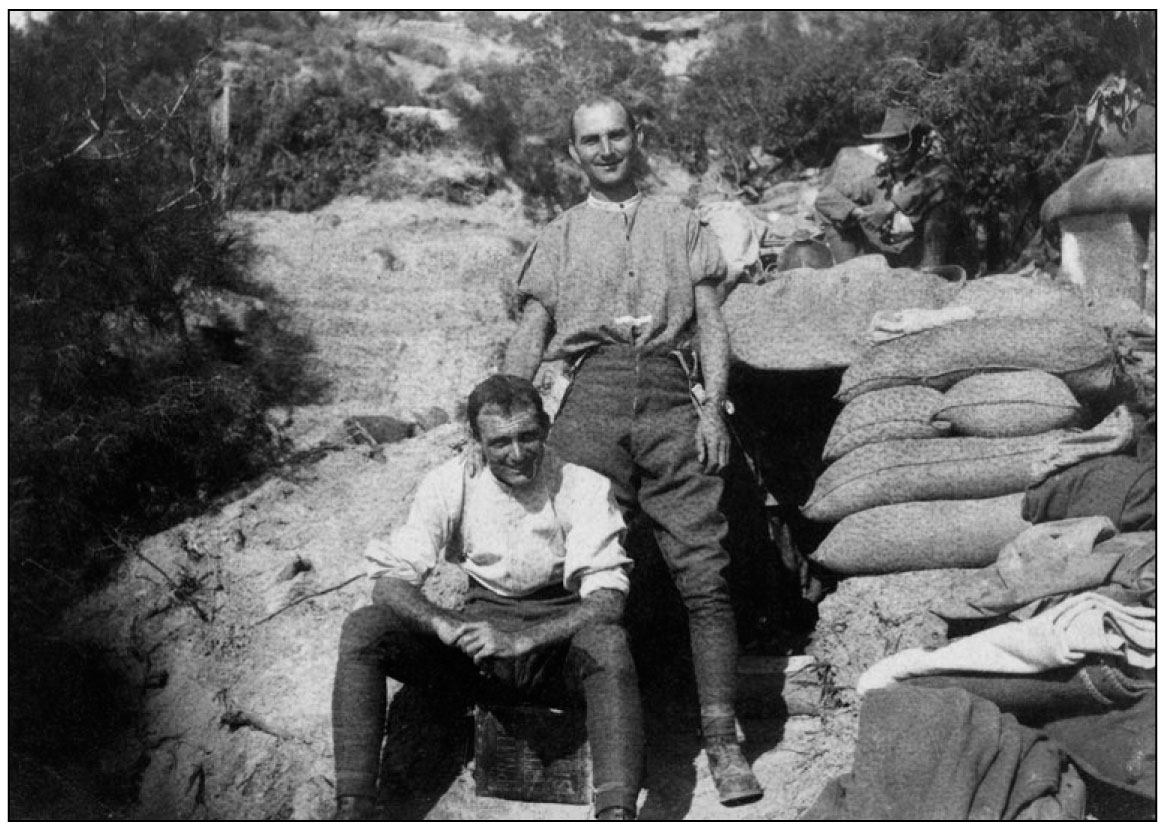

24. Sappers William Kermack Marnie (left) and Arthur James Crampton, both of 2nd Field Company Engineers, outside their dugout at Anzac Cove (P04173.010).

Ewen McColl McDonald, MM

Ewen McColl McDonald was born in Queenscliff, Victoria, on 18 September 1891, the son of Philip and Emily McDonald. Ewen McDonald enlisted in the PMF sometime in 1915 and served with the RAE at Swan Island, which was part of the Port Phillip defences. At the time of his enlistment in 1915, McDonald was a farmer who resided at Dunrobin in Swan Bay, Queenscliff, and his next of kin was his father, Phillip McDonald.

In mid-1916 Ewen was granted permission to enlist in the AIF. On 8 May he enlisted in Melbourne and was posted to the 4th Section, 10th Field Company Engineers. Prior to embarkation he married Hilda Ferguson of Ascot Terrace, Moonee Ponds, on 25 May 1916.150

Sapper McDonald embarked for overseas service on HMAT A54 Runic in Port Melbourne on 20 June with the 10th Field Company Engineers and disembarked in Plymouth, UK, on 10 August. While in training in England, McDonald was promoted lance corporal and proceeded to France on 23 November. He served with the 10th Field Company until November 1918 with only brief periods of leave and hospitalisation away from his unit. He was promoted second corporal on 31 March 1918 and corporal on 19 April. McDonald returned briefly to France between 29 January and 14 February 1919. On his return to the UK he was posted to the Australian Mechanical Transport Service, Chelsea, for duty with AIF Headquarters.151

In the ‘Australians on Service’ column of the Argus of 5 February 1918, a notice reported that:

Corporal Ewen McColl McDonald, the third youngest son of Mr and Mrs Philip McDonald, Dunrobin, Swan Bay, Queenscliff, [was] awarded the Military Medal for conspicuous bravery at the battle of Passchendaele. Corporal McDonald left Australia 18 months ago. Before enlisting he was a member of the Royal Australian Engineers, Swan Island. A younger brother, Sergeant Philip McDonald is serving with the Imperial Camel Corps in Palestine.152

On 3 September Corporal McDonald embarked on the Barambah for Australia and disembarked in Melbourne on 25 October 1919. On 17 January 1920 he was discharged from the AIF in Melbourne. For his service in the AIF, Corporal McDonald was entitled to the Military British War and Victory Medals and the Returned Soldier’s Badge.

McDonald returned to the PMF and the RAE’s Swan Island detachment in 1920. During his service at the Swan Island Depot he was a member of the RAE crew that manned the Mk. IV tank Grit. On 31 March 1921 Corporal McDonald transferred from the PMF to the newly raised Australian Air Force. He would attain the rank of flight lieutenant and retire on 30 June 1950 after almost 35 years of service in the AMF and RAAF.153 McDonald initially retired to Moonee Ponds and later Eildon, Victoria. He died on 16 August 1969 and was buried in the Eildon Cemetery.

McDonald’s son, Douglas Ewen McDonald, served as a corporal with the 7th Operational Training Unit, RAAF, during the Second World War.154

William Davidson Nicholson was born at Byker, Newcastle upon Tyne, Northumberland, UK, on 14 April 1874, the son of Benjamin and Agness Nicholson.155 The 1891 census records that the 16-year-old William was an apprentice in a sawmill in Northumberland. In early 1895 he married Charlotte Grieves at Horton, Tynemouth, and in 1911 the Nicholson family resided in Shields Road, Walker Gate, Newcastle upon Tyne. By this time the family had seven children. Sometime after Charlotte’s death in 1911, William migrated to Australia and, by 1914, he appears on the electoral roll at a North Geelong address.156 On enlistment in 1918, Nicholson was a bricklayer, his next of kin his son Corporal William G. Nicholson of the 12th Royal Lancers, Curragh Barracks, Ireland.

Nicholson enlisted in the PMF in Melbourne on 30 August 1918 and was allocated to the RAE. His postings included Fort Queenscliff, Swan Island and the Broadmeadows Camp. During his service at the Swan Island Depot he was a member of the RAE crew that manned the Mk. IV tank Grit. On 29 September 1924 he was transferred to the RAE Works Section as an artisan and appointed caretaker of the Broadmeadows Camp. He was appointed an artificer on 1 July 1920 and promoted sergeant on 7 October 1924.

Sergeant Nicholson died of injuries received on 31 December 1924, the Melbourne Argus reporting his death on 2 January 1925:

MYSTERIOUS DEATH. Camp Caretaker’s Injury. Returning to his home at the Broadmeadows military camp on Wednesday night Sergeant William Davidson Nicholson, widower, aged 51 years who was employed at the camp as caretaker suddenly became ill. When a doctor was summoned he found that Nicholson was dead. The body was removed to the morgue where a post mortem examination was made yesterday. The examination disclosed that Nicholson had died from haemorrhage of the stomach, caused probably by an injury. The matter has been reported to the detective office and Detective-sergeants M. Davey and A. McKerral are making efforts to trace Nicholson’s movements on Wednesday.157

The inquest into Nicholson’s death was held on 20 January and was covered by the Argus:

Caretaker’s Death. Owing to the absence of several important witnesses, Detective McKerral, who appeared to assist coroner (Mr. D. Berriman, P M), applied for the adjournment of the inquest which was commenced at the morgue yesterday concerning the death of William Davidson Nicholson, aged 51 years, a caretaker employed at the Broadmeadows Military camp. Richard Hodges, of Edward street North Geelong, said: “On December 31 I was on holidays at Broadmeadows camp. About half past 9 o’clock, with Nicholson and a man named Williams, I went in hotel at Campbellfield. There I left my companions, and later, when I got back to the camp, found that Nicholson had preceded me. He was quite sober. At half past 3 o’clock Nicholson went away by himself and it not until half past 6 o’clock that I saw him again. He was returning to the camp in a spring cart, and lying in the arms of Williams, who was driving. I said to Williams, ‘What is the matter with Bill (meaning Nicholson)?’ Williams replied, ‘I think he has taken a fit.’ Finding him unconscious I telephoned for Dr. Deane of Essendon, who said on arrival that Nicholson was dead.” Francis Kesson, Nicholson’s daughter, of Barkly Street East Brunswick said: “On November 23 my father told me that he had been asked to bring a lorry driver named Giles from Melbourne to the camp. About 6 o’clock he came to the gate of his quarters and called out. I went and saw my father with Giles, leaning for support against the fence My father’s face was covered with blood, and one of his eves was blackened. He said that the lorry driver Giles had knocked him down and put the boot into him as he was descending from the jinker. Dr. Deane attended later and directed my attention to a lump on my father’s side, which it was said had been caused by a kick. On the following Tuesday, though the doctor indicated that haemorrhage had set in, he said that if my father kept quiet he would probably be all right.”

Dr. Brett, Government pathologist, who conducted a post mortem examination of the body, said that death was due to internal haemorrhage. Detective McKerral: “Assuming that Nicholson had received a severe kick on November 23 and that the injured part had been tender for about 14 days afterwards, could you say that the injuries found were consistent with the injuries he had received?”

Dr. Brett: “Not Directly. A man who could exist for so long with such a haemorrhage going on in the stomach would be abnormal.”

Senior Detective Davey said: “Though Detective McKerral and myself have made inquires in connection with Nicholson’s death we have been unable to obtain and evidence of his having sustained any recent injuries.” The inquest was adjourned to a date to be fixed.158