“When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it; when you cannot express it in numbers your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind . . “

Lord William Thomson Kelvin

In a recent visit to a global manufacturing company, I learned that the company had been growing rapidly through acquisitions and began having difficulty retaining talent in Asia. When I asked several senior executives about the causes of the problem, I was told that no one knew for sure. The only metrics of any interest for the senior team members of this company were financial ones. They literally did not know the headcount.

In spite of the defection of highpotential leaders to competitors, a spike in turnover at all levels, increased customer losses, and plummeting profit margins, executives in the company had few mechanisms for understanding why. There were no leading indicators and few good lagging ones in areas such as talent, customers, or suppliers. The organization was at high risk and now had to take drastic action, investing scarce cash and leadership resources to fly around the globe simply to try to discover the root causes for a myriad of problems in diverse markets within the Asian region.

What they lacked was a good talent intelligence system. We are finding that the best-run organizations use strategic talent information to competitive advantage. Many companies have done this for years regarding their brand, customers, or quality. Why should talent be any different? A strategic talent measurement system connects talent to the overall business strategy and its key differentiators in the marketplace. An effective system would include both leading and lagging indicators of overall talent effectiveness and health. Furthermore, the tactical talent measures used by departments and functions, such as recruiting stats, training metrics, and early separations, should be aligned with the talent strategy and scorecard. I will describe each of these in greater detail in the sections that follow.

The Big 4

In the surveys the Metrus Institute has conducted in recent years, we have often found four primary drivers of organizational performance on the minds of CEOs: revenue generation, risk mitigation, agility, and innovation. Depending on your organization’s mission, market position, and life stage, the importance of each of these “Big 4” factors is likely to be different. Whatever their configuration, these four performance factors should be represented on the organization’s overall scorecard. Obviously, talent is a major force behind all four of these. Consequently, a talent scorecard — the critical measures for monitoring the execution of the talent strategy — should be connected to the Big 4, or whatever subset is relevant to your organization. And because People Equity is a surrogate for talent optimization, ACE should be a primary strategic indicator that connects to revenue and profitability, innovation, agility, and risk mitigation.

While revenue, agility, and innovation have been talked about a good deal in the past decade, the less discussed topic of managing and mitigating organizational risk is a growing one today — one which surfaced time and again in recent interviews that my colleagues and I conducted. The point was underscored at a 2010 forum of leaders hosted by the SHRM Foundation at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, where talent risk was one of the top three future human capital issues identified.

A talent scorecard should capture high-level strategic talent risks that concern leaders, board directors, or other external stakeholders, such as shareholders and regulators. Talent-driven factors often include the ability to innovate faster than competitors, to find the “right” talent, and to effectively adapt today’s talent to tomorrow’s challenges.

The Importance of Measurement

As we have discussed, People Equity is an effective surrogate for the degree to which talent is being optimized, albeit not a perfect one.1 If we can obtain effective measures of the talent strategy, including People Equity and its three components, such information will provide a window into how well talent is being optimized. While the last chapter focused on how to measure People Equity (ACE), this chapter will discuss how ACE and other talent drivers and outcomes can be positioned in the overall talent and business strategies.

Keep in mind that measuring ACE per se provides less insight than measuring how ACE is related to business results — and what drives high versus low ACE. By including these additional elements we will have a much clearer window on such issues as the following:

These are just a few of the potentialities that a company can uncover if it obtains good measures of its talent strategy, the levels of ACE, and the drivers of ACE.

The Talent Optimization Scorecard

A talent optimization scorecard is the set of indicators organizational leaders use to ensure that the talent strategy is executed effectively, that talent operates at peak levels, and that the talent reservoir remains strong for the future. A company such as De Beers, a Dutch diamond company, uses talent scorecards to track a variety of talent issues, ranging from training to leader development.2

The starting point for developing such a scorecard is identifying what aspects of the talent strategy are vital to the success of the organization’s business strategy and then putting in place measures to secure effective implementation.

The Talent Strategy Map

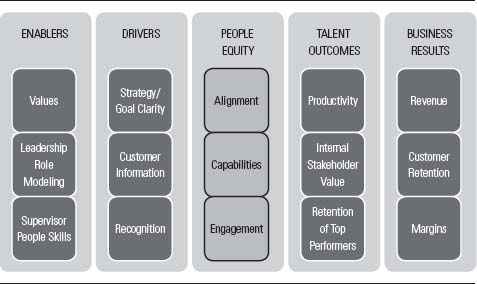

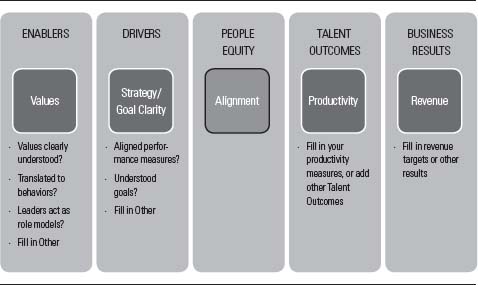

I begin the discussion of the scorecard with a map (see Figure 8.1) because a picture is one of the best ways to convey a leadership’s thinking about talent. A map not only elucidates what is relevant to measure, but by illustrating the assumed causal links between outcomes and drivers, it can also communicate “why” the items included on it are important to measure. The map in Figure 8.1 includes the three components of People Equity — Alignment, Capabilities, and Engagement — in the center since they represent the heart of talent optimization. To the right are the immediate expected outcomes of high levels of ACE, such as retention of top performers, high internal service performance, and productivity. These people outcomes, in turn, are expected to produce specific beneficial results for the business that are listed on the far right, such as improvements in revenue, margins, and customer retention.

Figure 8.1 A Talent Strategy Map

The map represents a picture of how one organization thought it could best optimize its talent. To the left of the ACE column are the unique drivers and enablers of ACE for this particular organization. While drivers and enablers are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7, “drivers” refers to factors that directly influence a single ACE dimension. For example, in this map Strategy and Goal Clarity are seen as most heavily influencing Alignment. Customer Information, on the other hand, is viewed as a major driver of Capabilities in this firm. Recognition is viewed as a major driver of Engagement. The list of drivers will vary somewhat depending on the type of organization and the business strategy. Customer Information, for example, may be less significant as a Capabilities driver for a mining company than it is for a financial services firm.3

In contrast, “enablers” refers to general factors that influence both the drivers and multiple ACE components. In Figure 8.1, the enablers are to the left of the drivers. In this example, the organization has a strong customer intimacy value (one of several values supporting the “Values” box in Figure 8.1) which should influence both customer-focused goals (Goal Clarity) and Customer Information. Another key value is respect for people, which enables the effective Recognition of talent to help employees feel respected. A value, such as ethics, should influence Alignment if employees understand its meaning and if senior leaders and managers exhibit behaviors that exemplify it.

Leadership Role Modeling (in Figure 8.1) also typically influences ACE. For example, leader communications often bolster Strategy and Goal Clarity, which in turn drive Alignment. Manager or supervisory behaviors (Supervisory People Skills), when they reflect espoused beliefs and priorities, often affect Engagement. Conversely, unfair policies, favoritism, and closed communication usually detract from Engagement.

The talent strategy map helps everyone in the organization understand the connection between enablers, drivers, ACE, Talent Outcomes, and Organizational Results. It can also help a leadership team clarify and become aligned around a unified strategy as the team members discuss which of many possible enablers and drivers are most central to increasing People Equity within their organization.

Creating the Map

How, then, is such a map created? The basic ingredient is getting the right stakeholders in a discussion of its design. It is also best to work from right to left, first gaining agreement on the most important business results and their associated Talent Outcomes. When we facilitate such sessions, we find that having as many of the main decision-makers as possible involved in the discussion is imperative. When challenged with the task of identifying the major factors that drive business or unit results, leadership teams uncover hidden and often divergent assumptions about people and business relationships — many of which are not agreed upon. Such discussion can be quite rich, and if well facilitated, can bring leaders with very different perspectives to common ground.

As I suggested, focus first on key results. What are the two to four critical results for the organization’s — and the leader’s — success? When these are agreed on up front, the ensuing discussion can productively focus on what is needed to produce these results, not rehash what the goals should be. The causes discussed will typically include a variety of factors: customers, operations, suppliers, environment, and certainly talent. Using balanced scorecard thinking, the team should check to make sure that it has a balanced representation of success factors across these categories.4

Here, we are more concerned about the people or talent drivers. If the organization has a scorecard but has not yet identified the critical people or talent drivers of its success, this should be the first step. This approach puts the focus on a special driver of success — talent. Most leaders need support in defining the people strategy either from their HR team or from external experts because an effective process requires merging human capital facts and evidence with business imperatives. For example, if several leaders think Engagement is a soft concept, someone needs to provide evidence that it is not, including ways of measuring Engagement and studies showing its strong link to business results.

Often, leaders will find that the factors they can influence most are those factors to the far left in the diagram. They cannot, for example, push a button and change Engagement, but they can influence a variety of drivers such as recognition, fair treatment by supervisors, or professional growth and development. These, in turn, can be expected to influence Engagement.

We recommend limiting the number of concepts included in the final map to a manageable and strategic few. These discussions often generate far too many potential human capital drivers and enablers than can be managed. In the end, people often argue that everything is connected to everything. This may be true in the extreme, but some drivers and enablers will have a bigger impact than others. In the above example, Recognition was identified as a major driver; while fair treatment and development are not unimportant, for this firm, Recognition was a critical gap that was inhibiting Engagement and other important outcomes. These tradeoffs are important in the discussions. Our team has a favorite expression — “Twenty is plenty.” If the concepts in your map begin to exceed 20 you should spend additional time reprioritizing.

Talent Categories

We are often asked what categories should be on the scorecard, and as alluded to earlier, the answer really lies in what talent issues must be managed to execute your strategy. That said, some frequent categories appear on many strategy maps and talent (or human capital or balanced) scorecards:

While this is not an exhaustive list, it represents some of the most frequent issues that are part of the talent value chain.

Creating the Talent Scorecard

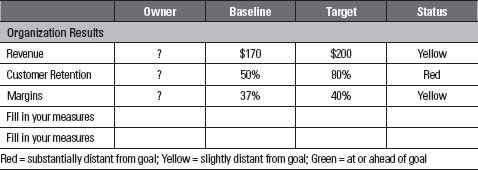

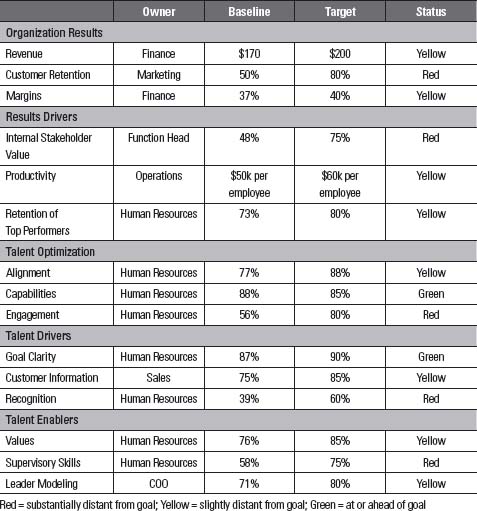

Table 8.1 is a sample talent scorecard. It includes measures for all the boxes in the talent map in Figure 8.1, owners, baseline performance levels, targets, and current status. Omitted here, but sometimes included in such maps, are clear operational definitions of the concepts, which are crucial. If everyone does not have a clear definition of retention, for example, it will end up being viewed, measured, and managed in many different ways.

It should also be noted that there can be two types of owners: process/results owners and measurement owners. The latter have the responsibility to ensure that data are collected, synthesized, and reported regularly for these metrics. The former have responsibility for moving the performance needle. In this sample, we have primarily indicated the Process/Results owners. While HR is listed as an owner for a number of these scorecard categories, line management and HR should partner to achieve many of the talent goals. For example, while HR can provide supervisory training and develop good retention tools, the immediate managers’ behaviors have the largest impact on turnover.

Table 8.1 Sample Talent Scorecard

A scorecard such as the one in Table 8.1, while relatively simple, can provide powerful information for focusing attention, communications, and resources. The green, yellow, and red notations in the Status column indicate whether the organization is on track to achieve its stated targets. Clearly this organization is having some trouble making its financial goals. Also, customer retention is not where the organization would like it to be. In their deliberations about how to grow the company, the leaders identified three areas they wanted to leverage: productivity, the internal supply chain (internal stakeholder service or value), and better retention of top talent. The latter was expected to help retain their best customers. Based on the scorecard information, productivity and retention of top performers are within reachable distance near-term (scored yellow), but internal stakeholder value needs to be significantly improved (scored red).

ACE scores can and should be much higher if the organization wants to achieve those results. Typically, the Engagement score is a good predictor of employee retention. As you can see, the Engagement scores are quite low. Although this organization has used brute force to drive productivity numbers, more of its top talent has not defected due to a poor economy. But it risks losing them as the market improves. Engagement also needs strengthening.

Accomplishing these goals requires improving the most important drivers and enablers of Engagement. In this example, Recognition was selected as a key driver because driver analyses performed on the recent employee survey identified Recognition as one of the most consequential factors holding back higher Engagement.5 Driver analysis is a statistical technique used to compare multiple potential drivers of an outcome — in this case Engagement — and to identify the relative importance of the various drivers in influencing that outcome. Recognition was selected because of a driver analysis, not a back-of-the-envelope guess or by looking at a printout of the survey results and picking one of the bottom five questions. The latter is one of the worst approaches to prioritization, since some of the bottom five items may not be strategic, meaning they may not be significant contributors to overall Engagement or other important organization outcomes.

A further examination of the enablers in the scorecard shows that all three enablers — Values, Supervision, and Leadership Modeling — are below target. For example, communications transparency was rated low, especially by top performers in a recent survey. This was listed as one of the company’s core values, and many employees felt that top management was not measuring up. Also, supervisor ratings were quite variable. An analysis from the employee survey indicated that about 30 percent of the immediate managers demonstrated fairly strong Engagement practices; about 15 percent displayed deadly practices; and the remaining supervisors were somewhere in the middle. These data presented an opportunity for the organization to enhance Engagement by targeting the 70 percent of managers who were not receiving stellar ratings. The 15 percent who received really low scores need to be examined for fit in people management roles, particularly if they have had a history of poor “people engagement” performance, as reflected by grievances, absenteeism, high numbers of low performers, or high turnover.

With this information in hand, HR would be in an ideal position to allocate scarce resources to those supervisors most in need of support and to avoid the all-too-frequent practice of putting every supervisor through Engagement training. Such a practice may anger high-performing supervisors who may see the training as wasting their time. In fact, why not give high Engagement supervisors an opportunity to share their expertise and practices in such training for poorer-performing managers? Such training would provide high-performing supervisors with a greater stake in shaping the business culture.

Use of the scorecard in the way I have described can help an organization’s leaders come to agreement quickly and set appropriate action priorities. Engagement clearly needs the most immediate attention; the Capabilities area, in contrast, is much stronger and should not be the first area of focus. Alignment falls in between. Bottom line, the scorecard can provide a clear action road map for allocating scarce resources in talent areas that will have the highest probability of positively influencing organizational results.

Talent Scorecard Cautions

A few cautions around using a talent scorecard should be emphasized, based on years of experience designing and using them.

Do Not Over-Do a Good Thing

As one of our clients advised a Conference Board audience a few years ago, “Don’t go to the metrics buffet too often. Metrus cautioned us that we could over-eat metrics, but we didn’t listen, resulting in a need for a few measurement seltzers.” Remember the motto, “Twenty is plenty.” While more measures might feel comforting, too large a number cannot be processed, understood, or managed effectively.

Define the Conceptual Issues Before Measuring

If you cannot clearly define what you want to measure and explain your rationale for doing so, you probably should not waste time trying to measure it. Make sure you have clear definitions of each concept you want to measure and its relationship to the conceptual map. Over 50 percent of the groups we audit fail to define their concepts effectively. Leadership teams often discuss a concept but then fail to clarify it fully in writing, leaving their subordinates the task of measurement definition. As a result, the leadership team is often surprised when employees show up with a measured concept that deviates from what the leadership team had in mind.

Make Sure that Metrics Have Owners

Responsible for Hitting the Targets

In addition, every concept, with its associated measure, should have people who are accountable for managing the measures to ensure that they are reported out in a timely fashion.

Record Baseline Data — Where You Started — and

Establish Precise Targets with Associated Time Periods

Clear targets mean that you know enough to establish a goal and that you have realistic expectations about what achieving that goal implies for the organization. We typically recommend both one- and three-year targets. One-year targets are close enough temporally to make them urgent and relevant; three-year targets allow for stretch goals. The top-performing organizations often set three-year targets that appear unreachable at first blush. That usually gets the juices flowing and pushes people to be innovative. However, targets should not be debilitating. If you set unrealistic targets that are not achievable, they will ultimately be ignored or lead to anxiety and burnout. Target-setting is a strategic exercise. Top management must decide where the biggest leverage points are and confine large stretch targets to these areas.

Keep the Measures Simple But Not Simplistic

In my basement, radio reception is limited. My wife came into the basement one day and said, “I don’t remember you ever listening to a Country and Western station before.” My response: “Well, I do when I can’t get any of the stations I normally listen to.” It dawned on me that my available measurement instrument, the radio, was forcing me to listen to music that was not my first choice. Many measures —often tactical —are readily available or easy to implement. Unfortunately, they may not be the ones that provide the most value. Having five good measures is better than having 20 overly simplistic ones that waste time and resources.

Surprise Metrics — That Is, “Gotcha” Metrics or Ones That

Have Not Been Socialized — Usually Die a Painful Death

Conversely, easy metrics that are not strategic, while usually not resisted or sabotaged, waste everyone’s time and distract managers from the most important issues.

Think About What Difference Measuring Will

Make — and What You Will Do Differently if

the Measure is High, Medium, or Low

This is the action test. If certain measurements will not influence your decision-making or encourage you to consider your actions, then designing such a measure is not likely to be practical or helpful.

Role of HR — Deeper Skills Needed

HR groups are increasingly needed to facilitate strategic discussions around talent in organizations. And yet, the data collected by Ed Lawler and his team at the University of Southern California’s Center for Effective Organizations suggest that HR has not moved far in this regard over the past decade or longer.6 One senior executive interviewed for this book said, “If someone wants to be in a decent leadership role in HR today, he needs to understand analytics and measurement.” Too often I hear HR people lament that they are not very good at measurement, an admission that does not bode well for their career. For years, HR professionals fought to participate alongside senior management, and now that the opportunity is here, they need to be comfortable and savvy about business metrics and strategic talent metrics. It is fast becoming the ante to be in the big game.

Action Tips

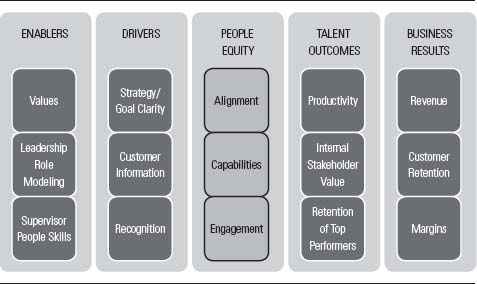

Figure 8.2 Sample Talent Map Template (with focus on Alignment)

Figure 8.3 Sample Talent Scorecard Template (with focus on Alignment)