“Development of talent is an all day every day process, not just episodic”

Kay Henry, former Vice President of Human Resources at AXA Financial

When talent arrives at your company, how close do your new employees’ expectations jibe with reality? The majority of the people interviewed for this book talk more about cultural mismatches than about competency snafus accounting for new hire failures or sub-optimal performance. ACE data from the Metrus Institute, however, point to a combination of factors that lead to inferior performance: misaligned goals or values, poor person-role fit, insufficient training or resources, lack of acculturation to a team, or ineffective performance management.

This chapter will tackle the processes that make or break stellar performance, beginning with day one on the job. While the immediate manager has a high level of influence, communications, onboarding, training, performance, and development processes are also crucial in the eventual outcome. We begin with onboarding and acculturation, then move to training, and finish the chapter with the many challenges of performance management.

Fast Facts

The ACE Perspective

If hiring is managed well, new employees should arrive at the door— physical or virtual — with their highest level of Engagement. After all, they are making a significant commitment to spend a great deal of their daily life with the new company. However, despite all the information they may have received during the hiring process, they are most likely to still be rather low in Alignment. They have not absorbed the values, nor do they know the ropes. They are intellectually Aligned with the advertised talent value proposition, but not yet with the real organization. Does the real organization come close to what these new hires thought they were joining?

According to a study done by the training firm Leadership IQ, out of 20,000 newly hired employees studied over three years, almost half (46 percent) “washed out” in the first 18 months.1 These are disturbing numbers, especially given the enormous cost of finding these people in the first place.

We also know from many psychological studies that first impressions count. Research suggests that new hires quickly make up their minds about the intermediate or long-term prospects of staying with an organization. According to the Wynhurst Group, “New employees decide whether they feel at home or not in the first three weeks in a company, and 4% of new employees leave a job after a disastrous first day.”2

If a new hire finds information and behaviors that are inconsistent with expectations on the first day, it not only sets up an Alignment problem, but it also raises real questions about the transparency or honesty of the organization. If a new hire begins to think he or she was sold a bill of goods, Engagement can plummet.

Another major challenge is acculturation — the extent to which someone absorbs and is embedded into the culture of the organization.3 This is far from a trivial issue. While a part of onboarding is focused on orientation and information, acculturation is the essential ingredient required to ensure a fully functional, highly productive employee who wants to stay with the organization. A great deal of research has been devoted to this subject, much of it focusing on the developing relationship between an employee and his or her manager or coach. When a positive relationship jells, a large step is taken toward optimizing performance. Managers who look through an ACE lens do far better in establishing such relationships than those who do not. For example, we have discovered in our research that managers and peers of high ACE units tend to have outstanding ways of welcoming a new hire. The best managers begin working on the welcoming of new hires before the day they show up, with preliminary phone calls and information to help the new arrival hit the ground running both technically and culturally.

There is nothing more frustrating than not knowing the ropes. In highly productive cultures like the one at WD-40 Company, managers and teams help convert the values statements that a candidate reads during the interview into real behaviors that are lived. These behaviors have been discussed among teams and are used to acculturate new hires.

Capabilities too play a role in maintaining high levels of Engagement. Does the new hire have sufficient skills, information, and resources to do the job and meet customer expectations? If not, he or she will quickly become discouraged. Likewise, when a new hire expects the organization to provide sufficient training that is not offered, skill gaps (part of Capabilities) and distrust (a driver of low Engagement) will take a toll on Engagement.

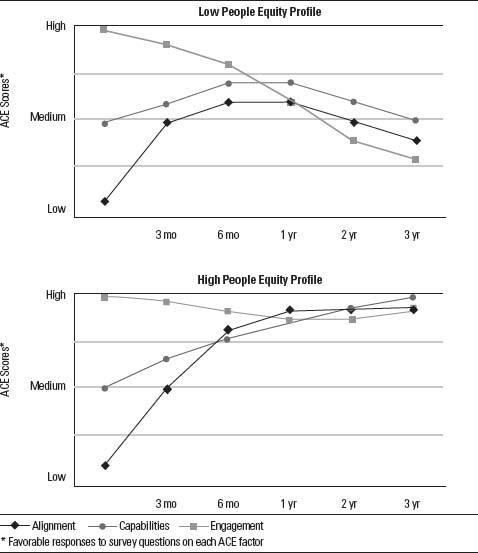

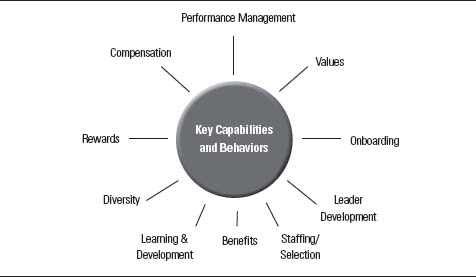

A growing GreatPractice is to track levels of ACE and some of its drivers early in the onboarding process. A modified ACE survey (as discussed in depth in Chapter 7) to assess onboarding effectiveness at 30, 90, and 180 days can provide rapid feedback on the acculturation process and can enable a manager, a mentor, or an HR coach to intervene if Engagement begins to drop or if Alignment and Capabilities do not appear to be increasing at the expected rates. Figure 11.1 shows how ACE scores can change over the early course of one’s tenure with an organization. In the beginning, Engagement is about as high as it gets, while Alignment is low but growing. Capabilities are high or low, depending on whether an organization hires “competency ready” talent or prefers to train new employees. In any case, early ACE assessments can help determine whether new hires are progressing as anticipated.

Figure 11.1 Potential ACE Scores from Onboarding to Maturity

Onboarding is a crucial stage, one that can be strengthened by examining events through an ACE lens.

Before moving on to training, consider how organizational renewal and change can occur if all new employees wholeheartedly embrace the existing culture. Strategically, an organization should consciously decide how much rejuvenation and how many fresh perspectives are needed. Is this a mature business, perhaps a “cash cow” that should be left as is? Or is it a dynamic fast-growth unit that must change rapidly to fend off new competitors and rapidly adapt to changing market conditions? In the latter case, targeting a meaningful amount of outside hires relative to internally filled roles may be wise strategically. The organization needs to be firm about what it does not want to change — core values and key employer brand attributes, for example — but also open to new thinking about what it does want to change. New ideas can be easily squashed if the organization does not have clear roles (and rewards) for change agents. These desires need to be built into the selection, acculturation, and training processes so that the desire for adaptability is not killed along the way.

Training — Getting the Right Competencies to Succeed

Fast Facts

The ACE Perspective

Training is a crucial process for most organizations, especially during the early stages of employment as the organization seeks to increase the skills of new hires and to align their behaviors to deliver great results to internal and external customers. But research in recent years suggests that training in the traditional classroom is far less effective than on the job. In fact, the prevailing wisdom is that 70 percent of competency training should be on-the-job experiences that address a specific need; approximately 20 percent should come from feedback and reinforcing good and bad behavior related to that need; and only 10 percent of training should be delivered in traditional physical or electronic classrooms or via reading — the 70/20/10 model.4

Princeton University’s human resources department uses the 70/20/10 model to train employees, with 70 percent of learning coming from real-life and on-the-job experiences, 20 percent from feedback and from observing and working with role models, and 10 percent from formal training.5

When this model is used, ongoing performance discussions become the centerpiece of effective learning. If the employee, manager, and internal stakeholders are not aligned, development will be slow to occur, if it occurs at all. If too little feedback is provided, employees will begin to stagnate and feel frustrated by a lack of progress. Or if the feedback is poorly aligned with the job requirements, it can waste time and resources.

Many organizations miss an ideal opportunity to increase their selection success rates by not including early training as a secondary selection screen. It is much less expensive for new hires to fail during early training than after months on the job, especially considering that poor performance or treatment of customers often results in significant financial losses.

Although training is typically focused on Capabilities, it also represents a major Alignment challenge. The issue is whether the training programs have been carefully designed to match the same criteria that were used for hiring, and subsequently for performance evaluation. If not, the performance of some candidates who met hiring criteria may wash out in training, where they suddenly face new success criteria. Or they can earn an “A” in training, only to fail on the job because they do not perform to a manager’s expectations. Again, looking through the lens of the talent lifecycle reveals the value of aligning hiring, training, performance expectations, and all related talent processes, and of ensuring that measured success criteria across these activities are consistent.

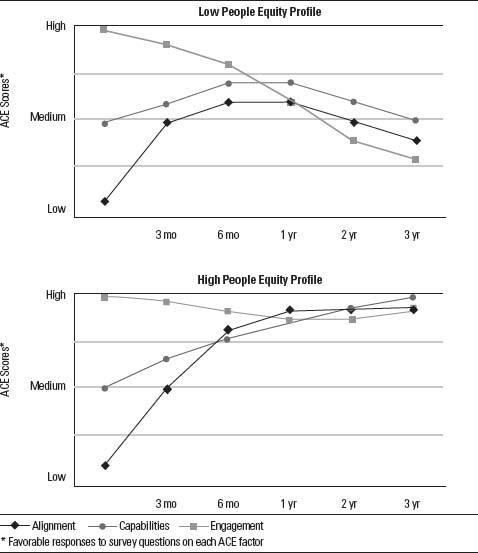

To drive this point home, a partial example from a major energy company is depicted in Figure 11.2. The company anchored all its chief management and human capital processes with desired behaviors, thereby increasing the likelihood that it will have Alignment across the talent lifecycle. For example, the company’s reward system includes variable compensation features that supervisors can use to induce employees with key competencies to stay longer. Or their performance management system is tied to particular behaviors that company leaders have determined are most desired in their culture.

Figure 11.2 Energy Company Example: Process Alignment Across Talent Lifecycle

Another common problem with training efforts is ineffective evaluation measures. Few organizations do a good job of measuring the return on investment of their training. Most view such an effort as too complex and costly. However, obtaining estimates of return on investment does not have to be a drawn-out process, but it does involve measurement beyond simple “smile sheets” administered at the end of a training course. While it is nice to have users rate a course or program as enjoyable, insightful, or entertaining, research has shown that such ratings have a very low correlation with application of new behaviors back on the job or with changes in how employees interact with customers or other stakeholders.

The real measure of training effectiveness is whether the course ratings tally with supervisory ratings of the same person back on the job. Are desired behaviors exhibited at a higher rate after the training? Do stakeholders or customers see a difference? For example, multiviewpoint performance evaluations from supervisors, peers, and customers, when scored consistently, allow training providers to obtain feedback on job performance at meaningful intervals after training. From an ACE perspective, we should be asking — and measuring — whether Alignment, Capabilities, or Engagement has increased during and after training. If not, why not?

Maximizing Performance

Fast Facts

The ACE Perspective

When the Metrus Institute asked approximately 100 executives attending a recent conference how they felt about their performance appraisal and management systems, about 50 percent said they would throw them out if they had a better replacement. I found this number surprising, given that performance improvement processes have been extensively studied by organizational psychologists over the past 50 years.

Most human capital evaluation systems in use today have some fundamental flaws:

And the list goes on.6 Now we will take a look at each of these issues using our ACE lens.

Performance Systems Typically Depend

on Amateurs to Provide Feedback

Giving and receiving constructive feedback is a skill that takes years to develop, even for skilled psychologists and trainers. And yet, we turn over this critical task to managers who are minimally trained or not trained at all. Some managers are naturals and do fine, but many struggle, often admitting that they hate conducting appraisals. A manager of a financial services company echoed what we have heard many times before, “I hate doing performance appraisals; it kills all the good I have done throughout the year communicating with employees and building a team.”

Research tells us that over 70 percent of people believe their performance is higher than the feedback they receive from their managers or peers. This percentage is likely to be even higher with Generation Y employees who have grown up in a world of praise and positive reinforcement of their skills and abilities. In the interest of increasing Capabilities and Alignment with performance goals, managers are damaging Engagement by providing devaluing feedback. Worse yet, many managers either harm Engagement further by saying the wrong things or back off to salvage Engagement at the expense of providing realistic feedback that could improve Capabilities or Alignment. Providing feedback to people requires skilled managers who have been trained in the proper techniques. This is why organizations such as Pepsi, Procter & Gamble, and General Electric put so much emphasis on developing the performance management skills of their leaders. A number of sources offer more information on this topic.7

Many Performance Systems Force-Rank People

into a Normal or Gaussian Distribution

Force-ranking exacerbates the challenges discussed in the previous point because it requires managers to make people in their unit “fit” some theoretical distribution that may or may not apply to the group. While performance often follows a normal distribution, in many situations it does not. These distributions, for example, take their shape when we have a sizeable population. If your unit has five people, it is unreasonable to expect that one can fit each of five points on a performance curve. From a talent lifecycle standpoint, it seems unreasonable to think that we select the very best talent we can afford from a “normal” curve in the talent marketplace only to expect this talent to have a broad range of performance. Making such an assumption is as much as admitting selection has been done poorly.

Companies like WD-40 Company buck the trend by assuming they can get far more “A” than “B” or “C” performers. Sounds crazy? Garry Ridge, the company’s CEO, holds every leader of the organization accountable for helping employees set “A” targets and then supporting them to get there. Does everyone finish the year with an A? No, but they have a significant percentage that do because they started with different assumptions and expectations about performance. Consider whether your organization could achieve 70 percent A performers, 25 percent Bs, and 5 percent or fewer that need to send out their resumes. Defining “A” performance for your organization is essential. This should be performance that allows the organization to hit its stretch targets for market growth, revenue, profit, or whatever key metrics are in place.

The Application of Performance Systems Is Highly Variable

from Manager to Manager and from Department to Department

To make matters worse, when organizations decide to “curve” performance, they then face the task of calibrating performance across different teams. Is the criteria for an “A” the same in different departments? If not, the organization will create feelings of inequity over time and will likely end up with a non-normal distribution, despite best attempts not to do so. Organizations have tried various creative ways to overcome the natural bias of managers to fight for their own people in the calibration discussions. I do not think we have found one organization using such an approach that is confident it has truly calibrated the ratings. Typically, we find cynicism and feelings of unfairness. The question is why we go through all this work to “calibrate” ratings. Ah, pay!

Linking Pay to Performance Ratings Raises the

Stakes and Forces Win-Lose Outcomes

One of the biggest problems with linking performance improvement discussions to pay — as decades of psychological studies have shown — is that the employee is primarily focused on pay and not performance feedback. We underestimate the sheer power of financial remuneration in this equation, not so much because of the absolute amount of pay, but because of the symbolic impact of pay levels on psychologically important outcomes, such as self-esteem, status, feelings of accomplishment, perceived equity, or fairness compared to others. The result is often lower Engagement and Capabilities. Why Capabilities? If the participants in the performance feedback conversation are focused on pay, there is little likelihood that much will be retained about ways to improve performance or Capabilities. We recommend separating pay discussions from development discussions and connecting them only to aggregated performance reviews. If you have monthly or weekly reviews as Intel does, one event does not stand out as the event that determines pay increases.

The Event

Too often, the performance review becomes an annual event — a final exam in which the “student” has to convince the “professor” to give her an “A.” Most of you have participated in “the event” as either a “professor” (manager) or “student” (the one being rated). The employee has his or her list of accomplishments and excuses for goals that were not completed, while the manager has put together the evidence that justifies placing the performer in a particular performance or pay band. Such once-a-year events are often ugly, but they do not have to be.

Intel, for example, expects performers and their coach to get together every week for 10 minutes to have a conversation that usually includes a discussion of performance barriers, support needed, and even changes to goals as the year evolves. This ongoing dialogue is an alternative approach to “the event,” providing continuous feedback and mutual expectation calibrations throughout the year. This process also allows developmental discussions to occur along the way, a far more productive way to connect performance to personal development than a year-end “improvement list.” It also allows feedback to occur much closer in time to performance events, another thing psychologists have shown to be extremely critical for development, whether you are six or 60!

There is no doubt that performance management is a crucial organizational process that must be effective. I advocate tossing this process out if you do not overcome the challenges above. It will cost you more in ACE than you gain from its execution. Conversely, I think organizations have employed innovative solutions to overcome some of the debilitating features described above:

An effective performance management process needs good metrics. How can its effectiveness best be evaluated? One source of feedback would be questions related to Alignment in a survey that captures ACE (see Chapter 7). A good ACE survey will have driver questions related to the effectiveness of goal-setting, understanding of both organizational and functional goals and strategic direction, the impact of performance reviews, the alignment of reviews with development, and pay-for-performance questions.

In this chapter, we addressed the critical performance optimization processes beginning at time of hire: onboarding, training, and performance management. In the next chapter, we will look at talent processes that assure the future of the organization.

Action Tips