ovels about tween female friendships haven’t just remained popular through the years because figuring out the nuances of social interaction is one of the only nonschool pursuits available to people too young to drive. It’s because the basic format of the friendship novel—friends tackle a problem together, have a moment of doubt, but come out the other side victorious—can be easily adapted to any era. In fact, teen friendship novels have changed remarkably little since they were first introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century. And I don’t mean that in the way a drama teacher would say, “well really, Shakespeare was the first rapper.” They are eerily similar.

ovels about tween female friendships haven’t just remained popular through the years because figuring out the nuances of social interaction is one of the only nonschool pursuits available to people too young to drive. It’s because the basic format of the friendship novel—friends tackle a problem together, have a moment of doubt, but come out the other side victorious—can be easily adapted to any era. In fact, teen friendship novels have changed remarkably little since they were first introduced at the beginning of the twentieth century. And I don’t mean that in the way a drama teacher would say, “well really, Shakespeare was the first rapper.” They are eerily similar.

Take Gertrude W. Morrison’s Girls of Central High series, published from 1914 to 1919. The book’s group of pals includes the strong leader, the sporty friend, the wacky twins, the one from an arty family, and the rich one; once assembled, the friends play on school sports teams, annoy their uptight teachers, butt heads with the school bully, prank their classmates, raise money for a family in dire financial straits and, on one memorable occasion, set off firecrackers indoors (in 1919! The year many US women got the right to vote!). It’s not that this series is wildly progressive and forward-looking—these are books in which characters sternly use the word “scamp” and discuss whether a codfish would make a good Christmas present. It’s just that these plots and character types are timeless.

But for all their enduring themes and happy endings, friendship novels have their shortcomings. As society evolves, these books don’t instantly catch up. Middle grade novels from the ’80s rarely portrayed girls of color hanging out and doing normal tween stuff without a bunch of white girls also present, despite having been published years after the peak of the civil rights struggle. And all too often, these books glossed over the very real pain young female friends can cause one another. But though they’re far from perfect, they considered female friendships worthy of topline billing— decades before most films, TV shows, or grown-up novels agreed.

You know that Frank Sinatra song, “You’re Nobody til Somebody Loves You”? Well, in the realm of ’80s and early ’90s girls’ novels, you were nobody til somebody wanted to start a club with you. Sure, needlessly intricate tween social infrastructure dates back at least to the bust-obsessed Pre-Teen Sensations of Judy Blume’s 1970 novel Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, but the mid-’80s popularity of the Baby-Sitters Club (see this page) sent publishers scrambling for quick ways to cash in on tween crews. The result was a flood of books that implied that you couldn’t put two 12-year-old girls alone in a room together without one appointing the other one treasurer.

But the tween club frenzy didn’t appear overnight. In fact, one series in particular connected the ’70s-era Pre-Teen Sensations with the club-crazy world that came after. Betsey Haynes’s 1976 novel The Against Taffy Sinclair Club was exactly what it sounds like: a book about a group of fifth-grade girls who form a club specifically to rag on their classmate Taffy. What has Taffy done to become so loathed? It’s not important (but for the record, it’s that she grew boobs before they did). What is important is that the ATSC girls undertake all the ’70s equivalents of Instagram trolling: creating a slam book all about Taffy, spray painting “Taffy Sinclair Has Her Period” on the school sidewalk, and other mundane middle-school cruelties. The slam book falls into the wrong hands, and Taffy’s mother freaks out on the ATSC. Eventually we learn that protagonist Jana is actually worked up over her deadbeat dad and taking it out on the poor Taffster: “I hated myself, and I kept thinking that it was no wonder that Taffy Sinclair hated me, too.” Chastened, the girls vow to change their cruel ways, becoming a newer, kinder club called…the Fabulous Five!

At first blush, the titles in the Fabulous Five series, which comprised thirty-two volumes published between 1988 and 1992, look more like a Baby-Sitters Club knock-off than the tales of a rehabilitation group for reformed school bullies, but the books were indeed a deft(ish) import of familiar characters into a new, kinder era of friendship novels. Before the start of the spin-off series, the Fab gang had a whole set of adventures, in the 1984 sequel Taffy Sinclair Strikes Again (plot twist: they still totally hate Taffy Sinclair) and the 1987 follow-up Taffy Sinclair, Baby Ashley, and Me (in which a member of the Fab Five and Taffy find an abandoned baby, which somehow still turns into a petty sixth-grade power struggle). But eventually Taffy leaves town and the gang transitions to dealing with lower-key issues like losing TV privileges (in The Great TV Turnoff) and running a taxi service (in Teen Taxi), rather than trying to emotionally destroy a fellow child. In that transition, they showed what changed in the Great Friendship Clubbening of the ’80s: dramatic girl-on-girl hatred was out; kind, supportive tween friendships were in.

The Fabulous Five’s convoluted origin story was certainly the exception, however; most groups had an origin story so simple, you could write it on a friendship bracelet. The club in Linda Lewis’s 1985 novel We Hate Everything but Boys (see this page), for instance, was committed to a dead-simple premise, which continued through all eleven volumes of the subsequent Linda series (named for the series star, who shares a name with the author, go figure), including the 1993’s spin-off Preteen Means In Between and the 1988 prequel 2 Young 2 Go 4 Boys: Linda and her friends are totally gaga for dudes. But their club isn’t just about plotting to make contact with your crush; they branch out into other related issues, such as the importance of finding a “cry spot” in the park where you weep about your romantic difficulties (that’s a dating skill you’ll want to hold on to through your twenties, girls!).

Probably the only series “by Lindas, about Lindas,” the Linda series ran for 11 books, following the characters from fourth grade all the way through senior year of high school.

Other club series managed to set up a straightforward premise and immediately poke holes in it. Deirdre Corey’s Friends 4-Ever series, which debuted in 1990, chronicles a group of friends who become pen pals to keep up with their friend Molly after she moves away, which checks out—each volume is titled after cutesy, letter-writing-related puns like P.S. We’ll Miss You and 2 Sweet 2 B 4-Gotten (and people blame cell phones for poor spelling!). Except, midway through the series, Molly moves back! But all the Friends 4-Ever keep writing each other letters! Even though they live in the same town and see each other all the time! Perhaps their true best friend was adhering to organizational protocol at all costs.

Unlike Linda and her boy-obsessed crew, or the correspondence-crazy Friends, the gang in Betsy Haynes’s 1995–6 Boy Talk series (not to be confused with Girl Talk; see this page) formed a club not to kvetch about their own dating difficulties but to micromanage the love lives of others. Best pals Su-Su, Joni, and Crystal are sick of sitting around and having names that make them sound like they work at a food co-op—they want to provide romantic advice to the public! With that premise, the girls proceeded to dish out dating guidance for nine books, despite having no qualifications besides moxie, an undying desire to know everyone’s personal business, and parents who didn’t care how long they tied up the phone.

All entries in the Swept Away time-travel series had pun-tastic titles alluding to the time period of choice, but some of them—like Gone with the Wish (Civil War era) and Spell Bound (Salem circa the witch trials)—took their heroines to eras that were problematic at best and dangerous at worst. But romance was found nonetheless!

Tween fiction offered a club for almost everyone, including the aspiring time traveler. As has been well-established by the acclaimed 1989 documentary film Back to the Future Part II, mad professors rarely included female teens in their time travel experiments, preferring instead to knock them unconscious and leave them in an alley. It’s like they’d never even heard of Title IX! Luckily, the girls of the Swept Away series worked tirelessly from 1986 to 1987 to close the time travel gender gap. Why time travel? Oh, for a bunch of reasons: to witness historical events, to authenticate family heirlooms, to prevent the teen versions of their moms from dating guys with unappealing names like Dick Flick, and so on. The science is a bit head-scratching—the girls transport themselves via a machine jury-rigged from the town library’s modem and a purloined laser gun, which…sure?—and the friends have a downright laissez-faire attitude vis-à-vis potential repercussions. So you’re warping the fabric of the universe? Big deal! Party with Elvis! Manipulate the teen version of your mom! Act like a total narc at Woodstock! Who cares? Time clearly has no value if you can manipulate it with some junk you got at the library! Still, the series did give teen girls credit for hacking time travel just like their male peers, which counts for something. Remember, a book can be culturally pioneering and also not very good at the same time.

On the complete opposite of the plausibility spectrum was Susan Saunders’s ultra-realistic Sleepover Friends. The series ran for thirty-eight volumes from 1987 to 1991, a genuine eternity in tween fiction, all of it predicated on the simple fact that sleepovers are utterly bitchin’. Sure, the friends had individual personalities, or as individual as you get in these series: Kate the bossy one, Lauren the athlete, Patti the studious one, Stephanie the arty one who is also the one who used to live in the city. And some adventures took place during the day—#11, Stephanie’s Family Secret, memorably involved winning a burro in a contest. But the true glory of these books was in the sleepovers themselves, which were described in achingly luxurious detail: what junk foods the girls ate, how they wasted time, how no one’s parents ever seemed to give them any guff about it (“We stayed up really late watching a double feature on Chiller Theater….And we slept late the next morning. When we finally got up, Stephanie’s parents had blueberry-banana pancakes waiting for us”). For those of us who were roused early on weekend mornings for chores or church, or just didn’t have any friends to sit around eating blueberry-banana pancakes with, Sleepover Friends was the tween equivalent of reading about Gwyneth Paltrow’s Paris apartment in Architectural Digest.

And yet all was not entirely normal in the Sleepover-verse. As YA blogs the Dairi Burger and Sleepover Friends Forever have astutely noted, the cover of #13: Patti’s Secret Wish depicts the friends in a bookstore, surrounded by middle-grade series like the Baby-Sitters Club, the Gymnasts, and…Sleepover Friends #11: Stephanie’s Family Secret! How is this possible? Are the Sleepover Friends celebrities within their own timeline? Was some kind of inception afoot here? Maybe your friends’ parents let them bend the laws of reality, but in my house, you’ll obey my rules, young lady!

For young book geeks (and, okay, for us adult book geeks too) the mise-en-abyme of Sleepover Friends #13 is pretty much catnip; there’s a Gymnasts title third from the left, and a Baby-Sitters Club book second from the right. (Whether any tween girls cared about a book called Quarks is hard to say.)

Sadly, no other tween club series shredded the fabric of existence, but Girl Talk, a board game turned TV show turned book series, came close. The game, a gussied-up version of “truth or dare” that directed players to perform humiliating tasks like “have a conversation with a piece of furniture” and “drink a glass of water without using your hands,” came out in 1988. Naturally, it was an enormous hit with tween girls. And you know what everyone does when they have a hit board game for girls on their hands: turn it into a TV show! Sadly, when the Girl Talk TV program debuted in 1989, it was not an emotional-torture version of Double Dare but a simple variety show with skits hosted by a 12-year-old Sarah Michelle Gellar that lasted only two episodes.

But in 1990, the Girl Talkiverse introduced a new concept: books! And these weren’t popular just for a series based on a perversely cruel board game; they were tremendously popular, period, with forty-five volumes published in three years. (A number were ghostwritten by K. A. Applegate, the YA and middle grade powerhouse behind the Animorphs series and Newbery Award–winning The One and Only Ivan.) The “talk” conceit came in the form of passages of transcribed phone calls, which shook up the conventional friendship book format a bit. Like R. L. Stine’s similarly experimental dialogue-only romance (see this page), they’re something of a stylistic precursor to contemporary YA like Lauren Myracle’s 2004 novel ttyl and its sequels. However, in the Girl Talk novels, the phone call sections usually take three pages to explain something that could have been dealt with in three lines of prose. Beyond these mild structural innovations, Girl Talk dutifully played by the club series rulebook. Sabrina, Allison, Katie, and Randy had standard middle school novel personalities—the chatty one, the political one, the anal-retentive one, and the one whose whole personality is that she is from New York City—and got into standard middle school misadventures, like trying to become models and running for class president.

And naturally, no discussion of clubs is complete without mentioning some of the oldest female clubs around: sororities. YA literature in the ’80s was lousy with under-18 sororities, despite such societies being uncommon in the real world; in fact, fraternities and sororities have been banned in California public schools since the ’60s, which would make Sweet Valley’s Pi Beta Alpha illegal (not that we’re surprised Jessica Wakefield is a criminal). The most notable example is Marjorie Sharmat’s Sorority Sisters, which ran for eight volumes from 1986 to 1987. The series chronicles Palm Canyon High School’s bloodless yet brutal battles between the snobs of Chi Kappa and the down-to-earth ladies of the Pack, a new sorority formed by girls disgusted by Chi Kappa’s pretentiousness (also, they tried to get into Chi Kappa and couldn’t). The constant bickering invites the question: why not ditch the organizational infighting and just have, you know, friends? (Because then there’d be no series, duh.)

Finally, lest you write off all club book series as frivolous, there were in fact a handful that addressed topics more substantial than French-braiding. The NEATE series, put out by African American publisher Just Us Books between 1992 and 1994, had its mixed-gender group of members—that’d be Naimah, Elizabeth, Anthony, Tayesha, and Eddie, aka NEATE—join forces to deal with pressing social issues, like helping Naimah’s mother win a city council race against an unrepentant racist, raising awareness about gerrymandering, or saving a refugee shelter from closure. The magic of NEATE is that the books didn’t save this stuff for a Very Special Edition; they mixed social concerns in with more traditional middle grade stories about talent shows and demanding parents. As one of the rare series in the era to focus exclusively on African American tweens, NEATE managed to thread the needle between “real world issues” and “kid-level relationship drama” without coming off preachy—or worse, boring—showing how easily your average tween series could have packed more meaning and substance in with their tales of pizza parties and sleepovers, if they’d only tried.

In a review, Publishers Weekly praised NEATE: To the Rescue! as “a cut above the typical mass-market YA offering,” but found its “contemplative tone” and subject material “a bit at odds with the sprightly cover artwork.”

The Parents who Became Publishing Pioneers

In the late 1980s, Wade Hudson and his wife, Cheryl Willis Hudson, couldn’t find the kinds of children’s books they wanted their two children to read. While the children’s publishing business was exploding, the Hudsons saw one very obvious gap: “there were very few Black authors and illustrators creating books for children and young adults,” as Wade told me.

Though African American authors like Walter Dean Myers, Mildred D. Taylor, Virginia Hamilton, and Patricia McKissack had been publishing books that “[drew] from Black experiences and [created] Black characters,” major publishers were still more interested in publishing biographies of the same handful of famous African Americans (Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Harriet Tubman) than they were in stories of contemporary African American life. “Many white editors didn’t really understand Black life, Black culture, etc.,” said Wade. The Hudsons had firsthand experience with this kind of thinking—as they recount on their website, while trying to publish a children’s book they had created together called AFRO-BETS ABC Book, they were told by one editor, “There’s no market for Black children’s books.”

“I don’t know how many times I have heard over the years Black writers say they were told by white editors that a manuscript they had submitted didn’t seem plausible,” Wade said. “Obviously, Black life was foreign to many of these white editors.”

Ultimately the Hudsons published AFRO-BETS themselves in 1987, and in 1988, they founded one of the first publishing companies dedicated to African American children’s books: Just Us Books. Though the couple had no prior experience running a company, they believed in their vision and put their life savings toward building the business.

It paid off. Thirty years into its existence, the Hudsons still run Just Us, which has published dozens upon dozens of young adult and children’s titles (including the NEATE series, this page), some of which have gone on to become best sellers and win awards like the prestigious Coretta Scott King Illustration Honor from the American Library Association. Wade and Cheryl have each written and published over twenty books, both with Just Us and with other publishers, and in 2004, Just Us launched its first imprint, Sankofa Books, to bring out-of-print classic books about African Americans back to the market. Through the years, the Hudsons have seen the publishing industry at large become more interested and invested in diversity. “It has been a gradual change prompted by agitation and prodding by people of color,” said Wade, “and by those who support diversity in children’s and young adult literature.” But, he notes, “Book publishing, like other industries, is often driven by trends and not by a commitment to a cause or to do what is right and just.”

“Books written by people of color have proven themselves in the marketplace,” Wade said, mentioning best-selling and award-winning novels by Jason Reynolds, Jacqueline Woodson, Kwame Alexander, and Sharon Draper. “If books that draw from our country and world’s diversity are made available and are marketed the way books that are considered ‘mainstream’ are, they will do well.”

Children’s publishing is starting to catch up to what the Hudsons pioneered with Just Us. But just because things have improved doesn’t mean it’s time to stop. “Those of us who have, for years, been in the forefront of the movement for diversity, equity, and inclusion in children’s literature, and those who have joined us, must continue to push and advocate,” said Wade. “There still is much more work to be done.”

Summer camp books are hardly an ’80s phenomenon. At least since Laura’s Luck, Marilyn Sach’s 1965 tale of an urban bookworm’s summer trip to the sticks, summer camp has been an archetypal YA and middle grade experience (and also a great place for teen characters to get a job—see this page). In just one five-year stretch Ellen Conford’s Hail, Hail Camp Timberwood (1978), Jane O’Connor’s Yours Till Niagara Falls, Abby (1979), Gordon Korman’s I Want to Go Home (1981), and eventual Baby-Sitters Club mastermind Ann M. Martin’s first book, Bummer Summer (1983) were published, all of which helped establish the major plot conventions of camp books, i.e., the kid who’s resistant to going to camp is initially fearful, then finally makes some friends, gets out of their social comfort zone, and grows as a person thanks to good times had in the Crafts Hut. In Bummer, for instance, 12-year-old Kammy reluctantly ships off to Camp Arrowhead because she can’t get along with her new stepfamily. While there, she makes new friends, antagonizes a bully, learns to face her fears, and realizes she will come home a better person, changed in the way that only using an outhouse for several weeks can change you.

The fact that so much of camp lit is based on things that can only really happen to a person once is probably why just a handful of authors have been bold enough to set a whole series there. Among those few chronic campers are the stars of Marilyn Kaye’s Camp Sunnyside Friends series, which kept the girls of Cabin Six in action for twenty volumes between 1989 and 1992. Because everyone at Camp Sunnyside knows each other and the camp itself, there’s no mystery about whether things will work out; the girls of Cabin Six, with their well-defined archetypes, fit in neatly with your babysitters, sleepover-ers, and girl talkers. They aren’t scared to go to camp, they’re excited about dealing with a whole new social landscape, and they most definitely don’t utilize the fluid nature of the camp experience to reinvent themselves. Nope, they just ride horses, play color war, eventually learn that all boys aren’t yucko, and so on. It’s all stuff that, honestly, they could have also done at home—but, as in many tween books, the window dressing makes all the difference.

In the real world, women’s sports rarely get media coverage on par with that of men’s, but in girls’ novels, they’ve been getting their due for longer than you might think. The Girls of Central High hit up a bunch of different extracurricular sports, and Jane Allen, heroine of her eponymous 1917 series by Edith Bancroft, played college basketball, which was especially cutting-edge considering the sport had only been around since 1891. That said, and despite the fact that 1972’s Title IX required schools to provide female athletes with the same resources as their male peers, the ’80s series boom was slow to feature sports outside stereotypically “female” disciplines like cheerleading, gymnastics, and ballet.

But boy, did those three get attention. The Cheerleaders series ran from 1985 to 1988, starring a squad of all the usual series suspects: the sassy one, the one who doesn’t want anyone to know her family is actually broke, the one who is super-serious and focused because she used to be terribly sick, the mean girl who thirsts for sweet revenge against the protagonists, and, of course, the hot guy who would be perfect for our heroine except that he’s too poor (?!). Through a remarkable forty-seven volumes, the gang struggled through questions of jealousy, familial discord, and sports ethics, digging a little deeper rather than just rah-rah-rahing along. Many Cheerleaders authors went on to become big names in YA, including Caroline Cooney (see this page). Even horror king Christopher Pike (see this page) contributed Cheerleaders #2: Getting Even in 1985 (despite the fairly ominous title, nothing Pike-esque happens to the squads).

Cheerleading may have been an American teen sport since time immemorial (okay, actually since at least 1877, but the first women weren’t allowed to participate until 1923), but gymnastics didn’t take off as a typically tween pursuit until after the 1972 Olympics, when Soviet teen Olga Korbut transformed the sport from glorified dance aerobics into a flashy, acrobatic crowd-pleasing performance. By the time 16-year-old American Mary Lou Retton won the all-around gold medal at the 1984 Olympics, gymnastics had become a full-blown tween obsession. So when the 1988 Olympics in Seoul rolled around, author Elizabeth Levy was ready. Over the course of four years, her Gymnasts series followed four tween gymnasts of varying ability, all of whom are members of the Pinecones, the beginner’s team at Evergreen Gymnastics Academy. They each carry their own baggage: a fiery temper, a mother who was a gymnastics star, a famous dad whose celebrity causes others to treat her differently. They learn, they grow, they wear hot dog costumes, they eventually figure out how to get along with an 8-year-old gymnastics prodigy. As someone who was into gymnastics mostly because I liked playing with the chalk, I can’t speak to whether their descriptions of landing jumps and flips are accurate. But they certainly are entertaining, and they provided the kind of wish fulfillment an average tween tumbler would have been eager to devour between practices.

Most of the forty-seven Cheerleaders titles alluded to intense drama, athletic competition, or both—to wit, Splitting (#6), Playing Games (#9), All or Nothing (#39)—but its final title, Dating (#47) is blissfully literal. The Gymnasts, meanwhile, skewed a bit more wholesome, and concluded the series with Go For the Gold: A Gymansts Olympic Special.

Finally, there was ballet. Many series included characters who had a pair of toe shoes lying around, but Jahnna N. Malcolm’s Bad News Ballet series, which debuted in 1989, put dance front and center in its tales of a group of mismatched weirdos, including a nerd, a fish out of water, and a vaguely butch tomboy, who must fight a group of wealthy and far more polished rivals for ballet supremacy. It’s a classic snobs vs. slobs narrative, this time transposed onto the world of dance classes—which, at a time when girls of all different backgrounds were joining the once-rarified world of ballet, was a particularly hot commodity.

But not all girl-heavy sports involve sparkles, leotards, and hair-spraying your ponytail into a bun hard enough to inflict blunt trauma. Some instead involve stinky barns, special pants, and smacking giant animals on the butt with a crop! I speak, of course, of the equestrian arts. As someone who has never gone through a horse phase, I’m reluctant to even try to write about these series; the bond between a real woman and a fictional horse is intense and remains intrinsically mysterious to outsiders (even us outsiders who really, really tried to get into Breyer figurines in fifth grade). The power of this bond explains why horse books for children have been published virtually nonstop for the past 150 years, from Black Beauty in 1877, to early series like Billy and Blaze, the Black Stallion, and Misty of Chincoteague, whose first books were published in the ’30s and ’40s.

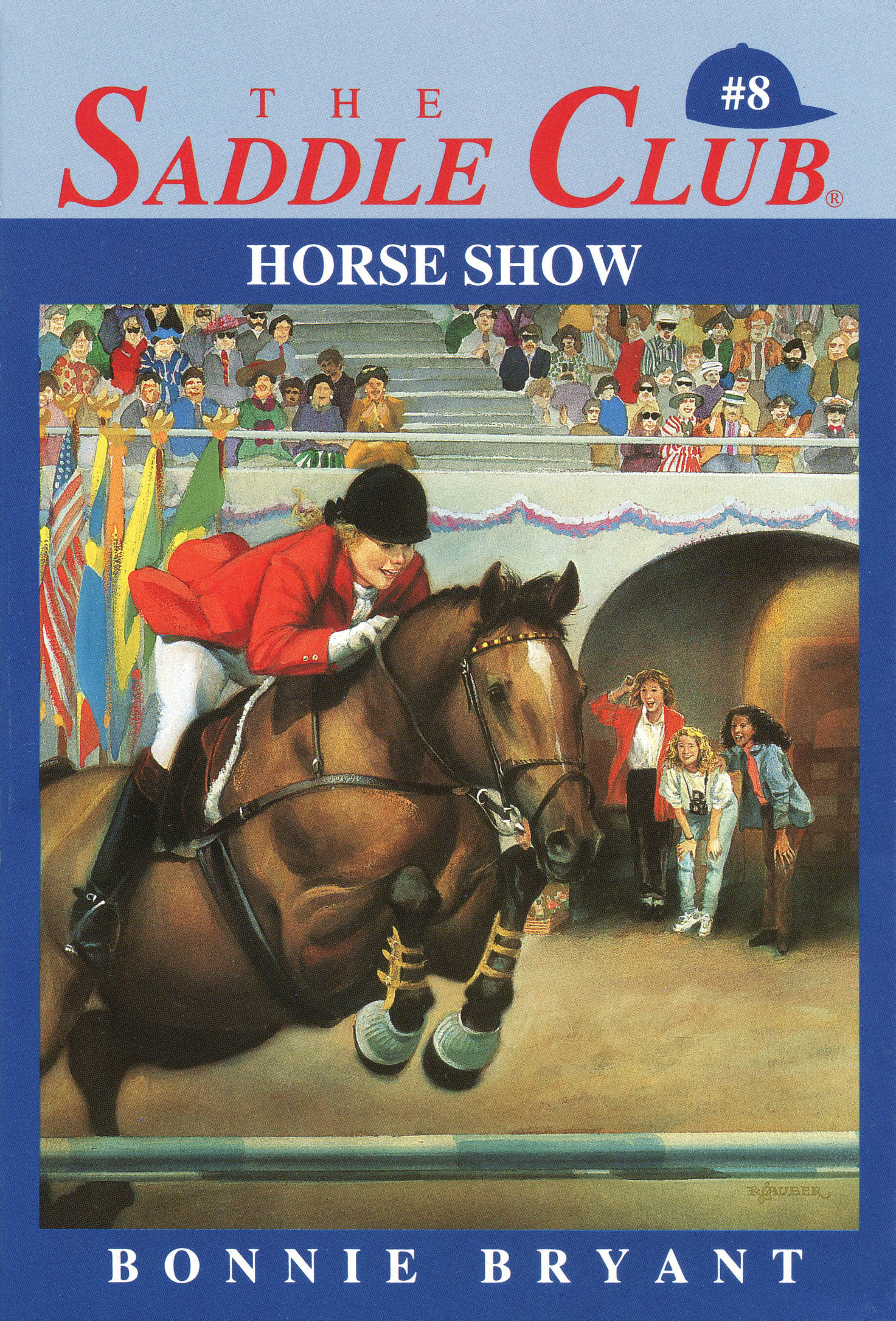

In the late ’80s, that lineage begat Bonnie Bryant’s Saddle Club, which along with Baby-Sitters Club and Sweet Valley High is one of the most iconic girls’ series of the ’80s and ’90s. Much early horse lit had focused on either intense thoroughbred racing, wild horses, or farm animals, but this series prettied up the equine novel with riding lessons, little bows, and French-braided manes to create maximum appeal for yuppie offspring. After launching in 1988, the Saddle Club let readers gallop along with riders Carole, Stevie, and Lisa for 102 volumes, plus Super Editions, the spin-off series Pine Hollow (which follows the Saddle Club girls as older teens), and a younger readers’ series, Pony Tails. While BSC reigned supreme by feeding reader fantasies of friendship (and, okay, a tiny bit of power) and Sweet Valley earned obsessive fans with its shameless drama, Saddle Club got to the top by nailing the horse girl ideal.

Of course, some of the major middle-grade-series tropes show up—Stevie is the tomboy, Lisa is the type A, Veronica is the rich mean girl, and the books’ messages emphasized believing in yourself, caring about your friends, and handling tragedy. Still, horses are no mere garnish to help this series stand out from others—horses and horseback riding are its heart. Case in point: Carole, the third member of the Saddle Club, doesn’t fit neatly into your classic ’80s middle grade series molds because her “thing” is…she’s a talented, dedicated rider. In the world of the Saddle Club, that’s a trait that can help shape your identity, sense of yourself, and relationships with others as much as “being super-organized” or “hating ‘girly’ stuff” or any of those other tween archetypes.

Saddle Club ran for well over a decade, outlasting similarly themed competitor series like Chris St. John’s Blue Ribbon (1989), Elizabeth Lindsay’s Midnight Dancer (1993–97), Jeanne Betancourt’s Pony Pals (1995–2003), and Joanna Campbell’s Thoroughbred (1991–2005), which, at seventy-two volumes plus spin-offs, is nothing to sneeze at. But Saddle Club’s lasting popularity isn’t due just to the idea that some girls just really love horses— though some girls do really love horses, and Saddle Club is the only major series to convey how wonderful it feels to connect with animals, especially at an age when human relationships often become fraught and confusing. But the books also get the ecosphere of tween obsession right, utterly nailing the way an activity can connect with your heart and soul and become the only pursuit that matters.

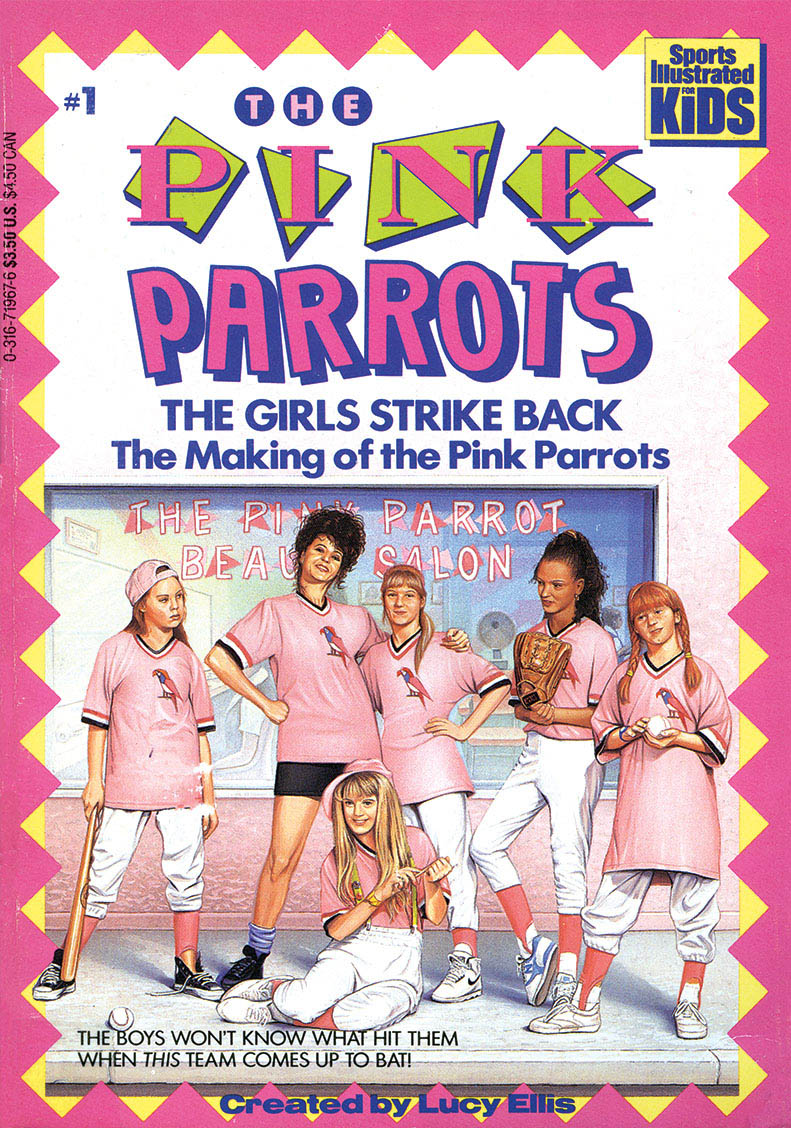

As the ’90s began, series books finally began to routinely portray girls playing sports that had been traditionally considered for boys. Girls playing “boy” sports had come up in earlier teen and tween novels, but most of these early examples involved the athlete learning to act like a lady. For example, in 1989, Sweet Valley Twins #89: Standing Out featured softball star Billie, who learns that everyone (including her parents) like her more after she gets a femme-y makeover and starts referring to herself as “Belinda.” Thankfully, such compulsory femininity barely figured into Lucy Ellis’s Pink Parrots series, published by Sports Illustrated for Kids from 1990 to 1991. This six-book series followed the exploits of the extremely ragtag all-girls baseball team the Pink Parrots, who formed after pitcher Breezy became despondent over the way she was treated as a member of the boys’ team. Pink Parrots is mostly about trying to fit a girls’ sports narrative into the girls’ series mold, so its characterizations aren’t exactly groundbreaking: we have the tomboy! The grouchy one! The ballerina who would rather be dancing! But it also engages with practical issues that come up in the lives of baseball-loving girls, including adults who refuse to make the most of their talents and dudes who say things like, “Girls who want to play baseball just want to be boys.” The series also offers useful tips on how to be a good sport after you kick a sexist boy’s ass so hard he’s just about crying to his mama, which hopefully got some real-world application by readers.

Despite being praised by Publishers Weekly for its “catchy title, splashy cover and colorful cast of characters,” the magazine’s prediction that the Pink Parrots was “likely to be a hit” was, sadly, not in the (baseball) cards for these sluggers.

By the late ’80s, books about friendship for its own sake had become rare and were less popular than series featuring some kind of gimmick. But series about friendship and friendship alone did have the advantage of more space to experiment with concepts outside the YA mainstream than their hemmed-in, schtick-ridden fellows.

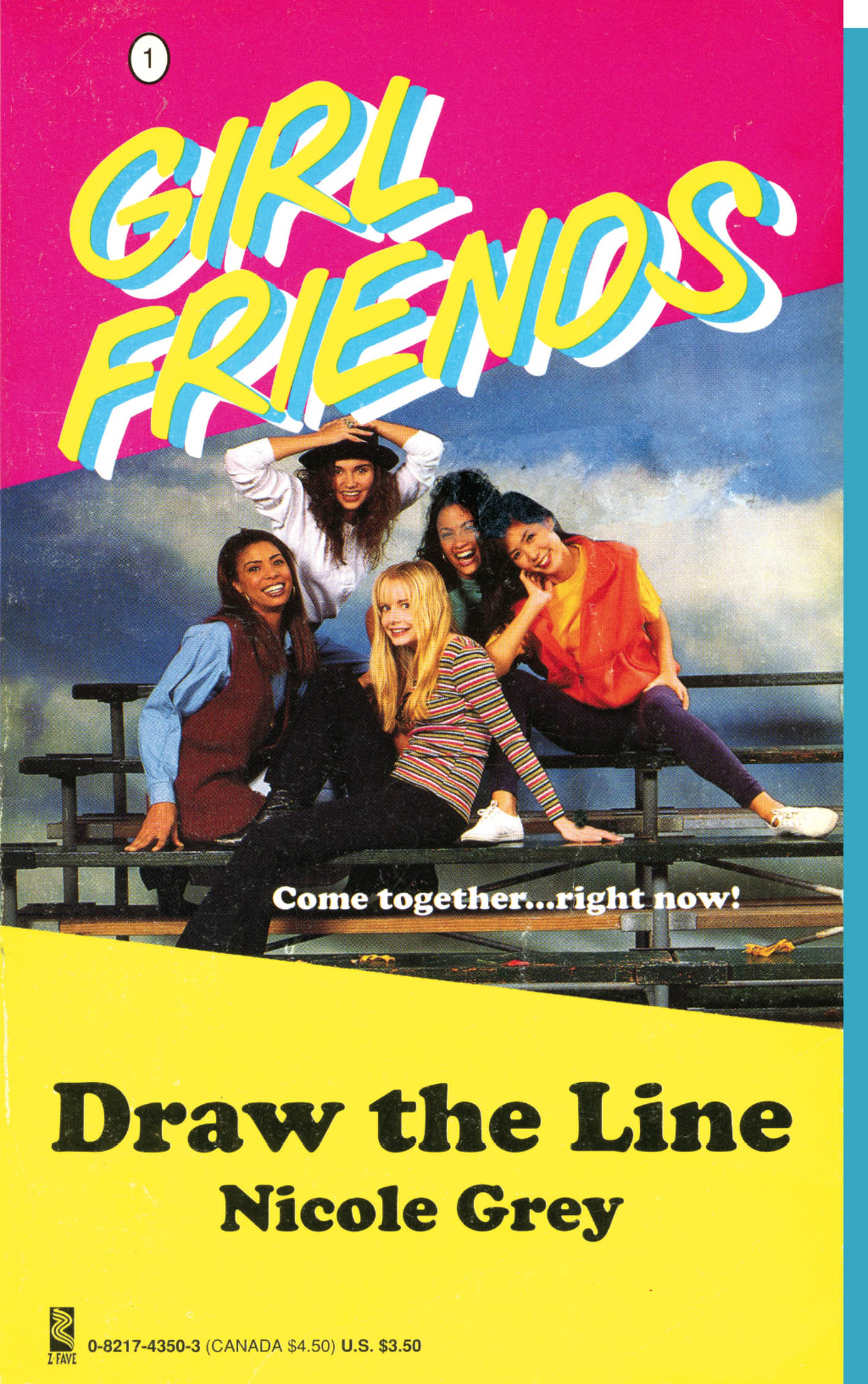

In many ways, the girls of Nicole Grey’s 1993–94 series Girl Friends fit into the YA archetypes we’ve seen before: Cassandra’s the ballet dancer, Maria is the popular cheerleader, Natalie is the one who used to live in the city, granola-chompin’ activist Janis is the Dawn Schafer of the group. But the series combines all this with an ethnically and economically diverse group of girls and social issues. The girl friends of Girl Friends first connect in Draw the Line, at a rally in response to gun violence, which helps confirm that we’re not in Stoneybrook anymore (tragically, this remains a relevant scenario for teenagers). So do the presence of Stephanie Ling, the rare YA heroine whose family relies on her to work long post-school shifts to keep them economically stable, and plotlines about drug-addicted boyfriends, absentee fathers, and abusive relationships. Not to say that the series was perfectly sensitive or never presented any cringe-worthy moments. For instance, Natalie didn’t come from just any city, she lived in Los Angeles, which she fled following the 1992 riots, and she is first introduced tucking her hair into an “X” baseball cap and rapping along with “Baby Got Back.” (Yeesh.) Still, the Girl Friends enjoyed typical moments of teen frivolity—writing school paper advice columns, going on fun dates, shopping, and crushing out on dudes who play in bands. Thus this series proved that the girls who populate serious “issue novels” and the girls who want to look cute at the school dance are, in fact, the same girls. Girls, and the Girl Friends, contain multitudes.

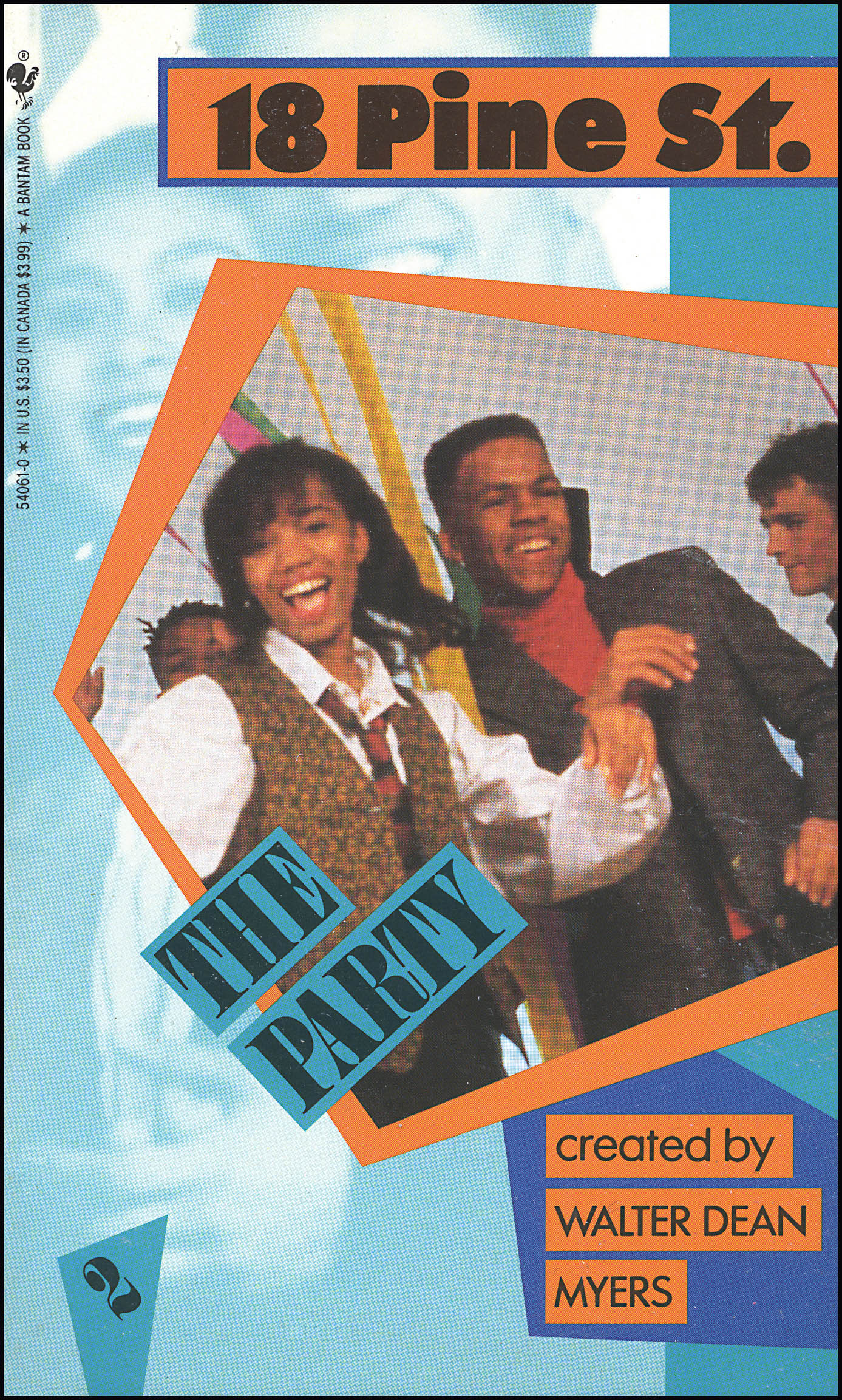

“Walter conceived the series to answer a need in presenting a series about middle-class black teens.”

In some cases, the mere existence of a series could be quietly revolutionary. Though diversity in YA improved somewhat in ’80s and ’90s YA, racial representations were still incredibly far from equal, and people of color most commonly turned up in a series as a member of a predominantly white group (see: Claudia Kishi) or as part of a historical or issues novel specifically about racism. (Not to mention that many of those books were written by white authors.) The 18 Pine Street series, created by YA legend Walter Dean Myers, was one of the first teen series from a major publisher to focus on African American characters. Over the course of twelve volumes published from 1992 to 1994, the series followed the lives of a group of friends who hang out at 18 Pine (a pizza restaurant—don’t let the outdoorsy name fool you). Relatable Sarah, sad rich girl Jennifer, orphan Tasha, cute nerd Kwame, and the rest of the group meet up after class to grab a few slices and chat about classic YA problems, like boyfriend-stealing classmates, false accusations of cheating on a test, competitive frenemies, or the logistics of throwing an enormous rager while your parents are away. Though the mainstream conversation about representation in children’s literature had yet to hit its peak, these characters reflected a life that many tweens lived but that few got to see on the page.

Some authors took the friends-just-hangin’-out series model and gave it the mildest of twists, like Candice F. Ransom’s Kobie Roberts books, straightforward and fairly timeless tales of friendship that happened to be set in the ’60s (a fact totally not represented by the extremely ’80s fashion on the covers, but a fact nonetheless!). Others dolloped on a heavier schmear of schtick, such as Carrie Randall in her six-book Dear Diary series, which ran from 1989 to 1991 and used first-person diary entries to make gentle examinations of tween girlhood a little snazzier (not to mention an illustrated lock and key on the edge of each volume’s cover, to drive home the theme). Lizzie and Nancy, the sixth-grade protagonists, get on each other’s nerves after spending too much time together, have trouble reading, and agonize over whether or not to go to the school dance. It’s fairly mundane, but the same could be said of sixth grade. And some friendship series played it entirely straight, like Susan Smith’s Best Friends series, which debuted in 1988. As the title implies, this series covered a group of best friends who hang for sixteen volumes’ worth of adventures. But what the series lacked for gimmickery, it clearly made up for with drama and intrigue, as evidenced by the title of installment #13, Who’s Out to Get Linda? (One wonders what blackmail-able skeletons a preteen would have in her closet, but who knows, maybe she’s a murderer—kids grow up earlier and earlier these days!)

Besides the 16 books in the Best Friends series, which follow nothing more supernatural than the petty dramas of junior high, Susan Smith also got a little ghoulish in the Samantha Slade: Monster Sitter series (see this page).

The parade of endless gimmicks in friendship books may make all of them look hacky, but if anything, they confirm that (female) friendship is almost endless in its permutations, perennially intriguing, and always worthy of yet another series.

As we’ve established, ’70s YA was about messiness, complexity, and complication, and ’80s YA turned the tide toward the aspirational. But some ’80s books still dared to admit that friendships can suck a big one.

To adults who devote their mental bandwidth to extremely mature concerns like whether to get a “smart thermostat,” YA friendship dramas can feel impossibly distant and/or trivial. But some teenage situations remain relatable for the rest of your life, such as when your best friend gets a new friend you can. not. stand. This eternal dilemma is at the core of Sheila Hayes’s 1986 novel You’ve Been Away All Summer, a surprisingly sophisticated story about evolving friendships. Sarah and Fran have been best friends since first grade—“up until then, in nursery school and kindergarten, we traveled in different crowds”—but in the titular summer before seventh grade, Fran leaves town for two months and Sarah lands a new BFF, the dreaded Marcie. Marcie is rude, irresponsible, in love with a boy who tortures cats, and, in one scene, shockingly racist! The book perfectly captures Sarah’s befuddlement as she tries to understand what it means for her best friend to love this terrible, irritating idiot. Although Sarah and Marcie’s disagreements about appropriate behavior at the natural history museum are (hopefully) of limited use to adult readers, Hayes’s portrait of the fears and oversensitivity present in a shifting friendship remains weirdly (perhaps depressingly) relevant.

Natalie Honeycutt’s Invisible Lissa from 1985 delves into another friendship concern: what happens when a terrible, toxic person worms into your social circle. Debra is not just popular, pushy, and into stealing people’s jumbo novelty pens; she’s also a power-mad lunatic who founds the unappetizingly named FUNCHY Club (it stands for “Fun Lunch,” obviously) as a cudgel to destroy her enemies—which includes Lissa after she is caught gossiping about Debra at the class Valentine’s Day party. Suddenly Debra is smashing Lissa’s class project, picking fights with Lissa’s brother who is literally a toddler, and getting all the other girls in class to turn on her, Crucible-style. Lissa is interesting less for the specifics of its plot (Lissa undertakes a fairly standard middle grade spiritual journey, learning to find worth within herself rather than in invites to funch) than for its examination of the sociopathic underpinnings of a YA character’s drive for popularity. Viewed from a different angle, Debra would probably look like a tween romance novel heroine, dressed in the newest fashions and hell-bent on social supremacy. But in Lissa, she’s revealed for what she is: an annoying jerk who picks fights with toddlers.

Surprisingly, “nice girl befriends borderline sociopath” was a well-populated category of tween novel. Even paranormal queen Betty Ren Wright got in on the action—when she wasn’t documenting the special relationship between spunky teenage girls and helpful wraiths (see this page), she also took occasional stabs at ghost-free realism. In her 1986 book The Summer of Mrs. MacGregor, Caroline Cabot is 12 years old and having a grim summer—her older sister Linda is critically ill, she’s stuck at home with her father while her mother is off helping Linda get treatment, her job’s a bummer—until the arrival of Lillina Taylor MacGregor. Lillina is either a wealthy, married 17-year-old model/photographer who’s hanging around the Midwestern suburbs for kicks or a 15-year-old who deals with her unsatisfying home life by lying about living in New York, being married, and working for Vogue (and also by stealing any money she sees lying around). No spoilers about which is true, but the same empathy Wright brings to the tortured heroines of her supernatural novels pops up here, applied to both narcissistic Lillina and self-conscious Caroline.

Some not-quite-friends stories (admittedly, relatively few) drew upon characters’ disparate backgrounds to create tension. Alice Larsen, the heroine of Marie G. Lee’s 1993 book If It Hadn’t Been for Yoon Jun, is of Korean heritage but was adopted by white American parents as an infant and considers their culture her own. She’s resistant to her parents’ encouragement to learn more about Korean culture and irritated when they suggest she get to know unpopular Yoon Jun, a boy who recently moved to their town from Korea. But a school project about their birth country brings the pair together, and Alice learns not only about Korean culture, but also about treating people with respect (aka exactly the opposite of what her popular-crowd buddies are doing). Lee, founder of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, wrote a novel for adults about transracial adoption, Somebody’s Daughter, in 2005 as Marie Myung-Ok Lee, and her work is some of the first to straddle the ever-thinning line between YA and “prestigious” literature (see sidebar, this page).

But the ultimate X factor in “are we friends or do I actually hate your guts” situations is, naturally, hormonally charged mixed romantic signals in opposite-sex friendships. In Dean Marney’s 1989 novel You, Me, and Gracie Makes Three, Rick and Linda are best friends, even though Linda is a pretentious aspiring artist who swans around in serapes and Rick, well, likes basketball. They seem to hate each other, but is the hate just a cover for something more? The answer turns out to be yes: Linda is in love with Rick and Rick can’t deal, until they have a life-changing experience with a wise, eccentric elderly person named Gracie (making this basically an unauthorized remake of The Pigman by Paul Zindel, the definitive YA text on having your life changed by a wacky elderly person, but with less depth and a happier ending).

However thorny the frenemyship in these novels, most stay just on the safe side of “problem lit.” But a rarefied few touched on actual life-and-death matters, including Ann M. Martin’s extremely dark novel Slam Book. Before we had secret social media accounts we could use to talk smack about our high school classmates without repercussion, slam books—notebooks in which you wrote anonymous gossip about your peers—were quite the sensation, especially in the pages of YA. Slam books catalyzed the action of Judy Blume’s 1972 novel Otherwise Known as Sheila the Great, provided a crucial weapon in the war against Taffy Sinclair (as we’ve seen on this page), and swept through the halls of Sweet Valley High in 1988 (#48: Slam Book Fever). In Martin’s novel, Anna decides she’ll make a slam book to up her social status because, hey, destroying other people psychologically is the best way to become popular in high school. At first, it works: she gets in with the in crowd and is even able to date a cute guy thanks to a slam-book-induced breakup. But slam-book-based happiness isn’t meant to last, and soon tempers flare, Anna and her friends start writing mean things about each other in the book, a slam-book-based prank on an unpopular classmate leads to that girl’s suicide—and then one of Anna’s friends also attempts suicide! Anna’s friend is saved, everyone eventually repents, and they throw the book away, vowing never again to collect cruel anonymous gossip (No one is punished for taunting a girl who ended her life, but maybe that’s realism for you.) Sure, Slam Book is melodramatic, but it also provides a nice rejoinder to baby boomers wailing that the internet is turning innocent kids into vicious bullies. Au contraire; we’ve been monsters all along.