here there are teens, there are love stories. Teenagers and romantic love go together like a drunk person and a six-day-old slice of pizza: it’s a pairing destined to lead only to pain, but you try to keep them apart. Our teen years are when many of us have our first experiences with love (or with horndoggery masquerading as love), a fact that pop culture has reflected since at least the sixteenth century, when noted teenage goofballs Romeo and Juliet made some extremely questionable dating choices.

here there are teens, there are love stories. Teenagers and romantic love go together like a drunk person and a six-day-old slice of pizza: it’s a pairing destined to lead only to pain, but you try to keep them apart. Our teen years are when many of us have our first experiences with love (or with horndoggery masquerading as love), a fact that pop culture has reflected since at least the sixteenth century, when noted teenage goofballs Romeo and Juliet made some extremely questionable dating choices.

But love stories didn’t become a huge part of YA publishing just because l-u-v is in teen culture’s DNA. Romantic stories have been an integral part of every era of English-language publishing, from Samuel Richardson’s 1740 book Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded, to the paperback “dime” novels of pre–Civil War America, such as The Lost Heiress by the phenomenally named Mrs. E. D. E. N. Southworth (yes, her real name was Emma Dorothy Eliza Nevitte Southworth! She was just that lucky!) to the 1940s pulp-fiction boom. Throughout it all, romance novels provided consistent work for female writers in eras when many other professional doors were closed to them. Much like the “throbbing members” chronicled in many a tale of ardor, you just can’t keep romance novels down.

And up they came in the ’80s, when “after years of being deluged with young adult books dealing with the unhappy realities of life, such as divorce, pregnancy outside of marriage, alcoholism, mental illness, and…child abuse, teenagers seem to want to read about something closer to their daily lives,” as the promotional copy for the Wildfire series put it.

In fact, few young readers had “daily lives” like those of these fictional rich white teens from suburban California scrambling to find dates to the homecoming dance, but verisimilitude wasn’t the point. Teens flocked to these books for a taste of glamorous high school life. Meanwhile parents wailed that YA romances were sexist and vapid and might encourage teens to engage in dry humping (some outraged ’rents even got a Wildfire promotional magazine pulled from shelves in 1981).

We’d expect old romance novels to be full of outdated cultural ideas, and the vast majority ’80s and ’90s teen romances are—few meet modern standards of healthy relationships, diversity, sex positivity, or proper shoulder-pad deployment. Yet many others are more progressive than you might expect, with more realism, egalitarian relationships, and empowered heroines than those pastel covers imply. Yet no matter where they fall on that continuum, these books were beloved by teens. As an academic paper presented at the 1984 annual meeting of the International Reading Association soothingly noted, “teachers may safely and enjoyably put a little romance into their reading programs.” Let us, then, safely—maybe even enjoyably—swoon into the world of YA love stories.

If you picked up a Wildfire book today, it wouldn’t immediately stand out among other ’80s romance novels. Their titles and tag lines aren’t intriguing, and their cover models often sport awkward facial expressions that suggest they’ve just been told that their photo is going to be used in an ad for super-absorbent maxi pads. But this wasn’t because Wildfire didn’t know how to stand out in its field; rather, Wildfire was creating the field as the first teen romance series of the decade.

Series romance—so called because each book was branded similarly so that readers knew what to expect—had been around for grown-ups for ages, and by the mid-1970s, Harlequin was printing up to 150 million titles a year in the wish-fulfillment genre. They had existed on a smaller scale for teens in the ’40s and ’50s in malt shop books like Janet Lambert’s Penny Parrish novels and Anne Emory’s Dinny Gordon. But it wasn’t until the beginning of the ’80s that publishers began marketing series romances directly to the braces-and-acne crowd. After noticing that romance selections for their teen book club, like 1978’s Sixteen Can Be Sweet, always sold well, Scholastic created Wildfire in the hopes of capturing a similarly broad, if much younger, audience.

Wildfire was different from other standalone romances precisely because it traded on consistency. Although each volume was a self-contained story with its own cast of characters, it delivered certain similarities: an “average” teenaged girl dealing with a minor problem, like trouble with a teacher or lack of confidence; an appealing boy; no sex; no controversial content; and a happy ending. Even the covers looked similar to be easily spotted on a bookshelf or from across a store. Wildfire’s advertising touted this sameness with slogans like “Every Young Girl’s Dream of Love” and suggestions that if you liked one Wildfire book, “you’ll love all the other Wildfire girls. They’re a little bit of you!”

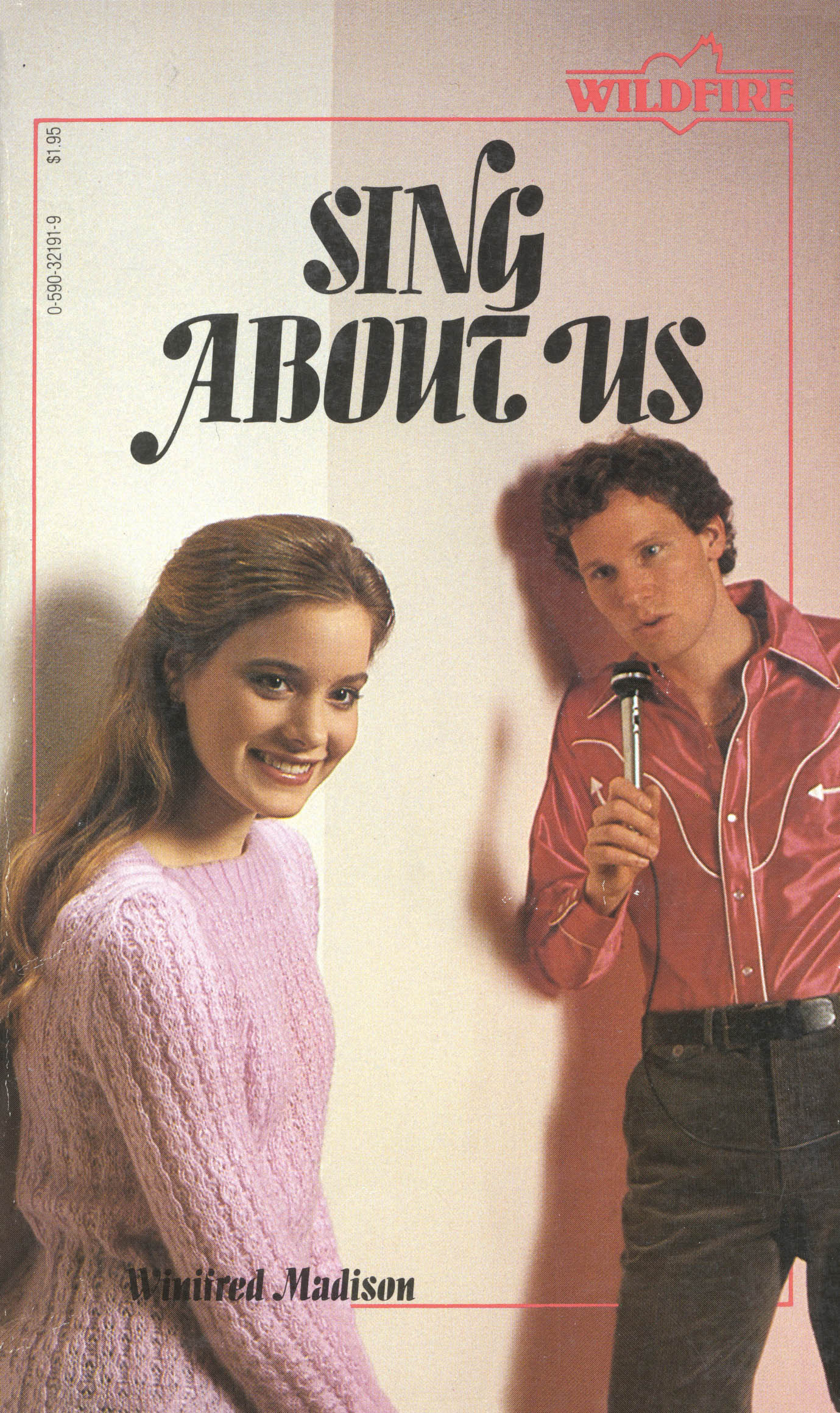

While “grown-up” romances of the late ’70s and early ’80s mostly had illustrated covers, YA romances of this era favored photos (and, apparently, turtlenecks), with couples who bravely stared down the reader instead of making bedroom eyes at each other.

The branding worked: after Wildfire #1: Love Comes to Anne by Lucille S. Warner, was published in late 1979, the series caught on like, uh, wildfire. By 1982, Wildfire books had sold 2 million copies.

After witnessing Scholastic’s unprecedented success with Wildfire, rival publisher Random House kicked off its own teen romance series, Sweet Dreams, in 1981. Sweet Dreams was also an immediate hit, with first print runs numbering 150,000 copies (to get a sense of how enormous that is, consider that The Fault in Our Stars, a 2012 novel by award-winning and then-already-successful author John Green, had a first print run of 150,000 copies). Where Wildfire cover girls often struck G-rated poses with male models, Sweet Dreams covers generally kept the sensuality threat level hovering somewhere between “cold fish” and “my dad makes me wear special chastity underpants” by depicting the heroine solo, with no boy in sight. Though none of these series’ covers promised a Wuthering Heights for the Orange Julius generation, the models’ habit of making eye contact with the reader helped convey that these were not your mother’s romances. Typical romance cover models coyly averted their gazes, but these girls telegraphed that they were ready and willing to go after what they wanted.

With these two juggernauts leading the pack, a torrent of series about good girls in love followed: Sunfire, Wishing Star, Caprice, Windswept, Magic Moments, Two Hearts, Young Love, and First Love, among others. (Historians have yet to weigh in on why all ’80s YA romance series names sound like brands of sensual massage oil.) Though some series put their unique spin on the format—Windswept had a mystery element and occasional ghosts, magic, and other supernatural threats, Wishing Star heroines dealt with personal problems like divorced parents or substance abuse, and Sunfire focused on a different girl in a different historical era in every volume, like a (slightly) sexier American Girl—they all aped Wildfire in pumping out stylistically similar but unconnected teen romances published with shocking frequency. Some series slapped new cover art on older books and published them as though they were brand-new, like Wishing Star’s drinking drama The Lost Summer, which originally came out in 1977.

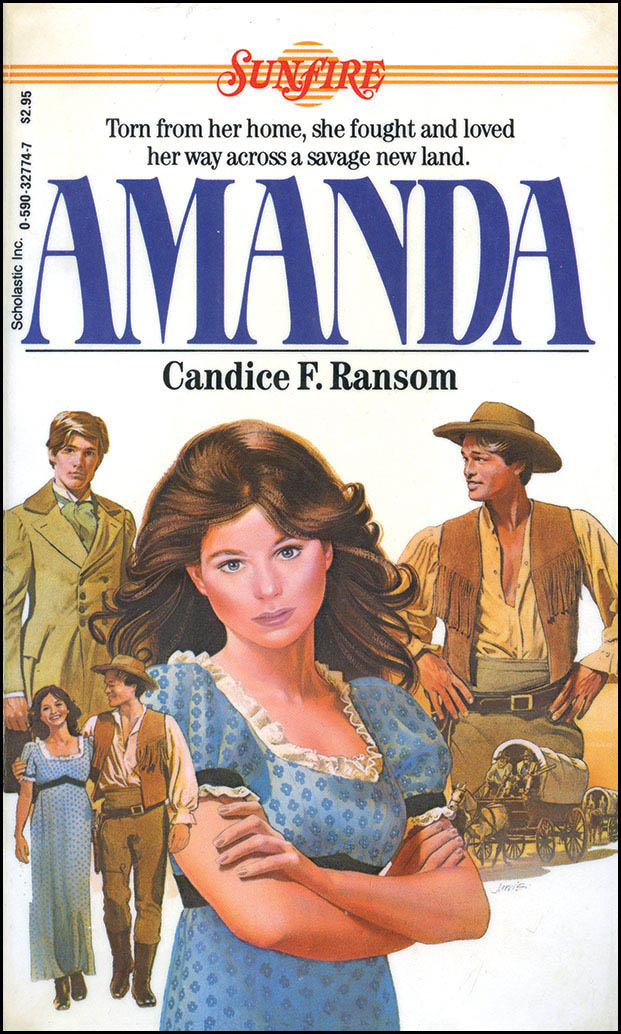

Sunfire was one of the few ’80s romance series that used illustrations instead of photos, possibly because the covers featured not only the heroine (in a fancy dress to boot), but numerous other characters and other period-appropriate accessories (like a covered wagon) that would be simpler (and cheaper) to draw than to shoot.

Some of these series only ran for a few volumes, but Wildfire bopped along until 1986, racking up an impressive 82 volumes. That number is dwarfed by the more than 250 titles Sweet Dreams put out before closing up shop in 1995, or the mind-boggling 236 titles First Love released between 1981 and 1987, before it was swept aside so that the market could be flooded with Sweet Valley High clones like Couples.

But while some folks might dismiss Wildfire as totally regressive and full of implications that teen girls should care only about dating, a closer look reveals something else. As scholar Carolyn Carpan wrote in Sisters, Schoolgirls, and Sleuths: Girls’ Series Books in America, “rather than teaching girls to focus on love, marriage, and the baby carriage, many teen romance novels taught a generation of teenage girls that they could have it all—marriage, children, and careers.” Sure, some Wildfires are pure ’80s schmaltz (1982’s Sing about Us, with a plot twist that hinges on a sexy belly-dancer costume!). Some have achingly punny taglines, like Jesse DuKore’s The Boy Barrier (“Is tennis the only game she knows how to play?” Judging by how she’s holding the racquet, I’m not confident she’s even got that down.) But some Wildfires—like Nice Girls Don’t, a 1984 volume by Caroline Cooney (who worked on dozens of series before writing The Face on the Milk Carton)—went so far as to turn feminist subtext into full-on text. Nice Girls follows Tory, a high school athlete fed up with both her school’s sexism toward the girls’ basketball team and society telling her she’d be a whole lot cuter if she didn’t think so darn much. Tory isn’t an innately confident and driven firebrand; she’s confused, conflicted, and scared, as both the adults around her and her awful boyfriend Kenny suggest that she should give up on her quest for equality and take up a better hobby, like smiling vacantly. Nice Girls accurately captures the terror and exhilaration of standing up for what you believe in for the first time, and even Tory’s romantic dilemma (hook up with progressive, supportive Jonathan, or stick with Kenny, who doesn’t want women to drive even though it is 1984) reflects the deeply personal journey she’s on.

Everything about these covers was designed to show readers that these weren’t their mothers’ romance novels—from the extremely Pat Benatar headband to the models’ poses (not to mention the nearly entirely cropped-out boy figure) that just barely hint at sexuality. Unlike ’80s adult romances, which often did far more than hint at horniness, there’s no lust-sodden gazes to be found here—just a thousand-yard stare at the reader.

“The stories took on some serious issues, but they were handled gently, and the emphasis was on clothes and boys and best friends. The difference? Girls had stronger roles in our books. My editor believed in strong female characters. They didn’t wait for some boy to rescue them; they were able to stand on their own two feet.”

—CANDICE RANSOM, author of Thirteen, Sunfire, Windswept, and First Love titles, on ’80s teen romance heroines

Despite being romances, a vast number of these books explore the pitfalls of relationships as much as the highlights, suggesting that dating for status is a soul-killing endeavor, that the popular jock you lust over might actually be a total buzzkill once you get to know him, and that romance is about respect and compatibility, not the buzz of smooching the captain of the football team. (For context, recall that even the 1985 film The Breakfast Club, which was far hipper and “edgier” than any of these books, suggested that women might be happier if they stopped being so weird and just wore a nice headband.) These weren’t merely naive books that pretended that teen sexuality stopped at French-kissing; they were also fresh formulas infused with the lessons of second-wave feminism.

Under the Covers

Writing for a YA Romance Series

How did all those Sweet Valleys, Wildfires, and other series arrive on Waldenbooks shelves week after week in the ’80s and ’90s? Did writers create their own plots, or was every twist planned by publishers? How did you even get a job writing them? What was it like to be part of a major YA literary phenomenon? To find out, I spoke to three accomplished authors who cut their teeth writing series YA: Candice Ransom (who worked on Sunfire, Boxcar Children, and more), Rhys Bowen (who wrote as Janet Quin-Harkin for Love Stories, Heartbreak Cafe, and more), and Caroline Cooney (who worked on Wildfire, Point Horror, and more).

RANSOM: I’d been trying to break into children’s books since 1978 or so. Mind you, I knew I wanted to write for children since I was 15 and actually began that summer, writing a middle grade novel and submitting it to Harper and Row. By 1980 or 81, I’d tried “writing to trends,” the result being a dismal YA-ish book about a boy who played Dungeons and Dragons. It was a disaster.

Then I found in Writer’s Digest magazine a call for proposals by Ann Reit, editor at Scholastic, for [Wildfire]. I wrote three chapters and an outline for a romance book with little romance. Amazingly, Ann Reit called me on the phone. She didn’t like that proposal, but she liked my writing. She asked if I’d consider writing a proposal for a new imprint of romantic suspense for teens called Windswept. This I could do. [That book,] The Silvery Past was published in 1982. From then on, I had a working relationship with Ann, who took me under her wing and taught me almost everything about writing and working with an editor.

I had so much fan mail that I devoted every Saturday to responding. Sometimes I’d get “class” letters, a letter from every student in a class, but the majority of my mail came from girls….I also did many mall bookstore signings. Sometimes I’d have kids who’d already read my books waiting in line. And once, an intrepid bunch of girls found out where I lived and came to my house! It was great fun.

BOWEN: I had absolutely not considered writing YA before my agent asked me to. In fact, the whole YA genre hardly existed in 1980 when I wrote my first book. Mine was one of the books used to launch the Sweet Dreams line that suddenly made YA books popular. Before that, books for kids were bought by school libraries and adoring aunts. This was the first time that teens could buy their own books and dictate what they wanted to read. So I was right at the beginning, writing hugely popular books.

When I was asked to write “a teenage novel” I didn’t think it was me. But I started writing, first person, and the voice just came to me. I was amazed how easy and fun it was.

Those early days of Sweet Dreams were very heady. We were celebrities. We got zillions of fan letters and if we went to a store, we were mobbed by teenage girls. Restrictions were that the books had to be wholesome. No graphic sex. But my heroines did have real-life problems: divorced parents, friends who were drinking too much. Essentially a slice of real life, but usually with a happy ending.

[The best part of writing series YA] was that I reached a huge number of readers, some of whom wrote to tell me they had never read a book before. The worst was snooty criticism from people who put them down as not being Jane Eyre. My comment was always that these readers would never have read Jane Eyre, and now they might because they had discovered that reading was fun. Another worst for me was the pressure to perform. My books were so much in demand that I couldn’t write fast enough.

COONEY: Ann Reit, an editor at Scholastic, read a short story of mine in Seventeen magazine, and asked me to turn it into a paperback original teen romance. This was [Wildfire title] An April Love Story….Later on, I began to write books for her by assignment. For example, she wanted to do a cheerleader series; she chose the names and circumstances of the girls and their friends, and I came up with the plots, about which we conferred and argued. I then wrote an outline, something that is difficult to do, because a book often takes on a shape of its own while you write. But in a series like this, you need to stick to the outline and that is terrific training.

I wrote books 1, 3, 5 and a few others [for Cheerleaders]. [The series] came out monthly, so several authors were involved. That meant your outline would affect the outline of the next book, which somebody else was writing. You also couldn’t use a story-line another author had picked, so there were many conferences. I loved this. I think it is like architecture, where you design the best house you can, given the parameters of site, money, owner’s needs….There was complete freedom in the sense that it was my book, my dialogue, my morality, etc. But I would always thoroughly discuss the theme and plot with Ann first.

[Writing series books was] the best possible training. I’ve written over 90 books now and I credit my experience with series, a having to write fast and on demand and to order, as it were.

One of the greatest perks of adulthood (besides having the freedom to speak your mind, pursue your own interests, and eat five Stouffer’s French bread pizzas in a single sitting) is never having to experience first love ever again. Sure, first love has its moments, and those pics of you and your prom date standing in your driveway remain totally adorable. But overall, first love tends to yield ten dramatic personal ultimatums delivered in a Wendy’s parking lot for every one unforgettable evening spent looking at the stars. It’s a bad deal.

But ’80s YA books about first love put a gloss on things. In these fantasies of uncomplicated youth, trauma was minimized, hijinks were maximized, and everyone found someone to smooch. Sure, characters broke up (usually temporarily), fought (usually about nothing), and waded through obstacles, but all parties ended up happily partnered off by the end of the 150 pages. Though these books hit the same marks overall, they do so in different ways, and most of them end up falling into one of three major categories: Wacky First Love, Realistic First Love, and Soap Operatic First Love.

What qualifies as a Wacky First Love story? Well, how are ya doing on quirks? Does the heroine have some kooky thing she can’t stop doing, like falling over her own feet? That’s the case in Alida Young’s 1986 book Megan the Klutz, in which the heroine is so absurdly clumsy that she cannot enjoy even a simple slice of pizza in front of her crush without getting cheese everywhere, tripping on a stray slice of soppressata, and, I assume, ending up trapped inside a meat locker.

Failing that, the heroine could have an adorable quirky problem, like Amy, the protagonist of R. L. Stine’s 1989 masterwork of teen romantic doofiness, How I Broke Up with Ernie. Amy wants to call it quits with Ernie. But due to a robust mix of her own indecision and Ernie being about as smart as a box of Nilla Wafers, it takes the whole damned book for her to pull it off, which leads to kooky scene after kooky scene of Ernie not realizing he’s been dumped, even after Amy takes up with a new guy. (Maybe Ernie should try to date Megan the Klutz instead. She seems nice!)

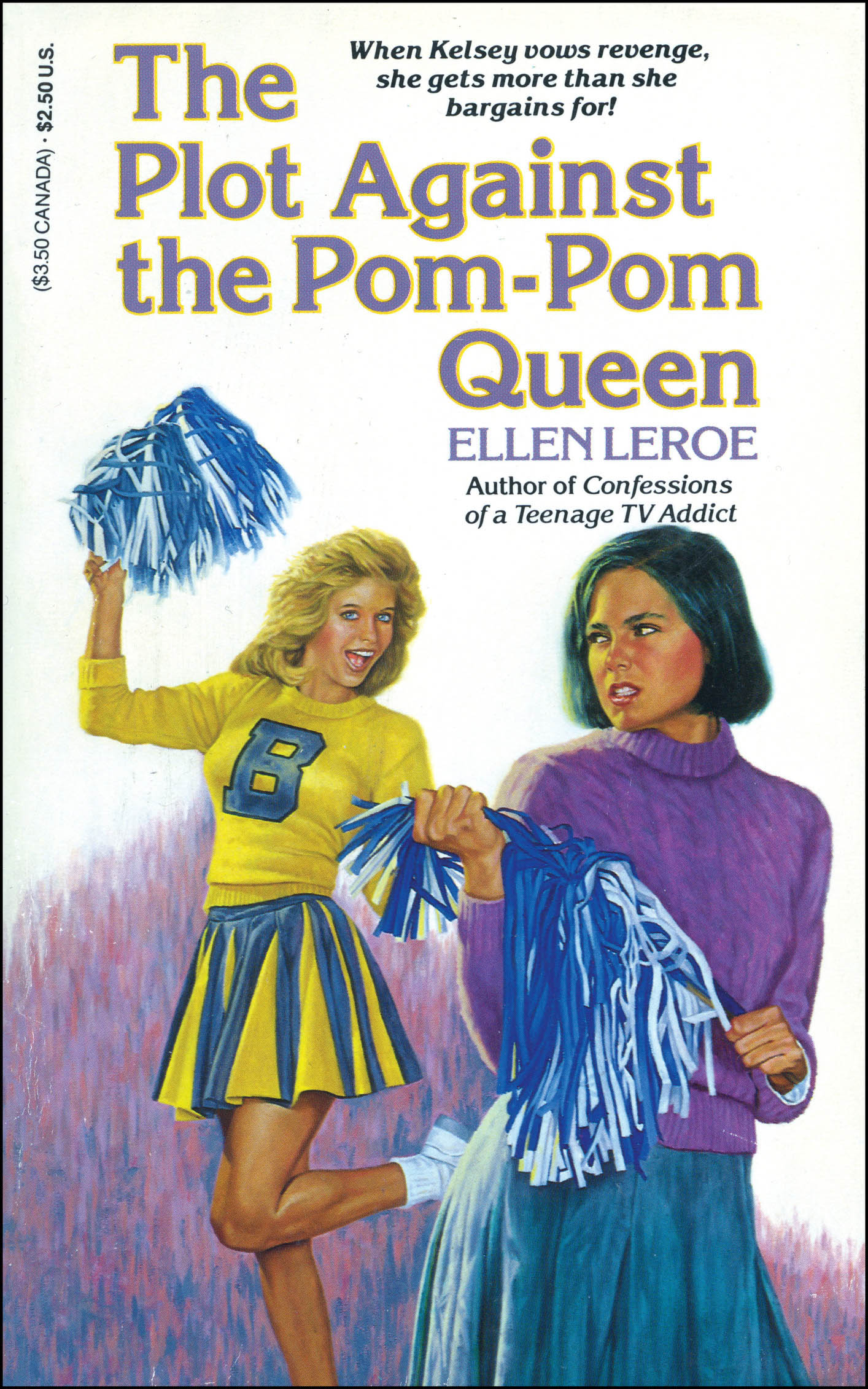

But heroines who don’t have a habit of being dumb or charmingly falling on their face into a pile of meat-garbage can still be wacky. They just need a scheme, like the ones found in Ellen Leroe’s 1985 book The Plot Against the Pom-Pom Queen. Nerdy Kelsey crafts an elaborate plot to hook up with hottie Cal Lindsay, a jock who is “so sexy that girls under 17 would not be admitted to his classes without an accompanying parent.” But rest assured, there is also a plot against the titular pom-pom queen, Taffy Foster, which involves getting Kelsey a makeover and utilizing something called a “Magical Male Grabber” (it’s just a dating guide, get your mind out of the gutter). Wackiness abounds!

A cover blurb from the New York Times was a rare occurrence for teen paperbacks in the days before Sweet Valley High broke onto the best-seller list (and way before the post–Harry Potter creation of a designated children’s best-seller list), but Ellen Conford got a glowing write-up for this title (save for the lukewarm response to the collection’s titular story). Whether or not an endorsement from the paper of record actually made a difference to discriminating young readers is hard to say.

If you seek a book with a tamer scheme that still retains some wackiness, try Eve Bunting’s 1983 novel Karen Kepplewhite Is the World’s Best Kisser. The 13-year-old Karen plots to go from never-been-kissed to expert smoocher in the time before she throws a boy-girl party, which is to be attended by the extremely kissable Mark. Karen works towards her goal in a classic Wacky First Love fashion, practicing her make-out technique on inanimate objects and trying to understand the mysteries of romantic attraction in the run up to the big party, where everything turns out okay, as it always does.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are Realistic First Love stories, which dispense with schemes and quirks in favor of truthful emotional storytelling—and therefore don’t always read as love stories at first blush. Ellen Conford’s 1983 first-love-focused collection of short stories, If This Is Love, I’ll Take Spaghetti takes on familiar scenarios like being let down by meeting your celebrity crush and a young girl’s unhealthy fixation on her weight as the thing holding her back from true love, but because each story is only a few pages long, there’s not much space for nuance.

But when Realistic First Love stories are executed powerfully, the end product is often a classic coming-of-age tale that just happens to include a romance. For instance, Marie Myung-Ok Lee’s outstanding 1992 book Finding My Voice, which she published as Marie G. Lee, tells the story of high school senior Ellen’s romance with classmate Tomper—against a backdrop of college admissions worries, her strict Korean immigrant parents, and the small-town racists who assault and abuse her. But it’s ultimately Ellen’s relationship with Tomper that not only drives the plot but provides a skillful portrait of the intricacies of first love, while still addressing (and not sugar-coating) the realities faced by an Asian American teenager.

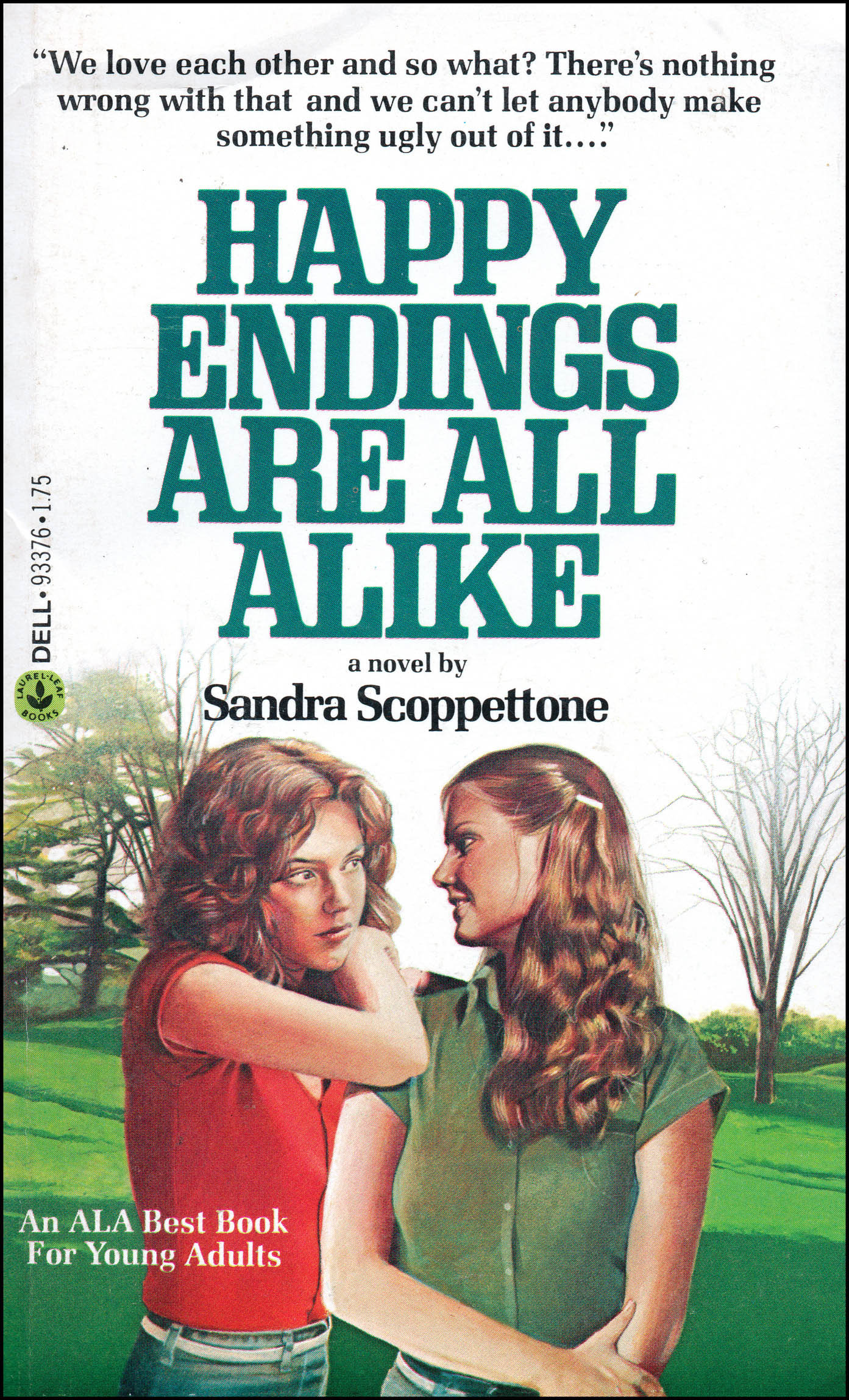

Lee’s book wasn’t the only one of the era to use a tender love story as a backdrop for groundbreaking work. Queer teen love stories had begun to emerge in the late ’60s; John Donovan’s I’ll Get There, It Better Be Worth the Trip, published in 1969, is generally considered the first YA book to include queer romance, in the form of a same-sex kiss between the hero and his male friend. As you may recall, 1969 was the year of the Stonewall riots and thus not exactly a high point of tolerance, and so the book’s editor, the storied Ursula Nordstrom of Harper & Row’s Department of Books for Boys and Girls, solicited prepublication blurbs from experts on childhood development and sexuality to confirm that, you know, gay teens exist. Still, even with the astonishingly progressive intent behind it, I’ll Get There isn’t exactly sunshine and rainbows: when the hero’s beloved dog is killed, he concludes it was cosmic punishment for messing around with another guy. Other early same-sex romances, like Sandra Scoppettone’s Trying Hard to Hear You from 1974 and Happy Endings Are All Alike from 1978, feature similar sadness. In Trying Hard to Hear You, one of the boys in the novel’s gay couple dies in an accident, and in Happy Endings, although lesbian couple Jaret and Peggy are well-adjusted and their families work hard to understand and accept them, Jaret is nevertheless sexually assaulted by a bigot.

Midcentury pulp novels about women lovers were notorious for unabashed and sensationalistic taglines, no doubt written with their male readership in mind. But here, the cover takes that traditional frankness and subverts it for a young, female reader: rather than play up the scandalous-slash-sinful nature of the relationship, it literally says “so what? There’s nothing wrong.”

But one of the most celebrated LGBT romances came later, in 1982. Annie on My Mind by Nancy Garden was not, as many assume, the first YA romance between two girls—that honor is generally accorded to Rosa Guy’s 1976 Ruby—but it was one of the first in which no violence or major sorrow befalls the queer lovebirds. Wealthy Liza and working-class Annie meet at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and fall hard for each other. And though their love is not without road bumps—homophobic school administrators attempt to have Liza kicked out (and succeed in getting two lesbian teachers fired), which leads Liza to temporarily dump Annie—the heart of the book isn’t their trauma; it’s the flush of first love captured in lines like, “The first day, I stood in the kitchen leaning against the counter watching Annie feed the cats, and I knew I wanted to do that forever.” It was the first YA book to afford two girls in love the same sweet, rose-tinted realism granted to countless hetero couples (the Kirkus review of Annie opens with “Talk about meeting cute!” before going on to describe it as “a soupy romance”). In the end, Annie and Liza get that happily-ever-after that their predecessors were denied; the book’s final words are “‘Oh, god, I love you, too!’” Soupy, maybe, but also far more realistic in showing that not all queer love stories end in pain and heartbreak.

As Annie reprinted throughout the later ’80s and early ’90s, each new cover design gradually brought the girls closer and closer together, to the point of (gasp!) holding hands. Meanwhile, the earlier Ruby takes an angsty approach without even a whiff of romance.

Interestingly, for all the realism in these queer Realistic First Love stories, some of the covers opt for abstraction over specificity. The covers of I’ll Get There and Ruby don’t come close to suggesting a love story within, and while this is not necessarily a closeting, conscious choice, the artwork does afford the books enough invisibility to slip past conservative parents or librarians and into the hands of kids who needed them. With its “We love each other and so what?” cover line, Happy Endings took a bold step forward upon its publication in 1978,the year the LGBT pride flag was first flown. But just four years later, Annie, with its relatively unassuming cover, became a lightning rod for challenges and bans. (Granted, book banning became a much bigger phenomenon in the ’80s than it had been in the past.) Garden’s book was even burned in 1993 in Kansas by parents who wanted it removed from a school library, leading to an expensive, multiyear court case involving the ACLU that resulted in the book staying on shelves.

But maybe realistic love isn’t your thing. Maybe you want a first love tale so absurd, so deranged, so full of pouty rich people and faked deaths that the librarian checking it out for you will roll her eyes. If this sounds like you, what you want is a Soap Operatic First Love story.

Many authors wrote soap operatic YA love stories in the ’80s, but the soapiest had Francine Pascal’s name stamped on the cover. The Caitlin series follows blazer-wearing rich girl Caitlin as she tries to negotiate her blazer-wearing first love while drunk on her own power (and surviving the nonstop plot twists that were synonymous with ’80s Pascal).

The Caitlin books, which ran as a set of three trilogies (Loving, Promises, and Forever) published between 1985 and 1988, chart a decade or so in the life of the beautiful, terrible poor little rich girl as she repeatedly breaks up and makes up with her first love, Montana-based hunk Jed (Jed!), rides many horses, drives many luxury cars, is emotionally neglected by her family, accidentally lets an elementary schooler eat poison (it’s okay, he survives, everyone calm down!), gets trapped in a mine, reconnects with her long-lost father, goes to college, is forced against her will to become a successful model, gets trapped in a barn fire, is forced against her will to become the head of a successful mining company, and is the subject of numerous unsuccessful plots by evil men who wish to “ruin” her.

Yes, these plots cover a lot more ground than mere first love. But at the end of the series, after all those implausibly wild rides, Caitlin has evolved from a wild, selfish monster to a boring and settled-down young woman in a long-term relationship. The only drama in the final volume comes courtesy of a surfing injury and a morally compromised race horse jockey. (You used to be the terrible girl with evil destructive plans, Caitlin! You used to be fun. We’re lucky we never had to see Jessica Wakefield laid so low.)

Caitlin’s “long black hair, her magnificent blue eyes and ivory complexion” were the first things readers learned about the character in an introductory letter from Francine Pascal at the end of Sweet Valley High #18: Head Over Heels.

Marie Myung-Ok Lee on her Journey to Publication

In 1992, Finding My Voice (this page) became the first teen novel released by a major publisher with a contemporary Asian American protagonist by an Asian American author. Written by Marie Myung-Ok Lee as Marie G. Lee, the book won awards from the American Library Association and the International Reading Association, but publishing it was a struggle. “My agent was sending it out for over a year, I think,” Lee told me. “A lot of [responses were], ‘Oh, we just published somebody from Asia.’”

Lee started writing Finding My Voice without knowing much about children’s publishing. “I wasn’t 100 percent sure that it was a YA novel,” she told me. “I thought it might be more of a Catcher in the Rye type of thing.” But once she began submitting the book to editors, she found that the rejections focused not on genre but on race. “I think a lot of people found the very bald treatment of race in Finding My Voice to be off-putting,” said Lee; the book deals frankly with heroine Ellen Sung’s abuse by small-town racists, among other tough topics. “Nobody was really doing that then, so that made them uncomfortable…and that was why people passed on that book.”

Publishers at the time had made superficial nods to diversity in YA (like including a single person of color in a series filled with white characters), but most books centered on young people of color were historical fiction, like Sook Nyul Choi’s 1991 novel about the Japanese occupation of Korea, Year of Impossible Goodbyes. As a result, few novels released by major publishers focused on the experience of being a teen of color in contemporary America, not because no one was writing these stories, but rather due to publishing constrictions. “Ethnic literature [at the time] would just be the person being ethnic, as opposed to, the person could be ethnic and talking about what it’s actually like being ethnic,” Lee said.

Lee eventually found a home for the book, and “it was kind of in retrospect that people thought the book was groundbreaking.” She also received criticism from individuals who thought that Ellen’s strict parents were too stereotypical. Breaking ground means dealing with everyone’s expectations: “I think when it’s the first one,” Lee said, “everyone wants to attack it, or it’s never what you want.”

Most ’80s and ’90s YA romances were uninterested in taking risks with the formula; when you cracked open that aqua-and-hot-pink cover, you could count on a girl, a boy, and a series of small-yet-dramatic obstacles to their finding love. But a handful took a leap into weirdness, and got downright avant-garde as they did it.

The Choose Your Own Adventure series became an instant hit when it launched in 1979. Finally, the power to decide the circumstances of your own gruesome death was in your hands! The books’ success revved up an army of knock-offs, from direct clones like the Twistaplot series to the Find Your Fate books, which allowed kids to create their own licensed merchandising adventure with Indiana Jones, Jem and the Holograms, or G. I. Joe (To glamorize the military-industrial complex, turn to this page!). But the trend also led to a handful of books that kept the choose-your-fate framework while doing away with the adventure element entirely. Who needed to choose to dodge bloodthirsty reptiles who hungered for your tweenaged meats when you could…try to figure out mundane high school dating problems?

Each Make Your Dreams Come True cover featured a photo of the heroine encased in a necklace chain, but unlike other YA covers with lockets (see this page), the jewelry wasn’t there to symbolize anything, ahem, racy.

Dream Your Own Romance (1983–4), Follow Your Heart Romances (1983–5), and the Make Your Dreams Come True series, which ran for only a single year in 1984, plopped you, the reader, down into the semirealistic lives of perky, heterosexual teen girls dealing with perky, heterosexual teen girl problems. For example, in Make Your Dreams Come True #3: Worthy Opponents, you’re a popular high school junior named Jill (of course your name is Jill) who has to decide whether she wants to run for class president, manage the school hunk’s campaign, attend a party alone, take vengeance on a school mean girl, and so on. To wit: “If you think Jill decides to go to the writers’ conference, go to this page. If you think Jill decides to stay home, go to this page.” Whoa, slow down there! You’re trying to tell me I can experience the thrill of participating in school government and the wild, illicit high of deciding whether or not to attend a conference? All in one book? Understandably, this trend didn’t last long—which is a shame. We never got to find out if Jill’s secret admirer was a bloodthirsty reptile.

Another ’80s trend to enjoy an awkward, brief romance with YA love stories was the body swap. Beginning in the ’70s and continuing into the ’80s, cinematic depictions of these comedic mix-ups were inexplicably popular, and filmmakers had tried swaps between mother and daughter (Freaky Friday), father and son (Like Father, Like Son; Vice Versa), grandfather and grandson (18 Again!), teenage boy and random old man (Dream a Little Dream), and Steve Martin and Lily Tomlin (All of Me). But until Susan Smith’s novel Changing Places, no one had dared to do a body swap between a teenage girl and the boy she tongue-kisses.

Changing Places is a book that dares to ask the incredibly 1986 question, “What exactly are computers—like, are they magic boxes that can force you to switch bodies with your boyfriend?” For all-American teens Jenny Knudsen and Josh Friedman, the answer is a resounding yes! Due to the whims of some kind of cranky technological god, the pair of lovebirds have their bodies swapped while using a computer (trust me, it makes even less sense when you have all the details). Each is condemned to live as the other for a week, gaining knowledge of how the other half lives while also taking constant, scrupulous care to never look at the genitals on their new body, even though that’s probably the first thing any of us would do in this situation. Since Jenny and Josh refuse to look at their new junk, they have time to focus on growing emotionally, and when they finally switch back, they understand that everyone has it hard, that a lot of their miscommunication was due to gender stereotyping—and that they are probably the only people on earth who would switch bodies with their partner and not fool around once. Maybe they are destined to be together!

Unlike R. L. Stine’s horror novels, Phone Calls features the title—not the author’s name—in large type, positioning the concept as the main hook. Similarly, the “author of” tagline mentions his rom-com How I Broke Up with Ernie (see this page) rather than the creepy-crawly backlist for which he’s best known. For a similar pinked-up cover for a novel written by a horror author, check out Christopher Pike’s entry in the Cheerleaders series (this page).

But some literary experiments of this era were sui generis forays into a genre apparently created just for the hell of it, like 1990’s bizarre R. L. Stine jam, Phone Calls. Before he became Stephen King for the retainer-wearing crowd (see chapter 7), Stine wrote teen romances, and he continued to write them well into his tenure as the unquestioned lord of mall-based terror; in fact, he was already six volumes into Fear Street when Phone Calls was published. What makes this book unusual? The entire narrative is, you guessed it, phone calls between friends, would-be lovers, and callous racist caricatures (the less said about Ramar, the exchange student and “weirdo extraordinaire,” the better). Yet more perplexingly, the back cover copy implores us to “Reach Out—and ZAP someone!,” whatever that means, and slanders poor Julie with the ultimate high-school neg, calling her “about as intriguing as algebra.” (Better go to the school nurse for that burn, Julie!)

In theory, this is a unique, entertaining way to tell the very basic story of friends slash frenemies Julie and Diane, who get involved in an escalating war of prank phone calls and set each other up on a series of fake dates with boys at school. In practice, though, the book plays out as an avant-garde literary exercise pitched midway between Sleepover Friends and William Gaddis’s JR. (Sample dialogue: “Hello?” “Hello, Mick? Do you know who this is?” “Huh?” “No? You’ll have to guess.” “What?”) Reader beware! You’re in for a book that innovates in a change-resistant field but doesn’t break new ground in dramatizing the teenage psyche.

Before the Golden Age of YA, teens could learn about sex in precious few ways: progressive parents; an older sibling or friend; The Canterbury Tales; a pile of water-logged pornographic magazines found in the woods; or, most ill-advisedly, trial and error. But one place you definitely couldn’t learn about sex was in early teen books (no one has written Nancy Drew & the Mystery of Getting on Birth Control without My Dad Finding Out, after all).

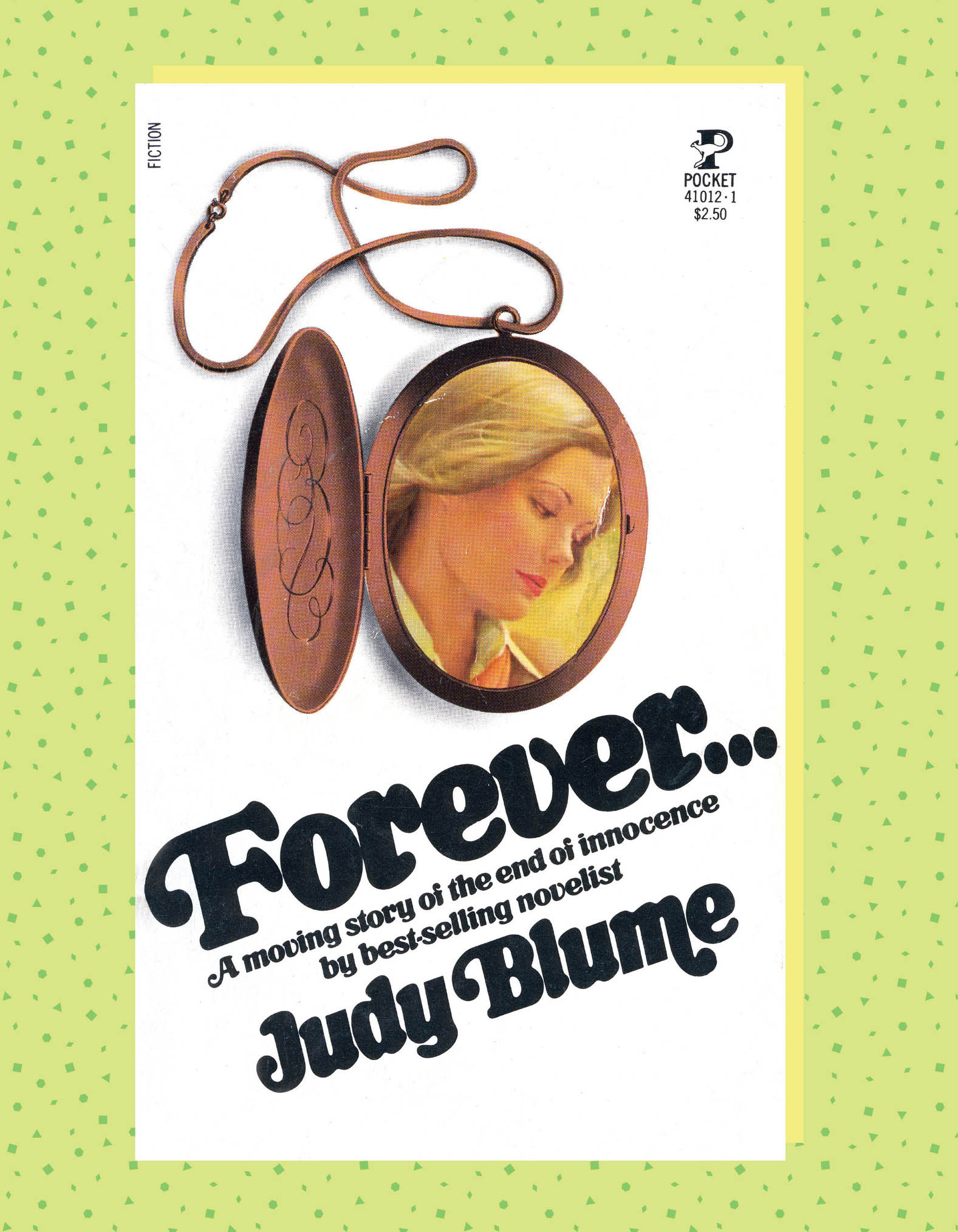

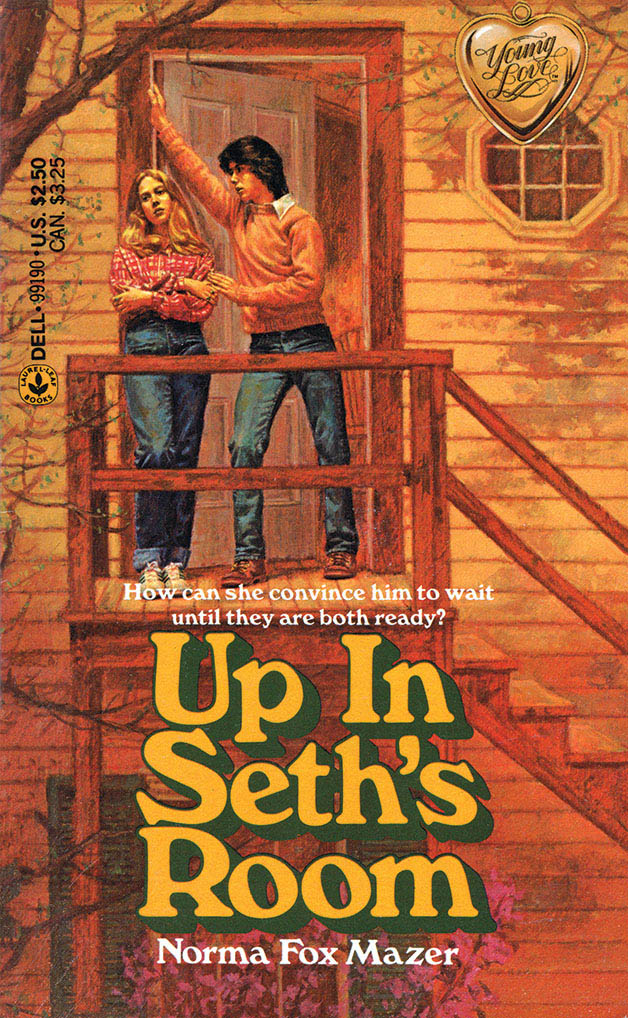

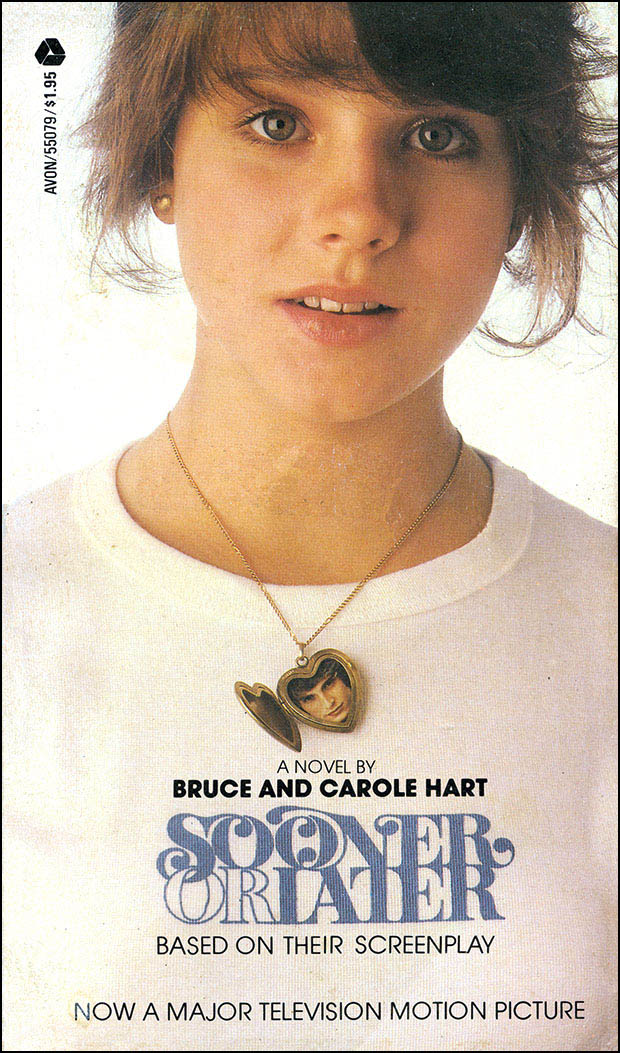

By the 1970s, novels like Judy Blume’s Deenie (1973) and Forever…(1975) and Norma Fox Mazer’s Up in Seth’s Room (1979) had pushed back on the notion that teen sexuality was inherently a problem by featuring plotlines about topics like masturbation (gasp!) and nontraumatic consensual sex (double gasp!). But they weren’t the only writers taking on teen bang-a-ramas. In 1978, Bruce and Carole Hart, writers for early seasons of Sesame Street and collaborators on Marlo Thomas’s classic album Free to Be…You and Me, published Sooner or Later. The novel sported a cover that pioneered the trend of novels about teen sex that use a locket as a metaphor for…virginity (I guess?) and followed 13-year-old Jessie as she uses the magic of a mall makeover and positive thinking to convince hunky local 17-year-old musician Michael that she is a hot-to-trot 16-year-old (only to eventually reveal the truth, and scramble to salvage their relationship). The story became so popular that it was continued in two other books (and a TV movie in 1979), making it one of the few series to address sex that successfully made the leap between the ’70s and ’80s.

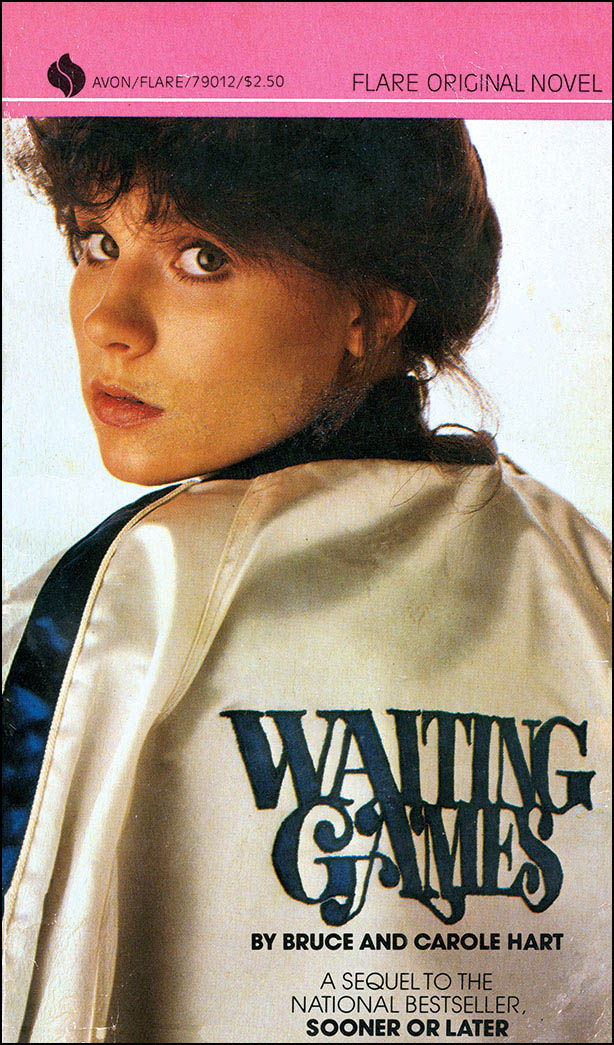

In 1981’s follow-up, Waiting Games, Jessie and Michael decide they’re still committed, despite their not-that-large-but-still-weird age gap and Michael’s tendency to jump out of the car and yell “Whoa!” at the night sky every time Jessie says that they can’t go all the way. Eventually, Jessie and Michael “do it,” in a situation where the consent is hazy by today’s standards, and the action lasts for about 45 seconds by any era’s standards. Jessie worries about pregnancy, she and Michael drift apart, and they split up so he can follow his rock star dreams to California. Eventually, they reunite in 1991’s Now or Never. Waiting Games tries to engage with the era’s changing sexual standards—as Jessie exclaims, “I mean, there’s this Sexual Revolution going on, and here I am a Conscientious Objector!”—but unlike the sex-positive heroines of ’70s YA, Jessie isn’t sure how she fits in with all these changing ideas about sexuality. She muses that sexually, she’s “slow. For my age” and then compares herself negatively to “teen-aged girls who wound up at spring training camp with the Pittsburgh Steelers, or the ones who bumped into Mick Jagger on the plane to Akron.” Furthermore, the action is almost entirely driven by Michael’s desire, and Jessie seems to be interested in sex only to keep Michael happy. The book doesn’t quite push back on that dynamic, which seems iffy to a modern reader, but is an interesting reflection of its time; if you just go by Judy Blume or Norma Klein, you might think that the average ’80s high school girl was constantly owning her own sexuality and orgasming all over the damn place, but Jessie’s confused, tentative first sexual experience was probably just as common, if not more so.

As evidenced by this cover (as well as the two covers on this page), there’s just something about a locket that screams “virginity is about to be lost!” In the case of Forever…, the necklace is in fact a plot point, but regardless of the story, the symbolism fits to an almost ridiculously literal degree: something private finally opened up…okay, ew.

And speaking of Norma Klein, her 1981 novel Domestic Arrangements presents a similarly complicated image of teen female sexuality. The book follows 14-year-old Tatiana, the youngest daughter of an artsy New York City bohemian clan (think The Royal Tenenbaums except everyone is Jewish and likes each other). Tatiana is a film actress gaining attention for a seminude scene she did in an art film (shades of Brooke Shields in Pretty Baby and Blue Lagoon) and also experimenting with gettin’ it on. The sex Tatiana has with her boyfriend, although mildly explicit, isn’t shocking or tawdry; it’s respectful and all parties involved seem into it. Rather, the real meat of the book is about Tatiana’s parents becoming estranged and taking their own lovers, while Tatiana, a bit brassier than the average suburbanite Blume heroine, wonders if her love with her boyfriend is real, or just based around, as she puts it, “fucking.” And yet a Kirkus review called the novel “blah”! Perhaps, for the reviewer, it was; YA sex novels had oversaturated the market (to the point where sexually active 14-year-old who swears like a longshoreman and appears in her underpants on film is boring) and faded from popularity by the end of the decade.

Domestic Arrangements is one of several now-vintage YA novels reissued by Lizzie Skurnick Books, an imprint of Ig Publishing that republished and repackaged out-of-print children’s and YA novels from the pre-1990s era. Besides a new cover to replace this original illustration, the reissue included a foreword from none other than Judy Blume.

But this wasn’t just because teens had moved on to a new trend. The world itself was changing. In 1981, the same year Waiting Games and Domestic Arrangements were released, the first cases of AIDS and HIV in the U.S. were reported. Teen sex in YA may have already been on its way out, but the public health crisis certainly hastened its exit. Now, experimenting with sex wasn’t just a rite of passage; it was a risky situation in which not knowing enough could get you killed (as we’ll see in the rush of HIV and AIDS cautionary tales in the ’90s; see this page). The tagline on a later edition of Domestic Arrangements made that change in attitude crystal clear: “She learned about sex too soon—Now she has to learn about love.”