n 1986, Ronald Reagan—onetime star of Cattle Queen of Montana, now the president of the United States— declared that “in recent decades, the American family has come under virtual attack.” Such was the prevailing conservative moral panic thought at the time: the cultural changes of the ’60s and ’70s had ruined everyone’s lives, single and working mothers were a blight on society, and America’s children could be saved from lives of desperation only if everyone agreed to some serious Leave It to Beaver role-playing.

n 1986, Ronald Reagan—onetime star of Cattle Queen of Montana, now the president of the United States— declared that “in recent decades, the American family has come under virtual attack.” Such was the prevailing conservative moral panic thought at the time: the cultural changes of the ’60s and ’70s had ruined everyone’s lives, single and working mothers were a blight on society, and America’s children could be saved from lives of desperation only if everyone agreed to some serious Leave It to Beaver role-playing.

Families were changing, however. Developments in and shifting attitudes about birth control during the sexual revolution, plus a mild recession, had put a dent in procreation; in the mid-1970s, the average birth rate plunged from its mid-1950s peak to the lowest of the century, less than two children per woman. Meanwhile, the divorce rate had more than doubled between 1960 and 1980—catalyzed, in part, by the nation’s first no-fault divorce bill in 1969, signed into law in California by…governor Ronald Reagan. Whoops! All told, about half of children born in the 1970s to married couples would see their parents split up.

YA lit, too, was dealing with the double standards and tangled values of the changing American family. After decades of portraying idealized parents in malt shop books and Nancy Drew mysteries, YA in the ’70s had leaned hard into parents who were, as then New York Times children’s book editor Julie Just wrote in 2010, “ineffectual, freaked out, self-centered, losing it.” But in the ’80s, YA widened its scope to include all kinds of families with all kinds of problems, including what Beth Nelms and Ben Nelms describe in their 1984 English Journal article “Ties that Bind Families in YA Books” as “happy stories of warm families, realistic stories of normal tensions and adjustments, stories that deal fairly with children estranged from their parents, and powerful stories of the dark and glorious strains of family history.” Some books documented troubled families under tremendous stress; others tried to comfort kid readers by normalizing the experience of watching parents divorce, date, or remarry. Some positioned the family as the only safe harbor from our unsympathetic garbage barge of a world. Some let the timeless struggles of sibling drama rule the stage. And some simply used the family as a pro forma setting (since 10-year-olds generally live with other people). But all in all, these books resisted hollow “family values” rhetoric by demonstrating the value in depicting actual families.

Divorce in YA had hit the mainstream as early as Judy Blume’s 1972 book It’s Not the End of the World, but by the early ’80s, YA divorce lit had grown into a full-on microgenre. Split parents became as ubiquitous in tween fiction as crimped hair or irritating younger siblings. Everyone and their mother (literally) was getting divorced.

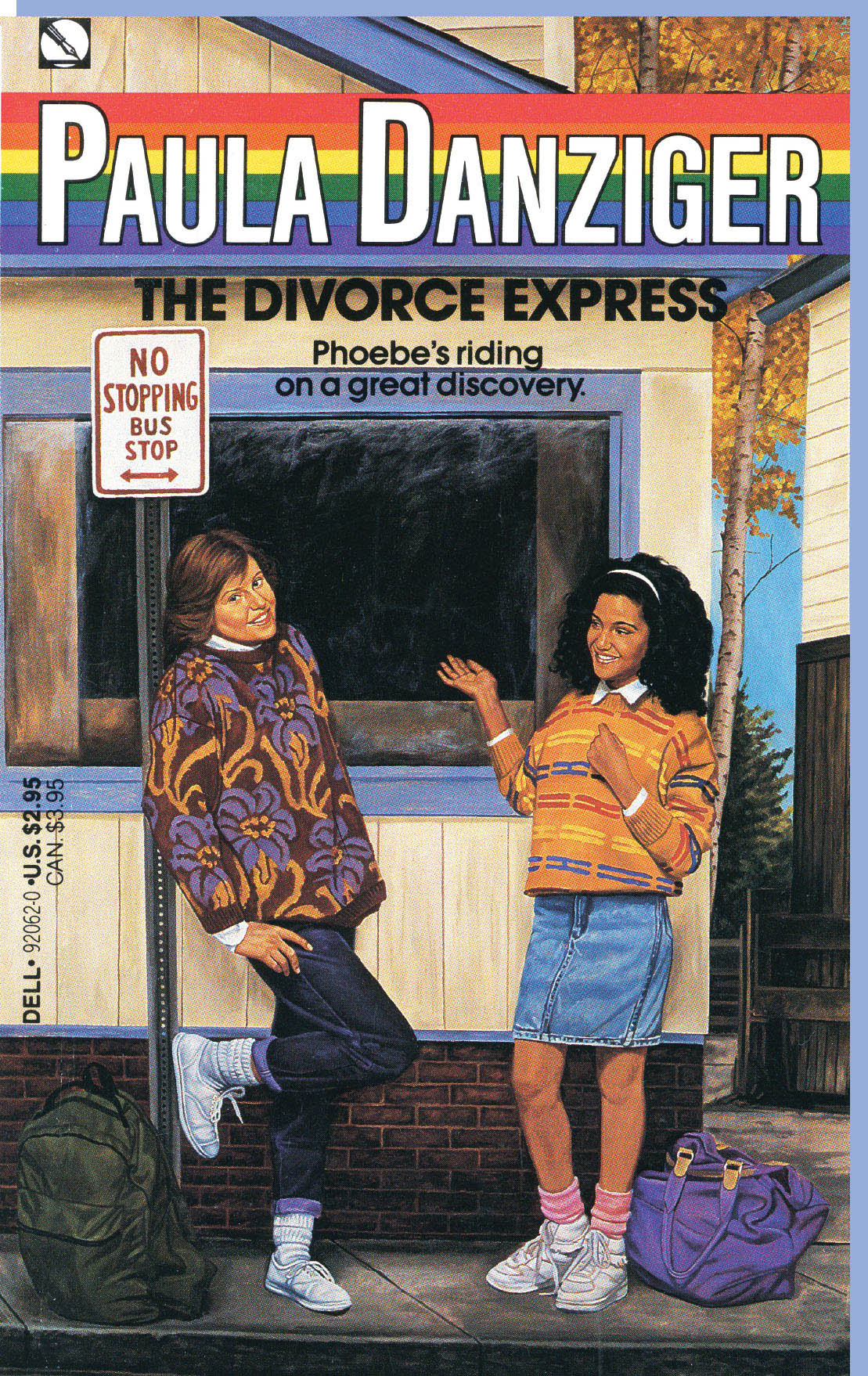

Early YA divorce classics like Paula Danziger’s 1982 novel The Divorce Express established many soon-to-be-common themes. As heroine Phoebe, who shuttles between her artsy dad and more traditional mom, puts it: “I have to learn how to handle this new situation so that it works out well for me—as well as it can without being really what I want.” With that insight gained, her transition to the child who is now wiser than her divorced parents is complete.

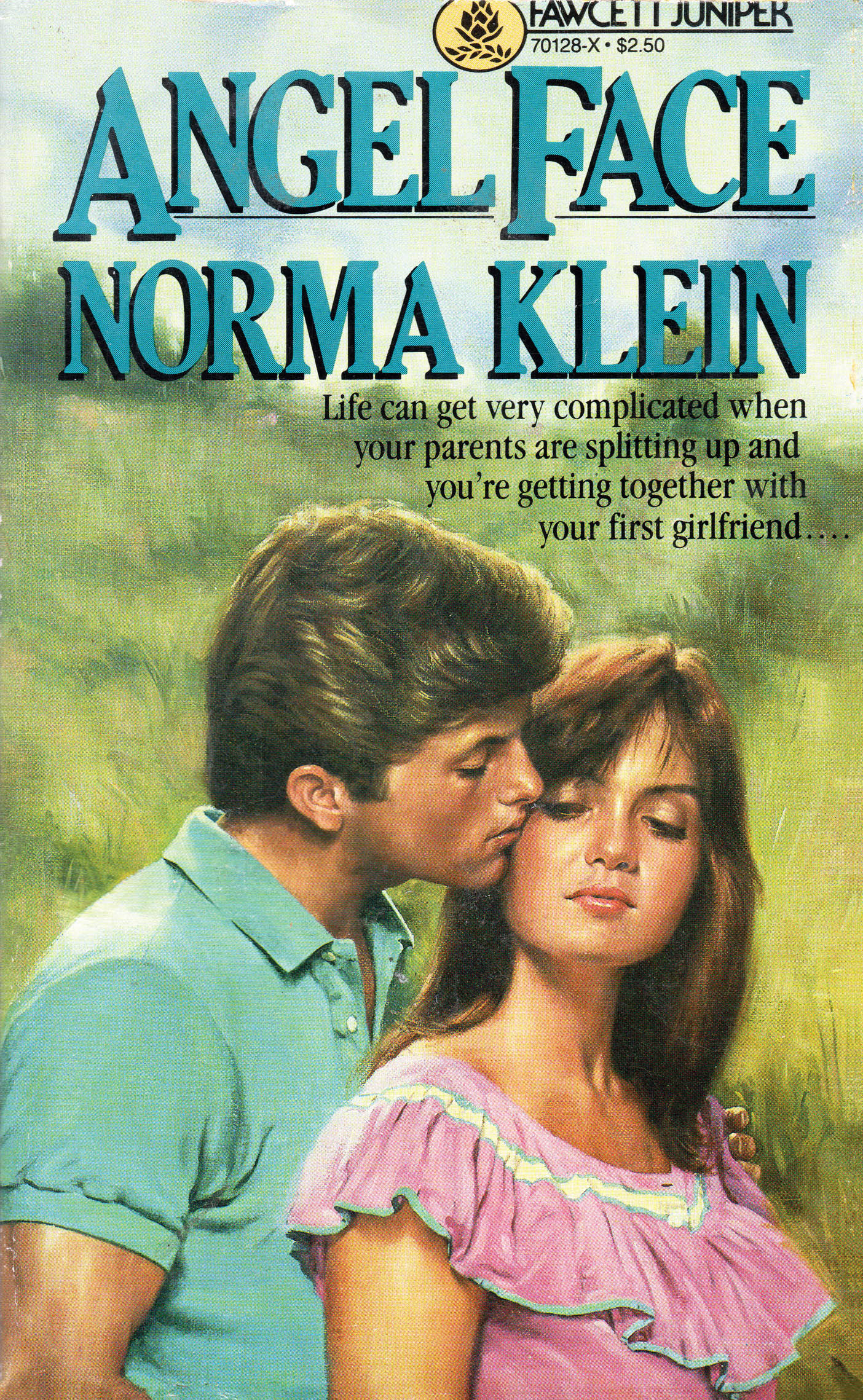

Subsequent books dug into the logistical considerations of divorce: Which parent would you live with? (Judie Angell’s 1981 novel What’s Best for You. ) How would you cope with having two homes? (Jeanne Betancourt’s 1983 novel The Rainbow Kid.) If your dad remarries a much younger woman, will your mom lose it? (Norma Klein’s 1984 novel Angel Face.) And if you’re a young girl witnessing a nasty divorce, how are you supposed to ever trust men again?

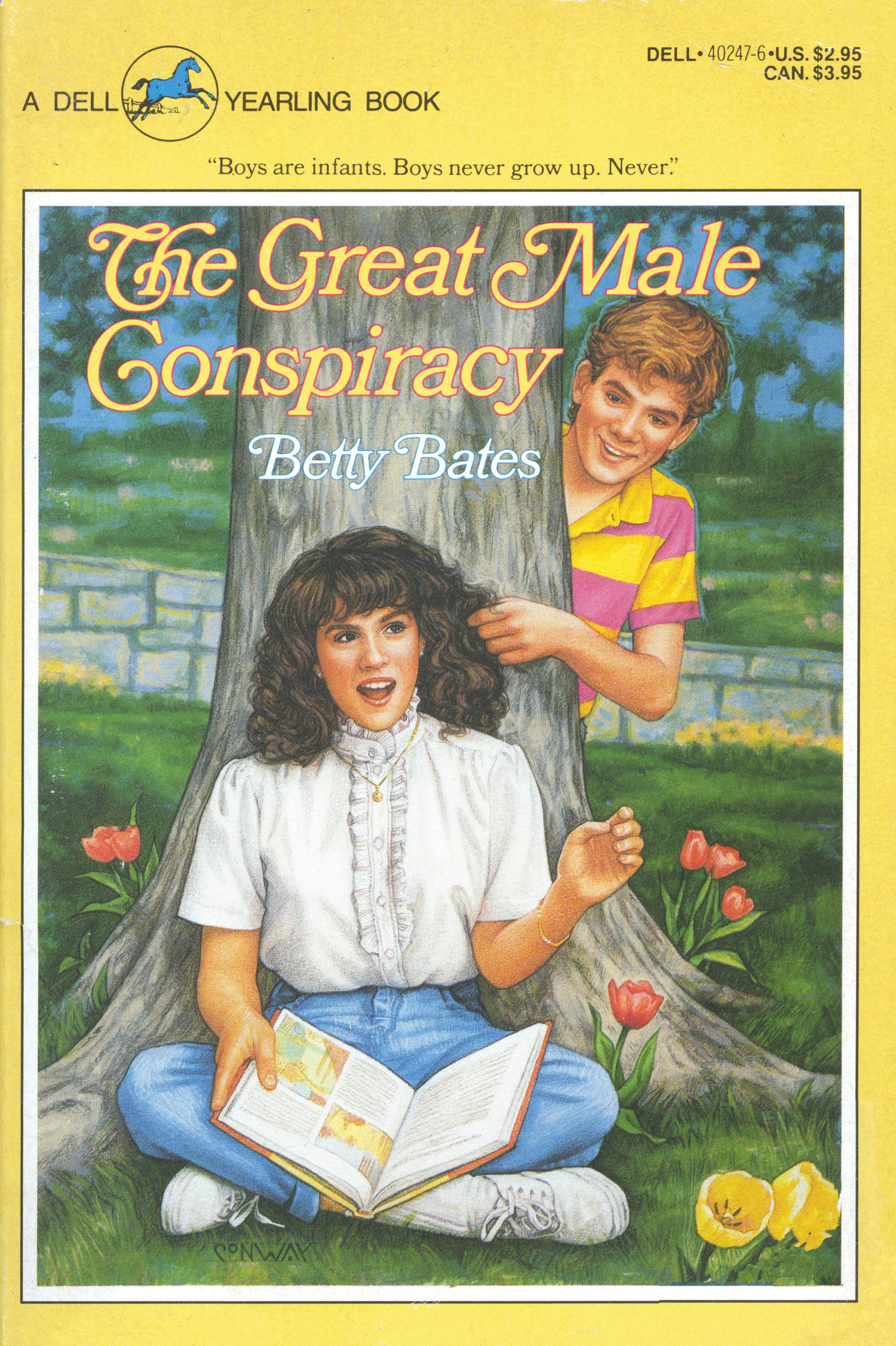

Two middle-grade books tackled that last question: Betty Bates’s The Great Male Conspiracy in 1986 and Anna Grossnickle Hines’s Boys Are Yucko! in 1989. In Boys, fifth-grader Cassie lives with her newly single mom, awaiting some form of contact from her newly deadbeat dad; in Conspiracy, 12-year-old Maggie is reeling after her beloved older sister’s husband, a dirtbag Stanley Kowalski type, leaves right after the birth of their child. In both, the girls wonder about these creatures called “men,” and why so many otherwise sensible women want them in their lives. Is it a trick? Some kind of pyramid scheme? Cassie is appalled when the girls in her class want her to invite boys to her birthday party. Maggie’s disgust is directed toward a dad who rarely helps with chores and her wiener-y friend Todd, who likes to put her down with oddly specific burns like, “You’ve been moping around for weeks, drooping like some flat tire.”

By the end of their respective novels, both Maggie and Cassie decide that most guys are all right and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis—a decision that’s less a credit to the greatness of the men in their lives than a first foray into the timeless womanly art of settling.

The illustrations for both The Great Male Conspiracy and Boys Are Yucko! err on the side of “personal space invasion, but not in a super creepy way” with some halfhearted hair pulling and condescending head-patting.

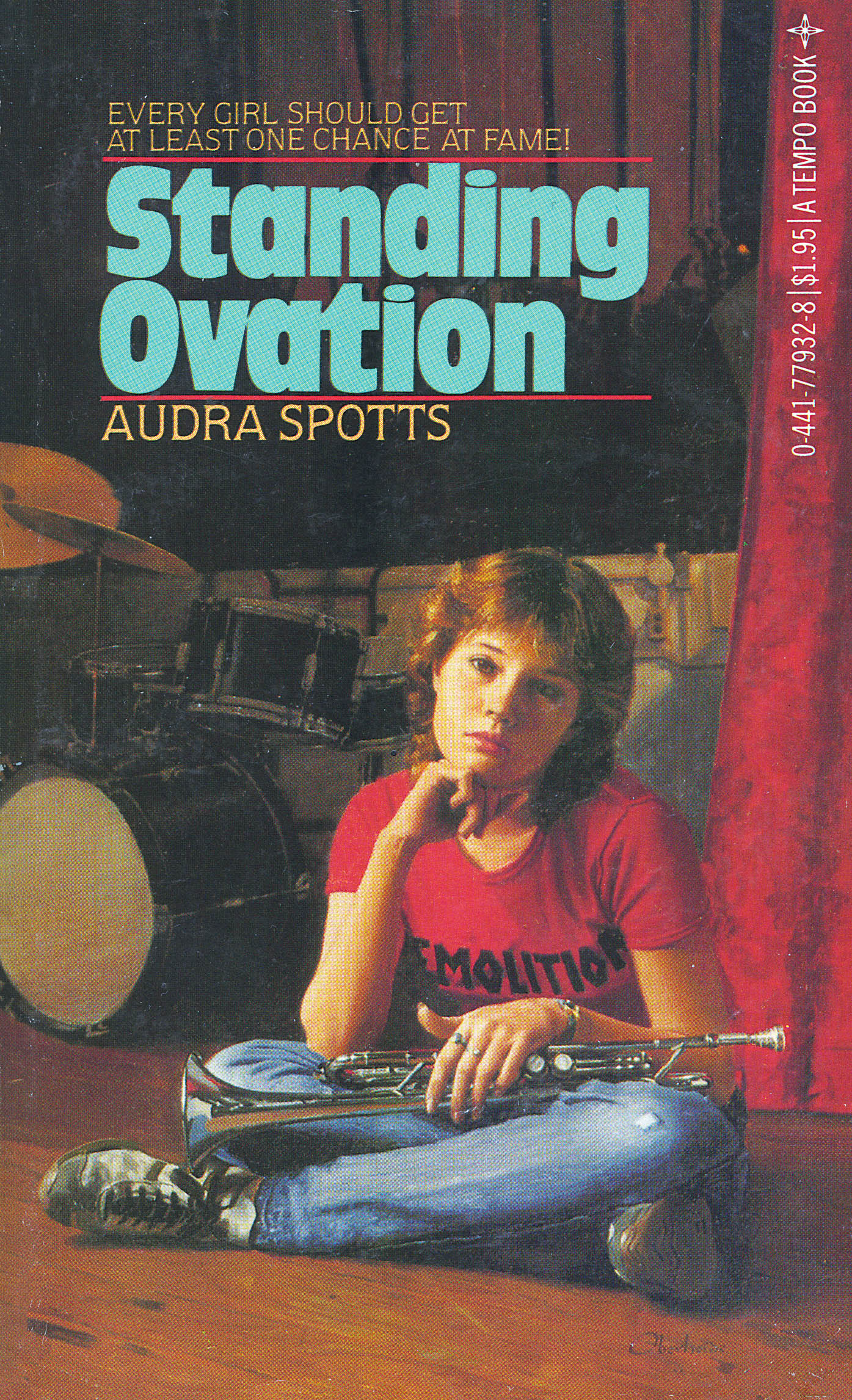

Divorcing parents may have inflicted some of the flashiest trauma in ’80s and ’90s teen lit, but they hardly had a monopoly on it. There were plenty of other ways for parents to stress their kids out! Sometimes, it was as simple as possessing a unique set of quirks and neuroses, as in Carol Snyder’s 1983 novel Memo: To Myself When I Have a Teenage Kid, in which 13-year-old Karen is aggravated by her uncool mom until she uncovers her mom’s adolescent diary and finds that even moms were once awkward, boy-crazy disasters. In Patricia MacLachlan’s 1988 book The Facts and Fictions of Minna Pratt, a quirky writer-mom presides over a clan of oddballs akin to J. D. Salinger’s Glass family who spend the novel quirking around, trying to learn healthy boundaries in between whimsical bouts of humming (seriously). Audra Spotts’s 1983 novel Standing Ovation wanders through similar territory, depicting a girl from a large family who decides to get her ex-musician father’s attention by taking up an instrument herself.

Other parents put more effort into the low-key ruining of their child’s life, such as those in Mitali Perkins’s 1993 book The Sunita Experiment. Sunita Sen’s parents upend her life when they hear that her maternal grandparents are coming from India for an extended stay at their California home. Crazed with her own residual adolescent insecurity, Sunita’s mom rushes to present a more conventional front to her family, taking a leave of absence from her job as a chemistry teacher, wearing saris instead of pants, and switching out the family’s takeout pizza for homemade Indian foods. Sunita initially responds by withdrawing socially, confident that neither her friends nor the boy she loves would want to deal with her “weird” family.” But eventually, multiple generations of the Sen family learn that embracing your weirdness is kind of what life is about. Sunita is remarkable not just for flipping the script and making the mom the awkward, insecure child character; it also engages with the struggle of relating to two cultures at once, at a time when such depictions were relatively rare.

The cover of The Sunita Experiment is a rare example of a highly stylized cover—most books of this era sported photos or photorealistic illustrations. But that’s not the only reason this cover is notable: it also portrays its heroine as the girl of color that she is, rather than “whitewash” (aka portray a nonwhite character with a white model or illustration) her, an unfortunate act of erasure that was known to plague (and still does) middle grade and YA covers.

School Library Journal praised Goodbye, Pink Pig as “a sensitive story” that “should appeal to children who have suffered from the ‘lonelies’” (which, honestly, is a lot of them).

In general, the parents in ’80s and ’90s tween lit were more well-adjusted than their ’70s counterparts. But not every book in this era was about families of shiny, happy people holding hands. The hostile, self-centered, traumatizing parents of YA’s golden age still turned up, in books like C. S. Adler’s Good-Bye Pink Pig from 1985, a sort of middle grade Glass Menagerie, complete with the brother who suddenly leaves home, the mother with impossible expectations, and the young woman who takes solace in some friendly knickknacks. Ten-year-old Amanda has a hard time at school and also at home, where her unkind, unhinged, wealth-obsessed mother berates her kids and refuses to let them speak to their paternal grandmother, who has a blue-collar job. To cope, Amanda loses herself inside a fantasy world inhabited by her favorite crystal pig figurine and other assorted trinkets (because who wouldn’t?). But in a significant departure from Tennessee Williams, Amanda gets a happy ending, living with her doting grandmother as her mother departs for a new life where, one hopes, she can maybe figure out her issues.

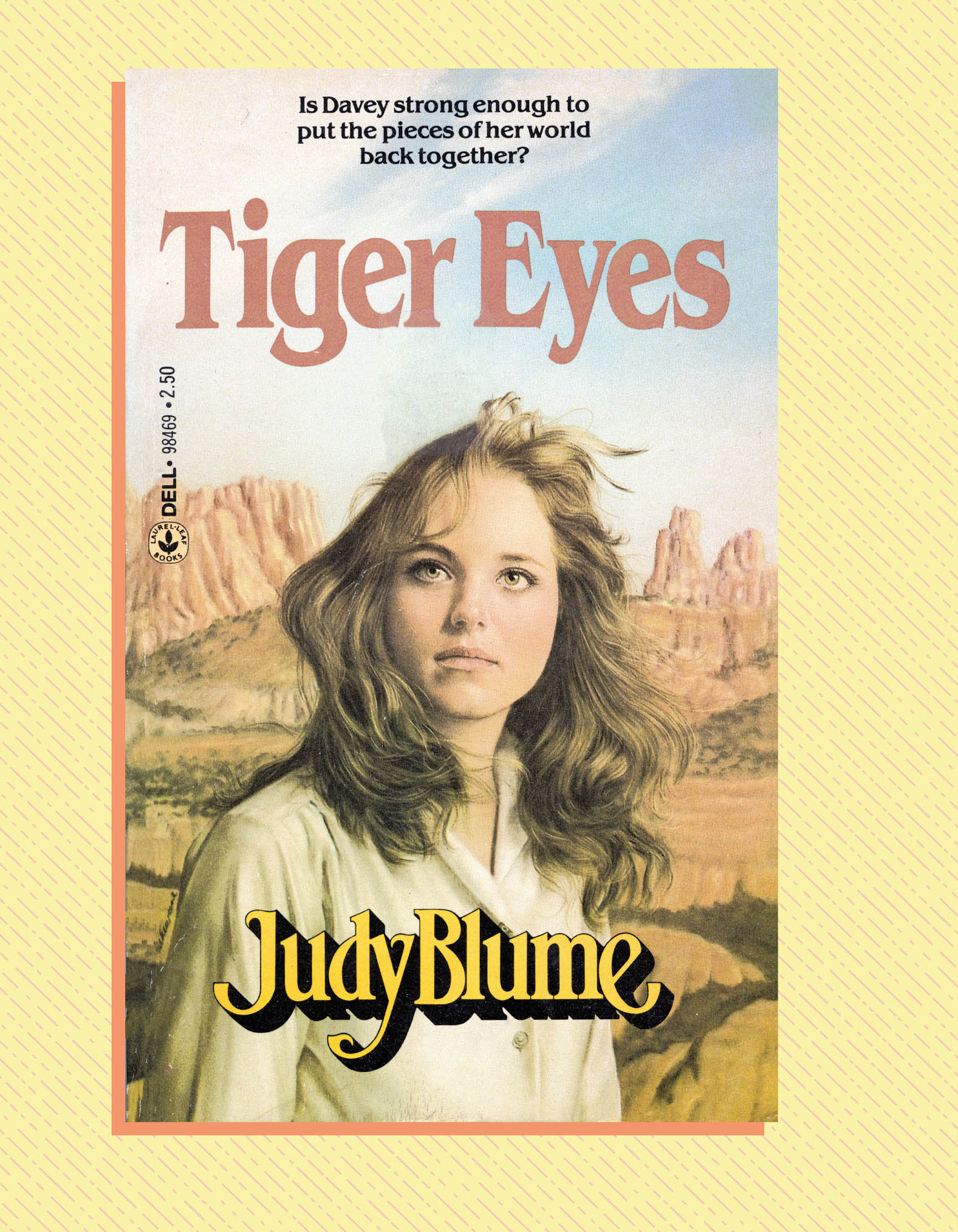

Judy Blume also got into the complicated world of depressed, confused parents, in one of her rare ’80s works. For an author that many instantly associate with the ’80s, Blume in fact published most of her famous fiction in the ’70s. Her fiction output for this decade comprised Superfudge, the 1980 sequel to Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing; the friendship novel Just as Long as We’re Together in 1987; and Tiger Eyes, in 1981, in the middle.

Of her three ’80s titles, Tiger Eyes covers the most classic Blume turf. After her father is murdered at her family’s New Jersey convenience store, 15-year-old Davey Wexler can barely get out of bed. Her equally depressed mom decides the family should take a short trip to New Mexico to visit Davey’s Aunt Bitsy and Uncle Walter, which turns into a year-long stay. Surrounded by desert and living under the legacy of the atom bomb (Walter works at Los Alamos), Davey begins to engage with the world again, befriending a local girl named Jane as well as a mysterious boy named Wolf. Through volunteering at a local hospital, where she learns that Wolf is also trying to cope with family trauma, Davey comes back to life and pushes back against her PTSD; eventually, she’s able to part with the blood-stained clothes that she wore as she held her dying father and begin to move on.

Though Tiger Eyes never explicitly comes out in opposition to family values rhetoric (which, in 1981, had barely started to gather critical mass), it takes a definitive stance against the kind of sheltering, “father knows best” parenting that Reaganite culture advocated for—Bitsy and Walter are obsessed with safety (they don’t want Davey to take driving lessons because they think it’s dangerous) and conventional metrics of success like good grades. Davey and her mother’s recovery crystallizes only when they can push back against Walter and Bitsy and return to New Jersey to live their messy, complicated, real lives.

Stranger than Fiction

Sometimes, following the fictional adventures of problematic yet beloved ’80s characters in novels wasn’t enough for audiences. Sometimes, characters broke the literary fourth wall and addressed real readers directly, in the weirdest form of series spin-off: the nonfiction companion book!

Although the idea of squeezing eager tween consumers for everything they’ve got with barely related ancillary titles feels like something Jessica and Elizabeth would have pioneered, these books existed in the earliest days of the ’80s romance boom; in 1981, Judy Blume released a tie-in diary called, appropriately, The Judy Blume Diary, which was marketed as a “special place to write about your very special feelings” and which could be purchased via a coupon in the back of books like Tiger Eyes. Two years later, Bantam published the advice volume How to Talk to Boys (and Other Important People), which offered readers of the Sweet Dreams series such crucial advice as “The Best Time to Call a Boy” (“Think twice about calling him the night before a big final or the evening before term papers are due.”) and “Dealing with his Criticism” (“By never questioning Nick’s hurtful remarks, Nell contributed to the problem.”).

The Wakefields quickly got in on the act, offering books seemingly aimed at helping the reader become a shallow, catty weirdo who places unnecessary strain on all of her personal relationships with a bottomless need for pointless drama. I am speaking, of course, about the 1988 Sweet Valley High Slam Book. Sold as a riff on installment #48, Slam Book Fever, the book was divided into categories like “Biggest Flirt,” “Most Likely to Have Six Kids,” and “Most Like Elizabeth Wakefield,” so that you too could anonymously insult your friends via a notebook that they all saw you writing in. Naturally, copies of this companion title now sell for about $1,000 on eBay.

If your parents deemed you too young for a mass-produced burn book, you could still get your hands on the 1990 Sweet Valley Twins Super Summer Fun Book, which, you’ll be happy to hear, was just as bizarre. The book is filled with tips about how to run a social club like the Unicorns (“Dues: The Unicorns each pay a dime every week. You can use the club money to throw parties, go on trips, or buy materials for special club projects”) and how to curl your hair with pipe cleaners, as well as horoscopes to help you figure out why the universe cursed you to worship these monster-girls and the Fiat they rode in on.

Obsessive Baby-Sitters Club fans who wanted to wear Kristy’s skin like a hat got a weird spin-off in 1991 in the form of the Baby-Sitters Club Notebook, which taught readers the ancient art of babysitting, complete with sections on emergency care, tips for finding clients, and blank notebook pages in the back so that you could experience the thrill of…owning a book that was only 80 pages long but felt like an even 100.

This last feature is emblematic of most nonfiction spin-offs; they delivered all of the brand awareness with around 40 percent of the content but 100 percent of the list price. Seems like a naked cash grab, but their insights were at least trying to be helpful. And who knows, maybe Nick and Nell are happily married to this day.

Though parents sometimes fade into the background of a YA novel, siblings rarely do—perhaps because they’re just so damned annoying. Even before the YA genre had a name, countless books for younger readers, like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books and Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family series, turned heavily on the joys and sorrows of life with siblings. But in the ’80s and ’90s, even that most basic childhood relationship transformed into something of a gimmick.

Friends, what can I possibly say that hasn’t already been said about Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield, the First Siblings of ’80s teen fiction? Part of a weird kid-lit fixation on twins that long predated even the Bobbsey Twins, these Fiat-drivin’, size-6-wearin’ gals from Sweet Valley were the brainchild of Francine Pascal, who by the time she created the series had already written several well-received YA novels (see this page), as well as scripts for a soap opera called The Young Marrieds. But Pascal was done with “well-received.” She conceived of the Wakefields as nothing short of a force for world domination—i.e., the series was ghostwritten from the get-go. As Pascal told the Guardian in 2012: “I wanted this to be read by a bigger audience. The books I had written before…were for a more sophisticated, educated audience. But I wanted Sweet Valley to be for everyone.” What a self-own, Francine! And yet, despite this careful engineering for mass appeal and productions, the series was originally intended to include only six books.

Was there a hint in book #1: Double Love, in 1983, as we were introduced to gorgeous, wealthy blonde twins—one boring, the other sociopathic—that they would become our constant cultural companions for the next fifteen years? As the sisters first fought over stupid Todd, was there an inkling that Sweet Valley High would become the first YA series to hit the New York Times adult best-seller list (in 1985, with the Super Edition Perfect Summer) and thereby usher children’s literature into the realm of big business? As Jessica swanned around plotting to ruin her sister’s life because a boy had the audacity to find Elizabeth more attractive, did we dare dream that this series might run for 143 volumes—plus miniseries, two separate prequel series for young readers, and something called magna editions (which I originally read as “manga editions,” but which are actually just “extra-special” installments and not graphic novel treatments at all). As mean rich girl Lila Fowler inexplicably demanded to turn the school football field into a factory, could we have possibly guessed that twenty-nine years later, in 2011, we’d be lining up for Sweet Valley Confidential, a sequel that confirmed that all the characters experienced zero emotional growth in the decade since high school? In short: what the hell is wrong with us?

Francine Pascal once famously remarked that “I didn’t intend Sweet Valley to be realistic,” which I’d certainly hope! Sweet Valley books immediately stood apart from Judy Blume’s tales of teen neuroses and other publishers’ wholesome teen romances alike through their sheer over-the-top-ness. Throughout the series, Jessica (the evil, scheming twin who was always cheating on her boyfriends) and Elizabeth (the good, irritatingly self-righteous twin who nevertheless also cheated on her boyfriends) experienced a run of trauma that would send any other laid-back California babe running for the nearest sanitarium. One or both Wakefields: got lost at sea (the imaginatively titled #56: Lost at Sea), were kidnapped by a cult (the imaginatively titled #82: Kidnapped by the Cult! ), fell into a coma and then came out with a completely different personality (#7: Dear Sister), attempted to run away to Switzerland (#38: Leaving Home; see this page), ostracized a classmate until she attempted suicide (#10: The Wrong Kind of Girl), killed the other twin’s boyfriend via inadvertent drunk driving (#95: The Morning After, #96: The Arrest, and #97: The Verdict), and, perhaps most traumatically, dyed her hair black so that they no longer looked identical (#32: The New Jessica).

The absurdity that makes it so easy to goof on the Wakefields today is also probably what got us so invested in these two dunderheads when we were younger. In Sisters, Schoolgirls, and Sleuths, children’s literature expert Carolyn Carpan called Sweet Valley the “first soap opera romance series” for teens, and indeed, the books privileged plot twists above realism. Pascal, who had once toyed with developing a TV soap for teens, conceived of each book as a stand-alone story that nonetheless invited the reader to continue to the next volume—a structure which played as much a role in the series’ theatrical vibe as did the storylines. The Wakefields weren’t so different from other romance heroines of the era, but what set them apart was the sheer speed at which life seemed to assail them with trials and tribulations.

On the cover of book #32, The New Jessica, the Wakefields seem to take a page from those other icons of American feminine duality and fighting over boys, Archie Comics’ Betty and Veronica. Jessica’s “European” makeover makes her look a little more like the life-ruining vixen she always aspired to be (she even fakes a British accent!), but the brown hair is gone by the end of the book.

And that speed was the recipe for success, according to Pascal. She once claimed that Harlequin romances were “slow” and that teenagers don’t enjoy them or similar books because “nothing happens” in them. (So, in case you were wondering: Francine definitely seems like a Jessica.) Plus, the series was truly an ongoing story, and characters reappeared in book after book, unlike Sweet Dreams and other romances of the era (this page), which presented one-off stories sewn up with a tight happily-ever-after at the end, no cliffhanger necessary. Also, even though they seemed to wake up every morning and immediately encounter a third twin hell-bent on their deaths, or whatever, the twins always looked good and acted cool. Jess and Liz were as far as you could get from a messy, confused problem-novel heroine while still being members of the same species. Pascal’s girls had not only reshaped the romance boom, they had left the classic teen “issues” novel in the dust. As the author blithely told the Chicago Tribune in 1991, “on the whole, teenage life isn’t about drug and pregnancies or rape….It revolves more around virginal angst and first love, both of which are very serious subjects.” Maybe. More likely, readers were using Sweet Valley as an escape from their distinctly non-Wakefieldian real lives.

More than anything, what set Sweet Valley High apart from other teen romances was that, at their core, they were about family. Sure, the stories were more often about plotting to steal someone’s boyfriend or accidentally getting brainwashed than they were about analyzing the true meaning of the sisterly bond, but without the family dynamic, the rest would be for naught. Two teen friends trying to steal each other’s boyfriends? Eh. Two identical twins trying to steal each other’s boyfriends? Dude, that is straight-up disgusting, and weird, and upsetting, and I can’t look away. Their family feuds are the real star of the show—we’re here for the breakups and makeups between Jessica and Elizabeth, not the ones they have with a bunch of faceless, interchangeable Chads. The twins’ abrupt about-facing from jealous scheming to peaceful forgiveness was in itself a kind of escapism; countless series promised hot boys and dangerous, thrilling situations, but how many promised that your sister would endlessly put up with your nonsense, and do it with a smile? Now there’s a fantasy.

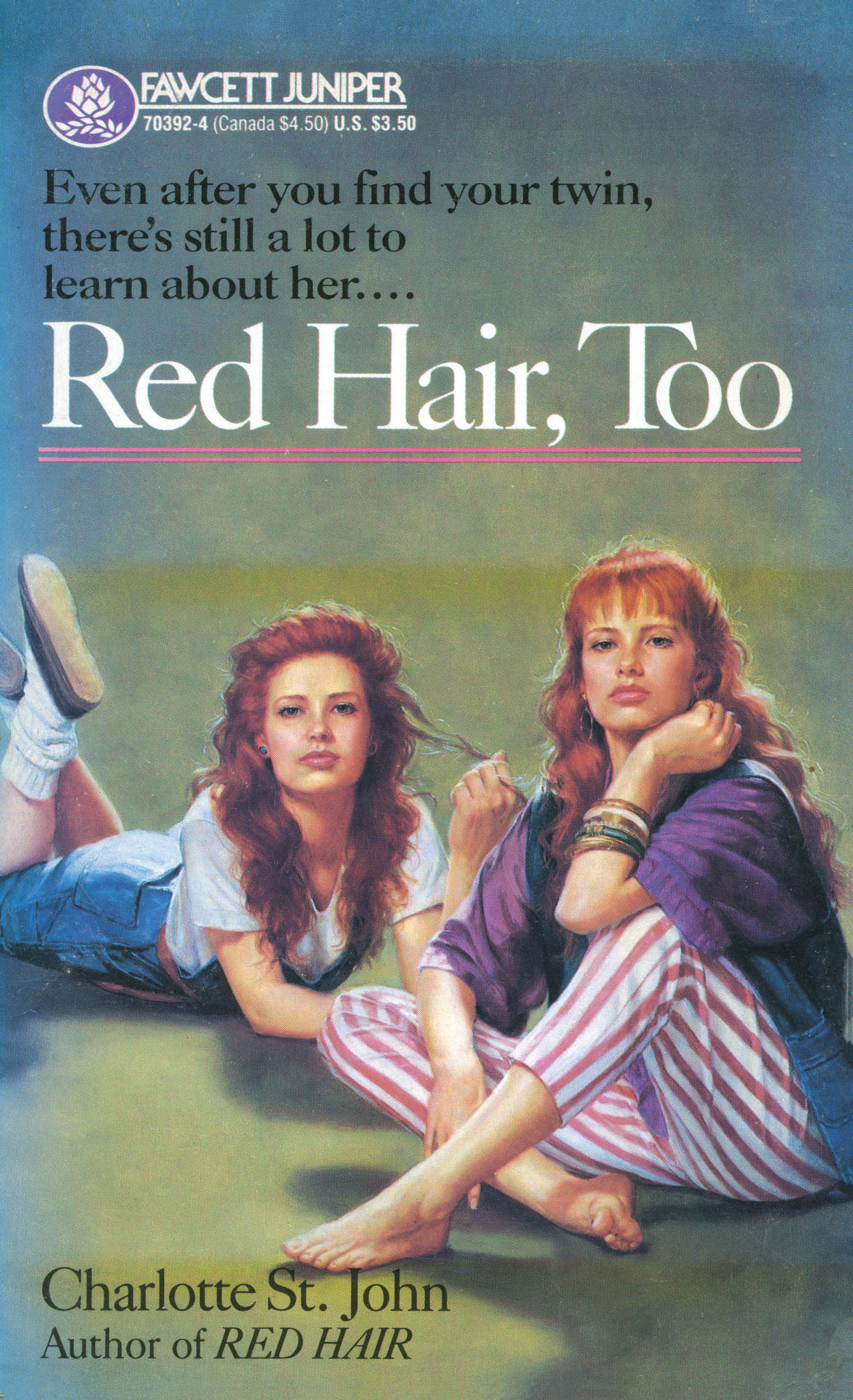

In the rush to find the next Wakefields, some publishers took things pretty literally, pumping out stories of yet more identical twins who find themselves in even more dramatic, unbelievable mishaps. I assume this was the genesis of Charlotte St. John’s Red Hair trilogy—though the 1989 series is closer to a dark Parent Trap rewrite than any kind of Wakefield pastiche. Wealthy teen Emily was raised to believe that her mother and twin sister Elaine were killed in a car accident when she was a baby, but she later finds out that in fact her parents divorced, and when they split, her father won full custody of both girls. Her mother kidnapped Elaine (but left baby Emily to just chill with her ex-husband), then faked both their deaths and fled across the country, as one does. But only for a decade or so, at which point she decided to give up the whole ruse because, hey, plot momentum! The twins reunite with much less fuss and legal intervention than you’d expect, given the circumstances, and split their time between their mother and father’s homes while still making time for edgy delinquent boyfriends in the 1991 follow-up, Red Hair, Too and HIV awareness (but also boyfriends) one year later, in Red Hair Three. Emily and Elaine did not stand the test of time as well as the look-alikes from Sweet Valley did, nor did they necessarily push the envelope on important issues (though the series interjected a little diversity into the world of twin series; the girls have a white father and a Latina mother, a fact that is absolutely not reflected on the covers) but at least they didn’t spend several pages in every book telling you how hot they were.

Though the tagline for Red Hair pushes the “twin” aspect preeeetty hard, the cover design ditches the familiar oval inset for a full-bleed illustration, lest these new twins on the block seem too close to their blonde Californian forbears.

Identical twins didn’t have a monopoly on stories about sisters fighting over awful boys, though the singleton sisters in Norma Fox Mazer’s 1986 novel Three Sisters are not as eager to forgive and forget as the Wakefield sibs. The book could just as easily have been titled Three Crappy Boyfriends, because each sister has one: 15-year-old Karen has Davey, who relentlessly pressures her for sex and, after she refuses, drops her for her best friend; 18-year-old Tobi has Jason, her 30-something college art teacher who sculpts when he isn’t busy being a violent drunk; and 21-year-old Liz has Scott, her fiancé, who flirts with the hopelessly crushed-out Karen…and then kisses her! On two separate occasions! While she’s still 15! Mazer emphasizes how these problems, which initially place stress on the siblings’ relationships with one another, ultimately pale before the strength of their bond. But the secondary story is about how even smart, confident women from loving, supportive families can end up in relationships with people who run the gamut from sleazy to criminal. So while the book offers a shot of hope, there’s also a streak of darkness: strong family bonds cannot protect us completely from injurious outside forces, no matter what President Ronnie says.

In addition to parent and sibling stories, in the ’90s, the family novel spotlight briefly turned to cousins. Sibling books still reigned supreme, to be sure, but some publishers, burned out on the antics of the Wakefield sisters and various spooky psychic twins from teen horror novels, went in search of novelty. And for one brief, shining moment, they found it with the main character’s mom’s brother’s daughters.

Cousin lit could be high-brow, as in award-winning author Virginia Hamilton’s 1990 novel Cousins, in which Cammie has a complicated, prickly relationships with Patty Ann, her wealthy, perfectionist cousin who secretly struggles with an eating disorder. Cammie and Patty Ann’s complex relationship continues on after Patty Ann’s sudden death, eventually bringing the entire family back together, including Cammie’s dad, who’s been out of the picture for a while.

But often, this subgenre was far more commercial, like Colleen O’Shaughnessy McKenna’s Cousins series, which lasted for two volumes in the summer of 1993, perhaps because of its obvious and limited subject matter. Book #1, Not Quite Sisters, follows Callie, the eldest in a crew of six cousins, who is trying to welcome her cousin Jessica back to town. This in turn creates drama with another cousin, Lindsay, who is jealous of Jessica. For example: “Maybe you hang around with me because I’m the cousin closest to you in age. But, what if you decide Jessica is the best cousin?” In the next book, Stuck in the Middle, Lindsay and Jessica start to worry when Callie drops them for the group of older kids that hangs around the public pool. Publisher Apple seems to have realized that there’s a ceiling on how much drama you can wring out of the relationships between people who have known one another their whole lives, but also who see each other twice a week tops, and bagged the enterprise fast. (Also, I’m not here to point fingers, but the tagline on Not Quite Sisters, “Kissing cousins? No way!” seems to badly misunderstand at least two concepts.)

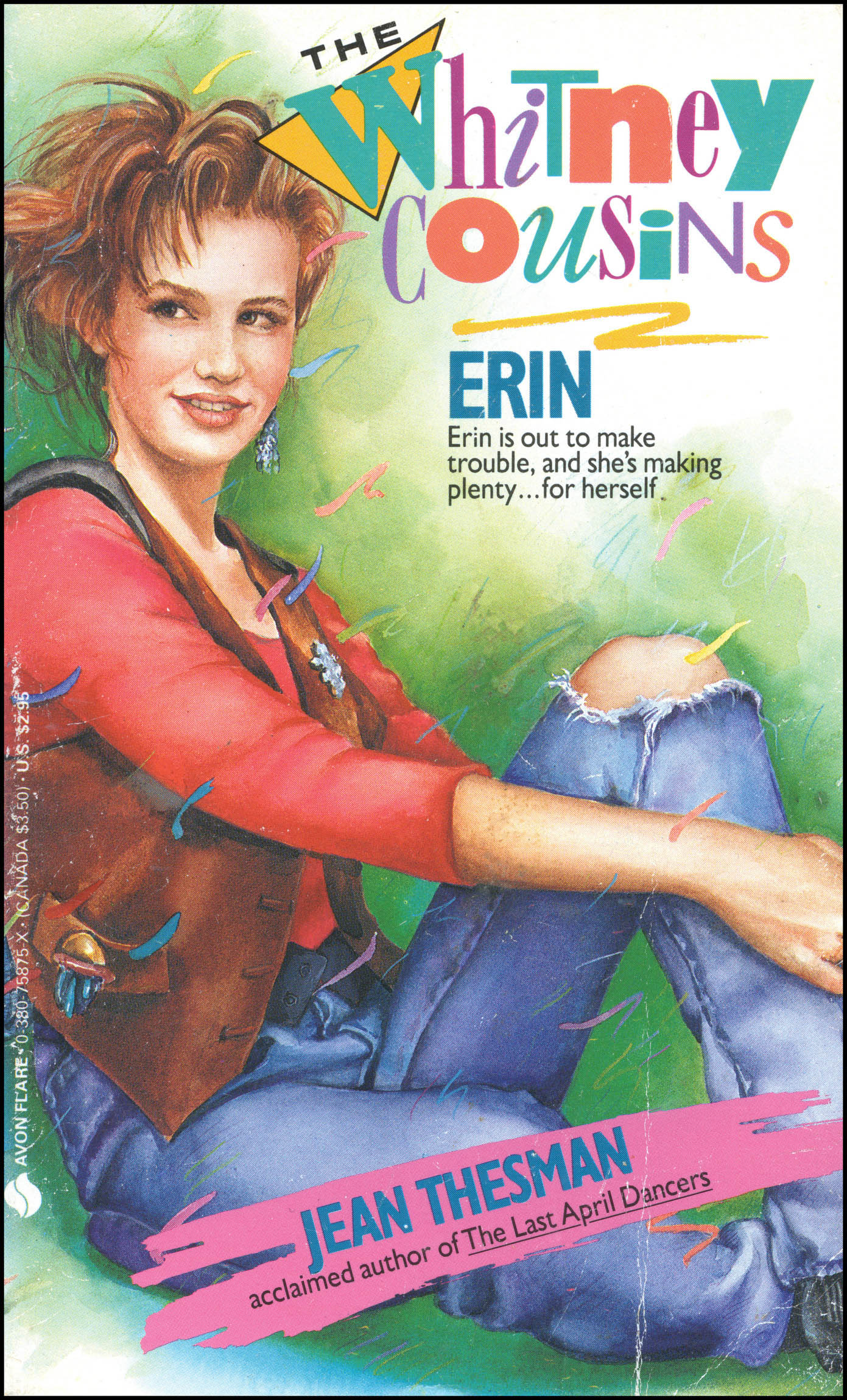

The Whitney Cousins covers made the family series a little funkier and jazzier for the ’90s, complete with artistically torn-up jeans and a type treatment ripped from a Caboodle.

Slightly more successful was Jean Thesman’s Whitney Cousins series, which totaled four books published between 1990 and 1992. The Whitneys didn’t focus exclusively on cousin-on-cousin squabbling; these three cousin-friends dealt with extremely contemporary social issues like blended families, the death of a parent, sexual assault, and so on, all while wearing what your mom would call a “funky” outfit (as you can see on the opposite page, the girls were fond of statement brooches, sassy vests, and a nice gladiator sandal). Yet even that approach seemed to hit a wall awfully quickly, and after three books that examined weightier topics, we suddenly had #4: Triple Trouble, a book about the town carnival and one Whitney cousin’s effort to become a clown. (Really, we’re the clowns for having bought this stuff, right? Am I right? I’ll show myself out.) Despite its best efforts to push the clown-containing envelope, cousin-core never took off the way books about closer blood ties managed to.