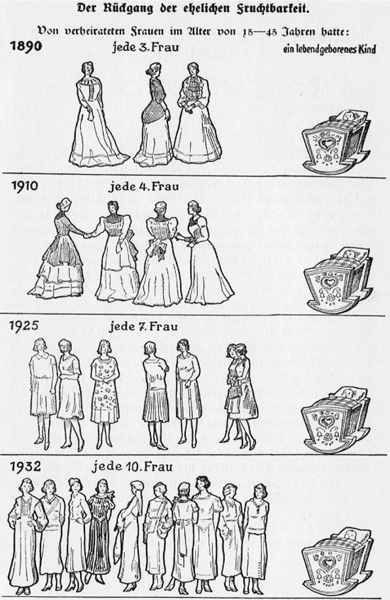

Figure 6.1 “Decline in matrimonial fertility” (Helmut 1939: 7)

“The crowd,” Mussolini once said, “loves strong men. The crowd is like a woman”; “women,” he also averred, “exert no influence upon strong men” (In Ludwig 1933: 62; 112). Such sayings nicely encapsulate the official fascist “solution” to the evolution in the role of women taking place in the Western world in the course of the 19th century and at the start of the 20th century, as well as the way that “the question of woman” was regarded as impinging not solely on the relation between the sexes, but as having a general, extended social meaning, pertinent to the relation between the classes, the élite and the mass. The revolt of the masses and the revolt of women were considered two sides of the same coin, and both called for a similar remedy: as long as the élite remained strong and masculine it could hope to keep the feminine masses under its sway; the fact that this was no longer the case in modernity was a symptom of the decay of strong leadership under weak liberalism and justified the renewal of virility that fascism claimed to represent.

It should be noted that this restoration of the “natural order” was never complete under fascism, nor was the interchangeability of woman and mass regarded as absolute: in practice, the class defense (as well as attack) mechanism that was at the heart of fascism also served to mobilize many women for the fascist cause. The paternalistic approach to the mass allowed women organizations, typically run by the upper and middle classes, to establish bases of influence and highly visible public presence at the center of the fascist system in many countries. In tandem with the feminization of the mass, one can find examples of fascist women adopting—sometimes with the support of the leading fascist politicians and thinkers, who were almost always men, and sometimes in a certain tension with them—masculine characteristics and images as part of their enrollment in the nationalist and class project. On other occasions, such organizations were seen as having something distinctly feminine to contribute to the domestication of the mass.

To be sure, not all women socially belonged to the ranks of the masses, while many men did. Yet this did not impede the subsuming of political categories under sexual ones, aided by the fact that, in most European languages, “the mass” is a feminine noun: la massa, la plebe, la folla, la moltitudine in Italian, la foule in French, die Masse, die Menge in German, etc., whereas “the state” or “the people” are usually masculine nouns (although other concepts dear to the fascists such as nation or race, are often feminine nouns).

The fashionable studies of the masses and their “psychology” and “soul,” which began in the 19th century as part of the effort to find solutions to social unrest, including among its salient practitioners such figures as Scipio Sighele, Wilfred Trotter, Gabriel Tarde and, most notably, Gustave Le Bon—who sent Mussolini at least four of his books after the First World War, a gift that was enthusiastically received (Barrows 1981: 179)—frequently linked perceived effeminacy with the wave of massification. Le Bon (1960: 39) asserted that “Crowds are everywhere distinguished by feminine characteristics.” The masses were regularly ascribed traits which were originally ascribed to women (35–36): “impulsiveness, irascibility, incapacity to reason, the absence of judgment and of the critical spirit, the exaggeration of sentiments,” and—perhaps most significantly—hysteria. Talk about “hysterical masses” or “mass hysteria” was common, and the psychic disturbance called hysteria was mainly identified with women, derived from the Greek term hystera (ὑστέρα), uterus, and based on the hoary belief in the harmful effects of “the wandering womb.”1 By extension, the apparent whims of the feminine mass could be accounted for with recourse to hysteria. And the treatment of such pathological condition also seemed to be similar in both cases: just as the ideal treatment for hysterical women involved hypnosis, so the hysterical masses need to be politically hypnotized.

As was discussed in Chapter 2, woman’s advancement was regarded by its critics as symptomatic of a general social decay. If even women, subjugated from times immemorial to men’s rule, dare to demand equal rights, civilization must have come to a very hard pass indeed, and its very survival appeared uncertain. That woman strayed away from her femininity, desired to engage in “masculine” activities, was perceived as mirroring the way in which man was losing his virility and drifting towards femininity. As Mussolini put it, “the crowd loves strong men;” “women exert no influence upon strong men,” implying that weak men invite trouble. Fascist gender policies were thus of a two-thronged approach, seeking to redress both femininity and masculinity. They were nearly always expressly anti-feminist both in the literal sense—the relations between men and women—and in the metaphorical one, regarding the rapport between the élite and the mass. Let us again listen to Mussolini (In Ludwig 1933: 170–171):

Woman must play a passive part. She is analytical, not synthetical. During all the centuries of civilisation has there ever been a woman architect? Ask her to build you a mere hut, not even a temple; she cannot do it. She has no sense for architecture, which is the synthesis of all the arts; that is a symbol of her destiny. My notion of woman’s role in the State is utterly opposed to feminism. Of course I do not want women to be slaves, but if here in Italy I proposed to give our women votes, they would laugh me to scorn. As far as political life is concerned, they do not count here. In England there are three million more women than men, but in Italy the numbers of the two sexes are the same. Do you know where the Anglo-Saxon countries are likely to end? In a matriarchy!

Mussolini here freely vents his contempt for women, verging on outright misogyny. Such deprecating views were very common among fascist men and some went a great deal farther than Mussolini, among them the Futurist writer Giovanni Papini, who in April 1914 assured his readers that the ability to create masterpieces in any domain is reserved to men alone.

Papini reports that three men of note have recently emerged as acute interpreters of the female nature: Friedrich Nietzsche, August Strindberg and Otto Weininger. Papini summarizes some of these men’s shared opinions using a crude metaphor. He says that, according to them, women are “orinali di carne” (“urinals of flesh”) for men’s pleasure, and good only for their procreative function.

(Sica 2016)

It is true that Mussolini did not always express himself so bluntly as in the above quotation. Elsewhere, he applied a subtler approach, combining flattery with aggression. For example, in a speech addressing the issue of women’s vote, Mussolini praised the Italian woman’s modesty and moderation and paid tribute to the heroics displayed by many women during the great war, at the same time that he revealed himself pessimistic with regards to women’s abilities and asserted his belief that “woman lacks the skills of synthesis and is therefore deprived of the ability for great spiritual creation” (Mussolini 1958, vol. 21: 303). On the one hand, he promised that woman’s role will be even greater in the next war, while, on the other hand, he concluded the speech (305) by strongly emphasizing the need for discipline and obedience to the leader. The general direction striven at by fascism with relation to gender, however, was highly authoritarian and conservative, drawing upon crude binary images of woman as mother and man as a warrior. “War,” Mussolini speculated (1958, vol. 26: 259.), “may be man’s tragic destiny. War is to man what motherhood is to woman.”

As discussed in Chapter 3, the First World War was meant to discontinue the rise of a generally massified social ethos, which was eo ipso a “feminine” one: the long peace was frequently seen as facilitating a feminine way of life—hedonistic, squeamish, consumerist—unbefitting of real men, who long for the ultimate risk and trial of war. Yet the war proved doubly disappointing: it managed to reign in neither the mass nor woman. The impudence of the former only increased, and its social and political demands became even more sweeping, while the latter gained a significant foothold in domains traditionally regarded as exclusively male: non-domestic labour and public activity. Instead of re-accentuating the boundaries between the genders, the war merely blurred them farther: soldiers came back home to find women much more visible in the labor market. And given that the mass was feminine, fascism faced the task of re-subjugating both the populace and women. Fascist politics was always codified in gender terms: just as the mass was feminine, fascism boasted of its virility, and the state recovering its honor after the rise of fascism could thus be presented as a patriarch reestablishing his rule over women and children. In the following speech given by Mussolini in 1923 social conflicts were construed along gender lines. It should be born in mind that the noun ‘state’ is in Italian a masculine one—lo stato:

The problems of public order are related to questions concerning the definition of the authority of the state. […] One should compare the condition of Italy in the years 1919–1920 [the biennio rosso of workers and peasants’ agitation] and in 1921–1922 [the years of the fascist repressive activity]. The main fact of 1919–1920, […] which we will call the years of the demagogic orgy, is the occupation of the factories. The main fact of the next couple of years is the fascist punitive expeditions. […] Today, all this is over, today public-service workers do not strike, nor will they strike. […] Public order in the latter half of the previous year, reached the nadir of its disintegration. In August a strike begins, the anti-fascist strike, totally paralyzing the state. The state does not react, those who react in its stead are the fascist forces. […] As soon as the state becomes irrelevant [inattuale], drained of all its virile attributes, and another, potential state, forms and rises, a very strong state, capable of imposing discipline on the nation, it is necessary to replace, through a revolutionary act, the irreparably decaying state with the one that is rising.

(Mussolini 1958, vol. 19: 251–252)

Fascism transforms the state from a malfunctioning, emasculate man, unable to restrain the “demagogic orgy,” into a man that has been rehabilitated, and can impose his will on the lower orders. The old liberal élite was weak, passive and feminine, easily overwhelmed by the mass, while the new, fascist élite, is properly virile. In a 1934 article, Mussolini (1958, vol. 26: 378) thus boasted of “the Italy of fascism, masculine and warrior Italy of today and tomorrow,” that has brushed aside the old Italy, “of democracy in slippers and long johns, weak-kneed, defeatist and cowardly.”

The fascist leader was perceived as embodying triumphant masculinity, asserting itself vis-à-vis the mass, which has imagined itself in possession of manly virtues such as force and independence, only to be shown what it really is: a weak woman who needs, and secretly desires, to be commanded by a man. Italian fascism carefully cultivated Mussolini’s public image as the personification of masculinity. Photographs were widely distributed showing him engaged in demanding physical action, hard work in the field or sporting activity such as skiing, often with a naked torso, and attention was drawn to his many mistresses whereas his role as father and family man was marginalized, for fear that it might dent his tough image (Spackman 1996: 3).

The restoration of virility and the subjugation of femininity were central to fascist politics, an aspect that some scholars regard as key to understating its entire Weltanschauung, a crimson thread linking its different components.2 An early example of this discourse is provided by Ernst Jünger, the glorifier of militarism, in a book describing the exhilaration of fighting in the First World War. In the following passage, Jünger (2002: 19) not only presented fighting as the exclusive domain of men, but also as one that provides a quasi-erotic elation that in fact overshadows the actual love making between the sexes:

The blood storms through the brain and the veins as in a long anticipated night of love, but much more passionate, much wilder. […] The baptism of fire! The air was so charged with masculinity, that every breath was intoxicating: one could cry without knowing why. Oh, the hearts of men, capable of such emotion!

For many, the war signified the catastrophic bankruptcy of the cult of battle with its hollow masculine clichés. It thus served as a starting point, whether this was done consciously or not, for the construction of new and non-dichotomous conceptions of masculinity and femininity, stressing equality, openness and reconciliation. This was a move that Jünger and his like, returning anxious from the battlefield, were determined to undermine. In 1922, when for most European women and men the war was a nightmare they were trying to put behind them, Jünger vindicated its honor—and virility. And a year later, in a speech from which we have already quoted, Mussolini too emphasized the way that fascism rejected the subversion, characteristic of the postwar period, of traditional boundaries and differences between social and political categories. His words did not refer to differences between the sexes but are applicable to them as well, and some would say to them especially:

In a profound sense, what was the source of the affliction of Italian life in the last years? […] There were never any clear boundaries. […] The whole atmosphere was one of middle shades, of uncertainty; nowhere to be seen were clearly defined contours. Well, this is exactly the part filled by fascism in Italian life. It seizes the individuals by their collars and tells them: you should be what you are.

(Mussolini 1958, vol. 19: 261)

From men, therefore, fascism demanded to be “men,” and from women “women,” that is, to remold themselves according to the old templates, the very ones whose inadequacy was put into evidence by modernity and the Great War.

At this point, many fascists encountered a paradox. On the one hand, they stressed the way the old gender roles and images corresponded to the biological nature of men and women. This innate order was violated by unnatural, revolutionary developments. Yet at the same time it was clear that nature was greatly unreliable, failing to provide the firm bedrock that was called for: thus, in order to create the sharp distinction between the sexes, to put an end to the intermingling and interpenetration of spheres and attributes, one had to rely precisely on culture, and employ artificial means to supervise the proper development of a masculine man and a feminine woman. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was one of many deeply disturbed by the man’s loss of virility, and hence demanded to “finally put an end to the mixture of males and females that during the earliest years always produces a harmful effeminizing of the male.” He insisted that boys should be separated early on from the girls to ensure “that their first games be clearly masculine, that is, free of emotional morbidity or womanly delicacy, lively, feisty, muscular and violently dynamic.” Short of such separation, the development of the masculine character is hampered, since young boys “always succumb to the charm and the willful seductiveness of the little female” (In Spackman 1996: 8). On these plans, which clearly expose the fascist fear of the natural course of development and de facto acknowledge the artificiality rather than biological character of gender roles, Barbara Spackman wittily comments (8): “The logic of this passage runs counter to the commonplace that ‘boys will be boys’: given half a chance, boys will be girls.”

Wyndham Lewis, who occasionally lent fascist ideas a greater degree of sophistication, dealt with this paradox in an original way. Discarding the notion of biological differences between the sexes to which most fascists held fast, he readily acknowledged that masculinity and femininity are not natural patterns of behavior but depend heavily on culture and conventions. In that respect he came close to the positions later developed by feminist theories according to which the hierarchical relations between man and woman are a product of gender rather than sex:

Men were only made into “men” with great difficulty even in primitive society: the male is not naturally “a man” any more than the woman, he has to be propped up into that position with some ingenuity, and is always likely to collapse. […] A man, then, is made, not born: and he is made, of course, with very great difficulty. From the time he yells and kicks in his cradle, to the time he receives his last kick at school, he is recalcitrant. And it is not until he is about thirty years old that the present European becomes resigned to an erect position.

(Lewis 1989: 247–248)

And yet, while accepting that the role of man has always been a difficult and unpleasant task, a determined rowing against the currents of nature, only in modern times was the question raised: ought one to go there at all? Would it not be better to give up such manliness which is so hard to earn? The roots of the rebellion against this gender role Lewis traced back to the trauma of the First World War, during which man’s nature cried “never again” and he decided to defect from civilization. It was during the war that men “were saying to themselves subconsciously that at last, beyond any doubt, the game was not worth the candle: […] that the institution of manhood had in some way overreached itself or got into the caricatural stage” (Lewis 1989: 247). Yet this acute insight did not make Lewis abandon the model of manhood or subject it to any criticism. On the contrary: his opposition to feminism, an attitude coming from both men and women, was only deepened. The approximation between the sexes is natural, it perfectly fits the inclinations of both women and men, and this is precisely why it should be condemned. The artificiality of the relationship, the enormous difficulty with which it is structured against the natural impulses, is its great attainment, which must be preserved. Conversely, the way of the Last Humans, of the masses, leading to greater equality and relaxation in the rapport between the sexes was easy, comfortable and natural. And on that account it must be categorically rejected. An unnatural thing, manhood is the glory of human culture and as such must be protected against men who seek to shirk their duty to culture, evade “responsibility” and “heroism”:

There are very many male Europeans who never become reconciled to the idea of being “men” (leaving aside those who are congenitally unadapted for the rigors of manhood). At thirty-five, forty-five, fifty-five, und so weiter, you find them still luxuriously and rebelliously prostrate; still pouting, lisping, and sobbing […]. He does not want, if he can possibly help it, to be a man, not at least if it is so difficult. […] So “a man” is an entirely artificial thing, like everything else that is an object of our grudging “admiration.” […] The snarling objurgations of the poor man’s life [sic] such as “Be a MAN!” (banteringly and coaxingly) or “CALL YOURSELF A MAN!” (with threatening contempt), arouse “the man” in the male still: but we can confidently look forward to the time, now, when this feminine taunt will be without effect.

(Lewis 1989: 248)

Here Lewis rehearses the common argument against feminism, namely that women, in their heart of hearts, at least real women, for all their complaints against patriarchy, long for a real—i.e., artificial—man, one who has accepted the burden of culture. Feminism—and here Lewis is reminiscent of Nietzsche—is first and foremost a result of a male dysfunction, a response to a vacillating masculinity, shedding off its assets. As likewise explained by Hitler in a 1934 speech to the members of the NSF, The National Socialist Women’s League:

The slogan “Emancipation of women” was invented by Jewish intellectuals […]. In the really good times of German life the German woman had no need to emancipate herself. She possessed exactly what nature had necessarily given her to administer and preserve; just as the man in his good times had no need to fear that he would be ousted from his position in relation to the woman.

In fact the woman was least likely to challenge his position. Only when he was not absolutely certain in his knowledge of his task did the eternal instinct of self and race-preservation begin to rebel in women. There then grew from this rebellion a state of affairs which was unnatural and which lasted until both sexes returned to the respective spheres which an eternally wise providence had preordained for them.

(In Noakes and Pridham 1984, vol. 1: 449)3

And as Mussolini indicated, the rebellion of women is a protest not against the rule of men as such, but against weak men, who do not know how to rule. The feminine mass turns hysterical in the absence of manly élites to govern it. Not only does the womb tend to wander, but it is gripped by the desire to roam mainly when no strong man is about. This, incidentally, was part of the theory of the wandering womb to begin with, as originally developed by Hippocrates and Plato. As explained by cultural historian G.S. Rousseau (1993: 118), the theory held that “the uterus, when deprived of the health-giving moisture derived from sexual intercourse, would rise up into the hypochondrium […] in a quest for nourishment.”

Fascism, in that sense, was a form of libidinal politics, aiming to mobilize for its purposes the sexual drive. In an interview given a few years ago, Roger Griffin commented as follows on Wilhelm Reich’s influential theory of fascist authoritarianism as feeding upon sexual repression:

There was a major book by a guy called Wilhelm Reich who said what drove nazism was sexual frustration. Well, Europe has changed sexually now, there are not so many sexually frustrated people wandering around. I think if there had been plentiful marijuana in Weimar, than [sic] maybe Hitler would not have been quite so successful either.4

(Faschisten sind immer die anderen 2012)

Be the case as it may, fascism in truth presumed to supply some form of collective sexual healing. “Presumed” is perhaps too strong a word, for this intent was not, for the most part, openly proclaimed in official fascist texts, speeches, doctrines and the like. But between the lines its presence can certainly be felt. Mussolini was prone to interpret politics with reference to an erotic subtext, and to sexually construe political and social entities—the state, the mass, the nation and so on and so forth. We have already had a couple of occasions to witness this procedure, but many more cases could be cited. For instance, conversing with one of his colleagues in the late 1930s, Mussolini explained the tension between England and Italy as stemming from the sexual frustration of English women. “Four million superfluous women,” he affirmed. “Four million women sexually unsatisfied, artificially creating a host of problems to arouse or calm their senses. Unable to embrace one man, they embrace humanity” (In Ciano 2006: 187). And in 1925, in one of his most famous speeches, called “the speech of June the 3rd,” a discourse appreciated by many historians as signifying a turning point after which fascism abandoned the rule of law and began to unabashedly embrace authoritarianism, Mussolini presented fascists, with himself at their head, as men coming to impose authority on Italy, a female entity. If Italy will yield, this will be done with love; if she will refuse, with force:

Italy, gentlemen, wants peace, wants tranquility, wants industrial calm. We will give her this tranquility, the industrial calm, with love, if possible, and with force, if that shall be necessary. […] Everybody knows that there is no personal caprice in my soul, or a lust [libidine] for ruling, or a sinister passion, but only boundless and mighty love for the nation.

(Mussolini 1958, vol. 21: 240)

On this wrote Barbara Spackman (1996: 142), in an incisive analysis of the entire speech:

the introduction of a feminized ‘Italia’ here is not merely a clichéd flourish but rather plays a crucial interpellative role in redirecting the violence that threatened to erupt among men […] toward a ‘woman’ to be loved or raped.

Such ideas were not invented by the fascists nor did they disappear with them. They echo throughout Western culture and find expression, for instance, in the best-selling novels of two authors who have been sometimes charged with displaying some affinities with fascism, Ayn Rand and Ian Fleming.5 In both their books one finds criticism of democracy and equality as shallow fictions, running counter to human nature, specifically that of woman, who intimately longs—as much as she will refuse to admit it, perhaps even to herself—to be dominated by a strong man, and dominated drastically enough to include being raped by him. In Rand’s The Fountainhead, published in 1943—that is when Mussolini and Hitler were still in power—love between the sexes is portrayed as an act of war, a clash between two hostile forces, in the course of which the man subjugates the woman and takes violent possession of her body. Yet rape is not simply an act of imposition, for it accords with the secret longings of the woman herself. The lover of Howard Roark, the novel’s indomitable hero, feels that her body being possessed by him in a scornful way, in the course of an act involving conquest and humiliation, is precisely for what she longs. Any love or tenderness of his part would have left her totally indifferent (Rand 1993: 217). Incidentally or not, one may add, Roark’s profession happens to be the very one that Mussolini chose to underline the innate superiority of man over woman: architecture.

In the James Bond stories similar motifs recur: women covertly desire to be raped. Such messages are conveyed, not by the hero himself, but through his foreign friends who divulge to him, as it were, profound truths about women’s nature. Marc-Ange Draco, the amiable Corsican Mafioso who would become Bond’s father-in-law, tells him about the way he had met his English wife:

“She had come to Corsica to look for bandits”—he smiled—“rather like some English women adventure into the desert to look for sheiks. She explained to me later that she must have been possessed by a subconscious desire to be raped. Well”—this time he didn’t smile—“she found me in the mountains and she was raped—by me.”

(Fleming 2002: 52)

Another good friend of Bond, and a loyal ally of the British secret service, the Turk Darko Kerim, generalizes this into a theory of female desire: “All women want to be swept off their feet. In their dreams they long to be slung over a man’s shoulder and taken into a cave and raped.” And he himself acts upon such insights with his partner: “I got to her place and took away all her clothes and kept her chained naked under the table. When I ate, I used to throw scraps to her under the table, like a dog” (Fleming, 1988: 111–112).6

Such positions are in profound harmony with Nietzsche’s recommendation to treat woman according to Asia’s wisdom. Already quoted above, it is useful to recall its bottom line in order to establish the ideological and political continuity we are facing: “A deep man,” Nietzsche averred (1998: 127), “can think about women only like an Oriental: he has to conceive of woman as a possession, as securable property, as something predetermined for service and completed in it. He has to rely on the tremendous reason of Asia.” It is important to realize, again, that this theory is not confined to the bedroom, or even to relations between the sexes more generally conceived; rather, it ultimately applies to the relations between the manly élite (if it is manly, and an élite which is not, will soon cease to be one) and the feminine masses. Authority and violence have a general social application. Thus, according to Darko Kerim, not only women long to be raped but all his lower-class compatriots:

Kerim harangued the waiter. He sat back smiling at Bond. “That is the only way to treat these damned people. They love to be cursed and kicked. It is all they understand. It is in the blood. All this pretence of democracy is killing them. They want some sultans and wars and rape and fun. Poor brutes, in their striped suits and bowler hats. They are miserable. You’ve only got to look at them.”

(Fleming 1988: 110)7

This is a discourse that presents democracy as a recipe for misery, a denial of one’s drives, while authoritarianism, up to and including its fascist variant, is incomparably more suited to human nature, which is sadistic and masochistic. In this regard the assumption should be avoided that fascism was a merely conservative force, bent on reverting to past norms and codes. Considered as a sexual politics, fascism combined highly conservative tropes, denouncing the alleged depravity of modernity, with radically anti-conservative ones, calling for liberation from the moral inhibitions of Christianity. As historian Dagmar Herzog (2005) forcefully argued apropos National Socialist attitudes to sexuality, German fascism consisted of a complex and contradictory combination of puritan attitudes and dissipation, in a way that managed to confuse even many of its supporters. To begin with, Nazis presented themselves mostly as prim champions of traditional family values determined to put a stop to the lewdness and abandon of the republic; this made many conservatives and devout Christians, both Protestant and Catholic, rally to their cause. Yet alongside this posture there always existed another tendency, that grew in significance as years went by, creating alienation among some of their erstwhile supporters: as part of their criticism of Christianity as a meek and unnatural way of life and their espousal of the purportedly healthy and uninhibited cult of nature of the pagans, many Nazis—doctors, moralists and politicians—saw themselves as destined to do away with the conservative-Christian taboo on sexual lust, vindicating it as beautiful, natural, wholesome, even sacred.

As a result of such ambivalence, alongside Nazis who stressed the sanctity of the family, there were those who encouraged extra-marital sex, arguing, among other things, that it was natural and conducive to a higher birth rate. They also sought to acknowledge “bastards,” and some voices went as far as advocating changing the traditional model of marriage and allowing polygamy—for men. This was not, it is important to clarify, an unqualified permissiveness but one that normally placed the needs and pleasures of men above those of woman; that welcomed only heterosexuality and persecuted homosexuals; and, of course, that encouraged intercourse amongst Aryans and strictly prohibited one involving Jews. Yet it was still inclusive enough to allow those many Germans who did not belong to any of the categories that were discriminated against, a relatively high degree of sexual liberty, in a way which partly continued modern trends, and which may explain part of the support given to Nazism (Herzog 2005: 17). While this (qualifiedly) permissive side of Nazism may surprise, one should realize that sexual freedom does not necessarily entail political freedom. As argued by Eric Hobsbawm, the reverse correlation may more often be established:

Indeed, if a rough generalization about the relation between class rule and sexual freedom is possible, it is that rulers find it convenient to encourage sexual permissiveness or laxity among their subjects if only to keep their mind off their subjection. Nobody ever imposed sexual Puritanism on slaves, quite the contrary. The sort of societies in which the poor are strictly kept in their place are quite familiar with regular institutionalized mass outbursts of free sex, such as carnivals. In fact, since sex is the cheapest form of enjoyment as well as the most intense (as the Neapolitans say, bed is the poor man’s grand opera), it is politically very advantageous, other things being equal, to get them to practice it as much as possible.

(Hobsbawm 2009: 308)

The twofold emphasis of many fascists on the inferiority of woman and the glory of man created a very strong homo-social ethos, celebrating the camaraderie of warriors, their closeness and friendship, sometimes to the point, as evidenced by Jünger, of elevating the wondrous sensual ecstasy of war above the banal release of sexual intercourse. In this way, the boundaries between manhood and femininity were again accentuated. This, however, came with the disadvantage that the homo-social bond, in excluding woman, overemphasized masculinity, so to speak, and thus culminated in a strange reversal whereby manhood was again put in doubt. Instead of facilitating the emergence of a man whose masculinity could no longer be doubted, the fascist ethos paradoxically ran the risk of creating a hybrid man, the homosexual, identified precisely with what fascism came to overcome: indistinct gender boundaries. The hatred of homosexuals was common to all fascisms but Nazism, in particular, humiliated, persecuted, repressed and even murdered thousands of homosexuals, whose concentration-camp uniforms were affixed with a reverse, pink triangle.

The first argument against homosexuality concerned the homosexual’s infertility, undermining the central goal of demographic growth that will provide the human raw material needed to sustain fascist empires. In an important private speech given to his SS subordinates on February 18, 1937 in the Bavarian town of Bad Tölz, Heinrich Himmler began by stressing the demographic peril of homosexuality. He denied any notion that homosexual relationships are a matter of the individual’s private life. Far from being a private matter, it is one of crucial national importance:

The sexual sphere could determine the fate of a people, to life or death, making the difference between world rule and shrinking to the importance of Switzerland. A people of many children can aspire to world hegemony, world control. A people of noble race that has too few children has acquired its ticket to the grave: in 50 or 100 years it will cease to be of importance, in 200 or 500 years it will be dead.

This goal was so important, that in Italy a tax was levied on bachelors, shirking their national duty. Yet in truth homosexuality posed more of a moral than a demographic problem for fascism (and in any case no necessary contradiction exists between homosexuality and procreation): it damaged the image of fascism as manly and tough, pushing it nearer to the presumably weak and feminine model of manhood that it came to displace to begin with. This, more substantial problem, Himmler addresses in direct continuation:

However, beyond the problem of numbers, […] such a people can be obliterated for other reasons. We are a state of men, and for all the flaws in this method, we must cling to it at any price, for there is no better. There have been in the course of history women’s states. You must have heard of the concept “a matriarchal order.” […] For hundreds and thousands of years, the Germanic peoples, and especially the German people, have been ruled by men. Yet this men-state is now undergoing a process of self-destruction on account of its tolerance for homosexuality.

Himmler then goes on to criticize the misogynic tendencies rife in the Nazi movement and the excessive appreciation of male bonding as promoted by such authors as the ultra-nationalist Hans Blüher, since they drive the movement to homosexuality and hence to its destruction. Women should be respected and relationships with them not frowned upon, not because they are equal to men but in order to curb the worst excesses of male bonding and prevent homosexuality. Himmler waxes nostalgic about the good old days of the Germanic ancestors, where the homosexual could without further ado be “drowned in a swamp,” not in order to punish him, “but simply to exterminate abnormal life.” Nazi rule, however, enables contemporary Germans to deal with homosexuals almost as straightforwardly. The head of the SS explains that he has taken the decision to “publicly humiliate” the exposed homosexuals in the organization (he speaks of eight to ten such cases every year), to put them on trial and once they have served their punishment, to take them to “a concentration camp and shoot them while ‘trying to escape.’” A pivotal element in Himmler’s anti-homosexual campaign is the association of homoeroticism with a perverse Judaeo-Christian and proto-socialist assault on healthy, pagan imperialism, a conflict that goes back two thousand years:

A hundred and fifty years ago a thesis was written in a Catholic university under the title: “Does woman have a soul?” This testifies to the tendency of Christianity to destroy woman and expose her inferiority. I am totally convinced that the whole essence of priesthood and Christianity is to establish male erotic bonding, and preserve this Bolshevism, two-thousand years old. I am well familiar with the history of Christianity in Rome, and this strengthens me in my position. I am convinced that the Roman emperors who exterminated the first Christians acted just as we did with the Communists. In those days, the Christians were the worst seditious element in the big cities, the worst Jews, the worst Bolsheviks one can imagine.

Bolshevism in that era had the courage to rise, stepping over the corpse of dying Rome. The priests of that Christian Church—who then defeated the Aryan Church, after tremendous struggles—try, since the 4th or 5th centuries, to obtain the celibacy of priests. […] In its essence, the organization of the Church, in its leadership and its priests, is a male erotic bonding that is terrorizing humanity for 1.800 years.

Discussing this speech, Himmler’s biographer Peter Longerich points out (2012: 237) that the fears it conveys contain a considerable measure of implied self-criticism, since the values of militant, reclusive masculinity that Himmler laments are ones he himself advocated when younger.

Interestingly, this “shadow” of homosexuality that was a source of concern for the fascists, was seized upon by many anti-fascists in the 1930s and 1940s wishing thereby to destroy the manly and powerful image of fascism. As Mark Meyers (2006) demonstrated in a fascinating essay, many critics of fascism in Europe—mainly in France and Germany—instead of taking the fascists to task for their express hostility to the masses and their equally boisterous machismo, tried to attack them from a vantage point that was itself male chauvinist and hostile to the masses. Thus, the fascist leaders, particularly Hitler, were denounced as marionettes of the masses and as feminine, hysterical figures, tainted by latent homosexuality. In this kind of anti-fascist literature, whose representatives include such highly visible figures as Theodor Adorno or Jean Paul Sartre, one can identify the paradoxical seeds of the criticism of fascism as mass hysteria that became so prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s, and that continues to reverberate to our days.

In a sense, fascism could be said to have returned, in theory if not always in practice, to the Victorian model of gender relations, described in Chapter 1, revolving around the principle of the “separate spheres,” according to which man is in charge of the public, the economic and the political domain, and woman runs the domestic, family sphere. Production was deposited in the hands of man, and reproduction in those of woman, or more to the point, in her womb. Zarathustra’s dictum will be remembered, that “Everything about woman is a riddle, and everything about woman has one solution: it is called pregnancy. […] Man should be trained for war and woman for the re-creation of the warrior: all else is folly.” The German philosopher typically opts for rhetorical extremism, and strives for the most provocative possible formulations. Hitler, by comparison, lends the same ideas a much more banal expression:

Whereas previously the programmes of the liberal, intellectualist women’s movements contained many points, the programme of our National Socialist Women’s movement has in reality but one single point, and that point is the child, that tiny creature which must be born and grow strong and which alone gives meaning to the whole life-struggle.

(In Noakes and Pridham 1984, vol. 1: 450)

Hitler also lent the separate-spheres doctrine a very succinct formulation, as if he were the dummy and the Victorian, patriarchal tradition, the ventriloquist:

If the man’s world is said to be the State, his struggle, his readiness to devote his powers to the service of the community, then it may perhaps be said that the woman’s is a smaller world. For her world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home. But what would become of the greater world if there were no one to tend and care for the smaller one? […] The two worlds are not antagonistic. They complement each other, they belong together just as man and woman belong together.

We do not consider it correct for the woman to interfere in the world of the man, in his main sphere. We consider it natural if these two worlds remain distinct. To the one belongs the strength of feeling, the strength of the soul. To the other belongs the strength of vision, of toughness, of decision, and of the willingness to act.

(In Noakes and Pridham 1984, vol. 1: 249)

The trespassing of the boundaries between the spheres on the part of the woman bears destructive consequences, both for the man, who risks losing his employment and his ability to produce, and for the woman herself, who becomes masculine and loses, somehow, her reproductive abilities. Women’s labor, declared Mussolini (1958, vol. 26, 311) in 1934,

brings about her independence, and entails physical and mental conditions that counter birth-giving. The man, confused and above all “unemployed” in all senses, finally gives up the family. […] The exiling of woman from the field of labour will doubtlessly have economic consequences for many families, yet it will restore the pride of legions of humiliated men, and an infinitely greater number of families will at once reenter the national life. It should be realized that the same labour which in woman causes the loss of the attributes of birth-giving, creates in man a very strong manhood, physical and spiritual.

The harking back to lost Victorian times is reflected in the following, pedagogic illustration (Figure 6.1), lamenting the “decline in matrimonial fertility.” It shows the ever increasing number of married women needed to bring a child to the world, from just three in 1890, to ten women in 1932, a year before Nazism began reversing this destructive trend (Helmut 1939: 7).

Women, it is shown, increasingly shun their duties as mothers. As years go by, they become ever more emancipated, hedonist and consumerist. From the chaste Victorian woman depicted in the uppermost frame, clad in heavy garments, one descends—both literally and figuratively—in the direction of the modern, reckless and noncompliant Last Woman: the dresses get shorter, so does the hair, and fashionable handbags, hats, furs and the like multiply. In the opposite page (6), the following explanation shores up the visual message:

In woman’s womb lies the future of the people. Woe to the country whose women have so degenerated that they have lost the natural desire for a child and whose heart is more attracted by delicate manners, the pleasures of life and personal comfort than by a flock of growing kids.

Once installed in power, fascism set about to discontinue the advances made by women, partial and tentative as they may have been. In Germany and Spain, writes Inbal Ofer (2015: 381), fascism brought about “a tremendous retreat in the professional, legal and political status” of women.

In Spain, Franco’s regime restored the Napoleonic code. This code defined married women as legal minors and perpetuated their complete dependency on their husbands not only in managing their property or reaching decisions concerning their children, but also with regards to receiving work permits, relocating, etc.

(Ofer, 2015: 381)

The continuity with 19th-century values and their resumption, however, were only partial. Beyond the sexual defiance that was an important aspect of fascism, it also “upgraded” the Victorian ethos, giving it a comprehensive, totalitarian version in which, theoretically at least, the private space that Victorianism so cherished no longer existed, not even in the family’s bosom. The family became a cell in the national organism, which meant that woman, even at her home, was no longer seen as isolated or protected from public life, but quite the contrary: she was ascribed a vital role in the public arena. To the commitment to the husband and family, emphasized in the 19th century, was now added a further and even more important obligation, to the nation and the race. Bearing offspring, producing the future warriors that the nation needed in order to realize its expansionist ambitions, was a national imperative. In Italy and Germany, fascism encouraged childbirth with marriage and parenthood grants, and economically aiding mothers and their kids, whereas failure to fulfill this duty carried penalties: in Italy, starting from 1927, shirking men, i.e., bachelors, had to pay a “bachelor tax” that in certain ages (35 to 50) amounted to a 25 percent of the income tax. The tax, from which priests and soldiers were absolved, was raised in 1928, 1934 and 1936, so that in the latter year a 30-year-old bachelor needed to pay an income tax twice as high as the normal one. In addition to that, bachelors were discriminated against in the labour market and faced greater difficulties in finding jobs as compared to married men, particularly those with kids (Albanese 2006: 54).

Paradoxically, the fact that the private, feminine and domestic sphere, centering on the family and motherhood, was invested with a civil and national duty of the first order, meant that fascism in a sense introduced many women into politics, albeit of a kind that was largely deprived of the ability to promote women’s independent agendas and defend their collective interests. Women, formerly isolated in the domestic space, suddenly became potential agents of the regime and great efforts were undertaken, crowned with considerable success, to integrate them into diverse fascist organizations, such as the Fasci Femminili in Italy or the NS-Frauenschaft in Germany. Such organizations ultimately counted millions of women and girls as members.8 “Fascist regimes,” writes Kevin Passmore (2002: 126),

invariably implemented repressive measures against women. They attempted to remove women from the labour market and restrict their access to education. […] There was, however, a contradiction in these policies, for […] in order to teach women their domestic duties, fascists mobilized them in organizations linked to the party—to return women to the home, fascism took them out of the home!

Fascism, therefore, perhaps more than any other movement before it, recruited women in great number to its ranks. Women’s organizations were subjected to the male party hierarchy and were used to spread fascist propaganda in as many households as possible; but they also allowed a significant female presence in the public sphere. Fascist women served as welfare workers, organized activities for poor women’s children, distributed clothes and food to the needy and also served as the regimes’ agents in prying into the private affairs of lower-class families, reporting unsocial or politically suspicious behavior and helping to discipline the unruly.

While neutralizing any opposition to the regime, fascism eagerly enrolled women as supporters and mouthpieces. While doubtlessly in many cases filling these activists’ lives with a satisfying sense of purpose, their work was done for the most part on a voluntaristic basis or with a small economic recompense (De Grazia 1992). This also served to enhance the upper-class character of these movements’ leadership, by de facto blocking the path for lower-class women who could not afford to work for, at best, a meager salary (Ofer 2015: 384). In accordance with the fascist basis of social support, most activities were undertaken by, and under the supervision of, upper- and middle-class women, who identified with fascism as a buffer of lower-class discontent and as an agent of national regeneration and ethnic purification, even as some of them contested the crude patriarchal model of fascism and tried to create a more egalitarian gender environment, where women’s social achievements would not be obliterated. As pointed out by Ofer (2015: 383), “for fascist women in general class and national/racial identity were more central than that of gender.” In Italy, women of the nobility occupied most of the key positions in the Fasci Femminili for the duration of the regime (Willson 2003: 24), and while organizations were set up for peasant and working-class women, the motivation to join them seemed to have been primarily pragmatic and in any case women had little genuine alternative: in Italy of the 1930s, without a fascist party card the chances for working-class or middle-class women of getting a job was seriously diminished in many occupations, for instance teaching. And a similar de facto compulsion existed in Germany and Spain.

This development, it is important to clarify, did not simply break with past traditions: during the 19th century and in the beginning of the 20th century the boundaries between the private and the public spheres became in general much more porous, and questions of a presumably personal nature, such as choosing a spouse, giving birth and educating one’s children, were perceived by the eugenic movement in Europe and the United States more and more as issues of decisive importance for the national and racial future, and hence as matters in which the nation—by proxy of its educated and expert representatives—was well entitled to intervene. For Nietzsche it was vital to deposit in the hands of physicians “a new responsibility […], in determining the right to reproduce, the right to be born, the right to live” (Nietzsche 1990: 99). That aspect of fascism thus needs to be seen as a continuation, completion and exacerbation of preexisting trends. The fascist fixation on the strength of the national body, the desire to forge robust and aesthetic men and women and shake off the decadence of urban modernity need also be located within a national and bourgeois tradition developed in the course of the 19th century, as George Mosse analyzed in a series of important studies (especially, Mosse 1997). Similarly, the welfare and nursing tasks fulfilled by women under fascism continued their involvement in similar roles during the First World War, when they were already credited with performing a hugely important national work—in agreement, of course, with their nature and abilities. Such a continuity permitted some women to consider fascism a direct extension of the war experience and to identify with it, and occasionally even to regard it as part of the movement to extend women’s rights, if not in a feminist sense—although a small number of avowed feminists did espouse feminism, such as Teresa Labriola in Italy, Mary Allen in England or Emma Hadlich in Germany—then at least in deepening the bond between women and the nation, an idea that many women of the upper and middle classes found greatly appealing (Willson 2003: 13–14).

The reader may notice a certain unresolved contradiction in the discussion of the fascist attitude to women: strongly conservative and sometimes even outright misogynic, fascism at the same time very successfully recruited women to its ranks and centrally involved them in its task of national and racial palingenesis; contemptuous of women and eager to reinstate masculinity, it also incessantly paid effusive homage to women’s indispensable role in sustaining the new politics; a morbid manifestation of “male fantasies,” to put in Klaus Theweleit’s famous terms, it also corresponded, it turns out, to many female fantasies. So was fascism, with regards to gender relations, a strongly reactionary force, or was it, strangely enough, a highly modern and possibly even progressive and egalitarian force? Even more confusingly, could it have been both at the same time?

Over the last two or three decades, social historians have increasingly moved away from the traditional views of fascism as a misogynic brand of politics, and emphasized the way fascism involved many women in its activities and even opened up avenues of employment and of recreation that have been largely closed to them in the past. Magali Della Sudda (2014: 97) thus draws attention to what she terms “an unacknowledged paradox during the interwar era in France: The presence of female agency within conservative movements. […] [T]he use of gender analysis has challenged the traditional view of Rightist hostility toward women’s emancipation.” And Geoff Read likewise notes (2014: 127) that “Some authors have emphasized that within the far-Right movements of interwar France women achieved a great deal of autonomy. [Caroline] Campbell’s recent doctoral dissertation, for example, emphasizes that women in the CF/PSF were ‘effective sociopolitical actors.’” And while these scholars focus on interwar France, others have reached comparable conclusions with regards to other European fascisms, in Italy, Germany, Britain or Spain. (See, respectively, Graziosi 1995; Koonz 1987; Gottlieb 2003; Ofer 2009.)

While the question is admittedly a difficult one, and the checkered evidence will not admit of a single, let alone a straightforward answer, certain pointers may help us approximate a possible conclusion. To begin with, the fascist break with conservative traditions that have excluded women from the public space should not be overstated. Rather than a break, in fact, fascism seems to have taken over conservative positions and puffed them up, so to speak, pushing them to another level in terms of the sheer scale on which it operated and the radicalism it involved. The very existence of women’s organizations working alongside predominantly male political parties, far from representing an exciting innovation, corresponded to an old European tradition, preceding the First World War, that Della Sudda (2014: 107–108) refers to as “the conjugalist pattern.” While men were engaged in politics more narrowly defined, “social institutions and philanthropic work characterized female citizenship” (99). Fascist movements may have been more successful in mobilizing women, but they can scarcely be credited for introducing the concept. As Geoff Read (2014: 136) argued apropos the Croix-de-Feu, “whatever claim it has to distinctiveness in this regard lies with its succeeding where others failed.” Fascism did not eliminate the old separate–spheres division, as much as it extended these spheres to cover public areas of activity: in this division of labor women were in charge of welfare, persuasion and indoctrination, while men took most of the strategic decisions and ran the military apparatus.

This leads to a second, important aspect of the fascist version of gendered politics, which may be called “the paradox of family.” As we have seen, Hitler was holding fast to a textbook notion of the separate spheres, when distinguishing the greater world of man, from the “smaller world” of woman: “For her world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home.” But, as was already indicated, precisely such a neat Victorian differentiation between public and private spaces, fascism had rendered untenable. The “smaller world” was now by definition anything but small. Underpinning fascism was a familial vision of politics. The nation itself was seen as one huge family connected by organic ties of blood. “Fascism,” according to Daniella Sarnoff (2014: 141), “was, at heart, a domestic ideology.” This, by implication, bestowed on women a great importance, for “as representatives of the family, women also were representative of the patrie—that extended family—and hence they were also representative of the essence of French fascist life” (151). And

while league rhetoric did often replicate the familiar gender hierarchies of traditional family, it was not simply a matter of leaving domestic cares to the women and public labor and politics to men—the family was the highest calling for men and women.

(151)

From this however, it seems to follow that, if women were highly evaluated by the fascists, this was not qua emancipated human beings whose individual wills and desires are now to be considered on equal footing with those of the male, but precisely as servants of the nation’s familial cause. Women were celebrated precisely, and only in so far, as they refused the modern temptation of consumption and self-indulgence; the fascists played upon the clichés of women as responsible savers and housekeepers, selfless beings living for the sake of their offspring. The irony was that, by remaining just as she was or, in case she has strayed from the righteous path, by being pulled back to her former role, woman was suddenly not just a domestic, minor player, but one invested with critical importance, a leading actor in an old-new play. Chauvinist and traditionalist as fascism certainly was, it portrayed both men and women as humble servants of “the extended family,” the nation, which created a certain appearance of equality. But this was, if anything, the equality of slaves: under fascism, rather than women getting to enjoy some of the individual liberties previously available to men, these were denied to men as well. The new-found importance of women under fascism, which bemuse so many scholars, was due not least to their age-old ability—produced and reproduced of course by the hegemonic system—precisely to efface themselves, subordinate themselves to a higher cause. Hence the routine fascist praise for women’s “selflessness.” And since the new human trumpeted by fascism was precisely a self-effacing one, woman, once weaned off her rebellious whims, presented an excellent candidate for the part, and all she had to do was “act naturally.”

Fascism had quelled the revolt of the feminine mass, had tamed the shrew. Woman, under the leadership of a virile élite, was cured of her unnatural fancies and reassumed her submissive position. Therewith the project of the Last Humans—and last women—was cut short, a project intent on ushering in a truly new woman, having her little pleasure for the day and her little pleasure for the night, no longer in thrall to the nation.

Needless to say, the re-emphasis on family, and family duties, was perfectly in line with the conservative restoration, as attested to by the way the tripartite motto of the French revolution, “Liberté égalité fraternité,” was replaced by right-wing mottos such as “Deus, Pátria e Familia” in Salazar’s Portugal, the Vichy regime’s “travail, famille, patrie” (and of course also the famous “Credere Obbedire Combattere” of Italian fascism). Seen under this light, it is tempting to explain the greater fascist success in mobilizing women when compared to other forces on the left, right and center, not with reference to any thrilling new element, let alone emancipatory message, but precisely on account of the way it managed to single-mindedly appropriate, and politically cash in on, very old and commonsensical notions. Fascism succeeded where others faltered, not because it offered any emancipation, but because it was better able to drum up “the woman” in woman.

As rightly observed by Read (2014: 128), the emphasis on the family was not exclusive to fascist rhetoric nor to right-wing circles, but could be found virtually across the political spectrum. Yet such an analogy would go astray if it failed to register the crucial difference in the respective uses of “the family” trope. For in non- and anti-fascist discourses, especially on the left, the family was not primarily the nation’s cell, but the adobe of the Last Human, the safe refuge where she or he were protected from state intervention, relieved of obsequiousness; it was the domain of free consumption, of love making rather than (obligatory) childbearing,9 of crying, cursing and yawning, rather than chanting, saluting and staying awake—apropos Adorno’s perceptive observation (2000: 13) that “under fascism, psychologically, no one is allowed to sleep.”10 As G.K. Chesterton put it in What’s Wrong with the World (1910), rebuffing the elitist attempt to regiment the commoners even in their homes:

For the truth is, that to the moderately poor the home is the only place of liberty. Nay, it is the only place of anarchy. […] He can eat his meals on the floor in his own house if he likes. I often do it myself; it gives a curious, childish, poetic, picnic feeling. […] For a plain, hard-working man the home is not the one tame place in the world of adventure. It is the one wild place in the world of rules and set tasks. The home is the one place where he can put the carpet on the ceiling or the slates on the floor if he wants to. […] Hotels may be defined as places where you are forced to dress; and theaters may be defined as places where you are forbidden to smoke. A man can only picnic at home.

(Chesterton 1987: 72–73)

Yet fascism, like other middle-class movements bent on curtailing the liberties of the masses, needed to smoke the anarchic Last Humans even out of their homes. Under modern conditions, even the old truth of “my home is my castle” proved an intolerable obstacle to fascist ambitions to remold humans. The family was too important to be left to the individual. “So to drink coffee in a few minutes!” dictated from on high Ernesto Giménez Caballero, and further specified what he believed was now required of the citizens: “To talk about what the state finds convenient! To economically regulate meals and hours! To seclude oneself more in the home! To get married! To have sons that will be the Empire’s soldiers of tomorrow!” (In Puértolas 2008: 370).

Another instructive case-in-point of the pro-fascist campaign against the Last Humans is the French pronatalist propagandist Paul Haury, whose criticism of Republican France is illuminatingly discussed by Cheryl A. Koos. Haury was exasperated by France’s declining birth rate, a process that began, he was convinced, with the watershed of modern individualism and hedonism, the fateful year of 1789. During the 1930s he repeatedly lauded the pronatalist policies of Mussolini and Hitler (and also the mystique of the Soviet Union), and this not only because of their presumed beneficial military effect but also, perhaps even primarily, because they attested to these regimes’ determination to put an end to individual anarchy and discipline men and women for a cause higher than themselves. The following harangue against the pettiness of Republican French men is best read as an echo of Zarathustra’s disdain of the Last Humans and their petty pursuits: For 150 years, Haury complained,

French men, have lived for no more than a petit—to acquire a petit house, a petit business, a petit pension […] to protect a petit savings, the petit proprietor, the petit shopkeeper, the petit bureaucrat the object of [their] policies.

(In Koos 2014: 121)

His eventual, warm embrace of the regime of Vichy, for its renewed emphasis on the family—not as the individual’s refuge but as her reproductive prison cell—was a natural outcome of these views.

Fascism, one might say, was paradoxically obsessed with the family at the same time that it obliterated domesticity; fixated on the Heimat, it eliminated home. It sent millions of men away from their homes to face danger and encounter death in foreign lands, and left the women in homes that were under strict vigilance, in the best of cases, and under devastating bombings, in the worst of cases. One of the great postwar films depicting the fascist era in Italy, and precisely its phase of dissolution, is thus very aptly called Tutti a casa—Everybody Go Home. Already discussed in a somewhat different context in Chapter 4, this 1960 film directed by Luigi Comencini is set during the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943 and recounts the journey home of a group of disbanded Italian soldiers. The tragedy of the film is that none of the protagonists actually gets home as one by one they encounter unexpected setbacks and see their most ardent desire frustrated. The soldier coming closest to home is the main protagonist, a junior non-commissioned officer played by Alberto Sordi, who actually finds his way to his apartment, where his old father enthusiastically welcomes him. But even this return proves an illusion: while the home is still physically there, it is still occupied by the die-hard fascists, both inside taken and invaded from the outside: the father, namely, a middle-class cellist, still abides by fascism and would see his beloved son return to the fray. And one of the neighbors, a fascist high officer, enters the home to arrange the redrafting. Sordi thus needs to escape his “home” in the early hours, and ultimately join the resistance.

Similarly, the parenthood, in particular the motherhood, so hailed by fascist regimes, reveals itself under closer scrutiny rather as a form of surrogacy. The parents served as agents of the nation and the race and were raising not so much their own child but tomorrow’s soldier and mother, who will in due time be taken over by the state to fulfill their public duties. And as the child was not really “theirs” in the sense we think of it today, they were less his or her parents and more the tamers, the educators.11 And in case the surrogate parents neglected their duties, the state was entitled to step in and take their child away from them. According to the Nazi view, as explained by historians Noakes and Pridham (1984, vol. 1: 454),

Parents who failed in their duty of bringing up their children in accordance with the precepts of the regime—for example by refusing to send them to the Hitler Youth after 1939—would have their children removed from them and transferred to a state home.

A classic illustration of the claim of Nazism to displace the family and take over its functions, especially if the family in question failed to live up to the fascist ideals, is the 1933 Nazi propaganda film Hitlerjunge Quex [Hitler Youth member Quex, director Hans Steinhoff]. The film tells the story of a Berlin working-class youngster Heini Völker who is drawn to the Nazi youth movement, but is obstructed by his vulgar, drunken communist father. Unable to protect her son from the father’s violence and political extremism, Heini’s kindly but hopelessly inadequate mother tries to induce her own death and that of her son by turning on the gas in their apartment. The son, however, survives the grotesque effort to defend him and, recovering in hospital, is virtually adopted by the Nazis. The extended, genuine family of fascism stands in for the failed nuclear family. As argued by Linda Schulte-Sasse (1996: 256–257) in her insightful analysis of the film:

Nazism increasingly takes over the family’s function; it becomes a totalizing force pervading all aspects of the private and the public sphere. […] Heini is essentially left without a mother—only with a paternal figure of symbolic identification in the Youth Leader whose blond, slim erectness not only fits the “Aryan” ideal more than the corpulent father, but who looks literally more like Heini’s father. It is Nazism itself that takes on the nurturing, enveloping function of Mother.

The fascist ethos expected parents to be ready for every sacrifice, including that of their child, once he grew to become a warrior. As expressed by a female writer in the organ La donna fascista in 1936, amidst the war in Ethiopia:

How sad, how very sad it is to be barren at a time when the motherland is asking for sons! And how proud it makes a mother, rich in children, who is able to offer her country not one but two or three sons. The smile of glory enters homes where brave youths have left empty spaces […]. A mother who, today, bent over an unfolded newspaper, reads of the victorious advance and in her soul follows the route of her soldier son, is happier than a childless woman who watches the others’ fervor as if it were nothing to do with her and smiles: but her soul is far away.

(In Willson 200: 22)

Fascism did its utmost to cultivate fathers and mothers who would readily bind their offspring to the sacrificial altar.

In that sense, too, an abysm stretched between fascism and the Last Humans. Fascist surrogate parenthood, in its instrumental, hegemonic form,12 is very different from the notion of parenthood predominant in mass society, according to which mutual love between the parents and their children is not a means to a higher end but a goal in itself, perhaps the very center of life. The dissonance between the two “models” can be illustrated with the help of two highly successful hit songs, patronized by elitists as “tearjerkers,” made famous by the Jewish-American singer and performer Al Jolson, one of the great popular entertainers of the first half of the 20th century, in The Jazz Singer (1927), the first feature-length “talkie,” and its sequel The Singing Fool (1928). The first song, My Mammy, expresses a son’s limitless love to his mother and the second, Sonny Boy, that of a father to his son. These songs, whose popularity was enormous—Sonny Boy, for instance, sold a million records and was at the top of the American chart for 12 successive weeks—radically differ not only from the fascist notion of parenthood but also from the fascist notion of gender. The male singing in both is not a warrior; he is deeply sentimental—a quintessential “female” characteristic. He foregoes what Hitler referred to as the “greater world” of men and falls back on the feminine “smaller world,” centered on his love for his son, confessing that he would not mind losing all friends, as long as he has his son by his side.

This juxtaposition of fascist ideology with popular songs, one may object, is misconceived; the latter, after all, are not political texts, they are not a program, or a doctrine, or a speech. Moreover, what has Jolson—an American performer—to do with fascism, coming to power in another continent, in countries where few understood English? Yet fascism centrally engaged a protest against “Americanization,” particularly as a manifestation of popular culture. And Jolson’s songs and movies were successful worldwide, including the Republic of Weimar, as attested to by the following placards (Figures 6.2 and 6.3):

A German version of Sonny Boy, moreover, was recorded in 1929 by the highly successful Jewish Austrian tenor, Richard Tauber. The Jazz Singer recounts the personal story of Al Jolson, the son of a Cantor. It describes the difficulties experienced by the singer in the move from the synagogue performances to the world of modern jazz, and the conflict this gave cause to with his father. German moviegoers, among them of course were people of an ultraist nationalist and anti-Semitic persuasion, watched a film rooted in the life of Jewish immigrants in New York, including many songs in Yiddish and Hebrew, whose protagonists have names such as Rabinovitz, Yodelson, Levi, Friedman, Ginsberg, Goldberg and so on and so forth—notice, in the second placard, the unmistakable image of the Cantor. And while the films were not political in any overt sense, they dealt intensively with a question which for the fascists was fundamentally political: the relationships between parents and children and the significance of the family. And here it may be assumed that the millions of viewers whose tears were jerked in these movies, including many German ones, and all of whom were themselves either parents or children (or both at the same time) found in them an example for a familial rapport with which they could identify and which seemed right to them. And this model, which may be termed that of the “Yiddishe Momme,” the fascists tried to uproot in order to make way for the surrogate parenthood they advocated and on which they sought to erect their imperialistic project. This shows the correctness of Bertolt Brecht’s observation, recalled by Walter Benjamin, that the struggle against fascism is never merely “political” in the narrow sense of the term but is conducted comprehensively in all spheres of life and of culture, including the seemingly most innocuous ones:

A few days later [Brecht] added yet another argument in favour of including the Children’s Songs in the Poems from Exile: “We must neglect nothing in our struggle against that lot. They’re planning […] [c]olossal things. Colossal crimes. Every living cell contracts under their blows. That is why we too must think of everything. They cripple the baby in the mother’s womb. We must on no account leave out the children.”

(Benjamin 1998: 120)

Another interesting contestation of the fascist model of parenthood and of its elimination of home, is found in Gli anni ruggenti (Roaring Years), a 1962 film by the great director and pioneering postwar critic of Italian fascism, Luigi Zampa. In this film, one of many cinematic takes on Nikolai Gogol’s Revizor, an insurance salesman played by Nino Manfredi is mistaken for a highly-placed fascist hierarch visiting a small town and is slavishly courted by the corrupt fascist élite, wishing to ingratiate itself with Rome. Throughout the film, Manfredi, oblivious of the error but enjoying the attention he is given, serves as a mouthpiece of the Last Humans’ philosophy. At one point he proclaims: “Our slogan is: better insurance without an accident, than an accident without insurance!” When asked if this is one of Mussolini’s dictums he answers, taken aback: “No, this is of Beppe Daioli, our publicity agent.” The very fact that he sells insurance, of course, is symbolic of his anti-Nietzschean stance, defying the fascist tenet of “live dangerously!” He falls in love with the beautiful daughter of the fascist city mayor and they are engaged to be wed, but when he confesses that he is a mere insurance salesman the girl responds that in that case she can no longer marry him, although she still loves him:

ELVIRA: I know, you will be a good husband […] and on Sundays you will take everyone for ice cream.

OMERO [MANFREDI]: And what of it? You don’t like ice cream?

ELVIRA: You see, I may be stupid, but I have always dreamt of a man full of medals, a strong and valorous man, ready to fight in peace and in war for the ideals of the patria.

To which the salesman responds: “Elvi, but do you want a husband, or a monument?”

The consumption of ice cream is symptomatic, too. Much more than a cold, refreshing dessert is involved. It stands, rather, for the ideal of the good, unassuming life, everything that for a fascist must go under the radar. One can of course be a fascist and consume ice cream, too; but not this ice cream, which is a token of peace, simple enjoyment and human fraternity. Only the Last Humans can savor it; that is their prerogative and the reason that, despite all Nietzschean defamations, their appeal can never be truly defeated.

According to the historian Andreas Huyssen (1986: 52–53), as will be recalled from the discussion in Chapter 2, critics of mass culture frequently construed “mass culture as woman,” identifying it with “an engulfing femininity” and a chronic loss of masculinity. Yet Huyssen was interested less in mass culture itself than in the way it was interpreted by the élites. An examination of the actual Western mass culture of these decades (the first half of the 20th century) reveals, as the above examples indicate, that this widespread association was not a mere slander or a sheer fantasy. Fascinatingly, contemporary mass culture did in fact challenge the rigid boundaries and hierarchies of the past, including the stereotypes of “femininity” and “masculinity”; so one finds it on many occasions “reacting” to fascism even when this is not done directly or even intentionally. An expression of such—objective—anti-fascism in mass culture is the 1941 hit song of the Ink Spots (also performed by others), I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire. The male protagonist avows that he has no ambition left for worldly acclaim, no desire to set the world on fire, his only goal being to kindle a flame in his lover’s heart. The song was highly successful with the public, reaching the fourth place in the American chart while another version, later that year, after Pearl Harbor, even reached the number one spot. The song variously challenges the “separate spheres:” the “female” sentimentality expressed by the male singers; the falsetto voices highly typical of this period that in themselves defy gender classification; and finally the messages of pacifism, containing a renunciation of the man’s “greater world” and the focus on the woman’s “smaller world” of romantic love. Reflected here, I suggest, is the desire of the masses for relaxation, for a moving away from war and its glorification, from the “manhood” that has demanded so many sacrifices, at the time that fascism is hard at work patrolling and reinforcing the old borders, surrounding them with still more barbed wire.

This throws into vivid relief the profound inadequacy of such left-wing criticisms of mass culture that have turned against it its effeminacy and defiance of fixed gender boundaries instead of recognizing precisely this element as one of its great achievements. Given his left-wing Nietzscheanism it is not surprising that Adorno, notably, could not offer any aid to the Last Humans in their hour of greatest need but instead chastised them, repeatedly attacking jazz for its sexual hybridism. “The aim of jazz,” he contended, is

a castration symbolism. ‘Give up your masculinity, let yourself be castrated,’ the eunuchlike sound of the jazz band both mocks and proclaims, ‘and you will be rewarded, accepted into a fraternity which shares the mystery of impotence with you.’

(Adorno 2002: 352)

Elsewhere (497) he derisively wrote of “the sexless saxophone,” managing to see the point exactly, and miss it altogether.

1As comprehensively discussed in the various essays gathered in Gilman et al. (1993).