Summary

Arthritis is the term used to describe a group of conditions characterized by inflammation of the joints. The two commonest types are osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). OA is caused by local inflammation at the synovial joints often caused by overactivity of the body’s normal repair processes. RA is a systemic disease caused by chronic inflammation that most commonly affects synovial joints but can affect almost any part of the body. The specific symptoms depend on the type of arthritis, but in general they include pain, stiffness, inflammation or swelling of the joint, and a progressive deformity or loss of function.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence It is difficult to estimate incidence as people present at all stages of disease.

• Prevalence Worldwide there are estimated to be 151.4 million people with OA and 23.7 million people with RA.

1 In the UK 9 million people are estimated to have arthritis including 8.5 million who are estimated to have joint pain caused by OA.

2 In England, there were 290 000 admissions to hospital with arthritis in 2008/09.

3

• Case fatality Very low, but depends on the severity of disease and the presence of other related conditions and extra-articular manifestations.

• Mortality Globally there were 7000 deaths from OA and 26 000 deaths from RA in 2004; most deaths occurred in women.

1 There were 1257 deaths from arthritis and arthrosis in 2008 in England and Wales.

4

• Disability Worldwide arthritis was responsible for 20.6 million DALYs in 2004 when there were an estimated 55.3 million people with moderate or severe disability as a result of arthritis.

1

• Time The prevalence of OA is likely to increase as the population ages.

• Person OA is predominantly a disease of middle to late age and is more commonly seen in women. RA can present at any age, but is most common between 30–50 years. Pre-menopausal women are 3x more likely to be affected by RA than men, but this difference disappears post-menopause.

• Place Occurs worldwide, but most cases are found in Europe and the Western Pacific region (including Australia, China, and Japan).

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Sex (women are more commonly affected); age (OA is rare before 40 years and RA most commonly presents between 30–50 years); genetic (HLA genotypes associated with RA); family history.

2

• Modifiable risk factors OA: obesity; previous trauma or preexisting joint damage.

Prevention

• Primary prevention OA: weight loss.

• Secondary prevention RA: disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; corticosteroids; surgery.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention OA: joint replacement; physiotherapy. RA: physiotherapy; surgery.

Common types of arthritis

• Osteoarthritis.

• Rheumatoid arthritis.

• Seronegative spondyloarthritis:

• Ankylosing spondylitis.

• Psoriasis.

• Inflammatory bowel disease.

• Reactive arthritis (post-infection).

• Septic arthritis.

• Crystal arthritis, e.g. gout and pseudogout.

• Trauma, e.g. haemarthritis.

Summary

Asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by reversible narrowing of the airways in response to an allergen or other stimulus (e.g. cold air, atmospheric pollution, or exercise). Symptoms are often worse at night and include wheeze, cough, chest tightness, and episodes of shortness of breath.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Most new cases occur in children.

• Prevalence Worldwide there are estimated to be 234.9 million people with asthma of whom 28.8 million are in Europe.

1 In the UK there are estimated to be 5.4 million people with asthma.

2 In England, there were 64 000 admissions to hospital for asthma in 2008/09.

3

• Case fatality Overall very low, but depends on the severity of disease. Deaths mainly occur during an acute episode of airway narrowing. Acute attacks can be prevented with adequate medical care and the outcome of an attack is often dependent on urgent access to medical treatment.

• Mortality Globally 287 000 deaths were caused by asthma in 2004.

1 Most deaths occurred in middle- and low-income countries.

1 There were 1036 deaths from asthma in 2008 in England and Wales.

4

• Disability Worldwide asthma was responsible for 16.3 million DALYs in 2004 when there were an estimated 19.4 million people with moderate or severe disability as a result of asthma.

1

• Time The number of new cases of asthma has increased dramatically over the last 40 years; however this trend is now levelling off.

5 Prevalence is likely to remain high as it is a chronic condition that often presents in childhood.

• Person Asthma is predominantly a disease of childhood and symptoms often decrease with age. However a proportion of people will develop asthma later in life.

• Place Worldwide, but most morbidity and mortality is seen in middle- and low-income countries.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (young); family history of atopy.

• Modifiable risk factors Maternal smoking; environmental tobacco smoke;

6 occupational exposure to allergens (cause 9–15% of adult-onset asthma).

7

Prevention

• Primary prevention Maternal smoking cessation.

• Secondary prevention Avoid exposure to allergen (e.g. house dust mite, environmental tobacco smoke, occupational agent); smoking cessation.

2

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Bronchodilators; corticosteroids; anti-inflammatory agents and antibiotics in some cases.

Summary

Bladder cancer typically presents with painless haematuria, abnormal micturition (painful, sudden, frequent) or recurrent urinary tract infections. It is more common in men than women. Worldwide, its distribution reflects the prevalence of smoking, occupational exposure to chemicals, and schistosomiasis.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, it is the 6

th commonest cancer with 323 000 new cases in 2008.

1 In the UK it is the 7

th commonest cancer with 10 100 new cases in 2007.

3

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 1.1 million people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with bladder cancer within the previous 5 years.

2 In England, there were 86 000 admissions to hospital with bladder cancer in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In the UK 5-year survival is 66% for men and 57% for women.

3

• Mortality Worldwide it is the 10

th commonest cause of cancer death with 150 000 deaths in 2008.

5 In the UK it is the 8

th commonest cause of cancer death.

3 There were 4475 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

6

• Time Age-specific incidence rates have fallen over the last 10 years in the UK and mortality rates have declined over the last 30 years, partly due to the reduction in smoking prevalence.

3

• Person In developed countries it tends to affect men over the age of 40 who smoke or have had occupational exposure to chemicals. In the Middle East and Africa it tends to affect people with schistosomiasis.

3

• Place In developed countries distribution reflects smoking and occupational chemical exposure while in developing countries distribution reflects prevalence of schistosomiasis. It is the 2

nd commonest cause of cancer deaths in men in the Eastern Mediterranean region

5 and the highest death rate is seen in Egypt.

7

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (85% aged >65 years); ethnicity (highest risk in white); family history.

3

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking; environmental tobacco smoke; occupational chemical exposure (polycyclic hydrocarbons,

8 e.g. oil refining; arylamines, e.g. manufacture of plastics or rubber); schistosomiasis; recurrent bladder infection.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Smoking cessation; control occupational exposure to chemicals (e.g. see the UK Health and Safety Executive website:

http://www.hse.gov.uk

http://www.hse.gov.uk); early recognition and treatment of schistosomiasis and other bladder infections.

• Secondary prevention Screening is not currently recommended.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; regular cystoscopy to identify recurrence.

Summary

Cancer of the brain, central nervous system (CNS), or meninges is rare. It typically presents with headache or seizure but symptoms can be more specific depending on the site of the tumour. Better imaging has led to an increase in diagnosis but mortality has remained fairly constant.

Descriptive epidemiology (meninges, brain, and CNS)

• Incidence Worldwide there were 238 000 new cases of brain and CNS cancer in 2008.

1 In the UK it is the 16

th most common cancer with 4676 cases in 2007.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 277 000 people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with cancer of the brain and CNS within the previous 5 years.

5 In England and Wales, there were 17 079 admissions to hospital with cancer of the brain, meninges, and CNS in 2008/09.

3

• Survival Depends on age, type of tumour, grade, and stage at presentation. In the UK 5-year survival is 11% in men and 16% in women.

2 Survival is much higher in people <40 years (∼50% 5-year survival).

2

• Mortality Worldwide, there were 175 000 deaths from cancer of the brain and CNS in 2008.

1 In the UK it is the 13

th most common cause of cancer death.

2 There were 3313 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

4

• Time In the UK there was a slight increase in age standardized incidence from 1970–1990 but since then, rates have been relatively constant.

2 This increase is in part due to better imaging techniques (CT and MRI) leading to more and earlier diagnoses.

• Person It is the commonest site of solid tumours in children but most cases occur in adults.

2

• Place Highest age-standardized incidence rates are seen in North America, Europe, Australasia, and Brazil.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; genetic (e.g. neurofibramatosis).

• Modifiable risk factors Radiation; immunosuppression (cerebral lymphoma).

Prevention

• Primary prevention No prevention.

• Secondary prevention Screening is not recommended.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; radiotherapy; chemotherapy; physiotherapy; occupational therapy.

Summary

Almost 1 in 3 cancers diagnosed in women in the UK is a breast cancer. The introduction of screening has led to cancer being detected at an earlier stage and a related fall in mortality. The global trend is towards an increase in incidence as women have fewer children, later in life.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, it is the 2

nd commonest cancer in women with 1.1 million new cases in 2004.

1 In the UK it is the commonest cancer in women with 47 700 new cases in 2009.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 4.4 million women were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with breast cancer within the previous 5 years.

3 In England, there were 167 000 admissions to hospital with breast cancer in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In the UK 5-year survival is 82%.

2

• Mortality Worldwide it is the commonest cause of cancer death in women with 519 000 deaths overall in 2004 (<0.4% of deaths occurred in men).

1 In the UK it is the 3

rd commonest cause of cancer death.

2 There were 10 440 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

5

• Time Since the introduction of screening in the UK, 20 years ago, there has been an increase in age-standardized incidence and a decline in mortality.

• Person <1% of all cases occur in men.

• Place Most cases occur in Europe and the Americas and it is the 9

th commonest cause of death in high-income countries.

1 Rates are traditionally lower in low-income countries and Eastern Asia, which partly reflects the different trends in family size and breastfeeding. However incidence is anticipated to increase in all countries as women change their reproductive and lifestyle patterns.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (80% of cases in women >50 years)

2; sex (>99% in women); family history; genetic (e.g. BRAC1 and 2); exposure to oestrogen (increased risk with early menarche and late menopause); certain benign breast conditions.

• Modifiable risk factors Hormone replacement therapy (HRT); oral contraceptive pill (OCP); reduced risk in parous women and those who breastfeed; alcohol; post-menopausal obesity.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Breastfeeding; weight control; sensible alcohol consumption; prophylactic mastectomy in women with genetic high risk.

• Secondary prevention Most high-income countries have a population-based screening programme for breast cancer. In the UK, the NHS Breast Screening programme was established in 1988. It offers screening to all women over the age of 50 and uses a call and recall system to invite women aged 50–70 registered with a GP for screening every 3 years.

6

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; chemotherapy; hormonal therapy; radiotherapy; post-mastectomy surgical reconstruction or prosthesis.

Summary

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is used to describe all disorders of the heart and blood vessels (including cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, and peripheral vascular disease). Worldwide it was the leading cause of death in 2004, responsible for 31.5% of deaths in females and 26.8% of deaths in males.1 CVD is also the commonest cause of death in the UK and is responsible for approximately 200 000 deaths per year, 35% of all deaths.2 This section covers the major types of CVD associated with atherosclerosis. Raised BP and hypertension are important risk factors for the development of atherosclerosis, which is in turn the commonest underlying disease process in cerebrovascular disease and coronary heart disease.

Atherosclerosis

A build-up of fatty deposits (atheroma) in the arteries is called atherosclerosis. Raised BP and hypertension can increase the risk of atheroma forming in arteries by damaging the lining of the vessels and disrupting blood flow. When formed, atheroma narrow or stiffen vessels further disrupting blood flow. Atherosclerosis is ubiquitous; it begins to appear in teenagers and continues to increase with age.3 It is often clinically silent but it presents when an artery has been narrowed to the point that the blood flow is insufficient to meet the metabolic demands of the tissue. The clinical presentation depends on which artery is most affected but the commonest presentations are cerebrovascular disease (stroke), coronary heart disease and peripheral arterial disease.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Low-fat diet; smoking cessation; NHS Health Check;

4 US Medicare provides screening for total and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides every 5 years in people without CVD;

5 physical activity; sensible alcohol intake.

• Secondary prevention Smoking cessation; low-fat diet; physical activity; control of hypertension; cholesterol control.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Smoking cessation; hypertension and cholesterol control; interventional procedures to widen narrowed arteries.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; sex (more common in men); family history.

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking; high BP; high cholesterol; high saturated fat intake; diabetes; physical inactivity; obesity.

NHS Health Check4

NHS health checks were introduced in England in 2009. All adults aged 40–74 years without a history of heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes, or stroke are invited, every 5 years, to attend a health check to assess their risk of developing these conditions. By offering appropriate early intervention, this scheme is expected to save 650 lives and prevent 1600 heart attacks and strokes each year.

Summary

The term cerebrovascular disease describes a range of conditions characterized by abnormal, damaged, or blocked blood vessels that lead to disrupted blood flow to the brain. Stroke is the commonest clinical presentation of cerebrovascular disease and is an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Raised BP is the commonest modifiable risk factor for stroke.1 The main categories of cerebrovascular disease are:

• Cerebral infarct.

• Intracerebral haemorrhage.

• Subarachnoid haemorrhage.

• Other non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence In 2004 there were estimated to be 9 million first instances of stroke worldwide.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide it is estimated that there were 30.7 million people alive in 2004 who had survived a stroke.

2 In England, there were 98 200 admissions to hospital with cerebrovascular disease in 2008/09.

3

• Case fatality A systematic review found that early case fatality from stroke (21–30 days) was between 17–30% in high-income countries and between 18–35% in low- and middle-income countries depending on the cause.

4

• Mortality Worldwide it was responsible for 5.7 million deaths in 2004, almost 10% of all deaths, making it the 2

nd commonest cause of death.

2 Although the mortality is high, it is only responsible for 4.2% of all years of life lost (this measure takes into account the age at death).

2 There were 46 446 deaths in England and Wales in 2008.

5

• Disability Worldwide cerebrovascular disease was the 6

th most common cause of disability, responsible for 46.6 million DALYs in 2004. At this time there were an estimated 12.4 million people worldwide with moderate or severe disability as a result of cerebrovascular disease.

2

• Time By 2030, cerebrovascular disease is predicted to grow in importance and become the 4

th leading cause of DALY’s worldwide.

2 In high-income countries age-adjusted stroke incidence has fallen by >40% in the last 40 years but has more than doubled in low- and middle-income countries.

4

• Person More common with age; more common in people with raised BP.

• Place Cerebrovascular disease occurs worldwide. Although it is a commoner cause of mortality and morbidity in high-income countries, the majority of deaths and DALYs are found in middle- and low-income countries.

2 It is expected to grow in importance in low- and middle-income countries, partly related to the prevalence of smoking in these regions and the general shift from infectious to chronic conditions.

2

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; family history.

• Modifiable risk factors High BP; smoking; obesity; physical inactivity; diet (high salt, high saturated fat); excess alcohol consumption; diabetes; psychosocial stress; relevant cardiac disease (e.g. atrial fibrillation); apolipoprotein ratio.

1 Evidence for the role of cholesterol in the aetiology of stroke is equivocal.

6

Prevention

• Primary prevention BP control; smoking cessation; maintain healthy weight; healthy diet (reduced salt (<6g/day), high fruit and vegetables (5-a-day), low saturated fat); diabetes control; sensible alcohol consumption.

• Secondary prevention Prompt treatment of transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke can reduce the risk of an early recurrent stroke by 80%;

7 BP control; smoking cessation; statin therapy; diabetes control.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Thrombolytic treatment (where appropriate); physiotherapy; occupational therapy; regular exercise; smoking cessation.

Summary

Cancer of the cervix is the commonest cancer in Africa and South East Asia, despite it only occurring in women. And in these regions it is the commonest cause of cancer death in women. Many high-income countries have introduced screening programmes which have led to a considerable fall in the number of cases. The main cause of cervix cancer is infection with a high risk type of human papillomavirus (HPV) and vaccination against this infection is now available in some countries.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, there were 489 000 new cases in 2004.

1 It is the only cancer with a higher incidence in Africa and South East Asia than in developed countries.

1 In the UK it is the 11

th most common cancer in women with 2830 cases in 2007.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 1.4 million women were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with cancer of the cervix within the previous 5 years.

3 In England, there were 8891 admissions to hospital with cancer of the cervix in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In the UK 5-year survival is around 2/3 overall, but it is >85% in women <40 years.

2

• Mortality Globally it is the 5

th commonest cause of cancer death in women with 268 000 deaths overall in 2004 but it was the commonest cause of cancer death in women in Africa and South East Asia.

1 There were 830 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

5

• Time Since the introduction of screening in the UK, incidence rates have almost halved (in last 20 years).

2

• Person A disease of women, over half the cases in the UK are diagnosed in women <50 years.

2

• Place Occurs predominantly in lower-income countries. Despite this being a disease only seen in women, it was the commonest cancer in Africa and South East Asia in 2004.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Sex.

• Modifiable risk factors HPV including types 16 and 18; condom use/delayed sexual debut/fewer partners; tobacco smoking; immunosuppression; long-term use of oral contraception; early pregnancy; number of pregnancies; vaccination.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Most high-income countries have a population-based screening programme. In the UK, the NHS Cervical Screening programme was established in 1988. It offers screening to all sexually active women aged 25–64 years and uses a call and recall system to invite women registered with a GP, for screening every 3–5 years.

6 Unlike other screening programmes, it is not designed to detect cancer, but instead looks for early abnormalities that can develop into cancer without intervention.

6 HPV vaccination has recently been

developed to help prevent cancer of the cervix and is approved for use by many countries.

7 In 2008 the UK began to offer the HPV vaccine routinely to girls aged 12–13 years.

8

• Secondary prevention Cervical screening.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy.

Summary

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. It is characterized by airflow obstruction, defined as a FEV1* <80% predicted or FEV1/FVC** <0.7. As it is predominantly caused by smoking, global and temporal distributions mainly reflect patterns in smoking prevalence. Smoking cessation is the most important intervention. At any stage it can slow down disease progression and postpone disability.

*FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second. ** FVC, forced vital capacity.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence It is difficult to estimate incidence as many cases are undiagnosed and people present at all stages of disease. It is estimated that 20% of all smokers will develop COPD.

1

• Prevalence Worldwide it is estimated that there were 63.6 million people with symptomatic COPD in 2004.

2 Based on information from primary care, the prevalence of COPD in adults in England was 1.5% (834 000 people) in 2008.

3 However it is thought that there are an additional 450 000 undiagnosed people in the UK.

4 In England, there were 119 000 admissions to hospital with COPD in 2008/09.

5

• Case fatality Depends on severity of underlying disease and the occurrence of acute exacerbations.

• Mortality Worldwide it was responsible for 3 million deaths in 2004 making it the 4

th commonest cause of death.

2 There were 24 816 deaths in England and Wales in 2008, approximately 1 in every 20 deaths.

6

• Disability Worldwide COPD was the 13

th most common cause of disability, responsible for 30.2 million DALYs in 2004 when there were an estimated 26.6 million people worldwide with moderate or severe disability as a result of COPD.

2

• Time The burden of disease caused by COPD is expected to dramatically rise. It is predicted that in 2030 it will be the 5

th leading cause of global DALYs.

2

• Person Rare in people <40 years, but it is the amount of tobacco and duration of smoking that is the most important factor.

• Place Most deaths occur in middle-income countries and most cases are found in the Western Pacific region.

2 The disease is relatively uncommon in Africa.

2 It is a leading cause of disability in middle- and high-income countries, specifically the Americas and the Western Pacific Region.

2 The distribution of COPD is likely to shift from high- and middle to middle- and low-income countries as smoking patterns change.

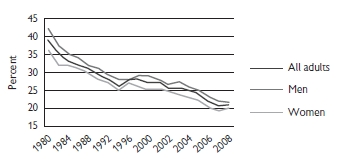

Global smoking prevalence7,8 (Fig. 12.1)

• Men 35% of men in developed countries and 50% of men in developing countries smoke. In China alone there are >300 million male smokers.

• Women The pattern is reversed in women. 22% of women in developed countries and 9% of women in developing countries smoke.

• It is anticipated that by 2030 there will be >3 billion smokers worldwide.

• 1 in 2 smokers will die from smoking related disease.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Genetic (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency).

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking (80% of cases in UK); environmental tobacco smoke; occupational chemical exposure (e.g. coal dust, cadmium—estimated to cause or make worse 15% of cases);

9,10 indoor air pollution (in low-income countries indoor air pollution from biomass fuels used in heating and cooking causes large burden of COPD);

11 outdoor air pollution triggers acute exacerbations.

Prevention

• Secondary prevention Smoking cessation; control outdoor air pollution.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Smoking cessation; drug treatment (can include beta-2 agonists, mucolytics, theophylline, corticosteroids depending on severity

12); home oxygen; pulmonary rehabilitation; non invasive ventilation.

Summary

Cirrhosis is the result of chronic liver damage from any cause. This diverse aetiology can make it difficult to interpret patterns in this diagnosis and often more detailed analysis of the underlying conditions is more informative.

Examples of conditions that cause cirrhosis of the liver:

• Chronic viral hepatitis (10–20%).

*

• Autoimmune hepatitis.

• Drugs e.g. methotrexate.

• Primary/secondary biliary cirrhosis (5–10%).

*

• Inherited conditions including haemochromatosis (5%)

*, Wilson disease, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

• Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

• Cryptogenic.

*Source of prevalence data1

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence and prevalence Difficult to determine as the condition can remain clinically silent for many years.

• Mortality Worldwide it was responsible for 772 000 deaths in 2004, making it the 18

th commonest cause of death.

2 There were 2660 deaths from cirrhosis of the liver in England and Wales in 2008.

3

• Disability Worldwide, cirrhosis of the liver was outside the top 20 leading causes of DALYs in 2004, but it was a significant cause of disability, responsible for 13.6 million DALYs.

2

• Time In the USA, the liver cirrhosis age-adjusted death rate gradually increased from 1950, peaked in 1973 and has been in decline since.

4

• Person Worldwide, it causes more deaths in men than women (510 000 compared to 262 000 in 2004).

2

• Place The highest burden is seen in the European region where cirrhosis of the liver was the 9

th leading cause of DALYs in 2004.

2

Risk factors

• Related to the underlying cause of liver damage.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Prevent conditions that progress to cirrhosis (e.g. hepatitis B and C infection; excessive alcohol consumption; obesity) and prompt recognition of liver disease with appropriate treatment to reduce progression to cirrhosis (e.g. haemochromatosis).

• Secondary prevention Avoid alcohol; vaccination for hepatitis B; specific management of the underlying condition.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Liver transplant (the British Liver Trust report that 700 people a year, in the UK, undergo a transplant to survive).

5

Summary

Colorectal cancer presents with either general symptoms such as weight loss or anaemia or specific symptoms including altered bowel habit, abdominal mass, abdominal pain, or blood in the stool. Incidence is anticipated to rise in low- and middle-income countries as rates of obesity and physical inactivity increase.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, it is the 3

rd commonest cancer with 1.1 million new cases in 2004.

1 In the UK it is the 3

rd commonest cancer with 38 610 new cases in 2007.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 2.8 million people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with colorectal cancer within the previous 5 years.

3 In England, there were 137 600 admissions to hospital with colorectal cancer in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In England and Wales 5-year survival is ∼50%.

2

• Mortality Worldwide it is the 4

th commonest cause of cancer death in men and women and the 20

th cause of death overall with 639 000 deaths in 2004.

1 In the UK it is the 2

nd commonest cause of cancer death.

2 There were 13 934 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

5

• Time Rates are likely to increase in low- and middle-income countries as obesity levels rise. Incidence and mortality have fallen in the USA over the last 10 years.

6

• Person In the UK, 84% of cases occur in people aged >60 years.

2 Men and women are equally affected.

• Place Occurs worldwide, higher rates in high-income countries.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (>80% cases aged >60 years); family history (lifetime risk of death from colorectal cancer is 1 in 6 for people with 2 1

st-degree relatives with the condition and 1 in 10 for people with one 1

st-degree relative aged <45 with the condition)

7; genetic (FAP (familial adenomatous polyposis) and HNPCC (hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer) cause 1 in 20 cases

2 and the lifetime risk of death from colorectal cancer is 1 in 2.5 for people with FAP and 1 in 2 for people with HNPCC

7); inflammatory bowel disease (1 in 100 cases).

2

• Modifiable risk factors Diet (low in fibre, fruit and vegetables and high in processed and red meat all increase risk); obesity; smoking; physical inactivity.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Diet; exercise; smoking cessation.

• Secondary prevention The NHS Bowel Cancer Screening programme was introduced in England in 2006.

8 All adults aged 60–69 years are invited to participate using a call and recall system based on GP registers. Participants provide a sample for faecal occult blood (FOB) testing every 2 years. Participants with a positive FOB, estimated to be 2%, proceed to colonoscopy where a polyp is found in 40% and

a cancer in 10%. (NB in Scotland, adults aged 50–74). The UK British Society of Gastroenterology recommends screening for people at high risk of colorectal cancer, including people with colonic adenomas, inflammatory bowel disease, acromegaly, a uretero-sigmoidostomy, a family history of colorectal cancer or a genetic predisposition.

7

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; regular colonoscopies (5-yearly until aged 757).

Summary

Coronary heart disease (CHD) occurs when blood flow to the heart through the coronary arteries is impaired. The main clinical syndromes are angina and acute myocardial infarction (MI). Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for CHD. Mortality is high following an acute MI but this can be improved with prompt medical treatment.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence There were estimated to be 100 883 MIs in England in 2007

1 and 1.1 million MIs per year in the USA.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide it is estimated that there were 54 million people with angina in 2004.

3 There were 303 500 admissions to hospital in England with CHD in 2008.

4

• Case fatality In the USA almost half of all people who have an acute MI will die.

2

• Mortality Worldwide it was the commonest cause of death in 2004, responsible for 7.2 million deaths, over 12% of all deaths

3. It is responsible for 5.8% of all years of life lost.

3 There were 76 985 deaths in England and Wales in 2008 from CHD.

5

• Disability Worldwide it was the 4

th most common cause of disability, responsible for 62.6 million DALYs in 2004. At this time there were an estimated 23.2 million people worldwide with moderate or severe disability as a result of CHD.

3

• Time The burden of disease caused by CHD is expected to rise by 2030, making it the 2

nd commonest cause of global DALYs.

3 In the UK the incidence of MI is estimated to be reducing by 2% per year in people <70 years.

1

• Person Incidence increases with age.

1 Men have a higher incidence than women, but this difference reduces after the menopause.

1 More common in South Asian men and women in UK.

1

• Place CHD is the commonest cause of death in high-income countries and the 2

nd commonest cause of death in middle- and low-income countries.

3 It contributes a higher proportion of DALYs in high- and middle income countries compared to low-income countries.

3 In the UK, studies have shown that MI incidence and mortality is higher in Northern England, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; family history; sex (men >women).

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking; cholesterol; physical inactivity; diet (high fat, low fruit and vegetables); high BP; diabetes.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Smoking cessation; BP control; maintain healthy weight; healthy diet (high fruit and vegetables (5-a-day), low saturated fat, reduce salt); diabetes control; physical activity.

• Secondary prevention Smoking cessation; BP control; cholesterol control; diabetes control; coronary artery intervention.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Smoking cessation; drug treatment; surgery.

Summary

Dementia is a group of conditions that cause progressive decline in higher cortical function without affecting consciousness. There are multiple aetiologies but age is the main risk factor and epidemiological trends reflect the age distribution of populations.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence It is difficult to estimate incidence as many cases are undiagnosed and people present at different stages of disease.

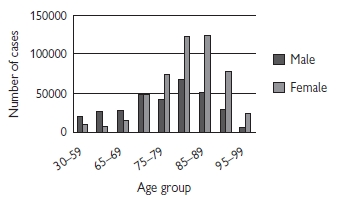

• Prevalence Worldwide, there were an estimated 24.2 million people with dementia in 2004.

1 The NHS estimates that there are 570 000 people in England with dementia (

Fig. 12.2).

2 In England, there were 14 000 admissions to hospital with dementia in 2008/09.

3

• Mortality Worldwide there were 492 000 deaths from dementia in 2004.

1 Dementia is the 6

th commonest cause of death in high-income countries.

1 There were 16 610 deaths in England and Wales in 2008.

4

• Disability Worldwide dementia was responsible for 11.2 million DALYs in 2004 when there were an estimated 14.9 million people with moderate or severe disability as a result of dementia.

1 It is the 4

th leading cause of DALYs in high-income countries.

1

• Time The prevalence and burden of disease will increase as the population ages.

• Person As age is the major risk factor, most cases are women.

• Place Most cases are seen in countries with aging populations: the Americas, Europe and the Western Pacific.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; genetic (e.g. Huntingdon’s disease, tau protein in frontotemporal dementia).

• Modifiable risk factors Vascular dementia—smoking; obesity; physical inactivity; excess alcohol; thyroid abnormalities; B vitamin deficiency.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Vascular dementia—smoking cessation, weight loss, sensible alcohol intake, physical activity; some evidence for remaining physically and mentally active.

2

• Secondary prevention No screening available.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Behavioural therapy; cognitive stimulation; drug treatment; occupational therapy; physical therapy.

Summary

Depression (excluding bipolar affective disorder) is a common condition that causes considerable morbidity, but little mortality. It is the world’s leading cause of years of life lost through disability (YLD) but simple lifestyle changes can help to prevent it. Many people do not seek healthcare, but talking therapies can be effective in mild disease.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence It is difficult to estimate incidence as many people do not seek healthcare.

• Prevalence Worldwide there were an estimated 151.2 million people with depression in 2004.

1 In the UK, it is estimated that 1 in 4 women and 1 in 10 men will have an episode of depression that requires treatment and up to 15% will have severe depression.

3 In England, there were 21 300 admissions to hospital with depression in 2008/09.

4

• Case fatality Depends on severity of disease but is generally very low. Depression is a risk factor for suicide; >90% of all suicides occur in people with mental illness.

3

• Mortality Worldwide there were 15 000 deaths from depression in 2004.

1 There were 124 deaths in England and Wales in 2008.

5

• Disability Worldwide depression was the 3

rd most common cause of disability, responsible for 65.5 million DALYs in 2004 when there were an estimated 98.7 million people with moderate or severe disability as a result of depression.

1 Depression is the leading cause of YLD in men and women in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

1

• Time Depression is predicted to become the leading cause of disability worldwide in 2030.

1

• Person Although depression is widespread, young adult women are disproportionately affected. It is more common in people with physical disease.

• Childhood and adolescence6 Prevalence: in prepubescent children 1% and in adolescence 3%, 2F:1M. Outcome: spontaneous recovery 10% at 3 months but 50% remain depressed at 1 year.

• Adult6 Lifetime prevalence: 67% for a depressive episode and 15% for severe depression. 2F:1M but suicide is more common among men. Outcome: on average an episode will last 6–8 months, chronic or persistent symptoms occur in 10%.

• Post-partum6 Prevalence: there is uncertainty around the prevalence of depression during pregnancy and child rearing. One study found that during pregnancy almost 1 in 5 women will have symptoms of depression, 10% will be affected during the first 2 postpartum months, increasing to over half of all women within the 1

st postpartum year.

• Elderly Common in elderly adults, partly due to life events, e.g. retirement with loss of routine, bereavement, or chronic illness. Many conditions can lead to depression, e.g. vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, malignancy, stroke. Depression should be excluded before dementia is diagnosed.

• Place A major cause of disability across the globe, but the leading cause of DALYs in high- and middle-income countries.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Sex (F > M); family history; genetic (e.g. 5-HTT gene); pregnancy; stressful event.

• Modifiable risk factors Alcohol; substance abuse; drug treatment (e.g. Beta-blockers)

Prevention

• Primary prevention Physical activity; sensible alcohol consumption; smoking cessation; refrain from illicit drugs.

• Secondary prevention Low index of suspicion in at risk groups can lead to early diagnosis.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT); drug treatment (antidepressant e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

6); suicide prevention.

References

2 Patient UK  http://www.patientuk.co.uk

http://www.patientuk.co.uk

Summary

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease characterized by hyperglycaemia caused by insufficient production of, or an inadequate response to, insulin. There are 2 main types of diabetes: Type 1, an autoimmune condition that presents mainly in childhood and Type 2, an acquired condition that presents mainly in adults. Obesity is a significant risk factor for Type 2 diabetes and as the prevalence of obesity rises, diabetes is becoming a major international public health concern.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence It is difficult to estimate incidence of type 2 diabetes as many cases are undiagnosed.

• Prevalence Worldwide, there were an estimated 220.5 million people with diabetes in 2004.

1 Over 90% of all diabetes is Type 2.

2 Gestational diabetes can occur in up to 14% of women during pregnancy.

3 In the UK there are estimated to be 2.8 million people with diabetes, but 35% of these are undiagnosed.

3 In the US in 2007 there were estimated to be 23.6 million people with diabetes of whom over 1 in 4 were undiagnosed.

4 In England, there were 60 000 admissions to hospital with diabetes in 2008/09.

5

• Case fatality Diabetes is underreported as a cause of death. Diabetes increases the risk of CVD. A person with diabetes is twice as likely to die as a person of the same age without the disease.

4

• Mortality Worldwide it was the 12

th commonest cause of death in 2004 when there were 1.1 million deaths.

1 There were 5541 deaths in England and Wales in 2008.

6

• Disability Worldwide, diabetes was responsible for 19.7 million DALYs in 2004.

1

• Time Diabetes is predicted to become the 10

th highest cause of disability worldwide in 2030

1 and it is predicted that diabetes deaths will double from 2005 to 2030.

2

• Person Type 1 usually presents in childhood or adolescence. Type 2 usually presents in adults.

• Place The majority of disability and deaths occur in middle- and low-income countries.

1 But it was the 6

th leading cause of disability in the Americas in 2004.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Type 1: genetic; family history; environmental. Type 2: age; family history; genetic; ethnicity.

• Modifiable risk factors Type 2: healthy diet; physical activity; weight management.

Prevention

• Primary prevention for Type 2 Healthy diet; physical activity; weight management. No prevention for Type 1.

• Secondary prevention

• General population Population-based screening for diabetes is not recommended.

7

• Patients with diagnosed diabetes Screening for retinopathy, foot problems, renal disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Weight loss; smoking cessation (to reduce risk of CVD); glucose control; BP control; lipid control; sensible alcohol consumption; patient education programmes.

The influenza pandemic of 2009 was a timely reminder of the potential risk from novel infectious agents. Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) pose challenges in terms of surveillance, control, and treatment. They can overwhelm public health systems and undermine previous health improvements. The increase in EIDs is thought to be related to a number of environmental, social, and scientific changes including:

• Changes in causative organisms, e.g. allowing the organism to cross the species barriers from animals to humans.

• Introduction into new populations due to changes in the environment (e.g. climate change) or population mixing (e.g. as a result of globalization with increased travel and interconnectedness of populations).

• Recognition of previously unknown infectious agents.

• Discoveries of infectious agents causing known diseases.

• Re-emergence of previously controlled infectious (e.g. due to development of antibiotic resistance, new environmental conditions, or failures of established control mechanisms).

Examples

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)

Caused by the SARS coronavirus, emerged in China in late 2002 and led to a series of outbreaks before being controlled in mid-2003. It caused respiratory disease and had a high case fatality. During the course of the epidemic there were 8098 reported cases with a high case fatality (almost 10%) leading to 774 deaths.

SARS was a test for the international public health community as it spread rapidly across different states in a short space of time. It demonstrated the potentially explosive mix of a new infection with rapid travel in a globalized world.

Unlike many respiratory infections, SARS is most infectious after the onset of symptoms. Therefore the strict quarantine imposed was effective in controlling the spread of the infection.

West Nile virus

Caused by a flavivirus and transmitted from mosquitoes. Until the 1990s it was mainly seen in Africa and Asia, but then started to occur as outbreaks in Europe and north America in humans, horses and birds. It can lead to fatal encephalitis. It is now an important health problem in the USA, with 3630 cases and 124 deaths in 2007.

Over the past four decades a number of new infectious diseases have been recognized (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 Emerging infectious agents1,2

| 1970s |

Ebola virus (Ebola haemorrhagic fever), Campylobacter jejuni, Cryptosporidium parvum, Hantaan virus, Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaires’ disease), Monkeypox virus, Parvovirus B19 (Erythema infectiousum) |

| 1980 |

Human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV1) |

| 1981 |

Toxin producing Staphylococcus aureus (Toxic shock syndrome) |

| 1982 |

Escherichia coli O157:H7, Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease), HTLV2 |

| 1983 |

HIV, Helicobacter pylori |

| 1985 |

Enterocytozoon bieneusi |

| 1986 |

Cyclospora cayatenensis, Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) (prion disease) |

| 1988 |

Hepatitis E virus, Human Herpesvirus 6 |

| 1989 |

Hepatitis C virus, Ehrlichia chafeensis, Photorhabdus asymbiotica |

| 1991 |

Guanarito virus (Venezuelan haemorrhagic fever) |

| 1992 |

Vibrio cholerae O139, Bartonella henselae (Cat scratch disease) |

| 1993 |

Sin Nombre virus (Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome) |

| 1994 |

Sabia virus (Sabia associated haemorrhagic fever), Hendra virus (Hendra virus disease) |

| 1995 |

Human Herpesvirus 8 (Kaposi’s sarcoma) |

| 1996 |

New variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (nvCJD), bat lyssaviruses |

| 1997 |

Avian Influenza virus in humans (H5N1) |

| 1999 |

West Nile virus (Nipah virus) found in USA |

| 2003 |

SARS coronavirus |

| 2004 |

Simian foamy retrovirus (zoonotic retrovirus found in humans) |

| 2005 |

HTLV4, HTLV5, human bocavirus |

| 2008 |

Plasmodium knowlesi (Malaria), Lujo virus (Viral haemorrhagic fever) |

| 2009 |

H1N1 influenza virus (Pandemic influenza) |

Summary

Acute gastroenteritis is a term used to describe diarrhoea and/or vomiting of short duration. Causes of acute gastroenteritis include a range of viruses, bacteria, and parasites, plus less commonly toxins or chemicals (Box 12.1).

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Commonest cause of illness worldwide with an estimated 4620 million cases in 2004.

1 In the UK gastroenteritis is one of the most common reasons for consulting in primary care, with about 1 in 30 people attending for this reason each year. Many more people will be affected and not present to their GP. In the USA each year there are an estimated 76 million cases of food-borne diseases, and 325 000 hospital admissions.

2

• Prevalence As a short-lived condition the point prevalence is generally low, but period prevalence is high, affecting between 1/3 and 1/5 of the population each year.

3

• Case fatality Low, but dependent on the causative agent, the vulnerability of the person, and the availability of re-hydration therapy.

• Mortality Globally 2.2 million deaths attributable to diarrhoeal disease in 2004.

1 It causes 17% of deaths in children <5 years, 45% of these are in Africa, 35% in South East Asia, and 20% in the rest of the world.

1 90% of deaths are in children <5 years mostly in developing countries. In the USA there are around 5000 deaths per year from food-borne diseases.

2

• Morbidity Diarrhoeal disease was the 2

nd leading cause of morbidity in 2004 with 72.8 million DALYs worldwide.

1

• Time Many causative agents are seasonal. Diarrhoeal disease is predicted to fall to the 23

rd leading cause of death worldwide by 2030.

1

• Person Anyone can be affected, but infants, the elderly and others who are unable to maintain hydration are most vulnerable to severe disease.

• Place Occurs everywhere, but the brunt of the morbidity and mortality is in developing countries, particularly those with poor sanitation.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (young and old); seasonal (dependent on organism).

• Modifiable risk factors Unsafe water (affects more than one billion people in the world); sanitation; hygiene; food preparation, storage, distribution and handling.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Improved water supply, sanitation and hygiene. WHO estimate that improved sanitation reduces diarrhoea morbidity by 32%, and hygiene education can reduce cases by up to 45%. Food safety in production, distribution and preparation are effective. Vaccines are available against some causative organisms.

• Secondary prevention Identification of outbreaks; follow-up cases; investigate potential sources.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Oral re-hydration therapy reduces mortality; antibiotic treatment for some.

Box 12.1 Causes of enteric infections (UK)

• Adenovirus.

• Astrovirus.

• Botulism.

• Calicivirus.

• Campylobacter spp.

• Cryptosporidium.

• Escherichia coli O157.

• Entamoeba histolytica.

• Giardia lamblia.

• Listeria monocytogenes.

• Norovirus.

• Rotavirus.

• Salmonella.

• Salmonella enteritidis.

• Salmonella typhimurium.

• Salmonella typhi, paratyphi A, and paratyphi.

• Shigella spp.

• Yersinia spp.

Healthcare associated infections (HCAIs) are infections acquired by patients (or staff) as a result of some healthcare contact (e.g. hospital admission) or other intervention (e.g. outpatient procedure).

Major HCAIs

The following can cause bacteraemia, chest infections, urinary tract infections, peripheral or central line infection etc.

• Escherichia coli.

• Staphylococcus aureus, including meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

• Acinetobacter baumannii.

• Glycopeptide-resistant enterococci (GRE).

• Norovirus and Clostridium difficile cause gastrointestinal infection.

Burden

HCAIs cause considerable morbidity and mortality. Estimates of the burden:

• European Union: 3 000 000 HCAIs and up to 50 000 deaths each year.

• UK: estimate 300 000 HCAIs per year, causing 5000 deaths and contributing to over 15 000 deaths per year.

• England: prevalence of HCAIs 8.2% in 2006.

• USA: 1.7 million infections and 99 000 associated deaths each year.

Risk factors for HCAIs

• Underlying illnesses in the patient that increase their susceptibility to infection (e.g. heart disease, critical illness, cancer, AIDS).

• Some treatments may increase susceptibility to infection (e.g. immunosuppressive therapy).

• Invasive procedures provide a portal of entry for organisms (e.g. surgery, intravenous therapy, catheterization).

• Use of antibiotics to treat infection may facilitate the growth of others (e.g. Candida, Clostridium difficile).

• Widespread use of antibiotics for infection or prophylaxis promotes antibiotic resistance.

• Proximity of patients and high-throughput facilities provide opportunities for transmission between patients.

• Needlestick injury.

Minimizing the risk of HCAI

• Handwashing/ decontamination between patients to prevent the transfer of micro-organisms.

• Use of protective clothing including gloves, aprons, and dress codes to reduce transmission on clothing.

• Appropriate systems to reduce the risk of transmitting infection during invasive procedures (e.g. sterilization, decontamination of equipment).

• Universal and specific precautions for patients with an infection (e.g. enteric or respiratory precautions).

• Correct use of antibiotics to minimise the risk of antibiotic resistant micro-organisms emerging and to reduce the risk of Clostridium difficile.

Further reading

Health Protection Agency. Surveillance of Healthcare Associated Infections Report: 2008. London: HPA; 2008.

Summary

In >95% of cases (primary) the cause of high BP and hypertension is not known although lifestyle factors are closely related to risk.1 Hypertension is defined by NICE as a persistent raised BP above 140/90mmHg (systolic/diastolic pressure).2 Hypertension can directly cause morbidity and mortality but its major contribution to ill health is as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke in particular. Hypertension is often clinically silent but prompt recognition and treatment can prevent serious consequences. This topic considers disease directly attributable to hypertension; primary and secondary hypertension and hypertensive renal and heart disease.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Difficult to measure as the condition is often clinically silent. Incidence rates of 3–18% have been reported depending on population studied.

3 Worldwide, 8.4 million pregnancies were affected by hypertension in 2004.

4

• Prevalence Worldwide it is estimated that there were almost 1 billion people with hypertension in 2000.

5 In the UK in 2006, 31% of men and 28% of women had hypertension.

6 There were 35 000 admissions to hospital in England in 2008 with hypertensive disease.

7

• Mortality Worldwide there were 1 million deaths from hypertensive heart disease in 2004, which was the 13

th most common cause of death

4 and there were a further 62 000 maternal deaths caused by hypertensive disease. There were 4473 deaths in England and Wales in 2008 from hypertensive disease.

8

• Disability Worldwide hypertensive heart disease was responsible for 8 million DALYs in 2004.

4

• Time The prevalence of hypertension is predicted to rise to >1.5 billion adults by 2025.

5

• Person Increases with age (30% of people aged 45–54 and 70% of people aged >70); More common in Black African and Black Caribbean ethnic groups.

1

• Place Hypertensive heart disease is a leading cause of death in middle-income countries where the majority of the burden of disability from this condition is also found.

4

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; family history; genetic; ethnicity.

• Modifiable risk factors Obesity; high salt intake; low potassium intake; excessive alcohol intake; physical inactivity; diabetes.

• Specific risk factors for secondary hypertension Dependent on cause.

Prevention for primary hypertension

• Primary prevention Maintain healthy weight; reduce salt intake; sensible alcohol intake; physical activity.

• Secondary prevention Maintain healthy weight; reduce salt intake; sensible alcohol intake; physical activity; drug treatment.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Dependent on clinical syndrome that results.

Summary

HIV is a human retrovirus that causes AIDS, a syndrome that was first recognized clinically in 1981. Two decades later it became the 4th leading cause of death in the world.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence In 2009, there were an estimated 2.6 million new cases of HIV globally

1 and 6630 new cases in the UK.

2 Incidence rate of 3.0 per 1000 in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK.

2

• Prevalence Globally 33.3 million people are living with HIV,

1 with population prevalence of up to 40% in some parts of sub-SaharanAfrica. In the UK it is estimated that 86 500 people were living with HIV in 2009.

2 The population prevalence is estimated at 0.45% in London, 0.08% in the rest of the UK.

• Case fatality Without treatment, the majority of people with HIV develop AIDS. Survival from AIDS diagnosis to death <1 year in resource-poor settings. In richer countries 80–90% of patients die within 3–5 years. With treatment the long-term prognosis is much better.

• Mortality Globally an estimated 1.8 million deaths in 2009, down from over 2 million in 2004.

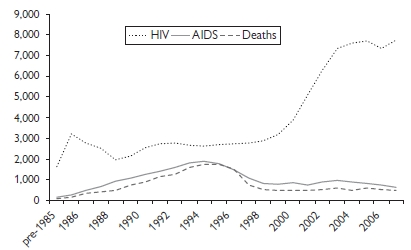

1 Declining in the UK: 1743 deaths in 1995 to 527 in 2009 (see

Fig. 12.3).

• Time Worldwide, incidence has fallen by 19% since the peak in 1999.

1 But HIV is increasing rapidly in many countries (e.g. India, China) while it has reached a plateau in some parts of Africa (e.g. Uganda). It is predicted to fall to the 10

th leading cause of worldwide deaths by 2030 with 1.2 million deaths per year.

3 In the UK incidence is increasing due to in-migration of infected people and increased acquisition in MSM.

• Person HIV affects sexually active people, recipients of unscreened blood products, injection drug users, and children (vertical transmission).

• Place A global disease but unevenly distributed. In 2004 it was the leading cause of adult mortality in Africa and >90% of child deaths caused by HIV/AIDS occurred in Africa.

3

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (women aged 15–24, men aged 25–34); geographical area.

• Modifiable risk factors Unprotected vaginal or anal sex; multiple sex partners; untreated sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (ulcerative, inflammatory); lack of circumcision (men); shared equipment for injecting drugs; occupational exposure (needlestick injuries); blood products (unscreened); breast feeding (infected mother).

Prevention

• Primary prevention School sex education; condom distribution and promotion of consistent use; effective STI diagnosis and treatment; targeted harm minimization for groups at increased risk; screening of pregnant women to prevent mother-to-child transmission through use of anti-retrovirals (ARV) and avoidance of breast feeding; safe blood/blood product supply through restrictions on donors and screening of blood; distribution of clean injecting equipment; drug treatment programmes; pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis for occupational and/or sexual exposure; poverty reduction programmes, education and employment, particularly for women.

• Secondary prevention Early detection of disease can prevent or delay progression to AIDS and can prevent onward transmission. Promotion of voluntary testing and counselling (VCT) for early detection of disease plus effective partner notification.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention ARV therapy substantially reduces morbidity and mortality. Treatment of infected individuals with ARVs also reduces transmission.

1

There were over 7000 new HIV infections every day in 2009

• 97% were in low- and middle-income countries.

• 1000 were in children <15 years of age.

• 6000 were in adults aged 15 years and older of whom:

• 51% were women.

• 41% were young people aged 15–24 years.

Summary

Influenza is caused by a virus which attacks mainly the upper-respiratory tract. The virus circulates worldwide and, due to ongoing mutation, varies from season to season. Infection with seasonal influenza confers some degree of immunity to infection by similar viruses which circulate during the following season, limiting the number of new infections. Influenza pandemics occur when new viruses emerge to which there is no pre-existing immunity in the global population. There were 3 pandemics in the 20th century, which resulted in millions of deaths and the most recent was in 2009.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Globally 3–5 million serious cases annually. Up to 30–200 per 100 000 persons per week in the UK, reported through visits to GPs for influenza-like-illness (ILI).

• Prevalence In England, there were 135 376 admissions to hospital with influenza in the year 2008/09.

1

• Subtype Most human influenza cases are caused by subtypes A and B, with subtype A causing serious cases more often. Of those influenza cases characterized in the UK in 2007, 60% were subtype A and 36% were subtype B. A small minority of cases are caused by subtype C.

• Mortality Globally 250 000–500 000 deaths per year. There were 78 deaths from influenza in England and Wales in 2009 with a further 26 741 deaths from pneumonia.

2 Millions of deaths were attributed to the 1918–19 pandemic, where the case fatality rate was much higher than for seasonal influenza.

• Transmission Person-to-person spread via droplets and particles excreted when infected individuals cough or sneeze.

• Time Influenza occurs throughout the year, but cases are concentrated over winter months in temperate areas.

• Person Incidence of disease is highest amongst infants, the elderly and the immunosuppressed.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Immunodeficiency, lung disease, diabetes, cancer, kidney or heart problems; age (infants and elderly); climate (season).

Prevention

• Primary prevention Respiratory hygiene: covering mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing and sneezing, proper disposal of used tissues and thorough hand washing. Vaccination: each year a vaccine is produced against the strain which is assessed by WHO to be the most likely major circulating virus in the following season. The efficacy of the vaccine depends on how closely matched the vaccine strain is to the seasonal strain that year. It is unlikely that a strain-specific vaccine will be available quickly enough in the event of pandemic. The seasonal vaccine is currently offered to at-risk groups in the UK. In 2007/08 there was 73.5% coverage of those aged 65 and over, and 45.3% coverage of younger at risk groups.

• Secondary prevention Prophylactic treatment of contacts of cases with antiviral drugs; exclusion from school/workplace while infectious.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Antiviral drugs for the treatment of symptomatic influenza are particularly effective if they are taken early in an infection (within two days of the onset of symptoms). Antibiotic treatment of secondary bacterial infections may be necessary for severe cases.

Further reading

HPA National Influenza Reports  http://hpa.org.uk

http://hpa.org.uk

WHO Influenza  http://www.who.int/topics/influenza/en

http://www.who.int/topics/influenza/en

Summary

Kidney cancer includes all cancers of the renal parenchyma, renal pelvis, and ureter. In the UK 90% of kidney cancers are renal cell cancers. Symptomatic patients typically present with haematuria, flank pain, abdominal mass, or systemic effects, e.g. weight loss, lethargy, or anaemia. Advances in diagnostic imaging have meant that it is increasingly diagnosed incidentally in patients undergoing scans (CT/MRI) for other indications.

Descriptive epidemiology (kidney and renal pelvis)

• Incidence Worldwide, there were 274 000 new cases in 2008.

9 In the UK it is the 8

th commonest cancer with 8228 new cases in 2007.

3

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 586 000 people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with kidney cancer within the previous 5 years.

1 In England, there were 13 000 admissions to hospital with kidney cancer in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In England and Wales, overall 5-year survival is approximately 50%, but this falls to 10% in people with metastatic disease at diagnosis (approximately 1 in 4 new cases).

2,3

• Mortality Worldwide there were 116 000 deaths from kidney cancer in 2008.

9 In the UK it is the 12

th commonest cause of cancer death.

3 There were 3059 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

5

• Time Incidence is increasing worldwide, in part due to better diagnostic techniques (e.g. CT and MRI).

3

• Person Predominantly occurs in adults, more common in men (possibly due to higher smoking prevalence).

2

• Place Occurs worldwide, but highest age-standardized incidence rates seen in high-income countries.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age; genetic (e.g. tuberous sclerosis, von Hippen–Lindau disease).

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking; acquired cystic renal disease;

3 obesity; occupational chemical exposure (e.g. cadmium in manufacture of dyes, plastics, fertilizer, soldering/welding,

7 and printing, rubber, and chemical industries

8); analgesic (phenacetin, now withdrawn).

Prevention

• Primary prevention Smoking cessation; weight loss; control occupational exposure to chemicals.

• Secondary prevention Screening using regular imaging (ultrasound, CT, or MRI) is offered to people with certain genetic conditions.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; biological therapy; arterial embolization; regular follow-up with ultrasound, CT or MRI for 5 years.

Summary

Leukaemia describes a range of conditions characterized by a malignant proliferation of white blood cells (Table 12.2). Leukaemias are classified as acute or chronic depending on how well-differentiated the malignant clone is and as lymphocytic or myleogenous depending on which cell type is affected.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, there were 375 000 new cases of leukaemia in 2004.

1 In the UK it is the 13

th commonest cancer with 7000 new cases in 2007.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 512 000 people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with leukaemia within the last 5 years.

3 In England, there were 92 100 admissions to hospital with leukaemia in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on type of leukaemia, age of patient (decreases with age) and stage at presentation. In England and Wales, 5-year survival has increased steadily since the 1970s and is now around 40% overall.

2

• Mortality Worldwide it is the 9

th commonest cause of cancer death in men and the 11

th commonest cause in women with 277 000 deaths in 2004.

1 There were 3990 deaths from leukaemia in England and Wales in 2009.

5

• Time Age-specific incidence rates have been stable in UK over the last 15 years and mortality has declined since the 1970s as treatment has improved.

2

• Person Slight male preponderance. In the UK, childhood incidence highest aged 0–4 years and adult rates increase from mid-40s to peak in people >85 years.

2 In high-income countries most deaths occur in people >60 while in middle and low-income countries most deaths occur in people aged 15–59 years.

1

• Place Occurs worldwide, lowest incidence seen in Africa and Eastern Mediterranean.

1

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (mainly ALL in children, CML 40–60 years, AML and CLL >60 years); family history; genetic.

• Modifiable risk factors Radiation; radon (see Lung cancer, p.

346)

7; smoking (see COPD, p.

314); benzene (used to manufacture chemicals

6).

Prevention

• Primary prevention Smoking cessation; control exposure to radiation and radon; control occupational exposure to benzene.

• Secondary prevention Screening is not used. Chronic leukaemia is often identified during routine blood tests.

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Chemotherapy; biological therapy; radiotherapy; bone marrow and stem cell transplants.

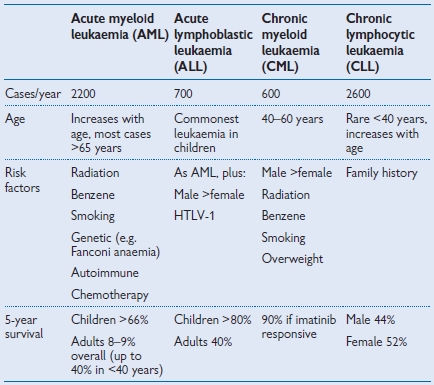

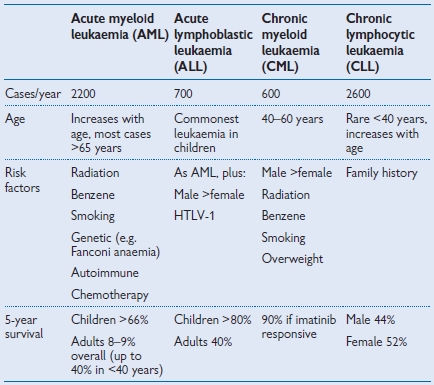

Table 12.2 Overview of leukaemias (UK)

Source: Data from Cancer Research UK

Summary

The liver is a common site for metastatic cancer deposits. In the UK primary liver cancers are 30× rarer than secondary tumours.1 Hepatocellular carcinoma is the commonest primary liver cancer. Most cases occur in Asia but their incidence is likely to increase worldwide.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence Worldwide, it is the 5

th commonest cancer with 632 000 new cases in 2004.

2 In the UK it is the 18

th most common cancer with approximately 3400 new cases in 2007.

3

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 386 000 people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with liver cancer within the previous 5 years.

4 In England, there were 7600 admissions to hospital with cancer of the liver or intrahepatic bile duct in 2008/09.

5

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In the UK 5-year survival is 5%.

3

• Mortality Worldwide, it is the 3

rd commonest cause of cancer death in men and the 6

th commonest cause in women with 610 000 deaths in 2004.

2 In the UK it is the 14

th commonest cause of cancer death. There were 3202 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

6

• Time Cases are likely to increase as prevalence of alcoholism, obesity related fatty liver disease and hepatitis B and C increase.

7 In the USA the incidence has increased by 80% in the last 20 years.

7

• Person It is rare before 50 years in the USA and Western Europe.

7

• Place Occurs worldwide; most cases occur in the Western Pacific region and it is the 2

nd commonest cause of cancer death in the African region.

2

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Family history;

3 genetic disorders that cause liver disease including alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and haemachromatosis;

3 diabetes (2–3× increased risk).

7

• Modifiable risk factors Underlying liver disease (cirrhosis) from any cause e.g. viral infections (e.g. hepatitis B and C); toxins (alcohol and aflatoxins, produced by

Aspergillius flavus contamination of nuts, cereals and dried fruit);

8 smoking and alcohol increase the risk of cancer in people with hepatitis B or C;

3 arsenic found in drinking water.

Prevention

• Primary prevention Reduce risk of infection with hepatitis B and C (hepatitis B vaccination; protected sexual intercourse; no needle sharing); sensible alcohol consumption; smoking cessation; reduce risk of aflatoxin in food chain.

8

• Secondary prevention AFP (alpha fetoprotein) is produced by some hepatocellular cancers. The British Society for Gastroenterology recommends that people who are at high risk of hepatocellular carcinoma are screened every 6 months with an abdominal ultrasound scan and serum AFP measurement.

9

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Surgery; transplant; chemotherapy; radiotherapy.

3

Summary

Over 90% of all lung cancer is caused by tobacco smoking. It is the commonest type of cancer in the world and is responsible for 1.3 million deaths a year. Lung cancer carries a poor prognosis as it often presents at an advanced stage with shortness of breath, cough, and weight loss.

Descriptive epidemiology (trachea, bronchus and lung)

• Incidence Worldwide it is the commonest cancer with 1.6 million new cases in 2008.

1 In the UK it is the 2

nd commonest cancer with 39 470 new cases in 2007.

2

• Prevalence Worldwide, an estimated 1.4 million people were alive in 2002 having been diagnosed with lung cancer within the previous 5 years.

3 In the UK there are an estimated 65 000 people alive who have ever been diagnosed with lung cancer.

2 In England, there were 83 600 admissions to hospital with lung cancer in 2008/09.

4

• Survival Depends on grade and stage at presentation. In England and Wales 5-year survival is 7%.

2

• Mortality Worldwide it is the commonest cause of cancer death in men and the 2

nd commonest cause in women.

5 It caused 1.3 million deaths worldwide in 2004 making it the 8

th commonest cause of death overall.

5 In the UK, it is the commonest cause of cancer death.

2 There were 30 018 deaths in England and Wales in 2009.

6

• Time Incidence reflects historical smoking patterns. In the UK new diagnoses have fallen dramatically in men since the 1970s and in women they stopped increasing in the 1990s.

2 Rates are still expected to rise in low- and middle-income countries.

• Person Rare before 40 years and more common in men (3M:2F).

2

• Place Current distribution reflects historical patterns of smoking. Occurs worldwide, but predominantly seen in middle and high-income countries with most cases occurring in Europe and the Western Pacific region.

5 Within the UK rates are higher in Northern England and Scotland and lower in the Midlands, South England, and Wales.

2

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (>80% of cases in over 60s);

2 family history.

• Modifiable risk factors Smoking causes 90% of cases;

2 environmental tobacco smoke; radon;

7 occupational chemical exposure (e.g. asbestos, polycyclic hydrocarbons, silica);

2 outdoor air pollution.

8

Prevention

• Primary prevention Tobacco control including: (a) reduce exposure to environmental tobacco smoke—smoking in enclosed public places and workplaces in England became illegal in 2007; (b) reduce number of smokers—in England the legal age for purchasing tobacco increased from 16 to 18 in 2007; (c) reduce tobacco advertising—in 2003 virtually all forms of tobacco advertising were banned in the UK; smoking cessation; maintain safe levels of indoor radon; control occupational chemical exposure.

• Secondary prevention Screening is not recommended. A Cochrane review has found that population based screening using sputum, chest X-ray or CT has little impact on treatment or mortality and repeated chest X-rays may actually cause harm.

9

• Treatment/tertiary prevention Small cell cancers: chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Non-small cell cancers: surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy.

Radon exposure7

Radon is a natural radioactive gas that is released from the uranium found naturally in rocks and soil. Found throughout UK but highest background levels from granite in Cornwall. Radon disperses in the open air but it can accumulate in enclosed spaces (including uranium mines and houses). The UK Government has set targets for indoor radon levels and it is possible to fit a radon sump to reduce indoor levels.

Summary

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by 5 species of protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium spread by the female Anopheles mosquito. The species of malaria differ in their geographic distribution and clinical severity.1 P. falciparum is most common in sub-Saharan Africa, Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands and causes most malaria deaths; P. vivax found mainly in Central and South America, North Africa, the Middle East, and the Indian subcontinent, causes less severe disease but can relapse; P. ovale is found almost exclusively in West Africa and can be asymptomatic; P. malariae occurs worldwide, although mainly in Africa and P. knowlesi has been recently documented in Borneo and Southeast Asia.2 The emergence of drug resistance to chloroquine has thwarted control and treatment programmes, but the advent of the use of insecticide treated bednets (ITBNs) and artemisinin-combined therapies (ACTs) appear to be showing some promise.

Descriptive epidemiology

• Incidence There were an estimated 2471.3 million new cases of malaria worldwide in 2004.

3 Most cases were caused by falciparum malaria (estimated at 88.4% in 2004

3). In the UK there were 1370 cases of malaria in 2008.

1

• Prevalence Difficult to measure, but half of the world’s population are reported to be at risk.

4

• Case fatality Despite effective therapy, about 1% of all cases of falciparum malaria die. In cases with WHO case definition severe malaria, between 30–50% die.

• Mortality It caused 889 000 deaths worldwide in 2004 making it the 14

th commonest cause of death overall.

3 It was responsible for 7% of deaths in children <5 years worldwide, increasing to 16% in the African region where 90% of all malaria deaths in children <5 years occured.

3 There were 6 deaths from malaria in the UK in 2008.

1

• Morbidity Worldwide malaria was the 12

th commonest cause of disability, responsible for 34 million DALYs in 2004.

3 But it was the 4

th commonest cause of disability in low-income countries.

• Time In the UK the number of cases and deaths have increased since the early 1970s reflecting trends in travel.

• Person People who live in or travel to malarial areas.

• Place Malaria predominantly occurs in Africa. 85% of all malaria cases were in the African region in 2004.

3

• Transmission Malaria is spread by the female Anopheles mosquito in areas where the temperature exceeds the 16 0C isotherm. Rare cases occur in temperate climates, for example ’airport malaria’ where infected mosquitoes are brought to the country aboard aircraft or where local summer temperatures increase allowing transmission in susceptible local mosquito vectors. Malaria cannot be transmitted directly from person to person, except in rare cases via blood and blood products.

Risk factors

• Fixed risk factors Age (young children); ethnicity (white and Asian have increased risk of severe malaria compared to black ethnicity);