At 4.45 a.m. on 1 September 1939, the pre-Dreadnought German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire against the small Polish military depot on Westerplatte in Danzig. Orderly Sergeant Józef Lopaniuk was on duty when he heard what he first assumed to be thunder but quickly recognised as artillery fire. After consulting his major, he sounded the alarm. Warrant Officer Władysław Baran recalled: ‘The air rocked. Fountains of sand, stones and smoke rose up. Shattered trunks and branches of trees, pieces of human bodies and weapons flew in the air. The deafening thunder of explosions was interrupted from time to time by the shrill screams of the dying.’1 Simultaneously the SS launched an attack on the Polish post-office workers in Danzig, who resisted strongly and declined a German appeal for their surrender. When the fighting forced them to take refuge in the basement of the post office, the Germans poured petrol into the building and set it alight. As the suffocating Poles emerged to surrender the SS shot them. The Daily Telegraph correspondent Clare Hollingworth happened to be in Katowice in Polish Upper Silesia when she saw the German forces advancing across the frontier and the Luftwaffe flying overhead.

I grabbed the telephone, reached the Telegraph correspondent in Warsaw and told him my news. I heard later that he rang straight through to the Polish Foreign Office, who had no word of the attack. The Telegraph was not only the first paper to hear that Poland was at war – it had, too, the odd privilege of informing the Polish Government itself.2

In London the Polish ambassador, Edward Raczyński, visited the foreign secretary, Lord Halifax, to beg for immediate help. General Ironside was informed of the German attack by Winston Churchill. When Ironside reached the War Office he discovered that they knew nothing about it. The CIGS, Lord Gort, did not believe the news but told the secretary of state for war, Leslie Hore-Belisha, who went to Downing Street to inform Chamberlain.3 In Poland ‘the outbreak of war was no surprise to anybody and many greeted it with jubilation, expecting a swift and easy victory. The nation was conditioned by propaganda, spread by the media, of German weakness and the strength of the Polish-French-British alliance.’4 The radio announcement of the outbreak of war was followed by the playing of the national anthem and Chopin’s Polonaise in A Major.5

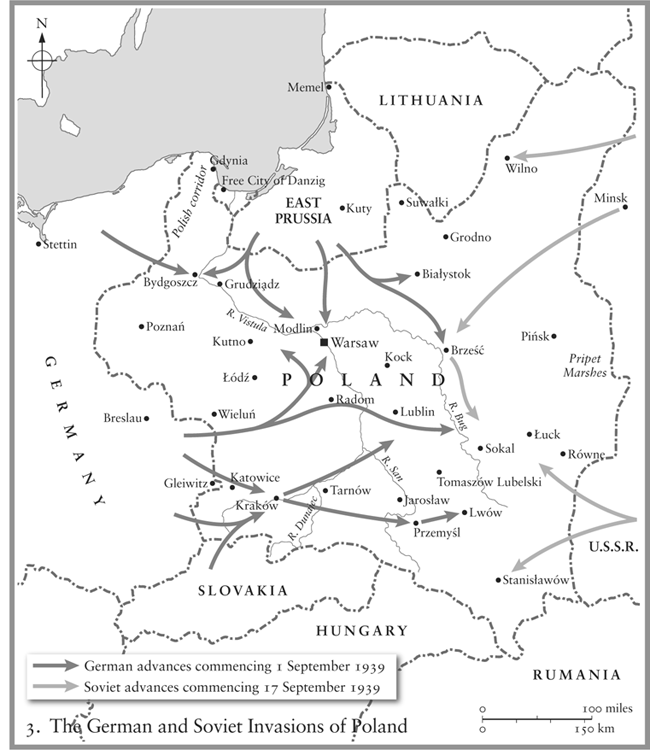

The German ground attack heralded a new form of warfare: Blitzkrieg, or lightning war. Rather than advancing along broad fronts as in previous wars, the Germans concentrated their forces into highly mobile armoured columns that smashed into Poland from three directions simultaneously. In the north-west, the German Army Group North, under General Fedor von Bock, was split into two forces. The Fourth Army under General Günther von Kluge launched an attack from German Pomerania with the aim of cutting the Corridor, thereby isolating Polish forces on the coast, and then joining the Third Army, under General Georg von Küchler, which was attacking from East Prussia, for a joint drive on Warsaw. The Polish Army Pomorze, under General Władysław Bortnowski, was not defending the Corridor in strength because it realised that this would be futile; instead, his troops were based on the Brda river. Army Modlin, commanded by General Emil Krukowicz-Przedrzymirski, fortified the Mława against the anticipated advance of the German Third Army. But the main weight of the German attack was further south. Army Group South, under General Gerd von Rundstedt, received the highest number of Panzers in any German formation. The Eighth Army under General Johannes Blaskowitz and the Tenth under General Walter von Reichenau launched their attack on the Łódź–Kraków triangle. This was defended by Army Łódź under General Juliusz Rómmel and Army Kraków under General Antoni Szylling. In the south-west, the Fourteenth Army under General Wilhelm List attacked Army Kraków.6

The second new aspect of Blitzkrieg was the ruthless application of air power by the Luftwaffe. Civilians had been bombed during the Spanish Civil War, notably at Guernica, but on nothing like the scale inflicted by the Germans in Poland. Wieluń, a farming town 60 miles east of Breslau, had the dubious honour of becoming the first town in Poland to be flattened by German bombs. The hospital, school, churches and shops were all bombed and over 1,600 people, 10 per cent of the town’s population, were killed on the first day of the war. Polish armoured trains, effective against the Panzers, proved of limited utility as the Luftwaffe destroyed the railways.7 Everywhere towns were bombed, refugee columns strafed, passenger trains bombed and their fleeing passengers machine-gunned. Nothing seemed to escape the force of the Luftwaffe. General Carton de Wiart wrote later: ‘And with the first deliberate bombing of civilians, I saw the very face of war change – bereft of romance, its glory shorn, no longer the soldier setting forth into battle, but the women and children buried under it.’8 The strength of the Luftwaffe awed the Poles: one child observed, ‘You couldn’t even see the sky. I just couldn’t believe how they had built so many planes.’ Civilians were strafed from the air on the road. A Polish report stated that: ‘Along the Warsaw-Kutno road during the entire month of September, mounds of decomposing cadavers were to be seen, consisting for the most part of women and children.’9 Ryszard Zolski, working in an ambulance unit, witnessed hospitals, ambulances and ambulance trains being bombed despite being marked prominently with a red cross.10 The Germans might have attempted to justify the bombing of towns ahead of their advance on military grounds but this does not explain why towns well to the east of the Vistula were bombed early on. For example, Stanisławów (Ivano-Frankivsk), in the far south-east of Poland, was first bombed on 8 September and then subjected to ten more raids in the following week. Stanisław Kochański had a lucky escape. Watching the bombing raids from the attic of his family’s house through binoculars, he was forcibly dragged out of the attic by his father just before bombs fell around the house, shattering windows, dislodging roof tiles and leaving shell fragments lodged in the walls.11 On 10 September, Warsaw became the first European capital to be subjected to bombing raids: there were twelve on that day alone.

Concentrated too near the frontier, Polish defences were quickly overwhelmed in many areas, and General Heinz Guderian was delighted by the speed with which his Panzers crossed the Corridor. The Brda river defences were bypassed by German armour, leaving the road open for a rapid drive southwards. Army Modlin did, however, succeed in slowing the advance of the Third Army at the Mława, forcing the Panzers to wait for their infantry to catch up before renewing the attack. In the south, where Polish planners had hoped to make a stand to defend Poland’s industrial region, Polish defences were overwhelmed by the combination of German armour and air power.12 Jan Karski was a lieutenant in the Mounted Artillery Division stationed at Oświęcim on 1 September when the Luftwaffe bombed their camp and then the Panzers advanced and fired at the ruins: ‘The extent of the death, destruction and disorganisation this combined fire caused in three short hours was incredible. By the time our wits were sufficiently collected even to survey the situation, it was apparent that we were in no position to offer any serious resistance.’ Karski and his colleagues in Army Kraków began to retreat, a phenomenon that was becoming familiar to most of the Polish Army.13

The Poles did not, however, retreat without a fight. A fierce battle took place in the village of Mokra, north of Częstochowa, on the line dividing Army Kraków and Army Łódź. During this battle the Volhynian Cavalry Brigade charged at German infantry and successfully scattered them before the Germans massacred the cavalry with their machine guns and artillery. Further north, the Polish 18th Uhlan Regiment of the Pomorze Cavalry Brigade was ordered to attack the flank of the German 20th Motorised Division in order to cover the retreat of the Polish infantry. The Uhlans’ adjutant, Captain Godlewski, queried the order to charge and was told by his commanding officer, Colonel Kazimierz Mastalerz, ‘Young man, I’m quite aware what it is like to carry out an impossible order.’ With sabres drawn, the 250 men charged at the German infantry, who fled. At this point a column of armoured cars and tanks came upon the scene and fired at the cavalry, killing half of them in minutes. This is the incident that gave rise to the German propaganda, much repeated since, that Polish cavalry had charged at German tanks.14

On 2 September, Army Pomorze was still withdrawing from the Corridor under intense German pressure. It attempted to mount a defence on the Ossa river near the city of Grudziądz, but at this critical juncture Polish commanders made a significant error. For no apparent reason the Poles decided to swap the positions of the two divisions defending the main road. In the resultant chaos, as troops became entangled and communications broke down, the commander of the Polish 16th Division, Colonel Stanisław Świtalski, panicked and ordered a retreat to the south-west. Although he was promptly sacked, the Poles did not recover in time to mount a firm defence of Grudziądz. The Luftwaffe bombarded the Polish troops and once the planes had finished their work and the smoke cleared:

In front of us appeared a blood-chilling sight. Bodies were strewn across the road, and the horses who were killed were still in harness … In a nearby field lay the scattered remains of equipment and vehicles … The trenches were full of slain soldiers … There were so few soldiers left alive that in reality the 34th and 55th Infantry Regiments had ceased to exist as individual units.15

The Polish defences on the Mława were eventually bypassed by the Germans and by late afternoon Army Modlin began to retreat to the line of the Vistula. Further south, the situation was even more serious, as the Germans had succeeded in forcing a breach between Army Kraków and Army Łódź, forcing both armies to retreat. Karski wrote that by the end of that day, ‘we are now no longer an army, a detachment, or a battery, but individuals wandering collectively towards some wholly indefinite goal’. In fact Army Kraków did recover in time to mount a significant defence line before Kraków and prevent the German attacks from forcing a breach between Army Kraków and Army Karpaty under General Kazimierz Fabrycy to its east. On the central front, Army Poznań, under General Tadeusz Kutrzeba, had still not come into the battle but was forced to retreat towards Kutno because of the retreat of neighbouring Army Łódź and Army Pomorze.16

Sunday 3 September is remembered in Britain as the day she declared war on Germany: when at 11 a.m. the ponderous tones of Chamberlain were heard on the radio announcing the start of the hostilities. Later that day in Parliament the deputy leader of the Labour Party, Arthur Greenwood, spoke: ‘Poland we greet as a comrade whom we shall not desert. To her we say, “Our hearts are with you, and, with our hearts, all our power, until the angel of peace returns to our midst”.’17 In Paris the Polish ambassador, Juliusz Łukasiewicz, struggled to get the French to honour their alliance obligations. The French Government prevaricated, stating that it needed to recall the Chamber of Deputies before a decision could be taken, and then waiting for Italy either to respond to an appeal for neutrality or to intervene diplomatically to stop the German war against Poland. Łukasiewicz recorded that during those first three days in September: ‘Our ally France took a definitely defensive stand and was much more concerned with its relations with Rome than with the needs of our war situation, which already demanded immediate air action in the west.’18 At last, on the afternoon of 3 September, France declared war on Germany. In Warsaw crowds had been watching the British and French embassies ever since the German attack. Finally the news they had been waiting for came: ‘This announcement was followed by the playing of the three national anthems, British, French and Polish. It was received by everybody with enthusiasm. In a few minutes all the streets were decorated by flags of the three nations.’ The British ambassador, Sir Howard Kennard, and the military attaché Colonel Edward Sword were greeted by loud cheers when they appeared on the balcony of the British embassy.19 The Chicago Tribune correspondent William Shirer was in Berlin and noted of the crowd: ‘They listened attentively to the announcement. When it was finished, there was not a murmur. They just stood there. Stunned.’20 Ribbentrop had convinced Hitler that Britain would not declare war over Poland. His belief was shared by many Germans who had not expected that a local war against Poland would become a world war.

The Poles urgently needed not just British hearts but British and French power, because by the end of the first week Polish forces were being pushed back on all fronts. Army Modlin was withdrawing to the fortress city of Modlin and Army Pomorze was moving southwards towards Warsaw. The most critical sector was the breach between Army Łódź and Army Kraków near Piotrków. The Polish reserve, Army Prusy, under General Stefan Dąb-Biernacki, was still being mobilised when the high command decided that the situation at Piotrków justified the risk of putting the under-strength reserve into action, and on 5 September, it encountered the German 1st Panzer Division and lost the battle for Piotrków. A notable feature of this battle was that this was the first major encounter between Polish and German armoured units. The Polish 2nd Light Tank Battalion destroyed 17 German tanks, 2 self-propelled guns and 14 armoured cars with the loss of only 2 tanks. Despite this Polish commanders had little idea of how to use armour and any fleeting opportunity to exploit this success was lost. On the evening of 5 September, the commander-in-chief Marshal Rydz-Śmigły ordered Army Kraków, Army Prusy, Army Poznań and Army Łódź to begin withdrawing to defensive positions behind the Vistula and Dunajec rivers, thereby abandoning western Poland. Army Poznań and Army Łódź were then ordered to join with a part of Army Modlin to form a new Army Lublin under General Tadeusz Piskor to defend the northern approaches to Warsaw. Army Kraków and Army Karpaty were ordered to form a new Army Małopolska under General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, which first attempted to defend the Dunajec river but soon began withdrawing further east to the San river.21 These retreats were in accordance with the Polish defence plan: a withdrawal to the major rivers. But the Polish military planners could not have taken the weather into account, and General Carton de Wiart had noted on the eve of the war: ‘The country west of the Vistula was terrain admirably suited to tanks at any time, but now, after a long, long spell of drought, even rivers were no longer obstacles, and I did not see how the Poles could possibly stand up to the Germans in country so favourable to the attacker.’22 A Polish colonel reflected on how even the rivers of central Poland proved to be no barrier to German armour: ‘The rivers were all dried up; the San was a trickling rivulet which artillery and caterpillars could ford where they wished.’23

The situation at the end of the first week was critical and action was urgently needed in the west in order to reduce the pressure on Poland. Throughout the September campaign, the Polish Government and high command misled the population into believing that the British and French were engaging the Germans in the west. It was inconceivable to the Poles that their two powerful allies would do nothing active to assist Poland in her hour of need. British and French inactivity equally amazed the Germans, and ample evidence emerged at the 1946 Nuremberg trials of the weakness of the German army in the west in 1939. General Alfred Jodl told the tribunal: ‘If we did not collapse already in 1939 that was due only to the fact that during the Polish campaign the approximately 110 French and British divisions in the west were completely inactive against the 23 German divisions.’ General Wilhelm Keitel revealed: ‘We soldiers had always expected an attack by France during the Polish campaign, and were very surprised that nothing happened … A French attack would have encountered only a German military screen, not a real defence.’ The Germans believed that by using their 2,300 tanks when all German tanks were in the east, the French could have easily crossed the Rhine and entered the Ruhr, which would have caused the Germans great difficulties.24 The French did make a brief incursion into Germany, crossing into the Saar at three points on 7 September. Łukasiewicz was, however, alarmed to hear: ‘It was clear that the war had not yet started there. In an attempt to avert or postpone it, the German troops had not only not initiated any aggressive action but had not returned the fire of the French artillery; rather they had hung signs over their trenches stating that they did not wish to fight France.’25 The French were only too keen to take the Germans at their word and withdrew from the Saar. The Nazi propaganda minister, Jozef Goebbels, wrote in his diary: ‘The French withdrawal is more than astonishing; it is completely incomprehensible.’26

The simple fact was that neither the British nor the French government nor their military chiefs had any will to prosecute a war with Germany at this stage. Indeed, it is possible to sum up allied policy as moving from a reluctance to take any action in support of Poland that might lead to German retaliation against them, to one of deluding themselves that there was nothing they could do in any case because their armed forces were not ready for war, to the final justification that there was no point in taking any action because Poland was being so rapidly overrun. For example, the British blamed the French for not using their powerful army and air force to aid Poland, whereas the French responded by emphasising Britain’s general lack of preparedness for war. By 8 September, the argument was being used that the situation in Poland was so desperate that there was no point in bombing Germany or launching a ground offensive. At the first meeting of the Anglo-French Supreme War Council on 13 September, Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier congratulated themselves on not having undertaken operations against Germany. Chamberlain stressed: ‘there was no hurry as time was on our side’. Halifax explained to Raczyński that Britain was planning for a three-year war and nothing would be gained by taking premature offensive action. Ironside regretted allied inactivity, recording in his diary on 29 September 1939: ‘Militarily we should have gone all out against the Germans the minute he invaded Poland … We did not … We thought completely defensively and of ourselves. We had to subordinate our strategy to that of the French … We missed a great opportunity.’27

Neither Britain nor France wanted to be the first country to bomb Germany, fearing immediate German retaliation on their cities and civilians, yet that bombing was what the Poles wanted most of all. On 5 September, Raczyński received an appeal from Warsaw: ‘The Polish Air Force appeals to the Command of the Royal Air Force for immediate action by British bombers against German aerodromes and industrial areas within the range of the Royal Air Force, in order to relieve the situation in Poland.’28 The British response was for the air ministry to write a memorandum for the British ambassador in Poland, Kennard, who was embarrassed by RAF inactivity:

Since the immutable aim of the Allies is the ultimate defeat of Germany, without which the fate of Poland is permanently sealed, it would obviously be militarily unsound and to the disadvantage of all, including Poland, to undertake at any moment operations unlikely at that time to achieve effective results, merely for the sake of a gesture. When the opportunity offers, we shall strike with all our force, with the object of defeating Germany and thus restoring Polish freedom.29

Instead the RAF bombed the German fleet at Wilhemshaven and Brunsbüttel and dropped propaganda leaflets over Germany. The British Government thought that this would demoralise the German population. Arguments were put forward against the bombing of German industry on the grounds that it was in private ownership. General Gamelin explained French inaction on the grounds: ‘the French air force could not undertake the bombing of German military objectives without the participation of the British, who had the overwhelming majority of Allied bombing power at their disposal’.30

There were other ways in which Britain and France could assist Poland: namely, through the supply of armaments and financial aid. General Mieczysław Norwid-Neugebauer arrived in London on 8 September with a shopping list of armaments urgently needed by the Polish Army. Primarily the list comprised fighters and bombers but also included an assortment of infantry weapons, ammunition and transport. These requests were backed by the support of a member of the British military mission in Poland, Captain Davis, but the British were not prepared to give Poland any of their meagre supplies of war materiel. Norwid-Neugebauer only obtained 15,000 Hotchkiss guns and 15–20,000,000 rounds of ammunition – in any case the supplies would not arrive for six months. Supplies already purchased by Poland from Britain and France before the war now failed to arrive because the Rumanians would not allow the French ship to unload her cargo in Constanţa. Financial aid was, however, more forthcoming. Loans were made to Poland to purchase armaments from the Soviet Union: the British loan was £5,000,000 and the French 6,000,000 francs. On 6 September the Cabinet learnt of an agreement whereby ‘a large deposit of gold at present held by the Bank of England on the Bank of International Settlements’ account will in future be held by the Bank of England for the account of a Polish bank in Warsaw’. This was aimed at depriving the Germans of the opportunity to seize Polish gold in the same way that they had seized Czech gold deposits in March. The Polish Government did, in fact, succeed in smuggling 325,000,000 złoty in gold from the Polish bank into Rumania when it crossed into that country. This was then transported to France and, when France was attacked, to French North Africa, where it became trapped and unavailable to the Poles until the Allies seized the region from the Vichy French forces in 1942.31

Poland was left to fight alone. By the end of the first week the Poles could only attempt to slow the German advance, but could not stop it. Everywhere the Polish retreat was hampered by the flight of civilians eastwards clogging up the roads. Fela Wiernikówna was in Łódź and watched the refugees from the western border region flee: ‘Cars, women with children in pushchairs and in their arms, men with bundles. Among them the peasants drove their cattle. The voices of the cows and goats mingled with the tears of the children.’32 A hospital administrator Zygmunt Klukowski struggled to move his military hospital nearer to the Rumanian border because of the refugees: ‘This whole mass of people, seized with panic, were going ahead, without knowing where or why, and without any knowledge of where the exodus would end.’33 Others decided to stay at home because: ‘There is no front and no rear area, the danger is everywhere, nowhere to go, because what is here is everywhere.’34

The German advance was greatly facilitated by the conduct of the ethnic Germans in Poland, the Volksdeutsche. As Clare Hollingworth put it, ‘Invasion is simplified when one has such good friends in the country invaded.’35 Many of these ethnic Germans were armed and had secretly received military training in Germany before the war. Polish soldiers and civilians were appalled by the disloyalty demonstrated by their German neighbours. A document recovered from a downed German plane revealed that this disloyalty was deliberately encouraged by the Germans, who hoped that Volksdeutsche reservists in the Polish Army would refuse to go to their stations on mobilisation and that those that did would desert at the first opportunity and join the German forces. Ethnic Germans were also encouraged to assist by conducting guerrilla warfare in the Polish rear. They would make themselves known to the German troops ‘by means of signs of recognition and passwords’.36 The German policy was successful: Private Wilhelm Prüller noted in his diary on 17 September: ‘two Polish soldiers of German Volksdeutsche ancestry are fighting with us; they came to us voluntarily and are the best of Kameraden’.37

The Polish authorities were aware that the ethnic Germans might prove disloyal in the event of war and had prepared lists of suspect Germans before the war. As soon as the German armies crossed the frontier, 10–15,000 ethnic Germans were arrested and force marched towards Kutno. On the way they were attacked by Poles and it has been estimated that around 2,000 were killed. The invading Germans also knew whom they wanted to arrest: prior to the war the Nazis had drawn up a Sondersfahndungsbuch, Wanted Persons’ List, of those Poles who had been identified by the Volksdeutsche as likely to oppose the imposition of Nazi rule. Heading this were the intelligentsia and government officials, but also included were Polish participants in the interwar uprisings in Silesia. The policy of German terror began on 4 September in Katowice, when the German security police murdered 250 Poles. Jews were also targeted, particularly in Będzin, Katowice and Sosnowiec. Feelings ran especially high in Bydgoszcz (German: Bromberg) where there was a large ethnic German population, who began shooting at Polish soldiers and even attacked a Polish priest. On the afternoon of 3 September, the Polish Army marched out of Bydgoszcz amid cries from the Polish population: ‘Don’t abandon us, because the Germans will murder us all here!’ The local Polish defence unit turned on the Germans and killed between 700 and 1,000 ethnic Germans. When the Wehrmacht entered the city it was quick to take revenge. Between 6 and 13 September, 5,000 Poles were killed in the neighbourhood of Bydgoszcz and 1,200 in the city alone.38

On 7 September the great battle on the Westerplatte finally came to an end. The Polish military depot, with fewer than 200 defenders, had been persistently bombarded from the sea and bombed by the Luftwaffe. After two days the commander of the Westerplatte, Major Henryk Sucharski, lost his mind and ordered a surrender. He was strapped to his bunk by his mutinying soldiers and the defence was continued by his deputy, Captain Franciszek Dobrowski.39 The German bombardment caused enormous damage as ‘enemy artillery fire literally ploughed the land’. One defender wrote: ‘The barracks are unrecognisable after all the damage. In the cellar, soldiers lie along the walls, overly tired, the wounded on stretchers. The only light comes from a candle. Hygiene is beneath contempt, the air is awful.’ Then on 7 September, a German shell hit the ammunition store and the order was issued: ‘If anyone is still alive out there, go and surrender.’ Bernard Rygielski recalled:

The German commander asked about the size of the group. He did not want to believe that we were just so few, he had thought that there were 2000 of us. Then he called out: Attention!, saluted, and then spoke to us. After reassuring us that we were safe, he recalled Verdun, and told his soldiers that we should be seen as an example of how a few men could hold off an opponent. He handed back Major Henryk Sucharski his sword.40

The German soldiers showed their respect for the defenders, standing to attention and saluting them as they marched into captivity. The Germans lost over 300 men in the fighting for the Westerplatte whereas the Poles lost 15. By 19 September, the situation in Danzig was sufficiently secure for Adolf Hitler to visit the city, now reabsorbed into the Reich. The German population greeted him with jubilation.

Army Łódź fought hard around the city of its name; Army Prusy fought valiantly near Radom, and Army Kraków managed to escape across the Vistula despite the Germans having crossed the river at Szczucin ahead of them. In the north, Special Operational Group Narew under General Czesław Młot-Fijałkowski attempted to resist German attacks across the Narew and at the same time form a new defence line on the river Bug in eastern Poland. Guderian noticed the weakness of Polish forces in north-eastern Poland and obtained permission to switch his advance south-eastwards to conquer eastern Poland instead of joining the general movement on Warsaw. The advance of his Panzer units led to the fall of Wizna, opening the road to Brześć and the rest of eastern Poland, which was still largely undefended.41

At this critical juncture the Polish high command failed its army. On 7 September, Rydz-Śmigły moved the high command from Warsaw to Brześć. Communications had not been fully prepared there and effective control over the armies was all but lost just when the new defence lines were under preparation. Sometimes field commanders received one set of orders from Warsaw, where the chief of staff, General Wacław Stachiewicz, had remained, and another from Brześć – neither of which necessarily accurately reflected the situation in the front line. General Stanisław Sosabowski’s memoirs ably attest to the chaos caused by conflicting and misleading orders and the eventual breakdown in communications. Rydz-Śmigły’s flight had been preceded by the exodus of the government and administration from Warsaw on 4 September, and the departure of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the diplomatic corps on 5 September for Nałęczów and Kazimierz, near Lublin. At each stage German radio based in Breslau broadcast the new location of the diplomats. On 7 September, the government began its eastward trek, first to Łuck, then to Krzemieniec, before reaching the Rumanian frontier at the town of Kuty on 14 September.42

Just as Rydz-Śmigły was abandoning Warsaw for Brześć, an opportunity arose for a Polish counteroffensive by Army Poznań. Led by the most imaginative of the Polish commanders, General Tadeusz Kutrzeba, this attack aimed to disrupt the left flank of the German advance on Warsaw and retake Łęczyca and Piątek, relieve the pressure on Army Łódź, and allow time for the defences of Warsaw to be strengthened. The Bzura valley north of Łódź was the strongest Polish position remaining – the Poles had a threefold advantage in infantry and a twofold advantage in artillery – and there were no German Panzers in the area. The initial attack on 9 September met with some success and on 10 September, the Germans were in retreat having lost 1,500 men taken prisoner of war by the Poles from the 30th Infantry Division alone. Captain Christian Kinder of the German 26th Infantry Regiment noticed that his troops ‘were shaken by the superior power of the enemy, [and] were beginning to be resigned to defeat’. The German response was immediate and the 1st and 4th Panzer Divisions were diverted westwards from the outskirts of Warsaw to assist the German counterattack. Most of the Tenth Army was brought into the battle as well as 800 tanks and 300 bombers.43

Kutrzeba had been too optimistic in launching his attack. His Order of the Day for 11 September read: ‘The enemy is in retreat. He is withdrawing from the Warsaw area and is encircled by us. In his rear our fellow countrymen form rebellious groups. Revolt throughout the Poznań region. Forward to total victory!’ Stirring words indeed: but they did not reflect the truth. While Kutrzeba had 9 infantry divisions and 2 cavalry brigades, totalling 150,000 men, they were not in a condition to fight. Discipline had broken down in many units as a result of the constant retreat, and other units were exhausted. For example, the 26th Infantry Division had just fought hard for four days west of Bydgoszcz. Kutrzeba’s plan also depended on Army Łódź being able to tie down the Germans while the Bzura offensive took place, but this army was a broken one and could not contribute to the battle. By the night of 12 September, it was clear that the offensive had failed and that the German lines had been bent in some places but broken nowhere. Kutrzeba admitted defeat: ‘We were encircled, and the noose around our necks would tighten day by day, if Warsaw did not come to our aid.’ Far from aiding the retreat of Army Pomorze to Warsaw, Kutrzeba now needed its aid to extract his forces from the Bzura front.44

The only hope left to the Polish troops was to retreat towards Warsaw through a narrow twelve-mile wide gap between the Vistula and the main road to Warsaw. This area was covered by the forest of Kampinos, dense woods interspersed with bogs, marshes and the tributaries of two rivers. According to Kutrzeba, the forest became the ‘grave of the Army of Poznań’. The Germans dropped 328,000 kg of bombs on the Bzura front and Kampinos forest on 17 September alone. These ferocious air attacks broke the Polish armies. A German officer, Captain Johann Graf von Kielmann, noted their effects: ‘The captured Poles are driven half-insane by fear and throw themselves on the ground – even in captivity – whenever there’s the sound of an aircraft engine from somewhere.’ German artillery pounded the forest relentlessly.45

Lieutenant-Colonel Klemens Rudnicki, commanding the 9th Lancers, witnessed Polish units wandering the forest desperately seeking an escape. The Poles were short of food, ammunition and arms – and above all lacked maps of the region. Consequently, Captain Z. Szacherski of the 7th Mounted Light Infantry recorded:

There were dead Germans everywhere, on the road and in the ruined buildings. I gave my men orders to go through the Germans’ map and trouser pockets in the faint hope of finding the maps which we needed so desperately. At last our search was rewarded: we found a map of the Brochów-Sochaczew area in the pocket of a dead NCO. For us, it was the most valuable booty of the entire war.

He then planned the escape of his troops from the forest. They had to cross a 1¼-mile stretch of open, flat ground to reach the cover of the next village and the Germans had the road covered by artillery:

I drew my sabre and gave the command: ‘Squadron follow on at the gallop!’ And to the accompaniment of the low thunder of the guns, we raced off like the wind. I glanced to my left. In the distance I could see the steep far bank of the Vistula, dominating the entire region; it was from there that the German artillery was firing. We had put about 200m[etres] behind us when the Germans intercepted the road with their firing, sending up a formidable barrage in front of the village of Czeczotki as we approached.

I looked over my shoulder: the 17th Regiment was spread out as if on a parade ground, keeping its regulation distances in exemplary fashion. Close behind me at the head of the column were the regimental colours; ahead of me, a formidable screen of fire – a booming, moving wall of sand, dust, flames and iron. The regiment was steadily drawing nearer to this thunderous barrier. Though the horses were tired, the pitch of nervous tension induced the weaker beasts to keep up the tempo and the entire cavalcade careered directly at the screen of fire. We were nearly in their range – another 200 metres, another 150, and already scraps of shrapnel were whistling round our heads, with sand spurting into our eyes at every explosion. Then, suddenly, all was quiet. At the very same moment that we stared death right in the face, the Germans had ceased firing. Confused and disconcerted, we disappeared into the village and the cover of the trees.46

No reason has been discovered why the German artillery stopped firing at that moment. Szacherski and Rudnicki were among the soldiers who escaped the German noose and reached the temporary sanctuary of Warsaw: on 17 September so did Kutrzeba and his staff. The Germans captured 180,000 Polish troops and a huge amount of Polish materiel. At least 17,000 Poles had died in the battle, and German losses were also heavy with 8,000 dead and 4,000 captured.47

The first German Panzers had reached the outskirts of Warsaw on 8 September. The defence of the outskirts was being organised by the Warsaw Defence Command under General Walerian Czuma. The energetic mayor, Stefan Starzyński, roused the population of the city to help, sending all fit men out to dig anti-tank ditches. Over 150,000 people responded, both men and women, of all ages and all religious denominations. Makeshift barricades were constructed from overturned trams, removal vans and furniture, and they stopped the advance of the 35th Panzer Regiment in the suburbs of Ochota and Rakowiec. The next German attack was made by the 4th Panzer Division with assistance from the infantry. A German soldier later wrote: ‘Terrible fire descended upon us. They fired from the roofs, threw burning oil lamps, even burning beds down onto the panzers. Within a short time everything was in flames.’ Units from the German Third Army attacked through Praga, the eastern suburb of Warsaw, on 15 September but were heavily defeated. The Germans withdrew to try again later with reinforcements.48

The Polish defence plan Zachód had envisaged an organised Polish retreat to eastern Poland, where the forces would regroup and launch a counteroffensive when the western allies had attacked in the west. The retreat lacked organisation. This was partly due to constant pressure from the German ground and air forces, but partly also due to the collapse of the Polish communications network, which meant that the high command had little idea of what was going on at the front. The new Army Group South, to be made up of Army Kraków and Army Małopolska and commanded by General Kazimierz Sosnkowski, was ordered to go to the defence of Lwów, but the two armies were prevented from joining forces by the German 2nd Panzer and 4th Light Division. On 18 September, Army Kraków launched a counterattack at Tomaszów Lubelski but by 20 September was overwhelmed and forced to surrender. Other forces attempted to reach Lwów, which had been under siege by the German 1st Mountain Division since the 12th. The forest of Janów, twelve miles north of Lwów, became the main battleground. The Polish corps chronicler wrote:

The forest as a refuge and escape, the forest as a trap and ambush, the forest of darkness and thicket, as guardian angel and defender, the upturned tree trunks as our enemies, which creep around, move around, leap out, which are front and back, in a word the forest is the ally of the defenders.49

The Volksdeutsche and local Ukrainian-Polish citizens assisted the Germans by revealing some of the Polish positions, thereby ensuring that the German artillery would be accurate. Polish casualties were very high from artillery fire, and when the infantry and Panzers attacked the surrounded Poles, the Polish soldiers were ordered to break out of the forest in small units and to seek refuge in Lwów.

On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland. This had serious implications for the defence of Lwów from the Germans, which had been entrusted to General Władysław Langner, who had 4 battalions and 12 artillery guns. On 18 September, a German plane dropped a canister into the city which contained a Polish flag and a letter from the German command:

The Germans expressed their admiration of the valour of the defence, emphasised the fact that further resistance would be impossible, declared that soldierly honour had been satisfied, and proposed that the city should be surrendered, promising to leave the officers their arms.50

The Poles declined the offer and the battle continued. On 20 September, the Germans were ordered to cease firing on Lwów because the Red Army was entering the city. Under the erroneous impression that the Soviets were allies, Langner’s chief of staff, Colonel Kazimierz Ryziński, met the Soviet commander, Colonel Ivanov, and surrendered Lwów to the Red Army. Similar confusion existed in the fortress of Brześć. Just as the Poles were about to surrender to the Germans, Guderian was informed that the Red Army was about to advance. The German withdrawal was so rapid ‘that we could not even move all our wounded or recover our damaged tanks’. On 22 September, Guderian met the Soviet Colonel Semyon Krivoshein to hand over the city. This was an important moment for both Germany and the Soviet Union. The last time representatives of the two countries had met in Brześć was to sign the humiliating Treaty of Brest-Litovsk which took Russia out of the First World War in 1917. Now the meeting was to be the first step in the Fourth Partition of Poland.51

Poland’s multi-ethnicity provided the Soviet Union with its excuse to invade eastern Poland. In the early hours of the morning of 17 September, Poland’s ambassador in Moscow, Wacław Grzybowski, was handed a note by the Soviet foreign minister, Molotov, which he refused to accept. The note, which was then copied to all the ambassadors in Moscow, attempted to justify the actions of the Soviet Union:

The Polish Government has disintegrated and no longer shows any sign of life. This means that the Polish state and its Government have, in point of fact, ceased to exist … Left to her own devices and bereft of leadership Poland has become a suitable field for all manner of hazards and surprises which may constitute a threat to the USSR. For these reasons the Soviet Government, which has hitherto been neutral, cannot any longer preserve a neutral attitude towards these facts.

The Soviet Government also cannot view with indifference the fact that kindred Ukrainian and Belorussian people, who live on Polish territory and who are at the mercy of fate, should be left defenceless.52

This was exactly the same argument the Russians had used in 1795 to justify the Third Partition of Poland.53

The Soviet invasion delighted the Germans. As early as 3 September, the German foreign minister, von Ribbentrop, had sent a telegram to the German ambassador in Moscow, Count Friedrich Werner von Schulenburg, asking him to warn Molotov that Germany ‘would naturally, however, for military reasons, have to continue to take action against such Polish forces as are at that time located in Polish territory belonging to the Russian sphere of influence’. On 10 September, Molotov replied to Schulenburg that the Soviet Union would soon invade eastern Poland on the pretext of offering protection to the Ukrainians and Belorussians living there. The Soviet Union was anxious not to appear as an aggressor.54 It was not clear about the terms of the British and French alliance with Poland, and did not want to run the risk of becoming embroiled in a war with those two countries. Indeed, the Soviets even attempted to persuade the Polish Government, then sheltering in Kuty on the Polish-Romanian frontier, to invite the Soviets into Poland as a protecting power. The Soviet ambassador to Poland, Nikolai Sharonov, approached the American ambassador, Drexel Biddle, asking him to talk to the Polish foreign minister, Beck, on the subject. Biddle told the Russian ambassador to talk to Beck directly, which he did, and Beck refused even to consider such a request.55

Jock Colville, assistant private secretary to Neville Chamberlain, wrote in his diary on 17 September: ‘the announcement by which the Soviet Government attempted to justify their act of unparalleled greed and immorality is without doubt the most revolting document that modern history has produced’.56 In London Raczyński pressed the British Government to lodge a protest in Moscow at the Soviet action, but it reminded him that a secret protocol to the Anglo-Polish treaty of 25 August 1939 stipulated that it applied only to Germany, and that consequently there was no obligation on Britain to declare war on the Soviet Union. The British ambassador in Moscow, Sir William Seeds, was consulted and replied, ‘I do not myself see what advantage war with the Soviet Union would be to us, though it would please me personally to declare it on Mr Molotov.’57 Instead, Chamberlain made a statement in the House of Commons: ‘His Majesty’s Government has learned with indignation and horror of the action taken by the Government of the USSR in invading Polish territory’, but added that the action was not unexpected.58 The Soviet occupation of eastern Poland immediately became a politically controversial issue. On 24 September, an article by Lloyd George appeared in the Sunday Express, entitled ‘What is Stalin up to?’, which justified the invasion on the grounds that the Soviet Union was only occupying territory in which the ethnic Poles constituted a minority. Raczyński sent a letter to The Times countering Lloyd George’s arguments: The Times declined to publish it so Raczyński had 300 copies printed privately and distributed to prominent politicians and journalists.59 On 26 October, Halifax went even further when he informed the House of Lords:

It is perhaps, as a matter of historical interest, worth recalling that the action of the Soviet Government has been to advance the boundary to what was substantially the boundary recommended at the time of the Versailles Conference by the noble Marquess who used to lead the House, Lord Curzon, who was then Foreign Secretary.60

This statement led to a protest from Raczyński. Britain simply had neither the means nor the will to attack the Soviet Union. The British Government, only a few days into the war, already recognised the fact that would prove enormously damaging to the Polish cause: Britain needed the power of the Soviet Union to defeat Germany and was convinced that the German-Soviet alliance was only a temporary measure.

On 17 September, the Polish president, Ignacy Mościcki, and the senior members of his government crossed into Rumania. As soon as they had reached their sanctuary, the commander of the Polish Army, Rydz-Śmigły, and his staff followed. His deputy chief of staff, Colonel Józef Jaklicz, was impressed ‘by how calm and composed he was, despite having taken the difficult decision to abandon Poland’.61 Others were far less favourably impressed. Carton de Wiart noted: ‘Śmigły-Rydz will never be forgiven by the vast majority of Poles for his decision to desert his Army, and although I know that he was not the right man to be in command of the Polish forces, it had never occurred to me that he would throw aside his responsibilities in a hysterical rush to save his own skin.’62 The outrage was caused by the fact that the Poles were still fighting the Germans and Warsaw had not yet fallen. There was also the question of how to react to the Soviet invasion since no orders had been given. On 20 September, Rydz-Śmigły made a final broadcast to the Polish armed forces in which he stressed that the bulk of the Polish Army was engaged in fighting the Germans and that ‘in this situation it is my duty to avoid pointless bloodshed by fighting the Bolsheviks’.63 The Soviets had not been invited into Poland but now it was a case of ‘to save what can be saved’, and the plan was to withdraw as many troops as possible to Rumania and Hungary from where they should make their way to France and form a new Polish army.64

Deprived of guidance from their high command, the Polish troops did not know how to react to the Soviet invasion. It was an invasion in force: two Soviet fronts, the Belorussian Front under the command of General Vasily Kuznetsov and the Ukrainian Front under the command of General Semen Timoshenko, crossed the frontier with 24 infantry divisions, 15 cavalry divisions, 2 tank corps and several tank brigades, and advanced towards the line pre-agreed with the Germans. The appearance of the Red Army cavalry appalled the Poles: ‘Instead of saddles they covered horses with blankets. Horses would fall under the riders, exhausted from tiredness. They were so thin that it was fearsome to look at them.’65 The Soviet soldiers were hungry and approached local villages begging for food. The Poles had no idea whether the Red Army were aggressors or had crossed the frontier as allies against the Germans. Indeed, it appears that many Soviet soldiers were also unclear.66

The Polish frontier was lightly held by units of the KOP, whose commander, General Wilhelm Orlik-Rückemann,* received no orders from the high command or the government, but decided to fight: ‘The security guards and the KOP … at first defended themselves doggedly. Bolshevik forces advanced incessantly. At the watchtowers of Mołotków and Brzezina the Bolsheviks used machine guns in a hard fought battle.’67 Near Juryszany in the province of Wilno, a KOP cavalry patrol encountered a large group of Soviet cavalry and made a brief charge before heading for the cover of the nearby woods. In Grodno (Hrodna) a makeshift local defence force was hastily put together from the remnants of troops retreating from Wilno and included a number of boy scouts. It defeated the first Soviet attack on 20 September: the army used its remaining weapons against the advancing tanks, while the boy scouts darted between the tanks throwing Molotov cocktails. Ten Soviet tanks were destroyed that day before the local defence force was overwhelmed on the 21st.68 Twelve more Soviet tanks were destroyed by the 101st Reserve Cavalry at Kodziowce near the Lithuanian border. A two-day battle was fought in the triangle formed by the villages of Borowicze (Borovychi), Hruziatyń (Gruziatyn) and Nawów, and the Soviets lost over 200 men before forcing the Poles to surrender. In all, Molotov reported to the Supreme Soviet on 31 October that the Red Army had lost 737 men killed and 1,862 wounded. Polish losses are unknown.69

Most Polish troops heeded the orders of Rydz-Śmigły and fled for the relative safety of Rumania, Hungary and Lithuania. Others, however, had no choice but to surrender to the Soviets. In Lwów some junior officers gathered under the windows of the room where the staff were awaiting the Soviet representatives and shouted: ‘Shame on those who sold Poland to the Bolsheviks! Treason!’ Some soldiers took the opportunity of the wait before the formal surrender to render their weapons useless and dispose of emblems of rank. This last action proved important because the first question the Soviet soldiers asked was, ‘Who are the officers?’ The Poles did not betray them and, unknown to all the soldiers then, this instinct to conceal rank would save many lives. When the Pińsk river flotilla surrendered to the Soviets, the officers were marched away from their men. Shots were heard and the men learnt that their officers had been killed by the Soviets despite having surrendered in good faith.70

Molotov’s note of 17 September had also contained the statement that ‘Warsaw as the capital of Poland no longer exists’, but this was premature. After the rebuff in the suburbs of Warsaw on 8 September, German plans for the defeat of Warsaw changed. Surrounded by Panzers and infantry divisions, the city was now to be bombarded and bombed into submission before the ground troops would advance. The Germans amassed over 1,000 artillery pieces and 13 infantry divisions for the battle. Rydz-Śmigły had entrusted the overall defence to General Rómmel, ordering him to hold Warsaw ‘as long as there is sufficient ammunition and food’. The aim was to buy time for Poland until her allies launched an offensive in the west. Rómmel called upon the population to be steadfast by deliberately lying to them when he stated that the Germans were already withdrawing from Poland to fight in the west. He refused to meet the German delegate who wanted to discuss the unconditional surrender of Warsaw. The Germans made their position clear: ‘Refusing the German offer of surrender merely means unnecessary bloodshed from which the population cannot be spared as Warsaw will be treated as a fortress.’ On Hitler’s direct orders Warsaw was to be starved into submission. Polish requests to evacuate the civilian population were refused but on 22 September there was an hour-long ceasefire to allow around 1,000 foreign nationals time to escape.71

From 22 September, Warsaw was subjected to an endless artillery bombardment and run of bombing attacks. The pianist Władysław Szpilman recalled:

The corpses of people and horses killed by shrapnel lay about the streets, whole areas of the city were in flames, and now that the municipal waterworks had been damaged by artillery and bombs no attempts could be made to extinguish the fires. Playing in the studio was dangerous too. The German artillery was shelling all the most important places in the city, and as soon as a broadcaster began announcing a programme German batteries opened fire on the broadcasting centre.72

The mayor, Stefan Starzyński, made a final broadcast just before the power station was put out of action, in which he praised the resoluteness of the population of Warsaw: ‘And as I speak to you now, through the window I see, enveloped by clouds of smoke, reddened by flames, a wonderful, indestructible, great, fighting Warsaw in all its glory.’ He finished by calling for revenge on Berlin. Many civilians did not hear his broadcast, as they were sheltering in basements: ‘We do not know what is happening outside, we do not even know what is happening across the street.’ On 25 September, the Germans escalated the number of bombing raids on the city centre, bombing until thick clouds of smoke concealed the targets, and at the peak 200 fires raged unchecked. A doctor, Ludwik Hirszfeld, thought that the scene must look like the end of the world. About 40,000 civilians were killed during the German artillery and air bombardment of the city.73

Not only was Warsaw being flattened by artillery and bombs and on fire but the population was now beginning to starve. At the beginning of the war the mayor had urged citizens not to hoard food and they had obeyed him. Now, at the end of September, there was little food left and the number of people to be fed had increased dramatically with the reinforcement of the Warsaw garrison. Troops rushing to the aid of Warsaw were appalled by the sight of the city. General Sosabowski described the state of the capital:

I had seen death and destruction in many forms, but never had I seen such mass destruction, which had hit everyone, regardless of innocence or guilt. Gone were the proud buildings of churches, museums and art galleries; statues of famous men who had fought for our freedom lay smashed to pieces at the bases of their plinths, or stood decapitated and shell-scarred. The parks, created for their natural beauty and for the happy sounds of laughing, playing children, were empty and torn, the lawns dotted with the bare mounds of hurried graves. Trees, tossed into the air with the violence of explosion, lay with exposed roots, as if they had been plucked by a giant hand and negligently thrown aside.

Almost the only noise on this morning was the rumble of bricks as walls, weakened by bombs, finally subsided. The smoke of burning houses pillared into a windless sky and the smell of putrefaction lingered in the nostrils.74

On the morning of 27 September, acting on Rómmel’s orders, General Kutrzeba surrendered Warsaw and the Germans entered the following day. The shock to the soldiers who had wanted to continue fighting was tremendous:

We listened silently to these grim words; there were no questions or comments. Our minds recognised the inevitability of capitulation, but our feelings could not be reconciled to it. Was this to be the end? It was as though one had had a heavy blow on the head and was overcome by some mental paralysis.75

On 30 September, 140,000 Polish troops marched out of Warsaw into captivity: ‘The few civilians we passed gazed woodenly at us, without praise or condemnation.’ The Polish defenders were treated with respect by the Wehrmacht. General Kutrzeba and his chief of staff, Colonel Aleksander Pragłowski, were besieged by a pack of photographers wanting to record the fall of Warsaw for German propaganda. They were then sent to POW camps for the rest of the war. Starzyński had a less happy fate: he was arrested by the Gestapo and imprisoned in several different locations. His ultimate fate is unclear but it is generally accepted that he was shot at Dachau concentration camp.76

Eighteen miles north-west of Warsaw the fortress of Modlin was still holding out. It had been a fortress since Napoleonic times, comprised of a citadel surrounded by ten forts, and had been improved by the subsequent Russian occupiers and again by the Poles, who had added strong anti-aircraft defences. The Germans recognised the seriousness of the task ahead of them and by late September had gathered 4 infantry divisions and a Panzer division to attack the city. On the night of 27–28 September, the Germans sent a Polish major through their lines to inform the defenders, under the command of Brigadier Wiktor Thommée, that Warsaw had surrendered. On the following day, a white flag was seen flying above the citadel but the forts continued to resist German attacks. Two forts had fallen by the time Thommée surrendered on 29 September. The Germans captured nearly 24,000 Poles.77

The German campaign in Poland was not yet over and there was still fighting on the Baltic coast. Danzig had been captured and the port of Gdynia fell on 14 September. Polish defences were now concentrated on the Hela peninsula, a narrow spit of land, 20 miles long and a few hundred yards wide, stretching into the bay of Danzig. It was defended by about 2,000 men under the command of the head of the Polish admiralty, Vice-Admiral Józef Unrug. The Hela peninsula was remorselessly bombarded from the sea by the Schleswig-Holstein and Schlesein and bombed by the Luftwaffe, but German infantry had to attack to force its surrender on 1 October.78

General Franciszek Kleeberg provided the final act. He commanded Special Operational Group Polesie, and by incorporating into it the remnants of Special Operational Group Narew and various other units, he had at least 17,000 men under his command. They fought a series of actions against the Red Army near Milanów, inflicting over 100 casualties on the Red Army. Kleeberg then turned his attention towards the Germans. Realising that his ad-hoc force had little chance of reaching the capital, he planned to raid the main Polish Army arsenal near Dęblin and seize enough weapons and ammunition to wage guerrilla warfare. At Kock, however, his force ran into the German 14th Corps, and after fierce fighting and high casualties, Kleeberg and around 16,000 soldiers surrendered on 6 October.79 The Polish campaign was now over.

Poland’s losses in the September campaign were high: 66,300 soldiers and airmen were killed and 133,700 were wounded; 694,000 soldiers were captured by the Germans and 240,000 by the Soviets. Unlike the Soviet Union, Germany was a signatory to the Geneva Convention governing the treatment of prisoners of war, but there were numerous instances of Polish POWs being shot by the Wehrmacht during the campaign, the worst atrocity being the execution of 300 men near Radom. Two main temporary camps were established at Rawa Mazowiecka and Sojki, where the Poles were forced to sleep in the open air and received no medical attention. The Wehrmacht attempted to shift blame for the atrocities on to the SS and Gestapo. For example, the surrendering Polish officers at Modlin had been promised parole after their surrender but found themselves in captivity. When General Thommée protested to a German general he received a disingenuous reply: ‘Herr General is wrong: the German Generals gave you their word as soldiers and have kept it; you and the entire gallant garrison of Modlin were released, and if you were then arrested by the police and detained by the police as prisoners, you must understand that the police and politics are above the army.’80 This conversation took place in Colditz, a camp run by the Wehrmacht. Only around 85,000 Polish soldiers and airmen managed to escape to neighbouring countries. Equipment losses were almost total. The notable exception was the 10th Cavalry Armoured Brigade, mobilised too late to take much part in the campaign, which crossed into Hungary with its tanks. One hundred aircraft were flown to Rumania, where the pilots were interned. The German losses were far lower: 10,572 men killed, 30,322 wounded and 3,409 missing.81

The Polish Air Force was too small and too outdated to prevent German air superiority. Contrary to German reports it was not wiped out on the ground on the first day of the war, for it had already been dispersed to its secondary airfields scattered throughout Poland, and all that the Germans hit were training and sporting aircraft. Indeed the only Polish military aircraft destroyed by the Luftwaffe on the ground were 17 Karaś bombers on 14–15 September at the Hutniki airfield. Given the obsolescence of the Polish fighters, they did surprisingly well against the Luftwaffe. At 7 a.m. on 1 September, Lieutenant Władysław Gnyś shot down 2 Dornier 17 Bombers, the first Polish Air Force kills of the war. During the first week, Polish fighters accounted for 105 German planes, the majority having been shot down by the units defending Warsaw.82 One Polish pilot later described the air war in Poland:

The superior manoeuvrability of our machines was obvious. We beat them hollow whenever they appeared even in overwhelming numbers to accept a combat. But in pursuit – we had to bite our fingers. They were miles ahead in speed and firepower. Their bursts of two cannon and four machine guns sounded like thunder in June. Our machines could only bark pitifully with their two machine guns.83

The ability was there, the will was there, but the technology was lacking. Polish losses were exceptionally high and by 6 September the air force had lost 50 per cent of their planes. The high command then ordered the survivors to fly east beyond the Vistula. This was a disastrous decision because preparations had not been made to receive them and there were no spare parts and little fuel. German air attacks on the roads meant that the ground crews struggled to make their way eastwards. On 17 September, the Polish Air Force shot down a Dornier bomber and a Soviet fighter and then obeyed orders to fly to Rumania. There they hoped to find the French and British planes promised to them. The Rumanians, however, had forbidden the French ship to unload the Morane fighters at Constanţa, and a British ship carrying Fairey Battle bombers turned for home at Gibraltar.84

Both types of Polish bombers, Karaś and Łoś, were too poorly armoured to be able to fly safely at low levels to bomb German formations accurately. They did, however, do their best and met with some success. During the critical battle in the Piotrków sector in the first week, they repeatedly bombed the German forces, and on 4 September, the Germans reported that Polish bombs had destroyed or badly damaged 28 per cent of the 4th Armoured Division. Out of a total bomber force of 154 the Poles lost 38 planes.85

The Polish Navy had little impact on the September campaign. The destroyers Wicher and Gryf laid mines off the Hela peninsula and on 3 September exchanged fire with the German destroyers Lebrecht Maas and Wolfgang Zenker, damaging the latter and forcing both to be withdrawn. The Luftwaffe then sank both Polish destroyers and 3 minesweepers. The submarines had no impact because the Germans sent few merchant ships into Polish waters. The lack of fuel and supplies forced the submarines to leave Poland. The Ryś, Zbik and Sep reached Sweden, where they were interned; the Wilk sailed directly to Britain. The Orzeł had been interned in Estonia, disarmed and put under guard, but the crew managed to overcome the guard and sail for Britain without any charts or navigation equipment; it was hunted by both the German and Soviet navies but managed to escape the Baltic. The submarines then joined the Royal Navy and were stationed at Dundee. Arrangements had been made for 3 Polish destroyers, Grom, Błyskawica and Burza, to sail to Britain on the outbreak of war; they left Poland on 31 August and joined the Royal Navy at Rosyth.86

A commission was established by the Polish Government-in-Exile in France to investigate the reasons behind Poland’s defeat. Prominent members of the opposition were quick to blame the Sanacja Government. General Władysław Sikorski had fallen out with the ruling military clique and at the outbreak of war had been living on his estate in semi-retirement. He had offered his services, which were declined. In France he orchestrated a witch-hunt against those who had overlooked him. The first stage of this assessment was drawn to a close by the German attack on France in May 1940. In June 1940, after fighting for little longer than the Poles, the French Army surrendered and 1,900,000 soldiers were made prisoners of war. This total was nearly twice the size of the Polish Army in the September campaign.87 The French and British air forces were vastly more modern than the Polish, yet one analysis of the French campaign has argued that an approximate calculation of enemy losses per day of campaigning per allied plane demonstrates that the Poles had fought considerably more effectively in September 1939 than the Allies did in May–June 1940.88 Equally, during the first month of the Barbarossa campaign in June 1941, the German Army conquered Soviet territory far exceeding the size of Poland. It was clear that the lessons of the Polish campaign had not been learned by those countries liable to be attacked by Germany. Yet two extremely detailed and able reports by western observers had been produced, by the American ambassador, Drexel Biddle, and by the head of the British military mission, Carton de Wiart, but both were ignored.89 Indeed, Peter Wilkinson, a member of the British mission, later said: ‘Really the terrifying thing was that the very able despatch of De Wiart … describing the lessons from the Polish campaign was pigeon-holed entirely by the War Office.’90 In February 1940, Sikorski had given a lecture to the French leaders on ‘The Most Important Experiences and Conclusions of the 1939 Campaign’. He also met Gamelin and Weygand on several occasions and urged the French Army to form strong armoured formations. His advice was ignored.91

The first lesson was that valour was not enough against a well-armed enemy. There was no doubt about the bravery of the Polish soldiers. Germans recalled seeing how the Poles would man an anti-tank gun firing at the Panzers and as each man was killed, another would take his place until all were dead. One German soldier wrote:

Before any attack the Poles give three cheers – each one a long drawn out cry that sounds like animals baying for blood. Although they are absolutely suicidal in the face of our fast-firing machine guns I must admit that to stand and watch as those long lines of infantry come storming forward is quite unnerving.92

General Albert Kesselring, commanding Luftwaffe operations in Poland, wrote later: ‘It is a tribute both to the Polish High Command and to our own achievement that the Polish forces had enormous fighting spirit and in spite of the disorganisation of control and communications were able to strike effectively at our points of main effort.’93 General Ernst von Kab stated:

The Polish soldier was tough and fought fiercely, yet at the same time had modest needs and demanded little in the way of supplies. These virtues were typical of Polish soldiers wherever we encountered them … whether they were a group of survivors holding out for days on end without food and ammunition in great forests or swamps … or surrounded Polish cavalry detachments often breaking through with reckless courage, or even simple infantrymen who dug themselves in before some village, defended their position until each of them in turn was killed in his rifleman’s pit, and stopped fighting only when life ended.94

When the Polish infantry had parity with or superiority over the German infantry, they did inflict high casualties on the Wehrmacht. Carton de Wiart reported to London: ‘the German of 1939 is not the German of 1914’. The Germans themselves concluded that their infantry had not performed as well as expected and needed further training.95

The Polish campaign also highlighted major weaknesses in the structure of command which the Poles had copied from the French Army. There was a unanimous belief that the Polish high command, particularly Rydz-Śmigły and his chief of staff, General Stachiewicz, had failed the country. The system of command was over-centralised and Rydz-Śmigły was in direct command of 7 armies and 1 independent operational group, and at the same time he was expected to formulate new defence plans. This burden was obviously too much for one man. Rydz-Śmigły’s departure from Warsaw hit morale badly, and it was also a disastrous decision, for at Brześć he lacked the communication structure essential to maintain control over the Polish war effort, and increasingly the orders he issued bore little resemblance to the situation on the ground. Other Polish commanders were also criticised. Stachiewicz managed to escape from internment in Rumania and finally reached London in 1943, but he was not made welcome there by the Polish armed forces and was given no further employment. Fabrycy reached the Middle East but was only given a minor role in the Polish division formed there. Dąb-Biernacki was condemned for having abandoned his army to surrender without him and was not employed again. Commanders of smaller Polish units or those commanding armies towards the end of the campaign, such as Sosnkowski and General Wincenty Kowalski, fared better and were employed in the newly formed Polish Army in France. The majority of Polish generals spent the remainder of the war as POWs in Germany, and 10 became POWs of the Soviets.

Foreign commentators focused on the Germans’ use of their Panzers. Ironside wrote in his diary: ‘Gamelin said that the chief lesson to be learnt from the Polish campaign was the penetrative power of the speedy, and hard-hitting German armoured formations and the close co-operation of their Air Force.’96 Gamelin failed to notice an important aspect to the German use of armour: the Panzers could advance through thick forests, so their progress on 1 September through the Tuchola forest in Pomerania foreshadowed their advance through the Ardennes. The Germans learnt their own lessons from the campaign. For all of the impact that the Panzers had made on the Polish forces, they too showed alarming weaknesses. Twenty-five per cent of the Mark I and Mark II tanks were destroyed in Poland along with 40 per cent of the Mark IIIs and 30 per cent of the much vaunted Mark IVs.97 Breakdowns were the most common cause of loss but the Polish anti-tank guns, the best weapon in the Polish armoury, had also played an important role. It was clear to the German high command that improvements in equipment and training were essential before mounting an offensive against the better-armed western allies.

It was widely recognised that the September campaign proved that cavalry had no place in modern warfare. Rudnicki has analysed the performance of the Polish cavalry and concluded that the main problems were that horses could not travel as fast as armoured columns, and were particularly vulnerable to bombing and shellfire. When in combat, the fighting strength of the troop was reduced by the number of men needed to hold the horses.98 Polish cavalry charges against tanks are the most enduring myth of the Polish campaign, and as has been shown above the German propaganda campaign against the Poles exploited one incident when Polish cavalry, having scattered the German infantry, accidentally encountered German tanks. Occasionally, out of the desperate need to break out of an encirclement such as in the Kampinos forest, individual cavalrymen did charge individual tanks: ‘The idea was to ride to the tank, hop on it, lift the flap and throw a hand grenade in. This was sometimes successful, but inevitably suicidal.’99

What is less well known is that the German Army also used cavalry in the September campaign. The German First Cavalry Brigade, with a strength of 6,200 men and 4,200 horses, operated on the eastern flank of the Third Army advancing into Poland from East Prussia. Towards the end of the campaign the Nowogródzka Cavalry Brigade was attacking the German 8th Infantry Division when it was in turn attacked by German cavalrymen:

Drawn sabres flashed over the heads of the German cavalrymen as the bulk of their force veered ponderously down from the high ground with growing momentum. Clearly the Germans, with their heavy warhorses, were simply aiming to run down their enemies in a headlong downhill gallop. But the Poles saw a chance in the manoeuvrability of their lighter mounts.100

The battle was fought mostly with sabres. The German cavalry then retreated uphill and were pursued by the Poles into the forest, where the German infantry opened fire on them with machine guns.

Arguably the most significant contribution to the swift German victory was the ruthless application of German air power, which drew no distinction between military and civilian targets. There was, however, a noticeable reluctance in Britain and France to believe the reports from Poland about the deliberate targeting of civilians by the Luftwaffe. On the first day of the war Kraków, Łódź, Gdynia, Brześć and Grodno were among the first cities in Poland to be bombed. The British and French governments urged the Polish Government not to retaliate against targets in Germany so as not to ‘provoke’ Hitler. Even after the German high command openly announced on 13 September its intention ‘to bomb and shell open towns, villages and hamlets in Poland, in order to crush resistance by the civilian population’, the British Government was not prepared to believe this. The Daily Telegraph correspondent Clare Hollingworth was bombed and machine-gunned as she fled eastwards and was horrified to discover on her return to Britain that the BBC had not broadcast her reports of the deliberate targeting of civilians. It was only when Kennard and Biddle, having reached Rumania, reported ‘the bombardment of the entirely undefended village [Krzemieniec] in which the foreign missions accredited to Poland were at the time accommodated’ that Polish accounts were believed.101 The bombing of Warsaw foreshadowed the Blitz. First the waterworks were deliberately targeted, putting the pumps out of action, before incendiary bombs were dropped on the city.

When the Polish president, Ignacy Mościcki, and the government officials crossed the frontier into Rumania on 17 September, they had done so with the verbal assurances of the Rumanian Government that they would be given assistance to reach the Rumanian port of Constanţa. The French ambassador to Poland, Leon Noël, had informed the Poles that France would grant them hospitality. The Rumanian Government, however, was under intense pressure from Hitler to renege on the deal. One government official, Eugeniuz Kwiatkowski, noted the result: ‘They divide us. The President is to be placed near Bacau, government ministers and the Marshal [Rydz-Śmigły] will be sent to Craiova, near the Bulgarian border. Officials will be scattered all over the place, the army interned, equipment taken. It would have been better to have evacuated to Hungary.’102 Indeed, Biddle sent a despatch to the secretary of state stating:

While Marshal’s internment is covered by Hague Convention of 1907, I am aware of no precedent for the internment of the Government of a belligerent country if that Government seeks transit through a neutral country. If therefore my assumption is correct in this regard Rumania’s internment of Polish Government officials would represent a violation of international law.103

Neither the British nor the French government made any great efforts to persuade the Rumanian Government to release the interned Polish ministers. The president felt that he had no alternative but to resign so that a Polish government-in-exile could be established in France.* His efforts to do so were hampered by the Rumanians banning direct communications between the ministers, which was circumvented by Colonel Beck’s wife acting as liaison and conducting the necessary negotiations.104

The establishment of a Polish government-in-exile was possible because the ‘constitution took into account the needs and possibilities of wartime, and contained no prescription which would render impossible the existence and functioning of state authority outside the frontiers of the country’.105 Mościcki nominated the Polish ambassador in Italy, General Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski, as his successor, but on 26 September, in an act that came as ‘a complete bombshell’ to the British Government, the French Government refused to recognise him.106 The Polish ambassador in Paris, Juliusz Łukasiewicz, met the Polish ambassador in London, Raczyński, to discuss alternatives. It was felt that Ignacy Paderewski was too ill to take office, and the whereabouts of the preferred candidate, General Sosnkowski, were unknown; therefore, they settled on Władysław Raczkiewicz as the most suitable. Having been a former president of the Senate and currently chairman of the Organisation for Poles Abroad, he was seen as politically neutral and unlikely to offend either the members of the Sanacja regime or the representatives of the opposition. He was also accepted by the allied governments and was duly sworn into office. General Sikorski had accompanied Noël on his return to Paris on 24 September. Łukasiewicz, in charge in Paris until a new president was appointed, did not know what to do with Sikorski but soon gave him command of the Polish Army re-forming in France. After becoming president, Raczkiewicz appointed Sikorski as prime minister and then, on 7 November, as commander-in-chief. On 9 December, a National Council of twenty-two representatives of Polish political parties was established. The new government was based in Angers, on the Loire, 190 miles from Paris.107

Sikorski’s government was weak from the start. The pre-war opposition members, including Sikorski, clashed with those members of the Sanacja regime who had escaped from Rumania. The result disgusted Polish soldiers who wanted a united and strong government to lead them: