Chapter 1

Introduction

A Transdisciplinary Framework of SLA

Overview

Almost everyone has experienced the learning of a language or languages in addition to their first or native language. For some, the experience may take place in the classroom, where the study of foreign languages is a common subject area offered by schools. Others’ first encounters with another language may come from living with caregivers such as grandparents or care providers who speak a language that is different from the dominant language of the community. In these contexts, individuals typically learn different words and phrases in the language of their caregivers to communicate with them about their home-life experiences.

Others may experience language learning by picking up certain words and phrases they encounter while watching television, listening to music, playing video games, or using the internet to find information or communicate with others about shared interests. Still others’ experiences with learning another language may happen as friendships are formed with individuals who speak different languages. Understanding how children, adolescents, and adults learn additional languages and the forces that shape the outcomes of their experiences, whether they occur in the classroom, on the internet, or in a myriad of social contexts, is the central concern of the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA).1

The SLA field began as an interdisciplinary endeavor in the broader field of Applied Linguistics over half a century ago, with its early research efforts drawing on intellectual developments on language and learning from the fields of linguistics and psychology. The field’s strong ties to these disciplines directed SLA’s research efforts to concerns with uncovering and explaining the role of cognitive mechanisms in acquiring the structural components of another language. These concerns were mainly limited to language learning by monolinguals, i.e., speakers of only one language, who were learning a second language in addition to their first language. This explains the use of the term second in the field’s name.

As research interests expanded through the 1970s and 1980s, the field recognized that language learners often come to their varied contexts of learning already knowing more than one language. Thus, while the field retained the term second in its name, its scope was broadened to include the learning of any additional language, whether it be learners’ second, third, or fourth languages, and whether the language is considered a group or community language, a foreign or world language, or an indigenous, minority, or heritage language. The field also uses the term L2 as an alternative term for second language.

Over the last 25 years or so, and particularly since the turn into the twenty-first century, the scope of the field has undergone tremendous growth. The expansion has been fueled in large part by recognition of the need for alternative perspectives that more adequately explain the real-world experiences of L2 learners in modern day society in light of the profound changes brought about by the intersecting forces of globalization, technologization, and large-scale migration. For example, the proliferation of digital technologies such as computers, video games, smart phones, and the internet, has changed the ways in which L2 learners interpret and make meaning, with graphic, pictorial, audio, and spatial patterns of meaning integrated within or even supplanting traditional spoken and written texts.

Together these forces have given rise to communities that are increasingly linguistically, socially, and culturally diverse. Within and across these communities, new and more heterogeneous forms of social activity and options for participating in them that are more diverse, more multilingual, multimodal, and dynamic continue to emerge. In these environments, opportunities for learning additional languages have been expanded and transformed.

L2 learners come to these contexts with diverse social identities marked by varying degrees of access to the activities and their meaning-making resource. L2 learners’ varied access to, motivation, and investment in participating in the activities lead to varying developmental trajectories. In some contexts, learners may develop understandings of and skills to use comprehensive and elaborate multilingual resources. In other contexts, L2 learners may develop more specialized resources that are linked to those contexts or they may develop minimal, transitory bits of additional languages, such as isolated greeting patterns, e.g., hola from Spanish or sayonara from Japanese (Blommaert & Backus, 2011). In other contexts, despite ample access to varied social encounters marked by extensive use of multilingual resources, L2 learners may remain monolingual.

To make sense of the varying processes and outcomes of L2 learning, researchers have looked to other disciplines including anthropology, sociology, and education in addition to areas considered subfields of linguistics and psychology, such as functional linguistics, neurolinguistics, and cultural psychology for insights and research findings. These explorations have resulted in a proliferation of approaches to SLA in addition to the historically dominant cognitive approaches. These approaches range from those that focus on the very micro levels of L2 learning, i.e., the neurobiological and cognitive conditions and outcomes of L2 learning, to the more macro levels, i.e., the sociocultural and ideological structures that both shape and are shaped by L2 learning.

Each of the approaches is characterized by particular research agendas, which, for the most part, are defined by disciplinary concerns that are built on specific disciplinary theories and key concepts. These, in turn, define particular objects of investigation and particular research methods to advance study of the objects. They also specify terminologies to refer to the objects of study and value certain methods of investigation over others, the purpose of which is to advance new hypotheses about the formal properties of the theories and concepts. Their theories, concepts, and methods give shape both to the directions that research projects take and their outcomes.

Arguing for engagement across perspectives to advance the field, some SLA scholars from these different approaches have come together to explore concepts from different perspectives, such as the nature of language and learning. One well-known exploration is Dwight Atkinson’s (2011) volume entitled Alternative Approaches to Second Language Acquisition, in which six complementary perspectives on L2 learning are presented. While these efforts have made great contributions to the advancement of theoretical and conceptual understandings about language and learning, for the most part, their intellectual energies have remained on disciplinary concerns. Their capacity for providing solutions to the real-world challenges of L2 learning in modern day society has been less effective. This is due in large part to the fact that the challenges of L2 learning are highly complex, varying across individuals, across groups and across communities. Practical, participant-relevant and sustainable responses to these challenges cannot be construed from only one or two disciplinary perspectives.

A Transdisciplinary Framework of SLA

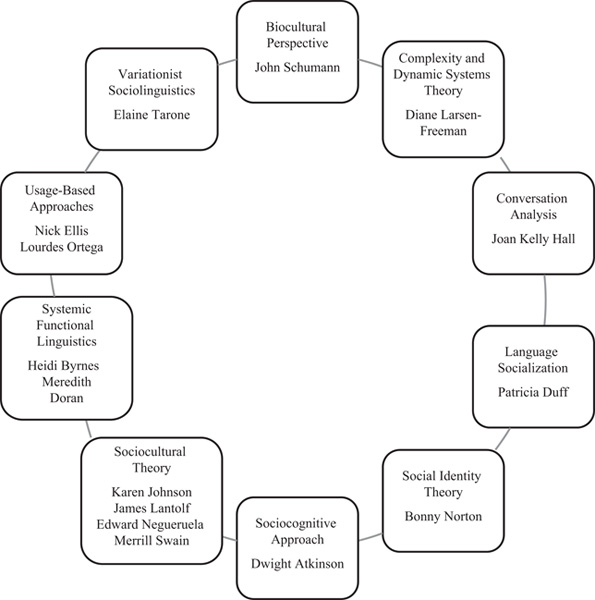

To meet the challenges of addressing the real-world issues of L2 learning, a new intellectual framework for the field of SLA has emerged (Douglas Fir Group, 2016). Termed transdisciplinary, the framework was developed by a group of 15 scholars, each member of which identifies with a particular disciplinary or interdisciplinary approach to SLA, and whose extensive collaborations over an extended period of time resulted in the development of the framework. The approaches to SLA represented in the transdisciplinary framework include the biocultural perspective, complexity and dynamic systems theory, conversation analysis, language socialization, social identity theory, the sociocognitive approach, sociocultural theory, systemic functional linguistics, usage-based approaches, and variationist sociolinguistics. These are displayed in Figure 1.1 and each approach includes the names of SLA scholars comprising the Douglas Fir Group who represent it.

Figure 1.1 Approaches to SLA represented in the transdisciplinary framework.

At its center, the transdisciplinary framework is pragmatic and problem-oriented. While it acknowledges the value of the distinct disciplinary and interdisciplinary perspectives, it recognizes that a broader, and at the same time, more grounded perspective of SLA is needed to capture the whole project of SLA in all its multifaceted complexity. It provides such a view by synthesizing findings on L2 learning arising from the various research efforts across disciplines and over many different levels of detail and time spans.

The framework presented in this text expands on the foundational work of the Douglas Fir Group (2016) and adds to their efforts by drawing connections between current understandings of the many dimensions of L2 learning and understandings of and practices for doing L2 teaching. Its goal is twofold. First, it aims to advance understandings of the ever-changing landscapes of L2 learners’ social worlds that are ecologically valid (Cicourel, 2007). Understandings that are ecologically valid are fair and credible representations of “the possibilities and constraints faced by L2 learners in their social worlds on all levels of activity and across time spans” (Douglas Fir Group, 2016, p. 39). The second goal is to create deeper, more nuanced understandings of L2 learning that can inform L2 teachers’ development of practical, innovative, and sustainable solutions for expanding L2 learners’ diverse multilingual repertoires of meaning- making resources across a range of social contexts and over their lifespan. In the next section, we summarize the multifaceted, dynamic nature of SLA.

Multifaceted Nature of SLA

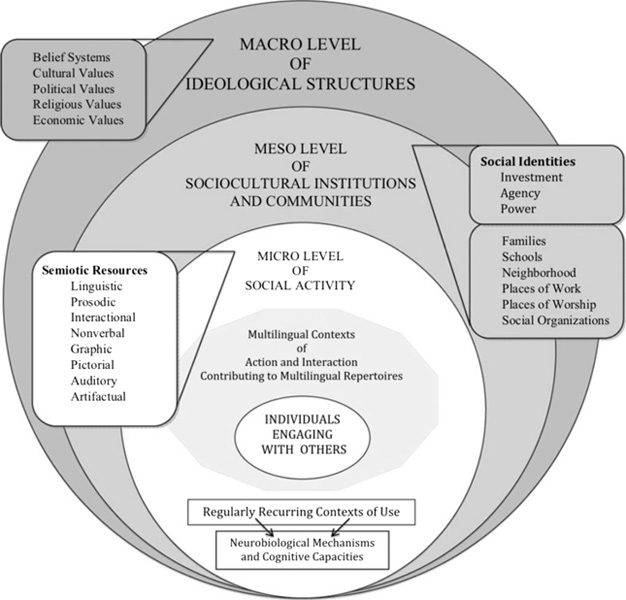

Foundational to the transdisciplinary framework is the understanding that SLA is a complex, on-going, multidimensional phenomenon involving the dynamic and variable interplay among a range of individual internal cognitive capabilities on the one hand and, on the other, L2 learners’ diverse experiences in their multilingual worlds (Douglas Fir Group, 2016). From their experiences, L2 learners develop variable repertoires of multilingual semiotic resources (Hall, Cheng & Carlson, 2006; Blommaert & Backus, 2011). Semiotic resources are an open set of ever-evolving multilingual and multimodal means by which meanings are made in social contexts of action. They include a wide array of linguistic constructions in addition to nonverbal, visual, graphic, and auditory modes of meaning making. The dynamic multidimensional nature of SLA is illustrated in Figure 1.2. As shown, three mutually dependent layers of social activity shape L2 learning.

Micro Level

At the micro level of social activity, L2 learners draw on various internal mechanisms and capacities as they interact with others in a multiplicity of social contexts. The scope of these contexts can be wide-ranging, and may include everyday, informal contexts of interaction, such as personal conversations with family members and friends enacted in face-to-face encounters or via technological means such as cellphones and the internet. They can also include ad hoc social conversations with neighbors and work mates. Interactions may also include more formal contexts such as those found in educational or workplace settings where many interactions are undertaken for instructional or professional purposes.

Figure 1.2 The multifaceted nature of language learning and teaching.

Source: Douglas Fir Group (2016, p. 25).

These encounters can be highly routinized in that the goals of the interaction, the roles of participants, and the semiotic resources are very familiar to all involved. Other interactions may be less routine or familiar. Entering workplaces as new employees can present L2 learners with new, unfamiliar contexts of interaction. Likewise, traveling to different geographical regions may involve L2 learners in a diversity of contexts of interaction. In some cases, they may be familiar contexts, e.g., service encounters such as those that occur in stores and restaurants, but the expectations for how to take action and the resources used to make meaning in these actions will be new. In other cases, the contexts and goals and roles of participants may be entirely new.

In their interactions with others in their varied contexts of social action, L2 learners draw on a set of neurobiological and cognitive and emotional capacities with which all human beings are endowed. These include social cognitive skills that drive individuals to seek cooperative interaction with others and general cognitive capabilities that make possible the processing of information. These capabilities guide learners in selecting and attending to particular meaning-making semiotic resources and their patterns of use and in forming schemas based on the recurrences of the resources in their encounters. They also guide learners in creating mappings across resources based on functional similarities, and to hypothesize about and continually test their understandings of and abilities to use the resources in context-sensitive ways.

Supporting L2 learners’ cognitive processes are cues used by others that help to make transparent the patterned uses of semiotic resources and assist learners in noticing and remembering them. Such assistance can involve a range of resources that explicitly direct learners’ attention to the relevant semiotic resources and their meaning-making potentials, and other less explicit actions such as, for example, repetitions, tone and pitch changes to speech, and eye gaze and gestures. In classrooms for example, such work is typically accomplished via an assemblage of instructional actions that direct learners to perceive or notice the relevant resources and to make connections between them and their contexts of use. The more routine, frequent, and stable the occurrences of particular resources are in L2 learners’ interactions with others, and the more learners’ attention is drawn to their form-meaning pairings, the more entrenched the resources become as cognitive representations of their experiences. Variations in L2 learners’ experiences lead to the development of varied multilingual repertoires of semiotic resources, each which is linked to different social contexts and in continuous adaptation to its use (Bybee & Hopper, 2001). All else being equal, the more extensive and complex the contexts of interaction become over time and the more enduring L2 learners’ participation is in them, the more complex and enduring their multilingual repertoires will be.

Meso Level

The sociocultural institutions within which L2 learners’ contexts of interactions are situated constitute the meso level of social activity. These institutions include the family, neighborhoods, schools, and places of work and worship. Also included are social and community organizations such as clubs, sports leagues, political parties, various online contexts, and so on.

L2 learners’ institutions and their particular contexts of interaction are shaped by pervasive social, cultural, economic, political, and other conditions. These conditions not only influence the types of contexts of interactions that are enacted in them, but also shape the particular attitudes, perspectives, motives, and values that are embodied in the contexts of interaction. In schools, for example, some contexts of interaction are perceived to have more value than others. In some social groups, student self-initiation and active participation are highly valued while in others such actions break the social norms of group conformity and are seen as a challenge to teacher authority. These perceptions and values are historically derived, developed over time and tied to particular social groups with the authority to shape them (Heath, 1983; Hymes, 1980). Often invisible, this authority derives from various levels of social, political, and economic powers.

Contexts of interactions constituting L2 learners’ social institutions, along with their attendant perspectives, attitudes, motives, and values can and, in fact, do vary within and across geographical regions, and in some cases, they vary quite widely. What may be considered appropriate contexts of interaction in an institution of one community, for example, may be considered inappropriate or even highly unsuitable in that of another community. These variations can lead to differences in the development of L2 learners’ repertoires of semiotic resources.

The widespread social, cultural, other conditions tied to the various sociocultural institutions also shape learners’ social identities. Social identities are aspects of L2 learners’ personhoods that are defined in terms of the various social groups into which they are born, including, for example, groups defined by ethnicity, race, social class, nationality, and religion (Ochs, 1996). They also have a second layer of social identities, defined by the role relationships they create or are assigned to in the various contexts of interactions of their social institutions. In families, for example, individuals take on roles as parents, children, siblings, and interact with others, as, for example, mothers to daughters, brothers to sisters, or husbands to wives. Likewise, in the workplace, L2 learners interact with others in their roles as, for example, supervisors, managers, subordinates, or colleagues.

Learners’ social identities and the groups they belong to are significant to the development of their multilingual repertoires in that they define in part the kinds of contexts of interaction and the particular semiotic resources for accomplishing them to which they have access. For example, in some regions of the world, depending on their race or social class, some L2 learners may find the L2 learning opportunities they have access to are limited or constrained while others may find their opportunities to be abundant and unrestrained (Collins, 2014).

All else being equal, the greater the number and diversity of contexts of interaction within and across social institutions that L2 learners are given access to and are motivated to participate in, the richer and more linguistically diverse the semiotic resources of these contexts are, and the more extended their opportunities are for deriving form-meaning patterns of these meaning-making resources, the more robust their multilingual repertoires arising from their experiences are likely to be compared to those of L2 learners with fewer and less varied experiences.

Macro Level

Ideological structures constitute the macro level of social activity. Ideologies are individual- and group-shared beliefs and values about the form and influence of culture, politics, religion, and economics on all levels of social activity (Kroskrity, 2010). Often invisible and taken for granted, the beliefs and values influence the ways that individuals and groups view their worlds and act within them and the ways they interpret the actions of others.

Ideologies about language use and language learning are especially significant to SLA endeavors, influencing language policy and planning on all levels of social activity. For example, they shape decisions on which language or languages are official, how they are to be used in various institutional settings and the opportunities that are made available to individual L2 learners, as members of their social groups, to learn, use and maintain these languages (Farr & Song, 2011). Beliefs and values at the macro level are in constant interaction with the other levels of social activity, and may vary and even be contradictory within and across individuals, groups, contexts of interaction, and social institutions.

While each of the three levels of social activity has its distinguishing features, no level exists on its own, apart from the others. Each exists only through constant, dynamic interaction with the others, with each level of activity shaping and being shaped by the others. Understanding the cognitive and social conditions giving shape to L2 learning at each level is essential to understanding the whole project of SLA.

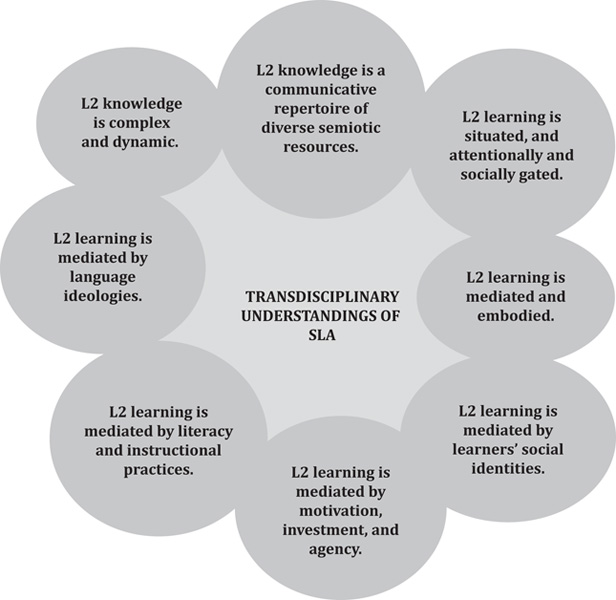

Themes Deriving from the Transdisciplinary Framework of SLA

Eight fundamental themes about the nature of language and learning can be derived from the three interdependent levels of social activity.2 Each theme offers action possibilities for L2 research, L2 learning, and L2 teaching. These themes are represented in Figure 1.3. As shown in the figure, no one theme is more important than another nor are they categorical. Rather, they are interdependent, overlapping and in dialogue with each other. Below, each of the eight themes is summarized. These themes, their attendant concepts and understandings, and their implications for understanding L2 teaching are covered more deeply in subsequent chapters of the text.

Figure 1.3 Transdisciplinary understandings of SLA: Eight fundamental themes.

Theme 1: L2 Knowledge Is Complex and Dynamic

This theme addresses the composition of language knowledge. In contrast to a view of language knowledge as an unchanging, fixed system of abstract structures, a transdisciplinary perspective understands it to be a dynamic, open-ended collection of varied resources for making meaning (Bybee & Hopper, 2001; Halliday, 1975, 1993; Hymes, 1972a, 1972b). The collections of resources that comprise L2 learners’ knowledge develop from their experiences in contexts of interaction as they go about doing “the communicative work humans do” (Bybee & Hopper, 2001, p. 3). This means that to learn another language one must be involved in contexts of interaction using the language. All else being equal, the salient resources by which the contexts of interaction are accomplished are the resources that eventually become appropriated by the learner. Any appearance of stability in L2 learners’ language knowledge is a matter of stability in their social experiences, with similar resources across users reflecting “historically popular solutions to similar communicative and coordination problems” (Ibbotson, 2012, p. 124).

Theme 2: L2 Knowledge Is a Repertoire of Diverse Semiotic Resources

Addressed in this theme is the transdisciplinary understanding of L2 knowledge as more than just linguistic resources. In fact, it comprises a wide range of semiotic resources for making meaning that include nonverbal, visual, graphic, and auditory modes (Kress, 2009). All semiotic resources, individually and in combination, have conventionalized form-meaning combinations that develop from their past uses in particular contexts of action which, in turn, are shaped by forces at both the meso and macro levels of social activity.

In response to criticisms that using the term competence to refer to the collection of semiotic resources that L2 learners know carries an ideology that implies homogeneity and permanence (Blommaert & Rampton, 2011; Hall, 2016; Makoni & Pennycook, 2007), a transdisciplinary perspective uses the term repertoire to capture the dynamic, malleable nature of individual L2 knowledge. The greater the number and diversity of contexts of interaction within and across social institutions that L2 learners are given access to, and are motivated to participate in, the richer and more diverse their repertoires of semiotic resources will be.

Theme 3: L2 Learning Is Situated, and Attentionally and Socially Gated

This theme deals with the situated nature of L2 learning. As noted earlier, L2 learning begins at the micro-level of social activity, through L2 learners’ repeated experiences in situated, regularly occurring contexts of interaction. In their interactions, they draw on a set of cognitive capabilities that interact with the properties of the input to give shape to their repertoires. These include capabilities to select and attend to particular meaning-making components and their patterns of action, to form representations based on their recurrences, to create mappings across units based on functional similarities, and to hypothesize about and continually test their understandings of their meanings.

Key aspects of the input that interact with these capabilities are the distribution and frequency with which particular semiotic resources are encountered. The more frequent the occurrence of different semiotic resources and the more learners’ attention is drawn to them, the more entrenched they become as cognitive representations of L2 knowledge. Conversely, the less frequent the occurrences of the resources are or the less noticeable they are to L2 learners, the more weakly these resources are represented in learners’ L2 knowledge (Ibbotson, 2013).

Theme 4: L2 Learning Is Mediated and Embodied

Theme 4 addresses the social nature of L2 learning processes. Supporting learners’ cognitive processes in noticing, ordering, representing, and remembering their involvement in their contexts of interaction are cues used by others, typically more experienced participants, which indicate or call attention to the form–meaning patterns and assist L2 learners in noticing and remembering them (Dabrowska, 2012; Ellis & Larsen-Freeman, 2006; Tomasello, 2003, 2008). The cues can take many forms, including verbal and nonverbal instructions that explicitly direct L2 learners’ attention to particular resources and their meanings. They can also be less explicit cues such as repetitions, sound changes as one speaks, eye gazes, and gestures; they can include computational resources such as computers and calculators, graphic resources such as diagrams, maps and drawings, and writing systems. It is often the case that multiple embodied modes are used simultaneously. One can point while speaking, for example, or gesture to an illustration to prompt learners’ attention. Another way to refer to the action of using cues to draw learners’ attention to aspects of their contexts of interaction is mediation. Learning is mediated by the use of various multimodal, semiotic resources as L2 learners move through, respond to, and make sense of their social worlds (Scollon, 2001; Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1994).

Theme 5: L2 Learning Is Mediated by Learners’ Social Identities

This theme is concerned with the variable role that learners’ social identities play in L2 learning. L2 learners come to their contexts of interaction as actors with multiple intersecting, sometimes conflicting, social identities. The social institutions of their groups and communities not only influence social expectations for how L2 learners’ social identities are enacted and the semiotic resources they have access to; they also influence learners’ motivations for seeking out and pursuing interactions with others.

In addition to their actual social identities, L2 learners’ imagined social identities and group memberships can influence their access to particular social institutions and contexts of interaction within them (Pavlenko & Norton, 2007; Norton, 2000; Norton & Toohey, 2011). Imagined identities and social group memberships are those that learners desire to assume or adopt because they perceive that such group memberships can offer them greater access to a wider range of “socially constituted repertoires of identificational and affiliational resources” (Bauman, 2000, p. 1) and opportunities for interaction. These in turn, they anticipate, will afford them greater economic and/or social stability. Moreover, through varying degrees of access to and memberships of their real and desired social groups and role relationships, new identities may become available to them, further shaping their opportunities for expanding their L2 repertoires. For example, refugees are often positioned to enter the unskilled or low-wage labor force despite the professional qualifications they bring with them from their home countries. They will most likely need to resist this positioning if they are to gain access to opportunities in which they will be able to achieve both personal and professional goals. For all L2 learners, their expanding repertoires will, in turn, influence the identities and the means for enacting them they will have access to (Norton, 2013).

Theme 6: L2 learning Is Mediated by Motivation, Investment, and Agency

Theme 6 deals with the roles that motivation, investment, and individual agency play in the learning process. While learners’ L2 repertoires are to a great extent shaped by social institutional expectations about their group memberships, as individual agents they also play a role in shaping them. For example, in contexts of interaction where L2 learners struggle to participate from one identity position, they may be able to act independently from some factors of influence and create or take on different identities and social roles. Such agentive moves can serve to change their access and opportunities to use particular resources and to participating in particular contexts of interaction (Higgins, 2015; Morita, 2004; Norton & Toohey, 2011; Rampton, 2013). However, the degree of individual effort L2 learners can exert in shaping their identities is not equal across contexts. Rather, it is “an aspect of the action” (Altieri, 1994, p. 4), negotiable in and arising from the particular social, political, economic, and other forces that give shape to the social institutions and by extension L2 learners’ local contexts of interaction.

Theme 7: L2 Learning Is Mediated by Literacy and Instructional Practices

Theme 7 discusses the influential role of literacy and instructional practices in shaping learners’ L2 repertories. Like the other factors involved in shaping L2 learning, the types of literacy and instructional practices that L2 learners engage in over extended periods of time can vary, and in some cases quite widely. The degrees of variation in the types of practices and the resources used to accomplish them along with the varying paths that learners’ socialization into them take lead to variations in the development of learners’ L2 repertoires. The empirical understandings of the links between variations in these practices and L1 learning are undisputed; empirical knowledge about their influences on L2 learning are only beginning to be fully understood.

Theme 8: L2 Learning Is Mediated by Language Ideologies

Theme 8 is concerned with the influence of language ideologies on L2 learning. Language ideologies (beliefs, feelings, and conceptions about language) are especially significant to the endeavors of L2 learning. They shape not only the contexts of interaction and semiotic resources that L2 learners have access to but also learners’ investment in their and others’ social identities and their motivation for engaging with others in their contexts of interaction (Ricento, 2000; Tollefson, 2002).

These ideologies influence language policies on all levels of social activity. They give shape to decisions on which language or languages are official, which languages and language varieties are valued, and the educational opportunities that are made available to individuals to learn and use them (De Costa, 2010; Farr & Song, 2011; Hult, 2014). A particularly damaging language ideology to L2 learning is the belief that monolingualism is the “default for the human capacity for language” (Ortega, 2014, p. 35) and thus the standard against which language use is judged. It can function to create negative social, academic, and personal evaluations of L2 learners and of any language not considered to be the official or standard language. Understanding how these beliefs about language, which are often invisible, influence L2 learning at all levels of SLA is critical to understanding the whole enterprise of SLA.

Summary

The transdisciplinary framework presented here offers an integrated representation of the multilayered complexity of SLA. It is on the micro-level of social interaction where L2 learning begins, with L2 learners’ repertoires of semiotic resources emerging from continual interaction between internal biological and cognitive capacities on the one hand and their trajectories of experiences in specific contexts of interaction on the other. Their experiences, in turn, are shaped by larger social institutional contexts whose structures of expectations influence not only the scope and scale of L2 learners’ social experiences and the meaning potentials of their semiotic resources. They also give shape to learners’ social identities, which can lead to varied opportunities for access to their experiences. At the macro level, these institutional expectations are influenced by larger, more persistent forces and ideologies, which make possible and, at the same time, are made possible by social activity on all levels. The dynamic and malleable repertoires of resources that L2 learners develop from their real-world experiences over their lifespans are cognitive in that they are represented in learners’ minds as relatively automatized, functionally distributed, and context-sensitive collections of semiotic resources. They are, at the same time, social in that the development of individual repertoires is tied to learners’ varied experiences in multilingual contexts of action within and across all sociocultural institutions. Variations in conditions at all levels of social activity, from the very micro scale of social life to large-scale social ideologies lead to dynamic and varied trajectories of L2 development and, ultimately to learners with dynamic, varied multilingual repertoires. The eight themes deriving from the transdisciplinary framework of SLA along with their implications for L2 teaching are discussed in greater depth in subsequent chapters.

Implications for Understanding L2 Teaching: The Text’s Pedagogical Approach

We believe that for the transdisciplinary framework for SLA to be relevant to the work of language teachers it must be grounded in the actual activities of becoming and being a language teacher. In addition, the framework must be made accessible in ways that facilitate, i.e., mediate, teachers’ reevaluation of their understandings of and skills for teaching such that the content of their instruction is relevant, usable, and accessible to their students.

In line with these goals, the pedagogical activities found at the end of each chapter are adapted from Cope and Kalantiz’s (2000, 2009, 2015) reflexive approach to pedagogy and curriculum. Originating from the New London Group’s (1996) “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies”, reflexive pedagogy is deliberate teaching that engages learners in moving between and among different ways of knowing, connecting to their own experiences, and applying their learning to their social worlds. The different ways of knowing are what Cope and Kalantzis have labeled knowledge processes. A knowledge process is an activity type that represents a distinct way of making knowledge.

The four knowledge processes around which pedagogical activities are organized at the end of each chapter are labeled experiencing, conceptualizing, analyzing, and applying, and each knowledge process is subsequently distinguished by two interconnected processes as illustrated below.

Experiencing:

the known – learners reflect on their own familiar experiences, interests and perspectives

the new – learners observe or take part in something that is unfamiliar; they are immersed in new situations or content.

Conceptualizing:

by naming – learners group things into categories, label them with abstract terms, and define these terms

with theory – learners make generalizations using concepts, and connect terms in concept maps or theories.

Analyzing:

functionally – learners analyze logical connections, cause and effect, structure and function

critically – learners evaluate their own and other people’s perspectives, interests, and motives.

Applying:

appropriately – learners apply new learning to real-world situations and test their validity

creatively – learners make an intervention in the world which is innovative and creative, or transfer their learning to a different context.

The four dimensions of knowledge processes do not represent rigid, ordered stages of learning. Rather, they are complexly interrelated, “elements of each [which] may occur simultaneously, while at different times one or the other will predominate, and all of them are repeatedly revisited at different levels” (New London Group, 2000, p. 85). Together, the activities support teachers’ use of conceptual and informational resources of a transdisciplinary framework of SLA to reframe and/or reconstruct their own personal experiences as L2 learners, L2 users, and developing L2 teachers.

Pedagogical Activities

In each chapter, you will engage in a series of pedagogical activities that are organized around the four knowledge processes. The activities can be completed in writing or orally, and individually or in small groups, or in some combination of both. In the pedagogical activities for this chapter, you will engage in different knowledge processes that will assist you in relating to and making sense of the conceptual and informational resources of a transdisciplinary framework of SLA covered in this chapter.

Experiencing

A. Language Learning Experiences

Reflect on your own language learning experiences. These may be in language classrooms, with family or friends, while traveling or living in a new country or culture, or work related. Reflect on what was unique about these experiences and why. Then select one experience that was particularly memorable and create a visual depiction that captures the essence of this experience for you as a language learner. With your classmates, in pairs or small groups, or in a reflection paper, describe what was unique about this language learning experience and why.

B. Language Learning Experiences

Imagine a language learning experience that you have not encountered before but would like to and consider the following questions.

What might be the social, cultural, academic, and/or professional setting for this experience?

What would you expect to happen during this experience?

What would you like to accomplish through this experience?

Create a visual depiction that captures the essence of this experience for you as a language learner. In pairs or small groups, or in a reflection paper, describe your imagined language learning experience and why you have framed it as you have.

Conceptualizing

A. Three Levels of Social Activity

Examine both visual depictions that you created according to the distinguishing features that make up the micro, meso, and macro levels of social activity as defined in this chapter. In pairs or small groups, or in a reflection paper, describe the sociocultural institutions and communities in which each takes place, explain the ideological structures that are most salient, and identify the most routinized patterns of social activity.

B. Three Levels of Social Activity

Examine both visual depictions, identify any connections that emerge between the micro, meso, and macro levels of social activity, and then consider the following:

What effect might particular ideologies about language have on how particular semiotic resources are utilized at the micro level of social activity?

Conversely, how might the use of particular semiotic resources reflect the beliefs systems that are apparent at the macro level?

Analyzing

A. Fundamental Themes of a Transdisciplinary Framework

Analyze both visual depictions for evidence of the eight themes presented in this chapter. Select three or four themes that you believe are most salient in both your actual and imagined language learning experiences. They may be the same themes or different ones. Write a reflection paper in which you describe how you have experienced each of these themes in your actual language learning experiences. Compare these themes to those you might experience in your imagined language learning experiences.

B. Language Learning Experiences

Create a list of the most salient similarities and differences between your actual and imagined language learning experiences. In pairs or in small groups, consider the following questions:

What do these similarities and differences suggest about the multifaceted nature of SLA?

What do these similarities and differences suggest about the varied trajectories of L2 language development?

Applying

A. Fundamental Themes of a Transdisciplinary Framework

Select one of the eight fundamental themes and design a mini-inquiry project in which you investigate and report on evidence of how this theme plays out in a real-world situation.

For example: Theme 1: L2 Knowledge Is Complex and Dynamic

Observe at least five patrons involved in a typical service encounter in a real-world setting (ordering coffee in a coffee shop, etc.). Take field notes on both the routinized and idiosyncratic ways in which patrons and servers use language to accomplish this service encounter. Write a paper in which you report on what you observed and articulate what you believe your observations suggest about the complex and dynamic nature of language.B. Fundamental Themes of a Transdisciplinary Framework

Based on the findings of your mini-inquiry project, create an instructional activity for a particular group of L2 learners, in a particular instructional context that will enable them to develop an awareness of how this theme plays out in a real-world situation.

For example: Theme 1: L2 Knowledge Is Complex and Dynamic

Create three different dialogues that depict a typical service encounter in a real-world setting (e.g., ordering coffee in a coffee shop, etc.). Ask the group of L2 students to compare and contrast the three dialogues noting in particular the various ways in which language is used to accomplish each encounter. Have the students report on what they noticed and articulate what they believe their observations suggest about the complex and dynamic nature of language.Notes

1SLA’s object of inquiry has been and continues to be the learning of languages “at any point in the life span after the learning of one or more languages has taken place in the context of primary socialization in the family; in most societies this means prior to formal schooling and sometimes in the absence of literacy mediation” (Douglas Fir, 2016, p. 21). Although concerned with the study of additional languages as well, studies of bilingual first language acquisition (BFLA), i.e., “language development among infants and children when they grow up surrounded by two or more languages” (Ortega, 2011, p. 171), have historically remained outside the main purview of SLA and dealt with, instead, in the field of bilingualism.

2These themes are adaptations of the ten themes formulated by the Douglas Fir Group (2016).

References

Altieri, C. (1994). Subjective agency. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Atkinson, D. (2011). Alternative approaches to second language acquisition, 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

Bauman, R. (2000). Language, identity, performance. Pragmatics, 10, 1–5.

Blommaert, J., & Backus, A. (2011). Repertoires revisited: “Knowing language” in superdiversity. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 67. Accessed 23 July 2012 at www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/departments/education/research/ldc/publications/workingpapers/67.pdf.

Blommaert, J., & Rampton, B. (2011). Language and superdiversity. In Diversities, 13, Accessed 9 February 2014 at http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002147/214772e.pdf#214780.

Bybee, J., & Hopper, P. (2001). Introduction to frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure. In J. Bybee & P. Hopper (Eds.), Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure (pp. 1–24). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Cicourel, A. (2007). A personal, retrospective view of ecological validity. Text & Talk, 27, 735–752.

Collins, J. (2014). Literacy practices, linguistic anthropology and social inequality. Working Papers in Urban Language & Literacies, 143. Accessed 15 November 2014 at www.academia.edu/9277086/WP143_Collins_2014._Literacy_practices_linguistic_anthropology_and_social_inequality.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.) (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London: Routledge.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(3), 164–195.

Cope, B., & Kalantiz, M. (Eds.) (2015). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Learning by design. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dabrowska, E. (2012). Different speakers, different grammars: Individual differences in native language attainment. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 2, 219–225.

De Costa, P. I. (2010). Reconceptualizing language, language learning, and the adolescent immigrant language learner in the age of postmodern globalization. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4, 769–781.

Douglas Fir Group (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100, 19–47.

Ellis, N. C., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (2006). Language emergence: Implications for applied linguistics. Introduction to the Special Issue. Applied Linguistics, 27, 558–589.

Farr, M., & Song, J. (2011). Language ideologies and policies: Multilingualism and education. Language and Linguistics Compass, 5, 650–665.

Hall, J. K. (2016) A usage-based view of multicompetence. In V. Cook & W. Li. (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of linguistic multicompetence (pp. 183–206). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hall, J. K., Cheng, A., & Carlson, M. T. (2006). Reconceptualizing multicompetence as a theory of language knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 27, 220–240.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1975). Learning how to mean: Explorations in the development of language. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1993). Toward a language-based theory of learning. Linguistics and Education, 5, 93–116.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and in classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Higgins, C. (2015). Intersecting scapes and new millennium identities in language learning. Language Teaching, 48(3), 373–389.

Hult, F. (2014). How does policy influence language in education? In R. Silver & S. Lwin (Eds.), Language in education: Social implications (pp. 159–175). London: Continuum.

Hymes, D. (1972a). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269–293). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Hymes, D. (1972b). Models of the interaction of language and social life. In J. J. Gumperz & D. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication (pp. 35–71). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Hymes, D. (1980). Language in education: Ethnolinguistic essays. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Ibbotson, P. (2012). A new kind of language. The Psychologist, 25, 122–125.

Ibbotson, P. (2013). The scope of usage-based theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–15.

Kress. G. (2009). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Kroskrity, P. (2010). Language ideologies. In J–O. Ostman & J. Verschueren (Eds.), Handbook of pragmatics (pp. 1–24). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lee, N., Mikesell, L., Joaquin, A. D. L., Mates, A. W., & Schumann, J. H. (2009). The interactional instinct: The evolution and acquisition of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Makoni, S., & Pennycook, A. (Eds.) (2007). Disinventing and reconstituting languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Morita, N. (2004). Negotiating participation and identity in second language academic communities. TESOL Quarterly, 38, 573–603.

New London Group (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66, 60–92.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and second language acquisition. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44, 412–446.

Ochs, E. (1996). Linguistic resources for socializing humanity In J. J. Gumperz & S. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 407–437). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ortega, L. (2011). SLA after the social turn: Where cognitivism and its alternatives stand. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches in second language acquisition (pp. 167–180). New York: Routledge.

Ortega, L. (2014). Ways forward for a bi/multilingual turn in SLA. In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education (pp. 32–52). New York: Routledge.

Pavlenko, A., & Norton, B. (2007). Imagined communities, identity, and English language teaching. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 669–680). New York: Springer.

Rampton, B. (2013). Styling in a language learned later in life. The Modern Language Journal, 97, 360–382.

Ricento, T. (2000). Historical and theoretical perspectives in language policy and planning. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4, 196–213.

Schumann, J. (2010). Applied linguistics and the neurobiology of language. In R. Kaplan, (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 244–259). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scollon, R. (2001) Mediated discourse. London: Routledge.

Tollefson, J. W. (Ed.) (2002). Language policies in education: Critical issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Tomasello, M. (2003). Constructing a language. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, M. (2008). The origins of human communication. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1994). The primacy of mediated action in sociocultural studies. Mind, Culture and Activity, 1, 202–208.